Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Khasbani (2019) EMI IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION Theory and Reality

Khasbani (2019) EMI IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION Theory and Reality

Uploaded by

dari0004Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Khasbani (2019) EMI IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION Theory and Reality

Khasbani (2019) EMI IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION Theory and Reality

Uploaded by

dari0004Copyright:

Available Formats

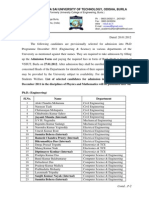

Englisia MAY 2019

Vol. 6, No. 2, 146-161

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION

IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY

EDUCATION: Theory and reality

Imam Khasbani

University of Bristol, United Kingdom

ik17509@my.bristol.ac.uk

Manuscript received February 26, 2019, revised June 17, 2019, first published June 19, 2019, and

available online June 19, 2019. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22373/ej.v6i2.4506

ABSTRACT

The globalization phenomenon marked by the flow of people movements, the

advancement of informational technology, and the shrinking price of transportation

has brought people around the world into one global community. Comprised by

people from diverse linguistic backgrounds, this community sees the need to use a

common language to bridge the communication gap. With a long-established

economic and political power, English comes to the forefront as a global lingua

franca. With its growing and pervasive influence, the need to learn English has never

become more apparent. This need is often translated by government into language-

in-education policy. This paper, to start with, will observe how language policy and

globalization build a causal relationship. In the section that follows, language-in-

education policy in Indonesian context will be presented. The following part will

move on to discuss the use of EMI in Sekolah Berstandar Internasional (SBI)-

International Standard School in Indonesia. In the end, a reflection and conclusion

of EMI in Indonesia context will be discussed. In doing so, this paper employs

literature study approach to explore the EMI practice in Indonesian schools. All

relevant information was collected from several sources such as books and journal

articles. The information was then utilised to build on discussions on existing

theoretical framings, language policy and globalization, and on language-in-

education policy and practice in Indonesia.

Keywords: English as medium of instruction; Sekolah Berstandar Internasional;

Language policy; language-in-education policy; globalization

Imam Khasbani

INTRODUCTION

Language policy is most conceptually defined as any organized interposition

of language’s use conceptualized by an authority of a community and defended by

law (Spolsky, 2004). Language policy plays an inherent role in political activities of a

nation by reflecting the sovereignty of government (Wright, 2004) while at the same

time also mirroring ideologies about language hold by the policy maker (Ricento,

2006). This concept offers an explicit reference that language policy plays such a

powerful force in a socio-political context that can manipulate a specific group of

people to do particular actions. Due to its support usually coming from the highest

authority, language policy is oftentimes used by a government as a tool to exert

ideological beliefs to broader societal contexts. And more often and not, it is

pedagogical settings through language-in-education policy that become common

breeding grounds in which those ideological motivations are translated and put into

practice.

Language-in-education policy is commonly described as a set of education

system principles that works as a basic framework in choosing a language

approach used in classrooms. In its practice, this policy acts a rule of thumb in

settling on what language to teach in the classroom, how teaching and learning of

the chosen language take place and which assessment methods employed to gauge

learners’ language attainments. In the domain of English as a foreign language

(EFL) learning, one of the examples of language-in-education policy products is

English as a medium of instruction (EMI). As put forward by Dearden (2014), EMI

is “the use of the English language to teach academic subjects in countries

or jurisdictions where the first language (L1) of the majority of the population is

not English” (p.4). Dearden further argued that the employment of EMI in the sphere

of education in EFL countries has faced a growing trend in last recent years, with

more education systems in these countries witnessed to lean strong support towards

the implementation of EMI in their institutions.

The fact that English that gains more important status and pervasive power in

the current global situation, where almost all people are now expected to have “the

ability to express [themselves] clearly and appropriately” (Al-Mahrooqi, 2012,

p.125) by using the language and the fact that the number of people speaking

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 147

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

English as L2 (second/foreign language) has exceeded the number of native

speakers in the inner circle countries (e.g., the UK and USA) put together (Llurda,

2004; Kachru, 2005) has made EMI become one of the most-administered

approaches in EFL countries. Besides that, the fast development of technology and

digital communication as an out-turn of globalization also become aspects that can

be taken into account of why EMI is now becoming such a global trend in English

education arenas. With a somewhat effortless access to internet, English interactions

involving anyone from all over the world can now take place in a matter of seconds.

And what it means with English education is that the demand of a teaching

approach that is capable to make English learners communicate effectively has

never been higher. Then, it could be taken as read that language policy and the

emerge of EMI have always been intimately connected to the globalization

phenomena.

GLOBALIZATION AND LANGUAGE POLICY: HOW THEY ARE INTERCONNECTED

The notion of globalization, most commonly thought as transactional

situation allowing people coming from different background varieties to exchange

interests within economic, political, and bureaucratic interaction (Collins,

Slembrouck, & Baynham, 2009), has started to roar since the last few decades. The

salient privilege of enjoying the interdependences across regions and continents,

also an open chance of exercising authority (Held, McGrew, Goldblatt, & Perraton,

1999) has led more and more countries to take part in the celebration of what

Kenichi Ohmae (as cited in Guillén, 2001) conceptualized as Borderless World.

Then, how is language policy related to this concept? Tollefson (2013) states in his

work that “the process of globalization, therefore, has direct and immediate

consequences for language policies in education” (p.19). However, one can argue

that it is political and economic interests as well as advancement of

telecommunications that bring people from different cultural backgrounds together

to engage in a communication (Singh, Zhang, & Besmel, 2012) that initiate

language policies in many countries. The significant advancement of transportation

and technology has helped create the concept of borderless interaction to step on

another level of reality into what Mcluhan (1994) proposed as global village-a

148 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

community consisting of different people connected by telecommunications- and the

age of information- the change of medium of communication (e.g., from radio to

telephone). These ideas later underpinned the concept of culture-ideology of

consumerism by Glasgow-born sociologist Leslie Sklair (as cited in Guillén, 2001).

Sklair argued that the notion of culture-ideology of consumerism, mainly related to

the symbols of lifestyle and self-image, has brought far-reaching consequences such

as standardization of desire and taste. Besides that, culture also plays a vital role in

changing people's mind as well as their lifestyle through its hegemony. Culture,

through its potentially strong value and power, could invade another weaker culture

that will later result in the absorption of strong culture values (Xue & Zuo, 2013).

As for English language, the development of the language in postcolonial

countries and the fact that English is the language of the United States, the centre of

economy, politics, military power and mainstream culture (Phillipson, 1992) give

rather an adequate explanation on how English, then, becomes the most-desired

language many people wished to master. The prevalent influence of English in the

global contexts had affected how most people perceive the language by getting

them to believe that English plays such a vital role in their lives by acting as “a

gateway to education, employment, and economic and social practices.” (Guo &

Beckett, 2007, p.119). By mastering the language, it is believed that one can get a

better opportunity and access to education and employement while at the same time

raise their competitivenes in the global markets. This, as a consequence, leads many

governments in EFL countries to acknowledge the needs to equip their people with

the knowledge and ability of the language.

Many scholars and professional in EFL areas have since then been busy

creating and finding ‘the best and suitable’ teaching approach to implement in the

language classrooms (Bowers, 1995). These occurances, according to Sklair’s work

(1994), can be assumed a proof that English has become “the institutionalization of

consumerism through the commodification of culture” and that its mastery will give

“the promise that a more direct integration of local with global capitalism will lead

to a better life for everyone” (p.178). This also at the same time becomes a clear

evidence that English has successfully achieved its hegemonic status that drives many

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 149

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

governments into setting up language-in-education policy to the forefront of the

national agendas to facilitate the countries’ demands of the language.

LANGUAGE-IN-EDUCATION POLICY IN INDONESIA

English and Indonesia share no common history in the way that English does

with some other countries like Malaysia and Singapore. As the postcolonial nations,

Malaysia and Singapore have a long history with British Empire and its language.

English in these countries has been long disseminated and built a strong causal

relationship in the wide range of governmental, societal, and educational sectors

(Higgins, 2003). Meanwhile as the former Dutch empire colony, Indonesia shares a

somewhat much less amount of historical relationship with both Great Britain and

English language in the past. Thus, not much has happened between the nation and

the language since the first introduction of the language until its status in the

present-time Indonesia. English has been maintaining its influence in the country in

these recent decades thanks to the globalization process.

However, unlike the reaction in some developed Asian nations that initially

showed a defensive attitude toward English language, Japan for example, which

discouraged the use and teaching of English in the national curriculum mainly due

to a heightened diplomatic relationship with the USA (Seargeant, 2011) and the

emerge of Nihonjinron-Japanese nationalism movement (Sullivan & Schatz, 2009),

English has received a reasonably enthusiastic welcome in Indonesia. This

phenomenon is arguably caused by the fact that Indonesia perceives the language

as a language of intelligence and high social status (Tanner, 1967). The importance

of learning this global lingua franca has also been narrated on language-in-

education policies issued by the country.

Language policies in Indonesia have changed over time. In the 1950s, few

years after Dutch set their feet off Indonesia, the country’s government appeared to

acknowledge the need to build international relationships with other countries

especially the United States, which has since then put substantial political, economic

and financial influence, through USAID for example (Lowenberg, 1994). This

situation, at the same time, brought English into play on Indonesia education system.

The importance of English emerged as it started to be recognized as a medium of

150 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

international communication. English has, then, become one of the compulsory

subjects to teach at Indonesian schools. However, as stated by Lauder (2008) the

inclination of teaching English at that time did not focus on furnishing students with

the communicative competence-the ability of a language learner to engage in a

conversation effectively and meaningfully in a society where the language they learn

is primarily spoken (Hymes, 1977). According to the national language policy, the

goal of teaching English was to make the neoteric advancement of science and

technology, frequently written in English, more accessible for students (Lowenberg,

1994). The goal set by Indonesian government at that time might resonate the idea

of Greenwood (as cited in Phillipson, 2009) that speculates “science cannot be

advanced without the English language and textbooks and students will make better

progress in the science by taking the English textbooks and learning the English”

(p.65).

Nevertheless, as the globalization idea started to span around the world, its

effects have driven Indonesia to gain more intensive relations with other countries.

The country’s decision to take part on the declaration of Millennium Development

Goal, establish a working relationship with The Organisation for Economic Co-

operation and Development (OECD), and initiate the formation of The Association

of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) that will later prompt the emerge of ASEAN

Economic Community (AEC) become an apparent example of the case. These

national commitments make interactions and business environments more

international. The communication among people coming from different culture

becomes unavoidable. In this situation, different people will bring a different set of

belief when they are interacting and often without a careful observation, a clash in a

communication flow happens. As a consequence, the need of having an intercultural

interaction competence becomes more apparent. Spencer-Oatey and Franklin

(2009) assert that such expertise is important "not only to communicate (verbally and

non-verbally) and behave effectively and appropriately with people from other

cultural groups but also to handle the psychological demands and dynamic

outcomes that result from such interchanges" (p.51). These events have led to the

inevitable change in the focus of the national language-in-education policy. Given

the shift phenomenon in language policies in Indonesia, one can assume what

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 151

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

Spolsky (2004) speculates on the nature of language policy is correct. Language

policy is about choice, he states, be it the choice of a specific sound, dialect, variety,

or skill of the language. It might be implicit or explicit, based on the ideology of an

individual, group of individuals, or authority body.

EMI IN INDONESIA: THEORY, REALITY, AND REVISION

As one of the most-implemented products of a language policy, EMI has

gained its popularity in the last few decades. EMI has been observed in many

educational institutions including, but not limited to, higher education level.

Depending on a specific circumstance, the use of EMI is possible to be extended on

a primary and secondary level (British Council, 2004).

EMI in Indonesia does not enjoy the same euphoria as it does in other Asian

countries (e.g., Singapore, Malaysia, China, or South Korea) where the

implementation of this recent language teaching approach trend gains

unprecedented popularities especially in the higher education level. However, an

effort had been made by Indonesia authority through a new education program

called Sekolah Berstandar Internasional (International Standard School) to put EMI

theory into practice in its primary and secondary education in the hope that students

would benefit the most from the process.

The final goals of Sekolah Berstandar Internasional (SBI) implementation as

mention in the Ministry of Education’s (2009) document are aimed at endorsing

English language use in the classroom that would in the end: attain national

education excellence with the same quality as those in OECD country members,

enable students to acquire global competencies, produce qualified vocational

school leavers that are ready to compete in the global market, and enhance

students’ ability to communicate in English proved by high school students’

achievement on TOEFL score that is higher than 7.5 or TOEIC score that is higher

than 450 for vocational school students.

Whereas some of the stated goals seem good and attainable, others appear

hard if not impossible to achieve, given the educational situation and economic

152 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

status of the country at the time the policy was implemented. One of those seemingly

unachievable goals is where the government tries to reap the same academic

excellence as those of OECD countries’ such as Finlandia by adopting some aspect

of the countries’ curriculum. Albeit not explicitly stated in the policy document what

values of those curriculums Indonesian government intended to emulate, one can

argue that it is English as the language of instruction, as Ministry of Education

(2009) commands on article five and six that teaching activities in SBI are conducted

through English and that teachers should be able to use the language in the

classroom. Although English is not a mandatory language of instruction for all

subjects in SBI where subjects such as civic, religion, Bahasa Indonesia, and history

must be delivered using the national language, a definitive insight can be gained

that the popularity of EMI that many regards as the most recent solution in English

learning has convinced the authority of educational sector in Indonesia to administer

the approach in schools. The fact that the country was still struggling with the issues

around universal enrolment on primary education level, the equitable distribution of

facilities in school, and the small number of qualified teachers (The World Bank,

2007) did not hinder the government to bring their somewhat premature ambition

into existence. This fact provides the feasibility of this global phenomenon in

Indonesia context enough rooms for a critique.

As one might be able to predict, the unprepared implementation of EMI in

Indonesia has brought no fulfilling results. Since its first application in 2006, SBI in

Indonesia has not escaped criticism. Hendarman (2011) argues that in a broader

social context, many critiques have been focused on the issue of inequality, school

tuition, and the program funding. The problem of inequality in education system

highlights the protests of parents from lower economic status claiming the regular

schools where they sent their children to have worse education quality. Better

facilities that the government provides to SBI has created an issue among parents

that there is disproportion contribution of instrumental supports among schools. The

skyrocketing school tuition becomes the next problem. The increasing price in SBI

schools despite the funding they received from regional government budget has

created a significant gap in society. While equality becomes one of Indonesia

education principals, this phenomenon has lead to a situation where children from

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 153

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

wealthy families crowd in on SBI school. The non-less prominent issue is the

obscurity of the SBI funding. As Indonesia government has provided a regional

autonomy since 1999, each province in Indonesia should regulate the funding of

SBI in their area. Many critics have been addressed since many local authorities

failed to provide a clear statement about the school funding to the public.

On a pedagogical context, critiques can be addressed to the issues of

students’ English competency, teachers’ qualification, and language ideology. The

use of English as a medium of instruction assumes that students have adequate skills

to demonstrate their understanding of written and spoken English. The fact that

English is treated as a foreign language in Indonesia would automatically mean that

students do not speak the language as their first language nor do they have enough

spaces to bring it into practice. The low ability of most, if not all, students to tackle

with English will hinder them not only in the teaching-learning process but also in the

general interactions in the class. This phenomenon is also encountered not only in

Indonesian context, in many English as a foreign language (EFL) countries like Korea

or even in a country where English is treated as a second language like Ghana and

Uganda, some research have reported that the use of EMI has resulted on a lower

understanding of students toward subject being taught. In Korea, some students

argue that the use of Korean language to teach subjects' concept will give them a

deeper understanding (Byun et al., 2011; Kyeyune, 2003). While in Uganda, the

study reports that students are still struggling in the classroom as they often

encounter unfamiliar terms that impede their understanding (Owu-Ewie & Eshun,

2015).

A revision that can be offered toward this issue is that an investigation of a

context where a language-in-education policy is going to be implemented should be

done exhaustively and thoroughly. It is essential to bear in mind that there is an

interconnectedness between a language teaching process and the pedagogical

context. One cannot focus on one aspect while ignoring the other. Often than not in

language policy-making process, the authority will adopt a policy’s product for the

reason that it gains a successful story in other countries without having a thoughtful

examination on the product suitability to theirs. The Indonesian government should

have put the general ability of Indonesian students in English into consideration

154 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

before bringing this fancy approach into practice. They also should have been more

aware that students' language will play a crucial role in this program, just like what

Tiffen (1967) states a long time ago, “students should have thorough command of

the English language if he is to be educated in the modern sense of the word” (p.7).

The mastery of an instruction language is the basic requirement for students before

they learn other subjects in the classroom. Besides that, the use of English as the

language in the classroom appears to function as an exposure for students with the

target language so they can acquire the language without consciously learning it.

This principle reflects the idea of a model of second language learning proposed by

Bialystok (1978). It argues that an immersion class-the class providing an intensive

exposure of a target language to students such as those in SBI-will enrich students’

implicit linguistic knowledge (any knowledge stored in a person's brain that can be

called anytime subconsciously in a target language interaction). But it is important

for us to now that it is impossible for any part of a language becomes implicit

knowledge without having passed the process of explicit language knowledge

(knowledge of a language that is acquired consciously). It is highly doubtful for

students, particularly those living in a country like Indonesia where there are very few

exposures of English outside the classroom, to know that a sentence is written in

passive without having learned the rule initially. Therefore, exposing students with

explicit linguistic knowledge before and along the process of SBI program

implementation should have been placed at the centre of government’s attention.

The next issue revolves around the teachers’ capability to use the approach. It

has been a huge issue around the implementation of the language policy’s product

that a lot of teachers are not qualified enough to ensure teaching-learning activities

through English medium takes place effectively in the classroom. British Council’s

(2004) research project reports that as many as 46 out of 55 countries joining the

study, Indonesia is one of the participants, responded that they do not have qualified

teachers to teach using EMI. Although the report does not explicitly state the list of

the country from which the response came, we can assume from the study done by

Ma'arif (2011) that many teachers in Indonesia at the primary and secondary level

still lack English skills. Ma’arif states that in some cases the English skill of the

students is higher than those of the subject teachers. Although the ministry of

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 155

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

education decree mandates the teachers use English along the teaching-learning

process, the majority only use English at the beginning of the class. Whenever the

things become more complex, a shift of English to students’ native language (L1) in

these circumstances seems unavoidable. Not only in Indonesia, in another context

where English becomes a foreign language for the majority of the people like in

China, a research like that of He & Chiang (2016) also found that the inability of

subject teachers to communicate in English has made the teachers frequently switch

to the student first language. It apparently contributed to students’ confusion,

frustration, and inability to absorb the materials and engage in a meaningful

communication.

What these appearances inform is that another common problem may arise

from the implementation of language-in-education policy is “a difference between

the policy as stated (the official, de jure or overt policy) and the policy as it actually

works at the practical level (the covert, de facto or grass-roots policy)” (Schiffman,

1996, p.2). It is worth remembering that the problem is possible to be minimized by

better preparing teachers. As EMI is not primarily designed to teach English subject,

the government should be mindful of the teachers of other subjects’ ability in the

language they do not speak. The fact that there are no higher education institutions

in Indonesia that offer programs to prepare teachers to teach subjects using

international curriculum or through English should have become an alert for them

before setting the program out to the public. Although hiring expatriate teachers

sounds to be practical, it can also be tricky and difficult at times. Foreign teachers at

public school might benefit the students with more exposure to an authentic

communication, but at the same time, they can also pose challenges. Their lack of

an understanding of local educational system and values increase the chance of an

unsuccessful communication in the class (Walkinshaw & Oanh, 2014). Moreover,

we should not ignore the fact that there is inequality issue on public school teachers’

pay in Indonesia and employing teacher from other countries will only biggen the

existing gap. Therefore, in-service teacher training seems to be the only practical

solution in Indonesia context. It is essential for teachers to be familiar with the

curriculum use in SBI as it poses different activities, material, or testing system. Not

156 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

only on the curriculum familiarity, communication skills should also be focused on

in-service teacher training.

Conflicting ideologies is another potential concern. In 1994, Agar (as cited

in Brown & Lee, 2015) states in his work that “culture is in language, and language

isloaded with culture” (p.28). His assertion is later known as languaculture. This

notionindicates that language and culture is build up upon an indivisible

relationship, and thatteaching language is not a value-free process. There have

always been beliefs, values,and ideologies embedded in a language or in its

teaching approach. This issue has also been a concern on Ricento’s (2000)

publication as he stated that language ideology that is often connected with other

ideologies would pose a challenge to the favourable outcome of its application.

One of the ideologies brought by EMI, in this case, is the requirement of students’

active participations in the classroom activities. Alas, this ideology is often viewed as

incompatible in Indonesia educational context. The traditional teacher-centred

techniques that still dominates most of Indonesian school perceive active

participations in the classroom as inappropriate because it is too noisy. This could

be another significant reason why the implementation does not live up to the

authority’s expectation. While teaching subjects through English as a medium of

instruction in Indonesian schools are aimed to equip students with subjects'

knowledge as well as familiarize them with English, teaching activities in the class

seems not to facilitate students to reach the final destinations. The teacher-centered

view also sees the notion of freedom given to students to choose what they want to

learn in the classroom as invalid. While permitting students to make choices about

what and how they want to learn in the classroom will encourage them to participate

and invest in both learning the subjects and using the language (Brown & Lee,

2015), the traditional view often neglects this striking aspect of a learning process.

As a result, classroom activities tend to be monotonous and fail to motivate students

to study. The conflicting ideology may also come from the use of English in school

activities. While Indonesia adopts the ideology of one nation one national language

that was marked by the declaration of the youth pledge in 1928 (Hannigan, 2015),

the use of English as a replacement of Bahasa Indonesia in the public schools has

raised a storm of controversy. The protest from the Indonesian people shows their

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 157

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

concerns about the possibility of the cultural change in Indonesian children. The

problem can be prevented from happening if all aspects from education system are

joined up together in the policy decision-making process. As the policy will influence

not only teacher and students but potentially broader context, there is a need for the

authority not to put their ideas in isolation from others. Joining-up together might

contribute to a better outcome of the product such as the harmony of the approach

and the testing system. We can see that the harmony is not reflected in the ministry

of education decree. While the focus of SBI is on students’ communicative

competence, the fact that the government use TOEFL as an indicator of the goal

achievement is highly questionable.

A DECADE OF EMI: REFLECTION AND CONCLUSION

Although SBI program ended in 2013 as it received considerable critical

responses, the spirit of EMI still exists in the school system in Indonesia, mainly from

non-governmental institutions. Higher demands of English learning come from

parents that are now becoming more aware of the need for English for their

children. Parents’ views of the language are pertinent to what Pennycook (1994)

noted about English. He contends that English is perceived as a powerful tool that

can determine one’s status in the social, educational, and occupational settings. He

later states that English is “a gatekeeper to a position of prestige in society" (p.14).

Many private schools see this opportunity, and with highly renowned international

curriculums (International Baccalaureate®, Cambridge IGCSE, and Montessori)

these schools try to persuade many wealthy parents to send their children to their

institutions. It does not take a long time for these schools to enjoy its popularity.

International Baccalaureate® (2017) reports that there have been 31 schools

offering IB programme at primary years and another 17 and 38 schools at middle

years and diploma respectively. But do these schools with their English-as-a-

medium-of-instruction feature successfully turn students into capable individual not

only in term of using English but also acquiring the subject knowledge? Careful and

intensive studies might be needed to answer such questions. But reflecting all those

stated limitations gives us thought on the sense that ministry of education has not

made enough efforts to translate the concept of English as a medium of instruction

158 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

as it is stated in their policy into feasible and attainable practices in the public-school

classrooms. More mindful preparations rather than the palpable ego of the

authorities that is often proved to steers them into producing a language-in-

education policy without expressing detail instructions should have done to meet the

context of the country and also to translate the language teaching approach into

more practical steps is needed so that the implementation of it will not end as a

waste of time and money.

REFERENCES

Al-Mahrooqi, R. (2012). English Communication Skills: How Are They Taught at

Schools and Universities in Oman? English Language Teaching, 5(4), 124-

130.

Bialystok, E. (1978). A Theoritical Model of Second Language Learning. Language

Learning, 28(1), 69-83.

Bowers, R. (1995). You Can Never Plan the Future by the Past: Where do We Go

with English? In A. Bamgbose, A. Banjo, & A. Thomas (Eds.), New Englishes:

West African Perspective (pp. 87-112). Ibadan: Mosuro.

British Council. (2004). English as a Medium of Instruction- a Growing Phenomenon

Phase 1, [online] Available at

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e552/73e4c948682fd88497090aaddabcce

76ec1f.pdf [Accessed 1 Dec. 2017].

Brown, H., & Lee, H. (2015). Teaching by Principles. New York: Pearson Education,

Inc.

Collins, J., Slembrouck, S., & Baynham, M. (2009). Globalization and Language in

Contact: Scale, Migration, and Communicative Practices. London: Continuum

International Publishing Group.

Dearden, J. (2014). English as a Medium of Instruction- a Growing Global

Phenomenon. British Council

Guillén, M. (2001). Is Globalization Civilizing, Destructive or Feeble? A Critique of

Five Key Debates in the Social Science Literature, 27(1), Annual Review, 235-

260.

Guo, Y., & Beckett, G. H. (2007). The Hegemony of English as a Global Language:

Reclaiming Local Knowledge and Culture in China, 40(1), Convergence, 117-

131.

Hannigan , T. (2015). A Brief History of Indonesia: Sultan, Spices, and Tsunamis:

The Incredible Story of Southeast Asia's Largest Nation. Hongkong : Tuttle

Publishing.

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 159

ENGLISH AS A MEDIUM OF INSTRUCTION IN INDONESIAN PRIMARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION: Theory

and reality

He, J.-J., & Chiang, S.-Y. (2016). Challenges to English-medium Instruction (EMI)

for International Students in China: A Learners' Perspective, 32(4), English

Today , 63-67.

Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D., & Perraton, J. (1999). Global Transformations.

Standford: Standford University Press.

Hendarman. (2011). Kajian Terhadap Keberadaan dan Pendanaan Rintisan

Sekolah. Jurnal Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, 17(4), 373-382.

Higgins, C. (2003). "Ownership" of English in the Outer Circle: An Alternative to the

NS-NNS Dichotomy. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 615-644.

Hymes, D. (1997). Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach.

London: Tavistock Publications Limited.

Indonesia Ministry of Education and Culture. (2009). Penyelenggaraan Sekolah

Bertaraf Internasional pada Jenjang Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah. Jakarta,

Indonesia: Author.

International Baccalaureate®. (2017). INDONESIA. [online] Available at:

http://www.ibo.org/about-the-ib/the-ib-by-country/i/indonesia/ [Accessed 4

Dec.2017].

Kachru, B. B. (2005). Asian Englishes: Beyond the Canon. Hong Kong: Hong Kong

University Press.

Kyeyune, R. (2003). Challenges of Using English as a Medium of Instruction in

Multilingual Contexts: A View from Ugandan Classrooms. Language, Culture,

and Curriculum, 16(2), 173-184.

Lauder, A. (2008). The Status and Function of English in Indonesia: A Review of Key

Factors. Makara Sosial Humaniora, 12(1), 9-20.

Llurda, E. (2004). Non-native-speaker Teachers and English as an International

Language. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(3), 314-323.

Lowenberg, P. (1994). The Forms and Functions of English as an additional

Language: The Case of Indonesia. In A. Hassan, Language Planning in

Southeast Asia (pp. 230-248). Selangor, Malaysia: Percetakan Dewan Bahasa

dan Pustaka.

Ma'arif , S. (2011). Rintisan Sekolah Berstandar Internasional: Antara Cita dan

Fakta. Walisongo, 19(2), 399-428.

Mcluhan, M. (1994). Understanding Media. Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Owu-Ewie, C., & Eshun, E. (2015). The Use of English as Medium of Instruction at

the Upper Basic Level (Primary Four to Junior High School) in Ghana: From

Theory to Practice. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(3), 72-82.

Pennycook, A. (1994). The Cultural Politics of English as an International Language.

Harlow: Pearson Education.

Philipson, R. (2009). Linguistic Imperialism Continued. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan

Private Limited.

160 | Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019

Imam Khasbani

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ricento, T. (2000). Ideology, Politics and Language Policies: Introduction. In T.

Ricento, Ideology, Politics, and Language Policies: Focus on English (pp. 1-8).

Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Ricento, T. (2006). An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method.

Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

Schiffman, H. (1996). Linguistics Culture and Language Policy. New York:

Routledge.

Seargeant, P. (2011). English in Japan in the Era of Globalization. Hampshire:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Singh, N., Zhang, S., & Besmel, P. (2012). Globalisation and Language Policies of

Multilingual Societies: Some Case Studies of Southeast Asia. RBLA, Belo

Horizonte, 12(2), 349-380.

Sklair, L. (1994). Capitalism & Development. London: Routledge.

Spencer-Oatey, H., & Franklin, P. (2009). Intercultural Interaction: A Multidisciplinary

Approach to Intercultural Communication. Hampshire : Palgrave Macmillan.

Spolsky, B. (2004). Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sullivan, N., & Schatz, R. (2009). Effects of Japanese National Identification on

Attitudes Toward Learning English and Self-assessed English Proficiency.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(6), 486-497.

Tanner, N. (1967). Speech and Society among the Indonesian Elite: A Case Study of

a Multilingual Community. Anthropological Linguistics, 9(3), 15-40.

The World Bank. (2007). Investing in Indonesia's Education: Allocation, Equity, and

Efficiency of Public Expenditures. Washington: The World bank.

Tollefson, J. (2013). Language Policies in Education (Second ed.). New York:

Routledge.

Walkinshaw, I., & Oanh, D. (2014). Native and Non-Native English Language

Teachers: Student Perceptions in Vietnam and Japan. SAGE Open, 4(2), 1-9.

Wright, S. (2004). Language Policy and Language Planning. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Xue, J., & Zuo, W. (2013). English Dominance and Its Influence on International

Communication. Theory and Practice in Language Study, 3(12), 2262-2266.

Englisia Vol. 6, No. 2 MAY 2019 | 161

You might also like

- Lawrence SPNDocument11 pagesLawrence SPNPancakebatters100% (2)

- Chapter 1 of Compliance of The Municipal Government in The First District of La Union To The Iloko CodeDocument15 pagesChapter 1 of Compliance of The Municipal Government in The First District of La Union To The Iloko CodeJeamelyn Casana CiprianoNo ratings yet

- Article Critique - MalaysiaDocument4 pagesArticle Critique - MalaysiaRoopa Yamini Fai LetchumannNo ratings yet

- Ghana's Bilingual Education Policy: Prospects and Challenges For ESL EducationDocument12 pagesGhana's Bilingual Education Policy: Prospects and Challenges For ESL EducationNancy Henaku100% (2)

- Effects of Calculator On The Performance of StudentsDocument18 pagesEffects of Calculator On The Performance of StudentsHar ChenNo ratings yet

- Role of English Language in GlobalizationDocument2 pagesRole of English Language in GlobalizationRhufsque Requits0% (1)

- Glocalizing ELT: From Chinglish To China English: Xing FangDocument5 pagesGlocalizing ELT: From Chinglish To China English: Xing FangMayank YuvarajNo ratings yet

- College of EducationDocument6 pagesCollege of EducationAurelio CameroNo ratings yet

- Code SwitchingDocument49 pagesCode SwitchingKhayla RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Incorporating The Idea of Social Identity Into English Language EducationDocument29 pagesIncorporating The Idea of Social Identity Into English Language EducationAmin MofrehNo ratings yet

- MTB-MLE Grooup 13 ReportDocument42 pagesMTB-MLE Grooup 13 ReportAdora ortegoNo ratings yet

- Lang Policy in SADocument17 pagesLang Policy in SARtoesNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document8 pagesModule 1Aurelio CameroNo ratings yet

- MontalvoJose M4 ANALYSIS FINAL DRAFTDocument10 pagesMontalvoJose M4 ANALYSIS FINAL DRAFTJoe MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Farr Et Al-2011-Language and Linguistics Compass PDFDocument16 pagesFarr Et Al-2011-Language and Linguistics Compass PDFFareena BaladiNo ratings yet

- Code-Switching in Filipino NewspapersDocument94 pagesCode-Switching in Filipino NewspapersMerlyn Thoennette Etoc ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Language Governmentality in Philippine Education PolicyDocument19 pagesLanguage Governmentality in Philippine Education PolicyQueen EchavezNo ratings yet

- Desktop Research DraftDocument4 pagesDesktop Research DraftNajla AdibahNo ratings yet

- MTB For RRLDocument38 pagesMTB For RRLLitovic CasillanNo ratings yet

- The New Challenge of The Mother Tongues: The Future of Philippine Post-Colonial Language PoliticsDocument7 pagesThe New Challenge of The Mother Tongues: The Future of Philippine Post-Colonial Language PoliticsChristine AltamarinoNo ratings yet

- 120645-Article Text-332103-1-10-20150806Document11 pages120645-Article Text-332103-1-10-20150806Alejandro PDNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Non-Verbal Behaviour in Intercultural Communication PDFDocument8 pagesAn Analysis of Non-Verbal Behaviour in Intercultural Communication PDFHayoon SongNo ratings yet

- TupasDocument14 pagesTupasSim QuiambaoNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument13 pagesLiterature ReviewJanelle Marcayda BritoNo ratings yet

- English in The WorldDocument19 pagesEnglish in The WorldTrương DuệNo ratings yet

- The Sociolinguistic Situation in SingaporeDocument12 pagesThe Sociolinguistic Situation in SingaporemarshmellohNo ratings yet

- 606 Paper-1Document24 pages606 Paper-1api-609553028No ratings yet

- English Language Education Policies in The People's Republic of China?? PDFDocument54 pagesEnglish Language Education Policies in The People's Republic of China?? PDF何昂阳No ratings yet

- Teaching Culture in EFL: Implications, Challenges and StrategiesDocument5 pagesTeaching Culture in EFL: Implications, Challenges and StrategiesPhúc ĐoànNo ratings yet

- 1.4 Scope and Limitation of The Study The Scope of This Study Is To Document The Normalization of Using Colloquial and Slang WordsDocument8 pages1.4 Scope and Limitation of The Study The Scope of This Study Is To Document The Normalization of Using Colloquial and Slang WordsGWEZZA LOU MONTONNo ratings yet

- Argumentative EssayDocument7 pagesArgumentative Essayedier marquezNo ratings yet

- The Changing Global Economy and The Future of English TeachingDocument15 pagesThe Changing Global Economy and The Future of English TeachingDaniela Caceres KlennerNo ratings yet

- Bilingualism PDFDocument13 pagesBilingualism PDFFarah MalikNo ratings yet

- English As A Lingua FrancaDocument12 pagesEnglish As A Lingua FrancaFlor De AnserisNo ratings yet

- AsiateflDocument24 pagesAsiateflcalookaNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper - Cultural Factors On English LearningDocument27 pagesConcept Paper - Cultural Factors On English LearningMark Dennis AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Gao (2010, June) - To Be or Not To Be 'Part of Them'Document21 pagesGao (2010, June) - To Be or Not To Be 'Part of Them'minhua zhuangNo ratings yet

- 12 Local Challenges To Global Needs in English Language Education in Vietnam: The Perspective of Language Policy and PlanningDocument20 pages12 Local Challenges To Global Needs in English Language Education in Vietnam: The Perspective of Language Policy and PlanningkhugeshieniNo ratings yet

- Reasons For Multilingual Education and Language Policies of Malaysia and The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesReasons For Multilingual Education and Language Policies of Malaysia and The PhilippinesFarhana Abdul FatahNo ratings yet

- CLIL: Content Based Instructional Approach To Second Language PedagogyDocument13 pagesCLIL: Content Based Instructional Approach To Second Language PedagogyArinNo ratings yet

- TASK118716Document10 pagesTASK118716Maria Carolina ReisNo ratings yet

- The Impact of English As A Global Language On Educational Policies and Practices in The Asia-Paci C RegionDocument25 pagesThe Impact of English As A Global Language On Educational Policies and Practices in The Asia-Paci C Regiongkbea3103100% (1)

- The English LanguageDocument4 pagesThe English LanguageMay Thu KyawNo ratings yet

- Monograph - Eil's RoleDocument5 pagesMonograph - Eil's RolePaolo NapalNo ratings yet

- AsiaTEFL V3 N1 Spring 2006 The Global Spread of English Ethical and Pedagogic Concerns For ESL EFL TeachersDocument17 pagesAsiaTEFL V3 N1 Spring 2006 The Global Spread of English Ethical and Pedagogic Concerns For ESL EFL TeachersFelipe RodriguesNo ratings yet

- English As An Official Language in A Multilingual Country: A Glimpse On Pertinent Laws and Regulations in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesEnglish As An Official Language in A Multilingual Country: A Glimpse On Pertinent Laws and Regulations in The PhilippinesezmoulicNo ratings yet

- Samuell, C., & Smith, M.D. (2020) - A Critical Comparative Analysis of Post-Global English Language EducationDocument20 pagesSamuell, C., & Smith, M.D. (2020) - A Critical Comparative Analysis of Post-Global English Language EducationMike SmithNo ratings yet

- 2015 10MMartinezMMoralesGRiveros ECDocument9 pages2015 10MMartinezMMoralesGRiveros ECMagally Martinez RangelNo ratings yet

- L201 B Chapter 13 Summary Notes (Short)Document14 pagesL201 B Chapter 13 Summary Notes (Short)ghazidaveNo ratings yet

- Peters & BurridgeDocument9 pagesPeters & BurridgeJemarie Porre AmorteNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: Literature ReviewDocument25 pagesChapter One: Literature ReviewNassim MeniaNo ratings yet

- IRR Draft 2Document7 pagesIRR Draft 2KIPNGENO EMMANUELNo ratings yet

- Book Review Lin & Martin Decolonization 2Document2 pagesBook Review Lin & Martin Decolonization 2Dikesh MaharjanNo ratings yet

- Key Concepts in Language Learning and Language EducationDocument18 pagesKey Concepts in Language Learning and Language Educationfatimah firdausNo ratings yet

- Article On Applied LinguisticsDocument24 pagesArticle On Applied LinguisticsAhmed AGNo ratings yet

- Elt Ok PDFDocument18 pagesElt Ok PDFFerry ÀéNo ratings yet

- The Medium of Instruction in Ethiopian Higher EducDocument24 pagesThe Medium of Instruction in Ethiopian Higher Educsamiranes167No ratings yet

- Bridging People Through Languages: An Insight On MultilingualismDocument3 pagesBridging People Through Languages: An Insight On MultilingualismKaren Lynn MacawileNo ratings yet

- TH TH THDocument7 pagesTH TH THPaloma EstebanNo ratings yet

- The Gift of Languages: Paradigm Shift in U.S. Foreign Language EducationFrom EverandThe Gift of Languages: Paradigm Shift in U.S. Foreign Language EducationNo ratings yet

- Floris (2014) Learning Subject Matter Through English As The Medium of Instruction Students and Teachers PerspectivesDocument14 pagesFloris (2014) Learning Subject Matter Through English As The Medium of Instruction Students and Teachers Perspectivesdari0004No ratings yet

- Eng For ChildDocument26 pagesEng For ChildAnggi NurulNo ratings yet

- Blair Et Al. (2018) Reimagining English Medium Instructional Settings As Sites of Multilingual and Multimodal TESOL Quarterly - 2018 - BlairDocument24 pagesBlair Et Al. (2018) Reimagining English Medium Instructional Settings As Sites of Multilingual and Multimodal TESOL Quarterly - 2018 - Blairdari0004No ratings yet

- Tutorial Timetable 2024-1Document1 pageTutorial Timetable 2024-1dari0004No ratings yet

- Assessment 1 (A) RubricDocument1 pageAssessment 1 (A) Rubricdari0004No ratings yet

- EDF5638 Assessment 1b TemplateDocument2 pagesEDF5638 Assessment 1b Templatedari0004No ratings yet

- Peng, Y. (2023) A Study On Foreign Language Anxiety Among International Students From ChinaDocument5 pagesPeng, Y. (2023) A Study On Foreign Language Anxiety Among International Students From Chinadari0004No ratings yet

- EDF5638 AT1 Assessment Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument3 pagesEDF5638 AT1 Assessment Frequently Asked Questionsdari0004No ratings yet

- Levinson's Activity Types and GrammarDocument7 pagesLevinson's Activity Types and Grammardari0004No ratings yet

- An Analysis of Three Curriculum Approaches To Teaching English in Public Sector SchoolsDocument42 pagesAn Analysis of Three Curriculum Approaches To Teaching English in Public Sector Schoolsdari0004No ratings yet

- Mercyhurst Magazine - Spring 1989Document28 pagesMercyhurst Magazine - Spring 1989hurstalumniNo ratings yet

- Test Dec 2012Document3 pagesTest Dec 2012Dr-Priyadarsan ParidaNo ratings yet

- Classroom Action Research Alternative Research Activity For TeachersDocument11 pagesClassroom Action Research Alternative Research Activity For TeachersRoisyah ZuliyantiNo ratings yet

- AurangabadDocument8 pagesAurangabadGokila G NairNo ratings yet

- Right To EducationDocument18 pagesRight To Educationparthyadav92100% (1)

- Samsung Scholarship Application 2013Document8 pagesSamsung Scholarship Application 2013Alex CarricoNo ratings yet

- Effective Group Work PPT PresentationDocument56 pagesEffective Group Work PPT Presentationpkj009100% (1)

- Psychology ConsultationDocument18 pagesPsychology ConsultationMichelle RiveraNo ratings yet

- Resume Jake Tavares CalmDocument2 pagesResume Jake Tavares Calmapi-396526283No ratings yet

- Resume TheresabaldwinDocument1 pageResume Theresabaldwinapi-307117603No ratings yet

- Play and The CurriculumDocument3 pagesPlay and The CurriculumawholelottoloveNo ratings yet

- EDU70012: Supervised Professional Experience 2 Assignment 1: Task 3 - Portfolio 100568375 Kevin JeffriesDocument60 pagesEDU70012: Supervised Professional Experience 2 Assignment 1: Task 3 - Portfolio 100568375 Kevin JeffriesKevin JeffriesNo ratings yet

- Preschoolers and Numeracy Development: What Does The Research Say?Document12 pagesPreschoolers and Numeracy Development: What Does The Research Say?Jesa Mina VelascoNo ratings yet

- Allan Seckel's Letter To Mary Ellen Turpel-LafondDocument2 pagesAllan Seckel's Letter To Mary Ellen Turpel-LafondSean HolmanNo ratings yet

- 25-PS-007-Polomolok Creek Is Tomaro, Robert KierDocument43 pages25-PS-007-Polomolok Creek Is Tomaro, Robert KierRobert Kier Tanquerido TomaroNo ratings yet

- Naeyc Standard 6cDocument10 pagesNaeyc Standard 6capi-349144164No ratings yet

- When Children Make The RulesDocument4 pagesWhen Children Make The Rulesapi-254540836No ratings yet

- Culminating-Activity - Q1 - Mod1-Lesson-1-4Document37 pagesCulminating-Activity - Q1 - Mod1-Lesson-1-4Kareen MangubatNo ratings yet

- For Freshmen Students - Admission Guidelines - Mapúa UniversityDocument6 pagesFor Freshmen Students - Admission Guidelines - Mapúa UniversityVictoria OrleansNo ratings yet

- Ofsted Report June 2014Document9 pagesOfsted Report June 2014api-220440271No ratings yet

- Level 7 Diploma in Health and Social Care - (Fast-Track) - Delivered Online by LSBR, UKDocument19 pagesLevel 7 Diploma in Health and Social Care - (Fast-Track) - Delivered Online by LSBR, UKLSBRNo ratings yet

- Director, Rathdown School Performing Arts Academy (Director, RSPAA)Document3 pagesDirector, Rathdown School Performing Arts Academy (Director, RSPAA)The Journal of MusicNo ratings yet

- Contoh CVDocument1 pageContoh CVlindaNo ratings yet

- Christine E. Quesada: 2669 Elm Circle, El Centro, CA 92243 (760) 562-3069 EmailDocument3 pagesChristine E. Quesada: 2669 Elm Circle, El Centro, CA 92243 (760) 562-3069 EmailChristine QuesadaNo ratings yet

- Jessica Beck ResumeDocument1 pageJessica Beck Resumeapi-252663245No ratings yet

- Extending The Trombone RangeDocument6 pagesExtending The Trombone Rangeapi-238000790No ratings yet

- Debate School UniformsDocument2 pagesDebate School UniformsSiti aisyah devianaNo ratings yet

- Certificate (1) Research Report (2) ..... NWDocument2 pagesCertificate (1) Research Report (2) ..... NWBrijesh KumarNo ratings yet