Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2024 02 29 - Paper JC

2024 02 29 - Paper JC

Uploaded by

drmanashreesankheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2024 02 29 - Paper JC

2024 02 29 - Paper JC

Uploaded by

drmanashreesankheCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Article

Pediatric nasal septoplasty outcomes

Ryan Bishop1^, Rishabh Sethia2, David Allen1, Charles A. Elmaraghy2,3

1

The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA; 2Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, The Ohio State

University, Columbus, OH, USA; 3Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: CA Elmaraghy; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: CA

Elmaraghy; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors;

(VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Correspondence to: Charles A. Elmaraghy, MD, FACS, FAAP. Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 700

Children’s Drive, Columbus, OH 43205, USA. Email: charles.elmaraghy@nationwidechildrens.org.

Background: Corrective nasal surgery has historically been avoided in the pediatric population out of

concerns surrounding the potential disruption of nasal growth centers. There is a paucity of data on the rate

of complications or revision surgery following septoplasty in this population. As such, the purpose of this

study is to review the long-term outcomes of a large cohort of children who underwent nasal septoplasty and

to compare outcomes of septoplasty patients under the age of 14 to those 14 years and older.

Methods: A retrospective review was performed on all patients who received nasal septoplasty at our

tertiary care pediatric referral center between October 2009 and September 2016. All patients who

underwent septoplasty for a deviated nasal septum and were 0–18 years of age at the time of surgery were

included in this analysis. Outcomes were compared between patients under the age of 14 to those 14 years

and older. Demographic, surgical, and follow-up data were collected including complications and the need

for revision surgery.

Results: A total of 194 pediatric patients were identified as meeting inclusion criteria for the study. Mean

age for the total cohort was 14.6 years (0–18 years), with a mean of 15.9 years in the older group and

10.6 years in the younger group. Revision septoplasty was performed more frequently in the younger group.

However, no significant difference in the rate of complications was seen between the two groups.

Conclusions: To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective study examining outcomes

following septoplasty in pediatric patients. We also specifically examine outcomes of very young septoplasty

patients, a population for which limited evidence exists. Further retrospective studies are needed to validate

the use of nasal septoplasty in the pediatric population.

Keywords: Nasal septoplasty; pediatric septoplasty; revision septoplasty

Submitted Aug 03, 2021. Accepted for publication Oct 14, 2021.

doi: 10.21037/tp-21-359

View this article at: https://dx.doi.org/ 10.21037/tp-21-359

Introduction adverse effects on nasal and facial growth due to the

potential disruption of nasal growth centers (2,3). The septal

Corrective nasal surgery in the pediatric population may cartilage plays a major role in growth and development of the

be indicated for severe nasal obstruction or posttraumatic midface. Specifically, the sphenodorsal zone increases the

deformity (1). However, nasal septoplasty has historically length and height of the nasal bones, while the sphenospinal

been avoided in children because of concern regarding zone increases maxilla outgrowth (4,5). As a result, surgeons

^ ORCID: 0000-0003-0747-2652.

© Translational Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Transl Pediatr 2021;10(11):2883-2887 | https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tp-21-359

2884 Bishop et al. Pediatric nasal septoplasty outcomes

have adopted a cautious attitude towards correction of nasal care. Patients undergoing adjunctive procedures, including

septal deformities in the pediatric population, often electing valve repair, rhinoplasty, and/or inferior turbinate reduction

to wait until puberty to perform the procedure (3). Based were excluded from the study. Patient characteristics were

on completion of nasal growth, safe timeframes for nasal recorded, including age at the time of surgery, patient sex,

surgery have been estimated to be 16 years of age in boys surgical indication, complications, and need for revision

and 14 years of age in girls (5). surgery. If revision surgery was performed, the indication

More recently, studies have demonstrated that septoplasty for revision and the time between initial surgery and

can be performed safely in select pediatric patients with revision surgery was noted.

little risk of long-term facial deformity (1,6-11). Besides In total, 196 patients were identified as meeting inclusion

the benefits of enhanced nasal function, improvements in criteria. Two patients were lost to follow-up, and thus were

quality-of-life have been reported in the pediatric population excluded from the analysis. The total cohort of 194 patients

(12,13). Authors have used this data to advocate for early was divided into two smaller cohorts, an older cohort

corrective surgery to provide harmonious growth and prevent consisting of patients between 14 and 18 years old at the

craniofacial sequelae of mouth breathing (5,6). Some studies time of surgery and a younger cohort consisting of patients

have suggested that septal surgery is safe in children as under the age of 14 at the time of surgery. The age cutoff

young as 6-year-old, and may even be considered in neonates was selected based on the average age at completion of the

if severe airway obstruction is present (2,4). When the nasofacial growth spurt, which has been shown to be 13.1 in

procedure is deemed necessary, a conservative approach to girls and 14.7 in boys (15).

cartilage scoring and resection is thought to avoid disruption

of the primary nasal and midface growth centers, and thus

Statistical analysis

prevent the need for revision surgery later in life (5,14).

A majority of the published studies that have shown Student’s t-tests were performed to evaluate for differences

safety benefit are small, retrospective trials involving fewer between the older cohort and younger cohort with P values

than 50 patients (4). As such, the purpose of this study <0.05 considered as statistically significant.

is to review the long-term outcomes of a large cohort of

pediatric patients who underwent nasal septoplasty at a

IRB approval

tertiary children’s hospital. These outcomes of interest

include complications and need for revision surgery. To The study was conducted in accordance with the

the best of our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was

study published in the literature, and the first to compare approved by the institutional review board (00000568),

outcomes of septoplasty patients under the age of 14 to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and individual consent for

those 14 years and older. this retrospective analysis was waived.

We present the following article in accordance with the

STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.

Results

org/10.21037/tp-21-359).

Of the 194 septoplasty patients, 130 (67%) were male, and

64 (33%) were female. Mean age was 14.6 years (0–18 years)

Methods

for the total cohort, with a mean of 15.9 years in the older

A retrospective chart review was performed, examining cohort and 10.6 years in the younger cohort. Mean follow-up

medical records for all patients who received nasal septoplasty was 629 days (~21 months) after surgery with a range of 4 to

without adjunctive surgery at Nationwide Children’s Hospital 3,101 days. As expected, mean follow-up was significantly

in Columbus, Ohio between October 2009 and September longer in the younger cohort compared to the older cohort

2016. Institution review board approval was obtained as these younger patients were followed through puberty to

prior to study initiation. Patients who were 0 to 18 years monitor appropriate nasal growth (820 vs. 545 days, P=0.01).

of age at the time of surgery and underwent septoplasty Overall, the most common surgical indication was airway

for deviated nasal septum were included in the analysis. obstruction (76%) followed by a documented history of

Patients included those evaluated by otolaryngology or traumatic deformity (12%) and finally, chronic sinusitis

plastic surgery as the primary team involved in the patient’s (11%). The distribution of age at surgery for the total

© Translational Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Transl Pediatr 2021;10(11):2883-2887 | https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tp-21-359

Translational Pediatrics, Vol 10, No 11 November 2021 2885

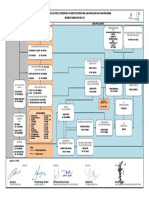

Patient age at time of nasal septoplasty

40

35

30

Number of patients

25

20

15

10

5

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

Age at time of surgery

Figure 1 Patient age at time of initial nasal septoplasty.

Table 1 Outcomes for total cohort, patients under 14 years, and patients 14 years or older

Patient details Total Cohort Younger Cohort Older Cohort P-value

Total number of patients 194 50 144

Mean age 14.6 10.6 15.9

Number of patients with revision septoplasty 13 (6.7%) 7 (14.0%) 6 (4.2%) 0.02

Perforation 1 (0.52%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.69%) 0.56

Epistaxis 24 (12.4%) 6 (12.0%) 18 (12.5%) 0.93

Septal hematoma 0 0 0 n/a

Mean follow-up (days) 629 820 545 0.01

Statistical analysis was performed to assess differences between patients under 14 years and 14 years or older. Significantly more

patients required revision septoplasty in the younger group, which also had a significantly longer follow-up. n/a, not applicable.

cohort is shown in Figure 1. cohort, indications included 3 for airway obstruction, 2 for

A comparison of outcomes between the older and sinus issues, and 1 for trauma. Mean duration of time from

younger cohorts is summarized in Table 1. A higher number original septoplasty to revision septoplasty was 1,094 days

of patients were found in the older cohort compared to (~36 months) with a range of 119 days to 3,096 days

the younger cohort (144 vs. 50). Thirteen patients (6.7%) (Figure 2).

required revision septoplasty. Seven patients required revision

septoplasty in the younger cohort compared to 6 patients

Discussion

in the older cohort. The percentage of patients requiring

revision septoplasty in the younger cohort was significantly We present long-term outcomes for the largest cohort of

higher than the percentage of patients requiring revision pediatric nasal septoplasty patients to date. Upon review

septoplasty in the older cohort (14.0% vs. 4.2%, P=0.02). of the literature, the next largest study discovered was a

No significant differences were found when comparing retrospective review that included 157 patients between 4 and

complications of perforation and epistaxis between the 16 years of age (6). In this study, we included 194 patients

younger and older cohorts (P>0.05), and no patient suffered with an age range of 0–18 years. Only three prospective

from a septal hematoma complication in the entire cohort. studies were discovered; one involved examination of acoustic

Of the 7 patients who required revision surgery in the rhinometries of 26 pediatric septoplasty patients (9), and two

younger cohort, 6 were due to airway obstruction and 1 examined quality of life outcomes with 35 and 28 patients

was due to development of synechiae. In comparison, of included in each study (13).

the 6 patients who required revision surgery in the older Our data indicates that septoplasty performed in patients

© Translational Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Transl Pediatr 2021;10(11):2883-2887 | https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tp-21-359

2886 Bishop et al. Pediatric nasal septoplasty outcomes

Age of patients that required revision septoplasty

3

Number of patients

2

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

Age at time of initial septoplasty

Figure 2 Number of patients requiring revision surgeries per age.

under the age of 14 years is associated with a higher rate of documented. This would correlate with surgical indications

revision septoplasty when compared to those performed in reported in a study of 54 pediatric corrective nasal surgery

children 14 years and older. In our cohort, 14% of children patients in which the most common indications listed

under 14 required a revision septoplasty. This is in contrast for surgery were posttraumatic deformities (67%) and

with the findings of a recent retrospective review of 43 airway obstruction (89%) with 28% reporting severe nasal

preadolescent children (defined as males <16 years, females obstruction without documented trauma (1).

<14 years) who received septoplasty that found that 0 of these Limitations of this study include those inherent to

patients required revision procedures (1). Other published retrospective analyses and potential variances in the younger

studies report similarly favorable long-term outcomes in and older study groups. In addition, long-term quality of life

this population (4,5). Similarly, a review of pediatric nasal outcomes were not measured. While the age demarcation

surgery has demonstrated that conservative and limited nasal in this study was chosen based on the pubertal transition,

surgery with careful preservation of septal structure may be significant variation in anatomy and growth may be seen

safely performed in the pediatric population with little long- between patients within the younger group. To address

term impact on nasofacial growth (16). Although pediatric these differences, further research may seek to include

septoplasty may have significant benefit, our results suggest further stratification by age. Additional research may aim

that septoplasty performed in patients under the age of 14 to include a multivariate analysis of long-term surgical and

years carries a significant risk for the need for revision surgery. quality of life outcomes stratified by type of septoplasty,

There were no significant differences in the rates of surgical indication, or severity of septal deviation.

perforation or epistaxis. However, epistaxis was reported

during the follow-up period in approximately 12% of patients

Conclusions

in both groups, as well as in the total cohort. Postoperative

epistaxis was defined as the presence of bleeding greater than To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective

expected post-operatively that was identified in the medical study examining septoplasty outcomes in the pediatric

record in any medical encounter during the follow-up period. population. Septoplasty patients under the age of 14 years

As only one patient suffered a septal perforation and no require more revision surgeries compared to older patients.

septal hematomas were seen in the total cohort, it is difficult These results contrast with the increasingly popular notion

to draw a meaningful relationship between the incidence of that pediatric nasal septoplasty can be performed safely

these complications and patient age. Although the number of at a young age without negative consequences. Future

revision surgeries carries more clinical weight, it is important prospective studies are required to further elucidate the

to note the lack of differences in complications between long-term effects of pediatric nasal septoplasty.

groups as this is an important contribution to quality of life.

In our cohort, a large majority of surgical indications

Acknowledgments

were classified as “airway obstruction” compared to trauma

and sinus issues. In reality, some patients with surgical Funding: This project is supported by intramural funding

indications classified as “airway obstruction” likely had from the Department of Otolaryngology at Nationwide

remote history of trauma earlier in childhood that was not Children’s Hospital and the Center for Surgical Outcomes

© Translational Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Transl Pediatr 2021;10(11):2883-2887 | https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tp-21-359

Translational Pediatrics, Vol 10, No 11 November 2021 2887

Research at The Research Institute at Nationwide Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012;76:1078-81.

Children’s Hospital. 3. Healy GB. An approach to the nasal septum in children.

Laryngoscope 1986;96:1239-42.

4. Cingi C, Muluk NB, Ulusoy S, et al. Septoplasty in

Footnote

children. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2016;30:e42-7.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the 5. Gary CC. Pediatric nasal surgery: timing and technique.

STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;25:286-90.

org/10.21037/tp-21-359 6. Maniglia CP, Maniglia JV. Rhinoseptoplasty in children.

Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2017;83:416-9.

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://dx.doi. 7. Tasca I, Compadretti GC. Nasal growth after pediatric

org/10.21037/tp-21-359 septoplasty at long-term follow-up. Am J Rhinol Allergy

2011;25:e7-12.

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/ 8. Dispenza F, Saraniti C, Sciandra D, et al. Management

tp-21-359 of naso-septal deformity in childhood: long-term results.

Auris Nasus Larynx 2009;36:665-70.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE 9. Can IH, Ceylan Ka, Bayiz U, et al. Acoustic rhinometry

uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi. in the objective evaluation of childhood septoplasties. Int J

org/10.21037/tp-21-359). CAE is a consultant for Smith Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2005;69:445-8.

and Nephew. The other authors have no conflicts of interest 10. El-Hakim H, Crysdale WS, Abdollel M, et al. A study

to declare. of anthropometric measures before and after external

septoplasty in children: a preliminary study. Arch

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;127:1362-6.

aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related 11. Walker PJ, Crysdale WS, Farkas LG. External

to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work septorhinoplasty in children: Outcome and effect on

are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study growth of septal excision and reimplantation. Arch

was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1993;119:984-9.

Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by 12. Lee VS, Gold RM, Parikh SR. Short-term quality of life

the institutional review board (00000568), Nationwide outcomes following pediatric septoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol

Children’s Hospital, and individual consent for this 2017;137:293-6.

retrospective analysis was waived. 13. Yilmaz MS, Guven M, Akidil O, et al. Does septoplasty

improve the quality of life in children? Int J Pediatr

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78:1274-6.

distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons 14. Funamura JL, Sykes JM. Pediatric septorhinoplasty. Facial

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International Plast Surg Clin North Am 2014;22:503-8.

License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non- 15. van der Heijden P, Korsten-Meijer AG, van der Laan BF,

commercial replication and distribution of the article with et al. Nasal growth and maturation age in adolescents:

the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the a systematic review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

original work is properly cited (including links to both the 2008;134:1288-93.

formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). 16. Johnson MD. Management of Pediatric Nasal Surgery

See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. (Rhinoplasty). Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am

2017;25:211-21.

References

1. Adil E, Goyal N, Fedok FG. Corrective nasal surgery in the Cite this article as: Bishop R, Sethia R, Allen D, Elmaraghy

younger patient. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 2014;16:176-82. CA. Pediatric nasal septoplasty outcomes. Transl Pediatr

2. Lawrence R. Pediatric septoplasy: a review of the literature. 2021;10(11):2883-2887. doi: 10.21037/tp-21-359

© Translational Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Transl Pediatr 2021;10(11):2883-2887 | https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tp-21-359

You might also like

- Exercise Physiology Powers PDFDocument2 pagesExercise Physiology Powers PDFLuke0% (10)

- Chapter 1 Describe Artificial Intelligence Workloads and Considerations - Exam Ref AI-900 Microsoft Azure AI FundamentalsDocument24 pagesChapter 1 Describe Artificial Intelligence Workloads and Considerations - Exam Ref AI-900 Microsoft Azure AI FundamentalsRishita ReddyNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ijporl 2020 110139Document28 pages10 1016@j Ijporl 2020 110139Gregoria choque floresNo ratings yet

- Otolaryngology Service Usage in Children With Cleft PalateDocument4 pagesOtolaryngology Service Usage in Children With Cleft PalateCatherine nOCUANo ratings yet

- Effect of Non-Surgical Maxillary Expansion On The Nasal Septum Deviation: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesEffect of Non-Surgical Maxillary Expansion On The Nasal Septum Deviation: A Systematic ReviewsaraNo ratings yet

- Effect of Aspiration On The Lungs in Children: A Comparison Using Chest Computed Tomography FindingsDocument7 pagesEffect of Aspiration On The Lungs in Children: A Comparison Using Chest Computed Tomography FindingsYuliaAntolisNo ratings yet

- Facial Soft TisuesDocument6 pagesFacial Soft TisuesMoni Garcia SantosNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in The Paediatric PopulationDocument6 pagesEnhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in The Paediatric PopulationkhalidNo ratings yet

- 2019 Effect of Maxillary Expansion and Protraction On The Oropharyngeal Airway in Individuals With Non Syndromic Cleft Palatae Wit or Without Cleft LipDocument23 pages2019 Effect of Maxillary Expansion and Protraction On The Oropharyngeal Airway in Individuals With Non Syndromic Cleft Palatae Wit or Without Cleft LipaprilandralekaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Malocclusion in Children With Sleep Disordered BreathingDocument4 pagesPrevalence of Malocclusion in Children With Sleep Disordered BreathingMu'taz ArmanNo ratings yet

- Abses SeptumDocument8 pagesAbses SeptumDian FahmiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures: Treatment Strategies According To Age - 13 Years of Experience in One Medical CenterDocument6 pagesPediatric Femoral Shaft Fractures: Treatment Strategies According To Age - 13 Years of Experience in One Medical CenterAnonymous 1EQutBNo ratings yet

- AgeDocument4 pagesAgeNah LaNo ratings yet

- s12887 017 0870 4Document8 pagess12887 017 0870 4Gulsana HashmiNo ratings yet

- Rme Efek AnakDocument10 pagesRme Efek AnakSiwi HadjarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Tympanoplasty: Factors Affecting Success: Aaron C. Lin and Anna H. MessnerDocument5 pagesPediatric Tympanoplasty: Factors Affecting Success: Aaron C. Lin and Anna H. MessnerAcoet MiezarNo ratings yet

- 10 1186@s12891-0dnfkfk8 PDFDocument6 pages10 1186@s12891-0dnfkfk8 PDFJGunar VasquezNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Maxillary Dental Arch After Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Patients With Unilateral Complete Cleft Lip and PalateDocument11 pagesAnalysis of The Maxillary Dental Arch After Rapid Maxillary Expansion in Patients With Unilateral Complete Cleft Lip and PalateStefii GtzNo ratings yet

- ORTODONCIAchildren 10 00176Document11 pagesORTODONCIAchildren 10 00176EstreLLA ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Medoralv16 I4 p473Document5 pagesMedoralv16 I4 p473AbhinavNo ratings yet

- Dentofacial Characteristics of Oral Breathers in Different AgesDocument10 pagesDentofacial Characteristics of Oral Breathers in Different AgesAlejandro RuizNo ratings yet

- Factors Related To Microimplant Assisted Rapid PalDocument8 pagesFactors Related To Microimplant Assisted Rapid PalFernando Espada SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Alganabi2021 Article SurgicalSiteInfectionAfterOpenDocument9 pagesAlganabi2021 Article SurgicalSiteInfectionAfterOpenWahyudhy SajaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyLee제노No ratings yet

- JurnalDocument9 pagesJurnalNoraine Zainal AbidinNo ratings yet

- 2020 Pediatric Tracheostomy Decannulation Post Implementation of TQT Team and Decannulation ProtocolDocument9 pages2020 Pediatric Tracheostomy Decannulation Post Implementation of TQT Team and Decannulation ProtocolDavid Fabián Fernández CarmonaNo ratings yet

- Abtahi 2020Document9 pagesAbtahi 2020Rati Ramayani AbidinNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyAcoet MiezarNo ratings yet

- Effects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion On Upper Airway Volume: A Three-Dimensional Cone-Beam Computed Tomography StudyDocument7 pagesEffects of Rapid Maxillary Expansion On Upper Airway Volume: A Three-Dimensional Cone-Beam Computed Tomography StudyVishal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Jarefors2016 PDFDocument5 pagesJarefors2016 PDFBenjie LawNo ratings yet

- Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis at A TertiDocument7 pagesInfantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis at A TertiVașadi Razvan CristianNo ratings yet

- When Should Parapneumonic Pleural Effusions Be Drained in ChildrenDocument16 pagesWhen Should Parapneumonic Pleural Effusions Be Drained in ChildrenJHONATAN MATA ARANDANo ratings yet

- Tugas Akhir Blok 11 "Otitis Media": OlehDocument19 pagesTugas Akhir Blok 11 "Otitis Media": OlehSartika NapitupuluNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Reading OtologiDocument19 pagesJurnal Reading OtologiMuhammad gusti haryandiNo ratings yet

- Ferhm Effectiveness of Adenotonsillectomy Vs Watchful Waiting in Young ChildrenDocument17 pagesFerhm Effectiveness of Adenotonsillectomy Vs Watchful Waiting in Young Childrendanielesantos.202019No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Relative Position of Mandibular Foramen in Children As A Reference For Inferior AlveolDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Relative Position of Mandibular Foramen in Children As A Reference For Inferior AlveolCristi GaidurNo ratings yet

- Effects of Rapid Palatal Expansion On The Upper Airway SpaceDocument11 pagesEffects of Rapid Palatal Expansion On The Upper Airway SpacevenancioNo ratings yet

- Vanegmond2015 PDFDocument10 pagesVanegmond2015 PDFIntan AliNo ratings yet

- Chronic Effects of Pediatric Ear Infections On Postural StabilityDocument6 pagesChronic Effects of Pediatric Ear Infections On Postural StabilityFajar SutrisnaNo ratings yet

- Airway Volume Changes After Orthognathic Surgery in Patients With Down SyndromeDocument14 pagesAirway Volume Changes After Orthognathic Surgery in Patients With Down SyndrometamisatnamNo ratings yet

- Bmri2021 5550267Document13 pagesBmri2021 5550267Shahid ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Optimal Timing For Soave Primary Pull-Through in Short-SegmentDocument7 pagesOptimal Timing For Soave Primary Pull-Through in Short-SegmentNate MichalakNo ratings yet

- Disease KnowledgeDocument6 pagesDisease KnowledgeJaved IqbalNo ratings yet

- Growth Patterns and Overbite Depth Indicators of Long and Short Faces in Korean Adolescents: Revisited Through Mixed Effects AnalysisDocument22 pagesGrowth Patterns and Overbite Depth Indicators of Long and Short Faces in Korean Adolescents: Revisited Through Mixed Effects AnalysisBs PhuocNo ratings yet

- Respirador BucalDocument8 pagesRespirador Bucalyessenia armijosNo ratings yet

- Aboudara2009 PDFDocument12 pagesAboudara2009 PDFYsl OrtodonciaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Removable Partial Denture On Periodontal HealthDocument3 pagesEffect of Removable Partial Denture On Periodontal HealthAlex KwokNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0889540623002342 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0889540623002342 Mainjizx921No ratings yet

- Long-Term Follow Up of 103 Ankylosed Permanent Incisors Surgically Treated With Decoronation - A Retrospective Cohort StudyDocument7 pagesLong-Term Follow Up of 103 Ankylosed Permanent Incisors Surgically Treated With Decoronation - A Retrospective Cohort StudyAnaMariaCastroNo ratings yet

- Comparision of Orofacial Airway Dimensions in Subject With Different Breathing PatternDocument8 pagesComparision of Orofacial Airway Dimensions in Subject With Different Breathing PatternLudy Jiménez ValdiviaNo ratings yet

- Airway Management - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument7 pagesAirway Management - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfClarithq LengguNo ratings yet

- Otitis Media With Effusion - GuidelineDocument41 pagesOtitis Media With Effusion - GuidelineAurel OctavianNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0274657Document16 pagesJournal Pone 0274657Natalindah Jokiem Woecandra T. D.No ratings yet

- Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 2016 Rosenfeld S1 S41Document41 pagesOtolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 2016 Rosenfeld S1 S41Novy Sylvia Wardana100% (1)

- Follow UpDocument7 pagesFollow UpAnna PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Miiringotomi OMEDocument7 pagesMiiringotomi OMEamaliaNo ratings yet

- Kim 2010Document11 pagesKim 2010popsilviaizabellaNo ratings yet

- Jced 11 E947Document5 pagesJced 11 E947wafiqahNo ratings yet

- Art 1Document6 pagesArt 1Alvaro Jose Uribe TamaraNo ratings yet

- PARS Reader's Digest - July 2013 IssueDocument9 pagesPARS Reader's Digest - July 2013 Issueinfo8673No ratings yet

- Resection and Reconstruction of Head & Neck CancersFrom EverandResection and Reconstruction of Head & Neck CancersMing-Huei ChengNo ratings yet

- Ibps Clerk Prelims Booster - English-Day-4Document10 pagesIbps Clerk Prelims Booster - English-Day-4Ranga Harsha VardhanNo ratings yet

- Dieta MasculinoDocument4 pagesDieta MasculinoEduardo SpencerNo ratings yet

- MSDS Cetirizine HCLDocument6 pagesMSDS Cetirizine HCLFitriani SyawaliaNo ratings yet

- Sensory Organs: Medical Surgical NursingDocument17 pagesSensory Organs: Medical Surgical NursingHoney PrasadNo ratings yet

- Sas 19-21 AnswersDocument5 pagesSas 19-21 AnswersJilkiah Mae Alfoja Campomanes100% (5)

- Psych Meds Booster Nov 2022 PnleDocument11 pagesPsych Meds Booster Nov 2022 PnleDarwin DerracoNo ratings yet

- DRUG Recommendation System Based On Sentiment Analysis of DRUG Reviews Using Machine LearningDocument5 pagesDRUG Recommendation System Based On Sentiment Analysis of DRUG Reviews Using Machine Learningkmp pssrNo ratings yet

- Ricardo G. Sigua: Kristine Joy Halili Harolyn Manansala PSYCH 1-A Joshua Kale Lozano Ray Carl GarciaDocument8 pagesRicardo G. Sigua: Kristine Joy Halili Harolyn Manansala PSYCH 1-A Joshua Kale Lozano Ray Carl GarciaDonna Rose Sanchez FegiNo ratings yet

- CascadaServMan RODocument18 pagesCascadaServMan ROSiddarth100% (1)

- Harm Reduction and Substance UseDocument1 pageHarm Reduction and Substance UseLucas LiberatoNo ratings yet

- Roma Honors ThesisDocument45 pagesRoma Honors ThesisVan LopezNo ratings yet

- Disciplines and Ideas in The Applied Social Sciences (DIASS)Document4 pagesDisciplines and Ideas in The Applied Social Sciences (DIASS)Josielyn AgustinNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat ProlanisDocument18 pagesDaftar Obat ProlanisMas EmNo ratings yet

- NDECC Practical Guide - V16 - Modified 11 24 2023 - Effective 01 09 2024 1Document20 pagesNDECC Practical Guide - V16 - Modified 11 24 2023 - Effective 01 09 2024 1Chitran lancerNo ratings yet

- Hadzic's Peripheral Nerve Blocks and Anatomy For Ultrasound Guided Regional Anesthesia (New York School of Regional Anesthesia) PDF DownloadDocument3 pagesHadzic's Peripheral Nerve Blocks and Anatomy For Ultrasound Guided Regional Anesthesia (New York School of Regional Anesthesia) PDF Downloadhellena buks33% (3)

- Reverse Inflammation Naturally: Alternative Treatments For Autoimmune Disorders, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Fibromyalgia, Metabolic Syndrome, Allergies, Thyroiditis, Eczema and More. - Michelle HondaDocument5 pagesReverse Inflammation Naturally: Alternative Treatments For Autoimmune Disorders, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Fibromyalgia, Metabolic Syndrome, Allergies, Thyroiditis, Eczema and More. - Michelle HondalycubefuNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics 2023 FINALDocument56 pagesMedical Ethics 2023 FINALBelinda ELISHANo ratings yet

- Wife Cheated On Me Part 7Document10 pagesWife Cheated On Me Part 7draculaa9No ratings yet

- Dossier d4 Form - 0Document4 pagesDossier d4 Form - 0chai min chooNo ratings yet

- Edss Csulb Physical Education Lesson Plan ColorDocument16 pagesEdss Csulb Physical Education Lesson Plan Colorapi-511737397No ratings yet

- Go FL DMT and Ee A 40164421357Document3 pagesGo FL DMT and Ee A 40164421357कुँ. विकास सिंह राजावतNo ratings yet

- Master Class PDFDocument5 pagesMaster Class PDFNitin GadhiyaNo ratings yet

- ERP Comm Line WII Lematang Add WakatekDocument1 pageERP Comm Line WII Lematang Add WakatekAcunNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument7 pagesNutritionNadia ShadNo ratings yet

- Draw AnatomyDocument117 pagesDraw Anatomydsa100% (1)

- Love in The Dark by Khai HaraDocument454 pagesLove in The Dark by Khai Haravitoriakslima18No ratings yet

- 8607Document10 pages8607Sufyan KhanNo ratings yet

- Reflection AcrobaticsDocument1 pageReflection Acrobaticsjay lure baguioNo ratings yet