Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NATURE - Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in Responses To Heart Failure Therapies (Chyou Et Al., 2024)

NATURE - Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in Responses To Heart Failure Therapies (Chyou Et Al., 2024)

Uploaded by

Marcelo TrCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Boylan - The Spiritual Life of The PriestDocument63 pagesBoylan - The Spiritual Life of The Priestpablotrollano100% (1)

- Module 2 1 Math 10 Graphs of Polynomial Functions FinalDocument29 pagesModule 2 1 Math 10 Graphs of Polynomial Functions FinalJacob Sanchez100% (1)

- Update On Psychotropic Medication Use in Renal DiseaseDocument15 pagesUpdate On Psychotropic Medication Use in Renal DiseaseMartinaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Sexual Activity After Myocardial Revascularizat 2021 Current Problems in CarDocument16 pages2021 Sexual Activity After Myocardial Revascularizat 2021 Current Problems in CarAngie OvandoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 69Document8 pagesChapter 69ingbarragan87No ratings yet

- Importance of Pharmacogenomics in The Personalized MedicineDocument6 pagesImportance of Pharmacogenomics in The Personalized MedicineJames AustinNo ratings yet

- Adv Pharmacology - AnswerDocument7 pagesAdv Pharmacology - AnswerMEHATHI SUBASHNo ratings yet

- Patel 2017Document11 pagesPatel 2017Imanuel CristiantoNo ratings yet

- 2021 Sexual Activity After Myocardial Revascularizat 2021 Current Problems in Ca1Document17 pages2021 Sexual Activity After Myocardial Revascularizat 2021 Current Problems in Ca1Angie OvandoNo ratings yet

- Pharmacogenetics of Cardiovascular Drug TherapyDocument11 pagesPharmacogenetics of Cardiovascular Drug Therapybalaji5563No ratings yet

- Adrs For WomenDocument9 pagesAdrs For WomenFajar PutraNo ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Disease Manifestation and PresentationDocument5 pagesGender Differences in Disease Manifestation and PresentationGustavo Anzola100% (1)

- Cubała W. (ZOLPIDEM) 0Document2 pagesCubała W. (ZOLPIDEM) 0Antonio SanchezNo ratings yet

- Combination Medical Therapy For Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDocument9 pagesCombination Medical Therapy For Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaganangahimsaNo ratings yet

- Erectile Dysfunction and HypertensionDocument8 pagesErectile Dysfunction and HypertensionILham SyahNo ratings yet

- 2017 - Behavioral Emergencies - Geriatric Psychiatric PatientDocument14 pages2017 - Behavioral Emergencies - Geriatric Psychiatric PatientAna María Arenas DávilaNo ratings yet

- Prescribing Pattern of Antihypertensive Drugs in A Tertiary Care Hospital in Jammu-A Descriptive StudyDocument4 pagesPrescribing Pattern of Antihypertensive Drugs in A Tertiary Care Hospital in Jammu-A Descriptive StudyMahantesh NyayakarNo ratings yet

- Key Points To RememberDocument37 pagesKey Points To RememberheikalNo ratings yet

- AJGP 0102 2023 Focus Chung Male Sexual Dysfunction WEBDocument5 pagesAJGP 0102 2023 Focus Chung Male Sexual Dysfunction WEBrisang akrima fikriNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy For Cardiovascular Disorders EditedDocument5 pagesPharmacotherapy For Cardiovascular Disorders Editedhutwriters2No ratings yet

- Piis2050052117300744 PDFDocument15 pagesPiis2050052117300744 PDFRichu UhcirNo ratings yet

- Diet and Men 'S Sexual Health: Rates of Male Sexual DysfunctionsDocument15 pagesDiet and Men 'S Sexual Health: Rates of Male Sexual DysfunctionsHoa VânNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction - JAMA (2023)Document12 pagesHeart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction - JAMA (2023)cheve glzNo ratings yet

- Redfield Margaret M Heart Failure With PreservedDocument12 pagesRedfield Margaret M Heart Failure With PreservedNathan Kulkys MarquesNo ratings yet

- Solomon 2006Document5 pagesSolomon 2006Ottofianus Hewick KalangiNo ratings yet

- Erectile Dysfunction and Comorbid Diseases, Androgen Deficiency, and Diminished Libido in MenDocument7 pagesErectile Dysfunction and Comorbid Diseases, Androgen Deficiency, and Diminished Libido in MenAfif Al FatihNo ratings yet

- Captura de Pantalla 2022-08-15 A La(s) 17.37.40 PDFDocument11 pagesCaptura de Pantalla 2022-08-15 A La(s) 17.37.40 PDFMatias PadillaNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutics 15 01002 v3Document20 pagesPharmaceutics 15 01002 v3YASH BNo ratings yet

- Chew Et Al-2008-Journal of The American Geriatrics Society PDFDocument9 pagesChew Et Al-2008-Journal of The American Geriatrics Society PDFChrysoula GkaniNo ratings yet

- JNC8Document21 pagesJNC8ZakisyarifudintaqiyNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological and Parenteral Therapies in Older Adult PopulationDocument5 pagesPharmacological and Parenteral Therapies in Older Adult PopulationNDINDA GODYFREEY NATTOHNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Drug TherapyDocument48 pagesGeriatric Drug Therapywalt65No ratings yet

- AndrologyDocument298 pagesAndrologyPrakash JanakiramanNo ratings yet

- Hulley 1998Document9 pagesHulley 1998junta.propietarios.1456No ratings yet

- Variation of Drug Response-1Document26 pagesVariation of Drug Response-1كسلان اكتب اسميNo ratings yet

- Management of Constipation in Patients With Schizophrenia - A Case Study and Review of LiteratureDocument7 pagesManagement of Constipation in Patients With Schizophrenia - A Case Study and Review of LiteratureRimayNo ratings yet

- Hormone Replacement HerapyDocument5 pagesHormone Replacement HerapyCindy HartNo ratings yet

- Cfs 8 PDFDocument9 pagesCfs 8 PDFDaniel Fernando Mendez CarbajalNo ratings yet

- Risk Related To Hormone Therapy and Cardiovascular Disease in WomenDocument44 pagesRisk Related To Hormone Therapy and Cardiovascular Disease in Womenosama saeedNo ratings yet

- Pharmacogenetics and The Concept of Individualized Medicine: BS ShastryDocument6 pagesPharmacogenetics and The Concept of Individualized Medicine: BS Shastrykunalprabhu148No ratings yet

- Cardiology PDFDocument9 pagesCardiology PDFFC Mekar AbadiNo ratings yet

- Ultrafiltration Therapy For Cardiorenal Syndrome Physiologic Basis and Contemporary OptionsDocument9 pagesUltrafiltration Therapy For Cardiorenal Syndrome Physiologic Basis and Contemporary Optionsfernando.suarez.mtzNo ratings yet

- Cancer-Relatedfatiguein Cancersurvivorship: Chidinma C. Ebede,, Yongchang Jang,, Carmen P. EscalanteDocument13 pagesCancer-Relatedfatiguein Cancersurvivorship: Chidinma C. Ebede,, Yongchang Jang,, Carmen P. EscalanteMahdhun ShiddiqNo ratings yet

- Reversibledementias: Milta O. LittleDocument26 pagesReversibledementias: Milta O. LittleLUCAS IGNACIO SANCHEZNo ratings yet

- Interacciones Medicamentos en Odontologia 2017 PDFDocument35 pagesInteracciones Medicamentos en Odontologia 2017 PDFDANIELA PARRA BOTERONo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0735109723003686 MainDocument19 pages1 s2.0 S0735109723003686 MainArunNo ratings yet

- Hudmon 2007Document4 pagesHudmon 2007ARAFAT MIAHNo ratings yet

- Preventive Cardiology For WomenDocument5 pagesPreventive Cardiology For WomenninataniaaaNo ratings yet

- CollegePharmacy BHRT Abstracts ReviewsDocument46 pagesCollegePharmacy BHRT Abstracts ReviewsJoyce IpadNo ratings yet

- Ethn 15 01 116Document8 pagesEthn 15 01 116Bot AINo ratings yet

- Gerotological Care IssuesDocument21 pagesGerotological Care IssuesOdey GodwinNo ratings yet

- Case StudiesDocument5 pagesCase Studiespragna novaNo ratings yet

- Prescribing For The ElderlyDocument8 pagesPrescribing For The ElderlykarladeyNo ratings yet

- Comparative Effectiveness of Diuretic Regimens: EditorialDocument2 pagesComparative Effectiveness of Diuretic Regimens: EditorialFabio Luis Padilla AvilaNo ratings yet

- Geriatric Pharmacology. Journal of The American Podriatric Medical AssociationDocument8 pagesGeriatric Pharmacology. Journal of The American Podriatric Medical AssociationJose Fernando Díez ConchaNo ratings yet

- Examining The Effects of Herbs On TestosteroneDocument22 pagesExamining The Effects of Herbs On TestosteroneKelson dos SantosNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Care For All Patients - AjmDocument3 pagesEvidence Based Care For All Patients - Ajmdaniel martinNo ratings yet

- Consenso IccDocument15 pagesConsenso IccMaida Martinez AngelesNo ratings yet

- David J. Greenblatt D. (ZOLPIDEM) 2Document9 pagesDavid J. Greenblatt D. (ZOLPIDEM) 2Antonio SanchezNo ratings yet

- Top 5 - Considerations For Anesthesia of A Geriatric PatientDocument5 pagesTop 5 - Considerations For Anesthesia of A Geriatric PatientMabe AguirreNo ratings yet

- The Prevention and Treatment of Disease with a Plant-Based Diet Volume 2: Evidence-based articles to guide the physicianFrom EverandThe Prevention and Treatment of Disease with a Plant-Based Diet Volume 2: Evidence-based articles to guide the physicianNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 4: VascularFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 4: VascularNo ratings yet

- Hprocedure of Export or ImportDocument96 pagesHprocedure of Export or ImportHiren RatnaniNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument15 pagesIntroductionAhinurNo ratings yet

- Star Holman 210HX Conveyor OvenDocument2 pagesStar Holman 210HX Conveyor Ovenwsfc-ebayNo ratings yet

- Global Warming (Word Formation)Document2 pagesGlobal Warming (Word Formation)EvaNo ratings yet

- Bba 400 Module Revised 2017 April To DsvolDocument68 pagesBba 400 Module Revised 2017 April To DsvolKafonyi JohnNo ratings yet

- IfDocument44 pagesIfSean RoxasNo ratings yet

- The Wall Street Journal - Vol. 277 No. 075 (01 Apr 2021)Document32 pagesThe Wall Street Journal - Vol. 277 No. 075 (01 Apr 2021)Andrei StrăchinescuNo ratings yet

- Islam Articles of FaithDocument1 pageIslam Articles of Faithapi-247725573No ratings yet

- AlgecirasDocument7 pagesAlgecirasEvrenNo ratings yet

- NavAid Module 2.0Document21 pagesNavAid Module 2.0Kiel HerreraNo ratings yet

- Putra, 003 - 3035 - I Wayan Adi Pranata - GalleyDocument7 pagesPutra, 003 - 3035 - I Wayan Adi Pranata - Galleyeunike jaequelineNo ratings yet

- Beyond Risk - Bacterial Biofilms and Their Regulating ApproachesDocument20 pagesBeyond Risk - Bacterial Biofilms and Their Regulating ApproachesVictor HugoNo ratings yet

- Måttblad Bauer BK P7112BGM CatalogueB2010 0312 en A4 Chapter12Document54 pagesMåttblad Bauer BK P7112BGM CatalogueB2010 0312 en A4 Chapter12earrNo ratings yet

- Physics 158 Final Exam Review Package: UBC Engineering Undergraduate SocietyDocument22 pagesPhysics 158 Final Exam Review Package: UBC Engineering Undergraduate SocietySpam MailNo ratings yet

- Crawling Under A Broken Moon 05Document28 pagesCrawling Under A Broken Moon 05Maxim BorisovNo ratings yet

- Soil Pollution: Causes, Effects and Control: January 2016Document15 pagesSoil Pollution: Causes, Effects and Control: January 2016Nagateja MondretiNo ratings yet

- 520SL SLB Guide en USDocument2 pages520SL SLB Guide en USBruce CanvasNo ratings yet

- CASE REPORT On OsteomyelitisDocument30 pagesCASE REPORT On OsteomyelitisNirbhay KatiyarNo ratings yet

- TCS Ninja English Questions and AnswersDocument16 pagesTCS Ninja English Questions and AnswersVijayPrajapatiNo ratings yet

- DER Vol III DrawingDocument50 pagesDER Vol III Drawingdaryl sabadoNo ratings yet

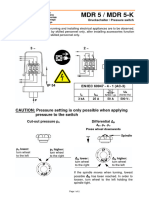

- Pressure Switch MDR5Document4 pagesPressure Switch MDR5Fidelis NdanoNo ratings yet

- User'S Manual: Questions?Document32 pagesUser'S Manual: Questions?gorleanosNo ratings yet

- 04 Vikram Pawar Volume 3 Issue 2Document18 pages04 Vikram Pawar Volume 3 Issue 2Juwan JafferNo ratings yet

- Composite EbookDocument285 pagesComposite Ebooksunilas218408100% (1)

- L-s20 Specification For Road Lighting InstallationDocument82 pagesL-s20 Specification For Road Lighting Installationzamanhuri junidNo ratings yet

- Equivalent Length Calculator - RevADocument10 pagesEquivalent Length Calculator - RevArkrajan1502No ratings yet

- (M. J. Edwards) The ''Epistle To Rheginus'' ValenDocument17 pages(M. J. Edwards) The ''Epistle To Rheginus'' ValenGlebMatveevNo ratings yet

- Bristow Part B EC155B1 Section 2 LimitationsDocument4 pagesBristow Part B EC155B1 Section 2 LimitationsrobbertmdNo ratings yet

NATURE - Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in Responses To Heart Failure Therapies (Chyou Et Al., 2024)

NATURE - Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in Responses To Heart Failure Therapies (Chyou Et Al., 2024)

Uploaded by

Marcelo TrOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NATURE - Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in Responses To Heart Failure Therapies (Chyou Et Al., 2024)

NATURE - Sex-Related Similarities and Differences in Responses To Heart Failure Therapies (Chyou Et Al., 2024)

Uploaded by

Marcelo TrCopyright:

Available Formats

nature reviews cardiology https://doi.org/10.

1038/s41569-024-00996-1

Review article Check for updates

Sex-related similarities and

differences in responses to

heart failure therapies

Janice Y. Chyou1,6, Hailun Qin 2,6

, Javed Butler3,4, Adriaan A. Voors 2

& Carolyn S. P. Lam 5

Abstract Sections

Although sex-related differences in the epidemiology, risk factors, Introduction

clinical characteristics and outcomes of heart failure are well known, Response to pharmacological

investigations in the past decade have shed light on an often overlooked therapy for HF

aspect of heart failure: the influence of sex on treatment response. Response to device therapy

for HF

Sex-related differences in anatomy, physiology, pharmacokinetics,

pharmacodynamics and psychosocial factors might influence the Response to cardiac

rehabilitation in HF

response to pharmacological agents, device therapy and cardiac

Challenges and opportunities

rehabilitation in patients with heart failure. In this Review, we discuss

the similarities between men and women in their response to heart Conclusions

failure therapies, as well as the sex-related differences in treatment

benefits, dose–response relationships, and tolerability and safety

of guideline-directed medical therapy, device therapy and cardiac

rehabilitation. We provide insights into the unique challenges faced

by men and women with heart failure, highlight potential avenues for

tailored therapeutic approaches and call for sex-specific evaluation

of treatment efficacy and safety in future research.

1

Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA. 2Department of Cardiology,

University of Groningen, University Medical Centre Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands. 3Department of Medicine,

University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS, USA. 4Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Dallas,

TX, USA. 5National Heart Centre Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore. 6These authors

contributed equally: Janice Y. Chyou and Hailun Qin. e-mail: carolyn.lam@duke-nus.edu.sg

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

Key points patients with HF. By examining studies focused on the efficacy and

safety of pharmacological interventions, device-based therapies

and cardiac rehabilitation (Fig. 1), we provide insights into the unique

•• Men and women with heart failure with reduced ejection challenges faced by male and female patients with HF and highlight

fraction derive similar benefits from pharmacotherapy with potential avenues for tailored therapeutic approaches.

renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin

inhibitors, β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and Response to pharmacological therapy for HF

sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. The cornerstone of HF guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) in

both men and women includes renin–angiotensin system (RAS) inhibi-

•• In patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, tors or angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), β-blockers,

treatment heterogeneity by sex has been observed with angiotensin mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) and sodium–glucose

receptor–neprilysin inhibitors and spironolactone, whereby women cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors18–20. Sex-specific differences in

seem to derive greater benefit than men. anatomy and physiology can influence the pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics of these HF medications21,22.

•• Optimal doses of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

inhibitors and β-blockers might be lower in women than in men, Sex-related differences in pharmacokinetics and

whereas adverse effects, such as dry cough and angio-oedema with pharmacodynamics

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, might be more common in Sex-related differences exist in the pharmacokinetics of HF medica-

women than in men. tions, including drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimina-

tion (Fig. 2). For drug absorption, women have a higher gastric pH and

•• Among patients with left bundle branch block, women derive greater slower gastric emptying time than men, which can delay and/or reduce

benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy at a shorter QRS the absorption of drugs that require an acidic environment21. Body

duration for reducing mortality than men. composition, organ blood flow, plasma volume and protein binding all

influence how drugs are distributed throughout the body. In general,

•• In relation to the patient-oriented outcomes of quality of life and women have lower body weight, lower total body water (intracellular

functional status, women derive similar benefits from baroreceptor and extracellular) content, lower plasma volume and smaller organ

activation therapy but less benefit from mitral valve intervention size than men, but have a higher proportion of body fat23. These differ-

compared with men. ences might contribute to a larger volume of distribution, faster onset

and longer duration of action for lipophilic drugs in women than in

•• Women with heart failure might derive greater benefit from cardiac men (and, conversely, a smaller volume of distribution and relatively

rehabilitation than men but have lower rates of enrolment and higher concentrations for hydrophilic drugs in women than in men).

adherence. Sex-related differences in the activity of hepatic enzymes might also

influence treatment responses, given that many HF drugs are metab

olized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes, and some CYP isoen-

Introduction zymes have been shown to differ by sex (particularly CYP3A4, which

The sex-related differences in heart failure (HF) are well known1,2. Tra- has higher activity levels in women)24,25. Women generally have lower

ditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity renal blood flow, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and tubular secre-

and smoking have a more potent influence on the risk of HF in women tion, transport and reabsorption than men26,27. Therefore, drugs that

than in men3–7. Additional sex-specific risk factors in women are related are primarily inactivated or excreted by the kidneys might be cleared

to sex hormones, pregnancy and gestational complications, propen- more slowly in women than in men.

sity and treatment for breast cancer, as well as autoimmune diseases In healthy volunteers given a single oral dose (5 mg) of the RAS inhib-

and the associated inflammatory and immune system milieu8. HF in itor ramipril, women showed a higher area under the concentration–

women is marked by pathophysiological predominance of endothelial time curve (AUC/kg) of the active metabolite ramiprilat than men28.

inflammation and microvascular dysfunction compared with HF in Plasma concentrations of the RAS inhibitor losartan were approxi-

men9–11. The epidemiology of HF is notable for a higher prevalence of mately two times higher in women than in men with hypertension,

HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in women, higher preva- but the concentrations of the active metabolites of losartan were

lence of non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy among women with HF, female similar across both sexes29. Although the pharmacokinetics of the

preponderance in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and the sex-specific RAS inhibitor irbesartan were not affected by sex in healthy partici-

entity of peripartum cardiomyopathy12–14. Compared with men with pants, women with hypertension had higher plasma irbesartan lev-

HF, women with HF are generally older, more likely to be physically els than men29,30. Among healthy young men and women receiving

frail, more symptomatic and have worse self-reported health status, irbesartan 75 mg for 4 weeks, which increased to 150 mg for a further

yet better survival15,16. Therefore, although among patients with HF, 4 weeks, women had increased sensitivity to RAS modulation and

women outlive men, their additional years of life are of poorer quality17. thus might require lower dosages of irbesartan than men to achieve

Extensive research has been dedicated to understanding these a similar response31.

sex-related differences in epidemiology, risk factors, clinical char- Compared with men, women have a lower activity of the CYP2D6

acteristics and outcomes in HF, but investigations in the past decade enzyme, which metabolizes the β-blocker metoprolol, and thus a slower

have shed light on an often-overlooked aspect: the influence of sex on body clearance, greater exposure and higher plasma levels of metopro-

treatment responses. In this Review, we comprehensively evaluate the lol after normalizing for body weight32–34. In healthy individuals receiv-

current literature on sex-related differences in treatment response in ing metoprolol 100 mg twice daily for a total of nine doses, women had

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

a Pharmacological therapy b Device therapy c Cardiac rehabilitation

Counselling

Autonomic Electrical conduction Mental health Education

Medication

• ACE inhibitors, nervous system • Defibrillation

ARBs, ARNI • Modulation • Pacing

• β-Blockers • Resynchronization

• MRAs Stress Physical activity

• SGLT2 inhibitors

Anatomical remodelling

• Modification Lifestyle modification

• Haemodynamic support

Women have: Anatomy: Cardiac electrical system: • Lower self-reported physical function

• Lower body weight • Narrower QRS complexes • Increased prevalence of frailty

• Lower total body water content • Longer QTc interval • Increased fear of exercise

• Greater body fat percentages Anatomy: • More comorbidities

• Smaller organ size • Smaller LV mass and volume • Older age at heart failure diagnosis

• Smaller body surface area • Thinner myocardial walls • Greater psychological burdens

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: • Predisposition to LV concentric remodelling

• Higher gastric pH Cardiac autonomic nervous system:

• Slower gastric emptying time • Higher resting heart rates

• Different enzyme activity levels • Lower sympathetic activities

Fig. 1 | Sex-specific considerations in heart failure therapy. Women are under- inhibitors. Sex-related differences in anatomy and physiology can influence the

represented in randomized clinical trials and some therapies for heart pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of heart failure medications.

failure are underutilized in women. Encouragingly, these gaps have gradually b, The three major domains of therapeutic targets for device therapies in heart

narrowed over time. In approximately 70% of trials on heart failure therapies, failure are the electrical conduction system, anatomical remodelling and the

outcome data were reported by sex, and only a minority (5%) of the trials autonomic nervous system. Therapeutic interventions have primary targets

detected significant variation in treatment effects by sex. a, The cornerstone but can have additional effects on other domains. c, Cardiac rehabilitation is a

of heart failure guideline-directed medical therapy in both men and women comprehensive non-pharmacological intervention that is underutilized among

includes loop diuretics, renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, angiotensin women and adherence is particularly low in women. ACE, angiotensin-converting

receptor–neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), β-blockers, mineralocorticoid enzyme; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; LV, left ventricular.

receptor antagonists (MRAs) and sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2)

higher maximum plasma concentrations (146 ng/ml versus 85.5 ng/ml) from treatment with the ARB candesartan up to a higher left ventricular

and AUC values (867 µg/h/l versus 417 µg/h/l) of metoprolol than men32. ejection fraction (LVEF) range than men57.

Similarly, a clinical trial simulation model found that, after receiving A significant differential treatment response between men and

100 mg of metoprolol, healthy men had a faster metoprolol absorption women was found in two trials in patients with HF with LVEF ≥45%. In the

and clearance rates than women35. The pharmacokinetics of 100 mg of PARAGON-HF trial36, sex was an independent treatment effect modifier

metoprolol in men were roughly similar to the pharmacokinetics (unadjusted P for interaction 0.017), wherein women derived greater

of 50 mg of metoprolol in women35. benefit from sacubitril–valsartan versus valsartan for the primary com-

Importantly, in prospective, randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) posite outcome of total HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular death

assessing GDMT in patients with HF, achieved doses of ARNI 36,37, (rate ratio for the primary outcome 0.73, 95% CI 0.59–0.90) compared

β-blockers38 and vericiguat39 were similar between men and women. with men (rate ratio 1.03, 95% CI 0.84–1.25). However, men had a greater

Therefore, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic differences improvement in the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire clini-

between men and women do not seem to translate into clinically mean- cal summary score than women in response to sacubitril–valsartan

ingful differences in achievable doses of GDMT for HF, at least in the treatment, and similar improvements in New York Heart Association

context of prospective clinical trials. (NYHA) class and renal function were observed between women and

men36. No sex-related differences in the effect of spironolactone on

Sex-related differences in treatment benefit with GDMT the primary composite outcome (death from cardiovascular causes,

Although sex differences in the response to pharmacological HF ther- aborted cardiac arrest or HF hospitalization) were found in the overall

apy are important to consider, the similarities are equally important. TOPCAT population (P for interaction 0.99)58. However, when restricted

In the big picture, GDMT for HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) to the TOPCAT-Americas cohort (which included only the participants

is strongly indicated in both men and women on the basis of consist- from Argentina, Brazil, Canada and the USA), sex was found to signifi-

ent overall treatment benefits in both sexes demonstrated in large cantly modify the treatment effect of spironolactone on all-cause death

outcomes trials40–47, including for angiotensin-converting enzyme (P for interaction 0.024); when compared with placebo, spironolactone

(ACE) inhibitors47, angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs)48, ARNI42, reduced all-cause death in women (by 34%), but not in men59.

β-blockers49, MRAs50, SGLT2 inhibitors44,51 and ivabradine52. Similarly, In the PARAGON-HF trial36, sex-specific spline analyses of treat-

in patients with HFpEF, no significant treatment heterogeneity by sex ment effect across the LVEF spectrum showed that the benefit of

has been observed for the primary outcomes in large clinical trials sacubitril–valsartan treatment seemed to extend to a higher LVEF

of ACE inhibitors or ARBs53–55, or SGLT2 inhibitors56 (Fig. 3; Table 1). range in women than in men, both for the primary composite end point

However, in the CHARM programme, women seemed to derive benefit and for total HF hospitalizations (Table 1). By contrast, in men, the

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

Higher in men Fig. 2 | Sex-related differences in

Factors affecting drug distribution pharmacokinetics. In general, compared

and metabolism Drug with men, women have lower body weight,

• Body surface area, organ size and therapy total body water content and cardiac output,

blood flow

• Total body water content and higher gastric pH and slower gastric emptying

plasma volume time, smaller organ size and body surface

• Volume of distribution for area, and greater body fat percentages, all of

water-soluble drugs

which affect the absorption and distribution

Factors affecting drug distribution of drugs. The sex-specific differences in the

and metabolism Higher in women activity of metabolizing enzymes in the liver

• Cardiac output, lung volume

Factors affecting drug metabolism and the lower glomerular filtration rate in

• Functional capacity

• Levels of CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 • CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP3A4 women might also affect drug elimination.

enzyme activity enzyme activity

• Xanthine oxidase,

CYP, cytochrome P450; eGFR, estimated

• Levels of UGTs, methyltransferase,

N-acetyltransferases glomerular filtration rate; UGTs, uridine

sulfotransferase

diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases.

Factors affecting drug elimination Factors affecting drug elimination

• Liver metabolism • Elimination half-life

• Renal blood flow, eGFR

• Tubular secretion and reabsorption Factors affecting drug distribution

• Body fat content

Factors affecting drug absorption • Volume of distribution for

• Gastric acid secretion and gastric lipophilic drugs

emptying

• Gastrointestinal transit time and rate

drug was only beneficial in those with a lower LVEF36. In the TOPCAT of patients in the DIG study, among whom only 20% were women, and

trial60, the interaction between treatment and LVEF (stronger benefit thus statistical power was insufficient for further sex-specific analyses.

in patients with a lower LVEF) for the primary outcome also seemed to Although the sex-related differences described above are nota-

differ by sex, wherein women across the LVEF spectrum benefited from ble, some of these findings are from post hoc subgroup analyses of

spironolactone treatment, whereas in men, the benefit was limited trials that had neutral results for their primary outcome analyses

to those with a lower LVEF (P for interaction 0.077). A similar pattern (PARAGON-HF, TOPCAT and CHARM-Preserved)36,57,58. Furthermore,

was observed in the CHARM-Preserved trial with candesartan for the the overwhelming evidence from large clinical trials of neurohormonal

primary composite outcome of first occurrence of HF hospitalization agents in patients with HF across the LVEF spectrum indicate similar

or cardiovascular death57. These observed sex-related differences in effect modification by LVEF in men and women (greater benefit at

treatment response across the LVEF spectrum in patients with HF, which lower LVEF) for the primary end point, calling into question the clini-

were consistent across different neurohormonal drugs (ARNI, MRAs cal significance of sex-related differences in component or secondary

and ARBs), have been postulated to be related to known sex differences end points. Conversely, the under-representation of women in clinical

in cardiac remodelling with age and risk factors such as hypertension. trials, especially in smaller HF studies (CONSENSUS68, US Carvedilol

Greater concentric cardiac remodelling in women resulted in smaller HF study69 and RALES70) might limit the ability to detect sex-related

left ventricular volumes and higher LVEF (higher stroke volume for a differences by interaction testing.

given left ventricular end-diastolic volume) in women than in men61. In aggregate, the evidence suggests that sex modifies the response

Indeed, in the general population, the distribution of LVEF is shifted to ARNI and spironolactone in patients with HFpEF. Indeed, there are

towards higher values in women than in men16,62,63, with a normal LVEF in now sex-specific considerations for GDMT in patients with HFpEF in

older women being closer to 60% compared with 55% in men. Therefore, the most recent American College of Cardiology Expert Consensus

women with HF and a LVEF of 50% have more adverse cardiac remodel- statement19, which recommends that the use of ARNI and spirono-

ling or contractile dysfunction than men, and thus might derive more lactone be considered across the entire LVEF spectrum in women

benefit from neurohormonal inhibitor therapies whose mechanism with HFpEF.

of action is promoting reverse cardiac remodelling64. Indeed, in the

PARAMOUNT trial65, women with HFpEF had greater systolic dysfunc- Sex-related differences in dose–response relationships with

tion (lower tissue S′ velocity), despite having a higher LVEF, than men GDMT

with HFpEF. In a large, prospective, multinational, observational HF study con-

Important sex-related differences in the response to pharma- ducted in patients across Europe, the lowest risk of the composite of

cological HF therapy have also been shown with digoxin. A post hoc, hospitalization for HF or all-cause death was observed in women with

sex-specific subgroup analysis of the DIG study66 found that treatment HFrEF who had received ~40% of the recommended target doses of

with digoxin significantly increased all-cause mortality among women ACE inhibitors and ARB, whereas in men with HFrEF, the lowest risk

but not among men (P for interaction 0.034). Women had greater serum was found in those who achieved 100% of the recommended target

digoxin concentrations than men at 1 month after treatment initiation doses71. For β-blockers, women with HFrEF had the lowest risk of the

(1.05 ng/ml versus 0.96 ng/ml; P = 0.003), and serum digoxin concen- composite outcome at ~60% of the recommended target doses, whereas

trations exceeding the upper limit of therapeutic range (>2.0 ng/ml) the lowest risk in men with HFrEF was observed at 100% of the target

were found in 4% of women, twice the percentage found in men67. How- doses71. These findings were validated in a separate prospective, mul-

ever, the serum digoxin concentration was only tested in a subgroup tinational, observational HF study in patients across Asia71. Although

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

hypothesis-generating, these observational, non-randomized results adverse drug reactions in women might be attributable to sex-related

should be interpreted with caution. differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the

Two RCTs compared the effects of a low dose versus a high dose of drug treatments, resulting in higher doses of drugs per kilogram of

an ACE inhibitor and an ARB on clinical outcomes in patients with HFrEF. body weight in women than in men; to biological differences, such as

The ATLAS trial72 compared a low dose (2.5–5.0 mg per day) versus a longer corrected QT interval in women or differences in circulating

high dose (32.5–35 mg per day) of lisinopril in patients with HFrEF. hormone levels; or to greater polypharmacy in women, with the asso-

Patients receiving the higher dose had a significant 12% lower risk of ciated increased potential for drug–drug interactions76,78. Indeed, a

death or hospitalization for any reason and 24% fewer hospitalizations report published in 2023 highlighted that more women than men with

for HF. Interestingly, no additional benefit of the high dose of lisinopril HF were prescribed medications that might cause or exacerbate HF

was found in women compared with the low dose, and the positive (such as inhaled sympathomimetics, diltiazem and antidepressants)79.

results were completely driven by the effects seen in men. The HEAAL Despite a 1.5 to 1.7 times higher likelihood of adverse drug reactions

trial73 compared the effects of losartan 50 mg versus losartan 150 mg in women than in men80, only 11 (7%) clinical trials of pharmacological HF

on death or HF hospitalization in patients with HFrEF. Patients who therapies have found sex-specific adverse drug reactions21,74,81. Among

were assigned to the higher dose had a significantly lower event rate them, three studies found that women have a higher risk of adverse reac-

than those assigned to the lower dose, and this result was completely tions with ACE inhibitors81. In a post hoc analysis from the SOLVD trial82,

driven by a beneficial effect of the higher dose in men but not in women dry cough after taking enalapril occurred approximately 1.4 times more

(P for interaction 0.018)73. frequently in women than in men. In a retrospective cohort study from

In aggregate, these data suggest that the optimal doses of ACE the USA, the cumulative incidence of new-onset angio-oedema with

inhibitors or ARBs and β-blockers might be lower in women than in ACE inhibitor treatment in patients with HF was more than twofold

men with HF. However, given that the trials that formed the evidence higher in women than in men83. No sex-related differences in adverse

base for HF management guideline recommendations used the same drug reactions were observed in clinical trials of ARBs and β-blockers81.

target doses for men and for women, sex-specific target doses cannot A pooled analysis of three landmark trials of MRAs (RALES, EMPHASIS-HF

be recommended at this time. Nonetheless, future trials should be and TOPCAT) showed no sex-specific differences in adverse drug reac-

designed with the consideration of potential sex-specific differences tions (all P for interaction >0.1), including worsening renal function and

in target doses to best optimize the benefit–risk ratio in both women hyperkalaemia43. Moreover, a small study including 134 patients with HF

and men with HF. found that a comparable number of men and women treated with

spironolactone withdrew from the study because of hyperkalaemia or

Tolerability of GDMT in men and women worsening renal function (and gynaecomastia in men)84. In the DAPA-HF

Women are known to experience more adverse effects from cardiovas- and DELIVER trials, which assessed SGLT2 inhibitors, men treated with

cular medications and generally have a higher rate of hospital admis- dapagliflozin were more likely to experience severe adverse events,

sions for adverse drug reactions than men74–77. The increased risk of but women were more likely to experience adverse events leading to

Men Similarities between men and women Women

• Sacubitril–valsartan reduced the risk • Similar response to ACE inhibitors, • Higher mortality with digoxin

of hospitalization for heart failure to a ARBs, ARNI, β-blockers, MRAs and • Lower optimal dose for ACE inhibitors,

lesser degree in men with HFpEF SGLT2 inhibitors in HFrEF ARBs and β-blockers

than in women with HFpEF • Similar response to ACE inhibitors, • Higher incidence of dry cough and

• Spironolactone did not reduce ARBs and SGLT2 inhibitors in HFpEF angio-oedema with ACE inhibitors

all-cause death in men with HFpEF, • Largely similar in achieved dose and • Lower rate of enrolment and adherence

but reduced all-cause death in adherence in cardiac rehabilitation

women with HFpEF • Predominantly similar in adverse • Might benefit more from cardiac

drug reactions rehabilitation

Fig. 3 | Sex-based considerations in the response to pharmacological and and spironolactone therapies in men and women with HFpEF are different.

non-pharmacological therapies for heart failure. Men and women with The achieved dose and adherence to heart failure guideline-directed medical

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) have similar treatment therapies are largely similar in men and women. Women have lower optimal

response to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin- doses of ACE inhibitors, ARBs and β-blockers than men. Adverse drug reactions

receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), are predominantly similar in both sexes. However, women have a higher

β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) and sodium–glucose incidence of dry cough and angio-oedema with ACE inhibitors than men.

cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. No evidence of treatment heterogeneity In general, women have lower rates of enrolment into clinical trials and treatment

by sex has been observed for the primary outcomes of large clinical trials of adherence than men, but women might derive more benefit from cardiac

ACE inhibitors or ARBs and SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure rehabilitation than men.

with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). However, the responses to ARNI

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

Table 1 | Landmark clinical trials of drug therapy in men and women with HF

Trial (year) Drug Number Mean Mean Primary end point RR or HR (95% CI) P for interaction

of patients age LVEF

(% women) (years) (%) Men Women Sex Treatment Treatment,

or sex and sex and

LVEF LVEF

ACE inhibitors

CONSENSUS (1987)a Enalapril 253 (30) 71 ≤35 Mortality 0.41 (0.16–0.58) 1.01 (0.59–1.73) NA NA NA

(refs. 68,231)

SOLVD-Treatment Enalapril 2,569 (20) 61 25 Mortality Favourable treatment outcomes in NA NA

(1991)232,233 both sexes, but the effect seemed

to be greater in men

Meta-analysis of ACE inhibitors 7,105 (22) NA NA Mortality 0.76 (0.65–0.88) 0.79 NA NA NA

32 RCTs (1995)47 (0.59–1.06)

Mortality or 0.63 (0.55–0.73) 0.78 NA NA NA

hospitalization (0.59–1.04)

Angiotensin-receptor blockers

Val-HeFT (2005)234 Valsartan 5,010 (20) 63 27 Mortality and 0.84 (0.67–1.06) 0.87 NS NA NA

morbidity (0.78–0.98)

Non-fatal morbidity 0.74 (0.56–0.99) 0.72 NS NA NA

(0.61–0.84)

Hospitalization 0.78 (0.59–1.04) 0.71 NS NA NA

for HF (0.60–0.83)

CHARM Candesartan 7,599 (32) 66 39 Cardiovascular 0.84 (0.76–0.92) 0.84 0.9939 0.0146b; 0.0649

programme death (0.73–0.97) 0.73c

(2007)53,57

Hospitalization Reference 0.83

for HF group (0.76–0.91)

Mortality Reference 0.77 NA 0.65c NA

group (0.69–0.86)

I-PRESERVE Irbesartan 4,128 (60) 71 60 Mortality or 0.96 (0.83–1.12) 0.94 0.78 NA NA

(2008)54,235 hospitalization (0.82–1.08)

for specified

cardiovascular cause

Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors

PARADIGM-HF Sacubitril– 8,399 (22) 64 29 Cardiovascular Significant Significant 0.63 NA NA

(2014)42 valsartan death or benefitd benefitd

hospitalization

for HF

Cardiovascular Significant Trend towards 0.92 NA NA

death benefitd benefitd

PARAGON-HF Sacubitril– 4,769 (52) 72 57 Cardiovascular 1.02 (0.83–1.24) 0.73 0.0225 NA NA

(2020)36 valsartan death or (0.60–0.90)

hospitalization

for HF

Mortality 0.95 (0.77–1.17) 0.99 0.8703 NA NA

(0.79–1.24)

Pooled analysis Sacubitril– 13,195 (33) 67 39.7 Cardiovascular 0.86 (0.79–0.93) 0.79 0.3452 0.0424b 0.032

(PARADIGM and valsartan death or (0.70–0.91)

PARAGON-HF) hospitalization

(2020)57,236 for HF

β-Blockers

US Carvedilol HF Carvedilol 1,094 (23) 58 22 Mortality 0.41 (0.22–0.80) 0.23 NS NA NA

Study (1996)69 (0.07–0.69)

CIBIS II (2001)237 Bisoprolol 2,647 (19) 61 28 Mortality Reference 0.64 NA NA NA

group (0.47–0.86)

MERIT-HF Metoprolol 3,991 (22.5) 64 28 Mortality Risk reduction Risk reduction NS NA NA

(1999)49,238 18% 21%

COPERNICUS Carvedilol 2,289 (20) 63 20 Mortality 0.65 0.65 NS NA NA

(2001)239

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

Table 1 (continued) | Landmark clinical trials of drug therapy in men and women with HF

Trial (year) Drug Number Mean Mean Primary end point RR or HR (95% CI) P for interaction

of patients age LVEF

(% women) (years) (%) Men Women Sex Treatment Treatment,

or sex and sex and

LVEF LVEF

β-Blockers (continued)

Pooled data β-Blockers 8,927 (NA) NA NA Mortality Similar survival benefit in men and women

(CIBIS II, MERIT-HF

and COPERNICUS)

(2002)49

MRAs

RALES (1999)70 Spironolactone 1,663 (27) 65 25 Mortality Significant Significant NS NA NA

reductiond reductiond

EMPHASIS-HF Eplerenone 2,737 (22) 69 26 Cardiovascular Significant Significant 0.36 NA NA

(2011)50 death or hospitaliza reductiond reductiond

tion for HF

TOPCAT- Spironolactone 1,767 (49.9) 71 58 Cardiovascular 0.85 (0.67–1.08) 0.81 0.84 NA NA

Americas (2019)59 death, aborted (0.63–1.05)

cardiac arrest, or

hospitalization

for HF

Mortality 1.06 (0.81–1.39) 0.66 0.024 NA NA

(0.48–0.90)

Pooled analysis MRAs 6,167 (31) 69 35.3 Cardiovascular 0.70 (0.63–0.77) 0.71 0.8089 0.0074b 0.0682

(RALES, death or (0.60–0.84)

EMPHASIS-HF hospitalization

and TOPCAT- for HF

Americas) (2020)57

SGLT2 inhibitors

DAPA-HF Dapagliflozin 4,744 (23) 66 31 Cardiovascular 0.73 (0.63–0.85) 0.79 0.67 NA NA

(2019)44,240 death or (0.59–1.06)

worsening HF

EMPEROR- Empagliflozin 3,730 (24) 67 27 Cardiovascular 0.80 0.59 NS NA NA

Reduced (2020)51 death or (0.68–0.93) (0.44–0.80)

hospitalization

for worsening HF

EMPEROR- Empagliflozin 5,988 (45) 72 54 Cardiovascular 0.81 (0.69–0.96) 0.75 0.536 Men, 0.878

Preserved (2022)241 death or (0.61–0.92) 0.402b;

hospitalization women,

for worsening HF 0.587b

DELIVER (2022)242 Dapagliflozin 6,263 (44) 71 54 Cardiovascular 0.82 (0.71–0.96) 0.81 NS NA NA

death or (0.67–0.97)

worsening HF

Pooled analysis Dapagliflozin 11,007 (35) 70 44 Cardiovascular 0.78 (0.70–0.86) 0.80 0.77 0.71b 0.86

(DAPA-HF death or (0.68–0.94)

and DELIVER) worsening HF

(2022)85,243

Meta-analysis (five SGLT2 20,725 (36) NA NA Cardiovascular 0.78 (0.73–0.85) 0.74 0.45 NA NA

RCTs) (2022)56 inhibitors death or (0.66–0.84)

hospitalization

for HF

Digoxin

DIG (1997)66,244 Digoxin 6,800 (22) 63 28 Mortality 0.93 (0.85–1.02) 1.23 0.014 NA NA

(1.02–1.47)

DIG-PEF (2006)245 Digoxin 988 (41) 67 55 Mortality Reference 0.59 NA NA NA

group (0.43–0.82)

Hospitalization Reference 1.06 NA NA NA

for HF group (0.75–1.51)

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; HF, heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; NA, not available; NS, not significant; RCT,

randomized controlled trial; RR, relative risk; SGLT2, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2. aAt 6 months, 66 of the 178 men and 22 of the 75 women had died; enalapril reduced mortality by 51%

in men and 6% in women (small number of women and wide confidence intervals). bInteraction between treatment and LVEF. cInteraction between sex and LVEF. dResults of sex subgroup

analyses were reported in forest plots; quantitative data were not provided.

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

study drug cessation as well as study drug cessation for any reason85. Anatomical size and anatomical remodelling. Sex-related differences

No sex-related differences in adverse events were observed in the exist in anatomical size and anatomical remodelling. In the general pop-

dapagliflozin group (all P for interaction >0.1)85. ulation, women have smaller left ventricular cavities, greater diastolic

Notably, for the vast majority of HF clinical trials, sex-stratified dysfunction, and more concentric hypertrophy on echocardiography

adverse events were not reported, and this aspect has not improved studies than men95–97. Cardiac MRI data reveal that left ventricular vol-

over time81. Data safety monitoring in future clinical trials in patients umes indexed to body surface area are smaller in women than in men,

with HF should account for potential sex-related differences in adverse and that women have higher LVEF due to a higher stroke volume for a

events and they should be reported in a sex-disaggregated manner86. given left ventricular end-diastolic volume61. Cardiac remodelling in

the setting of HF is also influenced by older age and higher proportions

Response to device therapy for HF of non-ischaemic aetiology in women than in men12.

Sex-related differences in device therapies for HF might relate to dif-

ferences in biology, prevalence of associated conditions, therapeutic Cardiac autonomic nervous system. Premenopausal women have

responses, adverse procedural events and systemic barriers in thera- higher resting heart rates than men, consistently seen between the ages

peutic adoption. Therapeutic targets for device-based therapies for HF of 20 and 50 years and attenuating thereafter93,98. In healthy volunteers

fall into three major domains: the cardiac electrical system, anatomical aged <40 years, women had lower sympathetic activity (quantified

remodelling and the autonomic nervous system (Fig. 1). Sex-based by low-frequency component of heart rate variability) than men99.

considerations in HF device therapy incorporate domain-specific bio- In a middle-aged population (age 50 ± 6 years), baroreflex sensitivity

logical differences as well as cross-domain differences in risk factors, was lower in women without oestrogen therapy than in men, but was

pathophysiology, epidemiology, outcomes, symptoms, quality of life not significantly different between women taking oestrogen therapy

(QoL), functional capacity and challenges in clinical trial representation and men100,101.

and therapeutic adoption (Fig. 4).

Sex-related differences in response to device therapies

Sex-related biological differences Implantable cardioverter–defibrillator. Implantable cardioverter–

Cardiac electrical conduction system. Sex differences exist in cellular defibrillators (ICDs) are indicated for primary and secondary preven-

electrophysiology and in surface electrocardiography. On the cellular and tion of sudden cardiac death102,103. Among eligible patients with HF,

tissue level, sex differences exist in the expression of ion channels, ICDs are underutilized in all sexes104,105, but even more so in women16,

which are further modulated by sex hormones. Human cardiac tissues even after accounting for age39 and comorbidities106–111. Low referral

from donor hearts revealed reduced expression of potassium channel rates, financial concerns and inadequate knowledge about ICDs have

subunits involved in cardiac repolarization in the heart of female indi- been reported as potential reasons for ICD underutilization104,112,113. ICD

viduals compared with the heart of male individuals87. Sex hormones counselling and strategies to improve referral might help to address

(most notably oestradiol and testosterone) differentially influence sex-related differences in utilization. Among patients with HF who are

the ion channels, with implications for cardiac repolarization and eligible for an ICD, women received ICD counselling less frequently

excitability88. On surface electrocardiography, women have a shorter than men (19.3% versus 24.6%; P < 0.001); however, among those who

PR interval, a shorter effective refractory period of the atrioventricular received counselling, women and men received an ICD at similar

node, and a narrower QRS complex than men89–91. QT intervals cor- rates (63.1% versus 62.3%)114, suggesting that equitable ICD counsel-

rected for resting heart rates are approximately 20 ms longer in women ling might be a potential tool to address sex-related disparities in

than in men92. Significant sex differences in the QTc interval start to be ICD utilization. The use of a screening tool115 or electronic health

seen after puberty, persist through adulthood but attenuate in older record alert116 has been shown to improve referral of ICD-eligible

age, suggestive of the influence of sex hormones92–94. patients, among whom point-of-care alerts through electronic health

ain differe

-dom nc

oss es

Cr Cardiac electrical conduction Anatomical Autonomic modulation

ic al differe

g nc

olo es • Cardiac resynchronization therapy • LV assist device • Baroreflex activation therapy

Bi • Implantable cardioverter–defibrillator • Mitral valve procedure • Vagal nerve stimulation

i ce the rap

ev ie

D

• Narrower QRS complexes • Smaller LV mass • Higher resting heart rates

Domains of • Longer QTc (premenopause) • Smaller LV volume (premenopause)

therapeutic • Thinner myocardial walls • Lower sympathetic activity

target • Predisposition to LV concentric (healthy volunteers,

remodelling premenopause)

• Risk factors • Pathophysiology • Symptoms • Therapeutic adoption

• Epidemiology • Outcomes • Quality of life • Clinical trial representation

Fig. 4 | Factors influencing sex-related differences in device therapies for well as cross-domain differences in risk factors, pathophysiology, epidemiology,

heart failure. Sex-based considerations in response to device therapy for heart outcomes, symptoms, quality of life, functional capacity and challenges in

failure incorporate considerations of domain-specific baseline differences as clinical trial representation and therapeutic adoption. LV, left ventricular.

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

records had a modestly greater effect in improving referral rates in Landmark RCTs evaluating CRT for HFrEF collectively established

women than in men, mitigating the sex-based gap otherwise seen the benefits of CRT in improving clinical outcomes and reducing mor-

with under-referral of women (in the study comparison group without tality, HF hospitalizations and HF symptoms, and improving QoL,

electronic alert)116. 6-min walking distance (6MWD)138–142 and left ventricular reverse

In landmark studies of the efficacy and indication for ICD thera- remodelling143 (Table 3). However, definitive RCT-level evidence for

pies for primary prevention in patients with HFrEF, women comprised sex-specific treatment response to CRT is not feasible because none of

only 10–29% of the study populations117–123 (Table 2). Sex-specific data the studies was powered to assess treatment response by sex specifi-

from the MADIT II trial118 and secondary analyses of the MUSTT124, cally given that women were under-represented (17–33% of the study

SCD-HeFT125 and DEFINITE126 trials found no significant sex-specific population in the landmark CRT trials)138–144. Although men and women

differences in the benefit derived from ICD. Although pooled analyses both benefit from CRT, data from post hoc analyses and registry studies

of several landmark studies have questioned the benefit of ICDs for suggest that women might derive more benefit than men, in terms of

reducing all-cause mortality in women127–129, a definitive interpreta- both clinical outcomes145–147 and left ventricular reverse remodelling148.

tion of findings from these pooled analyses127–129 has been difficult Baseline patient characteristics in trials of CRT are notable, with women

given the heterogeneity of the included trials, particularly with regard having shorter stature, smaller left ventricular end-diastolic diameter,

to the length of follow-up and the study population composition more LBBB and more non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy (less often ischae-

(especially concerning ischaemic versus non-ischaemic aetiology and mic cardiomyopathy) than men144,145,149. An analysis of the MADIT-CRT

concomitant use of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT)). study148 identified six baseline characteristics predictive of a favourable

A retrospective analysis of 14 European registries of ICD use for CRT response: female sex, LBBB, no previous myocardial infarction,

primary prevention revealed that women had lower mortality and fewer BMI <30 kg/m2 and smaller left atrial volume index. However, in a

appropriate ICD shocks than men after adjusting for age, ischaemic meta-analysis of five RCTs (CARE-HF, MIRACLE, REVERSE, MIRACLE

cardiomyopathy, LVEF ≤25% and concomitant CRT130. In a comparison ICD and RAFT), QRS duration was the only independent predictor

of an older US patient population from the National Cardiovascular of a reduction in all-cause mortality with CRT, and QRS duration and

Data Registry of ICD for primary prevention with propensity-matched height were independent predictors of CRT benefits in the composite

patients from the GWTG-HF registry without ICD, similar rates of reduc- outcome of all-cause mortality or HF hospitalization149.

tion in mortality were found in men and women with ICDs compared The extent and mitigation of left ventricular electrical delay are

with matched counterparts without ICDs, highlighting the similar central to the considerations for CRT150,151. Longer QRS duration in

benefit of ICD treatment in both sexes131. Appropriate shock was a LBBB (especially ≥150 ms) is associated with increased survival with

strong predictor of mortality in both men (HR 2.61, 95% CI 1.82–3.74; CRT-D in both sexes147. Among recipients of CRT-D in large national

P < 0.0001) and women (HR 5.99, 95% CI 2.75–13.02; P <0.0001)132. databases, women with LBBB had even greater mortality reduction

Of note, women received fewer inappropriate therapies than men than men with LBBB147,152. Women with LBBB derive benefit at a shorter

(9.2% versus 13.5%; P = 0.006)132. QRS duration than men with LBBB153,154, prompting ongoing discus-

Finally, although the initial RCTs establishing efficacy of ICDs sions for further sex-specific considerations for recommendations

as primary prevention therapy in patients with HF were based on for CRT155,156. The AdaptResponse RCT utilized sex-specific inclusion

transvenous ICD systems, the subcutaneous ICD system is a contem- criteria for QRS duration, which is likely to have contributed to the high

porary alternative for ICD therapy in individuals without need for portion of women (43.4%) in the trial157, paving the way for utilization

pacing. Data from the PRAETORIAN trial133 established that the sub- of sex-specific criteria158 in future clinical trials and in clinical practice.

cutaneous ICD was non-inferior to the transvenous ICD with respect With regard to the aetiology of the cardiomyopathy, a meta-

to device-related complications and the number of inappropriate analysis revealed that, whereas no sex-based differences were seen in

shocks. The UNTOUCHED trial134 demonstrated high safety and effi- CRT recipients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy, among CRT recipients

cacy, and a low rate of inappropriate shocks with contemporary with non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, women had greater observed

second-generation and third-generation subcutaneous ICD systems. benefit than men149. A retrospective analysis of CRT recipients with

No significant differences in survival or inappropriate shock rates were non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and LBBB suggests that the com-

seen between men and women in the IDE or EFFORTLESS registries135. plex interplay between QRS duration and heart size might explain

the observed sex-based differences in CRT response, in which a more

Cardiac resynchronization therapy. CRT can be part of a pacemaker favourable CRT response (defined in this study as an increase in LVEF,

system (CRT-P) or part of a defibrillator system (CRT-D). Guideline as determined by echocardiography) was seen in women, but women

recommendations for CRT are currently sex-neutral. In HFrEF, CRT also had a larger baseline index of QRS duration to heart size (with

is indicated in patients with NYHA class II, III or ambulatory IV HF generally smaller heart size than men), such that normalization of QRS

despite optimal pharmacological treatment, LVEF ≤35%, left bundle duration for heart size resolved the sex-based differences associated

branch block (LBBB) with a prolonged QRS duration of ≥150 ms, and in with the response to CRT159. A subsequent study extended this concept,

sinus rhythm as a class I recommendation in both the American136 and noting that normalization of QRS duration to left ventricular dimension

European137 guidelines. Class IIa recommendations in the American improved the prediction of survival after CRT implantation160.

guidelines136 include a QRS duration of 120–149 ms in sinus rhythm, Despite the benefits and indications, CRT is under-implemented

or atrial fibrillation that requires ventricular pacing or meets CRT in both men and women161–166. Estimates of European inhabitants with

criteria; atrioventricular nodal ablation or pharmacological rate con- HFrEF and LBBB167 qualifying for CRT and statistics of utilization of

trol will allow near complete ventricular pacing with CRT. Class IIa cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED)168 suggest that up to

recommendations in the European guidelines137 include a QRS duration two-thirds of CRT-eligible patients are not receiving CRT166. The multi-

of 130–149 ms in sinus rhythm or ≥130 ms in atrial fibrillation with a national ESC CRT survey II noted that referral from non-implanting cen-

strategy in place to ensure biventricular pacing. tres accounted for only 25% of CRT referrals, suggesting that patients

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

Table 2 | Clinical trials of implantable cardioverter–defibrillators in men and women with HF

Trial (year) Device Patient cohort Number of Mean Follow-up Primary Main results Interaction by sex or end

therapy patients age (months) end point point data

(% women) (years)

MUSTT EPS-guided LVEF ≤40%, CAD, 704 (10) 67 39 Cardiac EPS-guided therapy with ICD Primary end point in

(1999)117,124 antiarrhythmic NSVT and inducible arrest or reduced cardiac arrest or death comparator groups did not

therapy sustained VT at EPS death from from arrhythmia compared differ by sex; the interaction

(AAD or ICD arrhythmia with EPS-guided therapy between treatment and

if failed AAD) without defibrillator (HR 0.24, sex was not significant for

versus no 95% CI 0.13–0.45; P < 0.001) the secondary end point of

antiarrhythmic and compared with no all-cause death (P = 0.12)

therapy antiarrhythmic therapy (HR 0.27,

95% CI 0.15–0.47; P < 0.001)

EPS-guided therapy with

ICD reduced all-cause death

compared with EPS-guided

therapy without defibrillator

(HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.27–0.59;

P < 0.001) and compared with no

antiarrhythmic therapy (HR 0.45,

95% CI 0.32–0.63; P < 0.001)

MADIT II ICD or medical LVEF ≤30%, 1,232 (16) 64 20 All-cause Compared with medical No significant interaction by

(2002)118 therapy ischaemic death therapy, ICD reduced the sex for primary end point

cardiomyopathy, rate of the primary end point

previous MI (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51–0.93;

P = 0.016)

SCD-HeFT Placebo or LVEF ≤35%, 2,521 (23) 52 45.5 All-cause Compared with placebo, ICD P for interaction by sex for

(2005)121,125 amiodarone or ischaemic or death reduced the primary end point primary end point 0.54; ICD

ICD (on top of non-ischaemic (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62–0.96; versus placebo adjusted HR

conventional cardiomyopathy, P = 0.007) 0.71 (95% CI 0.57–0.88) in men

therapy) NYHA class II–III and 0.90 (95% CI 0.56–1.43)

in women; lower mortality in

women than in men; the

differences in mortality were

most accentuated in the

placebo group

DINAMIT ICD or medical LVEF ≤35%, recent 674 (24) 62 30 All-cause Similar rates of the primary end P for interaction by sex for

(2004)120 therapy MI (6–40 days), death point in the ICD and medical primary end point 0.82

heart rate ≥80 bpm, therapy groups (HR 1.08, 95%

SDNN ≤70 ms CI 0.76–1.55; P = 0.66)

IRIS ICD or medical LVEF ≤40%, recent 898 (23) 63 37 All-cause Similar rates of the primary end P for interaction by sex for

(2009)122 therapy MI (5–31 days), death point in the ICD and medical primary end point 0.85

heart rate ≥90 bpm, therapy groups (HR 1.04, 95%

with or without CI 0.81–1.35; P = 0.78)

Holter monitoring

with NSVT

≥150 bpm

DEFINITE ICD or medical LVEF ≤35%, 458 (29) 58 29 All-cause Similar rates of the primary end P for interaction by sex

(2004)119,126 therapy non-ischaemic death point in the ICD and medical (univariate) 0.11; primary

cardiomyopathy, therapy groups (HR 0.65, 95% end point HR 0.49 (95% CI

NYHA class I–III, CI 0.40–1.06; P = 0.08) 0.27–0.90; P = 0.018) in men

Holter monitoring and 1.14 (95% CI 0.50–2.64;

NSVT ≥120 bpm or P = 0.75) in women; sex

≥10 PVC/h was not an independent

predictor of primary end

point in multivariable

analysis adjusting for NYHA

class, LVEF, age and race

(P = 0.18)

DANISH ICD or no ICD LVEF ≤35%, 1,116 (27.5) 63 67.6 All-cause Similar rates of the primary P for interaction by sex 0.66;

(2016)123 non-ischaemic death end point in the ICD and primary end point HR 0.85

cardiomyopathy, non-ICD groups (HR 0.87, 95% (95% CI 0.64–1.12; P = 0.24)

NYHA class II–IV CI 0.68–1.22; P = 0.28); there in men and 1.03 (95% CI

was high background cardiac 0.57–1.87; P = 0.92) in women

resynchronization therapy (58%)

AAD, antiarrhythmic drug; CAD, coronary artery disease; EPS, electrophysiology studies; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter–defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction;

MI, myocardial infarction; NSVT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PVC, premature ventricular complexes; SDNN, standard deviation of normal-to-

normal RR intervals (a measure of heart rate variability); VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

Table 3 | Clinical trials of cardiac resynchronization therapy in men and women with HF

Trial (year) Device Patient cohort Number Mean Follow- Primary end Main results Interaction by sex or

therapy of patients age up point end point data

(% women) (years)

MIRACLE CRT-P LVEF ≤35%, ischaemic 453 (32) 64 6 months 6MWD, QoL, Compared with no pacing, CRT Interaction with CRT

(2002)138 randomized or non-ischaemic NYHA class improved 6MWD (P = 0.005), by sex not reported in

to CRT cardiomyopathy, QoL (P = 0.001) and NYHA main manuscript

on or no NYHA class III–IV, class (P < 0.001) and reduced

pacing QRS ≥130 ms, LVEDD hospitalizations for worsening

≥55 mm, 6MWD HF (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.28–0.88;

≤450 m P = 0.02)

COMPANION CRT-P, LVEF ≤35%, ischaemic 1,520 (33) 67 11.9–16.2 All-cause Reduced 12-month rate of the Interaction with CRT

(2004)139 CRT-D or or non-ischaemic months death or primary end point with CRT-P by sex not reported in

OMT cardiomyopathy, all-cause (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.69–0.96; main manuscript

NYHA class III–IV, hospitalization P = 0.014) or CRT-D (HR 0.80,

QRS ≥120 ms, sinus 95% CI 0.68–0.95; P = 0.010)

rhythm, PR ≥150 ms compared with OMT

CARE-HF CRT-P or LVEF ≤35%, ischaemic 813 (27) 66 29 months All-cause CRT-P reduced the rate of the Primary end point HR

(2005)140 OMT or non-ischaemic death or primary end point compared 0.62 (95% CI 0.49–0.79)

cardiomyopathy, hospitalization with OMT (HR 0.63, 95% CI in men and 0.64 (95%

NYHA class III–IV; for cardio 0.51–0.77; P < 0.001) CI 0.42–0.07) in women

QRS ≥120 ms, LVEDDi vascular

≥30 mm causes

REVERSE CRT (± ICD) LVEF ≤40%, 610 (21) 63 12 months HF clinical CRT-on did not significantly Primary end point OR

(2008)143 randomized ischaemic or composite reduce the rate of the primary 0.69 (95% CI 0.43–1.11)

to CRT on non-ischaemic response end point compared with in men and 0.75 (95% CI

or off cardiomyopathy, CRT-off (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.26–2.19) in women

NYHA class I–II, QRS 0.45–1.07; P = 0.10); CRT-on

≥120 ms, LVEDD reduced LVESVI (P < 0.0001) and

>55 mm time to first HF hospitalization

(HR 0.47; P = 0.03) compared

with CRT-off

MADIT-CRT CRT-D or LVEF ≤30%, ischaemic 1,820 (25) 65 2.4 years All-cause CRT-D reduced the rate of the P for interaction by

(2009)141 ICD cardiomyopathy death or primary end point compared sex 0.01; primary end

(NYHA class I–II) non-fatal with ICD-only (HR 0.66, 95% CI point HR 0.76 (95% CI

or non-ischaemic HF event 0.52–0.84; P = 0.001) 0.59–0.97) in men and

cardiomyopathy 0.37 (95% CI 0.22–0.61)

(NYHA class II), QRS in women

≥130 ms, sinus rhythm

RAFT CRT-D or LVEF ≤30%, ischaemic 1,798 (17) 66 40 months All-cause CRT-D reduced the rate of the P for interaction by sex

(2010)142 ICD or non-ischaemic death or HF primary end point compared 0.09

cardiomyopathy, hospitalization with ICD-only (HR 0.75, 95% CI

NYHA class II–III, 0.64–0.87; P < 0.001)

intrinsic QRS ≥120 ms

(or paced QRS

≥200 ms)

Pooled CRT-P or MIRACLE, MIRACLE 3,782 (22) 66 See All-cause Compared with no CRT (OMT, All-cause death HR 0.68

analysis CRT-D ICD, CARE-HF, individual death; ICD, back-up pacing), CRT (95% CI 0.57–0.80) in

(2013)246 versus OMT REVERSE, RAFT; trials all-cause (CRT-P or CRT-D) reduced men and 0.58 (95% CI

or ICD or see individual death or HF all-cause death (HR 0.66, 0.41–0.84) in women;

back-up trials; excluded hospitalization 95% CI 0.57–0.77) and the all-cause death or HF

pacing NYHA class I, atrial composite of all-cause death hospitalization HR 0.69

fibrillation, existing or HF hospitalization (HR 0.65, (95% CI 0.60–0.79) in

pacemaker 95% CI 0.58–0.74) men and 0.50 (95% CI

0.37–0.66) in women

Pooled CRT-D or REVERSE, MADIT-CRT, 4,076 (22) 65 See Death or HF; With LBBB and QRS ≥150 ms, CRT-D reduced clinical

analysis ICD RAFT individual death end points compared with ICD-alone in women (death

(2014)153 trials or HF, HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.21–0.52; death, HR 0.36,

95% CI 0.16–0.82) and men (death or HF, HR 0.47, 95% CI

0.37–0.59; death, HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47–0.91)

With LBBB and QRS 130–149 ms, CRT-D reduced clinical

end points compared with ICD-alone in women (death

or HF, HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.11–0.53; death, HR 0.24, 95% CI

0.06–0.89), but not in men (death or HF, HR 0.85, 95% CI

0.60–1.21; death, HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.49–1.52)

6MWD, 6-min walking distance; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CRT-D, CRT plus defibrillator; CRT-P, CRT plus pacemaker; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter–defibrillator;

LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEDDi, LVEDD indexed for height; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVI, left ventricular

end-systolic volume index; NYHA, New York Heart Association; QoL, quality of life; OMT, optimal medical therapy.

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

outside university or teaching hospital settings have more limited Interventions for mitral valve regurgitation. Sex-related differences

access to CRT169. In an analysis of a HF registry from Sweden, female in outcomes exist after mitral valve intervention for mitral regurgita-

sex and advanced age were independent predictors of non-referral tion in patients with HF (Table 4). In a secondary analysis of sex-based

for CRT161. Strategies to improve implementation of CRT are needed, differences177 from the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network SIMR

especially in eligible women in light of the evidence showing that they trial178,179, women had a smaller left ventricular volume and a smaller

derive greater benefit than men. Such strategies include overcoming mitral valve effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) but proportionally

barriers in referral166,170, which includes increasing awareness of the larger EROA-to-left ventricular end-diastolic volume ratio than men177. At

indications and benefits of CRT among clinicians169, leveraging elec- 2 years after mitral valve surgery, although the degree of reverse left ven-

tronic health records for identification of eligible patients, and engag- tricular remodelling was similar in both sexes, women had higher rates

ing patients and support organizations to address misconceptions, of all-cause death and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular

promote information dissemination and increase therapeutic uptake166. events and worse QoL and functional status than men177.

Together with advances in pharmacological therapies for HF, A sex-specific analysis of the COAPT trial assessed the influence of sex

new approaches to pacing and resynchronization are also emerging. on the response to device therapy in patients with HF and severe secondary

In particular, conduction system pacing171–174 (targeting the His bun- mitral regurgitation. Although transcatheter mitral valve repair with the

dle or the left bundle branch area) as a form of cardiac physiological MitraClip resulted in improved clinical outcomes compared with GDMT

pacing175 is emerging as an alternative to conventional resynchroni- alone for both sexes, the relative reduction in HF hospitalizations was less

zation (with placement of a coronary sinus lead to pre-excite the left pronounced in women (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.57–1.05) than in men (HR 0.43,

ventricle). The RCT funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research 95% CI 0.34–0.54; P for interaction 0.002), especially beyond the first year

Insitute176 will evaluate the comparative effectiveness of His bundle of treatment. Women also derived less benefit from transcatheter mitral

or left bundle branch pacing in patients with a LVEF ≤50% and with valve repair than men with regard to QoL scores and 6MWD180.

either a wide QRS (≥130 ms), or with an anticipated pacing of >40% who

are already receiving current standard HF pharmacological therapy. Mechanical circulatory support. With respect to left ventricular

Sex-specific data in conduction system pacing will be needed to guide assist device (LVAD) therapy, female sex was independently associated

further consideration. with higher inpatient mortality after implantation in those implanted

Table 4 | Select clinical trials of mitral valve interventions and neuromodulation in men and women with HF

Trial (year) Device Patient cohort Number Mean Follow-up Primary end Main results Interaction by sex or end point data

therapy of patients age (months) point

(% women) (years)

Mitral valve interventions

COAPT TMVR LVEF 20–50%, 614 (36) 72 24 HF TMVR reduced the P for interaction by sex 0.05; primary

(2018)180,247 plus ischaemic or hospitalization primary end point of end point HR 0.44 (95% CI 0.32–0.61)

GDMT or non-ischaemic HF hospitalization in men and 0.77 (95% CI 0.49–1.21) in

GDMT cardiomyopathy, (HR 0.53, 95% CI women

alone moderate-to- 0.40–0.70; P < 0.001)

severe or severe as well as all-cause

secondary mitral death (HR 0.62, 95% CI

regurgitation, 0.46–0.82; P < 0.001)

NYHA class II–IV

Autonomic nervous system modulation

BeAT-HF BAT plus LVEF ≤35%, 264 (20) 62 6 6MWD, QoL, BAT improved No significant interaction by sex for

(2020)187,248 GDMT NYHA class II–III NT-proBNP 6MWD (P < 0.001), 6MWD, QoL and NYHA; BAT showed

or GDMT QoL (P < 0.001) and benefits in women and men; significant

alone NT-proBNP (P < 0.001) interaction by sex for NT-proBNP (P for

at 6 months of interaction 0.05), significant reduction

follow-up in plasma NT-proBNP levels with BAT in

women (P < 0.01) but less pronounced

and not significant in men (P = 0.08)

INOVATE-HF VNS plus LVEF ≤40%, NYHA 707 (21) 61 16 All-cause Similar rates of the P for interaction by sex 0.03; primary

(2016)188 GDMT or class III, mortality or HF primary end point in end point HR 0.99 (P = 0.93) in men

GDMT LVEDD 50–80 mm event the VNS and control and 2.43 (P = 0.02) in women; sex was

groups (HR 1.14, 95% no longer an independent predictor

CI 0.86–1.53; P = 0.37); of outcome (P = 0.17) in multivariate

compared with analysis incorporating sex-based

control, VNS improved differences (women were younger, with

6MWD (P < 0.01), QoL smaller left ventricular volume, shorter

(P < 0.01) and NYHA QRS duration and more likely to have

class (P < 0.01) non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy)

6MWD, 6-min walking distance; BAT, baroreflex activation therapy; GDMT, guideline-directed medical therapy; HF, heart failure; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEF, left

ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, amino‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; QoL, quality of life; TMVR, transcatheter mitral valve repair;

VNS, vagal nerve stimulation.

Nature Reviews Cardiology

Review article

during the pulsatile-flow LVAD era, but not in those implanted during new CIED in Australia and New Zealand reported more 90-day major