Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Legacy of Ewald Hecker A New Translation of Die Hebephrenie 1985

The Legacy of Ewald Hecker A New Translation of Die Hebephrenie 1985

Uploaded by

Sarha AndradeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Legacy of Ewald Hecker A New Translation of Die Hebephrenie 1985

The Legacy of Ewald Hecker A New Translation of Die Hebephrenie 1985

Uploaded by

Sarha AndradeCopyright:

Available Formats

The Legacy of Ewald Hecker:

A New Translation of “Die Hebephrenie”

Mark J. Sedler, M.D.

Translated by MarieLouise Schoelly, M.D., and Edited by Mark J. Sedler, M.D.

once again began to flourish and scientific psychiatry

Early descriptions of schizophrenia may be found to progress.

in the writings of Haslam and Morel, but the turning This psychiatric renovation first took hold in En-

point in the development of the modern concept was gl and and France, but it was in Germany that a purely

Ewald Hecker’s classic paper on hebephrenia in descriptive-biological psychiatry eventually emerged.

I 871 . The syndrome he described-a psychosis of In large part this was due to the singular efforts of

early onset with a deteriorating course characterized Wilhelm Griesinger (1817-1868), who managed more

by a “silly” affect, behavioral peculiarities, and successfully than any of his contemporaries to system-

formal thought disorder-not only adumbrated atically ground a comprehensive psychopathology in a

Kraepelin’s generic category of dementia praecox but relatively objective neuropathology (2). This method

quite specifically defined the later subtype of (which the French school had originally deployed on a

hebephrenic, or disorganized, schizophrenia as well. smaller scale in the delineation of paralytic insanity)

The present translation into English of Hecker’s was thereafter applied to a broad range of well-

“Die Hebephrenie” makes accessible a crucial established clinical entities with the result that psychi-

milestone in the history of modern psychiatry. atry, rather suddenly, found itself to be a bona fide

(Am J Psychiatry 142:1265-1271, 1985) medical science. In this respect the German psychiatry

of the second half of the nineteenth century-from

I got the starting point of the line of thought that led to

Griesinger to Kraepelin-forged the scientific template

dementia praecox being regarded as a distinct disease . .. for modern psychiatry and created a nosologic frame-

from the experience connected with the observations of work that we have yet to transcend.

Hecker. Thus, we find that the modern history of schizophre-

-Emil Kraepelin (1, p. 3) nia begins not with the early formulations of John

Haslam (3) or the nomenclature of B.A. Morel (4) but

O all Kraepelin’s

praecox

celebrated

is the most renowned.

syntheses,

Together

dementia

with

with the relatively

psychiatrists. They

obscure

were

research

Karl

of two German

Ludwig Kahlbaum

manic-depressive illness it constitutes the most impor- (1828-1899) and his associate Ewald Hecker

tant clinical-nosologic paradigm of modern psychiatry. (1843-1909), who collaborated for nearly 10 years at

And if the past decade or so of American psychiatry the Reimer Sanitarium at G#{246}rlitz in East Prussia.

has frequently entailed a return to Kraepelin (and, in Although they worked in isolation from the main-

some quarters, a collateral departure from Freud), we stream of university psychiatry, their research on he-

should not make the error of imagining that we return bephrenia (1871) and catatonia (1874) soon became

to Kraepelin alone, for he could not have arrived at the touchstone for a 25-year debate about the place of

this powerful formulation ex nihilo. On the contrary, these “degenerative psychoses” within the evolving

Kraepelin’s concept of dementia praecox represented nosologic matrix that ultimately gave rise to

but the culmination of a tradition of psychiatric Kraepelin’s imposing system. It is convincing testi-

thought that extends at least to the end of the eigh- mony to the enduring value of their contributions that

teenth century. For it was then, with the “remedi- these categories have persisted as subtypes in the

calization” of madness, that the ars observationibus schizophrenic spectrum to the present day (5).

The better known of the two is Kahlbaum. Indeed,

in the field of descriptive psychopathology he looms

Received Sept. 24, 1984; revised Dec. 12, 1984; accepted Jan. 15, large as a founding father, although only after

1985. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Kraepelin did this come to be widely recognized.

State University of New York at Stony Brook; and the History of Denouncing the “former methods of working accord-

Psychiatry Section, Cornell University Medical College, New York,

N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Sedler, South Oaks Hospital,

ing to unilaterally psychological or unilaterally so-

400 Sunrise Highway, Amityville, NY 11701. matic principles,” Kahibaum advocated the “clinical

Copyright © 1985 American Psychiatric Association. method” of psychiatric research in which “all vital

Am J Psychiatry 1 42: 1 1 November

, 1985 1265

THE LEGACY OF EWALD HECKER

phenomena of the patient” were to be observed (6, pp. gators to focus their medical perceptions on a clinically

1-6). Among the “urgent requirements” of this homogeneous population with a characteristic symp-

method, Kahlbaum encouraged the cultivation of a torn complex and a predictable course.

“specialized scientific psychiatric symptomatology,” This purity of description, unencumbered by specu-

and his own contributions to this incipient science lative divagations, required a lucid disease

grasp of the

included “dysthymia,” “cyclothymia,” “paraphrenia,” concept. Although he acknowledged the value of the

“hebephrenia,” “catatonia,” and “verbigeration.” He “unitary psychosis” (vesania) model by which the

advanced the cause of nosology with his introduction course of insanity was supposed to progress through a

of the concept of “symptom complexes,” which stood succession of stages, from melancholia to mania and

intermediate between the limitless fecundity of symp- on to dementia, Hecker emphasized that real differ-

tom typologies (in which any prominent symptom was ences between mental diseases could still be discerned.

identified with a unique disease, e.g., incendiary mono- Taking general paresis as the standard example of a

mania) and the overzealous reductionism of the “uni- separate and distinct entity, he argued that hebephre-

tary psychosis” model. Like Griesinger before him and nia is similarly unique and should not be indifferently

Kraepelin after him, Kahlbaum was ultimately corn- subsumed by the unifying hegemony of the vesania

rnitted to the organicist viewpoint, and he believed that format. Hebephrenia, Hecker argued, is something sui

the etiologies of the major psychoses were to be generis, not only in consequence of its early onset and

discovered through neuropathological investigations deteriorating course, but by virtue of its peculiar and

(6). characteristic symptoms.

The contributions of Ewald Hecker are no doubt So clearly did he perceive the clinical outlines of this

more modest. He is known to us only marginally by his illness that his depiction of the characteristic state of

association with Kahlbaum and for his influential “hebephrenic dementia” has remained both vivid and

exposition of the concept of hebephrenia, which ad- accurate to the present day. His presentation of the

mittedly was an elaboration of Kahlbaum’s category of symptom picture went beyond simple behavioral de-

paraphrenia hebetica, first described in 1863 (7). scription; in fact, he carried out one of the earliest

Nonetheless, it was Hecker’s compelling description linguistic analyses of psychotic thought and speech.

that convinced Kraepelin of the basic connection be- Moreover, while Hecker’s model of hebephrenia was

tween early age at onset and certain forms of deterio- one of developmental arrest, a well-known nineteenth-

rating psychosis. This, together with Kraepelin’s own century etiology, he viewed the process in unusually

observation that a variety of initially differing symp- psychological terms, and his account of the vicissitudes

torn pictures tend to converge over time in a charac- of adolescence is remarkable. Yet, his etiologic consid-

teristic clinical dementia, led him to postulate the erations were anything but one-sided in their compass.

existence of a general but distinct disease process, He clearly distinguished between predisposing factors

namely, dementia praecox. Not only did Hecker’s such as head injury or infection in childhood and

concept of hebephrenia adumbrate this larger no- precipitating factors such as emotional stress. He did

sological construct, it also constituted the prototype not consider the latter of any particular etiologic

for what Kraepelin would later call “silly dementia,” importance, but he found the former a frequent factor

one of 1 1 subtypes of dementia praecox described in of uncertain significance. His prognostic observations

the eighth edition of his textbook (1, p. 94). With also proved accurate, despite his own reservations

Bleuler, hebephrenia became one of the four funda- about the limitations of his sample size. Unlike so

mental subgroups of schizophrenia (8), and today it is many of his contemporaries, he refused to speculate

synonymous with the “disorganized schizophrenia” of but encouraged, instead, the collection of “broad

DSM-III. statistical data.” In the final analysis, of course, Hecker

In spite of the obvious importance of Hecker’s paper believed that only neuroanatomical research would

on hebephrenia for any conceptual history of schizo- reveal the basic cause of the disease.

phrenia, the significance of his achievement has often Hecker is a minor figure in the history of psychiatry,

been unappreciated. His role in the development of the not to be compared with Haslam, Pinel, Esquirol,

concept of dementia praecox is similar to Falret’s part Griesinger, Kraepelin, or Freud. At the same time,

in the discovery of manic-depressive disease (9). In however, he demonstrates the importance of the ex-

both cases, prior descriptions lacked the necessary positor, as opposed to the creator, of new ideas. In his

conjunction of a phenomenological method, a longitu- day Hecker’s contributions gained him a degree of

dinal perspective, and a commitment to the project of prominence that seems to have overshadowed Kahi-

identifying discrete disease forms. In retrospect one baum himself, who had some difficulty communicating

certainly recognizes schizophrenia in the boys that his own insights (10). In fact, Kahlbaum was regarded

Haslam and Morel described, but one cannot turn by many as an eccentric and tedious theoretician

their clinical insights the other way round-it would whose project, in the words of Adolf Meyer, “required

be difficult to use their descriptions as a diagnostic the digestion of too many new terms, new and ideas,

formula. Hecker’s concept of hebephrenia, on the new facts” (1 1). Hecker, on the other hand, was a

other hand, constituted a reliable and highly specific relatively clear writer who would probably have corn-

nosologic instrument that enabled subsequent investi- pleted several monographs on Kahlbaum’s various

1266 Am J Psychiatry 142:1 1, November 1985

MARK J. SEDLER

diagnostic innovations had the latter allowed him to cretinism) have been widely discussed. It is puzzling to

do so. me that the literature concerning the mental disorders

In the end Hecker’s name is unlikely to be remem- of adolescence is comparatively meager given that

bered except insofar as it remains forever linked to the these disorders have certain striking and specific char-

concept of hebephrenia. Consequently, the recent acteristics. Of course, not all mental illness appearing

adoption of the term “schizophrenia, disorganized at puberty shows the same development. Nearly all the

type,” in the place of “hebephrenia” may mark a kind clinical forms (mania, melancholia, etc.) ca be found

of final oblivion for Ewald Hecker. And, given the lack in this age group without appearing much different

of any compelling grounds for this terminologic revi- than they do at other ages.

sion, it behooves us to ask: ought we be so quick to Hebephrenia, however, stands out as possessing

obscure our origins when we are as yet so uncertain of both a specific course and a distinct symptomatology.

the outcome? Moreover, this disease is by no means rare. From my

Although Hecker’s lengthy paper (12) contains own observations of about 500 patients over 4 years at

seven case histories, only the first of these is included the asylums of Allenberg and G#{246}rlitz, I collected 14

here. I have taken some liberties in making revisions, cases (2.8%), some of which I studied early in the

but, in general, I have tried to strike a fair balance course of the illness and others in the end stages. In

between an originally literal translation and the inter- addition, Dr. Kahlbaum generously allowed me access

ests of conciseness and clarity. In addition, it should be to a large number of his personal case histories. I am

noted that other translations of excerpts from Hecker’s convinced that every psychiatrist frequently sees cases

paper have appeared elsewhere (13). of hebephrenia and that in every asylum several such

patients may be discovered among the so-called de-

mented if one examines carefully their medical records

“Hebephrenia,” by Ewald Hecker (1871) and their specific clinical condition in the end stage.

Because hebephrenia is characterized by a rapid dete-

The clinical observation of psychological distur- rioration into dementia [Bl#{246}dsinn}, these patients usu-

bances teaches us from the start to differentiate be- ally enter the hospital well into the course of their

.

tween two main clinical categories whose specific illness so that they are, by this time, already psycho-

courses are clearly distinguishable from one another. logical cripples. The history of the illness before ad-

In the first category the clinical type (e.g., mania), once mission thus becomes the most important part of the

established, remains relatively consistent throughout psychiatric record. . . Therefore,

. I will begin with a

the course of the disease. The second category (vesania case history that, in nearly every particular, serves as a

typica), by contrast, is characterized by a series of teaching model of hebephrenia. ...

clinical states that progress, as if predetermined, from

melancholia, to mania, to confusion, and then to I . Observations

dementia. This last category is the one that opponents

Anamnesis (according to the medical report of Dr. Janert,

of classification have deemed the sole existing form of City Physician in K#{246}nigsbergin Prussia). Theodore K., at the

mental illness. Even they, however, concede that “gen- time (March 1862) 20 years of age, is the son of a sugar

eral paresis of the insane” belongs in a separate refiner who has been described as rather eccentric and who

psychopathological grouping. The reason for this is has lived apart from his second wife, the patient’s mother,

that these cases exhibit so typical a course, such for 18 years. There was no definite family history of mental

characteristic symptoms, and so clear a prognosis that illness. The patient was born and raised in K#{246}nigsberg,

they demand to be distinguished from vesania typica where he attended high school for 2 years. His upbringing

may have been somewhat lax due to the absence of a father’s

which, like paresis, also progresses more or less regu-

authority. He is described as having been a willful, passion-

larly through a series of clinical states.

ate boy of average intelligence. His physical development

With respect to the psychopathology of general

suffered from frequent childhood illnesses (variola, scarlet

paresis of the insane, Westphal has rightly pointed out fever, typhoid, intestinal inflammation, etc.), and he remains

the early onset of a rapidly progressing dementia. somewhat weak and nervous. After his confirmation, he

Indeed, in paresis, even the initial phases of melancho- entered a large wine house as apprentice, during which time

ha and mania are colored by this deteriorating process. he is said to have been a heavy drinker. Last summer he lost

But it was Kahlbaum who first drew attention to the his position as assistant, and so he traveled to Paris in search

fact that this striking clinical feature may also be found of another job but returned in November unsuccessful. He

in another clinical entity that otherwise has little in then stayed in K. and worried a great deal about being out of

a job.

common with paresis. This entity, which Kahlbaum

In the beginning ofJanuary the first signs of mental illness

has called “hebephrenia,” is a form of mental illness

appeared in the form of a depression. He became quiet and

whose variable symptoms are associated with the withdrawn, stared blankly, talked to himself, and laughed

tremendous mental and physical changes that occur without cause. In February he became extremely agitated. He

shortly after the onset of puberty. armed himself against imaginary enemies, sharpened a knife

For many years, particularly in England, the mental and an ax, and hid them under the sofa. He stayed up nights,

disorders of childhood have been carefully studied and knocked at the neighbors’ windows, and behaved in so

the forms of congenital mental retardation (idiocy and unruly a fashion that he had to be forcefully restrained. If

Am J Psychiatry 142:1 1, November 1985 1267

THE LEGACY OF EWALD HECKER

actual attacks of fury did not occur, this was perhaps due to more tractable, and he could be occupied with copy work.

the fact that his infirm mother did not attempt to oppose Finally, I must add to the medical history a letter of the

him. (In the city hospital where he has been since the end of patient’s that is especially characteristic. This will help to

J anuary he has often required restraint in a straitjacket.) complete the description of the clinical picture. [This letter,

Before he went to the hospital, his behavior increasingly took which is replete with syntactic and semantic aberrations, non

on the stamp of silliness [Albernheitj. He fell in love with a sequiturs, and other indications of profound thought disor-

girl who was still a child and would sit on her doorstep for der, is essentially untranslatable (M.J.S.).]

hours dressed only in a shirt. In the hospital he also acts silly,

mainly at night, during which time he hardly sleeps. He often

puts his head under the foot of a bed and, with his back, lifts The history just presented constitutes, as I stated

up the whole bed, even with a patient in it. He is markedly earlier, a model teaching case for the illness we call

disobedient, unruly, obstinate, and disagreeable. His speech, hebephrenia inasmuch as it exhibits both the typical

behavior, and movements suggest excitement, alternating course of the disease and its characteristic symptoms. . .

with depression; no hallucinations were observed (end of Dr. Hebephrenia, then, is a disease that always arises

J anert’s report). in connection with the development of puberty

On April 29, 1862, the patient, then 20, was brought to

[Pubert#{228}t]. In every case with which I am familiar, the

our asylum. His presenting condition was as follows: he was

onset, insofar as it could be determined, occurred

S ft. I in. tall, thin, and somewhat malnourished. He was

normocephalic, and his face was expressionless but silly; his between the ages of 18 and 22. Ordinarily, puberty

eyes were large, light blue, and staring (pupils equal in size), and its attendant “psychological renewal and transfor-

and he gazed at the ceiling or at the examiner with a blank mation of the self” (Griesinger) are more or less over

look. The patient gave correct answers about himself and his by this time. But in hebephrenia, this psychological

background but interjected silly remarks, shouted out with- process of puberty-which even under normal condi-

out any reason, and banged his feet on the floor and flung his tions displays many prominent “symptoms”-has be-

arms and hands about in a clumsy manner that is more come pathologically permanent. The psychological

characteristic of adolescents during their “awkward period”

features of this period of transition are pathologically

[L#{252}mmeljahren]. He talked to himself a great deal and took

exaggerated at first but ultimately give way to the

no interest in work or conversation. did silly things He

continually such as looking at the bright hopping on one sun,

specific end stage of hebephrenic dementia.

leg, running about aimlessly, twirling around in one spot With the onset of puberty there awakens in the soul

with his eyes closed and head bent backward, rubbing his of every young man and woman strange feelings that

eyes with grass, and, at one point, answering all questions provoke a vast complex of mysterious, unfamiliar

with the words “but the eyes.” ideas which are in conflict with preexisting concep-

These notes were taken from entries in the chart made in tions, and this conflict leads to a peculiar state of

May. During the following months similar observations were confusion. The new “self” wants to merge with the

made. For example, he slept poorly, often waking at 3:00 former self but cannot find room in the preexisting

a.m. and making a row by lying face down and pounding his

structure. Body and soul expand and stretch, back and

head against the headboard; or, while sitting, he would bang

forth, trying clumsily to adjust to new feelings and

his head against the chair back; or he would throw himself

flat on the floor and strike his head against the planks. When

ideas. The old self, with one foot still in childhood,

asked why he did these things, he replied that he was does not want to be dislodged. A battle then begins

“freezing.” At times he shouted “ji, ji, ji,” stuffed his nose whose peculiar conflicts of thought and feeling give the

with snuff because he was “hungry,” and constantly carried boy or girl the personality traits of the typical teen-

out equally absurd and childish acts. Once, while we were ager. This is the time when the sharpest contrast is

making rounds, he approached us with the words, “Herr apparent and the two selves touch, showing up side by

Direktor, yesterday I cried all day; I would like very much to side, although unevenly. Along with certain enthusias-

have some snuff; the food here is so thin.” On another tic yearnings, a taste for wild ideas and for precocious

occasion he was slouched down in a chair and called out to

conversation, one observes a quite specific silliness and

us without getting up, “Hello, Herr Direktor, are you feeling

a pleasure in stupid and even frivolous jokes. Deep and

well?” Asked then how he was doing, he replied, “After all,

one musthave his freedom.” When the hospital director delicate feelings coexist in stark contrast with a certain

explained, “You are still quite confused, I hear from Dr.--,” coarseness and uncouthness. Until the basic structures

he was interrupted by the patient saying, “Yes, I will tell you, of the personality have been reorganized and consoli-

Herr Direktor, that does not come from me, but from dated so as to assimilate their new contents, these ideas

Mertens” (the name of another patient). At times, on the and feelings seem formless and vague. Thought,

entrance of the physicians making their rounds, he would speech, gestures, and behavior lack the swift, sure,

raise his hand like a schoolboy wishing to be called on. He well-delineated form that we find in childhood as well

frequently annoyed, provoked, or ridiculed the other pa- as in adulthood. A certain inner and outer carlessness

tients, with whom he would have violent arguments and even

is evident. Just as the suddenly tall and awkward body

fistfights. For a while he maintained that he had been married

does not quite know what to do with its hands, arms,

some SO years but continued to give his age correctly; and,

on another occasion, he stated that he had been married and legs and, as a result, produces all sorts of daw-

while on Ward D. dling, slinging, clumsy movements and silly, ungov-

The condition of the patient did not change materially erned behaviors, so too the mind does not know how

during the 4 years he was under observation, but, in general, to manage its new ideas, sensations, and impulses.

he was more given to mannerisms, he became somewhat Consequently, the adolescent throws around this

1268 Am J Psychiatry 142:1 1, November 1985

MARK J. SEDLER

“unrefined gold” recklessly without really understand- years, his manner of speaking fostered the impression

ing its value. Gradually, around the age of 18 or that this was but a silly whim designed to amuse or

19, a certain order and concentration appear, and the dupe others or perhaps represented a childish pleasure

initially weak and fragile structure begins to consoli- in fantastic elaborations (confabulations according to

date. Kahlbaum). In many cases there appear rudimentary

It is at this time that the emotional disturbance of elements of a persecutory delusional system, remnants

hebephrenia occurs,

and, aside from its usual course, of the earlier melancholic phase; but most often the

its principal effect is the destruction of this unconsoli- thought content of these patients conforms to objective

dated structure and the reduction of its mental con- reality, showing only a certain silly, uncritical, childish

tents to a state of chaos. In this process the noblest part interpretation of the facts coupled, in strange contrast,

of the mind is lost. The psychopathological process with a distinct tendency to take up vague scientific

limits further intellectual and emotional development theories and ideas. As a result, a silly, driveling chatter

and produces a particular type of mental disability that is evident whose content consists mainly of bits and

retains only the dead elements of the earlier develop- pieces of previous semidigested knowledge along with

mental phase. The conflict has ended, but, in a sense, a tendency to uncritically generalize isolated personal

the conflicting elements have been frozen in position as experiences. Thus, these patients prefer to use the

if still struggling. pronoun “one” instead of “I.”

Thus we may describe the end stage of the disease Of special importance are the disturbances in form

process that dominates the course of the illness from that can be observed in the speech of hebephrenic

the outset. In addition to the peculiar form of this patients and in their writings. . There is a peculiar

. .

resulting dementia, the early onset of the disease is departure from normal logical sentence structure, with

characteristic of hebephrenia. In most cases the illness frequent changes in direction that may or may not lose

begins with the symptoms of melancholia, initially the train of thought and a preference for constructing

manifest as a vague, indescribable sadness and a long sentences. There is a characteristic negligence in

feeling of oppression into which various delusions are tying together sentences and an inability to express

gradually incorporated. Nearly all of the emotions thoughts concisely. The thought process unfolds for a

may be affected by this depressed mood, which can time without any specific direction or punctuation, and

manifest itself in destructive feelings of guilt, in exces- weird phrases appear. . . . This type of writing is

sive sentimentality, romantic yearnings, or in dark, notably different from that found with other mental

brooding delusions of persecution. Soon it becomes patients, e.g., those with paresis, because in hebephre-

evident that these emotions are relatively shallow and nia marked gaps in association are rare. Moreover, the

that the clinical picture differs considerably from that patient who does not suffer from an overabundance of

found in genuine dysthymia. For along with .a . . ideas or flight of ideas shows a remarkable tendency to

tendency to complain of their misery, lament their cling to a chosen subject of conversation and to

misfortune, confess their sins, or curse their persecu- “hound to death” certain expressions. At the same

tors, these patients often exhibit an irrepressible im- time the hebephrenic patient is unable to suppress

pulse to laugh and tell silly jokes. At the same time they thoughts arising from external stimuli and bizarre

show increased activity and bizarre behavior that may associations or to express them in an orderly fashion.

develop into severe agitation and even fury. In addition to this neglect of normal syntax, there is

This increased activity also expresses itself in point- a characteristic affinity for the uncouth and rather flat

less, silly behaviors or in a tendency toward vagrancy provincial dialects, even in writing, and even when the

and wanderlust; such individuals may wander about patient has not previously spoken, and certainly has

the world for a long time before they are declared ill. not written, in that dialect. Overall, there seems to be

Because of the particular nature of their mental distur- a tendency to depart from the natural manner of

bance, they are often diagnosed as malingerers, since it speaking and writing, to employ distortions of the

may seem that they are intentionally behaving and language and even foreign usages. Thus, one finds

talking in an absurd fashion. For this reason this imitations of “Jewish dialect,” of “officer talk,” ad-

diagnosis is of great importance to forensic psychiatry. mixtures of diverse languages, etc. The predilection for

A case report will soon be published in which a foreign words and the ambiguous, distorted use of

hebephrenic patient was given five contradictory med- such words stands in striking contrast with the pa-

ical opinions: initially he was judged sane and con- tient’s education. In all the cases I have described here,

demned to prison, but, with Kahibaum’s assistance, an the patients come from cultural backgrounds and

appeal succeeded in finding him insane. The difficulties positions that were very unlikely to have resulted in

in evaluating such cases arise mainly from the fact that such habits of speech and writing, which otherwise

the principal disturbances are behavioral, and only might be attributed to lack of education. More surpris-

rarely does one find clear-cut delusions. All sorts of ing still is the pleasure the patients appear to take in

bizarre ideas appear, but they have something fleeting employing rude, obscene, and generally unacceptable

and artificial about them that distinguishes them from language without apparent reason. Their pattern of

true delusions, i.e., fixed ideas. For example, when our speech drops well below that of their previous educa-

patient told us earlier that he had been married for SO tional level, and one finds an added trend toward

Am J Psychiatry 142:1 1, November 1985 1269

ThE LEGACY OF EWALD HECKER

extravagant talk, a love for sentimental tales, pseudo- But, because of the still provisional character of our

poetic diction and, as a result, an overabundance of knowledge of brain anatomy, we must renounce this

empty, artificial sentences. . . proof, possibly for a long time to come. This is all the

Considering the description of hebephrenia as a more likely given that our patients generally live to a

whole, it is obvious that not every symptom mentioned ripe old age, and only rarely do they come to autopsy

will be found in every patient or to the same extent. while still early in the course of the disease. For the

But, despite these individual differences, the character- present, I shall consider my task completed when I am

istic course that is invariably present, the early onset able to demonstrate on the basis of clinical observation

that is unmistakable, and the peculiarly silly form of that the cases I have reported can be linked together

dementia together make for a secure delineation of this into a unified psychopathological entity. ...

type of illness. As for prognosis, we can without hesitation call

The characteristic form of hebephrenic dementia can “incurable” all the cases I have reported because of the

be more or less marked depending on the severity of long duration of their illnesses and the extremely

the individual symptoms. While in certain cases the marked mental enfeeblement that has occurred. In one

silliness is controlled by a very peculiar precocity, in case death was due to an accidental complication

other instances the behavior seems depressed and is (pulmonary TB), but the other patients enjoy consist-

dominated by a profound mental dullness, although ent physical well-being and do not need to fear a

hebephrenic patients rarely develop the lowest levels of shortening of their lives. . . With the material

. at my

idiocy or the complete absence of intellectual function- disposal I am inclined to regard the prognosis for

ing found in patients with paresis. Rather, they typi- complete remission as very poor indeed, although I am

cally remain for a long time at an intermediate level of aware of the tentativeness of this conclusion due to the

mental deterioration. Not infrequently, periods of small number of cases. . .

agitation occur in the context of this state of mental I have mentioned already that hebephrenic patients

dullness, and they may reach the point of raving are often accused of malingering. Only a few days ago

mania. These periods of agitation often have external I received a case for observation in which the unhappy

causes such as sexual excitement (through masturba- patient had been drafted into military service and there

tion or menstruation) or the irritation of peripheral had been most cruelly forced to give up his so-called

nerves (e.g., a toothache). At times they are connected simulation. To this I must say that rarely would a lay

with intermittent hallucinations, usually auditory. person employ this kind of symptom picture for the

Hallucinations, a frequent symptom of mental illness, purpose of faking an illness. Such a person could

are common in hebephrenia, and they give the psycho- hardly be aware of this clinical picture and would

pathological picture a definite coloring but are without instead use more familiar forms. A convincing simula-

pathognomonic significance. ... tion of hebephrenia is, in fact, rather unlikely because

Concerning the etiology of hebephrenia, it is a the extravagant formal thought disorder would require

striking fact that most of the time, although not considerable practice to imitate. In any case, when

invariably, the affected individuals have been for confronted with the particular symptoms of hebephre-

known or unknown reasons (e.g., repeated physical nic dementia, it should not be too difficult for the

illness, head injuries, masturbation) somewhat slowed forensic physician to diagnose this type of illness and

down early in life in their physical and emotional thus to avoid serious errors.

development. Beginning in childhood they often ex- It would be a great satisfaction to me if my work

hibit a particular limitation, laziness, or incapacity for contributes toward an easier recognition of these facts

intellectual work. However, in clear contrast with and helps to protect one or another unhappy hebe-

idiocy (e.g., cretinism), this is not so severe or notice- phrenic patient from the danger of a judicial convic-

able as to prevent the individuals from developing far tion. Perhaps I may also hope that my work has made

enough to meet to some degree the expectations for a not unwelcome contribution toward furthering din-

their age group. . . . The differential diagnosis between ical research in psychiatry.

idiocy (a complex concept for a group of different

pathological entities) and hebephrenia should present

no difficulty. The mental limitation constitutes only a REFERENCES

predisposing cause for our illness. Among the precip- 1. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox (1913). Translated by Barclay

itating factors for an outbreak of the illness we fre- RM, edited by Robertson GM. Edinburgh, E and S Livingstone,

quently find emotional stress, anger, grief, etc., al- 1919

2. Griesinger W: Mental Pathology and Therapeutics, 2nd ed.

though these factors cannot be ascribed any special

Translated

by Robertson CL, Rutherford J. London, New

importance. At any rate, questions of etiology, even in Sydenham

Society, 1867

somatic pathology, remain enshrouded in darkness. As 3. Haslam J: Observations on Madness and Melancholy (1809).

for hebephrenia, only broad statistical data will shed New York, Arno Press, 1976, p 64

some light on the matter. 4. Morel BA: Trait#{233}

des Maladies Mentales. Paris, Masson, 1860,

p 566

The final proof that hebephrenia is a unified form of

S. Jelliffe SE: Dementia praecox: an historical summary. NY Med

mental illness in its own right can, of course, be J 91:521-531, 1910

established only on anatomicopathological grounds. 6. Kahlbaum KL: Catatonia (1874). Translated by Levij Y, Pridan

1270 Am J Psychiatry 142:1 1, November 1985

MARK J. SEDLER

T. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973 10. Kirchoff T (ed): Deutsche Irren#{225}rtze: Einzelbider Ihres Lebens

7. Kahlbaum KL: Die Gruppierung der psychischen Krankheiten Und Wirkens, vol 2. Berlin,J Springer, 1921-1924, pp 208-217

und die Einteilung der Seelenstoerungen. Danzig, AW Kafe- 1 1 . Meyer A: Evolution of the dementia praecox concept, in the

mann, 1863 Collected Papers of Adolf Meyer, vol 2. Baltimore, Johns

8. Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox, or the Group of Schizophrenias Hopkins Press, 1951, p 480

(1911). Translated by Zinkin J. New York, International Uni- 12. Hecker E: Die Hebephrenie. Archiv f#{252}r

pathologische Anatomic

versities Press, 1950 und Physiologic und f#{252}r klinische Medizin 25:394-429, 1871

9. Sedler MJ: Falret’s discovery: the origin of the concept of 13. Altschule MD: The Development of Traditional Psychopathol-

bipolar affective illness. AmJ Psychiatry 140:1127-1133, 1983 ogy. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1976

Am J Psychiatry 142:11, November 1985 1271

You might also like

- Rutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry PDF - Căutare GoogleDocument1 pageRutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry PDF - Căutare GoogleMihaela EvaNo ratings yet

- 60 Item Medical Surgical Nursing Musculoskeletal Examination AnswersDocument11 pages60 Item Medical Surgical Nursing Musculoskeletal Examination AnswersLj Ferolino94% (48)

- Abnormal Psychology Notes Barlow & Durand, "Abnormal Psychology" Black & Grant "DSM V Guidebook"Document54 pagesAbnormal Psychology Notes Barlow & Durand, "Abnormal Psychology" Black & Grant "DSM V Guidebook"Kat Torralba100% (1)

- Eccles, John - How The Self Controls Its BrainDocument114 pagesEccles, John - How The Self Controls Its Braintempullybone100% (6)

- The Black Book of TattooingDocument124 pagesThe Black Book of Tattooingmind_warps80% (15)

- Review Article: The Concept of Schizophrenia: From Unity To DiversityDocument40 pagesReview Article: The Concept of Schizophrenia: From Unity To DiversityAnthony HalimNo ratings yet

- The Wernicke-Kleist-Leonhard School of PsychiatryDocument4 pagesThe Wernicke-Kleist-Leonhard School of PsychiatryDiogo MacielNo ratings yet

- Eugen Bleuler's Dementia Praecox or TH Group of SchizophreniasDocument9 pagesEugen Bleuler's Dementia Praecox or TH Group of SchizophreniasJoão Vitor Moreira MaiaNo ratings yet

- Frank Fish Kraepelin NosologyDocument1 pageFrank Fish Kraepelin NosologyGustavo Pezzodipane PicalloNo ratings yet

- Bleuler and The Neurobiology of SchizophreniaDocument6 pagesBleuler and The Neurobiology of SchizophreniaMariano OutesNo ratings yet

- Psychopathology of Obsessive Compulsive DisorderDocument10 pagesPsychopathology of Obsessive Compulsive DisorderalexandraNo ratings yet

- Genealogia Dementia PrecoxDocument9 pagesGenealogia Dementia PrecoxMariano OutesNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology Case StudyDocument46 pagesAbnormal Psychology Case StudyGavin7100% (2)

- 153classic59 HeckerDocument17 pages153classic59 HeckerMariano OutesNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of DepressionDocument12 pagesBasic Concepts of DepressionDenis LordanNo ratings yet

- The Birth of The Bipolar Disorder: Historical ReviewDocument10 pagesThe Birth of The Bipolar Disorder: Historical ReviewFELIPE ABREONo ratings yet

- Is Schizophrenia The Price That Homo Sapiens PaysDocument16 pagesIs Schizophrenia The Price That Homo Sapiens PaysIoannis ChristopoulosNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia KraepelinDocument8 pagesSchizophrenia KraepelinAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Bipolarity From Ancient To Modern Times: Conception, Birth and RebirthDocument17 pagesBipolarity From Ancient To Modern Times: Conception, Birth and RebirthMariano OutesNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Psychosis - Historical and Phenomenological AspectsDocument11 pagesThe Concept of Psychosis - Historical and Phenomenological AspectsDaniel OconNo ratings yet

- Hebephrenic Schizophrenic: ReactionsDocument7 pagesHebephrenic Schizophrenic: ReactionsAlgifari AdnanNo ratings yet

- Karenberg Leitz 2001 Headache in Magical and Medical Papyri of Ancient EgyptDocument6 pagesKarenberg Leitz 2001 Headache in Magical and Medical Papyri of Ancient Egyptmai refaatNo ratings yet

- Case Histories: Bipolar DisorderDocument1 pageCase Histories: Bipolar DisordermariacarmenstoicaNo ratings yet

- Kaplan - Sadocks Synopsis of Psychiatry, 11th Edition-318-323Document6 pagesKaplan - Sadocks Synopsis of Psychiatry, 11th Edition-318-323nurmaulida568No ratings yet

- Wernicke BioDocument2 pagesWernicke BiolizardocdNo ratings yet

- Py 54920Document15 pagesPy 54920tratrNo ratings yet

- Leonhard - Classification of Endogenous Psychoses...Document423 pagesLeonhard - Classification of Endogenous Psychoses...veronicaherzelNo ratings yet

- Freud Returns8Document8 pagesFreud Returns8Dimitris KatsidoniotisNo ratings yet

- Parker, G - Melancholia, (2005) 162 Am J Psychiatry 1066Document1 pageParker, G - Melancholia, (2005) 162 Am J Psychiatry 1066KadroweskNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and PsychiatryDocument171 pagesPhilosophy and PsychiatrySandra LanguréNo ratings yet

- Meltzer Dream Life CH 3Document6 pagesMeltzer Dream Life CH 3mrpoetryNo ratings yet

- Delusional Disorder - An OverviewDocument12 pagesDelusional Disorder - An Overviewdrrlarry100% (1)

- CIcloyd Psychosis Peralta CuestaDocument10 pagesCIcloyd Psychosis Peralta CuestaJuan IgnacioNo ratings yet

- From Cenesthesias To Cenesthopathic SchizophreniaDocument8 pagesFrom Cenesthesias To Cenesthopathic SchizophreniaRavi KumarNo ratings yet

- 746-Article Text-3916-1-10-20141129Document8 pages746-Article Text-3916-1-10-20141129Mariano OutesNo ratings yet

- History of Psychosomatic Medicine BlumenfeldDocument20 pagesHistory of Psychosomatic Medicine Blumenfeldtatih meilaniNo ratings yet

- Biologizing Social FactsDocument21 pagesBiologizing Social Factsblatg9507No ratings yet

- Laurent Melancholia The Pain of Existence and Moral CowardiceDocument13 pagesLaurent Melancholia The Pain of Existence and Moral CowardiceAntoni GrzybowskiNo ratings yet

- 10p - Max Scheler's Notion of The Process of PhenomenologyDocument10 pages10p - Max Scheler's Notion of The Process of Phenomenologytiagompeixoto.psiNo ratings yet

- Neural and Mental HierarchiesDocument8 pagesNeural and Mental HierarchiesFrancisco MtzNo ratings yet

- General Psychopatology Vol I - K. J. (1997)Document279 pagesGeneral Psychopatology Vol I - K. J. (1997)Livia Santos100% (1)

- Rev Chil NeuroDocument19 pagesRev Chil NeuroFrancis MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Engstrom-Kraepelin Inaugural Dorpat LectureDocument14 pagesEngstrom-Kraepelin Inaugural Dorpat LectureraballusNo ratings yet

- Jaspers 100 Fuchs2013Document2 pagesJaspers 100 Fuchs2013Amàr AqmarNo ratings yet

- Primary Progressive Aphasia: A 25-Year RetrospectiveDocument4 pagesPrimary Progressive Aphasia: A 25-Year RetrospectiveDranmar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Existencialsmo en Psicopatologia en JasperDocument26 pagesExistencialsmo en Psicopatologia en JasperCamargo Landa XavierNo ratings yet

- Interpretacion Del Existencilaismo y Fenomenologia en PsicologiaDocument26 pagesInterpretacion Del Existencilaismo y Fenomenologia en PsicologiaCamargo Landa XavierNo ratings yet

- Francisco Varela View Neurophenomology PDFDocument3 pagesFrancisco Varela View Neurophenomology PDFmaxiNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud - A Short Account of PsychoanalysisDocument12 pagesSigmund Freud - A Short Account of PsychoanalysisciobanasNo ratings yet

- Ewald Hecker's Description of Cyclothymia As A Cyclical Mood Disorder - Its Relevance To The Modern Concept of Bipolar IIDocument7 pagesEwald Hecker's Description of Cyclothymia As A Cyclical Mood Disorder - Its Relevance To The Modern Concept of Bipolar IItyboyoNo ratings yet

- Kraepelin'S Paranoia: in The Recent Past, Widening and ConDocument5 pagesKraepelin'S Paranoia: in The Recent Past, Widening and ConfreakhermanNo ratings yet

- Focus On Psychosis Gaebel Zielasek (2015)Document10 pagesFocus On Psychosis Gaebel Zielasek (2015)rap 2treyNo ratings yet

- Messas Et Al 2017 Essence - Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesMessas Et Al 2017 Essence - Meta-AnalysisLeticiaNo ratings yet

- Schizophr Bull 2003 Sass 427 44Document18 pagesSchizophr Bull 2003 Sass 427 44JuanNo ratings yet

- Neurología Es PsiquiatríaDocument9 pagesNeurología Es PsiquiatríaCarolina MuñozNo ratings yet

- Working Notes - AB PSYCHOLOGYDocument3 pagesWorking Notes - AB PSYCHOLOGYKaye Hyacinth MoslaresNo ratings yet

- History of Abnormal PsychologyDocument16 pagesHistory of Abnormal PsychologyGwen MendozaNo ratings yet

- Critical NeurohermeneuticsDocument10 pagesCritical NeurohermeneuticsCarlosNo ratings yet

- AbPsych Reviewer 1 PDFDocument8 pagesAbPsych Reviewer 1 PDFSyndell PalleNo ratings yet

- Cap 1 Schizophrenia-And-Ocd-Comparative-CharacteristicsDocument21 pagesCap 1 Schizophrenia-And-Ocd-Comparative-CharacteristicsFábio Yutani KosekiNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenological Approach in Psychopathology..Document25 pagesThe Phenomenological Approach in Psychopathology..Luiza Pimenta RochaelNo ratings yet

- Healey 1986Document1 pageHealey 1986athulya mrNo ratings yet

- Message To All Applicants 2021Document3 pagesMessage To All Applicants 2021PGold Goodboy Golden RupNo ratings yet

- What Are The 5 Types of Social InteractionDocument3 pagesWhat Are The 5 Types of Social InteractionMairenn Mairenn Mairenn100% (1)

- The Physical Self - The Self As Impacted by The Body - 2Document7 pagesThe Physical Self - The Self As Impacted by The Body - 2Van AntiojoNo ratings yet

- What Are The Interpretations and Implications From Exhibit 1 of The Case Study?Document2 pagesWhat Are The Interpretations and Implications From Exhibit 1 of The Case Study?Saurabh Kulkarni 23No ratings yet

- Manus Radiographic Examination Technique in Patient With Corpus AlienumDocument3 pagesManus Radiographic Examination Technique in Patient With Corpus AlienumAnggraeni Indri SilviantiNo ratings yet

- Labor Monitoring RecordDocument4 pagesLabor Monitoring RecordFrancis PeterosNo ratings yet

- Chronic Disease An Economic PerspectiveDocument60 pagesChronic Disease An Economic PerspectiveJiva TuksNo ratings yet

- AEEDC 2024 Conference Program Brochure4 14.01.24Document16 pagesAEEDC 2024 Conference Program Brochure4 14.01.245q2f4j2vk2No ratings yet

- Tainted Saints - Rosa LeeDocument401 pagesTainted Saints - Rosa LeeClara FelicianoNo ratings yet

- Ongoing / Upcoming Activities at Manifa CHF Project: HSE HSEDocument12 pagesOngoing / Upcoming Activities at Manifa CHF Project: HSE HSERahil TasawarNo ratings yet

- Week 4 - Disaster Management ContinuumDocument42 pagesWeek 4 - Disaster Management Continuumirish felixNo ratings yet

- HeavymetalinKelantanRiver PDFDocument20 pagesHeavymetalinKelantanRiver PDFwan marlinNo ratings yet

- RPT Bi (KR) 2024Document11 pagesRPT Bi (KR) 2024Faris AdlyNo ratings yet

- Wa0005.Document1 pageWa0005.lucky textile3No ratings yet

- Teenage Pregnancy in CalabarzonDocument4 pagesTeenage Pregnancy in CalabarzonCaryl Jill Salem100% (2)

- Durie's Well-Being ModelDocument1 pageDurie's Well-Being ModelJermaine Amargo SadumianoNo ratings yet

- CH 08Document4 pagesCH 08Jessica Meagan Fullerton-SolanoNo ratings yet

- EP Fellowship Application InformationDocument2 pagesEP Fellowship Application InformationEliomar Garcia BelloNo ratings yet

- SuicidesDocument32 pagesSuicidesEljohn CabantacNo ratings yet

- (RP FPT Novice-Intermediate) 4x - Under 160 Lbs - Female Physique 2017 TemplateDocument46 pages(RP FPT Novice-Intermediate) 4x - Under 160 Lbs - Female Physique 2017 Templatenatasya susantiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper FinalDocument11 pagesResearch Paper Finalapi-559385696No ratings yet

- KrsDocument55 pagesKrsRavipr PaulNo ratings yet

- dm2022 0394Document21 pagesdm2022 0394Arlo Winston De GuzmanNo ratings yet

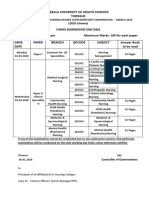

- Kerala University of Health Sciences Thrissur: (2010 Scheme)Document1 pageKerala University of Health Sciences Thrissur: (2010 Scheme)subiNo ratings yet

- AHCWS Food Brochure VataDocument2 pagesAHCWS Food Brochure VataĀditya SonāvanéNo ratings yet

- Employee Development: Human Resource Management Gaining A Competitive AdvantageDocument14 pagesEmployee Development: Human Resource Management Gaining A Competitive AdvantageNafees hasanNo ratings yet

- Aptitude TestsDocument2 pagesAptitude TestsGagan SinghNo ratings yet