Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PeaceDepartment Report v08 MSG-LR

PeaceDepartment Report v08 MSG-LR

Uploaded by

Derrick Andika JudaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Strategy and Sustainability Week 2 Quiz 2 SolutionsDocument2 pagesStrategy and Sustainability Week 2 Quiz 2 SolutionsIbrahim Ibrahim0% (1)

- Who Cares Wins 2005 Conference Report: Investing For Long-Term Value (October 2005)Document32 pagesWho Cares Wins 2005 Conference Report: Investing For Long-Term Value (October 2005)IFC SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- Climate Financial Risk Forum Guide 2021 Data MetricsDocument26 pagesClimate Financial Risk Forum Guide 2021 Data MetricsNirav ShahNo ratings yet

- Taxonomy Chile Report, A4, en VFDocument114 pagesTaxonomy Chile Report, A4, en VFRaphaela Mafra-BarretoNo ratings yet

- NAMA Guidebook: Manual For Practitioners Working With Mitigation ActionsDocument97 pagesNAMA Guidebook: Manual For Practitioners Working With Mitigation Actionssara stormborn123No ratings yet

- WEF Mobilizing Investment For Clean Energy in Brazil 2022Document20 pagesWEF Mobilizing Investment For Clean Energy in Brazil 20225tbmv7v8twNo ratings yet

- CT - November 2023Document22 pagesCT - November 2023f.jahin0803No ratings yet

- 10207IIEDDocument54 pages10207IIEDGabriela CornejoNo ratings yet

- Full-Advice-Text CoastalDocument55 pagesFull-Advice-Text CoastaljdboparaiNo ratings yet

- WEF IBC Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism Report 2020Document96 pagesWEF IBC Measuring Stakeholder Capitalism Report 2020Paulo Afonso Vieira PastoriNo ratings yet

- Localisation in Practice Full Report v4Document68 pagesLocalisation in Practice Full Report v4Summer Al-HaimiNo ratings yet

- Localisation-In-Practice-Full-Report-v4 Part 1Document20 pagesLocalisation-In-Practice-Full-Report-v4 Part 1Summer Al-HaimiNo ratings yet

- Blending Climate Finance Through National Climate FundsDocument64 pagesBlending Climate Finance Through National Climate FundsSettler RoozbehNo ratings yet

- Carbon Asset RiskDocument67 pagesCarbon Asset RiskRajasekhar WenigNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Our Built EnvironmentDocument56 pagesRethinking Our Built EnvironmentArqLucidioNo ratings yet

- Eco-Balance ReportDocument35 pagesEco-Balance ReportMubarakah JailaniNo ratings yet

- Alliance Target Setting Protocol 2021Document76 pagesAlliance Target Setting Protocol 2021IndraniGhoshNo ratings yet

- STAP GEF Delivering Global Env - Web LoRes - 0Document84 pagesSTAP GEF Delivering Global Env - Web LoRes - 0redmilaptop0836No ratings yet

- Future of Boards 1697588023Document60 pagesFuture of Boards 1697588023Dario GFNo ratings yet

- Designing A Sustainable Financial System Development Goals and Socio Ecological Responsibility 1St Edition Thomas Walker Full ChapterDocument52 pagesDesigning A Sustainable Financial System Development Goals and Socio Ecological Responsibility 1St Edition Thomas Walker Full Chaptersalvatore.martin420100% (6)

- Navigating Climate Scenario Analysis - A Guide For Institutional InvestorsDocument60 pagesNavigating Climate Scenario Analysis - A Guide For Institutional Investorsvaratharajan KaliyaperumalNo ratings yet

- Winter 2018 The Investment Gap That Threatens The PlanetDocument9 pagesWinter 2018 The Investment Gap That Threatens The PlanetArturo GregoriniNo ratings yet

- CPLC+ NetZero ReportDocument60 pagesCPLC+ NetZero Reportion dogeanuNo ratings yet

- Green Bonds For Climate Resilience State of Play 1638760083Document59 pagesGreen Bonds For Climate Resilience State of Play 16387600832h4v62n6wnNo ratings yet

- The Need For Climate-Forward EfficiencyDocument61 pagesThe Need For Climate-Forward EfficiencyJose AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Pathways To Resilience CCCPDocument68 pagesPathways To Resilience CCCPMohammed A. HelalNo ratings yet

- CPIC Blueprint Development Guide 2018Document88 pagesCPIC Blueprint Development Guide 2018Aaron AppletonNo ratings yet

- Nakelevu Et Al. 2005. Pacific Islands Community Based Adaptation To CCDocument44 pagesNakelevu Et Al. 2005. Pacific Islands Community Based Adaptation To CCMoses HenryNo ratings yet

- GIC ThinkSpace Climate Scenario AnalysisDocument29 pagesGIC ThinkSpace Climate Scenario AnalysisvbresanNo ratings yet

- I4CE ClimINVEST - 2018 - Getting Started On Physical Climate Risk Analysis 3Document88 pagesI4CE ClimINVEST - 2018 - Getting Started On Physical Climate Risk Analysis 3SenthilnathanNo ratings yet

- Urban Resilience and Climate ChangeDocument38 pagesUrban Resilience and Climate ChangeZuhair A. RehmanNo ratings yet

- Grant Workshop Bil 3 - 2022Document31 pagesGrant Workshop Bil 3 - 2022Kho Swee LiangNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Creating and Capturing Value in Open Eco-Innovation Evidence From The Maritime Industry in DenmarkDocument13 pagesChallenges of Creating and Capturing Value in Open Eco-Innovation Evidence From The Maritime Industry in DenmarkSamuel SilitongaNo ratings yet

- The Circular Economy and IA - PrimerDocument52 pagesThe Circular Economy and IA - PrimerRonald Abdias Sanchez GutierrezNo ratings yet

- A Framework and Principles For in Financing Operations: Climate Resilience MetricsDocument41 pagesA Framework and Principles For in Financing Operations: Climate Resilience MetricslaibaNo ratings yet

- NationalCarbonBudgetMX 2020Document143 pagesNationalCarbonBudgetMX 2020Cindy Calderon M.No ratings yet

- WEF Guidelines For Improving Blockchain's Environmental Social and Economic Impact 2023Document30 pagesWEF Guidelines For Improving Blockchain's Environmental Social and Economic Impact 2023carlos.loaisigaNo ratings yet

- Fabric WhitePaper A4Document54 pagesFabric WhitePaper A4Ahmed Ammar YasserNo ratings yet

- Case Studies On Climate Action: Climate Financial Risk Forum Guide 2021Document16 pagesCase Studies On Climate Action: Climate Financial Risk Forum Guide 2021Manjulika PoddarNo ratings yet

- Nature Related Assessment and Disclosure 1712921332Document88 pagesNature Related Assessment and Disclosure 1712921332marcusviniciuspeixotoNo ratings yet

- Co-Producing Urban Resilience Solutions: The Role of Power and PoliticsDocument32 pagesCo-Producing Urban Resilience Solutions: The Role of Power and PoliticsudbhavfestNo ratings yet

- ManualDocument44 pagesManualCarlos Josè GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Disaster Recovery Project Management A Critical ServiceDocument5 pagesDisaster Recovery Project Management A Critical ServiceKarla SanchezNo ratings yet

- Management - Effectiveness - Evaluation - in - Protected - Areas 2010Document102 pagesManagement - Effectiveness - Evaluation - in - Protected - Areas 2010Adrianne BasantesNo ratings yet

- Carbon Report - WEFDocument45 pagesCarbon Report - WEFN'Gandjo Wassa CisseNo ratings yet

- 3 TEFP Final-Report 160425Document321 pages3 TEFP Final-Report 160425Christian Yao AmegaviNo ratings yet

- Country Paper:: Dominican RepublicDocument101 pagesCountry Paper:: Dominican RepublicPablo Guillermo Coca GarabitoNo ratings yet

- Climate Finance in Bangladesh PDFDocument25 pagesClimate Finance in Bangladesh PDFGustavo FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Clearing The Air On The State of Carbon MarketsDocument3 pagesClearing The Air On The State of Carbon Marketsatifmehmood8642No ratings yet

- N4C The State of Nature Tech FinalDocument80 pagesN4C The State of Nature Tech FinalkenNo ratings yet

- Climate Finance Brief Definitions To Improve Tracking and Scale UpDocument9 pagesClimate Finance Brief Definitions To Improve Tracking and Scale UpMuhammad Jazib IkramNo ratings yet

- Agnes Wanjiku Muthiani Mba 2012Document80 pagesAgnes Wanjiku Muthiani Mba 2012ZachariahNo ratings yet

- Nature and Net Zero: in Collaboration With Mckinsey & CompanyDocument37 pagesNature and Net Zero: in Collaboration With Mckinsey & CompanyWan Sek ChoonNo ratings yet

- Green Building Lab Report Residential ENGDocument56 pagesGreen Building Lab Report Residential ENGDaniel Sunico LewinNo ratings yet

- Harga Karbon Dunia (WORLD BANK 2019)Document64 pagesHarga Karbon Dunia (WORLD BANK 2019)Arif Rachman Haqim100% (1)

- 3E Launch Meeting ReportDocument44 pages3E Launch Meeting ReportReos PartnersNo ratings yet

- ALN-Competency-Framework 2021 Final PDFDocument83 pagesALN-Competency-Framework 2021 Final PDFRafael OsunaNo ratings yet

- Guide To Monitoring and Evaluation v1 March2014 PDFDocument60 pagesGuide To Monitoring and Evaluation v1 March2014 PDFMetodio Caetano MonizNo ratings yet

- Investment Climate Reforms: An Independent Evaluation of World Bank Group Support to Reforms of Business RegulationsFrom EverandInvestment Climate Reforms: An Independent Evaluation of World Bank Group Support to Reforms of Business RegulationsNo ratings yet

- Social Business and Base of the Pyramid: Levers for Strategic RenewalFrom EverandSocial Business and Base of the Pyramid: Levers for Strategic RenewalNo ratings yet

- Hartley LifeCareDocument6 pagesHartley LifeCaretosproNo ratings yet

- Compro OlindoDocument16 pagesCompro OlindoMr Irfan Adhi PNo ratings yet

- WBG Econsultant2 - ToolDocument2 pagesWBG Econsultant2 - ToolCarolina MonsivaisNo ratings yet

- MEHP-1-SF-021 Risk Assessment Procedure (Rev. 2)Document15 pagesMEHP-1-SF-021 Risk Assessment Procedure (Rev. 2)Sarfraz RandhawaNo ratings yet

- Sustainability: Ethical and Social Responsibility DimensionsDocument7 pagesSustainability: Ethical and Social Responsibility DimensionsSaksham TehriNo ratings yet

- Trash Bin LabelDocument2 pagesTrash Bin LabelTintin Dimalanta LacanlaleNo ratings yet

- Sogo Group 4Document16 pagesSogo Group 4BabuEiEiNo ratings yet

- Leading SustainablyDocument209 pagesLeading SustainablyWertonNo ratings yet

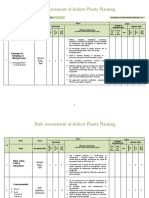

- Risk Assessment of Indoor Plants PlantingDocument5 pagesRisk Assessment of Indoor Plants Plantingطارق رضوانNo ratings yet

- Business Plan SampleDocument42 pagesBusiness Plan SampleClaudio EcheveriaNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics Environmental ScanningDocument3 pagesApplied Economics Environmental ScanningMary Antonette VeronaNo ratings yet

- OHS-PR-09-18 F04 (A) COSHH Assessment - ABRO SPRAY PAINTDocument2 pagesOHS-PR-09-18 F04 (A) COSHH Assessment - ABRO SPRAY PAINTShadeed MohammedNo ratings yet

- Name: Onyango Loyce AchiengDocument4 pagesName: Onyango Loyce AchiengOn Joro ZablonNo ratings yet

- Jump To Navigation Jump To Search: 3M CompanyDocument9 pagesJump To Navigation Jump To Search: 3M CompanyAman DecoraterNo ratings yet

- Environmental Management ReviewerDocument7 pagesEnvironmental Management ReviewerCyvee Gem RedNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Textile Materials in Interiors: July 2016Document13 pagesSustainable Textile Materials in Interiors: July 2016SUHRIT BISWASNo ratings yet

- CBMEI 2nd TopicDocument3 pagesCBMEI 2nd TopicRICA MAE ABALOSNo ratings yet

- Elements of Green Supply Chain Management: Virendra Rajput DR S.K. Somani DR A.C. ShuklaDocument3 pagesElements of Green Supply Chain Management: Virendra Rajput DR S.K. Somani DR A.C. ShuklaJoel ComanNo ratings yet

- Front Desk Grade 7 ExamDocument4 pagesFront Desk Grade 7 Examfranklene padillo100% (1)

- Siemens Gamesa Renewable Energy Company PresentationDocument14 pagesSiemens Gamesa Renewable Energy Company Presentationsafae zghNo ratings yet

- Accenture Development Partnerships in Kenya - AccentureDocument10 pagesAccenture Development Partnerships in Kenya - AccentureCIOEastAfricaNo ratings yet

- An Assignment On: Environmental Auditing & Eco - MarkDocument11 pagesAn Assignment On: Environmental Auditing & Eco - MarkDeonandan kumarNo ratings yet

- OPER8340 - Assignment N3 Final Draft SubmissionDocument3 pagesOPER8340 - Assignment N3 Final Draft SubmissionThiyyaguraSudheerKumarReddyNo ratings yet

- Mock 4 CaseDocument5 pagesMock 4 CaseRashedul HassanNo ratings yet

- Minor Projecty Green MarektingDocument19 pagesMinor Projecty Green MarektingAshutosh MishraNo ratings yet

- DBCL C2C Final 08 09 2020Document336 pagesDBCL C2C Final 08 09 2020Shailesh Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Multinational Corporations - A Study DR V. Basil HansDocument15 pagesMultinational Corporations - A Study DR V. Basil Hanskhushi DuaNo ratings yet

- Module 2 - Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityDocument4 pagesModule 2 - Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityJOHN PAUL LAGAO100% (3)

- Monthly Report - June 2023Document23 pagesMonthly Report - June 2023Rowie LimbagaNo ratings yet

PeaceDepartment Report v08 MSG-LR

PeaceDepartment Report v08 MSG-LR

Uploaded by

Derrick Andika JudaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PeaceDepartment Report v08 MSG-LR

PeaceDepartment Report v08 MSG-LR

Uploaded by

Derrick Andika JudaCopyright:

Available Formats

1 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

Place-based

Transition Funds:

A PLAYBOOK FOR SYSTEMIC

PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

2 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

About the Carbon Residency Document Authors

The Carbon Residency is a collective of subject matter Howard, Racheal (Project Lead)

experts in finance, climate, systemic impact, sustainability, Moroney, Matthew (Metabolic)

and social justice, formed by the Peace Department, Von Ritter, Yihana (Align Impact)

a non-profit committed to peace through sustainable Wainstein, Martin (Open Earth Foundation)

development. The first Carbon Residency was hosted at

Foundation House in September 2023, and convened by Sponsored by

the Peace Department and the Open Earth Foundation.

The Peace Department

The purpose of this collective is a shared commitment Sternlicht, James

to rapidly decarbonizing the planet through the

implementation of low carbon technologies with social Hosted by

equity and community uplift at its core. The outcome of

Foundation House - Greenwich, CT

the first Carbon Residency identified a need for a holistic

Sternlicht, Mimi

framework in decarbonization finance and portfolio

Zimmerman, Richard

construction.

Between November 2023 and April 2024, members of With special thanks to

the Carbon Residency developed the research, review Alvarez de Jesus, Natalia (The Peace Department)

and creation of the Playbook presented in this document. Bezer, Liliana (Metabolic)

This work was facilitated thanks to a grant from the Ilieva, Maria (Metabolic)

Peace Department.

Reviewers

Acknowledgements

McCue, Andrew (Metabolic)

The content of this Playbook builds on the foundation Scala, Mike (The Peace Department)

of knowledge and the continuing dialogue that we hold

with our colleagues and peers in the systems change and

sustainability space. In particular, in this work we have

Advisors

built upon an understanding that we have collectively Carrero-Martinez, Franklin (National Academy of Sciences)

accepted with members of the Systemic Climate Action Engel, Jayne (Dark Matter Labs)

Collaborative: that lasting systems change seems to require Gladek, Eva (Metabolic)

place-based transformation portfolios of complementary Kalia, Raj (Dark Matter Capital Systems)

and reinforcing activities. This Playbook zooms in on

capital formation for place-based transformation, which is First Publication and License

a necessary step in any portfolio-based approach, such as This document was published in April 2024 as a first version

the one defined for urban transformation by the Circular with an open Request For Comment. Provide comments

City Coalition. We also recognize in this work that this is to info@peacedepartment.global. This playbook should

one of several enabling conditions required for success. not be used as-is for the creation of financial vehicles and

We hope this Playbook serves as a practical method to instruments; these require significant technical and legal

advance our collective efforts in systems change. expertise that this document is not intended to provide.

This document and its content are published under a

Members of the Systemic Climate Action Collaborative Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

include: Bankers Without Boundaries, B-Team, CJ-JT,

Climate-KIC, Club of Rome, Community Arts Network, This Playbook is the first version, accompanied by a

Dark Matter Labs, Democratic Society, IIED, Metabolic, technical appendix. it is intended to serve as an evolving

Open Earth Foundation, Pyxera Global, Reos Partners, resource to be validated with a pilot and informed by

SystemIQ, The Solutions Union and Vinnova. the learned experiences of communities, businesses,

agencies, and individuals.

Organizations and experts that have provided inputs to

this playbook include: Chad Frischmann (GSA), Peter Boyd

(Yale University), Eva Lalakova (Metabolic), Ivan Thung

(Metabolic), and Chris Monaghan (Metabolic).

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

3

Index

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4

01. INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO 6

CONSTRUCTION FOR CARBON EMISSION REDUCTIONS

The Case for Place-Based Transition Funds 9

02. REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION 10

FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

Sourcing, Evaluating, and Scoring 11

Comparative Analysis of Decarbonization Frameworks 12

Blended Finance: Using Loan Guarantees to Attract Market-rate 17

Summary of General Findings 18

03. PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS: SCORECARDS AND 20

INTEGRATED FRAMEWORKS

Geographic Scorecard 21

Portfolio Design 24

Project Scorecard 26

Steward Ownership Model 29

04. PLACE-BASED CLIMATE TRANSITION FUNDS 30

Stage 1: Geographic Selection 32

Stage 2: Portfolio Design 33

Stage 3: Project Sourcing and Evaluation 34

Stage 4: Capital Deployment and Scaling 35

Stage 5: Implementation and Replication 36

Considerations for Playbook Implementation 38

05. CONCLUSIONS 42

Further Playbook Opportunities 43

Proposed Next Steps 44

REFERENCES 45

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Executive Summary

The climate goals set by the 2015 Paris Agreement 1. Geographic Selection Scorecard:

require an unparalleled pace of emissions reductions. Presenting key criteria and rubrics to identify and

This scale of transition requires a scalable, yet compare the current state of governance, economy,

standardized method to accelerate economic potential for uplift, and nature for a particular

transitions one place at a time. Investors are looking subnational geography.

to join the climate transition, but seek market rate

returns. Projects essential for climate mitigation 2. An Integrated Framework for Portfolio Design:

and resilience are limited by funding and adequate A blueprint to transform subnational climate action

technical assistance. Low-carbon infrastructure plans into actionable, structured portfolios framed by

and innovative ventures offer promising solutions material flows and systems change.

for systemic transition, but the risks they carry

are a barrier for the investment required to bring 3. Project Screening and Scorecard:

projects to bankability while new markets are hard to A scorecard to evaluate potential portfolio projects

catalyze, even with the proper incentives. There is a on the basis of the project’s viability, the benefits it

critical need for innovative financial mechanisms and has on its environment, its potentially deleterious

high-quality project development to vitalize these impact on its environment, its financial wellness and

new opportunities. considerations for its socio-cultural environment.

While it has been readily acknowledged that new 4. Loan Guarantees to De-Risk Investments:

approaches are needed to finance this transition, A method of portfolio construction using Loan

there are no formalized guidelines or clear process for Guarantee Funds (LGFs) to build flexible capital stacks,

designing, financing, and implementing a coordinated bridge investment gaps, and attract diverse investor

effort for policymakers and investors seeking to classes.

activate capital for climate action at a geography-wide

scale. Local governments are key actors to implement 5. Community Empowerment Through

climate transition plans for their jurisdictions, but often Steward-Ownership:

lack the budget and financial capacity to fund them. A blueprint for replicability and continuity with steward-

Traditional finance often optimizes for single proven ownership models, where local nonprofits can own a

assets, such as solar, rather than multiple assets that portion of the underlying portfolio assets, to balance

align with community needs. profit motives and empower communities after an

initial external capital influx.

To address the disconnect between local communities

and finance for climate transitions, the Peace This Playbook introduces this method as a tool for

Department’s Carbon Residency program advances an fund originators, investors, mayors and governors, and

approach based on a “Place-based Transition Funds” community leaders to formulate unified, attractive,

which can use this playbook for constructing their and impactful place-based transition portfolios. It

systemic portfolio. The steps in this playbook represent also serves as a resource for philanthropic program

a replicable method for financing the transition of officers, fund managers, and family offices engaged

distinct places, like cities, regions and island economies. in climate finance, by providing opportunities for

creating bankable decarbonization projects that

It was designed by integrating climate frameworks deliver profit, environmental, and social benefits. This

that align Paris Agreement goals with local contexts, process strategically guides the flow of investments by

and uses systems thinking to pinpoint and prioritize designing resilient and effective investment portfolios

enabling conditions for investable projects and that align with local climate initiatives, policy goals and

interventions. Figure 1 below further illustrates the community needs.

Playbook stages and its internal steps. Key highlights

and unique components presented in this work include:

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

From a list of possible locations, apply the Evaluate existing climate action plans and policies, Establish or update the jurisdiction's

Geographic Scorecard for each and select the most identifying strategies that may still need to be baseline assessment of GHG emissions

attractive based on investment and impact potential. developed for the host jurisdiction. and material flows assessment.

Assess the climate action and community plans, Map synergies between existing stakeholders, Establish the structure of the portfolio based on the

or conduct them if they are not done. Create 2-3 ecoregional needs and climate action sectors. interventions sectors from the climate action and

scenarios for reaching net zero and establish a Highlight gaps and opportunities to insert projects transition plans. Define which sectors should have

strategy for each with measurable key results. that align with investment and impact criteria. more or larger projects and incorporate synergies.

Through open calls, stakeholder consultations, Apply the Project Scorecard to the sourced Assemble local and global business and

and partnerships, source and invite existing projects, to understand their strengths, scientific experts, supporting the cohort’s

projects for evaluation and participation, requirements and priorities. Gather stakeholder execution capacity to develop interconnected

categorizing them based on the portfolio sectors. feedback on projects to finalize the initial cohort. and profitable business models.

Source investors for the blended Involve local stakeholders and nonprofits Perform continuous tracking of the portfolio's

capital stack. Develop the loan identified in previous steps to become steward projects using the project evaluation scorecards,

guarantee fund and begin issuing to owners within the project portfolio as it stakeholder feedback and updating the

key projects for derisking. transitions from investor to community co-owned. geography's baseline comparison.

Oversee the effective implementation and project Document and share success and learnings, and Consolidate a global facility to support the creation,

construction, ensuring timeline and identifying increase the library of common project templates cross-learning and replication of the transition funds.

opportunities for collective optimizations. like legal documentation and financial models. Support the development of fund-of-funds and even

Transition ownership with maturation. Encourage replication in similar jurisdictions. financial instruments from pooled projects.

Fig.

Playbook for Place-based Transition Funds. Visual summary of the five stages and substeps of the Playbook.

1 While presented in sequential manner, several processes may occur in parallel and can extend through

multiple stages, such as involving steward owners and sourcing projects.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

6 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

01

Introduction to

Place-Based Portfolio

Construction for

Climate Transitions

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

7 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

The existing financial system still lacks the required Universalizing low-carbon transitions need to be

mechanisms to fund the complex transition of cities mainstreamed into unaddressed markets that are

and communities in the face of climate change. High- deemed too risky, costly, or difficult to abate without

return expectations lead investors to overlook small- adequate support. Individual businesses and consumer

scale, innovative climate projects. Obstacles like choices are disempowered, but in aggregate, the

technological and regulatory uncertainties, lengthy economics can scale and projects may be derisked,

approval processes, and a lack of attractive financial such as mini grids and virtual power plants.

options for climate projects compound the problem.

There is a pathway to commercial viability and

Although philanthropic and public funds could financial engineering through loan guarantees, offering

mitigate these gaps through credit enhancement, such investors’ protection against downside effects as the

mechanisms are vastly underused. Current policies, technologies and business models demonstrate their

including fossil fuel subsidies and tax structures, capabilities over time.

further tilt the market against decarbonization efforts,

with little hope for the swift regulatory changes The table below encapsulates the categorized risks and

required to address these challenges within the impediments hindering investment in crucial climate

necessary timeframe. initiatives at the local scale, reflecting the need for

strategic, systemic solutions in climate finance.

Through research and practical experience, we have

identified several challenges in climate finance that

pose real and perceived risks to effective investment

in decarbonization efforts. Our findings suggest that

the majority of global decarbonization efforts are

concentrated into specific, familiar sectors that are

heavily marketed and may be perceived as low-risk

investments, such as software, solar panels, and

electric cars, excluding more transformative projects.

This discrepancy alludes to a gap in climate finance:

the issue is not merely a shortage of capital but a lack

of investable projects that can simultaneously achieve

financial returns and impactful climate action.

While the availability of viable projects is a predominant

hindrance to low-carbon transitions, a number of

factors contribute to the bottleneck. Transformational

climate actions are often concentrated into politically

progressive jurisdictions and affluent communities in

both the global north and the global south.

Low-income and disadvantaged communities

preclude participation due to prohibitive costs or

poor credit. Small island developing states (SIDS)

are most negatively impacted and less resilient to

climate change, but many are paradoxically reliant

on fossil fuels for independently run enterprises in

transport, agriculture, and tourism (IMF). Rural and

disaggregated projects that are interconnected to

larger infrastructure projects, such as behind-the-

meter energy generation and load flexibility like smart

appliances and thermostats, can be hard to finance.

Information asymmetry and the nascency of unproven

markets are additional burdens for investment.

Overall, projects with quantifiable impacts struggle

to get access to credit or deliver market-rate returns,

especially in periods of high interest rates and record-

setting public equities markets.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

8 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

Table

1 Real and perceived risks identified as barriers for climate transition finance.

Real and perceived risks Impediment Risk category

Unstable politics Prevents investment

Limited subnational

Reduces amount of blended capital

government budget

Unstable macroeconomics Cost of capital risks

Land leases and benefit Stalled projects and potential legal

sharing agreements problems

Delays rolling out climate Increases project risk and weighted average

incentive policies cost of capital

Need for new infrastructure

Large capital expenditures

development

Investors tend to favor mature markets with

Investor Transaction Costs

low fees

Investment thresholds between investors,

Information Asymmetry

entrepreneurs, and project developers

Trust and Willingness Between

Limits coordination and cooperation

Stakeholders

Labor Capacity Lack of qualified labor force

Foreign vs Resident Executive

Execution risk (legal signatories, etc)

Team

Untested and Unproven Early-

Lack of investor interest

stage Ventures

Political Financial Social

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

9 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

THE CASE FOR PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

By combining strategic geographic selection, policy Finally, utility-scale energy, construction, and real-

alignment, robust project evaluation, and catalytic estate development are politically coveted and can

capital structures, this Playbook illustrates how to prop up moral hazards or anti-competitive bids, which

generate investment portfolios optimized for specific can be hard to counter when power is centralized.

local environments which maximally target climate

transition opportunities while providing enduring value Place-based frameworks can help spread economic

to the local community. costs, distribute political accountability, and create

networks of symbiotic stakeholders. Energy, housing,

The benefit of place-based investment portfolios is and food security can be strengthened through place-

that it meets a much needed demand to fund often based efforts by supporting enabling conditions that

neglected areas that are essential to support or decentralize energetic loads such as mini-grid systems

network broader decarbonization pathways. Countries and empower food resilience with locally owned

play a key role for large infrastructure projects, but regenerative farming. Local bodies are closer to the

they are often an impractical scale for managing such specific climate-related challenges and opportunities

projects at the local level. Cities are better situated within their territories, making them more agile actors

to implement low-carbon transitions, demonstrated in implementation of climate action. However, they

by the quantity of funding programs and climate often face financial constraints, lacking the necessary

implementation plans concentrated around municipal support and resources to fully implement their climate

climate solutions. action and social improvement plans.

Cities face inherent challenges,however, because they By synchronizing investment with governance of

are open systems composed of complex infrastructure subnational entities, capital allocators rely on local

networks that have many materials and capital flowing insights to support projects that offer tangible benefits,

through them. Moreover, cities face a centralization ensuring progress toward both local and global climate

problem, where resources can be wholly concentrated targets. This method emphasizes integrating private

toward specific interests or demographics while others capital, both philanthropic and market-rate, into the

are underserved. Cities can also apply a “one size fits fabric of local climate action initiatives for the creation

all” approach to a location that has many facets and of a collaborative financial ecosystem to meet the

diverse needs. Upgrades or maintenance on smaller, nuanced demands of regions and municipalities.

poorer funded elements of the system, such as

enabling infrastructure, means that small neglects can

turn into enormous problems for the entire system.

Cities also tend to grow, where population growth can

outpace the rate of municipal improvements, putting

significant pressure on public sector infrastructure.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

10 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

02

Review of Existing

Decarbonization

Frameworks and

Finance Models

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

11 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

SOURCING, EVALUATING, AND SCORING

Climate action frameworks, including decarbonization classifications and processes, designed to help achieve

frameworks, are specific strategies from jurisdictional, the emission goals of the Paris Agreement. We took the

institutional, and individual actors committed to take following steps for sourcing, evaluating, and scoring

meaningful action toward their climate goals. identified frameworks:

The primary objective of this work was to generate 1. Sourcing: We explored decarbonization frameworks

insights that would transform unbankable projects to by researching the spectrum of global strategies.

viable works with realizable systemic transition actions We conducted literature reviews and interviewed

aligned with the Carbon Residency’s goals: systemic subject matter experts and practitioners in the

decarbonization, financial innovation, climate justice, field. From this, we created a review that evaluated

and measurable community uplift. established and innovative approaches.

2. Classification: Next, we organized the collected

To achieve these goals, we identified transferable

frameworks by decarbonization sector or theme.

strengths, methodologies, and lessons learned from

This helped sort them into clear groups for easier

market failures to develop an integrated Playbook,

analysis, based on their focus areas, audience,

encompassing stakeholder engagement strategies, pilot

geography, and principles.

testing plans, and a roadmap for scalable replication.

3. Deep Review: We closely examined each framework

We analyzed over 30 city and nationwide decarbonization through its documentation and by talking with

action plans, sectoral decarbonization frameworks, and creators and users. This mix of theoretical and

geopolitical, humanitarian, and economic frameworks practical insights gave us an enhanced lens of how

to assess impacts, failures, and policies. Interviews each framework functions.

were conducted and programs evaluated for systemic 4. Evaluation and Scoring: Finally, we evaluated

sustainability, circularity, and innovative early-stage and scored each framework against an Evaluation

impact ventures to model and capture learnings (see Rubric reflecting the Carbon Residency’s goals. The

Technical Appendix for scores and methodologies). scoring, presented in comparative tables, helped

identify the frameworks best suited to guide our

We consider decarbonization frameworks as any integrated decarbonization approach.

information structure, such as strategies, roadmaps,

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

12 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF DECARBONIZATION

FRAMEWORKS

Socio-economic and community uplift were important to 3 (see Technical Appendix). All frameworks met some

elements for our selection process, therefore of the criteria for our selection process.

considerations went beyond some decarbonization

frameworks. These frameworks were scored based on The frameworks with highest scores and greatest

their completeness, relevance, and the degree to which alignment with all of the project’s goals were City

they encompassed the essential pillars of project viability, Journey with The Global Covenant of Mayors for

environmental impact, finance, and socio-cultural factors Climate & Energy (GCoM), Green Climate Cities ICLEI,

(Table 2) with evaluation scores following a rubric from 1 and Global Solutions Alliance (GSA).

Figure Climate Action & Decarbonization Frameworks reviewed. Depiction of some of the 30+ frameworks that were

2 reviewed for the development of this framework, categorized by type of program.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

13 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

Table Review of existing climate action frameworks, a description of their program, and our evaluation of their

2 relevance. Detailed scores and methodologies are found in the Technical Appendix.

Framework Description Evaluation

Decarbonization Roadmaps for a climate action journey of a geography, such as a city or nation.

C40 Climate Framework The Cities Action Plan (CAP) Offers resources for inventorying emissions,

Framework is a guide for cities to setting targets, planning actions, and

develop and implement climate monitoring progress, but needs other action

action plans aligned with the goals plans to be complete.

of the Paris Agreement.

CityCatalyst Digital OpenEarth’s CityCatalyst presents Relevant component to ensure data

Roadmap a digital and data interoperability efficiency for scaling and automating

framework for subnational project prioritization by sector and impact

governments to connect data monitoring. Requires further standards for

throughout the climate action integrations and more finance overlap.

roadmap (GHG inventory, to action

plans, portfolio, finance, and

implementation stages).

City Journey The Global Covenant of Mayors Focused on local capacities with good

(GCoM) for Climate & Energy (GCoM) is assessment methodologies, strong data

the largest global alliance for city management and reporting. Global reporting

climate leadership, built upon the standards set a good basis for comparative

commitment of over 11,500 cities actions for different geographies.

and local governments.

GreenClimateCities (GCC) The Green Climate Cities is a Provides a process-oriented methodology

ICLEI program led by ICLEI delivering a with a multi-jurisdictional design that

process for cities to move toward enables local and regional governments to

climate neutrality, tested by cities develop solutions integrated for entire urban

engaged in the Urban-LEDS project. systems.

ClimateView’s Transition Framework and platform to evaluate Methodologies integrate from physics,

Elements city projects for decarbonization behavioral psychology and economic

based on sector-specific science. “Imperfect” and “good enough”

breakdowns. data are incorporated to broaden scope.

Good for city-level decarbonization but

requires integration with financial tools.

Exponential Roadmap The Exponential Roadmap Initiative This framework is focused on professional

is a partner of the UN Climate services providers to assess customers and

Change High-Level Champion’s align businesses. Its sector analysis has

Race to Zero and is a founding updated models for Nature-based Solutions

partner of the 1.5°C Supply Chain and Food Consumption.

Leaders and the SME Climate Hub.

LEED for Cities The most widely used green Leed v5 is an updated model which

building rating system which has addresses equity, health, ecosystems and

a program that measures, scores, resilience. Its sectoral scope is mostly

and certifies sustainability in urban focused on buildings and energy.

development and infrastructure

projects.

Project Drawdown The Drawdown Roadmap It is a 5 part plan for existing climate

was developed by scientists, change solutions across sectors, time, and

policymakers, and corporate geography with co-benefits. Needs new

executives. updates.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

14 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

USGBC and RMI The U.S. Green Building Council and Outlines key actions to accelerate the

Rocky Mountain Institute conducted decarbonization build sector addressing

a sectoral analysis on the U.S. embodied carbon emissions for a full

building construction sector. life cycle. Useful for identifying the hot

spots that will most benefit from active

reductions.

Circular Economy and Materials

Circular City Actions Circular City Actions is developed The program initiated a repository of case

(Ganbatte) by Circle Economy, ICLEI, and studies on the circular economy in cities

Metabolic, in partnership with the focused on direct circular handling of

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. It is material and energy flows: closing loops,

based on the 9R Framework. extending product lifecycles and increasing

usage intensity.

Circular Buildings The Circular Buildings Coalition is an Projects are chosen on the basis of public

Coalition Innovation Challenge for circularity value, transition alignment, feasibility,

in the built environment supported org-solution fit, uniqueness and impact,

by the Laudes Foundation and employing Building Passports, an inter-

chartered by Metabolic, WGBC, communicable database for all building

Circular Economy Building Council, products. Success is expected to come from

World Business Council, EMF, a funnel effect - where a small amount

Circular Org. of money is given with successive larger

disbursements, done in phases.

Circular City Coalition Action framework for private Aligned with CTFs by bringing the

sector to co-invest with local government, corporate investors,

cities, in partnership with the community leaders and philanthropy to

local community, to achieve work together on systemic transitions.

decarbonisation, material While it mentions the creation of

circularity and social uplift. CCC is a portfolios, it doesn’t have a clear

consortium led by three governing methodology or play yet.

partners: Pyxera Global, Metabolic,

and Climate-KIC.

EIB Circular City Center C3 is a resource center within the They provide resources, advisory, and aid

(C3) EIB to aid the circular transition. toward finding funding for circular projects.

Project and Solution Evaluation Frameworks

CRANE Tool and Prime Prime Coalition (Prime) is a tool Strong in future impact assessment with a

Coalition to establish industry standard primary focus on emissions reductions.

terminology. CRANE is an open

source tool to assess the emissions

reductions for early-stage

investors, incubators, accelerators,

government agencies, and large

corporations.

EU Taxonomy for Developed by the EU Commission. The taxonomy is a common classification

Sustainable Activities system for sustainable investment for

avoidance of doubt in defining terms.

Global Solutions Alliance GSA is an open-source non-profit GSA is a forked version of Drawdown and

(GSA) data repository. Crane and presents strong systemic tools

designed to dynamically adopt new open-

sourced solutions. Analytic projections include

interaction effects to avoid double counting.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

15 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

SDG Impact Assessment The SDG Acceleration Toolkit is a It is comprehensive and adaptable and

Tool (UNDP) compendium of tools for analyzing focuses on identifying risks and building

system interconnections and resilience, but may require simplification for

enhancing “policy coherence”. Its practical use.

Climate Action Impact Tool is an

online application for development

practitioners and the private sector.

Systemic and Socio-economic Impact frameworks

Converge Network Toolkit The Toolkit is a companion to the A guideline coupled with Hats Protocol,

book Impact Networks by David a decentralized network to support

Erlichman. organizations, communities, and collectives

delegate roles and organize around systemic

thinking principles.

Donella Meadows IISSD DM Indicators Information Systems DM uses a compilation of indicators from

For Sustainable Development is the UN Statistical Division, the OECD, the

formulated on past work from European Environment Agency, Eurostat,

Balaton Group, UNCSD, Natural and The Project on Indicators of the

Human and Social Capital from the Scientific Committee on Problems of the

World Bank. Environment to identify leverage points and

interventions for systemic change.

The Millennium Challenge MCC is an independent U.S. MCC’s process uses indicators that are

Corporation Government agency that provides developed by independent third parties, are

sizable time-limited grants to policy-linked, and have a clear theoretical

promote economic growth, or empirical link to economic growth and

reducing poverty, and strengthening poverty reduction.

institutions.

New Project and Ventures Approaches

Climate KIC Open Climate KIC is an accelerator, They identify, source and track projects and

Innovation Calls incubator, provides seed funding, support innovation by effectively leveraging

and assistance to start-ups and grants. They build initiatives such as

SMEs and is supported by the Climathon and Climate Launchpad.

European Institute of Innovation

and Technology.

Fresh Ventures Studios Fresh is a start-up studio, talent and Addresses market challenges and

venture builder initially co-founded empowering “stewarded-owned ventures”

by Metabolic to transform the food to achieve product to market fit, systems

system. change, and follow-on funding. Fresh has

tried to create a blueprint for its frameworks

and started Rootical in Uganda this year but

is not replicable at present.

Systemic Venture The Metabolic Ventures Arm A contextual specific design tool using

Framework created a systemic venture “lagging indicators” to quantitatively

framework to design, support, measure impact for systemic approaches for

assess, and improve ventures that early-stage ventures and projects.

create transformative impact by

design.

Financial Alignment Programs with Paris Agreement

EIB Paris Alignment The European Investment Bank is Establishes a low carbon framework to align

Framework a framework specifically designed financing activities and establish criteria for

to align with the goals of the Paris EIB funding eligibility. Useful for financial

Agreement. structuring.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

16 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

EU Action Plan for Developed by the EU Commission’s It is strong in financial aspects but less

Sustainable Growth Joint Research Center to facilitate adaptable to local community-focused

the financing of sustainable projects.

economic growth.

Green Climate Fund The GCF Investment Framework helps Aids in financial structuring for climate

create alignment with co-investors, related projects and works with accredited

the private sector, other climate funds entities for GCF-funded projects.

and development banks.

IFC Policy on The International Finance Provides a comprehensive performance

Sustainability Corporation from the World Bank standards assessment for environmental

Group’s Environmental Health and and social risks, with generalizable

Safety Guidelines are technical guidelines. Recent updates provide

guidelines coupled with their quantitative instruction.

sustainability policies to assess risks

of projects.

OECD Framework The Office for Economic OECD identifies the gap between

To Decarbonize The Cooperation and Development existing frameworks and shortfalls of

Economy established a framework to existing emissions targets with specific

align with the goals of the Paris considerations for broad economic and

Agreement. social issues.

TAP ICLEI ransformative Actions Program TAP catalyzes additional capital flows for

(TAP) is a 10 year global initiative low-carbon and climate-resilient urban

embedded within the scope of the development infrastructure concepts into

Local Government Climate Roadmap mature and bankable projects ready for

and in support of the Compact of financing and implementation.

Mayors and the Compact of States

and Regions.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

17 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

BLENDED FINANCE: USING LOAN GUARANTEES TO

ATTRACT MARKET-RATE CAPITAL STACKS

Loan Guarantee Funds (LGFs) are a critical tool to We compare three public and three private LGFs,

scaling climate finance, especially for projects that are highlighting relative tactics to de-risk investments and

difficult to finance due to geographic considerations, attract capital (Table 3). We examine the public sector

management perceptions, testing new technology, and via African Development Bank’s efforts to mitigate

innovative governance structures. Loan Guarantees investment risks in sustainable projects in Africa, the

are a type of credit enhancement that allows an entity European Investment Fund’s SME support in Europe,

to obtain financing at better terms while minimizing and USAID, showcasing how LGFs can stimulate green

risks for investors. By reducing the risk, cost of capital innovation in varied geographies with different risk

is reduced, increasing the chance of more successful profiles and political perceptions. We also consider the

transition projects. Credit guarantee facilities with private sector through Guarantco, MCE Social Capital,

standardized contracts have the potential to mobilize and Shared Interest in applying LGFs for private capital

6-25 times more financing than loans (CPI, 2023). in blended finance structures to meet evolving missions

and emerging markets. A more detailed overview of

each fund can be found in the Technical Appendix.

Table Loan Guarantee Facility Comparative Table. The table includes three public and three private structures with

3 maximum loan coverage, maximum tenor length, leverage ratio, and guarantee fee, where available. All entities

provide technical assistance. The table highlights which entities provide loans and guarantees as opposed to just

guarantees.

Name Type Types of Guarantees Guarantee Terms Loan Technical

Provisions Assistance

Public Loan Guarantee Facilities

African Public Currency Guarantee, • Loan Guarantee: 75% Yes Yes

Development Partial Credit Guarantee, • Maturity: up to 25 years

Bank Partial Risk Guarantee • Guarantee Fee: 0.8%

• Upfront Costs: 0.25%-1%

European Public Counter-Guarantees, • Loan Guarantee: <80% Yes Yes

Investment First-Loss Guarantee, • Guarantee Fee: 0.75%-

Fund Loan Portfolio 1.2%

Guarantee, Partial Credit • Max Guarantee: €7.5M

Guarantee

USAID Public Bond Guarantee, Loan • Loan Guarantee: 50%-75% Yes Yes

Development Portfolio Guarantee, • Maturity: 2-20 years

Credit Partial Credit Guarantee, • Leverage Ratio: 1 to 30

Authority Portable Guarantee

Private Loan Guarantee Facilities

GuarantCo Private Currency Guarantee, • Loan Guarantee: <100% No Yes

First-Loss Guarantee, • Maturity: <20 years

Joint Guarantee, • Max Guarantee: $5M to

Liquidity Extensions $50M

Guarantee, Partial Credit • Leverage Ratio: 1 to 3

Guarantee, Partial Risk

Guarantee

MCE Social Private Credit Guarantee • Loan Guarantee: 100% Yes Yes

Capital • Maturity: 10 months to 5

years

Shared Private Partial Credit Guarantee • Loan Guarantee: <75% No Yes

Interest • Leverage Ratio: 1:3

• Funds Called to

Guarantees Issued: 7.8%

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

18 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

SUMMARY OF GENERAL FINDINGS

Our reviews of decarbonization frameworks illustrate • Place-based Strategies and Policy Cohesion: The

challenges and insights of existing methodologies, viability of decarbonization strategies are deeply

when applying them to a specific, based-placed rooted in the socio-political and economic fabric

implementation (Technical Appendix). These of each geography. This insight guides us to not

underscore the complexities of the field and guide just map scenarios but to weave our strategies

considerations to shape a Place-based Transition into the local policy tapestry, ensuring alignment

Fund: embracing early and consistent, policy that supports existing, and underfunded climate

alignment, sector-specific insights, and integrating commitments.

understanding of geographical and market dynamics.

• Market Failures: Market failures can be amended,

Key gaps in existing frameworks include community

not simply by policy fixes or traditional economic

social and economic empowerment strategies

corrections, but through innovative solutions. We

and metrics, system mapping for understanding

aim to establish mechanisms that can predict,

synergies across projects, and tactics to address

internalize, and turn externalities into opportunities

market failures.

for innovation and growth.

GEOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES PROJECT PORTFOLIO

• Early-Stage Funding in a Local Context: Risk EVALUATION

assessment for early-stage funding often lacks

• Anticipating Technological and Systemic

nuanced understanding of a local environment,

Uncertainty: When reviewing decarbonization

political willingness, and the true obstacles that

projects, there are recognized difficulties in planning

result in a failure to launch. Developing community

around the regional accessibility of emerging

relationships can help to contextualize local needs

technologies and how they operate in the local

while building implementation support. Relationships

context. More critically, we must anticipate the

expand solutions that can only be revealed through

systemic repercussions—both known and unknown—

the context of community trust.

that these projects and technologies have on our

• Geography Scale Selection: Selecting an appropriate overall strategy.

geographical scale for applying a Place-based

• Context-Specific Models: The challenge is tailoring

Transition Fund is key, as it expands or constrains

portfolios to the intricacies of regional data

resources, timescales, governmental support, and

landscapes, usability needs, and the distinctive

the capacity for measurable community uplift that

transition needs of sectors and geographies. This

endures beyond the intervention. While local climate

insight leads the Playbook to be sensitive to these

policy are important, equally as important is the

sector needs and be contextually intelligent.

relationship between government, local residents,

and surrounding political jurisdictions. Ensuring a • High Level Thinking vs Real World Implementation:

standardized approach does not alienate or neglect Many frameworks address theoretical or “perfect

any part of a community is critical. world” scenarios, rather than addressing real

obstacles that are often far more entrenched, hard

• Candidate Reach for Project Pipeline: The challenge

to define, and result from perception or relational

of finding investable project pipeline goes beyond

dynamics. Cognitive biases, attributional errors,

simply reaching candidates for funding. It is a broader

and misaligned incentives are often ignored and

issue of enabling talent to progress in challenging

go unaddressed, stymying actions and creating

environments, where actors are often pioneers, and

implementation gaps.

supporting their successful execution. Information

exchange and avoidance of error replication is often • Sector-Specific Challenges and Opportunities:

hard due to a lack of supporting communication Implementing infrastructure at varying scales is

networks between small scale project developers complex due to differing phase-outs for aging

and entrepreneurs. Information sharing is the first infrastructure, unaligned expiration dates, and

step to enabling support and course correction. financing timelines on networked infrastructure,

centralized planning that overlooks community

needs, and soft corruption and anti-competitive bids

from major contractors.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

19 REVIEW OF EXISTING DECARBONIZATION FRAMEWORKS AND FINANCE MODELS

• Strategic Alignment with Climate Goals: The IDENTIFIED RISKS

construction of investment portfolios must be

strategically aligned with science-based targets • Execution Risk: In the context of Place-based

and international climate agreements. This ensures Transition Funds, execution risk embodies the

that investments are directed towards projects that challenges associated with project delivery, from

contribute meaningfully to global climate objectives. inception through to operational stages. This includes

potential delays due to regulatory hurdles, logistical

• Transparency and Due Diligence: Developing constraints, or unforeseen environmental impacts

transparent criteria for asset selection and balancing that could derail project timelines or inflate costs.

within portfolios, alongside open due diligence

protocols, enhances the credibility and attractiveness • Market risk: Given the evolving nature of green

of investment opportunities. This fosters a more technologies and sustainable practices, market risk

inclusive and trustworthy climate finance market. is a significant concern. Fluctuations in technology

costs, shifts in consumer demand, or changes in

• Diversified Portfolios: Incorporating a mix of subsidy regimes can impact the financial viability of

different projects with varying risk profiles is not projects within the portfolio.

simply an exercise in diversification, but provides

enabling conditions for a variety of infrastructure • Financial Risk: Financial risk refers to the uncertainties

sizes and project types. funding and liquidity surrounding funding availability,

interest rate fluctuations, and the overall cost of

capital. These factors can significantly affect the

VALUE OF LOAN GUARANTEE ability to finance projects at competitive rates,

impacting the overall investment appeal.

FUNDS

• Regulatory Risk: The dynamic regulatory landscape

• Risk Mitigation and Investment Attraction: LGFs poses a risk to the implementation of climate

reduce investment risks, thereby enhancing the transition projects. Changes in environmental

appeal of projects, especially in regions burdened policies, zoning laws, or carbon pricing mechanisms

by high borrowing costs and significant debt. They can introduce compliance challenges or necessitate

serve as a critical tool for scaling climate finance, project redesigns.

particularly for innovative and impactful projects.

• Contract Standardization and Mobilization: The

development of standardized contracts and criteria POLICY AND MARKET

for LGFs can significantly mobilize financing, ENGAGEMENT

broadening the investor base by reducing perceived

risks. • Policy Reforms to Incentivize Investments: Assessing

the viability of policy reforms that incentivize

• Public and Private Sector Roles: LGFs de-risk investments into LGFs is essential for catalyzing a

investments and attract capital across diverse shift in capital flow towards sustainable development

geographical and political landscapes. This dual- projects. Engaging with policymakers to identify

sector approach underscores the versatility and conducive regulatory environments can amplify the

necessity of LGFs in stimulating green innovation impact and size of the climate finance market.

and supporting small and medium enterprises.

• Stakeholder Collaboration for Market Alignment:

Undertaking collaborative research and engaging

with market stakeholders are pivotal in aligning LGFs

with desired market conditions. Circulating draft

term sheets and due diligence criteria for feedback

ensures that LGFs remain adaptable to emerging

technologies, market trends, and profitability

preferences.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

20 INTRODUCTION TO PLACE-BASED PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION FOR GHG EMISSION REDUCTIONS

03

PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS:

Scorecards

and Integrated

Frameworks

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

21 PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS: SCORECARDS AND INTEGRATED FRAMEWORKS

This section details the design and consolidation of influence, economic policies, and political stability.

integrated frameworks, incorporating the highest Community dynamics, including workforce

scored aspects from the review of decarbonization demographics and inter-community relations, offer

frameworks. These three components are practical and insights into potential for change or areas of resistance.

strategic tools for implementing Place-based Transition Indicators like educational attainment and economic

Funds: conditions can predict political stability and economic

vitality. Effective governance, community support, and

• Geographic Scorecard: Prioritizing geographic proactive engagement emerge as crucial elements for

regions and jurisdictional scales project success.

• Portfolio Design: Translating climate and community

Leveraging data from international entities and

uplift strategies into portfolio construction

experiences, we’ve developed a set of metrics for

• Project Scorecard: Evaluating projects to align with the Geographic Scorecard. This tool aids in efficiently

portfolio structure evaluating and scoring potential areas, encompassing

aspects from governance to environmental

conservation.

GEOGRAPHIC SCORECARD The Scorecard’s detailed approach ensures a

Creating Place-based Transition Fund portfolios nuanced assessment, optimizing the selection for

begins with selecting the right location, a process impactful and sustainable climate interventions.

streamlined using a Geographic Scorecard (Table 4). See Appendix A1 for scorecard metrics and rubric for

Geographical selection should be informed by the Geographical scorecard.

stability of its economy, its regulatory policies, the

enforcement for a rules based governing system,

local need and willingness, and the product to

market fit (i.e. relevance of intervention within a

specific geography). Geographical selection should

encapsulate multifunctionalities, which includes land

use, impacts on the environment, and opportunities to

synergize with natural capital. Geographic analyses can

be categorized into different scales, each with strategic

significance for intervention within the Place-based

Transition Fund:

• National Government (Political): Establishes the

broader policy and funding framework facilitating

local initiatives across diverse bioregions.

• Bioregion (Nature): Represents extensive

environmental patterns with shared characteristics

like carbon sequestration, sustainable resource

extraction, and biodiversity.

• Regional Government (Political): Acts as a key

intermediary, localizing national policies to specific

contexts.

• Ecoregions (Nature): Smaller than bioregions, they

are essential for local ecological management and

conservation strategies, influencing urban planning and

natural resource opportunities.

• City Governments (Political): Directly implement climate

projects and manage stakeholder engagement.

• Local Community (Social): The foundation of our

interventions, reflecting the lived experiences and needs

of the populace, and fostering equitable practices.

Early selection in a project’s life cycle sets the

stage for governmental policy adherence and civic

rights, influenced by factors like governmental

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

22 PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS: SCORECARDS AND INTEGRATED FRAMEWORKS

Table Geographic Scorecard to select for effective deployment of Place-based Transition Funds. This scorecard

4 integrates various factors, such as political boundaries, natural systems, and social dynamics, employing a

multi-scale analysis to harmonize global objectives with local realities.

Evaluation Topic Evaluation Description

Governance

Several indicators are predictive of government effectiveness and within national and subnational

boundaries.

Political Stability Measures the perceptions of the likelihood of political instability, and politically

motivated violence, including terrorism.

Rule of Law Estimates the functioning and independence of the judiciary, including the police,

the protection of property rights, the quality of contract enforcement, as well as

the likelihood of crime and violence.

Government Effectiveness Assesses the quality of policy formulation and implementation, the credibility

of the government’s commitment to its stated policies, the government’s

independence from political pressures, and its services.

Regulatory Quality Evaluates the ability of the government to formulate and implement policies and

regulations that permit and promote private sector development.

Anti-corruption Captures perceptions to which public power is exercised for private gain, including

both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as state capture by powerful

private interests.

Information Flows Assess how governments can restrict or facilitate information flows within or

across borders and government’s impact on transparency between institutions,

media, and individuals.

Economic

Key measures for investors involve monitoring key economic indicators and understanding actions in

communities that are proxies for government trust, effectiveness and willingness.

Fiscal Policy This indicator measures the government’s commitment to prudent fiscal

management and private sector growth.

Inflation Rate The rate of inflation is a key indicator of currency stability.

Foreign Exchange Risk An indicator of trade flow and dynamics.

Investment Grade Ratings An indicator of the likelihood of repayment in accordance with the terms of the

issuance.

Access to Credit This indicator measures the level of financial inclusion in a country.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

23 PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS: SCORECARDS AND INTEGRATED FRAMEWORKS

Informal Economies A measure of informal economies and can be used as a proxy for trust in

government.

Electricity Consumption Indicator of economic activity, formal and informal, and government effectiveness.

Financial Inclusion A measure of economic inclusion and equality.

Labor Force Strength A measure for estimating economic strength compared to the black market and is

also a proxy for trust in government.

Unemployment Rate A lagging indicator for an economy’s health.

Population Growth An indicator of potential economic growth or burden, depending on the size of the

economy.

Social Uplift

Systemic transformations involve improving the quality of life of people within communities.

Identifying where uplift is most needed is essential.

Immunization Rates This indicator measures a government’s commitment to providing essential public

health services and reducing child mortality.

Education Expenditures This indicator is used to gauge the extent to which governments are currently

making investments in the education of their citizens.

Child Health An indicator that measures child health by combining metrics for child mortality,

access to clean water, and access to clean sanitation.

Girls’ Primary Education An indicator for equality, freedom, female safety, and increasingly, an overall

Completion Rate indicator of safety in a community.

Access to Land Measuring to what extent governments are investing in secure land tenure and

property rights reflects equity, particularly amongst the poor, social mobility and

the strength of the social safety net.

Nature

The value of healthy ecosystems, cultural heritage, and the stewardship of these natural and

intangible assets lies in the protection of forests, rivers, oceans and soils.

Natural Resource An assessment of a government’s commitment to preserving biodiversity and

Protection natural habitats, responsibly managing ecosystems and fisheries, and engaging in

sustainable agriculture.

Key Biodiversity Areas This indicator considers critical biodiversity hotspots.

Cultural Heritage This indicator captures the intangible cultural heritage in areas recognized for their

natural and cultural significance.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

24 PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS: SCORECARDS AND INTEGRATED FRAMEWORKS

PORTFOLIO DESIGN

This section discusses designing a portfolio that The integrated framework roadmap adopts a three-

integrates into a selected geographies’ existing or phase approach to portfolio design: Analyze, Act, and

emerging climate action strategies (Figure 3). Accelerate. It draws on ICLEI’s GreenClimateCities

framework and incorporates modular components

The first step is to understand the existing climate that a jurisdiction can take in their climate action

action landscape within the chosen geography. If roadmap for both mitigation and adaptation (e.g.

there’s an existing climate action strategy, it’s important GHG inventories, Climate Change Risk Assessments,

to document its components such as mitigation and Decarbonisation Plans). These modules can be

adaptation strategies, policy commitments, and data adjusted to the specific geographies, but the template

management. This includes noting which parts have can be used as a diagnostic of how far has the selected

been completed, the last update date, and the data geography progressed in the climate action roadmap.

sources used. This diagnosis helps determine if any

further strategies need to be developed or updated,

and tailor the portfolio to enhance these existing

plans. Conversely, if a climate action plan is absent,

a roadmap is developed to align and accelerate the

jurisdiction’s climate goals.

Modular Climate Acton Roadmap for Subnational Jurisdictions

This initial phase is about understanding Here, targeted strategies for climate This initial phase is about understanding

the current climate scenario, setting mitigation and adaptation are developed the current climate scenario, setting

baselines, and committing to climate and implemented by the local baselines, and committing to climate

action. It involves data collection on GHG government. It's about putting plans into action. It involves data collection on GHG

emissions, energy usage, and assessing action, often pilots, and monitoring their emissions, energy usage, and assessing

climate risks. progress, leveraging digital tools to climate risks.

enhance efficiency and transparency.

Figure Modular Climate Action Roadmap for Subnational Jurisdictions. The diagram shows how an integrated

3 framework uses ICLEI’s GreenClimateCities stages, to assess a particular jurisdiction’s climate action progress,

and provides key action modules that if not completed can be undertaken. The development of a Place-based

Transition Fund aligned with the jurisdiction would likely occur mostly in the Act and Accelerate stages.

PLACE-BASED TRANSITION FUNDS

25 PLAYBOOK COMPONENTS: SCORECARDS AND INTEGRATED FRAMEWORKS

From the climate action roadmap, three critical

3

3. Community Uplift Plan

elements for portfolio construction are distilled:

the Decarbonization Plan, a Climate Change Risk Is designed to address socio-economic

Assessments (CCRAs), and Community Uplift Plan challenges in underserved communities through

(Figure 4). The selected geography may not have all targeted interventions and projects. The main

these plans or may incorporate aspects of them under components of the plan typically include: Needs

a different name or strategy. The plans suggested here Assessment and Community Engagement,

should be seen as guiding elements that are ideally Economic Development and Empowerment,

covered in a regional plan and analysis, rather than Equity and Social Inclusion, Education and Youth

serve as prescriptive requirements. These elements Engagement, Health and Wellbeing, Housing and

provide a clear direction for intervention sectors, Infrastructure, and Partnerships and Collaborative

forming the backbone of our portfolio structure. Governance. The key success factor is the active

engagement of the community in the planning

and decision-making process, ensuring that the

1

1. Decarbonization Plans initiatives reflect their needs and aspirations.

Identify emission reduction interventions across

key sectors, using methodologies like the ‘Global Our portfolio structure is segmented into categories

Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas reflecting insights gathered from the local version

Inventory’ (GPC), laying the foundation for selecting of these strategic plans such as “Decarbonization

portfolio projects that align with sector priorities Sectors (e.g. from GPC or IPCC), Nature-based

(Stationary Energy, Transport, Waste, Industrial Projects, Adaptation and Resilience, and Social

Products and Product Use, and Agriculture, Forestry Uplift (Figure 4). The intervention sectors may have

and Land Use (AFOLU) — which can be extended different levels of priorities and number or size of

into a broader nature and biodiversity management projects that should fall under them to achieve the

context. set goals. This should also be determined from the

integrated climate action plans. These insights can

2

2. Climate Change Risk Assessments be used to determine how much of the portfolio

should be allocated to project finance, Small and

Analyze the geography, its assets, infrastructure, Medium Enterprises (SME), and venture investments

and the different future climate scenarios, (although ideally the majority of investments are

evaluating exposure to key risks, such as draughts, projects). Potential synergies across sectors and

fires, heat waves, and flooding. This creates a clear projects that could address several interventions

understanding of areas requiring intervention are identified by forming a Systems Map. When

within the city or region that can be developed these aspects of the portfolio structure are defined,

within a Place-based Transition Fund. the next crucial step involves aligning the portfolio

sectors with the project scorecards.

STRATEGY PLANS INTERVENTION SYSTEMS MAP PORTFOLIO STRUCTURE

SECTORS

Sectoral

1 Decarbonisation Plan

Climate Change