Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Corina. Naomi SCHOR. THIRD WOMAN

Corina. Naomi SCHOR. THIRD WOMAN

Uploaded by

r.emilianomorenoterrazasCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- TwoShakesComedies TMDocument16 pagesTwoShakesComedies TMareianoar100% (1)

- Bradmehldau Linernotes EcDocument5 pagesBradmehldau Linernotes EcBia CyrinoNo ratings yet

- The Perpetual Orgy: Flaubert and Madame BovaryFrom EverandThe Perpetual Orgy: Flaubert and Madame BovaryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Flannery O'Connor and The Violence of GraceDocument17 pagesFlannery O'Connor and The Violence of Graceisabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- Death Theme in LiteratureDocument3 pagesDeath Theme in Literaturemterrano0% (1)

- JAMESON, Walter Benjamin, or NostalgiaDocument18 pagesJAMESON, Walter Benjamin, or NostalgiaDaniel LesmesNo ratings yet

- Odyseuss Travels Graphic OrganizerDocument2 pagesOdyseuss Travels Graphic OrganizerFire1086100% (2)

- Artaud's Hélioglobale PDFDocument24 pagesArtaud's Hélioglobale PDFvolentriangleNo ratings yet

- Confession and Double ThoughtsDocument41 pagesConfession and Double ThoughtsJoe EscarchaNo ratings yet

- Blanchot Death of VirgilDocument16 pagesBlanchot Death of VirgilfrederickNo ratings yet

- J.M. COETZEE - On The Edge of RevelationDocument6 pagesJ.M. COETZEE - On The Edge of RevelationMarius DomnicaNo ratings yet

- Steel1981.plague Writing From Boccaccio To CamusDocument23 pagesSteel1981.plague Writing From Boccaccio To Camusje8aNo ratings yet

- "Oh, Do Not Ask, What Is It?'" in Eliot's The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock' and Gerontion'Document6 pages"Oh, Do Not Ask, What Is It?'" in Eliot's The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock' and Gerontion'Ipshita NathNo ratings yet

- A Simonidean Tale Commemorationand Coming To Terms With The Past Michel Tournier S Le Roi Des AulnesDocument23 pagesA Simonidean Tale Commemorationand Coming To Terms With The Past Michel Tournier S Le Roi Des AulnesGrace MalcomsonNo ratings yet

- Conditioning Adorno: After Auschwitz' NowDocument8 pagesConditioning Adorno: After Auschwitz' NowlaiosNo ratings yet

- 2008 MartinezDocument21 pages2008 MartinezDiego Pérez HernándezNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press, Royal Institute of Philosophy PhilosophyDocument14 pagesCambridge University Press, Royal Institute of Philosophy PhilosophyNegru CorneliuNo ratings yet

- Alkalay Gut PJ HarveyDocument30 pagesAlkalay Gut PJ HarveytenbrinkenNo ratings yet

- A Contradiction in Essence - Eroticism and The Creation of The SDocument36 pagesA Contradiction in Essence - Eroticism and The Creation of The SRonildo SansaoNo ratings yet

- Tenzin Dolma Lama 120351101Document7 pagesTenzin Dolma Lama 120351101Tenzin DolmaNo ratings yet

- Barthes, Roland - "The Death of The Author"Document8 pagesBarthes, Roland - "The Death of The Author"Anonymous aPGQwr5xNo ratings yet

- Heffernan Post Apocalyptic PaperDocument9 pagesHeffernan Post Apocalyptic PapersarajamalsweetNo ratings yet

- Tears of Eros 0872862224 9780872862227 - CompressDocument228 pagesTears of Eros 0872862224 9780872862227 - Compress성우진No ratings yet

- THE EVIL OF MODERNITY: JOSEPH CONRAD'S HEART OF DARKNESS AND FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA'S APOCALYPSE NOW Michel MaslowskiDocument17 pagesTHE EVIL OF MODERNITY: JOSEPH CONRAD'S HEART OF DARKNESS AND FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA'S APOCALYPSE NOW Michel MaslowskiAeosphorusNo ratings yet

- W. Land3Document16 pagesW. Land3Maroua TouilNo ratings yet

- PDF The End of Literature Hegel and The Contemporary Novel Francesco Campana Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF The End of Literature Hegel and The Contemporary Novel Francesco Campana Ebook Full Chapterwilliam.caldwell528100% (1)

- Studien Zur Deutschen Literatur: Band 90Document201 pagesStudien Zur Deutschen Literatur: Band 90EmilijaNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument39 pagesLiterature ReviewIbrahim Afganzai0% (1)

- Breathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaFrom EverandBreathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaNo ratings yet

- Orwell's CommediaDocument29 pagesOrwell's CommediacoilNo ratings yet

- Clark-Idealism and Dystopia en Tlon Uqbar Orbis TertiusDocument6 pagesClark-Idealism and Dystopia en Tlon Uqbar Orbis TertiusAnonymous dmAFqFAENo ratings yet

- Yale University Press Yale French Studies: This Content Downloaded From 128.84.126.163 On Fri, 25 Oct 2019 02:22:06 UTCDocument16 pagesYale University Press Yale French Studies: This Content Downloaded From 128.84.126.163 On Fri, 25 Oct 2019 02:22:06 UTCEfe RosarioNo ratings yet

- Myth and MannDocument16 pagesMyth and MannmporakishviliNo ratings yet

- 10 Titeeksha PathaniaDocument7 pages10 Titeeksha Pathaniabipolarbear872No ratings yet

- The Swerve - How The World Became Modern - by Stephen Greenblatt - Book Review - NYTimesDocument5 pagesThe Swerve - How The World Became Modern - by Stephen Greenblatt - Book Review - NYTimesAntónio Teixeira50% (2)

- Alfred de Vigny's - Eloa - A Modern Myth - Author(s) - Lucretia S. GruberDocument10 pagesAlfred de Vigny's - Eloa - A Modern Myth - Author(s) - Lucretia S. GruberCassio CarvalheiroNo ratings yet

- 03 MathewsDocument26 pages03 MathewsNatalia LauraNo ratings yet

- On Nature and the Goddess in Romantic and Post-Romantic LiteratureFrom EverandOn Nature and the Goddess in Romantic and Post-Romantic LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Writing at The Limits of Genre Danielle Collobert S Poetics of TransgressionDocument12 pagesWriting at The Limits of Genre Danielle Collobert S Poetics of TransgressionSteffi DanielleNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of The Holocaust Short Story 1St Edition Mary Catherine Mueller Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of The Holocaust Short Story 1St Edition Mary Catherine Mueller Online PDF All Chapterperbiljheysi100% (5)

- Discurs Bloom EngDocument8 pagesDiscurs Bloom Engmadwani1No ratings yet

- Hanukai Columbia 0054D 12149Document184 pagesHanukai Columbia 0054D 12149DildoraNo ratings yet

- The Time Being On Woolf and Boredom: Sara CrangleDocument24 pagesThe Time Being On Woolf and Boredom: Sara CrangleName123No ratings yet

- This Time RoundDocument22 pagesThis Time Roundmausa2014No ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu and At the Mountains of Madness: Two Tales of the MythosFrom EverandThe Call of Cthulhu and At the Mountains of Madness: Two Tales of the MythosRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- FRIEDMAN, M. Samuel Beckett and The Nouveau Roman PDFDocument16 pagesFRIEDMAN, M. Samuel Beckett and The Nouveau Roman PDFyagogierlini2167No ratings yet

- Bataille's Tomb - A Halloween StoryDocument31 pagesBataille's Tomb - A Halloween StoryFrancesco AgnelliniNo ratings yet

- 263-285. 9. For An End To Discursive CrisisDocument24 pages263-285. 9. For An End To Discursive CrisisBaha ZaferNo ratings yet

- Pornografia: by Witold GombrowiczDocument95 pagesPornografia: by Witold GombrowiczM_RoubignolesNo ratings yet

- Kristeva - Is There A Feminine GeniusDocument13 pagesKristeva - Is There A Feminine GeniusLady MosadNo ratings yet

- Document For Review RevisedDocument19 pagesDocument For Review RevisedFrancis Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Dying Becomes Her Posthumanism in SophocDocument21 pagesDying Becomes Her Posthumanism in SophocRicardo Lessa FilhoNo ratings yet

- Stojko - The Monster in Colonial Gothic - Seminar Paper2Document14 pagesStojko - The Monster in Colonial Gothic - Seminar Paper2stojkaaaNo ratings yet

- Modern Movements in European Philosophy Final ProjectDocument12 pagesModern Movements in European Philosophy Final ProjectAmna AhadNo ratings yet

- The Lives of Hart CraneDocument16 pagesThe Lives of Hart CraneJosé Luis AstudilloNo ratings yet

- The Triangle of Virtue Fasting Taqwa and The Quran.Document12 pagesThe Triangle of Virtue Fasting Taqwa and The Quran.Mikel AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Poem The Living Photograph: Hots Questions + AnswersDocument4 pagesPoem The Living Photograph: Hots Questions + AnswersRichard Vun100% (1)

- Shrimad Rajchandra and Gandhiji PDFDocument214 pagesShrimad Rajchandra and Gandhiji PDFKartik MehtaNo ratings yet

- Homer, Odyssey Book 1Document9 pagesHomer, Odyssey Book 1Jorge Luis BorgesNo ratings yet

- Genesis 6 GiantsDocument2 pagesGenesis 6 GiantsHaSophim33% (3)

- Salih Selimovic - Muslimani U Bosni Su Vecinom SrbiDocument6 pagesSalih Selimovic - Muslimani U Bosni Su Vecinom SrbiJelenaJovanović0% (1)

- Satan, Demons, and The Noble Dark Arts of The Order of Nine AnglesDocument83 pagesSatan, Demons, and The Noble Dark Arts of The Order of Nine AnglesDark Japer100% (3)

- Line by Line Analysis of The Poem " in Warsaw" by Czselaw MiloszDocument6 pagesLine by Line Analysis of The Poem " in Warsaw" by Czselaw MiloszSaibal DebbarmaNo ratings yet

- Hymn Tune PDFDocument1 pageHymn Tune PDFKody PisneyNo ratings yet

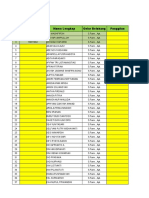

- Data SerkomDocument15 pagesData SerkomRizki YulisetiawanNo ratings yet

- The Fable of The Spider and The Bee and Swifts Poetics of InspDocument9 pagesThe Fable of The Spider and The Bee and Swifts Poetics of InspAngela KhanNo ratings yet

- ENGL1007 Essay QuestionsDocument4 pagesENGL1007 Essay QuestionsKatherine WangNo ratings yet

- A Trip To The Sand Castle and MoreDocument47 pagesA Trip To The Sand Castle and MoreDougNewNo ratings yet

- Aramaic Enoch Scroll: It Is Wikipedia's Birthday!Document1 pageAramaic Enoch Scroll: It Is Wikipedia's Birthday!Pietro GiocoliNo ratings yet

- Speaking The SilenceDocument11 pagesSpeaking The SilenceMaria Alejandra GonzalezNo ratings yet

- GlossaryDocument256 pagesGlossaryJavier Artal ArtigasNo ratings yet

- Interview FinalDocument4 pagesInterview FinaltwinkletwinkletwinkNo ratings yet

- Hippolytus, MacMahon, Salmond. The Refutation of All Heresies. 1868. Volume 2.Document312 pagesHippolytus, MacMahon, Salmond. The Refutation of All Heresies. 1868. Volume 2.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- PALMQUIST - Tree.35. The Following Books Are CitedDocument5 pagesPALMQUIST - Tree.35. The Following Books Are Citededson1d.1gilNo ratings yet

- Superiority : Othello Through A MarxistDocument7 pagesSuperiority : Othello Through A Marxistash-a-lilly3613No ratings yet

- English BS PDFDocument150 pagesEnglish BS PDFNaveed ShahNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Trojan War: Lesson 6Document2 pagesSummary of The Trojan War: Lesson 6Ali BaigNo ratings yet

- Synfocity 395Document4 pagesSynfocity 395Mizoram Presbyterian Church SynodNo ratings yet

- Ayat e Shifa Arabic UrduDocument22 pagesAyat e Shifa Arabic UrduMasood Akbar100% (2)

- Flatland 2Document2 pagesFlatland 2api-257891091No ratings yet

- OED - Reading and Writing SkillsDocument27 pagesOED - Reading and Writing SkillsLouiz SamsonNo ratings yet

- Lakshman Divya 3Document15 pagesLakshman Divya 3Dr-Amarnath JeyakodiNo ratings yet

- A General WritingDocument40 pagesA General WritingGaneshrudNo ratings yet

Corina. Naomi SCHOR. THIRD WOMAN

Corina. Naomi SCHOR. THIRD WOMAN

Uploaded by

r.emilianomorenoterrazasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Corina. Naomi SCHOR. THIRD WOMAN

Corina. Naomi SCHOR. THIRD WOMAN

Uploaded by

r.emilianomorenoterrazasCopyright:

Available Formats

Corinne: The Third Woman

Author(s): Naomi Schor

Source: L'Esprit Créateur , Fall 1994, Vol. 34, No. 3, Le Centre Absent (passage,

métamorphose): En Hommage à Micheline Tison-Braun (Fall 1994), pp. 99-106

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26287597

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to L'Esprit Créateur

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Corinne: The Third Woman

Naomi Schor

On eût dit que dans ces lieux, comme dans la tragédie de Hamlet, les ombres erraient autour

du palais où se donnaient les festins.

Madame de Staël, Corinne ou l'Italie

IN aMARCH,

paper on death in Staël's

1992, while Corinne that I proposed

on leave to give

in Paris, at the

I prepared a synopsis of

annual fall meeting of Nineteenth-Century French Studies. A month

later I was being operated on at the Hôpital Saint-Antoine for a life

threatening liver failure.

Little did I realize at the time that I was entering a new stage in my

life, a stage of serial illnesses from which I have yet to emerge. Conse

quently, what I viewed with apt modesty as a "small" paper has come to

seem to me despite its restricted dimensions a strangely prophetic project

insistently calling into question the very relationship of the mind and

body I had spent a lifetime repressing. Did I feel the need to write about

death because I was in fact and unbeknownst to me silently dying? And

when did that dying begin, when I sat at my word processor before my

illness declared itself in full-blown visible, visualizable, and quantifiable

symptoms but heralded its crisis in so called "non-specific" symptoms:

extreme fatigue, depression, loss of inspiration? Shortly before his un

expected and untimely death my father produced two atypically morbid

works: a large self portrait in livid hues of muddy greens and ghoulish

blues—the face of a drowned man—and an oversize brass mask where in

one empty socket one could see a doll-like male figure dangling from a

spring—the effigy of a man who has hung himself. Did life imitate art

when my father's heart failed him or did some Lethe-like fluid guide his

hand as he created those works?

Like so many other projects I was engaged in at the time, the paper

on Corinne was a casualty of my illness and recovery. The celebration of

the life work of Mme Tison-Braun, the beloved teacher who first awak

ened and recognized in me an interest in French literature, is the happy

occasion of my at last but with no lesser sense of urgency writing the

paper I had outlined when I still counted myself among the healthy.

Vol. XXXIV, No. 3 99

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

I want in what follows to make and, hopefully, substantiate an outland

ish claim: because of the disparity between the chronology of events and

the narrative organization of the material, when Corinne first appears i

the novel that bears her name, she is already dead, a victim of patriarchy,

a gendered ghost, the ghost of gender. In other words, Corinne is neither,

as the narrator suggests, a mere retelling of the archetypal story of

Sheherazade, who enlists narrative in the deferral of death,1 nor, by th

same token, a reworking of what Peter Brooks has called Freud's master

plot, the dawdlings and detours of the death-driven Beyond the Pleasur

Principle. Death in Corinne is not the telos to be avoided, but the disaster

which has already occurred, which sets the narrative in motion and

brings it finally to its foreordained conclusion, the physical enactment of

a symbolic death.

Much has been written about women and death in art and fiction,

and a consensus has emerged regarding the proliferation of dead or dying

female figures in the European art produced during a time period extend

ing from the mid-eighteenth to the late nineteenth century. Following

Michel Foucault's periodization, which dovetails with that of Philippe

Ariès, Elizabeth Bronfen in her ambitious Lacanian exercise in "thanato

poetics," Over Her Dead Body, sees the end of the eighteenth century as

marked by an epistemic shift in the function and representation of death.

What characterizes this new understanding of death is its ambivalence:

viewed as a means of attaining scientific truth, the corpse is simultane

ously seen as a source of pollution which must be distanced from the city;

viewed as a means of individuation, death constantly threatens the living

with the return of the repressed Other:

By the nineteenth century, "love" and "death" were culturally constructed as the two

realms where savage nature could break into "man" 's city, at the same historical momen

that society believed that its achievements in technology and rationalism had served to colo

nise nature completely. Since it combines these two disruptive elements, the dead body of a

woman served as a particularly effective figure for this triumph over "violent nature" and

its failure to expulse the Other completely; a superlative figure for the inevitable return o

the repressed.2

There are in fact (at least) two epistemic shifts which coincide at the turn

of the eighteenth century: on the one hand death is reconfigured, secu

larized, individualized, on the other, femininity is invented through th

100 Fall 1994

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCHOR

convergence of a set of emerging disciplinary discourses and in response

to increasingly urgent political pressures (OHDB 78). Hence the fem

inization of the corpse, the killing of women form a nexus which

becomes by mid-century a stereotype: "her dead body." It is this coming

together that distinguishes post-revolutionary literary and pictorial rep

resentations of dead women from those that immediately precede that

historical break in France, for of course representations of women as

dead or death itself goes back as far as classical mythology; as Madelyn

Gutwirth observes:

A fascination with female frailty certainly recurs in Western art with some reliability over

the centuries, remaining one of the stock of topoi available to it. But no glut of such fore

doomed figures exists in modern times before the waning of the Age of Enlightenment and

in the century that copes with this heritage.3

The crucial factor is that what is at stake in both Bronfen's and Gut

wirth's studies is the triangle constituted by death, femininity, and a male

author or artist. Or, to paraphrase Bronfen: Her body/His text. Gut

wirth mentions only one woman in her article, Mme Riccoboni, and not

in her capacity as a writer, rather her role as a critic of Laclos's Liaisons

Dangereuses. Bronfen does include two novels by women in her book,

Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre and Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, but she

reserves her discussion of women writers and artists and death for a final

chapter entitled, "From muse to creatrix—Snow White unbound." This

transmutation is emphatically a twentieth-century phenomenon. What

tends then to get lost in these accounts is the specificity of representations

of dead women in pre-twentieth-century works by women artists and

authors. Even when they are cited, gender difference is elided.

It may well be that in the historical context in which Corinne ap

peared it was impossible for a woman writer, however rebellious, to

break with the dominant models of representation. And yet Corinne is in

so many other respects an iconoclastic novel that it strains credulity that

Corinne's dead body is indistinguishable from that of Ellénore, Benja

min Constant's counter example in Adolphe, and that what distinguishes

them is unrelated to the sexual divide that separates their authors. It is

the same difference as that between suicide and matricide.

From the very first page the prominence of death in this deeply

melancholic early romantic novel is made clear, but it is not, as one

might expect, the heroine's, or any other woman's for that matter, but

the hero's father's. When we first encounter Oswald Lord Nelvil he is on

Vol. XXXIV, No. 3 10i

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

a journey to Italy for medical reasons: "La plus intime de toutes les

douleurs, la perte d'un père, était la cause de sa maladie" ("The most

personal of all griefs, the loss of a father, had provoked his illness" (C

28/5). Implicit in this phrase is a maxim which goes something like: his

father's death is man's greatest sorrow. When, as is the case for Oswald,

that irreparable loss is overlayed with guilt, then the disease is as we in

time discover incurable. Afflicted with a bad case of what Margaret

Waller has wittily called "the male malady"4 (a.k.a. the mâle de siècle),

Oswald is a severely depressed Oedipus. It is in this state that he encoun

ters Corinne, who is at the very pinnacle of her success. I am referring, of

course, to the celebrated scene of her crowning at the Capitol. From that

moment on Corinne takes it upon herself to cure the unhappy Oswald.

This is tourism as therapy: she will cure him by making him see Italy and

its beauties, for like Oedipus at Colonnus Oswald in Italy is blind, sight

less: "Oswald parcourut la Marche d'Ancone et l'Etat ecclésiastique

jusqu'à Rome sans rien observer" ("Oswald crossed the Marches and the

Papal States as far as Rome without noticing anything" [C 46/77]); "il

ne remarqua point les lieux antiques et célèbres à travers lesquels passait

le char de Corinne" ("he took no notice whatever of the ancient places

traversed by Corinne's chariot" [C 53/22]). The cure is homeopathic, in

that it fights grief with grief; the burden of Oswald's mourning of his

dead father is offset by a visit to the cemetery outside the city gates where

Corinne guides Oswald to the funerary monument dedicated by a Roman

citizen to the memory of his dead daughter, Cecilia Métalla.5

But above all to see Italy is to see Corinne; the cure for Oswald's

undone grief work is gazing at Corinne. Gazing at Corinne is a moral

imperative for Oswald, for as the prince Castel-Forte enjoins him:

"regardez Corinne" ("Behold Corinne" [C 58/25]).

What does it mean to "behold" Corinne? Corinne, when Oswald

first sees her, is the picture of health; at the height of her powers she is

the most animated of heroines. It is this animation that I want to hold up

to scrutiny, for it is illusory; the solar Corinne conceals a cold lunar land

scape. She radiates a life force that is the after-glow of a star long dead.

In this strange temporality, the reading of the novel that would have

Corinne waste away as a result of Oswald's craven abandonment is a par

tial reading that too readily accepts conventional causality as its organiz

ing principle, that is too quick to charge the male protagonist—absent a

male author—with murder. It forgets one of the crucial lessons of

Lacan's mirror stage, the impossibility of representing the body in pieces

102 Fall 1994

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCHOR

except from the perspective of the body as whole. The disjointed body of

the infant can only be reconstructed from the vantage point of an

imaginary identity. In the words of Jane Gallop: "The image of the body

in bits and pieces is fabricated retroactively from the mirror stage. It is

only the anticipated 'orthopedic' form of totality that can define—retro

actively—the body as insufficient."6 Corinne must reach the pinnacle of

success for her underlying inexistence to become visible. Stardom—and

Corinne, the performance artist, is nothing if not a star—is ghostly, a

state of haunting.

Let us recall that when Corinne at last provides the key to the enigma

of her identity, her missing patronym, she makes the following crucial

avowal: after her father Lord Edgermond's death in England, she is

driven into exile by her step-mother, who makes a diabolical bargain

with her:

. . . si vous prenez un parti qui vous déshonore dans l'opinion, vous devez à votre famille de

changer de nom et de vous faire passer pour morte.

[". . . should you decide on a course of action that will dishonor you in public opinion, you

owe it to your family to change your name and pass for dead." (C 382/267)]

Oui, sans doute, m'écriais-je, passons pour morte dans ces lieux où mon existence n'est

qu'un sommeil agité. Je revivrai avec la nature, avec le soleil, avec les beaux-arts, et les

froides lettres que composent mon nom, inscrites sur un vain tombeau, tiendront, aussi

bien que moi, ma place dans ce séjour sans vie.

["Yes! Why not?" 1 exclaimed. "In this place where my life is no more than a troubled

sleep, let them think me dead. With nature, with the sun, with the arts, I shall come alive

again; and in this lifeless world, the cold letters of my name engraved on an empty tomb

will surely take my place as well as ever I could." (C 383-84/26«?)]

Though by virtue of its history Italy is the land of ruins and crumbling

tombstones, England by virtue of its rigid ideology of separate spheres is

at least for women the "land of the living dead" (MM 76-79).7 English

society is a cemetery where a brilliant public woman like Corinne can

only be buried alive, racked by nightmares—"perchance to dream." To

leave England is to rise Lazarus-like from the dead, yet at the same time

to leave England is to leave behind more than the lifeless letters that

make up one's patronym, rather one's mortal envelope; to return to Italy

is to (re)enter the land of the living but to do so in spectral form.

Si la vie est offerte aux morts dans les tombeaux, ils ne soulèveraient pas la pierre qui les

VOL. XXXIV, No. 3 103

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

couvre avec plus d'impatience que je n'en éprouvais pour écarter de moi tous mes linceuls

et reprendre possession de mon imagination, de mon génie, de la nature.

[Were life offered to the dead in their graves, they would not lift off their tombstones with

greater impatience than I felt to cast off my shrouds, and repossess nature, my imagination

and my genius. (C 385/268)]

Paradoxically, however, Corinne can only arise from the dead by faking

her real death, staging her disappearance. Well before Oswald journey

to Italy to restore his health, Corinne is rumored to have done the same

so that Oswald on page one repeats Corinne's earlier gesture, for in wha

Derrida calls the "logic of spectrality"8 there is no separating the first

time from its repetition.

Ma belle-mère me manda qu'elle avait répandu le bruit que les médecins m'avaient ordonn

le voyage du midi pour rétablir ma santé, et que j'étais morte dans la traversée.

[My stepmother gave me to understand that she had spread word of my death on a trip to

the south prescribed by the doctors for my health. (C 3867.269)]

Every crossing in Corinne evokes the fatal passage of the Styx: thus,

when at the end of the novel Oswald returns to Italy with his wife and

child, the river Taro is transformed into a dangerous torrent:

le brouillard était tel que le fleuve se confondait avec l'horizon, et ce spectacle rappelait

bien plutôt les descriptions poétiques des rives du Styx, que ces eaux bienfaisantes qu

doivent charmer les regards des habitants brûlés par les rayons du soleil.

[The fog was so thick that the river merged with the horizon, and the spectacle recalled th

poetic descriptions of the banks of the river Styx, rather than the benevolent waters meant

to charm the eyes of a population burnt by the rays of the sun. (C 5581397)]

The extraordinary Corinne that Oswald sees is then posthumous, not

literally a dead female body, but a dead female soul: "on dirait que je

suis une ombre qui veut encore rester sur la terre, quand les rayons du

jour, quand l'approche des vivants, la forcent à disparaître" ("It is as if I

were a shade still wanting to remain on earth when the light of day, th

approach of the living, compel it to disappear" [C 522/371]), she writes

when she is wasting away. She does not become a ghost because she was

abandoned, rather, she is abandoned precisely because of her ghostliness

From the moment of Corinne's publication readers were stumped by

the pairing of Oswald and Corinne: what do these two characters have in

common? what does Corinne, the exceptional woman, see in Oswald, the

104 Fall 1994

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SCHOR

conventional albeit new "sensitive" man? What prevents Oswald from

choosing the profound Corinne over her superficial half sister Lucille?

There is, of course, no single answer to this question, and over the years

the answers have ranged from the humorous (Eliot's in The Mill on the

Floss) to the scathing: the readings of contemporary feminists who view

Corinne as a paradigm of the exceptional woman and the post-revolu

tionary killing into allegory of woman. Curiously, the psychoanalytic

dimension has been neglected, yet it sheds light on this conundrum:

Oswald abandons Corinne not only because of his father's law, not only

because he is culturally unsuited to love a woman who does not adhere to

the ideal of domesticity, but because Corinne represents death in the

manner of Freud's third woman in his neat little essay of 1913, "The

Theme of the Three Caskets." Unlike Freud's archetypal male, however,

who fools destiny by selecting the inevitable, Oswald, who otherwise is

always placing himself in harm's way, flees death in the shape of a come

ly woman, "the fairest, best, most desirable and the most lovable of

women."9 Because Oswald is a narcissist he rejects the Other and the

Death-Goddess is the ultimate Other. The third woman is the woman

who subverts the function assigned Woman in the male imaginary, that

of guarantor of man's exclusive subjectivity and sense of phallic invul

nerability. Is it any wonder then that narcissistic men, whose very self is

threatened by female alterity and the death it signifies for their majestic

Ego, chose unthreatening love objects that enhance their sense of

omnipotence and immortality?

And what of the third woman? Can the third woman die? Yes: there

is a double dying in Corinne. But in Corinne the Goddess of Death is

dumb no more, Atropos speaks, writes, and what is more leaves a legacy.

Not only does she stage her death, but she stages her swan song. More

important, by the means of feminist pedagogy, the transmission of her

wisdom to Lucille and Lucille and Oswald's daughter Juliette, she lives

on. The specter of the exceptional woman haunts the nineteenth century.

Duke University

Notes

1. Madame de Staël, Corinne ou l'Italie (Paris: Folio, 1985), 133; Corinne, or Italy, trans.

Avriel H. Goldberger (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1987), 81. Subsequent page ref

erences to these editions will be given within the text under the abbreviation C, with the

English page numbers in italics.

Vol. XXXIV, No. 3 105

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

Elizabeth Bronfen, Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity, and the Aesthetic (New

York: Routledge, 1992), 86; hereafter abbreviated as (OHDB).

Madelyn Gutwirth, "The Engulfed Beloved: Representations of Dead and Dying

Women in the Art and Literature of the Revolutionary Era," in Sara E. Melzer and

Leslie W. Rabine, eds., Rebel Daughters: Women and the French Revolution (New

York: Oxford UP, 1992), 198.

Margaret Waller, The Male Malady: Fictions of Impotence in the French Romantic

Novel (New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1994). Hereafter (MM).

This detail is glossed by Nancy K. Miller, Subject to Change: Reading Feminist Writing

(New York: Columbia UP, 1988), 172-73.

Jane Gallop, Reading Lacan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985), 86.

Cf. Jean Starobinski's congruent description of Corinne as "une morte-vivante" ("a

living-dead woman") in his article, "Suicide et mélancolie chez Mme de Staël," in

Madame de Staël et l'Europe, Colloque de Coppet (Paris: Klincksieck, 1970), 246.

Starobinski's concern is the psychology of Staël and her heroines. The (virtual) aban

doned woman is kept alive through the artificial means of a love whose withdrawal

determines an "ontological catastrophe" (247).

Jacques Derrida, Spectres de Marx (Paris: Galilée, 1993), 24.

Sigmund Freud, "The Theme of the Three Caskets," Character and Culture (New

York: Collier, 1963), 76.

Fall 1994

106

This content downloaded from

132.248.9.41 on Wed, 11 May 2022 19:45:45 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- TwoShakesComedies TMDocument16 pagesTwoShakesComedies TMareianoar100% (1)

- Bradmehldau Linernotes EcDocument5 pagesBradmehldau Linernotes EcBia CyrinoNo ratings yet

- The Perpetual Orgy: Flaubert and Madame BovaryFrom EverandThe Perpetual Orgy: Flaubert and Madame BovaryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Flannery O'Connor and The Violence of GraceDocument17 pagesFlannery O'Connor and The Violence of Graceisabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- Death Theme in LiteratureDocument3 pagesDeath Theme in Literaturemterrano0% (1)

- JAMESON, Walter Benjamin, or NostalgiaDocument18 pagesJAMESON, Walter Benjamin, or NostalgiaDaniel LesmesNo ratings yet

- Odyseuss Travels Graphic OrganizerDocument2 pagesOdyseuss Travels Graphic OrganizerFire1086100% (2)

- Artaud's Hélioglobale PDFDocument24 pagesArtaud's Hélioglobale PDFvolentriangleNo ratings yet

- Confession and Double ThoughtsDocument41 pagesConfession and Double ThoughtsJoe EscarchaNo ratings yet

- Blanchot Death of VirgilDocument16 pagesBlanchot Death of VirgilfrederickNo ratings yet

- J.M. COETZEE - On The Edge of RevelationDocument6 pagesJ.M. COETZEE - On The Edge of RevelationMarius DomnicaNo ratings yet

- Steel1981.plague Writing From Boccaccio To CamusDocument23 pagesSteel1981.plague Writing From Boccaccio To Camusje8aNo ratings yet

- "Oh, Do Not Ask, What Is It?'" in Eliot's The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock' and Gerontion'Document6 pages"Oh, Do Not Ask, What Is It?'" in Eliot's The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock' and Gerontion'Ipshita NathNo ratings yet

- A Simonidean Tale Commemorationand Coming To Terms With The Past Michel Tournier S Le Roi Des AulnesDocument23 pagesA Simonidean Tale Commemorationand Coming To Terms With The Past Michel Tournier S Le Roi Des AulnesGrace MalcomsonNo ratings yet

- Conditioning Adorno: After Auschwitz' NowDocument8 pagesConditioning Adorno: After Auschwitz' NowlaiosNo ratings yet

- 2008 MartinezDocument21 pages2008 MartinezDiego Pérez HernándezNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press, Royal Institute of Philosophy PhilosophyDocument14 pagesCambridge University Press, Royal Institute of Philosophy PhilosophyNegru CorneliuNo ratings yet

- Alkalay Gut PJ HarveyDocument30 pagesAlkalay Gut PJ HarveytenbrinkenNo ratings yet

- A Contradiction in Essence - Eroticism and The Creation of The SDocument36 pagesA Contradiction in Essence - Eroticism and The Creation of The SRonildo SansaoNo ratings yet

- Tenzin Dolma Lama 120351101Document7 pagesTenzin Dolma Lama 120351101Tenzin DolmaNo ratings yet

- Barthes, Roland - "The Death of The Author"Document8 pagesBarthes, Roland - "The Death of The Author"Anonymous aPGQwr5xNo ratings yet

- Heffernan Post Apocalyptic PaperDocument9 pagesHeffernan Post Apocalyptic PapersarajamalsweetNo ratings yet

- Tears of Eros 0872862224 9780872862227 - CompressDocument228 pagesTears of Eros 0872862224 9780872862227 - Compress성우진No ratings yet

- THE EVIL OF MODERNITY: JOSEPH CONRAD'S HEART OF DARKNESS AND FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA'S APOCALYPSE NOW Michel MaslowskiDocument17 pagesTHE EVIL OF MODERNITY: JOSEPH CONRAD'S HEART OF DARKNESS AND FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA'S APOCALYPSE NOW Michel MaslowskiAeosphorusNo ratings yet

- W. Land3Document16 pagesW. Land3Maroua TouilNo ratings yet

- PDF The End of Literature Hegel and The Contemporary Novel Francesco Campana Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF The End of Literature Hegel and The Contemporary Novel Francesco Campana Ebook Full Chapterwilliam.caldwell528100% (1)

- Studien Zur Deutschen Literatur: Band 90Document201 pagesStudien Zur Deutschen Literatur: Band 90EmilijaNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument39 pagesLiterature ReviewIbrahim Afganzai0% (1)

- Breathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaFrom EverandBreathless: Sound Recording, Disembodiment, and the Transformation of Lyrical NostalgiaNo ratings yet

- Orwell's CommediaDocument29 pagesOrwell's CommediacoilNo ratings yet

- Clark-Idealism and Dystopia en Tlon Uqbar Orbis TertiusDocument6 pagesClark-Idealism and Dystopia en Tlon Uqbar Orbis TertiusAnonymous dmAFqFAENo ratings yet

- Yale University Press Yale French Studies: This Content Downloaded From 128.84.126.163 On Fri, 25 Oct 2019 02:22:06 UTCDocument16 pagesYale University Press Yale French Studies: This Content Downloaded From 128.84.126.163 On Fri, 25 Oct 2019 02:22:06 UTCEfe RosarioNo ratings yet

- Myth and MannDocument16 pagesMyth and MannmporakishviliNo ratings yet

- 10 Titeeksha PathaniaDocument7 pages10 Titeeksha Pathaniabipolarbear872No ratings yet

- The Swerve - How The World Became Modern - by Stephen Greenblatt - Book Review - NYTimesDocument5 pagesThe Swerve - How The World Became Modern - by Stephen Greenblatt - Book Review - NYTimesAntónio Teixeira50% (2)

- Alfred de Vigny's - Eloa - A Modern Myth - Author(s) - Lucretia S. GruberDocument10 pagesAlfred de Vigny's - Eloa - A Modern Myth - Author(s) - Lucretia S. GruberCassio CarvalheiroNo ratings yet

- 03 MathewsDocument26 pages03 MathewsNatalia LauraNo ratings yet

- On Nature and the Goddess in Romantic and Post-Romantic LiteratureFrom EverandOn Nature and the Goddess in Romantic and Post-Romantic LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Writing at The Limits of Genre Danielle Collobert S Poetics of TransgressionDocument12 pagesWriting at The Limits of Genre Danielle Collobert S Poetics of TransgressionSteffi DanielleNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of The Holocaust Short Story 1St Edition Mary Catherine Mueller Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of The Holocaust Short Story 1St Edition Mary Catherine Mueller Online PDF All Chapterperbiljheysi100% (5)

- Discurs Bloom EngDocument8 pagesDiscurs Bloom Engmadwani1No ratings yet

- Hanukai Columbia 0054D 12149Document184 pagesHanukai Columbia 0054D 12149DildoraNo ratings yet

- The Time Being On Woolf and Boredom: Sara CrangleDocument24 pagesThe Time Being On Woolf and Boredom: Sara CrangleName123No ratings yet

- This Time RoundDocument22 pagesThis Time Roundmausa2014No ratings yet

- The Call of Cthulhu and At the Mountains of Madness: Two Tales of the MythosFrom EverandThe Call of Cthulhu and At the Mountains of Madness: Two Tales of the MythosRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- FRIEDMAN, M. Samuel Beckett and The Nouveau Roman PDFDocument16 pagesFRIEDMAN, M. Samuel Beckett and The Nouveau Roman PDFyagogierlini2167No ratings yet

- Bataille's Tomb - A Halloween StoryDocument31 pagesBataille's Tomb - A Halloween StoryFrancesco AgnelliniNo ratings yet

- 263-285. 9. For An End To Discursive CrisisDocument24 pages263-285. 9. For An End To Discursive CrisisBaha ZaferNo ratings yet

- Pornografia: by Witold GombrowiczDocument95 pagesPornografia: by Witold GombrowiczM_RoubignolesNo ratings yet

- Kristeva - Is There A Feminine GeniusDocument13 pagesKristeva - Is There A Feminine GeniusLady MosadNo ratings yet

- Document For Review RevisedDocument19 pagesDocument For Review RevisedFrancis Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Dying Becomes Her Posthumanism in SophocDocument21 pagesDying Becomes Her Posthumanism in SophocRicardo Lessa FilhoNo ratings yet

- Stojko - The Monster in Colonial Gothic - Seminar Paper2Document14 pagesStojko - The Monster in Colonial Gothic - Seminar Paper2stojkaaaNo ratings yet

- Modern Movements in European Philosophy Final ProjectDocument12 pagesModern Movements in European Philosophy Final ProjectAmna AhadNo ratings yet

- The Lives of Hart CraneDocument16 pagesThe Lives of Hart CraneJosé Luis AstudilloNo ratings yet

- The Triangle of Virtue Fasting Taqwa and The Quran.Document12 pagesThe Triangle of Virtue Fasting Taqwa and The Quran.Mikel AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Poem The Living Photograph: Hots Questions + AnswersDocument4 pagesPoem The Living Photograph: Hots Questions + AnswersRichard Vun100% (1)

- Shrimad Rajchandra and Gandhiji PDFDocument214 pagesShrimad Rajchandra and Gandhiji PDFKartik MehtaNo ratings yet

- Homer, Odyssey Book 1Document9 pagesHomer, Odyssey Book 1Jorge Luis BorgesNo ratings yet

- Genesis 6 GiantsDocument2 pagesGenesis 6 GiantsHaSophim33% (3)

- Salih Selimovic - Muslimani U Bosni Su Vecinom SrbiDocument6 pagesSalih Selimovic - Muslimani U Bosni Su Vecinom SrbiJelenaJovanović0% (1)

- Satan, Demons, and The Noble Dark Arts of The Order of Nine AnglesDocument83 pagesSatan, Demons, and The Noble Dark Arts of The Order of Nine AnglesDark Japer100% (3)

- Line by Line Analysis of The Poem " in Warsaw" by Czselaw MiloszDocument6 pagesLine by Line Analysis of The Poem " in Warsaw" by Czselaw MiloszSaibal DebbarmaNo ratings yet

- Hymn Tune PDFDocument1 pageHymn Tune PDFKody PisneyNo ratings yet

- Data SerkomDocument15 pagesData SerkomRizki YulisetiawanNo ratings yet

- The Fable of The Spider and The Bee and Swifts Poetics of InspDocument9 pagesThe Fable of The Spider and The Bee and Swifts Poetics of InspAngela KhanNo ratings yet

- ENGL1007 Essay QuestionsDocument4 pagesENGL1007 Essay QuestionsKatherine WangNo ratings yet

- A Trip To The Sand Castle and MoreDocument47 pagesA Trip To The Sand Castle and MoreDougNewNo ratings yet

- Aramaic Enoch Scroll: It Is Wikipedia's Birthday!Document1 pageAramaic Enoch Scroll: It Is Wikipedia's Birthday!Pietro GiocoliNo ratings yet

- Speaking The SilenceDocument11 pagesSpeaking The SilenceMaria Alejandra GonzalezNo ratings yet

- GlossaryDocument256 pagesGlossaryJavier Artal ArtigasNo ratings yet

- Interview FinalDocument4 pagesInterview FinaltwinkletwinkletwinkNo ratings yet

- Hippolytus, MacMahon, Salmond. The Refutation of All Heresies. 1868. Volume 2.Document312 pagesHippolytus, MacMahon, Salmond. The Refutation of All Heresies. 1868. Volume 2.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- PALMQUIST - Tree.35. The Following Books Are CitedDocument5 pagesPALMQUIST - Tree.35. The Following Books Are Citededson1d.1gilNo ratings yet

- Superiority : Othello Through A MarxistDocument7 pagesSuperiority : Othello Through A Marxistash-a-lilly3613No ratings yet

- English BS PDFDocument150 pagesEnglish BS PDFNaveed ShahNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Trojan War: Lesson 6Document2 pagesSummary of The Trojan War: Lesson 6Ali BaigNo ratings yet

- Synfocity 395Document4 pagesSynfocity 395Mizoram Presbyterian Church SynodNo ratings yet

- Ayat e Shifa Arabic UrduDocument22 pagesAyat e Shifa Arabic UrduMasood Akbar100% (2)

- Flatland 2Document2 pagesFlatland 2api-257891091No ratings yet

- OED - Reading and Writing SkillsDocument27 pagesOED - Reading and Writing SkillsLouiz SamsonNo ratings yet

- Lakshman Divya 3Document15 pagesLakshman Divya 3Dr-Amarnath JeyakodiNo ratings yet

- A General WritingDocument40 pagesA General WritingGaneshrudNo ratings yet