Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Notion in Motion Teachers Digital Competence

Notion in Motion Teachers Digital Competence

Uploaded by

courageantisatanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Notion in Motion Teachers Digital Competence

Notion in Motion Teachers Digital Competence

Uploaded by

courageantisatanCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/279556595

Notion in Motion: Teachers’ Digital Competence

Article in Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy · December 2014

DOI: 10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2014-04-05

CITATIONS READS

80 918

3 authors:

Monica Johannesen Leikny Øgrim

Oslo Metropolitan University Oslo Metropolitan University

26 PUBLICATIONS 335 CITATIONS 12 PUBLICATIONS 154 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Tonje Giaever

Oslo Metropolitan University

19 PUBLICATIONS 222 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Monica Johannesen on 15 September 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Notion in Motion:

Teachers’ Digital Competence

4

NORDIC JOURNAL OF

DIGITAL LITERACY

SPECIAL ISSUE 2014 Monica Johannesen

Professor, PhD, Faculty of Education and International Studies, Oslo and Akershus

9. ÅRGANG

University College, Norway

monica.johannesen@hioa.no

Leikny Øgrim

Professor, Doctor Scient., Faculty of Education and International Studies, Oslo and

© Universitetsforlaget Akershus University College, Norway

Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, leikny.ogrim@hioa.no

vol. 9, Nr. 4-2014 s. 300–312

ISSN Online: 1891-943X

Tonje Hilde Giæver

P E E R R E V I E W E D A R TI C L E Assistant Professor, Cand Scient., Faculty of Education and International Studies, Oslo and

Akershus University College, Norway

tonje.h.giaever@hioa.no

AB STRA CT

The aim of this article is to shed critical light on the prevailing understanding

of digital competence in schools and teacher education. There seems to be an

emphasis on how to practice teaching with ICT throughout the Norwegian

educational system. This article discusses and elaborates on the current

approach, and argues for understanding digital competence from a broader

perspective, by suggesting a framework for the notion of digital competence for

teachers. This approach stresses teaching of, about, and with ICT.

Keywords

digital competence, teacher training, teaching, ict

INTRODUCTION

In public debate the teacher’s supposed limited digital skills and practices are

often debated (Engen, Giæver, & Bjarnø, 2008; Ernes, 2008; Haugsbakk,

2010). Frequently the teachers are the ones targeted when schools do not meet

the expectations of national standards or international measures (Convery,

2009).

Teacher digital competence is a relative term with respect to time and context.

The current Norwegian curriculum is an essential part of this context and out-

lines what competence is considered relevant for the teacher. The Norwegian

school is, via the national curriculum (the Knowledge Promotion), obliged to

develop the digital skills that students need for educational and social life. This

is described in general terms in the introductory part of the national curriculum,

which states that school should develop broad competences for the students,

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

© UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET | NORDIC JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LITERACY | VOL 9 | NR 4-2014 301

including learning strategies, social competencies, and motivation for learning

student participation (Ministry of Education Research and Church Affairs,

2004). More specifically, the national curriculum defines the school’s

approach to and the actual use of digital tools, as well as the social and ethical

challenges technology brings about. It thus indirectly advises what kinds of

competence the teachers must have in order to facilitate student learning and

fulfil the intentions of the curriculum.

The current national curriculum focuses on digital skills to be integrated in

school to support subject learning. In order to fulfil these requirements, digital

competence among teachers is essential. Several researchers have defined

teachers’ digital competence (Krumsvik, 2009; Mishra & Koehler, 2006b;

Sabaliauskas, Bukantaitė, & Pukelis, 2006). Although, there is no unified

understanding of what this encompasses, most researchers focus on teachers’

competence in using digital tools to support student learning (i.e. teaching with

ICT). However, the digital competence that the Knowledge Promotion asks for

is more complex. There are competence areas in the Norwegian national cur-

riculum that aims at developing general digital competence among students,

such as becoming a digital citizen. We therefore argue that there is a need for

critical reflection on the prevailing understanding of digital competence. Con-

sequently, this article will discuss the notion of digital competence in general,

and further argue for defining teachers’ digital competence in a broad perspec-

tive. This will be done by suggesting a framework for the notion of digital

competence for teachers, which includes three aspects: teaching of ICT; teach-

ing about ICT; as well as teaching with ICT. Teaching of ICT concerns training

in digital tools and technology use, teaching about ICT is to teach about tech-

nology itself as well as the impact on society, and teaching with ICT is about

arranging for student learning with digital tools.

THE NOTION OF DIGITAL COMPETENCE

The notion of digital competence can be related to the concept of digital liter-

acy, which is i.e. discussed by Tyner (1998). “Literacy” is basically the English

word for the ability to read, but is currently used in an expanded and societal

context (Buckingham, 2006). Even though it is not directly synonymous with

the notion of literacy, the notion of competence is used in a similar way in a

Norwegian context. In combination with the term “digital”, both literacy and

competence have gradually been extended to cover different areas. Tyner

(1998) for example distinguishes between “tool literacy” and “literacy of rep-

resentation”. Tool literacy, also referred to as computer, network, and technol-

ogy skills, compounds the instrumental aspects of the technology, i.e. skills in

using various digital tools. Literacy of representation includes how technology

can be understood in our time, and how to use digital tools in a broader context.

Tyner’s distinction has been important for the evolving understanding of the

concept of digital competence.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

302 NOTION IN MOTION: TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE | JOHANNESEN, ØGRIM AND GIÆVER

Based on media studies, Buckingham (2006) also proposes an understanding

of digital literacy as encompassing more than purely instrumental skills. He

argues that the ability to evaluate and use information critically, but also to

understand the role of technology and technological development in a social,

political, and economic perspective are essential parts of digital competence.

van Dijk (2013) brings the aspects of power and inequality into the discussion.

He divides digital skills into six categories. The first two are medium related,

namely operational skills required for operating a digital medium, and formal

skills required for handling the formal structures, such as browsing the Inter-

net. The next four categories are content related skills: information skills, like

searching and evaluating information, communication skills, strategic skills

for achieving professional and personal goals, and content creation skills.

In the Norwegian context, there are several proposed definitions of digital lit-

eracy and competence. “Digital bildung” was proposed in 2003 as an alterna-

tive concept in a problem paper (Søby, 2003). The notion of digital bildung is

presented as a vision, which involves providing the learners with: “an oppor-

tunity to use ICT confidently and innovatively so as to develop the skills,

knowledge and expertise they need to achieve personal goals and to be inter-

active participants in a global information society” (p. 5) [our translation].

In his discussion, Søby, in line with Buckingham, notes that the notion of skill

is too narrow, arguing that the German term of “bildung” includes a “compre-

hensive understanding of how children and young people learn and develop

their identity” (Søby, 2003, p. 8) [our translation]. This can be seen as related

to both Tyner’s and Buckingham’s arguments for including the critical under-

standing of technology in a societal setting with the definition of digital liter-

acy.

In 2004, an official Norwegian definition was proposed in a White Paper,

which is here translated by Erstad (2006, p. 417):

Digital literacy is the sum of simple ICT skills, like being able to read, write

and calculate, and more advanced skills that makes creative and critical use

of digital tools and media possible. ICT skills consist of being able to use

software, to search, locate, transform and control information from differ-

ent digital sources, while the critical and creative ability also imply an abil-

ity to evaluate, use sources of information critically, interpret and analyse

digital genres and media forms. In total digital literacy can be seen as a very

complex competence (Ministry of Education and Research, 2004, p. 48).

Inspired by this, Erstad presents a general definition: digital literacy comprises

the “skills, knowledge and attitudes in using digital media, as to be able to mas-

ter the challenges in learning society” (Erstad, 2006, p. 417). A comparable

approach to the concept is found in Bjarnø, Giæver, Johannesen and Øgrim

(2009): “Digital competence involves the ability to use digital tools and have

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

© UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET | NORDIC JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LITERACY | VOL 9 | NR 4-2014 303

an adequate understanding of the technology and thereby be able to work in

and influence society” (p. 16) [our translation]. Both definitions include the

skill-oriented aspects of the technology, yet emphasising understanding of the

technology in a broader sense, which includes knowledge about and attitudes

towards the use of technology in the society.

Further, Erstad (2010) argues for operationalizing the concept of digital liter-

acy in what he proposes as basic components of the concept. These are basic

skills in using computers and software to download and upload different types

of information, knowing how to search for information, being able to navigate

within, classify, integrate and evaluate various types of information, commu-

nicating and expressing oneself through different meditational means, using

digital tools for collaboration, and finally, being able to create and design com-

plex digital material.

This somewhat historical review of the notion of digital competence illustrates

a motion towards a broad, holistic definition, emphasizing the role of ICT in

learning. Within this, the elements of technical skills, such as tool literacy

(Tyner, 1998) and instrumental skills (Buckingham, 2006) constitute a founda-

tion. Any definition of digital competence must include basic skills in using

digital tools. Moreover, both Erstad (2010) and van Dijk (2013) present digital

competence as including creative abilities, presupposing students to have

experiences in using technology to produce knowledge, thus learning with

technology. Finally, digital competence should include a critical understanding

of the societal use of technology and the formation of young people (Bucking-

ham, 2006; Søby, 2003). Accordingly, the notion of digital competence can be

understood as composed of three elements of using, producing, and bildung.

This threefold perspective of digital competence will be the basis of the discus-

sions in this article.

DIGITAL COMPETENCE IN THE NORWEGIAN NATIONAL

CURRICULUM AND POLICIES

Today’s children are growing up in a digital reality that is quite different from

what adults experienced in childhood, yet we do not know what reality they

will face in the 21st century. This is one of many challenges for education.

Prensky (2012) makes an issue of the fact that the school system is not

designed to meet the rapid technological changes. He describes the generation

who during their whole life have been surrounded by computers, digital

games, music players, camera recorders and mobile phones as digital natives.

Previous generations are described as digital immigrants. In our opinion such

a divide is not necessarily a question of generation or age, but can as well be

an issue of gender, social class, education, cultural background, and the like.

Nevertheless, it is interesting to dwell on what challenges different frame-

works for understanding the role of technology can bring about for education,

in particular the differences between the competences gained in schools and in

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

304 NOTION IN MOTION: TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE | JOHANNESEN, ØGRIM AND GIÆVER

leisure time and what kind of expertise students might bring into school (Ers-

tad & Sefton-Green, 2013). We know from the Norwegian national survey of

media habits (Medietilsynet, 2012) that children and young people have access

to digital media outside of school, and that much of their social life is engaged

in gaming and social networking. Consequently, or so the arguments goes, stu-

dents’ every-day digital literacy forms a foundation that schools should build

upon and develop further. Basically this is a question of student learning and

arranging for schools to be “up to date” and relevant. However, even if many

students have achieved a certain level of digital skill through out-of-school

use, these skills are often fragmented and not relevant for schooling (Bjarnø et

al., 2009). In addition, there is a major disparity among the individual students

(Østerud & Schwebs, 2009).

“Learning to use technologies” and “using technologies to learn” are terms

that were utilized in the instructions for use of digital tools in Norwegian

schools in the late 90’s (Ministry of Education Research and Church Affairs,

1995; Statssekretærutvalget for IT, 1996). These terms indicate two different

approaches to using digital tools. On the one hand, digital tools should be used

to support learning in subject-areas; on the other hand, students should learn

how to use digital tools and learn about the technology so that they could use

such digital tools in a productive way. A similar division can also be found in

international literature in terms of “education for ICT” vs. “ICT for educa-

tion”, most often with the argument that there is a need for a shift from the first

toward the latter (Unwin, 2005).

In the White Paper “Culture for Learning” (Ministry of Education and

Research, 2004), five basic skills were introduced as the backbone of the

Knowledge Promotion. The introduction of the “ability to use digital tools” as

one of the five basic skills, brought the concept of digital competence to the

same level of aims as reading, writing, numeracy, and spoken language in the

Norwegian schools. According to the Knowledge Promotion text, the use of

digital tools must be an integral part of all subject-area learning. Consequently,

the use of digital tools becomes more binding than in previous national curric-

ula. Prior to this, the terms, which were used to describe digital tools in school-

ing had been influenced by words like “may” and “should”, rather than “must”.

Nevertheless, the choice of the phrase “ability to use” emphasizes the instru-

mental aspects of digital competence, and thus other aspects, including the

understanding of and attitudes towards technology, seem to be less empha-

sized.

The very idea of the Knowledge Promotion, that digital skills are included as

a basic skill, may be utilized to fulfil the ideal of using technologies to learn.

Beck and Øgrim (2009) argue from a technology perspective that there are

three areas where students need to know about technology. Firstly, students

must be confident users of technology. Second, they must develop an under-

standing of how the technology works. Finally, students must gain knowledge

about the role of technology in society, so that they have the potential to influ-

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

© UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET | NORDIC JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LITERACY | VOL 9 | NR 4-2014 305

ence it. In a sense, these arguments elaborate on the term learning to use tech-

nologies.

A framework for basic skills was developed as a part of the revision of the

National Curriculum for Knowledge Promotion in 2012. In this, digital skills

were defined as follows:

Digital skills involve being able to use digital tools, media and resources

efficiently and responsibly, to solve practical tasks, find and process infor-

mation, design digital products and communicate content. Digital skills

also include developing digital judgment by acquiring knowledge and good

strategies for the use of the Internet (Norwegian Directorate for Education

and Training, 2012).

At the same time, the term “ability to use digital tools” is changed to “digital

skills”, thereby focusing more on attitudes, understanding and communication,

and to a lesser extent on the software and digital equipment. Yet, the term

‘skills’ is quite narrow, and can be said to cover only what Tyner (1998) calls

‘tool literacy’, Buckingham (2006) calls instrumental ‘skills’ and van Dijk

(2013) calls ‘medium related skills’. On the other hand, digital skills are

described in the framework as “learning to use digital tools, media and

resources and learning to make use of them to acquire subject-related knowl-

edge and express one’s own competence” (Norwegian Directorate for Educa-

tion and Training, 2012), which illustrates a broad understanding of the notion

of skills that corresponds to the twofold distinction from the 90’s (learning to

use/using to learn). In this new framework for basic skills, the term digital

judgment has been given increased attention. The framework includes topics

such as source awareness, privacy, copyright, and netiquette which are typi-

cally non-instrumental, but still essentials of digital competence (Norwegian

Directorate for Education and Training, 2012). Digital judgement as a subject

area builds upon the importance of critical reflection on the use of technology.

This can be related to the term bildung, as discussed by Søby (2003).

The new definition of digital skills, given by The Norwegian Directorate for

Education and Training (2012), embraces the historical lines outlined in the

discussion above, concurrently using contemporary concepts. In our opinion,

it might seem like they have finally succeeded in formulating a definition,

which is timely enough to embrace the contemporary perception of digital

competence, yet robust enough to embrace the future digital age.

To summarize, the Norwegian national policy documents address three aspects

of digital competence in the school system. The first is learning to use technol-

ogy, which is strongly related to the use aspects of digital competence pro-

posed earlier in in this article. The second is using technology for learning and

has become the most important one in the Knowledge Promotion. This aspect

may be related to the previously proposed productive aspects of digital com-

petence. The third is highlighted in the framework for basic skills, where

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

306 NOTION IN MOTION: TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE | JOHANNESEN, ØGRIM AND GIÆVER

aspects of critical reflection on the use of technology are included. Accord-

ingly, the notion of digital competence, within the national policy documents,

can be understood as composed of learning to use, using to learn, and critical

reflection.

THE TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE

The landscape described above is where teachers act. They must meet the

expectations set out in the national curriculum and facilitate the development

of digital competence among students. This requires digitally competent teach-

ers; teachers with digital confidence and with a digital repertoire that can form

a basis for making educated choices about when and how technology should

be integrated into the educational practice.

Each subject presented in the national curriculum is described in terms of basic

skills relevant to that particular subject. For most subjects, skills in the use of

digital tools and critical reflections are described. The curriculum is based on

the idea of freedom of methods for teaching; yet, some methods and techno-

logical solutions are mentioned explicitly, for example, the use of spreadsheets

for presenting data graphically. However, in general, teachers should be

trained to choose, assess, and implement the technology that works with the

teaching and learning in action. In sum, the Knowledge Promotion sets high

demands on the teachers’ ability to convert their digital competence into teach-

ing in terms of the practical integration of digital tools in subject areas. On the

other hand, digital competence is not explicitly defined in the National Curric-

ulum Regulations for Teacher Education (Ministry of Education and Research,

2010). Conversely, it is incorporated in learning outcomes for each of the sub-

ject areas of the teacher training programme.

According to Wasson and Hansen (2014), Norwegian teachers are among the

most digitally competent as compared to colleagues from other countries.

They use ICT for a variety of tasks. Yet, there are issues to address, such as

management of technology rich classrooms (Giæver, Johannesen, & Øgrim,

2013) and the role of teacher education in the training of pre-service teachers

(Gudmundsdottir, Loftsgarden, & Ottestad, 2014).

Mishra and Koehler (2006a, 2006b) present the notion of technological, peda-

gogical, and content knowledge (the TPACK model) to describe the compound

skills required for a teacher to integrate digital tools for learning in a productive

way. The model is one way of describing the skills a teacher should possess in

order to realize the aims of integrating digital literacy into the learning proc-

esses. According to this model, the teacher needs technological knowledge, as

well as knowledge about content and pedagogy. In addition, they need the com-

pound knowledge of issues raised from the intersections between technology,

pedagogy, and content (in this model named TPACK). The main focus in the

TPACK model is how to use integrated technology as a means for learning other

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

© UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET | NORDIC JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LITERACY | VOL 9 | NR 4-2014 307

subject areas. However, the discussion in this article aims at illuminating the

contextual and holistic nature of digital competence among teachers, namely all

parts of the technology dimension, not only the knowledge that is illustrated in

the intersections with content knowledge and pedagogical knowledge.

Using both the definition and the operationalization of digital literacy from Erstad

as a stepping-stone, Krumsvik aims to define teacher competence in his discus-

sion of digital competence (Krumsvik, 2014, 2007). In addition to basic skills,

tools, expertise, and digital bildung, he presents and discusses teacher learning

strategies and their ability to assess the relevance of ICT in a pedagogical setting

as important competences. We strongly support this wide and compound under-

standing of teachers’ digital competence, and will further elaborate on this.

Koschmann (1995) suggests three different approaches to what he describes as

the training of computer literacy; learning with computers, learning through

computers, and learning about computers. In the following, we will elaborate

on these approaches in order to address teacher competence, and relate

Koschmann’s learning approaches to teaching approaches. The notion of

learning with computers, or using computer programs as means for learning,

is described as the most powerful one. However the notion of learning through

computers, which encompasses on-line tutorials, simulations, and computer-

assisted instructions, is separated from the notion of learning with computers.

We will argue that technology development, in general, and changes in use pat-

terns imposed by the Internet, make this distinction less relevant for describing

the contemporary use of learning technology. Rather, the two approaches bring

to mind what was previously described as using technology to learn.

Koschmann’s way of describing learning about computers includes “the

straightforward means of addressing the need for computer literacy” (p. 819).

We argue that the notion of learning about ICT has become much more com-

plex since Koschmann published this, and that a more contemporary under-

standing should include both basic knowledge about the technology itself, as

well as bildung aspects like digital judgment and the role of ICT in society.

Salomon and Perkins (2005) discuss how technology effects the human intel-

lect, and in particular, the effects of performance with, of, and through the use

of technology. By effects with technology, they understand the technology as

a partner and look for amplified performance when using technology, for

instance, with improved spelling. The effects of technology are explained as

effects that persist, even when technology is not at hand, exemplified by the

idea of writing to read (Trageton, 2004). Effects through technology are seen

as long-term effects and organizational changes; for instance, how the use of

cars has changed the communication system, or how scientific inquiry is ful-

filled today. There is no clear vision of teacher competence in these terms.

However, Salomon and Perkins’ notion of performance with technology is pre-

sented as having an immediate or short-term effect, while performance of and

through has long term effects. Yet, all effects are to be carefully considered

when trying to understand digital competence among teachers.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

308 NOTION IN MOTION: TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE | JOHANNESEN, ØGRIM AND GIÆVER

Unwin (2005) argues that there is a need to shift from education for ICT to the

use of ICT for education. He states that teachers require a deep understanding

of how the benefits of ICT may be used in teaching, rather than ICT-skills. He

argues that the teaching of ICT-skills, or learning to use technology, should be

reduced, at the expense of using technology for learning. In a contemporary

context, these arguments can be seen as a response to the lack of technology

integration in the teaching and learning process. However, we argue that as a

result these kinds of critiques, as implemented in Knowledge Promotion,

might have contributed to a motion away from the idea about the basic training

of technology use as a necessary foundation for using technology for learning.

Buckingham (2006) presents a critical notion of digital literacy, including a

conceptual framework of elements for mapping the field. According to Buck-

ingham (pp. 267, 268), a literate person must understand how the language

works, be able to evaluate the material encountered, know who is communi-

cating with whom, and understand their audience. From a media literacy per-

spective he herby emphasizes the need for critical reflection as an important

part of digital competence. We argue that such awareness is to be nurtured in

all aspects of the students’ digital competence, and as such, be an essential part

of a teacher’s competence.

As mentioned above, Beck and Øgrim (2009) present three areas of required

student competence: use competence, technology competence, and compe-

tence with computers in society. Use competence can of course be attained,

however, in order for the students to internalize their knowledge the technol-

ogy must be practiced by employing technology for learning. Finally, they

argue that competence with computers in society is only achieved by being

taught about information and communication technology (ICT). However,

they do not include the needed teacher competence in their discussion. From

our perspective, use competence, technology competence, and competence

with computers in society must be taught explicitly; therefore requiring spe-

cific digital competence for teachers.

Teaching of, with and about ICT

Based on the discussion presented above, we propose that a teacher’s digital

competence is threefold: teaching of, with, and about ICT.

The teaching of ICT means to plan and facilitate the students, gradually

increasing their digital competence through systematic training. This may

involve hands-on training in keyboard use and programs, such as word

processing and spreadsheets, the development of good search strategies and to

know how to act according to source awareness, copyright, privacy and neti-

quette. This corresponds with Koshmann’s approach to “learning about com-

puters”. In teacher education, as well as in the schools, this is a low priority

area.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

© UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET | NORDIC JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LITERACY | VOL 9 | NR 4-2014 309

Teaching with ICT means using technology as a tool in other disciplines to

achieve added value in learning. This area is emphasized by many (Bucking-

ham, 2006; Koschmann, 1995; Salomon & Perkins, 2005; Unwin, 2005). The

purpose is primarily to increase learning outcomes through variation in content

and teaching methods, but also to contribute to the students’ digital literacy by

exposing them to the exemplary, diverse, and effective use of various technol-

ogies. It involves using technology carefully and systematically in the teaching

of all subject areas at most times. This corresponds with Koshmann’s two

approaches of “learning with” and “learning through” computers. Teaching

with ICT may appear to be the main focus in primary and secondary schools,

as well as in teacher education . Teaching with ICT is crucial for pupils and stu-

dents to become familiar and up-to-date with relevant technology for learning.

However, this kind of technology use does not necessarily develop the holistic

digital competence as described in the curriculum and national policies.

Teaching about ICT includes technology history and the dialectical relation-

ship between technology and society - issues that are addressed by Søby

(2003) and Buckingham (2006). It includes the investigation of technology

development and its social and cultural significance, as well as assignments for

engaging students in participating in democratic development in digital media

(Beck & Øgrim, 2009). These issues are to be addressed within all teaching

activities, and should build upon the digital judgment that (hopefully) is devel-

oped as a part of teaching of ICT and teaching with ICT.

DIGITAL COMPETENCE, CURRICULUM AND

TEACHER COMPETENCE

As a result of the strong focus on integration in certain subject areas, many pri-

mary and secondary schools in Norway have closed down specialized compu-

ter labs and reduced the systematic training in digital tools (Engen, Giæver, &

Øgrim, 2009). This implies a risk of blurring the responsibility for the stu-

dents’ digital literacy as a compound subject area – not only a skill for learning.

This is supported by research stating that ICT is weak in teacher education

(Tømte, Kårstein, & Olsen, 2013). Mobile technologies such as laptops and

tablets are procured for teaching subject areas with ICT in technology rich

classrooms. Digital competence as an independent discipline seems to have

disappeared on the way from the definition in the White Paper (Ministry of

Education and Research, 2004), through the curriculum, and into practice in

the classroom. As long as the focus is solely on digital competence as inte-

grated in subject areas, a specific kind of technological infrastructure is

needed, namely that of the mobile technologies at hand. Based on the argu-

ments given above, we ask whether the know-how dimension of digital com-

petence has been so blurred that it has been a taken-for-granted competence

area, although it is within the mandate of the curriculum.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

310 NOTION IN MOTION: TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE | JOHANNESEN, ØGRIM AND GIÆVER

We have presented different aspects of digital competence, and in all aspects

more elements can be found. The notion of digital competence can be divided

into use aspects, as represented by Erstad’s operationalization; aspects of pro-

duction, as represented by Tyner’s tool literacy; and the comprehensive idea of

bildung as represented by Søby. When discussing digital competence in the

context of the national curriculum, the use of ICT in learning can be divided

into the use of technology for learning, learning to use technology, and critical

reflection. Learning to use technology corresponds with the use of general def-

initions, while the use of technology for learning can be regarded as produc-

tion. Critical and conscious reflection of technology-use can certainly be

related to the term bildung. We argue that the two sets of understanding of dig-

ital competence given from general definitions, and the national curriculum

and policies, constitute a stepping-stone for understanding the teacher compe-

tences that are needed. Of course, there is more to these categories than what

has been somehow superficially presented and related here. Still, we believe

that the relationships, as illustrated in the table below, can serve as a means for

overviewing the holistic picture and illustrating the arguments for a threefold

understanding of teachers’ digital competence.

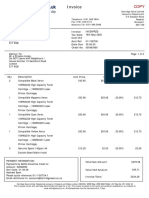

General definitions Curriculum and policies Teacher competences

Using Learning to use technology Teaching of ICT

Producing Using technology to learn Teaching with ICT

Bildung Critical reflection Teaching about ICT

In the third column, the digital competences for teachers and teacher trainers

are presented, and categorized as teaching of, with and about ICT. The teach-

ing of ICT is related to the use aspects of digital competence and with the idea

of learning to use technology. Teaching with ICT is related to the production

of digital competence and the pedagogical idea of using technology for learn-

ing. Teaching about ICT is related to the bildung aspects of digital competence

and the idea of the critical evaluation of technology from the national curricu-

lum.

FINAL REMARKS

During the last two decades, an emphasis on learning with technology has

strongly influenced the understanding of digital competence. In this article, we

have presented the motional nature of the notion of digital competence, with a

particular focus on teachers’ digital competence. Based on general definitions

of digital competence and national policy documents, we present a threefold

view of digital competence as a basis for mapping out the contextual and holis-

tic view of teacher competence in ICT. As a result, we propose an augmented

comprehension of teachers’ digital competence as the knowledge needed to

perform teaching of ICT and teaching about ICT as well as teaching with ICT.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

© UNIVERSITETSFORLAGET | NORDIC JOURNAL OF DIGITAL LITERACY | VOL 9 | NR 4-2014 311

Furthermore, we argue that this enriched understanding of teachers’ digital

competence should have consequences for teacher education programmes. We

propose that further research should be carried out to determine in what ways

teacher training can arrange for pre-service teachers to be trained in all aspects

of digital competence, and consequently be able to conduct the teaching of,

with, and about ICT.

REFERENCES

Beck, E.E., & Øgrim, L. (2009). Bruke, forstå, forandre: Hva trenger elever lære om IKT?

In S. Østerud & T. Schwebs (Eds.), ENTER: Veien mot en IKT-didaktikk (pp. 174–190).

Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

Bjarnø, V., Giæver, T.H., Johannesen, M., & Øgrim, L. (2009). Didiktikk : digital

kompetanse i praktisk undervisning. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Buckingham, D. (2006). Defining digital literacy – What do young people need to know

about digital media? Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 1(4).

Convery, A. (2009). The pedagogy of the impressed: how teachers become victims of

technological vision. Teachers & Teaching, 15(1), 25–41. doi: 10.1080/

13540600802661303

Engen, B.K., Giæver, T.H., & Bjarnø, V. (2008). Integrating ICT in teaching: The winding

road to bridge the gap between teacher education and teachers’ practice. In J. B. Curtis,

M. M. Lee & T. H. Reynolds (Eds.), E-Learn 2008. World Conference on E-Learning in

Corporate, Government, Healthcare, & Higher Education. Association for the

Advancement of Computing in Education.

Engen, B.K., Giæver, T.H., & Øgrim, L. (2009). Bruke, forstå, undervise. BALLAST Bruk

Av ikt fra Lærerutdanning til Læring og Arbeidspraksis i Skole over Tid.

Ernes, A.K.B. (2008). Lærere sliter med IKT-bruk i undervisning. digi.no, 17. mars.

Erstad, O. (2006). A new direction? Eduction and Information Technology 09/2006, 11(3),

415–429. doi: DOI 10.1007/s10639-006-9008-2

Erstad, O. (2010). Educating the digital generation. Exploring medial literacy for the 21st

century. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 5(1), 56–72.

Erstad, O., & Sefton-Green, J. (2013). Identity, community, and learning lives in the digital

age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giæver, T.H., Johannesen, M., & Øgrim, L. (2013). Klasseledelse med IKT. In H.

Christensen & I. Ulleberg (Eds.), Klasseledelse, fag og danning (pp. 211–230). Oslo:

Gyldendal Akademisk.

Gudmundsdottir, G.B., Loftsgarden, M., & Ottestad, G. (2014). Nyutdannede lærere.

Profesjonsfaglig Digtal kompetanse og erfaringer med IKT I lærerutdanningen: Senter for

IKT i utdanningen.

Haugsbakk, G. (2010). IKT over hodet på lærerne, Dagbladet. Retrieved from http://

www.dagbladet.no/2010/05/07/kultur/debatt/debattinnlegg/it/skole/11626750/

Koschmann, T. (1995). Medical education and computer literacy: Learning about, through,

and with computers. Academic Medicine, 70(NO 9/September), 818–821.

Krumsvik, R.J. (2009). Situated learning in the network society and the digitised school.

European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(2), 167–185. doi: 10.1080/

02619760802457224

Krumsvik, R.J. (2014). Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of

Educational Research, 58(3), 269–280. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2012.726273

Krumsvik, R.J. (Ed.). (2007). Skulen og den digitale læringsrevolusjonen. Oslo:

Universitetsforlaget.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

312 NOTION IN MOTION: TEACHERS’ DIGITAL COMPETENCE | JOHANNESEN, ØGRIM AND GIÆVER

Medietilsynet. (2012). Barn og medier 2012: fakta om barn og unges (9–16 år) bruk og

opplevelser av medier. Fredrikstad: Medietilsynet.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2004). Culture for learning. White paper no 30

(2003–2004). Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Retrieved from

http://www.regjeringen.no/en/dep/kd/documents/brochures-and-handbooks/2004/report-

no-30-to-the-storting-2003-2004.html?regj_oss=1&id=419442.

Ministry of Education and Research. (2010). National Curriculum Regulations for

Differentiated Primary and Lower Secondary Teacher Education Programmes for Years

1–7 and Yerars 5–10.

Ministry of Education Research and Church Affairs. (1995). IT i norsk utdanning. Plan for

1996–99.

Ministry of Education Research and Church Affairs. (2004). Core Curriculum for primary,

secondary and adult education in Norway. Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/Upload/

larerplaner/generell_del/5/Core_Curriculum_English.pdf?epslanguage=no.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M.J. (2006a). Introducing TPCK. In J. A. Colbert, K. E. Boyd, K.

A. Clark, S. Guan, J. B. Harris, M. A. Kelly & A. D. Thompson (Eds.), Handbook of

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge for Educators (pp. 1–29). New York:

Routledge.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M.J. (2006b). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A

framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054.

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2012). Framework for basic skills.

Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/PageFiles/66463/

FRAMEWORK_FOR_BASIC_SKILLS.pdf?epslanguage=no.

Prensky, M. (2012). From digital natives to digital wisdom: Hopeful essays for 21st century

learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Sabaliauskas, T., Bukantaitė, D., & Pukelis, K. (2006). Desiging teacher information and

communication technology competencies’ areas. Vocational Education: Research &

Reality(12), 152–165.

Salomon, G., & Perkins, D. (2005). Do technologies make us smarter? Intellectual

amplification with, of, and through technology. In R. J. Sternberg & D. D. Preiss (Eds.),

Intelligence and Technology: The Impact of Tools on the Nature and Development of

Human Abilities (pp. 71–85). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,.

Statssekretærutvalget for IT. (1996). Den norske IT-veien. Bit for Bit.

Søby, M. (2003). Digital kompetanse, Fra 4. basisferdighet til digital dannelse. Et

problemnotat Oslo: ITU.

Trageton, A. (2004). Playful computer writing grade 1–4 (6–9 years). Writing to read.

Paper presented at the 23. ICCP World Play Conference, 15–17 September 2004, Krakow.

Poland.

Tyner, K. (1998). Literacy in a digital world: Teaching and learning in the age of

information. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Tømte, C., Kårstein, A., & Olsen, D.S. (2013). IKT i lærerutdanningen. På vei mot

profesjonsfaglig digital kompetanse? : NIFU Nordisk institutt for studier av innovasjon,

forskning og utdanning.

Unwin, T. (2005). Towards a framework for the use of ICT in teacher training in Africa.

Open Learning: The Journal of Open and Distance Education, 20(2).

van Dijk, J.A.G.M. (2013). A theory of the digital divide. In M. Ragnedda & G. W.

Muschert (Eds.), The Digital divide: The internet and social inequality in international

perspective (pp. XX, 324 s. : ill.). London: Routledge.

Wasson, B., & Hansen, C. (2014). Making use of ICT: Glimpses from Norwegian teacher

practices. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy Special Issue, 9(1), 44–65.

Østerud, S., & Schwebs, T. (2009). Mot en ikt-didaktikk. In S. Østerud & T. Schwebs

(Eds.), ENTER: Veien mot en IKT-didaktikk (pp. 11–32). Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

This article is downloaded from www.idunn.no. Any reproduction or systematic distribution

in any form is forbidden without clarification from the copyright holder.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Yang, Chen & Hung (2020) Digital Storytelling As An Interdisciplinary Project To Improve Students' English Speaking and Creative ThinkingDocument24 pagesYang, Chen & Hung (2020) Digital Storytelling As An Interdisciplinary Project To Improve Students' English Speaking and Creative ThinkingEdward FungNo ratings yet

- 2020 Annual Profile - ENDocument64 pages2020 Annual Profile - ENGeraldNo ratings yet

- Evidence Requirements by Key Result Area Key Result Area Objectives Means of VerificationDocument9 pagesEvidence Requirements by Key Result Area Key Result Area Objectives Means of VerificationJoji Matadling Tecson100% (1)

- Reaching Hearts and Minds - Exploring Learning Using Blogs, Wiki, Twitter and WalkthroughsDocument11 pagesReaching Hearts and Minds - Exploring Learning Using Blogs, Wiki, Twitter and WalkthroughsPer Arne GodejordNo ratings yet

- Røkenes Krumsvik 2014 Development of Student Teachers Digital Competence in Teacher Education A Literature ReviewDocument31 pagesRøkenes Krumsvik 2014 Development of Student Teachers Digital Competence in Teacher Education A Literature ReviewJose ChavesNo ratings yet

- DFL 0102 10 Davidsen GeorgsenDocument18 pagesDFL 0102 10 Davidsen GeorgsenMay Anne AlmarioNo ratings yet

- Digital Pedagogy For Sustainable LearningDocument7 pagesDigital Pedagogy For Sustainable LearningchandiliongNo ratings yet

- Sciencedirect: Designing Creative Pedagogies Through The Use of Ict in Secondary EducationDocument12 pagesSciencedirect: Designing Creative Pedagogies Through The Use of Ict in Secondary Educationbleidys esalasNo ratings yet

- Digital Competence and Digital Technology A Curriculum Analysis of Norwegian Early Childhood Teacher Education - 2023 - RoutledgeDocument17 pagesDigital Competence and Digital Technology A Curriculum Analysis of Norwegian Early Childhood Teacher Education - 2023 - RoutledgeENRIQUE GUZMAN SINARAHUANo ratings yet

- A Study of The Effects ofDocument12 pagesA Study of The Effects ofNorein Erum RomasocNo ratings yet

- Computer and LearningDocument20 pagesComputer and Learningjacobo22No ratings yet

- Digital Competence in Norwegian Teacher Education and SchoolsDocument14 pagesDigital Competence in Norwegian Teacher Education and SchoolssevillistaNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning Model of Teaching Programming in Higher EducationDocument15 pagesBlended Learning Model of Teaching Programming in Higher EducationPedroNo ratings yet

- Rna LT Pack ComputerDocument10 pagesRna LT Pack ComputerEmi LeeNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document12 pagesFULLTEXT01Malen GallegosNo ratings yet

- Practices and Challenges in An Emerging M-Learning EnvironmentDocument21 pagesPractices and Challenges in An Emerging M-Learning EnvironmentjebessaNo ratings yet

- Developing Teachers Digital Identity Towards The Pedagogic Design Principles of Digital Environments To Enhance Students Learning in The 21st CentuDocument20 pagesDeveloping Teachers Digital Identity Towards The Pedagogic Design Principles of Digital Environments To Enhance Students Learning in The 21st CentuRUBY HARIS 22.55.2334No ratings yet

- Open Educational Resources For Online Language Teacher Training: Conceptual Framework and Practical ImplementationDocument18 pagesOpen Educational Resources For Online Language Teacher Training: Conceptual Framework and Practical ImplementationijiteNo ratings yet

- BACO FOR PRINTING2. FINALxxDocument40 pagesBACO FOR PRINTING2. FINALxx1G- MAPA, KARLA MAYSONNo ratings yet

- Intercultural LearningDocument18 pagesIntercultural LearningI love ADNo ratings yet

- Ict Latest 1Document19 pagesIct Latest 1BM0622 Jessleen Kaur Balbir Singh BathNo ratings yet

- Appropriation of Digital Competence in Teacher EducationDocument17 pagesAppropriation of Digital Competence in Teacher EducationDAIANE PAZNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Digital LiterasiDocument17 pagesJurnal Digital Literasirosdiah harlinaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Educational Technology in TeachingDocument5 pagesThe Importance of Educational Technology in TeachingYuva KonapalliNo ratings yet

- eLearningChapter PreprintDocument23 pageseLearningChapter Preprintthaiduong292No ratings yet

- Investigating Deep and Surface Learning in Online CollaborationDocument7 pagesInvestigating Deep and Surface Learning in Online Collaboration409005091No ratings yet

- Perspectives and Challenges in E-Learning: Towards Natural Interaction ParadigmsDocument13 pagesPerspectives and Challenges in E-Learning: Towards Natural Interaction ParadigmsHarshith RaoNo ratings yet

- Action Research in TVE EIMDocument19 pagesAction Research in TVE EIMLand NozNo ratings yet

- Digital Transformation in German Higher Education: Student and Teacher Perceptions and Usage of Digital MediaDocument24 pagesDigital Transformation in German Higher Education: Student and Teacher Perceptions and Usage of Digital MediaMark Aaron B. SalesNo ratings yet

- COURSE OUTLINE Digital Literacy 2023Document8 pagesCOURSE OUTLINE Digital Literacy 2023IGA Lokita P UtamiNo ratings yet

- Digital Story TellingDocument21 pagesDigital Story TellingAnnie Abdul RahmanNo ratings yet

- Sadik, Alaa - 2008-Digital Storytelling A Meaningful Technology-Integrated Approach For Engaged Student learning-ARTDocument15 pagesSadik, Alaa - 2008-Digital Storytelling A Meaningful Technology-Integrated Approach For Engaged Student learning-ARTe-Teacher Miguel H.No ratings yet

- Digital Skills of Teachers: Anna SerezhkinaDocument3 pagesDigital Skills of Teachers: Anna SerezhkinaRoxAnna GoganNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Digital Literacy Competence of Pre-Service English Teacher in Indonesia and ThailandDocument9 pagesAssessing The Digital Literacy Competence of Pre-Service English Teacher in Indonesia and ThailandJournal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Digital Humanities and Study of Literature: Perspectives in Distance EducationDocument6 pagesDigital Humanities and Study of Literature: Perspectives in Distance EducationTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Digeulit - A European Framework For Digital Literacy: A Progress ReportDocument7 pagesDigeulit - A European Framework For Digital Literacy: A Progress ReportI Wayan RedhanaNo ratings yet

- Primary School - The Content of Educational Technology Curricula A Cross-Curricular State of The ArtDocument21 pagesPrimary School - The Content of Educational Technology Curricula A Cross-Curricular State of The ArtAndiniNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Implementation of E-Learning System in Secondary Schools in Nigeria.Document21 pagesIntroduction and Implementation of E-Learning System in Secondary Schools in Nigeria.Odd OneNo ratings yet

- Full Text 01Document33 pagesFull Text 01ermawatiNo ratings yet

- Learners' Technology Integration in English Language LearningDocument11 pagesLearners' Technology Integration in English Language LearningPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Technology Within Classroom Literacy ExperiencesDocument26 pagesIncorporating Technology Within Classroom Literacy ExperiencesEsemuze LuckyNo ratings yet

- Guitart Mas, Doménech, OroDocument25 pagesGuitart Mas, Doménech, Orokaredok2020 anNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument6 pagesJurnal InternasionalKhairy WorkspaceNo ratings yet

- Digital Mindsets: Teachers' Technology Use in Personal Life and TeachingDocument17 pagesDigital Mindsets: Teachers' Technology Use in Personal Life and TeachingRakshith b yNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Ict Tools in EducationDocument8 pagesResearch Papers On Ict Tools in Educationgw2cgcd9100% (1)

- Journal Pre-Proof: The Internet and Higher EducationDocument35 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: The Internet and Higher EducationvogonsoupNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 37 - Articles - 214486 - Submission - Proof - 214486 433 529585 1 10 20210915Document19 pagesAjol File Journals - 37 - Articles - 214486 - Submission - Proof - 214486 433 529585 1 10 20210915matlholalebogang701No ratings yet

- Diligent (Digital Literacy Agent) Nurturing English Future Teachers' Competence in The Digital EraDocument10 pagesDiligent (Digital Literacy Agent) Nurturing English Future Teachers' Competence in The Digital EraNia GaryadiNo ratings yet

- Draft Essay Vina Aisyi RodhiyahDocument33 pagesDraft Essay Vina Aisyi RodhiyahVina AisyiNo ratings yet

- Flipped Learning in Listening Class: Best Practice Approaches and ImplementationDocument10 pagesFlipped Learning in Listening Class: Best Practice Approaches and ImplementationTrung Kiên NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Education Paper StudiesDocument25 pagesEducation Paper StudiesAnna RosaNo ratings yet

- EJ1101886Document4 pagesEJ1101886Erika Marie DequinaNo ratings yet

- From Teacher Oriented To Student Centred Learning, Developing An ICTSupportedDocument9 pagesFrom Teacher Oriented To Student Centred Learning, Developing An ICTSupportedwhitetulipNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document11 pagesArticle 1amadakrammNo ratings yet

- Digital Literacy Awareness Among Students: October 2016Document8 pagesDigital Literacy Awareness Among Students: October 2016Via oktavianiNo ratings yet

- ICT Vs LTKDocument5 pagesICT Vs LTKdesmontandoakrmnNo ratings yet

- ICT in The English Classroom Qualitative Analysis of 2017 Procedia SociaDocument6 pagesICT in The English Classroom Qualitative Analysis of 2017 Procedia SociaDiogo OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Digital Literacies and LearningDocument24 pagesDigital Literacies and LearningDavid DavidNo ratings yet

- Bridging Insula Europae Swedish National Research: Reports of Results and ConclusionsDocument12 pagesBridging Insula Europae Swedish National Research: Reports of Results and ConclusionsCentro Studi Villa MontescaNo ratings yet

- 2 IJOES-Dr Bipin (8-13)Document6 pages2 IJOES-Dr Bipin (8-13)lugellezabellaNo ratings yet

- Design and Technology: Thinking While Doing and Doing While Thinking!From EverandDesign and Technology: Thinking While Doing and Doing While Thinking!No ratings yet

- Earthing System Design - Moving From Worst Case To The Big Picture PDFDocument10 pagesEarthing System Design - Moving From Worst Case To The Big Picture PDFHung nguyen manhNo ratings yet

- Orientation On The Manual For The Evaluation (Autosaved)Document31 pagesOrientation On The Manual For The Evaluation (Autosaved)Em Boquiren CarreonNo ratings yet

- 17mat41 PDFDocument3 pages17mat41 PDFKruthik KoushikNo ratings yet

- NOTES - GUIDANCE AND COUNSELLING Manual 2021Document30 pagesNOTES - GUIDANCE AND COUNSELLING Manual 2021Mercy GakiiNo ratings yet

- M-428-Malhari Mahatmya - Kavikulguru Kalidas Sanskrit University Ramtek CollectionDocument47 pagesM-428-Malhari Mahatmya - Kavikulguru Kalidas Sanskrit University Ramtek Collectionshubhpatil1313No ratings yet

- Consultants ListDocument16 pagesConsultants Listarun84No ratings yet

- Ready To Go Lessons For Maths Stage 4 AnswersDocument9 pagesReady To Go Lessons For Maths Stage 4 AnswersNangNo ratings yet

- Invoice: Invoice Tax Date Cust Ord Acct Ref Date Due Order No. 005463400 Invoice ToDocument2 pagesInvoice: Invoice Tax Date Cust Ord Acct Ref Date Due Order No. 005463400 Invoice ToA PirzadaNo ratings yet

- Fitosoil Lab Test On VADocument2 pagesFitosoil Lab Test On VAkoko manjitNo ratings yet

- Tcs PapersDocument14 pagesTcs PapersAnkit AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Welded ConnectionDocument8 pagesWelded Connectionutsav_koshtiNo ratings yet

- BatStateU FO TAO 08 Grades Form 1 Regular Admission Rev. 02 1Document1 pageBatStateU FO TAO 08 Grades Form 1 Regular Admission Rev. 02 1asdfghNo ratings yet

- STATISTICS Powrepoint 2Document82 pagesSTATISTICS Powrepoint 2King charles jelord Cos-agonNo ratings yet

- Book List For Middle School and 9th Grade 2009-20102Document5 pagesBook List For Middle School and 9th Grade 2009-20102mrsfox100% (1)

- Biolyte Service Manual 4.2ADocument88 pagesBiolyte Service Manual 4.2AMatrixNo ratings yet

- Kale Mahesh Anant.: Qualification: B.E. Mechanical With Knowledge of CAD-CAEDocument4 pagesKale Mahesh Anant.: Qualification: B.E. Mechanical With Knowledge of CAD-CAEapi-3698788No ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Claudia - Badulescu@eui - EuDocument8 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Claudia - Badulescu@eui - EuLIBAN ODOWANo ratings yet

- Hitachi EX2600-7 KS-EN397Document20 pagesHitachi EX2600-7 KS-EN397Marcelo AksteinNo ratings yet

- DLP With Indicator ABM 2Document4 pagesDLP With Indicator ABM 2Yca BlchNo ratings yet

- More Than 5000 Questions Dr. BL Sharma Mathematics PageDocument4 pagesMore Than 5000 Questions Dr. BL Sharma Mathematics Pagerskr_tNo ratings yet

- PA3 v3.0 E Instruction ManualDocument30 pagesPA3 v3.0 E Instruction ManualcristianiacobNo ratings yet

- BetaBeat Reviews:Is It Best Soultion For Diabetes?Document6 pagesBetaBeat Reviews:Is It Best Soultion For Diabetes?bohigg popixNo ratings yet

- Mete AggiesDocument16 pagesMete AggiesJohn Renzel RiveraNo ratings yet

- EX - NO 3 (A) Applications Using TCP Sockets Like Echo Client and Echo Server AimDocument4 pagesEX - NO 3 (A) Applications Using TCP Sockets Like Echo Client and Echo Server AimHaru HarshuNo ratings yet

- GPP Action PlanDocument3 pagesGPP Action PlanSwen CuberoNo ratings yet

- Digitizing Reports Using Six Sigma - Lipsa Patnaik - Neha AroraDocument18 pagesDigitizing Reports Using Six Sigma - Lipsa Patnaik - Neha AroramanojpuruNo ratings yet

- Shortcrete PDFDocument4 pagesShortcrete PDFhelloNo ratings yet

- Client Comfort and End-of-Life Care Reflection and QuestionsDocument4 pagesClient Comfort and End-of-Life Care Reflection and QuestionsArkham100% (1)