Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Compliment Responses

Compliment Responses

Uploaded by

Manuel ArriojaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Compliment Responses

Compliment Responses

Uploaded by

Manuel ArriojaCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSN 1798-4769

Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 121-129, March 2010

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland.

doi:10.4304/jltr.1.2.121-129

A Study of Pragmatic Transfer in Compliment

Response Strategies by Chinese Learners of

English

Jiemin Bu

Foreign Languages School, Zhejiang Guangsha College of Applied Construction, Dongyang, Zhejiang, China

Email:bujiemin@126.com

Abstract—For decades, the first language culture influence on second language acquisition has fascinated

researchers. Based on Giao Quynh Tran’s classification, this paper uses the naturalized role-play to conduct a

research on pragmatic transfer in compliment responses strategies by Chinese learners of English. The data

collected through the naturalized role-play are analyzed quantitatively between the Chinese learner of English

and native English groups, and between the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups. The

research has concluded that the strategies which have the statistically significant differences in terms of

compliment response strategy use between the Chinese learner of English and native English groups are those

strategies which have the close similarities in the respect of compliment response strategy use between the

Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups. This conclusion has proven that there is, to some extent,

pragmatic transfer in compliment response strategies by Chinese learners of English.

Index Terms—interlanguage pragmatics, pragmatic transfer, compliment response strategies, Chinese learner

of English

I. INTRODUCTION

Pragmatic transfer can be defined as the influence exerted by learners’ pragmatic knowledge of native language and

culture on their comprehension, production and learning of L2 pragmatic information (Kasper, 1992:207). Here

pragmatic knowledge is to be understood as referring to “ a particular component of language users’ general

communicative knowledge, Viz. knowledge of how verbal acts are understood and performed in accordance with a

speaker’s intention under contextual and discoursal constraints” ( Faerch & Kasper, 1984:214). As we can see, Kasper’s

approach to pragmatic transfer is (1) process-oriented; (2) allows the study of transfer in learning and in communication;

and (3) is comprehensive, in the sense that she talks of “influence” without explicit mention of the types of influence

referred to. However, in her study she gives examples of pragmatic transfer. Since an evidence of pragmatic transfer is

most likely to be identified in the production of English by Chinese learners of English, the focus of this paper is on

pragmatic transfer from Chinese into English.

Transfer of Chinese language pragmatic features into English may result in communication failure between Chinese

and native English speakers, which can be attributed to personality of Chinese learners of English and negatively

influence their presentation of self in English. In fact, such pragmatic failure can result in not only native English

speakers’ misinterpretation and misunderstanding of linguistic behavior of Chinese speakers of English, but also culture

shock of Chinese speakers of English in the English culture and society. Therefore, as Kasper said: “In the real world,

pragmatic transfer matters more, or at least obviously, than relative clause structure or word order” (Kasper, 1992:205).

It is also in pragmatics that the influence of the learners’ native culture affects their foreign language use. Moreover, the

learners’ pragmatic knowledge in foreign language use does not automatically increase with the increase of their

grammatical competence. It is thus necessary to investigate pragmatic transfer and provide the learners with knowledge

of this phenomenon in order to prevent them from experiencing its possible pragmatic transfer.

Despite many researches have been made on the nature of pragmatic transfer, it is still not fully understand. There has

been “highly diverse evidence for transfer” (Odlin, 2003: 437). Previous research findings about pragmatic transfer

have diverged as to whether transfer exists in the learners’ L2 use (See Tran, 2003d for a review). What is transferred

into L2 communicative act performance also requires further investigation. The question is particularly appealing when

it addresses pragmatic transfer from such an understudied L1 in interlanguage pragmatics as Chinese. Therefore, this

paper aims to explore pragmatic transfer in responding to compliments in Chinese-English interlanguage pragmatics

and shed new light on the unsettled literature on pragmatic transfer in replying to compliments.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW OF PREVIOUS RESEARCHES ON PRAGMATIC TRANSFER IN RESPONDING TO COMPLIMENTS

Pragmatic transfer is likely to occur when L1 and L2 cultural norms differ noticeably. There are some observable

differences in Chinese and English compliment responses. In Chinese culture, people often respond to compliments

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

122 JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH

negatively or reject the compliments to show modesty. In English, a simple compliment response — “thank you” — is

preferred as described in Johnson’s etiquette book (1979). The preference for a “thank you” in replying to compliments

is demonstrated in American English (Barnlund and Araki, 1985; Herbert, 1986, 1989; Knapp et al., 1984; Saito and

Beecken, 1997), British English (Herbert, 1986), New Zealand English (Holmes, 1986) and Australian English

(Soenarso, 1988). Specifically, the percentages of acceptances out of the total number of compliment response studied

were 66% versus 88% for Americans and South Africans (Herbert, 1989), 61% for New Zealanders (Holmes, 1986) and

58% for Americans (Chen, 1993). Therefore, although there might be exceptions, Herbert’s (1989) generalization about

English compliment responses apparently holds true: “Virtually all speakers of English, when questioned on this matter

in general (e.g. “What does one say after being complimented?”) or particular (e.g. “What would you say if someone

admired your shirt?”) terms, agree that the correct response is thank you.” (Herbert, 1989: 5).

Previous studies have also been made on pragmatic transfer of certain compliment response strategies in the western

countries. Saito and Beecken (1997) find that in the interlanguage of American learners of Japanese, there is pragmatic

transfer of certain compliment strategy strategies, (e.g. nonuse of avoidance). Baba (1996, 1999) shows that in

performing the communicative act of responding to compliments in the L2, both Japanese learners of English, and

American learners of Japanese, transfer their L1 pragmatic norms, especially in the family category, using their L1

responding strategies. In the self variable, however, American learners of Japanese did not transfer their positive

strategy in responding to compliments. Accordingly, interlanguage pragmatics studies in compliment responses present

contradictory results concerning pragmatic transfer. Such a contradiction generated this study. This paper investigates

pragmatic transfer from Chinese into English in compliment responses by Chinese learners of English because there

have been no existing cross-cultural pragmatic studies of native Chinese speakers’ English compliment responses.

Pragmatic transfer in compliment responses has seldom been investigated in Chinese- English interlanguage pragmatics.

As little is known about Chinese communicative act realization in general and compliment responses in particular in

English, still less an analysis of pragmatic transfer of compliment responses in Chinese-English interlanguage

pragmatics, this study aims to contribute to the literature of interlanguage pragmatics about compliment responses in

English by Chinese learners of English.

III. RESEARCH DESIGN

A. Research Questions

This paper attempts to answer the following two questions:

① Is there pragmatic transfer in the communicative act of responding to compliments in English by Chinese learners

of English?

②If there is a transfer, what is transferred?

The first research question is answered through the investigation of the following two assumptions:

①There are significant differences in strategy use in responding to compliments by native English speakers and by

Chinese learners of English as a foreign language.

②These differences can be explained by the similarities in strategy use in responding to compliments by Chinese

learners of English as a foreign language and by native Chinese speakers.

If these two assumptions are confirmed, a positive answer can be offered to the first research question. Because it is

impossible to answer the question: “Is there pragmatic transfer?” without knowing “What is transferred?”, these

questions are considered and answered simultaneously in data analysis.

B. Subjects

There are thirty subjects who consist of ten native English speakers, ten Chinese learners of English and ten native

Chinese speakers. All of them were university students, ranging in age from nineteen to twenty years old. So they show

homogeneity in terms of age, education and profession. All subjects give consent for their data to be used for this

research purpose by signing the consent form prior to data collection.

C. Instruments

In this study, the naturalized role-play is a data collection tool providing the corpus of data for analysis. The concept

of “the naturalized role-play” is proposed by Giao Quynh Tran in 2003 (Giao Quynh Tran,2003b) At the core of the

naturalized role-play is the idea of eliciting spontaneous data in controlled settings. In the naturalized role-play, subjects

are aware of being observed and studied in the whole procedure but are not aware of being observed in the moments

when they provide spontaneous data on a communicative act in focus. In order to realize this notion, the researcher

directs the subjects’ attention to a number of tasks that they perform during the role-play. These tasks are not relevant to

the communicative act in focus and their function is to distract the subjects’ attention from the research focus. As

interaction proceeds and when the subjects are absorbed in the given tasks, the researcher will lead the conversation to

the point when the subjects produce the communicative act in focus spontaneously without being aware that the data

they produce in these instances is the focus of research. The process of the naturalized role-play is demonstrated in the

situational description (see the appendix). In order to avoid native Chinese speakers’ misunderstanding of what they are

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 123

required to do in the naturalized role-play, the description of the naturalized role-play situations and the cards given to

them are translated into Chinese. In the present study, each subject participating in the naturalized role-play produces

four responses to compliments on skill, possession, appearance and clothing. The total number of compliment responses

collected is forty compliment responses in English by native English speakers, forty compliment responses in Chinese

by native Chinese speakers and forty compliment responses in English by Chinese learners of English.

D. Classification of Compliment Response Strategies

The qualitative and quantitative analysis of the content of the compliment responses in this study needs a framework

of compliment response strategy categories. The framework developed by Giao Quynh Tran (2003c) can be used for

this purpose. This classification framework consists of a continuum of compliment response strategies from acceptance

to denial strategies and a continuum of avoidance strategies .The framework of compliment response categories is

proposed because there are two reasons. First, previous studies about compliment response have suggested various

frameworks of compliment response categories (Baba, 1999; Chen, 1993; Farghal and Al-Khatib, 2001; Gajaseni, 1994;

Golato, 2002, 2003; Golembeski and Yuan, 1995; Herbert, 1986, 1989, 1990, 1991; Herbert and Straight, 1989; Holmes,

1986; Jeon, 1996; Lorenzo-Dus, 2001; Pomerantz, 1978, 1984; Saito and Beecken, 1997; Yu, 1999; Yuan, 1996, 2001;

etc.), but none of these frameworks individually explain well the data in this study. Moreover, there has not been any

documented framework of compliment response categories in Chinese- English interlanguage pragmatics. Therefore,

this framework can be used to categorize data here. Second, the compliment receiver is sometimes in the dilemma of

whether he/she agrees with the complimenter to be polite or to disagree with the complimenter to avoid self-praise. The

notion of “continuum”, which can be understood as “the strategies in between”, is suggested to solve such a kind of

compliment receiver’s dilemma.

The compliment response strategies developed by Giao Quynh Tran(2003c) are used in my classification framework,

which are placed on the acceptance to denial continuum with compliment upgrade at one end and disagreement at the

other (see Table 1). In addition, avoiding strategies form the avoidance continuum with the ones at the right end

showing avoidance more clearly than those at the left end (see Table 2). The strategies along my two continua vary in

terms of the degree to which they agree or disagree with the complimentary force, or the degree to which they avoid the

praise.

The following are the proposed continua together with the definition and example of each strategy. They are among

the collected data. The underlined words in each example represent the compliment response strategy that the example

illustrates. In the examples, A represents the complimenter and B the complimentee.

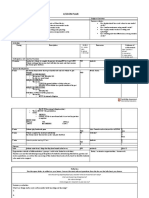

TABLE 1

THE ACCEPTANCE TO DENIAL CONTINUUM

①Compliment Upgrade: The complimentee agrees with and increases the complimentary force.

A: Nice T.V set!

B: Thanks. Brand new.

②Agreement: The complimentee agrees with the complimentary force by providing a response which is

semantically fitted to the compliment.

A: Hey you’re looking really beautiful today.

B: Yeah I’m happy to say that that’s correct.

③Appreciation: The complimentee shows appreciation for the interlocutor’ s previous utterance as a compliment.

A: What a lovely dress!

B: Oh. Thank you. I am glad you say so.

④Return: The complimentee reciprocates the act of complimenting by saying the compliment back to the

complimenter.

A: You’re looking good.

B: Thanks. So are you.

⑤Compliment Downgrade: The complimentee qualifies or downplays the compliment force

A: It’s a really nice car.

B: Oh no. It looks like that but actually it has a lot of problems.

⑥Disagreement: The complimentee thinks the compliment is overdone, and therefore directly disagrees with it.

A: You’re looking brilliant .

B: Oh. No, I don’t think so.

TABLE 2

THE AVOIDANCE CONTINUUM

Expressing Gl -up Question→

①Expressing Gladness: The complimentee does not address the compliment assertion itself, but expresses his/her

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

124 JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH

gladness that the complimenter likes the object of the compliment.

A: I read that article you published last week. It was very good.

B: Well, great.

②Follow-up Question: The complimentee responds to the compliment with a question which is intended to gain

specific information about the worthiness of the object being complimented.

A: You know I just I just read your article that you published last week. I thought it was excellent.

B: Thanks a lot. What do you find interesting about it?

③Doubting Question: The complimentee responds to the compliment with a question which expresses his doubt

about the sincerity / motives of the complimenter.

A: (Referring to B’s article published last year) Fantastic actually.

B: Really?

④Opting out: The complimentee responds to the compliment with laughter or filler.

A: I was just reading your paper, that paper you submitted to the journal the other day. It was really good.

B: Uhm.

E. Data Analysis

Data is analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. In the qualitative analysis, compliment response data is coded

according to the strategies selected to reply to compliments. In the quantitat applied to each

compliment response strategy across groups in order to evaluate whether the differences in the use of each strategy

between groups are statistically significant. Fisher’s test can specify where the difference exists and indicate how

significant the difference is.

To answer the first research question of whether or not there is pragmatic transfer in English by Chinese learners of

English, compliment responses by the native English speaker ,Chinese learner of English and native Chinese speaker

groups are compared. The purpose of the comparison is to find out whether there are significant differences between

them in terms of strategy selection. If there are significant differences in compliment response strategy use by the native

English speaker group and by the Chinese learner of English group, and if there are significant similarities in

compliment response strategy use by the Chinese learner of English group and by the native Chinese speaker group

which can account for the differences between the native English speaker group’s and the Chinese learner of English

group’s data, it can be said that there is pragmatic transfer in the communicative act of responding to compliments in

the interlanguage of Chinese learners of English.

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Differences in the Frequency of Compliment Response Strategies Used Between the Chinese Learner of English

and Native English Groups

Fisher’s test is made to calculate the frequency of each compliment response strategy used by the Chinese learner of

English, native English and native Chinese groups. For the purpose of Fisher’s test, data is rearranged in terms of how

many members of each group do or do not use each compliment response strategy as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

The Fisher’s P-values are also calculated for the comparison of frequency of use of each strategy between groups.

The statistical results are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3

STATISTICAL COMPARISON OF FREQUENCY OF COMPLIMENT RESPONSE STRATEGIES USED BETWEEN THE CHINESE LEARNER OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE

ENGLISH SPEAKER GROUPS

Chinese Learners of English Native English Fisher’s

P- Value

use not use use not use

Compliment 0 10 4 6 0.001

Upgrade

Agreement 1 9 7 3 0.001

Appreciation 6 4 9 1 0.032

Return 1 9 4 6 0.008

Compliment 7 3 1 9 0.001

Downgrade

Disagreement 6 4 1 9 0.000

Expressing 0 10 2 8 0.108

Gladness

Follow-up Question 0 10 2 8 0.242

Doubting Question 3 7 2 8 0.998

Opting out 4 6 0 10 0.001

Table 3 indicates that the frequency of use of the compliment response strategies by the Chinese Learner of English

and native English groups is considerably different. The strategy that is used most frequently by the native English

group is “Appreciation” whereas the most common strategy used by the Chinese learner of English group is

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 125

“Compliment Downgrade”. Table 3 also shows that the Chinese learner of English group uses strategies on the left of

the acceptance to denial continuum, (i.e. from compliment upgrade to return) less frequently than the native English

group. However, the native English group uses strategies on the right of the acceptance to denial continuum ((i.e. from

disagreement to compliment upgrade) less frequently than the Chinese learner of English group. Table 3 also indicates

that no Chinese learner of English informants use strategies on the left half of the avoidance continuum. In other words,

strategies on the left half of the avoidance continuum (i.e. “Expressing Gladness” and “Follow-up Question”) are used

by more native English informants than Chinese learner of English ones. In contrast, strategies on the right half of the

avoidance continuum, (i.e. “Doubting Question” and “Opting Out”), are used by more Chinese learner of English

informants than native English ones.

According to Table 3, there are statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the Chinese learner of

English and native English groups as regards the strategies of “Compliment Upgrade”, “Agreement”, “Compliment

Downgrade”, “Disagreement”, and “Opting out”. Noticeable differences between these two groups are also found in

terms of “ Appreciation”, “Expressing Gladness” , “Follow-up Question” and “doubting question” although the

differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

A close analysis of Table 3 reveals that on the acceptance to denial continuum, no Chinese learner of English

informants use “Compliment Upgrade” whereas four out of ten native English informants use it (p < 0.05).

“Agreement” is used by only one out of ten Chinese learner of English informants but by seven out of ten native

English informants (p < 0.05). Ten Chinese learner of English informants use “Appreciation” much less frequently than

their English counterparts (p < 0.05). The frequency of use of “Return” in the Chinese learner of English group is

significantly lower than that in the English group (p < 0.05). Towards the right end of the acceptance to denial

continuum, “Compliment Downgrade” is used by seven out of ten Chinese learner of English informants but by only

one out of ten English informants (p < 0.05). Six out of ten Chinese learner of English informants use “Disagreement”

whereas only one out of ten English informants did (p < 0.005).

On the avoidance continuum, “Opting out” shows the statistically significant difference between the Chinese learner

of English and native English groups (p < 0.05). “Opting out” is found in the strategy use of Chinese learners of English

but no instance of its use is recorded in native English informants’ data. Table 3 also indicates that the Chinese learner

of English group never selects the avoidance strategies of “Expressing Gladness” and “Follow-up Question” but the

native English group did.

B. Similarities in the Frequency of Compliment Response Strategies Used between the Chinese Learner of English

and Native Chinese Speaker Groups

Results of the statistical analysis and comparison of frequency of compliment response strategy used between The

Chinese Learner of English and the native Chinese groups presented in Frequency of strategy use are calculated on the

basis of the number of informants who did or did not use each strategy in each group.

TABLE 4

STATISTICAL COMPARISON OF FREQUENCY OF COMPLIMENT RESPONSE STRATEGIES USED BETWEEN THE CHINESE LEARNER OF ENGLISH AND

NATIVE CHINESE SPEAKER GROUPS

Chinese Learners of English Native Chinese Fisher’s

P- Value

use not use use not use

Compliment 0 10 0 10 1

Upgrade

Agreement 1 9 0 10 0.225

Appreciation 6 4 2 8 0.049

Return 1 9 2 8 0.603

Compliment 7 3 8 2 0.730

Downgrade

Disagreement 6 4 6 4 1

Expressing 0 10 0 10 1

Gladness

Follow-up Question 0 10 0 10 1

Doubting Question 3 7 3 7 1

Opting out 4 6 6 4 0.529

The general picture that Table 4 gives is that the frequency of strategy use by the Chinese learner of English and

native Chinese groups is remarkably similar. The most common strategy in both the Chinese learner of English and

native Chinese groups is “Compliment Downgrade”. As shown in Table 4, both the Chinese learner of English and

native Chinese groups use strategies on the acceptance side of the continuum (i.e. from “Compliment Upgrade” to

“Return” ) less frequently than the native English group. Moreover, like the Chinese learner of English group, the native

Chinese group uses strategies on the denial side of the continuum (i.e. “Compliment Downgrade” and “Disagreement”)

more often than the native English group. Table 4 displays more similarities between the Chinese learner of English and

native Chinese groups in terms of strategy use. Neither the Chinese learner of English group nor the native Chinese

group use strategies on the left half of the avoidance continuum (i.e. “Expressing Gladness” and “Follow-up Question”),

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

126 JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH

while the native English group does. However, both the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups use

strategies on the right half of the avoidance continuum (i.e. “Doubting Question” and “Opting out”) more frequently

than the native English group.

The similarities in the use of strategies between the native Chinese group and the Chinese learner of English group

can explain the statistically significant differences between the Chinese learner of English and native English groups’

use of “Compliment Upgrade”, “Agreement”, “Appreciation”, “Return”, “Compliment Downgrade”, “Disagreement”,

and “Opting out”. According to Table 4, in both the native Chinese group and the Chinese learner of English group, no

informants use “Compliment Upgrade”. That explains why the difference in frequency of use of this strategy between

the Chinese learner of English and native English groups is statistically significant. This strategy does not occur in

compliment responses in English by Chinese learner of English group because it also does not occur in compliment

responses in Chinese by the native Chinese group. Moreover, no instance of use of “Agreement” is found in the native

Chinese group data from the naturalized role-play. As a result, the Chinese learner of English group uses “Agreement”

at a statistically lower level of frequency compared to the native English group. Therefore, the statistically significant

differences in the use of “Compliment Upgrade” and “Agreement” between the Chinese learner of English and native

English groups as well as the similarities in the use of these strategies between the Chinese learner of English and the

native Chinese groups provide an evidence of pragmatic transfer in compliment response in English by Chinese learners

of English. It can be seen from table 4 that only two out of ten native Chinese use “Appreciation”. That can explain why

this strategy is used less frequently in the Chinese learner of English group than in the native English group.

It is worth emphasizing that “Appreciation” is the strategy that obtains a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the

Chinese learner of English and native English groups. Therefore, Pragmatic transfer from Chinese language can only

partially explain the difference between the Chinese learner of English and native English groups with reference to the

use of this strategy.

“Appreciation” is rarely used by native Chinese group and consequently used less frequently in English by Chinese

learners of English compared to native English groups. However, since the Chinese learner of English group also uses

“Appreciation” significantly more frequently than the native Chinese group (p < 0.05), it could be inferred that the

Chinese learner of English informants adopt the L2 routine of saying “Thank you” to compliments in English. This

reduced the amount of pragmatic transfer with reference to this strategy. A possible reason for limited transfer in the use

of this strategy is because the routine is short and relatively easy to pick up compared to other target language pragmatic

norms.

With reference to “Return”, two native Chinese informants and one Chinese learner of English informant use this

strategy but four native English informants do. The similarity in the frequency of use of this strategy in the Chinese

learner of English and native Chinese groups may explain the unnoticeable difference in the use of this strategy between

the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups (p >0.05). In addition, the use of “Compliment Downgrade”

and “Disagreement” shows a further evidence of pragmatic transfer in Chinese-English interlanguage pragmatics. The

differences between the Chinese learner of English and native English groups in terms of the use of these strategies are

statistically significant (p < 0.05). However, as shown in Table 4, there are striking similarities in the use of these

strategies between the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups. Seven out of ten Chinese learner of

English informants and eight out of ten native Chinese ones use “Compliment Downgrade”; Six out of ten Chinese

learner of English informants and six out of ten native Chinese ones use “Disagreement”. Because these strategies are

frequently used in Chinese, the Chinese learners of English transfer them into their compliment responses in English,

and result in a remarkably higher frequency of use of these strategies than that by native English speakers.

Regarding the strategies on the avoidance continuum, the Chinese learner of English group considerably differs from

the native English group with reference to the use of “Opting out”. However, the Chinese learner of English group

behaves similarly to the native Chinese group. Six out of ten native Chinese informants opt out and four out of ten

Chinese learner of English informants do (See Table 4). The frequency of use of this strategy by the native Chinese

group accounts for the use of it by the Chinese learner of English group and the difference between the Chinese learner

of English and the native English groups. Moreover, none of the Chinese informants use “Expressing Gladness” and

“Follow-up Question” in the naturalized role-play. As a result, these strategies are also not used by the Chinese learner

of English informants whereas they are used by the native English informants. Because the difference between the

Chinese learner of English and native English groups in “Expressing Gladness” and “Follow-up Question” are

statistically significant (P<0.05) , the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups with reference to these

strategies can be viewed as a strong evidence of pragmatic transfer from Chinese language.

Results from the data analysis have demonstrated that there are not only significant differences in compliment

response strategy use between the native English group and the Chinese learner of English group, but also the

similarities in compliment response strategy use between the Chinese learner of English group and the native Chinese

group. These research results provide a positive answer to the first question. There is pragmatic transfer in the use of

compliment response strategies by Chinese learners of English as a foreign language.

With reference to the second research question of what is transferred, the answer has been integrated into the answer

to the first question of whether there is pragmatic transfer because it is impossible to provide an evidence of pragmatic

transfer without simultaneously describing what is transferred. As discussed above, the compliment response strategies

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 127

that are pragmatically transferred are “Compliment Upgrade”, “Agreement”, “Appreciation”, “Return”, “Compliment

Downgrade”, “Disagreement”, “Expressing Gladness”, “Follow-up Question”, and “Opting out”.

All of the strategies that show significant differences (i.e. “Compliment Upgrade”, Agreement”, “Appreciation”,

“Return”, “Compliment Downgrade”, “Disagreement”, and “Opting out”) between the Chinese learner of English and

native English groups are also the strategies that display the close similarities between the Chinese learner of English

and native Chinese groups,and therefore they are the strategies that are transferred from Chinese into English by

Chinese learners of English.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this paper has studied pragmatic transfer and identified transferred pragmatic features from Chinese

into English by Chinese learners of English. Two new continua of compliment response strategies are used to analyze

the compliment response strategy data. The first continuum is the acceptance to denial continuum which consists of

“Compliment Upgrade”, “Agreement”, “Appreciation”, “Return”, “Compliment Downgrade” and “Disagreement”. The

second continuum is the avoidance continuum which comprises “Expressing Gladness”, “Follow-up Question”,

“Doubting Question” and “Opting out”. Along these continua, an evidence of pragmatic transfer is found in the

frequency of use of the following compliment response strategies by Chinese learners of English: “Compliment

Upgrade”, “Agreement”, “Appreciation”, “Return”, “Compliment Downgrade”, “Disagreement”, “Expressing

Gladness”, “Follow-up Question” and “Opting out”.

The innovation of this study is the application of the naturalized role-play to collect data on pragmatic transfer, and

data analysis are made on the statistically significant differences in terms of compliment response strategy use between

the Chinese learner of English and native English groups and on the close similarities in the respect of compliment

response strategy use between the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups.

Although there is a significant difference between the Chinese learner of English and native English groups in terms

of the use of “Appreciation”, the difference between the Chinese learner of English and native Chinese groups

regarding the use of this strategy is even greater than the difference between the Chinese learner of English and native

English groups (See Tables 3 & 4). An interpretation of this result is that the Chinese learners of English have used the

English routine of saying “Thank you” to compliments, so they use this strategy more frequently than the native

Chinese.

The patterns of research framework used in this study have laid the foundation of research methodology for a new

interlanguage pragmatic research, which can be used to explore pragmatic transfer of other speech acts by Chinese

learners of English.

APPENDIX A NATURALIZED ROLE-PLAY

Directions: The following two situations describe the role-play informants and the role-play researcher in certain

familiar roles. Please listen to the description of the situation and identify yourself with the character “you” in it. The

task of the researcher is to lead the conversation in a flexible and natural way. If you have any question, please feel free

to ask.

1. Situation 1:

①To the role-play informants:

You are one of the best students in your class. You have recently been awarded the first prize for the English

Speaking Contest in your university. There is a newcomer to your class. Your two know each other’s name and but

have not yet had a chance to talk much.

It is now around 6 pm and you are leaving school for home. You walk in the campus towards your new bicycle. That

new classmate approaches you and says some greetings. Your two talk while you walk together. The social talk should

include the following points (See the card for role-play informants below).

②In the card for the role-play informants:

- (When being asked) Please give him/her directions to get to the bookshop

- (When being asked) Please tell him/her when the bookshop is closed today.

Please make the conversation as natural as possible. Speak as you would in real life.

③To the role-play researcher:

You are a newcomer to a class. One of your new classmates is a very good student with the first prize recently

awarded for the English Speaking Contest in your University. Your two know each other’s name but have not yet had a

chance to talk much.

It is now around 6 pm and you are leaving school. You want to stop by a bookshop and have heard that there is one

bookshop not far from the university but you do not know where it is. You pass by the parking lot and see that new

classmate. You approach him/her and say some greetings. Your two talk while you walk together. The talk should

include the following points (See the card for role-play researcher below).

④In the card for the role-play researcher:

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

128 JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH

- Please ask for directions to get to the bookshop.

- Please ask him/her what time the bookshop is closed today.

- When it is most natural during the talk, compliment him/her on:

his / her excellent oral English performance at the English Speaking Contest in your university

his / her bicycle

Please make the conversation as natural as possible. Speak as you would in real life. It is very important that you

compliment naturally and make your compliments a part of the normal social talk. Do not make it obvious that the

compliments are among the tasks listed in the card for you.

2. Situation 2:

①To the role-play informants:

About a week after that situation, you are invited to a dinner party at that new classmate’s house. When he/she invites

you to come over, he/she gives you a printed map showing where to park your bicycle. Today is the day of the party.

You dress up for the event and ride your bicycle there. Now you are at his/her doorstep. Your two say some greetings

and talk while he/she leads you to the living room. The social talk should include the following points (See the card for

role-play informants below).

②In the card for the role-play informants:

- (At the door and after some greetings) Please check with him/her whether you have parked your bicycle in the right

place.

- (After he/she has put your coat in the hall for you) Please ask if he/she is all right/ feeling better now (because you

did not see him/her at the class seminar a few days ago and were told that he/she was not well).

Please make the conversation as natural as possible. Speak as you would in real life.

③To the role-play researcher:

About a week after that situation, you invite this new classmate to a dinner party at your house. Today is the day of

the party. You greet him/her at the door. Your two talk while you lead him/her to the living room. The social talk should

include the following points (See the card for role-play researcher below).

④In the card for the role-play researcher:

- (When being asked) Please assure him/her that he/she has parked in the right place.

- Please respond to his/her question expressing concern about your health (which is asked because he/she did not see

you at the class seminar a few days ago and they said you were not feeling well).

- When it is most natural during the talk, compliment him/her on:

his / her appearance that day

his / her clothing (e.g. her dress or his tie)

Please make the conversation as natural as possible. Speak as you would in real life. It is very important that you

compliment naturally and make your compliments a part of the normal social talk. Do not make it obvious that the

compliments are among the tasks

REFERENCES

[1] Baba, J. (1996). A Study of interlanguage pragmatics: Compliment responses by learners of Japanese and English as a second

language. Unpublished PhD dissertation. The University of Texas at Austin.

[2] Baba, J. (1999). Interlanguage pragmatics: Compliment responses by learners of Japanese and English as a second language.

Muenchen: Lincom Europa.

[3] Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Hartford, B. S. (1990). Congruence in native and nonnative conversations: Status balance in the

academic advising session. Language learning, 40, 467-501.

[4] Barnlund, D. C., & Araki, S. (1985). Intercultural encounters: The management of compliments by Japanese and Americans.

Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 16, 9- 26.

[5] Chen, R. (1993). Responding to compliments: A contrastive study of politeness strategies between American English and

Chinese speakers. Journal of pragmatics, 20, 49-75.

[6] Farghal, M., & Al-Khatib, M. A. (2001). Jordanian college students' responses to compliments: A pilot study. Journal of

pragmatics, 33, 1485-1502.

[7] Gajaseni, C. (1994). A contrastive study of compliment responses in American English and Thai including the effect of gender

and social status. Unpublished PhD dissertation. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

[8] Golato, A. (2002). German compliment responses. Journal of pragmatics, 34, 547-571.

[9] Golato, A. (2003). Studying compliment responses: A comparison of DCTs and recordings of naturally occurring talk. Applied

linguistics, 24(1), 90-121.

[10] Golembeski, D., & Yuan, Y. (1995). Responding to compliments: A cross-linguistic study of the English pragmatics of Chinese,

French and English speakers. Paper presented at the International Conference on Pragmatics and Language Learning,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL.

[11] Herbert, R. K. (1986). Say "thank you", or something. American speech, 61, 76-88.

[12] Herbert, R. K. (1989). The ethnography of English compliments and compliment responses: A contrastive sketch. In W. Oleksy

(Ed.), Contrastive pragmatics (pp. 3-36). Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

[13] Herbert, R. K. (1990). Sex-based differences in compliment behavior. Language in society, 19, 201-224.

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE TEACHING AND RESEARCH 129

[14] Herbert, R. K. (1991). The sociology of compliment work: An ethnocontrastive study of Polish and English compliments.

Multilingua, 10(4), 381-402.

[15] Herbert, R. K., & Straight, S. (1989). Compliment-rejection versus complimentavoidance: Listener-based versus speaker-based

pragmatic strategies. Language and communication, 35-47.

[16] Holmes, J. (1986). Compliments and compliment responses in New Zealand English. Anthropological linguistics, 28(4),

485-508.

[17] Jeon, Y. (1996). A descriptive study on the development of pragmatic competence by Korean learners of English in the speech

act of complimenting. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Texas A&M University.

[18] Johnson, D. (1979). Entertaining and etiquette for today. Washington, DC: Acropolis Books.

[19] Faerch, Claus & Kasper Gabriele (1984). Pragmatic Knowledge: Rules and Procedures. Applied Linguistics, 5(3): 214-225

[20] Kasper, G. (1992). Pragmatic transfer. Second language research, 8(3), 203-231.

[21] Knapp, M. L., Hopper, R., & Bell, R. A. (1984). Compliments: A descriptive taxonomy. Journal of communication, 34, 12-31.

[22] Lorenzo-Dus, N. (2001). Compliment responses among British and Spanish university students: A contrastive study. Journal of

pragmatics, 33, 107-127.

[23] Odlin, T. (2003). Cross-linguistic influence. In C. J. Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language

acquisition (pp. 436-486). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

[24] Pomerantz, A. (1978). Compliment responses: Notes on the co-operation of multiple constraints. In J. Schenkein (Ed.), Studies

in the organization of conversational interaction (pp. 79-112). New York: Academic Press.

[25] Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M.

Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 225-246). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[26] Saito, H., & Beecken, M. (1997). An approach to instruction of pragmatic aspects: Implications of pragmatic transfer by

American learners of Japanese. The modern language journal, 81(3), 363-377.

[27] Soenarso, L. I. (1988). Developing social competence in complimenting behaviour among Indonesian learners of English.

Unpublished MA thesis. Canberra College of Advanced Education, Canberra.

[28] Tran, Giao Quynh (2003b). The Naturalized Role-play. Paper presented at the Research Methods in Interlanguage Pragmatics

Workshop, The University of Melbourne, 19 February 2003.

[29] Tran, Giao Quynh (2003c). The Naturalized Role-play: A different methodology in crosscultural and interlanguage pragmatics.

Paper presented at the 2003 conference of the Australian Linguistic Society at Newcastle University, 26-28 September 2003.

[30] Tran, Giao Quynh (2003d). Transfer and universality in interlanguage pragmatics. Melbourne papers in linguistics and applied

linguistics, 3(1), 42-56.

[31] Tran, Giao Quynh (2006b). The Naturalized Role-play: An innovative methodology in cross-cultural and interlanguage

pragmatics research. Reflections on English language teaching, 5(2), 1-24.

[32] Tran, Giao Quynh (2007). Compliment response continuum hypothesis. Language, society and culture.

[33] Yu, M. (1999). Cross-cultural and interlanguage pragmatics: Developing communicative competence in a second language.

Unpublished EdD dissertation. Harvard University.

[34] Yuan, Y. (1996). Responding to compliments: A contrastive study of the English pragmatics of advanced Chinese speakers of

English. In A. Stringfellow, D. Cahana- Amitay, E. Hughes & A. Zukowski (Eds.), The 20th annual Boston University

conference on language development (Vol. 2, pp. 861-872). Boston: Cascadilla Press.

[35] Yuan, Y. (2001). An inquiry into empirical pragmatics data-gathering methods: Written DCTs, oral DCTs, field notes, and

natural conversations. Journal of pragmatics, 33, 271- 292.

Jiemin Bu received his M. A degree in English language and literature from Shanghai International Studies

University, Shanghai, China. He is currently an associate professor of English in the foreign languages school,

Zhejiang Guangsha College of Applied Construction, Zhejiang , China.

Over the past 16 years he has been teaching English as a foreign language to Chinese students and doing

research in the field of linguistics, applied linguistics and pragmatics. He has published more than 20 papers

in journals. His current research focuses on interlanguage pragmatics of Chinese learners of English.

© 2010 ACADEMY PUBLISHER

You might also like

- Revision Exersice MANDARINDocument9 pagesRevision Exersice MANDARINIrdina SahiraNo ratings yet

- English 9 Quarter 1 Module 5 For PrintingDocument11 pagesEnglish 9 Quarter 1 Module 5 For PrintingMa Kriselda Anino Secarro100% (2)

- Cutrone Vol 2Document10 pagesCutrone Vol 2Mike PikeNo ratings yet

- Language Learning Strategies and English Proficiency: A Study of Chinese Undergraduate Programs in ThailandDocument5 pagesLanguage Learning Strategies and English Proficiency: A Study of Chinese Undergraduate Programs in ThailandMuhammad Shofyan IskandarNo ratings yet

- A Study of Compliment ResponsesDocument15 pagesA Study of Compliment Responsesuchiha1119No ratings yet

- 1-An Investigation of EnglishDocument21 pages1-An Investigation of EnglishRocky HermawanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Negative Transfer of Mother Tongue On College ESL Learners: Zhejiang Yuexiu University As A Case StudyDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Negative Transfer of Mother Tongue On College ESL Learners: Zhejiang Yuexiu University As A Case StudyRachell M. DiazNo ratings yet

- The Attitude of Grade 12 HUMSS Students Towards Speaking in EnglishDocument17 pagesThe Attitude of Grade 12 HUMSS Students Towards Speaking in EnglishEric Glenn CalingaNo ratings yet

- Refusal Strategies and Perceptions of Social Factors For Refusing: Empirical Insights From Turkish Learners of EnglishDocument17 pagesRefusal Strategies and Perceptions of Social Factors For Refusing: Empirical Insights From Turkish Learners of EnglishNgọc Trâm ThiềuNo ratings yet

- In Recent TimesDocument2 pagesIn Recent Timeshura kaleemNo ratings yet

- Unveiling The Linguistic Tapestry - Concept PaperDocument18 pagesUnveiling The Linguistic Tapestry - Concept PaperDaniel TomnobNo ratings yet

- Research Paper English Language ProficiencyDocument8 pagesResearch Paper English Language Proficiencypym0d1sovyf3100% (3)

- Using All English Is Not Always Meaningful'Document6 pagesUsing All English Is Not Always Meaningful'Erjin PadinNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument10 pagesChapter IIMel SantosNo ratings yet

- System: Jim Yee Him ChanDocument18 pagesSystem: Jim Yee Him ChanAbdul Wahid TocaloNo ratings yet

- 04-Ed-Huynh Ngoc Tuyen (20-30)Document11 pages04-Ed-Huynh Ngoc Tuyen (20-30)Trung Kiên NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Translation Strategies Applied in English and Chinese IdiomsDocument4 pagesTranslation Strategies Applied in English and Chinese Idiomshoadhm71No ratings yet

- Pragmatics 4Document21 pagesPragmatics 4Armajaya Fajar SuhardimanNo ratings yet

- Effects of Global Englishes-Informed Pedagogy in Raising Chinese University Students' Global Englishes AwarenessDocument37 pagesEffects of Global Englishes-Informed Pedagogy in Raising Chinese University Students' Global Englishes AwarenessNga ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Attitude of Grade 12 SHS Academic Tracks Students TowardsDocument15 pagesAttitude of Grade 12 SHS Academic Tracks Students TowardsFlora SeryNo ratings yet

- Attitude of Grade 12 SHS Academic Tracks Students Towards Speaking in EnglishDocument13 pagesAttitude of Grade 12 SHS Academic Tracks Students Towards Speaking in EnglishLlyann espadaNo ratings yet

- The Application of Discourse Analysis To English Reading Teaching in Chinese Universities-What Is The Focus?Document12 pagesThe Application of Discourse Analysis To English Reading Teaching in Chinese Universities-What Is The Focus?Le DucNo ratings yet

- Zhengdong GanDocument16 pagesZhengdong Ganapi-3771376No ratings yet

- Determining The Relationship Between Students' Attitudes Toward English-Cebuano Code Switching and Their English Academic PerformanceDocument10 pagesDetermining The Relationship Between Students' Attitudes Toward English-Cebuano Code Switching and Their English Academic PerformanceDhen Sujero SitoyNo ratings yet

- Development of Oral Communication Skills Abroad: Illinois Wesleyan UniversityDocument25 pagesDevelopment of Oral Communication Skills Abroad: Illinois Wesleyan UniversityMohd FitriNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Pragmatics and Its Challenges in Efl ContextDocument10 pagesCross-Cultural Pragmatics and Its Challenges in Efl ContextSabrinaNo ratings yet

- Compliment Speech ActDocument5 pagesCompliment Speech ActStefania Silvia SoricNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Native Language Use On Second ... - ERICDocument7 pagesThe Impact of Native Language Use On Second ... - ERICIdk May Be SaleehaNo ratings yet

- The Role of First Language in Second Language AcquisitionDocument8 pagesThe Role of First Language in Second Language AcquisitionLauraNo ratings yet

- Art. A Study of Teacher and Student Perceptions Concerning Grammar-Translation Method and Communicative Language Teaching PDFDocument18 pagesArt. A Study of Teacher and Student Perceptions Concerning Grammar-Translation Method and Communicative Language Teaching PDFyasser hocNo ratings yet

- Journal of Pragmatics Cheng Compliment ResponsesDocument11 pagesJournal of Pragmatics Cheng Compliment ResponsesLevente JambrikNo ratings yet

- 900 DraftDocument5 pages900 Draftzhengdiwen99No ratings yet

- Apology Strategies Used by EFL Undergraduate Students in IndonesiaDocument9 pagesApology Strategies Used by EFL Undergraduate Students in IndonesiaSaood KhanNo ratings yet

- Impact of Using English Language in Class DiscussionDocument13 pagesImpact of Using English Language in Class DiscussionRufaida AjidNo ratings yet

- Taguchi 2011 Language LearningDocument36 pagesTaguchi 2011 Language LearningFer CRNo ratings yet

- A Contrastive Study of Grammar TranslatiDocument12 pagesA Contrastive Study of Grammar TranslatiRoelNo ratings yet

- Thesis Language TeachingDocument8 pagesThesis Language Teachingchelseaporterpittsburgh100% (2)

- Research Proposal TemplateDocument7 pagesResearch Proposal TemplateNazir AhmedNo ratings yet

- Morphological Awareness, Vocabulary Knowledge, Lexical Inference, and Text Comprehension in Chinese in Grade 3Document26 pagesMorphological Awareness, Vocabulary Knowledge, Lexical Inference, and Text Comprehension in Chinese in Grade 3feaNo ratings yet

- RRLDocument3 pagesRRLJiro LatNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Teaching Vocabulary Through The Diglot - Weave Technique and Attitude Towards This TechniqueDocument6 pagesThe Effect of Teaching Vocabulary Through The Diglot - Weave Technique and Attitude Towards This TechniqueDr. Azadeh NematiNo ratings yet

- Direct IndirectDocument42 pagesDirect IndirectJason CooperNo ratings yet

- Sotolongo, e Ar Final PaperDocument47 pagesSotolongo, e Ar Final Paperapi-235897157No ratings yet

- Students' Attitudes Towards The Study of English and French in A Private University Setting in GhanaDocument12 pagesStudents' Attitudes Towards The Study of English and French in A Private University Setting in Ghanaksimpeh2001No ratings yet

- Task 1Document3 pagesTask 1Vũ Công ĐạtNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877042816313404 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1877042816313404 MainWIWID SUTANTI ALFAJRINNo ratings yet

- Lexical Variation On Students' Daily Conversation at Campus by First Year Students of English Department FKIP HKBP Nommensen UniversityDocument12 pagesLexical Variation On Students' Daily Conversation at Campus by First Year Students of English Department FKIP HKBP Nommensen UniversityCriss DeeaNo ratings yet

- An Experimental Study of The Effects of Listening On Speaking For College StudentsDocument11 pagesAn Experimental Study of The Effects of Listening On Speaking For College Studentsالهام شیواNo ratings yet

- Focus-On-Form and Corrective Feedback in Communicative Language TeachingDocument20 pagesFocus-On-Form and Corrective Feedback in Communicative Language TeachingViet Nguyen DinhNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument20 pages1 PBHasrullahNo ratings yet

- ,DanaInfo Proquest Umi Com+outDocument7 pages,DanaInfo Proquest Umi Com+outnirmalarothinamNo ratings yet

- Some Aspects of Technology in Teaching English To English Language LearnersDocument4 pagesSome Aspects of Technology in Teaching English To English Language Learnersrozusk8No ratings yet

- 6280 20074 1 SMDocument23 pages6280 20074 1 SMKyel LopezNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis #564404 - 713830Document8 pagesAn Overview of Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis #564404 - 713830Tripty Rani RoyNo ratings yet

- TesolresearchpaperDocument19 pagesTesolresearchpaperapi-352250903No ratings yet

- 2.SABINA HALUPKA-RESETAR - Full Text PDFDocument19 pages2.SABINA HALUPKA-RESETAR - Full Text PDFAmal MchNo ratings yet

- Development On The Four Domain Skills of English Language by Grade 12 Contact Center Services Students Through Work ImmersionDocument55 pagesDevelopment On The Four Domain Skills of English Language by Grade 12 Contact Center Services Students Through Work ImmersionEcko ValenciaNo ratings yet

- MA Gist Conference PresentationDocument22 pagesMA Gist Conference PresentationA ZNo ratings yet

- Grammar Translation MethodDocument12 pagesGrammar Translation MethodJacqueline KeohNo ratings yet

- TemplateDocument13 pagesTemplatedelacruzjelynne8No ratings yet

- B Albertson Final ReportDocument20 pagesB Albertson Final ReportBrendon AlbertsonNo ratings yet

- Analysis of a Medical Research Corpus: A Prelude for Learners, Teachers, Readers and BeyondFrom EverandAnalysis of a Medical Research Corpus: A Prelude for Learners, Teachers, Readers and BeyondNo ratings yet

- American PoetryDocument12 pagesAmerican PoetryRakesh PKNo ratings yet

- IMO SyllabusDocument4 pagesIMO SyllabusMonika SinghalNo ratings yet

- Review 456Document11 pagesReview 456Đạt TrươngNo ratings yet

- Final Test: 1.sarah Likes Teaching English When ..Document10 pagesFinal Test: 1.sarah Likes Teaching English When ..Kerry KoNepeNo ratings yet

- Khao Sat Chat Luong Dau Nam Lop 10 Mon Tieng AnhDocument9 pagesKhao Sat Chat Luong Dau Nam Lop 10 Mon Tieng AnhhuongNo ratings yet

- Stuctural John Said The Man Who Died Yesterday: - AmbiguityDocument1 pageStuctural John Said The Man Who Died Yesterday: - AmbiguityNgọc KhánhNo ratings yet

- Nama: Rachel Ria Felisiana Sidebang Nim: 1203311110 M. Kuliah: Bahasa InggrisDocument7 pagesNama: Rachel Ria Felisiana Sidebang Nim: 1203311110 M. Kuliah: Bahasa InggrisRachel Ria Felisiana sidebangNo ratings yet

- INSIGHT Inter - S's BookDocument166 pagesINSIGHT Inter - S's BookPhung Bao ChiNo ratings yet

- English For Undergraduate at URDocument81 pagesEnglish For Undergraduate at URNuyul AjaNo ratings yet

- Negative Question Tag Positive Question Tag: Remember !Document2 pagesNegative Question Tag Positive Question Tag: Remember !DeeaMusat100% (1)

- Modal Verbs + Practice PET TestDocument3 pagesModal Verbs + Practice PET TestThuy VoNo ratings yet

- Laporan Minggu Panitia Bahasa Inggeris 2019Document3 pagesLaporan Minggu Panitia Bahasa Inggeris 2019Ag Muhammad ZakieNo ratings yet

- Sample Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesSample Lesson PlanShekinah ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Template - MID EXAM - ENGLISH - 2020Document4 pagesTemplate - MID EXAM - ENGLISH - 2020Def ChanNo ratings yet

- Ebook Developing Person Through The Life Span 9Th Edition Berger Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument44 pagesEbook Developing Person Through The Life Span 9Th Edition Berger Test Bank Full Chapter PDFbastmedalist8t2a100% (11)

- UNIT 6 - Party Time! PDFDocument11 pagesUNIT 6 - Party Time! PDFJuan C. FlorezNo ratings yet

- Creative Writing Guide GcseDocument1 pageCreative Writing Guide GcseAkshara ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Block-03 Reading and Writing SkillDocument73 pagesBlock-03 Reading and Writing SkillShijil SamuelNo ratings yet

- Conditional Sentences ExercisesDocument2 pagesConditional Sentences ExercisesCrisNo ratings yet

- Gerund: Name: M.Rizky Yunus Class:Xi Analis 3Document26 pagesGerund: Name: M.Rizky Yunus Class:Xi Analis 3nua iretsonNo ratings yet

- Worksheet N 04 Passive VoiceDocument3 pagesWorksheet N 04 Passive VoiceSergio SilvpvNo ratings yet

- Afif Aziz WorksheetDocument5 pagesAfif Aziz WorksheetAfif AzizNo ratings yet

- PhilenglishfinalDocument6 pagesPhilenglishfinalJao DasigNo ratings yet

- Semi-Lp EnglishDocument4 pagesSemi-Lp EnglishJulienne VilladarezNo ratings yet

- Language ResearchDocument8 pagesLanguage ResearchEditha BallesterosNo ratings yet

- HW Elem TRD Unit Test 06aDocument3 pagesHW Elem TRD Unit Test 06aSamon Vann100% (1)

- Raden Saleh Syarif Bustaman (Circa 1811-1880) and The Java War (1825-30) : A Dissident Family HistoryDocument41 pagesRaden Saleh Syarif Bustaman (Circa 1811-1880) and The Java War (1825-30) : A Dissident Family HistoryNik Rakib Nik Hassan IINo ratings yet

- Typing Speed (AutoRecovered)Document8 pagesTyping Speed (AutoRecovered)Mufizul islam NirobNo ratings yet