Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ACOG Committee Opinion #697 Planned Home Birth

ACOG Committee Opinion #697 Planned Home Birth

Uploaded by

joselinrivero92Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- International Health Agencies Name ListDocument4 pagesInternational Health Agencies Name ListKailash Nagar67% (6)

- Mulanay Sa Pusod NG ParaiDocument3 pagesMulanay Sa Pusod NG ParaiLovelyn B. Oliveros67% (3)

- 01 Obstetrics in RuralDocument18 pages01 Obstetrics in Ruralkareen llalle puenteNo ratings yet

- Facts+figures 2017 PDFDocument65 pagesFacts+figures 2017 PDFElton LeightonNo ratings yet

- F8 Reading-Birth To Death Symposium-Home BirthDocument5 pagesF8 Reading-Birth To Death Symposium-Home Birthemkay1234No ratings yet

- 80 (11) 871 1 PDFDocument5 pages80 (11) 871 1 PDFMahlina Nur LailiNo ratings yet

- Low-Risk Planned Caesarean Versus Planned Vaginal Delivery at Term: Early and Late Infantile OutcomesDocument11 pagesLow-Risk Planned Caesarean Versus Planned Vaginal Delivery at Term: Early and Late Infantile OutcomesEduarda QuartinNo ratings yet

- Acog Committee Opinion: Cesarean Delivery On Maternal RequestDocument5 pagesAcog Committee Opinion: Cesarean Delivery On Maternal RequestfbihansipNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937810000815 JournallDocument12 pagesPi Is 0002937810000815 JournallRaisa AriesthaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 211Document25 pages2016 Article 211agus fetal mein feraldNo ratings yet

- Scientrfic Basis For The Content of Routine Antenatal CareDocument14 pagesScientrfic Basis For The Content of Routine Antenatal CareRusdySpotrNo ratings yet

- Home BirthDocument33 pagesHome BirthMarlon Royo100% (2)

- Laborinduction: Areviewof Currentmethods: Mildred M. RamirezDocument11 pagesLaborinduction: Areviewof Currentmethods: Mildred M. RamirezRolando DiazNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Care Consensus No2Document14 pagesObstetric Care Consensus No2Marco DiestraNo ratings yet

- Cesarienne Apres Declenchement Du TravailDocument9 pagesCesarienne Apres Declenchement Du TravailTchimon VodouheNo ratings yet

- Kehamilan EktopikDocument9 pagesKehamilan EktopikEka AfriliaNo ratings yet

- DP 203Document63 pagesDP 203charu parasherNo ratings yet

- Kohn 2019Document8 pagesKohn 2019Elita RahmaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Contraception: Knowledge and Attitudes of Family Physicians of A Teaching Hospital, Karachi, PakistanDocument6 pagesEmergency Contraception: Knowledge and Attitudes of Family Physicians of A Teaching Hospital, Karachi, PakistanNaveed AhmadNo ratings yet

- RPPH 16 32Document32 pagesRPPH 16 32forensik24mei koasdaringNo ratings yet

- Halliday 1997Document8 pagesHalliday 1997JohnnyNo ratings yet

- Piis0002937816321706 PDFDocument8 pagesPiis0002937816321706 PDFObgyn Unsrat2017No ratings yet

- BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth: Jodie M Dodd, Caroline A Crowther, Janet E Hiller, Ross R Haslam and Jeffrey S RobinsonDocument9 pagesBMC Pregnancy and Childbirth: Jodie M Dodd, Caroline A Crowther, Janet E Hiller, Ross R Haslam and Jeffrey S RobinsonSyahrullah Ramadhan UllaNo ratings yet

- PDF MaternityCarePtEngagementStrategiesIHADocument29 pagesPDF MaternityCarePtEngagementStrategiesIHAv_ratNo ratings yet

- Preterm Labor - AAFPDocument21 pagesPreterm Labor - AAFPfirdaus zaidiNo ratings yet

- Women's Health Care Physicians: Member Login Join Pay Dues Follow UsDocument24 pagesWomen's Health Care Physicians: Member Login Join Pay Dues Follow UsNazif Aiman IsmailNo ratings yet

- Safe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGDocument16 pagesSafe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGAryaNo ratings yet

- Chapter TwoDocument7 pagesChapter Twohanixasan2002No ratings yet

- Maternal JournalDocument7 pagesMaternal JournalMia MabaylanNo ratings yet

- Delays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional StudyDocument15 pagesDelays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional Studykaren paredes rojasNo ratings yet

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'670968655') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Document10 pagesP ('t':'3', 'I':'670968655') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Septi RahadianNo ratings yet

- Indications For Outpatient Antenatal Fetal Surveillance ACOGDocument62 pagesIndications For Outpatient Antenatal Fetal Surveillance ACOGagraisabelaNo ratings yet

- WHO Statement On Caesarean Section Rates: Executive SummaryDocument9 pagesWHO Statement On Caesarean Section Rates: Executive SummaryNanaNo ratings yet

- J Midwife Womens Health - 2021Document6 pagesJ Midwife Womens Health - 2021EvelynNo ratings yet

- Prevention of The FirstDocument4 pagesPrevention of The FirstJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Wiklund2012 (Indication)Document8 pagesWiklund2012 (Indication)Noah Borketey-laNo ratings yet

- Maternity Care in The UnitedDocument19 pagesMaternity Care in The United089 Eidmul Hasan ShakibNo ratings yet

- 9 PDFDocument9 pages9 PDFAnggun SetiawatiNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Unplanned Out-Of-Hospital Attende by Paramedics 2018Document10 pagesEpidemiology of Unplanned Out-Of-Hospital Attende by Paramedics 2018Angel ArreolaNo ratings yet

- Battaglia JMPDocument95 pagesBattaglia JMPtegarpradanaNo ratings yet

- ÓbitoDocument111 pagesÓbitoDamián López RangelNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Fetal AssessmentDocument7 pagesAntenatal Fetal AssessmentFitriana Nur RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Following Miscarriage What Is The Optimum Interpregnancy IntervalDocument3 pagesPregnancy Following Miscarriage What Is The Optimum Interpregnancy IntervallcmurilloNo ratings yet

- Feto-Maternal Outcomes Following Caesarean SectionDocument6 pagesFeto-Maternal Outcomes Following Caesarean Sectionkirandhami1520No ratings yet

- Vbac Success 2013Document6 pagesVbac Success 2013040193izmNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937816462733Document6 pagesPi Is 0002937816462733muhammad maadaNo ratings yet

- Debate GUIDE PDFDocument8 pagesDebate GUIDE PDFBlesse PateñoNo ratings yet

- Model PersalinanDocument9 pagesModel PersalinanAri Wahyu DewantiNo ratings yet

- 1471 2393 13 31 PDFDocument6 pages1471 2393 13 31 PDFTriponiaNo ratings yet

- Paving The Way For A Gold Standard of Care For Infertility Treatment: Improving Outcomes Through Standardization of Laboratory ProceduresDocument9 pagesPaving The Way For A Gold Standard of Care For Infertility Treatment: Improving Outcomes Through Standardization of Laboratory Proceduresagus fetal mein feraldNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument10 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyMBMNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002937813022096Document8 pagesPIIS0002937813022096harold.atmajaNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Implantation Failure-Update Overview OnDocument19 pagesRecurrent Implantation Failure-Update Overview Onn2763288100% (1)

- Del 153Document6 pagesDel 153Fan AccountNo ratings yet

- ACOG Management of Stillbirth PDFDocument14 pagesACOG Management of Stillbirth PDFLêMinhĐứcNo ratings yet

- Menu Script For The ReasearchDocument9 pagesMenu Script For The ReasearchHrithik SureshNo ratings yet

- Reading Part A CaesareanDocument6 pagesReading Part A Caesareanfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Abortion, Stillbirth, Miscarriage in Ghana-1Document10 pagesAbortion, Stillbirth, Miscarriage in Ghana-1brijitcujoNo ratings yet

- None 3Document7 pagesNone 3Sy Yessy ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception and Short Interpregnancy Intervals (Diah Safitri)Document5 pagesAssociations Between Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception and Short Interpregnancy Intervals (Diah Safitri)Diah SafitriNo ratings yet

- Preconception Health and Care: A Life Course ApproachFrom EverandPreconception Health and Care: A Life Course ApproachJill ShaweNo ratings yet

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientFrom EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsFrom EverandPregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsNo ratings yet

- Diminished Ovarian Reserve and Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Current Research and Clinical ManagementFrom EverandDiminished Ovarian Reserve and Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Current Research and Clinical ManagementOrhan BukulmezNo ratings yet

- Notice: Medicare and Medicaid: Program Issuances and Coverage Decisions Quarterly ListingDocument41 pagesNotice: Medicare and Medicaid: Program Issuances and Coverage Decisions Quarterly ListingJustia.comNo ratings yet

- DR DHANASARI - Dokter Dan Dokter Layanan Primer PDFDocument36 pagesDR DHANASARI - Dokter Dan Dokter Layanan Primer PDFDwi cahyaniNo ratings yet

- Vijaya College of Nursing: Course Subject Unit Bio-Psycho Social PathophysiologyDocument3 pagesVijaya College of Nursing: Course Subject Unit Bio-Psycho Social PathophysiologyReshma Rinu50% (2)

- Hospital Planning and Design-Unit 1Document25 pagesHospital Planning and Design-Unit 1Timothy Suraj0% (1)

- 6 Hospital Management Strategies To Thrive in Todays Healthcare EnvironmentDocument1 page6 Hospital Management Strategies To Thrive in Todays Healthcare EnvironmentSMTH PlanningNo ratings yet

- Issues and Trends in Chronic CareDocument10 pagesIssues and Trends in Chronic CareElaine Dionisio TanNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Summative AssessmentDocument4 pagesWeek 5 Summative AssessmentKirby LewisNo ratings yet

- Linking Licensure Examinations To Nursing Practice Through Task Analysis: A Case For BotswanaDocument15 pagesLinking Licensure Examinations To Nursing Practice Through Task Analysis: A Case For BotswanaJhpiegoNo ratings yet

- Calling Doctors Latest UpdateDocument4 pagesCalling Doctors Latest UpdateAvinash ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Monthly Service Delivery Report FormDocument4 pagesMonthly Service Delivery Report FormIyaadanNo ratings yet

- Monthly Accomplishment Report Front PageDocument2 pagesMonthly Accomplishment Report Front PageRgn Mckl100% (1)

- Meaningful Use Business Analyst in Atlanta GA Resume Margaret ChandlerDocument3 pagesMeaningful Use Business Analyst in Atlanta GA Resume Margaret ChandlerMargaretChandlerNo ratings yet

- Case 3Document3 pagesCase 3Aman SankrityayanNo ratings yet

- Report On The High Healthcare Costs in IndiaDocument3 pagesReport On The High Healthcare Costs in IndiaSydkoNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6412 Assessment 1 Policy and Guidelines For The Informatics Staff - Making Decisions To Use Informatics Systems in PracticeDocument6 pagesNURS FPX 6412 Assessment 1 Policy and Guidelines For The Informatics Staff - Making Decisions To Use Informatics Systems in Practicezadem5266No ratings yet

- K Park Community Medicine 22 Editionpdf PDFDocument2 pagesK Park Community Medicine 22 Editionpdf PDFchain singh janviNo ratings yet

- Finalized HSR Group Assignment GMPH Students SDocument21 pagesFinalized HSR Group Assignment GMPH Students Shabtamu birhanuNo ratings yet

- PNLE Community Health Nursing Exam 1 With Answer & RationaleDocument5 pagesPNLE Community Health Nursing Exam 1 With Answer & RationaleSharNo ratings yet

- EpidemiologyDocument2 pagesEpidemiologytzuquinoNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Prenatal Care Yoga Terhadap Pengurangan Keluhan Ketidaknyamanan Ibu Hamil Trimester Iii Di Puskesmas Putri Ayukota JambiDocument6 pagesPengaruh Prenatal Care Yoga Terhadap Pengurangan Keluhan Ketidaknyamanan Ibu Hamil Trimester Iii Di Puskesmas Putri Ayukota JambiWahyu ItuwsiTriNo ratings yet

- Building Learning Commitment - Perdalin-Project HopeDocument18 pagesBuilding Learning Commitment - Perdalin-Project Hopesusy kusumawardaniNo ratings yet

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Document4 pagesTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonNo ratings yet

- Municipal Health Office Municipality of Claveria, CagayanDocument2 pagesMunicipal Health Office Municipality of Claveria, CagayanSophia Kaye AguinaldoNo ratings yet

- Health Officer Resume 5Document2 pagesHealth Officer Resume 5EsamNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDocument20 pagesMacroeconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDarrell Davis100% (21)

- Office of The Chief Medical Officer Bandipora. OrderDocument2 pagesOffice of The Chief Medical Officer Bandipora. OrderZËÚŠ GØDLĒŠŠNo ratings yet

ACOG Committee Opinion #697 Planned Home Birth

ACOG Committee Opinion #697 Planned Home Birth

Uploaded by

joselinrivero92Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ACOG Committee Opinion #697 Planned Home Birth

ACOG Committee Opinion #697 Planned Home Birth

Uploaded by

joselinrivero92Copyright:

Available Formats

interim update

The American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists

WOMEN’S HEALTH CARE PHYSICIANS

COMMITTEE OPINION

Number 697 • April 2017 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 669, August 2016)

Committee on Obstetric Practice

This Committee Opinion was developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric

Practice in collaboration with committee members Joseph R. Wax, MD, and William H. Barth Jr, MD.

This document reflects emerging clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued and is subject to change. The information

should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed.

INTERIM UPDATE: This Committee Opinion is updated as highlighted to reflect a limited, focused change in the pre-

sentation of data regarding perinatal mortality in planned home births.

Planned Home Birth

ABSTRACT: In the United States, approximately 35,000 births (0.9%) per year occur in the home.

Approximately one fourth of these births are unplanned or unattended. Although the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists believes that hospitals and accredited birth centers are the safest settings for

birth, each woman has the right to make a medically informed decision about delivery. Importantly, women should

be informed that several factors are critical to reducing perinatal mortality rates and achieving favorable home birth

outcomes. These factors include the appropriate selection of candidates for home birth; the availability of a certi-

fied nurse–midwife, certified midwife or midwife whose education and licensure meet International Confederation

of Midwives’ Global Standards for Midwifery Education, or physician practicing obstetrics within an integrated and

regulated health system; ready access to consultation; and access to safe and timely transport to nearby hospi-

tals. The Committee on Obstetric Practice considers fetal malpresentation, multiple gestation, or prior cesarean

delivery to be an absolute contraindication to planned home birth.

Recommendations nurse–midwife, certified midwife or midwife

whose education and licensure meet International

• Women inquiring about planned home birth should

Confederation of Midwives’ Global Standards for

be informed of its risks and benefits based on recent

Midwifery Education, or physician practicing obstet-

evidence. Specifically, they should be informed that

rics within an integrated and regulated health system;

although planned home birth is associated with

ready access to consultation; and access to safe and

fewer maternal interventions than planned hospital

timely transport to nearby hospitals.

birth, it also is associated with a more than twofold

increased risk of perinatal death (1–2 in 1,000) and a • The Committee on Obstetric Practice considers fetal

threefold increased risk of neonatal seizures or seri- malpresentation, multiple gestation, or prior cesar-

ous neurologic dysfunction (0.4–0.6 in 1,000). These ean delivery to be an absolute contraindication to

observations may reflect fewer obstetric risk fac- planned home birth.

tors among women planning home birth compared In the United States, approximately 35,000 births (0.9%)

with those planning hospital birth. Although the per year occur in the home (1). Approximately one fourth

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of these births are unplanned or unattended (2). Among

(the College) believes that hospitals and accredited women who originally intend to give birth in a hospital or

birth centers are the safest settings for birth, each those who make no provisions for professional care dur-

woman has the right to make a medically informed ing childbirth, home births are associated with high rates

decision about delivery. of perinatal and neonatal mortality (3). The relative risk

• Women should be informed that several factors are versus benefit of a planned home birth, however, remains

critical to reducing perinatal mortality rates and the subject of debate.

achieving favorable home birth outcomes. These High-quality evidence that can inform this debate is

factors include the appropriate selection of candi- limited. To date, there have been no adequate random-

dates for home birth; the availability of a certified ized clinical trials of planned home birth (4). In developed

countries where home birth is more common than in interventions and the hospital atmosphere (30). Recent

the United States, attempts to conduct such studies have studies have found that when compared with planned

been unsuccessful, largely because pregnant women hospital births, planned home births are associated with

have been reluctant to participate in clinical trials that fewer maternal interventions, including labor induction

involve randomization to home or hospital birth (5, 6). or augmentation, regional analgesia, electronic fetal heart

Consequently, most information on planned home births rate monitoring, episiotomy, operative vaginal delivery,

comes from observational studies. Observational studies and cesarean delivery (Table 1). Planned home births

of planned home birth often are limited by methodologi- also are associated with fewer vaginal, perineal, and third-

cal problems, including small sample sizes (7–10); lack of degree or fourth-degree lacerations and less maternal

an appropriate control group (11–15); reliance on birth infectious morbidity (18, 27, 31, 32). These observations

certificate data with inherent ascertainment problems may reflect fewer obstetric risk factors among women

(2, 16–18); reliance on voluntary submission of data planning home births compared with those planning

or self-reporting (7, 12, 14, 15, 19); limited ability to hospital births. Parous women comprise a larger propor-

distinguish accurately between planned and unplanned tion of those planning out-of-hospital births (27, 32).

home births (16, 20); variation in the skill, training, and Compared with nulliparous women, parous women col-

certification of the birth attendant (14–16, 21); and an lectively experience significantly lower rates of obstetric

inability to account for and accurately attribute adverse intervention, maternal morbidity, and neonatal mor-

outcomes associated with antepartum or intrapartum bidity and mortality, regardless of birth location. Those

transfers (8, 16, 22). Some recent observational studies planning home births also are more likely to deliver in

overcome many of these limitations, describing planned that setting than nulliparous women (15, 27, 33). For

home births within tightly regulated and integrated these reasons, recommendations regarding the intrapar-

health care systems, attended by highly trained licensed tum care of healthy nulliparous and parous women may

midwives with ready access to consultation and safe, differ outside of the United States (29). Also, proportion-

timely transport to nearby hospitals (7, 8, 10, 11, 16, 19, ately more home births are attended by midwives than

23–28). However, these data may not be generalizable planned hospital births, and randomized trials show that

to many birth settings in the United States where such midwife-led care is associated with fewer intrapartum

integrated services are lacking. For the same reasons, interventions (34).

clinical guidelines for the intrapartum care of women Strict criteria are necessary to guide selection of

in the United States that are based on these results and appropriate candidates for planned home birth. In the

are supportive of planned home birth for low-risk term United States, for example, where selection criteria may

pregnancies also may not currently be generalizable (29). not be applied broadly, intrapartum (1.3 in 1,000) and

Furthermore, no studies are of sufficient size to compare neonatal (0.76 in 1,000) deaths among low-risk women

maternal mortality between planned home and hospital planning home birth are more common than expected

birth and few, when considered alone, are large enough to when compared with rates for low-risk women plan-

compare perinatal and neonatal mortality rates. Despite ning hospital delivery (0.4 in 1,000 and 0.17 in 1,000,

these limitations, when viewed collectively, recent reports respectively), consistent with the findings of an earlier

clarify a number of important issues regarding the mater- meta-analysis (15, 31, 33). Additional evidence from the

nal and newborn outcomes of planned home birth when United States shows that planned home birth of a breech-

compared with planned hospital births. presenting fetus is associated with an intrapartum

Women planning a home birth may do so for a mortality rate of 13.5 in 1,000 and neonatal mortality

number of reasons, often out of a desire to avoid medical rate of 9.2 in 1,000 (15). United States data limited to

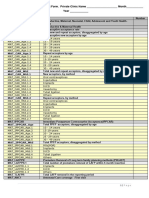

Table 1. Maternal Events Associated With U.S. Planned Out-of-Hospital Births Versus Hospital Births ^

Planned Out-of- Planned

Hospital Birth Hospital Birth Adjusted

Event (Events per 1,000 births) (Events per 1,000 births) Odds Ratio 95% CI

Labor induction 48 304 0.11 0.09–0.12

Labor augmentation 75 263 0.21 0.19–0.24

Operative vaginal delivery 10 35 0.24 0.17–0.34

Cesarean delivery 53 247 0.18 0.16–0.22

Blood transfusion/hemorrhage 6 4 1.91 1.25–2.93

Severe perineal lacerations 9 13 0.69 0.49–0.98

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Data from Snowden JM, Tilden EL, Snyder J, Quigley B, Caughey AB, Cheng YW. Planned out-of-hospital birth and birth outcomes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2642–53.

2 Committee Opinion No. 697

singleton-term pregnancies demonstrate a higher risk of more limited should be considered carefully by patients

5-minute Apgar scores less than 7, less than 4, and 0; peri- and their health care providers. In such situations, the

natal death; and neonatal seizures with planned home best alternative may be to refer patients to facilities with

birth, although the absolute risks remain low (Table 2) available resources. Health care providers and insurers

(17, 18, 32). should do all they can to facilitate transfer of care or

Although patients with one prior cesarean deliv- comanagement in support of a desired TOLAC, and such

ery were considered candidates for home birth in two plans should be initiated early in the course of antenatal

Canadian studies, details of the outcomes specific to care (39).

patients attempting home vaginal birth after cesarean Recent cohort studies reporting comparable peri-

delivery were not provided (24, 25). In England, women natal mortality rates among planned home and hospital

planning a home trial of labor after cesarean delivery births describe the use of strict selection criteria for

(TOLAC) exhibited fewer obstetric risk factors, were appropriate candidates (23–25). These criteria include

more likely to deliver vaginally, and experienced similar the absence of any preexisting maternal disease, the

maternal and perinatal outcomes compared with those absence of significant disease arising during the preg-

planning an in-hospital TOLAC (35). In contrast, a nancy, a singleton fetus, a cephalic presentation, gesta-

recent U.S. study showed that planned home TOLAC tional age greater than 36–37 completed weeks and less

was associated with an intrapartum fetal death rate of than 41–42 completed weeks of pregnancy, labor that is

2.9 in 1,000, which is higher than the reported rate of spontaneous or induced as an outpatient, and that the

0.13 in 1,000 for planned hospital TOLAC (36, 37). This patient has not been transferred from another referring

observation is of particular concern in light of the increas- hospital. In the absence of such criteria, planned home

ing number of home vaginal births after cesarean delivery birth is clearly associated with a higher risk of perinatal

(38). Because of the risks associated with TOLAC, and death (15, 26, 40). The Committee on Obstetric Practice

specifically considering that uterine rupture and other considers fetal malpresentation, multiple gestation, or

complications may be unpredictable, the College rec- prior cesarean delivery to be an absolute contraindication

ommends that TOLAC be undertaken in facilities with to planned home birth.

trained staff and the ability to begin an emergency cesar- Another factor influencing the safety of planned

ean delivery within a time interval that best incorporates home birth is the availability of safe and timely intra-

maternal and fetal risks and benefits with the provision partum transfer of the laboring patient. The reported

of emergency care. risk of needing an intrapartum transport to a hospital is

The decision to offer and pursue TOLAC in a setting 23–37% for nulliparous women and 4 –9% for multipar-

in which the option of immediate cesarean delivery is ous women. Most of these intrapartum transports are

Table 2. Adverse Perinatal Events Associated With U.S. Planned Home Births Versus Hospital Births ^

Planned Home Birth Hospital Birth

Event (Events per 1,000 Births) (Events per 1,000 Births) Odds Ratio 95% CI

5-minute Apgar score

<7 24.2* 11.7* 2.42* 2.13–2.74*

†§ † †

23 18 1.31 1.04–1.66†

<4 3.7* 2.43* 1.87* 1.36–2.58*

6† § 4† 1.56† 0.98–2.47*

0 1.63‡ 0.16‡ 10.55‡ 8.62–12.93‡

Neonatal seizures (or serious 0.58* 0.22* 3.08* 1.44–6.58*

neurologic dysfunction‡) 0.86‡ 0.22‡ 3.80‡ 2.80–5.16‡

1.3† § 0.4† 3.60† 1.36–9.50†

†§ † †

Perinatal mortality (fetal death 3.9 1.8 2.43 1.37–4.30†

and neonatal mortality)

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

*Cheng YW, Snowden JM, King TL, Caughey AB. Selected perinatal outcomes associated with planned home births in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:

325.e1–8.

†

Snowden JM, Tilden EL, Snyder J, Quigley B, Caughey AB, Cheng YW. Planned out-of-hospital birth and birth outcomes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2642–53.

‡

Grunebaum A, McCullough LB, Sapra KJ, Brent RL, Levene MI, Arabin B, et al. Apgar score of 0 at 5 minutes and neonatal seizures or serious neurologic dysfunction in

relation to birth setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:323.e1–6.

§

Includes planned birth center and home births.

Committee Opinion No. 697 3

for lack of progress in labor, nonreassuring fetal status, of a certified nurse–midwife, certified midwife or mid-

need for pain relief, hypertension, bleeding, and fetal wife whose education and licensure meet International

malposition (27, 41, 42). The relatively low perina- Confederation of Midwives’ Global Standards for

tal and newborn mortality rates reported for planned Midwifery Education, or physician practicing obstetrics

home births from Ontario, British Columbia, and the within an integrated and regulated health system; ready

Netherlands were from highly integrated health care access to consultation; and access to safe and timely trans-

systems with established criteria and provisions for port to nearby hospitals.

emergency intrapartum transport (23–25). Cohort stud-

ies conducted in areas without such integrated systems For More Information

and those where the receiving hospital may be remote, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

with the potential for delayed or prolonged intrapartum has identified additional resources on topics related to this

transport, generally report higher rates of intrapartum document that may be helpful for ob-gyns, other health

and neonatal death (6, 9, 11, 15, 22). Even in regions care providers, and patients. You may view these resources

with integrated care systems, increasing distance from at www.acog.org/More-Info/PlannedHomeBirth.

the hospital is associated with longer transfer times and

These resources are for information only and are not

the potential for increased adverse outcomes. However,

meant to be comprehensive. Referral to these resources

no specific thresholds for time or distance have been

does not imply the American College of Obstetricians

identified (43, 44). The College believes that the avail-

and Gynecologists’ endorsement of the organization, the

ability of timely transfer and an existing arrangement

organization’s website, or the content of the resource. The

with a hospital for such transfers is a requirement for

resources may change without notice.

consideration of a home birth. When antepartum, intra-

partum, or postpartum transfer of a woman from home

to a hospital occurs, the receiving health care provider References

should maintain a nonjudgmental demeanor with regard 1. MacDorman MF, Matthews TJ, Declercq E. Trends in out-

to the woman and those individuals accompanying her of-hospital births in the United States, 1990-2012. NCHS

to the hospital. Data Brief 2014;144:1–8. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

A characteristic common to those cohort studies 2. Wax JR, Pinette MG, Cartin A, Blackstone J. Maternal

reporting comparable rates of perinatal mortality is the and newborn morbidity by birth facility among selected

provision of care by uniformly highly educated and United States 2006 low-risk births. Am J Obstet Gynecol

trained certified midwives who are well integrated into 2010;202:152.e1–5. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

the health care system (23–25, 27). In the United States, 3. Collaborative survey of perinatal loss in planned and

certified nurse–midwives and certified midwives are unplanned home births. Northern Region Perinatal

certified by the American Midwifery Certification Board. Mortality Survey Coordinating Group. BMJ 1996;313:

This certification depends on the completion of an 1306–9. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

accredited educational program and meeting standards 4. Olsen O, Clausen JA. Planned hospital birth versus planned

set by the American Midwifery Certification Board. In home birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

comparison with planned out-of-hospital births attended 2012, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD000352. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

by American Midwifery Certification Board-certified CD000352.pub2. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

midwives, planned out-of-hospital births by midwives 5. Dowswell T, Thornton JG, Hewison J, Lilford RJ, Raisler J,

who do not hold this certification have higher perinatal Macfarlane A, et al. Should there be a trial of home ver-

morbidity and mortality rates (18). At this time, for qual- sus hospital delivery in the United Kingdom? BMJ 1996;

ity and safety reasons, the College specifically supports 312:753–7. [PubMed] [Full Text]^

the provision of care by midwives who are certified by the 6. Hendrix M, Van Horck M, Moreta D, Nieman F,

American Midwifery Certification Board (or its predeces- Nieuwenhuijze M, Severens J, et al. Why women do not

sor organizations) or whose education and licensure meet accept randomisation for place of birth: feasibility of a RCT

the International Confederation of Midwives Global in The Netherlands. BJOG 2009;116:537–42; discussion

Standards for Midwifery Education. The College does not 542–4. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

support provision of care by midwives who do not meet 7. Wiegers TA, Keirse MJ, van der Zee J, Berghs GA. Outcome

these standards. of planned home and planned hospital births in low risk

Although the College believes that hospitals and pregnancies: prospective study in midwifery practices in

accredited birth centers are the safest settings for birth, The Netherlands. BMJ 1996;313:1309–13. [PubMed] [Full

each woman has the right to make a medically informed Text] ^

decision about delivery (45). Importantly, women should 8. Ackermann-Liebrich U, Voegeli T, Gunter-Witt K, Kunz

be informed that several factors are critical to reducing I, Zullig M, Schindler C, et al. Home versus hospital deliv-

perinatal mortality rates and achieving favorable home eries: follow up study of matched pairs for procedures

birth outcomes. These factors include the appropriate and outcome. Zurich Study Team. BMJ 1996;313:1313–8.

selection of candidates for home birth; the availability [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

4 Committee Opinion No. 697

9. Davies J, Hey E, Reid W, Young G. Prospective regional bidity up to 28 days after birth among 743 070 low-

study of planned home births. Home Birth Study Steering risk planned home and hospital births: a cohort study

Group. BMJ 1996;313:1302–6. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^ based on three merged national perinatal databases. BJOG

10. Janssen PA, Lee SK, Ryan EM, Etches DJ, Farquharson DF, 2015;122:720–8. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

Peacock D, et al. Outcomes of planned home births versus 24. Janssen PA, Saxell L, Page LA, Klein MC, Liston RM, Lee

planned hospital births after regulation of midwifery in SK. Outcomes of planned home birth with registered mid-

British Columbia. CMAJ 2002;166:315–23. [PubMed] [Full wife versus planned hospital birth with midwife or physi-

Text] ^ cian [published erratum appears in CMAJ 2009;181:617].

11. Woodcock HC, Read AW, Bower C, Stanley FJ, Moore CMAJ 2009;181:377–83. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

DJ. A matched cohort study of planned home and hospital 25. Hutton EK, Reitsma AH, Kaufman K. Outcomes associated

births in Western Australia 1981-1987 [published erratum with planned home and planned hospital births in low-risk

appears in Midwifery 1995;11:99]. Midwifery 1994;10: women attended by midwives in Ontario, Canada, 2003-

125–35. [PubMed] [Full Text]^ 2006: a retrospective cohort study. Birth 2009;36:180–9.

12. Anderson RE, Murphy PA. Outcomes of 11,788 planned [PubMed] ^

home births attended by certified nurse-midwives. A ret- 26. Kennare RM, Keirse MJ, Tucker GR, Chan AC. Planned

rospective descriptive study. J Nurse Midwifery 1995;40: home and hospital births in South Australia, 1991-2006:

483–92. [PubMed] ^ differences in outcomes. Med J Aust 2010;192:76–80.

13. Murphy PA, Fullerton J. Outcomes of intended home [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

births in nurse-midwifery practice: a prospective descrip- 27. Brocklehurst P, Hardy P, Hollowell J, Linsell L, Macfarlane

tive study. Obstet Gynecol 1998;92:461–70. [PubMed] ^ A, McCourt C, et al. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by

14. Johnson KC, Daviss BA. Outcomes of planned home births planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk

with certified professional midwives: large prospective pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective

study in North America. BMJ 2005;330:1416. [PubMed] cohort study. Birthplace in England Collaborative Group.

[Full Text] ^ BMJ 2011;343:d7400. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

15. Cheyney M, Bovbjerg M, Everson C, Gordon W, Hannibal 28. Hutton EK, Cappelletti A, Reitsma AH, Simioni J, Horne J,

D, Vedam S. Outcomes of care for 16,924 planned home McGregor C, et al. Outcomes associated with planned place

births in the United States: the Midwives Alliance of North of birth among women with low-risk pregnancies. CMAJ

America Statistics Project, 2004 to 2009. J Midwifery 2016;188:E80–90. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

Womens Health 2014;59:17–27. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^ 29. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

16. Pang JW, Heffelfinger JD, Huang GJ, Benedetti TJ, Weiss Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies. Clinical

NS. Outcomes of planned home births in Washington State: Guideline 190. London: NICE; 2014. Available at: https://

1989-1996. Obstet Gynecol 2002;100:253–9. [PubMed] www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

[Obstetrics & Gynecology] ^ ^

17. Grunebaum A, McCullough LB, Sapra KJ, Brent RL, 30. Neuhaus W, Piroth C, Kiencke P, Gohring UJ, Mallman P.

Levene MI, Arabin B, et al. Apgar score of 0 at 5 minutes A psychosocial analysis of women planning birth outside

and neonatal seizures or serious neurologic dysfunction in hospital. J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;22:143–9. [PubMed] ^

relation to birth setting. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209: 31. Wax JR, Lucas FL, Lamont M, Pinette MG, Cartin A,

323.e1–6. [PubMed] [Full Text]^ Blackstone J. Maternal and newborn outcomes in planned

18. Cheng YW, Snowden JM, King TL, Caughey AB. Selected home birth vs planned hospital births: a metaanalysis. Am

perinatal outcomes associated with planned home births in J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:243.e1–8. [PubMed] [Full Text]

the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:325.e1–8. ^

[PubMed] [Full Text] ^ 32. Snowden JM, Tilden EL, Snyder J, Quigley B, Caughey AB,

19. Lindgren HE, Radestad IJ, Christensson K, Hildingsson Cheng YW. Planned out-of-hospital birth and birth out-

IM. Outcome of planned home births compared to comes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2642–53. [PubMed] [Full

hospital births in Sweden between 1992 and 2004. A Text] ^

population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol

33. Worley KC, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. The prognosis for

Scand 2008;87:751–9. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

spontaneous labor in women with uncomplicated term

20. Mori R, Dougherty M, Whittle M. An estimation of pregnancies: implications for cesarean delivery on mater-

intrapartum-related perinatal mortality rates for booked nal request. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:812–6. [PubMed]

home births in England and Wales between 1994 and [Obstetrics & Gynecology] ^

2003 [published erratum appears in BJOG 2008;115:1590].

BJOG 2008;115:554–9. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^ 34. Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D.

Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of

21. Schramm WF, Barnes DE, Bakewell JM. Neonatal mortal- care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database of

ity in Missouri home births, 1978-84. Am J Public Health Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD004667.

1987;77:930–5. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^ DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub4. [PubMed] [Full

22. Parratt J, Johnston J. Planned homebirths in Victoria, 1995- Text] ^

1998. Aust J Midwifery 2002;15:16–25. [PubMed] ^ 35. Rowe R, Li Y, Knight M, Brocklehurst P, Hollowell J.

23. de Jonge A, Geerts CC, van der Goes BY, Mol BW, Maternal and perinatal outcomes in women planning

Buitendijk SE, Nijhuis JG. Perinatal mortality and mor- vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) at home in England:

Committee Opinion No. 697 5

secondary analysis of the Birthplace national prospective 43. Paranjothy S, Watkins WJ, Rolfe K, Adappa R, Gong Y,

cohort study. BJOG 2015; DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.13546. Dunstan F, et al. Perinatal outcomes and travel time from

[PubMed] [Full Text] ^ home to hospital: Welsh data from 1995 to 2009. Acta

36. Cox KJ, Bovbjerg ML, Cheyney M, Leeman LM. Planned Paediatr 2014;103:e522–7. [PubMed] ^

home VBAC in the United States, 2004-2009: outcomes, 44. Rowe RE, Townend J, Brocklehurst P, Knight M,

maternity care practices, and implications for shared deci- Macfarlane A, McCourt C, et al. Duration and urgency of

sion making. Birth 2015;42:299–308. [PubMed] [Full Text] transfer in births planned at home and in freestanding mid-

^ wifery units in England: secondary analysis of the birth-

37. Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Leindecker place national prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy

S, Varner MW, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes Childbirth 2013;13:224. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean deliv- 45. Informed consent. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 439.

ery. National Institute of Child Health and Human American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 114:401–8. [PubMed] ^

N Engl J Med 2004;351:2581–9. [PubMed] [Full Text] ^

38. MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Mathews TJ, Stotland N.

Trends and characteristics of home vaginal birth after

cesarean delivery in the United States and selected States.

Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:737–44. [PubMed] [Obstetrics &

Gynecology] ^

39. Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. ACOG

Practice Bulletin No. 115. American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:450–63. Copyright April 2017 by the American College of Obstetricians and

[PubMed] ^ Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may

be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the Internet,

40. Bastian H, Keirse MJ, Lancaster PA. Perinatal death asso- or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

ciated with planned home birth in Australia: population photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permis-

based study. BMJ 1998;317:384–8. [PubMed] [Full Text] sion from the publisher.

^ Requests for authorization to make photocopies should be directed

41. Wax JR, Pinette MG, Cartin A. Home versus hospital to Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA

01923, (978) 750-8400.

birth—process and outcome. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2010;

65:132–40. [PubMed] ^ ISSN 1074-861X

42. Blix E, Kumle M, Kjaergaard H, Oian P, Lindgren HE. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Transfer to hospital in planned home births: a systematic 409 12th Street, SW, PO Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920

review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:179. [PubMed] Planned home birth. Committee Opinion No. 697. American College of

[Full Text] ^ Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:e117–22.

6 Committee Opinion No. 697

You might also like

- International Health Agencies Name ListDocument4 pagesInternational Health Agencies Name ListKailash Nagar67% (6)

- Mulanay Sa Pusod NG ParaiDocument3 pagesMulanay Sa Pusod NG ParaiLovelyn B. Oliveros67% (3)

- 01 Obstetrics in RuralDocument18 pages01 Obstetrics in Ruralkareen llalle puenteNo ratings yet

- Facts+figures 2017 PDFDocument65 pagesFacts+figures 2017 PDFElton LeightonNo ratings yet

- F8 Reading-Birth To Death Symposium-Home BirthDocument5 pagesF8 Reading-Birth To Death Symposium-Home Birthemkay1234No ratings yet

- 80 (11) 871 1 PDFDocument5 pages80 (11) 871 1 PDFMahlina Nur LailiNo ratings yet

- Low-Risk Planned Caesarean Versus Planned Vaginal Delivery at Term: Early and Late Infantile OutcomesDocument11 pagesLow-Risk Planned Caesarean Versus Planned Vaginal Delivery at Term: Early and Late Infantile OutcomesEduarda QuartinNo ratings yet

- Acog Committee Opinion: Cesarean Delivery On Maternal RequestDocument5 pagesAcog Committee Opinion: Cesarean Delivery On Maternal RequestfbihansipNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937810000815 JournallDocument12 pagesPi Is 0002937810000815 JournallRaisa AriesthaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 211Document25 pages2016 Article 211agus fetal mein feraldNo ratings yet

- Scientrfic Basis For The Content of Routine Antenatal CareDocument14 pagesScientrfic Basis For The Content of Routine Antenatal CareRusdySpotrNo ratings yet

- Home BirthDocument33 pagesHome BirthMarlon Royo100% (2)

- Laborinduction: Areviewof Currentmethods: Mildred M. RamirezDocument11 pagesLaborinduction: Areviewof Currentmethods: Mildred M. RamirezRolando DiazNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Care Consensus No2Document14 pagesObstetric Care Consensus No2Marco DiestraNo ratings yet

- Cesarienne Apres Declenchement Du TravailDocument9 pagesCesarienne Apres Declenchement Du TravailTchimon VodouheNo ratings yet

- Kehamilan EktopikDocument9 pagesKehamilan EktopikEka AfriliaNo ratings yet

- DP 203Document63 pagesDP 203charu parasherNo ratings yet

- Kohn 2019Document8 pagesKohn 2019Elita RahmaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Contraception: Knowledge and Attitudes of Family Physicians of A Teaching Hospital, Karachi, PakistanDocument6 pagesEmergency Contraception: Knowledge and Attitudes of Family Physicians of A Teaching Hospital, Karachi, PakistanNaveed AhmadNo ratings yet

- RPPH 16 32Document32 pagesRPPH 16 32forensik24mei koasdaringNo ratings yet

- Halliday 1997Document8 pagesHalliday 1997JohnnyNo ratings yet

- Piis0002937816321706 PDFDocument8 pagesPiis0002937816321706 PDFObgyn Unsrat2017No ratings yet

- BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth: Jodie M Dodd, Caroline A Crowther, Janet E Hiller, Ross R Haslam and Jeffrey S RobinsonDocument9 pagesBMC Pregnancy and Childbirth: Jodie M Dodd, Caroline A Crowther, Janet E Hiller, Ross R Haslam and Jeffrey S RobinsonSyahrullah Ramadhan UllaNo ratings yet

- PDF MaternityCarePtEngagementStrategiesIHADocument29 pagesPDF MaternityCarePtEngagementStrategiesIHAv_ratNo ratings yet

- Preterm Labor - AAFPDocument21 pagesPreterm Labor - AAFPfirdaus zaidiNo ratings yet

- Women's Health Care Physicians: Member Login Join Pay Dues Follow UsDocument24 pagesWomen's Health Care Physicians: Member Login Join Pay Dues Follow UsNazif Aiman IsmailNo ratings yet

- Safe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGDocument16 pagesSafe Prevention of The Primary Cesarean Delivery - ACOGAryaNo ratings yet

- Chapter TwoDocument7 pagesChapter Twohanixasan2002No ratings yet

- Maternal JournalDocument7 pagesMaternal JournalMia MabaylanNo ratings yet

- Delays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional StudyDocument15 pagesDelays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional Studykaren paredes rojasNo ratings yet

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'670968655') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Document10 pagesP ('t':'3', 'I':'670968655') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Septi RahadianNo ratings yet

- Indications For Outpatient Antenatal Fetal Surveillance ACOGDocument62 pagesIndications For Outpatient Antenatal Fetal Surveillance ACOGagraisabelaNo ratings yet

- WHO Statement On Caesarean Section Rates: Executive SummaryDocument9 pagesWHO Statement On Caesarean Section Rates: Executive SummaryNanaNo ratings yet

- J Midwife Womens Health - 2021Document6 pagesJ Midwife Womens Health - 2021EvelynNo ratings yet

- Prevention of The FirstDocument4 pagesPrevention of The FirstJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Wiklund2012 (Indication)Document8 pagesWiklund2012 (Indication)Noah Borketey-laNo ratings yet

- Maternity Care in The UnitedDocument19 pagesMaternity Care in The United089 Eidmul Hasan ShakibNo ratings yet

- 9 PDFDocument9 pages9 PDFAnggun SetiawatiNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Unplanned Out-Of-Hospital Attende by Paramedics 2018Document10 pagesEpidemiology of Unplanned Out-Of-Hospital Attende by Paramedics 2018Angel ArreolaNo ratings yet

- Battaglia JMPDocument95 pagesBattaglia JMPtegarpradanaNo ratings yet

- ÓbitoDocument111 pagesÓbitoDamián López RangelNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Fetal AssessmentDocument7 pagesAntenatal Fetal AssessmentFitriana Nur RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Following Miscarriage What Is The Optimum Interpregnancy IntervalDocument3 pagesPregnancy Following Miscarriage What Is The Optimum Interpregnancy IntervallcmurilloNo ratings yet

- Feto-Maternal Outcomes Following Caesarean SectionDocument6 pagesFeto-Maternal Outcomes Following Caesarean Sectionkirandhami1520No ratings yet

- Vbac Success 2013Document6 pagesVbac Success 2013040193izmNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0002937816462733Document6 pagesPi Is 0002937816462733muhammad maadaNo ratings yet

- Debate GUIDE PDFDocument8 pagesDebate GUIDE PDFBlesse PateñoNo ratings yet

- Model PersalinanDocument9 pagesModel PersalinanAri Wahyu DewantiNo ratings yet

- 1471 2393 13 31 PDFDocument6 pages1471 2393 13 31 PDFTriponiaNo ratings yet

- Paving The Way For A Gold Standard of Care For Infertility Treatment: Improving Outcomes Through Standardization of Laboratory ProceduresDocument9 pagesPaving The Way For A Gold Standard of Care For Infertility Treatment: Improving Outcomes Through Standardization of Laboratory Proceduresagus fetal mein feraldNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument10 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyMBMNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002937813022096Document8 pagesPIIS0002937813022096harold.atmajaNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Implantation Failure-Update Overview OnDocument19 pagesRecurrent Implantation Failure-Update Overview Onn2763288100% (1)

- Del 153Document6 pagesDel 153Fan AccountNo ratings yet

- ACOG Management of Stillbirth PDFDocument14 pagesACOG Management of Stillbirth PDFLêMinhĐứcNo ratings yet

- Menu Script For The ReasearchDocument9 pagesMenu Script For The ReasearchHrithik SureshNo ratings yet

- Reading Part A CaesareanDocument6 pagesReading Part A Caesareanfernanda1rondelliNo ratings yet

- Abortion, Stillbirth, Miscarriage in Ghana-1Document10 pagesAbortion, Stillbirth, Miscarriage in Ghana-1brijitcujoNo ratings yet

- None 3Document7 pagesNone 3Sy Yessy ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception and Short Interpregnancy Intervals (Diah Safitri)Document5 pagesAssociations Between Immediate Postpartum Long-Acting Reversible Contraception and Short Interpregnancy Intervals (Diah Safitri)Diah SafitriNo ratings yet

- Preconception Health and Care: A Life Course ApproachFrom EverandPreconception Health and Care: A Life Course ApproachJill ShaweNo ratings yet

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientFrom EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsFrom EverandPregnancy Tests Explained (2Nd Edition): Current Trends of Antenatal TestsNo ratings yet

- Diminished Ovarian Reserve and Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Current Research and Clinical ManagementFrom EverandDiminished Ovarian Reserve and Assisted Reproductive Technologies: Current Research and Clinical ManagementOrhan BukulmezNo ratings yet

- Notice: Medicare and Medicaid: Program Issuances and Coverage Decisions Quarterly ListingDocument41 pagesNotice: Medicare and Medicaid: Program Issuances and Coverage Decisions Quarterly ListingJustia.comNo ratings yet

- DR DHANASARI - Dokter Dan Dokter Layanan Primer PDFDocument36 pagesDR DHANASARI - Dokter Dan Dokter Layanan Primer PDFDwi cahyaniNo ratings yet

- Vijaya College of Nursing: Course Subject Unit Bio-Psycho Social PathophysiologyDocument3 pagesVijaya College of Nursing: Course Subject Unit Bio-Psycho Social PathophysiologyReshma Rinu50% (2)

- Hospital Planning and Design-Unit 1Document25 pagesHospital Planning and Design-Unit 1Timothy Suraj0% (1)

- 6 Hospital Management Strategies To Thrive in Todays Healthcare EnvironmentDocument1 page6 Hospital Management Strategies To Thrive in Todays Healthcare EnvironmentSMTH PlanningNo ratings yet

- Issues and Trends in Chronic CareDocument10 pagesIssues and Trends in Chronic CareElaine Dionisio TanNo ratings yet

- Week 5 Summative AssessmentDocument4 pagesWeek 5 Summative AssessmentKirby LewisNo ratings yet

- Linking Licensure Examinations To Nursing Practice Through Task Analysis: A Case For BotswanaDocument15 pagesLinking Licensure Examinations To Nursing Practice Through Task Analysis: A Case For BotswanaJhpiegoNo ratings yet

- Calling Doctors Latest UpdateDocument4 pagesCalling Doctors Latest UpdateAvinash ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Monthly Service Delivery Report FormDocument4 pagesMonthly Service Delivery Report FormIyaadanNo ratings yet

- Monthly Accomplishment Report Front PageDocument2 pagesMonthly Accomplishment Report Front PageRgn Mckl100% (1)

- Meaningful Use Business Analyst in Atlanta GA Resume Margaret ChandlerDocument3 pagesMeaningful Use Business Analyst in Atlanta GA Resume Margaret ChandlerMargaretChandlerNo ratings yet

- Case 3Document3 pagesCase 3Aman SankrityayanNo ratings yet

- Report On The High Healthcare Costs in IndiaDocument3 pagesReport On The High Healthcare Costs in IndiaSydkoNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6412 Assessment 1 Policy and Guidelines For The Informatics Staff - Making Decisions To Use Informatics Systems in PracticeDocument6 pagesNURS FPX 6412 Assessment 1 Policy and Guidelines For The Informatics Staff - Making Decisions To Use Informatics Systems in Practicezadem5266No ratings yet

- K Park Community Medicine 22 Editionpdf PDFDocument2 pagesK Park Community Medicine 22 Editionpdf PDFchain singh janviNo ratings yet

- Finalized HSR Group Assignment GMPH Students SDocument21 pagesFinalized HSR Group Assignment GMPH Students Shabtamu birhanuNo ratings yet

- PNLE Community Health Nursing Exam 1 With Answer & RationaleDocument5 pagesPNLE Community Health Nursing Exam 1 With Answer & RationaleSharNo ratings yet

- EpidemiologyDocument2 pagesEpidemiologytzuquinoNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Prenatal Care Yoga Terhadap Pengurangan Keluhan Ketidaknyamanan Ibu Hamil Trimester Iii Di Puskesmas Putri Ayukota JambiDocument6 pagesPengaruh Prenatal Care Yoga Terhadap Pengurangan Keluhan Ketidaknyamanan Ibu Hamil Trimester Iii Di Puskesmas Putri Ayukota JambiWahyu ItuwsiTriNo ratings yet

- Building Learning Commitment - Perdalin-Project HopeDocument18 pagesBuilding Learning Commitment - Perdalin-Project Hopesusy kusumawardaniNo ratings yet

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Document4 pagesTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonNo ratings yet

- Municipal Health Office Municipality of Claveria, CagayanDocument2 pagesMunicipal Health Office Municipality of Claveria, CagayanSophia Kaye AguinaldoNo ratings yet

- Health Officer Resume 5Document2 pagesHealth Officer Resume 5EsamNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDocument20 pagesMacroeconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDarrell Davis100% (21)

- Office of The Chief Medical Officer Bandipora. OrderDocument2 pagesOffice of The Chief Medical Officer Bandipora. OrderZËÚŠ GØDLĒŠŠNo ratings yet