Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pilbara Bioregion - EPBC Act Policy Statement - Consultation - January 2024

Pilbara Bioregion - EPBC Act Policy Statement - Consultation - January 2024

Uploaded by

dekruijff.peterCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pilbara Bioregion - EPBC Act Policy Statement - Consultation - January 2024

Pilbara Bioregion - EPBC Act Policy Statement - Consultation - January 2024

Uploaded by

dekruijff.peterCopyright:

Available Formats

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act

Policy Statement

Expectations and avoidance requirements for

referral and assessment of proposed projects in the

Pilbara bioregion

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

1

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

© Commonwealth of Australia 2023

Ownership of intellectual property rights

Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights) in this publication is owned by the

Commonwealth of Australia (referred to as the Commonwealth).

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any

process without written permission from the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. For more

information about this Draft Policy Statement, contact:

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

GPO Box 3090 Canberra ACT 2601

Telephone 1800 900 090

Web dcceew.gov.au

Email: pilbara@dcceew.gov.au.

Disclaimer

The Australian Government acting through the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water has

exercised due care and skill in preparing and compiling the information and data in this publication. Notwithstanding, the

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, its employees and advisers disclaim all liability,

including liability for negligence and for any loss, damage, injury, expense or cost incurred by any person as a result of

accessing, using or relying on any of the information or data in this publication to the maximum extent permitted by law.

Acknowledgement of Country

Our department recognises the First Peoples of this nation and their ongoing connection to culture and country. We

acknowledge First Nations Peoples as the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Lore Keepers of the world's oldest living

culture and pay respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

2

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Contents

1 Policy Statement ................................................................................................................... 5

1.1 Policy Objectives.................................................................................................................. 5

1.2 Pilbara Bioregion ................................................................................................................. 6

1.3 Policy Scope ......................................................................................................................... 8

1.4 Regulatory Pathways ........................................................................................................... 8

2 Regulatory Expectations .......................................................................................................11

2.1 Conservation Objectives .................................................................................................... 11

2.2 Mitigation Hierarchy.......................................................................................................... 11

2.3 Information Standards ...................................................................................................... 13

3 Pilbara EPBC Act Listed Threatened Species ..........................................................................16

3.1 Habitat Definitions ............................................................................................................ 16

3.2 Northern Quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus) ............................................................................... 17

3.3 Greater Bilby (Macrotis lagotis) ........................................................................................ 23

3.4 Pilbara Olive Python (Liasis olivaceus barroni) .................................................................. 29

3.5 Pilbara Leaf-nosed Bat (Rhinonicteris aurantia) (Pilbara form) ........................................ 34

3.6 Ghost Bat (Macroderma gigas) ......................................................................................... 43

3.7 Night Parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis) ............................................................................... 52

3.8 Grey Falcon (Falco hypoleucos) ......................................................................................... 59

3.9 Princess Parrot (Polytelis alexandrae) ............................................................................... 65

3.10 Great Desert Skink (Liopholis kintorei) .............................................................................. 70

4 Environmental Offsets ..........................................................................................................76

4.1 Residual Significant Impacts .............................................................................................. 76

4.2 Commencement of Offsets ............................................................................................... 78

4.3 Offset Design ..................................................................................................................... 78

4.4 Offset Information Requirements ..................................................................................... 79

4.5 Pilbara Environmental Offsets Fund.................................................................................. 84

4.6 Advanced offsets ............................................................................................................... 86

4.7 Offset Pathways................................................................................................................. 87

5 Review and Evaluation .........................................................................................................91

5.1 Review of scientific literature............................................................................................ 91

5.2 Evaluating the Policy ......................................................................................................... 91

6 Attachments ........................................................................................................................93

7 References ...........................................................................................................................94

8 End Notes .......................................................................................................................... 103

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

3

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Tables

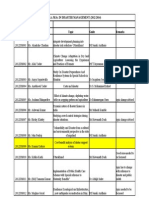

Table 3-1 Listed threatened species included in the policy. ................................................................. 16

Table 3-2 Northern Quoll habitat definitions ........................................................................................ 18

Table 3-3 Northern Quoll: mitigation of impacts .................................................................................. 19

Table 3-4 Greater Bilby habitat definitions ........................................................................................... 24

Table 3-5 Greater Bilby: mitigation of impacts ..................................................................................... 25

Table 3-6 Pilbara Olive Python habitat definitions................................................................................ 29

Table 3-7 Pilbara Olive Python: mitigation of impacts .......................................................................... 31

Table 3-8 Pilbara Leaf-nosed Bat habitat definitions ............................................................................ 36

Table 3-9 Pilbara Leaf-nosed Bat mitigation of impacts ....................................................................... 39

Table 3-10 Ghost Bat habitat definitions .............................................................................................. 45

Table 3-11 Ghost Bat: mitigation of impacts......................................................................................... 47

Table 3-12 Night Parrot habitat definitions .......................................................................................... 53

Table 3-13 Night Parrot: mitigation of impacts ..................................................................................... 55

Table 3-14 Grey Falcon habitat definitions ........................................................................................... 60

Table 3-15 Grey Falcon: mitigation of impacts ..................................................................................... 61

Table 3-16 Princess Parrot habitat definitions ...................................................................................... 65

Table 3-17 Princess Parrot: mitigation of impacts ................................................................................ 67

Table 3-18 Great Desert Skink habitat definitions ................................................................................ 70

Table 3-19 Great Desert Skink mitigation of impacts............................................................................ 72

Table 4-1 Maximum research offset contribution for the nine listed threatened species ................... 81

Table 4-2 Priority threat matrix and offset pathways of impact pathways .......................................... 87

Figures

Figure 1-1 Pilbara IBRA region and subregions ....................................................................................... 8

Figure 3-1 Northern Quoll survey and avoidance areas (640 m radius/129 ha area) ........................... 19

Figure 3-2 Greater Bilby survey and avoidance areas (1.5 km radius) .................................................. 25

Figure 3-3 Pilbara Olive Python survey and avoidance areas (365 ha area) ......................................... 31

Figure 3-4 Pilbara Leaf-nosed Bat survey and avoidance areas (500 m area) ...................................... 38

Figure 3-5 Ghost Bat survey and avoidance areas (500 m area) ........................................................... 47

Figure 3-6 Night Parrot survey and avoidance areas ............................................................................ 54

Figure 3-7 Grey Falcon survey and avoidance areas ............................................................................. 61

Figure 3-8 Princess Parrot survey and avoidance areas ........................................................................ 66

Figure 3-9 Great Desert Skink survey and avoidance areas .................................................................. 72

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

4

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

1 Policy Statement

This policy identifies minimum avoidance requirements and recommended mitigation and offsetting

measures for proposed development in the Pilbara bioregion likely to significantly impact one or

more of the following listed threatened species protected under Part 3 of the Environment Protection

and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act):

• Northern Quoll

• Greater Bilby

• Pilbara Olive Python

• Pilbara Leaf-nosed bat

• Ghost Bat

• Night Parrot

• Grey Falcon

• Princess Parrot

• Great Desert Skink

The policy also sets species-specific minimum information requirements for developers and their

consultants when surveying for species habitat at proposed impact sites, preparing EPBC Act

referrals, environmental impact assessment documentation, and proposed offset strategies or

management plans.

This policy has been developed to inform persons proposing new or expanded developments in the

Pilbara bioregion to:

1. design and locate projects that avoid and minimise impacts to these listed threatened

species to an acceptable level, and

2. prepare good quality referral and assessment information that is relevant, reliable and

complete.

It is expected that all proposed developments in the Pilbara bioregion likely to have a significant

impact on one or more of these listed threatened species will be designed to include the avoidance

standards and recommended mitigation and offsetting measures set out in this policy.

1.1 Policy Objectives

Matters of national environmental significance (or protected matters) represent the elements of the

environment and heritage that the Australian, state and territory governments have all agreed are in

our national interest to protect, conserve and restore. The protection of these matters under the

EPBC Act is guided by the principles of ecologically sustainable development.

As a regulator, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (the

department) has an important role to protect matters of national environmental significance and

ensure we are achieving the best possible environmental outcomes. We achieve this through the

assessment and regulation of proposed developments to ensure that impacts to matters of national

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

5

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

environmental significance are kept to an acceptable level for the matters’ ongoing persistence in the

region.

The key objectives of this policy are to:

1. achieve more efficient assessment of developments proposed in the Pilbara bioregion, and

2. promote ecologically sustainable development in the Pilbara bioregion, by requiring effective

application of the mitigation hierarchy.

Application of this policy is also expected to achieve the following outcomes.

1. Listed threatened species identified in this policy do not become more threatened, at the

regional level, as result of cumulative impacts of development in the Pilbara bioregion.

2. Promote effective engagement between the department and proponents prior to referral of

proposed developments in the Pilbara bioregion.

3. Avoidance measures in respect of impacts to critical breeding habitat and other ecologically

sustainable design measures are incorporated in early proposal design for projects in the

Pilbara bioregion.

4. Environmental assessment information submitted for projects proposed in the Pilbara

bioregion is relevant, reliable and complete.

5. Time taken by the department to assess proposed developments in the Pilbara bioregion is

reduced (and includes fewer requests for additional information).

6. More consistent, evidence-based decision-making and conditions of approvals for projects in

the Pilbara bioregion.

The department expects proponents to actively engage with, and support opportunities for working

with, First Nations peoples as early as possible. Appropriate stakeholder engagement is

fundamentally important to designing and delivering suitable avoidance, mitigation and offsetting

measures for any protected matters to be impacted.

1.2 Pilbara Bioregion

The Pilbara is a unique biogeographical region located in north-west Australia (Figure 1-1), which

hosts a wealth of ecosystems including terrestrial, aquatic, and marine environments. It supports

high value biodiversity including iconic and endemic species (McKenzie et al. 2009; Carwardine et al.

2014). Despite the Pilbara being an arid region of Australia, it supports an abundance of habitats

including rocky hills and mountain remnants, grassland savannahs, gorges, wetlands (including with

mangroves) and tropical woodlands along the coast (DBCA 2016).

Covering approximately 178,000 km2, the Pilbara bioregion is divided into four Interim Biogeographic

Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) subregions (Figure 1-1), comprising the Fortescue, Hamersley,

Chichester and Roebourne (Environment Australia 2000). These subregions are characterised by

dominant landscapes such as the coastal plains and offshore islands of the Roebourne subregion, the

ridges and tablelands of the Chichester and Hamersley subregions, and the low-lying alluvial flats of

the Fortescue subregion.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

6

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Figure 1-1 Pilbara IBRA region and subregions the geographic extent of the Pilbara Interim Biogeographic

Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) region outlined in black polygon and subregions outlined in yellow

polygons located within Western Australia of Australia.

The Pilbara bioregion has a rich and extensive First Nations cultural history, with some estimates that

the area was occupied 30–40,000 years before European colonisation (Wangka Maya 2021) and

others up to 50,000 or more (Dortch et al. 2019). The Pilbara bioregion has 31 Aboriginal cultural

groups that are mostly referred to as language groups. These cultural groups are considered highly

spiritual Peoples that are connected through and maintained by certain land features and areas

within the Pilbara. Custodianship is embedded into this connection to the Pilbara ‘country’ and

evidence of continuous ecosystem management (Dortch et al. 2019).

The Pilbara is hot and dry - evaporation exceeds rainfall by up to 3,000 mm/year across much of the

region. All surface streams other than parts of Fortescue Marsh are ephemeral, frequently flooding in

wet seasons and drying out over dry seasons. Groundwater is found in both perched and deeper

regional aquifers (DoW 2010; CSIRO 2015). Life in arid regions is frequently limited by water, and

sustained water sources, typically streams, springs and waterholes in the Pilbara, are highly valued by

all surrounding ecosystems. As discussed in Section 3, alterations of surface water and groundwater

systems, such as artificial water sources provided for cattle and dewatering of deeper mine pits, can

present direct and indirect threats (Mouritz et al. 2022) to the listed species considered in this

report.

Considered nationally and globally significant for its natural resources, the Pilbara bioregion is an

important area for conservation efforts for many reasons. The bioregion contains many native

species, some that are endemic to the Pilbara, which have adapted to the highly seasonal rainfall and

the unique geological and hydrological features.

The Pilbara bioregion is one of Australia’s development hotspots due to the volumes of iron ore, gas,

and other resources, and contributes substantial economic benefits both for Western Australia and

broader Australia (McKenzie et al. 2009). As stated in a report by the Western Australia (WA)

Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) (EPA 2014), the cumulative impacts of project

development in the Pilbara bioregion have the potential to undermine the biodiversity of the region.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

7

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

1.3 Policy Scope

This policy was informed by a review of scientific literature and studies of species’ ecology

predominantly from the Pilbara bioregion. This policy applies to projects occurring wholly or partly

within the Pilbara bioregion. A map of the Pilbara bioregion is available at Australia's bioregions

(IBRA) - DCCEEW.

Although most of the listed threatened species identified in this policy occur more broadly, this

policy is not intended to inform the design or assessment of projects outside the Pilbara bioregion.

Due to constraints in identifying survey and mitigation hierarchy requirements for all EPBC Act

protected matters in the Pilbara bioregion, this policy is limited to species that are commonly

impacted by development or at high risk of imminent extinction or highly restricted or limited in

distribution.

Future reviews of this policy may identify and include additional listed threatened species or other

matters protected under Part 3 of the EPBC Act in the Pilbara bioregion.

This policy does not replace the EPBC Act Significant Impact Guidelines and should be read in

conjunction with those Guidelines. Where proposed developments may impact on other protected

matters or controlling provisions of the EPBC Act, proponents should refer to relevant EPBC Act

policy statements and guidance, including:

• Significant Impact Guidelines 1.1 – Matters of National Environmental Significance

• Significant Impact Guidelines 1.2 – Actions on, or impacting upon, Commonwealth land and

Actions by Commonwealth Agencies

All of the department’s EPBC Act publications and resources are available from its website:

https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/epbc/publications.

1.4 Regulatory Pathways

The policy aims to support an efficient assessment of proposed developments in the Pilbara

bioregion that will have or are likely to have a significant impact on one or more of the nine species

identified in this policy.

Significant Impact Assessment

Direct and indirect impacts from mining and infrastructure development in the Pilbara bioregion

have extensively affected species populations across their range. The impact of development that

has already occurred, combined with the current and future development potential in the bioregion,

increases the risk of extinction for the listed threatened species identified in this policy.

In determining whether a proposed development is likely to be a controlled action, the Minister may

have regard to the cumulative effect of a proposal, and in combination with other developments, on

a species population, depending on the circumstances of the proposal. The Minister may decide that

a proposed development in the Pilbara bioregion is likely to have a significant impact on a matter

protected by Part 3 of the EPBC Act because the proposed development is likely to result in an

impact that is known to directly or indirectly lead to their decline (refer to Threat and Impact

Pathways tables for each species in Section 3).

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

8

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Proposed developments that will result in an impact that is known to directly or indirectly lead to the

decline of one or more of the species identified in this policy, is likely to have a significant impact on

a matter of national environmental significance and should be referred for a decision on whether

assessment and approval is required under the EPBC Act.

To better understand the potential impact of your project and check whether your proposed

development needs to be referred for assessment, a self-assessment should be undertaken. The

self-assessment requires a developed understanding of the EPBC Act assessment process, the

ecology of relevant species, as well as broader ecological concepts. You may need to seek assistance

from suitably qualified or experienced people when undertaking a self-assessment.

Keep a record of your self-assessment to demonstrate your thinking on why you did or did not refer

your proposal. Note that the department may need to investigate, and it may be a serious offence, if

you start a proposed development without approval.

Early Engagement

Where you self-assess your proposed development as likely to have a significant impact on any of the

listed threatened species identified in this policy, you are strongly encouraged to discuss your

proposal with the department. Engage with us as early in the planning phase of your project as

possible. In some cases, this could be several years prior to referral of the proposed development for

assessment. Earlier engagement increases the chance of avoiding delays and information requests

during assessment.

Early engagement with the department can also assist you to understand, properly apply, and

incorporate the mitigation hierarchy into the design of the proposed development at the conceptual

and planning stages, potentially saving time and project redesign costs at later stages.

You should be aware that there may be obligations to consult with First Nations peoples and

communities in relation to, for example, Native Title and Indigenous Protected Areas. Relevant First

Nations peoples and communities should also be engaged appropriately and as early in the project

planning phase as possible to ensure that First Nations interests and cultural heritage can be

protected as projects are designed. You should keep a record of this engagement as the department

will require this information to be provided as part of the referral and assessment process. The

Interim Engaging with First Nations People and Communities on Assessments and Approvals under

the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (interim guidance) sets out the

department’s expectations of proponents engaging with First Nations people and communities under

the EPBC Act.

Referral of a proposed development

When referring a proposed development in the Pilbara bioregion, the department expects referral

documentation will address all surveying and mitigation hierarchy information requirements outlined

in Section 3 of this policy. This includes supporting spatial data in Shapefile format. The referral

documentation should clearly demonstrate application of this policy, including how the avoidance

standards and mitigation measures have been applied, and if appropriate, an environmental offsets

plan or strategy.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

9

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

The Assessment Process

Where it is determined that a proposed development will have or is likely to have a significant impact

on any of the listed threatened species identified in this policy, the proponent or person proposing to

take the proposed development should ensure an environmental impact assessment is undertaken in

accordance with the information standards and survey guidelines, and mitigation hierarchy outlined

in Section 3 of this policy.

The department anticipates it will expedite the assessment process if:

• Early engagement with the department has taken place.

• The only controlling provision relevant to the proposed development is listed threatened

species and communities (Sections 18 and 18A of the EPBC Act).

• Listed threatened species that will be or are likely to be impacted include one or more of the

species in Section 3.

• Application of this policy to the proposed development is effectively demonstrated in

assessment documentation.

The full benefit of expedited assessments is expected when these criteria are met at the referral

stage. An expedited assessment will not be entirely achievable for development proposals

determined as likely to significantly impact migratory species or other protected matters not

identified in this policy. This is due to impact pathways, surveying, avoidance, mitigation or offsetting

measures specific to numerous other protected matters in the Pilbara bioregion not yet addressed in

this policy.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

10

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

2 Regulatory Expectations

The Australian Government is committed to decision making that protects and prevents extinctions

of listed threatened species appropriately under Australian legislation. This includes halting

biodiversity loss, promoting environment-friendly development and using nature-based solutions to

protect, restore and manage our most precious habitats, places and species.1 The application of the

expectations outlined in this policy will result in better regulatory certainty for project development.

This will likely lead to faster assessments as proponents will have clear guidelines to follow that can

be incorporated into project plans, years ahead of referral submission if necessary.

This policy provides a strategic approach to managing project-by-project and cumulative impacts on

the listed threatened species within the Pilbara bioregion. Our analysis has confirmed that

cumulative impacts on, and survival requirements of, each of these listed threatened species are not

yet well quantified in the Pilbara. This policy aims to manage cumulative impacts by assessing all

impacts to listed threatened species and applying the mitigation hierarchy consistently.

Implementation of this policy, supported by monitoring of important species metrics will improve

our understanding of cumulative impacts on the listed threatened species.

2.1 Conservation Objectives

Application of the avoidance, mitigation and offset measures in this policy when designing proposed

developments and implementing approved projects and offsets in the Pilbara bioregion is expected

to contribute to the following conservation objectives:

1. Protect, repair and restore habitat and likely areas of occupancy for the target species.

2. Protect, repair and restore connectivity of habitat for the target species.

3. Improve scientific knowledge of the nine target species.

The department will consider how these conservation objectives will be achieved by each proposed

development when engaging and providing early advice to proponents, assessing development

proposals, applying the mitigation hierarchy, through offset management plans and strategies, and

conditions of approval.

Monitoring and reporting in relation to these objectives may be required as a condition of approval.

For example, you may be required to report on the area of habitat within or adjacent to a project and

whether it continues to be protected from impact over the life of the project. You may also be

required to monitor and report on the success of offsets e.g., to repair and restore connectivity or

increase the likely areas of occupancy of a species.

Evaluation of how successfully the regulated industry and the department is achieving these

conservation objectives is discussed in Section 5 Review and Evaluation.

2.2 Mitigation Hierarchy

The Mitigation Hierarchy framework (Mitigation Hierarchy) is a tool that is used to limit the amount

of damage an action, such as a development, will have on the environment. The Mitigation Hierarchy

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

11

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

is aimed at avoiding or, where this is not feasible, minimising the impacts that a proposed

development will or is likely to have, and to balance environmental impacts with offsets.

Applying the Mitigation Hierarchy aligns with the principles of ecologically sustainable development.

The hierarchy establishes avoidance of impacts as the priority, then to reduce remaining impacts

through mitigation measures. Only once these options are exhausted, any residual significant

impacts must be offset. The generic requirements for each of the Mitigation Hierarchy tiers are

explained in the following subsections. Section 3 of the policy sets out further detail of how the

Mitigation Hierarchy will generally be applied to activities affecting the nine targeted species in the

Pilbara bioregion.

2.2.1 Avoid

Avoiding direct and indirect impacts is one of the best ways to protect listed threatened species. It is

often the easiest, most cost effective and efficient approach to minimising negative impacts when

considered in project planning.

In Section 3 of this policy, avoidance standards are set out for each of the listed threatened species in

the Pilbara bioregion. These standards have been developed based on statutory documentation and

best available scientific information. The avoidance standards are species-specific because each

species requires particular habitat to support their survival, breeding success, and persistence in the

landscape.

The avoidance standards concern areas encompassing environmental features that are critical to the

survival of each species, for example, critical habitat features for breeding (e.g., dens, burrows,

roosts and nests), landscape features (e.g., foraging areas, waterholes, dispersal features) and areas

of species occurrence.

All development proposals must consider and maximise opportunities to avoid direct and indirect

impacts to these areas in the design of a proposed development to support the species’ survival.

Protection of avoidance areas from direct and indirect impacts are likely to be specified in conditions

of approval for approved developments in the Pilbara bioregion. Approval conditions are also likely

to require monitoring of these avoidance areas to demonstrate the ongoing effectiveness of the

required avoidance measures.

2.2.2 Mitigate

Mitigation measures are management actions that have been designed to minimise and reduce

direct and indirect impacts to protected matters.

Section 3 of this policy under ‘Mitigation measures’ sets out key impact pathways and suggested

mitigation measures for each of the nine listed threatened species identified in this policy. The

referred development proposal should fully characterise the extent of these impact pathways for

each of the species and provide suitable evidence of how the proposed mitigation measure will be

effective in reducing direct and indirect impacts to the listed threatened species for the duration of

the proposed development. Mitigation measures will likely need to be applied for the life of the

impact, across the development envelope and undertaken within any areas subject to avoidance

standards.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

12

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

2.2.3 Offset

Environmental offsets can be considered for a proposed development only once higher tiers of the

Mitigation Hierarchy have been applied to the fullest extent possible. If there is a remaining residual

significant impact, offsets are required that ensure a conservation gain for the species and the

environment. In this policy, a range of priority offset activities are provided for each of the listed

threatened species in Section 4. These offset options may be delivered either through the Western

Australian government Department of Water and Environmental Regulation’s (DWER) Pilbara

Environmental Offsets Fund (the Fund) or delivered by the approval holder or a service supplier on

their behalf. These assessment expectations align with the key aims and principles of the EPBC

Environmental Offsets Policy (2012).

2.3 Information Standards

Where you self-assess that a proposed development will have or is likely to have a significant impact

on any of the listed threatened species identified in this policy, in addition to completing all

questions on the department’s referral form, you should provide supporting information when

referring the proposed development.

The department expects referral documentation will address all surveying and mitigation hierarchy

information requirements outlined in Section 3 of this policy. This includes supporting spatial data in

Shapefile format. The referral documentation should clearly demonstrate application of this policy,

including how the avoidance standards and mitigation measures have been applied, and if

appropriate, an environmental offsets plan or strategy.

The department strongly encourages outlining your proposed avoidance, mitigation and offsetting

measures at the referral stage, in accordance with this policy, as this will reduce the likelihood that

the department will need to request additional information and achieve a faster assessment.2

To avoid additional information requests and enable faster assessments, you must collect and submit

relevant environmental data that is robust, complete, accurate, clear, up to date and addresses the

requirements described in Subsections 2.3.1 – 2.3.3.

To ensure transparency and accountability, the department may conduct random audits to confirm

environmental information provided within environmental impact assessments is accurate.

2.3.1 Avoidance Information Requirements

Species-specific avoidance standards (or minimum avoidance requirements) are set out at

Subsection 2.2 and Section 3. Avoidance standards are informed by current scientific knowledge on

species’ ecological requirements to support its ongoing persistence.

To identify these habitat features and understand species presence in and around proposed

development sites (and therefore identify which areas must be avoided), you must undertake

surveys to fully characterise how each of the listed threatened species are permanently or

periodically using landscape features for breeding, foraging and dispersing across the development

envelope and the surrounding region in some cases. Historical survey data can also be used to inform

the species’ use of the development envelope. Specific information requirements for each of the

listed threatened species have been provided in Section 3.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

13

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Habitat and species-specific surveys will need to be undertaken at appropriate scale and in

appropriate timeframes to fully characterise how the listed threatened species are using the local

landscape. The size of the survey areas, and the amount of survey effort (e.g., methods for

identifying species detections and frequency of surveys) necessary for this purpose will vary for each

species.

As well as informing appropriate application of the Mitigation Hierarchy, the survey effort must be

designed to provide suitable baseline conditions for each of the species and habitat characteristics

that will be used to support on-going monitoring of avoidance areas.

The surveys should be used to inform how the avoidance standards have been applied for each

species likely to be present (see Section 3). All survey results should be provided as part of the

referred development information if an expedited approval is sought. Landscape characterisation

maps showing habitat and spatial data should be provided indicating how the avoidance standards

have been applied. All supporting information including species survey and habitat characterisation

data, should be provided in a clear manner, and should include Shapefiles defining specific avoidance

or activity-controlled zones. Guides to providing maps and boundary details and biological survey and

mapped data are available on the department’s website:

• Guide to providing maps and boundary data for EPBC Act projects - DCCEEW

• Guidelines for biological survey and mapped data - DCCEEW

2.3.2 Mitigation Information Requirements

To implement effective mitigation measures, each of the possible impact pathways must be fully

characterised within and adjacent3 to the development envelope for each of the project

components. These characterisations may be in the form of predictions based on evidence for each

of these direct and indirect impacts (e.g., blasting vibrations impacts on bat roosting caves) or

surveys (e.g., feral animal presence).

The information required to inform mitigation assessments will vary with each proposed

development and species affected, but as a minimum should include:

• Mitigation measures that will be applied for each of the direct and indirect impact pathways

with clear and detailed triggers, thresholds and management actions that will be

implemented. Each of the mitigation measures will need to be supported by on-going

monitoring for the life of an approval. Recommended mitigation measures have been

provided for each species in Section 3.

• Detailed analysis and discussion on how proposed mitigations will effectively reduce threats

or improve specific functional habitat characteristics impacting listed threatened species,

including proposed implementation as well as monitoring and evaluation indicators that will

be used to determine the effectiveness of the mitigations if enacted.

2.3.3 Offset Information Requirements

Any offset management plan or offset strategy should be provided at the time of the referral. It

should clearly outline the possible residual significant impact on each relevant species, the offset

pathway(s) that will be undertaken, and a discussion on how the proposed offset will meet the

conservation objectives for each species to be offset. Section 4 of this policy sets our recommended

priority offset pathways.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

14

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

All offset proposals should provide the following minimum information with the referred

development proposal:

• The proposed scope, timeframe and milestones (e.g., commencement and completion) for

the offsets, and party or parties responsible for offset delivery.

• A discussion on how the offset will result in a conservation gain for the impacted species

within the Pilbara bioregion, relative to the impacts to species which are predicted to occur if

the proposed development is approved.

• Details of the proposed monitoring and evaluation approach for the offset measures, and

how success will be measured (see Section 4). These should include clear and measurable

triggers which can be used to monitor the effectiveness of each offset measure.

• Demonstrate how the offset actions leverage regional conservation efforts and support First

Nations objectives within the Pilbara bioregion.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

15

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

3 Pilbara EPBC Act Listed Threatened

Species

As of January 2024, in the Pilbara there are total of 62 listed threatened species protected under

Sections 18 and 18A of the EPBC Act. Nine of the 62 listed threatened species have been considered

in this policy and have been listed in Table 3-1. Based on previously referred development proposals

within the Pilbara bioregion under the EPBC Act, these species are commonly impacted or at high risk

of imminent extinction or highly restricted or limited in distribution, therefore, the focus of this

policy.

Table 3-1 Listed threatened species included in the policy

Species Common Name Species Scientific Name EPBC Act Listing Status

Northern Quoll Dasyurus hallucatus Endangered

Greater Bilby Macrotis lagotis Vulnerable

Pilbara Olive Python Liasis olivaceus barroni Vulnerable

Pilbara Leaf-nosed Bat Rhinonicteris aurantia (Pilbara form) Vulnerable

Ghost Bat Macroderma gigas Vulnerable

Night Parrot Pezoporus occidentalis Endangered

Grey Falcon Falco hypoleucos Vulnerable

Princess Parrot Polytelis alexandrae Vulnerable

Great Desert Skink Liopholis kintorei Vulnerable

Source: Species Profile and Threats Database, Commonwealth of Australia 2023

3.1 Habitat Definitions

This policy uses the following definitions of home range and habitat types, which are based on how

these terms are used in relevant recovery plans and conservation advices. The following terms

should be used in the referred assessment documentation to ensure consistency in the application of

the policy and to support the assessment of the proposed development:

• Home range is the area used by a species that comprises known or potential breeding

habitat (e.g., nesting, burrowing, roosting, denning) required to support its ongoing

persistence, and foraging and water sources surrounding the breeding site required to

support breeding success.

• Critical habitat is habitat that is critical to the survival of a species and to maintaining their

persistence in the environment, and the protection of these habitats will aid in the recovery

of the species. Note: the definition of critical habitat in this policy is not limited to critical

habitat listed under section 207A of the EPBC Act.

• Key habitat is habitat outside of critical habitat types that is necessary to ensure a species

persistence and enable its recovery. Key habitat is important for supporting foraging,

dispersal and connectivity, or likely to provide breeding habitat in the future or allow for

species population expansion.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

16

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

3.2 Northern Quoll (Dasyurus hallucatus)

3.2.1 Survey information standards

Survey Methodology

Surveys for the Northern Quoll should be conducted over a minimum of two breeding seasons prior

to referral of the proposed development. Surveys should be undertaken in accordance with the

Survey guidelines for Australia’s threatened mammals (DSEWPaC 2011a) and EPBC Act referral

guideline for the endangered northern quoll Dasyurus hallucatus (DoE 2016).

Surveys must be undertaken within suitable denning4 habitat types outlined in Table 3-2. Pilbara-

specific survey methods must be undertaken in these habitat types to target female occurrences

using camera trap surveys (recommended survey method) from the end of October to February, to

avoid periods where male individuals are present in the population (semelparous life history; Moore

et al. 2020, 2023, unpublished). Use of camera traps is a non-invasive technique that can distinguish

individuals from their spots and identify the use of multiple dens and foraging habitat in the home

range. Elliot traps and pure meat baits should not be used in the Pilbara. Live traps are not a

preferred method due to possible stress on captured females carrying young in the pouch or having

dependent young in dens.

A minimum of seven consecutive nights of camera traps using non-replenishing food lures (e.g., bait

sprinkled in front of the trap once) or inaccessible scent lures (e.g., a perforated sardine tin, or a

perforated capsule containing bait or cotton soaked in tuna oil) is required. However, if during the

survey, there are early indications which establish a high-density presence of the Northern Quoll

(multiple unique individuals captured on the traps in the first few days), the survey can be ended

after four nights. The surveys should be appropriately scaled (Moore et al. 2023). For example, to

cover a 75 ha area a minimum of five vertically oriented cameras (1.5 m from the ground with baited

lure beneath) should be spaced a minimum of 200 m apart (Moore et al. 2020).

Survey Extent and Requirements

Surveys for the Northern Quoll must be undertaken within the defined development envelope and

within 640 m (female home range)5 outside the development envelope boundary (study area). The

surveys within the study area must:

1. Identify and categorise habitat in accordance with Northern Quoll habitat definitions at

Table 3-2.

Should surveys identify Northern Quoll habitats in the study area, the following surveys must be

undertaken:

2. Confirm detection or non-detection of Northern Quoll individuals.

Should surveys detect Northern Quoll, the following impact assessments must be undertaken:

3. Key foraging habitat impact assessment to identify the core foraging habitats and the known

or possible dispersal corridors.

4. Hydrological assessment(s) (e.g., groundwater and surface water impact assessments) to

identify hydrological controls of, and potential impacts to Northern Quoll habitats and

species persistence.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

17

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

3.2.2 Habitat definitions

Table 3-2 Northern Quoll habitat definitions

Habitat type Habitat Description

Critical Habitat Denning Habitat6 (Hill and Ward 2010; Moore et al. 2022; Cowan et al. 2023)

• Rocky hills, mesas, escarpments, ranges, breakaways, and rocky crevices in large boulder

fields including artificial habitats.

• Gorges and gullies with rocky creek lines and riverbeds.

• Major drainage lines with overstory and suitable vegetation cover.

• Offshore Islands.

Key Habitat Foraging habitat (Hill and Ward 2010; Hernandez

-Santin et al. 2018; Cowan et al. 2023; DCCEEW 2023a)

• Water sources in close proximity to denning habitat.

• Major drainage lines and tree lined creeks.

• Structurally diverse woodland or forest areas.

• Basalt hills, mesas (and buttes of limonites), high and low plateaus and lower slopes.

• Tor fields and stony plains supporting either hard or soft spinifex grasslands.

• Sandstone and dolomite hills and ridges, shrublands, sandy plains, clay plans and tussock

grasslands and coastal fringes including dunes islands and beaches.

3.2.3 Avoidance standards

The avoidance standards should be applied to all activities in the Pilbara bioregion where the

department’s species distribution model indicates that the Northern Quoll species or species habitat

is known, likely, or may occur.7

Any activities associated with a development should not be undertaken within avoidance areas and

corridors that need to be maintained for dispersal of the Northern Quoll. Appropriate action should

be taken to ensure any potential direct and indirect impacts (e.g., predation by feral cats and foxes,

feral herbivores, weed infestation, negative fire effects, changes to hydrology) on avoidance areas,

including corridors, are prevented and mitigated to maintain the viability of these critical habitat

areas.

Avoidance Standards:

1. If the surveys for the Northern Quoll detect a female, all critical habitat and key habitat

within a 640 m radius, or within a 129 ha area (female home range)8 surrounding the

occurrence of the Northern Quoll female, should be avoided within the development

envelope.

2. To ensure avoidance areas do not become isolated and restrict dispersal of Northern Quolls

(including males and juveniles) to other denning and foraging habitat, dispersal corridors

should be maintained between the avoidance area and other critical habitat outside the

development envelope, if they do not already exist. 9 Dispersal corridors should prioritise

linkages with drainage lines and watercourses and avoid using bare ground habitats (e.g.,

alluvial, coastal, and hardpan plains).10 Linear infrastructure will need to ensure suitably

designed and placed culverts are constructed to facilitate Northern Quoll dispersal.11

Figure 3-1 illustrates a conceptual example of application of the Northern Quoll avoidance standards.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

18

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

3.2.4 Further Avoidance

Further avoidance of species-specific disturbance outside the avoidance areas described above

should be applied where possible (e.g., limiting activities within the species’ foraging habitat).

Figure 3-1 Conceptual example of Northern Quoll survey and avoidance areas (640 m radius/129 ha area)

3.2.5 Mitigation measures

Table 3-3 identifies mitigation measures that are recommended to reduce key threats and impacts to

the Northern Quoll at the impact site. These measures, as well as ongoing monitoring to assess and

report their effectiveness, should be built into the proposed project design where appropriate and

included in project assessment documentation when referred under Part 7 of the EPBC Act.

Table 3-3 Northern Quoll: mitigation of impacts

Threat and impact pathways Recommended mitigation measures

Habitat Loss Minimise indirect loss of critical and key habitat as much as

Direct impacts to habitat will lead to the loss of practicable.

breeding and foraging habitat and will likely cause the Ensure clearing is undertaken progressively to minimise

degradation of surrounding habitat, increase fatalities of the species.

fragmentation risks, and possibly lead to an increase of Consider retaining suitably sized boulders during construction

predation by feral animals (Hill & Ward 2010; Cramer phases to be used in creating Northern Quoll rock piles in

et al. 2016b). adequate locations within the disturbance footprint during

progressive site rehabilitation.

Fragmentation and isolation Avoid direct and indirect impacts to dispersal corridors that

Due to its short breeding cycle and high adult link known Northern Quoll detections to areas outside the

mortality, Northern Quoll populations are particularly development envelope. These corridors should have suitable

vulnerable to local extinctions when isolated from habitat to facilitate dispersal and prioritise water courses and

other populations in the landscape as re-establishment riparian areas with high vegetation.

from other populations is unlikely (Hill and Ward 2010; Mitigation measures of feral predators and negative fire

Braithwaite and Griffiths 1994; Rankmore and Price effects are required within the dispersal corridors to minimise

2004; Oakwood 2000) these threats during the juvenile male dispersal periods and

Many Northern Quoll populations in the Pilbara are mating seasons (Autumn to Winter).

now smaller and more isolated, leading to inbreeding Ensure that suitably designed culverts (Creese 2012) are

and loss of genetic diversity, increasing their extinction implemented in dispersal corridors that intersect with linear

risk (Moore et al. 2022). infrastructure, especially in preferred drainage dispersal

Maintaining the genetic connectivity and supporting habitats.

high levels of gene flow is important to maintain the

Pilbara Northern Quoll metapopulation (Shaw et al.

2022).

Linear infrastructure such a roads and rail have the

potential to fragment and create barriers to the

movement of the Northern Quoll (Creese 2012).

Feral Predators Implement a feral cat or fox control program which aims to

Feral cats and foxes (potentially) impact Northern minimise feral predator numbers within and around the

Quolls by competing for the same food (prey) and development envelope, including known denning habitat

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

19

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Threat and impact pathways Recommended mitigation measures

through direct predation. Predation may be (especially after mating period) and dispersal corridors (during

exacerbated in areas impacted by recent fires (Hill and the juvenile and male dispersal periods) for the Northern

Ward 2010; Cramer et al. 2016b). Quoll, over the life of the approval.

Feral control programs should be designed in accordance with

relevant EPBC Act threat abatement plans and be informed by

contemporary findings on best practice feral predator

management. See National Environmental Science Program

Best-practice management for feral cats and red foxes

outcomes (NESP 2023).

Any baits used should be proven safe for Northern Quolls

(e.g., Eradicat not currently safe for Northern Quolls).

Engaging First Nations Ranger groups to undertake the works

or the use of Felixers, are the preferred methods of landscape

cat and fox management methods in the Pilbara. Novel and

innovative techniques are encouraged.

Monitor and report feral predator numbers around the impact

site compared to a pre-disturbance baseline. Baseline and

ongoing surveys should follow Pest animal monitoring

techniques (Pest Smart 2021b).

Feral Herbivores Fence off avoidance areas, including denning habitats and

Large herbivores, including cattle, impact Northern dispersal corridors, especially nearby watercourses (e.g., rivers

Quolls by degrading key habitats (especially and creek lines), from feral herbivores. Fencing should follow

watercourses) by trampling and grazing. The best practice exclusion fencing guidelines and allow ongoing

degradation of these habitats will lead to the loss of dispersal of the species. Manage potential increase in weed

vegetation cover and related prey items in these invasion as a result of removing grazing from the fenced areas.

habitat types. Feral herbivore control programs should be designed in

Grazing may also promote vegetation thickening and accordance with relevant EPBC Act threat abatement plans

weed invasion, degrading preferred habitats and likely and be informed by contemporary findings on best practice

leading to larger fire risks (Hill and Ward 2010). feral herbivore management. For camels, this may include

management techniques outlined in the National feral camel

Loss of vegetation from degradation may increase

action plan Appendix A3 (Natural Resource Management

predation threat to the Northern Quoll (Hill and Ward

Ministerial Council 2010) and Pest Smart feral camel controls

2010).

(Sharp and Saunders 2012). Suitable control and fencing

measures for rabbits and goats are outlined in Background

document: Threat abatement plan for competition and land

degradation by rabbits (DEE 2016b), Threat abatement plan

for competition and land degradation by unmanaged goats –

Background (DEWHA 2008a) and Cost effective feral animal

exclusion fencing for areas of high conservation value in

Australia (Long and Robley 2004).

Monitor and report feral herbivore numbers around the

impact site compared to a pre-disturbance baseline. Baseline

and ongoing surveys should follow Pest animal monitoring

techniques (Pest Smart 2021b).

These measures should be implemented and maintained for

the lifetime of the approval.

Cane Toads Implement biosecurity protocols to minimise risk of

Cane toads are likely to invade the Pilbara and could introducing cane toads to the development area.

be consumed by Northern Quolls causing death Avoid the creation of habitat suitable for cane toads.

(Cramer et al. 2016b). Implement cane toad-proofing techniques that upgrade all

pastoral watering points, pivot irrigation and other artificial

watering points within the development envelope and use

troughs, containers or tanks inaccessible to cane toads rather

than the development of dams. All wastewater pond

developments should demonstrate best practice cane toad

aversion techniques are considered and will be implemented.

Cane toad control programs should be designed in accordance

with the Threat abatement plan for the biological effects,

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

20

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Threat and impact pathways Recommended mitigation measures

including lethal toxic ingestion, caused by cane toads

(DSEWPaC 2011c) and be informed by contemporary findings

on best practice cane toad management, for example Pest

Smart cane toad tool kit (Pest Smart 2021a).

Monitor and report cane toad occurrence within the

development area compared to a pre-disturbance baseline,

following contemporary best practice survey techniques.

Weeds Implement a targeted weed hygiene and management

Weed invasion such as with exotic pasture grasses will program which aims to prevent the introduction and minimise

inhibit and limit the foraging and dispersal of the occurrence of weeds in avoidance areas and in other critical

Northern Quoll (Hill and Ward 2010). and key habitats within the development envelope, over the

life of the approval. Manage any increased fire risk as a result

Weed infestations will also likely increase the risk of

of weed invasion.

negative fire effects that will impact the Northern

Quoll habitats (Hill and Ward 2010). Weed management programs should be designed in

accordance with relevant EPBC Act threat abatement plans

and be informed by contemporary findings on best practice

management of the weed species identified during baseline

surveys and in accordance with the Threat abatement plan to

reduce the impacts on northern Australia's biodiversity by the

five listed grasses (DSEWPaC 2012). This may include

guidelines for Buffel grass management for Central Australia

(Department of Environment and Natural Resources 2018) and

Gamba Grass (Weeds Australia 2023) as well as Integrated

weed management (Weeds Australia 2021a). Minimising the

risk of invasion of buffel grass in the development envelope

and avoidance areas should be a key priority.

Monitor and report weed occurrence within the development

envelope compared to a pre-disturbance baseline, following

contemporary best practice survey techniques such as those

outlined by Weeds Australia (2021b).

Other weed species management techniques can be found at

Weeds Australia (2021c).

Fire effects on habitat suitability and facilitation Implement a fire management program which aims to reduce

interactions (FHF) and fire effects on predator-prey the risk of uncontrolled fires within and around the avoidance

interactions (FPI) areas, including dispersal corridors, and in other critical and

Fire impacts the Northern Quoll through the loss of key habitats within the development envelope, over the life of

habitat structure and vegetation types that will change the approval.

prey availability through the reduction in the Fire management programs should be designed in accordance

abundance of food, particularly invertebrates if there with contemporary knowledge of species-appropriate fire

is insufficient time to complete their life cycles (Hill management practices. Prescribed burns should be

and Ward 2010). undertaken outside the Northern Quoll breeding season.

Fire will remove vegetation cover that will likely Manage potential increased predation by feral predators

increase predation from native and feral predators associated with prescribed burning.

(Moore et al. 2022; Cook 2010).

See Fire regimes that cause declines in biodiversity

(DAWE 2022) for information on types of fire-related

ecological processes.

Climate Change To support climate change resilience for Northern Quoll

The Northern Quoll will likely be impacted by climate populations, the main method applied is an adaptation

change due to increased temperatures, rainfall strategy to protect known occurrences of the species and

variability, increased proportion of extreme rainfall maintain landscape connectivity through implementing the

events, and less frequent cyclones. In the Pilbara, it is avoidance standards (Pavey 2014).

likely that there will be more extreme, frequent and As outlined in a recent review of the Northern Quoll (Moore et

hot fire events as a result of climate change. In al. 2022), identifying potential climate refuges is key for the

addition to changes in rainfall, average temperatures persistence of the species in the face of climate change.

across Northern Australia will continue to increase and Minimising the loss of habitat for the species and ensuring

there will be more days with extreme maximum that impacts from increased risk of cane toad invasion, fire

temperatures (Moore et al. 2022). risks and feral predators are mitigated to maintain habitats

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

21

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Threat and impact pathways Recommended mitigation measures

where the species is known to occur will assist in creating

climate refuges until further information is known about the

species response to these changes (Pavey 2014).

Vehicle & Rail Strikes Implement and enforce dusk-to-dawn speed limits, in

The Northern Quoll Referral guidelines outline the accordance with contemporary knowledge of appropriate risk

need to reduce and enforce speed limits in the vicinity reduction measures (e.g., 40 km/hr speed limits

of Northern Quolls (DoE 2016). recommended by Johnson and Anderson 2014), of any roads

in close proximity to avoidance areas, and other critical and

Linear infrastructure such as roads and rail have the

key habitats which are fragmented by roads and fire breaks.

potential to increase road and train strikes on

Northern Quolls (Creese 2012). Use virtual fencing, such as reflectors, auditory, signs, rumble

strips and road slowing methods to mitigate the risk of vehicle

strikes.

Ensure that suitably designed culverts (Creese 2012) are

implemented in dispersal corridors that intersect with linear

infrastructure, especially in preferred drainage dispersal

habitats.

Hydrological Changes Surface water and connected groundwater regimes within the

Studies have demonstrated the importance of water habitats used by Northern Quolls within the development

for the Northern Quoll and permanent water sources envelope should be maintained.

as contributing to critical and key habitat for the

species and riparian areas which facilitate dispersal of

the species (Oakwood 2000; Woinarski et al. 2008;

Shaw et al. 2022)

3.2.6 Residual significant impact

Survey data collected to identify and characterise Northern Quoll habitat within the study area

should be used to quantify the extent of critical habitat and key habitat (refer to Table 3-2) that will

be directly or indirectly impacted by an activity following avoidance and mitigation efforts. These

areas will be used to inform calculation of residual significant impact.

Residual significant impact calculation

Any direct or indirect disturbance of critical habitat or key habitat outside of avoidance areas and

within the development envelope will be considered a residual significant impact where a Northern

Quoll occurrence has been recorded within the study area.

Refer to Section 4 for information on offsetting residual significant impacts.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

22

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

3.3 Greater Bilby (Macrotis lagotis)

3.3.1 Survey information standards

Survey Methodology

Surveys for the Greater Bilby should be conducted over a minimum of two years with suitable

seasonal coverage (every one to four months) undertaken as close to the date of referral of a

proposed development as possible. The survey data provided at the referral stage can contain

historical data in addition to the contemporary surveys of the Greater Bilby. Surveys for the Greater

Bilby should be undertaken in accordance with the Survey guidelines for Australia’s threatened

mammals (DSEWPaC 2011a).

Pilbara-specific survey requirements align with the Survey guidelines for Australia’s threatened

mammals (DSEWPaC 2011a) in undertaking targeted searches in preferred habitat types for burrows,

tracks, scats and diggings. However, as outlined in Greater Bilby survey methodology studies (e.g.,

Thompson and Thompson 2008; Skroblin et al. 2021; Northover et al. 2023), detection of Greater

Bilby tracks and diggings (at the base of plants to access root-dwelling larvae) is challenging and will

need to be undertaken by trained and experienced observers, including First Nations Ranger groups.

Determining the presence of the Greater Bilby within the study area requires a range of survey

approaches depending on the size of the Greater Bilby preferred habitats. It can include running

systemically designed transects, either on foot or aerially, to identify digging and burrowing activity.

Remote cameras, scat genetic analysis, or burrow system mapping can then be used to further refine

the habitats used by the Greater Bilby within the study area. For large areas see Appendix 2 of

Northover et al. (2023) and for small areas see Appendix 3 of Northover et al. (2023).

Survey Extent and Requirements

Surveys for the Greater Bilby must be undertaken within the development envelope and within

1.5 km (female home range)12 outside of the development envelope boundary (study area). The

surveys within the study area must:

1. Identify and categorise habitat in accordance with Greater Bilby habitat definitions at

Table 3-4.

Should surveys identify Greater Bilby habitats in the study area, the following surveys must be

undertaken:

2. Confirm detection or non-detection of Greater Bilby occurrences (i.e., sightings, diggings,

scats, burrowing evidence).

Should surveys detect the Greater Bilby, the following impact assessments must be undertaken:

3. Key foraging habitat impact assessment to identify the core foraging habitats and the known

or possible dispersal corridors.

4. Hydrological assessment(s) (e.g., groundwater and surface water impact assessments) to

identify hydrological controls of, and potential impacts to Greater Bilby habitats and species

persistence.

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

23

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

3.3.2 Habitat definitions

Table 3-4 Greater Bilby habitat definitions

Habitat type Habitat Description

Critical Habitat Burrowing habitats (DCCEEW 2023b; Cramer et al. 2017)

• Plain habitat with isolated dunes and dune fields that support soils from coarse sand to

light medium clay, which has the following vegetation types:

o Woodlands of low trees (<10m) with Eucalyptus and Acacia spp.

o Shrub-steppe communities over Triodia hummock grasslands.

o Pindan woodland with hummock and tussock grasses.

• Rises, breakaways, plateaus, granitic hills and rises that support sandy soils, sandy

loams and red earths often with lateritic, small gravel, stony matrix, featuring vegetation

types of low shrub cover of Acacia spp. including mulga (A. aneura) over hummock and

tussock grasses.

• Creeklines and palaeodrainage systems that support sandy and sandy loam soils, alluvial

and calcareous areas, and salt channels and lakes, featuring vegetation types of Spinifex

grasslands (mainly Triodia basedowii, T. pungens and T. schinzii) with low shrub cover of

Acacia spp. and Melaleuca spp.

Key Habitat General foraging and dispersal habitats (DCCEEW 2023b; TSSC 2016c; Southgate et al. 2007)

• Open tussock grasslands on uplands and hills.

• Mulga (Acacia aneura) woodland/shrubland (both pure mulga and mixed stands of

mulga/witchetty bush) growing on ridges and rises.

• Hummock grassland growing on sand plains and dunes, drainage systems, salt-lake

systems, and other alluvial areas.

• Laterite and rock feature substrates that support Acacia kempeana, Acacia hilliana and

Acacia rhodophylla shrub species and spinifex hummocks with open runways between

the hummocks for easy movements.

3.3.3 Avoidance standards

The following avoidance standards should be applied to all activities in the Pilbara bioregion where

the department’s species distribution model indicates that the Greater Bilby or species habitat is

known, likely, or may occur.13

Any activities associated with a development should not be undertaken within avoidance areas,

including corridors maintained for dispersal. Appropriate action should be taken to ensure any

potential direct and indirect impacts (e.g., predation by feral cats and foxes, feral herbivores, weed

infestation, negative fire effects) on avoidance areas, which includes corridors, are prevented and

mitigated to maintain the viability of these critical habitat areas.

Avoidance Standards:

1. If surveys for the Greater Bilby identify a single active burrow14, the single active burrow and any

habitat (i.e., all vegetation, topsoil, water sources) within a 1.5 km15 radius (female home range)

of the burrow should be avoided in the development envelope.

2. If surveys for the Greater Bilby identify multiple active burrows, all active burrows and all

habitat within a 1.5 km radius of the outermost active burrows should be avoided in the

development envelope.

3. To ensure avoidance areas do not become isolated and restrict dispersal of the Greater Bilby to

other burrowing and foraging habitat, a dispersal corridor should be maintained between the

avoidance areas and other habitat within and outside the development envelope if it does not

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

24

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

already exist.16 Dispersal corridors should consist of critical and key habitat types.

Linear infrastructure will need to ensure suitably built and placed culverts are constructed to

facilitate Greater Bilby dispersal. 17

Figure 3-2 illustrates a conceptual example of application of the Greater Bilby avoidance standards.

3.3.4 Further Avoidance

Further avoidance of species-specific disturbance outside the avoidance areas described above

should be applied where possible (e.g., limiting activities within the species’ foraging habitat).

Figure 3-2 Conceptual example of Greater Bilby survey and avoidance areas (1.5 km radius)

3.3.5 Mitigation measures

Table 3-5 identifies mitigation measures that are recommended to reduce key threats and impacts to

the Greater Bilby at the impact site. These measures, as well as ongoing monitoring to assess and

report the effectiveness of these measures, should be built-in to the proposed project design where

appropriate and included in project assessment documentation when referred under Part 7 of the

EPBC Act.

Table 3-5 Greater Bilby: mitigation of impacts

Threat and impact pathways Recommended mitigation measures

Habitat Loss Minimise indirect loss of critical and key habitat as much as

Direct impacts to habitat will lead to the loss of practicable.

breeding and foraging habitat and will likely cause the

degradation of surrounding habitat, increase

fragmentation risks, and possibly lead to an increase of

predation by feral animals (DCCEEW 2023b).

Fragmentation and genetic isolation Locate infrastructure in ways that allow for dispersal of the

Development of roads, fences, dams, large-scale Greater Bilby within and beyond the development envelope.

agriculture irrigation, pipelines, industrial structures Ensure that suitably designed culverts (Creese 2012) are

and proposed activities with large footprints (e.g., implemented in dispersal corridors that intersect with linear

mines, solar salt, renewables) will create barriers to infrastructure, especially in preferred drainage dispersal

dispersal of the species and restrict their ability to habitats.

establish new populations and inhibit the roving of

males (DCCEEW 2023b).

Isolated populations are more susceptible to

extinction and less resilient to natural fluctuation,

there are reduced opportunities for evolutionary

adaptation to changes in the environment with

restricted genetic exchange across the populations

(DCCEEW 2023b).

Feral Predators Implement a feral cat and fox control program which aims to

Fox and feral cat predation are major factors minimise feral predator numbers within and around the

associated with the decline of Greater Bilbies

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

25

Pilbara Bioregion: EPBC Act Policy Statement

Threat and impact pathways Recommended mitigation measures