Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Li - From The Ethnic To The Public

Li - From The Ethnic To The Public

Uploaded by

C. ZhuCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Transport Phenomena in Biological Systems 2nd Edition George A. Truskey, Fan Yuan, David F. Katz Solutions ManualDocument5 pagesTransport Phenomena in Biological Systems 2nd Edition George A. Truskey, Fan Yuan, David F. Katz Solutions Manualmer25% (4)

- Republican Ballot Security Programs: Vote Protection or Minority Vote Suppression-Or Both?Document113 pagesRepublican Ballot Security Programs: Vote Protection or Minority Vote Suppression-Or Both?Rob AvilaNo ratings yet

- Hrana I Identitet U JapanuDocument22 pagesHrana I Identitet U JapanuetnotropNo ratings yet

- An Exploration of Chineseness in Mindanao, Philippines: The Case of Zamboanga CityDocument22 pagesAn Exploration of Chineseness in Mindanao, Philippines: The Case of Zamboanga CityMike TeeNo ratings yet

- Alkindipublisher1982,+paper+6+ (2020 2 1) +Christianization+and+its+Impact+on+Mizo+CultureDocument7 pagesAlkindipublisher1982,+paper+6+ (2020 2 1) +Christianization+and+its+Impact+on+Mizo+CultureZaiaNo ratings yet

- Yen Ching HwangDocument30 pagesYen Ching HwangShazwan Mokhtar100% (1)

- Mila.. Exploring Music Education Instructional....Document22 pagesMila.. Exploring Music Education Instructional....hezron wanakaiNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyDocument42 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press Society For EthnomusicologyJuliana Wendpap BatistaNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Spectacle and Ethnic Relationship in Arts FestivalsDocument10 pagesMulticultural Spectacle and Ethnic Relationship in Arts FestivalsGabriel LopezNo ratings yet

- Connecting Places, Constructing Tet. Home, City and The Making of The Lunar New Year in Urban VietnamDocument22 pagesConnecting Places, Constructing Tet. Home, City and The Making of The Lunar New Year in Urban VietnamTran KahnNo ratings yet

- Yang, Fengang and Helen Rose Ebaugh, Transformations in New Immigrant Religous and Their Global ImplicationsDocument21 pagesYang, Fengang and Helen Rose Ebaugh, Transformations in New Immigrant Religous and Their Global ImplicationsHyunwoo KooNo ratings yet

- Chinese Indonesian: Possibilities For Civil Society: Dr. Clare Benedicks FischerDocument11 pagesChinese Indonesian: Possibilities For Civil Society: Dr. Clare Benedicks FischerbudisanNo ratings yet

- A Victorian Missionary and Canadian Indian Policy: Cultural Synthesis vs Cultural ReplacementFrom EverandA Victorian Missionary and Canadian Indian Policy: Cultural Synthesis vs Cultural ReplacementNo ratings yet

- Anticolonial Homelands Across The Indian Ocean: The Politics of The Indian Diaspora in Kenya, Ca. 1930-1950Document27 pagesAnticolonial Homelands Across The Indian Ocean: The Politics of The Indian Diaspora in Kenya, Ca. 1930-1950valdigemNo ratings yet

- Migration and MulticulturalismDocument65 pagesMigration and MulticulturalismMary Grace MatucadNo ratings yet

- Religious Revival in the Tibetan Borderlands: The Premi of Southwest ChinaFrom EverandReligious Revival in the Tibetan Borderlands: The Premi of Southwest ChinaNo ratings yet

- The Distribution of Spread of ReligionsDocument2 pagesThe Distribution of Spread of ReligionsChow MilNo ratings yet

- 982 Artikeltext 1952 1 10 20161012Document20 pages982 Artikeltext 1952 1 10 20161012Hanh VoNo ratings yet

- Axiology CultureDocument12 pagesAxiology CulturePujitadwNo ratings yet

- Promises2004AA 106 3Document16 pagesPromises2004AA 106 3andrij.lenivNo ratings yet

- Ashiwa 2015Document22 pagesAshiwa 2015dhammadinnaaNo ratings yet

- PH 103 Time and Space PaperDocument6 pagesPH 103 Time and Space PaperClinton BalbontinNo ratings yet

- PDF Multi FacetDocument11 pagesPDF Multi FacetDraft VidsNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument10 pagesChapter IIKate Cyrille ManzanilloNo ratings yet

- Mcnally 2000Document27 pagesMcnally 2000Osheen SharmaNo ratings yet

- 01 KwanghoDocument18 pages01 KwanghoDoan Khanh MinhNo ratings yet

- Chinese Culture ThesisDocument6 pagesChinese Culture Thesiscandacegarciawashington100% (2)

- Chinese ValuesDocument7 pagesChinese ValuesJenny A. BignayanNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Pride, American Patriotism: Slovaks And Other New ImiigrantsFrom EverandEthnic Pride, American Patriotism: Slovaks And Other New ImiigrantsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Cultural Identity in Intercultural Communication: Social SciencesDocument4 pagesCultural Identity in Intercultural Communication: Social SciencesReshana SimonNo ratings yet

- College of Asia and The Pacific, The Australian National University Australian National UniversityDocument22 pagesCollege of Asia and The Pacific, The Australian National University Australian National UniversityibsenbymNo ratings yet

- 19.2d Spr08dearborn SMLDocument14 pages19.2d Spr08dearborn SMLUmesh AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Yoon Et Al 2011 The Border Crossing of Habitus Media Consumption Motives and Reading Strategies Among Asian ImmigrantDocument17 pagesYoon Et Al 2011 The Border Crossing of Habitus Media Consumption Motives and Reading Strategies Among Asian Immigrant6fhr22rc9yNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 94.189.131.192 On Wed, 10 Nov 2021 15:37:17 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 94.189.131.192 On Wed, 10 Nov 2021 15:37:17 UTCLazarovoNo ratings yet

- American Anthropological Association, Wiley American EthnologistDocument26 pagesAmerican Anthropological Association, Wiley American EthnologistGerman AcostaNo ratings yet

- Reassessing The Chinese Diaspora From The South History Culture and NarrativeDocument9 pagesReassessing The Chinese Diaspora From The South History Culture and Narrativeggg10No ratings yet

- 19IEESASM406 Folk CultureDocument6 pages19IEESASM406 Folk Culturezerlina.liu.2027No ratings yet

- Transnational Religious NetworksDocument12 pagesTransnational Religious NetworksChi TrầnNo ratings yet

- The Peyote Religion: A Study in Indian-White RelationsFrom EverandThe Peyote Religion: A Study in Indian-White RelationsNo ratings yet

- Vietnamese Lunar New Year: Ancestor Worship and Liturgical Inculturation Within A Cultural HolidayDocument4 pagesVietnamese Lunar New Year: Ancestor Worship and Liturgical Inculturation Within A Cultural HolidayLê Đoài HuyNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On The Difference Between Traditional Lighting Festivals Between China and MyanmarDocument5 pagesComparative Study On The Difference Between Traditional Lighting Festivals Between China and MyanmarResearch Publish JournalsNo ratings yet

- Activity No. 1Document3 pagesActivity No. 1Marygwen TarayNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Ancestral HouseDocument4 pagesResearch Proposal Ancestral Houseameriza100% (1)

- What Is China? Name University Tutor DateDocument7 pagesWhat Is China? Name University Tutor DateAnonymous pvVCR5XLpNo ratings yet

- KWANZAA A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture: FACT BOOK SECOND EDITION 2022From EverandKWANZAA A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture: FACT BOOK SECOND EDITION 2022No ratings yet

- Mobility Aspirations and Indigenous Belonging Among Chakma Students in DhakaDocument17 pagesMobility Aspirations and Indigenous Belonging Among Chakma Students in DhakaEnamul Hoque TauheedNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.240.11 On Mon, 08 Nov 2021 09:55:29 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.240.11 On Mon, 08 Nov 2021 09:55:29 UTCOsheen SharmaNo ratings yet

- Identities and Popular CultureDocument4 pagesIdentities and Popular CultureDelia TadiaqueNo ratings yet

- ISEAS Perspective 2016 12Document11 pagesISEAS Perspective 2016 12khNo ratings yet

- Canada's-: Context and IdentityDocument3 pagesCanada's-: Context and IdentityBridget ArmstrongNo ratings yet

- Local History of Jakarta and MulticulturalAttitudeDocument8 pagesLocal History of Jakarta and MulticulturalAttitudeYose RizalNo ratings yet

- Post-Soviet Religio-Cultural Scenario in CeDocument27 pagesPost-Soviet Religio-Cultural Scenario in CeEnecanNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter1Document48 pages10 Chapter1zroro8803No ratings yet

- M.chkhartishvili InformativeValueDocument18 pagesM.chkhartishvili InformativeValueNati TsiklauriNo ratings yet

- Warner, R. Stephen, Religion, Boundaries, and BridgesDocument23 pagesWarner, R. Stephen, Religion, Boundaries, and BridgesHyunwoo KooNo ratings yet

- Torn Between Two Worlds: A Case Study of The Chinese Indonesians and How An Identity Is Moulded Externally and InternallyDocument28 pagesTorn Between Two Worlds: A Case Study of The Chinese Indonesians and How An Identity Is Moulded Externally and InternallyhaeresiticNo ratings yet

- Ritual in UzbakistanDocument24 pagesRitual in UzbakistanElham RafighiNo ratings yet

- Lunar New Year - A Tale of Two CulturesDocument4 pagesLunar New Year - A Tale of Two CulturesTu Linh NGUYENNo ratings yet

- Chinatown, Los Angeles CA: Elyse Casillas SBS 318-13 EthnographyDocument7 pagesChinatown, Los Angeles CA: Elyse Casillas SBS 318-13 Ethnographyapi-339777989No ratings yet

- DITO Samar Province Locations UpdateDocument82 pagesDITO Samar Province Locations UpdateJebong A. MarquezNo ratings yet

- The British Royal Family Worksheet 1Document4 pagesThe British Royal Family Worksheet 1Гульвира ДжанусоваNo ratings yet

- TNCT - Q4 - Module2a - Assessing Political and Social Institutions EditedDocument12 pagesTNCT - Q4 - Module2a - Assessing Political and Social Institutions EditedJohn Lorenze Valenzuela100% (1)

- Fall 2022-23 P4 Listening and Note-Taking Practice - StudentDocument11 pagesFall 2022-23 P4 Listening and Note-Taking Practice - StudentCeylin Damla OzdilNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic World (Part 2) - European Nations Settle North AmericaDocument25 pagesThe Atlantic World (Part 2) - European Nations Settle North AmericaAngela Goma TrubceacNo ratings yet

- MUN On Israel-Palestine Conflict Resource PreparationDocument3 pagesMUN On Israel-Palestine Conflict Resource PreparationNurisHisyamNo ratings yet

- Result JR - Engineer S and T NE03Document2 pagesResult JR - Engineer S and T NE03HarshNo ratings yet

- Investigative Statement No 1-RedactedDocument9 pagesInvestigative Statement No 1-RedactedNewsTeam20No ratings yet

- Philippine HistoryDocument30 pagesPhilippine HistoryMeralie CapangpanganNo ratings yet

- BSMMU Neurosurgery March 2023Document1 pageBSMMU Neurosurgery March 2023Delta HospitalNo ratings yet

- 1PEC ChurchillDocument6 pages1PEC ChurchillBlanca LebowskiNo ratings yet

- Shelby County Democratic Party By-Laws 2017Document19 pagesShelby County Democratic Party By-Laws 2017Michael HarrisNo ratings yet

- Parliament Part 1Document5 pagesParliament Part 1atipriya choudharyNo ratings yet

- The Policy Cycle Notion The Policy CycleDocument21 pagesThe Policy Cycle Notion The Policy CycleOliver AbordoNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of Diplomatic Method, Harold NicolsonDocument49 pagesThe Evolution of Diplomatic Method, Harold NicolsonRebekah KaufmanNo ratings yet

- Feudalism in IndiaDocument3 pagesFeudalism in IndiaVinit KumarNo ratings yet

- Year 9 History Week 2-3Document5 pagesYear 9 History Week 2-3ubani.giftNo ratings yet

- CRC Mep SD Ele LC GF HL 201 Sheet 01Document1 pageCRC Mep SD Ele LC GF HL 201 Sheet 01Hamid KhanNo ratings yet

- FA2.3 Group4Document5 pagesFA2.3 Group4AbbygailNo ratings yet

- Immergut 2006 Institutional Constraints On PolicyDocument9 pagesImmergut 2006 Institutional Constraints On Policyana.nevesNo ratings yet

- CWEVPO1st Allotment WH ReleaseDocument3 pagesCWEVPO1st Allotment WH ReleasevigneshnrynnNo ratings yet

- Rituals Performed British Period Modern Period in Literature Notable People See Also References External LinksDocument3 pagesRituals Performed British Period Modern Period in Literature Notable People See Also References External LinksAnusha NagavarapuNo ratings yet

- 500 Polity QuestionsDocument18 pages500 Polity QuestionsSubh sNo ratings yet

- Iraq: A Liberal War After All: A Critique of Dan Deudney and John IkenberryDocument15 pagesIraq: A Liberal War After All: A Critique of Dan Deudney and John IkenberryMaya AslamNo ratings yet

- Module 1.9 Global DividesDocument5 pagesModule 1.9 Global DividesAilene Nace GapoyNo ratings yet

- Spreading The Big Lie Social Media Sites Report NYUDocument24 pagesSpreading The Big Lie Social Media Sites Report NYUDaily KosNo ratings yet

- Article Xvii Amendments or RevisionsDocument2 pagesArticle Xvii Amendments or RevisionsAli AdemNo ratings yet

- Malala Yousafzai: A Young Girl Who Is Making Pakistan ProudDocument13 pagesMalala Yousafzai: A Young Girl Who Is Making Pakistan ProudAhmed Hassaan LatkiNo ratings yet

Li - From The Ethnic To The Public

Li - From The Ethnic To The Public

Uploaded by

C. ZhuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Li - From The Ethnic To The Public

Li - From The Ethnic To The Public

Uploaded by

C. ZhuCopyright:

Available Formats

From the Ethnic to the PublicAuthor(s): Mu Li

Source: Western Folklore , Vol. 77, No. 3/4 (Summer/Fall 2018), pp. 277-312

Published by: Western States Folklore Society

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26864127

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26864127?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Western States Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Western Folklore

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

From the Ethnic to the Public

The Emergence of Chinese New Year

Celebrations in Newfoundland as

Vernacular Cultural Heritage

Mu Li

ABSTRACT

Chinese New Year was brought with Chinese immigrants to

Newfoundland upon their first arrival in 1895. During the

Chinese restriction era, the celebrations were only observed

in private ethnic space. As multiculturalism has been more

recognized, celebrating Chinese New Year gradually has

become a public cultural event, practiced within and beyond

the diasporic outskirts. This paper attempts to describe and

interpret the process of how a diasporic culture emerges as a

shared local tradition and creates a new sense of belonging in

response to official multiculturalism. KEYWORDS: Chinese

diaspora, festival studies, ethnic folklore, Chinese New Year,

multiculturalism

Mu Li is Associate Professor in the School of Arts at

Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Western Folklore 77.3/4 (Summer/Fall 2018): 277-312. Copyright © 2018. Western States Folklore Society

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

278 MU LI

INTRODUCTION: THE ETHNIC AS THE VERNACULAR

December 31, 2006 was a special day for the residents of the Ca-

nadian Labrador West, because on this day Chinese New Year

was the theme of their annual First Night Celebration (Bennett

2006:5). Likewise, January 23, 2012 was another special event

in Labrador West: students and staff at St. Teresa’s School in

St. John’s, the capital of Newfoundland and Labrador province,

celebrated the Chinese New Year, which was acknowledged as

a holiday by the school (Maloney 2012:B4). These two events

show how the heritage of an ethnic group can be acknowledged

and accepted as a part of the host society, through the integra-

tion of an ethnic holiday into the local festive calendar.

However, despite its current recognition, Chinese New Year

celebrations were not always welcomed by the general public

in Newfoundland, most of whom are of British or Irish descent.

Chinese New Year celebrations began with the first arrival of

Chinese immigrants in Newfoundland in 1895. During the Chi-

nese restriction era (1906-1949), Chinese New Year celebra-

tions were only observed in private or ethnically-marked spaces

(Hong 1987; Sparrow 2006; K. Li 2010). With the rise of multi-

culturalism in Canada, celebrating Chinese New Year gradually

became a public cultural event, practiced now both within and

beyond the diasporic Chinese community. This article attempts

to reflexively describe and interpret the process of how this eth-

nic culture went beyond the border of its initial community and

emerged as a shared local tradition within the historic-social

context of emerging Canadian multicultural policy. Built on

ideas such as “vernacular multiculturalism” (Armstrong-Fume-

ro 2009), “everyday multiculturalism” (Moss 2011) and “local-

ized multiculturalism” (Okubo 2013), this article also provides

an understanding of the interplay between the official ideologi-

cal discourses and individual everyday cultural representations.

From 2008 to 2016, I did field research in the Chinese dia-

sporic community in Newfoundland, a relatively small popu-

lation of less than 2,000 members. Within that small group,

however, is considerable diversity in terms of their family’s

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 279

migration history, place of origins, language, and many other

socio-cultural factors. The history of Chinese immigration to

Newfoundland can be roughly categorized into three waves.

The first wave of Chinese immigrants were those who came

to Newfoundland as unskilled laborers before Newfoundland’s

confederation to Canada in 1949. The second wave consists

mainly of the immediate families of first wave immigrants,

who came under the Canadian family reunion program before

the new immigration act came into effect in 1967. The first and

second waves of Chinese immigrants mostly came from the

coastal part of southern China, especially Guangdong province

and Hong Kong. They celebrated Chinese New Year mostly

with members of their tongs, private groups whose members

were related to each other by kinship or shared regional iden-

tity, and which were overseen by prominent community leaders.

Although many of these older generation Chinese individuals

chose not to continue their festive celebration when their work-

ing schedules conflicted with festival time, their choice not to

celebrate was still framed as a strong attachment to their sense

of Chineseness as represented by their work ethic. This fram-

ing is expressed in Chinese culture through proverbs such as “A

young idler, an old beggar.”

Since 1967, when Canada adopted a socioeconomically

determined point system to replace its former race-based stan-

dards for the admission of immigrants, newly eligible Chinese

professionals from all over the world began to arrive in New-

foundland, representing a third wave of Chinese immigrants.

Around the same time, multiculturalism became the officially

stated cultural policy of Canada. With new approval from the

government and the larger community, these newly-arriving

Chinese professionals, along with some locally born or raised

Chinese individuals, started to promote Chinese New Year cel-

ebrations in the public sphere. This new generation, recognized

as cultural in-betweeners (Pryce 1979), cultural wanderers (M.

Li 2014b) or “new ethnicity” (Nahachewsky 2002), uses Chi-

nese New Year celebrations to claim a different understanding

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

280 MU LI

of Chineseness, a creolized version of ethnicity that combines

the loyalty to the ancestral culture and the adaption of vernacu-

lar understanding (Stern and Cicala 1991; Kapchan and Strong

1999; Baron and Cara 2003; Zhang 2015).

The Chinese New Year celebrations in Newfoundland pro-

vide a model for what I argue is a three stage process of devel-

opment for ethnic festivals, which is closely associated with

and shaped by larger ideological messages, such as anti-Chi-

nese sentiment and multiculturalism. The first stage is festival

for themselves because the event is exclusively designed for

members of the ethnic group, which in many cases is social-

ly and culturally isolated from the mainstream community or

other dominant groups. Early Chinese New Year celebrations

in Newfoundland provide an example of this stage. In the sec-

ond stage, the previous discriminatory hierarchy is challenged

or discarded and a new open system is established. The offi-

cial policy of multiculturalism in 1971 has largely changed the

public perception of Chinese-Canadians from a second-class

ethnic group into proud citizens with a rich cultural heritage

(P. Li 1998). Access to funding and other resources as well as

the foundation of a formalized ethnic organization moved the

Chinese New Year celebration into the second stage, a festival

for the community (Johnson 2005:225). In this stage, the fes-

tive performances of the ethnic community are consciously or

unconsciously oriented towards a mainstream gaze. Only some

aspects of ethnic heritage are maintained and reinforced (Gar-

lough 2011). These ethnic survivals are important in the transi-

tion from the second stage to the final one, which I call multi-

presented shared heritage.

In the third stage, the festival “presents ethnic differenc-

es as acceptable and indeed laudable variations on common

themes” and “all the participants are regarded as equal in

worth because all are seen as living—eating, dancing, dressing,

socializing, working, loving, and even squabbling—in essen-

tially comparable and acceptable ways” (Errington 1987:657).

In this case, the hierarchy between the ethnic group and the

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 281

host society shifts and the dominant group begins to embrace

the ethnic culture by hosting ethnic events. As Shutika notes,

“Festivals and other common experiences…enable participants

to engage one another. Such experiences connect people to the

place in significant ways” (Shutika 2011:230-231). In other

words, the “foreign” and “exotic” gradually merge to “ver-

nacular” and “familiar” and a new local culture might emerge

from this interactive folkloric practice and experience (Zhang

2015).Therefore, as we see in the case of Chinese New Year

celebrations in Newfoundland, multiculturalism, which is

more than a bureaucratic ideology but something relevant to

distinct communities and individuals, does not result cultural

separation and failed acculturation as some opposing voices

have suggested. Rather, practices based in multiculturalist

thinking successfully promote effective social integration.

E A R LY C H I N E S E N E W Y E A R C E L E B R AT I O N S

IN NEWFOUNDLAND

The celebrations of Chinese New Year in Newfoundland, which

was not a part of Canada until 1949, started immediately af-

ter the first arrival of Chinese immigrants in 1895. These early

Chinese immigrants were mainly laundry workers or laborers,

attempting to make a living in the British Dominion (M. Li

2014b). A local newspaper Daily News reported the first New

Year celebration in St. John’s as follows: “The Celestials of

New Gower Street1 celebrated a special event on Wednesday.

Their novel manner of celebration—which was a noisy one—

attracted a large crowd around their places of business. The

laundry was illuminated and a display of firework was given”

(Daily News 1896). This short description reveals four impor-

tant aspects of this early Chinese New Year celebration in New-

foundland: first, the celebration was held on Wednesday, Febru-

ary 12th, 1896, which according to the traditional calendar was

the correct date of the new year; second, the celebration was a

group activity; third, the location of the festival—a laundry en-

hanced with special decorations—was both public and private.

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

282 MU LI

In other passages, the report also indicates non-Chinese New-

foundlanders’ first reaction towards the celebration, which was

somewhat negative but also mixed with curiosity. While, on the

one hand, non-Chinese residents saw the celebration as a noisy

display by a mass of foreigners, they also enjoyed the colorful

festivities and fireworks.

Since then, reports with more details related to Chinese

New Year occasionally have appeared in local newspapers.

For instance, a February 28, 1907 article in the Evening Her-

ald observed:

To-day begins the Chinese New Year celebration—begins,

for with the Celestial it takes three days for the old year to

make his last kicks. During that time the joss stick burns,

the Mongolian soul rejoices itself in fatness, and the air

is rent by the unseemly noise of Oriental fire-crackers. In

these days of feasting the laundryman goes about in his

best frock, and his bland smile grows still blander as he

looks in pity upon the unhappy “fellin devil.” Moreover,

his ancestors and the other things that he worships come in

for all sorts of adoration during these days.

Although this report includes does refer to some important ritu-

alistic and customary elements of Chinese New Year, it couch-

es them using derisive, racially-charged terms such as “Mongo-

lian soul,” “unseemly noise,” “frock” and “bland smile.” The

considerable differences in the celebration of Chinese and non-

Chinese New Year in Newfoundland, including differences in

festive decoration and festival dates, served to strengthen the

exoticization of Chineseness in Newfoundland.

The date of Chinese New Year was cause for consider-

able confusion among non-Chinese people. For example, on

September 21, 1906, the Evening Herald reported, “Some 43

Chinamen, led by Kim Lee2, and all in full fig and smoking

cigars left by this morning’s train for an outing at Whitbourne.

They are celebrating the beginning of the Chinese New Year”

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 283

(Evening Herald 1906a).3 On the following day, in another

piece in the Evening Herald, the author “revealed” that the real

reason of the departure of the Chinese, which was thought be

to “a strange proceeding”, was actually “an attempt to smuggle

them into either Canada or the United States” (Evening Her-

ald 1906b).Two days after the appearance of the above story,

an anonymous reader wrote a letter to another local newspa-

per, the Evening Telegram, to challenge the Evening Herald’s

report. The reader claimed that the report was “a huge mistake

if not something stronger” because “Kim Lee was delivering

his customers their work on Saturday night, and went to Sun-

day school at Alexander Street yesterday afternoon” (Evening

Telegram 1906). More importantly, the reader recognized that

“the opening of the Chinese New Year will not be until 15th

January, 1907” (Evening Telegram 1906).

The misunderstanding or editorial mistake made by the

Evening Herald might be attributed simply to the fact that the

majority population were not familiar with Chinese New Year;

however, the implication of the second article was that Chinese

people might have been using their heritage as an excuse for

illegal activities, especially as resistance during the Chinese

exclusion era (1906-1949). Around this same time in 1906,

following the United States and Canada, the Newfoundland

government passed the discriminatory Act Respecting the Im-

migration of Chinese Persons to restrict Chinese immigration

by imposing a $300 head tax on each Chinese who intended to

enter the island, with the exception of those in certain social

categories such as diplomats and clergymen (Hong 1987; K. Li

2010). The passage of this act exacerbated the existing racial

and cultural separation between Chinese and other Newfound-

landers and hindered their inter-group communication.

Despite their confusion about the festival date and other

relevant details, the reports do reveal that early Chinese New

Year celebrations were often celebrated under the leadership

of community leaders such as Au Kim Lee. In the pre-con-

federation period in Newfoundland, the Chinese community

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 MU LI

consisted exclusively of males who were all Cantonese,4 relat-

ing to each other either by kinship or shared regional identity.

In this type of bachelor community, which was widely found

in early Chinese settlements in North America, men relied on

each other for mutual assistance and social support (Marshall

2011). Community leaders not only played important roles in

everyday commercial and social life, but also in the mainte-

nance of ethnic traditions, cultural practices which bound co-

ethnics together and created a sense of Chinese community in

the face of a hostile socio-cultural environment.

In the decades before Confederation, under the leadership

of some more educated Chinese residents (e.g. Au Kim Lee and

William Ping) and with the formation of clan associations such

as the Tai Mei Club and the Hong Hang Society,5 Chinese cul-

tural gatherings like New Year celebrations were held in private

business buildings or in rented/purchased community centers.6

These ethnic celebrations, at least for the first few decades of

Chinese presence in Newfoundland, were restricted to the pri-

vate/ethnic level.

The economic pressure in Newfoundland also drove early

Chinese settlers away from celebrating the New Year in the

same way it had been done in China. In order to make more

income to support their families back home, Chinese laundry

workers worked long hours, with little time for leisure. When

William Ping was working at the Sing Lee Laundry in the 1930s,

he barely had enough time to sleep during workdays: “You got

to wash, to starch, to dry, to damp, to iron and to wrap the laun-

dry. Sometimes I had supper at four o’clock in the next morn-

ing. I wash my laundry with tears” (Quoted in Hoe 2003:35).

In the late 1950s, many Chinese laundries were closed and

a majority of these Chinese who retired from the laundry busi-

ness began to set up restaurants. In comparison with their laun-

dry work, the new economic lives of Chinese were even more

occupied by the work. Their restaurants were open seven days

a week, leaving very little available time to celebrate festivals

like Chinese New Year. George Au, who at the age of 84 is still

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 285

working at his Sun Luck Restaurant in Stephenville in western

Newfoundland, says: “When I was working at Newfoundland

Laundry in St. John’s in late 1940s and early 1950s, I saw all

people got one day off per week. But when I started my own

restaurant, I never got a day off. The motto to us is that you

never close your restaurant.”7

In 1947, Canada repealed its Chinese Exclusion Act under

the human rights guideline of the United Nations and enacted

the Canadian Citizenship Act, granting all residents in Canada

equal rights in citizenship applications. When Newfoundland

confederated to Canada in 1949, its Chinese Immigration Act

was subsequently abolished so that many Chinese residents

became naturalized. Thanks to the Canadian post-war fam-

ily reunion program, Chinese settlers’ long-separated families

began to come to Newfoundland to join them, contributing to

the rapid increase of the local Chinese population. Many Chi-

nese families remained involved in mom-and-pop restaurant

businesses and could not afford to spare time for celebrations

of Chinese New Year. Therefore, although the local Chinese

population increased to a historical peak in the early 1970s,

the festival remained marginalized, even within the Chinese

community. As, Wallace Hong, a former restaurant owner in

St. John’s who came to Newfoundland in 1949, notes, “We

had only two days off annually which one was Christmas Day

and the other was New Year’s Day. We never closed for the

Chinese New Year.”8

The early history of Chinese New Year celebrations in

Newfoundland shows a shift in the attitude of these mainly

Cantonese migrants towards the festive tradition: at first they

continued to practice the tradition in private for a considerable

time, but gradually downplayed it as their workload increased.

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE PUBLIC

In the early decades of the Chinese ethnic community in New-

foundland, a strong anti-Chinese cultural bias shaped the politi-

cal and economic woes endured by Chinese immigrants, but it

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

286 MU LI

also bolstered the view that Chinese traditions were pagan and

uncivilized. As in many places, even in San Francisco where

a much bigger Chinese community existed, non-Chinese indi-

viduals were often hesitant to approach Chinese cultural events,

which were mainly observed privately by small groups of Chi-

nese at ethnic establishments (Yeh 2008).

Krista Li points out that the geographic distance from

China, the political separation from Canada and the United

States due to the Chinese exclusion laws, and the small popu-

lation made the Chinese in Newfoundland more isolated than

their counterparts in larger metropolitan centers. As a result,

Chinese traditions were “often neglected” by them (K. Li

2010:231). The limited access to social and cultural resources

to maintain traditional festivals accentuated the lack of con-

nection to their ancestral country because, “these old world

rituals served as a link between immigrants and their home

countries” (Yeh 2008:15).

At the same time, spatial restrictions around Chinese cul-

tural events, such as the celebrations of Chinese New Year, in-

hibited Chinese residents’ sense of belonging in the host com-

munity, since ethnic festivals celebrated in public can provide

an occasion for newcomers to “begin the process of incorpo-

ration and shape the sense of place” in their new settlements

(Shutika 2011:205). The celebration of Chinese New Year in

private places such as Chinese-owned restaurants and laun-

dries turned everyday work spaces into an exclusive Chinese

celebratory space which was “reclaimed, cleared, delimit-

ed, blessed, adorned, forbidden to normal activities” (Falassi

1987:4). However, this festival space could be invaded by un-

suspecting individuals from the host community and festivities

interrupted by inter-ethnic business interactions. Customers

who entered the celebratory space and festive time were imme-

diately transformed into unexpected festival visitors and expe-

rienced an alteration to what Falassi describes as “the usual and

daily function and meaning of time and space” (4). These kinds

of cultural interactions between Chinese and non-Chinese

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 287

residents may have contributed to improvements in inter-group

understanding and to the acceptance of Chinese culture.

As the most important part of Chinese festival culture, Yeh

(2008) suggests that Chinese New Year, which is often linked

to the wider political, sociological, and economic contexts,

serves as a convenient window for outsiders to look into the

Chinese community. Before the 1960s, Canada favored an as-

similationist approach to immigration, but after the change of

the immigration law in 1967, more immigrants from non-Eu-

ropean countries joined an increasingly multicultural Cana-

dian society. At the same time, with resurgent Quebec nation-

alism in the 1960s, the Royal Commission on Biculturalism

and Bilingualism was established in 1963 to study the binary

Francophone/Anglophone tension in Canadian society. In

1969, commissioners concluded instead that there were more

than two cultures in Canada and therefore suggested an inte-

gration mode in replacement of the former assimilation ideol-

ogy. The recommendation led to the introduction of Canadian

multiculturalism, which was first officially announced by the

then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in his speech at the House

of Commons on October 8, 1971. In the following years, mul-

ticulturalist ideology has been enshrined in the Constitution

in the 1984 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and

has become a legal framework with the passage of The Multi-

culturalism Act in 1988. Over the years, multiculturalism and

diversity have been described as fundamental characteristics

of Canada and as core to Canadian life. Today, multicultural-

ism in Canada is perceived descriptively as a sociological fact,

prescriptively as ideology, and politically as policy (Dewing

2013:1).

As a policy, since its inception in 1970s, the Canadian

government promised to 1) “assist all Canadian cultural

groups that have demonstrated a desire and effort to continue

to develop a capacity to grow and contribute to Canada”; 2)

“assist members of all cultural groups to overcome cultural

barriers to full participation in Canadian society”; 3)”promote

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 MU LI

creative encounters and interchange among all Canadian cul-

tural groups in the interest of national unity”; and 4) “assist

immigrants to acquire at least one of Canada’s official lan-

guages in order to become full participants in Canadian soci-

ety” (Trudeau 1971:8546).

Under the national guideline, the Chinese in Newfound-

land have been encouraged by local multicultural policies

not only to preserve their culture on a private or ethnic level,

but also to showcase their traditions and educate the general

public. The Secretary of State for Canada (head of what is

now the Department of Canadian Heritage) and the Gower

Street United Church congregation in St. John’s were among

the advocates who were willing to provide some financial

support or other kinds of assistance.9 As part of an outreach

program, a United Church committee, which included main-

ly non-Chinese members such as Marion Pitt, the author of

“Chinese Community” in Encyclopedia of Newfoundland

and Labrador, was formed to organize social activities for

all Chinese in St. John’s. Under the leadership of this com-

mittee, various functions including Chinese New Year cel-

ebrations were organized to provide more opportunities for

Chinese and non-Chinese residents of the city to interact

with each other.

A voluntary organization, the Chinese Association of

Newfoundland and Labrador (CANL), was founded by some

Chinese professionals such as Kim Hong who came to New-

foundland to join his grandfather in 1950 at the age of 13 and

eventually became a medical doctor. These professionals were

often employed at non-Chinese owned institutions, and had ex-

panded social circles, which included non-Chinese friends and

acquaintances. Because of this, CANL members were often

able to secure financial support and recognition from the out-

side of the Chinese community. It was in this context that the

first public celebration of Chinese New Year in Newfoundland

became a reality in 1977.

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 289

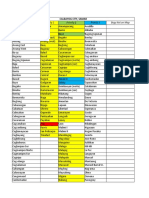

Figure 1

On February 8, 1977, the newly-founded CANL sent out a

newsletter to invite all members to a series of activities to cel-

ebrate the Chinese New Year. In this newsletter, members and

friends of the association were notified that New Year’s Day

was February 18, 1977. The program included a cultural ex-

hibition, a slide show, movies, and speakers, which took place

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 MU LI

on February 17-18 in the Engineering Building of nearby Me-

morial University of Newfoundland. There was also a cultural

exhibition on February 19 at the local Avalon Mall Shopping

Center, and a variety show and Chinese buffet supper on the

February 20 at the Auditorium Annex Building of the College

of Fisheries. On the same day, they held a New Year’s dance

with Orchestra Ed Goff at the E.B. Foran Room of the City Hall.

The activities held on February 20 were the main events of

the festival. The first event was the variety show, which consist-

ed of some traditional Chinese performances such as the moon-

light flower dance, a kung fu demonstration, traditional songs,

and a fan dance. It also included some presentations of non-

Chinese culture, such as a violin solo and Thai classical dance.

The performers were not all Chinese, but rather were from di-

verse ethnicities. The Chinese performers also represented a

broad spectrum of ages, countries of birth, and immigration

statuses. After the variety show, there were greetings from the

chief guest, the Honourable Tom Hickey, Minister of Tourism

of Newfoundland and Labrador. In addition to him, other non-

Chinese guests who attended free of charge also included:

Rev. George LeDrew and wife of the Gower Street United

Church, Rev. Levi Mehaney and wife, Rupert Greene, John

Murphy and Willer Ayre from St. John’s City Council, John

Pike and Paul McDonald of the Provincial Immigration

Department, Dr. F.N. Firme and wife of the Filipino Asso-

ciation, Dr. C.M. Pujara and wife of the Indian Association,

Gary Gray of Y.M.C.A., Don Knight, Robert Butler and Dr.

Barrett of the College of Fisheries, Ken Duggan and “Neil

or Mike O’Brian” of the Trades College, Food inspectors

D.A. Strong and D. Martin, Mr. and Mrs. John Browne of

the Police Department and the Fire Chief Cecil Sooley.10

The variety show started with the national anthem O Canada,

and ended with Ode to Newfoundland, the official provincial

anthem sung by all attendees. A buffet-style supper started at

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 291

around 4:00 or 4:30 consisting of food that was mainly donated

by local Chinese restaurants, whose owners and workers were

CANL members. Dishes included “spring rolls, barbecued

pork, chicken fried rice, chicken guy ding, beef and broccoli

and lemon chicken” as well as desserts which were cookies and

cakes, made by female CANL executive members or by spous-

es of male executive members such as Jeannie Aue, Bernice

Gin and Kim Hong’s wife Mely.11 At the end of the evening, a

ball was held, attracting many attendees.

At the 1977 Chinese New Year celebration, two locations

chosen to host the main events were the Auditorium Annex

Building of the College of Fisheries and the E.B. Foran Room

of the City Hall, instead of any Chinese restaurants or the Tai

Mei Club which still existed in the mid-1990s. Shutika (2011)

observes that the celebration of ethnic festivals at popular sites

indicates a recognition and acceptance of ethnic cultural heri-

tage on the part of the majority population. Chinese residents

were gradually being absorbed into Newfoundland society and

now able to lease space for their cultural activities. In the later

years, owners of popular venues such as the Colony Club or the

Royal Canadian Legion allowed Chinese to alter their space for

Figure 2

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 MU LI

the New Year festivities. In this way, a secular and public loca-

tion was temporarily transformed into a sacred and traditional

space through the use of symbolic decorations such as decora-

tive lanterns, paper cuttings, the banner of the CANL, and signs

displaying traditional Chinese couplets with special New Year’s

greetings, created a decidedly Chinese festive atmosphere.

Nevertheless, any ethnic transformation was temporary be-

cause an ethnic festival is only “a single socio-cultural space

for a limited period of time” (Turner 1982:21). The relocation

of Chinese New Year celebrations from Chinese-owned estab-

lishments to rental public spaces actually turned the festival

into a placeless event that had little or no specific cultural at-

tachment to a particular place (MacLeod 2006). Even if the se-

miotic signs helped vouch for the authenticity of Chineseness

during New Year’s celebrations, throughout the event guests

and attendees would have been reminded constantly of who

really owned the space by the presence of western furniture set-

ting (e.g. long tables), cutlery (no chopsticks), kitchen cookers,

and a bar. In addition, all wait staff were non-Chinese. Edward

Relph (1976) has referred to this kind of cultural configura-

tion as placelessness, spaces where people have less distinctive

sense of place and little emotional attachment.

In this sense, at the same time a “mainstream” place is

transformed into an ethnic space creating a new sense of be-

longing and memory in the new location (Shutika 2011), the

reverse process is also in play: the ethnic is absorbed into the

non-ethnic. Margaret Chan’s findings concerning traditional

Chinese festivals in Toronto apply here. Chan explores how

non-ethnic public venues like The Royal Ontario Museum

transform ethnic performers into “a live prop and an object

of display … fitting in with whatever mandate and image the

venue presents” for more general and public purposes (Chan

2001:242). When an ethnic festival is advertised to attract the

general public in a wider society, it shares some characteristics

with “event tourism” or “festival tourism” (Getz 2008). Festi-

vals or events become “the venues for tourism experiences, the

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 293

context for social-psychological interaction, and the phenom-

ena by which this behaviour can be described, explained and

predicted” (Snepenger et al. 2007:310). As a touristic event,

CANL’s Chinese New Year celebrations are creolized by the

organizers to combine the Chinese individuals’ perspectives

on Chineseness with the multicultural expectations of non-

Chinese attendees. Therefore, during Chinese New Year cele-

brations, rental celebratory places actually become multi-local

spaces (Rodman 1992) which are concurrently claimed by dif-

ferent groups as their cultural and social terrains.

THE HYBRIDITY AS ROUTINE

The 1977 Chinese New Year celebrations were organized by

the executive members of the CANL and some active Chinese

families such as those of Chan Chau Tam and Daniel Wong. Of

these organizers, Jeannie Tom and Rita Au were locally born;

Margaret Chang was a British Newfoundlander who married a

Chinese man; Kim Hong, Sing Lang Au and Ted Hong came

to Newfoundland as teenagers and attended the local school

Bishop Field College; Brian Winn was from a Chinese commu-

nity in formerly British-ruled Burma; and Chan Chau Tam and

Daniel Wong came from British-ruled Hong Kong. They were

all attached to Chinese culture in some way, although some like

Chan Chau Tam and Daniel Wong had more experience with it

than the others. However, they were all also educated either in

local Newfoundland culture or western (British) culture in gen-

eral. Some of them, like Jeannie Tom and Rita Au, also often

claimed to have a different understanding of what it meant to

be Chinese than the older generations. The 1977 celebrations

produced by this team presented these new definitions of Chi-

neseness in the context of Newfoundland where both Chinese

and Western cultures were located simultaneously.

In the following years, many of the individuals, such as

Melvin Hong (who was born to an intermarried family), Ar-

thur Leung (from Hong Kong), Dean Hong (Kim Hong’s son),

Mary Gin (locally born), Tzu-Hao Hsu (from Taiwan at the age

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 MU LI

of 11) and Shirley Hong (who is a white Newfoundlander who

married to a Chinese man), who served as CANL executive

members also had the similar backgrounds to the 1977 execu-

tive board. Thus, the format established in 1977 was adopted in

later years as well. However, over the years some aspects of the

format have been altered to adapt to new social changes, and the

format itself has often been the subject of a debate over whether

it is an authentic and effective way to present Chineseness.

T H E D AT E OF THE NEW YEAR

According to the traditional Chinese calendar, the date of New

Year’s Day varies every year, falling between January 22 and

February 20 in the western Gregorian calendar. However, the

public celebration of Chinese New Year rarely takes place on

the exact date, but more often is observed on a weekend during

or sometimes after the traditional holiday season.12 This modi-

fication is often attributed to the fact that Chinese New Year is

neither a national nor a provincial statutory holiday.

Based on Emile Durkheim’s (1915 [1912]:47) classification

of the sacred and the profane, festival time is often perceived as

a different temporal dimension from the ordinary time. Terms

like “time out of time” are widely used to refer to this liminal

temporal zone (van Gennep 1960; Turner 1982; Falassi 1987).

In the festival period, “daily time is modified by a gradual or

sudden interruption that introduces ‘time out of time,’ a spe-

cial temporal dimension devoted to special activities” (Falassi

1987:4). Just as many other festivals create a sense of time that

is different from everyday routine, Chinese New Year reflects

“Chinese definitions of time and the world upon which such so-

cial phenomena are based” (Chan 2001:62). The modification

of a pre-set sacred time to fit into a secular or leisure slot of the

mainstream society is seen by some more traditional Chinese

as the compromise that festival organizers often make.

Notwithstanding their goal of compromise, festival orga-

nizers also attempt to keep the celebrations within the tradi-

tional Chinese definition of time. Kim Hong recalls:

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 295

We were discussing if we needed to celebrate the New Year

on this weekend, which was before the real date or next

weekend, which was after, then a member of the associ-

ation Paul Ho came in and said, “You fellows are crazy.

How can you celebrate the New Year in the old year?” His

words ended the debate and after that, we always had our

celebrations after instead of before.13

The shifting “from the actual holiday to a more convenient date”

(Thomson 1993:401) is a successful strategy to satisfy the re-

quirements of tradition and also accommodate attendees who

can only dedicate their time to celebration on the weekends.

In the first few years, the major events of the festival in-

cluding a variety show, dinner and dance were all scheduled

on Sundays. This schedule reflected the fact that a major-

ity of Chinese residents in Newfoundland were involved in

the restaurant business, and restaurants were normally closed

on Sunday or at least did not open until 5 p.m.14 In 1983,

the new CANL president Daniel Wong rescheduled the main

New Year’s celebration from Sunday afternoon to Saturday

night and extended the dance to 1 a.m. He explained that the

change was due to the increasing number of Chinese profes-

sionals and non-Chinese guests who could not stay late at

Sunday events because of work on Monday.15 However, an

unexpected result of the new schedule was a decline in the

participation of Chinese members who worked in the restau-

rant industry. Those Chinese, who constituted the majority

of the Chinese community in early 1980s, now had to decide

whether or not to close their businesses to attend the New

Year’s party. Many of them chose to stay away from the cele-

brations in favor of working. At the time, some CANL senior

members received complaints regarding the new schedule

from owners and workers at Chinese restaurants: “Saturday

night…is usually a busy night for our restaurant people. We

don’t want to close business to attend the function. Why

doesn’t the association think about us?”16

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 MU LI

The dilemma presented by scheduling Chinese New Year

on Saturday created an internal tension within the community

between preserving tradition and pursuing business. Yet, in of-

ten choosing to keep their businesses open, restaurant workers

did not necessarily see themselves as rejecting tradition. They

saw themselves, as Daniel Wong put it, as celebrating an alter-

native Chinese tradition of “working hard and earning more

money for their children.”17

Therefore, the different attitudes towards the scheduling of

CANL’s Chinese New Year celebrations revealed contradictory

perspectives toward the expression of Chineseness between the

restaurant people, most of whom were first and second wave

Chinese immigrants, and the newer mostly professional genera-

tions. For the former group, cultural preservation had less to do

with the celebration of ethnic holidays than the practice of tra-

ditional principles. For the latter group, celebrating the ethnic

festival with local adaptions was the best way to present their

understanding of ethnicity as both traditional and multicultural.

MAKING UP THE LIST OF INVITED GUESTS

The 1977 Chinese New Year included many non-Chinese

guests such as politicians, members of the clergy, governmental

officials, and leaders of other ethnic groups. These guests were

invited because of their importance to the political, social and

economic well-being of Chinese in that period.18 Since 1977, in-

viting guests from the wider community has itself become a tra-

dition in the Chinese New Year celebrations in Newfoundland.

Besides the special guests, before 1983 most attendees of

Chinese New Year celebrations were Chinese residents in the

St. John’s area.19 Because of the large number of expected Chi-

nese guests in 1978, the CANL secretary Margaret Chang told

the reporter of the Evening Telegram that the event was “closed

to the general public with the exception of a select few” who

would receive special invitations (Carter 1978).

In recent years, Chinese New Year celebrations are still

the biggest Chinese public gatherings in Newfoundland,

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 297

serving as an important social event for Chinese people to

socialize with co-ethnic acquaintances who they might see

only once a year. In this sense, for many Chinese individuals

who are highly acculturated into local society and have little

communication with other Chinese people in their everyday

lives, it is the festival that brings them together and reminds

them of their Chinese identity.

Many Chinese attendees also observe that, while Chinese

New Year celebrations draw in a larger number of Chinese at-

tendees than other gatherings, they are still outnumbered by

non-Chinese guests. The increase in the percentage of non-Chi-

nese at the event was likely a consequence of the 1983 creation

of an adults-only party on Saturday that was separate from the

family celebration on Sunday. After 1983, small children and

some of their parents stopped attending the main celebration

as did some of the restaurant workers. These spots were soon

filled by Chinese professionals and non-Chinese guests, who

are often the friends or acquaintances of active CANL mem-

bers. These two groups gradually became the main participants

in the celebration.

Figure 3

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 MU LI

According to Alick Tsui, a Hong Kong native and optometrist,

the withdrawal of the Chinese population from this important

Chinese festival can be interpreted as the result of the shifting

of the association’s goals for the festival from celebrating with

co-ethnics to introducing ethnic cultural heritage to the larger

community.20

Some people are more in favor of the changes than oth-

ers. An Indonesian-born Chinese otorhinolaryngologist E. T.

Tjan comments: “I look at the Chinese New Year celebration

as an effective way for intercultural communication.”21 A lo-

cally-born certified cook Francis Tam shares the same point

as Tjan: “I would like to have more Caucasians at our par-

ties. That will expand our culture and let people know more

about it.”22 As a Caucasian spouse of a person of Chinese

descent, Violet Ryan-Ping also feels satisfied “because years

ago, we were not well mixed and right now the association

brings us together.”23

In contrast, some Chinese, such as Shinn Jia Hwang, a Tai-

wanese Chinese and retired Ocean-technology researcher, have

reservations about the changes in the Association’s mandate:

“The event didn’t look like a celebration of Chinese New Year,

rather, a common local gathering. It is not supposed to be a

multicultural event but it is our event.”24

As an inseparable part of the new festival format, the Fam-

ily Fun Day on the day after the dinner and dance events seems

to attract more Chinese. This day is intended to allow Chinese

families to show respect to elders, as well as to the family val-

ues which “are the core of Chinese culture and tradition.”25

Nowadays, the population of Chinese seniors and children

is rapidly declining due to the fading-out of the older genera-

tion, emigration, and low birth rates. The size of the Family

Fun Day is shrinking remarkably.26 Currently, a majority of the

attendees of the Family Fun Day are Chinese children adopted

by local non-Chinese families who “want to make sure their

children won’t lose any of their cultural roots.”27 It seems that

the Family Fun Day, which was first organized as a celebratory

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 299

event within the Chinese community, has now gradually trans-

formed into an educational event to reconnect younger people

of Chinese descent with an ancestral culture which is frequent-

ly absent in their daily lives.

Figure 4

I would suggest that the shifting of these events’ goals and the

withdrawal of the Chinese population from them reflects the

way in which the newer CANL organizers hold views different

from older generations of Chinese Canadians, especially those

who immigrated before confederation. Instead of considering

Chinese New Year to be an ethnic festival that highlights their

collective Chineseness in order to secure social recognition and

assistance, newer generations observe it as a personal event. As

a response to multiculturalism on the personal level, festival or-

ganizers prefer not to engage their co-ethnics with whom they

may not be familiar, but instead bring their non-Chinese friends

with whom they can share their understanding of Chinese an-

cestral culture.

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 MU LI

D E T E R M I N I N G E N T E R TA I N M E N T

The entertainment portion of each year’s celebration is of-

ficially titled “a variety show” or “a multicultural show.” As

first highlighted in the program from 1977, this includes not

only the presentation of Chinese traditions but also various

performances from other cultures. For example, in addition to

the Chinese sword dance performed by Christopher and Joyce

Hong, the celebration in 1984 featured Portuguese folk dances

by the Association of Friends of Portugal, modern American

dance by the local Judy Knee Dancers, Binasuan (glass bal-

ancing) by the Filipino Association of Newfoundland and Lab-

rador, and the traditional capers of Newfoundland folk dance

by the Newfoundland Mummers (Evening Telegram 1984). On

top of this, Shirley Newhook, an announcer on CBC Televi-

sion, was the master of ceremonies for the night. Given this

line-up, many people might ask if the event still constitutes a

Chinese celebration. A related question would be: why are per-

formances of other cultural groups brought to the Chinese New

Year celebration?

A direct answer for the popularity of non-Chinese perfor-

mances at annual Chinese New Year celebrations is “the lack

of local talents.”28 Apart from the shortage of human capital,

the presentation of Chinese New Year celebrations as a multi-

cultural variety show can be also attributed to organizers’ aim

to promote multiculturalism instead of solely highlighting Chi-

neseness “because, obviously, we were in the Canadian mul-

ticultural setting.”29 English as the working language used in

Chinese New Year celebrations also reveals its distinct mul-

ticultural trait, although it is awkward for some Chinese who

might expect to hear more Chinese languages.30

On the one hand, Chinese New Year celebrations have

been North Americanized as a multicultural event; but, on

the other hand, festival organizers still attempt to present the

event with Chinese cultural elements. Alick Tsui notes, “We

always try our best to get Chinese to perform at our parties

and we also encourage all performers to sing in Chinese, play

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 301

Chinese musical instruments and perform traditional danc-

es.”31 Since some performers have not been trained specifi-

cally to play Chinese instruments, they are frequently asked

to learn and perform “Chinese” for the events.32

Sometimes, when Chinese performers or performances are

not locally accessible, organizers turn to governmental or non-

profit organizations for financial support to invite performers

from outside of Newfoundland.33 For example, in 1982, spon-

sored by the Department of Secretary of State of Canada, CANL

invited the Montreal Society of Chinese Performing Arts to

present various classical Chinese dances, such as the Feather

Fan Dance, the Butterfly Dance, and other pieces, as a part of

the Chinese New Year celebration.

In recent years, although the overall length of the entertain-

ment section has been shortened to around four performances,

with a marked preference for Chinese rather than non-Chinese

performances. In addition, organizers like Alick Tsui have tried

to introduce Chinese elements to non-Chinese portions of the

celebration, such his introduction of Chinese music to the ball-

room dancing event.34

It seems that after the multiculturalization of the Chinese

New Year celebrations in earlier years, the current trend tends

more toward the restoration of “traditional” Chinese elements.

Earlier, through multicultural presentation, Chinese Canadians

were transformed from the foreign to the ethnic, which Yeh de-

fines as “a cultural group whose mere difference from” white

society was culture, “so that they could assimilate into the dom-

inant society” (Yeh 2008:6). The New Year’s variety shows of-

fer a reassurance that all groups have culture and it places those

cultures on the same footing. Yeh’s interpretation echoes El-

len Litwicki’s (2000) idea of “ethnic Americanism.” Litwicki

challenges the classic sense of assimilation, the confirming of

immigrant groups to dominant cultural norms, as the primary

strategy for immigrant groups to achieve acceptance in society.

She argues that many groups have instead pursued a strategy of

“ethnic Americanism,” of demonstrating to the general public

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

302 MU LI

how their heritage and values “were congruent with American

culture and so need not be discarded” (2000:115).

If we apply Litwicki’s notion of “ethnic Americanism” to

the current public Chinese New Year celebrations in New-

foundland, we can see that the festivities are not attempting

to encourage Chinese residents to stick to Old World tradi-

tions, but rather to help assure the city-at-large that the Chi-

nese and their culture are a contribution rather than a threat

to the broader Newfoundland community. The variety shows

present Chinese culture as part of a local multicultural mo-

saic, which includes a range of ethnic groups who align with

the Chinese on the stage to celebrate the same festival. In

this sense, participation in the Chinese New Year event is an

expression of support for national and provincial policies of

multiculturalism.

Litwicki writes, “If loyalty to one’s homeland made one

a better citizen, then perpetuating the traditions and culture

of the homeland became an imperative of good…citizenship”

of the host country (2000:142). Therefore, the return to more

“traditional” performances in the New Year celebrations is not

intended as a challenge the larger social order, but rather as a

way to present Chinese culture as an analogue to the cultures

of other groups. Kim Hong says, “We organize Chinese New

Year celebrations for the purpose to promote multiculturalism

and to present Chinese ideas to be good neighbors, to be good

citizens … who appreciate Canada.”35 Hong’s words perfectly

present the newer CANL members’ ideas of Chineseness and

their response to multiculturalism, which keenly encourages

the ideal of “unity in diversity” (Howard-Hassmann 1999;

Dewing 2013).

As mentioned previously, the main celebration in 1977

started with the national anthem O Canada and ended with the

provincial anthem Ode to Newfoundland. Kim Hong claims

that the reason they did not sing either Chinese national an-

them was because they wanted to avoid any connection to the

political conflict between mainland China and Taiwan. How-

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 303

ever, he points out that “more importantly, it was a Canadian

multicultural setting.”36 I would argue that the choice reflects

the new creolized Chineseness of the organizers, through

which they seek to express their social and political affiliation

to Newfoundland and Canada. Singing anthems along with

other non-Chinese Canadian citizens is a confirmation that

the Chinese have equal Canadian citizenship.

In the entertainment section of Chinese New Year celebra-

tions, the variety shows and anthem singing can be classified

as a formal or semi-formal part of the whole event, which also

includes an informal dance afterwards. Owe Ronström (1993)

distinguishes two modes of inter-racial interaction in a multicul-

turalism-themed event: representative mosaic and dancing for

everybody. In the first mode, ethnicity is enacted and displayed

through pre-designed ethnic markers for stage performance

including “physical attributes, clothing, instruments, sounds,

melodies, bearing, movements, and symbols” (1993:80). The

majority of these markers such as lion dancing costumes, festi-

val gowns, and traditional Chinese instruments presented in the

variety show section are removed in the second mode. During

the ballroom dancing, “ethnic differences were subdued” and a

common identity for all attendees is temporally constructed to

reach a “cultural truce” (1993:81).

SELECTING FOOD

Food is frequently described as the first attraction of a festi-

val or other social gathering (Humphrey and Humphrey 1991

[1988]:10). Sharing food and drink is an effective way for

people to “acknowledge our commitment and relationship with

each other” (1991 [1988]:xi). As an important aspect of Chi-

nese New Year celebrations, food is elaborately prepared and

presented by CANL and other food providers to cater to po-

tential festival attendees with various taste preferences and di-

etary restrictions. Kim Hong recalls, “We had barbecued pork,

chicken fried rice, sweet and sour pork and some noodles. We

also had Caesar salad.”37 Of these dishes, the salad has a clear

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

304 MU LI

western origin; the others are all North American style Chinese

food instead of other versions of Chinese cuisine (M. Li 2014a).

Compared with the banquets hosted by CANL, festival go-

ers at the 1979 Chinese New Year celebration organized by the

Chinese Student Society enjoyed a more elaborate meal, con-

sisting of “roast duck, spiced chicken Jai doo Guy, B.B.Q pork

served with a traditional bean cake, broccoli and beef, Canton-

ese Chop Suey, Yeung Chow fried rice and Chinese style sweet

and sour pork” (Evening Telegram 1979). These entrees were

not served in buffet-style, but family-style with dishes shared

by diners at the same table. This serving style, along with the

more conventional Chinese-flavored dishes, was seldom adopt-

ed by the CANL organizers.

Chinese New Year dinners have been dominated by North

American Chinese food such as lemon chicken, chicken guy

ding, fried noodles, and fried rice, as well as some locally ac-

cepted Chinese foods like B.B.Q pork and deep-fried dim sum.

More traditional Chinese festival specialties such as whole fish,

which may be eaten by Chinese Canadians at home, are rarely

served in public. The choice of catering indicates a continuous

negotiation between patrons of different traditions of Chinese

foodways. However, the North American version is more domi-

nant in the public event.

Some Chinese like Simon Tam, an engineer, argue that the

presentation of Chinese foodways at the New Year’s parties

is unable to achieve the goal of cross-cultural communication

because “they are not special and, to some degree, not even

Chinese. They are North American Chinese food.”38 Some like

Alick Tsui even consider the quality of food to be one of the

reasons that Chinese people are reluctant to attend the CANL’s

New Year celebrations.

Theodore and Lin Humphrey describe the food served at

festivals as a performance of the community’s “values, as-

sumptions, world views and prescriptive behaviors,” which are

constantly adjusted in various celebratory contexts, and which

determine how food is prepared and presented (1991 [1988]:3).

This content downloaded from

131.104.97.86 on Tue, 30 Mar 2021 00:16:26 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

FROM THE ETHNIC TO THE P UBLIC 305

The dominance of North American Chinese style food at the

Chinese New Year celebrations is often seen as the result of the

presence of outsiders who might be afraid to try exotic cuisines.

I would argue that the choice of food at the Chinese New Year

celebrations reflects the festival organizers’ views on ethnic-

ity. As current Chinese New Year celebrations are organized to

promote a creolized and multicultural Chineseness, presenting

traditional Chinese foodways is no longer a priority. The con-

sumption of North American style Chinese food which presents

a sense of both the local and the Chinese, to some degree, pro-

vides Chinese festival organizers and attendees with an oppor-

tunity to express their versions of Chineseness.

CONCLUSION

Geographic, occupational, and other differences mean that Chi-

nese individuals living in Newfoundland have different experi-

ences of the New Year festival. This contributes to the diversity

among Chinese residents in Newfoundland in terms of how

they look at the festival, both in regards to their expectations for

how Chinese New Year should be observed and what meanings

it embodies. Chiou-ling Yeh argues that the “expression of nos-

talgia might evoke the memories of some viewers and affirm

their Chinese diasporic identity, but risk [s] alienating others

who [can] not identify with the cultural references” (2008:169).

She concludes that the competing versions of memories engen-

der a “fluid, contested and heterogeneous” rather than “fixed