Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guindon, M. H. (2002) - Toward Accountability in The Use of The Self Esteem Construct. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80 (2), 204-214.

Guindon, M. H. (2002) - Toward Accountability in The Use of The Self Esteem Construct. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80 (2), 204-214.

Uploaded by

200810469Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guindon, M. H. (2002) - Toward Accountability in The Use of The Self Esteem Construct. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80 (2), 204-214.

Guindon, M. H. (2002) - Toward Accountability in The Use of The Self Esteem Construct. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80 (2), 204-214.

Uploaded by

200810469Copyright:

Available Formats

ASSESSMENT & DIAGNOSIS

Toward Accountability in the Use of the Self-Esteem

Construct

Mary H. Guindon

Self-esteem is a common target of intervention, and the proliferation of research on self-esteem attests to the widely held belief

of its significance as a personality variable. Despite its popularity, there is limited consistency in the use of its definition, and little

evidence suggests that counselors routinely assess levels of self-esteem. This indicates a lack of attention to accountability in

the quality of counselor services. This article provides a step toward accountability by presenting a review of the evolution of self-

esteem as a construct, offering definitions grounded in the professional literature, and discussing a compendium of self-esteem

assessments. Working toward consistency and responsibility in defining and assessing self-esteem can positively influence

effective self-esteem interventions.

S

elf-esteem is investigated and researched by be- in the title, 1,313 (37.98%) were written in the 8 years

havioral scientists and practitioners of various de- from 1992 through March 2000.

scriptions and disciplines. As a focus of research Clearly self-esteem publications are common, yet few

examining personality (Demo, 1985), it continues seem to be focused on its definition. Of the thousands of

to be the subject of numerous research studies and entries listed in ERIC on some aspect of self-esteem, only a

intervention strategy articles. Counseling interventions targeted few are listed as targeting its definition. Furthermore, al-

at affecting self-esteem levels and facilitating its optimal though there are ample assessment instruments measuring

development are common despite the fact that (a) many writ- self-esteem for research purposes, little evidence suggests

ers have criticized its meaning and usage (L. Kaplan,1995; Lerner, that counselors actually use these instruments for assess-

1985; London, 1997; Wylie, 1974), (b) self-esteem interven- ment purposes, even though level of self-esteem is often an

tion results are variable (Bednar & Peterson, 1995; L. Kaplan, issue for clients. Although studies examining assessment prac-

1995; Mruk, 1999; Smelser, 1989; Wylie, 1974), and (c) its tices of counselors are limited (Giordano, Schwiebert, &

conceptualization and operationalization have not been con- Brotherton, 1997), counselors typically use only a small

sistent (Demo, 1985; Wylie, 1974). Moreover, the self-esteem number of instruments of any kind in their work (Bubenzer,

construct has become highly popularized, leading to its per- Zimpfer, & Mahrle, 1990) and studies inquiring about assess-

ception as an “over-inflated panacea” (Street & Isaacs, 1998). ment practices have not included self-esteem instruments.

A search of professional literature substantiates the pro- The ability to accurately assess and evaluate levels of func-

liferation of self-esteem as an area of inquiry. An ERIC search tioning is an established requirement for professional coun-

from 1982 to March 2000 produced 4,959 entries on the selors (American Counseling Association, 1995). Counselors

subject of self-esteem, and a PsycINFO search generated can be expected to use appropriate methods of assessment so

7,719 journal articles from 1984 to June 2000. As an area of that their decisions are sound and interventions are more

research, the phenomenon seems to be gaining in popular- likely to fit the needs of their clients (Ridley, Li, & Hill,

ity. An ERIC search showed that the term self-esteem ap- 1998). Clearly, diagnosis is central to professional communi-

peared in the title in 444 articles in the 10-year period, cation and treatment planning in general (Sommers-Flanagan

1982 to 1991, and 519 appeared in the 7-year, 3-month pe- & Sommers-Flanagan, 1998). Counselors cannot determine

riod from 1992 to March 2000. Of the 3,457 dissertations the best treatment techniques unless they diagnose effectively

generated since 1861 in which the term self-esteem appears (Hohenshil, 1995).

Mary H. Guindon is an assistant professor and chair in the Department of Counseling and Human Services at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore,

Maryland. Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to Mary H. Guindon, Department of Counseling and Human Services, Johns Hopkins

University, 9601 Medical Center Drive, Rockville, MD 20850 (e-mail: mguindon@jhu.edu).

© 2002 by the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved. pp. 204–214

204 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80

To w a r d A c c o u n t a b i l i t y i n S e l f - E s t e e m U s a g e

It may be that counselors are routinely making an infor- his students: “the diversity of definitions tends to be im-

mal “diagnosis” of low self-esteem in their clients without a pressive. Often, it is as though there are as many ways to

grounding in its meaning or practice in its assessment. It define self-esteem as there are people trying to do so” (p. 8).

seems that, as professional counselors, most of us think we Nevertheless, a body of knowledge on the meaning of self-

know what self-esteem is and tend to take its meaning for esteem exists; theorists have investigated the meaning of

granted (Hoyle, Kernis, Leary, & Baldwin, 1999; Robson, self-esteem as it is subsumed under the category of self-

1988). Relying on common sense can be misconstrued in concept for more than a century. It is its consistency of

diagnosis and treatment and gives an impression of precise- usage within the helping professions and in the popular con-

ness where none exists. Consequently, counselors may not be sciousness that seems to be in question.

effectively addressing the concerns of their clients nor Yet self-esteem is one of the earliest areas of investigation

providing counseling that appropriately affects levels of self- in the modern field of psychological inquiry. Although an im-

esteem. At a time when counselors in all settings are being pressive diversity of definitions plague the field, definitions

called upon to be accountable for the quality of their services that merit attention have stood the test of time and are based

(Steenbarger & Smith, 1996) and counselors have faced on theoretical work that, through persistence or significance,

increasing demands to be accountable for their own effec- have become a standard of comparison for subsequent work

tiveness as measured by outcomes studies (Whitson, 1996), (Mruk, 1999). These works include definitions that describe an

this lack of attention to accountability in the use of self- attitude toward the self and include self-esteem’s affective and

esteem seems especially curious. As accountability continues evaluative components (Cooley, 1902; Coopersmith, 1967,

to be a prominent issue for the counseling profession, accu- 1981; James, 1890; Mead, 1934; Pope, McHale, & Craighead,

rate assessment becomes even more critical in delivering 1988; Rosenberg, 1965, 1979; Smelser, 1989; Wells & Marwell,

services. Accountability means no less than documenting 1976; White, 1963; Ziller, 1969). A brief review of how the

counselor effectiveness through the use of measured means; study of self-esteem has developed and a discussion of the

counselors must be able to document that the procedures and evolving definition of self-esteem, its dual nature, and its

methods they use are effective (Gladding, 2000). It follows relationship to related “self” terms will enable a more thorough

then that a clear understanding of the self-esteem construct understanding of the construct.

and the ability to assess levels of self-esteem are necessary

skills in assisting counselors to develop individual, group, The Evolution of the Self-Esteem Construct

and systemic interventions designed to optimally affect

positive self-esteem development and enhancement. Given James (1890) defined self-esteem as a summary evaluation

the prevalence of self-esteem as an area of inquiry, its popu- that reflects a ratio of our “pretensions” divided by our

larity as a target of intervention, and the continued prolif- “successes” (p. 310). Self-esteem reflects a “baseline” feel-

eration of research into its nature, it seems reasonable to ing of worth, value, liking, and accepting of self that one

expect counselors to be cognizant of its meaning, account- carries at all times regardless of objective reality. Cooley

able for how they use the term, and careful that they do not (1902) postulated that the self is determined and judged by

make statements about levels of self-esteem in their clients the perception of others. Mead (1934) saw the self as a product

without some way of having responsibly assessed it. of interactions in which the individual experiences him- or

The purpose of this article is to provide a step toward herself as reflected in the behavior of others. Rogers (1951)

accountability in the use of the self-esteem construct. To referred to self-esteem as the extent to which a person likes,

achieve this objective, this article is organized into three values, and accepts him- or herself. Unconditional, positive

major sections. First, it provides an overview of the con- self-regard is dependent on the unconditional positive regard

struct, explains its development, and defines it. Second, it of significant others (Rogers, 1959). White (1963) described

presents a brief discussion of the significance of self-esteem. self-esteem as a process developing from two sources: an in-

Third, it examines self-esteem assessment and presents a ternal source of a sense of accomplishment and an external

practical overview of common self-esteem instruments. By source of affirmation from others. Maslow (1968) defined

calling for consistency in how we define self-esteem and self-esteem as “the desire for strength, for achievement, for

working toward responsibility in ways in which self-esteem adequacy, for mastery and competence, . . . and for indepen-

can be assessed, interventions aimed at enhancing it can be dence and freedom” (p. 45).

used with greater effectiveness. Rosenberg (1965, 1979) and Coopersmith (1967) each de-

veloped a theory of self-esteem as a significant personality

DEFINING SELF-ESTEEM construct based on empirical methods. Both reached similar

conclusions. Concerned with the development of a positive

Self-esteem, a deceptively simplistic construct, is more com- self-image during adolescence, Rosenberg (1965) considered

plex than it may first seem. Indeed, most counselors and self-esteem to be global, a unidimensional phenomenon, an

other mental health practitioners “seem to know” what self- attitude toward a specific object, the self. According to him,

esteem is, yet few can define it precisely. For example, my attitudes about every characteristic of the self have an evalu-

experience with counseling students and workshop partici- ative dimension that results in a self-estimate of that charac-

pants substantiates Mruk’s (1999) own observation with teristic. Each element of the self is actually rated and judged

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80 205

Guindon

against a self-value that has developed during childhood and manifest indicator of self-esteem level when another ele-

adolescence. Feedback from others, particularly significant ment altogether may be of concern to the client. Self-

others, is an important element of self-esteem (Rosenberg, esteem, then, at once global and selective, seems to be made up

1979). Yet self-esteem is also unconditional in the sense that of individual constituent elements that vary in importance to

the person respects (or does not respect) him- or herself in- the self. Self-esteem seems to be a fluctuating self-attitude in-

dependent of qualities or accomplishments (Rosenberg, 1985). fluenced by “changing roles, expectations, performances, re-

Coopersmith (1967) researched pre-high-school children and sponses from others, and other situational characteristics”

saw self-esteem as a more complex phenomenon involving self- (Demo, 1985, p. 1491). Jane, for example, may have a strong

evaluation and manifestations of defensive reactions to that sense of general, or global, self-esteem but may manifest

evaluation. Self-esteem consists of two parts: subjective ex- feelings of low self-esteem about the size of her nose or her

pression and behavioral manifestation. Coopersmith (1967) inability to do math; may exhibit feelings of high self-

attempted to address both true self-esteem (manifested in those esteem about her popularity among her peers; and may tem-

who actually feel worthy and valuable) and defensive self- porarily show characteristics of low self-esteem when she is

esteem (manifested in those who feel unworthy but who can- in a situation in which she feels incompetent or demeaned

not admit this threatening information). Coopersmith’s (1981) by someone important to her.

definition included a decision of personal worthiness, a judg- Therefore, self-esteem seems to vary across different areas of

mental process in which “performance, capacities, and attributes” experience and according to role-defining characteristics

are examined according to personal standards and values that (Coopersmith, 1981). It seems to be situational—high at one

develop during childhood. It focuses on the “relatively endur- moment or low at another—depending on which specific

ing estimate of general self-esteem rather than on specific and constituent personal identity element the individual attends to

transitory changes in evaluation” (p. 5). (Harter, 1985; Leahy, 1985; Rosenberg, 1985). Accordingly, the

These two theorists were followed by others, who reiter- individual may have generally positive attitudes toward

ated, extended, or refined these basic elements. Fitts (1972) the self, possess a good sense of self-worth, but because of

suggested that self-esteem is primarily a result of the judg- certain situations or particular days may feel better or worse

ments of significant others, thus supporting Coopersmith’s about him- or herself (Demo, 1985) at any one time.

(1967) view. Wells and Marwell (1976) categorized existing This attitudinal perspective that regards self-esteem as at

definitions as attitudinal toward the self as the object of at- once both general and specific means the person attaches evalu-

tention; as relational between different sets of self-attitudes; ations to many different qualities and aspects of the self and

as psychological responses toward the self; and as a function also sums these to form an overall evaluation. Rosenberg (1965)

of personality, a part of the self-system. Gecas (1982) pointed described self-esteem as a linear combination of individual and

out a distinction between self-esteem based on a sense of specific self-estimates, each weighted by a value and then

competence, power, or efficacy and self-esteem based on a summed. The weight of each value is dependent on how im-

sense of virtue or moral worth. Competency-based self- portant the value is to the individual. The person’s overall

esteem is related to effective performance and is associated appraisal of self presumably weighs all areas according to their

with self-attribution and social comparison processes. Self- subjective importance and arrives at what Coopersmith (1981)

esteem based on self-worth, or virtue, is grounded in values referred to as a general level of self-esteem.

and norms of personal and interpersonal conduct. Sense of Rosenberg (1979) stated that many personal elements are

worth may be strongly affected by sense of competence and socially ranked and evaluated, that the individual’s sense of

vice versa (Gecas, 1982). Pope et al. (1988), echoing James’s personal worth or value (viz., self-esteem) is to some ex-

(1890) original work, defined self-esteem as the evaluation tent contingent on the perceived prestige of the identity

of information within the self-concept that arises from the element. Therefore, a person’s global sense of self-esteem is

discrepancy between the perceived self and the real self. based “not solely on an assessment of his constituent quali-

Frey and Carlock (1989) also recognized self-esteem as an ties but on an assessment of the qualities that count [italics

evaluative term and discussed the components of competence added]” (Rosenberg, 1979, p. 18). Wylie (1974) and Gurney

and worthiness as interrelated. Mruk (1999) considered self- (1986) suggested a hierarchical relationship between specific

esteem as an interaction between worthiness and competence and global self-esteem rather than a qualitative difference

and conceptualized a self-esteem matrix indicating a con- between them. Brown (1993), on the other hand, supported

tinuum of competent or effective behavior. conceptualizing self-esteem in terms of global feelings sepa-

rate from specific self-evaluation, arguing that global self-

Dual Nature of Self-Esteem esteem affects specific self-evaluations, not the reverse. In any

case, generalizations cannot be made from either the specific

Self-esteem as the evaluative component of the self- to the global or from the global to the specific. It is pre-

concept seems to be at once global (general) and selective cisely this confusion that may result in self-esteem inter-

(specific or situational). This latter attribute lends confu- ventions not fitting the needs of the client; the client may

sion and may lead to imprecision in applying self-esteem feel something entirely different from what the counselor

interventions to issues affecting clients. The counselor may assumes. The counselor may be attending to a different self-

be attending to one situational element in the client as a element altogether. Or, the counselor may be placing more

206 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80

To w a r d A c c o u n t a b i l i t y i n S e l f - E s t e e m U s a g e

or less importance on the significance of the element than the construct. Competence and achievement seem to be in-

does the client. For example, John may play the piano ex- tegral elements of self-esteem and seem to be intertwined

ceptionally well, but if it does not matter to him, if this with an evaluation and awareness of self-worth. This aware-

accomplishment carries a low weight, his counselor’s well- ness is formed, at least in part, from the judgment of and

intentioned validation of his piano-playing skill as a way to feedback from others. The reactions of significant others play

bolster his self-esteem is likely to be ineffective. a part in self-esteem levels. In addition, there seems to be

more than one kind of self-esteem. The point is, in order to

Relationship to Related Self Terms operationalize self-esteem, it may be productive to con-

sider this construct as a self-esteem system. Counselors and

Another point of confusion regarding self-esteem may have

other helping professionals, who are those most concerned

to do with the construct’s close relationship to other simi-

with affecting levels of self-esteem, need to be precise in

lar constructs. Self-esteem is associated with, but not iden-

how they use this construct. Consequently, this article calls

tical to, several other constructs that make up the study of

the self, an area with a controversial history of its own for the consistent use of the following definitions, which are

(Szymanski & O’Donohue, 1995). Because the self cannot grounded in the professional literature:

be directly observed, its study has been difficult and open

1. Self-esteem: The attitudinal, evaluative component of

to varying interpretations from the beginning. Many shades

the self; the affective judgments placed on the self-

of meaning differentiate self-esteem from other closely re-

concept consisting of feelings of worth and acceptance,

lated terms. Self-concept as the most general of the terms is

broadly conceptualized as a person’s perceptions of him- or which are developed and maintained as a consequence

herself that are formed through an individual’s experiences of awareness of competence, sense of achievement, and

feedback from the external world.

with and interpretations of his or her environment

2. Global self-esteem: An overall estimate of general self-

(Shavelson, Hubner, & Stanton, 1976). People may appraise

worth; a level of self-acceptance or respect for one-

themselves on multiple dimensions, making judgments about

self; a trait or tendency relatively stable and enduring,

what they are like (self-concept) and reacting emotionally

to an evaluation (self-esteem) (Szymanski & O’Donohue, composed of all subordinate traits and characteristics

1995). Wylie (1974) considered self-esteem to be synonymous within the self.

3. Selective self-esteem: An evaluation of specific and con-

with what she called “self-regard,” an umbrella term she used

stituent traits or qualities, or both, within the self, at

to described the attitudes toward the self and that included

times situationally variable and transitory, that are

“self-satisfaction, self-acceptance, self-esteem, self-favorability,

weighted and combined into an overall evaluation of

congruence between self and ideal self, and discrepancies

between self and ideal self” (pp. 127–128). self, or global self-esteem.

Self-efficacy refers to a person’s assessment of effective-

By understanding the meaning of self-esteem and know-

ness, competency, and causal agency (Bandura, 1977; Gecas,

ing its definitions, the counselor can be precise in its use and

1989). Although White (1963) believed that self-esteem

judicious in choosing interventions targeted at increasing

begins with self-efficacy, high self-esteem does not neces-

levels of self-esteem in individuals and in group settings.

sarily reflect high feelings of efficacy (Rosenberg, 1985).

Self-confidence refers to the “anticipation of successfully Global self-esteem seems to be less amenable to change than

mastering challenges or overcoming obstacles [whereas] . . . does selective self-esteem. However, the fact that global

self-esteem is composed of selective self-esteem elements

self-esteem . . . implies self-acceptance, self-respect”

may mean that a change in level of overall self-esteem is

(Rosenberg, 1979, p. 31). Persons high in self-esteem exhibit

contingent upon changes in evaluation of these specific, sub-

confidence in their perceptions and judgments and gener-

ordinate units within the self-system, which in turn affects

ally believe that they can favorably resolve their concerns

through their own efforts (Coopersmith, 1967). Still, global the overall, or global, level of self-esteem. By attending to

self-esteem seems to be distinct from social confidence selective self-esteem traits or characteristics that are im-

portant to the client manifesting low self-esteem, the coun-

(Fleming & Watts, 1980). Keeping in mind the various mean-

selor may more likely be able to assist that client in ulti-

ings of these related self-constructs and how they relate to

mately increasing his or her level of overall self-esteem.

self-esteem will assist the counselor in lessening the confu-

sion surrounding this construct.

SIGNIFICANCE OF SELF-ESTEEM

Toward the Use of a Consistent Definition of Self-Esteem

A reason for the preeminence of self-esteem research is that

Despite variations in how self-esteem has been conceptual- it seems to have motivational significance; much of behav-

ized, certain common threads are present. Drawing from the ior is determined by how one assesses one’s own sense of

theories that have stood the test of time, which still stand worth (Gecas, 1982; Rosenberg, 1965; Wylie, 1974). The

today as landmarks in understanding self-esteem, and that motivation to maintain and enhance a positive sense of self

are accepted and widely used, these commonalties and may be universal because it stimulates dissonance-reducing

consistencies allow us to form a clearer understanding of actions (Gecas, 1982; H. B. Kaplan, 1975; Rokeach, 1979;

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80 207

Guindon

Rosenberg, 1979). What individuals choose to do and the to any conclusions about their clients’ levels of self-esteem.

way they do it may be dependent, in part, on their self- Considering “multiple and repeated measures to obtain

esteem. It seems to be correlated with functional behavioral ‘snapshots’ of an individual’s self-esteem in different social

and life satisfaction (Bednar & Peterson, 1995; Gurney, 1986) situations” (Demo, 1985, p. 1491) allows the counselor to

and is significantly related to physical and mental well-being better ascertain more realistic and accurate approximations

(Witmer & Sweeney, 1992). The Diagnostic and Statistical of the construct.

Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV; Ameri-

can Psychiatric Association, 1994), includes self-esteem among Methods of Assessing Self-Esteem

the diagnostic criteria for some mental disorder catego-

ries, and self-esteem seems to be related to depression and In their landmark review of self-concept methodologies,

dysthymia. Wells and Marwell (1976) stated that all instruments have

Countless studies have been conducted on student self- biases and that relying on a single form of measurement is

esteem and academic performance. Factors influencing students’ inadequate. Counselors have several options before making

low academic performance point to low self-esteem as both an decisions about self-esteem levels in their clients: pencil-

antecedent and a consequent component. In general, high self- and-paper self-reports, ratings by others (e.g., teacher, school

esteem seems to be a consequence of having experienced success counselor, or parent), behavioral observation (e.g., partici-

(Holly, 1987). Other research, however, suggests that there is no pant observers and peers), and interview methods.

positive correlation between self-esteem and academic achieve- However, assessment of any kind does not begin with ad-

ment in certain student populations (Ginter & Dwinell, 1994; ministering an assessment instrument but by observations

Pottebaum, Keith, & Ehly, 1986), and it is one’s actual ability made as soon as the client meets the counselor. The counse-

rather than perceived ability that seems to be a determinant lor asks why the client is there and not only attends to

of self-esteem and makes a difference in academic success content but also observes the client process and style (Bednar

(Bachman & O’Malley, 1986). & Peterson, 1995). Assessment can be described as a process

Hundreds of articles substantiate or repudiate self-esteem’s that requires participation from and interaction between

antecedent or consequent role in human behavior. These both counselor and client. Counselors are responsible for

conflicting results underscore further the need for counse- taking information gathered from an assessment and devel-

lors to understand the construct, account for how they use oping a treatment plan based on individual needs (Fong,

the term, and how they assess it. Mruk (1995) stated that 1993; Seligman, 1996). The same principle should apply

“Measuring self-esteem is important because if this field before making judgments about self-esteem levels if inter-

wishes to achieve a higher degree of reliability and validity, ventions targeted toward self-esteem enhancement are to

then it must attempt to demonstrate observable, . . . mea- be incorporated into treatment planning.

surable relationships between self-esteem and the kinds of The use of standardized pencil-and-paper self-report in-

behavior commonly held to be related to it” (p. 42). struments is the primary and most reliable means of ascer-

taining self-esteem levels and is discussed in greater detail

SELF-ESTEEM ASSESSMENT in the following section. Ratings by others, behavioral ob-

servations, and interview methods are subjective means of

However precisely they may use its definition, counselors assessment. The use of these methods as alternatives to

and other helping professionals need to be sure they do not traditional paper-and-pencil tests can clarify distinctions

make statements about self-esteem, nor plan interventions, between experienced and presented self-esteem (Demo,

without some basis for having assessed it as accurately as 1985; Savin-Williams & Jaquish, 1981). Estimates of experi-

possible. It is important to note that there are problems enced self-esteem, indicated by self-reports, and presented self-

inherent in assessing self-esteem. Mruk (1999) stated that esteem, most often assessed through observation, may vary

self-esteem is an impure phenomenon closely related to other (Demo, 1985). Although self-ratings can capture meaning-

self-phenomena, all of which are problematic to assess. ful personal information unavailable to others (Hamilton,

Some instruments purported to measure self-esteem are, 1971), they are an inherently fallible source of data in which

in actuality, measuring a sum of various self-descriptions minor changes in questions, wording, format, or context can

that may be a different concept than self-esteem (Skaalvik, result in major differences in results (Schwarz, 1999). On the

1986) Poor quality instruments are also a problem (Street & other hand, observer ratings provide information about the

Isaacs, 1998). Nevertheless, if counselors target self-esteem level of self-esteem communicated to others (Demo, 1985),

enhancement as a goal in treatment planning, using assessment but ratings by others by their nature must infer information,

instruments, even if not perfect, and other assessment tech- making them susceptible to obscuring and distorting perspec-

niques to measure levels of self-esteem is preferable to no tives of an individual’s self-esteem (Demo, 1985). Vaac and

assessment at all. Juhnke (1997) stated that counselors have used the interview

Achieving a sound degree of scientific validity is difficult. as a powerful assessment tool and, although this is certainly

This sets the limits within which we can realistically ex- true in the assessment of self-esteem, this method is subject

pect certainty in our assessment results, and the counselor to interviewer bias. However, despite the fact that many

is well advised to use more than one resource before coming useful structured and semistructured interview formats are

208 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80

To w a r d A c c o u n t a b i l i t y i n S e l f - E s t e e m U s a g e

available (see Vaac & Juhnke, 1997), none specifically target means it is important to consider how the test developer

self-esteem. has defined self-esteem and to use the assessment only within

These alternatives to standardized assessments may be useful that context. Is the instrument suitable in assessing global

in yielding corroborative evidence but are susceptible to distor- self-esteem only? Are there areas of selective self-esteem

tion because of a lack of consistency and agreement on manifest that can be assessed by this instrument? If so, are these areas

characteristics of self-esteem. To date, although few researchers indicative of global self-esteem levels or are they measuring

have addressed the characteristics of low and high self-esteem only transitory characteristics?

per se, one multiple regression study indicated that interviewer 2. Read test reviews. Reviews of available instruments can

ratings were congruent with respondents’ self-reported self- be found in the professional literature (Bracken & Mills,

esteem (Tran & O’Hare, 1996). In a study of perceptions of 1994; Chiu, 1988; Demo, 1985; Robinson et al., 1991), in

self-esteem by teachers, counselors, and school administra- Test Critiques (Keyser & Sweetland, 1998), in Tests in Print

tors (Scott, Murray, Mertens, & Dustin, 1996), all groups were (Murphy, Conoley, & Impara, 1994), and in Buros Mental

uniform in how they perceived indicators of high self-esteem Measurements Yearbook (Conoley & Impara, 1995). Readers

but were not uniform about indicators of low self-esteem. One are directed to these sources of information.

viewpoint of low self-esteem indicates the opposite and holds 3. Continually ask a set of questions:

that its characteristics consistently involve a high level of mal- A. Does this instrument measure what it purports to

adaptive behaviors and include anxiety and depression (Harter, measure? The technical manual should give an oper-

1993; Watson & Clark, 1984). Another viewpoint holds that ating definition of self-esteem. Does this definition

high self-esteem can be maladaptive and characterized by an fit the questions asked in the assessment? Does it

overinflated sense of self (Hoyle et al., 1999). Characteristics of indicate strong empirical support for its validity?

low or high self-esteem can be in the eye of the beholder. My B. Does this instrument measure what I need to know

tentative and exploratory research survey that asked counselors about this client? Is it normed on a population ap-

to describe self-esteem characteristics indicates little agreement propriate for this client? Does the instrument in fact

and in some cases diametrically opposed perceptions (e.g., aggres- measure the general or specific trait or characteristic

siveness is perceived as a characteristic of both high self-esteem in question? Does it have utility? Can its results be

and low self-esteem). used to indicate a direction for intervention?

Clearly, assessing self-esteem is an imprecise but neces-

sary activity. Findings to date suggest that no single assess- It is beyond the scope of this work to critique self-esteem

ment procedure will accurately pinpoint self-esteem levels assessment instruments, but it seeks rather to present a com-

and that no one individual rater can consistently make pendium of those instruments historically recognized and

accurate judgments regarding self-esteem in any one client. most widely used so that the counselor can make informed

Thus the best avenue to assess self-esteem is triangulation. choices. A search of the literature using an online query of

Triangulating results by using multimethod, multirater, and ERIC and PsycINFO databases yielded a selection of instru-

multisetting assessment procedures will yield richer results. ments that seem to be most commonly used in many con-

It is recommended, therefore, that counselors use one or texts, and this search substantiates an earlier review

more standardized assessment instruments and supplement (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991). Crandall (1973) identified

the information with one or more of the aforementioned an initial set of self-esteem scales for review. Blascovich and

subjective, qualitative methods. Tomaka (1991) supplemented the original work through

online title and abstract queries that yielded over 30,000

Self-Esteem Assessment Instruments references, leading them to limit their search through use of

There are over 2,000 self-esteem-related assessment instruments the Social Sciences Citation Index. Blascovich and Tomaka

(Mecca, Smelser, & Vasconcellos, 1989; Mruk 1999). Most are identified 40 self-esteem instruments, based on frequency of

self-report questionnaires and exhibit those problems inherent citation. The resulting frequencies were divided by the num-

in all self-report measures, such as semantic understanding, ques- ber of years since publication of each individual instrument,

tion format, social desirability, and self-presentation (Schwarz, thus arriving at yearly frequencies, which were then rank

1999). In a review of self-esteem assessments, Blasocvich and ordered. Using a similar method, I updated findings using

Tomaka (as cited in Robinson, Shaver, & Wrightsman, 1991) ERIC (1993 through March, 2000) and PsycINFO (1993

stated, “neither a firm body of evidence nor a convincing defi- through June 2000) and found 58 self-esteem instruments.

nitional rationale to justify many of the ‘self-esteem’ measures The results of this search support Blascovich and Tomaka’s

exists” (p. 119).When reviewing any assessment instrument—and (1991) findings of the wide array and usage of these instru-

this is especially critical in self-esteem assessment—counselors ments in the literature and indicate their popularity, but

should follow some basic steps in determining its appropriateness not necessarily their appropriateness, as measures of self-

for their particular situation. esteem. The updated search yielded similar rank orderings

for the top four instruments. Table 1 presents Blascovich

1. Study the technical manual. When choosing any self- and Tomaka’s earlier results in Columns 1 and 2. Columns

esteem instrument, as with any instrument, the counselor 3 and 4 show a 1991 through 1999 updated parallel search

needs to evaluate its utility, reliability, and validity. This for Social Sciences Citation Index. It is worth noting that this

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80 209

Guindon

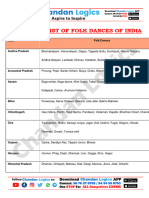

TABLE 1

Self-Esteem and Self-Concept Scales Listed in Order of Number of Citations Per Year

Social Sciences Citation Index ERIC/PsycINFO

Through 1990 a 1991–1999 1993–2000

b c

Instrument Frequency Frequency/Year Frequency Frequency/Year Frequency Frequency/Yeard

Self-Esteem Scale (SES;

Rosenberg, 1965) 1,285 61.2 213 23.7 425 56.7

Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI;

Coopersmith, 1967, 1981) 942 54.6 123 13.7 192 25.6

Tennessee Self-Concept Scale

(TSCS; Roid & Fitts, 1988) 527 24.9 44 4.9 110 14.6

Piers-Harris Children’s Self-

Concept Scale (P-HCSCS;

Piers, 1984) 365 20.3 37 4.1 117 15.6

The Body-Esteem Scale (BES;

Franzoi & Shields, 1984)e 192 9.1 28 3.1 40 5.3

Culture-Free Self-Esteem

Inventories, 2nd edition (CFSEI-2;

Battle, 1992) n/a n/a 15 1.7 31 4.1

Note. An estimate may be inflated due to nonscale-related citations.

a

The data in Columns 1 and 2 are from “Measures of Self-Esteem,” by J. Blascovich and J. Tomaka, in Measures of Personality and Social

Psychological Attitudes (pp. 115–160), by J. P. Robinson, P. S. Shaver, and L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), 1991, San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Copyright 1991 by Academic Press, Inc. Reprinted with permission. bNumber of years since inception of publication of instrument. cNumber of

years = 9. dNumber of years = 7.5. eRevision of the Body-Cathexis Scale (Secord & Jourard, 1953).

source did not show the citations available elsewhere. Con- test developers’ purpose; indicates the appropriateness of

sequently, Columns 5 and 6 indicate results for a combined the instrument in assessing global self-esteem and selective

ERIC (1993 through March, 2000) and PsycINFO (1993 self-esteem areas, or both; and provides information about

through June 2000) search. The four instruments for the format, age range, number of items, and special concerns.

measurement of self-esteem that appear consistently and SES (Rosenberg, 1965). The SES is a unidimensional mea-

most frequently are the Self-Esteem Scale (SES; Rosenberg, sure of global self-esteem. It can be administered individu-

1965), Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI; Coopersmith, 1981), ally or in groups. Widely used as a research instrument and

Tennessee Self-Concept Scale (TSCS; Roid & Fitts, 1988), considered by most reviewers to be a valid measure of

and Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (P-HCSCS; global self-esteem, it is available only in the original text,

Piers, 1984). Other assessment instruments reported by now out of print, and may be difficult for practitioners to

Blascovich and Tomaka (1991) had either fallen out of usage locate. Although its uses and applications are not described,

altogether, did not yield results high enough to be consid- it is considered the standard by which other self-esteem

ered for the purposes of this article, had serious method- instruments are judged.

ological inadequacies (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991), or did not SEI (Coopersmith, 1981). Also a unidimensional measure

appear to add any qualitatively new or different additional of self-esteem, the SEI is available in two forms for children.

information about self-esteem. Two additional instruments are The longer Form A has three subscales, which purport to

included in this article because they fill a need in the field. The measure three possible broad selective self-esteem areas

Body-Esteem Scale (BES; Franzoi & Shields, 1984), a form of (peers, parents, school), plus a lie scale. Suitable for individual

which ranked 9th in the earlier study, was chosen for inclusion or group administration, suggested uses include screening,

because it is a reliable measure of one kind of selective self- instructional planning, program evaluation, and clinical

esteem and because body image has been shown to be highly studies. A third, less-used form adapted for adults is also

correlated with global self-esteem. The Culture-Free Self- available from the publisher.

Esteem Inventories, second edition (CFSEI-2; Battle, 1992), was TSCS (Roid & Fitts, 1988). The TSCS is a multidimensional

chosen because it adds a dimension that seems to be overlooked measure of the self-concept. It can be administered individu-

in the other self-esteem assessments. Although not truly “culture ally or in groups. A highly popular assessment instrument, the

free,” this assessment attempts to address cultural bias. TSCS can be used as a measurement of self-esteem because

Although there are many other useful instruments, these it provides a total score that purports to reflect overall

six assessments have wide appeal and are straightforward to (global) self-esteem. Ten of its 100 items assess “self-criticism.”

complete. They may assist counselors to assess self-esteem It is available in a counseling version (Form C) and a re-

in their clients and can be easily administered individually search version (Form R). Subdomains (subscales) include

or in groups. Information provided in Table 2 is intended to Identity, Self-Satisfaction, Behavior, Physical Self, Moral-

help counselors in making suitable choices. It presents the Ethical Self, Personal Self, Family Self, and Social Self. The

210 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80

To w a r d A c c o u n t a b i l i t y i n S e l f - E s t e e m U s a g e

TABLE 2

Assessment Instruments Appropriate for Self-Esteem Measurement

Instrument

With Citation Purpose G/Sa Format Age Range Number of Items Concerns

Self-Esteem Scale G only. Unidimen- 4-point responses to High school through 10 Susceptible to social

(SES; Rosenberg, sional measure of self-descriptive adult desirability re-

1965) (Also global feelings of statements sponse. Tends to be

available is a 6-item self-worth and negatively skewed

SES targeted acceptance; for college age.

toward children estimates positive

below high school or negative feelings

age, see Rosenberg about the self.

& Simmons, 1972.)

Self-Esteem Inventory Form A: G and S with Forced choice (“like Ages 8 through 15 Form A: 50 Susceptible to social

(SEI; Coopersmith, caution. Form B: G me,” “not like me”) Form B: 25 desirability

1981)b only. Measures “self- responses to self- (first half of Form A) response. Tends to

regard”; Form A has descriptive be negatively

three subscales: statements skewed.

Social Self-Peers,

Home-Parents,

School-Academic,

plus a lie scale.

Tennessee Self- G (total score). S 5-point responses to Ages 12 and above 100 Support only for

Concept Scale (social, family, self-descriptive family, physical, and

(TSCS; Roid & Fitts, physical, moral- statements social subscales

1988) ethical, personal (Marsh & Richards,

categories). 1988).

Multidimensional

view of the self-

concept; popular as

a general measure

of self-esteem.

Piers-Harris G only. Measures Forced choice (yes/ Ages 8 through 18 80 Susceptible to social

Children’s Self- self-concept; no) responses to desirability

Concept Scale synonymous with predominantly self- response; most

(P-HCSCS; Piers, self-esteem/regard. descriptive suitable to younger

1984) Subscales demon- statements. groups.

strate substantial

overlap (Blascovich

& Tomaka, 1991).

The Body-Esteem S only. Measures 5-point responses College age 40 Social desirability

Scale (BES; Franzoi degree of feelings rating feelings about response bias not

& Shields, 1984) with various body body parts and determined but

parts or processes. functions including considered moder-

gender-specific ate (Blascovich &

subscales. Tomaka, 1991).

Culture-Free Self- Measures perception Forced choice (yes/ Forms A & B: Grades Form A: 60 True “culture free”

Esteem Inventories, of self/self-esteem no) self-report 3–12. Form AD: Form B: 30 status in question.

2nd edition (CFSEI- independent of checklists. Adults Form AD: 40 Tends to be

2; Battle, 1992) cultural context. Form negatively skewed.

A: G (general items

subscale), S with

caution. Subscales

are Social/Peers

Related; Academic/

School Related;

Parents/Home

Related; and lie items.

Form B: G only. Form

AD: G (general items

subscale). S with

caution. Subscales

are social, personal,

and lie items.

Note. See Table 1 Note.

a

G = suitable as a measure of global self-esteem. S = suitable as a measure of selective self-esteem. bAdult form adapted from Form B is also

available.

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80 211

Guindon

second edition of this instrument (Fitts & Waren, 1998) has 1. Be familiar with self-esteem definitions and terms. Con-

an additional subscale measuring academic and work self- sistency in the use of the concepts of global and se-

esteem. Although it might be considered in assessing selec- lective self-esteem is a first step. Counselors need to

tive self-esteem, it must be noted that it is has come under understand that competence, sense of accomplish-

considerable criticism by reviewers (Marsh & Richards, 1988) ment, and feedback are critical elements in develop-

and is generally recommended for this use only with caution. ing and maintaining self-esteem. Counselors should

P-HCSCS (Piers, 1984). This instrument is used as a unidi- keep in mind that self-esteem varies across charac-

mensional measure of self-esteem because it defines self-con- teristics and situations and its constituent elements

cept as “a relatively stable set of self-attitudes reflecting both are weighted differently by different clients.

a description and an evaluation of one’s own behavior and 2. Use multiple assessment methods. Accountability

attitudes” (Piers, 1984, p. 1). It can be administered individu- means not only using definitions appropriately but

ally or in groups. Items include the six subdomains (subscales): also being careful not to prejudge behavior or overt

Behavioral, Intellectual and School, Physical Appearance and characteristics as indicating self-esteem problems.

Attributes, Anxiety, Popularity, and Happiness and Satisfac- Accountability means assessing levels of self-esteem

tion, but the P-HCSCS is not recommended as a measure of and using more than one approach whenever possible.

selective self-esteem because of substantial overlap in Use of qualitative methods are critical and necessary.

subscales. It is currently used in both research and in clinical When standardized self-esteem instruments are

settings and may be the most psychometrically sound instru- used, choosing the most reliable, valid, and useful

ment available (Hughes, 1984; Wylie, 1974). instrument to fit the needs of the individual should

BES (Franzoi & Shields, 1984). The BES is a multidimen- be common practice.

sional measure of body self-esteem. A revised version of the 3. Become well versed in differences in behavior style

Body-Cathexis Scale (Secord & Jourard, 1953), it measures across cultures and contexts. Varying family dynamics and

feelings about various body parts and bodily processes. Use- environmental factors may account for attitudes

ful as a measure of selective self-esteem targeting physical and behaviors assumed to be related to self-esteem

attributes, it may also give an indication of global self-esteem problems when no such problem may exist. Defer-

insofar as body image is correlated with general self-esteem ence to authority, for example, can be misconstrued

levels. It can be administered individually or in groups. It is as low self-esteem when, in fact, it may be a cultur-

used in research and clinical settings and is the only one of ally bound phenomenon. Whereas most counselors

these six instruments that includes gender-specific subscales. continue to become culturally aware and sensitive,

CFSEI-2 (Battle, 1992). The CFSEI-2 is a multidimensional the manifestations of self-esteem across cultures is

measure of self-esteem available in three forms. For young underrepresented in the research literature.

children, individual oral administration is recommended; 4. Be aware of personal self-esteem issues. Counselors need

for older children or adults, individual or group administra- to consider their own reactions to low self-esteem

tion is possible. This is a battery of self-esteem statements manifestations. They may wish to consider partici-

using a standardized oral administration. In addition to a pation in peer counseling groups attending to their

general level of self-esteem appropriate to assessing global own self-esteem needs. As with other concerns, peer

self-esteem, it claims to assess several subdomains (three supervision is also recommended.

subscales; Social/Peers Related, Academic/School Related, 5. Attempt to use suitable intervention strategies. Greater

and Parents/Home Related, plus lie items) and thus can be precision in the use of the self-esteem construct will

considered a measure of selective self-esteem. Although enable the counselor to discriminate effective versus

not really “culture free,” it attempts to address cultural ineffective strategies among the abundance of self-

bias and is available in three languages (English, French, esteem resources so easily available to them. Inter-

and Spanish). It can be valuable as a screening device in ventions aimed at enhancing self-esteem can be de-

identifying individuals who may need counseling (Chiu, veloped that are appropriate and meaningful and

1988). In addition, it claims to assess therapeutic progress grounded in its definition and assessment.

and evaluate posttherapy effects.

REFERENCES

CONCLUSION American Counseling Association. (1995). Code of ethics and standards

of practice. Alexandria, VA: Author.

This article has called for accountability in the use of the

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical

self-esteem construct, presented a review of its development, manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

offered definitions of the self-esteem system grounded in the Bachman, J., & O’Malley, P. (1986). Self-concepts, self-esteem, and

professional literature, discussed its assessment, and presented educational experiences: The frog pond revisited (again). Journal of

a compendium of widely used self-esteem assessments. Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 35–46.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behav-

To work toward accountability and systematically address ioral change Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

issues associated with self-esteem in their clients, counselors Battle, J. (1992). Culture-Free Self-Esteem Inventories (2nd ed.). Austin,

and other helping professionals can benefit from these principles: TX: PRO-ED.

212 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80

To w a r d A c c o u n t a b i l i t y i n S e l f - E s t e e m U s a g e

Bednar, R. L., & Peterson, S. R. (1995). Self-esteem: Paradoxes and innova- Hohenshil, T. (1995). Editorial: Role of assessement and diagnosis in counsel-

tions in clinical theory and practice (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Ameri- ing. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75, 64–67.

can Psychological Association. Holly, W. (1987). Student self-esteem and academic success. OSSC Bulletin

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In J. P Series, Eugene, OR: Oregon School Study Council, University of Oregon.

Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality Hoyle, R. H., Kernis, M. H., Leary, M. R., & Baldwin, M. W. (1999). Selfhood:

and social psychological attitudes (pp. 115–160). San Diego, CA: Identity, esteem, regulation. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Academic Press. Hughes, H. M. (1984). Measures of self-concept and self-esteem for children

Bracken, B. A., & Mills, B. C. (1994). School counselors’ assessment of ages 3-12: A review and recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 4,

self-concept: A comprehensive review of 10 instruments. The School 657–692.

Counselor, 42, 14–33. James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology. New York: Holt.

Brown, J. D. (1993). Self-esteem and self-evaluation: Feeling is believing. Kaplan, H. B. (1975). Self-attitudes and deviant behavior. Pacific Palisades, CA:

In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self (pp. 27–58). Hillsdale, Goodyear Publications.

NJ: Erlbaum. Kaplan, L. (1995). Self-esteem is not our national wonder drug. The School

Bubenzer, D., Zimpfer, D., & Mahrle, C. (1990). Standardized individual Counselor, 42, 341–345.

appraisal in agency and private practice: A survey. Journal of Mental Keyser, D. J., & Sweetland, R. C. (Eds.). (1998). Test critiques (Vols. 1–4). Kansas

Health Counseling, 12, 51–66. City, MO: Test Corporation of America.

Chiu, L. (1988). Measures of self-esteem for school-age children. Jour- Leahy, R. L. (1985). The development of the self. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

nal of Counseling and Development, 66, 298–301. Lerner, B. (1985). Self-esteem and excellence: The choice and the paradox.

Conoley, J. C., & Impara, J. C. (Eds.). (1995). Mental measurements year- American Educator, 9, 10–16.

book (12th ed.). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska, Buros Mental London, T. (1997). The case against self-esteem: Alternate philosophies

Measurement Institute. toward self that would raise the probability of pleasurable and produc-

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: tive living. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy,

Scribner. 15, 19–29.

Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem. San Francisco: Marsh, H. W., & Richards, G. E. (1988). Tennessee Self-Concept Scale:

Freeman. Reliability, internal structure, and construct validity. Journal of Person-

Coopersmith, S. (1981). SEI: Self-Esteem Inventories. Palo Alto, CA: Con- ality and Social Psychology, 55, 612–624.

sulting Psychologists Press. Maslow, A. (1968). Toward a psychology of being (2nd ed.). New York:

Crandall, R. (1973). The measurement of self-esteem and related con- Van Nostrand.

structs. In J. P. Robinson & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Measures of social Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago

psychological attitudes (pp. 45–167). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for So- Press.

cial Research. Mecca, A., Smelser, N., & Vasconcellos, J. (Eds.). (1989). The social impor-

Demo, D. H. (1985). The measurement of self-esteem: Refining our tance of self-esteem. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

methods. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1490–1500. Mruk, C. (1995). Self-esteem: Research, theory, and practice. New York:

Fitts, W. H. (1972). The self-concept and behavior: Overview and supple- Springer.

ment. Nashville, TN: Counselor Recording and Testing. Mruk, C. (1999). Self-esteem: Research, theory, and practice (2nd ed.).

Fitts, W. H. , & Warren, W. L. (1998). Tennessee Self-Concept Scale, second New York: Springer.

edition. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. Murphy, L. L., Conoley, J. C., & Impara, J. C. (Eds.). (1994). Tests in print

Fleming, J. S., & Watts, W. A. (1980). The dimensionality of self-esteem: IV: An index to tests, test reviews, and the literature on specific tests (Vols.

Some results for a college sample. Journal of Personality and Social 1 & 2). Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press.

Psychology, 39, 921–929. Piers, E. V. (1984). Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale: Revised manual.

Fong, M. (1993). Teaching assessment and diagnosis within a DSM-III-R Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

framework. Counselor Education and Supervision, 32, 276–286. Pope, A., McHale, S., & Craighead, E. (1988). Self-esteem enhancement with chil-

Franzoi, S. L., & Shields, S. A. (1984). The Body-Esteem Scale: Multidi- dren and adolescents. New York: Pergamon Press.

mensional structure and sex differences in a college population. Jour- Pottebaum, S., Keith, T., & Ehly, S. (1986). Is there a causal relationship between

nal of Personality Assessment, 48, 173–178. self-concept and academic achievement? Journal of Educational Research,

Frey, D., & Carlock, C. (1989). Enhancing self-esteem. Muncie, IN: Accel- 79, 140–144.

erated Development, Inc. Ridley, C., Li, L., & Hill, C. (1998). Mulitcultural assessment: Reexamination,

Gecas, V. (1982). The self concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 8, 1–33. reconceptualization, and practical applications. The Counseling Psychologist,

Gecas, V. (1989). The social psychology of self-efficacy. Annual Review 26, 827–910

of Sociology, 15, 291–316. Robinson, J. P., Shaver, P. R., Wrightsman, L. S. (Eds.). (1991). Measures of

Ginter, E. J., & Dwinell, P. L. (1994). The importance of perceived dura- personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic

tion: Loneliness and its relationship to self-esteem and academic Press.

performance. Journal of College Student Development, 35, 456–460. Robson, P. J. (1988). Self-esteem: A psychiatric view. British Journal of

Giordano, F. G., Schwiebert, V., & Brotherton, W. (1997). School counselors’ Psychiatry, 153, 6–15.

perceptions of the usefulness of standardized tests, frequency of their use, Roid, G. H., & Fitts, W. H. (1988). Tennessee Self-Concept Scale: Revised

and assessment training needs. The School Counselor, 44, 198–205. manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Gladding, S. T. (2000). The counseling dictionary. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy. New York: Houghton-Mifflin.

Prentice Hall. Rogers, C. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality and interpersonal

Gurney, P. W. (1986). Self-esteem in the classroom. School Psychology relationships as developed in the client-centered framework. In S.

International, 7, 199–209. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of science: Vol. 3. Formulations of the

Hamilton, D. L. (1971). A comparative study of five methods of assess- person and the social context (pp. 184–256). New York: McGraw Hill.

ing self-esteem, dominance, and dogmatism. Educational and Psycho- Rokeach, M. (1979). Some unresolved issues in theories beliefs, atti-

logical Measurement, 31, 441–452. tudes, and values. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 27, 261–304.

Harter, S. (1985). Competence as a dimension of self-evaluation: To- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ:

ward a comprehensive model of self-worth. In R. L. Leahy (Ed.), The Princeton University Press.

development of the self (pp. 55–121). London: Academic. Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Harter, S. (1993). Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in chil- Rosenberg, M. (1985) Self-concept and psychological well-being in ado-

dren and adolescents. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Self-esteem: The puzzle lescence. In R. Leahy (Ed.), The development of the self (pp. 205–246).

of low self-regard (pp. 87–106). New York: Plenum. Orlando, Fl: Academic Press.

JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80 213

Guindon

Rosenberg, M., & Simmons, R. G. (1972). Black and White self-esteem: Street, S., & Isaacs, M. (1998). Self-esteem: Justifying its existence. Pro-

The urban school child. Washington, DC: American Sociological fessional School Counseling, 1, 46–50.

Association. Szymanski, J., & O’Donohue, W. (1995). Self-appraisal skills. In W. O’Donohue

Savin-Williams, R., & Jaquish, G. (1981). The assessment of adolescent self- & L. Krasner (Eds.), The handbook of psychological skills training: Clinical

esteem: A comparison of methods. Journal of Personality, 49, 324–336. techniques and applications (pp. 161–179). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Schwarz, N. (1999). Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. Tran, T. V., & O’Hare, T. (1996). Congruency between interviewers’ ratings

American Psychologist, 54, 93–105. and respondents’ self-reports of self-esteem, depression and health status.

Scott, C., Murray, G., Mertens, C., & Dustin, E. (1996). Student self-esteem Social Work Research, 20, 43–50.

and the school system: Perceptions and implications. The Journal of Edu- Vaac, N., & Juhnke, G. (1997). The use of structural clinical interviews for

cational Research, 89, 286–293. assessment in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75,

Secord, P. F., & Jourard, G. A. (1953). The appraisal of body-cathexis: Body- 470–480.

cathexis and the self. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 17, 342–347. Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition

Seligman, L. (1996). Diagnosis and treatment planning in counseling. New to experience negative emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96,

York: Plenum Press. 465–490.

Shavelson, R. J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: The Wells, L. E., & Marwell, G. (1976). Self-esteem: Its conceptualization and mea-

interplay of theory and methods. Journal of Educational Psychology, surement. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

74, 3–17. White, R. (1963). Ego and reality in psychoanalytic theory: A proposal regard-

Skaalvik, E. (1986). Sex differences in global self-esteem: A research review. ing independent ego energies. Psychological Issues, 3, 125–150.

Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 30, 167–179. Whitson, S. C. (1996). Accountability through action research: Research

Smelser, N. (1989). Self-esteem and social problems: An introduction. In methods for practitioners. Journal of Counseling & Development, 74,

A. M. Mecca, N. J. Smelser, & J. Vasconcellos (Eds.), The social impor- 616–623.

tance of self-esteem (pp. 294–326). Berkeley: University of California Witmer, J. M., & Sweeney, T. J. (1992). A holistic model for wellness and

Press. prevention over the life span. Journal of Counseling & Development, 71,

Sommers-Flanagan, J., & Sommers-Flanagan, R. (1998). Assessement 140–147.

and diagnosis of conduct disorder. Journal of Counseling & Develop- Wylie, R. C. (1974). A review of methodological considerations and measuring

ment, 76, 189–197. instruments: Vol. 1. The self-concept (Rev. ed.). Lincoln: The University of

Steenbarger, B., & Smith, H. (1996). Assessing the quality of counseling Nebraska Press.

services: Developing accountable helping systems. Journal of Counsel- Ziller, R. (1969). The alienation syndrome: A triadic pattern of self-other

ing & Development, 75, 145–150. orientation. Sociometry, 15, 87–93.

214 JOURNAL OF COUNSELING & DEVELOPMENT • SPRING 2002 • VOLUME 80

You might also like

- Matrix of Career Development TheoriesDocument12 pagesMatrix of Career Development TheoriesRyan Michael Oducado95% (21)

- Emotional & PerfectionismDocument6 pagesEmotional & PerfectionismEirini Pantelidi100% (1)

- Tharenou 1979Document31 pagesTharenou 1979Muhammad AzeemNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document20 pagesUnit 3SHUBHANGEE SINGHNo ratings yet

- The Potential Use of The Authenticity SCDocument10 pagesThe Potential Use of The Authenticity SCVeraloeNo ratings yet

- Reference Groups Research Paper Ref.Document5 pagesReference Groups Research Paper Ref.HIDDEN Life OF 【शैलेष】No ratings yet

- Snyder 2006Document14 pagesSnyder 2006uricomasNo ratings yet

- Organization-Based Self-Esteem: Construct Definition, MeasurementDocument27 pagesOrganization-Based Self-Esteem: Construct Definition, MeasurementMuhammad AzeemNo ratings yet

- Gnambs 2017 BDocument15 pagesGnambs 2017 BAnnieNo ratings yet

- Teori Behavior Dan Humanistik Dan KognitifDocument10 pagesTeori Behavior Dan Humanistik Dan KognitifTai Thau ChunNo ratings yet

- Practical Application of Self Psychology in CounselingDocument21 pagesPractical Application of Self Psychology in CounselingAaron DayNo ratings yet

- Five Factor ModelDocument13 pagesFive Factor ModelNasNo ratings yet

- KPI Career Development Counseling Overview PaperDocument8 pagesKPI Career Development Counseling Overview PapertlourencoshiberNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Model of TrustDocument12 pagesAn Integrative Model of TrustRoxy Shira AdiNo ratings yet

- 12 - Heatheron - Assesin Self-EsteemDocument15 pages12 - Heatheron - Assesin Self-Esteemhellonewwork8No ratings yet

- Role of Attitude in Multicultural Counseling - Minami (2009)Document8 pagesRole of Attitude in Multicultural Counseling - Minami (2009)xiejie22590No ratings yet

- Hughes 1984Document36 pagesHughes 1984Lam KyuNo ratings yet

- Beliefs and Evaluations About Counseling Services ScaleDocument19 pagesBeliefs and Evaluations About Counseling Services ScaleCitra WahyuniNo ratings yet

- What Is Trust? A Conceptual Analysis and An Interdisciplinary ModelDocument8 pagesWhat Is Trust? A Conceptual Analysis and An Interdisciplinary ModelPlm Pamantasan IINo ratings yet

- 1 Teori Konseling Karir (L)Document37 pages1 Teori Konseling Karir (L)Tisa KhaerunisaNo ratings yet

- David H. Demo: The Measurement of Self-Esteem: Refining Our MethodsDocument15 pagesDavid H. Demo: The Measurement of Self-Esteem: Refining Our MethodsWan Ayuni Wan SalimNo ratings yet

- COUNSELLLIINNGGGGDocument6 pagesCOUNSELLLIINNGGGGAnne GarciaNo ratings yet

- Paper 1 OB Sheet 1Document8 pagesPaper 1 OB Sheet 1jivetaaaNo ratings yet

- The History & Tranditions of Clinical SupervisionDocument64 pagesThe History & Tranditions of Clinical SupervisionMerlinkevinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Series On Motivational Interviewing and PsychotherapyDocument7 pagesIntroduction To The Special Series On Motivational Interviewing and PsychotherapyShabila ShamsaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Two Social Interest Assessment Instruments With Implications For Managed CareDocument11 pagesA Comparison of Two Social Interest Assessment Instruments With Implications For Managed CareRafael OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Fiedler ModelDocument23 pagesFiedler ModelDiego MendozaNo ratings yet

- Week 4 Hopwood An Interpersonal Perspective On The Personality Assessment ProcessDocument10 pagesWeek 4 Hopwood An Interpersonal Perspective On The Personality Assessment ProcesslejlaroosmujagicNo ratings yet

- Pattern Identification Exercise. ERIC Digest.: Got It!Document15 pagesPattern Identification Exercise. ERIC Digest.: Got It!Ioana DragneNo ratings yet

- Loyalty: A Customer's Perspective: TH THDocument9 pagesLoyalty: A Customer's Perspective: TH THEmaNo ratings yet

- Basics of CounsellingDocument20 pagesBasics of CounsellinggeorgeNo ratings yet

- PSY1021 Essay 1 - Inderpreet Kaur (M00984168)Document11 pagesPSY1021 Essay 1 - Inderpreet Kaur (M00984168)InsanekaurNo ratings yet

- Personality Measurement and Employment DecisionsDocument21 pagesPersonality Measurement and Employment DecisionsJosiah KingNo ratings yet

- Organization-Based Self-Esteem Construct Definition, Measurement, and ValidationDocument28 pagesOrganization-Based Self-Esteem Construct Definition, Measurement, and ValidationHuong HoangNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3-ReportDocument10 pagesAssignment 3-ReportDavid GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Criteria of Nonacademic Characteristics Used To Evaluate and Retain Community Counseling StudentsDocument11 pagesCriteria of Nonacademic Characteristics Used To Evaluate and Retain Community Counseling StudentsrgrockersNo ratings yet

- Motivational InterviewingDocument13 pagesMotivational Interviewingapi-548625849No ratings yet

- The Transformation of Community Counseling For 2015 and Beyond - Article - 75Document12 pagesThe Transformation of Community Counseling For 2015 and Beyond - Article - 75rajaidaNo ratings yet

- New Work AttitudesDocument14 pagesNew Work AttitudesSDM Kantor PusatNo ratings yet

- Motivational Interviewing: A Theoretical Framework For The Study of Human Behavior and The Social EnvironmentDocument10 pagesMotivational Interviewing: A Theoretical Framework For The Study of Human Behavior and The Social Environmentkatherine stuart van wormer100% (6)

- Skills of A CounselorDocument12 pagesSkills of A CounselorDinesh Cidoc100% (3)

- Journal of Vocational Behavior: John P. Meyer, Alexandre J.S. Morin, Christian VandenbergheDocument17 pagesJournal of Vocational Behavior: John P. Meyer, Alexandre J.S. Morin, Christian VandenberghePadmo PadmundonoNo ratings yet

- Psychology Self - EsteemDocument15 pagesPsychology Self - Esteemmebz13100% (1)

- The DimensionsDocument3 pagesThe DimensionsWilliam SanjayaNo ratings yet

- R01 - Baldwin 1987 - Salient Private Audiences & Awareness of The SelfDocument12 pagesR01 - Baldwin 1987 - Salient Private Audiences & Awareness of The SelfGrupa5No ratings yet

- Innovations in Career CounselingDocument10 pagesInnovations in Career CounselingtrinoaparicioNo ratings yet

- DBR v18n1fDocument12 pagesDBR v18n1fsourabhzende672No ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: A A B C A A A DDocument7 pagesPsychiatry Research: A A B C A A A DArif IrpanNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument8 pages1 PBdharsha_naa2514No ratings yet

- Espouse and Theories in Use Social WorkersDocument10 pagesEspouse and Theories in Use Social WorkersNGQNo ratings yet

- 2011 Oustanding AFCPE Conference Paper: Development and Validation of A Financial Self-Efficacy ScaleDocument10 pages2011 Oustanding AFCPE Conference Paper: Development and Validation of A Financial Self-Efficacy ScaleEmiliyana SoejitnoNo ratings yet

- Hope Therapy PDFDocument18 pagesHope Therapy PDFalexNo ratings yet

- Assessing Personality With A Structured Employment InterviewDocument17 pagesAssessing Personality With A Structured Employment InterviewCarolina GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- IJP 2018 22 3 5 WatkinsDocument12 pagesIJP 2018 22 3 5 Watkinsv_azygosNo ratings yet

- Castillon&Ceneta Week12Document6 pagesCastillon&Ceneta Week12adrianceneta12No ratings yet

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of Business EthicsDocument16 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of Business Ethicsrei377No ratings yet

- ROSEEEEEEEEEEDocument6 pagesROSEEEEEEEEEEAkshi chauhanNo ratings yet

- Working with Assumptions in International Development Program Evaluation: With a Foreword by Michael BambergerFrom EverandWorking with Assumptions in International Development Program Evaluation: With a Foreword by Michael BambergerNo ratings yet

- Handbook for Strategic HR - Section 3: Use of Self as an Instrument of ChangeFrom EverandHandbook for Strategic HR - Section 3: Use of Self as an Instrument of ChangeNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Motivational Interviewing for Mental Health Clinicians: A Practical Guide to Empowering Change in Mental Health CareFrom EverandIntroduction to Motivational Interviewing for Mental Health Clinicians: A Practical Guide to Empowering Change in Mental Health CareNo ratings yet

- Weekly Statistics On Anti-Carnapping OperationsDocument2 pagesWeekly Statistics On Anti-Carnapping OperationsnestorlatapNo ratings yet

- Problem 1: Solution Guide - Requirement 1Document4 pagesProblem 1: Solution Guide - Requirement 1Lerma MarianoNo ratings yet

- Full Case Aug 10 CreditDocument54 pagesFull Case Aug 10 CreditCesyl Patricia BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Behavioral SegmentationDocument4 pagesBehavioral SegmentationWaseel sultanNo ratings yet

- AC13 Accenture & The Hartford - Elicitation PDFDocument14 pagesAC13 Accenture & The Hartford - Elicitation PDFsonnyNo ratings yet

- WEEK 3 Models and Frameworks For Total Quality ManagementDocument14 pagesWEEK 3 Models and Frameworks For Total Quality Managementuser 123No ratings yet

- Percentage QuestionsDocument8 pagesPercentage Questionspavankumarannepu04No ratings yet

- Ad Astra, Vol. 32.2 (Spring 2020)Document68 pagesAd Astra, Vol. 32.2 (Spring 2020)Ano NimusNo ratings yet

- Cathay Pacific Airways, Ltd. v. Court of AppealsDocument8 pagesCathay Pacific Airways, Ltd. v. Court of AppealsriaheartsNo ratings yet

- Agreement On AgricultureDocument11 pagesAgreement On AgricultureUjjwal PrakashNo ratings yet

- Prelim Group DynamicsDocument15 pagesPrelim Group DynamicsMay MendozaNo ratings yet

- Culturally Responsive Teaching-Schools - FinalDocument29 pagesCulturally Responsive Teaching-Schools - Finalhana auxilioNo ratings yet

- Prac.U1 3.ML - Pre - List - Reading PDF Automation Employment 2Document1 pagePrac.U1 3.ML - Pre - List - Reading PDF Automation Employment 2oguztmNo ratings yet

- A Conversation With Jonathan Haidt - Minding The CampusDocument44 pagesA Conversation With Jonathan Haidt - Minding The CampusAive5ievNo ratings yet

- Project Report Group Housing Near Dwarka More Metro Station New DelhiDocument7 pagesProject Report Group Housing Near Dwarka More Metro Station New DelhiAlok SinghNo ratings yet

- Job Description - Knowledge Management ManagerDocument4 pagesJob Description - Knowledge Management ManagerRajeshNo ratings yet

- ALLISON - The New Spheres of InfluenceDocument12 pagesALLISON - The New Spheres of InfluenceDaniel GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Frankenstein and Blade Runner Exam Notes: Analysing MoviesDocument3 pagesFrankenstein and Blade Runner Exam Notes: Analysing MoviesSam SmithNo ratings yet

- Coerced Confessions The Discourse of Bilingual Pol... - (PG 13 - 122)Document110 pagesCoerced Confessions The Discourse of Bilingual Pol... - (PG 13 - 122)maria_alvrzdNo ratings yet

- Mirasol vs. DPWH (Equal Protection Clause)Document1 pageMirasol vs. DPWH (Equal Protection Clause)Roselyn DanglacruzNo ratings yet

- Ria Paper Format 2020Document11 pagesRia Paper Format 2020mrunmayee parkheNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Certificate of Zoning Compliance-Revised by TSA-Sept 4, 2020 PDFDocument1 pageApplication Form For Certificate of Zoning Compliance-Revised by TSA-Sept 4, 2020 PDFMark Gregory Rimando100% (1)

- Office of The OmbudsmanDocument6 pagesOffice of The OmbudsmantintyiNo ratings yet

- Matrixial Subjectivity Aesthetics Ethics Vol 1 1990 2000 Bracha L Ettinger Download PDF ChapterDocument35 pagesMatrixial Subjectivity Aesthetics Ethics Vol 1 1990 2000 Bracha L Ettinger Download PDF Chaptercharmaine.charles779100% (15)

- Affidavit of Non ImprovementDocument1 pageAffidavit of Non Improvementnagelyn mejiaNo ratings yet

- Zervos MotionDocument17 pagesZervos MotionLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet