Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stuck in Traffic

Stuck in Traffic

Uploaded by

Qiraat “Summaiya” HaqCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stuck in Traffic

Stuck in Traffic

Uploaded by

Qiraat “Summaiya” HaqCopyright:

Available Formats

Stuck in traffic

America. (Aug. 1, 2016) by Jim McDermott

Traffic is to Los Angeles what dangerous animals are to Australia--something visitors

fixate on and locals mostly ignore. "Do you know it took me over an hour to get here?"

tourists ask, eyes crazed and glassy after their first foray in the SoCal stop and go.

"Also, why is Hollywood so gross?" (Seriously, Mayor Garcetti: Why?)

The issue of traffic congestion here is undeniable. According to a recent national study,

Angelenos spend an average of 81 hours a year stuck in traffic, the worst rate in the

country. (San Francisco and Washington, D.C., tied for second at 75 hours.) But among

most locals the snarls barely rate a mention. Between a heavy medication of podcasts

and satellite radio shows and a religious observance to Waze, the community-fed traffic

and navigation app, Angelenos simply cope.

Still, faced with the growing consequences of climate change, like the states never-

ending drought, the city's overwhelming dependence on automobiles would seem a

serious concern. Once upon a time the county had over 1,000 miles of electric streetcar

lines. But a combination of rising costs and the machinations of car companies anxious

to eliminate competition eventually destroyed the service.

Today L.A. County actually transports 1.3 million people a day by public transit, second

in the United States only to New York, but with little of the efficiency or convenience

offered in other major cities. Over the last decade the county has invested $9 billion into

expanding its system. Yet over the same period, transit usage has diminished by more

than 10 percent.

The problem, explains Brian Taylor, director of U.C.L.A.'s Institute of Transportation

Studies, lies in the city's history. Los Angeles is most often compared to places like New

York or Chicago. But, Taylor points out, those cities developed their transit networks

before the invention of the automobile. This led to denser urban areas that play to the

strength of public transport--"moving a lot of people in the same direction at the same

time." As a result New York City today carries 38 percent of the entire country's transit

riders.

Los Angeles, on the other hand, like many other American cities and most suburbs,

developed largely after World War II. As such it "grew up around the automobile," says

Taylor. Ready access to transportation was assumed; space, not density, was of

highest value.

This difference complicates conversation around public transportation today in ways

that are not always obvious. Even when the problem of congestion is acknowledged,

the size and population spread of Los Angeles create significant obstacles to efficient

transportation. "Public transit trips take about twice as long as driving," notes Taylor.

When a commute by car can already take upwards of an hour each way, for many

people the public transit option is no option at all.

And simply investing more money in such a geographically challenged system has little

impact. For those with the means, it doesn't matter if the city schedules more buses or

offers newer, safer trains if the travel time remains basically the same. Yet cities

continue to push massive funding packages--including in Los Angeles a proposed $120

billion over the next 40 years--both because it appears to address the problem and

because many erroneously think, How could more resources not help?

As Taylor sees it, rather than spreading transit resources over the entire city out of a

desire to seem fair, Los Angeles should focus its efforts on areas and populations who

actually need and use rapid transit services. "We're spending a lot of money on new

commuter oriented services," he explains, but "they aren't returning a lot in ridership."

But what about the congestion? What about all the cars? Taylor says they're largely

here to stay. "Private vehicles are likely to play a central role in mobility in all but the

very densest cities in the country."

If that's the case, alongside the shiny new train line that links Santa Monica to

downtown L.A.--but which takes as long to reach downtown as the old line did 60 years

ago--county and state government should start thinking about public transit in broader

terms. They might consider diverting some of their proposed billions to research and

rebates on hybrids and electric cars.

Investing in longer National Public Radio programs couldn't hurt, either.

JIM McDERMOTT, SJ., a screenwriter, is America's Los Angeles correspondent.

Source Citation (MLA 8th Edition)

Mcdermott, Jim. "Stuck in traffic." America, 1 Aug. 2016, p. 11. Opposing Viewpoints In Context,

http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A460324838/OVIC?u=cclc_el&sid=OVIC&xid=813f3151. Accessed 26

June 2018.

You might also like

- Trains, Buses, People, Second Edition: An Opinionated Atlas of US and Canadian TransitFrom EverandTrains, Buses, People, Second Edition: An Opinionated Atlas of US and Canadian TransitRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 31 SecretsDocument16 pages31 Secretsaswath698100% (3)

- The Perception of Commuters in Bulacan State University College of Education About The Construction of High Speed Railway System From Malolos Bulacan To TutubanDocument8 pagesThe Perception of Commuters in Bulacan State University College of Education About The Construction of High Speed Railway System From Malolos Bulacan To TutubanLouie Renz M. JovenNo ratings yet

- Still Stuck in Traffic - Unknown PDFDocument472 pagesStill Stuck in Traffic - Unknown PDFBhuvana Vignaesh67% (3)

- The New Transit Town: Best Practices In Transit-Oriented DevelopmentFrom EverandThe New Transit Town: Best Practices In Transit-Oriented DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- At HSR The Competiveness Advantage Is Dumb Star This Evidence-This Is The Reason Why Their Econ Advantage Never Going To Solve. O'Toole 09Document3 pagesAt HSR The Competiveness Advantage Is Dumb Star This Evidence-This Is The Reason Why Their Econ Advantage Never Going To Solve. O'Toole 09AtraSicariusNo ratings yet

- Allendale Makes Our City A Better PlaceDocument3 pagesAllendale Makes Our City A Better Placekmitchell@mhsmarchitectsNo ratings yet

- Highway Aggravation: The Case For Privatizing The Highways, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument19 pagesHighway Aggravation: The Case For Privatizing The Highways, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- The Charlotte Blue Line Extension: Bringing More Than Just TransportationDocument11 pagesThe Charlotte Blue Line Extension: Bringing More Than Just TransportationElissa MillerNo ratings yet

- ISTEA: A Poisonous Brew For American Cities, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument54 pagesISTEA: A Poisonous Brew For American Cities, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Literature Review - FinalDocument10 pagesLiterature Review - Finalapi-26026923850% (2)

- The Charlotte Blue Line Extension: Bringing More Than Just TransportationDocument11 pagesThe Charlotte Blue Line Extension: Bringing More Than Just TransportationElissa MillerNo ratings yet

- ContentServer AspDocument3 pagesContentServer AspPornthita SuwannachairobNo ratings yet

- Gridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What To Do About ItFrom EverandGridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What To Do About ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Bus System (Ixlos Ta'lim)Document6 pagesBus System (Ixlos Ta'lim)Azimov ShoxruxNo ratings yet

- MTA Fare Hike Testimony 12.10Document3 pagesMTA Fare Hike Testimony 12.10Evan WeinbergNo ratings yet

- Access 40Document44 pagesAccess 40jhonsifuentesNo ratings yet

- Congestion Pricing Coalition Letter To Governor HochulDocument10 pagesCongestion Pricing Coalition Letter To Governor HochulrobbinscmNo ratings yet

- Final PaperDocument20 pagesFinal Paperapi-334976672No ratings yet

- Socials EssayDocument4 pagesSocials Essaytawexe4661No ratings yet

- METROFAIL TROPIC Magazine, September 15, 1985, by JOHN DORSCHNER Herald Staff WriterDocument11 pagesMETROFAIL TROPIC Magazine, September 15, 1985, by JOHN DORSCHNER Herald Staff WriterRandom Pixels blogNo ratings yet

- Cars and Their EnemiesDocument6 pagesCars and Their EnemiesJustinNo ratings yet

- ULI NY-PCAC MTA Capital Program ReportDocument91 pagesULI NY-PCAC MTA Capital Program Reportahawkins8223No ratings yet

- Advantages of Public TransportDocument5 pagesAdvantages of Public TransportLA KKPNo ratings yet

- Do Androids Dream of Electric Cars?: Public Transit in the Age of Google, Uber, and Elon MuskFrom EverandDo Androids Dream of Electric Cars?: Public Transit in the Age of Google, Uber, and Elon MuskNo ratings yet

- Light-Rail Transit: Myths and Realities: Property Values and DevelopmentDocument5 pagesLight-Rail Transit: Myths and Realities: Property Values and DevelopmentMark Israel DirectoNo ratings yet

- © Zaher massaad-LUFGIIDocument11 pages© Zaher massaad-LUFGIImichelawad88No ratings yet

- 1937 Traffic Survey Los Angeles Metropolitan AreaDocument63 pages1937 Traffic Survey Los Angeles Metropolitan AreaJason Bentley100% (1)

- Critical Issues 06Document16 pagesCritical Issues 06Kamal MirzaNo ratings yet

- Uwrt 1103 Defense PaperDocument6 pagesUwrt 1103 Defense Paperapi-354601375No ratings yet

- Case Neg Updates (Sdi)Document176 pagesCase Neg Updates (Sdi)sidney_liNo ratings yet

- TransitCenter's "Stranded" ReportDocument19 pagesTransitCenter's "Stranded" ReportGersh KuntzmanNo ratings yet

- Cities Want To Return To Prepandemic Life. One Obstacle: Transit CrimeDocument10 pagesCities Want To Return To Prepandemic Life. One Obstacle: Transit CrimefreebookguyNo ratings yet

- Socials EssayDocument4 pagesSocials Essaytawexe4661No ratings yet

- Paper 1 Annotated BibliographyDocument3 pagesPaper 1 Annotated Bibliographyapi-272849846No ratings yet

- DC Streetcar Final PaperDocument21 pagesDC Streetcar Final PaperElissa SilvermanNo ratings yet

- First Is InherencyDocument18 pagesFirst Is InherencybeverskiNo ratings yet

- How Politics and Bad Decisions Starved New York's Subways - The New York TimesDocument21 pagesHow Politics and Bad Decisions Starved New York's Subways - The New York TimesAngus SadpetNo ratings yet

- Thesis 09358154299Document10 pagesThesis 09358154299MarkLesterEstrellaMabagosNo ratings yet

- Riders Alliance Transit Safety PlanDocument12 pagesRiders Alliance Transit Safety PlanGersh KuntzmanNo ratings yet

- Coherence and CohesionDocument3 pagesCoherence and CohesionNidia Esmeralda RODRIGUEZ EUGENIONo ratings yet

- Test 5bDocument3 pagesTest 5bHong AnhNo ratings yet

- Network Review: New York City: By: Andrew ThompsonDocument14 pagesNetwork Review: New York City: By: Andrew ThompsonAndrew Thelittleenginethatcould ThompsonNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Private Sector Financing of Transportation InfrastructureDocument459 pagesAn Introduction To Private Sector Financing of Transportation InfrastructureBob DiamondNo ratings yet

- Eastfield Station BrochureDocument16 pagesEastfield Station BrochureJeff ReamNo ratings yet

- PrefaceDocument1 pagePrefaceSang-Jin LimNo ratings yet

- Mobility in MedellinDocument16 pagesMobility in MedellindezistehwickedNo ratings yet

- Mcgraw-Hill'S Handbook of Transportation Engineering: Chapter 12. Traffic CongestionDocument30 pagesMcgraw-Hill'S Handbook of Transportation Engineering: Chapter 12. Traffic Congestiondave4359No ratings yet

- Life and Death of Urban HighwaysDocument44 pagesLife and Death of Urban HighwaysJulio Paredes EslavaNo ratings yet

- Public Transportation Policy ThesisDocument19 pagesPublic Transportation Policy ThesisAri EngberNo ratings yet

- How Much Public Space Does A City Need - Next CityDocument7 pagesHow Much Public Space Does A City Need - Next CityCesar Arango GomezNo ratings yet

- Dsalinas2-44777-2022-03-28 12-30-37-pmDocument6 pagesDsalinas2-44777-2022-03-28 12-30-37-pmapi-640740774No ratings yet

- Life and Death of Urban HighwaysDocument44 pagesLife and Death of Urban HighwaysWagner Tamanaha100% (1)

- ProQuestDocuments 2022 06 08Document3 pagesProQuestDocuments 2022 06 08sajjadNo ratings yet

- Lancaster City Walkability StudyDocument131 pagesLancaster City Walkability StudyLNP MEDIA GROUP, Inc.100% (1)

- S, S, S: T I P T T C: Ubways Trikes AND Lowdowns HE Mpacts of Ublic Ransit On Raffic OngestionDocument52 pagesS, S, S: T I P T T C: Ubways Trikes AND Lowdowns HE Mpacts of Ublic Ransit On Raffic OngestionBlaine KuehnertNo ratings yet

- Leach FinalreportDocument11 pagesLeach Finalreportapi-235716692No ratings yet

- Filling The Gaps: COMMUTE and The Fight For Transit Equity in New York CityDocument20 pagesFilling The Gaps: COMMUTE and The Fight For Transit Equity in New York CityApplied Research CenterNo ratings yet

- Metro Bridge Report EMBARGOEDDocument16 pagesMetro Bridge Report EMBARGOEDjspectorNo ratings yet

- Inherency Status Quo Solves Obama Is Pushing For HSR. TIME, 2/2011Document15 pagesInherency Status Quo Solves Obama Is Pushing For HSR. TIME, 2/2011Sam SchwartzNo ratings yet

- The Cost of AirDocument4 pagesThe Cost of Airapi-238545738No ratings yet

- Around The World BooksDocument3 pagesAround The World BooksAdiAri RosiuNo ratings yet

- VW CB SegmentationDocument9 pagesVW CB SegmentationRazvan Iliescu100% (1)

- 175-Article Text-631-1-10-20210624Document9 pages175-Article Text-631-1-10-20210624Fais FaisNo ratings yet

- Issuu PDF Download: Preliminares para Ser MasonDocument17 pagesIssuu PDF Download: Preliminares para Ser MasonMagNo ratings yet

- Airbus CaseDocument7 pagesAirbus Caseclarabordas.lNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Smart MeteringDocument34 pagesFundamentals of Smart MeteringSUDDHA CHAKRABARTYNo ratings yet

- FjVpesh7RWSUBg0hI2ie 5 Powerful Design ElementsDocument7 pagesFjVpesh7RWSUBg0hI2ie 5 Powerful Design ElementsCraigNo ratings yet

- Credit Card StatementDocument4 pagesCredit Card Statementirshad khanNo ratings yet

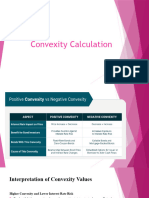

- Convexity CalculationDocument7 pagesConvexity CalculationRabeya AktarNo ratings yet

- Agriculture MatterDocument27 pagesAgriculture MatterksbbsNo ratings yet

- SR - Q1 2021 Cattle Situation ReportDocument6 pagesSR - Q1 2021 Cattle Situation ReportPhilip Blair OngNo ratings yet

- Session 3 - JournalDocument27 pagesSession 3 - JournalanandakumarNo ratings yet

- Cosasco RBS - Rbsa Retriever MaintenanceDocument44 pagesCosasco RBS - Rbsa Retriever MaintenanceSeip SEIPNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast The Texture and Melody of The Miles Davis, Poulenc and BrahmsDocument3 pagesCompare and Contrast The Texture and Melody of The Miles Davis, Poulenc and BrahmsWinston 葉永隆 DiepNo ratings yet

- Philippine Declaration of IndependenceDocument5 pagesPhilippine Declaration of IndependenceZheenaNo ratings yet

- Activity For MusicDocument3 pagesActivity For MusicRheian Karl Limson AguadoNo ratings yet

- 2022 10 30qrDocument177 pages2022 10 30qrB8Inggit KartikaDiniNo ratings yet

- Dowry Laws in IndiaDocument20 pagesDowry Laws in Indiasanket jamuarNo ratings yet

- High Resolution Satellite Image Analysis and Rapid 3D Model Extraction For Urban Change DetectionDocument213 pagesHigh Resolution Satellite Image Analysis and Rapid 3D Model Extraction For Urban Change Detectionta peiNo ratings yet

- Astm A572Document4 pagesAstm A572Kaushal KishoreNo ratings yet

- RA 10168 Related LitsDocument7 pagesRA 10168 Related LitsJade Belen ZaragozaNo ratings yet

- PrintDocument1 pagePrintStephanie Michelle BolesNo ratings yet

- SOLARIS CommandsDocument34 pagesSOLARIS CommandsYahya LateefNo ratings yet

- B5 21-30 Paper 3 Cyberbullying Via Social Media v2 210318Document10 pagesB5 21-30 Paper 3 Cyberbullying Via Social Media v2 210318Sanin SaninNo ratings yet

- Schumann ResonancesDocument11 pagesSchumann ResonancespuretrustNo ratings yet

- Aakash Rank Booster Test Series For NEET-2020Document14 pagesAakash Rank Booster Test Series For NEET-2020Anish TakshakNo ratings yet

- Family Law-IiDocument7 pagesFamily Law-IiDiya Pande0% (1)

- Practical Research Module 1.fDocument20 pagesPractical Research Module 1.fDianne Masapol89% (28)