Professional Documents

Culture Documents

R59 Designing For Profound Experiences

R59 Designing For Profound Experiences

Uploaded by

Sara de SáCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Tutorial 6 AnswersDocument5 pagesTutorial 6 AnswersMaria MazurinaNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking For Startups - AntlerDocument36 pagesDesign Thinking For Startups - AntlerClarisse LamNo ratings yet

- vIXwe-J0W59C7PPe - XTWzq-BrhWkPAWVU-Desing ThinkingDocument11 pagesvIXwe-J0W59C7PPe - XTWzq-BrhWkPAWVU-Desing ThinkingLiz Soriano MogollónNo ratings yet

- Research in Design ThinkingDocument8 pagesResearch in Design ThinkingHasby Rahim Rahmatullah hasbyrahim.2020No ratings yet

- Can Design Thinking Still Add ValueDocument5 pagesCan Design Thinking Still Add Valuexiaonan luNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking ToolkitDocument28 pagesDesign Thinking ToolkitIoana Kardos100% (13)

- Design ThinkingDocument8 pagesDesign ThinkingSomeonealreadygotthatusername.No ratings yet

- Module - L6 (1) EntrepDocument3 pagesModule - L6 (1) EntrepDianne ObedozaNo ratings yet

- Design ThinkingDocument10 pagesDesign ThinkingSanjanaaNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking ProcessDocument15 pagesDesign Thinking ProcessSavitaNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument19 pagesArticlejelisacharles8No ratings yet

- Lecture 4 - Design ThinkingDocument43 pagesLecture 4 - Design ThinkingDannica Keyence MagnayeNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Design - Module 1Document11 pagesIntroduction To Design - Module 1Disha KaushalNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking An OverviewDocument8 pagesDesign Thinking An OverviewFlávio AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Productive Interaction: Designing For Drivers Instead of PassengersDocument19 pagesProductive Interaction: Designing For Drivers Instead of PassengersPhilip van AllenNo ratings yet

- Design 3.0 WassermannDocument10 pagesDesign 3.0 WassermannceleoramNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking: The Future of Business StrategyDocument19 pagesDesign Thinking: The Future of Business StrategyDameon GreenNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Human-Centered DesignDocument17 pagesAn Introduction To Human-Centered DesignMusse MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Psychology of DesignDocument18 pagesPsychology of Designsandra quinnNo ratings yet

- Questioning The Center of Human CenteredDocument9 pagesQuestioning The Center of Human CenteredakhmadNo ratings yet

- Gabriela Goldschmidt Anat Litan Sever - Inspiring Design Ideas With TextsDocument17 pagesGabriela Goldschmidt Anat Litan Sever - Inspiring Design Ideas With TextsOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking ProcessDocument14 pagesDesign Thinking ProcessPatrica LybbNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1.4 Design Vs Design ThinkingDocument21 pagesLecture 1.4 Design Vs Design Thinkingyann olivierNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking PDFDocument20 pagesDesign Thinking PDFuhauNo ratings yet

- Socially Responsive DesignDocument8 pagesSocially Responsive DesignJann Marc MandacNo ratings yet

- Redirective Practice: An Elaboration: Design Philosophy PapersDocument17 pagesRedirective Practice: An Elaboration: Design Philosophy PapersfwhiteheadNo ratings yet

- Desarrollos en DiseñoDocument10 pagesDesarrollos en DiseñosrmalverdeNo ratings yet

- What Is Human Centred DesignDocument14 pagesWhat Is Human Centred DesignBenNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Framwork For Workshop On DefiningDocument4 pages2011 - Framwork For Workshop On Definingpa JamalNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking - LietkaDocument7 pagesDesign Thinking - LietkaDung MaiNo ratings yet

- Notes - Module 1-1 - 230210 - 161929Document98 pagesNotes - Module 1-1 - 230210 - 161929roopaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Design ThinkingDocument4 pagesChapter 3 Design ThinkingkcamillebautistaNo ratings yet

- Design Competencies: Openness Empathy Courage Discipline Focus CuriosityDocument5 pagesDesign Competencies: Openness Empathy Courage Discipline Focus CuriosityDreamIn Initiative100% (1)

- Design Thinking in EducationDocument17 pagesDesign Thinking in EducationOffc Montage100% (1)

- REDSTRÖM, Johan. Towards User Design - On The Shift From Object To User As The Subject of Design. DesignDocument17 pagesREDSTRÖM, Johan. Towards User Design - On The Shift From Object To User As The Subject of Design. DesignrodrigonajarNo ratings yet

- Welcome: 3 Value-Driven InnovationDocument15 pagesWelcome: 3 Value-Driven InnovationDotta SaraNo ratings yet

- STR Ategy: Rachel Cooper, Professor, Lancaster UniversityDocument10 pagesSTR Ategy: Rachel Cooper, Professor, Lancaster UniversityMayara Atherino MacedoNo ratings yet

- Modul English For Design 1 (TM2) Principles of DesignDocument13 pagesModul English For Design 1 (TM2) Principles of DesignBernad OrlandoNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Idea Generation Using Design HeuristicsDocument11 pagesCollaborative Idea Generation Using Design HeuristicsSupradip DasNo ratings yet

- Deloitte CN MMP Pre Reading Design Thinking Participant Fy19 en 181106Document22 pagesDeloitte CN MMP Pre Reading Design Thinking Participant Fy19 en 181106Mohamed Ahmed RammadanNo ratings yet

- Empathy On The Edge PDFDocument14 pagesEmpathy On The Edge PDFibrar kaifNo ratings yet

- 1BIL-01Full-04Cruickshank Et AlDocument11 pages1BIL-01Full-04Cruickshank Et Aljanaina0damascenoNo ratings yet

- M1P2Document69 pagesM1P2Rakesh LodhiNo ratings yet

- Beyond Design Ethnography How DesignersDocument139 pagesBeyond Design Ethnography How DesignersAna InésNo ratings yet

- Loewe d4pv2 092719Document24 pagesLoewe d4pv2 092719Reham AbdelRaheemNo ratings yet

- 2018 AIEDAM Vasconcelos PDFDocument13 pages2018 AIEDAM Vasconcelos PDFLuiz FilhoNo ratings yet

- Design and RehabDocument36 pagesDesign and RehabBala KsNo ratings yet

- Pourdehnad IdealizedDesignDocument32 pagesPourdehnad IdealizedDesignRutvik GohilNo ratings yet

- Living The Co Design LabDocument10 pagesLiving The Co Design Labmariana henteaNo ratings yet

- Hci 102 Chapter 1Document4 pagesHci 102 Chapter 1Fherry AlarcioNo ratings yet

- Mattelmaki - Lost in Cox - Fin 1Document12 pagesMattelmaki - Lost in Cox - Fin 1michelleNo ratings yet

- BJOGVINSSON Et AlDocument19 pagesBJOGVINSSON Et AlPri PenhaNo ratings yet

- Lecture2 Design PhilosophyDocument30 pagesLecture2 Design PhilosophyENOCK MONGARENo ratings yet

- Nothings Gonna Change My Love For YouDocument45 pagesNothings Gonna Change My Love For YouKezia Sarah AbednegoNo ratings yet

- Design ThinkingDocument9 pagesDesign ThinkingJEMBERL CLAVERIANo ratings yet

- Human Centered-DesignDocument6 pagesHuman Centered-DesignLovenia M. FerrerNo ratings yet

- The Core of Design Thinking' and Its Application: Rowe, 1987Document12 pagesThe Core of Design Thinking' and Its Application: Rowe, 1987janne nadyaNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint: Design Research: A Revolution-Waiting-To-HappenDocument8 pagesViewpoint: Design Research: A Revolution-Waiting-To-HappenTamires BernoNo ratings yet

- 1 Design-for-an-Unknown-FutureDocument14 pages1 Design-for-an-Unknown-FutureVeridiana SonegoNo ratings yet

- The Little Booklet on Design Thinking: An IntroductionFrom EverandThe Little Booklet on Design Thinking: An IntroductionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Notes On Design and Science in The HCI CommunityDocument17 pagesNotes On Design and Science in The HCI CommunitySara de SáNo ratings yet

- Design Is A Verb Design Is A NounDocument14 pagesDesign Is A Verb Design Is A NounSara de SáNo ratings yet

- The Emerging Nature of PsychologyDocument42 pagesThe Emerging Nature of PsychologySara de SáNo ratings yet

- On The Word Design An Etymological EssayDocument5 pagesOn The Word Design An Etymological EssaySara de Sá100% (1)

- Reliable and Cost-Effective Sump Pumping With Sulzer's EjectorDocument2 pagesReliable and Cost-Effective Sump Pumping With Sulzer's EjectorDavid Bottassi PariserNo ratings yet

- BakerHughes BruceWright NewCokerDefoamer CokingCom May2011Document9 pagesBakerHughes BruceWright NewCokerDefoamer CokingCom May2011Anonymous UoHUagNo ratings yet

- 29 Modeling FRP-confined RC Columns Using SAP2000 PDFDocument20 pages29 Modeling FRP-confined RC Columns Using SAP2000 PDFAbdul LatifNo ratings yet

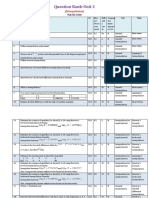

- Question Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300Document8 pagesQuestion Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300ROHAN TRIVEDI 20SCSE1180013No ratings yet

- Optimal Solution Using MODI - MailDocument17 pagesOptimal Solution Using MODI - MailIshita RaiNo ratings yet

- Living Sexy With Allana Pratt (Episode 29) Wired For Success TVDocument24 pagesLiving Sexy With Allana Pratt (Episode 29) Wired For Success TVwiredforsuccesstvNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Journal of King Saud University - ScienceDocument8 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Journal of King Saud University - ScienceFajar HutagalungNo ratings yet

- 2100-In040 - En-P HANDLING INSTRUCTIONSDocument12 pages2100-In040 - En-P HANDLING INSTRUCTIONSJosue Emmanuel Rodriguez SanchezNo ratings yet

- Soda AshDocument2 pagesSoda AshswNo ratings yet

- Butterfly Richness of Rammohan College, Kolkata, India An Approach Towards Environmental AuditDocument10 pagesButterfly Richness of Rammohan College, Kolkata, India An Approach Towards Environmental AuditIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesGraphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson Planapi-401400552100% (1)

- Ethyl BenzeneDocument10 pagesEthyl Benzenenmmpnmmpnmmp80% (5)

- ENGLISH G10 Q1 Module4Document23 pagesENGLISH G10 Q1 Module4jhon sanchez100% (1)

- Healing Sound - Contemporary Methods For Tibetan Singing BowlsDocument18 pagesHealing Sound - Contemporary Methods For Tibetan Singing Bowlsjaufrerudel0% (1)

- Care of Mother, Child, Adolescent, Well ClientsDocument3 pagesCare of Mother, Child, Adolescent, Well ClientsLance CornistaNo ratings yet

- JUNE 2003 CAPE Pure Mathematics U1 P1Document5 pagesJUNE 2003 CAPE Pure Mathematics U1 P1essasam12No ratings yet

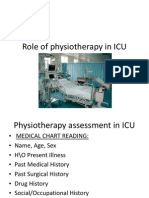

- Role of Physiotherapy in ICUDocument68 pagesRole of Physiotherapy in ICUprasanna3k100% (2)

- Microprocessor Engine/Generator Controller: Model MEC 2Document12 pagesMicroprocessor Engine/Generator Controller: Model MEC 2Andres Huertas100% (1)

- MenevitDocument6 pagesMenevitjalutukNo ratings yet

- Full Download Origami Tanteidan Convention 26 26Th Edition Joas Online Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesFull Download Origami Tanteidan Convention 26 26Th Edition Joas Online Full Chapter PDFmerissajenniea551100% (6)

- AP300Document2 pagesAP300Wislan LopesNo ratings yet

- Anger ManagementDocument18 pagesAnger Managementparag narkhedeNo ratings yet

- Method Statement CMC HotakenaDocument7 pagesMethod Statement CMC HotakenaroshanNo ratings yet

- BS en 13230 Part 2-2016Document30 pagesBS en 13230 Part 2-2016jasonNo ratings yet

- Seed MoneyDocument8 pagesSeed MoneySirIsaacs Gh100% (1)

- PHD ThesisDocument232 pagesPHD Thesiskafle_yrs100% (1)

- Scientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDocument6 pagesScientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDaniel VasquezNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentoolyrocksNo ratings yet

- The Real Green Revolution Organic and Agroecological FarmingDocument151 pagesThe Real Green Revolution Organic and Agroecological FarmingKlausEllegaard11No ratings yet

R59 Designing For Profound Experiences

R59 Designing For Profound Experiences

Uploaded by

Sara de SáOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

R59 Designing For Profound Experiences

R59 Designing For Profound Experiences

Uploaded by

Sara de SáCopyright:

Available Formats

Designing for Profound Experiences

Jesper L. Jensen

A Shift from Designing Solutions to Designing Possibilities

Design is generally considered a problem solving activity,1 just

as identifying problems and exploring possible solutions are the

basics of what we typically mean by design thinking.

Although the use of ethnographic methods (e.g., observing

and interviewing people in their natural habitat) has become

widely established in design,2 we are still searching for problems

rather than possibilities. Shedroff notes that designers “regularly

do themselves (and their intended audience) a disservice by not

addressing the full spectrum of experience when designing solu-

tions. Experiences (and, by default, products, services, events, etc.)

are much richer than most design processes reflect.”3

This observation implies the need for methods that

better enable designers to engage with the full richness of an expe-

rience. Desmet and Hassenzahl suggest an interesting turn in the

approach to design: It needs to go from solving problems, they say,

to exploring possibilities—ultimately creating design for a good

1 Norbert F. M. Roosenburg and Johannes

Eekels, Product Design: Fundamentals

and pleasurable life.4 The issue they see with the problem-driven

and Methods (New York: John Wiley approach is that it “focuses on ‘curing diseases’—that is, removing

& Sons, 1995); and Roger L. Martin, prevailing problems, instead of directly focusing on what makes

The Opposable Mind (Boston: Harvard us happy.”5 Some might argue that “making people happy” sounds

Business School Press, 2007).

like a shallow goal for design, but finding a more profound way

2 Jane F. Suri, “Poetic Observation:

to articulate design for possibilities might also lead to a more

What Designers Make of What They

See,” in Design Anthropology: Object substantial and lasting effect on efforts to meet the basic needs of

Culture in the 21st Century, ed. Alison J. the world, for example, food, water, shelter, and health care.

Clarke (Vienna: Springer, 2011), 16-32. This possibility-driven approach starts—and ends—with

3 Nathan Shedroff, “Research Methods human experiences. What really affects us and gives meaning

for Designing Effective Experiences,”

to life are the experiences we have. Such experiences don’t neces-

in Design Research: Methods and

Perspectives, First Edition, ed. Brenda

sarily involve the extraordinary: selling the house, buying a

Laurel (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, boat, and sailing around the world. Instead, design that affects

2003), 163. human experience is design that considers all experiences in

4 Pieter Desmet and Marc Hassenzahl, life and that makes our everyday experiences more meaningful.

“Towards Happiness: Possibility-Driven

Every product, service, and system we design affects our experi-

Design,” in Human-Computer Interaction:

ences, so I argue that what we design should be more profoundly

The Agency Perspective, ed. Marielba

Zacarias and José V. Oliveira (Berlin: grounded in the intended experiential outcome. Experience-based

Springer, 2012), 3-27.

5 Ibid., 2.

© 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00277 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 39

Designing (XbD) focuses intensely on such groundedness. XbD

can lead to new opportunities to design for experiences at a more

profound level, which can also lead to an exploration of possibili-

ties, rather than a focus on mere problem solving. Meanwhile, this

more profound way of looking at experiences can offer new ways

to consider issues where the problem-solving approach has not

proven successful.

XbD and the Effect on Human Lives

When designers start looking for the profound aspects of an expe-

rience, they can start designing in ways that more profoundly

affect human lives. Once we start seeing a lived experience in its

entirety, opportunities for new “products” often appear. Hassen-

zahl says that: “We should definitely shift attention (and resources)

from the development of new technologies to the conscious design

of resulting experiences, from technology-driven innovations to

human-driven innovations.”6 In this regard, human-driven innova-

tions are more than what user-centered design methods have

usually been able to offer. The incremental innovations in which

many user-centric methods often result have also been their main

cause of criticism.7 The problem with user-centered design is that

it often leads to a distinct product focus and to the creation of

solutions for the problems at hand. Considering the profound

experience instead of the use-experience might eliminate the incre-

mentalism and allow designers to do things completely differently.

To illustrate, suggesting height-adjustable chairs for workers

makes little sense if their experience would be markedly improved

by not sitting at all.

6 Marc Hassenzahl, “User Experience and

Experience Design,” in Encyclopedia of

The Broader Perspective of XbD

Human-Computer Interaction, Second

From a systemic perspective, products (and experiences) are

Edition, ed. Mads Soegaard and Rikke F.

Dam (Aarhus, Denmark: The Interaction integrated entities in the complex systems that make up peoples’

Design Foundation, 2013), 10. www.inter- lives.8 These systems are basically created by the offerings that are

action-design.org/encyclopedia/user_ made available through innovations, but it works the other way

experience_and_experience_design.html around as well. Referring to Denning and Dunham innovation

(accessed October 9, 2012).

can be considered “new practice adopted by a community.”9 Thus,

7 Lyle Kantrovich, “To Innovate or Not to

Innovate...” in Interactions 11, no. 1

successful innovation (e.g., of products or services) is not just

(2004): 24-31. something that is offered to people; it has to be adopted by them.

8 Harold G. Nelson and Erik Stolterman, The process of adoption is aided by the meaningfulness that a

The Design Way: Intentional Change in product offers its user. This is where XbD can be beneficial in

an Unpredictable World, Second Edition.

offering ways of giving the product the best possible chance of

(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2012);

being adopted into the lives of users in meaningful ways—in ways

and Peter Checkland, “Soft Systems

Methodology: a Thirty Year Retrospec- that reach beyond initial attraction. This longer term view is vital

tive,” Systems Research and Behavioral when considering customer relationships and the need for firms to

Science (SRBS) 17 (2000): 11–58. have loyal customers over the long haul. “Firms can no longer

9 Peter J. Denning and Robert D. Dunham, compete solely on providing superior value through their core

Innovator’s Way: Essential Practices

for Successful Innovation (MA: The MIT

Press, 2010), xv.

40 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

products; rather, they must move into the realm of customer expe-

rience management, creating long-term, emotional bonds with

their customers through the co-creation of memorable experiences,

potentially involving a constellation of goods and services.”10

Studies have shown that product qualities that make initial

experiences satisfying do not necessarily motivate prolonged use.

“Participants were found to develop an emotional attachment to

the product as they increasingly incorporated it in their daily

life… The iPhone is a very personal product as it connects users to

loved persons, allows adaptation to personal preferences, and is

always nearby.”11 Motivating prolonged use again affects society as

a whole; what happens, for example, when increased meaningful-

ness of products prolongs their use, potentially leading to reduced

consumption? Or when people find new ways of improving their

lives because products inspire them towards meaningful pur-

poses, potentially aiding people to achieve greater fulfillment? In

this way an increased focus on meaningfulness through design

can have a profound impact on peoples’ lives—not only at a per-

sonal level, but also at a societal level.

The Three Dimensions of an Experience

We can make a distinction between three dimensions that combine

to form the totality of an experience. These dimensions include the

tangible (instrumental dimension), the flow/actions (usage dimen-

sion), and the meaning (profound dimension). Heidegger’s use of

two terms helps with this distinction: “ready-at-hand” refers to

when the product becomes an extension of the person and the per-

son unconsciously acts through it, and “present-at-hand” is when

the object draws the attention of the user (e.g., the moment when

10 Mary J. Bitner, Amy L. Ostrom and

the brakes on a bike start squeaking). His distinction is also

Felicia N. Morgan, “Service Blueprinting:

descriptive of the two abstract dimensions of an experience: the

A Practical Technique for Service

Innovation,” California Management usage dimension (Heidegger’s “present-at-hand”) and the pro-

Review (2008): 67. found dimension (Heidegger’s “ready-at-hand”). Forlizzi and Bat-

11 Evangelos Karapanos, John Zimmerman, tarbee write that “understanding user experience—how people

Jodi Forlizzi and Jean-Bernard Martens, interact with products, other people, and the resulting emotions

“User Experience Over Time: An Initial

and experiences that unfold—will result in products and systems

Framework,” in Proceedings of the 27th

international Conference on Human that improve the lives of those who use them.”12

Factors in Computing Systems (New York, But reaching an understanding of the “resulting emotions

NY: ACM, 2009): 736. and experiences” needs a more profound focus than the use expe-

12 Jodi Forlizzi & Katja Battarbee, “Under- rience itself. Designing the use experience (usage dimension)

standing Experience in Interactive

potentially improves an interaction—and it might ensure that the

Systems,” in Proceedings of the 5th

user is happier with the product—but it will not necessarily

conference on Designing Interactive

Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, improve lives. Improving lives is not about increasing the experi-

and Techniques (NY: ACM, 2004): 266. ential stimuli;13 rather, it is about ensuring that the experience is

13 Steve Diller, Nathan Shedroff & Darrel profoundly meaningful. Thus, I suggest a distinction between the

Rhea, Making Meaning: How Successful usage dimension and the profound dimension, arguing that they

Businesses Deliver Meaningful Customer

have different characteristics and need to be developed from dif-

Experiences (Berkely, CA: New Riders

Press, 2005). ferent approaches (see Figure 1).

DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 41

Figure 1

The three dimensions of an experience

exemplified by a French Press Coffee Maker.

Hassenzahl suggests a similar division, describing three levels to

consider in design: why, what, and how.14 These levels fit the

notion of experience dimensions previously discussed. Consider

the experience of making coffee using a French press coffee maker.

The profound dimension is different than using an ordinary coffee

maker: It adds a café-like atmosphere and the sense that you can

take the time to just enjoy the moment. This meaning is supported

by t h e u s ag e d i m e n s io n t h r o ug h t h e c e r e mo n i a l ac t

of pouring hot water over the beans, enjoying the aroma, and

then gently pressing down the lid to complete the ritual. The

instrumental dimension is the physical product itself, which

allows for these interactions and resulting experience to happen.

The following section examines each of the three dimensions.

First Dimension: Instrumental

This dimension is concerned with the product that facilitates

the other dimensions. It is a tangible, often physical artifact. It can

be a product, the physical setup of a service, the scenography of

a movie. In defining the difference between products and services,

Shostack says that “products are tangible objects that exist in both

time and space; services consist solely of acts or process(es), and

exist in time only.”15 Her distinction is relevant to the differences

between the instrumental and usage dimensions, but services also

need an instrumental dimension, just as products potentially

generate a usage dimension. Buxton, for example, describes a posi-

14 Marc Hassenzahl, “User Experience and

tive use experience he had with a new orange squeezer that had

Experience Design,” in Encyclopedia of

Human-Computer Interaction, Second more emotional appeal than his old one, which he believes is due

Edition, ed. Mads Soegaard and Rikke F. to the aesthetics of motion as well as vision.16 He notes that it has to

Dam (Aarhus, Denmark: The Interaction do with the particular feel of the action when pulling the lever

Design Foundation, 2013), www.interac- down, such as qualities that come from the instrumental dimen-

tion-design.org/encyclopedia/user_expe-

sion and add value to his usage dimension.

rience_and_experience_design.html

(accessed October 9, 2012).

15 Lynn Shostack, “How to Design a Second Dimension: Usage

Service,” in European Journal of Market- A usage dimension has many similarities to service design.

ing 16 (1982): 49-63. When designing for the usage dimension, designers do not see

16 Bill Buxton, Sketching User Experiences: the product as the final outcome; instead, the experience a person

Getting the Design Right and the Right

has when using the product is the final outcome. In the same way,

Design (Burlington, MA: Morgan

Kaufmann, 2007): 129. service design moves beyond the physical setup of the service to

42 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

the orchestrated sequence consisting of several touchpoints, which

has similarities to the setup of a theatrical performance.17 Pinhanez

describes a service as a production, identifying two important

elements for something to be considered a service:

1. The user does not control the means of production. It is

generally “owned” and controlled by someone else.

2. The user is a significant part of the input to the produc-

tion process.18

So the difference between a service and the usage dimension of a

product is basically about ownership. A product is owned by the

user and comes with a latent “do-it-yourself” experience, whereas

the service setup requires that the service provider ensure the

experience is enabled.

Morelli describes services as “a series of events distributed

in time, in which users are supposed to interact with a prede-

signed set of elements.”19 When Hassenzahl describes an experi-

ence as “a story, emerging from the dialogue of a person with her

or his world through action,”20 the resemblance is evident. The per-

son engages with some sort of instrumental representation

through specific actions during the course of time.

Usage dimensions are building blocks for the profound

17 Birgit Mager and Shelley Evenson, “Art dimension, even though when users become fully immersed in the

of Service: Drawing the Arts to Inform

experience, they likely become unaware of the products and

Service Design and Specification,” in

actions that enable us to have that experience.

Service Science, Management and Engi-

neering: Education for the 21st Century, Forlizzi and Battarbee describe three categories of use-expe-

ed. Bill Hefley and Wendy Murphy (New riences.21 The first category is smooth and termed fluent; the second

York, NY: Springer, 2008). is less smooth and termed cognitive. The fluent experience is the

18 Claudio Pinhanez, “A Services Theory most automatic and well-learned one, whereas the cognitive

Approach to Online Services Applica-

requires that the user focus on the product at hand. Thus, fluent

tions,” in Proceedings of SCC ‘07 (IEEE

International Conference on Services

experience would be enabled by the well-designed product that

Computing, 2007): 3. allows you to immerse yourself in the experience, where cognitive

19 Nicola Morelli, “Designing Product/ use experience arises when you encounter something unfamiliar,

Service Systems: A Methodological or when the product acts up in a way that you didn’t expect, so it

Exploration,” in Design Issues 18, No. 3

demands your attention. (The latter explains why we design prod-

(Summer 2002): 11.

ucts to be as intuitively understood as possible.) Their third cate-

20 Marc Hassenzahl, Experience Design:

Technology for All the Right Reasons (San gory is called expressive experiences. This category seems of less

Francisco, CA: Morgan and Claypool importance, and I would question its relevance or value in this

Publishers, 2010): 8. concern. In such experiences, users “change, modify, or personal-

21 Jodi Forlizzi and Katja Battarbee, “Under- ize” the product.22 But modifying a product (e.g., when a user uses

standing Experience in Interactive

scissors to change the length of her shorts) is a use experience

Systems,” in Proceedings of the 5th

Conference on Designing Interactive

between the user and the scissors, not between the user and the

Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, shorts.

and Techniques (New York, NY: ACM, Use experience from an industrial design perspective

2004): 261-68. tends to focus on the physical aspects of the human-product inter-

22 Ibid., 262.

action. For example, the focus would be on how something would

23 Salu P. Ylirisku and Jacob Buur, Designing

work for a person in a wheelchair.23 The focus on physical aspects

with Video: Focusing the User-centred

Design Process (London: Springer, 2007).

DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 43

is typically seen in approaches such as user-centered design, par-

ticipatory design, and usability. This physical focus often leads to

removing as many challenges as possible. Forlizzi and Battarbee

suggest that “users need to attain fluency with the product early

on, to ensure that they will continue to use the product and not

abandon it in frustration.”24 Challenges, even when they lead to

frustration, can be a positive thing. But I argue that to do so, they

must come from the profound dimension, rather than from trouble

with the product. As Lazzaro notes, “[c]urrent usability methods

(increasing efficiency, effectiveness, and satisfaction), mostly

remove frustration points; they do not yet include techniques to

measure and craft other emotions. To exaggerate, a 100% usable

product would be boring once it eliminates all the challenges.”25

In the Snackbot project, Lee et al. found that “people mainly

choose convenience over snack quality, but they do not mind walk-

ing for a snack if social interaction is part of the activity.”26 Never-

theless, they developed a robot that delivers snacks to people with

focus on the usage dimension. In this case, they might have taken

a step back and started by exploring the profound dimension, fully

taking into account that getting a snack can be meaningful

because it is an experience that affords social interaction. Only by

considering the profound dimension can designers decrease the

risk of creating products that conflict with what is meaningful

about the experience.

Third Dimension: Profound Experience

Imagine riding your bike on a beautiful road. You hear the birds

singing, see the trees and meadows passing by, and feel the subtle

24 Jodi Forlizzi and Katja Battarbee, bumps in the road. You forget all about pedaling. At least that’s

“Understanding Experience in Interactive

what you do if the usage dimension is well designed, so that the

Systems,” in Proceedings of the 5th

Conference on Designing Interactive

smooth and natural interaction allows you to forget all about the

Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, product and just “enjoy the experience.” That’s when you become

and Techniques (New York: ACM, fully immersed—and that’s the profound dimension, the one in

2004): 265. which we find meaning. Designing for the profound dimension

25 Nicole Lazzaro, “Why We Play: Affect

considers the deeper levels of how products influence the lives of

and the Fun of Games—Designing

people. Products exist in an ecology of things that fit together to

Emotions for Games, Entertainment

Interfaces, and Interactive Products,” in give each other meaning and purpose. A pen, for example,

Human-Computer Interaction Handbook: becomes a pen when I have paper to write on, but it might have

Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies, been a stirrer if I had used it to stir my coffee. In a profound

and Emerging Applications, Third Edition dimension, things become transparent in use—for example, when

(Human Factors and ergonomics), ed.

you don’t think about pushing the light switch but only that you

Julie A. Jacko (Boca Raton, FL: Taylor

& Francis Group, LLC, 2012), 726.

want to turn on the light. This example illustrates the difference

26 Min Kyung Lee, Jodi Forlizzi, Paul Rybski, between using and doing. When Nike uses the trademark “JUST

Frederick L. Crabbe, Wayne C. Chung, DO IT”, the message is that the product is less important; what

Josh Finkle, Erik Glaser and Sara Kiesler, you do with it is more so. At the same time, the words imply that

“The Snackbot: Documenting the Design

the product enables you to have the profound experience you are

of a Robot for Long-term Human-Robot

looking for.

Interaction,” in Human-Robot Interaction

(ACM, 2009), 7-14.

44 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

27 Methodology is used here as being the So the profound dimension is about meaning at a deeper

“philosophic framework, the fundamental level–the meaning we find when we become fully immersed in the

assumptions and characteristics of a experience. Time is less of a factor than it is in the usage dimen-

human perspective” following van

sion, exemplified by how immersion is often referred to as “being

Manen. Max van Manen, Researching

Lived Experience: Human Science for an in the moment.” So the profound dimension can be considered a

Action Sensitive Pedagogy (Albany, NY: higher level offering of meaning in that particular moment; the

State University of New York Press, usage dimension and instrumental dimension are the means to

1990), 27. achieve it.

28 Conceptual models depict a situation by

exploring which concepts and tasks it

contains and the flow/sequence by which Toward a Methodology of Understanding and Designing (for)

they are connected. Austin Henderson Profound Experiences

and Jeff Johnson, Conceptual Models: The clear distinctions between usage dimension and profound

Core to Good Design (San Rafael, CA: dimension lead me to suggest that different methodologies are

Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2011).

needed for each.27 I see six important characteristics for profound

29 Service blueprinting are graphic illustra-

tions that depict a predefined sequence, dimension methodologies.

trying to imagine the “journey” people First, most methods used in service design and experience

will take. Susan L. Spraragen and Carrie design (e.g., conceptual models,28 service blueprinting,29 experience

Chan, “Service Blueprinting: When

models,30 or taxonomies 31) tend to focus on flow and timed se-

Customer Satisfaction Numbers are not

enough” (International DMI Education

quences; a profound dimension has less focus on temporal parameters.

Conference, 2008). Second, note that the service and experience methods listed

30 Experience models are representations typically work at task level and are therefore more closely related

of how experience is framed for the user to the usage dimension than the profound dimension. They typi-

and are beneficial to distil the important

cally focus on how the relationship—between a product and

aspects of behavior in a simple form

that aids the development of concepts,

user—evolves; the timeline of the use experience (or service) as

prioritizing and evaluating design direc- journey maps; or the relations between objects and actors that

tions, and acts as a shared reference influence the experience.32 They are very beneficial in designing

tool. Rachel Jones, “Experience Models: for the usage dimension, but they don’t explain why beautiful (or

Where Ethnography and Design Meet,”

horrifying) scenery is an important part of the experience of a

in Ethnographic Praxis in Industry

Conference Proceedings (EPIC, 2006), computer game, for example. So the profound methods need to

82–93; Maria Bezaitis and Rick focus on meaning structures, even before setting out an intended

Robinson, “Valuable to Values: How usage dimension. These meaning structures are to be found in per-

‘User Research’ Ought to Change,” in sonal, lived experiences. That experiences are subjective is com-

Design Anthropology: Object Culture in

monly accepted, 33 so we cannot design an experience in all its

the 21st Century, ed. Alison J. Clarke

(Vienna: Springer, 2011), 184-201. details and emotional effects, but we can design for an experience.

31 Taxonomies are models created by The personal experience (and the subjective meaning each person

deconstructing a situation into compo- finds in it) will then be shaped when the person undergoes the

nent parts and analyzing its aspects, to

experience, and will be different for each person. As Dourish sug-

flush out a more complete understanding

gests, “users, not designers, create and communicate meaning.”34

of the experience. Nathan Shedroff,

“Research Methods for Designing Effec- Meaning is often seen as something that enables happiness

tive Experiences,” in Design Research: and pleasure. Methods such as “happiness strategies” or “the four

Methods and Perspectives, ed. Brenda pleasures” focus on positive emotions as design goals. 35 These

Laurel (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press,

approaches can be fruitful in inspiring new ways of making emo-

2004), 155-63.

32 John Kolko, Exposing the Magic of

tional connections and creating new designs with an increased

Design: A Practitioner’s Guide to the emotional depth. But they have a tendency to encourage ad-hoc

Methods and Theory of Synthesis (New solutions that do not take into account the entire scope of the expe-

York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011); rience. Thus, they only solve particular issues of interest within an

Margaret Morris and Arnie Lund, “Experi-

ence Modeling: How are They Made and

What do They Offer?” in LOOP: AIGA

DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 45

Journal of Interaction Design Education experience instead of reaching a more complete understanding

(AIGA, 2001): 14. IDEO, Human Centered of it. Thus, the third characteristic of the methodology sought is

Design Toolkit: an Innovation Guide for that it should encompass the full scope of the experience.

Social Enterprises and NGO’s Worldwide

Fourth, the phenomenological tradition that Heidegger and

(IDEO, 2011). www.ideo.com/work/

human-centered-design-toolkit/ Husserl, among others, represent advocates looking at an experi-

(accessed October 9, 2012); Jeanette ence as the natural involvement in the real world as it unfolds.

Blomberg and Mark Burrell, “An Heidegger argues that obtaining insights from an experience

Ethnographic Approach to Design,” requires studying the concrete phenomena of daily life because

in The Human-computer Interaction

real meaning is found there. As Dourish describes it, such mean-

Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving

Technologies, and Emerging Applications, ing is “…not a collective of abstract, idealized entities; instead, it is

ed. Andrew Sears and Julie A. Jacko to be found in the world in which we act, and which acts upon

(New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum us.”36 The assumption that experiences are subjective, real-world

Associates, 2008): 965-88. phenomena suggests that a qualitative approach through dialogue with

33 See for instance: David Favrholdt, ed.,

a person is needed to obtain insights into the meaning contained

Æstetik og filosofi: seks essays 1,

[Aesthetics and Philosophy: Six Essays] in individual experience.37

(Copenhagen: Autumn & Sun, 2000). When Hassenzahl describes an experience as something

34 Paul Dourish, Where the Action Is: that transcends the material, 38 his sense of experience resembles

The Foundations of Embodied Interaction

what Heidegger described as being-in-the-world—in his language,

(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press,

2004): 170.

“dasein.” According to Dourish, dasein “…is embodied being; it

35 ‘Happiness strategies’ is a collection is not simply embedded in the world, but inseparable from it

of twelve strategies that are considered such that it makes no sense to talk of [being as] having an exis-

to generally make people happy. tence independent of that world.”39 He further says that “The

Examples of these are ‘practicing acts

embodied interaction perspective begins to illuminate not just how

of kindness’ and ‘avoiding over-thinking’.

Pieter Desmet & Marc Hassenzahl,

we act on technology but how we act through it. These understand-

“Towards Happiness: Possibility-Driven ings inform not just the analysis of existing technologies, but also

Design,” in Human-Computer Interaction: the development of future ones.”40 This leads to a fifth characteris-

The Agency Perspective, Marielba tic of profound experience methodologies: They enable immersion

Zacarias and José V. Oliveira eds.

into lived experiences.

(Berlin: Springer, 2012), 3-27. ‘The four

pleasures’ are: physical—stimulation Because this is a methodology for designing, it should also

of the five senses, social—pleasure lead toward a tangible outcome. It becomes a design process only

through social interaction, psychological when something is created and a situation has been influenced.

—stimulation of thinking and the (Design is a mediation.) So a methodology should not only act as a

pleasure of winning, and ideological—

perspective by which designers can interpret the world, but also

pleasure related to values and belief.

Patrick W. Jordan, ed., Designing show how they might do something with such insights. As Suri

Pleasurable Products: An Introduction to describes it, “designers need to interpret what they see (and other-

the New Human Factors 1 (Boca Raton, wise sense) in ways that will lead to design outcomes.”41 Models

FL: CRC Press, 2002).

and frameworks can in this situation act as lenses through which

36 Ibid., 116.

we are able to look at and, to some degree, acquire an understand-

37 Peter Wright and John McCarthy,

Experience-Centered Design: Designers, ing of the particular experience.

Users, and Communities in Dialogue Trying to make simplified models of something as com-

(Morgan & Claypool, 2010). plex as real-world phenomena cannot be done without the

38 Marc Hassenzahl, “User Experience and

acknowledgement that such models are “embodying only pure

Experience Design,” in Encyclopedia of

Human-Computer Interaction, Second

ideas of purposeful activity rather than being descriptions of

Edition, Mads Soegaard and Rikke F. parts of the real world.”42 Still, such lightweight representations are

Dam, eds., (Aarhus, Denmark: The Inter- needed to translate the data into design—our sixth methodological

action Design Foundation, 2013), www. characteristic.

interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/

user_experience_and_experience_

design.html (accessed October 9, 2012).

46 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

Figure 2

Taking a closer look. One of the workers at

the CSSD is examining a surgical instrument

through a magnifying glass.

39 Paul Dourish, Where the Action Is: The To summarize, the following six identified characteristics describe

Foundations of Embodied Interaction a methodology of understanding and designing (for) profound experiences:

(Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press,

• deemphasize the focus on temporal parameters;

2004),110.

• focus on meaning structures;

40 Ibid., 154.

• encompass the full scope of the experience;

41 Jane F. Suri, “Poetic Observation: What

Designers Make of What They See,” in • encourage qualitative approaches through dialogue;

Design Anthropology: Object Culture in • enable immersion into lived experiences;

the 21st Century, Alison J. Clarke, ed., • translate into design with usable, lightweight

(Springer, 2011), 18.

representations.

42 Peter Checkland, “A Thirty Year Retro-

spective,” in Systems Research and

Behavioral Science (SRBS) (2000), 11-58. I began searching for a tool or method that would match the pro-

43 The CSSD is an integrated place in posed characteristics of the methodology as much as possible,

hospitals and other health care facilities starting by exploring meaning structures from lived experiences—

that processes cleaning and sterilization

and more precisely, from the experience of working at the Central

on medical devices, equipment, and

consumables.

Sterile Services Department (CSSD) of a Danish hospital.43 This

44 The CSSD project is concerned with search led to the development of the Experience Scope Framework,

developing and/or adopting technology which I describe in the following sections.

that improves the CSSD’s effectiveness.

My involvement in this project focused

A Search for Meaning Structures in Everyday Experiences

on the experiences the workers had

“I really enjoy the humorous tone we have amongst each

during their workday, trying to identify

the meaningful components of their other. There’s always someone to chat with. Of course, it

experiences—the goal being to ensure can also be too much sometimes. In doing tasks where I

that new concepts were created really have to concentrate, it’s better if there’s less talking.”

with sensitivity to how they affect

the human experience.

As part of the CSSD project,44 I interviewed workers—including

45 Eva Brandt and Jörn Messeter,

“Facilitating Collaboration through

the one just quoted—about their experiences at the workplace.

Design Games,” in Proceedings For the project, we applied different ethnographic methods, such

Participatory Design Conference as interviews, observations, and video-analysis, as well as exer-

(ACM, 2004). cises encouraging a freer dialogue and active engagement through

46 The term Omni-oriented refers to

design games.45 Such methods were used to gather data about

something universally oriented similarly

the meaningful aspects of the employees’ workday experiences

to how a deity can be considered

omnipresent (present in all places (see Figure 2).

at the same time) or something can be Key insights—exemplified by the quote—were extracted

omnidirectional. The two orientations from the data and structured in patterns. In structuring the

were first introduced at CHI ’12: Jesper insights, a distinct pattern emerged, showing that the experience

L. Jensen, “The Theory of Experience

Orientation” (paper presented at CHI ‘12,

The ACM Conference on Human Factors

DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 47

was meaningful in two general ways. One was the achievement of

a goal leading to a feeling of success or accomplishment (denoted

goal-oriented); the other was more about the atmosphere, including

chats and interactions with colleagues. Denoted omni-oriented, the

latter type of meaning is basically everything other than the goal-

in Computing Systems, Texas, 2012). oriented meaning;46 it describes a state in which people are open to

http://di.ncl.ac.uk/uxtheory/workshop- whatever happens—that is, they are oriented toward wherever

papers/ (accessed October 9, 2012).

something draws their attention.

47 Aristotle, The Nichomachean Ethics,

trans. Martin Oswald (New York: The

Bobs-Merrill Company, 1962 [Original Goal-Oriented and Omni-Oriented Analysis

work published 350BC]). These terms, Using the quote from the worker, the goal-oriented meaning

hedonism and eudaimonia, are consid- appears where she says she sometimes needs to close off commu-

ered to be too value-laden to be suitable nication with colleagues so that she can concentrate. Conversely,

as terms for this framework, and, more

the omni-oriented side shows that the communication with her

importantly, the aspect of orientation

needs to be amplified. So instead of colleagues is very important for her wellbeing. As simple as it

applying these terms to the framework, seems, dividing the experience along these two orientations was a

goal- and omni-orientation were significant development in trying to structure the data.

preferred as terms. The two orientations reflect the concepts of hedonism and

48 Serendipity is meant as the occurence

eudaimonia that Aristotle originally introduced.47 The goal-ori-

of “fortunate discoveries” in the sense of

ented side is directed toward a goal—what Aristotle called the

finding something you were not even

looking for. eudaimonic—and hence is very focused. In this type of experience,

49 Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The an occurrence that does not lead toward the goal is an obstruction.

Psychology of Optimal Experience (New The omni-oriented side is open to whatever might happen, which

York: Harper and Row, 1990). Flow refers would also allow for serendipity to occur as part of the experi-

to the feeling of accomplishment that can

ence.48 This side relates to Aristotle’s hedonism. So where one

be reached through the perfect balance

between challenge and skills. relates to achievement and positive challenges—also comparable

50 Rung-Huei Liang, “Designing for to what Csikszentmihalyi calls flow49—the other relates to seren-

Unexpected Encounters with Digital dipity. Liang has identified an “emerging need to articulate seren-

Products: Case Studies of Serendipity dipity as an experiential quality.”50 While always present in lived

as Felt Experience,” in International

experiences, serendipity has been widely overlooked in product

Journal of Design 6 (2012): 42.

design and interaction; its absence is particularly seen in the focus

51 Affordances are meant as the setup and

clues that are designed in order to ensure on usability and affordances,51 which are intended to ensure that

that a user would understand the use users act in a specified way. Although designers generally cannot

and purpose of something (introduced design for particular serendipitous things to happen (by the very

by Gibson as affordances). James J. nature of the concept), I would argue that an openness in and to

Gibson, “The Theory of Affordances,” in

the experience might enable serendipity to occur.

Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing, Robert

Shaw and John Bransford, eds., (Hills- The goal orientation and the omni orientation are co-depen-

dale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1977), dent, so a framework of experience needs to support the juxtaposi-

67-82. Boess & Kanis similarly provide a tion of elements that relate to both. Goal and omni orientations are

critique of the concepts of affordances seen as basic orientations, meaning that in combination they are

and semantics and propose a new

believed to expand the full scope of an experience, although one

concept (use cues) in order to direct the

of them typically is predominant at any point in time. However,

design research community’s attention

towards the serendipity that product use whether consciously or unconsciously, the switch between which

can introduce to design. Stella Boess and one is the predominant one can be very rapid. Suzanne Currie,

Heinrich Kanis, “Meaning in Product in Samsung’s User Experience Center America, discussed with

Use: A Design Perspective,” in Product me these two orientations and how they would be evident in,

Experience, Hendrik N. J. Schifferstein

for example, a library experience. In the goal-oriented state, you

and Paul Hekkert, eds., (Elsevier Science,

2008) 305-32.

48 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

would be searching for a specific book, but in the omni-oriented

state, you would just be browsing to see if something interesting

might pop up—a fascinating text or a serendipitous meeting with

an old friend. We also considered the switch from one orientation

to the other, seeing it as a key factor in an experience. This switch

from one orientation to the other deserves explicit attention.

Direct and Derived Effects

Another aspect that became evident in the empirical data from the

CSSD was the influence of the experience not only directly, but

also as derived effect. Direct effects deal with the situation at hand.

In goal orientation, the direct effect is about completing a task, and

in omni-orientation, it is about wellbeing. Derived effects reach

beyond the situation at hand. In goal orientation, the derived effect

could be about learning—not only in the sense of cumulative expe-

riences that improve your skills in the particular situation, but also

how it affects other situations. To illustrate, in the movie Karate

Kid, when Ralph Macchio is instructed to wax Mr. Miyagi’s car, the

derived goal-oriented aspect is about improving his karate skills.

A derived omni-oriented experience is one that connects to a per-

son’s values and personality, adding to his or her happiness. In the

CSSD project, such effects might be seen in how a pleasant atmo-

sphere at the workplace can enhance the workers’ general wellbe-

ing and how good conversations with colleagues can enhance the

sense of social belonging. In short the direct effect is about the here

and now, and the derived effect is about the then and there.

The Experience Scope Framework: A Tool for Mapping

Meaning Structures

The described empirical findings and theories provided the back-

ground for developing the Experience Scope Framework (ESF).

This framework for designing from the profound dimension is

depicted as a two-by-two matrix that juxtaposes omni-orientation

and goal-orientation along the one axis and direct and derived

effects along the other. Using the goal- and omni-orientations as a

basic concept for understanding the scope of an experience seems

beneficial because it leads to a fuller understanding of the mean-

ing structures, thus reducing the risk of jumping at ad hoc ideas

prematurely. The openness of the framework expands the capacity

to see what is actually “there,” gathering data from lived experi-

ences while making the meaning explicit, so that we don’t overlook

hidden but powerful and important aspects (see Figure 3).

The ESF is directly applicable in a design process, providing

a structured way to explore a broader scope of the experience at a

profound level. Making the orientations and effects of an experi-

ence more explicit—and working directly with the switch between

them—improves the potential to start designing at the level of the

profound dimension.

DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 49

Figure 3

Illustration of the ESF

(www.Experiencescope.net).

The Ifloor Project: Adding Richness to a Library Experience

In 2002–2004 the Ifloor project was conducted at the city library in

Aarhus, Denmark, as a design research study. It used an interac-

tive floor built in the main lobby. Visitors could send questions via

their mobile phones to a system that would project the questions

onto the floor. The movement of people was tracked with a camera

mounted in the ceiling. The system analyzed social interaction on

the floor, and visitors who wanted their question to be displayed

(the goal) had to talk to other visitors. The project was intended to

bring social interaction back to the library.52 By promoting random

encounters with other people, however, the design study simulta-

neously allowed for serendipity to play a role. It thereby triggered

the switch between the goal-oriented aspects (getting a question

displayed) and the omni-oriented aspects (the random conversa-

tions with others) and back. This study thus provided an enrich-

ing interplay between goal-orientation and omni-orientation that

added to the library experience.

Whereas Desmet and Hassenzahl suggest that two different

strategies must be used to design for either achievement or wellbe-

ing,53 I argue that exploring both in relation to each other is more

beneficial, as is considering the switch from one to the other. The

Ifloor project supports this argument and illustrates how using

52 Ilpo Koskinen, John Zimmerman, Thomas the ESF could lead to uncovering both goal-oriented aspects and

Binder, Johan Redstrom and Stephan

omni-oriented ones.

Wensveen, Design Research through

Practice: From the Lab, Field and Show-

room (Morgan Kaufmann, 2011). The Process of Designing for Profound Dimensions

53 Pieter Desmet and Marc Hassenzahl, Using the ESF

“Towards Happiness: Possibility-Driven During the CSSD project, I conducted an exercise with selected

Design,” in Human-Computer Interaction:

participants using the ESF to highlight meaningful aspects of the

The Agency Perspective, Marielba

workday experience. I chose to focus on the three quadrants other

Zacarias and José V. Oliveira, eds.,

(Springer, 2012). than the direct goal-oriented one because of time constraints and

50 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

Figure 4

This illustration shows the outcome of the

exercise conducted during the CSSD-project.

The ESF was used to depict the meaning

structures in the experience of working at

the CSSD.

because the three had been neglected in the project thus far. The

exercise built on initial insights (found through earlier observa-

tions and interviews at the CSSD), and it used the ESF to structure

them. In some cases, the participants found it difficult to separate

the goal-oriented and omni-oriented aspects, which illustrate

how closely they are connected. For instance, you could argue that

solving a task would contribute to your wellbeing, just as

enhanced wellbeing might motivate you to solve the task. In some

cases an identified issue fits between two quadrants: For some, cre-

ating a clean and orderly environment not only helps in solving

the task at hand, but also makes being in the environment more

enjoyable (see Figure 4).

After the exercise I asked the participants whether they felt

that using the model provided insights they would not have had

otherwise.54 The following statements from the transcripts reveal

their responses:

• Participant 1: Usually you would have a tendency

to not think about the derived things when you are

working on a project.

• Participant 2: Yes, we are probably more direct.

• Participant 1: Yes, directly towards the direct

goal-oriented aspects.

• Participant 2: Yes, and then thinking about the other

things is implied.

• Participant 3: I think it’s an enormously interesting

process—educational—as a way to think out of the box.

You focus on something you normally wouldn’t focus

on at all.

• Participant 1: Yes, I’m feeling a bit narrow-minded when

I look at what we had actually neglected.

54 The participants were project leaders and • Participant 3: I think that in 98% of the work I usually

engineers with considerable experience

do, I would only be concerned with the quadrant we

from development projects similar to the

CSSD project. chose to skip.

DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014 51

Participant 2: Yes.

•

Participant 1: Yes. And I think there were some good dis-

•

cussions thinking about what kind of situation it actually

is—a recap of, and our view on, the actual situation.

This discussion highlights how using the ESF led the group to a

fuller understanding of the profound experience than they had

before the exercise. Thus, using the ESF is a way to form the basic

understanding of the experience we intend to design for, which

can then lead to idea generation that focuses on meaning struc-

tures in the profound dimension. During the steps of designing for

the usage dimension and the product (instrumental dimension),

the model can also be used as reference to ensure the design sup-

ports the intended profound experience.

Conclusion

The paper argues for recognition of three dimensions in designing

for experiences—instrumental, usage, and profound dimensions—

and focuses especially on some of the characteristics that a meth-

odology relating to the profound dimension might require. These

characteristics are fundamental in the development of a new meth-

odological framework—the ESF—introduced in the article. The

ESF is a valuable tool for identifying and visualizing the meaning

structures of an experience, leading to new design opportunities

not previously considered, as the exercise with CSSD project par-

ticipants showed. Describing the ESF here is not only meant as a

suggestion of a design tool, but is also intended to encourage fur-

ther discussion about how we might move closer to a methodology

of understanding and designing (for) profound experiences.

The intention behind this approach is to increase our under-

standing of lived human experiences brought about by experience-

based designing. Design that better recognizes and engages the

profound dimension can lead to products, systems, and services

that better support the experiences we would wish to have. I argue

that experiences should be at the root of designing and act as a

vital source of new possibilities, ensuring a human-centered

approach that makes technology work for people, and not the

other way around.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the practitioners and academics I have had the

opportunity to discuss the topic and article with, including my col-

leagues at the Experience-based Designing Center at the University

of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark. Their insightful com-

ments and reflections have helped to shape and refine the article.

The CSSD project was partially funded by the European

Fund for Regional Development.

52 DesignIssues: Volume 30, Number 3 Summer 2014

Copyright of Design Issues is the property of MIT Press and its content may not be copied or

emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Tutorial 6 AnswersDocument5 pagesTutorial 6 AnswersMaria MazurinaNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking For Startups - AntlerDocument36 pagesDesign Thinking For Startups - AntlerClarisse LamNo ratings yet

- vIXwe-J0W59C7PPe - XTWzq-BrhWkPAWVU-Desing ThinkingDocument11 pagesvIXwe-J0W59C7PPe - XTWzq-BrhWkPAWVU-Desing ThinkingLiz Soriano MogollónNo ratings yet

- Research in Design ThinkingDocument8 pagesResearch in Design ThinkingHasby Rahim Rahmatullah hasbyrahim.2020No ratings yet

- Can Design Thinking Still Add ValueDocument5 pagesCan Design Thinking Still Add Valuexiaonan luNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking ToolkitDocument28 pagesDesign Thinking ToolkitIoana Kardos100% (13)

- Design ThinkingDocument8 pagesDesign ThinkingSomeonealreadygotthatusername.No ratings yet

- Module - L6 (1) EntrepDocument3 pagesModule - L6 (1) EntrepDianne ObedozaNo ratings yet

- Design ThinkingDocument10 pagesDesign ThinkingSanjanaaNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking ProcessDocument15 pagesDesign Thinking ProcessSavitaNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument19 pagesArticlejelisacharles8No ratings yet

- Lecture 4 - Design ThinkingDocument43 pagesLecture 4 - Design ThinkingDannica Keyence MagnayeNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Design - Module 1Document11 pagesIntroduction To Design - Module 1Disha KaushalNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking An OverviewDocument8 pagesDesign Thinking An OverviewFlávio AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Productive Interaction: Designing For Drivers Instead of PassengersDocument19 pagesProductive Interaction: Designing For Drivers Instead of PassengersPhilip van AllenNo ratings yet

- Design 3.0 WassermannDocument10 pagesDesign 3.0 WassermannceleoramNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking: The Future of Business StrategyDocument19 pagesDesign Thinking: The Future of Business StrategyDameon GreenNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Human-Centered DesignDocument17 pagesAn Introduction To Human-Centered DesignMusse MulugetaNo ratings yet

- Psychology of DesignDocument18 pagesPsychology of Designsandra quinnNo ratings yet

- Questioning The Center of Human CenteredDocument9 pagesQuestioning The Center of Human CenteredakhmadNo ratings yet

- Gabriela Goldschmidt Anat Litan Sever - Inspiring Design Ideas With TextsDocument17 pagesGabriela Goldschmidt Anat Litan Sever - Inspiring Design Ideas With TextsOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking ProcessDocument14 pagesDesign Thinking ProcessPatrica LybbNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1.4 Design Vs Design ThinkingDocument21 pagesLecture 1.4 Design Vs Design Thinkingyann olivierNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking PDFDocument20 pagesDesign Thinking PDFuhauNo ratings yet

- Socially Responsive DesignDocument8 pagesSocially Responsive DesignJann Marc MandacNo ratings yet

- Redirective Practice: An Elaboration: Design Philosophy PapersDocument17 pagesRedirective Practice: An Elaboration: Design Philosophy PapersfwhiteheadNo ratings yet

- Desarrollos en DiseñoDocument10 pagesDesarrollos en DiseñosrmalverdeNo ratings yet

- What Is Human Centred DesignDocument14 pagesWhat Is Human Centred DesignBenNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Framwork For Workshop On DefiningDocument4 pages2011 - Framwork For Workshop On Definingpa JamalNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking - LietkaDocument7 pagesDesign Thinking - LietkaDung MaiNo ratings yet

- Notes - Module 1-1 - 230210 - 161929Document98 pagesNotes - Module 1-1 - 230210 - 161929roopaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Design ThinkingDocument4 pagesChapter 3 Design ThinkingkcamillebautistaNo ratings yet

- Design Competencies: Openness Empathy Courage Discipline Focus CuriosityDocument5 pagesDesign Competencies: Openness Empathy Courage Discipline Focus CuriosityDreamIn Initiative100% (1)

- Design Thinking in EducationDocument17 pagesDesign Thinking in EducationOffc Montage100% (1)

- REDSTRÖM, Johan. Towards User Design - On The Shift From Object To User As The Subject of Design. DesignDocument17 pagesREDSTRÖM, Johan. Towards User Design - On The Shift From Object To User As The Subject of Design. DesignrodrigonajarNo ratings yet

- Welcome: 3 Value-Driven InnovationDocument15 pagesWelcome: 3 Value-Driven InnovationDotta SaraNo ratings yet

- STR Ategy: Rachel Cooper, Professor, Lancaster UniversityDocument10 pagesSTR Ategy: Rachel Cooper, Professor, Lancaster UniversityMayara Atherino MacedoNo ratings yet

- Modul English For Design 1 (TM2) Principles of DesignDocument13 pagesModul English For Design 1 (TM2) Principles of DesignBernad OrlandoNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Idea Generation Using Design HeuristicsDocument11 pagesCollaborative Idea Generation Using Design HeuristicsSupradip DasNo ratings yet

- Deloitte CN MMP Pre Reading Design Thinking Participant Fy19 en 181106Document22 pagesDeloitte CN MMP Pre Reading Design Thinking Participant Fy19 en 181106Mohamed Ahmed RammadanNo ratings yet

- Empathy On The Edge PDFDocument14 pagesEmpathy On The Edge PDFibrar kaifNo ratings yet

- 1BIL-01Full-04Cruickshank Et AlDocument11 pages1BIL-01Full-04Cruickshank Et Aljanaina0damascenoNo ratings yet

- M1P2Document69 pagesM1P2Rakesh LodhiNo ratings yet

- Beyond Design Ethnography How DesignersDocument139 pagesBeyond Design Ethnography How DesignersAna InésNo ratings yet

- Loewe d4pv2 092719Document24 pagesLoewe d4pv2 092719Reham AbdelRaheemNo ratings yet

- 2018 AIEDAM Vasconcelos PDFDocument13 pages2018 AIEDAM Vasconcelos PDFLuiz FilhoNo ratings yet

- Design and RehabDocument36 pagesDesign and RehabBala KsNo ratings yet

- Pourdehnad IdealizedDesignDocument32 pagesPourdehnad IdealizedDesignRutvik GohilNo ratings yet

- Living The Co Design LabDocument10 pagesLiving The Co Design Labmariana henteaNo ratings yet

- Hci 102 Chapter 1Document4 pagesHci 102 Chapter 1Fherry AlarcioNo ratings yet

- Mattelmaki - Lost in Cox - Fin 1Document12 pagesMattelmaki - Lost in Cox - Fin 1michelleNo ratings yet

- BJOGVINSSON Et AlDocument19 pagesBJOGVINSSON Et AlPri PenhaNo ratings yet

- Lecture2 Design PhilosophyDocument30 pagesLecture2 Design PhilosophyENOCK MONGARENo ratings yet

- Nothings Gonna Change My Love For YouDocument45 pagesNothings Gonna Change My Love For YouKezia Sarah AbednegoNo ratings yet

- Design ThinkingDocument9 pagesDesign ThinkingJEMBERL CLAVERIANo ratings yet

- Human Centered-DesignDocument6 pagesHuman Centered-DesignLovenia M. FerrerNo ratings yet

- The Core of Design Thinking' and Its Application: Rowe, 1987Document12 pagesThe Core of Design Thinking' and Its Application: Rowe, 1987janne nadyaNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint: Design Research: A Revolution-Waiting-To-HappenDocument8 pagesViewpoint: Design Research: A Revolution-Waiting-To-HappenTamires BernoNo ratings yet

- 1 Design-for-an-Unknown-FutureDocument14 pages1 Design-for-an-Unknown-FutureVeridiana SonegoNo ratings yet

- The Little Booklet on Design Thinking: An IntroductionFrom EverandThe Little Booklet on Design Thinking: An IntroductionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Notes On Design and Science in The HCI CommunityDocument17 pagesNotes On Design and Science in The HCI CommunitySara de SáNo ratings yet

- Design Is A Verb Design Is A NounDocument14 pagesDesign Is A Verb Design Is A NounSara de SáNo ratings yet

- The Emerging Nature of PsychologyDocument42 pagesThe Emerging Nature of PsychologySara de SáNo ratings yet

- On The Word Design An Etymological EssayDocument5 pagesOn The Word Design An Etymological EssaySara de Sá100% (1)

- Reliable and Cost-Effective Sump Pumping With Sulzer's EjectorDocument2 pagesReliable and Cost-Effective Sump Pumping With Sulzer's EjectorDavid Bottassi PariserNo ratings yet

- BakerHughes BruceWright NewCokerDefoamer CokingCom May2011Document9 pagesBakerHughes BruceWright NewCokerDefoamer CokingCom May2011Anonymous UoHUagNo ratings yet

- 29 Modeling FRP-confined RC Columns Using SAP2000 PDFDocument20 pages29 Modeling FRP-confined RC Columns Using SAP2000 PDFAbdul LatifNo ratings yet

- Question Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300Document8 pagesQuestion Bank-Unit 2: MATH 2300ROHAN TRIVEDI 20SCSE1180013No ratings yet

- Optimal Solution Using MODI - MailDocument17 pagesOptimal Solution Using MODI - MailIshita RaiNo ratings yet

- Living Sexy With Allana Pratt (Episode 29) Wired For Success TVDocument24 pagesLiving Sexy With Allana Pratt (Episode 29) Wired For Success TVwiredforsuccesstvNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Journal of King Saud University - ScienceDocument8 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Journal of King Saud University - ScienceFajar HutagalungNo ratings yet

- 2100-In040 - En-P HANDLING INSTRUCTIONSDocument12 pages2100-In040 - En-P HANDLING INSTRUCTIONSJosue Emmanuel Rodriguez SanchezNo ratings yet

- Soda AshDocument2 pagesSoda AshswNo ratings yet

- Butterfly Richness of Rammohan College, Kolkata, India An Approach Towards Environmental AuditDocument10 pagesButterfly Richness of Rammohan College, Kolkata, India An Approach Towards Environmental AuditIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesGraphing Quadratic Functions in Standard Form Lesson Planapi-401400552100% (1)

- Ethyl BenzeneDocument10 pagesEthyl Benzenenmmpnmmpnmmp80% (5)

- ENGLISH G10 Q1 Module4Document23 pagesENGLISH G10 Q1 Module4jhon sanchez100% (1)

- Healing Sound - Contemporary Methods For Tibetan Singing BowlsDocument18 pagesHealing Sound - Contemporary Methods For Tibetan Singing Bowlsjaufrerudel0% (1)

- Care of Mother, Child, Adolescent, Well ClientsDocument3 pagesCare of Mother, Child, Adolescent, Well ClientsLance CornistaNo ratings yet

- JUNE 2003 CAPE Pure Mathematics U1 P1Document5 pagesJUNE 2003 CAPE Pure Mathematics U1 P1essasam12No ratings yet

- Role of Physiotherapy in ICUDocument68 pagesRole of Physiotherapy in ICUprasanna3k100% (2)

- Microprocessor Engine/Generator Controller: Model MEC 2Document12 pagesMicroprocessor Engine/Generator Controller: Model MEC 2Andres Huertas100% (1)

- MenevitDocument6 pagesMenevitjalutukNo ratings yet

- Full Download Origami Tanteidan Convention 26 26Th Edition Joas Online Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesFull Download Origami Tanteidan Convention 26 26Th Edition Joas Online Full Chapter PDFmerissajenniea551100% (6)

- AP300Document2 pagesAP300Wislan LopesNo ratings yet

- Anger ManagementDocument18 pagesAnger Managementparag narkhedeNo ratings yet

- Method Statement CMC HotakenaDocument7 pagesMethod Statement CMC HotakenaroshanNo ratings yet

- BS en 13230 Part 2-2016Document30 pagesBS en 13230 Part 2-2016jasonNo ratings yet

- Seed MoneyDocument8 pagesSeed MoneySirIsaacs Gh100% (1)

- PHD ThesisDocument232 pagesPHD Thesiskafle_yrs100% (1)

- Scientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDocument6 pagesScientific Revolution: Galileo Galilei - Italian Mathematician in University of PaduaDaniel VasquezNo ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentoolyrocksNo ratings yet

- The Real Green Revolution Organic and Agroecological FarmingDocument151 pagesThe Real Green Revolution Organic and Agroecological FarmingKlausEllegaard11No ratings yet