Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Davar MAKINGFATEHPURSKR 1975

Davar MAKINGFATEHPURSKR 1975

Uploaded by

Vedika DixitCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Mohenjo - Daro and The Indus Valley Civilization1922-1927 Vol IDocument423 pagesMohenjo - Daro and The Indus Valley Civilization1922-1927 Vol Iaravindaero123100% (4)

- Technique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaDocument3 pagesTechnique of Wood Work - Some References in Ancient IndiaCharlie HigginsNo ratings yet

- John Irwin - The True Chronology of Aśokan PillarsDocument20 pagesJohn Irwin - The True Chronology of Aśokan PillarsManas100% (1)

- Harappan Art SankaliaDocument6 pagesHarappan Art SankaliaNeha AnandNo ratings yet

- Bidar Its HistoryDocument519 pagesBidar Its HistoryMohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, IndiaNo ratings yet

- Vidyadharnagar Doshi PDFDocument23 pagesVidyadharnagar Doshi PDFMananshNo ratings yet

- A190XINFODocument3 pagesA190XINFOShrey KalathiyaNo ratings yet

- Ancient HistoryDocument52 pagesAncient HistoryVandanaNo ratings yet

- Mookerjee INDIANART 1954Document7 pagesMookerjee INDIANART 1954arambh022-23No ratings yet

- Socio-Cultural Life in Medieval Badayun (1206-1605) : ThesisDocument305 pagesSocio-Cultural Life in Medieval Badayun (1206-1605) : Thesispatan7246No ratings yet

- Carpet HistoryDocument9 pagesCarpet Historysakshi_mehra123No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 47.31.73.96 On Thu, 23 Jul 2020 17:43:10 UTCDocument4 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 47.31.73.96 On Thu, 23 Jul 2020 17:43:10 UTCShivatva BeniwalNo ratings yet

- Prehistoric IndiaDocument312 pagesPrehistoric IndiaSriramoju HaragopalNo ratings yet

- Kamasutra of VatsyanaDocument216 pagesKamasutra of VatsyanaSongs TrendsettersNo ratings yet

- Erido-LowDocument376 pagesErido-LowJavier Martinez Espuña100% (1)

- Takayanagi - The Glory That Was AzuchiDocument13 pagesTakayanagi - The Glory That Was AzuchibloumerNo ratings yet

- (Sir William Meyer Lectures) K. N. Dikshit - Prehistoric Civilization of The Indus Valley-Indus Publications (1988)Document87 pages(Sir William Meyer Lectures) K. N. Dikshit - Prehistoric Civilization of The Indus Valley-Indus Publications (1988)Avni ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Vision of Vincent Van Gogh and Maurice Utrillo in Landscape Paintings and Their Impact in Establishing The Identity of The PlaceDocument16 pagesVision of Vincent Van Gogh and Maurice Utrillo in Landscape Paintings and Their Impact in Establishing The Identity of The PlaceIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- 4 Surat and BombayDocument25 pages4 Surat and Bombayvaishalitadvi053No ratings yet

- Upinder Singh (Editor), Parul Pandya Dhar (Editor) - Asian Encounters - Exploring Connected Histories-Oxford University Press (2014)Document262 pagesUpinder Singh (Editor), Parul Pandya Dhar (Editor) - Asian Encounters - Exploring Connected Histories-Oxford University Press (2014)meghaNo ratings yet

- The Achaemenid Concept of KingshipDocument6 pagesThe Achaemenid Concept of KingshipAmir Ardalan EmamiNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley CivilisationDocument13 pagesIndus Valley CivilisationshavyNo ratings yet

- Description of Syria, Including Palestine - Translated by Le StrangeDocument156 pagesDescription of Syria, Including Palestine - Translated by Le StrangeHeX765No ratings yet

- 1938 The Land of ShebaDocument30 pages1938 The Land of Shebanorris.jeromeNo ratings yet

- Pursuing The History of Tech Irfan HabibDocument23 pagesPursuing The History of Tech Irfan HabibMuni Vijay ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Traditional Crafts of Saudi ArabiaDocument5 pagesTraditional Crafts of Saudi Arabialonnnet7380No ratings yet

- Suyav Bakhshis Creative Activity and Its Role in The Development of Khorezm Folk Tale TraditionsDocument3 pagesSuyav Bakhshis Creative Activity and Its Role in The Development of Khorezm Folk Tale TraditionsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Indian Merchants and The Western Indian Ocean The Early Seventeenth CenturyDocument20 pagesIndian Merchants and The Western Indian Ocean The Early Seventeenth CenturyGaurav AgrawalNo ratings yet

- ASI Replica Museum Needs Reprieve South AsiaDocument2 pagesASI Replica Museum Needs Reprieve South AsiaGayatri KathayatNo ratings yet

- Various - Ancient India PDFDocument193 pagesVarious - Ancient India PDFraahul_nNo ratings yet

- 75182c1da7e02a41fbfe56d300d2def5Document192 pages75182c1da7e02a41fbfe56d300d2def5Asmaa AyadNo ratings yet

- Art in OrissaDocument19 pagesArt in Orissaayeeta5099No ratings yet

- Art Integrated Project - ScienceDocument10 pagesArt Integrated Project - SciencePavani KumariNo ratings yet

- Dhyansky 1987 Indus Origin YogaDocument21 pagesDhyansky 1987 Indus Origin Yogaalastier100% (1)

- History of Indian and Eastern Architecture Vol 1Document522 pagesHistory of Indian and Eastern Architecture Vol 1sudipto917No ratings yet

- Fatehpur Sikri - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesFatehpur Sikri - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaKaustubh Sohoni0% (1)

- Kumar Delhi PastsDocument74 pagesKumar Delhi Pastssaisurabhigupta3No ratings yet

- The Kama Sutra of VatsyayanaDocument216 pagesThe Kama Sutra of VatsyayanaJonathan MannNo ratings yet

- Searching For Ancient ArabiaDocument37 pagesSearching For Ancient Arabiareza32393No ratings yet

- Architecture, Art & CraftDocument107 pagesArchitecture, Art & CraftJas MineNo ratings yet

- Cesare JDH42015 Historyof Design ReviewDocument4 pagesCesare JDH42015 Historyof Design ReviewSir Jc MatienzoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Indus ValleyDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Indus Valleyaflbtjglu100% (1)

- Leisure Gardens Secular Habits The Culture of RecrDocument15 pagesLeisure Gardens Secular Habits The Culture of RecrNikola PantićNo ratings yet

- Devahuti MAURYANARTEPISODE 1971Document14 pagesDevahuti MAURYANARTEPISODE 1971shivamkumarbth8298No ratings yet

- African ArchitectureDocument25 pagesAfrican ArchitectureChitundu ChitunduNo ratings yet

- Walls of Tammīs ADocument26 pagesWalls of Tammīs ASeyed Pedram Refaei SaeediNo ratings yet

- Presentation Sheth Final PDFDocument1 pagePresentation Sheth Final PDFNiharika ModiNo ratings yet

- Windcatchersofmedievalcairopartonesept2020 PDFDocument758 pagesWindcatchersofmedievalcairopartonesept2020 PDFAhmad AmrNo ratings yet

- MS LA 25 Profile Mohammad ShaheerDocument4 pagesMS LA 25 Profile Mohammad ShaheerSaurabh PokarnaNo ratings yet

- Twentieth-Century Myth-Making - Persian Tribal RugsDocument13 pagesTwentieth-Century Myth-Making - Persian Tribal Rugsm_s6254926No ratings yet

- Bengalinsixteent 00 DasguoftDocument204 pagesBengalinsixteent 00 DasguoftNirmalya Dasgupta100% (1)

- Indian Architect U 00 Have U of TDocument542 pagesIndian Architect U 00 Have U of TManvendra NigamNo ratings yet

- Rifat ChadirjiDocument3 pagesRifat ChadirjiallawicomicsNo ratings yet

- 5675raymond V. SchoderDocument13 pages5675raymond V. SchoderRodrigoNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Mirror Embroidery in Two Villages of Sanghar SindhDocument7 pagesEvolution of Mirror Embroidery in Two Villages of Sanghar Sindhprachi gargNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Ancient Civilizations Indus Valley Civilization: StructureDocument7 pagesUnit 5 Ancient Civilizations Indus Valley Civilization: StructureAmity NoidaNo ratings yet

- Indian Architecture LibreDocument27 pagesIndian Architecture LibreStephen.KNo ratings yet

- Jahangir Article PDFDocument38 pagesJahangir Article PDFsfaiz87No ratings yet

- History: Babur and Humayun (1526-1556)Document2 pagesHistory: Babur and Humayun (1526-1556)Ajit JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Andrew Marr's HistoryDocument5 pagesAndrew Marr's HistoryRubab SohailNo ratings yet

- Islamic EmpiresDocument7 pagesIslamic Empireselppa284No ratings yet

- Architecture of Bengal OVERALL HISTORYDocument114 pagesArchitecture of Bengal OVERALL HISTORYSreyashi ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3-War of Independence-Handouts PDFDocument5 pagesChapter 3-War of Independence-Handouts PDFDua MerchantNo ratings yet

- Bengal Under The MughalDocument4 pagesBengal Under The MughalAyesha Rahman MomoNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Mughal Book of War: A Translation and Analysis of Abu'l-Fazl'sDocument133 pagesUnderstanding The Mughal Book of War: A Translation and Analysis of Abu'l-Fazl'sHaris QureshiNo ratings yet

- Journal of South Asian Studies: Reimagining The Mughal Emperors Akbar and Aurangzeb in The 21 CenturyDocument9 pagesJournal of South Asian Studies: Reimagining The Mughal Emperors Akbar and Aurangzeb in The 21 CenturyMubashir AhmedNo ratings yet

- Historian's DisputeDocument169 pagesHistorian's DisputeSanghaarHussainTheboNo ratings yet

- 3167 10071 2 PB PDFDocument13 pages3167 10071 2 PB PDFarparagNo ratings yet

- Aquil, Raziuddin - The Muslim Question - Understanding Islam and Indian History-Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd. - Penguin Books (2017)Document363 pagesAquil, Raziuddin - The Muslim Question - Understanding Islam and Indian History-Random House Publishers India Pvt. Ltd. - Penguin Books (2017)KritikaNo ratings yet

- Fortune Ias Academy: Paper - I InstructionsDocument16 pagesFortune Ias Academy: Paper - I InstructionsShubhamNo ratings yet

- Historical Development of English in IndiaDocument9 pagesHistorical Development of English in IndiaDaffodils100% (1)

- Sonal Singh - Grant of DiwaniDocument12 pagesSonal Singh - Grant of DiwaniZoya NawshadNo ratings yet

- Late Mughal Architecture PDFDocument13 pagesLate Mughal Architecture PDFMansi GuptaNo ratings yet

- 7TH Social-2Document88 pages7TH Social-2satyadevi gandepalliNo ratings yet

- Pak. St. Notes. 1857 1947 2 AutosavedDocument134 pagesPak. St. Notes. 1857 1947 2 Autosavedhifza anwarNo ratings yet

- 50 Years of The Agrarian System of Mughal IndiaDocument9 pages50 Years of The Agrarian System of Mughal IndiaNitu KundraNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument34 pages07 - Chapter 1 PDFTahir MubarakNo ratings yet

- Khyber PassDocument3 pagesKhyber PasskdvprasadNo ratings yet

- ++history BYJU Notes PDFDocument97 pages++history BYJU Notes PDFDebashishRoy100% (1)

- Gs Mentor SyllabusDocument31 pagesGs Mentor SyllabusCecil ThompsonNo ratings yet

- Attachment Decline of Mughals 2nd Lecture Lyst6837Document27 pagesAttachment Decline of Mughals 2nd Lecture Lyst6837Rohit AroraNo ratings yet

- Jasmine and Coconuts - South Indian Tales-Libraries Unlimited (1999)Document139 pagesJasmine and Coconuts - South Indian Tales-Libraries Unlimited (1999)Priya SeshadriNo ratings yet

- Contemporary India:An Overview: Class Notes: Unit 1 (Bajmc103)Document87 pagesContemporary India:An Overview: Class Notes: Unit 1 (Bajmc103)Srishti MishraNo ratings yet

- NCERT-Books11-for-class 7-Social-Science-History-Chapter 4Document15 pagesNCERT-Books11-for-class 7-Social-Science-History-Chapter 4Syed Kashif HasanNo ratings yet

- Indian History: Ancient India (Pre-Historic To AD 700)Document4 pagesIndian History: Ancient India (Pre-Historic To AD 700)Alex Andrews GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Article-P143 12Document2 pagesArticle-P143 12AJITHA SNo ratings yet

- Ancient India - Time Period & EventsDocument4 pagesAncient India - Time Period & EventsManish KumarNo ratings yet

Davar MAKINGFATEHPURSKR 1975

Davar MAKINGFATEHPURSKR 1975

Uploaded by

Vedika DixitOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Davar MAKINGFATEHPURSKR 1975

Davar MAKINGFATEHPURSKR 1975

Uploaded by

Vedika DixitCopyright:

Available Formats

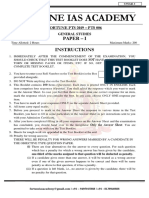

THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SĪKRĪ

Author(s): Satish K. Davar

Source: Journal of the Royal Society of Arts , NOVEMBER 1975, Vol. 123, No. 5232

(NOVEMBER 1975), pp. 781-805

Published by: Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and

Commerce

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41372237

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce is collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Royal Society of Arts

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE MAKING OF

FATEHPUR SÏKRÏ

I The Sir George Birdwood Memorial Lec

I Satish K. Davor , BA, В Archy MRP , A

delivered to the Commonwealth Section of the Society

on Tuesday y 29th April > J97 5 5 with Sir James Richards ,

СБЕ, ARI В Ay in the Chair

The Chairman: Our speaker this evening is architect, a planner and a historian, and when

Mr. Satish K. Davar, who is going to talk about the book he is preparing on the city is published

the remarkable story of Fatehpur Sikri, which we shall know a great deal more about how the

was built by that great patron of the arts, the city was designed and built. He is going to tell

Mughal Emperor Akbar, in the latter part of the us this evening about the progress of his re-

sixteenth century. It was only occupied as the searches at Fatehpur Sikri and the conclusions

administrative capital of Akbar's empire for that he has drawn from them.

fifteen years, after which it was deserted ; and it This series of annual lectures was founded as

has remained deserted ever since, that is for far back as 1920 in memory of Sir George

nearly four centuries. The central parts of the Birdwood, who lived from 1830 to 19 17. He was

city, however, are still in a wonderful state of a great authority on Indian art and design, was

preservation which has made Fatehpur Sikri one a voluminous writer, a scholar and an enthusi-

of the most admired architectural monuments in ast. He was also a Member of the Council of this

India. It is visited by thousands of people bothSociety for over twenty years and did much to

for its beauty and for its fascinating combination

bring the arts of India within its purview. Past

of Mughal, Räjpüt and Persian styles of architec-

Birdwood Lectures have dealt with a fascinating

ture. I emphasize that it is the central partsrange

of of Indian subjects. I have been told only

the city that are so remarkably preserved. These

this evening, incidentally, that the Chairman at

are what the visitors explore. But within the the first Birdwood Lecture was none other than

enclosing walls there are acres more that are still

Lord Curzon, which makes me very proud to be

in ruins or of which traces only remain, andsitting

it in the same place! I am sure Mr. Satish

has been Mr. Satish Davar's task during the past

Davar will give a lecture that Birdwood himself

six years or more to investigate and identify would have valued.

these less known parts of the city. He is an

The following lecture , which was illustrated , was then delivered.

the scattered ruins of Fatehpur Sikri with

a keen personal interest in Fatehpur groups of student architects from Delhi

May a Sikri, keen I first

Sikri,forfor personal

taking thethank

chair taking

to-day, interest Sir the James, chair in Fatehpur who to-day, has School was a stimulating experience which

and then express my pleasure and gratitude eventually led me to undertake fairly exten-

to the Royal Society of Arts for asking me sive site surveys over five winters in order to

to present this Sir George Birdwood reconstruct (on paper) this vast area which

Memorial Lecture. It was indeed an honour was neglected and unrecorded so far. The

to accept this opportunity to speak on a site evidence thus obtained, historical

topic which has been of absorbing interest records of the period and a comparative study

to me for a fairly long time. Looking around of other contemporary cities, enable us to

781

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 1975

Figure i. View through Buland Darwãzã leading to the wh

marble Chishtï tomb in the Jãmi Masjid courtyard

experience, interpret and analyse country, Fatehpur

with its lofty southern gate and a

Sïkrï as a living city of Mughal gem-likeIndia.

miniatureThese

marble tomb for the

site explorations, besides providing Chishtï saint, ais work-

a fascinating complex; and

ing base, reveal the enormous most development

of the visitors end their visit to the

potential of this area for educational, monuments here.

archaeological and tourism purposes. At the To comprehend Fatehpur Sïkrï as a city

same time they make me acutely aware of we should look beyond this tourist's com-

the rapid deterioration of these monuments plex, even beyond the Sïkrï of the Archae-

and the surrounding ruins, taking place ological Survey, and look at Akbar's city in

constantly, at all levels, due to official and

its entirety in a conceptual way to ascertain

public indifference. I am extremely con- if any ground rules, traditional practices,

cerned about this thoughtless unmaking of topographical considerations or special cir-

Fatehpur Sïkrï, which unfortunately seems cumstances, are manifest in this sixteenth-

like an irreversible process. century town layout. Architecture and town

It was a little over 400 years ago, whenlayouts are closely related arts and it is per-

Michelangelo was busy working on his plans haps a fair assumption that one cánnot have

for St. Peter's in Rome, that the third beautiful building complexes in a badly

Mughal Emperor Akbar - a contemporaryconsidered town layout. No work of art that

of Queen Elizabeth I of England - decidedhas stood the test of time is a product of

chance or accident, much less a designed

to build a new city for his court and residence

near Ägrä in India. Its splendid palaces with city, which is a synthesis of many skills,

their sunken gardens, multi-storied pleasure enormous teamwork, indigenous influences,

pavilions, and various courts for public and, it is to be hoped, an overriding inspira-

appearance and state work are known for tion. A city is the largest visual manifestation

their exquisite elegance and an intensely of man as an individual and as a communal

individual architectural character. The ad- being.

joining Jãmi-Masjid, one of the largest in the Fatehpur Sïkrï, according to Ralph

782

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

Fitch1 - one of the British merchants at resources, it readily assimilated the personal

and emotional responses of its founder.

Akbar's court - was among the largest cities

of the world at that time. Here, as we know, Having lost a few children in infancy, an

were concentrated the arts of India in a anxious Akbar visited several shrines and

cosmopolitan setting under one of the holy men where he offered prayers and

great-

est and most humane brains in Indian sought blessings for the birth of an heir and

history. A palace citadel was built and a successor to the throne. Amongst the Muslim

metropolitan city planned in less than a divines of that time was Salim Chishtl,3 who

decade. The speed of construction, men- had recently returned to his unassuming

tioned in several contemporary accounts, hermitage on the Sïkrï hill after a consider-

meant numerous groups of builders and able absence. He was a well-travelled man,

artisans working on separate projects rising and had made more than twenty pilgrimages

àt the same time.2 The situation can be quite to Mecca, most of them on foot. His spread-

chaotic without an overall concept and ing fame brought Akbar barefooted to his

specific guidelines for the entire area. Whatdoor. It was the spell of the octagenarian

were those guidelines? What was the con- saint's personality, or his prophecy that

cept or the art process ? Here, we venture toAkbar would have three sons, that comforted

participate in that art process, which by Akbar's troubled mind, The impact was

revealing itself would perhaps augment the immediate. A few royal palaces were

art product. This is an inquiry into the hurriedly constructed adjoining the Shaikh's

mental anticipation of a combination of house as Akbar decided to reside on Sïkrï

means to achieve this end product. hill. The decision to build an entire city on

Fatehpur Sïkrï was a vigorous city, a the spot and to move the court there per-

product of exceptional circumstances. De- manently, followed a year later.

signed from scratch and speedily built, Akbar's passion for building was insati-

utilizing all available talent and unlimited able. Despite the fact that he had already

Figure 2. Akbar's Day Palace ( popularly known as Turkish

Sultana's house ) and the decorative water tank

783

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 1975

started work on the Lãhore and wide moats

Agra all forts,

around. City plans were based

Akbar also began building the city of on concentric circles, but Sïkrï was different.

Fatehpur, which eventually became the It was an open city. Since the usual fortifi-

greatest of all his architectural projects. And cations were dispensed with, a new civic

yet in less than fifteen years, when Akbar relationship developed between the town

moved his court to Lãhore, the city was to and the hill-top palaces. The influence of

be totally abandoned, to the point that fine buildings was skilfully radiated out-

travellers would find it unsafe to go through it. wards, thereby articulating the whole fabric

Several factors make Sïkrï unique. First, of the city.

its spiritual origin is the most significant. Among other things, architecture is

The humble cave of Salïm Chishtï became defined as a 'place prepared in time and

a key point in the town concept. Secondly, space for human activity'. This definition

the enormous speed of its construction can be stretched to town design as well and

helped to maintain the mood. Thirdly, the no doubt time and space are its two essential

comparatively open plan of the city because aspects besides the various human episodes

of Chishtï's influence on the king. Fourthly, and historical events that it gradually assi-

the complex and extraordinary personality milates. In this context it would be appro-

of young Akbar. Finally, its short life-span, priate at this stage to consider the 'moment'

which was responsible for the preservation and 'site' as the two coordinates of the

of its theme and character. situation: the moment being its dynamic

Few cities in the world have been built aspect, its symbolical projection in time. The

with such impulse and rapidity. The site is static, a fundamental geopolitical

whole

fabric of the city was woven around the proposition. The 'site' at Sïkrï was a barren

physical and spiritual presence of the saint rocky escarpment about 100 to 150 feet

Salïm Chishtï. Many important roads and above ground level, forming part of the

streets of Sïkrï radiating from the centre set upper Vindhyan range that extends in a

the town pattern (Figure 27). Since the south-westerly direction for about two miles.

Chishtï presence drew a large number of To the north-west of this ridge lies the wide

pilgrims from distant parts of the country and shallow valley of the Khãri river,

to the little cave, the footpaths which thusbounded on the other side by the low ranges

developed eventually became the major of the Bandrâulï hills. On this ridge, a little

roadways for the royal passage. over a mile from Akbar's town, stood an old

Most cities are works of many generations, Räjpüt citadel held by the Sïkarwâr Räjpüts

each adding its own themes and new areas, for several centuries. It was the Sïkarwârs

frequently replacing the old. Many styles can who gave the place its name Sïkrï. One can

be seen side by side in most cities, depictingstill see the last remains of their palaces on

the different stages of their growth. But the hill.4 Their town spread towards the

Sïkrï is the work of one man, in a single north and north-east of the ridge in the

phase of his life. It was built with great direction of the present Bharatpur Road.

energy while the mood lasted and completely From the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries,

abandoned soon after. It is a frozen moment Sïkrï was somewhat of a frontier station,

in history. Its modest chambers, activated

feeling the pressure exerted by the Turks and

Pathãns from the north and that of the

corridors and open terraces reflect that mood.

What comes through with startling clarity Räjpüts from the neighbouring states in the

is the active and keen mind of Akbar, hissouth. The lurking tension in the area made

immense ambitions, intellectual subtlety,it strategically important and gave it a cer-

exquisite taste, and the sense, the drama,tain of political significance. Even after Agra

royalty. Each building reveals his imaginativebecame a Lodi Capital in the beginning of

and inventive genius. The growth of the the sixteenth century, Sïkrï maintained its

town reflects the growth of Akbar' s mind, significance as a military gathering point.

whose horizons were widening even faster A quarter of a century later, Bãbur,

than the boundaries of his expanding empire. the first Mughal - Akbar's grandfather -

Akbar was discovering himself. He was defeated the last Lodi king near Delhi,

discovering the people and the country pushed on to Agrã and later encamped at

around him, and was interested in distant Sïkrï to meet the united Räjpüt forces under

parts of the world as well. the formidable leadership of Rãnã Sãngã of

In most cities of that period, palaces wereMewãr. That was an anxious moment for the

kept walled in, separated from the town byMughals. The country around Agrä was in

784

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

Figure 3. Site characteristics

open revolt. Bãbur himself at Agrã. Abundance

hasof goodrecorded5

red sandstone,

that the heat was unusually ranging from roseoppressive.

pink to deep purple, so His

soldiers longed for the cool air of Kabul. near the site must have been a boon. Stone-

Even his best generals were eager to return cutting was perhaps the oldest and largest

home. Bãbur spent three or four weeks at trade in this region. As a gesture to Salim

Sïkrï arranging his army and artillery for the Chishtï, the saintly man meditating in the

decisive battle, waiting for reinforcements to midst of wild animals, the stone-cutters of

arrive from neighbouring Bayãnã. The mood the area who came to Sïkrï for their stone,

at the camp was grim and gloomy. In a built a small mosque for his use (Figure 4).

determined speech to his dispirited officers, So this little mosque around his cave was

Bãbur made his memorable renunciation of completed some thirty years before Akbar's

wine, smashed all his cherished gold and first visit and was known as Masjid-i-

silver drinking-cups, poured wine stocks on Sahgtrãshãh (Stone-cutters' Mosque). Thus

to the ground and pledged that he would the main characteristics of the site were an

henceforth lead a life of austerity. His actions old Räjpüt citadel in the east that gave the

galvanized the troops. Each man seized the place its name; quarries in the west that

Korãn and took an oath. Then they advancedprovided abundant building material ; a river

on the opponent Räjpüt formations. The in the north that was regulated to form a

two armies clashed about ten miles west of lake; an army campsite and a battlefield

Sïkrï. Spirits were high and the charges in the vicinity that had established the

desperate. Bãbur carried the day. His most Mughals; and the hill-top abode of Salim

critical moment was overcome. With two Chishtï, whose fame had caused Akbar's

smashing victories in less than a year visit and subsequent determination to build

Mughal

supremacy in northern India was established a dream city around this red rocky ridge.

beyond doubt. Overwhelmed, Bãbur called Akbar was only thirteen years old when he

the place 'Shukrï' - the Arabic term for was hurriedly crowned in a garden on his

gratitude. way to Delhi. He was quickly coming to his

Sïkrï had still more to offer (Figure 3). Its own. Aided by his great physical strength

ridge was also known for its quarries, and and personal courage everything seemed to

its stone-cutters, who must have made their move well for him. At the age of twenty

contribution to the earlier Räjpüt citadel and Akbar abolished several taxes levied on non-

to the elaborate fortifications built by Akbar muslim subjects at the risk of displeasing

785

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 1975

Figure 4. Sketch of conjecturally restored Masjid-i- Sang

cutters' Mosque ), built thirty years before the founding

his muslim chiefs, whose support was philosophy an

essential for his stability. This enormous when he built

courage and conviction places him without for fifteen

doubt far ahead of his time. and territories had multiplied. He was

The Räjpüt threat was met in Akbar's already involved with deeper philoso

characteristic style. The nearest state of ideas. His city reflects these attitudes. T

Jaipur was first won over, by a marriage to was the moment in time, impregna

a Jaipur princess. By a series of other con- enormous energy, social zeal and inte

trivances, high offices and imperial honours, vigour in every walk of life, a time f

Mughal-Räjpüt cooperation spread from afford the freest play to his eminent qu

administration and army to the realm of art Near the fifty-year-old clock towet i

and culture. When he went to Sikri most of main bazaar of present-day Fatehpu

Rãjputãnã except Udaipur and Mewãr had to the newly constructed police station

accepted the Mughal supremacy and Sikri a tiny, elementary mosque that dem

was in a way the 'Gateway to Rãjputãnã', further historical research and closer ar

and through Rãjputãnã to fertile Gujrãt, ological scrutiny. The location and l

whose ports traded freely with Arabia. of the town suggest that his mosque

Abul Fazl observes that from a feeling of important to the Mughals, and it see

thankfulness for his constant success on the have played a significant rôle in the d

battlefields, Akbar would sit many a morning evolution of Fatehpur Sïkrï. This mo

alone in prayer. He spent much of his time is not protected by the Archaeological

with ascetics and Süfls discussing religion, of India6 and no records can as yet be

786

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

that provide adequateforms, historical information

such as emphasis on the already exist-

about it. It has not been ing road possible

between the twoso far How-

mosques.7 to

ascertain its age with ever, any theaccuracy.

situation was handled with great

It is a quiet building of aand

ingenuity domestic

imagination. Takingscalean axis

and its super-structure seems

from the to have

centric mosque been

parallel to the axis

rebuilt on an older plinth. Constructed of the ridge, and one from the Chishti

essentially with the local greyish blue mosque at right angles to it, determined the

quartzite, its corners, mihrab and door- placement of a most unusual building - a

frame have been emphasized by the use of cross- shaped cãrãvansarai. Most cãrãvan-

red sandstone. The mosque itself comprises sarais in India or elsewhere are rows of

a covered area eleven feet by twenty-three rooms and open verandahs placed around a

feet opening on to a court-yard twenty-four square or rectangular courtyard. Sometimes

feet by twenty-nine feet, enclosed by seven- they can be polygonal, adjusted to fit an

foot-high screen walls on the three sides

(Figures 5, 6 and 7). On account of the

increase in the number of visitors, perhaps,

another court-yard was added later to

accommodate larger assemblies. The outer

door altered the direction of the main

entrance, which is now from the west wall.

The open area towards the west between the

mosque and the main bazaar is still known

as Hãt Porão - it means 'Market for the

Camp', even though no market is held there

now. The word 'Parõo' brings to mind those

momentous three weeks in 1527 when

Babur's soldiers camped in the area. Could

it then be the mosque or the spot where

Bãbur made a moving appeal to his officers

and stirred them to determined action lead-

ing to glorious success ?

This mosque, we find, is the focal point

of the town (Figure 8) as its walls went up

speedily on Royal orders. The town was

named Fatehãbãd (founded for victory),

though it eventually became known as

Fatehpur (victory town). For convenience

this mosque will be referred to as 'Centric

Mosque' in this paper.

The Masjid-i-Sahgtrãshãri on the ridge, as

we know, was the other important landmark

that existed prior to the founding of the city.

This was perhaps a better-known mosque,

actively used by the Chishtï family, the local

populace, and visitors from outside. Akbar's

pilgrimage to this mosque, which was loaded

with personal associations and was the

raison d'être for the new city, must have

added a great deal to its popularity. For easy

reference we call it 'Chishtï mosque' in the

rest of this paper.

It was quite natural for the designers of

Fatehpur to utilize these two landmarks in

some manner to evolve the town plan around

them. As a first step in this direction they Figures 5, 6 and 7.

would have looked for a common denomina-

Views of the west wall from the outside (top)

tor to relate the two mosques with each and of the inner courtyard of the structure

other. This could, of course, take numerous referred to as ' Centric Mosque 9

787

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER I975

Figure 8. Centric mosque - its focal position in the town

that it was important to the Mughals

irregular site. The idea theofcrossing

a cross-shaped

of the axes through them was a

sarai (inn) for visitors to novel,

the logical

twoand admirable decision

mosques at arrived

at with keen intellectual clarity (Figure 9).

This was their most creative moment. This

not only helped to bind the two mosques and

the subserviant sardi together; it generated

a comprehensible relationship between the

group and the ridge, preparing a coherent

basis for further design decisions. The

Pukhtã Sardi , as this building is called, can

be translated as an inn solidly built of

permanent materials (as opposed to mud

structures). The name only suggests that it

was among the first few public buildings

built for common use on royal orders. (The

endowment of public sarais and wells was a

common royal pietism ; the numerous

examples on his Grand Trunk Road evince

Akbar's concern in this respect.)

The Pukhtã Sardi had about 100 rooms

with attached verandahs opening on to a

thirty-foot-wide street. After the narrow

crooked lanes of present-day Fatehpur it is

a refreshing experience to find a straight,

wide street over a hundred yards long

(Figure 10). Unfortunately, the Pukhtd Sardi

lies in the populated part of the present town

and is not a protected monument. Its

individual occupants make additions and

alterations to suit their needs. Old structures

Figure 9. A cross-shaped sarai (inn) collapse now and then and new walls appear,

at the crossing of the axes through the mostly in undesirable positions. Before long

two mosques this novel structure will be changed beyond

788

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRÌ

Figure 10. The surviving north-east wing of Pukhtã Sa

recognition, and lost for ever. Its in

city gates three gates

the north of the ridge depended

have already disappeared during the

on the already laststreet pattern of the

existing

decade and the main gate opening earlier Sikarwãr

ontown.

to the

bãzãr (shopping street) stands sadly dis- It is interesting to note that the usage of

figured.8 Nevertheless, the relation of this nine squares in architectural plans and

building with the two mosques and the garden layouts has been an old tradition in

Jãmi Masjid that was built a little later can India with its ultimate source in ancient

be clearly seen in the aerial photograph mythology. Arabian mathematicians inte-

(Figure 11). The NE-SW wind of the sarãi grated this Indian system into their own

had to be slightly adjusted in length to relate synthesis of ancient systems.10 They utilized

it with the existing royal palaces, which were squares based on the use of numerals 1 to 9,

temporarily built parallel to the Chishti in which numerical relationships reveal

house and the contours of the ridge, prior to characteristic visual patterns (Figures 13 and

the laying of the city. 14). Throughout the history of ideas we find

The distance between the centre point of constant reference to mathematics as an

the sarãi and the centric mosque, measured aesthetic ; to the recognition of fundamental

in units of Akbar's time, is 300 Ilahi Gaz 9 orders, sequences and patterns. The square

( Ilãhi Gaz equals 30J in.). This distance formed on a nine-by-nine grid numbered

was then used as a module to fix the position i to 9 horizontally and vertically as illus-

of other major town elements and important trated, was the basis of a whole mathematical

structures (Figúre 12). The grid, based on system, which contained a numerical model

eight super- squares each comprising nine of the universe. Architecturally, the sub-

modular squares, determined the location of division of a square space into nine equal

the major city gates. The Agra gate, how- squares offers the privileged use of the

ever, was placed on the axis of the existing central space, maintaining an implicit visual

approach road from Agrã, because of the relationship with its surround.

special significance of his first visit, when One of the most outstanding, and perhaps

Akbar used that road. Further up, the inter- the first, buildings in Akbar' s time is the

section of this road with the next super-grid Garden Tomb built for his father -

determined the placement of the Naubat Humãyun, supervised by Akbar's mother -

Khãrtã Chowk) which was an open square Hameeda Begum; this is to-day an imposin

with gates in four directions and marked the structure on the river bank in present New

formal entrance to the palace precinct Delhi (Figure 15). The garden layout of

(Figure 29). The location of the other two Humayuñ's tomb11 is based on a nine-square

789

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER I975

•8

.|s

*52

-2

<0 БГ>

e

ÎÏ

1Ä

í88

g8

S "?

О

«•«

.8*

s5

S0'

M

M

О

h-r

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

Figure 12. Town layout based on a modu

Figure 13. Space sub-division on a

Figure 14. Numerical orde

nine-square basis visual patterns

791

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER I975

concept in which the central square is the

platform on which the mausoleum stands. A

later example of a new town that based its

town layout on the nine- square arrangement

is the eighteenth-century Räjpüt city of

Jaipur. The Rãjãs of Amber were in close

contact with the Mughal court because of

marriage alliances, and there was a constant

cultural exchange that reveals itself in many

Mughal and Räjpüt practices. Nevertheless,

when Rãjã Jai Singh decided to build his new

city he leaned heavily on the scriptures for

its layout and extent (Figure 16).

Even though the nine-square grid has

formed the basis for the town plans for both Figure 16. Town plan of Jaipur -

Fatehpur SikrI and Jaipur, unlike Jaipur, a designed city

Sikri does not have a grid plan. While it uses

the grid for siting most of its important land-

marks, its street system does not adhere to a Like Fatehpur Sikri, it was also based on

grid pattern and its palaces are influenced byeight super-squares, each comprising of nine

a variety of other factors, including the modular squares. The module used in

Mecca orientation of the Mosque and the Shãhjahãnãbãd, surprisingly, corresponds to

topography of the ridge. Sikri seems to growthe one used at" Sikri, which we know was

from the site, its surroundings and the obtained in the latter case from the relative

sentiments associated with it. Jaipur on the location of its two already existing mosques.

other hand is a pre-conceived plan pattern Sited at the bend of the river, the four

transferred on to the site rather superficially. corners of Shãhjahãnãbãd were cut along

Another capital city which provides an the diagonals of the corner squares. The

interesting comparison is Shãhjahãnãbãd or super-grid was used to adjust the directions

Old Delhi, built by Akbar's grandson, of the rest of the city walls more or less

Shãhjahãn, seventy years after the founding symmetrically in both directions, forming a

of Fatehpur Sikri. Shãhjahãnãbãd was graceful boat-shape. In both cities the walls

designed as a city of the same size as are about five miles long. The location of

Fatehpur Sikri and a similar design approach most of the city gates is determined by the

shows that it was influenced by the earlier super-grid. The citadel has been placed in

concept (Figure 17). more or less similar positions in both cases

and is approximately one-tenth of the city

area. In both cases the palace buildings

were placed in cardinal directions, parallel to

the mosque and inclined at 45 o to the direc-

tion of the town grid.

Unlike Fatehpur Sikri, Shâhjahân's citadel

again became a separate entity, separated

from the town by high walls and moats.

Chãndni Chowk Bãzãr and Faiz Bãzãr were,

however, well related with the palace

complex, till Aurangzeb decided to alter the

axial approach. The Jãmi Masjid, another

main feature of the city, was sited outside

the citadel walls on a hill site reserved for

this purpose. Splendour was the mood at

Shãhjahãnãbãd, and the city Was designed

for formal state processions. Hence the

location of Jãmi Masjid away from the

citadel placed symmetrically between the

two bãzãrs, was just right and appropriate.

Figure 15. Modular basis of Humäyütf s But at Fatehpur Sikri the overriding emotion

tomb and its garden layout was thanksgiving, and the spirit of humility

792

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

and informality prevailed. the Chishti tombThe

that was built

Jãmi there some

Masjid

at SikrI, again the largest years later and creates a sense

single of enclosure in

building

the city, was the royal gift

and intimacy to

in spite the

of the Shaikh

large dimensions

family. The modular square next to the of the courtyard. The long northern wall

Chishti mosque was used to fix its precise almost turns its back on the royal recreational

position. area sealing it from the town (Figure 20).

The mosque was located in a key position The geometry of strings helped to define

between the Chishti household on its left the overall dimensions of this mosque, and

and the royal residence on the right and a

enabled the designers to relate it mathe-

large part of town in front of it downmatically

the with the Pukhtã Sardi as well; in

slopes of the hill (Figure 18). The Bãdshãhia very subtle manner it added to the cohesion

(King's) Gate, built on a modest scale, of the group of buildings (Figure 21). It was

approaches the open courtyard from the a simple geometrical exercise that offered

east. The west wall, usually the rear wall in

important practical advantages. It was also

most mosques, in this case is intimately the beginning of a mathematical relationship

related to the Chishti household. It almost that originated a concise proportion system

forms a part of it. The Buland Darwãzã that (The provides the key to most of the palace

Lofty Gateway) in the south, set up after designs.

forty steps, establishes a communication with The super-square between the Jãmi

the town and the people. The north wallMasjidhad and Naubat Khãnã Chowk was the

no opening. It just provides a backdropsite to chosen for the imperial household, its

Figure 17. The town plan of Shãhjahãnãbãd ( Old Delhi ) was

influenced by the earlier concept of Fatehpur Sïkri

793

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 1975

Figure 18. Location of Jãmi Masjid and Imperial househ

Sikri ridge determined

Figure 19. The geometrical location of the Seat of Thr

( Aurang Chhatf)

Figure 20. View of Jãmi Masjid and palace complex

794

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

Figure 21. ТЫ geometry of strings relates the overall dimension

of the Pukhtã Sardi with those of the J ami Masjid

centre considered auspicious (Superintendent for the seat of of

Encampment). Regu-

the royal throne - called Aurang lations controlled

Chhatr. the location of all Kork -

The Diwãn-i-Am (Court of Public hãnajãtAudience)

(services) for the imperial household,

was built about the throne seat, andwhich

their distances

is an were carefully fixed for

elevated platform, accessible maximum from the convenience

rest- and order. These

chamber and private garden royal frompreferences

the rear were based on practical

(Figure 19). The space between and thetraditional

Diwãn- reasons, and are geograph-

i-Am and the mosque was then ically defined

available forin Nakshã-i-Ãin-i- Manzil

exclusive audiences, personal (sketch palacesof andCampthe Order), in the Äin-i-Akbari

harem. (Law and Regulation at Akbar's Court), as

The space requirements and graphic illustrated (Figure 22). This was the Mughal

delineation of the royal areas were closely Camp Order that was slightly modified each

defined by the Mughals for expediting thetime as necessary to suit the terrain and

set up of the royal camp. The Mughal court topography. This Camp Order provided a

was frequently on the move. On the average,precise design brief for the new royal

Akbar spent more than four months in a year residence at Fatehpur Slkri.13

travelling, on hunting expeditions, suppress- Depicted in the Nakshã-i-Ãin-i- Manzil

ing provincial rebellions, extending the are four central enclosures meant for royal

frontiers of his empire or visiting holy shrines use. In the first enclosure the King would

in gratitude for his success on the battle- meet the people, soldiers and commoners,

fields. On most of these expeditions he while only privileged noblemen, high officials

would be accompanied by state departments,and intimate friends would find access to the

treasury, princesses with their attendant second enclosure. A two-storied central tent

maids, and noblemen with their retinues. was used in this enclosure to issue the state

Besides, the soldiers on horseback and road- orders and receive intelligence reports. The

building gangs would form a considerable third enclosure housed the King's day

part of this vast moving city.12 Each parãopalace and bed-chamber, where he could

(halt) in a new region was an exercise in rest or retire, and the fourth enclosure,

town-planning. The sites were carefully which was strictly guarded, was for the royal

chosen in advance by the Mir Manzil women.

795

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 197$

The four enclosures were thus like

beautifully arranged

pieces of a jigsaw puzzle

axially in a series in order of increasing

accommodating the imperial household

privacy and security (Figure

(Figure23). All

24). This the

spatial setting based on an

services, workshops and stores for the

inter-locking palace

axial system creates an ordered

were placed around the central core and composition inducing a relaxed mood and

were accessible from an outer road.14 The pleasure of movement, so perceptively

day guards and night guards would form analysed by Jacqueline Tyrwhitt.15 The

another outer ring, protecting the royal changing levels of various courts based on

enclosures and their services. More space the slope of the ridge was used imaginatively

was reserved at the back to accommodate to control the flow of running water. Finally

female attendants and maids for the it royal

would collect in the huge reservoir,

occupants. This overall arrangement must ninety feet by ninety feet, and thirty feet

have formed the basis for the planning of deep.

theBreeze-catching pavilions were built

palace precinct. There were, of course, on its wide retaining walls, enjoying a

several other site conditions to reckon with. panaromic view of the lake. The movement

The ridge was narrow for the usual space about these courtyards is a feast for the

requirements of the royal enclosure in asenses and heightens that sense of participa-

camp. It commanded an excellent view of tion in a great drama of life (Figure 25).

the lake in the north-east that was artificially The narrowness of the ridge at certain

created for the purpose (it brings to mind places led to the extension of some of the

a similar situation successfully met in terraces and platforms beyond its edge,

Chandigarh in our own times) and it was making it necessary to build supporting

all happening against the backdrop of the structures under them. The situation led to

great J ami Masjid. several functional as well as aesthetic

The palace courts were laid out parallel to advantages (Figure 26). The supporting

the mosque, and the four enclosures fitted structures were ideally suited for the

Figure 22. Nakshä-i-Äin-i-Manzil ( Sketch Figure 23. The four royal enclosures were

of Camp Order ) in the Court chronicle arranged axially in order of increasing privacy

6 Ain-i-Akbari 9 and security . Service areas and security

guards formed outer rings

796

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

kãrkhãnãjãt (the service workshops and

production centres) that sometimes fitted

below the palaces. Getting their supplies of

raw material from the street level, and after

processing delivering them at the top level

for consumption, seems like an efficient

arrangement based on economy of move-

ment. Besides, it lent itself to quick and

regular royal supervision - an essential part

of Akbar's daily routine. It was particularly

important for the extensive kitchen depart-

ment to be reasonably near. Working on a

perfection scale all the buildings for the

royal use were placed carefully parallel to the

Jãmi Masjid , while service buildings, for

reasons of economy, were placed along the

contours of the ridge. The combination

produced many unusual, irregular open

areas around the palaces which were linked

together by gateways to provide access to the

Diwãn-i-Ãm and Mahal-i-Khãs (the Royal

Residence). The space volumes obtained in

this manner are very contemporary in spirit.

It reminds one of Louis Kahn' s way of look-

ing at the streets as a series of open rooms.

The Utopian images of the two most

Figure 24. (Below, left ) Royal areas in dressed red sandstone were laid out parallel to the mosque ,

while service areas in grey quartzite followed the contours

Figure 25. (Above, right) Terrace plan showing the relationship of interconnected courts

Figure 26. (Below, right) All factors synthethized into a space-setting offering visual drama and

frequent change of scene

797

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 1975

Figure 27. Chishtï mosque serving as a movement focus

influenced the street layout

Figure 28. The Centric Mosque provided visual focus guidin

placement of several buildings personally important to Akba

798

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER 1975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SIKRI

Figure 29. NaubatKhãnã

Chowk ( conjecturally

restored) with its four

gateways , marks the

beginning of the royal area

Figure 30. View of this

novel structure , called

Diwan-i-Khãs (with most

unusual interior space),

from Akbar'sKhwäbgäh ( Bed

chamber). (Photograph by

courtesy of the Department

of Archaeology , Government

of India)

799

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER 1975

creative designers of the entries century,to the palace

Wrightcomplex. This divided

and Corbusier, both negate thethe

area into

street

privileged

in monuments

its inside,

usual form. and the street system with its service areas,

The feel of the site, open vista and openguards' rooms, stables and water tanks as

character of the citadel, its diagonal place-outside areas. This unnatural separation of

ment to the ridge, wide ramps and high gate-the monuments has proved most unfortunate

ways for elephant movement (Akbar had in many ways. First of all, it deprives visitors

no elephants for personal use), along with of the opportunity of fully experiencing the

Akbar's temperament, contributed to the palaces by using different gates for entering

dramatic character of most of the palace or leaving them. It obscures the function of

approaches from the north-east of the ridge many inside areas, e.g. the Purdah Passage,

(Figure 31). The gates and enclosures on the where continuity was an important con-

other side disappeared, being closer to the sideration. The open character of the city,

town. The inter-linked courts with grand which was its chief characteristic, has been

ramps and controlled vistas provide a space completely destroyed. Since one has to go a

setting in which every rise in level offers a long distance around the walls to visit out-

surprise and a complete change of scene. side areas, most tourists cannot visit them in

Unfortunately these approaches are an im- a short stay. Since these are not visited much

possible experience now as their connections now, even the site engineers and mainte-

with the palaces have been completely nance men have lost their interest in them.

severed during recent years.16 It did not take the town long to encroach on

The government's decision, about eight these areas: new structures have been put

years ago, to collect entrance money from up, new roads made for individual use, and

the tourists visiting the monuments has led free use made of stones that were lying

to a system of entry control which, it seems,scattered around. These happenings could

made it necessary for the Archaeological not be checked by the Survey very effectively ;

Survey to close most of the palace gates and its own labour gangs quite carelessly dug up

Figure 31. Hãthi Põl (. Elephant Gate) approach to the palaces and the J ami Masjid.

( Photograph by courtesy of the Department of Archaeology , Government of India)

800

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FATEHPUR SÍKRI

Figure 32. Sketch of Sikrï ridge from Bharatpur Road sho

two important approaches to the monuments

ruins of the Jauhri Bãzãr to widen the officials on their routine visits to the monu-

existing road and to build a bigger car park. ments. These roads cutting through the

In this context the last decade was mostly preserved courtyards must be discontinued

the unmaking of Fatehpur Sïkrï. Mention and a circulatory road built instead which

of deteriorating monuments at Sïkrï did approaches the monuments from several

seem to disturb many in the government, directions without disfiguring them, and

but unfortunately we are still losing without causing inconvenience to the

Fatehpur Sïkrï very fast every year. pedestrian experience.

Many beautiful monuments located near With greater thought and careful survey

the city walls are never visited by tourists it should be possible, without interfering

because of their inaccessibility. The roadwith the life of the town, to introduce a road

system is totally inadequate. Some of thesystem which would cover a much larger

gates in the city walls present a panoramic area and bring all the scattered monuments

view of the palaces from advantageous within the reach of the tourists. The implicit

angles, but they are so inaccessible by car visual energies of the town need to be

that very few people can get up there. From augmented by a movement pattern based on

Gwãlior Gate in the south-east, one gets a a sympathetic perception of the monuments,

grand view of the imposing Buland Darwãzã , their functions and the sensitivity of their

dominating the whole countryside. The placement. Carefully handled, Fatehpur

stepped up city wall across the hill in the Sïkrï can assume an entirely new dimension

distance looks very sculpturesque from this by enabling visitors to experience Akbar's

point. Nearby is Tõdar Mai's17 octagonal dream city objectively as a meaningful

pavilion, which once stood in an extensive sequence.

garden. Not far from here, outside the The first step in this direction is to check

Terha Gate, is Bahâu-ud-Dïn's Tomb. the disruptive forces at all levels that are

Bahäu-ud-Din was the Superintendent causing of the present unmaking of this unique

Works, responsible for the construction of

historical heritage and to stop all arbitrary

the city. This pleasant little tomb lies decisions that are eroding the very principles

neglected, unkown and unvisited. of this magnificent townplan. That is the

The best view of the ridge and the royalvery least that we can do towards the making

palaces can be obtained from the Bharatpurof Fatehpur Sïkrï.

Road (Figure 32). The long lines of palaces

with their domes and pinnacles can be seen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

from a distance of several miles as you driveI am indebted to Mr. Din Dayal Parashar,

towards the city. An approach road from thisMunicipal Commissioner, Fatehpur Sïkrï,

side could lead the visitors either straight tofor showing me around some of the old parts

the Diwãn-i-Am or to the Hãthi Põl of present Fatehpur town. His brother, Mr.

(Elephant Gate) entrance on the other Murari side. Lai Parashar, very kindly enabled

Both these entries are a rewarding experi- me to examine several old documents and

ence, and need to be developed with due drawings in the family possession. Special

care and consideration. The complete road thanks are due to Mr. Krishna Ailawadi for

system at Fatehpur Sikri needs to be re- his help in the preparation of graphic

viewed afresh, considering the ever-increas- material, and to Miss Anne Upsom for

ing tourist trade and what the city has to secretarial assistance. I am especially grateful

offer. The present roads (laid over sixty to Mr. John Burton-Page and Mr. Anthony

years ago) were meant to carry only a few Mascarenhas for the critical reading of the

801

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER I975

manuscript and their valuable formerly a group of states

comments andincluding Jodhpur,

suggestions. Bikãnêr, Jaipur, Udaipur, etc. ; now Rãjasthãn.

It would be appropriate to acknowledge Sarãi A rest house for the caravans along the

main trade routes, built frequently by various

here that the basic theme of this paper was

kings.

first presented at Fatehpur Sïkrï in Decem- Shãhjahãnãbãd Present Old Delhi ; new capital

ber 1972, in a Seminar sponsored by the built by Shähjahän when he moved from

Department of Archaeology, Government of Ägrä to Delhi.

India, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shaikh A Muslim saint or scholar.

the founding of Akbar's Fatehpur. I am Sikri Abode of Sikarwãrs.

grateful to the Department for making thisSikarwãr A Räjpüt tribe.

participation possible and for extending Sufi A Muslim mystic; a dervish.

other courtesies from time to time, which NOTES

have greatly helped in further investigations. i. Vincent A. Smith, Akbar the Great Mogul 1542-

New Delhi, 1962, pp. 77. 'Agra and Fatepore are t

very great cities, either of them much greater

London and very populous. Between Agr

Fatepore ... all the way is a market of victua

GLOSSARY many other things, as full as though a man wer

in a towne, and so many people as if a man were

market.' Description by Ralph Fitch, September

Äin-i-Akbari 'Law and Regulations 2. TheatCambridge

Akbar's History of India , Vol. IV, New D

Court', compiled by his Court Chronicler and 'No sooner was the idea formed

1963» pp. 538-9.

close associate Abul Fazal. plans were prepared, artizans summoned from all

parts of his dominion, and the work pushed on with

Aurang Chhatr The royal throne with its such lightning rapidity that not only its splendour

but the almost magical speed with which it was

overhead ornamental pavilion. completed was a matter of contemporary comment.'

Bãdshãhi King's; royal. 3. B. D. Sanwal, Agra and its Monuments , 1968, pp. 46.

For details of the Chishti household see my article,

Buland Darwãzã Lofty gateway built in the 'Can Fatehpur Sikri Still be Saved?', Design incor-

south wall of Jãmi Masjid at Fatehpur Sikri. porating Indian Builder , April 1972, pp. 19-24.

Chishti The Chishti dervish order (silsilã) was 4. The Sikarwãr Citadel on tne adjoining hill north-east

of Fatehpur has been completelv chiselled down by

introduced into India by Khwãjã Muin al-Din a large number of stone-cutters working on it for the

last seven years. Its last remnants are two Bãolis

Chishti of Ajmer (1141-1236) and rapidly (stepped wells) which still exist in a rather dilapidated

established a reputation for sanctity. condition in the north-west and south-east of this

Diwãn-i-Am Court of public audience. hill. These seem to be part of the water supply

svstem which once served this citadel.

Diwãn-i-Khãs Hall of private audience. 5. Stanley Lane-Poole, Babar , New Delhi, 1964» Р- 169.

Hammãm Baths. 6. Recently the courtyard walls of this mosque have

been used for the extension of a neighbouring flour

Hãt Parão Market for the camp. mill. Left unchecked, this encroachment would soon

endanger the existence of this structure.

Hãthi Pol Elephant Gate. 7. Parts of this road can be seen in the old revenue maps

Ilãhi Gaz A unit of measurement of Akbar's of Fatehmir Sikri.

time. 8. A well in the north-east of this gate was covered and

concreted some years ago to make room for the new

Jãmi Masjid Principal mosque for large municipal offices built there. This well fulfilled the

assemblies - especially on Fridays. needs of the occupants of this Sarãi and also supplied

the great public Hammãm situated between this gate

Kãrkhãnãjãt Plural of kãrkhãnã ; meaning and the Buland Darwãzã.

workplace. Service areas and production 9. Dr. Chagtäi, basing his calculation on the discovery

of a manuscript which gives measurements of the Tãj

centres.

in gaz, defines 1 gaz as equal to 0.79 metres, i.e.

31.3 inches.

Khwãbgãh Bed chamber.

10. Keith Albarn, Jenny Miall Smith, Stanford Steele,

Lodi An Afghan tribe. Dinah Walker, The Language of Pattern, London,

Mahal-i-Khãs The Emperor's private apart-

1974, PP. 10-12.

1 1 . Minutely observing Mughal miniatures, Ellen Sm

ments.

presents an illustration from Waqiãt-i-Bãburi

(painted in Akbar's time) showing Bãbur and his

Masjid-i-Sangtrãshãn Stone-cutters' mosque.

architect discussing the plan of Bãgh-i-Wafã. Bãbur

Mir Manzil The Superintendent of Encamp-

is pointing with his right hand at the plan and three

meiit. of the gardeners stretch a rope to check the position

of the waterway. Miss Smart convincingly shows in

Nakshä-i-Äin-i- Manzil Sketch of Camp Order

an enlarged detail that this plan has lines drawn to

form a grid.

as described in Äin-i-Akbari by Abul Fazal.

See E.S. Smart, ' Graphic Evidence for Mughal Archi-

Naubat Khãnã Chowk City square with music

tectural Plans', AARP (Art and Archaeological

Research Paoersi. 6. London. IQ7¿. DD. 22-Ч.

gallery to announce royal arrivals and

12. William Irvine, The Army of Indian Moghuls , pp.

departures and other important hours. 109-10.

Parão Halt; stay; army camp or royal camp. 13. Abul Fazal Allãmi, Ain-i-Akbari, trans. H. Bloch-

mann. Delhi, iq6s, Plate IV and dd. 49-so.

Pathãn A people inhabiting the hilly country

14. For a detailed account of service areas, see my

to the north-west of Lahore; a soldier; a article, 'Imperial Workshop at Fatehpur Sikri - The

Rovai Kitchen', AARP s, dd. 28-41.

warrior; the Afghan race. 15. J. Tyrwhitt, 'The Moving Eye' in Explorations in

Pukhtã Strong ; permanent ; (a structure) made Communications , Boston, i960, p. 90.

16. See my article, 'Do India's Archaeologists Know

of baked brick or stone. what They Are Doing at Fatehpur Sikri?', Design

Rãjã A Hindu equivalent to a king. incorporating Indian Builder , New Delhi, March

1972, pp. 23-30.

Räjpüt Member of Hindu land-owning warrior

17. Todar Mai, who was an assistant Vakil, became

caste of north-west India. Prime Minister of the Empire in 1582 and prepared

a scheme for the improvement of the revenue

Rãjputãnã The country of the Räjpüts; administration.

802

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEMBER I975 THE MAKING OF FÀTEHPUR SIKŘI

DISCUSSION

The Chairman: I thought I knew a little on trade routes and only twenty miles away. The

about Fatehpur Sikri, having visited it a numbertrade and crafts soon followed to Ãgrã as well.

of times, but Mr. Davar has shown me how I do not accept the view put forward by some

relatively little I do know and what an enormous historians that the city was abandoned for ever

amount there is still to know. I can hardly wait because of an unexpected shortage of water.

to go back there, and look again with the insights Mr. Reginald Massey: Is it known whom

he has given us this evening. the architects employed were ? Were they

Mr. Oscar Davies: Why was the city Indians ? Were they Hindus, or Muslims from

abandoned after fifteen years ? Iran ? Also, is there any indication of the size of

The Lecturer: It seems that there were the labour force employed ?

The Lecturer: There is no definite informa-

several personal, political and cultural factors

which must have contributed towards this. In tion about the architects employed. Kãsim Khãn

was Akbar's chief engineer for building the fort

the first instance, the very circumstances that

at Ãgrã and is mentioned here and there in other

led to this speedy undertaking lost their validity

over the years. The new city was a way of contexts. There is a small tomb at Sikri outside

celebrating the birth of Prince Salim. It was a the town wall - between the palaces and the

way of acknowledging the divine blessing and quarries. It is called Bahäu-ud-Din's Tomb.

the good luck that the place had brought. This Bahãu-ud-Din is traditionally believed to be

initial fondness for the place must have even- Superintendent of Works, perhaps responsible

tually become a sore point for Akbar, who at afor the mosque and palace complex. As the

later stage became seriously concerned about thecitadel arose with great speed, a large number of

habit and attitude of the young prince. In thismaster builders and craftsmen from all over the

growing antagonism, the king must be resent- country contributed here. Many provincial styles

fully aware of the natural sympathy and unex- can be seen at Sikri side by side, and prominent

pressed loyalty of Chishti household for Prince among these is that of Gujarãt. It has not been

Salim, who had grown up with Chishti grand- estimated, so far, how many people were em-

sons from early childhood. This is just one ployed for the job.

aspect. Shaikh Chishti, whose presence initially Mrs. Marjorie Gallop: Did the aban-

inspired the project, died soon after. donment of the city seem a very dramatic event

After a decade at Sikri, Akbar was passing at the time ? Did it have any impact on literature,

through the most critical period of his reign. were there lamentations for the abandonment,

His involvement in the famous religious debates or was it more or less written off?

at Sikri eventually led him, step by step, to

The Lecturer: It is a very fascinating

assume all powers of a religious head. Then he

question. There are references to the aban-

introduced a new religion, which in spite of

doned city in some travelogues, but I have not

subtle pressures, was not accepted by most of

come across, so far, any lamentation or personal

his close associates. This must have resulted in

sorrow expressed in the poetry or prose of the

a deep sense of personal defeat at that moment,

time.

in spite of compensations provided by success in

Mr. Derick Garnier: Whether or not one

other areas. Intelligence reports about a planned

rebellion at this time must have caused some believes that there was a shortage or failure of

uneasiness. There was trouble in Bengál on water

one at Sikri, there certainly was a very exten-

end, and his cousin Mirza Hakim in Kãbul on sive system of plumbing. Would Mr. Davar like

the other end, had ambitious plans to take to say something about tfie water system, its

advantage of the situation. An army march to creation and preservation ?

Kãbul kept Akbar away from Sikri for about a The Lecturer: There was indeed a very

year. Around this time, severe floods in Sikri elaborate water supply system for the palaces and

caused havoc, disrupting many services. The most of it is in an excellent state of preservation.

fact that these services were never fully restored As the city was built, a large lake was created in

suggests that Akbar was already disillusioned the north-west, which must have helped in soil

with this place. Later, suspected danger from saturation, as a large number of wells were built

Bädäkashän made it necessary for him to stay by the people. Two large reservoirs were built

on in Lahore, which was also more suitable for near the palaces on the two sides of the ridge.

extending the empire northwards and west- Persian wheel system was used to pull water to

wards. In history it is not at all uncommon for the palace level in three stages. The flow would

kings to shift capitals to new geographical then be directed through garden canals, tanks,

centres close to areas of activity. In the case of decorative channels, fountains, etc., using the

Sikri, however, since it was a young city, this natural slope of the hill and the varying levels of

withdrawal of Royal presence as well as patron- palace courts to collect all the water in the two

age so soon after its conception caused public reservoirs. The paved terraces also served a

abandonment as well. Noblemen generally pre- catchment areas and not a drop of water was

ferred Âgrã, a much larger city, naturally grown wasted. Both hot water and cold water systems

803

This content downloaded from

49.36.180.209 on Sat, 24 Feb 2024 17:03:14 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS NOVEMBER I975

were in use in all public and with royal baths.

a square centralA net- again reached by

platform

work of water channels served the town and its

four bridges. He was certainly influenced by the

gardens. But then, of course, all towns in bridge

hot concept, whether it is the transitional

and dry climates depend on nature and on rains

quality of the bridge or the space experience it

to some extent. offers. May be it was the act of bridging itself :

The Chairman: Is it known whether the the bridging of the people, the bridging of the

abandonment of the city happened to languages

follow anda literature and the bridging of the

number of years when there was a bad religions

mon- that he attempted in a big way. Akbar