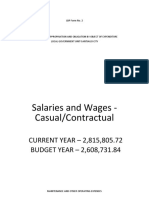

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Traveling Booksellers Were Common Figures in Europe in The Middle Ages

Traveling Booksellers Were Common Figures in Europe in The Middle Ages

Uploaded by

Saqib FaridCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- E Paper Seminar ReportDocument27 pagesE Paper Seminar Reportvrushali kadam100% (2)

- PayU - Sales DeckDocument27 pagesPayU - Sales DeckaNANTNo ratings yet

- Vesta 1000 01 PDFDocument53 pagesVesta 1000 01 PDFDuta NarendratamaNo ratings yet

- LBP Form No. 4Document8 pagesLBP Form No. 4Shie La Ma RieNo ratings yet

- KAREN NUÑEZ v. NORMA MOISES-PALMADocument4 pagesKAREN NUÑEZ v. NORMA MOISES-PALMARizza Angela MangallenoNo ratings yet

- Digital, Hand and Mechanical PrintingDocument18 pagesDigital, Hand and Mechanical PrintingJessicaa1994No ratings yet

- Wa0018.Document1 pageWa0018.NITHYASHREE SNo ratings yet

- STS Mod5Document5 pagesSTS Mod5karen perrerasNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Influence of Mass Communication in Contemporary Society - Part 1Document53 pagesModule 3 Influence of Mass Communication in Contemporary Society - Part 1Rizza RiveraNo ratings yet

- Swenson 1 Dan Swenson Printing Press: Part One (Timeline)Document6 pagesSwenson 1 Dan Swenson Printing Press: Part One (Timeline)Dan SwensonNo ratings yet

- History of Mass Media in KenyaDocument25 pagesHistory of Mass Media in KenyaJaque Tornne100% (1)

- ThickenerDocument24 pagesThickenersujanNo ratings yet

- Ge 107Document6 pagesGe 107daryl.pradoNo ratings yet

- Chapter-7 STSDocument8 pagesChapter-7 STSCasimero CabungcalNo ratings yet

- Cope KalantzisSocialWebDocument14 pagesCope KalantzisSocialWebViviane RaposoNo ratings yet

- Print MediaDocument16 pagesPrint MediaGracy JohnNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - STSDocument7 pagesChapter 7 - STSRonna Panganiban DipasupilNo ratings yet

- MEIL REVIEWER Hm3a First SemDocument7 pagesMEIL REVIEWER Hm3a First Semgoboj12957No ratings yet

- Baptista Gil. Retos Editoriales en La Era Digital, Una Propuesta para Construir Una Revista OnlineDocument10 pagesBaptista Gil. Retos Editoriales en La Era Digital, Una Propuesta para Construir Una Revista OnlineFrancisco GilNo ratings yet

- MIL 3rd ReviewerDocument13 pagesMIL 3rd Reviewerraven patidioNo ratings yet

- Letterpress PrintingDocument9 pagesLetterpress PrintingkumkumnadigNo ratings yet

- Interactive MultimediaDocument19 pagesInteractive Multimedias160818035No ratings yet

- Processing of Visible Language PDFDocument530 pagesProcessing of Visible Language PDFlazut273No ratings yet

- Shimmer, don't Shake: How Publishing Can Embrace AIFrom EverandShimmer, don't Shake: How Publishing Can Embrace AIRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- 21st CenturyDocument5 pages21st CenturyKaye KayeNo ratings yet

- Print CultureDocument8 pagesPrint Cultureryanghosle99No ratings yet

- Katherine McCoyDocument21 pagesKatherine McCoyLucas AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of PrintingDocument9 pagesThe Emergence of Printingمساعد طلبة التخرجNo ratings yet

- Digital Scholarly EditingDocument21 pagesDigital Scholarly EditingNatalie Kiely100% (1)

- Master ThesisDocument50 pagesMaster ThesisATHARNo ratings yet

- Bolter - Writing Space 1-46 PDFDocument46 pagesBolter - Writing Space 1-46 PDFJuan RiveraNo ratings yet

- Mil 3Document24 pagesMil 3Catherine SalasNo ratings yet

- Print CultureDocument4 pagesPrint Cultureshweta sinhaNo ratings yet

- Center For The Study of Digital LibrariesDocument12 pagesCenter For The Study of Digital LibrariesIrene Garcia BlancoNo ratings yet

- Studies 1 CH 5Document28 pagesStudies 1 CH 5bao ngan le nguyenNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of CommunicationDocument15 pagesA Brief History of CommunicationPortugal Mark AndrewNo ratings yet

- Full Download PDF of (Ebook PDF) Understanding Communication Theory: A Beginner's Guide All ChapterDocument43 pagesFull Download PDF of (Ebook PDF) Understanding Communication Theory: A Beginner's Guide All Chapterkeoghcemic100% (4)

- Forms of Mass MediaDocument3 pagesForms of Mass MediaJermane Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- History of Massmedia AssDocument11 pagesHistory of Massmedia Assilesanmi rushdahNo ratings yet

- How AI Is Helping Historians Better Understand Our PastDocument16 pagesHow AI Is Helping Historians Better Understand Our PastPatricia GeoNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of MediaDocument349 pagesDictionary of Mediadatadrive92% (12)

- Article-The Printing Press and Its EffectsDocument3 pagesArticle-The Printing Press and Its EffectsBoy SoyNo ratings yet

- Formal and Informal Language 1cb8vmxDocument9 pagesFormal and Informal Language 1cb8vmxrikiNo ratings yet

- Ola Khalil Abbas 11831515 Instructor: Hasan Fakih July 21, 2022 Research PaperDocument8 pagesOla Khalil Abbas 11831515 Instructor: Hasan Fakih July 21, 2022 Research PaperolaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - LiteracyDocument4 pagesLesson 1 - LiteracySHEILA SUCUAJENo ratings yet

- Information AgeDocument27 pagesInformation Agekaren adornadoNo ratings yet

- Cobley 2008Document7 pagesCobley 2008Amir SahidanNo ratings yet

- E-Journal Usage Study and Scholarly Communication Using Transaction Log AnalysisDocument50 pagesE-Journal Usage Study and Scholarly Communication Using Transaction Log AnalysisRavi PrakashNo ratings yet

- Report MFDocument11 pagesReport MFgiangianrueloNo ratings yet

- Media and Information Literacy SummaryDocument5 pagesMedia and Information Literacy SummaryAllen JangcaNo ratings yet

- Informatics - It's Scope and Met - A - I. Mikhailov PDFDocument15 pagesInformatics - It's Scope and Met - A - I. Mikhailov PDFMaria Cristina MartinezNo ratings yet

- Diss OwshiiDocument30 pagesDiss OwshiiRheamae AbieroNo ratings yet

- Media and Information LiteracyDocument65 pagesMedia and Information LiteracyKali LinuxNo ratings yet

- Gowth of Communication TechnologyDocument23 pagesGowth of Communication TechnologyOmarNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Evolution From Traditional To New MediaDocument6 pagesLesson 2 Evolution From Traditional To New MediaLawrence ManlapazNo ratings yet

- Science Technology SocietyDocument28 pagesScience Technology SocietyKaguya SamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 and 8 Word FileDocument26 pagesChapter 7 and 8 Word Fileru ruNo ratings yet

- Module 002 Evolution of Traditional To New MediaDocument6 pagesModule 002 Evolution of Traditional To New MediaAlex Abonales DumandanNo ratings yet

- As If By Chance: Sketches of Disruptive Continuity in the Age of Print from Johannes Gutenberg to Steve JobsFrom EverandAs If By Chance: Sketches of Disruptive Continuity in the Age of Print from Johannes Gutenberg to Steve JobsNo ratings yet

- World without history? Digital information is volatile: with it our culture can disappear but its preservation can save usFrom EverandWorld without history? Digital information is volatile: with it our culture can disappear but its preservation can save usNo ratings yet

- The shortest century: our culture can disappear, its preservation can save usFrom EverandThe shortest century: our culture can disappear, its preservation can save usNo ratings yet

- RPL 008 Chrism Mass (Yr A, B, C) - Full ScoreDocument2 pagesRPL 008 Chrism Mass (Yr A, B, C) - Full Score_emre07_No ratings yet

- Sponge City in Surigao Del SurDocument10 pagesSponge City in Surigao Del SurLearnce MasculinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document2 pagesChapter 1Rexson Dela Cruz TagubaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Monopolistic CompetitionDocument9 pagesAn Overview of Monopolistic CompetitionsaifNo ratings yet

- 2004cwl Infrequent Pp52-103Document52 pages2004cwl Infrequent Pp52-103Henry LanguisanNo ratings yet

- TheSun 2009-04-10 Page04 Independents Can Keep Seats CourtDocument1 pageTheSun 2009-04-10 Page04 Independents Can Keep Seats CourtImpulsive collectorNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Social Media On Educational Performance With Reference To College StudentsDocument5 pagesThe Impact of Social Media On Educational Performance With Reference To College StudentsIjcams PublicationNo ratings yet

- Advanced Presentation Skills WorkshopDocument34 pagesAdvanced Presentation Skills WorkshopJade Cemre ErciyesNo ratings yet

- kazan-helicopters (Russian Helicopters) 소개 2016Document33 pageskazan-helicopters (Russian Helicopters) 소개 2016Lee JihoonNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations When Conducting ResearchDocument3 pagesEthical Considerations When Conducting ResearchRegine A. UmbaadNo ratings yet

- DS Dragon Quest IXDocument40 pagesDS Dragon Quest IXrichard224356No ratings yet

- EagleBurgmann - Fluachem Expansion Joints - ENDocument5 pagesEagleBurgmann - Fluachem Expansion Joints - ENRoberta PugnettiNo ratings yet

- Tissue Preservation and Maintenance of Optimum Esthetics: A Clinical ReportDocument7 pagesTissue Preservation and Maintenance of Optimum Esthetics: A Clinical ReportBagis Emre GulNo ratings yet

- Wilcom EmroiWilcom Embroidery Software Learning Tutorial in HindiDocument10 pagesWilcom EmroiWilcom Embroidery Software Learning Tutorial in HindiGuillermo RosasNo ratings yet

- Reading PracticeDocument1 pageReading Practicejemimahluyando8No ratings yet

- Accessibility of Urban Green Infrastructure in Addis-Ababa City, Ethiopia: Current Status and Future ChallengeDocument20 pagesAccessibility of Urban Green Infrastructure in Addis-Ababa City, Ethiopia: Current Status and Future ChallengeShemeles MitkieNo ratings yet

- Ipi425812 PDFDocument5 pagesIpi425812 PDFshelfinararaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Subingsubing G.R. Nos. 104942-43 November 25, 1993Document13 pagesPeople vs. Subingsubing G.R. Nos. 104942-43 November 25, 1993Felix Leonard NovicioNo ratings yet

- Chapter Vii - Ethics For CriminologistsDocument6 pagesChapter Vii - Ethics For CriminologistsMarlboro BlackNo ratings yet

- Palazzo Vecchio and Piazza SignoriaDocument2 pagesPalazzo Vecchio and Piazza SignoriaHaley HermanNo ratings yet

- Anuj Nijhon - The Toyota WayDocument35 pagesAnuj Nijhon - The Toyota WayAnuj NijhonNo ratings yet

- PT Bank MandiriDocument2 pagesPT Bank MandiriImanuel Kevin NNo ratings yet

- Conjugarea Verbului Manifesta: Indicativ PrezentDocument4 pagesConjugarea Verbului Manifesta: Indicativ PrezentAndrei PleșaNo ratings yet

- The Future Progressive and WillDocument6 pagesThe Future Progressive and WillDelia CatrinaNo ratings yet

- Social Responsibility in The Jewelry IndustryDocument6 pagesSocial Responsibility in The Jewelry IndustryMK ULTRANo ratings yet

- Cours - 9eme - Annee - de - Base-Anglais-Pollution A Threat To Our EnvironmentDocument3 pagesCours - 9eme - Annee - de - Base-Anglais-Pollution A Threat To Our EnvironmentRiRi BoubaNo ratings yet

Traveling Booksellers Were Common Figures in Europe in The Middle Ages

Traveling Booksellers Were Common Figures in Europe in The Middle Ages

Uploaded by

Saqib FaridOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Traveling Booksellers Were Common Figures in Europe in The Middle Ages

Traveling Booksellers Were Common Figures in Europe in The Middle Ages

Uploaded by

Saqib FaridCopyright:

Available Formats

Traveling booksellers were common figures in Europe in the Middle Ages (5th century to 15th century), but in the

early Middle Ages bookmaking was largely a monopoly of the scriptoria, or writing rooms, of monasteries. For some centuries books written in the monasteries were produced for the exclusive use of the monks or their pupils. Therefore, for centuries the knowledge of reading and writing remained confined to the clerics. Later, under the influence of certain princes who owed their early education to monastery schools, the libraries of kings and nobles acquired manuscripts of the world's literature. Later in the Middle Ages, bookselling was stimulated by the rise of universities, particularly the University of Paris in France and the University of Bologna in Italy. The universities supervised the preparation of textbooks and literary works and also prescribed the rates at which the books were to be sold or leased. The booksellers, known as stationarii, usually were university officials or graduates. The stationarii of the University of Paris supplied not only the university but nearly all the scholars of Europe. The stationarii at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England began their work some years later than those in Paris or Bologna. Without the restrictions that hampered the freedom of the French and Italian scribes, their business flourished. B.Development of the Publishing Industry

Dissemination of information

The process of recording information by handwriting was obviously laborious and required the dedication of the likes of Egyptian scribes or monks in monasteries around the world. It was only after mechanical means of reproducing writing were invented that information records could be duplicated more efficiently and economically. The first practical method of reproducing writing mechanically was block printing; it was developed in China during the T'ang dynasty (618907). Ideographic text and illustrations were engraved in wooden blocks, inked, and copied on paper. Used to produce books as well as cards, charms, and calendars, block printing spread to Korea and Japan but apparently not to the Islamic or European Christian civilizations. European woodcuts and metal engravings date only to the 14th century. Printing from movable type was also invented in China (in the mid-11th century AD). There and in the bookmaking industry of Korea, where the method was applied more extensively during the 15th century, the ideographic type was made initially of baked clay and wood and later of metal. The large number of typefaces required for pictographic text composition continued to handicap

printing in the Orient until the present time. The invention of character-oriented printing from movable type (144050) is attributed to the German printer Johannes Gutenberg. Within 30 years of his invention, the movable-type printing press was in use throughout Europe. Character-type pieces were metallic and apparently cast from metallic molds; paper and vellum (calfskin parchment) were used to carry the impressions. Gutenberg's technique of assembling individual letters by hand was employed until 1886, when the German-born American printer Ottmar Mergenthaler developed the Linotype, a keyboard-driven device that cast lines of type automatically. Typesetting speed was further enhanced by the Monotype technique, in which a perforated paper ribbon, punched from a keyboard, was used to operate a type-casting machine. Mechanical methods of typesetting prevailed until the 1960s. Since that time they have been largely supplanted by the electronic and optical printing techniques described in the previous section. Unlike the use of movable type for printing text, early graphics were reproduced from wood relief engravings in which the nonprinting portions of the image were cut away. Musical scores, on the other hand, were reproduced from etched stone plates. At the end of the 18th century, the German printer Aloys Senefelder developed lithography, a planographic technique of transferring images from a specially prepared surface of stone. In offset lithography the image is transferred from zinc or aluminum plates instead of stone, and in photoengraving such plates are superimposed with film and then etched. The first successful photographic process, the daguerreotype, was developed during the 1830s. The invention of photography, aside from providing a new medium for capturing still images and later video in analog form, was significant for two other reasons. First, recorded information (textual and graphic) could be easily reproduced from film, and, second, the image could be enlarged or reduced. Document reproduction from film to film has been relatively unimportant, because both printing and photocopying (see above) are cheaper. The ability to reduce images, however, has led to the development of the microform, the most economical method of disseminating analog-form information. Another technique of considerable commercial importance for the duplication of paper-based information is photocopying, or dry photography. Printing is most

economical when large numbers of copies are required, but photocopying provides a fast and efficient means of duplicating records in small quantities for personal or local use. Of the several technologies that are in use, the most popular process, xerography, is based on electrostatics. While the volume of information issued in the form of printed matter continues unabated, the electronic publishing industry has begun to disseminate information in digital form. The digital optical disc (see above Recording media) is developing as an increasingly popular means of issuing large bodies of archival informationfor example, legislation, court and hospital records, encyclopaedias and other reference works, referral databases, and libraries of computer software. Full-text databases, each containing digital page images of the complete text of some 400 periodicals stored on CD-ROM, entered the market in 1990. The optical disc provides the mass production technology for publication in machinereadable form. It offers the prospect of having large libraries of information available in virtually every school and at many professional workstations. The coupling of computers and digital telecommunications is also changing the modes of information dissemination. High-speed digital satellite communications facilitate electronic printing at remote sites; for example, the world's major newspapers and magazines transmit electronic page copies to different geographic locations for local printing and distribution. Updates of catalogs, computer software, and archival databases are distributed via e-mail, a method of rapidly forwarding and storing bodies of digital information between remote computers. Indeed, a large-scale transformation is taking place in modes of formal as well as informal communication. For more than three centuries, formal communication in the scientific community has relied on the scholarly and professional periodical, widely distributed to tens of thousands of libraries and to tens of millions of individual subscribers. In 1992 a major international publisher announced that its journals would gradually be available for computer storage in digital form; and in that same year the State University of New York at Buffalo began building a completely electronic, paperless library. The scholarly article, rather than the journal, is likely to become the basic unit of formal communication in scientific disciplines; digital copies of such an article will be transmitted electronically to subscribers or, more likely, on demand to individuals and organizations who learn of

its existence through referral databases and new types of alerting information services. The Internet already offers instantaneous public access to vast resources of noncommercial information stored in computers around the world. Similarly, the traditional modes of informal communicationsvarious types of face-to-face encounters such as meetings, conferences, seminars, workshops, and classroom lecturesare being supplemented and in some cases replaced by e-mail, electronic bulletin boards (a technique of broadcasting newsworthy textual and multimedia messages between computer users), and electronic teleconferencing and distributed problemsolving (a method of linking remote persons in real time by voice-and-image communication and special software called groupware). These technologies are forging virtual societal networkscommunities

he invention of devices for representing language is inextricably related to issues of literacythat is, to issues of who can use the script and what it can be used for. Competence with written language, in both reading and writing, is known as literacy. High levels of literacy are required for using scripts for a wide range of somewhat specialized functions. When a large number of individuals in a society are competent in using written language to serve these functions, the whole society may be referred to as a literate society. Just as scripts have a history, so too does literacy. This history closely reflects the increasing number of ways in which written materials have been used and the increasing number of readers who have been able to use them. Scripts were elaborated to serve new purposes; more importantly, new kinds of writing systems permitted them to serve a wider range of purposes by a larger number of individuals. Although the uses of writing reflect a host of religious, political, and social factors and hence are not determined simply by orthography, two dimensions of the script are important in understanding the growth of literacy: learnability and expressive power. Learnability refers to the ease with which the script can be acquired, and expressive power refers to the script's resources for unambiguously expressing the full range of meanings available in the oral language. These two dimensions are

inversely related to each other. Simple restricted scripts are readily learned. Pictographic signs such as those used in environmental writing and logographic scripts with a limited set of characters are easiest to learn and, indeed, are acquired more or less automatically by children. Syllabaries such as the Cree syllabary are reported to be learnable in a day, while the indigenous Liberian Vai syllabary is learned in a few days. Consonantal scripts and alphabets are difficult to learn and usually require a few years of schooling. Full logographic systems such as Chinese or mixed systems such as Japanese are difficult to acquire because they require the memorization of thousands of distinctive characters. Once learned, however, they appear to function as well as alphabets. But pictographic signs and logographic scripts with a limited readily learnable set of graphs are restricted to expressing a limited range of meanings. Syllabaries are highly ambiguous and hence dependent on knowledge not only of the script but also on the likely content of the message. Syllabaries therefore serve a restricted set of functions, primarily personal correspondence. They are of limited use in expressing novel meanings that could be read in the same way by all readers of the script. Consonantal and alphabetic writing systems can express essentially all the lexical and grammatical meanings in the language (but not the intonation) and are thus highly suitable for the expression of original meanings. They constitute an ideal medium for technical, legal, literary, and scientific texts that must be read in the same way by readers dispersed in both time and space. Some scholars have held that the high degree of literacy in the West is a consequence of the optimality of the alphabet in balancing the two dimensions of learnability and expressive power. Such generalizations, however, ignore the fact that the optimal balance may differ from language to language. A consonantal writing system is almost as complete for Hebrew as the alphabet is for Greek, but a consonantal writing system would be hopelessly ambiguous for Greek. Similarly, a syllabary or an alphabet would be quite useless for Chinese, a language with a staggering degree of homophony. Logographic systems achieve a comparable level of explicitness by the addition of new characters, but the ease of addition is traded off against the ease of acquisition. Instead of attempting to determine whether one system is better than another, it is perhaps more reasonable to assume that each script is optimal for the language it represents and for the functions it has evolved to serve.

The ease of acquisition of a script is an important factor in determining whether a script remains the possession of an elite or whether it can be democratizedthat is, turned into a possession of ordinary people. Syllabaries are readily learned, but their residual ambiguity tends to restrict their uses. Alphabets have been viewed by many historians as decisive in the democratization of writing; alphabetic writing could become a possession of ordinary people and yet serve a full range of functions. However, democratization of a script appears to have more to do with the availability of reading materials and of instruction in reading and the perceived relevance of literacy skills to the readers. Even in a literate society, most readers learn to read only a narrow range of written materials; specialized materials, such as those pertaining to science or government, remain the domain of elites who have acquired additional education. The second factor determining the social breadth of the use of writing is the range of functions that a script serves. The functions served are directly related to the orthography. Early forms of writing served an extremely narrow range of functions and were wholly unsuitable for others. While tokens served for simple record keeping, and early Sumerian writing was useful for a range of administrative purposes, a relatively complete script is required for writing histories, edicts, treaties, and scientific and literary works that, to be useful, must be read in the same way by all readers. Considerable scholarly controversy surrounds the question of the role of the invention of more complete or explicit scripts, such as the alphabet, in the evolution of these more specialized uses of language. If the alphabet were decisive, one could look for the basis of many of the particular features of Western culture in the invention of an alphabetic orthography. This question is far from resolved. Historically, the rise of cities coincided with the development of a script suitable for serving bureaucratic purposes. Later, the scientific and philosophical tradition that originated in Classical Greece and that prevails in the West to this day developed along with the alphabet. Many writers, including Eric Havelock, have maintained that the alphabet was a decisive factor in the cultural development of the West. Canadian communications theorist Marshall McLuhan and American scholar Walter J. Ong have claimed that the rise of literacy and the decline of orality in the later Middle Ages were fundamental to the cultural flowering known as the Renaissance.

It is perhaps characteristic of alphabet-based conceptions of literacy to draw a strict distinction between reading and interpreting. As interpretation came to be seen as interpolation into or distortion of the text, the attempt was made to write texts in such a manner as to reduce the possibility of variant interpretations. This resulted in the attempt to write texts with univocal meanings, texts that mean neither more nor less than what they say. To achieve this required the formalization of grammatical structures, the conventionalization of meanings of terms, and the invention of standard punctuation. Such textual developments were especially important for the specialized functions of science and philosophy. The distinction between meaning and interpretation fostered the idea that texts have a literal meaning, that knowledge can be completely expressed by means of such literal meanings, and that texts can be autonomous and objective. In the Western tradition, knowledge is treated as if it were an ideal text, as something that is regarded by most learners as given rather than created. These assumptions about meaning were important to both the literary and the scientific traditions that took form in western Europe in the 17th century and that continue to this day. The particular form of writing, whether logographic, syllabic, or alphabetic, is less important than the existence of some form that is general enough to serve a full range of purposes. Literate societies, whether Chinese or Sumerian, have always been esteemed by nonliterate societies, which have borrowed heavily from them. Thus, the Romans borrowed Greek literacy, and the Japanese and Koreans borrowed Chinese literacy. Once adopted and used for administrative, scientific, legal, and literary purposes, literacy altered the society that it was part of in a variety of ways. Writing allows exactly repeatable statements to be circulated widely and preserved. It allows readers to scan a text back and forth and to study, compare, and interpret at their leisure. It allows writers to deliberate over word choice and to construct lists, tables, recipes, and indexes. It fosters an objectified sense of time, a linear conception of space. It separates the message from the author and from the context in which it was written, thereby decontextualizing, or universalizing the meaning of, language. It allows the creation of new forms of verbal structure, such as the syllogism, and of numerical structures, such as the multiplication table. When writing becomes a predominant institutional and archival form, it has contributed to the replacement of myth by history and

the replacement of magic by skepticism and science. Writing has permitted the development of extensive bureaucracy, accounting, and legal systems organized on the basis of explicit rules and procedures. Writing has replaced face-to-face governance with written law and depersonalized administrative procedures. And, on the other hand, it has turned writers from scribes into authors and thereby contributed to the recognition of the importance of the thoughts of individuals and consequently to the development of individualism.

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili Hypnerotomachia Poliphili The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (The Strife of Love in a Dream), a work attributed to Dominican monk Francesco de Colonna, was first published in Venice, Italy, in 1499 by Aldus Manutius. Its text and its beautiful woodcut illustrations influenced Renaissance art and architecture. This illustration shows the books protagonist, Poliphilus, asleep under a tree. Encarta Encyclopedia The Pierpont Morgan Library/Art Resource, NY Full Size Modern publishing and bookselling in Europe began in the mid-15th century, when people began printing with movable type. The first professional printers often served as editors of the works they produced and then sold them directly to readers; they employed agents at universities to sell their books there. Anton Koberger, who in 1470 became the first printer to

establish a business in Nrnberg, had 16 shops, as well as book agents in almost every city in the Christian world. German printers Peter Schffer and Johann Fust, a partner of Johannes Gutenberg, offered their books at prices far below those charged for manuscripts. The publisher with the greatest influence on the literature and civilization of this period was Aldus Manutius of Venice, Italy. The high scholarly ideals and unselfish labors of Manutius and his immediate successors, as well as the imagination, ingenuity, and persistence of Gutenberg and Fust, led to the distribution of Greek poetry and philosophy in Europe in the late 15th century. In the organization of his printing and publishing business Manutius overcame many obstacles, such as the necessity of training Italian typesetters to set Greek texts and the delivery of books from Venice to different points of the European continent.

The Game and Playe of the Chesse The Game and Playe of the Chesse William Caxton, the first printer to produce works in English, worked at early printing presses in Bruges, Flanders (now Brugge, Belgium), and Cologne, Germany, before establishing a printing press in London, England, in 1476. This illustration is from one of the first books printed in the English language, The Game and Playe of the Chesse, Claxtons English version of a popular French work. This book was printed in about 1475 during Claxtons stay in Bruges. Encarta Encyclopedia Getty Images/Hulton Getty / Tony Stone Images Full Size Other outstanding publisher-booksellers of this period included William Caxton, who set up a printing business in Westminster, England, in 1476 and was the first to introduce books printed in the English language. Caxton published many of his own translations of Latin, French, and Dutch works. German printer Johann Froben founded a publishing establishment in Basel, Switzerland, that became noted for the artistic taste and scrupulous accuracy of the books it produced. A publishing enterprise of minor commercial importance that enormously influenced public opinion in Europe was instituted in the German town of Wittenberg in Saxony (Sachsen), in 1517, at the instigation of German religious reformers Martin Luther and Melanchthon. The pamphlets from this press, reprinted in other places by printers sympathetic to Luther, secured an extremely wide circulation.

For a time during the 16th and 17th centuries, the principal bookselling centers were a number of cities in the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands), but by the 18th century publishing companies had been established in the major cities of Europe. Some of them lasted into the 21st century. C. Book Trade in Colonial North America

Printing in the English colonies in North America dates from 1639, when Stephen Day printed the Freeman's Oath and an Almanack at Cambridge, Massachusetts. The famous Bay Psalm Book appeared the following year. Day's press turned out one title a year for the next 21 years. The Cambridge Press, as it was later called, was the principal press in the colonies until 1674, when a press started in Boston, Massachusetts. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, had a press by 1685 and New York City had one by 1693. The first press to produce a book in Canada was established in Qubec City in 1764. In many of these early presses, printers were both publishers and booksellers. Books were their first products, then newspapers, and later magazines. All three were prepared in the printshop itself, and the front of the establishment was used to sell the works that came off the press, along with various household items. This colonial pattern was repeated everywhere, as printing moved across the continent with the tide of settlement. Presses were moved westward on wagons and on rafts and small boats. Wherever the printer settled, the shop was set up to print and sell its products. Often these shops were family affairs, and many women became printers and worked alongside their husbands, sometimes carrying on alone when they were widowed. Before the American Revolution (1775-1783), printers and the books, pamphlets, and broadsides they produced became important in the organization of the growing protest against British rule. Printshops were the focal points of dissent, and the material that was printed both inspired and consolidated Microsoft Encarta 2009. 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

The earliest known journalistic effort was the Acta Diurna (Daily Events) of ancient Rome. In the 1st century BC, statesman Julius Caesar ordered these handwritten news bulletins posted each day in the Forum, a large public space. The first distributed news bulletins appeared in China around 750 AD. In the mid-15th century, wider and faster dissemination of news was made possible by the development of movable metal type, largely credited to German printer Johannes Gutenberg. At first, newspapers consisted of one sheet and often dealt with a single event. Gradually a more complex product evolved. Germany, The Netherlands, and England produced newsletters and newsbooks of varying sizes in the 16th and 17th centuries. Journals of opinion became popular in France beginning late in the 17th century. By the early 18th century, politicians had begun to realize the enormous potential of newspapers in shaping public opinion. Consequently the journalism of

the period was largely political in nature; journalism was regarded as an adjunct of politics, and each political faction had its own newspaper. During this period the great English journalists flourished, among them Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Swift, Joseph Addison, and Sir Richard Steele. Also at this time the long struggle for freedom of the press began. In the English colonies of North America, the first newspaper was Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, published in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1690; it was suppressed, and its editor, Benjamin Harris, was imprisoned after having produced the first issue. The trial of publisher John Peter Zenger in 1735 set a key precedent regarding freedom of the press in America more than 50 years before the First Amendment to the United States Constitution would secure it. Zenger was acquitted of charges of criminal libel stemming from articles he printed that were critical of the colonial authorities in New York, his defense being that his reports were factual. Provisions for censorship of the press were, however, included in the Alien and Sedition Acts, passed in 1798. After provoking a great deal of opposition, these acts were allowed to expire. See also Trial of John Peter Zenger. Journalism in the 19th century became more powerful due to the mass production methods arising from the Industrial Revolution and to the general literacy promoted by public education. The large numbers of people who had learned how to read demanded reading matter, and new printing machinery made it possible to produce this inexpensively and in great quantities. In the United States, for example, publishers Joseph Pulitzer, Edward Wyllis Scripps, and William Randolph Hearst established newspapers appealing to the growing populations of the big cities. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, news agencies exploited the invention of the telegraph by using it for the rapid gathering and dissemination of world news via wire services. These services included Reuters, based in England; the Associated Press and United Press (later United Press International), based in the United States; and the Canadian Press, in Canada. At the same time, new popular magazines were made possible by new technologies, improved transportation, low postal rates, and the emergence of national brands of consumer goods that required national media in which to advertise. The Ladies' Home Journal, founded by Cyrus H. K. Curtis in 1883, soon had a circulation of almost a milliona prodigious figure for that day. In 1897 Curtis bought for $1,000 the old Saturday Evening Post, which rapidly achieved a circulation in the millions. Numerous other magazines appealing to the general reader appeared in the 20th century, including Reader's Digest, Collier's, Life, and Look. Over time, some general magazines became unprofitable and ceased publication when they lost advertising to television and to more specialized magazines, such as Sports Illustrated and TV Guide. The newsmagazines Time, Newsweek, Macleans, and U.S. News & World Report have continued to occupy an important place in journalism, as have The Ladies Home Journal and other so-called women's service magazines. In the early 20th century two new forms of news media appeared: newsreels and radio. By the 1920s, newsreels in the United States alone reached about 40 million people a week in about 18,000 film theaters, but they were displaced by television in the 1950s. Radio news survived more successfully. Stations in the United States and Canada started to report current events in the 1920s, borrowing most of their information from local newspapers. They soon developed their own newsgathering facilities.

By World War II (1939-1945), radio had amassed a huge audience. American president Franklin Delano Roosevelt appealed to his nation through his fireside chats, and radio was usually the first to bring reports on the war to the public. Popular radio reporters and commentators were heard by millions of people. Television later attracted much of radios audience, but radio has retained a loyal following for music, news, and talk shows. Television became commercially viable in the 1950s, and by the 1970s nearly every household that wanted a television had one. (In 2000 there were 835 televisions for every 1,000 people in the United States and 710 per 1,000 in Canada.) Network evening newscasts, originally 15 minutes long, were extended to 30 minutes, and local news broadcasts in major cities expanded to an hour or more. Network newscasters gradually became national figures. Since the introduction in 1951 of the first major documentary series, See It Now, featuring commentator Edward R. Murrow, television documentaries and video newsmagazines such as 60 Minutes have become important news sources. The Cable News Network (CNN), operating in a news-only format 24 hours a day, reached 77 million U.S. and Canadian households by 2000, and its CNN International broadcasts were relayed by satellite to more than 200 other countries. Microsoft Encarta 2009. 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

The history of publishing is characterized by a close interplay of technical innovation and social change, each promoting the other. Publishing as it is known today depends on a series of three major inventionswriting, paper, and printingand one crucial social developmentthe spread of literacy. Before the invention of writing, perhaps by the Sumerians in the 4th millennium BC, information could be spread only by word of mouth, with all the accompanying limitations of place and time. Writing was originally regarded not as a means of disseminating information but as a way to fix religious formulations or to secure codes of law, genealogies, and other socially important matters, which had previously been committed to memory. Publishing could begin only after the monopoly of letters, often held by a priestly caste, had been broken, probably in connection with the development of the value of writing in commerce. Scripts of various kinds came to be used throughout most of the ancient world for proclamations, correspondence, transactions, and records; but book production was confined largely to religious centres of learning, as it would be again later in medieval Europe. Only in Hellenistic Greece, in Rome, and in China, where there were essentially nontheocratic societies, does there seem to have been any publishing in the modern sensei.e., a copying industry supplying a lay readership. The invention of printing transformed the possibilities of the written word. Printing seems to have been first invented in China in the 6th century AD in the form of block printing. An earlier version may have been developed at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC, but, if so, it soon fell into disuse. The Chinese invented movable type in the 11th century AD but did not fully exploit it. Other Chinese inventions, including paper (AD 105), were passed on to Europe by the Arabs but not, it seems, printing. The reason may well lie in Arab insistence on hand copying of the Qurn (Arabic printing of the Qurn does not appear to have been officially sanctioned until 1825). The invention of printing in Europe is usually attributed to Johannes Gutenberg in Germany about 144050, although block printing had been carried out from about 1400. Gutenberg's achievement was not a single invention but a whole new

craft involving movable metal type, ink, paper, and press. In less than 50 years it had been carried through most of Europe, largely by German printers. Printing in Europe is inseparable from the Renaissance and Reformation. It grew from the climate and needs of the first, and it fought in the battles of the second. It has been at the heart of the expanding intellectual movement of the past 500 years. Although printing was thought of at first merely as a means of avoiding copying errors, its possibilities for massproducing written matter soon became evident. In 1498, for instance, 18,000 letters of indulgence were printed at Barcelona. The market for books was still small, but literacy had spread beyond the clergy and had reached the emerging middle classes. The church, the state, universities, reformers, and radicals were all quick to use the press. Not surprisingly, every kind of attempt was made to control and regulate such a dangerous new mode of communication. Freedom of the press was pursued and attacked for the next three centuries; but by the end of the 18th century a large measure of freedom had been won in western Europe and North America, and a wide range of printed matter was in circulation. The mechanization of printing in the 19th century and its further development in the 20th, which went hand in hand with increasing literacy and rising standards of education, finally brought the printed word to its powerful position as a means of influencing minds and, hence, societies. The functions peculiar to the publisheri.e., selecting, editing, and designing the material; arranging its production and distribution; and bearing the financial risk or the responsibility for the whole operationoften merged in the past with those of the author, the printer, or the bookseller. With increasing specialization, however, publishing became, certainly by the 19th century, an increasingly distinct occupation. Most modern Western publishers purchase printing services in the open market, solicit manuscripts from authors, and distribute their wares to purchasers through shops, mail order, or direct sales. Published matter falls into two main categories, periodical and nonperiodical; i.e., publications that appear at more or less regular intervals and are members of a series and those that appear on single occasions (except for reissues of essentially the same material). Of the nonperiodical publications, books constitute by far the largest class; they are also, in one form or another, the oldest of all types of publication and go back to the earliest civilizations. In giving permanence to man's thoughts and records of his achievements, they answer a deep human need. Not every published book is of lasting value; but a nation's books, taken as a whole and winnowed out by the passing years, can be said to be its main cultural storehouse. Conquerors or usurpers wishing to destroy a people's heritage have often burned its books, as did Shih Huang-ti in China in 213 BC, the Spaniards in Mexico in 1520, and the Nazis in the 1930s. There is no wholly satisfactory definition of a book, as the word covers a variety of publications (for example, some publications that appear periodically, such as The World Almanac and Book of Facts, may be considered books). For statistical purposes, however, the United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization defines a book as a nonperiodical printed publication of at least 49 pages excluding covers. Periodical publications may be further divided into two main classes, newspapers and magazines. Though the boundary between them is not sharpthere are magazines devoted to news, and many newspapers have magazine featurestheir differences of format, tempo, and

function are sufficiently marked: the newspaper (daily or weekly) usually has large, loose pages, a high degree of immediacy, and miscellaneous contents; whereas the magazine (weekly, monthly, or quarterly) has smaller pages, is usually fastened together and sometimes bound, and is less urgent in tone and more specialized in content. Both sprang up after the invention of printing, but both have shown a phenomenal rate of growth to meet the demand for quick information and regular entertainment. Newspapers have long been by far the most widely read published matter; the democratizing process of the 19th and 20th centuries would be unthinkable without them. Magazines, close behind newspapers both historically and in terms of readership, rapidly branched out from their learned origins into periodicals of amusement. Today there is probably not a single interest, frivolous or serious, of man, woman, or child, that is not catered to by a magazine. There are, of course, many other types of publications besides books, newspapers, and magazines. In many cases the same principles of publishing apply, and it is only the nature of the product and the technicalities of its manufacture that are different. There is, for instance, the important business of map and atlas publishing. Another important field is music publishing, which produces a great variety of material, from complete symphonic scores to sheet music of the latest popular hit. A further range of activities might be grouped under the term utility publishing; i.e., the issuing of calendars, diaries, timetables, ready reckoners, guide books, and all manner of informational or directional material, not to mention postcards and greeting cards. A great deal of occasional publishing, of pamphlets and booklets, is done by organizations to further particular aims or to spread particular views; e.g., by churches, religious gro

traditionally, a technique for applying under pressure a certain quantity of colouring agent onto a specified surface to form a body of text or an illustration. Certain modern processes for reproducing texts and illustrations, however, are no longer dependent on the mechanical concept of pressure or even on the material concept of colouring agent. Because these processes represent an important development that may ultimately replace the other processes, printing should probably now be defined as any of several techniques for reproducing texts and illustrations, in black and in colour, on a durable surface and in a desired number of identical copies. There is no reason why this broad definition should not be retained, for the whole history of printing is a progression away from those things that originally characterized it: lead, ink, and the press. It is also true that, after five centuries during which printing has maintained a quasimonopoly of the transmission or storage of information, this role is being seriously challenged by new audiovisual and information media. Printing, by the very magnitude of its contribution to the multiplication of knowledge, has helped engender radio, television, film, microfilm, tape recording, and other rival techniques. Nevertheless, its own field remains immense. Printing is used not merely for books and newspapers but also for textiles, plates, wallpaper, packaging, and billboards. It has even been used to manufacture miniature electronic circuits. The invention of printing at the dawn of the age of the great discoveries was in part a response and in part a stimulus to the movement that, by transforming the economic, social, and ideological relations of civilization, would usher in the modern world. The economic world was marked by the high level of production and exchange attained by the Italian

republics, as well as by the commercial upsurge of the Hanseatic League and the Flemish cities; social relations were marked by the decline of the landed aristocracy and the rise of the urban mercantile bourgeoisie; and the world of ideas reflected the aspirations of this bourgeoisie for a political role that would allow it to fulfill its economic ambitions. Ideas were affected by the religious crisis that would lead to the Protestant Reformation. The first major role of the printed book was to spread literacy and then general knowledge among the new economic powers of society. In the beginning it was scorned by the princes. It is significant that the contents of the first books were often devoted to literary and scientific works as well as to religious texts, though printing was used to ensure the broad dissemination of religious material, first Catholic and, shortly, Protestant. There is a material explanation for the fact that printing developed in Europe in the 15th century rather than in the Far East, even though the principle on which it is based had been known in the Orient long before. European writing was based on an alphabet composed of a limited number of abstract symbols. This simplifies the problems involved in developing techniques for the use of movable type manufactured in series. Chinese handwriting, with its vast number of ideograms requiring some 80,000 symbols, lends itself only poorly to the requirements of a typography. Partly for this reason, the unquestionably advanced Oriental civilization, of which the richness of their writing was evidence, underwent a slowing down of its evolution in comparison with the formerly more backward Western civilizations. Printing participated in and gave impetus to the growth and accumulation of knowledge. In each succeeding era there were more people who were able to assimilate the knowledge handed to them and to augment it with their own contribution. From Diderot's encyclopaedia to the present profusion of publications printed throughout the world, there has been a constant acceleration of change, a process highlighted by the Industrial Revolution at the beginning of the 19th century and the scientific and technical revolution of the 20th. At the same time, printing has facilitated the spread of ideas that have helped to shape alterations in social relations made possible by industrial development and economic transformations. By means of books, pamphlets, and the press, information of all kinds has reached all levels of society in most countries. In view of the contemporary competition over some of its traditional functions, it has been suggested by some observers that printing is destined to disappear. On the other hand, this point of view has been condemned as unrealistic by those who argue that information in printed form offers particular advantages different from those of other audio or visual media. Radio scripts and television pictures report facts immediately but only fleetingly, while printed texts and documents, though they require a longer time to be produced, are permanently available and so permit reflection. Though films, microfilms, punch cards, punch tapes, tape recordings, holograms, and other devices preserve a large volume of information in small space, the information on them is available to human senses only through apparatus such as enlargers, readers, and amplifiers. Print, on the other hand, is directly accessible, a fact that may explain why the most common accessory to electronic calculators is a mechanism to print out the results of their operations in plain language. Far from being fated to disappear, printing seems more likely to experience an evolution marked by its increasingly close association with these various other means by which information is placed at the disposal of humankind.

History of printing

Origins in China

By the end of the 2nd century AD, the Chinese apparently had discovered printing; certainly they then had at their disposal the three elements necessary for printing: (1) paper, the techniques for the manufacture of which they had known for several decades; (2) ink, whose basic formula they had known for 25 centuries; and (3) surfaces bearing texts carved in relief. Some of the texts were classics of Buddhist thought inscribed on marble pillars, to which pilgrims applied sheets of damp paper, daubing the surface with ink so that the parts that stood out in relief showed up; some were religious seals used to transfer pictures and texts of prayers to paper. It was probably this use of seals that led in the 4th or 5th century to the development of ink of a good consistency for printing. A substitute for these two kinds of surfaces, the marble pillars and the seals, that was more practical with regard both to manageability and to size, appeared perhaps by the 6th century in the wood block. First, the text was written in ink on a sheet of fine paper; then the written side of the sheet was applied to the smooth surface of a block of wood, coated with a rice paste that retained the ink of the text; third, an engraver cut away the uninked areas so that the text stood out in relief and in reverse. To make a print, the wood block was inked with a paintbrush, a sheet of paper spread on it, and the back of the sheet rubbed with a brush. Only one side of the sheet could be printed. The oldest known printed works were made by this technique: in Japan about 764770, Buddhist incantations ordered by Empress Shtoku; in China in 868, the first known book, the Diamond Stra; and, beginning in 932, a collection of Chinese classics in 130 volumes, at the initiative of Fong Tao, a Chinese minister.

Invention of movable type (11th century)

About 104148 a Chinese alchemist named Pi Sheng appears to have conceived of movable type made of an amalgam of clay and glue hardened by baking. He composed texts by placing the types side by side on an iron plate coated with a mixture of resin, wax, and paper ash. Gently heating this plate and then letting the plate cool solidified the type. Once the impression had been made, the type could be detached by reheating the plate. It would thus appear that Pi Sheng had found an overall solution to the many problems of typography: the manufacture, the assembling, and the recovery of indefinitely reusable type. In about 1313 a magistrate named Wang Chen seems to have had a craftsman carve more than 60,000 characters on movable wooden blocks so that a treatise on the history of technology could be published. To him is also attributed the invention of horizontal compartmented cases that revolved about a vertical axis to permit easier handling of the type. But Wang Chen's innovation, like that of Pi Sheng, was not followed up in China.

In Korea, on the contrary, typography, which had appeared by the first half of the 13th century, was extensively developed under the stimulus of King Htai Tjong, who, in 1403, ordered the first set of 100,000 pieces of type to be cast in bronze. Nine other fonts followed from then to 1516; two of them were made in 1420 and 1434, before Europe in its turn discovered typography.

Transmission of paper to Europe (12th century)

Paper, the production of which was known only to the Chinese, followed the caravan routes of Central Asia to the markets at Samarkand, whence it was distributed as a commodity across the entire Arab world. The transmission of the techniques of papermaking appears to have followed the same route; Chinese taken prisoner at the Battle of Talas, near Samarkand, in 751 gave the secret to the Arabs. Paper mills proliferated from the end of the 8th century to the 13th century, from Baghdad and then on to Spain, then under Arab domination. Paper first penetrated Europe as a commodity from the 12th century onward through Italian ports that had active commercial relations with the Arab world and also, doubtless, by the overland route from Spain to France. Papermaking techniques apparently were rediscovered by Europeans through an examination of the material from which the imported commodity was made; possibly the secret was brought back in the mid-13th century by returning crusaders or merchants in the Eastern trade. Papermaking centres grew up in Italy after 1275 and in France and Germany in the course of the 14th century. But knowledge of the typographic process does not seem to have succeeded, as papermaking techniques had, in reaching Europe from China. It would seem that typography was assimilated by the Uighurs who lived on the borders of Mongolia and Turkistan, since a set of Uighur typefaces, carved on wooden cubes, has been found that date from the early 14th century. It would be surprising if the Uighurs, a nomadic people usually considered to have been the educators of other Turco-Mongolian peoples, had not spread the knowledge of typography as far as Egypt. There it may have encountered an obstacle to its progress toward Europe, namely, that, even though the Islmic religion had accepted paper in order to record the word of Allah, it may have refused to permit the word of Allah to be reproduced by artificial means.

The invention of printing

Thus, the essential elements of the printing process collected slowly in western Europe, where a favourable cultural and economic climate had formed.

Xylography

Xylography, the art of printing from wood carving, the existence and importance of which in China was never suspected by Marco Polo, appeared in Europe no earlier than the last quarter

of the 14th century, spontaneously and presumably as a result of the use of paper. It had been observed that paper was better suited than rough-surfaced parchment for making the impressions from wood reliefs that manuscript copyists used to reproduce the outline of ornamental initial capital letters. The process was extended to the making of religious pictures. These at first appeared alone and later were accompanied by a brief text. As engravers became more skillful, the text finally became more important than the illustration, and in the first half of the 15th century small, genuine books of several pages, religious works or compendiums of Latin grammar by Aelius Donatus and called donats, were published by a method identical to that of the Chinese. Given the Western alphabet, it would seem reasonable that the next step taken might have been to carve blocks of writing that, instead of texts, would simply contain a large number of letters of the alphabet; such blocks could then be cut up into type, usable and reusable. It is possible that experiments were in fact made along these lines, perhaps in 1423 or 1437 by a Dutchman from Haarlem, Laurens Janszoon, known as Coster. The encouraging results obtained with large type demonstrated the validity of the idea of typographic composition. But the results were disappointing with regard to type destined for use for text of the usual size. The letters of the roman alphabet were smaller than Chinese ideograms, and cutting them from wood was a delicate operation. Moreover, type made in this way was fragile, and it wore out at least as quickly as blocks carved with a whole text. Further, since the letters were individually carved, no two copies of the same letter were identical any more than when the text was engraved directly on a wood block. The process, thus, represented no advance in ease of production, durability, or quality.

Metallographic printing (1430?)

Metallographic impression is more likely to turn out to be the direct ancestor of typography, although the record is far from clear. Several medieval craft guilds, notably the metal founders, the die-cutters, and goldsmiths and silversmiths, were familiar with the technique of using dies. Masters of this technique apparently realized that it could be applied to a process that would enable texts to be set in relief more quickly than by carving wood blocks, probably in three steps: (1) a set of dies, each bearing a letter of the alphabet, was engraved in brass or bronze; (2) using these dies, the text was struck letter by letter to form a mold on the surface of a matrix of clay or of a soft metal such as lead; (3) lead was then poured over the surface to form a small plate that, once hardened, would bear the text in relief. The theoretical advantages of this process were that only one engraving per letter, that of the die, was required to make the letter as often as desired, and any two examples of the same letter would be identical, since they came from a single die; sinking the matrix and casting the lead were rapid operations; the lead had better durability than wood; and by casting several plates from the same matrix the number of copies printed could be rapidly increased. Metallographic printing appears to have been practiced in Holland around 1430 and next in the Rhineland. Gutenberg used it in Strassburg (now Strasbourg, France) between 1434 and 1439.

But the experiments were not followed up because of problems created by the cast plates. It was difficult to strike each letter die with the same force and to keep a regular alignment, and, worse, each strike tended to deform the adjacent letter. It may well be that the major value of metallographic printing was that it associated the idea of the die, the matrix, and cast lead.

The invention of typographyGutenberg (1450?)

This association of die, matrix, and lead in the production of durable typefaces in large numbers and with each letter strictly identical, was one of the two necessary elements in the invention of typographic printing in Europe. The second necessary element was the concept of the printing press itself, an idea that had never been conceived in the Far East. Johannes Gutenberg is generally credited with the simultaneous discovery of both these elements, though there is some uncertainty about it, and disputes arose early to cloud the honour. It is true that his signature does not appear on any printed work. If masterpieces such as the Forty-two-Line Bible of 1455 rather than the imperfect products of a nascent typography such as the donats of 1445 or the Astronomic Calendar of 144748 are attributed to him, this is because of deduction and historical and technical cross-checking. The basic assumption is that, since Gutenberg was by profession a silversmith, he would have retained the role of designer in an association set up at Mainz, Germany, with the businessman Johann Fust and Fust's future son-in-law the calligrapher Peter Schffer. The assumption is based solely on the interpretation of obscure aspects of a lawsuit that Gutenberg lost against his associates in 1455. Apart from chronicles, all published after his death, that attributed the invention of printing to him, probably the most convincing argument in favour of Gutenberg comes from his chief detractor, Johann Schffer, the son of Peter Schffer and grandson of Johann Fust. Though Schffer claimed from 1509 on that the invention was solely his father's and grandfather's, the fact is that in 1505 he had written in a preface to an edition of Livy that the admirable art of typography was invented by the ingenious Johan Gutenberg at Mainz in 1450. It is assumed that he had inherited this certainty from his father, and it is hard to see how a new element could have persuaded him to the contrary after 1505, since Johann Fust died in 1466 and Peter Schffer in 1502. The first pieces of type appear to have been made in the following steps: a letter die was carved in a soft metal such as brass or bronze; lead was poured around the die to form a matrix and a mold into which an alloy, which was to form the type itself, was poured. Spectroscopic analyses of early type pieces reveal that the alloy used was a mix of lead, tin, and antimonythe same components used today: tin, because lead alone would have oxidized rapidly and in casting would have deteriorated the lead mold matrices; antimony, because lead and tin alone would have lacked durability. It was probably Peter Schffer who, around 1475, thought of replacing the soft-metal dies with steel dies, in order to produce copper letter matrices that would be reliably identical.

Until the middle of the 19th century, type generally continued to be made by craftsmen in this way. The typographer's work was from the beginning characterized by four operations: (1) taking the type pieces letter by letter from a typecase; (2) arranging them side by side in a composing stick, a strip of wood with corners, held in the hand; (3) justifying the line; that is to say, spacing the letters in each line out to a uniform length by using little blank pieces of lead between words; and (4), after printing, distributing the type, letter by letter, back in the compartments of the typecase.

The Gutenberg press

Documents of the period, including those relating to a 1439 lawsuit in connection with Gutenberg's activities at Strassburg, leave scarcely any doubt that the press has been used since the beginning of printing. Perhaps the printing press was first just a simple adaptation of the binding press, with a fixed, level lower surface (the bed) and a movable, level upper surface (the platen), moved vertically by means of a small bar on a worm screw. The composed type, after being locked by ligatures or screwed tight into a right metal frame (the form), was inked, covered with a sheet of paper to be printed, and then the whole pressed in the vise formed by the two surfaces. This process was superior to the brushing technique used in wood-block printing in Europe and China because it was possible to obtain a sharp impression and to print both sides of a sheet. Nevertheless, there were deficiencies: it was difficult to pass the leather pad used for inking between the platen and the form; and, since several turns of the screw were necessary to exert the required pressure, the bar had to be removed and replaced several times to raise the platen sufficiently to insert the sheet of paper. It is generally thought that the printing press acquired its principal functional characteristics very early, probably before 1470. The first of these may have been the mobile bed, either on runners or on a sliding mechanism, that permitted the form to be withdrawn and inked after each sheet was printed. Next, the single thread of the worm screw was replaced with three or four parallel threads with a sharply inclined pitch so that the platen could be raised by a slight movement of the bar. This resulted in a decrease in the pressure exerted by the platen, which was corrected by breaking up the printing operation so that the form was pushed under the press by the movable bed so that first one half and then the other half of the form was utilized. This was the principle of printing in two turns, which would remain in use for three centuries.

Improvements after Gutenberg

Several of the many improvements in the screw printing press over the next 350 years were of significance. About 1550 the wooden screw was replaced by iron. Twenty years later,

innovators added a double-hinged chase consisting of a frisket, a piece of parchment cut out to expose only the actual text itself and so to prevent ink spotting the nonprinted areas of the paper, and a tympan, a layer of a soft, thick fabric to improve the regularity of the pressure despite irregularities in the height of the type. About 1620 Willem Janszoon Blaeu in Amsterdam added a counterweight to the pressure bar in order to make the platen rise automatically; this was the so-called Dutch press, a copy of which was to be the first press introduced into North America, by Stephen Daye at Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1639. About 1790 an English scientist and inventor, William Nicholson, devised a method of inking using a cylinder covered with leather (later with a composition of gelatin, glue, and molasses), the first introduction of rotary movement into the printing process.

The metal press (1795)

The first all-metal press was constructed in England in about 1795. Some years later a mechanic in the United States built a metal press in which the action of the screw was replaced by that of a series of metal joints. This was the Columbian, which was followed by the Washington of Samuel Rust, the apogee of the screw press inherited from Gutenberg; its printing capacity was about 250 copies an hour.

Stereotypy and stereography (late 18th century)

An increasing demand for printed matter stimulated the search for greater speed and volume. The concepts of stereotypy and stereography were explored. Stereotypy, used with notable success around 1790 in Paris, consisted in making an impression on text blocks of type in clay or soft metal in order to make lead molds of the whole. The stereotyped plates thus obtained made it economically possible to print the same text on several presses at the same time. The plates left the pieces of type in the form immediately available for further use and thus increased the rate at which they could be recycled. A variation of stereotypy was the application, after 1848, of galvanoplastic metallization, in which process plates of thin metal lined with a base of lead alloy were made by electrolytic deposition of a coat of copper on a wax mold of the typeform. Stereography aimed at bypassing the composition of the type in making the mold. Attempts to perfect the old metallographic method of preparing a clay matrix by stamping with dies brought no better results. In 1797 a variation was tried in which sets of copper matrices of each letter were made in large numbers. The matrices were then assembled according to the wording of the text, so that they covered the whole surface of the bottom of a mold in which the lead plate was then cast. Once the cast had been made, the matrices were available for further use.

Koenig's mechanical press (early 19th century)

The prospect of using steam power in printing prompted research into means by which the different operations of the printing process could be joined together in a single cycle.

Friedrich Koenig's mechanical platen press, 1811.

In 1803, in Germany, Friedrich Koenig envisaged a press in which the raising and lowering of the platen, the to-and-fro movement of the bed, and the inking of the form by a series of rollers were controlled by a system of gear wheels. Early trials in London in 1811 were unsuccessful.

Presses with a mechanized platen produced satisfactory results after the perfection, in the United States, of the Liberty (1857), in which the action of a pedal caused the platen to be held against the bed by the arms of a clamp. Though Nicholson very early took out patents for a printing process using a cylinder to which the composed type pieces were attached, he was never able to develop the necessary technology involved. The cylinder was in fact the most logical geometric form to use in a cyclical process. It was also the one capable of providing the greatest output. Given an equal amount of energy, the pressure exerted by a platen had to be spread over the whole of the surface to be printed, whereas the pressure exerted by a cylinder could be concentrated on the strip of surface actually in contact with the cylinder at any one instant. A limited demonstration of the efficiency of the cylinder had been made as early as 1784 on a French press for books for the blind.

The first stop-cylinder printing machine, 1811, built by Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Bauer.

In 1811 Koenig and an associate, Andreas Bauer, in another approach to the rotary principle, designed a cylinder as a platen bearing the sheet of paper and pressing it against the typeform placed on a flatbed that moved to and fro. The rotation of the cylinder was linked to the forward movement of the bed but was disengaged when the bed moved back to go under the inking rollers.

In 1814 the first stop-cylinder press of this kind to be driven by a steam engine was put into service at the Times of London. It had two cylinders, which revolved one after the other according to the to-and-fro motion of the bed so as to double the number of copies printed; a speed of 1,100 sheets per hour was achieved. In 1818 Koenig and Bauer designed a double press in which a sheet of paper printed on one side under one of the cylinders passed to the other cylinder, to be printed on the other side. This was called a perfecting machine. In 1824 William Church added grippers to the cylinder to pick up, hold, and then automatically release the sheet of paper. The to-and-fro movement of the bed that was retained in these early cylinder presses constituted an element of discontinuity; to make the cycle completely continuous, not only would the platen have to be cylindrical but the typeform also. In 1844 Richard Hoe in the United States patented his type revolving press, the first rotary to be based on this principle. It consisted of a cylinder of large diameter, bearing columns of type bracketed together on its outer surface; pressure was provided by several small cylinders, each of which was fed sheets of paper by hand. This system gave speeds of more than 8,000 copies per hour; its only drawback was its fragility; faulty locking up of the forms caused the type to fall out of the cylinder. This defect was remedied by applying stereotypy to the production; that is, forming curved plates by making an impression of the typeform on strong pasteboard, the flong, or mat, which was fixed against the inside surface of a rounded mold, which was injected with lead alloy. In France, from 1849 onward, experiments were conducted with this process; it was regularly used in London by the Times from 1856 onward and after 1858 was in general use. But feeding the press with paper still remained outside the mechanized cycle. Mechanization of this step was accomplished by the use of a continuous roll of paper supplied on reels instead of sheets. Techniques for producing paper in a continuous roll had been known since the beginning of the century. The first roll-fed rotary press was made by William Bullock of the United States in 1865. It included a device for cutting the paper after printing and produced 12,000 complete newspapers per hour. Automatic folding devices, the first of which were designed by Bullock and Hoe, were incorporated into rotaries after 1870. Later, numerous other types of curved stereotype plates were used on rotary presses. These included electrotype plates that are curved before being backed; rubber or plastic plates made by molding or by a photomechanical process; and metal wraparound plates made by photoengraving or electronic engraving.

Attempts to mechanize composition (mid-19th century)