Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Articulo 3

Articulo 3

Uploaded by

patricia astete molinedoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Peds NBME QuestionsDocument14 pagesPeds NBME QuestionsAbrar Khan100% (7)

- Sicle Cell Concept MapDocument1 pageSicle Cell Concept MapRosa100% (1)

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Presenting As CardiacDocument7 pagesSystemic Lupus Erythematosus Presenting As CardiacSalah DeebNo ratings yet

- A Fatal Outcome of A Neonatal Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Evolutive Neonatal Lupus or Earlier Childhood - Onset Systemic Lupus? A Case ReportDocument14 pagesA Fatal Outcome of A Neonatal Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Evolutive Neonatal Lupus or Earlier Childhood - Onset Systemic Lupus? A Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Clinical Approach To Syncope in ChildrenDocument6 pagesClinical Approach To Syncope in ChildrenJahzeel Gacitúa Becerra100% (1)

- Abses Serebri2 PDFDocument22 pagesAbses Serebri2 PDFRagillia Irena FebriNo ratings yet

- 16 Syndr Cardiovas SystDocument11 pages16 Syndr Cardiovas Systjqpwzcg8xrNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document17 pagesCase Study 2api-519736590No ratings yet

- CHD by GetasewDocument35 pagesCHD by Getasewshimeles teferaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Due To Renal Artery Stenosis: Case ReportDocument6 pagesHypertension Due To Renal Artery Stenosis: Case ReportSabhina AnseliaNo ratings yet

- CardiomyopathyhomoeopathyDocument100 pagesCardiomyopathyhomoeopathys.s.r.k.m. guptaNo ratings yet

- Rossano2014 PDFDocument6 pagesRossano2014 PDFAditya SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Mds SleDocument5 pagesMds SlegabyNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument31 pagesLiterature ReviewArdi PratamaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 362971 PDFDocument24 pagesNihms 362971 PDFiliepopNo ratings yet

- 29-Years Old Woman Presenting With ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionDocument6 pages29-Years Old Woman Presenting With ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionArikahDyahLamaraNo ratings yet

- Pericarditis in LupusDocument6 pagesPericarditis in Lupusalejandro montesNo ratings yet

- Case Discussion SLEDocument4 pagesCase Discussion SLERanjeetha SivaNo ratings yet

- 8 CoaDocument15 pages8 CoaMihraban OmerNo ratings yet

- Angiolupus 4Document2 pagesAngiolupus 4AlisNo ratings yet

- 2014 Kabir Et Al. - Chronic Eosinophilic Leukaemia Presenting With A CDocument4 pages2014 Kabir Et Al. - Chronic Eosinophilic Leukaemia Presenting With A CPratyay HasanNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Toxoplasmosis in Aids PatientDocument15 pagesCerebral Toxoplasmosis in Aids PatientnoniclaraNo ratings yet

- Henoch-Schonlein Purpura A Review ArticleDocument5 pagesHenoch-Schonlein Purpura A Review ArticlerezaNo ratings yet

- A 19-Year-Old Man With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Spinal Infarction: A Case ReportDocument6 pagesA 19-Year-Old Man With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Spinal Infarction: A Case ReportJabber PaudacNo ratings yet

- Pedia TriDocument4 pagesPedia TriDIdit FAjar NUgrohoNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart Disease: Education and Practice GapsDocument18 pagesCongenital Heart Disease: Education and Practice GapsAlvaro Ignacio Lagos SuilNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetist's Evaluation of A Child With A Heart Murmur: Refresher CourseDocument4 pagesAnaesthetist's Evaluation of A Child With A Heart Murmur: Refresher CourseResya I. NoerNo ratings yet

- Morning Report: Jawaria K. Alam, MD/PGY3Document20 pagesMorning Report: Jawaria K. Alam, MD/PGY3Emily EresumaNo ratings yet

- Eda JurnalDocument13 pagesEda JurnalekalapaleloNo ratings yet

- 2021 Chowdhury AW - A Rare Combination of Complex Congenital HeartDocument4 pages2021 Chowdhury AW - A Rare Combination of Complex Congenital HeartPratyay HasanNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Disease in NeonatesDocument5 pagesCardiac Disease in NeonatesVera PetkovskaNo ratings yet

- Henoch Schoenlein PurpuraDocument10 pagesHenoch Schoenlein PurpuraAlberto Kenyo Riofrio PalaciosNo ratings yet

- M.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HDocument49 pagesM.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HMona MostafaNo ratings yet

- Adult Evans' SyndromeDocument12 pagesAdult Evans' SyndromeLilasNo ratings yet

- Sydenham Chorea 2019Document3 pagesSydenham Chorea 2019Hajrin PajriNo ratings yet

- A Cohort Study To Assess The New WHO Japanese Encephalitis Surveillance StandardsDocument9 pagesA Cohort Study To Assess The New WHO Japanese Encephalitis Surveillance StandardsarmankoassracunNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy in ChildhoodDocument20 pagesEpilepsy in ChildhoodRizky Indah SorayaNo ratings yet

- Acute Limb Ischemia Masquerading As Stroke: A Case ReportDocument7 pagesAcute Limb Ischemia Masquerading As Stroke: A Case ReporttsaniyaNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDocument16 pagesFinal Paper Rheumatic Heart DiseasePrincess TumambingNo ratings yet

- Topic 8 Differential Diagnosis of FUO SCTD - Short.Document76 pagesTopic 8 Differential Diagnosis of FUO SCTD - Short.hhbhhNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Death in A Young Medically Free Female A Case ReportDocument5 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Death in A Young Medically Free Female A Case Reporteditorial.boardNo ratings yet

- Tetralogy of Fallot, Agarwala 2017Document5 pagesTetralogy of Fallot, Agarwala 2017rinayondaNo ratings yet

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Authors: DR Jessica J Manson and DR Anisur RahmanDocument0 pagesSystemic Lupus Erythematosus: Authors: DR Jessica J Manson and DR Anisur RahmanRizka Norma WiwekaNo ratings yet

- An Approach To The Evaluation of A Patient For Seizures and EpilepsyDocument8 pagesAn Approach To The Evaluation of A Patient For Seizures and EpilepsyGaneshRajaratenamNo ratings yet

- Renal Calculi: An Unusual Presentation of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument6 pagesRenal Calculi: An Unusual Presentation of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaHussein KhalifehNo ratings yet

- Pitfalls in The Evaluation of Shortness Breath - The ClinicsDocument19 pagesPitfalls in The Evaluation of Shortness Breath - The ClinicsEdgardo Vargas AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Murmur EvaluationDocument4 pagesMurmur EvaluationManjunath GeminiNo ratings yet

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (Aps) and PregnancyDocument36 pagesAntiphospholipid Syndrome (Aps) and Pregnancyskeisham11No ratings yet

- Lupus Case ReportDocument1 pageLupus Case ReportMendy HararyNo ratings yet

- Asculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Document54 pagesAsculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Miguel M. Melchor RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Aicardi Goutieres SyndromeDocument7 pagesAicardi Goutieres Syndromezloncar3No ratings yet

- SLE DR - Nita Uul PunyaDocument18 pagesSLE DR - Nita Uul PunyaduratulkhNo ratings yet

- Nursing Case CadDocument26 pagesNursing Case CadShield DalenaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S111011642200093X MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S111011642200093X MainJeanNo ratings yet

- Pedia Ward Case ConDocument13 pagesPedia Ward Case ConAnthony Arcenal TarnateNo ratings yet

- Education and Self-Assessment: The Epidemiology of Epilepsy: The Size of The ProblemDocument11 pagesEducation and Self-Assessment: The Epidemiology of Epilepsy: The Size of The ProblemKhalvia KhairinNo ratings yet

- Review: Diagnosis and Management of Antiphospholipid Syndrome in PregnancyDocument7 pagesReview: Diagnosis and Management of Antiphospholipid Syndrome in PregnancyFebri Yudha Adhi KurniawanNo ratings yet

- ASD Internship ReportingDocument14 pagesASD Internship ReportingPernel Jose Alam MicuboNo ratings yet

- CHD SeminarDocument69 pagesCHD SeminarSayyed Ahmad KhursheedNo ratings yet

- Heart Valve Disease: State of the ArtFrom EverandHeart Valve Disease: State of the ArtJose ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular SystemDocument4 pagesCardiovascular SystemMuhammad ZahidNo ratings yet

- R3 Brochure EDDocument8 pagesR3 Brochure EDmohsin mazherNo ratings yet

- Tricuspid Valve DiseaseDocument20 pagesTricuspid Valve Diseasesarguss14100% (1)

- Doppler Systolic Signal Void in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Apical Aneurysm and Severe Obstruction Without Elevated Intraventricular VelocitiesDocument12 pagesDoppler Systolic Signal Void in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Apical Aneurysm and Severe Obstruction Without Elevated Intraventricular VelocitiesAbraham PaulNo ratings yet

- Obstructive JaundiceDocument29 pagesObstructive JaundiceBaraka SayoreNo ratings yet

- Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital vs. CapanzanaDocument34 pagesOur Lady of Lourdes Hospital vs. Capanzanaad infinitumNo ratings yet

- Scoring Pembeda ALO Vs ARDSDocument14 pagesScoring Pembeda ALO Vs ARDSRio BosariNo ratings yet

- Lindsay PDocument6 pagesLindsay PALYASNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Nursing TionkoDocument40 pagesMedical Surgical Nursing TionkojeshemaNo ratings yet

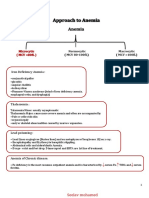

- Approach To AnemiaDocument4 pagesApproach To AnemiapNo ratings yet

- BMM 2018 0348Document14 pagesBMM 2018 0348Harpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- SOAL NO BaruDocument16 pagesSOAL NO Barukautsar abiyogaNo ratings yet

- # CLINICAL PHARMA FINALS MCQs 2021-1-30Document30 pages# CLINICAL PHARMA FINALS MCQs 2021-1-30Pavan chowdaryNo ratings yet

- Hypertension CASE REPORTDocument57 pagesHypertension CASE REPORTJulienne Sanchez-SalazarNo ratings yet

- By: Jacqueline I. Esmundo, R.N.MNDocument28 pagesBy: Jacqueline I. Esmundo, R.N.MNdomlhynNo ratings yet

- 127 FullDocument9 pages127 FullCho HyumiNo ratings yet

- Biology 10th 2021-22 Reduced Portion 1Document45 pagesBiology 10th 2021-22 Reduced Portion 1Job VacancyNo ratings yet

- Medical Examination Record FormDocument4 pagesMedical Examination Record Formspade.wolfe82No ratings yet

- HyperthyroidismDocument7 pagesHyperthyroidismayu permata dewiNo ratings yet

- Anatomic and Physiologic Overview of The BrainDocument5 pagesAnatomic and Physiologic Overview of The BrainIlona Rosabel Bitalac0% (1)

- Heart Failure BrochureDocument2 pagesHeart Failure Brochureapi-251155476No ratings yet

- BMJ 2023 075837.fullDocument10 pagesBMJ 2023 075837.fullIgor KhedeNo ratings yet

- SPSC 2018 Paper Type ADocument8 pagesSPSC 2018 Paper Type AMeenaNo ratings yet

- Dutra de Souza 2023Document11 pagesDutra de Souza 2023Paulo Emilio Marchete RohorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Deaths From AsphyxiaDocument12 pagesChapter 7 Deaths From AsphyxiaJm Lanaban50% (2)

- Multiple Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDocument31 pagesMultiple Organ Dysfunction SyndromeIbrahim Akinbola100% (1)

- 1st Yr 2 Sem Skills Pack 2020-21Document56 pages1st Yr 2 Sem Skills Pack 2020-21Francesca GrassiaNo ratings yet

- The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology Feb 2024 Volume 12number 2p83-148, E12Document72 pagesThe Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology Feb 2024 Volume 12number 2p83-148, E12Srinivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- A Comparative StudyDocument8 pagesA Comparative StudyNatalija StamenkovicNo ratings yet

Articulo 3

Articulo 3

Uploaded by

patricia astete molinedoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Articulo 3

Articulo 3

Uploaded by

patricia astete molinedoCopyright:

Available Formats

Open Access Case

Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.3478

Sub-acute Cardiac Tamponade as an Early

Clinical Presentation of Childhood Systemic

Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report

Anum Umer 1 , Shoaib Bhatti 2 , Shafaq Jawed 3

1. Medicine, The Indus Hospital, Karachi, PAK 2. Pediatric Medicine, National Institute of Child Health,

Karachi, PAK 3. Medicine, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, PAK

Corresponding author: Shoaib Bhatti, bhatti89@gmail.com

Disclosures can be found in Additional Information at the end of the article

Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease affecting multiple

systems by the process of inflammation and formation of auto-antibodies. When it presents in

childhood, it is referred to as childhood systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE). Cardiac

tamponade is a rare but potentially lethal complication of cSLE, even rarer as an initial

presentation. Sub-acute cardiac tamponade (medical tamponade) is a non-emergent type of

cardiac tamponade which develops slowly over time and does not necessarily present with

acute distress.

We present the case of an 11-year-old girl who presented to the emergency department with

complaints of intermittent fever, periorbital puffiness, abdominal distension, and swelling on

the hands and feet. She was not in any acute distress but was vitally unstable. Cardiovascular

examination revealed muffled heart sounds. Chest examination further revealed decreased

breathing sounds on the left side with dull notes on percussion. Abdominal examination

revealed positive shifting dullness with a distended abdomen.

Blood investigations were ordered which revealed anemia and thrombocytopenia. Chest X-ray

showed an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Urine detailed report showed proteinuria and

hematuria. Further investigations revealed the autoimmune root of the disease.

Echocardiography was ordered which showed a large collection of fluid around the posterior

aspect of heart with the concomitant collapse of atrial chambers suggestive of cardiac

tamponade. A diagnosis of sub-acute cardiac tamponade secondary to childhood SLE was made.

The patient was started on pulse therapy of methylprednisolone followed by a low-dose regime

of mycophenolate mofetil. The patient was also provided with positive pressure ventilation,

hemodialysis, and invasive cardiovascular monitoring along with the instillation of intravenous

fluid supplements. To our knowledge, cases of sub-acute cardiac tamponade as the only and

Received 10/08/2018

early clinical manifestation in childhood SLE are very rare.

Review began 10/14/2018

Review ended 10/15/2018

Published 10/22/2018

© Copyright 2018 Categories: Cardiology, Internal Medicine, Pathology

Umer et al. This is an open access Keywords: cardiac tamponade, systemic lupus erythematosus (sle), childhood sle, autoimmunity

article distributed under the terms of

the Creative Commons Attribution

License CC-BY 3.0., which permits Introduction

unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided Clinical presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is quite diverse as it affects almost

the original author and source are all organ systems of the human body. SLE occurs in both children and adults but it is most often

credited. seen in women of reproductive age. The most commonly affected organs are skin, joints,

How to cite this article

Umer A, Bhatti S, Jawed S (October 22, 2018) Sub-acute Cardiac Tamponade as an Early Clinical

Presentation of Childhood Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Case Report. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI

10.7759/cureus.3478

kidneys, blood vessels, and hematopoietic cells [1].

Childhood systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) constitutes approximately 20% of total SLE

cases [2]. cSLE is usually diagnosed in adolescence and is rare before five years of age with the

median age of diagnosis being 11-12 years [1]. The incidence of cSLE has been reported as 0.28-

2.22 per 100,000 children and prevalence of 1-6 per 100,000 children, with higher frequencies

in non-caucasian populations [1,3]. The heart is a commonly affected organ in all forms of SLE

including cSLE. Pericarditis and pericardial effusion are the two well-recognized complications

of cSLE, but cardiac tamponade is an unusual occurrence and even rarer as an initial

presentation of SLE. Acute cardiac tamponade is a medical emergency but sub-acute cardiac

tamponade is not always an emergency [4-5].

Here, we present a case of cSLE which involves an 11-year-old girl with sub-acute tamponade

as an early clinical sign of cSLE. This, to our knowledge, has been very rarely reported and

presents with different manifestations than in our case [6].

An important relationship to investigate is whether cardiac tamponade is a rare occurrence in

cSLE or a rare occurrence only as an initial presentation. It is known that in adult SLE, cardiac

tamponade is rare both as a complication and also as an initial presentation. However, it is still

unknown if this association is also true in cases of cSLE.

Case Presentation

An 11-year-old female was admitted to the emergency department with complaints of

intermittent fever for over one month, periorbital puffiness for four days, and abdominal

distension with swelling on hands and feet for one day. In the hospital, she developed

periorbital bruising and rashes on the extensor surfaces followed by the trunk over a period of

four days. The patient experienced difficulty in walking due to a history of joint pain which was

profound at the knee joint. However, there was no history of morning stiffness.

She denied photosensitivity, chest pain, shortness of breath, hair loss, oral ulcers, weight loss,

fatigue, and any medication use. There was no known family history of autoimmune diseases.

The patient reported having suffered from measles seven months back.

On examination, she was a tall, lean-built child, lying on bed, oriented to time, person, and

place. Her vital signs on arrival were as follows: blood pressure, 142/110 mmHg (reference,

120/80 mmHg); pulse, 154 bpm (reference range, 75 to 118 bpm); and temperature, 37.5o C

(reference range, 36.5 to 37.5o C). Her height was measured as 130 cm (at third centile) and

weight, 25 kg below the third centile. The patient appeared sick-looking, with signs of pallor,

conjunctival hemorrhage, and bruises around the eyes. Palpable purpura and petechiae over the

extensor surfaces were seen whereas edema of the hands and feet was noted. Central nervous

system (CNS) examination revealed 15/15 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Cardiovascular

examination revealed muffled heart sounds and good volume pulse. Chest examination

revealed decreased breathing sounds on the left side of the chest with dull notes on percussion.

Abdominal examination revealed positive shifting dullness with a distended abdomen.

Diagnostic criteria

Suspicion of SLE was raised on clinical findings, therefore, work-up for SLE was ordered. The

updated diagnostic criteria of SLE was used which the patient fulfilled. Diagnosis of SLE is

made if four out of 17 (including at least one of the eleven clinical and one of the six

immunological) “Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification

criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus” are present. Biopsy-proven lupus nephritis with a

2018 Umer et al. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3478 2 of 7

positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) or anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibody

(anti-dsDNA) also satisfies the diagnosis of SLE [1]. From the clinical criteria of SLICC, the

following four were present in our patient: (i) serositis (muffled heart sounds and chest X-ray

showing pericardial effusion); (ii) acute cutaneous lupus (conjunctival hemorrhage, bruises

around eyes, palpable purpura, and petechiae over the extensor surfaces); (iii) renal

(proteinuria, red blood cell casts); and (iv) raised spot urine protein/creatinine ratio.

From the six immunological criteria of SLICC, the following four were present: (i) ANA positive;

(ii) C3 & C4 levels decreased; (iii) anti-dsDNA positive; and (iv) direct Coombs test positive.

Chest radiograph showed an enlarged cardiac silhouette indicative of pericardial effusion

(Figure 1). Echocardiography revealed a large collection of fluid around the posterior aspect of

heart with atrial collapse strongly suggestive of cardiac tamponade.

FIGURE 1: Chest radiograph showing enlarged cardiac

silhouette

Investigative analysis revealed that the patient was anemic and thrombocytopenic but with a

normal leukocyte count. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 92. Urine protein creatinine

ratio was raised at 11.98 (reference, <0.3). Urine detailed report showed proteinuria and

hematuria. Blood urea trend was recorded for six days which revealed an increasing pattern

starting at 149 mg/dL on the first day to 168 mg/dL on the last day (reference range, 10 to 40

2018 Umer et al. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3478 3 of 7

mg/dL). Creatinine levels showed a decreasing six-day pattern ranging from 1.49 mg/dL at first

day to 1.03 mg/dL on the sixth day (reference range, 0.2 to 1.1 mg/dL). These lab values were

suggestive of the autoimmune root of the disease and the renal dysfunction secondary to it

(Table 1).

Date 26/8/2018 28/8/2018 29/8/2018 30/8/2018 2/9/2018 4/9/2018

Urea (reference range, 10–40 mg/dL) 149 mg/dL 160 mg/dL 171 mg/dL 175 mg/dL 191 mg/dL 168 mg/dL

Creatinine (reference range, 0.2–1.1

1.49 mg/dL 1.68 mg/dL 1.22 mg/dL 1.18 mg/dL 1.23 mg/dL 1.03 mg/dL

mg/dL)

TABLE 1: Series of urea and creatinine levels

Apart from ANA and anti-dsDNA positivity, the patient's serum came out positive for anti-

Ro/SSA (anti-Sjogren's-syndrome-related antigen A, also called anti-Ro, or the combination

anti-SSA/Ro or anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies) and anti-La/SSB antibodies. Direct Coombs test

was also positive. Serum complement levels were low with a C3 of 45 mg/dL (reference range,

101 to 186 mg/dL) and C4 of 8 mg/dL (reference range, 16 to 47 mg/dL). Thus, confirming the

diagnosis of cSLE with cardiac tamponade.

As a management and definitive diagnostic tool, a fluoroscopy-guided pericardiocentesis was

performed without any delay. A total of 430 ml of fluid was drained which was hemorrhagic;

cytological analysis of the fluid was negative for malignancy with 60% neutrophils and 40%

lymphocytes. Infectious workup was negative for acid-fast bacilli, any growth, or vegetation.

Renal biopsy was performed to confirm the underlying cause of renal malfunction, as

hypertension and proteinuria was noticed. Post-pericardiocentesis echocardiogram showed

trace pericardial effusion and an ejection fraction of 35% with overall improvement.

The patient was managed for lupus carditis and nephritis and started on pulse therapy of

intravenous methylprednisolone (500 to 1000 mg). This was followed by a low dose regime and

treatment with mycophenolate mofetil starting on the seventh day which was aimed at

reducing renal disease progression. The patient was continuously provided with organ support

care such as positive pressure ventilation, hemodialysis, and invasive cardiovascular

monitoring along with the instillation of intravenous fluid supplements. The patient improved

significantly, was discharged from our hospital, and asked to follow up.

Discussion

SLE is a heterogeneous autoimmune disease with diverse and complicated systemic

manifestations [7]. There is a double incidence of SLE in the pediatric population of developing

countries as compared to developed countries (16% - 23.5%) [8]. Despite a high occurrence

index, there is a delay in the diagnosis of many cases, probably due to the variable clinical

presentation of SLE [9]. SLE can involve any organ of the body; however, it is reported that

childhood SLE has worse progression of the disease as compared to adults [1].

A retrospective study from Karachi, Pakistan reports that the most common presentation of SLE

included fever (53%), malar rash (29%), photosensitivity (6%), arthropathy (38%), and renal

involvement (33%) [10]. Pericarditis is the most common sign of lupus carditis; approximately

25% of patients with cardiac concurrence have pericarditis as a significant feature on

2018 Umer et al. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3478 4 of 7

echocardiogram [11]. In cSLE, the most commonly reported cardiac lesion is myocarditis.

However, the incidence of cardiac lesions in cSLE is lower compared to adult SLE. Conversely,

our patient presented with cardiac tamponade as an initial presentation which is a rare finding

in the setting of lupus carditis and even rarer in childhood SLE [12]. Moreover, our patient does

not have typical cardiac tamponade but sub-acute cardiac tamponade. SLE does present with

both acute and sub-acute cardiac tamponade but the incidence of the latter is much lower.

A retrospective study of 409 patients revealed that only 5.9% of patients had SLE accompanied

with cardiac tamponade [13]. A French study showed a picture of diverse and often severe

initial manifestations seen in cSLE. It is recommended that SLE should be made a differential

immediately in any febrile adolescent with unexplained organ involvement [14].

Pediatric patients with complement deficiencies can present with SLE-like manifestations but

they usually present with rashes, glomerulonephritis, and rheumatic fever [15].

The clinical and immunological findings in our patient satisfied the SLICC classification criteria

for SLE [1]. However, in addition, our patient presented with muffled heart sounds, tachycardia,

and hypertension. Hypertension is common in cases of sub-acute tamponade and hypotension

is common in cases of acute tamponade. Although tachycardia and decreased heart sounds are

the two features that lack specificity and sensitivity for cardiac tamponade, these are

nonetheless commonly reported. Classical signs of acute cardiac tamponade such as jugular

venous distension, pulsus paradoxus, hypotension and dyspnea are not always seen in sub-

acute tamponade due to a variety of reasons, such as assessment of jugular venous distention

being observer-dependent, and pulsus paradoxus having low specificity and sensitivity for

cardiac tamponade [16].

Thus we should rely on radiological investigations when cardiac tamponade is suspected. The

most appropriate tool for diagnosing cardiac tamponade is echocardiography, which is

preferable over cardiac catheterization due to its non-invasive approach. Echocardiography will

show pericardial effusion and chamber collapse. Right ventricular collapse is more specific

compared to right atrial collapse for cardiac tamponade; however, it is less sensitive [16]. In our

case, atrial collapse is observed.

The most common management option for tamponade is pericardiocentesis. This procedure

involves drainage of pericardial fluid with a 16 or 18 gauge needle inserted at an angle of 30 to

45 degrees to the skin near the left xiphoid margin. Pericardiocentesis works as a management

option as well as a diagnostic means by which pericardial fluid can be analyzed, in order to

reveal the underlying etiology of effusion [17].

Management of SLE includes combination therapy with steroids and immunosuppressants such

as mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. This regime slows the disease progression and

prevents organ damage mainly by inactivating the autoantibodies. A randomized trial of 340

patients which evaluated the efficacy of the aforementioned drugs, in combination with

prednisolone in adolescents, revealed that mycophenolate mofetil was superior in preventing

remission and kidney damage as a result of lupus nephritis [18].

The initial differential diagnosis for cSLE includes infections (sepsis, Epstein-Barr virus,

parvovirus B19), malignancies, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, other rheumatologic

conditions, and drug-induced lupus amongst others [1]. We kept SLE, vasculitis, and juvenile

rheumatoid arthritis as a working diagnosis when the patient first presented to the hospital.

Tuberculosis remains the most common cause of pleural effusion in the pediatric population of

South Asia [19]. The low serum levels of C4 complement are known to have a stronger

2018 Umer et al. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3478 5 of 7

association with cSLE as compared to SLE in adults. Low serum C4 levels and the young age of

disease onset is found to be major predisposing factors towards pericarditis [20]. Serological,

radiological, and clinical diagnostic measures should be used to identify the etiology of cardiac

tamponade promptly in order to initiate appropriate treatment. Sub-acute tamponade does not

always have the typical clinical presentation of cardiac tamponade, so keen observation and

thorough investigation is important in these cases. Childhood SLE should be kept in

differentials if a patient presents with prolonged fever, peripheral edema, rashes, signs of

pericardial effusion, or any unexplained organ involvement especially in the presence of high

ESR [14].

Conclusions

Cardiac tamponade is a rare initial presentation in childhood SLE. Sub-acute cardiac

tamponade is a less common form of tamponade which has more of an insidious onset. We

report a case of childhood SLE with sub-acute cardiac tamponade as an initial presentation.

Childhood SLE has a diverse pattern of clinical presentation, so it is crucial for physicians to

identify cardiac tamponade as a probable indication of cSLE and proceed accordingly.

Echocardiography and analysis of pericardial fluid are two important diagnostic measures

whereas early recognition of cardiac tamponade can prevent morbidity and mortality as

tamponade is known to affect pediatric population more severely than adults. The treatment

options for cSLE include high dose steroid therapy with an immunosuppressant whereas

pericardiocentesis is done for tamponade. Prognosis is good with prompt treatment.

Additional Information

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained by all participants in this study. National Institute of

Child Health issued approval NA. Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform

disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have

declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at

present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in

the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other

relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Ardoln SP, Schanberg LE: Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.

Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, Geme JWS, Schor NF, Behrman RE (ed): Elsevier, Philadelphia;

2012. 19:841-5.

2. Mina R, Brunner HI: Update on differences between childhood-onset and adult-onset

systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013, 15:218. 10.1186/ar4256

3. Hiraki LT, Benseler SM, Tyrrell PN, Harvey E, Hebert D, Silverman ED: Ethnic differences in

pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009, 36:2539-46.

10.3899/jrheum.081141

4. Hejtmancik MR, Wright JC, Quint R, Jennings FL: The cardiovascular manifestations of

systemic lupus erythematosus. Am Heart J. 1964, 68:119-30.

5. Maharaj SS, Chang SM: Cardiac tamponade as the initial presentation of systemic lupus

erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2015, 13:9.

10.1186/s12969-015-0005-0

6. Ambrose N, Morgan TA, Galloway J, Ionnoau Y, Beresford MW, Isenberg DA: Differences in

disease phenotype and severity in SLE across age groups. Lupus. 2016, 25:1542-50.

10.1177/0961203316644333

7. Yu C, Gershwin ME, Chang C: Diagnostic criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus: a critical

review. J Autoimmun. 2014, 48:10-13. 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.004

2018 Umer et al. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3478 6 of 7

8. Arkachaisri T, Tang SP, Daengsuwan T, et al.: Paediatric rheumatology clinic population in

Southeast Asia: are we different?. Rheumatology. 2017, 56:390-398.

10.1093/rheumatology/kew446

9. Ishaq M, Nazir L, Riaz A, Kidwai SS, Haroon W, Siddiqi S: Lupus, still a mystery: a comparison

of clinical features of Pakistani population living in suburbs of Karachi with other Asian

countries. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013, 63:869-72.

10. Rabbani MA, Siddqui BK, Tahir MH, et al.: Do clinical manifestations of systemic lupus

erythematosus in Pakistan correlate with rest of Asia?. J Pak Med Assoc. 2006, 56:222.

11. Miner JJ, Kim AH: Cardiac manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus . Rheum Dis Clin

North Am. 2014, 40:51-60.

12. Mavrogeni S, Smerla R, Grigoriadou G, et al.: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance evaluation

of paediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and cardiac symptoms. Lupus. 2016,

25:289-95. 10.1177/0961203315611496

13. Goswami RP, Sircar G, Ghosh A, Ghosh P: Cardiac tamponade in systemic lupus

erythematosus. QJM Int J Med. 2018, 111:83-87. 10.1093/qjmed/hcx195

14. Bader-Meunier B, Armengaud JB, Haddad E, et al.: Initial presentation of childhood-onset

systemic lupus erythematosus: a French multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2005, 146:648-53.

10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.045

15. Pickering MC, Walport MJ: Links between complement abnormalities and systemic lupus

erythematosus. Rheumatology. 2000, 39:133-41.

16. Argulian E, Messerli F: Misconceptions and facts about pericardial effusion and tamponade .

Am J Med. 2013, 126:858-61. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.03.022

17. Tsang TS, Enriquez-Sarano M, Freeman WK, et al.: Consecutive 1127 therapeutic

echocardiographically guided pericardiocenteses: clinical profile, practice patterns, and

outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002, 77:429-36. 10.4065/77.5.429

18. Sundel R, Solomons N, Lisk L: Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in adolescent patients with

lupus nephritis: evidence from a two-phase, prospective randomized trial. Lupus. 2012,

21:1433-43. 10.1177/0961203312458466

19. Guven H, Bakiler AR, Ulger Z, Iseri B, Kozan M, Dorak C: Evaluation of children with a large

pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Acta Cardiol. 2007, 62:129-33.

10.2143/AC.62.2.2020232

20. Pereira KM, Faria AG, Liphaus BL, et al.: Low C4, C4A and C4B gene copy numbers are

stronger risk factors for juvenile-onset than for adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus.

Rheumatology. 2016, 55:869-73. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev436

2018 Umer et al. Cureus 10(10): e3478. DOI 10.7759/cureus.3478 7 of 7

You might also like

- Peds NBME QuestionsDocument14 pagesPeds NBME QuestionsAbrar Khan100% (7)

- Sicle Cell Concept MapDocument1 pageSicle Cell Concept MapRosa100% (1)

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Presenting As CardiacDocument7 pagesSystemic Lupus Erythematosus Presenting As CardiacSalah DeebNo ratings yet

- A Fatal Outcome of A Neonatal Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Evolutive Neonatal Lupus or Earlier Childhood - Onset Systemic Lupus? A Case ReportDocument14 pagesA Fatal Outcome of A Neonatal Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Evolutive Neonatal Lupus or Earlier Childhood - Onset Systemic Lupus? A Case ReportIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Clinical Approach To Syncope in ChildrenDocument6 pagesClinical Approach To Syncope in ChildrenJahzeel Gacitúa Becerra100% (1)

- Abses Serebri2 PDFDocument22 pagesAbses Serebri2 PDFRagillia Irena FebriNo ratings yet

- 16 Syndr Cardiovas SystDocument11 pages16 Syndr Cardiovas Systjqpwzcg8xrNo ratings yet

- Case Study 2Document17 pagesCase Study 2api-519736590No ratings yet

- CHD by GetasewDocument35 pagesCHD by Getasewshimeles teferaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension Due To Renal Artery Stenosis: Case ReportDocument6 pagesHypertension Due To Renal Artery Stenosis: Case ReportSabhina AnseliaNo ratings yet

- CardiomyopathyhomoeopathyDocument100 pagesCardiomyopathyhomoeopathys.s.r.k.m. guptaNo ratings yet

- Rossano2014 PDFDocument6 pagesRossano2014 PDFAditya SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Mds SleDocument5 pagesMds SlegabyNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument31 pagesLiterature ReviewArdi PratamaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 362971 PDFDocument24 pagesNihms 362971 PDFiliepopNo ratings yet

- 29-Years Old Woman Presenting With ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionDocument6 pages29-Years Old Woman Presenting With ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionArikahDyahLamaraNo ratings yet

- Pericarditis in LupusDocument6 pagesPericarditis in Lupusalejandro montesNo ratings yet

- Case Discussion SLEDocument4 pagesCase Discussion SLERanjeetha SivaNo ratings yet

- 8 CoaDocument15 pages8 CoaMihraban OmerNo ratings yet

- Angiolupus 4Document2 pagesAngiolupus 4AlisNo ratings yet

- 2014 Kabir Et Al. - Chronic Eosinophilic Leukaemia Presenting With A CDocument4 pages2014 Kabir Et Al. - Chronic Eosinophilic Leukaemia Presenting With A CPratyay HasanNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Toxoplasmosis in Aids PatientDocument15 pagesCerebral Toxoplasmosis in Aids PatientnoniclaraNo ratings yet

- Henoch-Schonlein Purpura A Review ArticleDocument5 pagesHenoch-Schonlein Purpura A Review ArticlerezaNo ratings yet

- A 19-Year-Old Man With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Spinal Infarction: A Case ReportDocument6 pagesA 19-Year-Old Man With Sickle Cell Disease Presenting With Spinal Infarction: A Case ReportJabber PaudacNo ratings yet

- Pedia TriDocument4 pagesPedia TriDIdit FAjar NUgrohoNo ratings yet

- Congenital Heart Disease: Education and Practice GapsDocument18 pagesCongenital Heart Disease: Education and Practice GapsAlvaro Ignacio Lagos SuilNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetist's Evaluation of A Child With A Heart Murmur: Refresher CourseDocument4 pagesAnaesthetist's Evaluation of A Child With A Heart Murmur: Refresher CourseResya I. NoerNo ratings yet

- Morning Report: Jawaria K. Alam, MD/PGY3Document20 pagesMorning Report: Jawaria K. Alam, MD/PGY3Emily EresumaNo ratings yet

- Eda JurnalDocument13 pagesEda JurnalekalapaleloNo ratings yet

- 2021 Chowdhury AW - A Rare Combination of Complex Congenital HeartDocument4 pages2021 Chowdhury AW - A Rare Combination of Complex Congenital HeartPratyay HasanNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Disease in NeonatesDocument5 pagesCardiac Disease in NeonatesVera PetkovskaNo ratings yet

- Henoch Schoenlein PurpuraDocument10 pagesHenoch Schoenlein PurpuraAlberto Kenyo Riofrio PalaciosNo ratings yet

- M.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HDocument49 pagesM.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HMona MostafaNo ratings yet

- Adult Evans' SyndromeDocument12 pagesAdult Evans' SyndromeLilasNo ratings yet

- Sydenham Chorea 2019Document3 pagesSydenham Chorea 2019Hajrin PajriNo ratings yet

- A Cohort Study To Assess The New WHO Japanese Encephalitis Surveillance StandardsDocument9 pagesA Cohort Study To Assess The New WHO Japanese Encephalitis Surveillance StandardsarmankoassracunNo ratings yet

- Epilepsy in ChildhoodDocument20 pagesEpilepsy in ChildhoodRizky Indah SorayaNo ratings yet

- Acute Limb Ischemia Masquerading As Stroke: A Case ReportDocument7 pagesAcute Limb Ischemia Masquerading As Stroke: A Case ReporttsaniyaNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Rheumatic Heart DiseaseDocument16 pagesFinal Paper Rheumatic Heart DiseasePrincess TumambingNo ratings yet

- Topic 8 Differential Diagnosis of FUO SCTD - Short.Document76 pagesTopic 8 Differential Diagnosis of FUO SCTD - Short.hhbhhNo ratings yet

- Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Death in A Young Medically Free Female A Case ReportDocument5 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Death in A Young Medically Free Female A Case Reporteditorial.boardNo ratings yet

- Tetralogy of Fallot, Agarwala 2017Document5 pagesTetralogy of Fallot, Agarwala 2017rinayondaNo ratings yet

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Authors: DR Jessica J Manson and DR Anisur RahmanDocument0 pagesSystemic Lupus Erythematosus: Authors: DR Jessica J Manson and DR Anisur RahmanRizka Norma WiwekaNo ratings yet

- An Approach To The Evaluation of A Patient For Seizures and EpilepsyDocument8 pagesAn Approach To The Evaluation of A Patient For Seizures and EpilepsyGaneshRajaratenamNo ratings yet

- Renal Calculi: An Unusual Presentation of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument6 pagesRenal Calculi: An Unusual Presentation of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaHussein KhalifehNo ratings yet

- Pitfalls in The Evaluation of Shortness Breath - The ClinicsDocument19 pagesPitfalls in The Evaluation of Shortness Breath - The ClinicsEdgardo Vargas AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Murmur EvaluationDocument4 pagesMurmur EvaluationManjunath GeminiNo ratings yet

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (Aps) and PregnancyDocument36 pagesAntiphospholipid Syndrome (Aps) and Pregnancyskeisham11No ratings yet

- Lupus Case ReportDocument1 pageLupus Case ReportMendy HararyNo ratings yet

- Asculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Document54 pagesAsculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Miguel M. Melchor RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Aicardi Goutieres SyndromeDocument7 pagesAicardi Goutieres Syndromezloncar3No ratings yet

- SLE DR - Nita Uul PunyaDocument18 pagesSLE DR - Nita Uul PunyaduratulkhNo ratings yet

- Nursing Case CadDocument26 pagesNursing Case CadShield DalenaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S111011642200093X MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S111011642200093X MainJeanNo ratings yet

- Pedia Ward Case ConDocument13 pagesPedia Ward Case ConAnthony Arcenal TarnateNo ratings yet

- Education and Self-Assessment: The Epidemiology of Epilepsy: The Size of The ProblemDocument11 pagesEducation and Self-Assessment: The Epidemiology of Epilepsy: The Size of The ProblemKhalvia KhairinNo ratings yet

- Review: Diagnosis and Management of Antiphospholipid Syndrome in PregnancyDocument7 pagesReview: Diagnosis and Management of Antiphospholipid Syndrome in PregnancyFebri Yudha Adhi KurniawanNo ratings yet

- ASD Internship ReportingDocument14 pagesASD Internship ReportingPernel Jose Alam MicuboNo ratings yet

- CHD SeminarDocument69 pagesCHD SeminarSayyed Ahmad KhursheedNo ratings yet

- Heart Valve Disease: State of the ArtFrom EverandHeart Valve Disease: State of the ArtJose ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular SystemDocument4 pagesCardiovascular SystemMuhammad ZahidNo ratings yet

- R3 Brochure EDDocument8 pagesR3 Brochure EDmohsin mazherNo ratings yet

- Tricuspid Valve DiseaseDocument20 pagesTricuspid Valve Diseasesarguss14100% (1)

- Doppler Systolic Signal Void in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Apical Aneurysm and Severe Obstruction Without Elevated Intraventricular VelocitiesDocument12 pagesDoppler Systolic Signal Void in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Apical Aneurysm and Severe Obstruction Without Elevated Intraventricular VelocitiesAbraham PaulNo ratings yet

- Obstructive JaundiceDocument29 pagesObstructive JaundiceBaraka SayoreNo ratings yet

- Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital vs. CapanzanaDocument34 pagesOur Lady of Lourdes Hospital vs. Capanzanaad infinitumNo ratings yet

- Scoring Pembeda ALO Vs ARDSDocument14 pagesScoring Pembeda ALO Vs ARDSRio BosariNo ratings yet

- Lindsay PDocument6 pagesLindsay PALYASNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Nursing TionkoDocument40 pagesMedical Surgical Nursing TionkojeshemaNo ratings yet

- Approach To AnemiaDocument4 pagesApproach To AnemiapNo ratings yet

- BMM 2018 0348Document14 pagesBMM 2018 0348Harpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- SOAL NO BaruDocument16 pagesSOAL NO Barukautsar abiyogaNo ratings yet

- # CLINICAL PHARMA FINALS MCQs 2021-1-30Document30 pages# CLINICAL PHARMA FINALS MCQs 2021-1-30Pavan chowdaryNo ratings yet

- Hypertension CASE REPORTDocument57 pagesHypertension CASE REPORTJulienne Sanchez-SalazarNo ratings yet

- By: Jacqueline I. Esmundo, R.N.MNDocument28 pagesBy: Jacqueline I. Esmundo, R.N.MNdomlhynNo ratings yet

- 127 FullDocument9 pages127 FullCho HyumiNo ratings yet

- Biology 10th 2021-22 Reduced Portion 1Document45 pagesBiology 10th 2021-22 Reduced Portion 1Job VacancyNo ratings yet

- Medical Examination Record FormDocument4 pagesMedical Examination Record Formspade.wolfe82No ratings yet

- HyperthyroidismDocument7 pagesHyperthyroidismayu permata dewiNo ratings yet

- Anatomic and Physiologic Overview of The BrainDocument5 pagesAnatomic and Physiologic Overview of The BrainIlona Rosabel Bitalac0% (1)

- Heart Failure BrochureDocument2 pagesHeart Failure Brochureapi-251155476No ratings yet

- BMJ 2023 075837.fullDocument10 pagesBMJ 2023 075837.fullIgor KhedeNo ratings yet

- SPSC 2018 Paper Type ADocument8 pagesSPSC 2018 Paper Type AMeenaNo ratings yet

- Dutra de Souza 2023Document11 pagesDutra de Souza 2023Paulo Emilio Marchete RohorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Deaths From AsphyxiaDocument12 pagesChapter 7 Deaths From AsphyxiaJm Lanaban50% (2)

- Multiple Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDocument31 pagesMultiple Organ Dysfunction SyndromeIbrahim Akinbola100% (1)

- 1st Yr 2 Sem Skills Pack 2020-21Document56 pages1st Yr 2 Sem Skills Pack 2020-21Francesca GrassiaNo ratings yet

- The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology Feb 2024 Volume 12number 2p83-148, E12Document72 pagesThe Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology Feb 2024 Volume 12number 2p83-148, E12Srinivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- A Comparative StudyDocument8 pagesA Comparative StudyNatalija StamenkovicNo ratings yet