Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Freer Claim Preclusion

Freer Claim Preclusion

Uploaded by

Pegah AfsharOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Freer Claim Preclusion

Freer Claim Preclusion

Uploaded by

Pegah AfsharCopyright:

Available Formats

Freer: Civil Procedure The Preclusion Doctrine I. Defining the Issue a. Claim Preclusion i.

Is the modern terminology for res judicata which means the things has been decided; it also is sometimes called the rule against splitting a claim. ii. One bite of the apple. b. Issue Preclusion is the modern terminology for collateral estoppel. i. It is narrower than claim preclusion it precludes relitigation in Case 2 of a particular issue that was litigated and determined in Case 1. ii. Issue preclusion does not result in dismissal of Case 2. Rather, it may simply narrow the scope of what must be litigated in Case 2. iii. Both claim and issue preclusion are affirmative defenses under Federal Rule 8. Defendant must raise them at the risk of waiving them. c. Finality i. There is a particular interest in finality, litigation must be declared finished. d. Repose i. The defendant has the right to repose to know that she cannot be sued repeatedly on the same claim. e. Consistency f. Efficiency i. One opportunity to litigate a claim or an issue suffices to ensure each party of her day in court. g. Each state is free to determine its own preclusion rules, so long as they do not violate due process, and states have adopted different approaches to various issues. h. Law of the case i. Establishes that issues decided in a suit will not be relitigated in the same case. i. Judicial estoppel prevents a litigant from taking inconsistent positions in different cases. Claim Preclusion (Res Judicata) a. Single claim may afford more than one recovery. b. Three requirements for CP i. First, both Case 1 and Case 2 must have been brought by the same claimant against the same defendant. ii. Case 1 must have ended in a valid, final judgment on the merits. iii. Both Case 1 and Case 2 must be based upon the same claim.

II.

c. Merger: claimant won, and attempts to use same claim in case 2 and is barred. d. Barred: claimant lost, and attempts to use came claim in case 2 and is barred. e. Case 1 and Case 2 Were asserted by the same claimant against the same defendant. i. Unless the same party is asserting a claim in both cases, claim preclusion simply cannot apply. ii. Compulsory Counter Claim Rule 13(a) 1. If a defendant has a claim against the plaintiff and the claim arises from the same transaction or occurrence as the plaintiffs claim, she must assert it in the pending case. Failure to do so waives the claim. iii. Claim preclusion does not necessarily require that the claimant and defendants be exactly the same person in Case 1 and Case 2. 1. Privity: Some litigants are so closely related that litigation by one ought to bind the other. f. Case 1 ended in a valid final judgment on the merits i. Validity 1. The inquiry typically focuses on whether the court in Case 1 had subject matter jurisdiction over the case and personal jurisdiction over the parties. ii. Final judgment 1. A final judgment is one that ends the litigation on the merits and leaves nothing for the trial court to do but execute the judgment. 2. Before the appellate court has acted, is the final judgment entitled to a preclusive effect or is it held in abeyance until the resolution of the appeal? a. Federal law on the subject says that the judgment is entitled to preclusive effect, and most states agree. iii. On the merits 1. For a valid final judgment to be entitled to preclusive effect, it must have been based upon the meritsthat is, on the underlying dispute, the question of who did what. a. A judgment based upon something unrelated to the underlying disputesay, for example, on some procedural or jurisdictional basis should not be given preclusive effect. b. More accurate to think of the requirement as one that the court had the opportunity to get to the merits of the case, even if it did not actually do so.

i. i.e. summary judgment is on the merits. ii. Voluntary dismissal no on the merits iii. Involuntary dismissal for smj or pj not on the merits. iv. Involuntary dismissal for failure to comply with court order or any other reason on the merits. 2. Semtek a. 41(b), involuntary dismissal stops the plaintiff from refilling in the same federal court that dismissed the action. But whether the first courts dismissal is on the merits for claim preclusion and issue preclusion in other courts requires an analysis of federal common law, which, in turn, in a diversity case usually will look to the law of the state in which the federal court deciding Case 1 sat. Case 1 and Case 2 were based on the same claim a. Two Major Themes: Focus on Transactions or on Primary Rights Invaded. i. Federal law and the law of most states today adopt a transactional test for defining ones claim. 1. Two cases involve the same operative facts, transaction or occurrence, basic factual situation, defendants wrongdoing, or a single core of operative facts. 2. Restatement (Second) of Judgments, which provides that a claim encompasses all rights to relief with respect to all or any part of the transaction, or series of connected transactions, out of which the action arose. 3. Primary rights theory the claimant has a separate claim (and therefore can file a separate case) for each right violated by the defendant. b. Policy and Efficiency Considerations i. Transactional definition more efficient. 1. Transactional test comports broadly with test for joinder and for supplemental jurisdiction. FRCP 14(a) adopts the same transaction or occurrence test. ii. Because Fed Rules are liberal and permit a claimant to assert all claimseven those not transactionally relatedin a single suit, it is fair to impose a claim preclusion rule requiring her to assert all transactionally related claims in Case 1. iii. Carter v. Hinkle

III.

IV.

1. The court thus recognized that a transactional test was more efficient, but concluded that primary rights was more consistent with other aspects of the law. c. Applications i. The Restatement (Second) also instructs us to look at transactions or a series of connected transactions. ii. The Restatement (Second) adds to this definition an instruction to adopt a pragmatic approach, with a focus on whether facts are connected closely in time, space, origin, or motivation and whether, taken together, they form a convenient unit for trial purposes, as well as whether treating them as a single claim will be consistent with the expectations of parties and businesses. d. Other Formulations of Claim i. Some courts espouse a sameness of the evidence test, under which claims are the same if the evidence needed to sustain the second action would have sustained the first. ii. Most courts seem to apply the test in this latter fashion. As such, in focusing on liability, this test seems to add nothing to a transactional test, which focuses on the transaction that gives rise to defendants liability. iii. The point of claim preclusion is that the claimant gets one shot at a claim, and thus cannot blame anyone but herself for leaving out some element of recovery or for failing to marshal facts in an effective way. e. Claims as Personal to Holder i. Claim preclusion does not force every person injured in a single case to join together in one suit. It simply forces each claimant to join the various elements of damage and legal theories arising from a claim into a single claim. ii. A claim, at least with regard to a single contract, is usually deemed to consist of all breaches that have occurred to the time of filing case 1. iii. If there are separate contracts, they are generally treated as separate claims. Issue Preclusion (Collateral Estoppel) i. Issue Preclusion is the modern terminology for the doctrine historically known as collateral estoppel. ii. Issue preclusion in contrast, applies only to preclude relitigation of an issue that the parties actually did litigate and the court determined in Case 1, it generally does not in itself cause dismissal of case 2. iii. The standard definition contains five requisites 1. Case 1 must have ended in a valid final judgment on the merits.

2. The same issue presented in Case 2 must have been litigated and determined in Case 1. 3. That issue must have been essential to the judgment in Case 1. 4. Issue Preclusion can only be asserted against one who was a party to Case 1 (or in privity with a party to Case 1). 5. The court in Case 2 must assess mutuality, which concerns the question of who may assert issue preclusion. b. Case 1 Ended in a valid final judgment on the Merits. c. The Same Issues Was Litigated and Determined in Case 1 i. The issue must have been litigated in Case 1. ii. Even though litigated, the issue must also have been determined in Case 1. iii. Speaking of the same issue in both cases. 1. Dismissal with prejudice a. Claim Preclusive effect. b. Not issue preclusive effect because no issues was litigated. 2. Default judgment a. Can have a claim preclusive effect. b. Will probably not carry issue preclusion because no issue was actually litigated in the default. 3. Summary Judgment a. Can carry an issue preclusive effect. i. The determination that there is no material factual dispute is adjudication on what facts exist and constitutes litigation. iv. The party asserting issue preclusion bears the burden of establishing that requirements are met, this burden includes presenting to the court in Case 2 and adequate record from Case 1 to support the assertion. d. Determining Whether the Cases Involve the Same Issue i. While discovery of new evidence may justify setting aside a judgment under FR 60(b)(2) (but only in limited circumstances it does not avoid the operation of issue preclusion). ii. Specifically, it instructs the court to look at such things as the degree of overlap between the evidence or arguments in Case 1 and Case 2, whether new evidence or argument in Case 2 involves the same rule of law as that in Case 1, whether pretrial preparation in Case 1 could reasonably have embraced the new evidence or argument in Case 2; and whether there is close relationship between the claims asserted in Case 1 and Case 2.

iii. The drafters of the Restatement (Second) deem it appropriate to expect a claimant to assert every possible basis for recovery in Case 1, but tent to allow a defendant to pick and choose among potential, defenses, retaining others for another day. iv. The Supreme Court has indicated that issue preclusion might not be available, however, for unmixed or pure questions of law that arise in successive cases involving unrelated subject matter. e. That Issue was Essential to the Judgment in Case 1 i. The Concept of Essentiality 1. To determine essentiality, we ask: If the finding on this issue had come out the other way, would the judgment be the same? a. If so, the finding is not essential to the judgment, because the judgment does not rest on the finding on the issue. f. The Problem of Alternative Determinations i. Alternative findings, then, offer two reasons for the same conclusion. ii. The traditional approach to the problem, reflected in the first Restatement of Judgments, holds that both of the alternatives findings are essential. iii. Under the Restatement (2), alternative determinations are deemed not to be essential to the judgment in Case 1 and thus neither one is entitled to issue preclusion in Case 2. 1. Exception a. Provides for issue preclusion on one or both o the alternative determinations if they are upheld expressly on appeal. b. With Alternative determinations, remember, either finding would dictate the judgment. g. Due Process: Against Whom Is Preclusion Asserted? i. Distinguishing between Due Process and Mutuality 1. Due Process inquiry concerns the question of against whom preclusion may be asserted 2. Mutuality inquiry concerns the question of by whom preclusion may be asserted. 3. Due Process ensures that one can only be bound by a judgment from Case 1 if she had a full and fair opportunity to litigate in Case 1. ii. Starting Point: Parties to Case 1 Can Be Bound 1. The concept of full and fair opportunity to be heard is flexible, but certainly includes someone who was a properly joined party in Case 1. 2. Conversely a non party to Case 1 generally will not be bound by the judgment in Case 1.

iii. Expanding the Realm of Who Can be Bound: Privity 1. The judgment in Case 1 binds not only parties but persons deemed to be in privity with parties in Case 1. 2. The term refers to a relationship between a nonparty to Case 1 and a party to Case 1. When the relationship is sufficiently close, courts justify binding the nonparty to the judgment. a. The idea is that the nonparty is so closely aligned with one who was a party to Case 1 that she has, in effect been accorded her day in court. 3. Successive Interest in Property. a. A non party to Case 1 may be bound by the judgment in that case if she succeeds to a property interest held by someone who was a party in case 1. 4. Nonparty Controls Litigation in Case 1. a. The Second general fact pattern involving binding a nonparty to case 1 arises when that nonparty controls the litigation for a party in Case 1. i. The party run the litigation in Case 1 ii. A direct financial or propriety interest in the litigation. 5. Nonparty in Case 1 Was represented by a party in Case 1 a. By fat the most expansive basis for finding privity between a party and nonparty involves representation. b. A nonparty to Case 1 can be bound by the judgment in Case 1 if her interest were adequately represented by a party to Case 1. i. I.E. Class Actions. ii. Litigation by or against fiduciaries 1. Guardian, guardian ad litem, conservator, committee. c. Virtual Representation i. Nonparties to Case 1 should be bound if their legal position in Case 2 is the same as that litigated in Case 1. ii. A person may be bound by a judgment even though not a party if one of the parties to the suit is so closely aligned with his interests as to be his virtual representative. iii. Virtual representation would be possible only if there was an express or implied

legal relationship in which parties to the first suit are accountable to nonparties who file a subsequent suit raising identical issues. iv. The fact that all 14 manufacturers are engaged in the manufacture of the same product does not create privity. v. For the most part, though courts have restrained the concept of virtual representation and have limited nonparty preclusion to the classic situations involving representation, as well as control by the nonparty, and successors in interest. h. Mutuality: By Whom Is Preclusion Asserted? i. Distinguishing Again Between Due Process and Mutuality 1. Preclusion may only be asserted against one who was a party (or in privity with a party) to Case 1. ii. The Starting Point: Mutuality of Estoppel and Exceptions to It 1. Mutuality of Estoppel is a very simple idea: The only people who an use preclusion in Case 2 are people who would be bound by the judgment in Case 1. 2. The most important development in preclusion law over the past two generations has been the move to permit nonmutual assertion of issue preclusion. Nonmutual simply means that issue preclusion is being used by someone who was not a party to Case 1. 3. The narrow exception to the mutuality applies only in a vicarious liability situation in which the primarily laible party is found not negligent in Case 1. Only in that instance does Case 2 lead to the two undesirable outcomes that may be avoided by allowing Owner to use issue preclusion in Case 2. iii. Rejection of Mutuality for Defendants (Nonmutual Defensive Issue Preclusion) 1. Every state is free to determine its own preclusion rules, so long as these rule do not violate constitutional guarantees. 2. Nonmutual preclusion, requires that the person against whom it is asserted had a full and fair opportunity to litigate in Case 1. 3. Blonder-Tongue a. The court concluded that the system of justice affords a litigant one full and fair opportunity to litigate an issue. Once that protection has been afforded, the litigant may be bound by the

finding on that issue in subsequent litigation, even by persons who were not parties (or in privity with a party) to Case 1. 4. Nonmutual defensive Issue preclusion a. Nonmutual means that issue preclusion is being used by one who was not a party to Case 1. Defensive means that the person using issue preclusion is Case 2 is the defendant. 5. Rejection of Mutuality for Claimants (Nonmutual Offensive Issue Preclusion). a. Nonmutual offensive issue preclusion. Nonmutual, as we know, means the person using issue preclusion was not a party to Case 1. b. Offensive means that the person using issue preclusion in Case 2 is a claimant (usually, of course, the plaintiff). i. This type of preclusion will likely increase rather than decrease the total amount of litigation, since potential (claimants) will have everything to gain and nothing to lose by not joining in Case 1. c. Parklane stands for the proposition that nonmutual offensive issue preclusion is appropriate, but only if the court in Case 2 is convinced (1) that the party using issue preclusion could not easily have joined in the earlier action and (2) that use of issue preclusion is not unfair to the defendant. i. Parklane reflects federal law and the law of several states, but apparently most states have not embraced nonmutual offensive issue preclusion. 6. Exceptions to the Operation of Preclusion a. In General i. It is inherent in the operation of both claim and issue preclusion that the party against whom preclusion is to be applied in Case 2 had a full and fair opportunity to present its position in Case 1. b. Claim Preclusion i. The principle exceptions to claim preclusion are catalogued in 26(1) of the Restatement (2) of Judgments. One set of exceptions applies when either the

V.

defendant or the court in Case 1 agrees to allow the claimant to split her claim. 1. Because preclusion is an affirmative defense, the defendant might waive a claim preclusion objection by acquiescing in multiple suits on the same claim. ii. Another exception applies if the claimant in Case 1 could not have sought all rights to relief for her claim because of limitations imposed on the court in Case 1. 1. Only if state law would not have allowed P to bring both assertions in a single case in some court should the exception be recognized. c. Issue Preclusion i. Issue preclusion might be avoided if the party against whom it is asserted could not have obtained review of the judgment in Case 1, or if a new determination of the issue is needed because of differences in the quality or extensiveness of the procedures followed by the courts or by factors relating to the allocation of jurisdiction between them. 1. In a criminal case, the defendant must be proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. I a civil case, in constrast, the claimant must prove the elements of her claim only by a preponderance of the evidence. ii. Occasionally (but rarely), an intervening change in the controlling law might justify an exception to issue preclusion d. Supreme court held that nonmutual offensive issue preclusion cannot be used in litigation against the United States. Full Faith and Credit and Related Topics a. In General i. Durfee v. Duke: 1. Full Faith and Credit thus generally requires every State to give to a judgment at least the res judicata effect which the judgment would be accorded in the State which rendered it.

b.

c.

d.

e.

ii. The constitutional provision requires that each state give full faith and credit to judicial proceedings of every other State, and thus applies only in state to state preclusion scenario.. iii. U.S. Code provides that a state to federal court in Case 2 must give the same full faith and credit as would be given by the state court that entered judgment in Case 1. State to State Preclusion i. The court in Case 2 must apply the preclusion law of the state whose court decided Case 1. 1. 1738 requires the court in Case 2 to give the judgment the same effect it would have in the state that decided Case 1. State to Federal Preclusion i. Congress has specifically required all federal courts to give preclusive effect to state court judgments whenever the courts of the state from which the judgments emerged would do so. 1738 ii. Supreme Court 1. Full Faith and Credit does not require the court in Case 2 to adopt the practices of other states regarding the time, manner, and mechanisms for enforcing judgments. 2. The orders of one court commanding action or inaction cannot be allowed to interfere with litigation before a different judicial system. 3. The Supreme Court sees the full faith and credit statute as a strict command to give the judgment from Case 1 truly the same full faith and credit it would receive in the state courts that decided Case 1. Federal To state Preclusion i. The supremacy clause of the constitution operates to make federal judgments binding. ii. Federal common law would usually adopt the preclusion law of the state in which the federal court sat in Case 1. Federal to Federal Preclusion i. The federal court in Case 2 would apply federal common law to determine the preclusive effect of the judgment from Case 1. ii. Federal common law, however, will often incorporate state law of the state in which the federal court in Case 1 sat. The court in Case 2 has considerable flexibility in determining the content of governing federal common law.

You might also like

- KPI Dictionary Vol1 PreviewDocument12 pagesKPI Dictionary Vol1 PreviewJahja Aja64% (11)

- Civ Pro Essay FormatDocument1 pageCiv Pro Essay FormatMolly EnoNo ratings yet

- Rules Draft 1Document4 pagesRules Draft 1Rishabh Agny100% (1)

- Contracts Bender4Document93 pagesContracts Bender4Laura CNo ratings yet

- Gorean Adventures 01 The Tower of ArtDocument36 pagesGorean Adventures 01 The Tower of ArtMahyná Cristina0% (2)

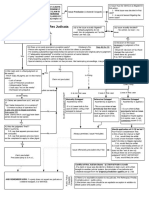

- PJ FlowchartDocument1 pagePJ Flowchartmischa29No ratings yet

- Civ Pro Personal Jurisdiction Essay A+ OutlineDocument5 pagesCiv Pro Personal Jurisdiction Essay A+ OutlineBianca Dacres100% (1)

- Civ Pro Case ChartDocument14 pagesCiv Pro Case ChartMadeline Taylor DiazNo ratings yet

- Contracts II OutlineDocument79 pagesContracts II Outlinenathanlawschool100% (1)

- Tax Answers - Chapter 3Document4 pagesTax Answers - Chapter 3Jonathan VelaNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Case Dispostion ChartDocument2 pagesCivil Procedure Case Dispostion ChartZachary Figueroa100% (1)

- GCS Interview Questions GuideDocument14 pagesGCS Interview Questions GuideAnkita ManchandaNo ratings yet

- Villagracia Vs Fifth 5th Shari A District Court Case DigestDocument2 pagesVillagracia Vs Fifth 5th Shari A District Court Case Digestyannie110% (1)

- Civ Pro II Outline STEWARTDocument40 pagesCiv Pro II Outline STEWARTsanghoon-lee-4306No ratings yet

- Short Draft 2Document12 pagesShort Draft 2Rishabh AgnyNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Outline 1Document29 pagesCiv Pro Outline 1T Maxine Woods-McMillanNo ratings yet

- 1L Civ Pro Erie For FinalDocument2 pages1L Civ Pro Erie For FinalMichelle ChuNo ratings yet

- PJ and DiversityDocument2 pagesPJ and DiversityjuicykeyNo ratings yet

- CivPro Law in A Flash Outline of BLLDocument2 pagesCivPro Law in A Flash Outline of BLLjohngsimNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro CasesCourt CasesDocument5 pagesCiv Pro CasesCourt CasesenigmarsNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure - Freer Fall 00 01Document27 pagesCivil Procedure - Freer Fall 00 01lssucks1234No ratings yet

- Babich CivPro Fall 2017Document30 pagesBabich CivPro Fall 2017Jelani WatsonNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro OutlineDocument8 pagesCiv Pro Outlinedurangokid22No ratings yet

- Res JudicataDocument1 pageRes JudicataTed FlannetyNo ratings yet

- Parties. ALIENAGE If One Party Is Citizen of Foreign State, Alienage Jdx. Satisfied, Except WhenDocument2 pagesParties. ALIENAGE If One Party Is Citizen of Foreign State, Alienage Jdx. Satisfied, Except WhenCory BakerNo ratings yet

- Federal Civil Procedure OutlineDocument10 pagesFederal Civil Procedure OutlinefredtvNo ratings yet

- 2006 Personal Jurisdiction ChecklistDocument9 pages2006 Personal Jurisdiction Checklistkatiana26100% (1)

- Civil Procedure - HLS - DS - Visiting ProfDocument22 pagesCivil Procedure - HLS - DS - Visiting ProfSarah EunJu LeeNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Outline Part VI: Erie DoctrineDocument6 pagesCivil Procedure Outline Part VI: Erie DoctrineMorgyn Shae CooperNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure SkeletonDocument8 pagesCivil Procedure SkeletonTOny AwadallaNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure OutlineDocument23 pagesCivil Procedure OutlineThomas Jefferson100% (1)

- Civil Procedure OutlineDocument18 pagesCivil Procedure OutlineGevork JabakchurianNo ratings yet

- Flowchart - Personal JurisdictionDocument1 pageFlowchart - Personal JurisdictionJNo ratings yet

- KP FRCP Fall Civ ProDocument14 pagesKP FRCP Fall Civ ProadamNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro I ChecklistDocument4 pagesCiv Pro I ChecklistDario Rabak0% (1)

- Civil Procedure Bare Bones OutlineDocument9 pagesCivil Procedure Bare Bones OutlineLindaNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro 2 Rules ChartDocument6 pagesCiv Pro 2 Rules ChartRonnie Barcena Jr.No ratings yet

- Character Evidence Rules: Introduction of Evidence Sufficient To Support A FindingDocument18 pagesCharacter Evidence Rules: Introduction of Evidence Sufficient To Support A FindingTanishka Vanessa CruzNo ratings yet

- Con Law Case ChartDocument5 pagesCon Law Case ChartBree SavageNo ratings yet

- Counterclaims Analysis: The Answer To All Questions Must Be "Yes" For The Action To ProceedDocument3 pagesCounterclaims Analysis: The Answer To All Questions Must Be "Yes" For The Action To ProceedJenna Alia100% (1)

- Civ Pro ChecklistsDocument13 pagesCiv Pro ChecklistsNick Van LeuvenNo ratings yet

- Sample EssayDocument4 pagesSample EssayJulia MNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Chart: Rev. July 2018Document5 pagesHearsay Chart: Rev. July 2018Fernand CastroNo ratings yet

- Final Property Outline KacieDocument86 pagesFinal Property Outline KacieNicole AmaranteNo ratings yet

- Outline Draft 1Document28 pagesOutline Draft 1Rishabh Agny100% (1)

- Clear and Present Danger Test: Advocacy of Illegal ActionDocument98 pagesClear and Present Danger Test: Advocacy of Illegal ActionDavid YergeeNo ratings yet

- Personal Jurisdiction FlowchartDocument1 pagePersonal Jurisdiction FlowchartDenise NicoleNo ratings yet

- Fall Civil Procedure Outline FinalDocument22 pagesFall Civil Procedure Outline FinalKiersten Kiki Sellers100% (1)

- Civil Procedure II Pre-Writes: InterventionDocument24 pagesCivil Procedure II Pre-Writes: InterventionMorgyn Shae Cooper50% (2)

- Civ Pro (Discovery) FlowchartDocument1 pageCiv Pro (Discovery) FlowchartJack EllisNo ratings yet

- Outline-Civ.-pro II (Very Thorough)Document37 pagesOutline-Civ.-pro II (Very Thorough)adam100% (1)

- Con Law 2 OutlineDocument48 pagesCon Law 2 OutlineNolaMayoNo ratings yet

- Congressional PowerDocument1 pageCongressional Powerashleyrmorgan0% (1)

- Pers JRD FlowchartDocument1 pagePers JRD FlowchartpromogoatNo ratings yet

- Davis EvidenceDocument101 pagesDavis EvidenceKaren DulaNo ratings yet

- One Sheet J&J (Exam Day)Document3 pagesOne Sheet J&J (Exam Day)Naadia Ali-Yallah100% (1)

- Applying The Hanna/Erie Doctrine: Yes No Yes Yes NoDocument1 pageApplying The Hanna/Erie Doctrine: Yes No Yes Yes NoMolly EnoNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Yeazell Fall 2012Document37 pagesCiv Pro Yeazell Fall 2012Thomas Jefferson67% (3)

- Public Function Test - A Private Entity Engaging in An Activity That HasDocument24 pagesPublic Function Test - A Private Entity Engaging in An Activity That HasNate Enzo100% (1)

- Criminal Procedure Epstein Fall 2009-1Document16 pagesCriminal Procedure Epstein Fall 2009-1dicleverNo ratings yet

- Rule 13. Counterclaim and CrossclaimDocument8 pagesRule 13. Counterclaim and CrossclaimJosh YoungermanNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Ii RulesDocument8 pagesCivil Procedure Ii RulesPaola BautistaNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Spillenger FA 2003Document43 pagesCiv Pro Spillenger FA 2003Thomas JeffersonNo ratings yet

- 10961C Automating Administration With Windows PowerShellDocument12 pages10961C Automating Administration With Windows PowerShellChris BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of The Adoption of Stephanie Nathy Astorga GarciaDocument1 pageIn The Matter of The Adoption of Stephanie Nathy Astorga GarciaMarga LeraNo ratings yet

- Chap04 Test BankDocument47 pagesChap04 Test BankJacob MullerNo ratings yet

- BillPayment FormDocument2 pagesBillPayment FormThúy An Nguyễn100% (1)

- Week 5Document42 pagesWeek 5Nabilah Mat YasimNo ratings yet

- Oracle Exambible 1z0-083 Sample Question 2020-Oct-08 by Hayden 71q VceDocument11 pagesOracle Exambible 1z0-083 Sample Question 2020-Oct-08 by Hayden 71q VcejowbrowNo ratings yet

- Vadodara Stock Exchange Ltd.Document97 pagesVadodara Stock Exchange Ltd.Ashwin KevatNo ratings yet

- Traverse Adjustment ReportDocument3 pagesTraverse Adjustment Reportpopovicib_2No ratings yet

- B 1410 - B&N Contract Furniture S.A. - Almeco Interior GMBHDocument2 pagesB 1410 - B&N Contract Furniture S.A. - Almeco Interior GMBHmaxNo ratings yet

- BU2103 - IBM G2 International Trade Law - S20 - Quiz #2 - TonyDocument7 pagesBU2103 - IBM G2 International Trade Law - S20 - Quiz #2 - TonyRajvi ChatwaniNo ratings yet

- Materi Dasar Pengenalan Kapal-PrintoutDocument28 pagesMateri Dasar Pengenalan Kapal-Printoutdian.yudistiro8435100% (1)

- 9-Pipes and Cisterns-06-01-2023Document18 pages9-Pipes and Cisterns-06-01-2023Srikar Prasad D 21BEC2075No ratings yet

- (Routledge Contemporary Economic History of Europe Series) Hans-Joachim Braun-The German Economy in The Twentieth Century - The German Reich and The Federal Republic-Routledge (1990)Document292 pages(Routledge Contemporary Economic History of Europe Series) Hans-Joachim Braun-The German Economy in The Twentieth Century - The German Reich and The Federal Republic-Routledge (1990)Adrian PredaNo ratings yet

- Keratoconus Screening in Primary Eye Care - A General OverviewDocument7 pagesKeratoconus Screening in Primary Eye Care - A General Overviewnurfatminsari almaidinNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Hem KumarDocument6 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Hem KumarHem KumarNo ratings yet

- 18 March 2021 - BEO Kemenhub Dir. Sarana Transportasi Jalan Group 1Document2 pages18 March 2021 - BEO Kemenhub Dir. Sarana Transportasi Jalan Group 1Muhammad Wafiq AzzisNo ratings yet

- Universal Quantum Computation With Ideal Clifford Gates and Noisy AncillasDocument14 pagesUniversal Quantum Computation With Ideal Clifford Gates and Noisy Ancillas冰煌雪舞No ratings yet

- Skull and Bones ChartDocument72 pagesSkull and Bones ChartWilliam Litynski100% (3)

- Individual Daily Log and Accomplishment Report: Enclosure No. 3 To Deped Order No. 011, S. 2020Document2 pagesIndividual Daily Log and Accomplishment Report: Enclosure No. 3 To Deped Order No. 011, S. 2020cristina maquintoNo ratings yet

- Pre-Image-Kit Release Notes R22Document7 pagesPre-Image-Kit Release Notes R22Abdelmadjid BouamamaNo ratings yet

- Hospitals in BengaluruDocument68 pagesHospitals in BengaluruKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Based On The 1979 Standards of Professional Practice/ SPPDocument10 pagesBased On The 1979 Standards of Professional Practice/ SPPOwns DialaNo ratings yet

- Autocad Certification Exam Prep EbookDocument27 pagesAutocad Certification Exam Prep Ebookdisguisedacc511No ratings yet

- Export Small Green Cardamom Project ReportDocument27 pagesExport Small Green Cardamom Project ReportK K JayanNo ratings yet

- 10 Tricky PSLE Math QuestionsDocument6 pages10 Tricky PSLE Math QuestionsClarisa CynthiaNo ratings yet

- Pickett v. United States, 216 U.S. 456 (1910)Document5 pagesPickett v. United States, 216 U.S. 456 (1910)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet