Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nearshoring and Potential Trade

Nearshoring and Potential Trade

Uploaded by

Rodolfo RivadeneyraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nearshoring and Potential Trade

Nearshoring and Potential Trade

Uploaded by

Rodolfo RivadeneyraCopyright:

Available Formats

MOODY’S

ANALYTICS

ANALYSIS

APRIL 2024 Nearshoring and Potential Trade

Triangulation

Prepared by

Alfredo Coutino The proliferation of more restrictive tariff policies along with emerging geopolitical

Alfredo.Coutino@moodys.com

Director events is producing a reconfiguration of global supply chains with the relocation of

plants and investments to countries with geographical advantages and more market-

Contact Us friendly environments. This relocation process, called nearshoring or friendshoring, is

Email

happening already in North America and is greatly benefiting the area thanks to the

helpeconomy@moodys.com

advantages provided by the trilateral trade agreement among the U.S., Mexico and

U.S./Canada Canada. Mexico is becoming the main destination of nearshoring in North America.

+1.866.275.3266

EMEA Nearshoring is certainly producing benefits, but it is also generating inconveniences,

+44.20.7772.5454 (London)

+420.234.747.505 (Prague) as it attracts producers from other regions to Mexico with the purpose of accessing the

Asia/Pacific

U.S. market—particularly Asian producers subject to higher U.S. tariffs and

+852.3551.3077 restrictions. This is triggering concerns in the U.S. about the possibility of triangulation

All Others of China’s imports to the U.S. via Mexico. By analyzing data on the volume of

+1.610.235.5299

Mexico’s imports from China and Mexico’s exports of manufacturing products to the

Web U.S., we can gain some insight about this potential trade triangulation. Our

www.economy.com

www.moodysanalytics.com examination does not rule out the possibility that some products exported to the U.S.

from Mexico are being generated outside Mexico.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 1

Nearshoring and Potential Trade

Triangulation

BY ALFREDO COUTINO

T

he proliferation of more restrictive tariff policies along with emerging geopolitical events is producing a

reconfiguration of global supply chains with the relocation of plants and investments to countries with

geographical advantages and more market-friendly environments. This relocation process, called

nearshoring or friendshoring, is happening already in North America and is greatly benefiting the area thanks to

the advantages provided by the trilateral trade agreement among the U.S., Mexico and Canada. Mexico is

becoming the main destination of nearshoring in North America.

Nearshoring is certainly producing benefits, but it is also generating inconveniences, as it attracts producers

from other regions to Mexico with the purpose of accessing the U.S. market—particularly Asian producers

subject to higher U.S. tariffs and restrictions. This is triggering concerns in the U.S. about the possibility of

triangulation of China’s imports to the U.S. via Mexico. By analyzing data on the volume of Mexico’s imports

from China and Mexico’s exports of manufacturing products to the U.S., we can gain some insight about this

potential trade triangulation. Our examination does not rule out the possibility that some products exported to

the U.S. from Mexico are being generated outside Mexico.

Overview

Mexico has strengthened its trade and investment links with the U.S. thanks to the privileged status granted by

the North American Free Trade Agreement since 1994. More recently, the country has been benefiting not only

as a result of the U.S. tariff policy implemented against China but also because of the ongoing relocation of

global supply chains, a phenomenon fueled by the pandemic and geopolitical events. Mexico recently displaced

China as the main trade provider to the U.S. market. However, Mexico has not been exempted from trade

frictions, as lately the U.S. does not perceive Mexico’s friendly neighbor status as strong.

In the three-decade life of the trilateral trade agreement that involves Mexico, the U.S. and Canada, the value of

Mexican exports has increased by more than tenfold, and Mexico’s trade balance with the U.S. has improved

significantly, from a deficit of $2.4 billion in 1993 to a stratospheric surplus of $234.7 billion in 2023. U.S. direct

investment pouring into Mexico has multiplied from $3.5 billion in 1993 to $20 billion in 2023; this is not only in

terms of new investments but also reinvestments, an indication of the degree of U.S. corporations’ confidence in

Mexico (see Chart 1).

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 2

Chart 1: México Trade Balance With the U.S.

$ bil, NSA

250

200

150

...Illllll

100

50

-50

93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

Sources: Central Bank of México, Moody’s Analytics

However, with the arrival of U.S. President Donald Trump to office in 2017 and as a result of his policy of

bringing jobs back to the U.S., the trilateral trade agreement faced headwinds, and China’s exports to the U.S.

were penalized with higher tariffs. Fortunately, the trilateral agreement was renegotiated, and the United States-

Mexico-Canada Agreement entered into force in mid-2020. Mexico’s trade with the U.S. did not suffer during the

negotiation period as the country’s surplus with its northern neighbor continued to swell. Since 2021, trade

tariffs on China have been ratified and extended under U.S. President Joe Biden. As a result, China lost its

status as the main trade partner for goods to the U.S. market. The proportion of Chinese imports to the U.S. fell

significantly in the past two years from almost 19% at the start of 2022 to only 13.5% at the end of 2023. 1

Meanwhile, U.S. imports from Mexico gained space and increased to around 16% at the end of 2023 from

13.5% at the start of 2022, making Mexico the main provider of products to the U.S. market and pushing China

to second place at the end of 2022. Canada then pushed China to third place in the last quarter of 2023 (see

Chart 2).

Mexico has become a net beneficiary of the U.S. tariff policy toward China, as indicated by its market gain in the

past few years. It also benefited from the prolonged disruption in supply chains caused by the pan- demic

response, which forced U.S. companies to find closer and more reliable providers. Mexico, being part of the

three-decade-long trilateral trade agreement, fully qualified to benefit from the relocation of some U.S. plants

and investments. Also, given Mexico’s geographical closeness to the largest market in the world, the country

also attracted plants and investments from China and other Asian countries. As a result, foreign direct

investment into Mexico accelerated after the pandemic, and prospects continue to improve as other

corporations express interest in investing in Mexico.

Nearshoring is also introducing some inconveniences to U.S.-Mexico trade relations. Some Asian companies

are interested in moving to or expanding their production plants in Mexico to take advantage of the USMCA

trilateral trade agreement by complying with the agreement’s regional content requirements and conse- quently

accessing the U.S. market under preferential tariffs. Bilateral trade frictions have always existed,

1 Bureau of Economic Analysis. “U.S. International Trade in Goods”

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 3

Chart 2: U.S. Main Import Providers

% of total U.S. imports of goods, SA

20

18

illlllll

16

14

12

10

22Q1 22Q2 22Q3 22Q4 23Q1 23Q2 23Q3 23Q4

China Mexico Canada

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Moody’s Analytics

but they have increased in the past few years mainly as a result of measures taken by Mexico’s government to

limit private competition in key sectors of the economy such as oil and electricity, which adversely affect some

U.S. firms and Canadian investors. These issues could limit the benefits of nearshoring in the longer term.

Meanwhile, nearshoring is a reality for Mexico; however, to take full advantage of this process, Mexico must

improve the business climate and provide the infrastructure required by global players.

Nearshoring: The positives and negatives

Benefits

Nearshoring can be defined as the process of relocating production plants and investments from one country or

region to another one closer to an important market with the purposes of ensuring the supply of inputs and

products and reducing production costs. Nearshoring is usually accompanied by friendshoring, a relo- cation

process that includes the selection of a place that provides a friendly environment for doing business and a

political democracy that respects property rights.

The arrival of investments and plants to Mexico is essentially a nearshoring process triggered by three factors.

First, the proliferation of protectionist policies has sought to shield local producers from unfair trade practices

through the imposition of import tariffs. Second, the disruption in supply chains introduced by the COVID-19

pandemic contributed to an extended paralysis in production and distribution processes given the shutdown of

international borders and transportation. Third, geopolitical events (including the Russia-Ukraine war and China-

Taiwan frictions) added disruptions in the supply and distribution of commodities and manufactur- ing inputs.

Production and consumption markets were forced to seek closer providers to reduce the risk of logistics

disruption.

The benefits of nearshoring are diverse for both the promoter and the receiver of the relocation. It strengthens

the trade partnership and integration of supply chains, increases the flow of investment and trade, stimulates

the transfer of technology and consequently productivity, and promotes economic growth and labor. In the case

of U.S.-Mexico nearshoring, both countries greatly benefit. U.S. corporations relocate to Mexico production

plants that have operated overseas and mainly in China to ensure the supply of inputs from a very close partner

just across the border, improving logistics and reducing costs. On the other side, Mexico receives increasing

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 4

flows of direct investments, new technology, the possibility to create more and better-paid employment, and

increased trade with its main trading partner and the largest market in the world.

In 2023 the flow of foreign direct investment into Mexico increased about 30% from the year before, discounting

the merger and acquisition of two corporations operating in Mexico. Certainly, the U.S. is the largest contributor

of FDI to Mexico. This was particularly the case in 2023, when the U.S. represented around 45% of Mexico’s

total FDI. Looking at the amount of FDI in 2023, one cannot find direct evidence of the contribution provided by

nearshoring in terms of new investments coming from abroad. This is because an important part of the FDI

associated with nearshoring is recorded as reinvestments made by foreign corporations already operating in

Mexico, which implies that those firms are using profits to expand their plants and capacity in the country. Thus,

while reinvestments represented only 40% of total FDI in 2021, they increased their participation to 74% in

2023.

A number of announcements by foreign companies regarding their plans to invest in Mexico confirm the reality

of this nearshoring trend. Mexico’s Ministry of Finance estimates that such announcements accounted for

around $74 billion of FDI through October 2023,2 including investments in energy, railroads, and trans- portation

and communication. An update from announcements made through the first three months of 2024 accounts for

another $31.5 billion.3 The automotive sector is a key player in expressions of interest to expand in Mexico by

companies such as Tesla, BMW, Ford and GM along with Asian manufacturers including BYD and KIA.

The main trade-off for Mexico is that it must commit to creating and improving the infrastructure required by

these global players to ensure that the nearshoring and its benefits materialize. Improved roads, ports, airports,

and expanded basic infrastructure for water and electricity (particularly from renewable energy) are needed as

well as improved and expedited business processes.

Inconveniences

While Mexico reaps many benefits from nearshoring, the U.S. also sees gains mainly in terms of ensured

supplies of inputs and products from its next-door neighbor at cheaper costs of production and transporta- tion.

However, nearshoring is also attracting the relocation of non-U.S. plants and investments to Mexico, particularly

from countries facing nonpreferential treatment by the U.S. China and some other Asian countries that face

tariff restrictions from the U.S. view relocation to Mexico as a way to access the U.S. market under the

preferential treatment granted by the USMCA. This could be possible if a Chinese manufacturer relocates or

opens a production plant in Mexican territory and complies with the established regional content requirements,

known as the rule of origin or ROO, in the trilateral agreement.

Asian automakers already exist in Mexico. However, the U.S. trade policy on tariffs for Chinese products seems

to be a factor accelerating the relocation of Chinese manufacturers to Mexico. An example of this is China’s

BYD, which began selling electric cars in Mexico in 2023 and announced intentions to build a manu- facturing

plant there, even though BYD has said it will focus only on the domestic market. 4 Mexican media also has

reported about Tesla’s intentions to open a plant in the northern state of Nuevo Leon, with an estimated

investment of $10 billion, and KIA’s expansion, which will account for $6 billion. Whether these plants

materialize or not, they are already being taken into account by Mexican authorities, particularly the Ministry of

Economics.

Meanwhile, on the U.S. side, there is increased demand to enforce the trade policy to protect domestic

2 Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público “Comunicado No.68”

3 Secretaría de Economía “Comunicado de Prensa”, 15 de Marzo, 2024.

4 Yahoo Finance, “BYD not planning to come to the U.S.”, February 27, 2024.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 5

producers and to investigate potential unfair trade practices in the auto and steel industries involving Mexico.

Regarding China’s threat to America’s auto industry via Mexico,5 the most recent example is the Alliance for

American Manufacturing raising the alarm over China’s plant expansions in Mexico and their access to the U.S.

market by taking advantage of more favorable tariffs under the USMCA. A second example is the U.S. claim

about a potential triangulation of steel and aluminum products via Mexico.6

Suspicions are increasing about Mexico being used as a back door to redirect Chinese imports into the U.S. A

recent press release from Xeneta, a platform specializing in ocean freight rate benchmarking and market

intelligence, reported a “massive increase in container shipping imports from China into Mexico,”7 raising

suspicion that some of those Chinese imports could end up in the U.S. as importers try to avoid U.S. tariffs.

Searching for signs of triangulation

Mexico’s imports from China have maintained a relatively stable proportion of around 19% of the total in the

past four years, though they doubled from $5.5 billion in 2016 to $10 billion in 2023. The expansion began in

2021, when imports from China grew 37%. Growth moderated to 17% in 2022 and contracted 4% in 2023. In

terms of current-dollar value, the data do not show evidence of a steady Chinese import pen- etration in Mexico.

There is a counterargument, however, that the data reflect the influence of prices. For example, if import prices

declined significantly, then the volume of Chinese imports could have increased. The number of containers

arriving in Mexico from China is an additional piece of information that supports the argument of a massive

arrival of Chinese imports into Mexico. According to Xeneta’s report, the number of containers expanded at an

annual rate of 60% in January 2024, growing from 73,000 units to 117,000 units. Certainly, there has been a

significant expansion in the past two years, with the number of containers increasing 3.5% in 2022 and 35% in

2023. Therefore, the analysis must focus on volume of trade, which is defined as trade in constant prices, rather

than on current-dollar value.

As a first attempt to search for more solid evidence, we perform a two-step data analysis about the volume of

imports from China to Mexico and the volume of Mexico’s exports of manufacturing products to the U.S. This

analysis will help us to gain some insights about the possibility of a triangulation of Chinese imports into the

U.S. that are wrapped as Mexican exports. The first step will allow us to determine if there are signs of a

Chinese import penetration to Mexico in the past few years, and the second will help us to see the degree of

correlation between the volume of Mexico’s manufacturing exports to the U.S. and the country’s manufacturing

capacity and employment. If the volume of Mexico’s manufacturing exports has expanded in an environment of

unchanged capacity utilization and employment, that would be an indication that the extra volume exported

comes from somewhere else. One source may be an improvement in productivity, in this case defined as the

increase in output using the same number of inputs. If that is the case, then data should not show a decrease in

employment. In other words, if employment has decreased and the use of capacity remains the same, then

someone is producing the extra volume exported to the U.S. The same applies to the case of capacity

utilization.

Has the volume of Chinese imports to Mexico expanded?

After plunging in the first half of 2020 because of the disruptions after the COVID-19 outbreak, the volume of

total imports from China recovered to the pre-pandemic level by the third quarter of 2021 and remained

relatively stable in 2022. Since then, import volume from China has expanded. It grew 22% in the second

quarter of 2023 and averaged around 20% annual growth for the last three quarters of the year. For all of 2023,

volume surged 14% over the 2022 level (see Chart 3), while the value of imports contracted 4%. A trend of

5 American Manufacturing Org. On a Collision Course.

6 USTR, Press Release, September 29, 2023.

7 Xeneta, Press Release, March 15, 2024.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 6

increased Chinese imports appears to be extending into 2024 as indicated by the signif- icant increase in the

number of containers reported by Xeneta, and because the value of imports from China expanded 12%

annually in January amid a 1% decrease in the total value of Mexico’s imports. It is important to remark that

most of Mexico’s imports from China are nonoil products, with manufacturing imports being an important

contributor.

Chart 3: Mexico’s Volume of Imports From China

2018$ bil, SA

30

25

20

15

10

19Q4 20Q1 20Q2 20Q3 20Q4 21Q1 21Q2 21Q3 21Q4 22Q1 22Q2 22Q3 22Q4 23Q1 23Q2 23Q3 23Q4

Sources: Central Bank of México, Moody’s Analytics

So far, the data show evidence that the volume of imports from China expanded in 2023, even though the value

decreased as mentioned before. One explanation lies in the decrease of import prices resulting from the

strength of the Mexican peso during the year. In this case, Mexico bought cheaper products from China thanks

to the strong peso. Another potential explanation could be that China sold its products at discounted prices to

Mexico. In this case, China wanted to gain a market in Mexico. The main conclusion here is that the volume of

imports from China has certainly expanded and increased its participation in Mexico’s total imports by 1.5

percentage points from 2017 when U.S. President Trump took office. This could be explained as a delib- erate

Chinese policy to diversify its trade markets given the U.S. restrictions imposed on imports from China (see

Chart 4).

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 7

Chart 4: Mexico’s Volume of Imports From China

% of total imports, SA

Sources: Central Bank of México, Moody’s Analytics

Has the volume of Mexico’s manufacturing exports to the U.S. expanded?

The U.S. is the main market for Mexican exports with the neighboring country a destination for more than 80%

of Mexico’s total sales abroad. Manufacturing exports represent almost 90% of Mexico’s total exports, and

manufacturing exports to the U.S. market represent 75% of total exports. This makes manufacturing exports the

main channel for Mexico to increase its export penetration in the U.S. Thus, our focus is to see if data indicate a

gain in market participation for Mexico’s manufacturing exports to the U.S. In the past two years, Mexico’s

manufacturing exports gained 1.1 percentage points as a proportion of total exports, and manufacturing exports

to the U.S. gained 1.7 percentage points in the total. This is an indication that Mexico has exported more

volume of manufacturing products to the U.S. in the past two years (see Chart 5).

Chart 5: Mexico’s Volume of Exports of Goods

% of total exports of goods, SA

Sources: Central Bank of México, Moody’s Analytics

If that extra volume of manufacturing exports is explained by more employment and increased capacity

utilization, then there is no doubt that Mexico has increased its domestic capacity to produce more exports. By

including employment in manufacturing production in the analysis, we see that jobs increased 2.4% from the

end of 2022 to the end of 2023. Thus, the industry has certainly occupied more workers in the past year, which

in principle could explain the increase in production and consequently in the volume of products exported.

Moreover, capacity utilization by manufacturers decreased 3% in the same period. This raises two questions:

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 8

Why are more workers now using less capacity? And, in the absence of an increase in productivity, would not

more workers use more capacity instead of less (see Chart 6)?

Chart 6: Exports, Employment and Capacity Utilization

Y-axes: 2018=100 (L), % of total capacity (R)

Manufacturing exports Manufacturing exports to U.S. Manufacturing employment ^—Capacity utilization

Sources: INEGI, Central Bank of Mexico, Moody’s Analytics

The insights gained only leave the door open to the possibility that the increase in the volume of manufacturing

production, without utilizing more capacity, could be partly explained by products generated outside of Mexico.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 9

About the Author

Alfredo Coutino is a director at Moody’s Analytics. Dr. Coutino is responsible for analysis, modeling and forecasting for Latin America.

Based in the King of Prussia PA office, he is in charge of real-time coverage of Latin America for Economic View. He is a regular

presenter at our annual Macroeconomic Outlook Conference. He has been a speaker at United Nations conferences and at the

American Economic Association and has published papers on applied econometrics with Nobel laureate Lawrence Klein. Dr. Coutino

received his PhD in economics from the University of Madrid after completing doctoral studies at Temple University.

MOODY’S ANALYTICS NEARSHORING AND POTENTIAL TRADE TRIANGULATION 10

About Moody’s Analytics

Moody’s Analytics provides financial intelligence and analytical tools supporting our clients’ growth, efficiency and risk

management objectives. The combination of our unparalleled expertise in risk, expansive information resources, and

innovative application of technology helps today’s business leaders confidently navigate an evolving marketplace. We are

recognized for our industry-leading solutions, comprising research, data, software and professional services, assembled to

deliver a seamless customer experience. Thousands of organizations worldwide have made us their trusted partner

because of our uncompromising commitment to quality, client service, and integrity.

Concise and timely economic research by Moody’s Analytics supports firms and policymakers in strategic planning, product and

sales forecasting, credit risk and sensitivity management, and investment research. Our economic research publications provide

in-depth analysis of the global economy, including the U.S. and all of its state and metropolitan areas, all European countries and

their subnational areas, Asia, and the Americas. We track and forecast economic growth and cover specialized topics such as

labor markets, housing, consumer spending and credit, output and income, mortgage activity, demographics, central bank

behavior, and prices. We also provide real-time monitoring of macroeconomic indicators and analysis on timely topics such as

monetary policy and sovereign risk. Our clients include multinational corporations, governments at all levels, central banks,

financial regulators, retailers, mutual funds, financial institutions, utilities, residential and commercial real estate firms, insurance

companies, and professional investors.

Moody’s Analytics added the economic forecasting firm Economy.com to its portfolio in 2005. This unit is based in King of

Prussia PA, a suburb of Philadelphia, with offices in London, Prague and Sydney. More information is available at

www.economy.com.

Moody’s Analytics is a subsidiary of Moody’s Corporation (NYSE: MCO). Further information is available at

www.moodysanalytics.com.

DISCLAIMER: Moody’s Analytics, a unit of Moody’s Corporation, provides economic analysis, credit risk data and insight, as well

as risk management solutions. Research authored by Moody’s Analytics does not reflect the opinions of Moody’s Investors

Service, the credit rating agency. To avoid confusion, please use the full company name “Moody’s Analytics”, when citing views

from Moody’s Analytics.

About Moody’s Corporation

Moody’s Analytics is a subsidiary of Moody’s Corporation (NYSE: MCO). MCO reported revenue of $5.9 billion in 2023, employs

approximately 15,000 people worldwide and maintains a presence in more than 40 countries. Further information about Moody’s

Analytics is available at www.moodysanalytics.com.

© 2024 Moody’s Corporation, Moody’s Investors Service, Inc., Moody’s Analytics, Inc. and/or their licensors and affiliates (collectively, “MOODY’S”). All rights reserved.

CREDIT RATINGS ISSUED BY MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS AFFILIATES ARE THEIR CURRENT OPINIONS OF THE RELATIVE FUTURE CREDIT RISK OF

ENTITIES, CREDIT COMMITMENTS, OR DEBT OR DEBT-LIKE SECURITIES, AND MATERIALS, PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND INFORMATION PUBLISHED OR

OTHERWISE MADE AVAILABLE BY MOODY’S (COLLECTIVELY, “MATERIALS”) MAY INCLUDE SUCH CURRENT OPINIONS. MOODY’S DEFINES CREDIT RISK

AS THE RISK THAT AN ENTITY MAY NOT MEET ITS CONTRACTUAL FINANCIAL OBLIGATIONS AS THEY COME DUE AND ANY ESTIMATED FINANCIAL LOSS

IN THE EVENT OF DEFAULT OR IMPAIRMENT. SEE APPLICABLE MOODY’S RATING SYMBOLS AND DEFINITIONS PUBLICATION FOR INFORMATION ON THE

TYPES OF CONTRACTUAL FINANCIAL OBLIGATIONS ADDRESSED BY MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS. CREDIT RATINGS DO NOT ADDRESS ANY OTHER RISK,

INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO: LIQUIDITY RISK, MARKET VALUE RISK, OR PRICE VOLATILITY. CREDIT RATINGS, NON-CREDIT ASSESSMENTS

(“ASSESSMENTS”), AND OTHER OPINIONS INCLUDED IN MOODY’S MATERIALS ARE NOT STATEMENTS OF CURRENT OR HISTORICAL FACT. MOODY’S

MATERIALS MAY ALSO INCLUDE QUANTITATIVE MODEL-BASED ESTIMATES OF CREDIT RISK AND RELATED OPINIONS OR COMMENTARY PUBLISHED BY

MOODY’S ANALYTICS, INC. AND/OR ITS AFFILIATES. MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS, OTHER OPINIONS AND MATERIALS DO NOT CONSTITUTE

OR PROVIDE INVESTMENT OR FINANCIAL ADVICE, AND MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS, OTHER OPINIONS AND MATERIALS ARE NOT AND DO

NOT PROVIDE RECOMMENDATIONS TO PURCHASE, SELL, OR HOLD PARTICULAR SECURITIES. MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS, OTHER

OPINIONS AND MATERIALS DO NOT COMMENT ON THE SUITABILITY OF AN INVESTMENT FOR ANY PARTICULAR INVESTOR. MOODY’S ISSUES ITS CREDIT

RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS AND OTHER OPINIONS AND PUBLISHES OR OTHERWISE MAKES AVAILABLE ITS MATERIALS WITH THE EXPECTATION AND

UNDERSTANDING THAT EACH INVESTOR WILL, WITH DUE CARE, MAKE ITS OWN STUDY AND EVALUATION OF EACH SECURITY THAT IS UNDER

CONSIDERATION FOR PURCHASE, HOLDING, OR SALE.

MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS, OTHER OPINIONS, AND MATERIALS ARE NOT INTENDED FOR USE BY RETAIL INVESTORS AND IT WOULD BE

RECKLESS AND INAPPROPRIATE FOR RETAIL INVESTORS TO USE MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS, OTHER OPINIONS OR MATERIALS WHEN MAKING AN

INVESTMENT DECISION. IF IN DOUBT YOU SHOULD CONTACT YOUR FINANCIAL OR OTHER PROFESSIONAL ADVISER.

ALL INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN IS PROTECTED BY LAW, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO, COPYRIGHT LAW, AND NONE OF SUCH INFORMATION MAY BE

COPIED OR OTHERWISE REPRODUCED, REPACKAGED, FURTHER TRANSMITTED, TRANSFERRED, DISSEMINATED, REDISTRIBUTED OR RESOLD, OR STORED FOR

SUBSEQUENT USE FOR ANY SUCH PURPOSE, IN WHOLE OR IN PART, IN ANY FORM OR MANNER OR BY ANY MEANS WHATSOEVER, BY ANY PERSON WITHOUT

MOODY’S PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT. FOR CLARITY, NO INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN MAY BE USED TO DEVELOP, IMPROVE, TRAIN OR RETRAIN ANY

SOFTWARE PROGRAM OR DATABASE, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, FOR ANY ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, MACHINE LEARNING OR NATURAL LANGUAGE

PROCESSING SOFTWARE, ALGORITHM, METHODOLOGY AND/OR MODEL.

MOODY’S CREDIT RATINGS, ASSESSMENTS, OTHER OPINIONS AND MATERIALS ARE NOT INTENDED FOR USE BY ANY PERSON AS A BENCHMARK AS THAT TERM

IS DEFINED FOR REGULATORY PURPOSES AND MUST NOT BE USED IN ANY WAY THAT COULD RESULT IN THEM BEING CONSIDERED A BENCHMARK.

All information contained herein is obtained by MOODY’S from sources believed by it to be accurate and reliable. Because of the possibility of human or mechanical error as well as other

factors, however, all information contained herein is provided “AS IS” without warranty of any kind. MOODY’S adopts all necessary measures so that the information it uses in assigning a

credit rating is of sufficient quality and from sources MOODY’S considers to be reliable including, when appropriate, independent third-party sources. However, MOODY’S is not an auditor

and cannot in every instance independently verify or validate information received in the credit rating process or in preparing its Materials.

To the extent permitted by law, MOODY’S and its directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives, licensors and suppliers disclaim liability to any person or entity for any indirect,

special, consequential, or incidental losses or damages whatsoever arising from or in connection with the information contained herein or the use of or inability to use any such information, even

if MOODY’S or any of its directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives, licensors or suppliers is advised in advance of the possibility of such losses or damages, including but not

limited to: (a) any loss of present or prospective profits or (b) any loss or damage arising where the relevant financial instrument is not the subject of a particular credit rating assigned by

MOODY’S.

To the extent permitted by law, MOODY’S and its directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives, licensors and suppliers disclaim liability for any direct or compensatory losses or

damages caused to any person or entity, including but not limited to by any negligence (but excluding fraud, willful misconduct or any other type of liability that, for the avoidance of doubt, by

law cannot be excluded) on the part of, or any contingency within or beyond the control of, MOODY’S or any of its directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives, licensors or suppliers,

arising from or in connection with the information contained herein or the use of or inability to use any such information.

NO WARRANTY, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, AS TO THE ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PARTICULAR PURPOSE OF

ANY CREDIT RATING, ASSESSMENT, OTHER OPINION OR INFORMATION IS GIVEN OR MADE BY MOODY’S IN ANY FORM OR MANNER WHATSOEVER.

Moody’s Investors Service, Inc., a wholly-owned credit rating agency subsidiary of Moody’s Corporation (“MCO”), hereby discloses that most issuers of debt securities (including corporate

and municipal bonds, debentures, notes and commercial paper) and preferred stock rated by Moody’s Investors Service, Inc. have, prior to assignment of any credit rating, agreed to pay to

Moody’s Investors Service, Inc. for credit ratings opinions and services rendered by it fees ranging from $500 to approximately $5,300,000. MCO and Moody’s Investors Service also maintain

policies and procedures to address the independence of Moody’s Investors Service credit ratings and credit rating processes. Information regarding certain affiliations that may exist between

directors of MCO and rated entities, and between entities who hold credit ratings from Moody’s Investors Service, Inc. and have also publicly reported to the SEC an ownership interest in MCO

of more than 5%, is posted annually at www.moodys.com under the heading “Investor Relations — Corporate Governance — Charter Documents - Director and Shareholder Affiliation Policy.”

Moody’s SF Japan K.K., Moody’s Local AR Agente de Calificación de Riesgo S.A., Moody’s Local BR Agencia de Classificaeao de Risco LTDA, Moody’s Local MX S.A. de C.V, I.C.V.,

Moody’s Local PE Clasificadora de Riesgo S.A., and Moody’s Local PA Calificadora de Riesgo S.A. (collectively, the “Moody’s Non-NRSRO CRAs”) are all indirectly wholly-owned credit

rating agency subsidiaries of MCO. None of the Moody’s Non-NRSRO CRAs is a Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization. Additional terms for Australia only: Any publication

into Australia of this document is pursuant to the Australian Financial Services License of MOODY’S affiliate, Moody’s Investors Service Pty Limited ABN 61 003 399 657AFSL 336969

and/or Moody’s Analytics Australia Pty Ltd ABN 94 105 136 972 AFSL 383569 (as applicable). This document is intended to be provided only to “wholesale clients” within the meaning of

section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001. By continuing to access this document from within Australia, you represent to MOODY’S that you are, or are accessing the document as a

representative of, a “wholesale client” and that neither you nor the entity you represent will directly or indirectly disseminate this document or its contents to “retail clients” within the meaning

of section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001. MOODY’S credit rating is an opinion as to the creditworthiness of a debt obligation of the issuer, not on the equity securities of the issuer or any

form of security that is available to retail investors.

Additional terms for India only: Moody’s credit ratings, Assessments, other opinions and Materials are not intended to be and shall not be relied upon or used by any users located in India in

relation to securities listed or proposed to be listed on Indian stock exchanges.

Additional terms with respect to Second Party Opinions (as defined in Moody’s Investors Service Rating Symbols and Definitions): Please note that a Second Party Opinion (“SPO”) is not a

“credit rating”. The issuance of SPOs is not a regulated activity in many jurisdictions, including Singapore. JAPAN: In Japan, development and provision of SPOs fall under the category of

“Ancillary Businesses”, not “Credit Rating Business”, and are not subject to the regulations applicable to “Credit Rating Business” under the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act of Japan

and its relevant regulation. PRC: Any SPO: (1) does not constitute a PRC Green Bond Assessment as defined under any relevant PRC laws or regulations; (2) cannot be included in any

registration statement, offering circular, prospectus or any other documents submitted to the PRC regulatory authorities or otherwise used to satisfy any PRC regulatory disclosure requirement;

and (3) cannot be used within the PRC for any regulatory purpose or for any other purpose which is not permitted under relevant PRC laws or regulations. For the purposes of this disclaimer,

“PRC” refers to the mainland of the People’s Republic of China, excluding Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

You might also like

- Luc Duy Khanh - EBBA 13.1 - ASSIGNMENT 2Document4 pagesLuc Duy Khanh - EBBA 13.1 - ASSIGNMENT 2Khánh Lục100% (1)

- Practice Problems Capital Structure 25-09-2021Document17 pagesPractice Problems Capital Structure 25-09-2021BHAVYA KANDPAL 13BCE02060% (1)

- Resettlement Area For Informal Settlers Families of Barangay Bucana in Davao CityDocument12 pagesResettlement Area For Informal Settlers Families of Barangay Bucana in Davao CityJERILON LUNTAD100% (1)

- Nearshoring and Potential TradeDocument12 pagesNearshoring and Potential TradeLuis Maxx MarinNo ratings yet

- U.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues, and ImplicationsDocument32 pagesU.S.-Mexico Economic Relations: Trends, Issues, and ImplicationsMar MuñozNo ratings yet

- North America Supply ChainsDocument11 pagesNorth America Supply ChainshemangppatelNo ratings yet

- Effects of The Recent USMCA Trade Agreement - EditedDocument10 pagesEffects of The Recent USMCA Trade Agreement - EditedCollins OmondiNo ratings yet

- UpdatebooktwDocument9 pagesUpdatebooktwpratsondasNo ratings yet

- IB NgaDocument13 pagesIB Ngafuchsia30052004No ratings yet

- CX Frontline NorthwesternDocument68 pagesCX Frontline Northwesternryan_earl25No ratings yet

- Regional Focus: NAFTA Balance Shifts Towards Mexican ManufacturingDocument4 pagesRegional Focus: NAFTA Balance Shifts Towards Mexican ManufacturingAdhi Chandra WirawanNo ratings yet

- TnijeDocument9 pagesTnijeyusmira miraNo ratings yet

- NAFTA at 20 - Accomplishments, Challenges, and The Way ForwardDocument5 pagesNAFTA at 20 - Accomplishments, Challenges, and The Way ForwardmymarketingplanNo ratings yet

- Ficha Nearshoring - 20230717 - ENGDocument5 pagesFicha Nearshoring - 20230717 - ENGana.fackoNo ratings yet

- The North American Economies After NAFTA: A Critical AppraisalDocument23 pagesThe North American Economies After NAFTA: A Critical AppraisalSam Sep A SixtyoneNo ratings yet

- Perspectives of The Pacific AllianceDocument10 pagesPerspectives of The Pacific AllianceGuadalupeNo ratings yet

- NAFTADocument6 pagesNAFTAfbastidas98No ratings yet

- Mexico Nearshoring Report SwissCham 2022 - CompressedDocument20 pagesMexico Nearshoring Report SwissCham 2022 - Compressedsqueeze100% (1)

- International Negotiation Essay: Commercial Conflict Between China and The United StatesDocument5 pagesInternational Negotiation Essay: Commercial Conflict Between China and The United StatesManuelaNo ratings yet

- US China Trade WarDocument25 pagesUS China Trade WarDevashish ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 5Document25 pagesJurnal 5TrilastNo ratings yet

- International Business: Assignment On North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta)Document7 pagesInternational Business: Assignment On North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta)Kaustubh SuryawanshiNo ratings yet

- GLSD3501 FinalPaperDocument8 pagesGLSD3501 FinalPaperahh19960615No ratings yet

- JakariaShahB00901695 Coursework1partbDocument4 pagesJakariaShahB00901695 Coursework1partbShah Md. Jakaria AbirNo ratings yet

- International BusinessDocument12 pagesInternational BusinessThe CarterNo ratings yet

- AtualidadesDocument18 pagesAtualidadesDaniela Ramos EduardoNo ratings yet

- Region Views: Latin America: A Changing of The GuardDocument13 pagesRegion Views: Latin America: A Changing of The Guardapi-128097200No ratings yet

- Course CorrectionDocument20 pagesCourse CorrectionCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- IB Assignment 2Document7 pagesIB Assignment 2Hammad khanNo ratings yet

- AmericaDocument8 pagesAmericateshome mekonnenNo ratings yet

- WBWP US Trade PolicyDocument30 pagesWBWP US Trade PolicyAndrew MayedaNo ratings yet

- Mscscm626 - Weekend Class-Group 6 Nafta Case StudyDocument11 pagesMscscm626 - Weekend Class-Group 6 Nafta Case StudyJustice Pilot TaperaNo ratings yet

- House Republican Conference Issue Brief - NAFTA - Summary and AnalysisDocument14 pagesHouse Republican Conference Issue Brief - NAFTA - Summary and AnalysischovsonousNo ratings yet

- DAHAB MASR 2022 Annual ReportDocument11 pagesDAHAB MASR 2022 Annual ReportDahab Masr- YouTubeNo ratings yet

- Tự luận TMQTDocument13 pagesTự luận TMQTsingletaskerplusNo ratings yet

- China-US Trade War UnveiledDocument5 pagesChina-US Trade War Unveiledyunlong zhaoNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Paper Ni RogerDocument2 pagesDescriptive Paper Ni RogerAndrei PagurayNo ratings yet

- Global Market Structures and The High Price of ProtectionismDocument9 pagesGlobal Market Structures and The High Price of ProtectionismHeisenbergNo ratings yet

- New Ideas For A New Era: Policy Options For The Next Stage in US-Mexico RelationsDocument77 pagesNew Ideas For A New Era: Policy Options For The Next Stage in US-Mexico RelationsThe Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- NAFTA and The Mexican Economy: A Guide To The Winners, Losers, and Administrators of Free TradeDocument16 pagesNAFTA and The Mexican Economy: A Guide To The Winners, Losers, and Administrators of Free TradeJayKarimiNo ratings yet

- Dragonomics How Latin America Is Maximizing or Missing Out On China S International Development StrategyDocument328 pagesDragonomics How Latin America Is Maximizing or Missing Out On China S International Development StrategyJuan Felipe Estrada TrianaNo ratings yet

- Lec. 2.1 World Economic and Trading SituationDocument13 pagesLec. 2.1 World Economic and Trading Situationpavithran selvamNo ratings yet

- Building Resilient Global Supply ChainDocument7 pagesBuilding Resilient Global Supply ChainrexNo ratings yet

- US-Mexico Economic RelationsDocument41 pagesUS-Mexico Economic RelationsDeepan Kumar DasNo ratings yet

- North American Region: Efimenco Olesea Gisca Alina FB147Document19 pagesNorth American Region: Efimenco Olesea Gisca Alina FB147Alina GiscaNo ratings yet

- Assignment On: US-China Trade War and It's Impact On World EconomyDocument5 pagesAssignment On: US-China Trade War and It's Impact On World EconomyM.h. SamratNo ratings yet

- The Mexican Economy After The Global Financial Crisis: M. Angeles VillarrealDocument24 pagesThe Mexican Economy After The Global Financial Crisis: M. Angeles VillarrealGabriel Andreas LFNo ratings yet

- Russel Hillberry - Trade and Trade Policy Outlook, 2022 Purdue Agricultural Economics Report PDFDocument5 pagesRussel Hillberry - Trade and Trade Policy Outlook, 2022 Purdue Agricultural Economics Report PDFWilliam WulffNo ratings yet

- Rakhi - Rome 2900566 674415075Document9 pagesRakhi - Rome 2900566 674415075Rakhi ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Vilsack Tai-Letter USDA-Mexico-Issues Final 210322Document5 pagesVilsack Tai-Letter USDA-Mexico-Issues Final 210322La Silla RotaNo ratings yet

- EMEA Group11 MexicoDocument21 pagesEMEA Group11 MexicoRAJARSHI ROY CHOUDHURYNo ratings yet

- Stefano Emran Econ Report ProgressDocument6 pagesStefano Emran Econ Report ProgressAdewaNo ratings yet

- What Path Do Luxury Brands Follow On The Eve of The Economic Crisis?Document10 pagesWhat Path Do Luxury Brands Follow On The Eve of The Economic Crisis?Elisa CuomoNo ratings yet

- Apparel Imports USDocument9 pagesApparel Imports USTarek OsmanNo ratings yet

- Open Economy Brings Rewards: MexicoDocument4 pagesOpen Economy Brings Rewards: Mexico0arambur0No ratings yet

- Trade Theory: Would You Characterize Your Country As Afree-Trader or Protectionist Country & Why?Document8 pagesTrade Theory: Would You Characterize Your Country As Afree-Trader or Protectionist Country & Why?Kanaya AgarwalNo ratings yet

- M02Efa - Critical Issues in Global Business.: Module Leader: DR. S.Thandi Name: Sonu SinghDocument12 pagesM02Efa - Critical Issues in Global Business.: Module Leader: DR. S.Thandi Name: Sonu SinghSonu SinghNo ratings yet

- Essay Inter-Trade 2023Document22 pagesEssay Inter-Trade 2023Trúc ThanhNo ratings yet

- Preliminary OutlineDocument3 pagesPreliminary OutlineTommy ZhangNo ratings yet

- Task #07&8 Submitted To:: International Relations and Current Affairs MGT-226Document4 pagesTask #07&8 Submitted To:: International Relations and Current Affairs MGT-226vbn7rdkkntNo ratings yet

- Rules of Origin and Regional ContentDocument4 pagesRules of Origin and Regional ContentIftekharul Mahdi100% (1)

- PGIM Reuters A New Era Deglobalization To Regionalization 032023Document25 pagesPGIM Reuters A New Era Deglobalization To Regionalization 032023qixin chenNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "The Difficult International Insertion Of Latin America" By Enrique Iglesias: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "The Difficult International Insertion Of Latin America" By Enrique Iglesias: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- 2024 - Price List - Orchid PlantsDocument92 pages2024 - Price List - Orchid PlantsRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- AWZ - Special Plants List - MAY-2024 - (Photos) - (v1) - RK-019Document19 pagesAWZ - Special Plants List - MAY-2024 - (Photos) - (v1) - RK-019Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Avance Rep DiarioDocument4 pagesAvance Rep DiarioRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Microdistillers H - September 2022Document91 pagesMicrodistillers H - September 2022Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- A Microscope On Small Businesses Spotting Opportunities To Boost Productivity v4Document56 pagesA Microscope On Small Businesses Spotting Opportunities To Boost Productivity v4Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Rossioglosum (Baker)Document8 pagesRossioglosum (Baker)Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Cattleya Culture Basics AOSDocument22 pagesCattleya Culture Basics AOSRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- The Estimative Index of DosingDocument16 pagesThe Estimative Index of DosingRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Rhynchostele (Baker)Document25 pagesRhynchostele (Baker)Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- 2018 1352 Moesm1 EsmDocument3 pages2018 1352 Moesm1 EsmRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- The Estimative IndexDocument16 pagesThe Estimative IndexRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Tom BarrDocument6 pagesTom BarrRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Páginas Desdeorchids202110Document6 pagesPáginas Desdeorchids202110Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- How To Restart National Economies During The Coronavirus CrisisDocument16 pagesHow To Restart National Economies During The Coronavirus CrisisRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Páginas Desde (Medicinal and Aromatic Plants - Industrial Profiles) Brian M. Lawrence - Mint - The Genus Mentha-CRC Press (2006)Document6 pagesPáginas Desde (Medicinal and Aromatic Plants - Industrial Profiles) Brian M. Lawrence - Mint - The Genus Mentha-CRC Press (2006)Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Try New Things - Sue Bottom - 01Document1 pageTry New Things - Sue Bottom - 01Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- OCDE TaxDocument3 pagesOCDE TaxRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Intensive Mass Production of Artemia in A Recirculated SystemDocument7 pagesIntensive Mass Production of Artemia in A Recirculated SystemRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Technical and Economical Feasibility of A Rotifer Recirculation SystemDocument17 pagesTechnical and Economical Feasibility of A Rotifer Recirculation SystemRodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Mexico Shale Preliminary Report 2015Document114 pagesMexico Shale Preliminary Report 2015Rodolfo RivadeneyraNo ratings yet

- Adira Asuransi Invoice & Rekap Jamaah - KAW - 21 Feb - 13D - 48paxDocument3 pagesAdira Asuransi Invoice & Rekap Jamaah - KAW - 21 Feb - 13D - 48paxALINSANI TRAVELNo ratings yet

- Government of Andhra Pradesh Boilers Department: Application ID: BEC1900108Document2 pagesGovernment of Andhra Pradesh Boilers Department: Application ID: BEC1900108Bharath NadimpalliNo ratings yet

- AccountingDocument7 pagesAccountingNatasha HerlianaNo ratings yet

- ECO20A Tutorial 3 (1) - Read-OnlyDocument21 pagesECO20A Tutorial 3 (1) - Read-OnlymhlabawethuprojectsNo ratings yet

- Itr Simpal Kumari 23 24Document1 pageItr Simpal Kumari 23 24prateek gangwaniNo ratings yet

- HDFC - Rohtash Kumar (7 Lakh)Document4 pagesHDFC - Rohtash Kumar (7 Lakh)Sonu F1No ratings yet

- Env. & Org. ContextDocument20 pagesEnv. & Org. ContextkirkoNo ratings yet

- CUOnline Student PortalDocument1 pageCUOnline Student PortalSalman CheemaNo ratings yet

- Bill Statement: (Invoice)Document1 pageBill Statement: (Invoice)Terrence LimNo ratings yet

- 12 17 2022 Ab01312900007cphDocument1 page12 17 2022 Ab01312900007cphGolden SausagesNo ratings yet

- RN New JerseyDocument3 pagesRN New JerseywilberespinosarnNo ratings yet

- Booklet - Insider's FrenchDocument264 pagesBooklet - Insider's Frenchadamagar88No ratings yet

- General Agriculture Complete NotesDocument25 pagesGeneral Agriculture Complete Notesswadesh mouryaNo ratings yet

- Mida InfoDocument12 pagesMida InfoMuhammad AdnanNo ratings yet

- Case Project: Awash To Mieso (72 KM) Toll Road ProjectDocument4 pagesCase Project: Awash To Mieso (72 KM) Toll Road ProjectDemewez AsfawNo ratings yet

- The Impact of GlobalizationDocument5 pagesThe Impact of GlobalizationJoy tanNo ratings yet

- Apple Stock Analysis - EditedDocument5 pagesApple Stock Analysis - EditedMeshack MateNo ratings yet

- Semi GolbalizationDocument10 pagesSemi GolbalizationAngel DuguilanNo ratings yet

- Postwar Problems and The RepublicDocument1 pagePostwar Problems and The RepublicRachel NicoleNo ratings yet

- NISM-Series-XXII: Fixed Income Securities Certification ExaminationDocument5 pagesNISM-Series-XXII: Fixed Income Securities Certification ExaminationVinay ChhedaNo ratings yet

- Af A3 State Aid Self AssesmentDocument4 pagesAf A3 State Aid Self AssesmentadinasovailaNo ratings yet

- Igor Birman (Auth.) - Personal Consumption in The USSR and The USA-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1989)Document271 pagesIgor Birman (Auth.) - Personal Consumption in The USSR and The USA-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1989)DANIEL XDNo ratings yet

- MicroEconomics Final ExamDocument6 pagesMicroEconomics Final ExamKanza IqbalNo ratings yet

- CA - SMP at IIMC - Masters in Commerce - FICO - Six Sigma: Ketan Pendse +91 7276650200Document2 pagesCA - SMP at IIMC - Masters in Commerce - FICO - Six Sigma: Ketan Pendse +91 7276650200ss kkNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document14 pagesLesson 2Jhamella PilartaNo ratings yet

- Payments BankDocument3 pagesPayments BankSwagata GhoshNo ratings yet

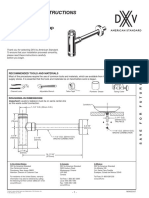

- Installation Instructions: Decorative Bottle TrapDocument2 pagesInstallation Instructions: Decorative Bottle TrapAfzal FasehudeenNo ratings yet