Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dallapiccola WordsMusicNineteenthCentury 1966

Dallapiccola WordsMusicNineteenthCentury 1966

Uploaded by

serboiu.maria.selenaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dallapiccola WordsMusicNineteenthCentury 1966

Dallapiccola WordsMusicNineteenthCentury 1966

Uploaded by

serboiu.maria.selenaCopyright:

Available Formats

Words and Music in Nineteenth-Century Italian Opera

Author(s): Luigi Dallapiccola

Source: Perspectives of New Music , Autumn - Winter, 1966, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Autumn -

Winter, 1966), pp. 121-133

Published by: Perspectives of New Music

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/832391

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Perspectives of New Music

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

/(6-L(0

WORDS AND MUSIC

IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN OPERA

LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA

ABOUT THIRTY years ago, when I was asked by E

whether I knew any Italian treatise describing the princip

sition of arias in Italian opera, I had to answer in the

however, I believe that there existed at least a traditio

arias, one perpetuated orally and by example.

I should like to consider here what the poetic quatrai

composer of the Italian melodrama as a basis for the

operatic forms, with specific reference to arias, ariosi, an

In La Traviata, in the scene where Alfredo reveals his

posed betrayal by Violetta, these lines occur:

Ogni suo aver tal femmina

Per amor mio sperdea:

Io cieco, vile, misero,

Tutto accettar potea.

The range of the voice in the first line is a major sixth an

major seventh. In the music, no significant metrical diffe

the two lines are evident; in the second, however, the me

tendency to move upwards. It is in the third line that th

clearly implied, and an emotional crescendo is brough

discontinuous and agitated declamation that is matched by

accompaniment. The fourth line is accompanied by a d

ment (one entirely independent of the actual musica

Ex. 1)

At this point it might be interesting to see how Verdi solved his compo-

sitional problem when the librettist expanded a quatrain by two lines. This

happens, for example, in the Quartet in Rigoletto. The Duke starts:

Bella figlia dell'amore,

Schiavo son de' vezzi tuoi,

Con un detto sol tu puoi

Le mie pene consolar.

* 121.

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC

The music of this quatrain is almost precisely in a

formal scheme described above: there is no melodic difference between the

first and second lines, in both of which the melodic range is a major sixth;

a climax is reached in the third line, where the voice spans an octave, and

a diminuendo follows in the fourth line.

La Traviata (Finale secondo)

Allegro sostenuto

Alfredo - -,[r? -.I40. 1.

0 - gni suo aver tal fern - - - mi-na

per a - mor mio sper - de - - - a: Io cie-co, vi-le,

mi - - - se-ro, tut - - to ac-cet-tr po-te - -

7x

Ex. 1

Verdi also sets the two lines that the librettist has added:

Vieni e senti del mio core

II frequente palpitar,

but for the sake of the musical structure he makes his own emendation by

repeating the third and fourth lines of the stanza, so that the original six

lines have grown to eight. And although Verdi holds to the traditiona

scheme in the initial quatrain, he now feels compelled, with eight lines at

his disposal, to regard lines five and six as the climax of the two quatrains

. 122 *

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

COLLOQUY AND REVIEW

or, in other words, to treat the entire passage as a quatrain of

pairs. Indeed, while the voice in the crescendo of the first quatra

the high Ab, it goes to high Bb in the over-all climax, and the di

is accomplished with the repetition of the third and fourth lines

original quatrain.

S a, . I Lb-A

Al Bel-la fi-gliadel-l'a - mo -

co- i Bonun detto;un det-to sol tu

- lar. CVieni e sen ti delmio co - re il fre-quen -te pal- pi-

4P J^ -1 r IN, -rYI it

- tar o- - -D I on un detto,un.det-to sol tu p

pe-ne, le mie pe-ne con-so - lar.

Ex. 2

In Leonora's cavatina in Act I of II Trovatore, the text consists

ten-line stanzas. There is a structural innovation here: lines five and six

form a kind of insertion. The big emotional crescendo occurs in the pe-

nultimate line, and the diminuendo in the last.

i " ' Y F r i !

quando so-

? =,. I , I F --.a -- -

i- 48,

Ex. 3

The same ten-line construction, including the inserted fifth and

lines, is to be found in the aria "D'amor sull'ali rosee," in the last a

the same opera.

123

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC

I should like to reemphasize that the emotional cres

found in the third line (in a four-line stanza) or in the t

(in an eight-line stanza). It is almost too well known t

many changes in the original text of Italian operas lie

singers. Even though I am, in principle, against modi

underline a case where the modification is quite preferab

text.

In Manrico's aria "Ah si, ben mio, coll'essere" (II Trovatore: third act),

the last quatrain is repeated two times; in the printed score there is only

one change: in section A. Although the first time the highest note is Db,

the second time the climax is reached at Eb. And because of that there is

no doubt that Bb (instead of Ab) in section C is perfectly, indeed, in-

finitely more beautiful than in the original version. Unfortunately I was

not able to learn when this modification became a part of performance

practice. It is certain, in any case, that it underlines once again the im-

portance of the third section, the real keystone in the construction of the

aria in Italian opera. The performer, on his part, cannot establish the prin-

cipal tempo of the aria without taking this third section into account (Ex.

4).

The emotional crescendo is created through rhythmic animation,

through harmonic surprise, or through the upward movement of the vocal

line. Frequently, of course, the final result is achieved through the col-

laboration of two or three such elements; only rarely does a fourth, such as

a striking instrumental idea, take part. I shall return to this point later,

with reference to a passage in Otello.

Especially interesting treatment of the climax is found in "0 qual soave

brivido" in Un Ballo in Maschera: the beginning of the third pair of lines

is underlined by a fermata. In this case there is also a coda, but one which,

based entirely on word repetition, is completely independent of the poetic-

musical form of the quatrain.

Although the quotations so far have been from operas by Verdi, the

formal scheme I have described is to be found also in Rossini, Donizetti,

and Bellini. In Mathilde's aria ("Selva opaca") in the second act of

William Tell, for example, the climax is effected by harmonic means. And

the classic example of Italian melody, "Casta Diva" from Bellini's Norma,

completely confirms the same principle. Here, with regard to duration,

the first line contains sixteen times the unit of three eighth-notes, and the

second fifteen (including the rests, of course). The third line contains no

less than twenty-two times the same unit--and the concluding line, "senza

nubi, senza vel," only four!

Nor does Verdi abandon this traditional scheme in the works of his last

period. In evidence I adduce a single example from the first act of Otello.

The climax of the so-called "tempest scene" (where chorus and orchestra

are marked ff, tutta forza) sets the following lines:

S124

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Manrico _ _ - dim

Ia IVOF M wig II) i l . i1

Fra que - glie-stre

A B C

C-r

CR.

Execution : .6

o - loJn ciel p

I

---

Fra qL-e- t ev

Fta que -glive-stre-miva- ne - li-ti a te.Jl pen-ster ve - rl, ver-rl, e so - lo. ctel p

Ex. 4

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC

Dio, fulgor della bufera! Dio, sorriso della duna,

Salva l'arca e la bandiera della veneta fortuna!

Tu, che reggi gli astri e il Fato! Tu che imperi al mondo e al ciel,

Fa che in fondo al mar placato posi l'ancora fedel.

Here we find a greater formal variety than in the previously quoted ex-

amples. Nevertheless, one can still recognize the emotional crescendo in

the third of the quoted lines ("Tu, che reggi," etc.). It is produced after an

initial mf, by harmonic means and by two unexpected cymbal crashes on

weak beats, marked soli (i.e., "with solistic function"; see p. 26 of the full

score).

Further evidence of Verdi's intentions can sometimes be gathered by a

comparison of initial sketches with final versions. The first rough version

of "La donna e mobile" is such a sketch, obviously written in haste. In the

final version (known to us from a complete manuscript), the music for

the first and second lines corresponds with that of the first scribbled

notation. The music for the third line, however, is completely different in

the two cases; in the early version it deviates from the formal scheme. It

lacks all rhythmic excitement, there are no possibilities of harmonic sur-

prise, and its vocal line, instead of pushing upward, descends.

8F

a) b) C)

I I ' c

Ex. 5

Regardless of whether there existed a literary tradition that, consc

or unconsciously, determined the aria-form in Italian melodrama, the

certainly an immense number of closed quatrains in poetry (i.e., quat

ending with a full stop) -an immense number of rhymed quatr

Italian and French, from Dante to Baudelaire-in which the secon

merely continues the first, increasing the emotional level but litt

climax appears in the third line; and in the last, the conclusion b

diminishing intensity.

This analogy certainly deserves consideration. From numerous exam

I shall choose only a few. From Dante:

Tanto gentile e tanto onesta pare

La donna mia quand'ella altrui saluta,

Che ogne lingua deven tremando muta,

E gli occhi non Pardiscon di guardare.

In the following example, from Petrarca, notice the last word

third line: salita (participle of the verb salire-to ascend, to rise) a

denoting ascent.

126

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

COLLOQUY AND REVIEW

La bella donna che cotanto amavi

Subitamente s'6 da noi partita,

E, per quel ch'io ne speri, al ciel salita;

Si furon gli atti suoi dolci e soavi.

From Victor Hugo:

Ruth songeait et Booz dormait: l'herbe etait noire;

Les grelots des troupeaux palpitaient vaguement;

Une immense bonte tombait du firmament;

C'etait l'heure tranquille oh les lions vont boire.

Here, the descent implied by the verb tomber (to fall down) is canceled by

the adjective immense and by the noun firmament.

Finally, in Baudelaire:

C'est la mort qui console, helas!, et qui fait vivre;

C'est le but de la vie et c'est le seul espoir

Qui, comme un elixir, nous monte et nous enivre,

Et nous donne le coeur de marcher jusqu'au soir.

Notice in the third line two verbs suggesting ascent: monter (to climb

to rise) and enivrer (to enrapture) -not to speak of the noun elixir.

On the other hand, could not the melodrama-the best kind of popula

theatre-have developed, gradually and unknown to its creators, from

primitive art form of similar type? The section of the thirteenth-century

mystery play, The Play of Daniel, in which the hero explains to the King

the significance of Mane, Thechel, Phares, cannot fail to strike the hearer

by its structural resemblance to an aria in a melodrama.

Daniele I.E O p=T= Ip, , ad

Et MA -NE di - cit Do - mi -nus, Est tu - i re - gni ter -

A B

A' . 1 i/ I I-

-CKEL li- bran si - - gni - fi - cat Quae te mi-no- rem in - di -cat. PHA -

C

- REs. nec est diI -I -

I vi

(segue)

- si - o, Re

iQui sic sol-vit la --ten-ti - a Or --ne - tur ve-ste re- gi - a.

D

Ex. 6

Now, it is by no means the case that the principle of the e

climax as the penultimate section of a musical quatrain belongs e

. 127 ?

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC

to the aria in Italian opera. The same principle is at w

as well, although it functions in a different way. The fir

to mind is that of Schubert--especially Schubert in his

rather than the composer of Nacht und Triiume, which

differently. (I might note here that Alban Berg emp

mental" character of the voice in Schubert's Lieder.) Bee

be mentioned in this connection. One of the most thoro

of his use of these principles is the theme of the rondo

90. Indeed, according to Schindler, Beethoven called

versations with the Beloved." It is a dramatic scene, the

Busoni relates that an intelligent music critic, just

conceived the idea of adding words to the first viol

string quartet, and that he gave the part to a soprano t

us that, upon going into the room where the experimen

he had the clear impression "of being in the middle of

Mozart opera."

What is the origin, then, of the characteristics we

culiar to the Italian melodrama? They stem, it seem

fact that the Italian opera composers of the nineteenth

all tradition relating to purely instrumental music.

conceived the emotional crescendo in the third section of the musical

quatrain almost as the result of theatrical necessities-as a theatrical

gesture.

In evidence I adduce two examples that are almost identical in melody,

yet totally different in effect: on the one hand, a passage from Mozart's

Violin Concerto in A major; on the other, a passage from Lucia di Lam-

mermoor. In the first case, the third and fourth sections develop according

to the logic and rules of purely instrumental style; in the second, the de-

velopment of these sections obeys the demands of the stage. (See Ex. 7.)

So far, I have restricted my discussion to the structure of the aria in the

melodrama as a musical quatrain, and to the analogy between quatrains in

music and poetry. Now I should like to broaden my field and explain how

Verdi applied the same principle of organization to a large form, such as

the trio in Act II of Un Ballo in Maschera.

Let us first look at the libretto. Each singer presents a stanza of eight

lines (or rather of four couplets). In both the original and the modern

editions of the libretto, which doubtless follow the original manuscript, the

characters appear in the following order: Amelia, soprano; Riccardo, tenor;

Renato, baritone. It is rather startling to note that Verdi, in setting this

trio to music, changed the succession of male voices as fixed by the libret-

tist: he transferred the entrance of the baritone from third to second place,

and that of the tenor from second to third. This observation should help

us to realize the extraordinary clarity of purpose with which Verdi set to

work: Riccardo, the tenor, is now entrusted with the climax of the trio,

while to the three stanzas of the librettist are added a fourth and a fifth-as

S128

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

COLLOQUY AND REVIEW

Mozart

#*ILMN FF i 1 F

A u -.4.a Ml,,, =

IIBI

A A

j I I \ r -

Co-me ro- - sa i na -ri - di - - -ta, Es sa

A tI

sta fra mor tee vi - - - ta, Io son

{Ii7rI DH! -

vin . to son

1 1 F2

gra --ta, t'a - mo, ta-mom -grata, t'a moan - or

-gra - - ta, t'a - mo, t'a- mo in - gra- ta, t'a - - - mo an - cort.

Ex. 7

a musical reprise and coda, respectively. In the reprise each singer par

pates in such a way as to repeat the words assigned him before: the so

and the baritone repeat all of the words; the tenor, only a few. Verdi

his exceptionally acute feeling for stage effect, could not fail to see tha

feeling of guilt (almost a guilt complex!) expressed by the tenor

represented the true climax of the piece.

This trio has been called "beautiful" and "magnificent." Many p

are satisfied with such characterizations. The trio will remain "beautiful"

and "magnificent" even after my attempt at structural analysis, for analysis

can take nothing away from the esthetically perfect nor, on the other hand,

can it contribute anything to the esthetically imperfect. Viewing such an

achievement as this trio-listening to it, more than a hundred years after

its appearance, with modern ears (the only ones I consider valid), and

reading it with modern eyes (again the only valid ones) -we shall become

aware of various points heretofore overlooked. Consequently, I will not

hesitate to speak of macrostructure and microstructure, although such

terms have originated only in recent years and have been employed chiefly

0 129 ?

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC

in the analysis of contemporary music. I should li

famous phrase of the doctor angelicus, St. Thoma

ments of beauty: "Ad pulchritudinem tria requiruntu

nantia, claritas." Thus: integrity, or unity of the wh

or equilibrium of the parts; clarity, or expression of s

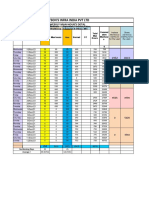

Let us now proceed to the examination of the ma

design. (See the chart on the following page.) In

of the microstructures a, b, c, d, corresponds to fou

the fifth corresponds to the eight measures of the c

the same length will be found at the end of the secon

stanzas. One should not forget, in this connection,

mentioned above, the codettas and the coda are n

libretto. They are of purely musical significance--the

words previously sung.)

Amelia: Odi tu come fremono cupi

Per quest'aura gli accenti di morte?

The voice range is D-A (with Bb di volta). The sam

the second microstructure:

Di lassil, da quei negri dirupi

Il segnal de' nemici parti.

Here the melodic line begins to swing upward: in place of the fifth D-A,

we have the fifth F-C. The third microstructure:

Ne' lor petti scintillano d'ira

E gia piomban t'accerchiano fitti

represents, as always, the apex of the first stanza. Three elements con-

tribute to this effect: the extension of the vocal range to the high F; a

dynamic crescendo followed by a decrescendo; and, as if this were not

enough, surprising accents on weak beats in two horns, violas, and cellos.

Microstructure d:

Al tuo capo gia volser la mira,

Per pieta, va, t'invola di qui

represents the conclusion of the quatrain-couplet and, compared with the

previous section, an emotional diminuendo. Amelia's high A should not

deceive us: it is basically a resolution which does not weaken in the least

the effect of the high F, the vocal climax of microstructure c. One might

even consider this high A as completely independent of the three subse-

quent A's that are repeated almost like cries of anguish (in the codetta).

(The vocal score, even in the first edition, which must be assumed to be

based on the original manuscript, shows no accent on the first A. But the

three subsequent A's and their parallels in the following stanzas are given

accents.)

S130

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A Climax of the piec

Son colui che nel cor lo fere. d) Innocente, sfidati li avr

Or d'amore

Ah, I'amico tradito ho pur io... c)easu 561)

Che minacciano il vivere m

Traditor, congiurati

(N.B. In the son essi

orchestra La pieta)

score it Posa

reads sciagurati, not congiuratil) d,

delialetd

Signo

b)/

Va, ti salva, del popolo b vita

d) a)

d)(Baritone

Questa vita chesolo)

getti cosi C) C c) Sopran

Codetta Co

Climax of A and B ) Va, i salva, o che varco all'uscia b) Sop

(Baritone and Soprano a 2) Qui tra poco serrarsi vedra..

c*o

b)Allo scambio del detti esecrati

Ogni destra la daga brandA

a) Fuggi, fuggi, per l'orrida via c) d)

Sento l'orma dei passi spietati: Co

d) Al piett,

Per tuo capo git'invola

va, .volser la

di mira.,. b)

qui. Codetta

Climax of the first stanza. The a)

voice arrives at the high F:" dy-

namic crescendo followedbya de-

crescendo: accents on the weak

beat assigned totwolHorns, to the

Violas, and to the Violoncellos.

) Nei lor petti scintillano d'ira,

E giA piomban, t'accerchiano fitti...

b) I1 segnal dei nemici partI.

Di lassi, da quel negri dirupi -

) Odi tu come fremono cupi

Per quest'aura gli accenti di morte?

Chart 1

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC

The second stanza is given to Renato, the bariton

identical to the first: the variant in the two final lines

to the necessity of arriving at the dominant at the

Nevertheless, in spite of this similarity, it should

soprano adds her own part, an octave above the bariton

sixth lines, i.e., in microstructure c. The resultant mus

is sufficient to yield a higher degree of intensity-a

emotional crescendo. (The soprano again joins the b

give greater force and luster to the words "Va, va, va"

The third stanza brings us to the climax of the entire

Traditor, congiurati son essi

Che minacciano il vivere mio?

Ah, l'amico ho tradito pur io....

Son colui che nel cuor lo feri.

Each of the microstructures a, b, c, d, corresponds here to two measures.

In contrast to the previous stanzas, where each pair of lines is linked

through the musical setting, here each individual line is marked off by

an eighth-rest. Here, then, is one element that contributes toward the

triple emotional crescendo within this section. Two more will be added.

Since the first three lines are based on A, C, and E, respectively, while the

fourth begins on F, the necessary upward swing is strictly observed.

Furthermore, the conclusions of the first three are emphasized through

highly expressive insertions ("Ah, fuggi-Ti salva-Va, fuggi") derived

from the end of the climax (microstructure c) of the first stanza.

Now, without even a rest, the tenor continues with lines five and six,

which constitute the climax of the third stanza and also of the entire trio.

After reaching the high A on the first syllable (In-nocente), the vocal

line gradually descends. This also marks the beginning of the emotional

diminuendo, both of the macrostructure and of the microstructures. (It is

the only passage in the piece that Verdi has marked poco allargando,

col canto.)

Let me now count the measures of the stanzas, in order to clarify their

proportional relations. The first comprises 24 measures; the second, 24;

the third, for dramatic reasons the briefest, 16 (there is no codetta); the

fourth, 24; and the coda, 23. On the last chord of the coda there is a

fermata; and, as we know, in Verdi's time it was customary to double

the note values to which this sign applied. Thus we can properly assign

24 measures to the coda as well. All told, then, there are 112 measures.

The tenor's line "Innocente, sfidati li avrei," the climax of the third stanza

and of the whole piece, begins exactly with m. 56 and thus stands in the

center of the entire trio. To me this seems extraordinary, the more so

since Verdi could hardly have planned such a miracle of proportions; he

must have conceived and carried it out intuitively.

S132

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

COLLOQUY AND REVIEW

We are now approaching the conclusion of the trio. The fou

is musically identical with the first. But the first eight measure

reprise (corresponding to the first four lines of the stanza)

two voices (soprano and baritone) rather than for a single voice

and in lines five and six (climax: microstructure c) the tenor als

Thus three voices appear in the fourth stanza, corresponding

voices in the parallel passage in the second.

The concluding section of the piece consists of the 23 (+ 1)

of the coda-that is, of the sum of the measures of the three

the first, second, and fourth stanzas. This coda is a mere conclus

in character, rather ordinary. The word ordinary is not meant i

tory sense: I am simply trying to explain a dialectic and stylistic

characterizing a whole period. To deny this would be just as

to call the 29 measures of C major at the end of Beethoven's

phony "too long," or the ottava rima of Ariosto's Orlando Furios

nous," or the proportions of the Wagnerian opera "exaggerated."

Listen now, if you can, to the entire scene of which this t

culmination. Un Ballo in Maschera is the last opera that Ve

melodramma. In this scene one can find, in condensed form, ma

conventional elements of the form. But the composer's genius, t

of the dramatic accent," according to Busoni's beautiful chara

has surmounted the incredible situation, the absurd languag

syntax, the pathos of the formalistic style of the Italian melodr

S133

This content downloaded from

83.103.212.204 on Tue, 05 Mar 2024 09:19:23 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Folia Melodies - R.HudsonDocument23 pagesThe Folia Melodies - R.HudsonFrancisco Berény Domingues100% (1)

- Wozzeck Lecture by Alban BergDocument13 pagesWozzeck Lecture by Alban Bergdayel66100% (1)

- HotteterreDocument9 pagesHotteterreCarla AbalosNo ratings yet

- Traditional Harmony: Book 2: Exercises for Advanced StudentsFrom EverandTraditional Harmony: Book 2: Exercises for Advanced StudentsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Dallapiccola Words and Music PDFDocument14 pagesDallapiccola Words and Music PDFOrquestaSanJuanNo ratings yet

- Ravel Analysed by Messiaen Trans GriffithsDocument54 pagesRavel Analysed by Messiaen Trans GriffithsKenneth Li100% (18)

- Ives Charles Schoffman Nachum Serialism in The Work ofDocument13 pagesIves Charles Schoffman Nachum Serialism in The Work ofEsteban De Boeck100% (1)

- The Problem of SatieDocument9 pagesThe Problem of SatieDaniel PerezNo ratings yet

- Rondo Colé NW 2001Document14 pagesRondo Colé NW 2001PAULA MOLINA GONZÁLEZNo ratings yet

- Aconcise History of Music William Lovelock - Removed - Removed - RemovedDocument196 pagesAconcise History of Music William Lovelock - Removed - Removed - RemovedVithiyaslvNo ratings yet

- Solomon Beethoven 9Document22 pagesSolomon Beethoven 9JayYangyNo ratings yet

- Music 9 Module EditedDocument8 pagesMusic 9 Module EditedLyrine Ann RosarioNo ratings yet

- Verdi's Operatic Choruses Author(s) : Johannes Brockt Source: Music & Letters, Jul., 1939, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Jul., 1939), Pp. 309-312 Published By: Oxford University PressDocument5 pagesVerdi's Operatic Choruses Author(s) : Johannes Brockt Source: Music & Letters, Jul., 1939, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Jul., 1939), Pp. 309-312 Published By: Oxford University PressCleiton XavierNo ratings yet

- Tim Carter - Possente Spirto On Taming The Power of MusicDocument8 pagesTim Carter - Possente Spirto On Taming The Power of MusicFelipeNo ratings yet

- Dies Irae Letter 2Document11 pagesDies Irae Letter 2Max JacobsonNo ratings yet

- Kyrie Trent Codex 90Document4 pagesKyrie Trent Codex 90Jeff Ostrowski100% (1)

- Encounters With The Chromatic Fourth... Or, More On Figurenlehre, 2Document5 pagesEncounters With The Chromatic Fourth... Or, More On Figurenlehre, 2sercast99No ratings yet

- Lewent DanceSongChant 1960Document10 pagesLewent DanceSongChant 1960Francesco SmeshNo ratings yet

- Performance Practice and The FalsobordoneDocument24 pagesPerformance Practice and The FalsobordoneEduardo Jahnke Rojas100% (1)

- CirclesDocument3 pagesCirclestomaszryNo ratings yet

- Lowinsky Greitner FortunaDocument25 pagesLowinsky Greitner FortunaJuan Florencio Casas Rodríguez100% (1)

- Forte, The Golden Thread Octatonic Music in Webern's Early Songs (Webern Studies, Ed. Bailey, 74-110)Document19 pagesForte, The Golden Thread Octatonic Music in Webern's Early Songs (Webern Studies, Ed. Bailey, 74-110)Victoria ChangNo ratings yet

- Anthology - Joshua PareDocument4 pagesAnthology - Joshua PareJoshua PareNo ratings yet

- Musica Enchiriadis (Music Handbook) C. 890: Teaches Improvised Polyphony On TheDocument4 pagesMusica Enchiriadis (Music Handbook) C. 890: Teaches Improvised Polyphony On Thehaykalham.piano9588No ratings yet

- Beethoven's 9th Symphony: A Search For Order - Maynard Solomon (1986)Document22 pagesBeethoven's 9th Symphony: A Search For Order - Maynard Solomon (1986)alsebal100% (2)

- (Para Leer) First Attempts at The Dramatic Recitative. Jacopo Peri - Giulio CacciniDocument48 pages(Para Leer) First Attempts at The Dramatic Recitative. Jacopo Peri - Giulio CacciniMaría GSNo ratings yet

- New Directions: Toward The Classic StyleDocument10 pagesNew Directions: Toward The Classic StyleNorman xNo ratings yet

- Gothic Voices - The Spirits of England and France, Vol. 2 PDFDocument25 pagesGothic Voices - The Spirits of England and France, Vol. 2 PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To TempoDocument27 pagesCambridge University Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To TempoPatrick ReedNo ratings yet

- Arnold, Solo Mottett in VeniceDocument14 pagesArnold, Solo Mottett in VeniceEgidio Pozzi100% (1)

- Beechey, G. (1974) - The Organist's Repertory 16 - The Organ Music of Jehan Alain - 2. The Musical Times, 115 (1576), 507-509Document4 pagesBeechey, G. (1974) - The Organist's Repertory 16 - The Organ Music of Jehan Alain - 2. The Musical Times, 115 (1576), 507-509Gabby ChuNo ratings yet

- Verdi's Reform To The Opera PDFDocument28 pagesVerdi's Reform To The Opera PDFmikelferro1No ratings yet

- Ritornello (It. Fr. Ritournelle) : Michael TalbotDocument3 pagesRitornello (It. Fr. Ritournelle) : Michael TalbotTe Wei HuangNo ratings yet

- Berio and His 'Circles'Document3 pagesBerio and His 'Circles'Anderson BeltrãoNo ratings yet

- Monteverdi. L'OrfeoDocument8 pagesMonteverdi. L'OrfeoLuis Mateo AcínNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 82.49.44.75 On Sun, 28 Feb 2021 19:30:39 UTCDocument21 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.49.44.75 On Sun, 28 Feb 2021 19:30:39 UTCPatrizia Mandolino100% (1)

- Musical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical TimesDocument3 pagesMusical Times Publications Ltd. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Musical Timesbotmy banmeNo ratings yet

- Glass, Philip (1978) - 'Notes Einstein On The Beach' in Performing Arts Journal, Winter, 1978, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Winter, 1978), Pp. 63-70Document9 pagesGlass, Philip (1978) - 'Notes Einstein On The Beach' in Performing Arts Journal, Winter, 1978, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Winter, 1978), Pp. 63-70Maxim FielderNo ratings yet

- Dulce Memoire A Study of The Parody ChansonDocument18 pagesDulce Memoire A Study of The Parody ChansonIñigo Aguilar Martínez100% (1)

- Cherubino UnveilingDocument11 pagesCherubino UnveilingRadoslavNo ratings yet

- Jackson, Trabaci InganniDocument6 pagesJackson, Trabaci InganniMaria Teresa100% (1)

- Preface Concerts Royaux - CouperinDocument8 pagesPreface Concerts Royaux - Couperin1rEn3No ratings yet

- Mozart Choice of KeysDocument9 pagesMozart Choice of KeysWeisslenny0No ratings yet

- 1991 Violin Intonation - A Historical SurveyDocument21 pages1991 Violin Intonation - A Historical SurveyT0NYSALINAS100% (1)

- Boris BellsDocument22 pagesBoris BellsMaricel AgostiniNo ratings yet

- Characters, Key Relations and Tonal Structure in 'Il Trovatore'Document12 pagesCharacters, Key Relations and Tonal Structure in 'Il Trovatore'Siyao HeNo ratings yet

- Stras - Recording TarquiniaDocument19 pagesStras - Recording TarquiniaJorgeNo ratings yet

- Chant Manual FR Columba KellyDocument115 pagesChant Manual FR Columba KellyCôro Gregoriano100% (1)

- Jerold Early Music ArticleDocument16 pagesJerold Early Music ArticleJuan Pablo Honorato BrugereNo ratings yet

- The Symphonies of Alexander TcherepninDocument10 pagesThe Symphonies of Alexander TcherepninEduardo StrausserNo ratings yet

- Sonnet FormsDocument9 pagesSonnet FormsSampath JayakodyNo ratings yet

- Formacao de Escalas Na Musica Pos Tonal - KOSTKA SANTADocument25 pagesFormacao de Escalas Na Musica Pos Tonal - KOSTKA SANTAredy_wesNo ratings yet

- Dante FantasiaDocument7 pagesDante FantasiaCarlosNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 147.91.1.43 On Tue, 14 Dec 2021 11:48:31 UTCDocument10 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 147.91.1.43 On Tue, 14 Dec 2021 11:48:31 UTCMatejaNo ratings yet

- Session2-3. Fuhrmann Renaissance of Phrygian ModeDocument9 pagesSession2-3. Fuhrmann Renaissance of Phrygian Modeherman_j_tanNo ratings yet

- Rediscovering Me3ssiaens Inverted ChordsDocument22 pagesRediscovering Me3ssiaens Inverted ChordsNemanja EgerićNo ratings yet

- Famous Musicians With Their Music Analysis: Submitted By: Niel Christian AmosoDocument6 pagesFamous Musicians With Their Music Analysis: Submitted By: Niel Christian AmosoLein LychanNo ratings yet

- William Tell: Overture to the OperaFrom EverandWilliam Tell: Overture to the OperaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Tulcea - Prezentare in EnglezaDocument28 pagesTulcea - Prezentare in EnglezaAndrei AlexandruNo ratings yet

- TempDocument1 pageTempgrwgNo ratings yet

- Dautson'S Infra India PVT LTD: Daily/Weekly Man Hour'S DetalDocument5 pagesDautson'S Infra India PVT LTD: Daily/Weekly Man Hour'S DetalDautsons InfratechNo ratings yet

- Elf Girl - YaBatalovaDocument48 pagesElf Girl - YaBatalovaCarina Ribeiro100% (6)

- I. Steps in Stretching Stretch Your Neck: ExerciseDocument5 pagesI. Steps in Stretching Stretch Your Neck: ExerciseJoy JeonNo ratings yet

- Route 10 Folkestone - AshfordDocument7 pagesRoute 10 Folkestone - AshfordNathan AmaizeNo ratings yet

- Catalog 2011Document16 pagesCatalog 2011AntonioPalloneNo ratings yet

- PreTest MAPEH 7Document18 pagesPreTest MAPEH 7Marjorie SisonNo ratings yet

- The Chess Improver: Supercharge Your Training With Solitaire ChessDocument9 pagesThe Chess Improver: Supercharge Your Training With Solitaire ChesszoozooNo ratings yet

- Amirkhusros BookDocument6 pagesAmirkhusros BookharunansarNo ratings yet

- IoT ProtocolsDocument26 pagesIoT ProtocolsthinkableofficialhandleNo ratings yet

- Catalogo Cressi Mergulho 2009Document110 pagesCatalogo Cressi Mergulho 2009alexpt2000100% (23)

- Colour DetailDocument52 pagesColour DetailRadhika Rajeev100% (2)

- PaintingDocument22 pagesPaintingjose calmaNo ratings yet

- Schedule - G 1Document6 pagesSchedule - G 1A RajaNo ratings yet

- 02DKA20F1002 01 Fundamentally Modelling Architecture-SHAK F1002Document7 pages02DKA20F1002 01 Fundamentally Modelling Architecture-SHAK F1002Hazriesyam Amir MustaphaNo ratings yet

- Agent Management - DataResolve SupportDocument5 pagesAgent Management - DataResolve SupportKrishna RajuNo ratings yet

- Recipe Chilli Beans 2Document4 pagesRecipe Chilli Beans 2Mat UyinNo ratings yet

- Case Diesel 2007 Corrected-WDocument24 pagesCase Diesel 2007 Corrected-WJuan FerrandezNo ratings yet

- Chinese Festivals - Spring FestivalDocument8 pagesChinese Festivals - Spring FestivalpranitaNo ratings yet

- BNW Character ListDocument2 pagesBNW Character Listapi-279810228No ratings yet

- Bentley SELECT Licensing Program EligibilityDocument13 pagesBentley SELECT Licensing Program EligibilitySanjay SibalNo ratings yet

- Grade 2 Reading Comprehension Worksheet The Tidy Drawer: Read The Story BelowDocument2 pagesGrade 2 Reading Comprehension Worksheet The Tidy Drawer: Read The Story Belowmbabit leslieNo ratings yet

- Visa Profile EgyptDocument5 pagesVisa Profile EgyptAhmad HusseinNo ratings yet

- Bird Photography: Keeping It Stable: PhotzyDocument16 pagesBird Photography: Keeping It Stable: PhotzymrpiracyNo ratings yet

- Prusa I3 Achatz Edition Frame Kit ManualDocument34 pagesPrusa I3 Achatz Edition Frame Kit ManualLászló BogárdiNo ratings yet

- Sonic The Hedgehog 2 Chemical Plant ZoneDocument2 pagesSonic The Hedgehog 2 Chemical Plant Zoneブラック★ロックシューター100% (1)

- 05 - The Powers Part 1Document3 pages05 - The Powers Part 1Murat KahramanNo ratings yet

- Afmbe - New GearDocument2 pagesAfmbe - New GearAlessio Bran PetrosinoNo ratings yet

- I1 Grave of The Green Flame 4thDocument48 pagesI1 Grave of The Green Flame 4thJoe Cesario100% (1)