Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Onour ModelingInflationDynamics 2014

Onour ModelingInflationDynamics 2014

Uploaded by

salmazeus87Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Onour ModelingInflationDynamics 2014

Onour ModelingInflationDynamics 2014

Uploaded by

salmazeus87Copyright:

Available Formats

Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies

Modeling Inflation Dynamics in Sudan 2008-2013

Author(s): Ibrahim A. Onour

Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies (2014)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep12665

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Arab Center for Research & Policy Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to this content.

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

RESEARCH PAPER

Modeling Inflation Dynamics in Sudan

2008-2013

Ibrahim A. Onour | July 2014

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modeling Inflation Dynamics in Sudan 2008-2013

Series: Research Paper

Ibrahim A. Onour | July 2014

Copyright © 2015 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved.

____________________________

The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute

and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on

the applied social sciences.

The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their

cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that

end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and

communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political

analysis, from an Arab perspective.

The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to

both Arab and non-Arab researchers.

Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies

PO Box 10277

Street No. 826, Zone 66

Doha, Qatar

Tel.: +974 44199777 | Fax: +974 44831651

www.dohainstitute.org

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Abstract

The primary purpose of the paper is to set up a macroeconomic model depicting the

domestic inflation dynamics of a conflict economy impeded by a parallel market for

foreign exchange as well as an internal political conflict. To investigate the sensitivity of

domestic inflation to macro variables using a time-varying coefficient estimation

approach employed on monthly data from the Sudan that was collected from January

2008 to December 2013. While government spending is the main driver of domestic

inflation, the increasing role of a parallel market for foreign exchange and imported

inflation on domestic inflation reveal an increasing sensitivity of Sudan’s economy to

external shocks. Significantly, the estimate of the domestic inflation rate predicted by

the model is about 22% above the officially-announced inflation rate. To manage

inflation the rate of state currency production must be regulated and a more flexible

official foreign exchange rate policy must be adopted.

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Table of Contents

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

Introduction

The Sudanese economy has often been read as a conflict economy whose growth has

been impeded by economic sanctions. This has been exacerbated since 2011 and South

Sudan’s secession and subsequent oil production shutdown (before which growth was

at least positive), which drastically altered Sudan’s economic growth prospects. The

latest International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates indicate that Sudan’s economy

contracted by 4.4% during 2012, which followed a contraction of 3.3% in 2011.

Currently, Sudan’s economic policy is guided by the Three Year Program (2012-14), a

course of action meant to deal with the negative consequences of South Sudan’s

secession. The program focuses on softening the adverse effects on Sudan’s negative

economic growth rate, and dealing with the resulting problems that arise in public

finances. Severe austerity measures are currently in place to aid the government in

implementing the program.

The economic situation in Sudan, already dire, has continued to deteriorate since South

Sudan’s secession. The shutdown in South Sudanese oil production severely affected

Sudan’s economic indicators. Further exacerbating matters, economic sanctions remain

in place on Sudan, while aid and external economic activity is limited. The structural

economic shift caused by South Sudan’s secession has adversely affected virtually all of

the country’s economic growth prospects.

As a consequence of secession and the subsequent disappearance of oil revenues,

Sudan’s attention shifted towards agriculture and gold mining as two potentially

lucrative – and in case of agriculture almost untapped – sectors of the economy. Gold in

particular has been touted as oil’s possible replacement. Sudan’s services sector is

currently driven by the telecommunications industry, while the banking sector is also

relatively well developed in regional terms. Both these industries, however, are

expected to feel the impact of the country’s fiscal deficit, which has resulted in severe

austerity measures including higher tax rates and the removal of fuel subsidies. Soaring

food prices, along with the cessation of oil exportation, led to crippling inflation in 2012

and 2013. Although the devaluation of Sudan’s national currency was necessary to

realign the Sudanese pound to a level resembling its internationally perceived value,

this also meant that the cost of imports increased in local currency terms.

Since losing more than half its oil reserves to South Sudan in 2011, Sudan has been

struggling to keep down consumer price index (CPI) inflation levels. The 2013 IMF data

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

gives a figure for CPI inflation of 28%, down from the 35% recorded in 2012. While this

forecast seems likely at the moment, there is a risk that CPI inflation could be much

higher, despite the likelihood of base effects occurring later in the year.

Looking fist at the relevant literature, the following sections will present a macro model

of the country’s conflict economy and an empirical analysis of the model and its data. A

final section presents the research findings, explaining the possible consequences of a

predicted inflation rate that is about 22% over the official estimate.

Previous Studies

In the past two decades a number of studies have investigated the causal relationship

between inflation and financial variables, including monetary aggregates and foreign

exchange rates, in developed economies (Estrella and Mishikin, 1997; Anderson and Sj,

2000; Chandra and Tallman, 1996; Gray and Thoma, 1998). The search for a causal

relationship between monetary aggregates and foreign exchange rates on inflation has

also been examined in African economies. London (1989), for example, analyzed the

experience of 23 African countries and concluded that exchange rates and money

growth had a significant effect on inflation. Chhiber et al (1989) looking specifically at

Zimbabwe claimed that exchange rate adjustment and domestic money growth had a

significant effect on inflation. Tegene (1989) employed Granger and Pierce causality

tests to discover that monetary expansion had caused domestic inflation in six African

countries. Agenor (1989) identified a significant role for parallel market rates on

inflation in four African countries, where Durevall and Ndung (2001) have more recently

employed an error correction model of inflation for Kenya, and found that money supply

only affected inflation in the short-run, and had a significant impact on the three month

treasury bill rate. Similar results from Nachenga (2001) confirmed the significance of T-

bills by on inflation levels in Uganda. Sacerdoti and Xiao (2001) indicated that money

growth had an insignificant effect on inflation in Madagascar, but that the effect of the

exchange rate was significant. Durevall and Kadenge (2001) showed a significant role

for exchange rate and foreign price changes after the economic reforms in Zimbabwe,

while Barnichon and Peiris (2007) used a panel co-integration model to verify the effect

of money and output gap on inflation in Sub-Saharan African countries. Balvy (2004)

and Nassar (2005) both found a long-term association between consumer prices and

money supply in Guinea and Madagascar respectively. Despite the apparent consensus

in empirical research on the impact of money supply and exchange rates on inflation in

low-income economies, however, studies on inflation dynamics in post-conflict countries

2

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

have been scarce. To fill the void, this paper aims first to structure a macro-economic

model depicting a conflict economy, and second, to assess the time-varying effects of

explanatory variables on inflation in Sudan using a dynamic estimation approach.

The Macroeconomic Model

In the Sudan, domestic firms produce for home consumption or export. Exports are

exogenously determined, as they depend mainly on international terms of trade. Home

goods (y) have a Cobb-Douglas production function, with imported producer goods Ip

and domestic labour Ly as the only inputs, as indicated in equation (1).

(1) Y ≤ Ip(1-α) Lyα, 0≤α≤1

The government stipulates that private firms convert a portion, (0 1) of their

export proceeds at the parallel rate b, and the remaining part at the official rate, e

which is always lower than b.

Despite foreign exchange regulations, firms can divert additional export proceeds

illegally at a parallel rate b, by under-invoicing export proceeds. As a result, deciding

what proportion of export proceeds to surrender at the official rate versus the parallel

rate depends on the size of , which will determine the amount of export proceeds that

will evade foreign exchange regulations.

The income of domestic firms consists of revenue from goods produced for domestic

consumption and revenue from export. Expenditure includes imported capital goods and

labour cost for both export and domestic consumption. Also included on the

expenditure side of the equation is the cost of under-invoicing export revenue, which is

assumed to have a linear function of , or more specifically ( / 2) . Determining a

firm’s choice in navigating these variables can be carried out by maximizing their profit

function with respect to Ly, Ip and Ф,, subject to production constraints:

Max[ p yY b(1 ( / 2) (1 )eX bP * m I p W ( Lx L y )]

(2)

Subject to:

Y ≤ Ip(1-α) Lyα, 0≤α≤1

The first order conditions for Ip, Ly and Ф are:

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

Py (1 ) I p L y P * m b

(3)

(4) Py αY/ Ly = W

(5) Φ = (1 – 1/π)

*

Where π = b/e, refers to the parallel rate premium, and P m is the dollar value of

import price. Concavity of equation (5) implies that a rising premium induces diversion

of foreign currency from the official market to the parallel market by under-invoicing

export revenue, but in a decreasing rate due to higher penalty cost when the size of

under-invoicing increases.

After a few manipulations and substitutions of equations (3) and (4) we get:

Py P * m b( I p L y ) w( I p L y ) 1

(6)

(I p / Ly )

When the ratio of capital and labour inputs combined in fixed proportions,

equation (6) reduces to:

Py 1Pm b 2 w

*

(7)

where 1 ( I p Ly ) , 2 ( I p Ly ) 1

Thus, domestic inflation can be expressed as a function of imported inflation and

domestic wage cost and the parallel rate thus:

Py 1 [ Pm b bPm ] 2 w

* *

2 w 3b 4 Pm

*

(8) for 2 0, 3 0, 4 0

Where a dot over a variable denotes change over time.

4

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

Since change in the real exchange rate reflects change in the relative price of tradables

r (eP * X Py )

to non-tradables, or , then change in the parallel exchange rate affects

the real exchange through its effect on domestic inflation (equation 8). In this definition

of the real exchange rate, the relation between real exchange rate and export is

defined as: (X r ) 0. , so that appreciation in real exchange rate induces non-oil

commodity exports.

Empirical Analysis

Equation (8) specifies that domestic inflation in a conflict economy is a function of

domestic money growth (or government spending), the parallel market rate for foreign

exchange, and imported inflation (measured by the global food price index).1 The effect

of growth in money supply on domestic inflation transmits through excess liquidity

generated in the economy. The demand for foreign currencies on the black markets

mainly stems from three activities: legal and illegal imports, portfolio diversification and

capital flight, and residents traveling abroad. The portfolio motive is believed to be

strong in high inflation economies, where real interest rates are very low, and where

considerable uncertainty over economic policies prevails. In these situations foreign

currency holdings represent a safeguard against domestic currency depreciation.

Portfolio diversification through the black market can also take place as a result of

restrictions on private capital outflows through the official market.

To assess the long term relationship between domestic inflation and the explanatory

variables the Autoregressive Distributed Lagged (ARDL) bound test for cointegration

analysis was used. To test for unit root in the data the conventional PP (Phillips-Perron)

test, which tests for the null-hypothesis of random walk, was used. The ARDL

cointegration test requires that each of the variables either be integrated of order 0, or

1 (i.e., I(0) or I(1)) but not I(p) for p>1, as the test result becomes inconclusive for

p>1. The results of unit root test included in table (1) indicate all variables are random

1

Domestic money supply data obtained from the Economic Report of Bank of Sudan and the foreign

exchange data from foreign exchange bureaus operating in the country, and the global food price index

data obtained from Index Mundi website at: http://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/.

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

walk (non-stationary) at levels, but at the first difference they reject the null-hypothesis

of random walk which indicates all variables are integrated of order one (I(1)).

Table (1): Unit Root Tests

level PP test Critical

statistics value

Domestic 2.79 6.25

Inflation

FX rate 2.73 6.25

M2 1.62 6.25

Foreign 2.66 6.25

Inflation

First difference

Domestic 13.68* 6.25

Inflation

FX rate 20.65* 6.25

M2 43.22* 6.25

Foreign 14.41* 6.25

inflation

*significant at 5% significance level.

Given that all variables are I (1) the ARDL bound test can be used to assess long-run

association between the dependent variable and the set of the independent variables.

The calculated F-statistic equals 5.67, which is greater than the upper bound critical

value (3.79) at 5% significance level. This result rejects the null-hypothesis of no

cointegration between the variables. Evidence of long-term association of variables in

equation (1) justifies the use of error correction specification. Table (2) presents

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

estimation results of time-varying coefficients using the flexible least square (FLS)

method. Results in table (2) indicate that during the sample period (2008–2013), the

effect of the parallel market rate for foreign exchange on domestic inflation jumped

from 5% to 37%, an indication of the increasing effect of the former on the latter.

During the same period, the effect of domestic money growth (growth in government

spending) on domestic inflation rate increased from 63% to 67%. This is a high, but

stable effect as indicated by the relatively low value of the coefficient of variation. The

impact of imported inflation on domestic inflation rate also increased from 10% to 27%.

In general, these results indicate that the transmission effect of the two variables

(parallel market rate and imported inflation) on domestic inflation are unstable, and

thus reveal the high sensitivity of the economy to external shock.

Table (2): Time-Varying Coefficient Estimates

variable coefficients coefficients coefficient

mean (min to max) of variation

Parallel 0.22 0.05 to 0.37 0.47

Market

Foreign 0.19 0.10 to 0.27 0.25

Inflation

Money 0.64 0.63 to 0.67 0.01

supply

constant 0.004 -0.001 to 0.18 18.9

Note: All variables transformed to log differences.

Table (3): Inflation Rates

year CPI-based Model-based % Change

2013 Inflation rate Inflation rate

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

Jan 43.6 42.1 -3

Feb 48.8 55.9 14.5

Mar 47.9 60.4 26.1

Apr 41.4 57.6 39.1

May 37.3 48.4 29.7

Jun 27.1 45.7 68.6

Jul 23.8 33.4 40.3

Aug 22.9 28.5 24.4

Sep 29.4 27.6 -6.1

Oct 40.3 35.9 -10.9

Nov 42.8 48.6 13.5

Dec 41.9 51.9 23.8

Mean 37.2 44.7 20.2

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

Concluding Remarks

The dynamics of inflation in a conflict economy enduring political instability and external

economic sanctions have thus been examined using a time-varying coefficient

estimation approach. This was done by setting up a macroeconomic model featuring a

conflict economy reflecting active parallel market for foreign exchange and excessive

government spending on non-productive activities (i.e. military and security spending).

The results indicate that:

a) The effect of the parallel market rate for foreign exchange on the domestic

inflation rate jumped during the sample period from 5% to 37%, an indication of

the increasing role of the parallel market rate for foreign exchange on domestic

inflation in the post-secession period.

b) The effect of domestic money growth on domestic inflation increased from 63%

to 67%, which, though a relatively sizable effect, is stable as indicated by the

low value of the coefficient of variation.

c) The impact of imported inflation on the domestic inflation rate during the post-

secession period also increased from 10% to 27%.

d) The increasing role of the parallel market and imported inflation on domestic

inflation indicates the increasing exposure of Sudan’s economy to external

shocks.

e) The official government figures of domestic inflation rates underestimate the

actual inflation rate, since our model-based estimates of domestic inflation rate

are about 22% above the officially announced inflation rate.

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

Bibliography

Agenor, Pierre-Richard (1989). Money, Exchange Rates, and Inflation in Africa: A Vector

Autoregression Analysis, unpublished, International Monetary Fund, November.

Andersson, P. and Sj (2000). Controlling inflation during structural adjustment: The

case of Zambia. HIID Development Discussion Papers (754).

Chandra, N. and E. W. Tallman (1996). The information content of financial aggregates

in Australia. Research Discussion Paper, Reserve bank of Australia (9606).

Chandra, N. and E. W. Tallman (1997). Financial aggregates as conditioning information

for Australian output and inflation. Research Discussion Paper, Reserve bank of

Australia (9704).

Chhibber, Ajay, Joaquin Cottani, Reza Firuzabadi, and Michael Walton (1989). Inflation,

Price Controls, and Fiscal Adjustment: The Case of Zimbabwe. Working Paper WPS 192,

The World Bank.

Durevall, D. and P. Kadenge (2001). Inflation in the Transition to a Market Economy,

Chapter 4. Palgrave. In: Macroeconomic and Structural Adjustment Policies in

Zimbabwe.

Durevall, D. and Ndung'u (2001). A dynamic inflation model for Kenya, 1974-1996.

Journal of African Economies 10 (1).

Estrella, A. and F. S. Mishikin (1997). Is there a role for monetary aggregates for

conduct of monetary policy? Journal Of Monetary Economics 40.

Gray, J. A. and M. A. Thoma (1998). Financial market variables do not predict real

activity. Economic Enquiry 36.

London, Anselm (1989). Money, Inflation, and Adjustment Policy in Africa: Some

Further Evidence. African Development Review, 1: 87-111.

Nachenga, J. C. (2001). Financial liberalization, money demand and inflation in Uganda.

IMF Working Paper (01-118).

Phillip, P.C.B. and Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series Regression.

Biometrika, 75: 335-436.

10

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

Sacerdoti, E. and Y. Xiao (2001). Inflation dynamics in Madagascar, 1971-2000. IMF

Working Paper (01-168).

Tegene, Abebayehu (1989). The Monetarist Explanation of Inflation: The Experience of

Six African Countries. Journal of Economic Studies, 16 (March): 5-18.

11

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

Appendix: Row Data

Y M FX GF

11.2 22624.3 2.82 125

11.1 22732.1 2.86 126

10.9 23716.1 3.1 126.73

8.5 24194.6 3.07 132.67

8.9 24257.1 3.28 142.37

9.9 25517.2 3.34 144.06

9.8 25329.9 3.38 139.17

10.4 26337.3 3.51 138.27

12.9 26507.6 3.4 135.23

12.9 27271.2 3.4 136.56

14.5 28322.9 3.36 140.55

13.4 29056 3.2 143.12

14.6 29056 2.67 142.23

14.3 29431.4 2.67 141.14

14.8 30155.9 2.68 142.02

15.1 31121.4 2.54 145.98

15.2 31065.5 2.75 144.04

15.6 32083.9 2.81 140.92

13 32724.7 2.82 147.99

10.3 32741.8 2.83 154.88

12

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

MODELING INFLATION DYNAMICS IN SUDAN

9.2 33397.5 2.91 159.04

9.7 33302.1 2.95 165.92

9.8 34606.5 2.96 168.23

15.4 35497.9 3.21 179.35

16.7 36388.6 3.21 186.69

16.9 36810.1 3.29 193.74

17.1 37798.6 3.43 189.31

16.5 37735.7 3.29 194.72

16.8 38426.8 3.22 191.01

15 39012.8 3.34 185.47

17.6 38679.7 3.48 184.14

21.1 39402.5 3.68 185.5

20.7 38106.8 3.98 178.87

19.8 39326.9 4.07 168.52

19.1 40101.8 4.08 167.06

18.9 41853 4.38 163.77

19.3 44024.2 4.63 165.64

21.3 43699.9 4.86 170.39

22.4 44708.5 5.03 173.84

28.6 46187.5 5.49 173.55

30.4 46608.8 5.73 169.21

37.2 51751.5 5.42 167.93

41.6 52550.6 5.54 182.75

42.1 54039.7 5.56 183.92

13

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARAB CENTER FOR RESEARCH AND POLICY STUDIES

41.6 55015.8 5.5 180.77

45.3 57075.4 5.53 177.2

46.5 57373.5 5.53 175.63

44.4 58663.3 5.52 176.89

44 59285.2 5.52 178.36

43.6 60549.6 6.4 178.79

46.8 61046.2 6.9 177.56

47.9 62238.9 6.85 177.08

41.4 62848.6 6.3 181.33

37.3 62967.4 6.55 181.14

27.1 64430.6 6.95 179.66

23.8 64490.3 7.12 172.15

22.9 64790.5 7.4 165.99

29.4 66165.4 7.5 167.2

40.3 66260.8 7.75 165.69

42.6 66445.7 7.8 170.49

Y= consumer price index based domestic inflation rate.

M= domestic money supply as represented by high powered money.

FX= black market rate for foreign exchange.

14

This content downloaded from

78.188.50.43 on Fri, 17 May 2024 18:36:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Part 2 MGMT Exit Exam Worksheet QuestionDocument26 pagesPart 2 MGMT Exit Exam Worksheet QuestionTigabu Tegene93% (29)

- InterSchool Activity ScriptDocument7 pagesInterSchool Activity ScriptJessica Loren Leyco87% (15)

- The Role of Sterilization Policy in Addressing The Impact of Public Expenditures in Iraq During The Period (2003-2017) Instructor: Naji Radees Abd Iraqi Parliament MemberDocument17 pagesThe Role of Sterilization Policy in Addressing The Impact of Public Expenditures in Iraq During The Period (2003-2017) Instructor: Naji Radees Abd Iraqi Parliament MemberLawa samanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Financial Globalization On Economic Growth in The Kurdistan Region of Iraq: An Empirical InvestigationDocument28 pagesThe Impact of Financial Globalization On Economic Growth in The Kurdistan Region of Iraq: An Empirical Investigationnweger2005No ratings yet

- Muhammad Aurmaghan 498 PP (54-67)Document14 pagesMuhammad Aurmaghan 498 PP (54-67)International Journal of Management Research and Emerging SciencesNo ratings yet

- Economic Freedom, FDI, Inflation, and Economic GrowthDocument10 pagesEconomic Freedom, FDI, Inflation, and Economic GrowthPutu SulasniNo ratings yet

- Seyoum ForeignDirectInvestment 2015Document21 pagesSeyoum ForeignDirectInvestment 2015aminah.tasnimNo ratings yet

- OhiomuDocument19 pagesOhiomuixora indah tinovaNo ratings yet

- Gaies FinancialOpennessGrowth 2019Document40 pagesGaies FinancialOpennessGrowth 2019aminah.tasnimNo ratings yet

- An Economic Analysis of The Welfare Effects of Higher Import Price Induced by Naira DevaluationDocument9 pagesAn Economic Analysis of The Welfare Effects of Higher Import Price Induced by Naira DevaluationGaniyuNo ratings yet

- Academia EdiDocument14 pagesAcademia EdiRia LestariNo ratings yet

- Impact of Corruption in AfricaDocument8 pagesImpact of Corruption in Africavanshikamoosaye5No ratings yet

- External Debt Burden and Its Determinants in NigeriaDocument7 pagesExternal Debt Burden and Its Determinants in NigeriaNhi NguyễnNo ratings yet

- External Shocks and Macroeconomic Performances in Africa: Adigun, A. O. & Ogunleye, E. ODocument12 pagesExternal Shocks and Macroeconomic Performances in Africa: Adigun, A. O. & Ogunleye, E. OTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- ተመሰገን (1)Document18 pagesተመሰገን (1)yusuf kesoNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Monetary Policy and Its LaDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Monetary Policy and Its Laibrahim javedNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Exchange Rate Volatility On The NigeDocument24 pagesThe Impact of Exchange Rate Volatility On The NigeFisayo BakareNo ratings yet

- Impact of External Debt On Exchange Rate in Post Reform India: A Co-Integration ApproachDocument9 pagesImpact of External Debt On Exchange Rate in Post Reform India: A Co-Integration Approachsanket patilNo ratings yet

- ECONOMICS HOLIDAY HOMEWORK - Term 2Document3 pagesECONOMICS HOLIDAY HOMEWORK - Term 2Adhith MuthurajNo ratings yet

- Areas of Strength: 2. Areas of Weakness: 3. How To ImproveDocument7 pagesAreas of Strength: 2. Areas of Weakness: 3. How To ImproveDevender SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Financial Institutions on Economic Growth in NigeriaDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Financial Institutions on Economic Growth in NigeriaNwigwe Promise ChukwuebukaNo ratings yet

- Editor in chief,+EJBMR 891Document3 pagesEditor in chief,+EJBMR 891Sabiha IslamNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument7 pages1 PBCourtney MosekiNo ratings yet

- Inflation Rate, Foreign Direct Investment, Interest Rate, and Economic Growth in Sub Sahara Africa Evidence From Emerging NationsDocument8 pagesInflation Rate, Foreign Direct Investment, Interest Rate, and Economic Growth in Sub Sahara Africa Evidence From Emerging NationsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Impact of Money Supply and Inflation On Economic GDocument13 pagesImpact of Money Supply and Inflation On Economic GdarshanNo ratings yet

- haris boiDocument24 pagesharis boiMuhammad HarisNo ratings yet

- IJHSSIPUBLICATION2Document13 pagesIJHSSIPUBLICATION2Soumojit ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Quality Influence On Shadow Economy DevelopmentDocument29 pagesQuality Influence On Shadow Economy DevelopmentRabaa DooriiNo ratings yet

- Seminar 1 FDIDocument9 pagesSeminar 1 FDIBằng HữuNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3480082Document35 pagesSSRN Id3480082Abhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- WP 2401Document34 pagesWP 2401Mmangaliso KhumaloNo ratings yet

- 1.1. Background of The Study: Chapter OneDocument14 pages1.1. Background of The Study: Chapter OneabaynehNo ratings yet

- 86-Article Text-433-5-10-20220806Document10 pages86-Article Text-433-5-10-20220806Ramadhan AdityaNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomic Factors and Economic Growth in MauritiusDocument35 pagesMacroeconomic Factors and Economic Growth in MauritiusSami YaahNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate Fluctuations and Economic Growth in Nigeria 1981 2020Document16 pagesExchange Rate Fluctuations and Economic Growth in Nigeria 1981 2020Ayano DavidNo ratings yet

- 55Document8 pages55Athraa DaviesNo ratings yet

- 1 African Development Review GhanaDocument11 pages1 African Development Review GhanaGIANFRANCO EDUARDO LLERENA ILIZARBENo ratings yet

- Impact of Monetary Policy On EconomicDocument10 pagesImpact of Monetary Policy On EconomicbiaremaNo ratings yet

- EconomicGrowthinNepal MacroeconomicDeterminantsDocument8 pagesEconomicGrowthinNepal MacroeconomicDeterminantsratna hari prajapatiNo ratings yet

- Chari Boru Bariso's Econ GuidsesDocument6 pagesChari Boru Bariso's Econ GuidsesSabboona Gujii GirjaaNo ratings yet

- Financial Deepening and Economic Growth in Nigeria: Evidence From 1982 - 2019Document6 pagesFinancial Deepening and Economic Growth in Nigeria: Evidence From 1982 - 2019kehinde joshuaNo ratings yet

- 16-Financial Inclusiveness and Economic Growth - New Evidence Using A Threshold Regression AnalysiDocument21 pages16-Financial Inclusiveness and Economic Growth - New Evidence Using A Threshold Regression AnalysiJOSEPHNo ratings yet

- (Mckibbin & Fernando, 2020) (Tan, Mohamed, Habibullah, & Chin, 2020)Document12 pages(Mckibbin & Fernando, 2020) (Tan, Mohamed, Habibullah, & Chin, 2020)asma munifatussaidahNo ratings yet

- EFFECT OF EXCHANGE RATE ON ECONOMIC GROWTH IN NIGERIADocument11 pagesEFFECT OF EXCHANGE RATE ON ECONOMIC GROWTH IN NIGERIANwigwe Promise ChukwuebukaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Monetary Policies On The Growth of The Insurance Sector in NigeriaDocument10 pagesEffect of Monetary Policies On The Growth of The Insurance Sector in NigeriaEverpeeNo ratings yet

- Financial Deepening and Per Capita Income in NigeriaDocument23 pagesFinancial Deepening and Per Capita Income in Nigeriakahal29No ratings yet

- Exchange Rate Volatility and Inflation Upturn in Nigeria: Testing For Vector Error Correction ModelDocument20 pagesExchange Rate Volatility and Inflation Upturn in Nigeria: Testing For Vector Error Correction ModelCARLOS ANDRES PALOMINO CASTRONo ratings yet

- The Impact of Inflation Towards Foreign Direct Investment in Malaysia and IranDocument16 pagesThe Impact of Inflation Towards Foreign Direct Investment in Malaysia and IranZHENG SHEM LIMNo ratings yet

- Public Debt and Inflation in Nigeria: An Econometric AnalysisDocument6 pagesPublic Debt and Inflation in Nigeria: An Econometric AnalysisDr. Ezeanyeji ClementNo ratings yet

- San Ana Isah KudaiDocument48 pagesSan Ana Isah KudaiYahya MusaNo ratings yet

- Impact of FDI On Economic Growth of SAARC NationDocument11 pagesImpact of FDI On Economic Growth of SAARC Nationaadolf2004No ratings yet

- Analysis of The Impact of External Debt On Economic Growth in An Emerging Economy: Evidence From NigeriaDocument18 pagesAnalysis of The Impact of External Debt On Economic Growth in An Emerging Economy: Evidence From Nigeriakenneth jajaNo ratings yet

- Archibong WashingtonConsensusReforms 2021Document25 pagesArchibong WashingtonConsensusReforms 2021ruth kolajoNo ratings yet

- External Debt Accumulation and Its Impact On Economic Growth in PakistanDocument17 pagesExternal Debt Accumulation and Its Impact On Economic Growth in PakistanEngr. Madeeha SaeedNo ratings yet

- Eric Ea Seng Huat - J19031573 - Fin3214 - F1Document14 pagesEric Ea Seng Huat - J19031573 - Fin3214 - F1eaNo ratings yet

- Thepoliticaleconomyofspecialeconomiczonesthecasesof Ethiopiaand VietnamDocument29 pagesThepoliticaleconomyofspecialeconomiczonesthecasesof Ethiopiaand VietnamHagos GebreamlakNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2607432Document16 pagesSSRN Id2607432Mbongeni ShongweNo ratings yet

- Siddiqui InternationalTradeWTO 2016Document28 pagesSiddiqui InternationalTradeWTO 2016Prince KatheweraNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument12 pages1 PBCalista FNo ratings yet

- Wa0101.Document23 pagesWa0101.Qamar VirkNo ratings yet

- 4549 18063 1 PBDocument11 pages4549 18063 1 PBdelian verrelNo ratings yet

- Report of the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development 2020: Financing for Sustainable Development ReportFrom EverandReport of the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development 2020: Financing for Sustainable Development ReportNo ratings yet

- NX Nastran Error ListDocument224 pagesNX Nastran Error ListAdriana Livadariu100% (3)

- Solve Splits Feedback ToolDocument6 pagesSolve Splits Feedback ToolkabyaNo ratings yet

- LNM Dow Inspirage 2021 Aug 04 FinalDocument25 pagesLNM Dow Inspirage 2021 Aug 04 FinalJoshua LimNo ratings yet

- Taxation: Bmbes 2020 Barangay Micro Business Enterprise BMBE Law's ObjectiveDocument3 pagesTaxation: Bmbes 2020 Barangay Micro Business Enterprise BMBE Law's Objectivekris mNo ratings yet

- Unity (Game Engine) - WikipediaDocument4 pagesUnity (Game Engine) - WikipediaRituraj TripathyNo ratings yet

- Inventory - Product Catalogue: Code Description / Location / UOM BarcodeDocument93 pagesInventory - Product Catalogue: Code Description / Location / UOM Barcodefireman100% (1)

- Stakeholder Analysis Matrix TemplateDocument2 pagesStakeholder Analysis Matrix TemplateEmmaNo ratings yet

- Prospectus 2014Document12 pagesProspectus 2014PhaniKumarChodavarapuNo ratings yet

- VTP Version 3: Solution GuideDocument29 pagesVTP Version 3: Solution Guidejnichols1009No ratings yet

- CN Practical-Swapnil Tiwari 1713310233Document63 pagesCN Practical-Swapnil Tiwari 1713310233Shivam ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Timing in TTCANDocument8 pagesTiming in TTCANPOWERBASE100% (1)

- Advertisement Do More Harm Than GoodDocument1 pageAdvertisement Do More Harm Than Good박성진No ratings yet

- Annual ReportSummary 2012Document2 pagesAnnual ReportSummary 2012Erick Antonio Castillo GurdianNo ratings yet

- Cable - Datasheet - (En) NSSHCÖU, Prysmian - 2013-06-10 - Screened-Power-CableDocument4 pagesCable - Datasheet - (En) NSSHCÖU, Prysmian - 2013-06-10 - Screened-Power-CableA. Muhsin PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Grade 12 21 Century Skills Based TestDocument7 pagesMathematics Grade 12 21 Century Skills Based TestChester Austin Reese Maslog Jr.No ratings yet

- In Design: Iman BokhariDocument12 pagesIn Design: Iman Bokharimena_sky11No ratings yet

- Food Handlers Risk AssessmentDocument1 pageFood Handlers Risk AssessmentNidheesh K KNo ratings yet

- Sikafloor®-169: Product Data SheetDocument4 pagesSikafloor®-169: Product Data SheetMohammed AwfNo ratings yet

- CURRICULUM VITAE DhodhonkDocument1 pageCURRICULUM VITAE DhodhonkVeri MasywandiNo ratings yet

- Isihskipper January 2010Document25 pagesIsihskipper January 2010enelcharcoNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Exercise 1Document23 pagesLaboratory Exercise 1Paterson SoroñoNo ratings yet

- 416F SpecalogDocument9 pages416F Specalogagegnehutamirat100% (1)

- Learning Contract ETHICSDocument2 pagesLearning Contract ETHICSBUAHIN JANNANo ratings yet

- First 365 DaysDocument52 pagesFirst 365 DaysAmiel Francisco ReyesNo ratings yet

- 202010398-Kiran Shrestha-Assessment I - Network TopologiesDocument31 pages202010398-Kiran Shrestha-Assessment I - Network Topologieskimo shresthaNo ratings yet

- Smriti Swar - Brij - Sharma Interim ReportDocument96 pagesSmriti Swar - Brij - Sharma Interim Reportsms0331No ratings yet

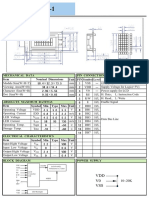

- V0 VSS VDD: Unit PIN Symbol Level Nominal Dimensions Pin Connections Function Mechanical Data ItemDocument1 pageV0 VSS VDD: Unit PIN Symbol Level Nominal Dimensions Pin Connections Function Mechanical Data ItemBasir Ahmad NooriNo ratings yet

- College of Forestry and Natural Resources Field of Study/Specialized Courses Prerequisite (S) Units Offering Production & Industrial ForestryDocument1 pageCollege of Forestry and Natural Resources Field of Study/Specialized Courses Prerequisite (S) Units Offering Production & Industrial ForestryAnai GelacioNo ratings yet