Professional Documents

Culture Documents

VITHAYATHIL SpacesDiscriminationResidential 2012

VITHAYATHIL SpacesDiscriminationResidential 2012

Uploaded by

anshulpatel0608Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Claudia Goldin-Career and FamilyDocument1 pageClaudia Goldin-Career and Familyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Bigger Than This - Fabian Geyrhalter - 1Document8 pagesBigger Than This - Fabian Geyrhalter - 1abas004No ratings yet

- The Music in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space OdysseyDocument27 pagesThe Music in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space OdysseyJoris Daniel100% (1)

- Discriminated Urban SpacesDocument10 pagesDiscriminated Urban SpacesKapil Kumar GavskerNo ratings yet

- SA LIII 50 221218 Sriti GangulyDocument8 pagesSA LIII 50 221218 Sriti GangulyVikash KumarNo ratings yet

- Diasporas Transforming HomelandsDocument9 pagesDiasporas Transforming HomelandsVijay SinghNo ratings yet

- Caste and The Indian Economy: Kaivan MunshiDocument55 pagesCaste and The Indian Economy: Kaivan MunshiIsak PeuNo ratings yet

- Caste in 21st CentDocument22 pagesCaste in 21st CentkittyNo ratings yet

- Indian Anthropological Association Indian AnthropologistDocument17 pagesIndian Anthropological Association Indian Anthropologistindiabhagat101No ratings yet

- Contemporary Relevance of Jajmani RelationsDocument10 pagesContemporary Relevance of Jajmani RelationsAnonymous MTTd4ccDqO0% (1)

- Lina Carranza & Diego Vargas: National Univertisty of ColombiaDocument12 pagesLina Carranza & Diego Vargas: National Univertisty of ColombiaDiego VargasNo ratings yet

- Tribes As Indigenous People of IndiaDocument8 pagesTribes As Indigenous People of IndiaJYOTI JYOTINo ratings yet

- Exclusive Inequalities Merit, Caste and Discrimination in Indian Higher EducaDocument8 pagesExclusive Inequalities Merit, Caste and Discrimination in Indian Higher EducaArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- Isolated by Caste: Neighbourhood-Scale Residential Segregation in Indian MetrosDocument22 pagesIsolated by Caste: Neighbourhood-Scale Residential Segregation in Indian MetrosadiksayyuuuuNo ratings yet

- Caste in Contemporary India - Flexibility and PersistenceDocument21 pagesCaste in Contemporary India - Flexibility and PersistenceRamanNo ratings yet

- AGGARWAL CastePowerElite 2015Document8 pagesAGGARWAL CastePowerElite 2015Abijeeth ThirumalainathanNo ratings yet

- Caste Diversity in Corporate BoardroomsDocument6 pagesCaste Diversity in Corporate BoardroomsAbijeeth ThirumalainathanNo ratings yet

- Resourcefulness of Locally-Oriented Social Enterprises - Implications For Rural Community DevelopmentDocument10 pagesResourcefulness of Locally-Oriented Social Enterprises - Implications For Rural Community DevelopmentMembaca Tanda ala Pendidik RumahanNo ratings yet

- Politics of Language, Religion and Identity - Tribes in IndiaDocument9 pagesPolitics of Language, Religion and Identity - Tribes in IndiaVibhuti KachhapNo ratings yet

- Virginia XaxaDocument8 pagesVirginia XaxaMEGHA YADAVNo ratings yet

- Gender Urban Space and The Right To Everyday LifeDocument13 pagesGender Urban Space and The Right To Everyday LifePaulo SoaresNo ratings yet

- Caste SystemDocument4 pagesCaste Systemvrindasharma300No ratings yet

- Life Satisfaction and Well-Being at The Intersections of Caste and Gender in IndiaDocument15 pagesLife Satisfaction and Well-Being at The Intersections of Caste and Gender in IndiaLovis KumarNo ratings yet

- Building Convergence of Ethnicity in The Unitary State of The Republic of Indonesia DdisDocument10 pagesBuilding Convergence of Ethnicity in The Unitary State of The Republic of Indonesia Ddis18Nyoman Ferdi Chandra P.No ratings yet

- Sense of Community in New Urbanism NeighbourhoodsDocument5 pagesSense of Community in New Urbanism NeighbourhoodsGeley EysNo ratings yet

- Singh ImportanceCasteBasedHeadcounts 2023Document18 pagesSingh ImportanceCasteBasedHeadcounts 2023rinajha8204No ratings yet

- Social Exclusion in Modern Urban Space. 2022Document12 pagesSocial Exclusion in Modern Urban Space. 2022Ananda BritoNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 10-Sep-2020Document14 pagesAdobe Scan 10-Sep-2020Cheshta DixitNo ratings yet

- SRC July 6 ObservationsDocument18 pagesSRC July 6 Observationssumeet raiNo ratings yet

- Amin, Collective CultureDocument21 pagesAmin, Collective CultureahceratiNo ratings yet

- Indian Village: Discrete and Static Image British Administrator-Scholars Baden-Powell Henry MaineDocument4 pagesIndian Village: Discrete and Static Image British Administrator-Scholars Baden-Powell Henry MaineManoj ShahNo ratings yet

- (Ge) Political Science Human Right Part-1 Eng.Document155 pages(Ge) Political Science Human Right Part-1 Eng.noxar10515No ratings yet

- Indian DemocracyDocument11 pagesIndian DemocracydoitvarunNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Tribe and Their Major Problems in India: School of Development StudiesDocument17 pagesThe Concept of Tribe and Their Major Problems in India: School of Development Studiesshruti vermaNo ratings yet

- The Mirage of A Caste-Less Society in IndiaDocument6 pagesThe Mirage of A Caste-Less Society in IndiaMohd MalikNo ratings yet

- 828 Improving The Social Sustainability of High Rises PDFDocument8 pages828 Improving The Social Sustainability of High Rises PDFAlbert TalonNo ratings yet

- CESC FinalsDocument7 pagesCESC FinalslantakadominicNo ratings yet

- Caste System Today in IndiaDocument20 pagesCaste System Today in IndiaSharon CreationsNo ratings yet

- Convergencia de Los Emprendimientos en Casa y El Espacio DomesticoDocument7 pagesConvergencia de Los Emprendimientos en Casa y El Espacio DomesticoRafael BerriosNo ratings yet

- From Caste To Class in Indian SocietyDocument15 pagesFrom Caste To Class in Indian SocietyAmitrajit BasuNo ratings yet

- Activity 1-Ucsp AgodoloDocument7 pagesActivity 1-Ucsp AgodoloCarl John AgodoloNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument10 pages1 PBmahtrian nopeNo ratings yet

- Urbanism As Way of LifeDocument20 pagesUrbanism As Way of LifeSaurabh SumanNo ratings yet

- Spatial Analysis of Social Inequality in Moradabad CityDocument7 pagesSpatial Analysis of Social Inequality in Moradabad CityResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Sociology AssignmentDocument23 pagesSociology AssignmentManushi SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Census and CasteDocument9 pagesCensus and CasteManya TrivediNo ratings yet

- Caste, Class and GenderDocument30 pagesCaste, Class and GenderVipulShukla83% (6)

- Economic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyDocument4 pagesEconomic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyNiharikaNo ratings yet

- Convolution Dwelling System As Alternative Solution in Housing Issues in Urban Area of BandungDocument15 pagesConvolution Dwelling System As Alternative Solution in Housing Issues in Urban Area of BandungHafiz AmirrolNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Imperative GramswarajDocument25 pages21st Century Imperative Gramswarajdonvoldy666No ratings yet

- Q2 - Understanding Curriculum MapDocument6 pagesQ2 - Understanding Curriculum MapWillisNo ratings yet

- Adverse Conditions For Wellbeing at The Neighbourhood Scale - 2020 - WellbeingDocument11 pagesAdverse Conditions For Wellbeing at The Neighbourhood Scale - 2020 - WellbeingBLOODY BLADENo ratings yet

- Spatial Inequality and Untouchability: Ambedkar's Gaze On Caste and Space in Hindu VillagesDocument13 pagesSpatial Inequality and Untouchability: Ambedkar's Gaze On Caste and Space in Hindu VillagesRitika SinghNo ratings yet

- Caste & Indian EconomyDocument79 pagesCaste & Indian Economysibte akbarNo ratings yet

- Year Title of Paper Author Variables Research Methods/Appr Oach InferenceDocument9 pagesYear Title of Paper Author Variables Research Methods/Appr Oach InferenceAr Apurva SharmaNo ratings yet

- Portes DiversitySocialCapital 2011Document20 pagesPortes DiversitySocialCapital 2011Bubbles Beverly Neo AsorNo ratings yet

- LocalWisdom AuliaRDocument9 pagesLocalWisdom AuliaRberkasnindaNo ratings yet

- 145793840413ETDocument12 pages145793840413ETrahulNo ratings yet

- Law and Social Transformation in IndiaDocument12 pagesLaw and Social Transformation in IndiaUtkarrsh Mishra100% (1)

- Women's Work, Welfare and Status Forces of Tradition and Change in IndiaDocument15 pagesWomen's Work, Welfare and Status Forces of Tradition and Change in IndiaAshok KumarNo ratings yet

- Urban Ethnography.Document8 pagesUrban Ethnography.SebastianesfaNo ratings yet

- Caste, Class, and Power: Changing Patterns of Stratification in a Tanjore VillageFrom EverandCaste, Class, and Power: Changing Patterns of Stratification in a Tanjore VillageNo ratings yet

- Space and Pluralism: Can Contemporary Cities Be Places of Tolerance?From EverandSpace and Pluralism: Can Contemporary Cities Be Places of Tolerance?No ratings yet

- MSMEs Introduction-Rashmi ChaudharyDocument46 pagesMSMEs Introduction-Rashmi Chaudharyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Praveen Jha-Labour Condition in Rural IndiaDocument134 pagesPraveen Jha-Labour Condition in Rural Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Display PDF - PHPDocument21 pagesDisplay PDF - PHPanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Robert Ezra IntroductionDocument2 pagesRobert Ezra Introductionanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Changing Contours of Solid Waste Management in IndiaDocument11 pagesChanging Contours of Solid Waste Management in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Archana Prasad-Integrated Farm Solutions and Its Impact On Small Farmers A Case Study of Bayer in Karnal, Haryana, GPN Working Paper NumbeDocument90 pagesArchana Prasad-Integrated Farm Solutions and Its Impact On Small Farmers A Case Study of Bayer in Karnal, Haryana, GPN Working Paper Numbeanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Agrarian Question of Capital and LabourDocument35 pagesAgrarian Question of Capital and Labouranshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Gandhi and MSMEsDocument9 pagesGandhi and MSMEsanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Law and COntradictionsDocument13 pagesLaw and COntradictionsanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Santosh Mehrotra-InformalityDocument24 pagesSantosh Mehrotra-Informalityanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Neoliberal Subjectivity, Enterprise Culture and New Workplaces: Organised Retail and Shopping Malls in IndiaDocument10 pagesNeoliberal Subjectivity, Enterprise Culture and New Workplaces: Organised Retail and Shopping Malls in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- ARC - Jobless Growth & Labour Conditions in IndiaDocument22 pagesARC - Jobless Growth & Labour Conditions in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Content Server 1Document25 pagesContent Server 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- The Harris - Todaro Model of Labour Migration and Its Implication in Commercial Policy ImplicationDocument101 pagesThe Harris - Todaro Model of Labour Migration and Its Implication in Commercial Policy Implicationanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Contemporary Globalisation and Value Systems What Gains For Developing Countries by Jha and YerosDocument15 pagesContemporary Globalisation and Value Systems What Gains For Developing Countries by Jha and Yerosanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Amiya Kumar Bagchi - Chapter 13Document13 pagesAmiya Kumar Bagchi - Chapter 13anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Conceptually and EmpiricallyDocument11 pagesConceptually and Empiricallyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- CI 403 Monsoon 2023Document4 pagesCI 403 Monsoon 2023anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Barbara Harris Whita and Henry Bernstein-Reviewing-Petty-Commodity-Production-Toward-A-Unified-Marxist-ConceptionDocument9 pagesBarbara Harris Whita and Henry Bernstein-Reviewing-Petty-Commodity-Production-Toward-A-Unified-Marxist-Conceptionanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Disposable People-Kelvin BalesDocument12 pagesDisposable People-Kelvin Balesanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Harriss WhiteDocument38 pagesHarriss Whiteanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Dilthey and GadamerDocument21 pagesDilthey and Gadameranshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Problem Set 1Document1 pageProblem Set 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Property 1Document1 pageProperty 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Employment Plfs 201718Document9 pagesEmployment Plfs 201718anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Global Value Chain-EPWDocument8 pagesGlobal Value Chain-EPWanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- N.Neetha-Data and Data Systems in Unpaid WorkDocument11 pagesN.Neetha-Data and Data Systems in Unpaid Workanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- DN Diametre Nominal-NPS Size ChartDocument5 pagesDN Diametre Nominal-NPS Size ChartSankar CdmNo ratings yet

- IJHSR02Document13 pagesIJHSR02vanathyNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggeris Peralihan Penilaian SatuDocument8 pagesBahasa Inggeris Peralihan Penilaian SatuNazurah ErynaNo ratings yet

- Deviyoga PDFDocument9 pagesDeviyoga PDFpsush15No ratings yet

- Group 2 Ied 126 Charmedimsure Designbriefand RubricDocument4 pagesGroup 2 Ied 126 Charmedimsure Designbriefand Rubricapi-551027316No ratings yet

- School Education and Literacy Department Government of Sindh Office of The District Education Officer (E, S&H.S) District Central KarachiDocument15 pagesSchool Education and Literacy Department Government of Sindh Office of The District Education Officer (E, S&H.S) District Central KarachiNaya PakistanNo ratings yet

- CH 2 - Electrostatic Potential - MCQDocument2 pagesCH 2 - Electrostatic Potential - MCQDeepali MalhotraNo ratings yet

- TFP321 03 2021Document4 pagesTFP321 03 2021Richard TorresNo ratings yet

- Video - Digital Video Recorder 440/480 SeriesDocument3 pagesVideo - Digital Video Recorder 440/480 SeriesMonir UjjamanNo ratings yet

- MR Okor SAC Neurosurgery CVDocument8 pagesMR Okor SAC Neurosurgery CVdrokor8747No ratings yet

- Earth and Life Science: (Quarter 2-Module 4/lesson 4/ Week 4) Genetic EngineeringDocument20 pagesEarth and Life Science: (Quarter 2-Module 4/lesson 4/ Week 4) Genetic EngineeringRomel Christian Zamoranos Miano100% (6)

- RRLDocument3 pagesRRLlena cpaNo ratings yet

- Glucagon For Injection Glucagon For Injection: Information For The PhysicianDocument2 pagesGlucagon For Injection Glucagon For Injection: Information For The PhysicianBryan NguyenNo ratings yet

- Prague Wednesday AM - AcquirerDocument85 pagesPrague Wednesday AM - AcquirerbenNo ratings yet

- Ethics and The Three TrainingsDocument10 pagesEthics and The Three TrainingsJuan VizánNo ratings yet

- Qualification Verification Visit Report - 3022846 - NVQ2Work - 482 - 22032019-1 PDFDocument7 pagesQualification Verification Visit Report - 3022846 - NVQ2Work - 482 - 22032019-1 PDFanthony jamesNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Calculation For Fire Protec7Document3 pagesHydraulic Calculation For Fire Protec7RaviNo ratings yet

- Well ControlDocument21 pagesWell ControlFidal SibiaNo ratings yet

- The Assignment Problem: Examwise Marks Disrtibution-AssignmentDocument59 pagesThe Assignment Problem: Examwise Marks Disrtibution-AssignmentAlvo KamauNo ratings yet

- Amr Assignment 2: Logistic Regression On Credit RiskDocument6 pagesAmr Assignment 2: Logistic Regression On Credit RiskKarthic C MNo ratings yet

- Personality in PsychologyDocument34 pagesPersonality in PsychologyReader100% (1)

- Tractive EffortDocument5 pagesTractive EffortVarshith RapellyNo ratings yet

- 2014 Australian Mathematics Competition AMC Middle Primary Years 3 and 4Document8 pages2014 Australian Mathematics Competition AMC Middle Primary Years 3 and 4Dung Vô ĐốiNo ratings yet

- Nalpeiron Software Licensing Models GuideDocument24 pagesNalpeiron Software Licensing Models GuideAyman FawzyNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Petroleum Limited ProjectDocument6 pagesPakistan Petroleum Limited ProjectRandum PirsonNo ratings yet

- M.development of Endurance For Football PlayersDocument15 pagesM.development of Endurance For Football PlayersJenson WrightNo ratings yet

- Standard Bell Curve For Powerpoint: This Is A Sample Text Here. Insert Your Desired Text HereDocument5 pagesStandard Bell Curve For Powerpoint: This Is A Sample Text Here. Insert Your Desired Text HereGodson YogarajanNo ratings yet

VITHAYATHIL SpacesDiscriminationResidential 2012

VITHAYATHIL SpacesDiscriminationResidential 2012

Uploaded by

anshulpatel0608Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

VITHAYATHIL SpacesDiscriminationResidential 2012

VITHAYATHIL SpacesDiscriminationResidential 2012

Uploaded by

anshulpatel0608Copyright:

Available Formats

Spaces of Discrimination: Residential Segregation in Indian Cities

Author(s): TRINA VITHAYATHIL and GAYATRI SINGH

Source: Economic and Political Weekly , SEPTEMBER 15, 2012, Vol. 47, No. 37

(SEPTEMBER 15, 2012), pp. 60-66

Published by: Economic and Political Weekly

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41720139

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Economic and Political Weekly is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Economic and Political Weekly

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Spaces of Discrimination

Residential Segregation in Indian Cities

TRINA VITHAYATHIL, GAYATRI SINGH

Using 1 Background

ward-level dat

high levels of reside

seven largest

India's increased

increased India's inequality and social and spatial segregation. However,

inequality caste urbanisation and system social has and and and

urbanisation the beenmetro

long spatial the economic segregation. cited asand

economic and a sourcecultural

However, cultural of

Chennai, Bangalore,

environment of cities have been theorised to erode the domi-

each nance of existing social structures,

these of such as caste (Rao 1974).

cities,

more Urban

prominent sociological theory argues that as individualstha

and

groups adapt to city life, prior forms of social organisation

socio-economic statu

weaken and modify (Park 1967; Wirth 1938). A recent study

explanations for

partially supports this line of reasoning and finds thatthe

caste

residential segregatio

inequalities by education, income and social networks are less

strong in India's

highlights metro cities - though the same holds

areas for true in f

less-developed villages - while they are higher in developed

villages and in smaller cities (Desai and Dubey 2011). Recent

social science research on caste in urban India also suggests

that caste identities continue to shape schooling decisions,

educational outcomes and the likelihood of securing jobs

(Munshi and Rosenzweig 2006; Thorat and Newman 2010). In

the light of the Government of India's decision to enumerate

every household by caste, the findings of this paper hope to

contribute to the active debate over if, and how, caste remains

salient in 21st century urbanising India.

Where people live invariably shapes their social interactions

and social networks, health outcomes, and sense of self, other

and community. As "social relations are so frequently and so

inevitably correlated with spatial relations", the residential

locations of individuals and groups reflect the hierarchies of

advantage in a society (Park 1925: 10). For example, a recent

study of eight Indian cities found that historically disadvan-

taged castes disproportionately live in slums (Gupta et al 2009).

Previous quantitative studies of residential segregation in Pune

and in Delhi also find segregation by socio-economic status,

caste and religion, with segregation being the greatest for both

the highest and lowest status groups (Dupont 2004; Mehta

1968, 1969). This paper seeks to extend quantitative techniques

used to measure residential segregation in cities throughout

the world to empirically test the degree to which residential

segregation by caste exists in India's seven largest metro cities,

where we would expect caste inequality to be the least, given

high levels of urbanisation. In addition, this paper will exam-

ine if residential segregation by caste is greater than residential

segregation by socio-economic status.

Trina Using ward-level data from the Census

Vithayathil of India 2001, we

(trina_v

(, gayatri_singh@brown.ed

find high levels of residential segregation by caste in India's

Brown University, United

seven largest cities. Our analysis additionally suggests that

60 September 15, 2012 vol XLVii no 37 Economic & Political WEEKLY

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

residential segregation by caste surpasses residential segrega- by data available at the ward level, which is a large spatial unit

tion by socio-economic status in each city. We offer some pre- both in terms of geographic area and population size. Unlike

liminary explanations for the observed differences in the level Mehta, our measures of caste and socio-economic status are

of residential segregation by caste across India's mega-cities limited to publicly-available census data; therefore, the meas-

with similar median ward sizes. We conclude with a discus- ures are less nuanced and do not allow us to examine differ-

ences across socio-economic groups and caste divisions. In

sion of the limitations of our analysis and highlight areas for

future research. addition, we have been unable to explore how religion shapes

patterns of residence, as census data on religion is publicly

2 Residential Segregation in Urban India available only at the district level.

The relationship between residential location and social status A cautionary note argued by White (1983) is that groups

with high social distance may be found to live in the same

has been a rich area of study in social science research, espe-

neighbourhood but not interacting with each other and vice

cially in the us. As early as the 1920s, urban theorists of the

versa. In this regard, although this paper is based on the as-

Chicago School argued that spatial relations reflect the social

distance between groups (Burgess 1925; Park 1925). Predatingsumption that spatial proximity is important and shapes the

nature of one's social life, we remain acutely aware that shared

the oft-cited Chicago School research on urban spatial rela-

tions by two decades, W E B Du Bois (1903:165) argued in hisresidence in an urban ward represents a range of diverse rela-

tionships and degrees of interaction that our analysis cannot

seminal critique of the racial "colour line" separating blacks

begin to explore. However, our analysis remains an important

and whites in the us that the "physical proximity of home and

dwelling places, the way in which neighbourhoods group preliminary exploration into the macro patterns of caste-based

themselves and the contiguity of neighbourhoods" is one residential

of segregation in India. This paper seeks to contribute

the "main lines of action and communication" across individu-

to the emerging body of social science research that attempts to

als and social groups. understand the salience of caste in contemporary urban India.

Research on Indian cities has also found high degrees of

3 Methodology

residential segregation by socio-economic status, religion and

This section discusses the sources of data, the methods employed,

caste. Particularly important in this regard are a series of studies

the measurement details and the challenges in our examina-

conducted on residential segregation in Pune in the late 1960s

tion of whether there is residential segregation by caste in

that were inspired by the work of Chicago School theorists,

particularly the work by Duncan and Duncan (1955, 195 7) India's

on megacities and how it varies across cities.

racial segregation in the us. In Mehta's (1968, 1969) classic

3.1 Data

studies of patterns of residence in Pune, he draws upon rich

longitudinal data to examine segregation by income, educa-We utilise data from the 2001 Census, a decennial exerci

that aims to compile information on every household in t

tion, occupation, caste and religion. Using city wards as the

country. The enumerators collect household-level data (fo

unit of analysis, he finds that segregation in residence is great-

example, housing quality and materials, number of rooms in

est for groups with the highest and lowest status, both with

regard to socio-economic status and caste. Between 1822 andhouse, and ownership status) and individual-level character

tics (for example, age, gender, years of schooling, literacy statu

1937, Mehta (1969) finds the largest relative increases in the

degree of segregation among brahmins and the depressed caste membership, migration history, and economic activity

classes. He also disaggregates the effect of caste and incomeworkers) for each member of the household. There is no specifi

question on income or consumption level in the census. Th

on the level of residential segregation and finds that only one-

fifth of the level of residential segregation found between caste question enquires

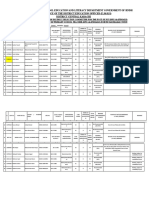

Table 1 : Percentage of Scheduled Castes and

whether an individual

brahmins and the depressed classes1 can be attributed to dif- Scheduled Tribes in India's Seven Largest

Cities in 2001

ferences in income (Mehta 1969). He argues that if incomebelongs

or to a scheduled

City

caste (se) or scheduled

occupation had determined where households of each caste or

Ahmedabad

tribe (st);2 if an indi-

religious group lived, then the extent of residential segregation Bangalore

vidual

would have been much less. In addition, he looks at patterns of is not an se or

Chennai

st, he or she is marked

centralisation and finds that rich and upper-caste Hindus tend Delhi

as "other". The 2001

to be centralised, while those belonging to the low socio- Hyderabad

economic groups and lower castes are decentralised. More- Census classifies 24% of

Kolkata

Indians as belonging to

over, this pattern has lasted for the 150-year period (1822- Mumbai

Source: 2001 Census.

1965) covered in the study (Mehta 1968, 1969). ses and sts. Table 1 lists

This paper seeks to build on Mehta's findings and explore the the percentage of ses and sts in the seven largest cities in

degree of residential segregation by caste and socio-economic India included in this analysis, which are Mumbai, Delhi,

Kolkata,

status in India's seven largest cities at the start of the 21st cen- Chennai, Bangalore, Ahmedabad and Hyderabad.

tury. We would expect that ongoing urbanisation in these citiesIn this analysis, we use data for select urban municipal

corporations. The corporation boundaries coincide with the

would continue to alter the patterns of residential segregation

city limits, within which municipal governments provide

found by Mehta (1968, 1969). Similar to Mehta, we are limited

Economic & Political weekly ESQ September 15, 2012 vol xlvii no 37 1

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

several key public services. Municipalities are divided into whether residential segregation by caste exists within each of

numerous wards and municipal councillors are elected India's megacities.

from wards; therefore, Finally, we calculate the level of residential segregation by

Table 2: Total Population, Number of Wards,

this geographic unit and Median Ward Size in India's Seven socio-economic status. This final measure helps us compare

has both administra- Largest Cities in 2001

whether segregation by socio-economic status or by caste is

City Total No of Median

tive and political sali- the more powerful axis of residential stratification in urban

ency. In our analysis,

Ahmedabad 35,20,085 43 74,957 India. As mentioned earlier, the census does not include infor-

we use aggregated in-Bangalore 43,01,326 100 39,729.5 mation on income or consumption - two common indicators of

dividual-level data pro-

Chennai 43,43,645 155 24,145 socio-economic status. Instead, we use data on male literacy as

vided at the ward level Delhi a blunt measure of socio-economic status. As women in many

for each municipal cor- Hyderabad 36,37,483 24 64,419 parts of the country have been traditionally excluded from

Kol kata 45,72,876 141 29,647

poration. Table 2 lists schooling at higher levels, even among many middle and

Mumbai 1,19,78,450 100 77,667

the total population,Source: 2001 Census. upper class households and particularly among older genera-

number of wards and tions of women, female literacy fails to correlate strongly

median ward size for the seven largest Indian cities. with socio-economic status in the Indian context. Therefore,

to determine the degree of residential segregation by socio-

3.2 Methods

economic status, we calculate the degree of residential segre-

gationby

To explore whether there is residential segregation by caste

male literacy.3

in By comparing this measure to the

level of residential

India's megacities, we look at the variation in residential segre- segregation by caste within each city, we

empirically

gation across three dimensions for each city - gender, testand

caste whether it is socio-economic status or caste

socio-economic status. Table 3: Percentage of Male, SC/ST and that plays a stronger role in structuring patterns of urban

Literate Males in India's Seven Largest residence in India.

Table 3 provides the

Cities in 2001

descriptive statistics for

City Male SC/ST Literate, Our discussion of results concludes by exploring how resi-

these three measures for dential segregation by caste varies across Indian cities. We

Ahmedabad 53.0 13.1 77.6

the cities in our study. compare the level of caste segregation across cities that have a

We find that Delhi has Bangalore

similar median ward size to avoid the possibility of drawing

Chennai

the highest percentage spurious conclusions due to a high correlation between our

Delhi

of a combined sc/st measure of segregation and median ward size (as will be illus-

Hyderabad

population, close to 16% trated in the next section).

Kolkata

of its population, and Mumbai 55.3 5.6 81.4

Mumbai and Kolkata Source: 2001 Census. 3.3 Measurement

the lowest at approximately 6%. Hyderabad (8.3%), Bangalore

To calculate the level of residential segregation for each of th

(12.2%), Ahmedabad (13.1%) and Chennai (13.9%) fall inthree

bet- dimensions discussed above, we use the index of dis

ween with regard to their sc/st population. similarity (denoted by d), a measure of evenness, for two reason

As a baseline measure to serve as a reference for our other First, this index has been hailed as the workhorse of segreg

measures, we first calculate the degree of residential segrega- tion indices for two-group comparisons, such as those afford

tion by gender. Logically, we would expect the residential seg-by the variables of interest in our study. The three indicato

regation by gender to be very low within each city and provideused in this analysis - caste, gender and socio-economic statu

a point of comparison for our social indicator of substantive- are dichotomous in our data. Our measure of caste creates

interest; in this case, caste-based segregation. two groups - sc/st versus other castes. Gender consists of two

We then calculate residential segregation by caste. To do categories - male or female. Socio-economic status is opera-

this, we combine the data on sc/st populations and comparetionalised through the measure of male literacy, which again

it to individuals who have not identified themselves as has two categories - each male is either literate or illiterate.

belonging to an se or st (non-sc/sT). We combine theseThe twosecond reason for using the dissimilarity index is that it has

groups for two reasons. One, the number of st individuals

an easy to comprehend verbal interpretation - "the fraction of

is very low in many cities at the ward level. In addition, one as

group that would have to relocate to produce an 'even'

both ses and sts have been the most excluded and discrimi- (unsegregated) distribution" (White and Kim 2005: 405).

nated groups, they have been afforded similar constitutional There are two methodological challenges in our analysis of

rights in the form of affirmative action policies. Given that

residential segregation given the nature of our data. First,

historically the location of residences in villages has beenwithin each city, the ward size varies. Second, there is a sub-

highly related to untouchability and that sts have lived in stantial variation in mean and median ward size across cities.

relative social isolation, distinguishing between sc/st and To address the first challenge of varying ward size within a

"other" seems to capture a distinction that is particularlycity, we compare the degree of residential segregation within

relevant to patterns of residence in India. By comparing theeach city across different measures - the deviation in residen-

degree of residential segregation by gender as a baseline tial segregation between gender and caste, as well as between

measure to segregation by caste in each city, we observe caste and socio-economic status. This within-city comparison

62 September 15, 2012 vol XLVii no 37 E323 Economic & Political weekly

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SPECIAL ARTICLE

would have to relocate to produce an even distribution. In

helps us make sense of the dissimilarity level for caste in each

city with reference to the other two measures. Kolkata, we find the highest degree of residential segregation

The second challenge of varying ward sizes across cities

by gender, with a dissimilarity index of .065. Preliminary in-

vestigations find a spatial concentration of wards with a high

raises the question of whether differences in dissimilarity

across cities are mere reflections of differences in median proportion of the city's

Table 4: Dissimilarity by Gender, Caste and

Socio-Economic Status in India's Seven

ward size. Since the index of dissimilarity is sensitive to theslum population, especi- Largest Cities

size of underlying area units, in this case wards, it raises a con-ally on the city's peri-

City D_Gender D_Caste D_SES

cern that as the median ward size increases, dissimilarity mayphery. Kolkata's relatively

Ahmedabad 0.008 0.325 0.098

decrease. Given our small sample of cities, testing for the cor-higher unevenness in

Bangalore

relation between median ward size and the dissimilarity level gender distribution could

Chennai

does not provide convincing results. Therefore, we increasedbe due to the concentra-

Delhi

our sample of cities to include the three to five biggest cities across tion of male migrants Hyderabad

a sample of states to represent the eastern, western, northernliving in a clusterKolkata

of

and southern regions of the country (the analysis is not shownwards with a high con-

Mumbai

here, but can be provided on request) . In doing so, we increasedcentration of slums.

Source: 2001 Census.

our sample size from seven to 31 cities. We then calculated the Next, we calculate residential segregation by caste to see

correlation between median ward size and dissimilarity andhow it compares to our baseline of residential segregation by

found a correlation of 0.36. This level of correlation convinced usgender in each city (Table 4, column 2). We find that in each

city the degree of residential segregation by caste is substan-

to take a conservative approach and restrict our comparisons

to cities with similar median ward size. Therefore, for thetially greater than the degree of residential segregation by

seven mega cities in this paper, we carry out comparisonsgender. Ahmedabad has the highest level; while only 0.8% of

among groups of cities with similar median ward sizes. By men would have to move to produce an even distribution of

comparing cities of similar median ward size, we avoid thegender across the city, 32.5% of sc/st would have to move to

problem of any biased comparisons that may arise from highproduce an even distribution by caste across it. Bangalore and

correlations between dissimilarity and median ward size. Chennai have comparably low dissimilarity indexes for gender

In addition to these issues, Fossett and Zhang (2010) have(.016 and .017 respectively), but both cities have much higher

argued that the conventional formulation of the index of dis-levels of residential segregation by caste - 0.278 and 0.293

similarity is subject to a measurement bias when the grouprespectively. In the case of Kolkata, compared to 6.5% of men

having to move to produce an even distribution by gender,

sizes within the census tract (or ward, in our case) are very

small. Massey and Denton (1992: 171) argue that "the index of 36.4% of sc/st would have to move to produce an even distri-

dissimilarity is inflated by random variation when group sizesbution by caste. Hyderabad and Mumbai have the lowest rela-

get small" (Massey 1978). Considering that we had relativelytive increases in dissimilarity between gender and caste, but

small percentages of sc/st population in some cities, for they are still sizeable and substantively significant increases.

example 5.9% in Mumbai, we were worried that we might be While 0.6% and 3.5% of men would have to move in Hydera-

introducing such a measurement bias in our findings. Webad and Mumbai respectively, 19.4% and 22.2% of sc/st

would have to move in Hyderabad and Mumbai respectively to

therefore used the modified formula suggested by Fossett and

Zhang (2010) to calculate an index of dissimilarity but foundproduce an even distribution across each city.

that our dissimilarity values did not change. This is probably To compare the residential segregation by caste and socio-

due to the large size of wards in India such that the combinedeconomic status for each city, we then calculate the dissimilar-

sc/st population is great enough to warrant the use of theity index for socio-economic status using male literacy as our

conventional formula for a dissimilarity measure, which isproxy (Table 4, column 3). We find that the degree of residen-

what we present in this paper. tial segregation by socio-economic status across India's seven

largest cities varies from a dissimilarity of .098 (Ahmedabad)

4 Results to 0.211 (Kolkata). We discover that in all seven cities the degree

For our baseline measure in each city, we calculate of residential

the degree segregation by caste is greater than the degree of

residential

of residential segregation by gender (Table 4, column segregation by socio-economic status.4 We also find

1). We

find that the degree of residential segregation by that the levelisof residential segregation by socio-economic status

gender

small across India's seven largest cities though itisdoes

greater than the residential segregation by gender. Ahmeda-

vary

bad has theIn

from a dissimilarity of .006 (Hyderabad) to .065 (Kolkata). greatest percentage difference between segrega-

tion by socio-economic

Hyderabad and Ahmedabad, we find that the residential seg- status and caste. While 9.8% of literate

regation by gender is negligible - less than 1% ofmen

men would

wouldhave to move to produce an even distribution by

have to relocate to produce an even distribution ofsocio-economic

men across status, 32.5% of sc/st would have to move to

produceisanalso

the city. The degree of residential segregation by gender even distribution by caste across the city. Within

small in Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi and Mumbai,each city, the dissimilarity index for residential segregation by

ranging

caste iscities.

from a dissimilarity of .016 to .035 across the four substantially greater than the dissimilarity index for

segregation

Among the four, it is the highest in Mumbai - 3.5% of men by socio-economic status.

Economic & Political weekly

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

We now return to our calculation of dissimilarity for resi- as the slums are often heavily populated by ses, including

dential segregation by caste, which as stated earlier varies rural-urban migrants who are unable to find other affordable

from .194 to .364 across the cities in our study (Table 4, column 2). housing (Tsujita 2009).

Given our previous findings that dissimilarity and median Considering the remaining two cities in this group, Hyderabad

ward size are correlated, we compare the level of caste segre- (0=0.194) appears to be the least segregated and Mumbai

gation across mega cities with a similar median ward size (see (d =0.222) follows close on its heels. In the case of Mumbai,

Table 2). Based on this criterion, we are able to create two the relatively low level of caste segregation compared to Delhi

groups of comparison cities - one, Chennai and Kolkata; and could be due to the even spatial distribution of slums within

two, Hyderabad, Mumbai, Delhi and Ahmedabad. Given its the urban municipality. Takeuchi et al (2008: 68) argue that

ward size, we are unable to compare Bangalore with any slum-dwellers in Mumbai are "considerably more integrated

other megacity.5 among non-slum dwellers than in other cities: 40% of slum-

In the first comparison, we find that Kolkata (0=0.364) is dwellers live in central Mumbai (zones 1-3)". The integrated

approximately 19.5% more segregated by caste than Chennai nature of slum locations is likely to contribute to the city's rela-

(d= 0.293). One potential explanation for the lower level of tively lower dissimilarity index.

residential segregation by caste in Chennai is the long history Unlike other cities discussed so far, Hyderabad's population

of successful lower caste social movements in Tamil Nadu, of of Muslims is approximately triple the country's average and

which it is the capital. The Dravidian nationalist movement, significantly larger than the comparison cities. In the case of

also known as the Self-Respect Movement, originated in Tamil Hyderabad, as in the other cities in this study, it would be

Nadu in 1925 and sought to end the oppression of lower castes interesting to calculate residential segregation by religion.

by upper castes, particularly brahmins. For the comparison city, We speculate that in Hyderabad religion is likely to be a more

Kolkata, Chakroborty (2005) argues that the spatial segrega- important axis of residential segregation. Unfortunately, we are

tion legacy of the colonial period has continued into the post- unable to perform this analysis because census data on religion

colonial city on several dimensions, including socio-economic is made available at the district level, which does not allow us

status, caste and religion. Clark and Landes (2010) in a unique to analyse residential segregation within a city at ward level.

study utilising a large sample of 2.2 million surnames from the

2010 Kolkata voters' list find that brahmin castes cluster in 5 Conclusions

the same postal codes, or residential space; thus pointing to

Ata the start of the 21st century, we find that caste still remains

a real axis of urban residential segregation in India's seven

persistent role of caste in the spatial patterning of social

groups in Kolkata.6 largest metro cites. In each of these cities, our analysis finds

residential segregation by caste to be sizeably larger than the

Within our second comparison group, we find that Ahmedabad

level of segregation by socio-economic status. Caste has his-

(d= 0.325) has the highest residential segregation by caste, fol-

lowed closely by Delhi (0=0.319), while Mumbai (0=0.222)torically shaped the organisation of residential space, espe-

and Hyderabad (0=0.194) are considerably less segregated. cially

In at the village level, and it appears to continue to do so in

the case of Ahmedabad, a proposed study of inter-communal contemporary urban India.

and inter-caste "ghettoism" suggests that "the city has grownSome limitations of this study are worth highlighting. As

into pockets of particular communities or castes" (Sapovadia discussed earlier, the ward sizes in India's largest cities are

2007). Sapovadia further notes that distinct harijan (ses that quite large. Although the median ward size across India's

experienced pre-independence untouchability) pockets can seven be largest cities varies - from approximately 25,000 to

identified in the city neighbourhoods of Behrampura, Bhudar- 70,000 people - they are large when compared to the median

pura, Asarwa, Jivraj Park and Asarwa. The city was the siteward of size in cities in other countries. The largeness of the

ward size undoubtedly masks important micro-level segrega-

two significant caste conflicts in the 1980s, pointing to the un-

easy nature of caste relations. tion processes and trends at the intra-ward level. In addition,

these processes are likely to differ across wards within the

With respect to Delhi, Dupont (2004) provides useful insights

same city and across cities, making comparisons difficult.

into the reasons for prevailing caste segregation, especially

pertaining to the ses. Although Dupont (2004) does not calcu-

While in this sense the findings of this paper make only a small

late a summary measure of segregation, she highlights the contribution towards understanding patterns of residential

clustering of sc/st populations in various parts of Delhi by

segregation, it is nonetheless an important precursor to high-

mapping ward-level 1991 Census data on the proportionlighting

of the need for a more coherent research agenda that

attempts to understand spatial inequality at the neighbour-

sc/st in each ward.7 The author puts forward two reasons for

the expected high levels of caste-based segregation. First,

hood level. We hope that the tradition of neighbourhood studies

harijan settlements in surrounding rural areas, where the out-

and qualitative research in urban India will seek to fill in the

castes were forced to live, have over time been incorporated

gaps in our narrative.

into the city limits as Delhi's municipal boundaries have Second, while much of the urban story of residential segre-

expanded. Second, the long-term slum resettlement efforts gation

of by sc/st seems to overlap with the spatial configura-

the government aim to relocate people on the peripheries tion

of of slums in India's largest cities, we have not analysed

the city (Dupont 2004), thus contributing to caste segregation

data on slums in this paper. Our preliminary conclusions rely

64 SEPTEMBER 15, 2012 VOL XLVII NO 37 I Mi* Vi Economic & Political WEEKLY

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

on the contribution of past research, which finds a high corre- the Indian government to make religion and more specific ed-

lation between the sc/st and slum populations in Indian cit- ucation data available at the ward level, particularly for older

ies. In the future, we hope to incorporate ward-level data on censuses, now that data for Census 2011 has been collected

the slum population to test for this overlap. However, the find- and will be available shortly. In addition, the development of

ing that residential segregation by caste trumps over segrega- secure data rooms where household-level data for key socio-

tion by socio-economic status in each of the seven cities pro- economic and demographic variables could be made available

vides us some confidence that the mechanisms producing resi- for researchers at the ward or sub-ward level would greatly

dential segregation by caste are a source of inequality worth be- increase the depth and scope of our understanding of residen-

ing understood independently. Although faced with data limi- tial segregation in the urban Indian context.

tations that prevent in-depth insights into the underlying

Future Areas of Research

mechanisms of caste segregation, we believe that this study

provides important findings about stratification by caste in With regard to future areas of research, a comparative histori-

modern urban India. cal study of groups or pairs of cities would be a worthwhile

Third, we would have liked to compare the change in resi- exercise to better understand the mechanisms that lead to the

dential segregation by caste over time for each city, as Mehta observed patterns of segregation within and across cities. Such

(1968, 1969) does in his studies on Pune. Modifications to the a historical perspective would also complement future efforts

number and size of wards in each city between censuses make to collect primary data and find methods to improve the

a longitudinal analysis of caste segregation using ward-level, comparability of census or survey data across cities. Another

aggregate data for each city nearly impossible. The one case in extension of research on caste-based residential segregation

which existing census data may allow for a longitudinal analy- could be the undertaking of housing audit studies, similar to

sis is if each newly created ward in a city is a subset of one, and those used by scholars in the us since the 1980s to document

only one, previous ward. the discrimination in housing faced by African Americans (for

Fourth, alongside caste, residential segregation by religion example, Yinger 1986). A precedent for comparative under-

is itself a separate and important area of examination. Future standings of social inequality based on the Indian caste system

studies should attempt to undertake such investigation using and of the us racial hierarchy goes as far back as early 20th

survey data, given the aggregated nature of available data for century scholarship. While sociologists in the 1930s and 1940s

religion in the census. For example, in Ahmedabad, while attempted to substantively understand race relations in the us

caste riots took place in the 1980s, Hindu-Muslim religious via the lens of caste discrimination (for example, Dollard 1937;

riots raised their ugly head more recently in 2002 (see Varshney Immerwahr 2007; Myrdal 1944; Sutherland 1942; Warner

2002 for an analysis of communal conflicts in Indian cities). 1936), Indian studies on residential segregation by caste today

Similarly, as discussed above, analysing residential segrega- would benefit from the methodological advances in studies of

tion by religion would improve our understanding of socio- race stratification in the us. A successful transportation of

spatial inequality in Hyderabad. such methods is seen in the volume edited by Thorat and

While many of the limitations of our studies are common Newman (2010), applied to the context of caste and religious

across quantitative studies of residential segregation, several discrimination in job-seeking in the corporate sector in India.

challenges relate to the restricted nature of publicly available Finally, we intend to extend this analysis to study caste

census data. Unlike several other countries, the Indian govern- segregation in smaller Indian cities where global forces as well

ment has been less forthcoming about making significant dis- as urbanisation have been less pervasive. Another advantage

aggregated data available from past census rounds. Avenues of looking at smaller cities is that the ward size is generally

for making disaggregated data available, including samples of smaller than big cities, thus rendering an even more meaning-

census micro data disaggregated at the household level, exist; ful measurement of spatial segregation. In doing so, we hope

such as iPUMS-International, an initiative by the University of to be able to shed light on caste relations in India across different

Minnesota Population Center.8 At the very least, we encourage urban scales in the future.

NOTES 4 This result continues to hold even when we forms an uneven ring around the previous

use a measure of literacy that includes both municipal boundary. The city's highly publicised

1 Mehta uses this term, which became widely

male and female populations of illiterate and rise in the global information economy and

used in the Indian bureaucracy during the co-

literate individuals. related growth in the information technology (IT)

lonial period, to refer to the most socially and and biotechnology sectors have resulted in high

5 Bangalore's level of segregation cannot be com-

economically disadvantaged castes. levels of regional in-migration across socio-

pared to the other cities but a few comments

2 The Indian Constitution specifies that "noaboutper-

the city are in order. In 1991, the city of economic groups and an increased demand for

son who professes a religion different from the had a population of 2.67 million

Bangalore new patterns of residential living and commer-

Hindu, the Sikh or the Buddhist religion shall

people; 10 years later, the city's population had cial land use (Patni 1999)- For example, the

be deemed to be a member of a Scheduled increased by 38% to 4.2 million (Government growth of the IT sector, and the related

Caste" (Government of India 1950). of India 2005; Nanda 1992). An additional com- increases in wages and in the number of high

3 We also replicated the analysis using all literate ponent to Bangalore's growth has been the ex- wage earners, has produced new demand for

versus all illiterate population to ensure that pansion of the city's geographic area. In 1991, luxury apartments in the urban core and for

the results using male literacy did not bias our the city of Bangalore had an area of 192 square gated suburban communities and industrial

comparison of socio-economic segregation kilometres; in 2001 the city's area was 226 sq technology parks in the periphery. At the same

with caste segregation. We find the compara- km (Government of India 2001a, b). The addi- time, the in-migration of individuals from rural

tive results are robust to either measure. tional land that was incorporated into the city areas to work in the booming construction and

Economic & Political weekly E3B3 September 15, 2012 vol xlvii no 37 ^5

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

other low-wage service industries is likely to images/asa/docs/pdf/1925%

Distribution of Population", Directorate of Cen- 2oPresidential%

change the dynamics in Bangalore's historically sus Operations, Bangalore, Karnataka.2oAddress%2o(Robert%2oPark).pdf, Accessed

small slum population and rapidly urbanising - (2001b): "Growth of Urban Population on 24 in

June 2011.

Kar-

peri-urban areas. The periphery of Bangalore - (1967

nataka 1971-2001", Chapter 10, Census of[1925]):

India "The City: Suggestions for the

has been a place where the "new demands of 2001, Karnataka, Paper 2 of 2001: "Provisional

Investigation of Human Behaviour in the Urban

international capital and existing demands of Population Totals - Rural-Urban Distribution

Environment" in Robert Park and Ernest Burgess,

local firms and populations" compete for land of Population", Directorate of Census Opera-

The City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

and resources (Keivani and Mattingly 2007). tions, Bangalore, Karnataka. Patni, A (1999) : "Silicon Valley of the East: Bangalore's

6 West Bengal, the state in which Kolkata is located, - (2005): Census of India 2001 [Electronic Resource],

Boom", Harvard International Review, 8-9.

is well known for its strong communist sympa- Volume 10: Andhra Pradesh , Karnataka, Laksha-

Rao, MSA (1974): Urban Sociology in India: Reader

thies. However, in Kolkata, our calculations and dweep, Office of the Registrar General,and

New Delhi.

Source Book (New Delhi: Orient Longman).

existing research find relatively high levels of Gupta, Kamla, Fred Arnold and H Lhungdim

Sapovadia, (2009):

Vrajlal K (2007): "A Critical Study on

segregation both by caste and class (and ethnic Health and Living Conditions in Eight Indian

Relations between Inter- Communal/Caste

group). With regard to class, residential segre- Cities, National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3),

Ghettoism and Urbanisation Pattern vis-à-vis

gation is not confined to the poor in Kolkata but India, 2005-06 (Mumbai: International Institute

Spatial Growth, Efficiency and Equity: A Case

also to clustering of the business elite, who are for Population Sciences; Calverton, Study

Maryland:

of Ahmedabad, India", Working Paper,

mainly prosperous entrepreneurs from Rajas- ICF Macro).

than who tend to live in the Burrabazaar or Social Science Research Network (SSRN),

Immerwahr, Daniel (2007): "Caste or Colony? Indian- http://ssrn.com/abstract= 987752, accessed on

Park Street area; professional south Indians ising Race in the United States", Modern Intel-

5 March 2011.

who tend to reside around the Lakes; and pro-

lectual History, 4 (2), pp 275-301. Sutherland, Robert L (1942): Color, Class and Per-

fessional Bengalis who live in south Calcutta

Keivani, R and M Mattingly (2007): "The Interface sonality (Washington DC: American Council

(Clark and Landes 2010).

of Globalisation and Peripheral Lands in Cities on Education).

7 Note that due to changes in the number and of the South", International Journal of Urban

size of wards between Census 1991 and 2001 Takeuchi, Akie, Maureen Cropper and Antonio Bento

and Regional Research, 31 (2), pp 459-74.

and again more recently, we are unable to do a (2008): "Measuring the Welfare Effects of Slum

Massey and Denton (1992): American Apartheid: Improvement Programs: The Case of Mumbai",

comparative longitudinal analysis of caste

Segregation and the Making of the Underclass Journal of Urban Economics, 64 (1): 65-84.

segregation index across the cities.

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

8 "IPUMS-International is an effort to inventory, Thorat, Sukhadeo and Katherine Newman (2010):

Massey, Douglas S (1978): On the Measurement of Blocked by Caste: Economic Discrimination

preserve, harmonise, and disseminate census

Segregation as a Random Variable", American and Social Exclusion in Modern India (Delhi:

microdata from around the world. The project

Sociological Review, 43: 587-90.

has collected the world's largest archive of Oxford University Press).

Mehta, S (1968): "Patterns of Residence in Poona

publicly available census samples. The data are Tsujita, Yuko (2009): Deprivation of Education in

coded and documented consistently across (India) by Income, Education, and Occupation Urban Areas: A Basic Profile of Slum Children in

(1937-65)", American Journal of Sociology, 73 (4),

countries and over time to facilitate comparative Delhi, India, Japan External Trade Organisation,

research. IPUMS-International makes these data PP 496-508.

Institute of Developing Economies, Chiba.

available to qualified researchers free of charge - (1969): "Patterns of Residence in Poona, India,

Varshney, Ashutosh (2002): Ethnic Conflict and Civic

through a web dissemination system." See by Caste and Religion: 1822-1965", Demography,

Life: Hindus and Muslims in India (New Haven:

https://international.ipums.org/international/ 6 (4), PP 473-91-

Yale University Press).

Munshi, Kaivan and Mark Rosenzweig (2006):

"Traditional Institutions Meet the Modern Warner, W Lloyd (1936): "American Caste and Class",

American Journal of Sociology, 42 (2), pp 234-37.

REFERENCES World: Caste, Gender, and Schooling Choice in

a Globalising Economy", American EconomicWirth, Louis (1938): "Urbanismi as a Way of Life",

Burgess, Ernest W (1925): "The Growth Review,

of the96 City:

(4), pp 1225-52. American Journal of Sociology, 44 (1), pp 1-24.

An Introduction to a Research Project" in

Myrdal, Gunnar (1944): An American Dilemma:White,

The Michael J (1983): "The Measurement of

Robert Park, Ernest W Burgess and Roderick D Spatial Segregation", American Journal of

Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (New

McKenzie, The City (Chicago: University of Sociology, 88 (5), pp 1008-18.

York: Harper and Row).

Chicago Press). White,

Nanda, A R (1992): Census of India 1991: Series 1 M J and A Kim (2005): "Residential Segre-

Chakroborty, S (2005): "From Colonial City to Glo- gation", Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, 3,

India, Volume 1: Final Population Totals (New

bal City? The Far from Complete Spatial Trans- PP 403-09.

Delhi: Office of the Registrar General).

formation of Calcutta" in N R Fyfe and J T Ken-

Yinger,

Park, Robert (1925): "The Concept of Position in John (1986): "Measuring Racial Discrimination

ny (ed.), The Urban Geography Reader (London

Sociology", American Sociological Associationwith Fair Housing Audits: Caught in the Act",

and New York: Routledge), pp 84-92.

presidential address, http://www.asanet.org/ American Economic Review, 76 (5), pp 881-93.

Clark, Gregory and David Zach Landes (2010): Caste

versus Class : Social Mobility in India 1870-2010

Compared to England, 1086-2010 (Berkeley:

University of California Press). Survey

Desai, Sonalde and Amaresh Dubey (2011): "Caste

in 21st Century India: Competing Narratives", September 8, 2012

Economic & Political Weekly, 46 (11), pp 40-49.

Revisiting Communalism and Fundamentalism in India

Dollard, John (1937): Caste and Class in a Southern

by

Town (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Du Bois, WEB (1903): The Souls of Black Folks Surya Prakash Upadhyay, Rowena Robinson

(Chicago: AC McClurg & Co).

This comprehensive

Duncan, Otis Dudley and Beverly Duncan review of the literature on communalism - and its virulent offshoot, fundamentalism

(1955):

"Residential Distribution and Occupational

- in India considers the various perspectives from which the issue has sought to be understood, from

Stratification", American Journal of Sociology,

precolonial and colonial times to the post-Independence period. The writings indicate that communalism

Vol 60, No 5, pp 493-503.

is an outcome

- (1957) : The Negro Population of Chicago of the competitive aspirations of domination and counter-domination that began in

(Chicago:

University of Chicago Press). colonial times. Cynical distortions of the democratic process and the politicisation of religion in the

Dupont, V (2004): "Socio-Spatial Differentiation

early decades of Independence intensified it. In recent years, economic liberalisation, the growth of

and Residential Segregation in Delhi: A Ques-

opportunities and a multiplying middle class have further aggravated it. More alarmingly, since the

tion of Scale?", Geoforum, 35, pp 157-75.

1980s, Hindu

Fossett, Mark and Wenquan Zhang (2010): communalism has morphed into fundamentalism, with the Sangh parivar and its cultural

"Unbiased

Indices of Uneven Distribution and politics of Hindutva playing ominous roles.

Exposure:

New Alternatives for Segregation Analysis",

unpublished paper, August. For copies write to:

Government of India (1950): "Indian Constitution: Circulation Manager,

Scheduled Caste Order", http://lawmin.nic.in/ld/

subord/rule3a.htm, accessed on 20 March 2011. Economic and Political Weekly,

320-321, A to Z 2,

- (2001a): "Bangalore Through Ages", Chapter Industrial Estate, Ganpatrao Kadam Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai 400 013.

Census of India 2001, Karnataka, Paper 2 of 2001: email: circulation@epw.in

"Provisional Population Totals - Rural-Urban

66 SEPTEMBER 15, 2012 vol XLVii no 37 CH3 Economic & Political weekly

This content downloaded from

202.41.10.109 on Sun, 05 May 2024 06:23:26 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Claudia Goldin-Career and FamilyDocument1 pageClaudia Goldin-Career and Familyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Bigger Than This - Fabian Geyrhalter - 1Document8 pagesBigger Than This - Fabian Geyrhalter - 1abas004No ratings yet

- The Music in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space OdysseyDocument27 pagesThe Music in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space OdysseyJoris Daniel100% (1)

- Discriminated Urban SpacesDocument10 pagesDiscriminated Urban SpacesKapil Kumar GavskerNo ratings yet

- SA LIII 50 221218 Sriti GangulyDocument8 pagesSA LIII 50 221218 Sriti GangulyVikash KumarNo ratings yet

- Diasporas Transforming HomelandsDocument9 pagesDiasporas Transforming HomelandsVijay SinghNo ratings yet

- Caste and The Indian Economy: Kaivan MunshiDocument55 pagesCaste and The Indian Economy: Kaivan MunshiIsak PeuNo ratings yet

- Caste in 21st CentDocument22 pagesCaste in 21st CentkittyNo ratings yet

- Indian Anthropological Association Indian AnthropologistDocument17 pagesIndian Anthropological Association Indian Anthropologistindiabhagat101No ratings yet

- Contemporary Relevance of Jajmani RelationsDocument10 pagesContemporary Relevance of Jajmani RelationsAnonymous MTTd4ccDqO0% (1)

- Lina Carranza & Diego Vargas: National Univertisty of ColombiaDocument12 pagesLina Carranza & Diego Vargas: National Univertisty of ColombiaDiego VargasNo ratings yet

- Tribes As Indigenous People of IndiaDocument8 pagesTribes As Indigenous People of IndiaJYOTI JYOTINo ratings yet

- Exclusive Inequalities Merit, Caste and Discrimination in Indian Higher EducaDocument8 pagesExclusive Inequalities Merit, Caste and Discrimination in Indian Higher EducaArun PrakashNo ratings yet

- Isolated by Caste: Neighbourhood-Scale Residential Segregation in Indian MetrosDocument22 pagesIsolated by Caste: Neighbourhood-Scale Residential Segregation in Indian MetrosadiksayyuuuuNo ratings yet

- Caste in Contemporary India - Flexibility and PersistenceDocument21 pagesCaste in Contemporary India - Flexibility and PersistenceRamanNo ratings yet

- AGGARWAL CastePowerElite 2015Document8 pagesAGGARWAL CastePowerElite 2015Abijeeth ThirumalainathanNo ratings yet

- Caste Diversity in Corporate BoardroomsDocument6 pagesCaste Diversity in Corporate BoardroomsAbijeeth ThirumalainathanNo ratings yet

- Resourcefulness of Locally-Oriented Social Enterprises - Implications For Rural Community DevelopmentDocument10 pagesResourcefulness of Locally-Oriented Social Enterprises - Implications For Rural Community DevelopmentMembaca Tanda ala Pendidik RumahanNo ratings yet

- Politics of Language, Religion and Identity - Tribes in IndiaDocument9 pagesPolitics of Language, Religion and Identity - Tribes in IndiaVibhuti KachhapNo ratings yet

- Virginia XaxaDocument8 pagesVirginia XaxaMEGHA YADAVNo ratings yet

- Gender Urban Space and The Right To Everyday LifeDocument13 pagesGender Urban Space and The Right To Everyday LifePaulo SoaresNo ratings yet

- Caste SystemDocument4 pagesCaste Systemvrindasharma300No ratings yet

- Life Satisfaction and Well-Being at The Intersections of Caste and Gender in IndiaDocument15 pagesLife Satisfaction and Well-Being at The Intersections of Caste and Gender in IndiaLovis KumarNo ratings yet

- Building Convergence of Ethnicity in The Unitary State of The Republic of Indonesia DdisDocument10 pagesBuilding Convergence of Ethnicity in The Unitary State of The Republic of Indonesia Ddis18Nyoman Ferdi Chandra P.No ratings yet

- Sense of Community in New Urbanism NeighbourhoodsDocument5 pagesSense of Community in New Urbanism NeighbourhoodsGeley EysNo ratings yet

- Singh ImportanceCasteBasedHeadcounts 2023Document18 pagesSingh ImportanceCasteBasedHeadcounts 2023rinajha8204No ratings yet

- Social Exclusion in Modern Urban Space. 2022Document12 pagesSocial Exclusion in Modern Urban Space. 2022Ananda BritoNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 10-Sep-2020Document14 pagesAdobe Scan 10-Sep-2020Cheshta DixitNo ratings yet

- SRC July 6 ObservationsDocument18 pagesSRC July 6 Observationssumeet raiNo ratings yet

- Amin, Collective CultureDocument21 pagesAmin, Collective CultureahceratiNo ratings yet

- Indian Village: Discrete and Static Image British Administrator-Scholars Baden-Powell Henry MaineDocument4 pagesIndian Village: Discrete and Static Image British Administrator-Scholars Baden-Powell Henry MaineManoj ShahNo ratings yet

- (Ge) Political Science Human Right Part-1 Eng.Document155 pages(Ge) Political Science Human Right Part-1 Eng.noxar10515No ratings yet

- Indian DemocracyDocument11 pagesIndian DemocracydoitvarunNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Tribe and Their Major Problems in India: School of Development StudiesDocument17 pagesThe Concept of Tribe and Their Major Problems in India: School of Development Studiesshruti vermaNo ratings yet

- The Mirage of A Caste-Less Society in IndiaDocument6 pagesThe Mirage of A Caste-Less Society in IndiaMohd MalikNo ratings yet

- 828 Improving The Social Sustainability of High Rises PDFDocument8 pages828 Improving The Social Sustainability of High Rises PDFAlbert TalonNo ratings yet

- CESC FinalsDocument7 pagesCESC FinalslantakadominicNo ratings yet

- Caste System Today in IndiaDocument20 pagesCaste System Today in IndiaSharon CreationsNo ratings yet

- Convergencia de Los Emprendimientos en Casa y El Espacio DomesticoDocument7 pagesConvergencia de Los Emprendimientos en Casa y El Espacio DomesticoRafael BerriosNo ratings yet

- From Caste To Class in Indian SocietyDocument15 pagesFrom Caste To Class in Indian SocietyAmitrajit BasuNo ratings yet

- Activity 1-Ucsp AgodoloDocument7 pagesActivity 1-Ucsp AgodoloCarl John AgodoloNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument10 pages1 PBmahtrian nopeNo ratings yet

- Urbanism As Way of LifeDocument20 pagesUrbanism As Way of LifeSaurabh SumanNo ratings yet

- Spatial Analysis of Social Inequality in Moradabad CityDocument7 pagesSpatial Analysis of Social Inequality in Moradabad CityResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- Sociology AssignmentDocument23 pagesSociology AssignmentManushi SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Census and CasteDocument9 pagesCensus and CasteManya TrivediNo ratings yet

- Caste, Class and GenderDocument30 pagesCaste, Class and GenderVipulShukla83% (6)

- Economic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyDocument4 pagesEconomic and Political Weekly Economic and Political WeeklyNiharikaNo ratings yet

- Convolution Dwelling System As Alternative Solution in Housing Issues in Urban Area of BandungDocument15 pagesConvolution Dwelling System As Alternative Solution in Housing Issues in Urban Area of BandungHafiz AmirrolNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Imperative GramswarajDocument25 pages21st Century Imperative Gramswarajdonvoldy666No ratings yet

- Q2 - Understanding Curriculum MapDocument6 pagesQ2 - Understanding Curriculum MapWillisNo ratings yet

- Adverse Conditions For Wellbeing at The Neighbourhood Scale - 2020 - WellbeingDocument11 pagesAdverse Conditions For Wellbeing at The Neighbourhood Scale - 2020 - WellbeingBLOODY BLADENo ratings yet

- Spatial Inequality and Untouchability: Ambedkar's Gaze On Caste and Space in Hindu VillagesDocument13 pagesSpatial Inequality and Untouchability: Ambedkar's Gaze On Caste and Space in Hindu VillagesRitika SinghNo ratings yet

- Caste & Indian EconomyDocument79 pagesCaste & Indian Economysibte akbarNo ratings yet

- Year Title of Paper Author Variables Research Methods/Appr Oach InferenceDocument9 pagesYear Title of Paper Author Variables Research Methods/Appr Oach InferenceAr Apurva SharmaNo ratings yet

- Portes DiversitySocialCapital 2011Document20 pagesPortes DiversitySocialCapital 2011Bubbles Beverly Neo AsorNo ratings yet

- LocalWisdom AuliaRDocument9 pagesLocalWisdom AuliaRberkasnindaNo ratings yet

- 145793840413ETDocument12 pages145793840413ETrahulNo ratings yet

- Law and Social Transformation in IndiaDocument12 pagesLaw and Social Transformation in IndiaUtkarrsh Mishra100% (1)

- Women's Work, Welfare and Status Forces of Tradition and Change in IndiaDocument15 pagesWomen's Work, Welfare and Status Forces of Tradition and Change in IndiaAshok KumarNo ratings yet

- Urban Ethnography.Document8 pagesUrban Ethnography.SebastianesfaNo ratings yet

- Caste, Class, and Power: Changing Patterns of Stratification in a Tanjore VillageFrom EverandCaste, Class, and Power: Changing Patterns of Stratification in a Tanjore VillageNo ratings yet

- Space and Pluralism: Can Contemporary Cities Be Places of Tolerance?From EverandSpace and Pluralism: Can Contemporary Cities Be Places of Tolerance?No ratings yet

- MSMEs Introduction-Rashmi ChaudharyDocument46 pagesMSMEs Introduction-Rashmi Chaudharyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Praveen Jha-Labour Condition in Rural IndiaDocument134 pagesPraveen Jha-Labour Condition in Rural Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Display PDF - PHPDocument21 pagesDisplay PDF - PHPanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Robert Ezra IntroductionDocument2 pagesRobert Ezra Introductionanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Changing Contours of Solid Waste Management in IndiaDocument11 pagesChanging Contours of Solid Waste Management in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Archana Prasad-Integrated Farm Solutions and Its Impact On Small Farmers A Case Study of Bayer in Karnal, Haryana, GPN Working Paper NumbeDocument90 pagesArchana Prasad-Integrated Farm Solutions and Its Impact On Small Farmers A Case Study of Bayer in Karnal, Haryana, GPN Working Paper Numbeanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Agrarian Question of Capital and LabourDocument35 pagesAgrarian Question of Capital and Labouranshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Gandhi and MSMEsDocument9 pagesGandhi and MSMEsanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Law and COntradictionsDocument13 pagesLaw and COntradictionsanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Santosh Mehrotra-InformalityDocument24 pagesSantosh Mehrotra-Informalityanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Neoliberal Subjectivity, Enterprise Culture and New Workplaces: Organised Retail and Shopping Malls in IndiaDocument10 pagesNeoliberal Subjectivity, Enterprise Culture and New Workplaces: Organised Retail and Shopping Malls in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- ARC - Jobless Growth & Labour Conditions in IndiaDocument22 pagesARC - Jobless Growth & Labour Conditions in Indiaanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Content Server 1Document25 pagesContent Server 1anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- The Harris - Todaro Model of Labour Migration and Its Implication in Commercial Policy ImplicationDocument101 pagesThe Harris - Todaro Model of Labour Migration and Its Implication in Commercial Policy Implicationanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Contemporary Globalisation and Value Systems What Gains For Developing Countries by Jha and YerosDocument15 pagesContemporary Globalisation and Value Systems What Gains For Developing Countries by Jha and Yerosanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Amiya Kumar Bagchi - Chapter 13Document13 pagesAmiya Kumar Bagchi - Chapter 13anshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- Conceptually and EmpiricallyDocument11 pagesConceptually and Empiricallyanshulpatel0608No ratings yet

- CI 403 Monsoon 2023Document4 pagesCI 403 Monsoon 2023anshulpatel0608No ratings yet