Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 118.101.170.171 On Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

This Content Downloaded From 118.101.170.171 On Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

Uploaded by

Seph LwlOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 118.101.170.171 On Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

This Content Downloaded From 118.101.170.171 On Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

Uploaded by

Seph LwlCopyright:

Available Formats

Consumer Online Privacy: Legal and Ethical Issues

Author(s): Eve M. Caudill and Patrick E. Murphy

Source: Journal of Public Policy & Marketing , Spring, 2000, Vol. 19, No. 1, Privacy and

Ethical Issues in Database/Interactive Marketing and Public Policy (Spring, 2000), pp. 7-

19

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of American Marketing Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30000483

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Marketing Association and Sage Publications, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Public Policy & Marketing

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Consumer Online Privacy: Legal and Ethical Issues

Eve M. Caudill and Patrick E. Murphy

Consumer privacy is a public policy issue that has received substantial attention over the

last thirty years. The phenomenal growth of the Internet has spawned several new concerns

about protecting the privacy of consumers. The authors examine both historical and con-

ceptual analyses of privacy and discuss domestic and international regulatory and self-

regulatory approaches to confronting privacy issues on the Internet. The authors also

review ethical theories that apply to consumer privacy and offer specific suggestions for

corporate ethical policy and public policy as well as a research agenda.

Tracking the movements of consumers as they shop for mation is available on most consumers who use credit cards,

goods is not a new phenomenon. Marketers have long own cars and homes, and are active spenders (Cespedes and

collected data to assist in making decisions: They Smith 1993; DeCew 1997). Use of automated dialing sys-

have watched while buyers pick out strawberries and noted tems, caller ID, and e-mail have brought criticism of mar-

the process parents go through to choose a box of cereal. keting research, advertising, and the traditional marketing

Consumers do not appear concerned about this invasion of system (Foxman and Kilcoyne 1993). The direct mail indus-

privacy; after all, they are in a public place and the informa- try has also been targeted for ongoing threats to consumer

tion being collected-what they have in their cart and ulti- privacy (Milne and Gordon 1993; Phelps, Nowak, and

mately purchase as well as the products they inspect-can Ferrell 1999). And on the Internet, well-known companies

be readily observed. Perhaps this lack of concern is based on have been criticized: America Online for attempting to sell

their assumption of anonymity; their shopping behaviors are subscribers' telephone numbers, and Intel for developing

collected to study patterns in the aggregate. When informa- the new Pentium chip that identifies users.

tion is collected at the cash register, customers can choose to As use of the Internet grows, so do concerns regarding

opt in through the use of a personal shopping card, a credit online collection and use of consumer information. In several

card, or a check. Presumably, customers knowingly give up surveys, respondents have told marketers that questions about

some of their privacy in this transaction in return for some- privacy affect their purchasing decisions. A U.S. Department

thing of value-a product discount, credit, future coupons of Commerce study tracking e-commerce and privacy finds

on heavily used items, and so forth. Anonymity remains, concern about online threats to privacy among 81% of

however, if they use cash and resist requests for their phone Internet users and 79% of consumers who buy products and

number, address, or zip code. services over the Web (Oberndorf 1998). These percentages

This anonymity changes when consumers move onto the reflect the seriousness of the problem and a possible impedi-

Internet. No longer are their shopping behaviors available ment to broad-scale adoption of the Internet for purchasing

only in the aggregate. Instead, individuals are tracked, and decisions. For example, Microsoft was hammered by privacy

information is collected from purchasing transactions as buffs because its Windows 98 software, when used on a net-

they surf through Web sites. The exchange of value between work, creates identifiers that are collected during registration,

marketer and consumer becomes less defined in this new which results in a vast database of personal information about

retail (now e-tail) setting than it is in a brick-and-mortar its customers. Microsoft insisted that these features were

store environment. The following questions outline the con- designed to improve services, but fearing a backlash, the

cerns raised by this shift in exchange venues: company has promised to modify them. It claimed customers

can bow out when they register for Windows 98, and it

*What are the privacy issues pertinent to online marketers col-

lecting and using a consumer's information? pledged to expunge personal data it collected improperly

(Baig, Stepanek, and Gross 1999) (for several extended

*What are the ethical responsibilities of online marketers?

examples of consumer privacy concerns, see the Appendix).

*What policy initiatives are needed in this new transactional

environment? The purpose of this article, then, is to assess the current

landscape and address future challenges regarding online

Privacy as it relates to consumer information is not a new

privacy. As we noted previously, many of the existing mar-

problem in marketing. The growth of databases, such as keting and privacy paradigms are challenged in the Internet

Lexis-Nexis, has meant that a virtual "mountain" of infor- environment. We examine historical perspectives and con-

temporary initiatives on consumer privacy in both self-

regulation and government regulation in marketing, giving

EVE M. CAUDILL is Visiting Assistant Professor of Marketing, andattention to both U.S. and international contexts. Our

PATRICK E. MURPHY is Professor and Chair, Department ofintended contribution is to offer ethical, public policy, and

Marketing, University of Notre Dame. The authors thank the spe-

managerial insights into these perplexing issues facing mar-

cial issue editor and the three anonymous JPP&M reviewers for

their helpful suggestions on previous versions of this article.

keting organizations in the new century. We also set an

agenda for further research.

Vol. 19 (1)

Spring 2000, 7-19 Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 7

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 Consumer Online Privacy

Communications

A Conceptual Analysis ofAct (1984) covers cable companies' col-

Privacy

lection and use of subscriber information. The Computer

Several legal and philosophical scholars have examined the

Security Act (1987) outlines minimum acceptable security

topic of privacy in the home, in the workplace, and in pub-

plans for federal agencies with computer systems. Finally,

lic. A debate in law and philosophy has centered on whether

the Video Protection Privacy Act (1988) requires subscriber

a narrow (Parent 1983) or consent

broad (DeCew

for the disclosure of video sales 1997; Schoeman

and rental informa-

1992) view of privacy should be used for legal and ethical

tion (Bloom, Milne, and Adler 1994). The 1990s has seen

assessments of individual actions. Fried (1968) wrote one of

only sporadic attempts to protect privacy at the federal level.

the first and most important philosophical treatments of pri-

This brief discussion shows that the majority of U.S. busi-

vacy. He claims that privacy is instrumentally valuable

nesses are not regulated in their collection and use of cus-

because it is necessary to develop

tomer data. intimacy and trust in rela-

tionships. At approximately the same time, Westin (1967)

examined privacy and the fundamental

Consumer Privacy right of freedom.

Furthermore, Rachels (1975) argues that people need to con-

Consumer privacy, a subset of privacy, has been described

trol information about themselves to maintain a diversity of

as both a two-dimensional construct, involving physical

relationships. Most recently, Nissenbaum (1998) raises the

space and information (Goodwin 1991), and a continuum,

notion of "privacy in public" that deals with retailers; mail

contingent on consumers and their individual experience

order firms; medical care givers; and other organizations

(Foxman and Kilcoyne 1993). A continuum suggests that

that collect, store, analyze, and share information about con-

consumers have varying degrees of concern with privacy

sumers. She likens these efforts to a type of public surveil-

and place different values on their personal information;

lance that "constitute[s] a genuine moral violation of pri-

therefore, some consumers may be willing to trade away

vacy" (p. 593). information for a more valued incentive. An illustration of

Privacy and Legal Issues those trade-offs involves Catalina Marketing Corporation,

which offers a variety of incentives to induce consumers to

Even though the right to privacy was not explicitly men-

provide personal information. For example, a person's zip

tioned in the Bill of Rights, the topic has been debated for

code and preferred supermarket is worth $40 of national

more than a century. In "one of the most influential law

coupons, and a personal shopping card number garners free

review articles ever written" (DeCew 1997, p. 14), former

products (Quick 1998; Thomas 1998).

Chief Justice Louis Brandeis and a colleague argued for a

As previously stated, consumer privacy is confined to the

broad interpretation of a person's right to privacy (Warren

context of information and includes Foxman and Kilcoyne's

and Brandeis 1890). It appears significant that this article

(1993) two factors of control and knowledge. Thus, the vio-

defending consumers occurred in the same year as the pas-

lation of privacy depends on (1) consumers' control of their

sage of the Sherman Act (26 Stat. 209), which deals with

information in a marketing interaction (i.e., Can consumers

antitrust and competitive issues. Furthermore, the First,

decide the amount and the depth of information collected?)

Third, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments

and (2) the degree of their knowledge of the collection and

provide for protections that fall under the general rubric of

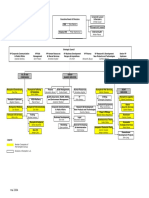

use of their personal information. In Figure 1, we describe

privacy (DeCew 1997; Gillmor et al. 1990).1 In addition, a

consumers' control and knowledge applied to the Internet;

substantial body of total law serves to protect individuals'

included in this taxonomy are two behaviors consumers

privacy (for a brief review, see Schoeman 1992).

engage in on the Internet: purchasing and surfing. We also list

Legal protection for individual privacy in the United

issues pertinent to each cell according to whether consumers

States is relatively recent, as the first federal law passed less

have control and/or knowledge when accessing the Internet.

than thirty years ago. This legislation has been limited pri-

marily to the protection of data in the context of specific

Use of the Internet

government functions or the practices of particular indus-

tries, including credit reporting, video rental, and banking Internet use has grown exponentially in the 1990s. Although

(for a list of privacy laws, see Table 1). In the 1970s, pro- it was negligible in the mid-1990s, use by North American

tection involved consumer notification and the correction of consumers had risen to almost 60 million by 1997. More

inaccuracies in consumers' records. Later legislation than 80 million U.S. citizens were using the Internet in 1999.

extended protection to cover unauthorized break-ins and Online use is predicted to expand as technology decreases

illegal access to electronic record systems. The Fair Credit the barriers for nonadopters and advances capabilities for

Reporting Act (1970) covers credit reporting agencies' col- current users, such as video and voice support. However,

lection, storage, use, and transmission of credit and financial only a modest number of people accessing the Internet are

information (Jones 1991). The Privacy Act (1974) extends actually purchasing goods or services through a Web-based

these restrictions to government agencies, and the Cable transaction. When asked why they do not, consumers report

a fear that companies will misuse personal information.

Along with some shopping, users increasingly access the

IThe various amendments deal with several aspects of privacy: First,

freedom to teach and give information; Third, protection of one's home;

Internet because of its "decentralized, open and interactive

Fourth, protection of the security of one's person, home, papers, and nature" (Center for Democracy and Technology 1999).

effects; Fifth, protection against self-incrimination; Ninth, rights shall not People can create communities, communicate ideas, engage

be construed to deny or disparage others retained by people; and in commerce, and search for information with unprece-

Fourteenth, the due process clause and concept of liberty (DeCew 1997, pp.

dented freedom and ease. These factors bring a downside for

22-23).

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 9

Table 1. U.S. Federal Regulation on Privacy

Act Year Description

Fair Credit Reporting Act 1970

Privacy Act 1974 Governmen

irrelevant to a lawful purp

Right to Financial Privacy Act 197

Electronic Transfer Funds Act 198

Privacy Protection Act 1980 Gove

Cable Communications Act 1984 C

tion without consent.

Family Education and Privacy

Right Act 1984 Government o

gathered by agencies or ed

Computer Security Act 1987 All

computers.

Electronic Communications

Privacy Act 1988 Prohibits telephone, telegraph, and other communications services from releasing the

contents of messages they transmit (only the recipient of the message can be identified).

Video Privacy Protection Act 1988 Video rental companies may not disclose choices customers make or other personal

information without consent.

Computer Matching and Privacy

Protection Act 1988 Allows governmental officials to increase the amount of information they gather if the

safeguards against information disclosure also increase.

Telephone Consumer Protection

Act 1991 Prohibits telemarketers from using automatically dialing telephone calls or facsimile

machines to sell a product without obtaining consent first.

Drivers' Privacy Protection Act 1993 Places restrictions on state government agencies and their ability to sell driver's lice

records.

Children's Online Privacy

Protection Act 1998 Sets rules for online collection of information from children.

users. Because their activities are conducted electronically,

DoubleClick, a developer of Internet software, has dev

a tool

consumers leave a trail of information that includes notthat

onlyextends the reach of these cookies and enables

purchasing information but also data pertaining advertisers

to their to follow the behavior of users from their origi-

interests and activities, which allow online marketers

nal Webthe

sites to others (Quick 1998).

opportunity to develop profiles of individual users.

Overview

Marketers employ a variety of online collection tech- of Online Privacy Regulation

niques, including mining e-mail addresses from list servers,

These increasingly sophisticated data collection methods

chat rooms, and news groups. A particular advantage of the

have raised concerns about consumer privacy, and consider-

Internet, however, is its ability to collect real-time behav-

able interest has emerged in developing some type of regu-

ioral data, which are accessed through the use of cookies.2

latory structure to ensure privacy on the Internet. Although

This collection method, called "profiling" (see the subse-

several groups are involved in this process, the Federal

quent discussion), updates a consumer's profile after every

Trade Commission (FTC) has currently taken the lead in

Web site visit with information such as the home pages that

developing standards of compliance for companies market-

were visited, the information that was downloaded, the type

ing on the Internet. The commission prepared a major report

of browser that was used, and the Internet addresses of the

to Congress in 1998 titled Privacy Online. In late 1999, the

sites that referred consumers to a particular Web site (FTC

FTC and the Commerce Department convened a workshop

1998; Mahurin 1997). Even more powerful software now

on the topic of online profiling with representatives from

can follow consumers and collect off-site data. For example,

Internet advertising and data collection firms, academics,

and privacy advocates.3 The primary reservation expressed

2Cookies are text files that are saved in a user's browser's directory or

folder and stored in random-access memory while that browser is running.

When visiting a Web site, a user is assigned a unique identifier, that is, a 3Online profiles of consumers are created through the compilation of

cookie (not the actual identity of the consumer), which will identify that their preferences and interests; these profiles are then used to develop

user in subsequent visits. advertisements targeted to these consumers on subsequent Web site visits.

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 Consumer Online Privacy

by the participants was the potential for consumer privacy

Figure 1. Control and Knowledge of Online Surfing and

Purchasing Activities

violations. The FTC chairman suggested that the issue is

troubling and warrants further examination (Guidera 1999).

One overriding concern is defining the concept of per-

Consumer Control

sonal information. A general definition, "data not otherwise

No Yes available via public sources" (Beatty 1996, p. B l), is

thought to be too broad, because it would exempt public

Surfing Surfing records such as home and car ownership and allow for the

access, use, and dissemination of that information by third

*Movements tracked *Technology solu-

parties. In its report to Congress, the FTC delineated per-

by software. tions, consumer can

*Consumer no longer dismantle tracking sonal information more specifically as (1) personal identify-

owns information. software. ing information, such as a consumer's name, postal address,

*General control or e-mail address, and (2) aggregate, nonidentifying infor-

Purchasing maintained. mation used for purposes such as market analysis or in con-

No junction with personal identifying information to create

*Use credit card, no

Purchasing detailed personal profiles of consumers, such as demo-

privacy statement.

*Consumer no longer *Use cash (not feasi- graphic and preference information (FTC 1998).

owns information. ble online), technol- These definitions do not adequately characterize consumer

ogy. information.4 Therefore, instead of defining personal infor-

*General control mation as the opposite of public space or as the sum of iden-

maintained.

Consumer tifying and nonidentifying information, our conception of

Knowledge consumer information encompasses both public and private

Surfing Surfing information (see Figure 2). Thus, personal information

includes

*Able to access pri- *Able to access pri-both public (e.g., a drivers license, mortgage infor-

mation) and private (e.g., income) data. The dotted line

vacy statement, no vacy statements,

opt-in and opt-out opt-in and opt-out

allows for the shifting of personal information from private to

options, no technol- options, technology

public; the public portion of personal information is thought

ogy solutions. solutions. to be growing as the Internet increases the ease with which

*Consumer no longer *Consumer owns

consumer information can be gathered and disseminated.

owns information. information.

Who bears the responsibility of ensuring consumer privacy

is a second concern. In debate is whether there should be indus-

Yes Purchasing Purchasing

try self-regulation, technology-based solutions, consumer and

*Have to use credit *Able to access pri-business education, and/or government regulation (FTC 1998).

card. vacy statement with Currently, the FTC endorses industry self-regulation. To

*Privacy statement, opt-out option if

ensure success, the FTC has developed five fair information

no opt-out. using credit card,

practice principles that would protect consumers in the collec-

*Consumer no longer ability to pay cash

tion, use, and dissemination of their information:

owns information, with opt-in option.

*Consumer owns

information. 4This section benefited from a faculty seminar at the University of Notre

Dame, in which several participants gave helpful comments regarding pub-

lic versus private information.

Figure 2. Consumers' Personal Information Model

1980 1990 2000

Public Information Private Information

Notes: The dotted lines represent the transition of a greater portion of consumers

thought to be the result of an increased use of databases (early 1990s) and th

information.

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 11

1. Notice/awareness: covers the disclosure of information

businesses prac-

(Miller 1998). First, consumers might get a false

tices, including a comprehensive statement sense of privacy ifuse,

of information laws were passed that could not be

that is, information storage, manipulation,enforced

and dissemination;

because of the dynamic nature of Web site creation

2. Choice/consent: includes both opt-out and opt-in

(James options

1998). Second,and

government regulation would inter-

allows consumers the choice to trade information

fere withfor benefits,

the flow of consumer information that enables

depending on the value consumers place on the benefits;

companies to provide products and services that cater to the

3. Access/participation: allows for confirmation of the

needs and wantsaccuracy

of their customers, which would result in

of information; necessary when information is aggregated

decreased consumer choice and diminished competition.

from multiple sources;

Furthermore, mandatory opt-in and restrictions on the sale

4. Integrity/security: controls for theft or tampering; and

of customer information could create barriers to entry that

5. Enforcement/redress: provides a mechanism to ensure

would favor com-

older, more established companies that have

pliance by participating companies; this mechanism

years of collecting is an

information and developing databases

important credibility cue for online companies but is

(Brandt 1998). Newer companies would be at a disadvan-

extremely difficult to accomplish effectively (FTC 1998).

tage if they were not allowed to purchase information.

Of these principles, the issue of disclosure

Third, consumers(under

would lose their right to choose their

notice/awareness) is central to privacy and desired level of whether

covers privacy. Recall that some consumers wel-

or not consumers are informed of collection methods and come the collection of their information and willingly sell it

information use. The current self-regulatory environment if they are provided the right incentives. Finally, govern-

suggests that each company is responsible to develop its ment intervention might violate free speech. The informa-

own disclosure statement, with varying levels of notice,tion used in the creation of databases is similar to gossip

choice, access, and security. Thus, individual firms decide (Singleton 1998), which is protected under the First

the degree of information collection and use along with the Amendment, and might be less harmful because the infor-

type and structure of disclosure. This lack of regulatory mation in databases is likely more accurate, less personal,

standardization suggests that the responsibility to assess theand so forth.

privacy practices of Web site operators falls to the consumer Self-regulation advocates argue that consumer informa-

and that there is limited enforcement and redress. tion is the foundation on which businesses can succeed and

allows them to develop markets based on their customers.

Approaches to Internet Regulation Furthermore, these advocates contend that the collection

and use of this information harms consumers only by being

As discussed previously, legal protection for consumer pri-

an annoyance, which is not considered reason enough to call

vacy historically has focused on industries thought to be

for stricter regulatory measures. A breakthrough in the

particularly egregious in the collection and use of personal

self-regulatory arena occurred with the announcement by

information. Unlike these more static industries, however,

IBM in March 1999 that the company would pull its Internet

in which regulatory actions are reasonably easy to control,

advertising from any Web site in the United States or

the Internet is experiencing rapid growth, which limits gov-

Canada that did not post clear privacy policies within 60

ernment enforcement. Even the FTC questions the scope

days (Auerbach 1999). Only 30% of the 800 sites on which

and extent of the government's powers to pursue regulatory

IBM advertised at that time made such disclosures.

responsibility. The difficulty in regulating online privacy is

Seeing the potential for consumer confusion regarding the

a central issue debated among self-regulators, government

effectiveness of self-regulation, a new vehicle (third-party

regulators, and privacy advocates.

intervention) has emerged. Third-party entities have formed

Industry Self-Regulation to provide legitimacy and trustworthiness to Web sites

through seals of approval that are designed to confirm ade-

Several arguments have been advanced that government

quate privacy compliance (see Table 2). Three such entities

involvement would hurt rather than help consumers and

are TRUSTe, the Online Privacy Alliance, and the Council

Table 2. Third-Party Entities

Goals Limitations

TRUSTe Provides guarantee of privacy protection: 1. Limited industry compliance.

1. Gives a seal of trust to Web sites that submit to 2. Critics suggest that guide

application process. further in protecting privacy.

2. Acts as a clearinghouse for privacy violation

reports.

3. Provides a children's privacy seal program.

1. Voluntary nature of member com-

BBBOnline Provides seal of approval to Web sites that adequately pany compliance.

perform through a self-assessment and pay a fee. 2. Enforcement.

1. Voluntary nature of member com-

Alliance for Privacy Publishes guidelines for member companies to follow pany compliance.

in the collection and dissemination of information. 2. Enforcement.

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 Consumer Online Privacy

member

of Better Business Bureaus, countries

Inc. (Harbert 1998; Heckman TRUSTe

(BBBOnline). 1999; Messmer

1998). Thissupported

an industry-launched initiative directive requires adequate

by such privacy protection

compa-

from the countries

nies as AT&T, America Online, Netscape, Oracle, of businesses exporting personal

Wiredinfor-

mation from these 15 countries.

and Tandem Computers (Bayne 1998; Wientzen and Smith The upshot of the directive

is that

1998). Similarly, the Online U.S. companies

Privacy such as hotels,

Alliance is airlines, and banks

a coalition

of 85 marketers, technologydoing business in Europe

firms, and cannot transfer information

associations, from

includ

Europe to America

ing Time Warner, Walt Disney, the United States (Leibowitz 1999;

Online, and Swire and

IBM.

The BBBOnline offers a distinct seal

Litan 1998). for destination

Accordingly, sites with countries adverti

must have

privacy

ing for children and will take protectionsagainst

action the EU deems companies

adequate, which include

tha

do not comply (Ohlson 1999). two components: a national privacy law covering both the

The effectiveness of thesepublic and private sectors and

organizations hasenforcement

been capabilities

ques-

through national regulatory agencies.

tioned. Of concern is the scope of their enforcement program

The EU

and compliance; that is, do they directive, which

provide the takes a more consumer-oriented

muscle required

focus than U.S.

set up an environment that benefits companies do, is structured

consumers given the in when and

enor

mity of the Internet? Issues how a company can

include collect and use consumer

membership information

numbers

requirements, and compliance,(Harbert

as1998).

well First, as

a company

the should have a legitimate

long-term mi

sions of these organizations and(Wigfield

clearly defined purpose to collect For

1999b). information. Second,

example

that purpose must

TRUSTe is revising its licensing be disclosed to the person

agreements, from whomma

which the

change consumers' protection company is collecting

levels. Someinformation.

criticsThird, permission

argueto tha use

TRUSTe flunked its first big information

test when is specific

theto theorganization

original purpose. Fourth, the

faile

company can keep the

to reprimand Microsoft (a $100,000 data only to satisfy

corporate that reason; if the

partner) fo

company wants

putting an identifier on Windows 98 to use

(New the information

Yorkfor another purpose,

Times 1999

Although the effectiveness ofit needs

these to initiate

third a new information

parties hascollection

been and que

use

process. As it stands

tioned, the FTC recently has testified that now,sufficient

only a few U.S. companies

progress(e.g.,

Citicorp, American

being made toward self-regulation, Express; Leibowitz

postponing 1999) could

further meet

gover

these criteria,

mental action at this time (FTC 1999; and adoption

Heckmanof these standards

1999). may have a

chilling effect on Internet marketing.

U.S. Government's Position Enforcement for the EU's directive has been delayed for

The Clinton administration and the FTC advocate two reasons (Heckman 1999). First, only about half of EU

self-regulation of commercial collection and use of member

con- countries have passed laws enforcing the directive.

sumer information on the Internet (FTC 1998; Harmon Second, the EU currently is negotiating with the U.S.

1998b; Messmer 1998). The administration believes thatDepartment

the of Commerce on Safe Harbor provisions for

U.S.

flexibility self-regulation gives to businesses is important to companies.5 These negotiations will eventually result

the success of Internet commerce. In a 1999 report to the in the formulation of a Safe Harbor program acceptable to

Subcommittee on Communications, the FTC stated European that officials. Although both groups agree on the prin-

"self-regulation is the least intrusive and most efficient ciples (the same as FTC fair information principles), includ-

means to ensure fair information practices online, givening

the recognition that U.S. firms will be limited in selling

databases, the designated enforcement body to regulate U.S.

rapidly evolving nature of the Internet and computer tech-

nology" (FTC 1999, p. 4). As discussed previously, itfirms

will continues to be a major obstacle. When implemented,

continue to monitor the progress of self-regulation because Harbor programs will guarantee that those companies

Safe

of challenges still facing the industry (DIRECT Newslineadmitted into the program can be assumed to be in compli-

ance and will be allowed to compete in Europe.

1999; Wigfield 1999a). These challenges include educating

those companies that underestimate the need for privacy and

Privacy Advocates' Position

creating incentives for greater implementation, as well as

educating consumers about privacy protection (FTC 1999). primary concerns dominate privacy advocates' argu-

Two

Although the government's position appears favorable ment

to against self-regulation: the voluntary nature of indus-

try compliance and the degree of consumer knowledge and

self-regulation advocates, they continue to lobby for a com-

pletely hands-off position. They point out that thoughcontrol

the of information collection and use (Rotenberg 1998).

The voluntary nature of compliance is especially important

FTC may favor self-regulation, history indicates otherwise.

One example cited is former FTC commissioner Christine to privacy advocates, who argue that businesses do not

always

Varney's position that voluntary systems of standards or rat- compete with consumers' best interests in mind; it is

more

ings, whether for privacy or content, should be backed up likely that the degree to which a business complies is

with strong government enforcement against misstatement based more on its own profit objectives. It is argued further

as either deception or fraud (Singleton 1998). that even firms that make a commitment to privacy may at

times compromise privacy standards if it is competitively

The European Union's Privacy Initiatives necessary. Privacy advocates point to low compliance rates

Of great interest in the privacy debate are the recent actions

taken by the European Union (EU), which has just tightened 5Safe Harbor programs will be sets of rules created by industry organi-

its privacy laws. It passed a treaty-like directive in 1995,

zations for their members and designed to comply with various FTC regu-

which should have gone into effect October 24, 1998,

lations; if a company is admitted to a Safe Harbor program, it is assumed

intending to harmonize privacy protection in all of to be

its 15 in compliance.

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 13

among new members of the Direct Marketing ilar disregard is sometimes expressed by onli

Association

inarguing

and question consumers' ability to opt-out, words and

thatactions.

lit- For example, Sun Micro

executive

tle prevents members or nonmembers from accessing theofficer Scott McNealy glibly stated

information contained in that database have (Jones 1991;

zero privacy. Get over it" (Baig, Stepane

Rotenberg 1998). 1999, p. 84).

Conflicting data over compliance to FTC regulatory stan-

dards exist. The FTC reports low compliance:Unresolved

Of the Issues

1400

sites it has analyzed, 92% of the commercial sites collect

What is known about privacy on the Internet is that consumers

personal data, yet only 14% provide notice of information

appear concerned about threats to their online privacy, and

collection practices, the most basic of its privacy principles

many companies have been slow to respond. At issue is the

(FTC 1998). Another survey finds that only half of all Web

perceived ownership of consumer information. Companies'

sites surveyed provide information (and only 10% meet

actions suggest that the information, either acquired as part of

FTC standards) on collection and use practices. However, a

a transaction or purchased from other sources, belongs to

third study indicates 94% of the top 100 Web sites in com-

them. As discussed previously, research has shown a lack of

pliance with disclosure standards (Wigfield 1999a, b).

voluntary compliance to even the most basic of the FTC's

The Georgetown Internet Privacy Policy Survey (1999), a

Principles-the right of consumers to be given notice of an

recently conducted progress report to the FTC, finds that the

entity's privacy practices (FTC 1998). The absence of com-

majority of Web sites visited (93.4%) collect either personal

prehensive policies is particularly troubling, because con-

identifying or demographic information from consumers. At

sumers do not always understand that complete disclosure has

least one type of privacy disclosure statement (either a pri-

not been included in a privacy statement. This minimalist

vacy policy notice or an information practice statement) is

approach can be seen in the DMA's privacy statement, which

posted on 65.9% of the sample Web sites. The majority of

outlines its practices forjust one subset of information collec-

Web sites that collect consumer information and post a pri-

tion and use. A Web site's collection of information through

vacy disclosure include at least one survey

the item for notice

use of cookies is in obvious violation of the notice/aware-

(89.8%), more than half include a survey item for choice

ness principle, because the majority of consumers do not

(61.9%), and less than half include a survey item for secu-

know the "nature of the data collected and the means by which

rity (45.8%) and contact information (48.7%).

it is collected" (FTC 1998, p. 8). Furthermore, consumers are

Even with the disclosure of privacy statements, confusion

not given the option to refuse to participate, because it is their

can arise from the vague and often ambiguous nature of some

real-time behavior that is being collected.

of them. For example, the Direct Marketing Association's

A consumer's inability to decide whether to proceed sug-

privacy statement on its Web site does not address its policy

gests an asymmetrical relationship in which the marketer

for collecting tracking information and is unclear about the

benefits at a cost to the consumer, though some might argue

use of this information. Its policy states, "the information we

that consumers will benefit through targeted products and

collect is used to improve the content of our Web page and to

services in the long run. Thus, what they do not know will not

contact customers for marketing purposes," though "market-

hurt them in the short run. This asymmetrical relationship is

ing purposes" is not further explained.

further exacerbated by the lack of a mutually beneficial com-

Consumers' lack of knowledge and control of what happens

pensation structure. Traditional information collection meth-

to their personal information is a second concern. The dynamic

ods provide a payment, an incentive to entice respondents to

nature of information collection and manipulation decreases

participate, and allow those who do not want to participate to

consumers' ability to keep track of their information as it is

drop out. Similar is the process of engaging in a transaction

collected and aggregated from multiple sources to create con-

with a marketer. Consumers participate only with marketers

sumer profiles. Although some of these data are provided by

they perceive as providing value. Thus, in both these scenar-

consumers (e.g., demographic information), other information

ios, the consumer enters into a transaction in the short run,

is collected without consumer knowledge, such as tracking

and possibly the long run, if the arrangement is mutually ben-

information obtained through Web site surfing behavior. Thus,

eficial. We suggest that it is the consumer's knowledgeable

consumers control only a portion of their own profiles.

participation in the marketing activity that separates tradi-

Privacy advocates warn that consumers' negative

tional percep-

information collection methods from those used online.

tions resulting from this lack of control may act as a deter-

Two of these online activities warrant further discussion.

rent to the commercial success of the Internet.

The first A study

issue involvescon-

the collection and use of consumers'

ducted over the Internet by Georgia Tech finds that privacy

information. Collecting aggregate data on consumer Web

is the most important issue facing the Internet (Kantor

site surfing behavior, in isolation, is of negligible harm to

1998). A BusinessWeek survey finds that people who do not

those being tracked because of the seemingly innocuous

use the Internet cite privacy of their personal information as

nature of the use of the information-for example, to design

the primary reason (FTC 1998; Oberndorf 1998; Rotenberg

Web sites better or provide advertisements targeted more

1998). This lack of confidence parallels consumers' percep-

accurately at users. Even the collection of transactional data

tions about the direct marketing industry. A few years ago,

is thought to be beneficial-for example, when revisiting

the editorial director of Target Marketing, citing a "lack of

Amazon.com, a visitor gets a suggested list of books based

respect on the part of direct marketers" for consumers,

on previous purchases. Justification of these activities

pleaded with marketers to consider the effect of their actions

comes largely from the use of a utilitarian argument: The

in the long run, in terms of both consumer disillusionment

use of this information in the context of marketing provides

and possible government intervention (Jones 1991). A sim-

better goods and services to the community as a whole and

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 Consumer Online Privacy

younger from Web sites unless

thus justifies the minor inconveniences that the children

some obtainmay

verifi- suf-

able permission from their parents (Heckman 1998),

fer (Foxman and Kilcoyne 1993).

questionsis

The question is not about what arisebeing

about its ability to protect and about

collected or whateven

is tothe

how the data are collected but be protected. Unclear is the definition

knowledge and of "informa-

control of

the participants in those activities. America's

tion"-Does it include information largest

provided by children,

or does

retailer, Wal-Mart, which has it also include the collection

a customer database and use of second

all their

only to the federal government, personal and behavioral data? Also

continuously questioned infor-

collects is the dif-

mation on its customers' purchasing behavior

ficulty of verifying the (Nelson

child's age and parental consent,

1998). The difference is that asconsumers

well as the FTC's limited

stay ability

in the to enforce

aggre- these

gate at Wal-Mart, and individual requirements.

consumers can self-select

The final rules

(i.e., opt in) data collection activities at for COPPA

the were outlined by

checkout the FTC in

counter

if the offered incentive is of sufficient

October value.

1999, which further Thus,

strengthened con-

the online privacy

sumers maintain control. of children (Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule

A second issue, then, is value 1999).

toThese

the rules, effective April 21,Although

consumer. 2000, require opera-

some online activities require tors ofopting in children

Web sites targeting (e.g., consumers

under 13 years of age to

knowingly trade away information (1) post prominentforlinks onconvenience and

their sites to notices outlining

selection when they provide the collection,

credit use, and/or

card disclosure practices

numbers), otherinvolving

trade-offs are not so obvious. Consumers have limited personal information; (2) notify parents about collection

knowledge, for example, when their surfing behavior is col- practices and obtain their consent before information collec-

lected and limited control when these surfing data are linkedtion, use, and/or disclosure; (3) cease the practice of linking

to transactional and demographic data. Several questions children's participation in online activities to the collection

arise. What is the value derived by consumers in these types of additional personal information; (4) allow parents the

of activities? Is the value limited or is there some value opportunity to review information on their children, delete

gained from consumers' information being collected and this information from databases if desired, and prohibit fur-

used? If there is some value-for example, better Web ther collection of information; and (5) formulate procedures

sites-is the value commensurate with that obtained by the to protect the confidentiality, security, and integrity of per-

marketer that collects and uses that information? If no valuesonal information.

is obtained from the activity-that is, at the minimum, a dis-

count or a coupon-is the marketer taking equity from the Ethical Theories and Online Privacy

relationship, and at what point will the consumer become

The importance of marketer responsibility in a transaction

frustrated enough to decide not to participate? Information

is not only to complete this particular exchange but also

obtained by marketers without providing equivalent value to

to ensure future exchanges that will build into a relation-

customers and the subsequent feeling of a loss of control by

ship. Cespedes and Smith (1993, p. 9) state that compa-

these customers suggest a future point at which consumers

nies cannot afford to waste resources on marketing activ-

may demand retribution, through either government action

ities that "annoy or alienate potential customers."

or boycott.

Consumers continue to visit a particular business because

of the perception of trust, that is, that the company has

The Special Case of Children their best interests in mind when providing a product

The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA; 112 and/or service. We discuss several ethical theories as

Stat. 2681) was passed in October 1998 because of concerns vehicles to strengthen the bond of trust between market

regarding online marketing practices aimed at children.6 and customer.

FTC research in June 1998 found low industry compliance Social contract theory suggests that a reciprocal rela-

with its Fair Practice Principles, such as the inclusion of tionship exists among those involved in an exchange

information practice statements (e.g., "Kids, get your par- (Dunfee, Smith, and Ross 1999). At a higher societal

ents' permission before you give out information online") level, a social contract might involve the advantages

and privacy notices as well as parental notification. This offered by a firm "to society-its customers and employ-

report also indicated that information such as age/birth date, ees-in exchange for the right to exist and even prosper"

sex, hobbies, interests, and hardware/software ownership (Dunfee, Smith, and Ross 1999, p. 17). This theory is par-

was collected more from children than from adults. A par- ticularly important to marketing, in which transactions are

ticular concern with these findings is the limited cognitive based on each party believing that value has been

abilities of children, which suggests that they may be more obtained. When applied to direct marketing, social con-

motivated by the incentives intended to get their information tracts are formed when consumers provide information to

(e.g., postcards, freebies) than by the information provided marketers for the benefit of receiving targeted offers

in the privacy statement. (Milne and Gordon 1993). A social contract is initiated,

Although COPPA prohibits the collection of personally therefore, when there are expectations of social norms

identifiable information for children 13 years of age and (i.e., generally understood obligations) that govern the

behavior of those involved.

Social contract theory applies to the Internet for the same

6The COPPA should not be confused with the Child Online Protection reasons suggested for direct marketing: Consumers opt in to

Act that makes commercial Web sites criminally liable if minors have a particular activity from which they perceive future infor-

access to obscene or indecent material (Raysman and Brown 1998). mation streams will be of value. The transaction occurs

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 15

ment

when a consumer provides information toover

anthe degree of privacy accorded, all of which

organization

and the marketer in turn offers an incentive tothe

will affect the consumer;

behavior of both stakeholders and govern-

both of these actions are initiated after an evaluation of the ment. Thus, fairness dealing with the trade-offs among

specifics of that particular contract. Implied here is the pres- these often conflicting rights will be important to Internet

ence of two parties in the transaction in which information success.

is exchanged for the promise of some benefit, whether pre- Virtue ethics is another ethical theory releva

sent or future. One generally understood obligation accruing consumer privacy. Although virtue ethics pos

from entering into this social contract is that both parties characteristics (Murphy 1999), the one most r

understand the risks involved as well as the returns. Thus, online marketers is the "ethic of the mean," whi

the consumer, in conducting a cost-benefit analysis, enters balance is an objective in any relationship--ex

into an exchange that provides positively perceived benefits, avoided. Aristotle, one of the earliest propone

which may not be unduly affected by privacy concerns. ethics, indicated that deception is the deficien

Consumers, instead of following an absolute philosophy of whereas boastfulness represents the excess of t

"I want to be left alone," as privacy advocates contend, ous position is one that strives for middle gr

might just want "protection against unwarranted uses of per- scribed by social contract and stakeholder the

sonal information with minimal damage" (Cespedes and keters, public policymakers, and consumers m

Smith 1993, p. 8). this delicate balance among marketing goals, c

Duty-based theory includes three categories of obliga- vacy, and the public good. Privacy advocat

tions. First, the duty of fidelity (Laczniak and Murphy 1993) companies are taking extreme and adversar

requires companies to tell the truth and redress wrongful without recognizing the importance of balance

acts without delay. It enables companies to build a bond tive steps have been made with COPPA, the IB

with their customers, who then come to associate these com- ing initiative, and third-party interventions.

panies with ethical behavior, which most likely results in In the international arena, applying virtu

positive word of mouth and repeat business. Much of the online privacy is difficult. The EU has take

previous discussion regarding online regulatory standards stance than the United States in protecting co

involves the question of how much a company must disclose vacy; one commentator indicated that the U

of its practices. The recent meeting regarding online profil- should "consider importing Europe's more

ing sponsored by the FTC appears to be an indicator that balanced conception of privacy" (Kuttner

companies in the industry are now accepting this duty. Yet a compromise must be reached betwee

Second, the duty of beneficence is the obligation to do the United States if there are to be viable rul

good. In the context of online marketing, companies would commerce.

not track the behavior of their customers because of their The power-responsibility equilibrium mod

duty to do right by these customers. This duty might also and Murphy 1993) might shed some light on th

include providing a complete disclosure of information col- for the participants in an online marketing

lection and use and to provide an opt-in rather than an opt- Power and responsibility should be in eq

out system. In this system, marketers would track only those whichever partner in a relationship has more p

online consumers who were willing to participate. the responsibility to ensure an environment of tr

A third duty involves that of nonmaleficence, the duty not fidence. According to the model, if a compa

to injure others. This duty covers the FTC's Fair strategy of greater power and less responsibil

Information Practice Principle of integrity/security. By benefit in the short run (though the consume

instituting measures that maintain the security and integrity power will not benefit); however, that compan

of consumers' information, marketers ensure that these con- power in the long run (e.g., increased governm

sumers are safe from harm to their financial state or even to tion). In contrast, a company in balance with i

their personal reputations, thus mitigating consumers' reluc- should benefit both in the short run and the lon

tance to participate in Internet activities. large companies require Web sites to post a pr

Stakeholder theory postulates that those who have an ment, this action represents a good example o

interest in or are affected by an organization have a stake with greater power accepting its responsibility.

in its decisions (Donaldson and Preston 1995; Goodpaster

1991). The rights of stakeholders regarding organizational Future Policy Directions

privacy have been examined by Stone and Stone-Romero

Although it seems premature at this point to off

(1998). In the context of online marketing, the stakehold-

directions regarding consumer online privacy,

ers include the organization itself, as well as consumers,

marketers and public policy officials should co

privacy advocates, self-regulation advocates, the govern-

eral alternative possibilities. Figure 3 depicts e

ment, and, finally, cyber (as opposed to any national) soci-

policy proposals examined here on an ethical r

ety, whose norms govern expectations of the right to pri-

continuum. The various ethical theories disc

vacy. For the primary stakeholders, customers value some

degree of privacy and expect trust in the transaction,

whereas some companies place the greatest value on

short-term profit generation. The rights of the secondary 7Although Microsoft has come under criticism in the past

stakeholders also conflict with the needs of advocacy emphasis on privacy matters, the company has assumed gr

bility recently. In June 1999, it put in place a policy simil

groups, the government, and societal attitudes in disagree-

has included its privacy activities on the company Web pag

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 Consumer Online Privacy

are willing to trade off some of their privacy rights. For

Figure 3. Ethical Responsibility Continuum

example, several major auto manufacturers are experiment-

ing with online market research, which asks in-depth ques-

Business Orientation --- Societal Orientation

tions of potential consumers about both their lifestyles and

Corporate Corporate U.S. EU their demographics as well as past purchasing patterns. In

Business Ethical Public Public return, respondents are offered vouchers for several hundred

Theories Policy Policy Policy Policy dollars to be used on any of the firms' products. This open

Managerial exchange of information for substantial monetary compen-

egoisma X sation begins to mitigate some of the ethical and policy con-

Utilitarianismb X X cerns examined in this article. Amazon.com's attempt to

Stakeholder theoryc X X X alleviate fears about sharing credit card and personal infor-

Virtue ethicsd X X

mation over the Internet by adding a "guarantee" button to

Integrative social

its home page (which lists the firm's security assurances and

contracts theorye X X

an option to telephone in the last five digits of the con-

Duty-based

theoriesf X X sumer's credit card) is an example of concern with the

Power and integrity/security of consumer information (Zeller et al.

responsibilityg X X X X 1999).

Corporate Ethical Policy

aManagerial egoism: Executives take steps that most efficiently advance

In the

the exclusive self-interest of themselves orspirit of the ethic

their firm.of the The

mean and

Xtheissubstantial

placed

self-regulatory

under corporate business policy because the initiatives already in

sole motivation isplace,

to some specific

further

the firm; trade-off incentives are offered for the purpose of obtaining con-

corporate actions seem necessary to protect consumer pri-

sumer information that is viewed as the property of that company.

bUtilitarianism: Corporate conduct is proper if a decision results in the

vacy in an online environment. Although the following

greatest good for the greatest number ofproposals

people. have Self-regulatory

not been applied specifically to this con-

advocates

maintain that consumers are not hurt by text, the approach follows

corporations' the position advocated

collection and use by

of personal information but are annoyed Phelps,

(the Nowak,

costsand areFerrell

low);(1999,furthermore,

p. 43), who state that

the information allows for a wide assortment of product choice (benefits

marketers should adopt a proactive stance in alleviating

are great).

cStakeholder theory: Organizations affect and are affected by several stake-

consumer concerns about privacy. Possible corporate poli-

holder groups. On the continuum, this theory ranges from corporate busi- cies are

ness policy, because of the effect of corporate actions on consumers (e.g.,

incentive trade-offs), to corporate ethical policy, because of the positive *Privacy statement: Every Web marketer should have an explicit

influence of privacy statements and privacy audits on many stakeholders, policy statement on privacy. Ideally, it should not be a legalis-

to public policy, because government and society are seen as important tic document but one that could be easily understood by a

stakeholders. layperson. Similar to other ethics statements, the privacy state-

dVirtue ethics: Balance in the relationship between the online marketer and ment should be widely communicated, regularly revised, and

the consumer should be achieved for the market system to work effec- even promoted (Murphy 1998).

tively. Thus, corporations and public policymakers need to move toward

*Privacy audit: Companies should go to greater lengths in study-

the ethic of the mean in the privacy debate.

ing the methods they use to collect, store, and disseminate con-

elntegrative social contracts theory: This theory presupposes that the

Internet community precedes the development of rules of conduct, public sumer information. In some cases, such an audit will probably

policy, or "microsocial contracts." Corporate ethical policies assume that lead to the conclusion that consumers should be informed if the

the corporation's participation in the development of social rules would firm plans to sell their information to third parties.

necessitate transparent ethical practices. *Privacy technology: New technologies that enhance privacy

'Duty-based theories: The normative nature of these theories means that

rather than weaken it should be adopted if possible. The leading

they are used by policymakers in determining the company's absolute

marketers and advertisers on the Web could set a higher standard

duties to consumers. If the duties of fidelity, beneficence, and nonmalefi-

cence are violated in the course of Internet marketing, greater participation

than currently exists. Some of these new technologies include

by regulatory agencies in the United States and Europe can be expected. software that ensures anonymity on the Internet, encryption of

gPower and responsibility equilibrium: Corporate power and responsibility messages and transactions, and audit trails that determine who

must be approximately equal for Internet marketers to be effective; in the accessed a file and thus deter unauthorized queries (Etzioni 1999).

long run, those who do not use power in a way that society considers

responsible will lose it. This covers the entire continuum, because it incor-

porates organizational stakeholders and includes the multiple public pol- Public Policy

icy perspectives.

The policy arena for online privacy is a global one; interna-

tional regulation, rather than just U.S.-based public policy,

is likely the long-term answer. Therefore, future initiatives

ously are arrayed and explained as to their relevance to should strive for input across nations. The fundamental dis-

online privacy questions. agreement between Americans (who generally distrust gov-

ernment) and Europeans (who usually place little faith in

Corporate Business Policy self-regulation) means that the needed compromise between

Before examining broader ethical and public policy impli- the EU Privacy Policy and the United States continues to be

cations, we briefly outline the progress companies have assessed. However, the realities of a new century are that at

made toward increased online privacy. It appears that more least some information will be collected about consumers

business firms are putting in place mechanisms that protect and electronically stored. The long-standing goals for a fair

consumer online privacy or offer benefits to consumers who marketplace and a level playing field suggest that policy-

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 17

makers should strive for more universal Internet.

policies.Only

Tothrough

accom- massive growth in purchasing from

companies are

plish these goals, the following policy proposals on the Internet, and not just surfing, will the rev-

offered:

enue be produced to compensate for the high costs compa-

*Individual privacy consent: One of the major stipulations in the

nies need to bear to be competitive and to build brand

EU directive is the opportunity for consumers to provide their

consent for the use of personal information. ThisThe

equity. arguments

appears in support of self-regulation suggest

to be

a short-term

unworkable in our computerized age. However, approach:on

the details Companies are looking for the means

to market

how to move beyond the case-by-case method to customers

to a more gener-in the present and may fail to see

alized consent without giving up privacy how their actions

represents affect their long-term success in this

a major

medium.

policy question. Both U.S. and EU policymakers Public

need to policymakers

strive in the United States and

for an ethic-of-the-mean resolution to this difficult

Europe needissue.

to agree on common privacy standards, even if

it is the

*Innovative self-regulation: The FTC is seeking only input

at a minimal

of alllevel.

major privacy groups in developing a workable privacy

This article policy

proposes that ethical standards, not just policy

for the Internet. The opt-out and opt-in issue continues

statements, tobebe

should a

adopted in confronting online privacy

policy concern. Web sites could be required to seek

concerns. thepositive

Several con- recent developments, including

sumer's agreement instead of assuming that silence means con-

increasing industry and government dialogue and the grow-

sent. At the very least, the FTC must ensure that any opt-out

ing use and enforcement of privacy standards, signal an

awareness campaign is heavily publicized (Green 1999).

enlightened emphasis on privacy. The proactive business

*Limited new regulation: One area that apparently needs further

actions and policy initiatives outlined in the previous section

protection is medical privacy. No federal regulation prohibits

disclosure of such sensitive information as should be helpful

abortion, in answering this fundamental question:

cancer

What is the right

treatment, or mental illness (Etzioni 1999). This area seems tothing to do for the customer? Our aspira-

strike at the core of individual privacy andtions

has for consumer

become privacy suggest an integration of busi-

a con-

sumer (not just a medical) privacy concern. ness, ethical, and public policy standards to mitigate what

some believe to be an inevitable erosion of privacy.

Research Agenda

Academic researchers can inform the ethical and policy

Appendix

debate by systematic study of consumerIllustrations of Online Privacy Issues

privacy questions

facing business and government. These includeTrue story:the following:

recently, I followed a lead from MacUser mag-

azine to a web page

*Are the privacy statements currently adopted by industry effec-

for dealing with spam e-mailers. That

tive in dealing with consumer knowledgepage andsuggested that one

control of the first steps to take was to con-

ques-

tact services

tions? A content analysis of these statements that track people's e-mail addresses. With

by independent

judges could assess the ethical principlesgrowing horror, I connected

companies espouse page after page on the list and

and whether the statements increase the likelihood of

located myself in use

their by

databases. Some services listed far

consumer.

more than just names and e-mail address. My home address

and phone

*Which of the fair information principles proposed bynumber were accessible from the same record.

the FTC

are most central to consumers? A depth interview approach

Two services even had a facility to show a map of my

may lead to insights into which principles are neighborhood

the most andcentral

the location of my house in it. The wide-

concerns and which ones consumers may be willing to trade off

spread dispersal of information of this sort, without prior

under certain circumstances.

consent, is a serious invasion of privacy (Handler 1996).

*What trade-offs are online consumers willing to make for their

With a 98% compliance rate, our registered users provide

personal information, and do they perceive the compensation to

us with specific information about themselves, such as their

be fair? A large-scale survey could assess the perceived value of

age, income, gender and zip code. And because each and

one-on-one marketing in the context of a cost-benefit analysis.

every one of our users have verifiable e-mail addresses, we

*How do organizations' activities in collecting and using infor-

know their data [are] accurate-far more accurate than any

mation affect long-term relationships? Will customers forgive

marketers' short-term activities (e.g., loss of control, loss of pri- cookie-based counting. Plus, all of our user information is

vacy) in return for future rewards? A longitudinal study of con- warehoused in a sophisticated database, so the information

sumers participating in Internet loyalty programs might is stable, accessible and flexible. Depending on your needs,

uncover whether marketers' increasing demands for personal we customize user groups and adjust messages to specific

information are detrimental to long-term customer satisfaction. segments, using third-party data or additional user-supplied

*Can international privacy standards be developed for this information. So you can expand your targeting possibilities.

medium given vast cultural differences? A comparison study What's more, because they're New York Times on the Web

starting with U.S. and European consumers and then expanded subscribers, our users are affluent, influential and highly

to other countries might ascertain whether a set of universal engaged in our site (New York Times advertisement).

core privacy rights do exist. Such a project should assist policy-

America Online Inc. (AOL) recently announced it

makers in determining the levels of future regulatory action.

would drop its plan to sell subscriber phone numbers to its

business partners for telemarketing purposes. This action

Conclusion came after tremendous criticism from customers, privacy

groups and consumer leaders. According to a statement to

Marketers and public policymakers both have a vested inter-

its subscribers, AOL never planned to make its customers'

est in solving the online privacy dilemma. Increasing con-

telephone numbers available for rental to telemarketers.

sumers' confidence and trust in the privacy and security of

their information will fuel growth of e-commerce on the "The only calls we intended for you to receive would have

This content downloaded from

118.101.170.171 on Sat, 27 May 2023 17:48:37 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 Consumer Online Privacy

been from AOL and a limitedBeatty,

numberSally Goll (1996),

of "Consumer

quality Privacy on Internet Goes

controlled

AOL partners," according to the

Public," statement.

The Wall Street Journal, (February"However,

12), B I.

upon further reflection, we Bloom,

today Paul N.,decided

George R. Milne,

to and change

Robert Adler (1994),

our

"Avoiding

plans. We will not provide lists ofMisuse

our of New Information Technologies:

members' Legal and

telephone

numbers even to our partners. Societal

The Considerations,"

only Journalcalls of Marketing,

you might 58 (January),

98-110.

receive will be from us." Responding to the initial

announcement of the plan, consumers

Brandt, swamped

John R. (1998), "What Price Privacy?" IndustryAOL's

Week, 9

(May 4), and

toll-free number to complain 4. New York Attorney

General Dennis Vacco criticized the

Center for plan

Democracy during

and Technology an

(1999), Testimony inter-

of Deidre

view on CNBC. In addition, WallMulligan,Street

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science,with

responded and a

Transportation,

four percent drop in AOL's stock Subcommittee

price on Communications,

(Direct (July 27).

Marketing

1997, p. 6). Washington, DC: Center for Democracy and Technology.

Cespedes,

Intel Corp. last week decided to Frankmake V. and H. Jeff Smith (1993),

changes in"Database

a secu-

Marketing: New Rules

rity feature of its upcoming Pentium IIIforchip

Policy andafter

Practice," Sloan

privacy

Management

groups started a boycott of theReview,

chip(Summer), 7-22.

giant's products.

Children's Online Privacy Protection

Identification numbers that application vendors Rule: Issuancecould

of Final Rule use to

(1999), 64 Fed.

identify a processor and its users Reg.

would make the Internet

and electronic commerce more secure,

DeCew, Judith the

(1997), In Pursuit of Santa

Privacy: Law, Clara-

Ethics, and the

Rise of Technology.

based company said. But privacy advocates Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. that the

argued

identification numbers wouldDirecterode Internet

Marketing (1997), privacy

"AOL Bows to Criticism over Selling and

make it easier for companies Members'

to track users

Phone Numbers," for

60 (August), 6. marketing

purposes (Savage 1999, p. 83).

Direct Marketing Association (1998), DMA Web Site Privacy

Rima Berzin recently inherited a 16),

Policy, (May laptop computer from

[available at http://www.the-dma.org].

her husband and began an -intense

(1998), DMA Web Sitetwo-day honeymoon

Privacy Policy, (October 27).

with the Internet. She went all the way; buying jeans at

DIRECT Newsline (1999), "FTC Commissioner Blasts Agency

GAP, browsing for books at Barnesandnoble.com

Over Privacy Stance," (July 29), [available at http://www. and

registering for Martha Stewart's online999/1999072902.htm].

directmag.com/content/newsline/l journal. While

Berzin was shopping, something very un-Martha

Donaldson, Thomas and Lee E. Preston (1995), "The Stakeholder

hap-

pened: her spree left muddy Theory

digital footprints all over the

of the Corporation," Academy of Management Review,

Net. Berzin, a Manhattan mother

20, 65-91. of two, is like a lot of

other Americans just stepping onto the Web. When a