Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management - Trent2004

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management - Trent2004

Uploaded by

pedro.carvalhomartinsguedeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management - Trent2004

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management - Trent2004

Uploaded by

pedro.carvalhomartinsguedeCopyright:

Available Formats

The Use of Organizational Design

Features in Purchasing and Supply

Management

AUTHOR

Of the myriad ways organizations pursue competitive

Robert J. Trent

advantage in their supply management efforts, the most

is the Eugene Mercy associate professor of management and the common are outsourcing, supplier development or

supply chain management program director at Lehigh University strategic alliances and partnerships. Rarely mentioned,

however, is the more mundane topic of organizational

in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

design. Except for cross-functional teaming, organiza-

tional design has received limited attention from supply

This article presents findings from a study exam-

management researchers.

ining organizational design features used by organi-

Organizational design is a broad concept referring to

zations in pursuing their procurement and supply

the process of assessing and selecting the structure and

objectives. The research purpose was to gain a better

formal system of communication, division of labor, coor-

understanding of the organizational dination, control, authority and responsibility required

SUMMARY design features that firms currently to achieve an organization’s goals (Hamel and Pralahad

use or may use in the future. The 1994). One way to think about an organization’s design

results should encourage organizations to address is as a complex web reflecting the pattern of interactions

design issues as they relate to overall supply man- and coordination of technology, tasks and human com-

agement effectiveness. Given the dynamics of the ponents (Silvestri 1997). Although design is often thought

current competitive global supply landscape, organi- of in terms of organizational structure, an organization’s

zational design concerns are critical to sustained design is much more complex and detailed than the

lines and boxes that appear on an organizational chart

organizational success.

(Champoux 2000).

The current research examines organizational design

features companies use or expect to use when pursuing

procurement and supply objectives. Initially, the paper

summarizes the literature and concludes that minimal

research has focused on the specific design features used

in procurement and supply management. The second

section describes the research and methodology that

support the reported findings. Research questions and

findings appear next, and the fourth section presents

the conclusions and managerial implications that arise

from those findings. The article concludes with an indi-

cation of study limitations and future opportunities as

they relate to organizational design research.

The Journal of Supply Chain

A REVIEW OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN

Management: A Global LITERATURE

Review of Purchasing and

Supply Copyright © August

A comprehensive review of the organizational design

2004, by the Institute for literature covers hundreds of citations and studies, which

Supply Management, Inc. ™ is far beyond the scope of this article. We can, however,

suggest that three major streams of research emerge from

this literature. The first examines the ongoing debate

4 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

between strategy and structure and incorporates an exten- or hybrid structures will increase. This reflects a growing

sive discussion of mechanistic versus organic organiza- need for purchasing to integrate with other parts of the

tional designs. A second research stream examines factors organization, particularly technical groups during new

that influence an organization’s design or cause an orga- product development.

nization to change its design. A third stream examines A discussion of specific organizational design features

the broad types of designs or structures organizations put occurs mainly within two areas — in case analyses reported

in place, including functional, place, product or multi- in CAPS focus studies and in practitioner publications.

divisional designs. Obviously, organizational design Leenders and Johnson (2000, 2002) provide many case

encompasses much more than purchasing and supply examples that address organizational design issues. Their

management, but this article focuses on design research case studies examine changes in supply chain responsi-

specifically relevant to purchasing and supply management. bilities and structural changes in supply organizations. On

Fearon (1988), in a study of purchasing organizational the practitioner side, Purchasing magazine presents its

relationships, extensively examined the characteristics of Medal of Excellence Award annually to a company the

the chief purchasing officer, the average size of the pro- editors feel demonstrates leading supply management

fessional purchasing staff, the reporting level of purchasing, practices. The article that accompanies the award usually

purchasing responsibilities and other factors related to provides insight into the winner’s organizational design.

organizational design. Fearon and Leenders (1996) per- Although they provide interesting and practical perspec-

formed a follow-up to Fearon’s 1988 study, which afforded tives, these articles are usually anecdotal and represent

a unique opportunity to trace longitudinal changes best practices at select firms.

involving 118 firms that participated in the 1988 and Researchers have investigated specific design topics (i.e.,

1995 research. Johnson, Leenders and Fearon (1998) and JIT or international sourcing structures) and examined

Johnson and Leenders (2001) presented further exten- broad changes and trends (i.e., flattening of structures

sions of the 1988 and 1995 studies. or managing the “white space”), but no research has

Other organizational research related to purchasing and focused on evaluating a comprehensive set of design

supply management includes Cavinato (1992), who argued features or how these features may support supply man-

that most procurement organizations are described and agement effectiveness. This research attempts to fill this

analyzed with reference to seven basic organizational void by evaluating specific design features within pur-

models. Germain and Droge (1998) examined whether chasing and supply management.

the internal organizational designs of JIT buying firms

differ from non-JIT buying firms in terms of formaliza- RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE

tion, integration and decentralization. Giunipero and This research, which is exploratory in nature, collected

Monczka (1990) examined the organizational structures survey data on the use of specific organizational design

used by multinational corporations to conduct interna- features within procurement and supply management.

tional purchasing activities; Pooley and Dunn (1994) Respondents were supply professionals from manufac-

completed a longitudinal study of purchasing positions turing firms selected randomly from the membership

from 1960 to 1989. Finally, Pearson, Ellram and Carter database of the Institute for Supply Management™.

(1996), in their study of the electronics industry, exam- The design features included in the survey were selected

ined the organizational standing of purchasing compared on the basis of executive focus groups (primarily with

to other functional groups, the strategic versus clerical manufacturing firms), firsthand experiences, case studies

nature of purchasing tasks, and the status and recogni- and literature reviews. Qualitative research helped iden-

tion of purchasing within the firm. tify a list of features upon which firms rely. A series of

Several studies have focused on various trends and a priori research questions, described later, provided

changes and their implications for organizational design. guidance during survey design.

Carter and Narasimhan (1996) identified future directions Two supply managers and two academicians reviewed

in purchasing and supply management, several of which a preliminary version of the survey for clarity and com-

related to design. They posit that management of the pleteness before wide-scale distribution. Their comments

“white space” (i.e., the interfaces between purchasing and resulted in minor modifications and several additions to

other units across the supply chain) will become increas- the final survey. Of the approximately 1,000 ISM members

ingly important for supply executives. Furthermore, Carter in the United States who received surveys, 173 returned

and Narasimhan predicted a flattening of organizational responses, yielding just over a 17 percent response rate.

structures through the expanded use of self-managed teams. During survey distribution, the researcher excluded any

In their longitudinal study of trends and changes mailing label that did not have a company name, reducing

throughout the 1990s, Monczka and Trent (1998) con- the possibility that retired ISM members received a survey.

cluded that the number of purchasing groups organized Care was also taken to avoid sending multiple surveys

by commodity will continue to decrease gradually, while to the same organization.

the number of purchasing groups organized by end item

The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004 5

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

The 17 percent response rate, while somewhat low, is their current organizational design supported the attain-

comparable to other supply chain research that relied ment of procurement and supply objectives. Although

on mail surveys. Min and Emam (2003) cite a number achieving these objectives may enhance firm performance,

of studies, including their own, revealing that response this research did not focus on that linkage.

rates of less than 20 percent for mail surveys are not Data analysis involved the use of descriptive statistics,

uncommon in the supply chain literature (see Mentzer, correlations and t-tests between groups. Factor analysis

Shuster and Roberts 1992; Murphy and Daley 1994; involving all the features that respondents evaluated failed

Carter and Narasimhan 1996a, 1996b; Pedersen and Gray to converge on a clear set of clusters or factors. This pro-

1988; and Sum, Teo and Ng 2001). hibited data simplification or reduction into a smaller

Nonresponse bias can be also an issue. A test for non- set of factors.

response bias compared the first 60 and the last 60 sur-

veys received; it revealed no statistically different responses RESEARCH QUESTIONS

or characteristics between the two groups. Furthermore, This study investigated a number of a priori research

these 60 firm subsamples did not differ statistically from questions related to current and future design features

the combined sample of 173 firms. A bias regarding sur- within procurement and supply management, and to a

veys returned later rather than earlier over the data col- lesser degree in supply chain management. This research

lection period is not a concern. also investigated the relationship between perceived design

effectiveness and (1) the features that firms emphasize,

As expected when using the ISM database, responding

(2) firm size, (3) the reporting level of the highest pro-

companies showed a wide variance in terms of size (as

curement office and (4) the placement of decision-making

measured by annual revenue). This variability provided

authority. This section presents the findings for the

a hoped-for opportunity to divide the responding firms

research questions.

into segments.1 The distribution based on sales revealed

three groupings: smaller (56), medium (46) and larger

Research Question 1: What Design Features Do

(65) firms. These groupings formed the basis for seg-

Procurement and Supply Organizations Currently

menting the sample. These segments result from logical

Rely On?

breaks in terms of sales rather than a U.S. government

Table V presents the highest-rated organizational

designation of small, medium or large. Segmenting the

design features that firms currently use or rely on, seg-

sample by size allows for meaningful comparisons across

mented by size. This table reveals that the size of firm

the data. Tables I-IV provide insight into the 173 par-

affects the design features relied on or emphasized as

ticipants in this research. Attempts to compare demo-

well as the overall level of reliance. Across the 29 design

graphic profiles of respondents against an overall

features evaluated by respondents, smaller firms average

demographic profile of ISM companies in SIC 20-38

2.59 in total average use, medium firms average 3.48,

(manufacturing firms) were unsuccessful due to the

and larger firms average 3.98 (all averages are on a

unavailability of such data.

seven-point scale).

The survey included demographic data and other

Larger firms differ from smaller firms in terms of scope,

questions of interest but focused primarily on the cur-

complexity and available resources. They are much more

rent and expected use of specific design features in pur-

likely to have operations that are worldwide rather than

chasing and supply management, which the Appendix

local or regional (scope) with more organizational levels

identifies. Tables presented throughout this article abbre-

covering a wider array of business and product lines (com-

viate the descriptions of these items to conserve space.

plexity). These firms emphasize certain design features

Most of the design features in the Appendix relate to

in order to coordinate and integrate a globally complex

supply management but several relate to supply chain

organization. Larger firms are also more likely to have

management.

greater access to the human and financial resources that

This research did not attempt to assess the overall effect allow them to put in place certain features.

of organizational design on firm performance. Too many

Table V shows that each segment emphasizes collocation

factors, including factors that are external to supply man-

of purchasing and other organizational members, partic-

agement, determine a firm’s success. Positive relationships

ularly internal customers (such as operations or tech-

between organizational design features and overall firm

nical personnel). Physical collocation of purchasing and

performance might result in spurious conclusions. Instead,

marketing is not highly emphasized. Since purchasing

respondents evaluated the degree to which they perceived

resides as a support function within the value chain,

collocation offers a way to integrate with internal cus-

1

tomers, understand their requirements and respond to

For this article, the firms were segmented according to annual sales

revenue. For a white paper detailing the complete findings for the

their needs (Porter 1985).

study, a presentation that details many of the design features Teams are an important element of current organiza-

included in the survey, or a copy of the survey instrument, please tional design. Each segment, for example, emphasizes

send a request to rjt2@lehigh.edu.

6 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

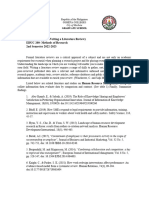

Table I

SIZE OF PARTICIPATING FIRMS BASED ON SALES

Total Sample Smaller Firms Medium Firms Larger Firms

Number of Firms 167 56 46 65

Average Sales $6,008,800,000 $56,122,400 $813,711,100 $14,734,070,000

Standard Deviation $14,641,370,000 $42,883,500 $416,968,500 $20,621,570,000

Median Sales $850,000,000 $46,000,000 $800,000,000 $6,500,000,000

Range $500,000- $500,000- $200,000,000- $2,000,000,000-

$126,000,000,000 $160,000,000 $1,700,000,000 $126,000,000,000

Note: Total sample size is 173 firms. Six firms are not included in this table because they did not provide sales data due to confidentiality reasons.

Table II

PROFESSIONAL LEVEL OF RESPONDENT

Total Sample Smaller Firms Medium Firms Larger Firms

Buyer or Operational Level 26.2% 32.1% 22.2% 21.5%

Manager 40.7% 48.2% 37.8% 38.5%

Director 26.7% 16.1% 35.6% 29.2%

Vice President 6.4% 3.6% 4.4% 10.8%

Executive Vice President 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0%

President or CEO 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% 0.0%

Table III

TYPE OF INDUSTRY WHERE RESPONDING COMPANIES COMPETE

Total Sample Smaller Firms Medium Firms Larger Firms

Consumer Durable Goods Mfg. 17.0% 21.4% 22.2% 9.2%

Consumer Non-Durable Goods Mfg. 15.0% 8.9% 11.2% 23.2%

Distribution or Wholesaling 1.2% 1.8% 2.2% 0.0%

Gas or Oil Production/Distribution 1.2% 1.8% 2.2% 0.0%

Healthcare Provider or Services 1.2% 1.8% 0.0% 1.5%

Industrial Capital Goods Mfg. 21.1% 21.4% 22.3% 18.5%

Industrial Non-Capital Goods Mfg. 22.2% 21.4% 24.4% 21.5%

Industrial or Contract Services 4.1% 5.4% 2.2% 4.6%

Raw Material Production/Mining 4.1% 5.4% 2.2% 4.6%

Telecommunications 6.4% 7.1% 2.2% 9.2%

Tourism and Related Services 0.6% 1.8% 0.0% 0.0%

Transportation and Related Services 4.1% 1.8% 6.7% 4.6%

Utility or Energy Provider 1.8% 0.0% 2.2% 3.1%

Table IV

TOTAL PURCHASES AS A PERCENT OF SALES REVENUE

Total Sample Smaller Firms Medium Firms Larger Firms

1-20% 14.2% 20.0% 13.6% 7.7%

21-40% 26.1% 25.5% 25.0% 25.0%

41-60% 36.7% 40.0% 36.3% 36.0%

61-80% 21.3% 12.7% 18.2% 29.7%

81-100% 1.7% 1.8% 6.9% 1.6%

Average 41-50% 41-50% 41-50% 51-60%

The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004 7

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

product development teams that include procurement and purchase consortium as a top-10 design feature. Larger firms,

supply representatives. This is consistent with earlier perhaps in an effort to overcome inefficiencies and dupli-

research that revealed three-fourths of companies relied cation, rate highly a shared services model and structure

on cross-functional teams to support product development that coordinates common activities or processes across busi-

(Griffin 1997). Although only 20 percent of the design ness units or locations.

features evaluated in this research involved teams, three

of the seven most widely used features at larger firms Research Question 2: What Design Features Will

are team related. Two of the seven most widely used fea- Procurement and Supply Organizations Rely On

tures at smaller and medium-size firms are team related. Over the Next Three to Five Years?

Overall, the use of teams is a popular design option. Table VI presents the 10 highest-rated design features

A number of other features are common to all three that firms expect to put in place over the next three to

segments. These include specific individuals assigned respon- five years. Shaded items represent features that are part

sibility for managing key supplier relationships, including supply of Table VI but not part of Table V (highest-rated current

chain alliances; lead buyers or site-based experts designated features). Non-shaded items appear in both tables. Each

to manage non-commodity or non-centrally coordinated items of the 29 design features shows an increase in expected

or services; and regular strategy/performance presentations by usage over the next three to five years, which is common

the CPO to the president or CEO. Related to presentations when asking respondents to project forward.

by the CPO is a higher-level CPO who has a procurement New items appearing in Table VI for larger firms include

and supply-related title, which is rated highly by medium formal strategy coordination and review sessions between

and larger firms. functional groups and formal procurement and supply

Several features are unique to each segment. Smaller strategy coordination and review sessions between busi-

firms, perhaps in their effort to overcome volume disad- ness units or divisions. Medium-size firms expect to con-

vantages, rate membership and participation with a recognized tinue their emphasis on formal strategy coordination

Table V

RESEARCH QUESTION 1: CURRENT ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN FEATURES

Smaller Firms Avg Medium-Size Firms Avg Larger Firms Avg

Physical collocation between 4.36 Specific individuals assigned 4.77 Specific individuals assigned 5.09

procurement personnel and key responsibility for managing key responsibility for managing key supplier

internal customers supplier relationships relationships

Specific individuals assigned 3.87 Physical collocation between 4.30 Centrally coordinated commodity 4.89

responsibility for managing key procurement personnel and key teams that develop and implement

supplier relationships internal customers companywide supply strategies

Physical collocation between 3.86 Centrally coordinated commodity 4.22 Cross-functional or self-managed 4.75

procurement and technical teams that develop and implement teams that manage some or all of the

personnel companywide supply strategies procurement and supply process

Formal strategy coordination and 3.45 Lead buyers or site-based experts 4.18 Lead buyers or site-based experts to 4.68

review sessions between functional tomanage non-commodity or manage non-commodity or non-

groups non-centrally coordinated items or centrally coordinated items or services

New product and/or process 3.36 services A higher-level chief procurement officer 4.56

development teams that formally Regular strategy/performance review 4.18 who has a procurement and supply-

include procurement and supply presentations by the CPO to the related title

representatives president or CEO Physical collocation between 4.55

Lead buyers or site-based experts 3.29 Physical collocation between 4.05 procurement personnel and key

designated to manage non- procurement and technical personnel internal customers

commodity or non-centrally New product and/or process 4.02 New product and/or process 4.47

coordinated items or services development teams that formally development teams that formally

Cross-functional or self-managed 3.14 include procurement and supply include procurement and supply

teamsthat manage some or all of representatives representatives

the procurement and supply A higher-level chief procurement 4.02 Regular strategy/performance review 4.45

process officer who has a procurement and presentations by the CPO to the

On-site suppliers to perform 2.91 supply-related title president or CEO

inventory management activities A corporate level steering committee 3.89 A shared-services model and structure 4.38

Regular strategy/performance 2.84 that oversees companywide supply that coordinates common activities or

review presentations by the CPO initiatives processes across business units or

to the president or CEO Formal strategy coordination and 3.71 locations

Membership and participation with a reviewsessions between functional Physical collocation between 4.35

recognized purchase consortium 2.82 groups procurement and technical personnel

Average across 29 design features 2.59 Average across 29 design features 3.48 Average across 29 design features 3.98

N = 56 N = 46 N = 65

1 = Do not use, rely on or feature; 4 = Somewhat use, rely on or feature; 7 = Extensively use, rely on or feature.

8 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

and review sessions between functional groups and firms it moved from 13th to eighth. The Conclusions

between business units or divisions. Smaller firms also and Managerial Implications section discusses this

expect to stress strategy coordination and review sessions, important trend in more detail.

although at lower usage levels. An emphasis on these An additional item of interest for larger firms relates to

features points out the important role that organizational an expected increase in formal separation of strategic and

design plays in coordinating procurement and supply tactical procurement and supply responsibilities, personnel,

activities and supporting integration across functional positions and structure. Larger firms indicate that the

groups and locations. decision-making authority is decentralized, with some

Table VI reveals a continued reliance on teams, partic- controlled procurement (average 4.00/6 where 1 = highly

ularly to support product development. Three of the 10 decentralized and 6 = highly centralized). This segment

items for medium and larger firms listed in this table are expects a shift toward moderate centralization over the

team related. Both segments expect a higher reliance on next three to five years (to 4.46/6). This trend is consis-

project teams that work on specific procurement and supply tent with earlier research revealing a gradual shift toward

tasks. centrally led purchasing (Monczka and Trent 1998; Carter

Probably the most significant change between current and Narasimhan 1996a). Separation of responsibilities

and expected design features is the anticipated increase should become more common as firms develop a cen-

in new product and/or process development teams that include trally coordinated or centrally led supply organization.

suppliers as members or participants. For larger firms, this The Conclusions and Managerial Implications section

item moved from a rank order of 19th for current design cites research by Leenders and Johnson (2000) that pre-

features to 11th for expected design features, for medium- sents a different perspective on this finding.

size firms it moved from 22nd to eighth, and for smaller

Table VI

RESEARCH QUESTION 2: EXPECTED ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN FEATURES

Smaller Firms Avg Medium-Size Firms Avg Larger Firms Avg

Physical collocation between 4.67 Specific individuals assigned 5.27 Specific individuals assigned 5.38

procurement personnel and key responsibility for managing key responsibility for managing key

internal customers supplier relationships supplier relationships

Specific individuals assigned 4.35 Centrally coordinated commodity 5.16 Centrally coordinated commodity 5.35

responsibility for managing key teams that develop and implement teams that develop and implement

supplier relationships companywide supply strategies companywide supply strategies

New product and/or process 5.17

Physical collocation between 4.22 Lead buyers or site-based experts to 5.11 development teams that formally

procurement and technical personnel manage non-commodity or non- include procurement and supply

centrally coordinated items or services representatives

Formal strategy coordination and 4.06

review sessions between functional Formal strategy coordination and 4.86 A higher-level chief procurement 5.16

groups review sessions between functional officer who has a procurement and

groups supply-related title

New product and/or process 3.85

development teams that formally Regular strategy/performance review 4.75 Regular strategy/performance review 5.09

include procurement and supply presentations by the CPO to the presentations by the CPO to the

representatives president or CEO president or CEO

Formal procurement and supply 4.98

New product and/or process 3.85 Project teams that work on specific 4.70

strategy coordination and review

development teams that include procurement and supply tasks

sessions between units or divisions

suppliers as members or participants

Physical collocation between 4.70 Formal separation of strategic and 4.98

Lead buyers or site-based experts to 3.67 procurement personnel and key tactical procurement and supply

manage non-commodity or non- internal customers responsibilities, personnel, positions

centrally coordinated items or services and structure

Formal strategy coordination and 4.68

On-site suppliers to perform 3.65 review sessions between functional A shared-services model and 4.97

inventory management activities groups structure that coordinates common

activities or processes across business

Regular strategy/performance 3.58 New product and/or process 4.68 units or locations

review presentations by the CPO to development teams that include

Formal strategy coordination and 4.95

the president or CEO suppliers as members or participants

review sessions between functional

Formal strategy coordination and 3.45 A higher-level chief procurement 4.68 groups

review sessions between units or officer who has a procurement and Project teams that work on specific 4.89

divisions supply-related title procurement and supply tasks

Average across 29 design features 3.28 Average across 29 design features 4.27 Average across 29 design features 4.63

N = 56 N = 46 N = 65

1 = Do not expect to use, rely on or feature; 4 = Expect to somewhat use, rely on or feature; 7 = Expect to extensively use, rely on or feature.

The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004 9

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

Research Question 3: What Design Features Should • A virtual procurement organizational design fea-

Show the Greatest Increase in Expected Usage turing individuals, groups and/or departments

Over the Next Three to Five Years? linked through IT systems

This question identifies the areas where growth in design • On-site suppliers to perform inventory manage-

characteristics and features are expected to occur across ment activities

the total sample. Consensus exists concerning the design • A formal cross-functional group or team respon-

features that each segment believes will show expected sible for demand and supply planning

growth over the next three to five years. In fact, the first • An organization designed around procurement

seven out of eight items in Table VII are each included and supply processes

as higher-growth items for the smaller, medium and larger • A shared services model and structure that coordi-

segments. The primary difference across segments is the nates common activities or processes across busi-

average rating each design feature receives within each ness units or locations

segment. • Formal strategy coordination and review sessions

Many of the design characteristics and features that between functional groups

show expected growth support integration across the Other features support an expected shift toward central

supply chain. In fact, it is safe to conclude that firms coordination across the procurement and supply func-

expect to use organizational design features to achieve tion. This is consistent with the desire of most firms to

greater integration, both internally and externally, over evolve toward a higher level of central coordination

the next three to five years. Design features that promote within procurement and supply. Firms indicate that

internal and external integration and are expected to they expect to increase use of the following design fea-

show increased usage include: tures that promote central and cross-locational coordi-

• Formal value analysis/value engineering groups nation within procurement and supply.

• New product teams that include suppliers

Table VII

RESEARCH QUESTION 3: ANTICIPATED ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN FEATURE GROWTH

Current Expected

Design Characteristic or Feature Use Use Growth

Formal value analysis/value engineering groups 2.95 4.10 +39%

New product and/or process development teams that include suppliers 3.29 4.49 +37%

as members or participants

A virtual procurement organizational design featuring individuals, groups 2.91 3.94 +35%

and/or departments linked through IT systems

On-site suppliers to perform inventory management activities 3.25 4.29 +32%

Project teams that work on specific procurement and supply tasks 3.39 4.33 +28%

A formal cross-functional group or team responsible for demand and 3.27 4.04 +27%

supply planning

An organization designed around procurement and supply processes 3.23 4.07 +26%

rather than a functional or vertical perspective

Formal procurement and supply strategy coordination and review sessions 3.55 4.43 +25%

between business units or divisions

A shared-services model and structure that coordinates common 3.39 4.16 +23%

activities or processes across business units or locations

Formal separation of strategic and tactical procurement and supply 3.40 4.10 +21%

responsibilities, personnel, positions and structure

An executive position responsible for coordinating and integrating key 3.25 3.89 +20%

supply chain activities

Formal strategy coordination and review sessions between functional groups 3.87 4.62 +19%

Centrally coordinated commodity teams that develop and implement 3.89 4.62 +19%

companywide supply strategies

A corporate-level steering committee that oversees companywide procurement 3.38 3.98 +18%

and supply initiatives

Regular strategy/performance review presentations by the CPO to the 3.86 4.51 +17%

president or CEO

N = 173

Scale: 1 = Do not (expect to) use, rely on or feature; 4 = (Expect to) somewhat use, rely on or feature; 7 = (Expect to) extensively use, rely on or feature.

10 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

• Formal procurement and supply strategy coordina- design effectiveness. Respondents perceive regular strategy/

tion and review sessions between units or divisions performance review presentations by the CPO to the president

• Centrally coordinated commodity teams that or CEO/board of directors and formal procurement and supply

develop and implement companywide supply strategy coordination and review sessions between business

strategies units or divisions as critical components of an effective

• A corporate-level steering committee that oversees design. Both segments also acknowledge the value of a

companywide procurement and supply initiatives shared-services model and structure that coordinates common

• Regular strategy/performance review presentations activities or processes across business units or locations. The

by the CPO to the president or CEO two segments agree that cross-functional or self-managed

The survey showed conclusively that future organiza- teams that manage some or all of the procurement and supply

tional design changes support cross-functional and cross- process and new product and/or process development teams

organizational integration as well as the coordination of that include suppliers as members or participants are impor-

procurement and supply activities across the enterprise. tant design features. Finally, the two segments agree on

the importance of lead buyers or site-based experts des-

Research Question 4: What Is the Relationship ignated to manage non-commodity or non-centrally

Between Organizational Designs That Promote the coordinated items or services.

Attainment of Supply Objectives and the Design The two segments differ in their perception of the fea-

Features That Firms Emphasize? tures that correlate with design effectiveness. For medium-

This question examines the relationship between two size firms, physical collocation between procurement personnel

important variables: the activities firms currently empha- and key internal customers/marketing/technical personnel cor-

size and the respondents’ overall perception of the effec- relates much more closely to perceived design effective-

tiveness of their organizational design. It moves beyond ness than it does for larger firms. Specific individuals assigned

Research Questions 1 and 2, which simply reported on responsibility for managing key supplier relationships, including

the features that firms have or expect to have in place supply chain alliances; formal procurement and supply strategy

without considering the effectiveness of an organization’s coordination and review sessions between units or divisions

design. For this question participants responded to the and cross-functional or self-managed teams that manage some

statement, “Please indicate the degree to which your or all of the procurement and supply process also correlate

current organizational design promotes or impedes the more closely with design effectiveness at medium-size

achievement of your procurement and supply objectives.” firms than at larger firms.

Responses to this question were correlated against the Larger firms perceive the importance of several features

current usage of the 29 design features included in the relevant to the broader topic of supply chain management.

survey. This segment perceives an executive position responsible for

Table VIII, which includes only medium-size and larger coordinating and integrating key supply chain activities from

firms, presents those features that correlate the highest supplier through customer and an executive buyer-supplier

with firms that indicate their current design supports the council or committee that coordinates supply chain activities

attainment of supply objectives. Although 17 design fea- between your firm and your key suppliers as important parts

tures for medium-size firms and 19 design features for of an effective organizational design. This segment also

larger firms correlate at a non-zero level with design values features that relate to centrally led purchasing,

effectiveness, Table VIII reports only the highest 13 cor- including centrally coordinated commodity teams that develop

relations. A logical break in the value of the correlations and implement companywide supply strategies and a higher-

occurred between items 13 and 14 for both segments. level chief procurement officer who has a procurement and

supply-related title. Larger firms also perceive that an orga-

Smaller firms do not rely on or use the features evalu-

nization designed around procurement and supply processes

ated during this study at levels comparable to the medium-

rather than a functional or vertical perspective and project

size and larger firms. Therefore, few features correlated

teams that work on specific procurement and supply tasks

at any meaningful level with smaller firms that indicate

help define an effective design.

their current design promotes the attainment of procure-

ment and supply objectives. Smaller firms do indicate An important point here is that not all of the items in

that regular strategy/performance review presentations by the Table V, which highlights the features with highest usage,

chief procurement officer to the president or CEO/board of appear in Table VIII. Higher usage or reliance on a fea-

directors are an important part of design effectiveness. ture does not necessarily equate to the perceived effec-

Physical collocation between procurement and marketing per- tiveness of that feature. Another important point is that

sonnel is also important to smaller firms that view their size influences the features that are perceived as most

current organizational design positively. important to effective design.

The shaded features in Table VIII represent areas of

agreement between medium-size and larger firms

regarding the features that correlate the highest with

The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004 11

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

Table VIII

RESEARCH QUESTION 4: CORRELATION BETWEEN DESIGN FEATURES AND DESIGN EFFECTIVENESS

Medium Firms Larger Firms

Regular strategy/performance review presentations by 0.661 Regular strategy/performance review presentations 0.561

the CPO to the president or CEO by the CPO to the president or CEO

Physical collocation between procurement personnel 0.604 Centrally coordinated commodity teams that develop 0.498

and key internal customers and implement companywide supply strategies

Cross-functional or self-managed teams that manage 0.515 An executive position responsible for coordinating 0.493

some or all of the procurement and supply process supply chain activities

Cross-functional or self-managed teams that manage 0.491

Lead buyers or site-based experts to manage 0.485

some or all of the procurement and supply process

non-commodity or non-centrally coordinated

items or services Formal procurement and supply strategy coordination 0.481

and review sessions between business units or divisions

Regular strategy/performance review presentations 0.483

by the CPO to the board of directors An executive buyer-supplier council or committee that 0.418

coordinates supply chain activities between your firm

Formal procurement and supply strategy coordination 0.479 and your key suppliers

and review sessions between business units or divisions

Regular strategy/performance review presentations 0.405

Formal strategy coordination and review sessions 0.469 by the CPO to the board of directors

between functional groups A higher-level chief procurement officer who has a 0.401

New product and/or process development teams that 0.458 procurement and supply-related title

formally include procurement and supply representatives Project teams that work on specific procurement and 0.382

A formal cross-functional group or team responsible supply tasks

for demand and supply planning 0.432 A shared-services model and structure that coordinates 0.367

A shared-services model and structure that 0.427 common activities or processes across business units

coordinates common activities or processes across or locations

business units or locations An organization designed around procurement and 0.364

supply processes rather than a functional or vertical

Specific individuals assigned responsibility for 0.426

perspective

managing key supplier relationships

New product and/or process development teams that 0.349

Physical collocation between procurement and 0.424 formally include procurement and supply representatives

marketing personnel

Lead buyers or site-based experts to manage 0.342

Physical collocation between procurement and 0.402 non-commodity or non-centrally coordinated items

technical personnel or services

N = 46 N = 65

All correlations presented in this table are significant at the 0.05 level or lower.

Shaded areas represent common items between the medium-size and larger segment.

Research Question 5: What Is the Relationship that respondents expect a continued shift toward cen-

Between Organizational Designs That Promote tral coordination over the next three to five years.

the Attainment of Supply Objectives and (1) the A positive (although not strong) relationship also exists

Placement of Decision Authority, (2) the Reporting between firms that believe their current design promotes

Level of the Highest Procurement Officer and (3) the attainment of supply objectives and the reporting

Company Size? level of the highest procurement or supply officer. Firms

Results of the survey indicate that a positive (although whose procurement and supply officers report to levels

not strong) relationship exists between firms indicating closer to the highest executive of the business are more

that their current organizational design promotes the likely to believe their current organizational design is

attainment of supply objectives and centrally coordi- effective. As indicated under Research Question 4, the

nated decision authority (see Table IX). In other words, use of regular strategy/performance review presentations by

centralized firms are more likely to believe their current the CPO to the president or CEO correlates most closely

design promotes the attainment of procurement and with respondents who indicate that their current design

supply objectives than are less centralized firms. Recall supports the realization of supply objectives.

12 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

Finally, no statistical relationship exists between a firm’s Table IX

size and the perception of how well a firm’s current orga-

RESEARCH QUESTION 5: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

nizational design promotes the attainment of procure-

EFFECTIVE DESIGNS AND PLACEMENT OF AUTHORITY,

ment and supply objectives. Smaller firms are as likely as

REPORTING LEVELS AND SIZE

larger firms to perceive that their current organizational

design is effective, even though fewer smaller firms per- Current design promotes

ceive their design as leading-edge or innovative. Responses the achievement of supply

to a separate question indicate that only 17 percent of objectives

smaller firms consider any part of their organizational

design as leading-edge or innovative. Nearly 23 percent of Correlation: 0.235

Current placement of

medium firms and over 45 percent of larger firms consider Sig. (2-tailed): 0.002

decision-making authority

N: 171

some part of their organizational design to be leading-edge

or innovative. Innovation in organizational design likely Current reporting level of Correlation: 0.229

represents a different construct from effectiveness in highest procurement or Sig. (2-tailed): 0.003

design. supply officer N: 171

Research Question 6: What Is the Relationship Correlation: 0.053

Between the Reporting Level of the Highest Firms size based on sales Sig. (2-tailed): 0.497

N: 165

Procurement or Supply Management Officer

and Current and Expected Design Features?

The a priori intent of this question was to investigate

whether higher reporting levels correlate to a specific

set of organizational design features. The correlations

is also an essential component of effective designs. For

between the reporting level of the highest procurement

larger firms, five of the top 10 features that correlate with

or supply management officer and current and expected

an effective design (Table VIII) relate to executive posi-

organizational design features demonstrate no statistical

tions and higher reporting levels.

relationships. This is because the three segments (smaller,

medium and larger) indicate a comparable reporting level It is not the formal supply position that makes this design

for the highest procurement officer. In fact, smaller firms feature important. Rather, the visibility and resources asso-

are actually more likely to have the highest procurement ciated with such a position in the corporate hierarchy,

officer reporting one level from or directly to the highest on a par with other functional executives, are critical. Of

executive in the firm than are medium-size and larger course, every functional group within a firm can make

firms. This is not surprising given the simpler structures this same point regarding its need for an executive

maintained by smaller firms. Limited variability across reporting to the highest organizational levels. Purchasing

the reporting level of the highest procurement or supply executives must make the business case why they should

management officer prevents any meaningful compar- have a senior executive who is on a par with other func-

ison against organizational design characteristics and tional executives.

features. It is not likely that many of the design features pre-

sented here (or other progressive supply strategies) will

CONCLUSIONS AND MANAGERIAL become a reality without an executive champion who

IMPLICATIONS has the authority and resources to make necessary changes.

This section extends the findings just presented to The research evidence presented here is quite clear —

draw conclusions and, where appropriate, discusses the companies that seek advantages from their organiza-

managerial implications of those conclusions. Readers tional design must consider the importance of a higher-

should bear in mind that the data presented here relied level procurement officer as well the reporting level of

on responses from industrial firms based in the United that position.

States. These implications may not apply across cultures

or for non-industrial organizations. 2. Firm Size Affects the Type and Intensity of the

Design Features Put in Place.

1. A Higher-Level Procurement Officer Is Critical to Firms that differ widely in terms of size also tend to

Organizational Design Effectiveness. differ in terms of scope, complexity and available resources.

The importance of a higher-level chief procurement As a result, each segment viewed the need to put in place

officer who has access to the highest executive levels is certain design features differently. The partitioning of

evident throughout this research, particularly for medium the total sample based on size allowed meaningful com-

and larger firms. Furthermore, regular strategy and per- parisons and contrasts between the segments. Supply

formance review presentations by the chief procurement managers should review those activities that correspond

officer (CPO) to the president, CEO or board of directors to their particular segment rather than thinking in terms

The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004 13

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

of a combined sample or what firms in a different seg- • Strategy review and coordination sessions

ment plan to do. Some features that larger firms plan between functional groups and locations

to emphasize, for example, simply are not applicable • Higher-level chief procurement officers

to smaller firms. These features should enable organizations to capture

Although the segments have a number of design fea- the benefits of central coordination while avoiding the

tures in common, they also emphasize features that sup- negative perception that internal users or sites often

port their unique requirements. For medium-size and associate with central control.

larger firms, this means relying on features that support Other design features that should become more widely

coordination and integration across the supply chain. used focus on providing a centrally coordinated view of

On the other hand, some features are common to both supply chain management. These include an executive

smaller and larger firms. In particular, an expected buyer-supplier council to coordinate supply chain activi-

emphasis on including suppliers on product develop- ties with suppliers and an executive position responsible

ment teams is a common design feature for all three for coordinating supply chain activities. These features

segments. correlate closely with larger firms that say their current

design promotes the attainment of procurement and

3. A Gradual Shift Toward Centrally Coordinated

supply objectives.

or Centrally Led Purchasing Should Continue.

Throughout purchasing history, purchasing authority 4. The Use of Teams Will Remain a Popular and

has shifted between centralization and decentralization. Even Growing Design Option.

The data from this study reveal that many supply man- A continued reliance on teams supports Carter and

agers, but certainly not all, will witness a shift toward cen- Narasimhan’s (1996a) proposition that a flattening of

trally led purchasing control or coordination, at least for organizations will continue through the increased use of

some decisions and activities. What distinguishes this self-managed teams. While the use of teams as a design

period from others is the intense cost pressure brought feature will remain popular, few studies have established

about by global competition. An inability to raise prices a clear connection between teaming and higher perfor-

promotes the coordination of worldwide purchasing activ- mance, and even fewer have assessed the impact of

ities and the consolidation of purchase volumes in an teaming on corporate performance (Wisner and Feist

effort to minimize total supply costs. 2001). Although groups (i.e., teams) can yield the kinds

Progressive supply managers should think about orga- of benefits envisioned by their builders, they also poten-

nizational design as a way to coordinate purchasing tially have a less desirable side. They can waste the time

activities without necessarily having to group purchasing and energy of members, enforce lower rather than higher

personnel in a central location or to sacrifice responsive- performance norms, create patterns of destructive con-

ness to individual locations or sites. In fact, some pur- flict within and between groups and make notoriously

chasing activities should remain at a decentralized level, bad decisions. Groups can also exploit, stress and frustrate

particularly those involved with day-to-day materials and members — sometimes all at the same time (Hackman

supplier management. Some researchers refer to this as a 1987). Supply managers should plan for and use teams

hybrid approach to decision-making authority (Leenders selectively, remembering the barriers to their effective

and Johnson 2000). use as well as the factors affecting team success (Trent

Centrally led does not necessarily mean central con- 2004). For a discussion specific to the use of purchasing

trol at the corporate level. Centrally led initiatives and teams and the role they play in enhancing overall firm

leadership can also take place at the business unit level. competitiveness, see Johnson, Klassen, Leenders and

Furthermore, some researchers are not convinced that a Fearon (2002).

shift toward central control will necessarily occur. Leenders

5. If Coordination and Integration Across the

and Johnson (2000, 2002) document organizational moves

in both directions. They observe that for many purchasers

Supply Chain Remains a Challenge, Then

the decentralized state is the stable one, and the hybrid Organizational Design May Be Part of the Answer.

and centralized modes are counter to their personal The objectives a firm hopes to achieve will certainly

preference. influence its organizational design. If supply managers

wish to achieve increased coordination and integration

Firms that expect to move toward centrally led or cen-

within and across the supply chain, they may select design

trally coordinated purchasing should consider features

features that support this goal. In fact, a review of Table

that support this type of model. These include:

VII suggests that many of the design features that show

• Centrally coordinated commodity teams expected growth and usage over the next several years

• Formal positions that separate strategic and tac- appear to relate to coordination and integration. Organi-

tical supply responsibilities zational design supports three kinds of integration —

• Lead buyers to manage non-centrally coordi- cross-functional, cross-locational and cross-organizational

nated items (Monczka 1997).

14 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

Coordination across functions and organizations is use of cross-functional teams, particularly teams that fea-

becoming increasingly important to supply managers. ture full-time members, is one indication of a shift toward

Carter and Narasimhan (1996a) noted this trend when a process orientation. An expected growth in organizations

they said the focus in purchasing and supply management designed around procurement and supply processes (see

will shift from functional coordination to managing the Table VII) is another indication of this shift. When orga-

interfaces of purchasing and supply management with nizing around processes, cross-functional team partici-

other functional units, thus leading to “management of pants work concurrently in an environment that features

the white space.” Purchasing and supply managers will the horizontal (i.e., cross-functional) flow of information

increasingly rely on organizational design features to help across the supply chain.

them manage the strategic connections with other func- An expected movement toward horizontal or process

tional groups as well as connections across organizational design features supports Carter and Narasimhan’s (1996a)

boundaries. proposition that companies would increasingly structure

themselves along “key business processes” that extend

6. Collocation of Procurement Personnel Will

from suppliers, across functional boundaries and into a

Become an Important Part of the Organizational firm’s customer base. Evidence from this research reveals

Design Model. that this change is underway, particularly for medium-

This conclusion supports an observation made by size and larger firms.

Pearson, Ellram and Carter (1996), who noted that a closer

In the shift from a functional to a process orientation,

working relationship with research and development,

the process rather than the functional group becomes

marketing and engineering would clearly enhance the

the focal point of an organization’s design. It is unlikely

purchasing function’s reputation. Smaller, medium-size

that firms will ever move totally away from functional

and larger firms all rate the physical collocation of pur-

groupings. The distribution of functional resources into

chasing personnel with other organizational groups as

full-time process units or teams would dilute the functional

an important design feature. Collocation with operations,

expertise and knowledge required to manage a business

an important internal customer, can provide insight into

effectively. The need to maintain a critical mass of func-

supplier performance; awareness of supply requirements

tional knowledge ensures that some functional structure,

in terms of cost, quality, delivery and cycle time; and an

albeit a diminished one, will remain. Moreover, the dra-

understanding of external capacity, material and service

matic changes surrounding a shift from a functional to

needs. Collocation with technical personnel yields insight

a process orientation ensure that any changes will be

into material specifications, product and process tech-

gradual.

nology requirements and new product requirements.

While collocation has not evolved as highly with the 8. New Product Development Teams Will

demand side of the supply chain, some firms will likely Increasingly Include Purchasing and Supplier

conclude that collocation with marketing supports the Representatives.

integration of demand and supply planning. Collocation An expected shift toward a process orientation as well as

with marketing may also offer early insight into new collocation of purchasing with technical personnel pro-

product ideas as well as planned demand shifts due to motes increased purchasing involvement with new

product promotions or price changes. product development teams. Many companies are dis-

Supply managers must consider a number of issues covering that, when it comes to product design and

relating to collocation. First, collocation is not about development, linkages between engineering, purchasing,

simply working in the physical presence of other groups. manufacturing and key suppliers strengthen the design

Rather, it is about embedding the purchasing professional and development process (Milligan 2000). In the best

into the planning systems of the other group. Second, scenarios, development teams can rely on purchasing to

supply managers must determine the amount of time to identify suppliers for early design involvement or for

allocate to collocation. Will purchasing professionals production needs, monitor supply markets and trends,

collocate full-time or part-time? Finally, what reporting question specifications and help the producer meet its

relationships best support collocation? In a typical collo- target costs.

cation model, the purchasing professional maintains a A step beyond purchasing involvement in new product

dotted-line reporting relationship to the collocation group development is supplier involvement. North American

with a solid-line reporting relationship to purchasing. firms have traditionally lagged Asian and some European

counterparts in their involvement of suppliers during

7. Supply Organizations Will Shift Gradually From

new product development (Womack, Jones and Roos

a Vertical to a Horizontal Perspective. 1990; Monczka et al. 2000). Although supplier involve-

A process-orientated organization is designed around ment sounds easy, widespread implementation can be

supply chain processes, such as supplier evaluation and quite a different matter. Earlier research revealed that

selection, new product development, demand and supply confidentiality of information is a major concern to

planning or customer order fulfillment. The extensive

The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004 15

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

most purchasers (Monczka and Trent 1998). Other barriers Research opportunities also exist to explore the impact

include not knowing how to pursue early involvement, that organizational design has on supply effectiveness.

maintaining too many suppliers for a given commodity It is important to broaden the scope of future research

and relationships that are adversarial rather than coop- to identify the effect of various predictors on supply effec-

erative. Given the expected importance of new product tiveness, including the effect of organizational design.

teams that include suppliers, overcoming these barriers Future research could also study a narrower list of design

must become a managerial priority. features in an attempt to identify those features that

relate most strongly to supply effectiveness.

LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR

Case studies can also play an important role in future

FUTURE RESEARCH research. This study evaluated 29 design features as line

Like most research projects, this one has its share of items in a survey. Qualitative studies involving a cross-

limitations. One limitation that affects the generaliz- section of firms can provide detail about those features

ability of the research results relates to the use of U.S. that will be the most relevant over the next three to five

respondents from the industrial sector. Some countries years. For example, if the separation of strategic and tac-

practice very different supply management techniques tical responsibilities increases, what tasks do supply man-

compared to their U.S. counterparts, which could affect agers consider strategic? If supplier councils become

the kinds of organizational design features they put in more important, how do leading companies structure

place. Furthermore, non-industrial firms, a large segment and manage them?

of the economy excluded from this research, may per-

Next, a longitudinal approach to data collection could

ceive organizational design issues differently than man-

validate trends and changes affecting organizational

ufacturing firms.

design. Because respondents may be overly optimistic

A second limitation involves the use of cross-sectional or uninformed when projecting from a point in time, the

data, which prevents the identification of changes that projections they make are of dubious accuracy (Monczka

preceded data collection or changes that will occur after and Trent 1995).

data collection. The use of cross-sectional data makes it

This research did not consider the impact of procure-

difficult to validate the expected organizational design

ment outsourcing as it relates to organizational design.

changes reported here or to speculate on the causes that

Future research should consider the emerging trend of

drive an organization to select a certain design feature.

procurement outsourcing and its design implications.

A third limitation is one that affects most survey research. Finally, this research did not develop procurement orga-

Since individuals rather than groups typically complete nizational models and the guidelines for selecting a model

surveys, can one individual speak for an entire organiza- or structure based on firm strategy, size, industry, pro-

tion? Does that individual have the insight to evaluate duction methods or technology. Research opportunities

the survey questions accurately? Ideally, individuals who exist to develop robust models of organizational design

are not comfortable with the questions asked would self- that consider a variety of factors beyond those included

select out of the sample by not responding, collaborate in this research.

with others who have the necessary insight or forward

the survey to someone who is capable of responding CONCLUSION

correctly. In 2001, the Corporate Executive Board published a

A final limitation concerns the database that provided report that said purchasing executives, to be successful,

respondent names. While the Institute for Supply must consider how their organizational structure can

Management™ membership roster provides a comprehen- enable substantial improvements in performance and

sive directory of U.S. supply professionals, by no means operational excellence. Additionally, a research study has

does it include all members of the profession or all orga- proposed that firms must excel within four enabling areas

nizations that have purchasing and supply groups. This before they can pursue complex and progressive supply

research was limited to members of a specific professional strategies (Monczka 1997). These areas include measure-

organization, many of whom work for companies that ment and evaluation, information technology, human

are likely quite sophisticated in purchasing and supply resource management and organizational design. An

management. effective design helps provide the foundation upon which

This research topic also offers opportunities for a firms can pursue progressive supply strategies.

future stream of work related to organizational design. While other supply management topics may generate

First, organizational design is not a topic limited to U.S. more excitement than does organizational design, man-

firms. Similar research involving non-U.S. firms could agers should not overlook the role that an effective

provide interesting insights and comparisons. Design design can play in enhancing supply management per-

research involving non-industrial organizations would formance. In today’s globally competitive environment,

allow for meaningful comparisons against industrial managers cannot afford to overlook any area that has

organizations. the potential to improve performance.

16 The Journal of Supply Chain Management | Summer 2004

1745493x, 2004, 2, Downloaded from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2004.tb00170.x by <Shibboleth>-student@ucd.ie, Wiley Online Library on [16/04/2024]. See the Terms and Conditions (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/terms-and-conditions) on Wiley Online Library for rules of use; OA articles are governed by the applicable Creative Commons License

The Use of Organizational Design Features in Purchasing and Supply Management

REFERENCES Min, H. and A. Emam. “Developing the Profiles of Truck

Carter, J.R. and R. Narasimhan. “Purchasing and Supply Drivers for Their Successful Recruitment and Retention,”

Management: Future Directions and Trends,” International International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics

Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, (32:4), Fall Management, (33:2), 2003, pp. 149-162.

1996a, pp. 2-12. Monczka, R.M. Global Electronic Benchmarking Network Supply

Carter, J.R. and R. Narasimhan. “Is Purchasing Really Excellence Model and Research, Michigan State University, East

Strategic?” International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Lansing, MI, 1997.

Management, (32:1), Winter 1996b, pp. 20-28. Monczka, R.M., R. Handfield, T.V. Scannell, G. Ragatz and

Cavinato, J.L. “Evolving Procurement Organizations: Logistics D.J. Frayer. New Product Development: Strategies for Supplier

Implications,” Journal of Business Logistics, (13:1), 1992, pp. Integration, Quality Press, Milwaukee, WI, 2000.

27-35. Monczka, R.M. and R.J. Trent. Purchasing and Sourcing Strategy:

Champoux, J.E. Organization Behavior — Essential Tenets for a Trends and Implications, Center for Advanced Purchasing

New Millennium, South-Western College Publishing, Studies, Tempe, AZ, 1995.

Cincinnati, OH, 2000, p. 325. Monczka R.M. and R.J. Trent. “Purchasing and Supply

Corporate Executive Board (Procurement Strategy Management: Trends and Changes Throughout the 1990s,”

Council), “Innovative Purchasing Structures,” white International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management,

paper, Washington, DC, November 2001. (34:4), Fall 1998, pp. 2-11.

Fearon, H.E. Purchasing Organizational Relationships, Center for Murphy, P.R. and J.M. Daley. “A Comparative Analysis of

Advanced Purchasing Studies, Tempe, AZ, 1988. Port Selection Factors,” Transportation Journal, (34:1), 1994,

pp. 15-21.

Fearon, H.E. and M.R. Leenders. Purchasing’s Organizational

Roles and Responsibilities, Center for Advanced Purchasing Pearson, J.N., L.M. Ellram and C.R. Carter. “Status and

Studies, Tempe, AZ, 1996. Recognition of the Purchasing Function in the Electronic

Industry,” International Journal of Purchasing and Materials

Germain, R. and C. Droge. “The Context, Organizational Management, (32:2), Spring 1996, pp. 30-36.

Design, and Performance of JIT Buying Versus Non-JIT

Buying Firms,” International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Pedersen, E.L. and R. Gray. “The Transport Selection Criteria

Management, (34:2), Spring 1998, pp. 12-18. of Norwegian Exporters,” International Journal of Physical

Distribution and Logistics Management, (28:2), 1988, pp. 108-

Giunipero, L.C. and R.M. Monczka. “Organizational 120.

Approaches to Managing International Sourcing,”

International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Pooley, J. and S.C. Dunn. “A Longitudinal Study of

Management, (20:4), 1990, pp. 3-12. Purchasing Position: 1960-1989,” Journal of Business Logistics,

(15:1), 1994, pp. 193-214.

Griffin, A. “The Effect of Project and Process Characteristics

and Teams on Product Development Cycle Time,” Journal of Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage, The Free Press, New York,

Marketing Research, (34), February 1997, pp. 24-35. NY, 1985.

Hackman, J.R. “The Design of Work Teams.” In J.W. Lorsch Silvestri, G.T. “Occupational Employment Projections to