Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Acute Mediastinitis

Acute Mediastinitis

Uploaded by

Maria Saragoca0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesMediastinitis is an infection of the structures in the

thorax excluding the lungs and pleural space. Most

cases of mediastinitis are secondary to spread of infec

tion from a distant site or direct inoculation of organ

isms secondary to trauma or esophageal perforation

due to malignancy.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMediastinitis is an infection of the structures in the

thorax excluding the lungs and pleural space. Most

cases of mediastinitis are secondary to spread of infec

tion from a distant site or direct inoculation of organ

isms secondary to trauma or esophageal perforation

due to malignancy.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views2 pagesAcute Mediastinitis

Acute Mediastinitis

Uploaded by

Maria SaragocaMediastinitis is an infection of the structures in the

thorax excluding the lungs and pleural space. Most

cases of mediastinitis are secondary to spread of infec

tion from a distant site or direct inoculation of organ

isms secondary to trauma or esophageal perforation

due to malignancy.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 2

Chapter 51

51 Acute Mediastinitis

K.P. Bhavan, D.K. Warren

51.1 ly. The surgical management of these infections has

Introduction evolved from initial debridement with closure by sec-

ondary intention, to primary closure with closed irri-

Mediastinitis is an infection of the structures in the gation, to the use of omental and muscle flaps.

thorax excluding the lungs and pleural space. Most The advent of antibiotics did little alone to change

cases of mediastinitis are secondary to spread of infec- the outcome of mediastinitis. In 1983, Estera et al. [3]

tion from a distant site or direct inoculation of organ- reviewed 21 cases of descending necrotizing mediasti-

isms secondary to trauma or esophageal perforation nitis from 1960 to 1980 and reported a mortality of

due to malignancy. The last 30 years have seen a dra- 42.8 %, with the majority of these cases being diag-

matic increase in the annual number of cardiac surgical nosed at autopsy. This high mortality rate was attribut-

procedures performed. Consequently, post-sternotomy ed to the frequent lack of physical and radiographic

surgical site infections have accounted for an increas- findings early in the course of the disease. The develop-

ing number of cases of mediastinitis. Despite signifi- ment of computerized tomography (CT) has increased

cant advances in antibiotic therapy, surgical technique, the capacity for earlier diagnosis and improved pre-op-

and intensive care management, mediastinitis contin- erative planning of surgical management. An analysis

ues to have a high morbidity and mortality. This chap- of 48 cases of mediastinitis from 1990 to 1998 revealed

ter will focus on three major categories of mediastini- that the mortality for descending infections had im-

tis, including descending necrotizing infections, medi- proved to 23 % [4], which the authors attributed to the

astinitis secondary to esophageal perforations, and availability of CT.

post-sternotomy surgical site infections, and will dis-

cuss the pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and

51.1.2

management associated with each. The anatomy of the

Anatomy of the Neck and Mediastinum

neck and mediastinum, which is crucial to understand-

ing the pathogenesis and complications of mediastini- Understanding the pathogenesis, complications, and

tis, as well as unusual causes of mediastinitis will also successful management of mediastinal infections re-

be reviewed. quires knowledge of the anatomical relationships be-

tween the organs and vascular structures of the neck

and mediastinum. The mediastinum contains the

51.1.1

heart, great vessels, trachea, esophagus, paratracheal

Historical Overview

lymph nodes, and the thymus. This is bordered ana-

The first major review of suppurative mediastinitis was tomically by the thoracic inlet superiorly, the dia-

by Pearse [1] in 1938 involving 110 cases. In this series, phragm inferiorly, the sternum anteriorly, the vertebral

58 % of cases were due to esophageal perforation and bodies posteriorly, and the pleural cavities laterally.

the remainder were secondary to descending infections The fascial planes of the head and neck are of great im-

of the head and neck, along with post-surgical compli- portance in understanding the spread of infection in

cations. Mortality in the pre-antibiotic era without sur- the chest. The most important of these fascial planes

gical drainage was 85 %; with surgery mortality de- are the retropharyngeal, visceral, prevertebral, lateral

creased to 35 %. pharyngeal, and previsceral spaces which communi-

With the increasing use of the median sternotomy cate directly with the mediastinum, and determine the

incision, a new cause of mediastinitis rapidly became mechanism by which perforations in the cervical

apparent. Overall, the infection rate for median sterno- esophagus and infections of the oropharynx can spread

tomy is low, but given the volume of patients who un- to the thorax.

dergo this procedure for cardiac surgery each year, The clinically important areas in the neck are divid-

even a low rate translates into a potentially large num- ed into three sections determined by their relationship

ber of patients with post-operative mediastinal infec- to the hyoid bone (Fig. 51.1). The retropharyngeal and

tions. In a 1976 review by Culliford [2], mortality the visceral spaces extend both above and below the hy-

ranged from 7 % in the group that was recognized early oid bone. The retropharyngeal space, or retrovisceral

to 20 % among patients diagnosed late post-operative- space, is limited anteriorly by the middle layer of the

51.2 Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis 543

infection. The lateral pharyngeal space communicates

with many of the spaces in the neck and is associated

with infections of the pharynx, teeth, tonsils, or paro-

tids. The parotid space communicates directly with the

“danger space” and the lateral pharyngeal space.

Therefore, infections in the parotids can rapidly extend

throughout the mediastinum.

Below the hyoid bone is the anterior visceral or pre-

visceral space. This extends from the hyoid bone supe-

riorly to the anterior mediastinum inferiorly. It is bor-

dered by the strap muscles anteriorly, and surrounds

the trachea, with the esophagus forming its posterior

border. The pretracheal investing fascia is attached to

the pericardium and the parietal pleura, which can re-

sult in pericarditis and empyema from infection in this

space. The most common causes of infection in this

space include tracheal or esophageal disruption. Final-

ly, the course of the esophagus is important to review,

as esophageal perforation is a significant cause of me-

diastinitis and the complications of this can be predict-

Fig. 51.1. The deep fascial layers of the neck and their relation-

ed partially from the site of the perforation. The upper

ship to the mediastinum two-thirds of the thoracic esophagus lies in close prox-

imity to the right pleural space, while the distal third

deviates to the left to enter the diaphragmatic hiatus.

deep cervical fascia and the deepest layer of the deep Perforations of the lower thoracic esophagus are more

cervical fascia, or the alar fascia posteriorly. This space likely to cause left-sided empyemas and possible retro-

exists behind the hypopharynx and esophagus from peritoneal extension.

the base of the skull to the superior mediastinum. Ret-

ropharyngeal infections in this space can descend easi-

51.1.3

ly into the superior mediastinum. This was recognized

Pathogenesis

early to be the space most likely involved in cervical

esophageal perforations [1, 5]. This space is often in- The causes of mediastinitis are multiple (Table 51.1).

volved in extension of infections of the cervical verte- However, cases can be divided by source, which ex-

bra. Just posterior to the retropharyngeal space, be- plains the microbiology of the infection and also in part

tween the alar fascia and the prevertebral fascia, is an determines treatment strategies. Head and neck infec-

area called by some authors the “danger space” [5], tions, esophageal perforations, and post-sternotomy

which extends from the base of the skull to the crus of infections are the primary causes of mediastinitis. Oth-

the diaphragm and is a source of potential dissemina- er more unusual causes of mediastinal infection will al-

tion of retropharyngeal or lateropharyngeal infection so be addressed.

to the base of the posterior mediastinum and the retro-

peritoneal space [3, 5].

The visceral space is located within the carotid 51.2

sheath and includes all three layers of the deep cervical Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis

fascia. Infections in this space less commonly extend

down to the mediastinum, but given their location in Descending necrotizing mediastinitis is an unusual in-

relationship to the great vessels, can cause internal jug- fection arising from the structures of the mouth, neck,

ular vein septic thrombophlebitis and carotid artery and pharynx. This begins as a localized infection,

rupture. Classically, suppurative lymphadenitis, peri- which then descends inferiorly via the fascial planes of

tonsillar abscess, and Ludwig’s angina were causes of the neck into the thorax. Several factors facilitate the

infections in this space; however, any of the structures spread of these infections to the mediastinal structures,

of the pharynx and neck can serve as a source. including gravitational drainage, negative intrathorac-

Above the hyoid bone are the submandibular space, ic pressure with inspiration, and the lack of significant

the lateral pharyngeal space, the masticator space, and barriers in the retropharyngeal space. The fascial

the parotid space. The submandibular and masticator planes of the neck can be penetrated by these infec-

spaces are most involved with dental infections, with tions, and subsequently involve all compartments of

Ludwig’s angina being a result of submandibular space the neck and mediastinum. Often, patients can rapidly

You might also like

- 100 MCQs AND ANSWERS PAPER 1Document26 pages100 MCQs AND ANSWERS PAPER 1Fan Eli100% (10)

- CEDERA TRAKEOBRONKIAL NoviDocument18 pagesCEDERA TRAKEOBRONKIAL NoviRizka Desti AyuniNo ratings yet

- Medicine Colloquium Exam - 2014 ADocument40 pagesMedicine Colloquium Exam - 2014 ArachaNo ratings yet

- General Surgery: Dr. S. Gallinge R Gord On Bud Uhan and Sam Minor, e D Itors Dana M Kay, Associate e D ItorDocument56 pagesGeneral Surgery: Dr. S. Gallinge R Gord On Bud Uhan and Sam Minor, e D Itors Dana M Kay, Associate e D ItorKamran AfzalNo ratings yet

- Deep Neck Spaces: Skull BaseDocument17 pagesDeep Neck Spaces: Skull BaseRaja Ahmad Rusdan MusyawirNo ratings yet

- Journal EmpyemaDocument6 pagesJournal EmpyemaElisaNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Patients With Mediastinal MassesDocument10 pagesAnesthesia For Patients With Mediastinal MassesFityan Aulia RahmanNo ratings yet

- Ent PPT On Pharyngeal AbscessDocument20 pagesEnt PPT On Pharyngeal AbscessDocwocNo ratings yet

- Angina de Ludwig AnestesiaDocument8 pagesAngina de Ludwig AnestesiaDEMETRIO MAYORAL PARDONo ratings yet

- Management of Parapharyngeal and Retropharingeal Space InfectionsDocument29 pagesManagement of Parapharyngeal and Retropharingeal Space InfectionsAndrés Faúndez TeránNo ratings yet

- Descending Mediastinitis: A ReviewDocument6 pagesDescending Mediastinitis: A ReviewMohammed Al MutawakelNo ratings yet

- 21 BartolekDocument6 pages21 BartolekMuhammad ZuhriNo ratings yet

- Airways in Mediastinal Mass PDFDocument9 pagesAirways in Mediastinal Mass PDFHarish BhatNo ratings yet

- EmpyemaDocument12 pagesEmpyemavictoriaNo ratings yet

- Author Anthony W Chow, MD, FRCPC, FACP Section Editor Stephen B Calderwood, MD Deputy Editor Allyson Bloom, MDDocument16 pagesAuthor Anthony W Chow, MD, FRCPC, FACP Section Editor Stephen B Calderwood, MD Deputy Editor Allyson Bloom, MDSiska HarapanNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis, The Complication of Odontogenic AbcessDocument3 pagesPathogenesis of Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis, The Complication of Odontogenic AbcessAzis BoenjaminNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of Fascial SpacesDocument68 pagesAnatomy of Fascial SpacesVaibhav Nagaraj100% (1)

- Deep Neck Space InfectionsDocument43 pagesDeep Neck Space InfectionsmariscaclaudiaaNo ratings yet

- Space InfectionsDocument60 pagesSpace InfectionsDan 04No ratings yet

- CH 55 Deep Neck Infections (Bailey's)Document2 pagesCH 55 Deep Neck Infections (Bailey's)Junior VillNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic and DniDocument9 pagesOdontogenic and DniA. DuqueNo ratings yet

- Abses SubmandibularDocument17 pagesAbses Submandibularhoney_hannieNo ratings yet

- CT of The Paranasal Sinuses: Study of A Control Series in Relation To Endoscopic Sinus SurgeryDocument5 pagesCT of The Paranasal Sinuses: Study of A Control Series in Relation To Endoscopic Sinus SurgeryErsa Aqilla HayaNo ratings yet

- 10 1097@SCS 0b013e31821d4dc9Document41 pages10 1097@SCS 0b013e31821d4dc9Sagar LodhiaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Parapharyngeal Space InfectionsDocument16 pagesSurgical Management of Parapharyngeal Space InfectionsAndrés Faúndez TeránNo ratings yet

- Deep Neck Infections: ProblemDocument14 pagesDeep Neck Infections: ProblemAmy KochNo ratings yet

- Case RP 1 Pleomorphic AdenomaDocument5 pagesCase RP 1 Pleomorphic AdenomaSathvika BNo ratings yet

- Chest TraumaDocument9 pagesChest TraumaPurple Ivy GuarraNo ratings yet

- Fascial Space InfectionDocument19 pagesFascial Space Infectiondion leonardoNo ratings yet

- JMedLife 07 343 PDFDocument6 pagesJMedLife 07 343 PDFAzmi FananyNo ratings yet

- A 15-Month-Old Boy With Respiratory Distress and Parapharyngeal Abscess: A Case ReportDocument5 pagesA 15-Month-Old Boy With Respiratory Distress and Parapharyngeal Abscess: A Case ReportAriPratiwiNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Deep Neck Space Fascial Infections Fot The Dental TeamDocument5 pagesA Guide To Deep Neck Space Fascial Infections Fot The Dental TeamAndrés Faúndez TeránNo ratings yet

- Whiteford2007 Abses PerianalDocument8 pagesWhiteford2007 Abses PerianalPudyo KriswhardaniNo ratings yet

- 5960 Bahar PDFDocument2 pages5960 Bahar PDFYazid Eriansyah PradantaNo ratings yet

- Deep Neck Infection: Analysis of 185 Cases: Correspondence To: Y.-S. Chen B 2004 Wiley Periodicals, IncDocument7 pagesDeep Neck Infection: Analysis of 185 Cases: Correspondence To: Y.-S. Chen B 2004 Wiley Periodicals, IncHiramNo ratings yet

- DP Paraneu BTS10Document14 pagesDP Paraneu BTS10Yu-Ya LinNo ratings yet

- Around The Posterior Margin of The Mylohyoid MuscleDocument8 pagesAround The Posterior Margin of The Mylohyoid MuscleTyo RizkyNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Pneumothorax in Critically Ill Adults: James J Rankine, Antony N Thomas, Dorothee FluechterDocument6 pagesDiagnosis of Pneumothorax in Critically Ill Adults: James J Rankine, Antony N Thomas, Dorothee FluechternovywardanaNo ratings yet

- Neumona HarrisonDocument14 pagesNeumona HarrisonZafiss ChaconNo ratings yet

- World's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherDocument21 pagesWorld's Largest Science, Technology & Medicine Open Access Book PublisherStefana NanuNo ratings yet

- 3.11. Sublingual SpaceDocument1 page3.11. Sublingual SpaceTitis Mustika HandayaniNo ratings yet

- RETROPERITONEALDocument3 pagesRETROPERITONEALmichelleNo ratings yet

- Absesparafaring4 PDFDocument3 pagesAbsesparafaring4 PDFnataliayobeantoNo ratings yet

- Managing Mediastinitis After Cardiac SurgeryDocument4 pagesManaging Mediastinitis After Cardiac SurgeryDennis CobbNo ratings yet

- Anatomie Considerations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Odontogenic InfectionsDocument9 pagesAnatomie Considerations in Diagnosis and Treatment of Odontogenic InfectionsDSS.JORGE ALBERTO PÉREZ HERNÁNDEZNo ratings yet

- Fournier Gangrene - Practice Essentials, Background, AnatomyDocument9 pagesFournier Gangrene - Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomyflavia_craNo ratings yet

- Siddiqui 2013Document27 pagesSiddiqui 2013ahmedNo ratings yet

- Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses: Fig. 3.1 The Anatomic Location of The Paranasal SinusesDocument35 pagesNasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses: Fig. 3.1 The Anatomic Location of The Paranasal SinuseswillyoueverlovemenkNo ratings yet

- Thomas K, Gupta M, Gaba S, Gupta M. Tubercular Retropharyngeal Abscess With Pott's Disease in An Elderly Male Patient. Cureus. 2020 12 (5) .Document6 pagesThomas K, Gupta M, Gaba S, Gupta M. Tubercular Retropharyngeal Abscess With Pott's Disease in An Elderly Male Patient. Cureus. 2020 12 (5) .Imam Taqwa DrughiNo ratings yet

- Multiple Space Infection and Current Treatment StrategiesDocument30 pagesMultiple Space Infection and Current Treatment StrategiesSibaniNo ratings yet

- Review of Internal HerniasDocument15 pagesReview of Internal HerniassavingtaviaNo ratings yet

- Hyatt 2017Document11 pagesHyatt 2017Kevin TandartoNo ratings yet

- Current Problems in Diagnostic RadiologyDocument11 pagesCurrent Problems in Diagnostic Radiologyviena mutmainnahNo ratings yet

- Referat PeritonitisDocument19 pagesReferat PeritonitisAdrian Prasetya SudjonoNo ratings yet

- Carcinoma of NasopharynxDocument15 pagesCarcinoma of NasopharynxAmeliana KamaludinNo ratings yet

- 2017 Blot MmiDocument10 pages2017 Blot MmiAnonymous fdCVcfEQurNo ratings yet

- 8 PDFDocument8 pages8 PDFAnonymous V4TNCnDbNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Infection Dentist6Document39 pagesOdontogenic Infection Dentist6Kimya Zand100% (1)

- Reynolds 2007Document20 pagesReynolds 2007Melvri BisaiNo ratings yet

- Peritonsillar Abscess: Complication of Acute Tonsillitis or Weber's Glands Infection?Document9 pagesPeritonsillar Abscess: Complication of Acute Tonsillitis or Weber's Glands Infection?holly theressaNo ratings yet

- Airway TraumaDocument20 pagesAirway TraumaJohan Lanzziano SilvaNo ratings yet

- نم انوسنت لا مكوجرأ ,يلهلا و يل ةيراج ةقدص مكئاعد حلا ص Please Grace us with your good prayersDocument538 pagesنم انوسنت لا مكوجرأ ,يلهلا و يل ةيراج ةقدص مكئاعد حلا ص Please Grace us with your good prayersSahan EpitawalaNo ratings yet

- Mediastinitis - IDDocument52 pagesMediastinitis - IDDidy Kurniawan100% (1)

- BoerhaaveDocument3 pagesBoerhaaveMartu EilertNo ratings yet

- DISORDERS of The MEDIASTINUMDocument37 pagesDISORDERS of The MEDIASTINUMKezia ImanuellaNo ratings yet

- A Management Algorithm For Esophageal PerforationDocument4 pagesA Management Algorithm For Esophageal Perforationoscar chirinosNo ratings yet

- Purulent Diseases of Lungs and PleuraDocument60 pagesPurulent Diseases of Lungs and PleuraBob BlythNo ratings yet

- Esophagus QuesDocument8 pagesEsophagus QuesnehaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Unusual Esophageal Foreign Body in Neonates: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery Case Reports: Unusual Esophageal Foreign Body in Neonates: A Case ReportmusdalifahNo ratings yet

- Esophagus HUDocument84 pagesEsophagus HURaneen SamraNo ratings yet

- Esophagus: DrzaiterDocument37 pagesEsophagus: DrzaiterdrynwhylNo ratings yet

- Esophageal PerforationDocument1 pageEsophageal PerforationSteven GodelmanNo ratings yet

- EsophagusDocument41 pagesEsophagusrayNo ratings yet

- Blunt Thoracic Trauma - Role of Chest Radiography and Comparison With CT - Fndings and Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesBlunt Thoracic Trauma - Role of Chest Radiography and Comparison With CT - Fndings and Literature Revieworalposter PIPKRA2023No ratings yet

- Dolor ToracicoDocument11 pagesDolor ToracicoSandy A.No ratings yet

- Anaes FCPS 2 Mar 2023 Recalled Paper (Edited With Keys) LatestDocument29 pagesAnaes FCPS 2 Mar 2023 Recalled Paper (Edited With Keys) LatestDr IqraNo ratings yet

- Stomach-Esophagus MedCosmos Surgery - MCQDocument39 pagesStomach-Esophagus MedCosmos Surgery - MCQMike G100% (1)

- Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) : Practice EssentialsDocument52 pagesUpper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB) : Practice EssentialsrishaNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia SurgicalDocument75 pagesDysphagia Surgicalian ismail100% (1)

- C 1+ 2 Surgicl Pathology of OesophagusDocument91 pagesC 1+ 2 Surgicl Pathology of OesophagusSayuridark5No ratings yet

- PeritonitisDocument33 pagesPeritonitisnurulamaliahnutNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S187878861000086X MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S187878861000086X MainAngeel GomezNo ratings yet

- Short Notes: Melaka Trauma Life SupportDocument104 pagesShort Notes: Melaka Trauma Life SupportSebastian KohNo ratings yet

- Esophageal Perforation TreatmentDocument4 pagesEsophageal Perforation TreatmentDabessa MosissaNo ratings yet

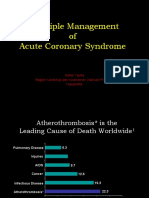

- Principle Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Nahar Taufiq Bagian Kardiologi Dan Kedokteran Vaskuler FK UGM YogyakartaDocument57 pagesPrinciple Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome: Nahar Taufiq Bagian Kardiologi Dan Kedokteran Vaskuler FK UGM YogyakartaIntan Farida YasminNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care For A Client With Chest Trauma: Reported By: Jazon, Gabriel Liberon PDocument100 pagesNursing Care For A Client With Chest Trauma: Reported By: Jazon, Gabriel Liberon PGabriel Liberon P. JazonNo ratings yet

- Chest Radio 8 Widening of The MediastinumDocument14 pagesChest Radio 8 Widening of The Mediastinumlonsilord17No ratings yet

- Arab Board Exam 2 With AnswersDocument31 pagesArab Board Exam 2 With Answersahmed.farag.ali2020No ratings yet