Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Preliminary Evaluation of A "Formulation-Driven Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self-Help (FCBT-GSH) " For Crisis and Transitional Case Management Clients

Preliminary Evaluation of A "Formulation-Driven Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self-Help (FCBT-GSH) " For Crisis and Transitional Case Management Clients

Uploaded by

Roland DeschainCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Discussion QuestionsDocument60 pagesDiscussion QuestionsUmar Gondal100% (1)

- Class V Social India Wins Freedom WRKSHT 2015 16Document3 pagesClass V Social India Wins Freedom WRKSHT 2015 16rahul.mishra88% (8)

- A Systematic Review of The Neural Bases of Psychotherapy For Anxiety and Related DisordersDocument1 pageA Systematic Review of The Neural Bases of Psychotherapy For Anxiety and Related DisordersRoland DeschainNo ratings yet

- Positive Psychology and Physical HealthDocument1 pagePositive Psychology and Physical HealthStephen CochraneNo ratings yet

- Lazar Meditation StudyDocument1 pageLazar Meditation Studyapi-521054554No ratings yet

- The Challenges of Implementation of Clinical Governance in Iran: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative StuDocument2 pagesThe Challenges of Implementation of Clinical Governance in Iran: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative StusunnyNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Hospital Graduation Project - BehanceDocument1 pagePsychiatric Hospital Graduation Project - BehanceCao Phuc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Https - WWW - Ncbi - NLM - Nih - Gov PMC Articles PMC5396830Document14 pagesHttps - WWW - Ncbi - NLM - Nih - Gov PMC Articles PMC5396830dori sanchezNo ratings yet

- Creswell 2017Document28 pagesCreswell 2017290971No ratings yet

- KONSELING DAN PSIKOTERAPI PROFESIONAL - Karni - Jurnal Ilmiah Syi'arDocument2 pagesKONSELING DAN PSIKOTERAPI PROFESIONAL - Karni - Jurnal Ilmiah Syi'arSST KNo ratings yet

- Animal-Assisted Intervention in Dementia: Effects On Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and On Caregivers' Distress PerceptionsDocument8 pagesAnimal-Assisted Intervention in Dementia: Effects On Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and On Caregivers' Distress PerceptionsFelipe FookNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Patient H.M. For Neuroscience: Advanced Journal List HelpDocument7 pagesThe Legacy of Patient H.M. For Neuroscience: Advanced Journal List HelpMarcus SouzaNo ratings yet

- Mindsight Approach To Well-Being - Comprehensive Course OutlineDocument33 pagesMindsight Approach To Well-Being - Comprehensive Course Outlinetccore100% (1)

- Diaframma e SNCDocument1 pageDiaframma e SNCRoberta ManfrediNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Burnout in Emergency Medicine PhysiciansDocument7 pagesMedicine: Burnout in Emergency Medicine PhysiciansJaíza DiasNo ratings yet

- EFPT Psychotherapy GuidebookDocument63 pagesEFPT Psychotherapy GuidebookChadeur EnsyantNo ratings yet

- Annals of General PsychiatryDocument1 pageAnnals of General PsychiatryParisha IchaNo ratings yet

- Effect 5-Weeks Pre-Season Training With Small-Sided Game in RSA According To Physical FitnessDocument9 pagesEffect 5-Weeks Pre-Season Training With Small-Sided Game in RSA According To Physical Fitnessimededdine boutabbaNo ratings yet

- DSGSDFGDocument1 pageDSGSDFGCao Phuc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Does Opening A Supermarket in A Food Desert Change The Food EnvironmentDocument1 pageDoes Opening A Supermarket in A Food Desert Change The Food EnvironmentKurt HutchinsonNo ratings yet

- Sedation in Neurocritical Patients: Is It Useful?: ReviewDocument7 pagesSedation in Neurocritical Patients: Is It Useful?: ReviewAditiaPLNo ratings yet

- Kudesia - 2013 - Mindfulness at WorkDocument1 pageKudesia - 2013 - Mindfulness at WorkTheLeadershipYogaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Wearing N95 and Surgical FacemasksDocument2 pagesEffects of Wearing N95 and Surgical FacemasksamacmanNo ratings yet

- Efklides, A. (2008) - Metacognition. European Psychologist, 13 (4), 277-287. Doi 10.1027 1016-9040.13.4.277Document11 pagesEfklides, A. (2008) - Metacognition. European Psychologist, 13 (4), 277-287. Doi 10.1027 1016-9040.13.4.277Eduardo GomezNo ratings yet

- CBT WorkbookDocument32 pagesCBT Workbooksoheilesm45693% (30)

- Forstmann 2016 Sequential Sampling Models in CogniDocument28 pagesForstmann 2016 Sequential Sampling Models in CogniDeissy Milena Garcia GarciaNo ratings yet

- Study On Bhasma Kalpana With Special Reference To The Preparation ofDocument6 pagesStudy On Bhasma Kalpana With Special Reference To The Preparation ofChandanaNo ratings yet

- Davidson PDFDocument82 pagesDavidson PDFHelio JinkeNo ratings yet

- Integrating Evidence-Supported Psychotherapy Principles in Mental Health Case Management: A Capacity-Building PilotDocument8 pagesIntegrating Evidence-Supported Psychotherapy Principles in Mental Health Case Management: A Capacity-Building PilotMia ValdesNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For BPDDocument5 pagesPsychotherapy For BPDJuanaNo ratings yet

- SeDocument38 pagesSeamad90No ratings yet

- Androgen Receptor Inhibitors For Treating Acne Vulgaris - CCIDDocument1 pageAndrogen Receptor Inhibitors For Treating Acne Vulgaris - CCIDArnold BlackNo ratings yet

- Brief Psychosocial InterventionDocument31 pagesBrief Psychosocial InterventionSusana CamposNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Cognitive Rehabilitation Using.47Document7 pagesAn Integrative Cognitive Rehabilitation Using.47Schier HornNo ratings yet

- 14 - Therapies PharmacyDocument5 pages14 - Therapies Pharmacymansourmona087No ratings yet

- (TEXTO 1) Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria - Cognitive Therapy - Foundations, Conceptual Models, Applications and ResearchDocument14 pages(TEXTO 1) Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria - Cognitive Therapy - Foundations, Conceptual Models, Applications and ResearchRonaldo LauxNo ratings yet

- Kelloway 2023 Mental Health in The WorkplaceDocument27 pagesKelloway 2023 Mental Health in The WorkplaceMustafizur Rahman Deputy ManagerNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For Borderline Personality Disorder: PsychiatryDocument4 pagesPsychotherapy For Borderline Personality Disorder: PsychiatryAnonymous 75M6uB3OwNo ratings yet

- Functional Neuroanatomy of Meditation (78 Functional Neuroimaging Investigations) - Kieran C.R. Fox, 2016 (21p)Document21 pagesFunctional Neuroanatomy of Meditation (78 Functional Neuroimaging Investigations) - Kieran C.R. Fox, 2016 (21p)Huyentrang VuNo ratings yet

- Studi Psikologi Indigenous Konsep Bahasa CintaDocument24 pagesStudi Psikologi Indigenous Konsep Bahasa Cintaacek ariefNo ratings yet

- Hu 2015Document30 pagesHu 2015MARIA MONTSERRAT SOMOZA MONCADANo ratings yet

- Neuroscience For Coaches Brann en 33210Document5 pagesNeuroscience For Coaches Brann en 33210Deep MannNo ratings yet

- A Roadmap TO Psychiatric ResidencyDocument21 pagesA Roadmap TO Psychiatric Residencycatalin_ilie_5No ratings yet

- Doing Daily Life How Occupational Therapy Can Inform PsychiatricRehabilitation PracticeDocument7 pagesDoing Daily Life How Occupational Therapy Can Inform PsychiatricRehabilitation PracticePaula FariaNo ratings yet

- Week 3Document7 pagesWeek 3Dalya MohanNo ratings yet

- Minerva Anestesiol 2017 GruenewaldDocument15 pagesMinerva Anestesiol 2017 GruenewaldMarjorie Lisseth Calderón LozanoNo ratings yet

- Neuro Imaging in PsychiatryDocument8 pagesNeuro Imaging in PsychiatryEva Paula Badillo SantosNo ratings yet

- Journal of Psychotherapy IntegrationDocument16 pagesJournal of Psychotherapy IntegrationJulio César Cristancho GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Role of Psilocybin in The Treatment of Depression: Ananya Mahapatra and Rishi GuptaDocument3 pagesRole of Psilocybin in The Treatment of Depression: Ananya Mahapatra and Rishi GuptaRavennaNo ratings yet

- Mood Stabilizer and Antipsychotic Medication Coprescribing (Polypharmacy)Document1 pageMood Stabilizer and Antipsychotic Medication Coprescribing (Polypharmacy)Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of and Risk Factors For Anxiety After.2Document11 pagesPrevalence of and Risk Factors For Anxiety After.2misbah007No ratings yet

- Thought PDFDocument1 pageThought PDFsai calderNo ratings yet

- Time table-PGDM Trimester-I Batch 23-25Document6 pagesTime table-PGDM Trimester-I Batch 23-25Sushovan ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Intervencion 2.Document18 pagesIntervencion 2.Cristina MPNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy JPCPDocument4 pagesOccupational Therapy JPCPHanin MaharNo ratings yet

- 2023 35777 001Document53 pages2023 35777 001Paula Manalo-SuliguinNo ratings yet

- Supportive-Expressive Dynamic Psychotherapy: April 2017Document10 pagesSupportive-Expressive Dynamic Psychotherapy: April 2017MauroNo ratings yet

- Model-Based Cognitive Neuroscience Approaches To Computational Psychiatry: Clustering and ClassificationDocument22 pagesModel-Based Cognitive Neuroscience Approaches To Computational Psychiatry: Clustering and ClassificationabsNo ratings yet

- CBT Course Supporting NotesDocument20 pagesCBT Course Supporting NotesSushma KaushikNo ratings yet

- Applied Kinesiology: Distinctions in Its Definition and InterpretationDocument3 pagesApplied Kinesiology: Distinctions in Its Definition and InterpretationmoiNo ratings yet

- John Read Middle School - Class of 2011Document1 pageJohn Read Middle School - Class of 2011Hersam AcornNo ratings yet

- Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam UniversityDocument12 pagesJatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam UniversityAl-Muzahid EmuNo ratings yet

- 55+ Easy and Mostly Free Ways To Market Your BookDocument10 pages55+ Easy and Mostly Free Ways To Market Your BookSoulGate MediaNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Issues in Hr-1Document54 pagesCross Cultural Issues in Hr-1ANKIT MAANNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Managerial Accounting 9th Edition CrossonDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Managerial Accounting 9th Edition Crossonfloatsedlitzww63v100% (53)

- Gess SC 8 Course OutlineDocument4 pagesGess SC 8 Course Outlineapi-264733993No ratings yet

- Trueblue Activitysheets MarchDocument31 pagesTrueblue Activitysheets MarchS TANCREDNo ratings yet

- DUE 2016 Registration Form1Document1 pageDUE 2016 Registration Form1Mananga destaingNo ratings yet

- Jalova May 16 Monthly AchievementsDocument3 pagesJalova May 16 Monthly AchievementsGVI FieldNo ratings yet

- AffidavitsDocument36 pagesAffidavitsKarexa Skye LeganoNo ratings yet

- Special Leave Petition Format For SC of IndiaDocument8 pagesSpecial Leave Petition Format For SC of IndiaRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- Alejandro Vs PEPITODocument3 pagesAlejandro Vs PEPITONissi JonnaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Foundations of Nursing: TheoristsDocument2 pagesTheoretical Foundations of Nursing: TheoristsDenise CalderonNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Financial Statement AnalysisDocument37 pagesAn Overview of Financial Statement AnalysisShynara MuzapbarovaNo ratings yet

- MilleniumDocument2 pagesMilleniumrahul_dua111100% (1)

- Eugenio Vs DrilonDocument2 pagesEugenio Vs Drilonkei takiNo ratings yet

- BFCG-LA Exec Summary v2Document1 pageBFCG-LA Exec Summary v2Tim DowdingNo ratings yet

- Fil-Estate Properties Vs Spouses Go (GR No 185798, 13 Jan 2014)Document3 pagesFil-Estate Properties Vs Spouses Go (GR No 185798, 13 Jan 2014)Wilfred MartinezNo ratings yet

- Lancaster County Warrant SweepDocument2 pagesLancaster County Warrant SweepPennLiveNo ratings yet

- ICTAD Specifications For WorksDocument12 pagesICTAD Specifications For Workssanojani50% (8)

- Ducation: Indian School of Business, PGP in Management: Intended Majors in Strategy & FinanceDocument1 pageDucation: Indian School of Business, PGP in Management: Intended Majors in Strategy & FinanceSneha KhaitanNo ratings yet

- (SE) ..Case StudyDocument8 pages(SE) ..Case StudyIqra farooqNo ratings yet

- Project Management Report On Services Industry !!Document12 pagesProject Management Report On Services Industry !!Atif BlinkingstarNo ratings yet

- AR TablesDocument1 pageAR TablesrajeshmunagalaNo ratings yet

- AggressionDocument9 pagesAggressionapi-645961517No ratings yet

- FC PPT MahekDocument32 pagesFC PPT MahekShreya KadamNo ratings yet

- Construction Site Inspection ReportDocument2 pagesConstruction Site Inspection ReportTomasz Bragiel100% (1)

- Guide To UK State PensionsDocument87 pagesGuide To UK State PensionsslyxdexicNo ratings yet

Preliminary Evaluation of A "Formulation-Driven Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self-Help (FCBT-GSH) " For Crisis and Transitional Case Management Clients

Preliminary Evaluation of A "Formulation-Driven Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self-Help (FCBT-GSH) " For Crisis and Transitional Case Management Clients

Uploaded by

Roland DeschainOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Preliminary Evaluation of A "Formulation-Driven Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self-Help (FCBT-GSH) " For Crisis and Transitional Case Management Clients

Preliminary Evaluation of A "Formulation-Driven Cognitive Behavioral Guided Self-Help (FCBT-GSH) " For Crisis and Transitional Case Management Clients

Uploaded by

Roland DeschainCopyright:

Available Formats

Resources How To Sign in to NCBI

PMC Search

US National Library of Medicine

National Institutes of Health

Advanced Journal list Help

Journal List Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat v.13; 2017 PMC5354537

Formats:

Article | PubReader | PDF (285K) | Cite

Share

Facebook Twitter Google+

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017; 13: 769–774. PMCID: PMC5354537

Published online 2017 Mar 10. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S127567 PMID: 28331328

Save items

Add to Favorites

Preliminary evaluation of a “formulation-driven cognitive behavioral

guided self-help (fCBT-GSH)” for crisis and transitional case

management clients Similar articles in PubMed

Cognitive Behavior Therapy for psychosis based Guided Self-help

Farooq Naeem,1,2 Rupinder K Johal,1 Claire Mckenna,1 Olivia Calancie,1 Tariq Munshi,1,2 Tariq Hassan,1 (CBTp-GSH) delivered by frontline mental health

[Schizophr

professionals:

Res. 2016]

Amina Nasar,3 and Muhammad Ayub1

Low-Intensity Cognitive Behavioural Therapy-Based Music Group

▸ Author information ▸ Copyright and License information Disclaimer (CBT-Music) for the Treatment of Symptoms

[Behav Cogn

of Anxiety

Psychother.

and 2018]

Culturally adapted trauma-focused CBT-based guided self-help

(CatCBT GSH) for female victims of

[Behav

domestic

Cognviolence

Psychother.

in 2021]

This article has been cited by other articles in PMC.

Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural

therapy (self-help) for anxiety[Cochrane

disorders in

Database

adults. Syst Rev. 2013]

Abstract Go to:

[A group cognitive behavioral intervention for people registered in

supported employment programs: CBT-SE]. [Encephale. 2014]

Background

See reviews...

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is found to be effective for common mental disorders and has been

See all...

delivered in self-help and guided self-help formats. Crisis and transitional case management (TCM)

services play a vital role in managing clients in acute mental health crises. It is, therefore, an appropriate

setting to try CBT in guided self-help format. Cited by other articles in PMC

Efficacy of music-based cognitive behavior therapy on the

Methods management of test-taking behavior of children in [Medicine.

basic science

2020]

This was a preliminary evaluation of a formulation-driven cognitive behavioral guided self-help. Thirty-six Effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy with music therapy in

reducing physics test anxiety among students as measured

[Medicine.by

2020]

(36) consenting participants with a diagnosis of nonpsychotic illness, attending crisis and the TCM services

in Kingston, Canada, were recruited in this study. They were randomly assigned to the guided self-help See all...

plus treatment as usual (TAU) (treatment group) or to TAU alone (control group). The intervention was

delivered over 8–12 weeks. Assessments were completed at baseline and 3 months after baseline. The

Links

primary outcome was a reduction in general psychopathology, and this was done using Clinical Outcomes

MedGen

in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure. The secondary outcomes included a reduction in depression,

measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and reduction in disability, measured using the PubMed

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

Findings Recent Activity

Turn Off Clear

Participants in the treatment group showed statistically significant improvement in overall Preliminary evaluation of a “formulation-driven cognitive

psychopathology (P<0.005), anxiety and depression (P<0.005), and disability (P<0.005) at the end of the behavioral guided self...

trial compared with TAU group. A conceptual comparison of family-based treatment and

enhanced cognitive behavio...

Conclusion

A systematic review of the neural bases of psychotherapy for

A formulation-driven cognitive behavioral guided self-help was feasible for the crisis and TCM clients and anxiety and related...

can be effective in improving mental health, when compared with TAU. This is the first report of a trial of See more...

guided self-help for clients attending crisis and TCM services.

Keywords: mental health crisis, transitional case management, cognitive behavior therapy, guided, self

help

Introduction Go to:

Crisis services are now a well-established part of the mental health systems in North America.1 These A national survey of mobile crisis services and their evaluation.

[Psychiatr Serv. 1995]

programs have been found to be successful in improving access to mental health system for those with

Empirically assessing the impact of mobile crisis capacity on

acute emotional or mental health problems and to help persons deal with a crisis. Crisis services are also a

state hospital admissions. [Community Ment Health J. 1990]

cost-effective way of reducing the costs of psychiatric hospitalization, as well as social costs, by providing

professional assessment and crisis intervention in the community.2 There is evidence to suggest that the

crisis services are associated with improved client satisfaction.2

Interestingly, most of the published research in this area is nearly two decades old.3 A recent Cochrane Mobile crisis team intervention to enhance linkage of discharged

suicidal emergency department patients[Acad Emerg Med. 2010]

to outpatient

review reported that by supporting clients at their homes, the crisis teams can reduce repeat admissions to

hospital. Crisis intervention also reduced family burden, and this was preferred by both clients and their

families.4 However, the same review found no differences in mortality. The authors reported numerous

methodological problems with the studies in this area. There is a lack of interventions in this area; for

example, another Cochrane review failed to identify the impact of crisis intervention services for borderline

personality disorders.5

Crisis teams in different parts of the world operate differently. In Canada, the crisis teams work closely

with the transitional case management (TCM) teams. Crisis teams in some countries work closely with

home treatment teams. A number of investigations have also reported reduced length of in-client stay

following introduction of crisis resolution and home treatment (CRHT). These studies suggest that in

addition to reduced admissions, these teams reduce the duration of inpatient admissions and rates of

detention. Using these services can catalyze a more efficient use of in-client care.5

The CRHT, and TCM services offer an opportunity to provide evidence-based psychosocial interventions Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis.

[J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1997]

to improve well-being further and to prevent future relapses. However, there is currently no published

literature on effective interventions within these services. Evidence-based self-help, guided self-help, and Review Self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: an

overview. [Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007]

low-intensity psychological help can be easily provided in these setups. There is sufficient evidence in the

form of meta-analyses and literature reviews to suggest that guided self-help can be as effective as the face-

to-face treatments.6,7

We, therefore, developed a “formulation-driven cognitive behavioral guided self-help (fCBT-GSH)” for

common mental health problems that can be delivered by mental health professionals working in a crisis or

TCM setting. This paper describes the preliminary evaluation of this intervention.

Methods Go to:

Study design

The study used a randomized controlled design to compare the efficacy of this fCBT-GSH plus treatment

as usual (TAU) to TAU only within crisis and TCM services. The intervention is provided by trained

mental health professionals for clients under care of the crisis and TCM service. The intervention group

received fCBT-GSH and TAU, while the control group received TAU only. The TAU consisted of routine

follow-up and care of the clients by crisis and TCM team. Both teams offer at least once a week face-to-

face contact with the clients.

Recruitment and procedure

Client participants were recruited from crisis and TCM services in Kingston, Ontario. Current clients with

a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, and other common mental health problems (using DSM-IV criteria) were

considered eligible for inclusion, except for those using alcohol or drugs excessively or with significant

cognitive impairment and those who were experiencing acute psychotic symptoms. Staff psychiatrists and

case managers identified eligible clients.

Clients selected for the study were provided with brief information about the study. Those who met the

criteria and consented in writing were then asked to join the study and were randomly allocated to one arm

of the trial.

The Queen’s University Health Sciences & Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board approved

this study.

Participants

Randomization was performed using www.randomization.com. Out of 36 clients who completed the

assessment phase and were subsequently randomized, eight dropped out of the study. Of these, three

participants dropped out of the intervention group, and five from the control group.

Primary assessment measure

Psychopathology was measured using the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure

(CORE-OM) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Disability was measured using the

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0). All the assessments were

carried out at the baseline and after 3 months. Demographic and other details were measured using a form

specially designed for the study.

The CORE-OM8 is a self-report measure tapping four domains, including a risk to others and risk to self.

The scale was found to have good reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change.8 Each of the items (eg, “I

have felt terribly alone and isolated”) is scored on a scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Most or all of the time).

It has been used in previous research to measure emotional disturbance in service settings delivering

psychological interventions in primary and secondary care.

Secondary assessment measures

HADS HADS9 is a rating scale comprised of 14 items, seven of which are designed to measure anxiety The hospital anxiety and depression scale.

[Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983]

(HADS-A), and seven for depression (HADS-D). The HADS is a widely used measure of anxiety and

depression, and its psychometric properties have been described in detail.10 Each of the items in HADS is Review The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression

Scale. An updated literature review. [J Psychosom Res. 2002]

scored on a four-point scale from 0 to 3. The item scores are summed to provide subscale scores on the

HADS-D and the HADS-A, which may range between 0 and 21. Studies most commonly employ a cut-

point of ≥8 (eight and above) for each of the constituent subscales, as suggested by its authors, to indicate

probable caseness.

WHODAS 2.0 WHODAS 2.011 was developed by the WHO to measure disability due to physical and Developing the World Health Organization Disability

Assessment Schedule 2.0. [Bull World Health Organ. 2010]

psychological problems. The scale was tested across the globe and was found to be both reliable and

valid.11 Participants are asked to indicate how much difficulty they had in completing a certain task (eg,

“Remembering to do important things”) in the last 30 days on a scale from 1 (None) to 5 (Extreme or

cannot do). This instrument has been used extensively in research settings.

Therapists and treatment fidelity A third-year psychiatry resident physician, two undergraduate

psychology students, social workers, and other crisis team members, who had been trained in delivering

CBT intervention, provided fCBT-GSH to the participants. Health professionals received training in using

this intervention. This half-day training focused on the five basic areas CBT formulation. They were also

educated on techniques described in handouts, eg, problem solving, behavioral activation, and use of

thought diaries to recognize, challenge, and create alternative thoughts. They were not trained in delivering

therapy as this intervention only required them to facilitate use of self-help. Standard aspects of cognitive

therapy, different modules of “fCBT-GSH” manual, as well as home work assignments were also

discussed. They also received weekly supervision. These meetings ensured adherence to the treatment

protocol. During these meetings, sessions were reviewed and cases were discussed. Health professionals

shared the formulation, barriers to home work, and difficulties in following handouts. These sessions

typically lasted for 1–1.5 hours.

The intervention Go to:

There is sufficient evidence to suggest that self-help and guided self-help can be effective in helping mental Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis.

and emotional health problems,6,7 especially for anxiety and eating disorders.12,13 “Self-help” can be [J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1997]

defined as: See more ...

[…] a therapeutic intervention that is based on a sound theoretical background, that uses therapeutic

principles from an evidence-based intervention, and is administered through a “media” that does not

involve direct contact with another person.13

The “guided self-help” can be defined as “self-help that involves facilitation of the self-help by a lay

person (eg, a carer) or by a health professional with minimum direct contact (<25% of the normal therapy

session time)”. Contact between the clients and the other person can take place through face-to-face

contact, by telephone, by email, or any other communication method.14

This fCBT-GSH was developed by FN, who has previously adapted CBT for different cultures and A multicentre randomised controlled trial of a carer supervised

[J Affect

forDisord. 2014]

settings.15–18 The intervention consisted of 24 handouts that could be flexibly used by a health culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) based self-help depression

Brief culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CaCBTp): A

professional. The intervention focused on psychoeducation, symptom management, changing negative

[Schizophr

randomized controlled trial from a low income country.Res. 2015]

thinking, behavioral activation, problem solving, improving relationships, and communication skills. The

intervention consisted of essential worksheets (changing negative thinking and information sharing) plus

worksheets that can be used flexibly according to a therapy plan that was driven on the basis of individuals’

particular needs. Therapy plan was based on a formulation. The intervention was delivered flexibly in that

different sessions could be conducted by various team members, based on initial therapy plan. Where

possible, carers were engaged in this process. A typical session consisted of feedback from the last week, a

discussion of barriers, and information about the next handout. Table 1 provides further details.

Table 1

Salient features of the intervention

1. Formulation-driven guided self-help, based on CBT, addressing common mental disorders.

2. An individual therapy plan prepared based on formulation and handouts given weekly using guided self-help.

3. Given flexibly to clients with a variety of problems. Guided self-help provided by different members of the team

and not only by one dedicated therapist/worker.

4. Intervention consisted of 24 handouts that are given over 6–9 sessions per client on a weekly basis.

5. Intervention focuses on psychoeducation, symptom management, changing negative thinking, behavioral

activation, problem solving, and improving relationships and communication skills.

6. Carers encouraged to be involved in helping the clients with therapy.

7. Team members provided with detailed guidelines in using the intervention, received half-day training in using

intervention, and also supervised regularly.

Abbreviation: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

Data entry and analysis

Analyses were carried out using SPSSv.22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). SPSS frequency and

descriptive commands were used to measure descriptive statistics. SPSS explore command was used to

measure normality of the data using histograms and Kolmogorov–Smirnorov tests. Comparisons between

the groups were made on an intention-to-treat basis. For an intention-to-treat analysis, participants were

included in the groups to which they were randomized, regardless of whether they received the treatment

allocated to them or not. All continuous variables (eg, the baseline questionnaire scores) were compared

using paired t-tests, and categorical variables (eg, gender) were compared using χ2 tests. Differences in

baseline and follow-up questionnaire scores between the two groups at the end of the intervention were

compared using a linear regression.

Results Go to:

A total of 63 clients were referred for the intervention. Out of 48 clients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria

during the initial screening, 8 were excluded before baseline interviews were conducted, 4 refused

immediately before baseline interview, and the remaining 36 were randomized to two groups. A total of 18

participants were randomized to the treatment group and 18 to the control group. The mean age of the

participants was 34.6 (11.1). Of the 36 participants, 20 (55.6%) were female and 16 (44.4%) were male; 24

(66.7%) were single, 6 (16.7%) married, and 6 (16.7%) were divorced/widowed or widower. In terms of

psychopathology, 3 (8.3%) participants had a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, 3 (8.3%) of depression, 5

(13.9%) of post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety 9 (25.0%), mixed anxiety and depression 8

(22.2%), and panic disorder with agoraphobia 8 (22.2%). Table 2 provides additional differences on client

variables, and Table 3 provides additional differences in psychopathology of the overall sample and

between the intervention and control groups at baseline.

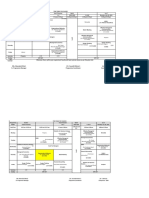

Table 2

Differences in client variables between the intervention and the control groups at baseline

Client variables Total Intervention group (fg-CBT + Control group (TAU) P-

sample TAU) (n=18) (n=18) value

(N=36)

M (SD) M (SD)

Age (years) 38.6 (11.1) 31.2 (7.78) 0.092

Frequency Frequency % Frequency %

Gender 0.502

Female 20 9 45 11 55

Male 16 9 56 7 43.8

Ethnic group 0.261

White 32 16 50 16 50

Black 1 0 0 1 100

Asian 1 0 0 1 100

Other 2 2 100 0 0

Relationship status 0.174

Single 24 11 45.8 13 54.2

Married/common law 6 2 33.3 4 66.7

Divorced 6 5 83.3 1 16.7

Education 0.927

High school 9 4 44.4 5 55.6

College 25 13 52 12 48

University 2 1 50 1 50

Employment 0.505

Employed 18 8 44.4 10 55.6

Unemployed 18 10 55.6 8 44.4

Family history of mental 0.700

illness

Yes 27 13 48.1 14 51.9

No 9 5 55 6 4 44 4

Open in a separate window

Abbreviations: fg-CBT, formulation-guided cognitive behavioral therapy; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as

usual.

Table 3

Differences in psychopathology between the intervention and the control groups at baseline

Psychopathology Total Intervention group (fg-CBT + Control group (TAU) P-

sample TAU) (n=18) (n=18) value

(N=36)

Frequency % Frequency %

Diagnosis 0.283

Anxiety disorder 3 0 0.0 3 16.7

Depression 3 2 11.1 1 5.6

PTSD 5 4 22.2 1 5.6

Social anxiety 9 4 22.2 5 27.8

Mixed anxiety and 3 16.7 5 27.8

depression

Panic disorder with 3 16.7 5 27.8

agoraphobia

Drugs/alcohol 0.317

Yes 17 10 58.8 7 41.2

No 19 8 42.1 11 57.9

M (SD) M (SD)

CORE-OM 74.3 (19.6) 80.4 (22.4) 0.394

WHODAS 27.8 (7.5) 32.2 (9.5) 0.137

HADS-D 12.8 (4.2) 15.6 (4.4) 0.062

*

HADS-A 10.2 (3.2) 13.8 (2.6) 0.001

Note:

*P<0.01.

Abbreviations: CORE-OM, Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure; fg-CBT, formulation-

guided cognitive behavioral therapy; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: Anxiety Subscale; HADS-D,

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: Depression Subscale; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; SD, standard

deviation; TAU, treatment as usual; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

Those in treatment group showed statistically significant improvement in overall psychopathology (CORE)

(P<0.005), anxiety and depression (HADS) (P<0.005), and disability (WHODAS 2.0) (P<0.005) at the end

of the trial compared with those in TAU group. Table 4 describes these details.

Table 4

Linear regression analyses of differences between treatment and control groups, uncontrolled and

controlled for initial differences

Clinical TAU Mean Intervention group Differences uncontrolled for Differences controlled for

variables (SD) (SD) baseline baseline

Mean difference P-value Mean difference P-value

(CI) (CI)

CORE-OM 64.8 (25.2) 35.7 (33.2) −29.06 (−49.03, 0.006* 30.5 (10.3, 50.7) 0.004*

−9.08)

* *

WHODAS 2.0 24.6 (12.7) 11.8333 (11.3) −12.72 (−20.9, 0.003 13.135 (4.6, 21.7) 0.004

−4.6)

HADS-D 9.17 (5.3) 4.4 (4.8) −4.8 (−8.2, −1.4) 0.008* 4.8 (1.07, 8.4) 0.013**

* *

HADS-A 9.3 (3.6) 3.9 (4.8) −5.3 (−8.2, −2.4) 0.001 6.04 (2.6, 9.5) 0.001

Notes: A reduction in scores indicates improvement.

*P<0.01,

**P<0.05.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CORE-OM, Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure;

HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: Anxiety Subscale; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression

Scale: Depression Subscale; SD, standard deviation; TAU, treatment as usual; WHODAS, World Health Organization

Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

Discussion Go to:

This study shows that a fCBT-GSH is feasible for crisis and TCM clients and can be potentially effective in

improving mental health when compared with only TAU. This is the first report of an evaluation of guided

self-help for clients attending crisis and TCM services. This is also the first study in which a cognitive

behavioral guided self-help was delivered on the basis of the formulation.

This guided self-help was driven by formulation. Health professionals started by sharing the formulation Review The treatment utility of assessment. A functional

approach to evaluating assessment quality. [Am Psychol. 1987]

with clients, and then developing a shared therapy plan. The case formulation is a vital element of CBT,

along with assessment and intervention. It is considered to be the foundation on which therapeutic

intervention is built. A good formulation is the hypothesis about the causes of the problems and why the

problem persists.19 The formulation guides the treatment. It is, however, an ongoing process and can be

done at various levels, from individual symptom to disorder.20 The formulation is the only way therapy can

be individualized and provides an empirical approach to hypothesis testing.21 Traditionally, however, self-

help and guided self-help do not use a formulation-based approach, and mainly consist of a fixed manual.

We therefore decided to use a formulation that was shared and agreed between the health professional and

the clients based on the client’s specific needs. The therapy plan was agreed on the basis of this

formulation. This helped us reach some level of an individualized approach.

The health professionals working with crisis and TCM services could use the current findings in several

ways. This study shows that it is feasible to deliver CBT based self help and guided self help through the

frontline clinicians. A formulation can help clients understand their problems in an easy to understandable

language by linking their thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, and behaviors with the events in their

lives. Such evidence-based interventions may motivate clients and give them hope and may also increase

the clinician’s feelings of being effective in providing clients with an intervention. It is also highly likely

that the health professionals will feel empowered and be more effective in helping their clients by having a

better understanding of their problem as a result of the positive responses from patients.

Limitations Go to:

Several study limitations are noteworthy. This study recruited a small number of participants due to limited

resources. Although these results raise hope that such low-cost interventions can become part of the routine

care, caution is warranted as no prior power calculations were conducted for this pilot study. This is a new

intervention, and ideally data on patient fidelity to different components of the intervention and its relation

to treatment outcomes should have been conducted. This is especially important since a formulation was

the basis of this guided self-help. However, this was not possible due to limited resources. Future research

should test this intervention in well-designed studies with adequate sample sizes.

Conclusion Go to:

This small scale study shows that CBT based self-help and guided self-help can be delivered by the front

line clinicians working in crisis and TCM services. The intervention was found to be effective in reducing

psychological distress and disability. This is however, only a small scale pilot study and there is a need to

conduct large scale studies with improved methodology.

Acknowledgments Go to:

The authors wish to thank the Crisis and the TCM Teams in Kingston, ON, Canada. While Dawn Godfrey

and Chris Trimmer helped with delivery of intervention Rob Yeo, Stacey Dowling, Tania Laverty, and

Ashley Kehoe from the Addiction & Mental Health Services – Kingston Frontenac Lennox & Addington

(AMHS-KFLA) provided practical support throughout the study. Additionally, the authors thank Krista

Robertson and Hannah Taalman of the Research Unit, at the Department of Psychiatry, Queen’s University,

Kingston, ON, Canada.

Footnotes Go to:

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References Go to:

1. Geller JL, Fisher WH, McDermeit M. A national survey of mobile crisis services and their evaluation.

Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46(9):893–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Fisher WH, Geller JL, Wirth-Cauchon J. Empirically assessing the impact of mobile crisis capacity on

state hospital admissions. Community Ment Health J. 1990;26(3):245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Currier GW, Fisher SG, Caine ED. Mobile crisis team intervention to enhance linkage of discharged

suicidal emergency department patients to outpatient psychiatric services: a randomized controlled trial.

Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(1):36–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Murphy S, Irving CB, Adams CE, Driver R. Crisis intervention for people with severe mental illnesses.

In: The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John

Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. [Accessed October 25, 2016]. [cited June 13, 2015]. Available from:

http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD001087.pub4. [Google Scholar]

5. Borschmann R, Henderson C, Hogg J, Phillips R, Moran P. Crisis interventions for people with

borderline personality disorder. In: The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. [Accessed October 25, 2016]. [cited June 13,

2015]. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009353.pub2. [Google Scholar]

6. Cuijpers P. Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry.

1997;28(2):139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Cuijpers P, Schuurmans J. Self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: an overview. Curr Psychiatry

Rep. 2007;9(4):284–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Evans C, Mellor-Clark J, Margison F, et al. CORE: clinical outcomes in routine evaluation. J Ment

Health. 2000;9(3):247–255. [Google Scholar]

9. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand.

1983;67(6):361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression

scale. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, et al. Developing the World Health Organization Disability

Assessment Schedule 2.0. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(11):815–823. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[Google Scholar]

12. Mayo-Wilson E, Montgomery P. Media-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and behavioural

therapy (self-help) for anxiety disorders in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD005330.

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Perkins SSJ, Murphy RR, Schmidt UU, Williams C. Self-help and guided self-help for eating disorders.

In: The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons,

Ltd; 2006. [Accessed October 25, 2016]. [cited June 13, 2015]. Available from:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.proxy.queensu.ca/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004191.pub2/abstract.

[Google Scholar]

14. Naeem F, Xiang S, Munshi TA, Kingdon D, Farooq S. Self-help and guided self-help interventions for

schizophrenia and related disorders. In: The Cochrane Collaboration, editor. Cochrane Database of

Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015. [Accessed October 25, 2016]. [cited June 13, 2015].

Available from:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.proxy.queensu.ca/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011698/abstract.

[Google Scholar]

15. Naeem F, Sarhandi I, Gul M, et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of a carer supervised

culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) based self-help for depression in Pakistan. J Affect Disord.

2014;156:224–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Naeem F, Johal R, McKenna C, et al. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for psychosis based Guided Self-

help (CBTp-GSH) delivered by frontline mental health professionals: results of a feasibility study.

Schizophr Res. 2016;173(1–2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Naeem F, Gul M, Irfan M, et al. Brief culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) for depression: a randomized

controlled trial from Pakistan. J Affect Disord. 2015;177:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Naeem F, Saeed S, Irfan M, et al. Brief culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CaCBTp): a randomized

controlled trial from a low income country. [Accessed October 25, 2016];Schizophr Res. 2015 164(1–

3):143–148. Available from: http://www.schres-journal.com/article/S0920996415001206/abstract.

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Hayes SC, Nelson RO, Jarrett RB. The treatment utility of assessment: a functional approach to

evaluating assessment quality. Am Psychol. 1987;42(11):963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Eells TD, editor. Handbook of Psychotherapy Case Formulation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford

Press; 2011. p. 465. [Google Scholar]

21. Persons JB. Case formulation–driven psychotherapy. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2006;13(2):167–170.

[Google Scholar]

Articles from Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment are provided here courtesy of Dove Press

National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine Support Center

8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Policies and Guidelines | Contact

You might also like

- Discussion QuestionsDocument60 pagesDiscussion QuestionsUmar Gondal100% (1)

- Class V Social India Wins Freedom WRKSHT 2015 16Document3 pagesClass V Social India Wins Freedom WRKSHT 2015 16rahul.mishra88% (8)

- A Systematic Review of The Neural Bases of Psychotherapy For Anxiety and Related DisordersDocument1 pageA Systematic Review of The Neural Bases of Psychotherapy For Anxiety and Related DisordersRoland DeschainNo ratings yet

- Positive Psychology and Physical HealthDocument1 pagePositive Psychology and Physical HealthStephen CochraneNo ratings yet

- Lazar Meditation StudyDocument1 pageLazar Meditation Studyapi-521054554No ratings yet

- The Challenges of Implementation of Clinical Governance in Iran: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative StuDocument2 pagesThe Challenges of Implementation of Clinical Governance in Iran: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative StusunnyNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Hospital Graduation Project - BehanceDocument1 pagePsychiatric Hospital Graduation Project - BehanceCao Phuc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Https - WWW - Ncbi - NLM - Nih - Gov PMC Articles PMC5396830Document14 pagesHttps - WWW - Ncbi - NLM - Nih - Gov PMC Articles PMC5396830dori sanchezNo ratings yet

- Creswell 2017Document28 pagesCreswell 2017290971No ratings yet

- KONSELING DAN PSIKOTERAPI PROFESIONAL - Karni - Jurnal Ilmiah Syi'arDocument2 pagesKONSELING DAN PSIKOTERAPI PROFESIONAL - Karni - Jurnal Ilmiah Syi'arSST KNo ratings yet

- Animal-Assisted Intervention in Dementia: Effects On Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and On Caregivers' Distress PerceptionsDocument8 pagesAnimal-Assisted Intervention in Dementia: Effects On Neuropsychiatric Symptoms and On Caregivers' Distress PerceptionsFelipe FookNo ratings yet

- The Legacy of Patient H.M. For Neuroscience: Advanced Journal List HelpDocument7 pagesThe Legacy of Patient H.M. For Neuroscience: Advanced Journal List HelpMarcus SouzaNo ratings yet

- Mindsight Approach To Well-Being - Comprehensive Course OutlineDocument33 pagesMindsight Approach To Well-Being - Comprehensive Course Outlinetccore100% (1)

- Diaframma e SNCDocument1 pageDiaframma e SNCRoberta ManfrediNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Burnout in Emergency Medicine PhysiciansDocument7 pagesMedicine: Burnout in Emergency Medicine PhysiciansJaíza DiasNo ratings yet

- EFPT Psychotherapy GuidebookDocument63 pagesEFPT Psychotherapy GuidebookChadeur EnsyantNo ratings yet

- Annals of General PsychiatryDocument1 pageAnnals of General PsychiatryParisha IchaNo ratings yet

- Effect 5-Weeks Pre-Season Training With Small-Sided Game in RSA According To Physical FitnessDocument9 pagesEffect 5-Weeks Pre-Season Training With Small-Sided Game in RSA According To Physical Fitnessimededdine boutabbaNo ratings yet

- DSGSDFGDocument1 pageDSGSDFGCao Phuc NguyenNo ratings yet

- Does Opening A Supermarket in A Food Desert Change The Food EnvironmentDocument1 pageDoes Opening A Supermarket in A Food Desert Change The Food EnvironmentKurt HutchinsonNo ratings yet

- Sedation in Neurocritical Patients: Is It Useful?: ReviewDocument7 pagesSedation in Neurocritical Patients: Is It Useful?: ReviewAditiaPLNo ratings yet

- Kudesia - 2013 - Mindfulness at WorkDocument1 pageKudesia - 2013 - Mindfulness at WorkTheLeadershipYogaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Wearing N95 and Surgical FacemasksDocument2 pagesEffects of Wearing N95 and Surgical FacemasksamacmanNo ratings yet

- Efklides, A. (2008) - Metacognition. European Psychologist, 13 (4), 277-287. Doi 10.1027 1016-9040.13.4.277Document11 pagesEfklides, A. (2008) - Metacognition. European Psychologist, 13 (4), 277-287. Doi 10.1027 1016-9040.13.4.277Eduardo GomezNo ratings yet

- CBT WorkbookDocument32 pagesCBT Workbooksoheilesm45693% (30)

- Forstmann 2016 Sequential Sampling Models in CogniDocument28 pagesForstmann 2016 Sequential Sampling Models in CogniDeissy Milena Garcia GarciaNo ratings yet

- Study On Bhasma Kalpana With Special Reference To The Preparation ofDocument6 pagesStudy On Bhasma Kalpana With Special Reference To The Preparation ofChandanaNo ratings yet

- Davidson PDFDocument82 pagesDavidson PDFHelio JinkeNo ratings yet

- Integrating Evidence-Supported Psychotherapy Principles in Mental Health Case Management: A Capacity-Building PilotDocument8 pagesIntegrating Evidence-Supported Psychotherapy Principles in Mental Health Case Management: A Capacity-Building PilotMia ValdesNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For BPDDocument5 pagesPsychotherapy For BPDJuanaNo ratings yet

- SeDocument38 pagesSeamad90No ratings yet

- Androgen Receptor Inhibitors For Treating Acne Vulgaris - CCIDDocument1 pageAndrogen Receptor Inhibitors For Treating Acne Vulgaris - CCIDArnold BlackNo ratings yet

- Brief Psychosocial InterventionDocument31 pagesBrief Psychosocial InterventionSusana CamposNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Cognitive Rehabilitation Using.47Document7 pagesAn Integrative Cognitive Rehabilitation Using.47Schier HornNo ratings yet

- 14 - Therapies PharmacyDocument5 pages14 - Therapies Pharmacymansourmona087No ratings yet

- (TEXTO 1) Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria - Cognitive Therapy - Foundations, Conceptual Models, Applications and ResearchDocument14 pages(TEXTO 1) Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria - Cognitive Therapy - Foundations, Conceptual Models, Applications and ResearchRonaldo LauxNo ratings yet

- Kelloway 2023 Mental Health in The WorkplaceDocument27 pagesKelloway 2023 Mental Health in The WorkplaceMustafizur Rahman Deputy ManagerNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For Borderline Personality Disorder: PsychiatryDocument4 pagesPsychotherapy For Borderline Personality Disorder: PsychiatryAnonymous 75M6uB3OwNo ratings yet

- Functional Neuroanatomy of Meditation (78 Functional Neuroimaging Investigations) - Kieran C.R. Fox, 2016 (21p)Document21 pagesFunctional Neuroanatomy of Meditation (78 Functional Neuroimaging Investigations) - Kieran C.R. Fox, 2016 (21p)Huyentrang VuNo ratings yet

- Studi Psikologi Indigenous Konsep Bahasa CintaDocument24 pagesStudi Psikologi Indigenous Konsep Bahasa Cintaacek ariefNo ratings yet

- Hu 2015Document30 pagesHu 2015MARIA MONTSERRAT SOMOZA MONCADANo ratings yet

- Neuroscience For Coaches Brann en 33210Document5 pagesNeuroscience For Coaches Brann en 33210Deep MannNo ratings yet

- A Roadmap TO Psychiatric ResidencyDocument21 pagesA Roadmap TO Psychiatric Residencycatalin_ilie_5No ratings yet

- Doing Daily Life How Occupational Therapy Can Inform PsychiatricRehabilitation PracticeDocument7 pagesDoing Daily Life How Occupational Therapy Can Inform PsychiatricRehabilitation PracticePaula FariaNo ratings yet

- Week 3Document7 pagesWeek 3Dalya MohanNo ratings yet

- Minerva Anestesiol 2017 GruenewaldDocument15 pagesMinerva Anestesiol 2017 GruenewaldMarjorie Lisseth Calderón LozanoNo ratings yet

- Neuro Imaging in PsychiatryDocument8 pagesNeuro Imaging in PsychiatryEva Paula Badillo SantosNo ratings yet

- Journal of Psychotherapy IntegrationDocument16 pagesJournal of Psychotherapy IntegrationJulio César Cristancho GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Role of Psilocybin in The Treatment of Depression: Ananya Mahapatra and Rishi GuptaDocument3 pagesRole of Psilocybin in The Treatment of Depression: Ananya Mahapatra and Rishi GuptaRavennaNo ratings yet

- Mood Stabilizer and Antipsychotic Medication Coprescribing (Polypharmacy)Document1 pageMood Stabilizer and Antipsychotic Medication Coprescribing (Polypharmacy)Leslie CitromeNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of and Risk Factors For Anxiety After.2Document11 pagesPrevalence of and Risk Factors For Anxiety After.2misbah007No ratings yet

- Thought PDFDocument1 pageThought PDFsai calderNo ratings yet

- Time table-PGDM Trimester-I Batch 23-25Document6 pagesTime table-PGDM Trimester-I Batch 23-25Sushovan ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Intervencion 2.Document18 pagesIntervencion 2.Cristina MPNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy JPCPDocument4 pagesOccupational Therapy JPCPHanin MaharNo ratings yet

- 2023 35777 001Document53 pages2023 35777 001Paula Manalo-SuliguinNo ratings yet

- Supportive-Expressive Dynamic Psychotherapy: April 2017Document10 pagesSupportive-Expressive Dynamic Psychotherapy: April 2017MauroNo ratings yet

- Model-Based Cognitive Neuroscience Approaches To Computational Psychiatry: Clustering and ClassificationDocument22 pagesModel-Based Cognitive Neuroscience Approaches To Computational Psychiatry: Clustering and ClassificationabsNo ratings yet

- CBT Course Supporting NotesDocument20 pagesCBT Course Supporting NotesSushma KaushikNo ratings yet

- Applied Kinesiology: Distinctions in Its Definition and InterpretationDocument3 pagesApplied Kinesiology: Distinctions in Its Definition and InterpretationmoiNo ratings yet

- John Read Middle School - Class of 2011Document1 pageJohn Read Middle School - Class of 2011Hersam AcornNo ratings yet

- Jatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam UniversityDocument12 pagesJatiya Kabi Kazi Nazrul Islam UniversityAl-Muzahid EmuNo ratings yet

- 55+ Easy and Mostly Free Ways To Market Your BookDocument10 pages55+ Easy and Mostly Free Ways To Market Your BookSoulGate MediaNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Issues in Hr-1Document54 pagesCross Cultural Issues in Hr-1ANKIT MAANNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Managerial Accounting 9th Edition CrossonDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Managerial Accounting 9th Edition Crossonfloatsedlitzww63v100% (53)

- Gess SC 8 Course OutlineDocument4 pagesGess SC 8 Course Outlineapi-264733993No ratings yet

- Trueblue Activitysheets MarchDocument31 pagesTrueblue Activitysheets MarchS TANCREDNo ratings yet

- DUE 2016 Registration Form1Document1 pageDUE 2016 Registration Form1Mananga destaingNo ratings yet

- Jalova May 16 Monthly AchievementsDocument3 pagesJalova May 16 Monthly AchievementsGVI FieldNo ratings yet

- AffidavitsDocument36 pagesAffidavitsKarexa Skye LeganoNo ratings yet

- Special Leave Petition Format For SC of IndiaDocument8 pagesSpecial Leave Petition Format For SC of IndiaRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- Alejandro Vs PEPITODocument3 pagesAlejandro Vs PEPITONissi JonnaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Foundations of Nursing: TheoristsDocument2 pagesTheoretical Foundations of Nursing: TheoristsDenise CalderonNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Financial Statement AnalysisDocument37 pagesAn Overview of Financial Statement AnalysisShynara MuzapbarovaNo ratings yet

- MilleniumDocument2 pagesMilleniumrahul_dua111100% (1)

- Eugenio Vs DrilonDocument2 pagesEugenio Vs Drilonkei takiNo ratings yet

- BFCG-LA Exec Summary v2Document1 pageBFCG-LA Exec Summary v2Tim DowdingNo ratings yet

- Fil-Estate Properties Vs Spouses Go (GR No 185798, 13 Jan 2014)Document3 pagesFil-Estate Properties Vs Spouses Go (GR No 185798, 13 Jan 2014)Wilfred MartinezNo ratings yet

- Lancaster County Warrant SweepDocument2 pagesLancaster County Warrant SweepPennLiveNo ratings yet

- ICTAD Specifications For WorksDocument12 pagesICTAD Specifications For Workssanojani50% (8)

- Ducation: Indian School of Business, PGP in Management: Intended Majors in Strategy & FinanceDocument1 pageDucation: Indian School of Business, PGP in Management: Intended Majors in Strategy & FinanceSneha KhaitanNo ratings yet

- (SE) ..Case StudyDocument8 pages(SE) ..Case StudyIqra farooqNo ratings yet

- Project Management Report On Services Industry !!Document12 pagesProject Management Report On Services Industry !!Atif BlinkingstarNo ratings yet

- AR TablesDocument1 pageAR TablesrajeshmunagalaNo ratings yet

- AggressionDocument9 pagesAggressionapi-645961517No ratings yet

- FC PPT MahekDocument32 pagesFC PPT MahekShreya KadamNo ratings yet

- Construction Site Inspection ReportDocument2 pagesConstruction Site Inspection ReportTomasz Bragiel100% (1)

- Guide To UK State PensionsDocument87 pagesGuide To UK State PensionsslyxdexicNo ratings yet