Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cohen ProducingEqualStatusInteraction 1995

Cohen ProducingEqualStatusInteraction 1995

Uploaded by

thaopnguyen2512Copyright:

Available Formats

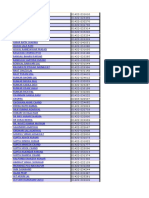

You might also like

- Pyromaniac Press - Faiths of The Forgotten Realms v1.1 PDFDocument201 pagesPyromaniac Press - Faiths of The Forgotten Realms v1.1 PDFGggay100% (3)

- Impact BBDO Creative BriefDocument4 pagesImpact BBDO Creative BriefaejhaeyNo ratings yet

- Angela Davis Are Prisons ObsoleteDocument65 pagesAngela Davis Are Prisons Obsoletefuglicia90% (30)

- Phelan StudentsMultipleWorlds 1991Document28 pagesPhelan StudentsMultipleWorlds 1991asmariaz53No ratings yet

- Cohen RestructuringClassroomConditions 1994Document36 pagesCohen RestructuringClassroomConditions 1994thaopnguyen2512No ratings yet

- Phelan Davidson Cao 1991Document28 pagesPhelan Davidson Cao 1991Andres MartinNo ratings yet

- Carlisle MurraySES Academics EncycloediaArticle PDFDocument8 pagesCarlisle MurraySES Academics EncycloediaArticle PDFApril Jayne T. AlmacinNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Race and Gender Biases and The Moderating Effects of Their Beliefs and DispositionsDocument25 pagesTeachers' Race and Gender Biases and The Moderating Effects of Their Beliefs and DispositionsANIS SAPITRINo ratings yet

- The School CultureDocument14 pagesThe School Culturescribosis100% (3)

- First-Grade Classroom Behavior - Its Short - and Long-Term Consequences For School PerformanceDocument15 pagesFirst-Grade Classroom Behavior - Its Short - and Long-Term Consequences For School PerformanceTugas KuliahNo ratings yet

- An Intervention To Improve Motivation For Homework: ArticleDocument15 pagesAn Intervention To Improve Motivation For Homework: ArticleAlina HâjNo ratings yet

- Educational Measurement - 2021 - Kang - Learning Theory Classroom Assessment and EquityDocument10 pagesEducational Measurement - 2021 - Kang - Learning Theory Classroom Assessment and EquityemilyannewebberNo ratings yet

- The Role of Educational Systems in The Link Between Formative Assessment and MotivationDocument9 pagesThe Role of Educational Systems in The Link Between Formative Assessment and MotivationYawen DengNo ratings yet

- How Will I Get Them To Behave?'': Pre Service Teachers Re Ect On Classroom ManagementDocument14 pagesHow Will I Get Them To Behave?'': Pre Service Teachers Re Ect On Classroom ManagementfatmaNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Trust in Teachers Implications For Behaviour in The High School Classroom-2008Document18 pagesAdolescent Trust in Teachers Implications For Behaviour in The High School Classroom-2008LilyNo ratings yet

- Makinga DifferenceDocument15 pagesMakinga DifferenceJorge Prado CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes in The Classroom and Effects On AchievementDocument45 pagesGender Stereotypes in The Classroom and Effects On AchievementhawwaNo ratings yet

- Power and AgencyDocument35 pagesPower and AgencyFelipe Ignacio A. Sánchez VarelaNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its Setting Rationale of The StudyDocument39 pagesThe Problem and Its Setting Rationale of The StudyGab TangaranNo ratings yet

- Psikopend - Does School Matter For Students' Self-Esteem - Associations of Family SES Peer SES and School Resources With Chinese Students Self-EsteemDocument9 pagesPsikopend - Does School Matter For Students' Self-Esteem - Associations of Family SES Peer SES and School Resources With Chinese Students Self-EsteemMaria SutarjaNo ratings yet

- Modelo de Artículo ApaDocument31 pagesModelo de Artículo ApaHugo González AguilarNo ratings yet

- Systemic Sorting of TeachersDocument21 pagesSystemic Sorting of TeachersChristopher StewartNo ratings yet

- 03 VardaRetrumKuenziDocument28 pages03 VardaRetrumKuenziKarl Benedict OngNo ratings yet

- Setting by Ability - or Is It. A Quantitative Study of Determinants of Set Placement in English Secondary SchoolsDocument18 pagesSetting by Ability - or Is It. A Quantitative Study of Determinants of Set Placement in English Secondary SchoolsAnonymous 09S4yJkNo ratings yet

- Cooksey Et Al-2007-Assessment As Judgment in Context Analysing How Teachers Evaluate Students WritingDocument35 pagesCooksey Et Al-2007-Assessment As Judgment in Context Analysing How Teachers Evaluate Students WritingBahrouniNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Validity of A Teachers' Self-Efficacy Scale in Five CountriesDocument10 pagesExploring The Validity of A Teachers' Self-Efficacy Scale in Five CountriesJay GalangNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Baquero Et Al - The Paradoxes of An Autonomous Student...Document19 pages2015 - Baquero Et Al - The Paradoxes of An Autonomous Student...Amanda RiedemannNo ratings yet

- Teaching Methods at Single Sex High Schools - An Analysis of The IDocument32 pagesTeaching Methods at Single Sex High Schools - An Analysis of The IMokrane Anissa g2No ratings yet

- Alan Ertac Mumcu GenderStereotypesDocument44 pagesAlan Ertac Mumcu GenderStereotypesprimedevilla311No ratings yet

- 12 Stirner G5 PR2Document12 pages12 Stirner G5 PR2ryancarles17No ratings yet

- Telhaj PDFDocument33 pagesTelhaj PDFAlmudena SánchezNo ratings yet

- Student Perception of Shift From Homogenous Grouping To Heterogeneous Grouping at A University ClassDocument7 pagesStudent Perception of Shift From Homogenous Grouping To Heterogeneous Grouping at A University ClassTran Ngo TuNo ratings yet

- Ohio State University Press: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument33 pagesOhio State University Press: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPq1q1q1qNo ratings yet

- Weaver, Lauren - A Case Study of The Implementation of Restorative Justice in A Middle SchoolDocument10 pagesWeaver, Lauren - A Case Study of The Implementation of Restorative Justice in A Middle SchooljuanNo ratings yet

- Rosenholtz 1985 Effective SchoolsDocument38 pagesRosenholtz 1985 Effective Schoolslew zhee piangNo ratings yet

- Classroom Peer Relationships and Behavioral Engagement..Document13 pagesClassroom Peer Relationships and Behavioral Engagement..reniNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Influences and Educational Aspirations in 12 Countries - The Importance of Institutional ContextDocument25 pagesInterpersonal Influences and Educational Aspirations in 12 Countries - The Importance of Institutional Context方科惠No ratings yet

- Jep-Peer Influence in ReadingDocument49 pagesJep-Peer Influence in ReadingJeslee NicolasNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Ying Guo, Laura M. Justice, Brook Sawyer, Virginia TompkinsDocument8 pagesTeaching and Teacher Education: Ying Guo, Laura M. Justice, Brook Sawyer, Virginia TompkinsFrontiersNo ratings yet

- WalkerrDocument24 pagesWalkerrMercedes FerrandoNo ratings yet

- Teacher Education, 13, 541-553.: Catherine D. EnnisDocument14 pagesTeacher Education, 13, 541-553.: Catherine D. Ennisapi-61200414No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1041608014001848 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S1041608014001848 MainDessya ThahaNo ratings yet

- Social Dynamics in The ClassroomDocument11 pagesSocial Dynamics in The ClassroomRaja Jaafar Raja IsmailNo ratings yet

- Mate y BasketDocument38 pagesMate y BasketJAIR ANDRES PALACIOS RENGIFONo ratings yet

- Bogenschneider ParentalInvolvementAdolescent 1997Document17 pagesBogenschneider ParentalInvolvementAdolescent 1997rosulamanchingNo ratings yet

- The differential effects of labelling how do dyslexia and reading difficulties affect teachers beliefs για άρθροDocument16 pagesThe differential effects of labelling how do dyslexia and reading difficulties affect teachers beliefs για άρθροEleni KeniniNo ratings yet

- Teachers MatterDocument5 pagesTeachers MatterDave CawkwellNo ratings yet

- Effect of School Variables On Student Academic Performance in Calabar Municipal Area of Cross River StateDocument27 pagesEffect of School Variables On Student Academic Performance in Calabar Municipal Area of Cross River StateJoshua Bature SamboNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between School Climate and Teacher Self-EfficacyDocument12 pagesThe Relationship Between School Climate and Teacher Self-EfficacyRomeo Jr Vicente RamirezNo ratings yet

- Theo ChangedDocument4 pagesTheo ChangedRican James MontejoNo ratings yet

- Teachers MatterDocument6 pagesTeachers MatterDave CawkwellNo ratings yet

- Stathopoulos Researchreport 1Document7 pagesStathopoulos Researchreport 1api-317916500No ratings yet

- THNG Qualifyingpaper 2017Document83 pagesTHNG Qualifyingpaper 2017moonyeen banaganNo ratings yet

- Lee 2021Document14 pagesLee 2021khanhNo ratings yet

- Creating A Moral AtmosphereDocument28 pagesCreating A Moral AtmosphereHay Day RNo ratings yet

- Sutherland Et Al., 2008 PDFDocument12 pagesSutherland Et Al., 2008 PDFAnnie N100% (1)

- Zum Brunn 2014Document24 pagesZum Brunn 2014Baihaqi Zakaria MuslimNo ratings yet

- Making Visible The Behaviors That Influence LearniDocument28 pagesMaking Visible The Behaviors That Influence LearniMaestria TephyNo ratings yet

- American Sociological AssociationDocument24 pagesAmerican Sociological AssociationHarriet KirklandNo ratings yet

- 2014-Furrer Skinner PitzerDocument24 pages2014-Furrer Skinner PitzerAnis TajuldinNo ratings yet

- Middle Level Students Perceptions of Their Social and Emotional Learning An Exploratory StudyDocument16 pagesMiddle Level Students Perceptions of Their Social and Emotional Learning An Exploratory StudyHelena GregórioNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Class Heterogeneity in Academic Performance of Junior High School Students of MCHL Chapter 1 Research G 3 1 1 1Document10 pagesThe Effectiveness of Class Heterogeneity in Academic Performance of Junior High School Students of MCHL Chapter 1 Research G 3 1 1 1Yuane DomingonoNo ratings yet

- Socialization and Education: Education and LearningFrom EverandSocialization and Education: Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Grace To You:: Unleashing God's Truth, One Verse at A TimeDocument14 pagesGrace To You:: Unleashing God's Truth, One Verse at A TimeNeo LamperougeNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 3 Overview of The Costing TechniquesDocument109 pagesChapter - 3 Overview of The Costing TechniquesIsh vermaNo ratings yet

- Notice No. 08-2022 2nd Phase of Advt. No. 02-2022Document10 pagesNotice No. 08-2022 2nd Phase of Advt. No. 02-2022Sagar KumarNo ratings yet

- UPDocument178 pagesUPDeepika Darkhorse ProfessionalsNo ratings yet

- Spartanburg Magazine SummerDocument124 pagesSpartanburg Magazine SummerJose FrancoNo ratings yet

- Perspective of Philosophy Socrates: Socratic/Dialectic Method Plato'S Metaphysics (Theory of Forms)Document5 pagesPerspective of Philosophy Socrates: Socratic/Dialectic Method Plato'S Metaphysics (Theory of Forms)Alexándra NicoleNo ratings yet

- Tax 2Document288 pagesTax 2Edelson Marinas ValentinoNo ratings yet

- ECO402 Solved Mid Term Corrected by Suleyman KhanDocument15 pagesECO402 Solved Mid Term Corrected by Suleyman KhanSuleyman KhanNo ratings yet

- University Institute of Legal StudiesDocument62 pagesUniversity Institute of Legal StudiesnosheenNo ratings yet

- 2.2.2 Knowledge About Antenatal Care Services and Utilization of ANC ServicesDocument3 pages2.2.2 Knowledge About Antenatal Care Services and Utilization of ANC ServicesDanielNo ratings yet

- Critique DraftDocument4 pagesCritique DraftJuan HenesisNo ratings yet

- Ebook4Expert CollectionDocument217 pagesEbook4Expert Collectionnimisha259No ratings yet

- Fringes M IVDocument20 pagesFringes M IVrandomman5632No ratings yet

- 'AJIRALEO - COM - Field Report - SAMPLEDocument25 pages'AJIRALEO - COM - Field Report - SAMPLEgele100% (1)

- Okeke, Ogechi Lilian: BiodataDocument3 pagesOkeke, Ogechi Lilian: BiodatafelixNo ratings yet

- Smash Hits 1979 10 18Document30 pagesSmash Hits 1979 10 18scottyNo ratings yet

- Notes On Solar Power1Document2 pagesNotes On Solar Power1jamesfinesslNo ratings yet

- Book Building MechanismDocument18 pagesBook Building MechanismMohan Bedrodi100% (1)

- Accounting For Business CombinationsDocument32 pagesAccounting For Business CombinationsAmie Jane MirandaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance PresentationDocument146 pagesCorporate Governance PresentationCompliance CRG100% (1)

- Report Appendix PDFDocument5 pagesReport Appendix PDFRyan O'CallaghanNo ratings yet

- Land Revenue ActDocument2 pagesLand Revenue ActPeeaar Green Energy SolutionsNo ratings yet

- AIM Vs AIM Faculty AssociationDocument2 pagesAIM Vs AIM Faculty AssociationAgnes Lintao100% (1)

- DM30L Steel TrackDocument1 pageDM30L Steel TrackWalissonNo ratings yet

- Natural DisastersDocument22 pagesNatural DisastersAnonymous r3wOAfp7j50% (2)

- Leading Change in Multiple Contexts - n12Document6 pagesLeading Change in Multiple Contexts - n12Liz LuxtonNo ratings yet

Cohen ProducingEqualStatusInteraction 1995

Cohen ProducingEqualStatusInteraction 1995

Uploaded by

thaopnguyen2512Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cohen ProducingEqualStatusInteraction 1995

Cohen ProducingEqualStatusInteraction 1995

Uploaded by

thaopnguyen2512Copyright:

Available Formats

Producing Equal-Status Interaction in the Heterogeneous Classroom

Author(s): Elizabeth G. Cohen and Rachel A. Lotan

Source: American Educational Research Journal , Spring, 1995, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring,

1995), pp. 99-120

Published by: American Educational Research Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1163215

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1163215?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Educational Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to American Educational Research Journal

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Educational Research Journal

Spring 1995, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 99-120

Producing Equal-Status Interaction in the

Heterogeneous Classroom

Elizabeth G. Cohen

Rachel A. Lotan

Stanford University

Emphasis on tracking and ability grouping as sources of inequality a

as goals for reform ignores processes of stratification within heterogeneou

classrooms. Research literature on effects of classroom status inequalit

reviewed. The articlepresents a test of two interventions derivedfrom exp

tion states theory and designed to counteract the process of stratifica

in classrooms using academically heterogeneous small groups. The de

focuses on variation in the frequency with which teachers carried out statu

treatments in 13 elementary school classrooms, all of which were using

same curriculum and the same system of classroom management. Th

was good support for the hypotheses that the use of status treatments wo

be associated with higher rates of participation of low-status students

would have no effect on the participation of high-status students. Ana

at the classroom level revealed that more frequent use of these treatm

was associated with more equal-status interaction.

ELIZABETH G. COHEN is Professor of Education and Sociology, Center for Edu

tional Research 207N, School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94

3084. She specializes in sociology of education, classroom social structure, and or

zation of teaching.

RACHEL A. LOTAN is Senior Research Scholar, Center for Educational Rese

207N, School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-3084. She spe

izes in sociology of the classroom and social organization of schools and group w

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

Sociological

structuralresearch onschools

features of sources

andof inequality

classrooms suchinaseducation hasability

tracking and emphasized

grouping (Oakes & Lipton, 1990; Gamoran, 1987; Vanfossen, Jones, & Spade,

1987; Useem, 1992). Classroom studies of low-track and low-ability groups

reveal the mechanisms and processes by which these organizational features

of segregation are translated into depressed academic performance (Eder,

1981; Gamoran, Berends, & Nystrand, 1990; Hallinan, 1990; Oakes, 1985).

Structural explanations lead to recommendations for reform that are also

structural-such as, untracking the secondary school and minimizing the use

of ability grouping at the elementary level (Carnegie Council on Adolescent

Development, 1989; Massachusetts Board of Education, 1990). Current reform

efforts springing from this line of research are leading more and more schools

to move toward academically heterogeneous classrooms.

Exclusive emphasis on structural sources of inequality and structural

reform, however, ignores important sociological theory and research on

processes of stratification in heterogeneous social settings. If it is the case

that processes of stratification within heterogeneous classrooms can produce

severe inequalities, then the neglect of this sociological knowledge will be

very costly. If students in heterogeneous classrooms develop new status

orders that have the effect of depressing the participation and effort of low-

status students, then the current wave of reform will simply substitute new

forms of inequality for the old. Depressed rates of participation predict

lowered achievement as early as the first three grades (Finn & Cox, 1992).

Cooperative learning is widely recommended as a method of creating

equity in heterogeneous classrooms. However, small groups will also develop

status orders based on perceived differences in academic status: high-status

students will interact more frequently than low-status students. Moreover,

these differences in interaction can lead to differences in learning outcomes--

that is, those who talk more, learn more (Cohen, 1984).

The goal of this article is to apply expectation states theory to this

problem of unequal status interaction in heterogeneous classrooms. Expecta-

tion states theory explicates stratifying processes that arise in classrooms and

produce status orders associated with academic and social characteristics

of students. We report on a controlled observational study of instructional

interventions derived from this theory. We will focus on variation in the

frequency of the use of these interventions among a set of classrooms, all

using the same curriculum and method of classroom management.

The Interventions: Derivation, Design, and Hypotheses

Expectation states theory (Berger, Cohen, & Zelditch, Jr., 1966, 1972) offers

an explanation for the dominance of high-status actors, even when the

differences in status are irrelevant to the task. Status generalization is the

process by which status characteristics come to affect interaction and influ-

ence so that the prestige and power order of the group reflects the initial

differences in status. (For a full description of this process, see Berger, Rosen-

holtz, & Zelditch, Jr., 1980). Status characteristics, a central concept of this

100

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

theory, are defined as socially evaluated attributes of individuals for which

it is generally believed that it is better to be in the high state than the low state.

When a status characteristic is specific (such as, occupation, skill, and

training), knowledge of the characteristic provides specific performance

expectations for individuals who are in the high and low states of the charac-

teristic. Academic status characteristics, such as those based on perceived

differences in ability in reading or math, are prime examples of specific status

characteristics in the classroom. When a status characteristic is diffuse (such

as, race, gender, or ethnicity), general expectations for competence and

incompetence will be activated by collective tasks; these expectations operate

in the same way as expectations based on specific status characteristics.

Classroom Status Inequalities and Student Interaction

When the educator assigns a collective, cooperative task to a group, status

differences based on academic ability become activated and relevant to the

new situation, even if the task does not require the academic ability on which

the group differs. Because of differences in perceived academic ability, the

high-status student will then expect to be more competent and will be

expected to be more competent by others. The net effect is a self-fulfilling

prophecy whereby those who are seen as having more ability relative to the

group in schoolwork or in reading tend to dominate those who are seen as

having less ability relative to the group in schoolwork or reading (Hoffman,

1973; Rosenholtz, 1985; Tammivaara, 1982; Webb & Kenderski, 1984).

Differences in status are always relative rather than absolute. One's own

status is relative to the status of other members of the group. For example,

the effects of perceived ability can be distinguished from actual differences

in ability. In contrast to measures of perceived ability, measures of actual

ability do not predict interaction and achievement gains (Webb & Kenderski,

1984). Dembo and McAuliffe (1987) created an artificial distinction of average

and above-average ability with a bogus test of problem-solving ability,

described as relevant to an upcoming experimental task. Higher status stu-

dents (defined as those publicly assigned above-average scoring on the

bogus test) dominated group interaction on the experimental task, were

more influential, and were more likely to be perceived as leaders than low-

status students.

Academic status characteristics are the most powerful of the status char-

acteristics in the classroom because of their obvious relevance to classroom

activities. In responding to hypothetical learning groups on a questionnaire,

students were much more likely to approve leadership behavior on the part

of a good student than on the part of Whites or males (McAuliffe, 1991).

Studies documenting the effects of diffuse status characteristics (such

as, social class and race) among schoolchildren have primarily taken place

in laboratories. Because these diffuse status characteristics tend to correlate

with states of academic characteristics (such as, ability in mathematics), it

has been difficult to document these effects separately in groups composed

of students in a single classroom (Cohen, 1982). When academic status is

101

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

uncontrolled, the effects of ethnicity in small classroom groups have been

clearly shown (Sharan & Shachar, 1988).

Although gender is a powerful basis for the organization of social behav-

ior in school, it does not appear to operate as a status characteristic until the

middle school years (Lockheed, Harris, & Nemceff, 1983). Consistent with

the conclusions of Lockheed et al., Leal (1985) found no evidence of gender as

a status characteristic in mixed sex groups working cooperatively at learning

centers. Differences in perceived attractiveness or popularity--that is, peer

status--are also the basis for status generalization (Maruyama & Miller, 1981;

Webster & Driskell, 1983).

Modifying Status Inequalities

We hypothesize that teachers can alter the status processes in a heterogeneous

classroom by altering the expectations for competence that students hold

for themselves as well as expectations they hold for one another. Of central

interest here are two interventions: the multiple ability treatment and

assigning competence to low-status students.

In an effective multiple ability treatment, the teacher and students discuss

the many different intellectual abilities required by the collective tasks (e.g.,

reasoning, creativity, and spatial problem solving). Moreover, the teacher

says, "None of us has all these abilities; each one of us has some of these

abilities." Theoretically, this intervention produces a mixed set of expecta-

tions for competence for each student rather than uniformly high or low

expectations.

Although this intervention was directly inferred from the theoretical

description of the process of status generalization, the basic idea of multiple

intellectual abilities is consistent with recent developments in the psychologi-

cal study of human intelligence. The work of psychologists such as Sternberg

(1985) and Gardner (1983) suggests multiple intelligences as a heuristic

conceptualization rather than the concept of a single intelligence represented

by the IQ score.

The multiple ability treatment proved effective in weakening status

effects in a laboratory study (Tammivaara, 1982) and in a controlled classroom

experiment (Rosenholtz, 1985). In classrooms using the same instructional

methods as this study, the multiple ability treatment reduced but did not

eliminate effects of status on interaction (Cohen, Lotan, & Catanzarite, 1988).

Both expectation states theory and source theory (Webster & Sobieszek,

1974) provide the basis for another status treatment: assigning competence

to low-status students. As a high-status person, the teacher's evaluations

have a strong influence on students' evaluations of themselves (Webster &

Sobieszek, 1974). The higher the status of an individual, the greater is the

likelihood of that individual becoming a source of important evaluations

and thus influencing one person's self-evaluations relative to another. If the

teacher, as a high-status source, positively evaluates a series of classroom

tasks by a student, that student will come to believe that his or her ability

is consistent with the teacher's evaluation. That belief will in turn affect the

102

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

student's expectations for competence in classroom tasks. In a classro

experiment designed to test this proposition, Entwisle and Webster (19

found that students who had received positive evaluations from the teac

were more likely to raise their hands to volunteer a response to the teacher

than students who had not received positive evaluations from the teach

Teachers who use this treatment watch for instances of low-status stu-

dents performing well on various intellectual abilities that are relevant to

success on classroom tasks, such as observing astutely, being precise, or

being able to use visual thinking. The teacher then provides the student with

specific, favorable, and public evaluations so that high-status members will

also hear and accept the teacher's evaluation. For example, on observing

the neglect of a low-status child who did not speak English by the other

bilingual members of the group, one teacher said:

Luis is really looking at the (activity) card when he is building this

structure and following the diagram on the card. He puts one straw

across like this to make it stronger. He's really doing that by following

the diagram. You know, that is a great ability to have because he

could be an architect. So he's a great resource here in this group

because you guys can rely on him to make your structure much

stronger. (She repeated the treatment in Spanish for Luis' benefit.)

You need to tell Luis what you want to do because he is the one who

is a resource here, but he has to understand. Otherwise he can't help

you. (Cohen, 1994)

This treatment should not be confused with unconditional teacher praise

and reinforcement often used in psychological research on teacher-student

interaction. Before assigning competence, the teacher must wait until the

student performs impressively on particular abilities. The feedback has to

be public, highly specific, and valid so that the student and other members

of the group will find the evaluation believable and understand precisely

what was done well. Furthermore, the teacher spells out the relevance of

this intellectual ability to the task at hand and/or to adult problem-solving

experience. This last step represents the formation of a relevance bond

between the newly assigned competence and the task at hand. Berger and

Fisek (1970) hypothesized that specifying relevance would raise the probabil-

ity of transfer because the participants would perceive that the new task was

similar to the task where a group member had just received a high evaluation

of his or her competence.

If the student and his or her peers accept the teacher's evaluation of

the low-status student as competent on an impressive and relevant ability,

then expectations for competence on this specific status characteristic should

combine with other expectations for competence (both high and low) held

by and for the individual. The net result of successful treatment will be higher

participation and influence on the part of the low-status group members

relative to that of the high-status group members. Research has shown the

power of these newly assigned expectations for competence to transfer to

103

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

new task situations (Berger et al., 1980; Webster & Foschi, 1988). The transf

of successfully treated expectations to new situations means that the teache

does not have to continually treat the same low-status individuals. Nor i

theoretically sound to assume that the more frequently the teacher treats t

same group, the higher will be the interaction and influence rates of

low-status members of that group.

More concretely, as Candida Graves, one of the teachers whose clas

room was part of this study reports, a single successful treatment may

sufficient to change a student's standing with his class:

One day I had a student named Juan. He was extremely quiet and

hardly ever spoke. He was not particularly academically successful

and didn't have a good school record. He had just been in the country

for two or three years and spoke just enough English to be a LEP

student. I didn't notice that he had many friends, but not many enemies

either. Not that much attention was paid to him.

We were doing an activity that involved decimal points, and I

was going around and noticed he was the only one out of his group

that had all the right answers. I was able to say, "Juan! You have

figured out all of this worksheet correctly. You understand how deci-

mals work. You really understand that kind of notation. Can you

explain it to your group? I'll be back in a minute to see how you

did." And I left. I couldn't believe it: He was actually explaining it to

all the others. I didn't have faith it was going to work, but in fact he

explained it so well that all of the others understood it and were

applying it to their worksheets. They were excited about it. So then

I made it public among the whole class, and from then on they began

calling him "the smart one." This spread to the area where he lived,

and even today kids from there will come tell me about the smart

one, Juan. I thought, All of this started with a little intervention!

(Graves & Graves, 1991)

The first two hypotheses are at the individual level, while the third is

the classroom level. At the individual level, low-status students in successfu

treated classrooms should have a higher rate of participation in mixed statu

groups as a result of higher expectations held for their competence. Furthe

more, because the teacher has presumably concentrated on assigning compe-

tence to low-status students, there should be no effect in successfully treat

classrooms on the rate of participation of high-status students in mi

status groups.

The strength of the relationship between status and interaction within

the small groups is a classroom-level phenomenon. In order to bring abo

equal-status interaction, the teacher must make the expectations for compe

tence for low- and high-status students more nearly equal. If she is successf

in doing so, this should lead to a third observable result where the unit

analysis is the classroom: when expectations for competence are more nearly

equal in a classroom, the relationship of the status of each student to t

104

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

rate of interaction of that student should be weaker than in classrooms where

there are sharp differences in expectations for competence.

This reasoning allows us to develop three hypotheses for the study:

1. The rate of participation of a low-status student in mixed status

groups will be positively related to the frequency of the use of status

treatments by that student's teacher.

2. The rate of participation of a high-status student in mixed status

groups will be unrelated to the freqency of the use of status treatments

by that student's teacher.

3. At the classroom level, the frequency with which the teachers use

status treatments will be negatively related to the strength of the

correlation between status and interaction in their classrooms.

We expect these hypotheses to hold under two conditions. One is the

use of a curriculum with tasks that require a broad range of intellectual

abilities. If the curriculum activities include a broader range of abilities and

are not restricted to conventional academic skills, it is then more likely that

students or teachers would believe that every student would have at least

one of the requisite intellectual abilities or that no student would have all

the abilities. The second is a method of classroom management that permits

and sustains a high rate of interaction between the students. Interaction is

important to the success of these interventions because it allows peers to

witness the competence of the low-status student on the task. In addition,

following the teacher's intervention, interaction on a group task allows further

opportunities for the low-status students to be recognized for their intellec-

tual contributions.

An exploratory question in this study is the effect on the low-status

student of playing an authoritative role such as that of the facilitator. As

facilitators, students have the opportunity to direct the behavior of others in

the course of group interaction. Theoretically, holding such a powerful posi-

tion with respect to peers may well raise expectations for competence for

the low-status student as well as the expectations for competence the low-

status students hold for themselves. We will examine the effect of playing

the role of a facilitator on the low-status student's participation rate.

Sample and Setting of the Study

Thirteen classrooms, Grades 2-6 in three schools in the San Francisco Bay

area, constituted the sample of the study. The number of students in these

classrooms ranged from 21 to 30, with an average of 27 students. Large

proportions of these students were from language minority and low-income

backgrounds. These were also segregated classrooms. Students in two class-

rooms were Southeast Asian immigrants with limited proficiency in English.

Nine classrooms were predominantly Hispanic, and the remaining two were

a mixture of low-SES Anglos, Asians, and Hispanics. Despite the similarity

in ethnicity and SES within most of these classrooms, there was heterogeneity

105

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

in academic skills ranging from grade level performance to an inability

read and write in any language.

In order to determine the effect of status on interaction, we selected a

subset of target students in each classroom for intensive scoring of th

participation within small groups. There were 61 low-status students and 6

high-status students in the target sample.

The 13 teachers who taught these classrooms had participated in a

week workshop at Stanford University in the summer of 1984. During

workshop and the year-long follow-up by the Stanford staff, the teach

learned about complex instruction, an instructional strategy for hetero

neous classrooms. Complex instruction requires the teacher to assign studen

to small mixed gender groups composed of students with different levels o

achievement as well as mixed proficiency in English. Teachers used Find

Out/Descubrimiento (FO/D), an English-Spanish math and science curr

lum for the elementary school grades. All teachers were instructed in

strategies for the treatment of status problems. In addition, some teach

participated in a supplementary training designed to boost the us

assigning competence to low-status students.

The nature of instruction matched the two conditions laid out above.

The tasks required problem solving and utilized manipulatives. Successful

completion of these tasks required a wide range of intellectual abilities. Aside

from reading, writing, and computing, these abilities included reasoning,

hypothesizing, visual and spatial thinking, careful observing, precision in

work, and interpersonal skills. The methods of staff development included

a classroom management system designed to ensure a high proportion of

students talking and working together (Cohen, Lotan, & Leechor, 1989).

Within the cooperative group, each student played a different role (e.g.,

facilitator, reporter, checker, clean-up monitor); these roles were rotated

regularly. There was variability in the teacher's ability to implement this

management system and so maintain a high level of interaction.

Measures

Independent Variables

The teachers' use of status treatments was indicated by two kinds of tea

talk: talking about multiple abilities and assigning competence to low

students. Trained bilingual observers, using the teacher observation

ment, gathered data on these teaching behaviors during complex instruc

For 10 minutes during each observation period, observers tallied th

quency with which teachers talked about multiple abilities and ass

competence and the frequency with which they engaged in a num

other categories of talk not relevant to this analysis. A total of 285 obser

were collected, with an average of 21.9 ten-minute observations per teac

No teacher was observed less than 17 times. Tests of reliability yiel

average of 91.48% agreement between observers.

106

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

To calculate the average rates of teachers' use of status treatments, the

total frequency of these two kinds of speech acts was divided by the number

of observations for each teacher. An analysis of variance was calculated for

the entire set of individual observations. Teachers were a significant source

of variation; for talk about multiple abilities, F = 1.88, p < .05; for assigning

competence, F = 3.58, p < .00. The frequencies of the two types of status

treatments were added together to create a general status treatment variable.

This was the statistic used in tests of hypotheses.

To answer the exploratory question, we used the measures of students

talking and behaving like a facilitator: Observers systematically scored these

behaviors on repeated occasions for 3-minute periods (see more detailed

description of the Target Student Observation Instrument in the following

section of the article). We added these together and calculated an average

rate across observations for each target child. Although low-status students

were assigned the role of the facilitator as often as other students, they did not

necessarily play the role actively. Thus, this is a measure of implementation of

the facilitator role.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables of the first two hypotheses require an estimate of

the rate of participation of low- and high-status students. In order to measure

this participation, it was necessary to select a target sample of students who

were perceived as low and high status. Prior to any intervention, sociometric

instruments were administered to all students in English and Spanish versions

in the 13 classrooms that participated in the study. Students were asked to

circle the names of those in their class who were "best at math and science"

or their "best friends."

Because students could circle any number of names, the number of

choices indicated for each question varied among students and among class-

rooms. The distribution of choices for each question was divided into

quintiles for each classroom. Each child was then assigned a score ranging

from 1-5, depending on the fifth of the distribution in which lay the number

of times that child's name was chosen.

The two questions mentioned above made up the measure of status.

Because the status treatments took place while children were working on

math or science tasks, the specific status characteristic of ability in math and

science was the one most directly relevant to the learning tasks. The question

of best friends was used as an indicator of peer status. For a single measure

of status, the two quintile scores were added together and a costatus score

ranging from 2-10 was created (see also Cohen, Lotan, & Catanzarite, 1988).

Using the combining principle, a basic tenet of the theory well substantiated

by research, the values were added, because participants will aggregate status

information (Humphreys & Berger, 1981).

After the costatus scores were calculated for all students, we selected

target students from each classroom, seven from the upper and seven from

the lower end of the distribution of the costatus scores. All students who

107

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

had a score of 2 or 3 and all students who had a score of 9 or 10 were

selected. We then made a random selection among those scoring 4 or 8 in

order to make up the quota of 14 target students per classroom. Because o

the high transiency rates in some of these schools, we were not able to

collect a complete set of observations on all the selected students. (See Tab

1 for the number of target students per classroom.) There were at least s

observations for all 128 children in this study.

Using the target child observation instrument, the observers recorded

the frequency of task-related talk and non-task-related talk. For example, in

a group of students learning about magnification by making a water lens

Geraldo looks into his lens and says, "Look how big mine got." "What are

you going to write?" a girl in the group asks him. Geraldo looks into the

lens again and says, "It gets bigger" (Navarrete, 1980, pp. 13-14). If Gerald

were a target child, this bit of interaction would be scored as two instances

of task-related talk because his speech was interrupted by the speech of his

colleague. Procedural talk about cooperation and roles was scored as two

separate types of talk. Also scored was talking like a facilitator-for example,

"Does everybody understand?"-as well as behaving like a facilitator (point

Table 1

Indexes of Status Problems, Variability in Reading Scores, and

Classroom Level of Talk/Work by Classroom

Index of SD Class level N of

Classroom status reading rate of target

ID problems+ test talk/work + + students

1 .55* 1.04 8.92 12

2 .23 .48 10.66 10

3 .27 .78 7.13 9

4 .31 .73 10.87 8

5 .59** 1.3 4.73 10

6 .41 .78 7.71 10

8 .12 .66 10.07 9

9 .42 1.02 6.17 11

10 -.10 .81 6.88 10

11 .14 .94 5.89 10

12 .28 .80 8.20 12

13 .32 1.07 5.46 12

Overall .32 .87 7.67

Mean

SD .20 .22 1.93

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

+Correlation of costatu

+ +Class level of talk/w

working together for a

108

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

ing or directing others how to behave). The observation instrument was

divided into six 30-second intervals, so that, if a child were talking about

the task continuously during the observation, he or she would be scored 6

times. If a child shifted from task-related talk to talking like a facilitator and

back to task-related talk within a 30-second interval, he or she could receive

more than one score for task-related talk per time interval. An instance of

talk or behavior in any of the categories was scored by a single check as

long as it was not interrupted by another student talking or by a change of

category. Interobserver agreement on the target child instrument was 92.93%.

To calculate an average rate of talking or behaving across observations,

the total frequency of these speeches and behaviors was divided by the

number of observations for each child. An analysis of variance of individual

observations showed that the child was a significant source of variation for

task-related talk: F = 7.7; p < .001. Individual participation was measured

by adding task-related talk and talk about cooperation and roles and by

averaging the set of observations for each individual in the target sample.

We combined task-related talk and talk about cooperation and roles because

the theory indicates that all performance outputs are valid measures of the

prestige and power order of the group (Berger, Cohen, & Zelditch, Jr., 1966).

For the same reason, non-task-related talk was omitted from the measure

of participation.

Index ofstatus problems. Operationally, the severity of status problems

in a classroom is measured by the relationship between the costatus scores

of each target student and the average of his or her observed individual rate

of interaction. The index of status problems is the correlation coefficient

(Pearson r) of target students' costatus scores and the observed average rate

of peer task-related talk during work at learning centers, in each of the 13

classrooms. Among these treated classrooms (see Table 1), there were two

with a positive coefficient between status and interaction that was statistically

significant, indicating that the higher the status of the student, the more active

he or she was within the small groups. In all the other classrooms, there

were no statistically significant relationships between status and interaction;

in several classrooms, the relationship was close to zero,' indicating no

observable status problems.

Control Variables

In the analysis of individual rates of participation, it was necessary to control

the general rate of interaction in the classroom. Teachers varied as to how

well they achieved the desired high level of interaction, as measured by the

grand mean for rate of task-related talk plus the observed rate of the child

working together with others for all target children (target child observation

instrument) in a classroom. If a student were in a classroom where the teacher

promoted a high general level of interaction, then the individual's rate of

participation was likely to be higher than in a classroom where the average

rate of interaction was lower. This statistic is given for each classroom in

Table 1 (Classroom Level of Talk/Work).

109

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

In the analysis of status problems at the classroom level, it was neces

to control on variability in academic achievement. Some of these classroom

were extremely heterogeneous in academic skills (see Table 1). T

included newcomers to the country who might have been illiterate in eith

English or in their native language. When there are dramatic differences

academic skills, the effects of status problems on interaction will be

visible. These effects will be less evident if the children are approxim

equally likely (or equally unlikely) to be able to read the activity card

fill out the worksheets that were part of the curriculum materials. This co

of variability was measured by the standard deviation of reading scores f

students in a classroom on the California Test of Basic Skills administered

in the fall.

Figure 1 summarizes each of the independent, dependent, and contro

variables for the hypotheses. In each case, the source of the variable in a

instrument is cited.

Results

The means and standard deviations for the variables of the study are pre

sented in Table 2. Turning first to the data on the children, target students

talked about the task on the average more than four times per 3 minutes

On the average, high-status students participated at a significantly highe

rate than low-status students (t = 1.81; p < .05). Although all students ha

an equal chance to play the role of facilitator, high-status students were muc

more likely to behave and talk like a facilitator (t = 2.67; p < .01).

For teachers, the average rate for using each of the status treatments was

quite low-less than one third of an instance per each 10-minute observation

period. Some teachers had scores of zero on one or both treatments. Other

did a status treatment as often as once every 10 minutes.

Concept Indicator Source of Data

Independent Variable Status Treatment Talks about Multiple Teacher Observation

Abilities + Instrument

Assigns Competence to

Low-Status Students

Facilitator Role Student Talks and Target Stdt. Obs.

Behaves like a Instrument

Facilitator

Dependent Variable Participation Task-Related Talk + Target Student Obs.

Talk about Cooperation Instrument

and Roles

Status Problems Correlation of Costatus Sociometric Qst.

with Task-Related Talk Target Stdt. Obs.

in Classroom Instrument

Controls Classroom Inter- Grand Mean of Average Target Stdt. Obs.

action Rate of Task-Related Instrument

Talk + Rate of Working

Together:Target Children

Variability in S.D. of scores on CTBS CTBS

academic skills per classroom

Figure 1. Summary of concepts, indicators, and so

110

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

Table 2

Means, Ranges, and Standard Deviations of Variables: Individual

and Classroom Level

Individual level variables

N Mean Range SD

Rate of participation

Low status 61 4.09 1.00-8.57 1.82

High status 67 4.63 1.50-8.63 1.55

All target Ss 128 4.37 1.00-8.63 1.69

Facilitator talk/

behavior

Low status 61 .69 0.00-2.86 .75

High status 67 1.08 0.00-4.13 .88

All target Ss 128 .89 0.00-4.13 .84

Classroom level variables

Teacher use of status

treatments

Mult. abil. 13 .29 0.00- .88 .31

Assign. comp. 13 .25 0.00-1.00 .31

Status

treatments 13 .53 0.00-1.88 .57

Individual Level Analysis

In order to test the hypothes

the frequency of status trea

predictor along with the aver

the child's rate of talking an

intercorrelations of all the va

Table 4 shows the results of the

rates on the rate of the teacher's talk in which he or she used status treatments.

The frequency of the teacher's use of status treatments had a statistically

significant positive effect on the participation rate of the low-status student.

The rate at which the low-status student talked or behaved like a facilitator

also had a positive effect on his or her participation rate, but, in this case,

the effect was not statistically significant. The strongest predictor of the

individual's participation rate in this equation was the average rate of interac-

tion in the classroom.

Table 5 presents the results of the test of the second hypothesis concern

ing the rate of participation of high-status students. Some people fear th

treatment of low-status students is at the expense of high-status student

Although the assigning competence treatment focused on low-status stu

dents, teachers felt free to assign competence to all students. Table 5 sho

111

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

Table 3

Intercorrelation of Variables for Individual Level of Analysis

Low-status students (N = 61)

Facil. talk/ Class Status

Participation behavior talk/work treatments

Participation 1.00

Facilitator talk/

bhvr. .369* 1.00

Classroom level

talk/work+ .580** .412** 1.00

Status treatments .006 -.187 -.277* 1.00

High status students (N = 67)

Participation 1.00

Facilitator talk/

bhvr. .343** 1.00

Classroom level

talk/work .654** .382** 1.00

Status treatments -.198 -.311** -.252* 1.00

*p < .05.

**p < .01.

+Classroom level talk/work = grand mean of average rate of task-related talk + rate of

working together for all target students.

the regression for high-status students, identical to the regression presented

in Table 4. In this regression, status treatments had no effect on participation

rate, nor did rate of talking and behaving like a facilitator. The only significant

predictor of participation of the high-status student was the average rate of

interaction in the classroom.

Classroom Level of Analysis

At the classroom level, the index of status problems becomes the dependent

variable, while the teacher's use of each status treatment becomes the inde-

pendent variable, and the variation in reading pretest scores among the

classmates serves as a control. The third hypothesis predicts that the percent-

age of teacher talk pertaining to status treatments will be negatively associated

with the index of status problems.

A scatterplot of the status treatment variables with the index of status

problems revealed one teacher as an outlier (Classroom 10, Table 1). This

teacher was never seen assigning competence and had a relatively low rate

of talking about multiple abilities. Nonetheless, her classroom provided no

evidence of status problems (r = -.103). Observers reported that this class-

room had a very special ambiance; the teacher rarely raised her voice, and

the children appeared calm and content. They consistently treated one

another with respect. It may well have been the case that the teacher did

112

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

Table 4

Regression of Participation of Low-Status Students on Frequency

of Status Treatment, Classroom Level of Talk/Work, and

Individual Rate of Facilitator Talk and Behavior

N = 61

Dependent variable = Individual rate of participation*

Predictor B Beta t p (1 tail)

Constant -.582

.000 -.67 .254

(.873)**

Facilitator talk/bhvr. .423 .175 1.54 .065

(.276)

Classroom level talk/ .526 .562 4.83 .000

work* (.109)

Status treatments .246 .194 1.80 .039

(.137)

*Does not include facilitator talk.

"**Standard error in parentheses.

R2 = .359 (adjusted).

not use status treatments because there was very little evidence of status

generalization to treat in the first place. Using a SYSTAT technique for identi-

fying outliers, the observations on this teacher were shown to have an undue

influence on the correlation (Wilkinson, 1988, p. 425). Because it was an

outlier, this classroom was omitted from this analysis.

There was a high level of intercorrelation (r = .78; p < .001) between

the use of the two status treatments. Table 6 presents the Pearson correlations

of the teacher talk regarding the two status treatments, the index of classroom

status problems, and the control variable. The rate of teachers' use of status

treatments was not significantly associated with the index of status problems,

although the relationship was in the predicted negative direction. The control

variable of variation in reading test scores was positively and significantly

related (r = .69; p < .001) to the index of status problems.

There were 11 classrooms used in the regression analysis because of

the omission of the outlier and the omission of the classroom for which we

did not have pretest scores on reading. Results, given in Table 7, show that

the status treatments were a statistically significant negative predictor of

the correlations observed between status and interaction in the classroom,

providing good support for the prediction. The variability in reading pretest

scores was a powerful positive predictor of status problems. This regression

equation accounts for more than 60% of the variance.

Discussion

Use of status treatments by teachers can significantly lessen the imp

status on small group interaction. Eleven out of 13 classrooms show

113

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

Table 5

Regression of Participation of High-Status Students on Freque

of Status Treatment, Classroom Level of Talk/Work, and

Individual Rate of Facilitator Talk and Behavior

N = 67

Dependent Variable = Individual rate of participation*

Predictor B Beta t p(1 tail)

Constant .707 .000 1.06 .295

(.670)**

Facilitator talk/bhvr. .187 .106 1.06 .316

(.185)

Classroom level talk/ .487 .610 5.90 .000

work* (.083)

Status treatments -.012 -.011 -.11 .457

(.110)

*Does not include facilitator talk.

"**Standard error in parentheses.

R2 = .413 (adjusted).

significant relationship between the measure of student status and the rate

of task-related talk. Data analysis provided support for the three hypotheses

of this study. At the individual level of analysis, the rate of teacher talk in

which he or she used the status treatments had a statistically significant

positive effect on the participation of low-status students. As predicted, these

status treatments had no effect on the rate of participation of high-status

students. At the classroom level, the teachers' use of the two status treatments

had a statistically significant negative effect on the incidence of status prob-

lems in that classroom. In other words, in classrooms where teachers used

status treatments more frequently, the high-status students did not participate

more frequently than low-status students.

Our sample included some of the most attractive and academically

successful students in the class and some of the weakest and the most socially

isolated students. Therefore, achieving equal rates of participation was espe-

cially significant in comparison to achieving equal status interaction among

classmates who have less dramatic differences in status between them. The

effectiveness of the treatments was aided by the nature of the curricular

tasks. Assuming competence expectations were altered, it was possible for

students to display intellectual competence by solving problems spatially

and visually, by communicating with the use of real objects, and by helping

others in a nonverbal fashion.

The overall frequency of teachers' use of status treatments was low.

Field experiments with status treatments have shown that it is not the number

of times but rather the fact that particular groups of students receive treatment

that counts (Cohen, Lockheed, & Lohman, 1976). One status treatment is

114

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

Table 6

Intercorrelation of Variables for Classroom Level of Analysis'

Status Status SD reading

treatments problems pretest

Status treatments 1.00

Status problems -.23 1.00

(12)

SD reading -.29 .69** 1.00

pretest (11) (11)

**p < .01.

'Numbers in parentheses indicate number of cases.

sufficient to modify competence expectations held by self and others for a

particular student in ways that will persist over a series of collective tasks.

Interviews with teachers who have used these treatments suggest that

they begin to see new evidence of their students' intellectual abilities that

they had never perceived before. In the words of one teacher:

Almost all the children in FO/D have multiple ability skills. First, I

used to have trouble defining them, but now I see, and I get it from

the children, what kind of abilities or what kind of skill you need to

work this. It is really amazing how many different skills you have to

have to do one task that seems simple on the surface.

The teachers were particularly gratified to see the changes in low-status

students to whom they had assigned competence. The quotation from Can-

dida Graves earlier in this article illustrates this surprise and satisfaction.

Table 7

Regression of Index of Classroom Status Problems on Teachers'

Fate of Status Treatment and Standard Deviations of Reading

Pretest Scores

N=11

Predictor B Beta t p(1 tail)

Constant -.082 .000 -.697 .252

(.117)*

Status treatments -.120 -.487 -2.377 .023

(.050)

SD reading .578 .828 4.043 .002

pretest (.136)

*Standard error in parenthes

R2 = .692 (adjusted).

115

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

With regard to the exploratory question, talking and behaving l

facilitator had a positive effect, but it did not quite reach the .05 le

significance. Some low-status students were never seen playing the r

facilitator although all students had equal time assigned to that role

possible that, if a teacher were to take the time to encourage and d

this role for low-status students, one might well see stronger positive ef

Status Inequalities and Achievement

Educators would not ordinarily worry about the impact of status on inte

tion unless unequal interaction had an effect on the learning process. In

landmark review of interaction in small groups and learning, Webb

selected the activity rate of the individual within the group and whethe

not individuals were able to use the group as a resource to understan

task as key predictors of learning. Similarly, Cohen (1984) found that, h

constant a student's status, the amount of interaction was a predict

learning gains.

With the instructional approach used in this study, the amount of int

tion, whether at the classroom level (Cohen, Lotan, & Leechor, 1989)

the individual level (Leechor, 1988), is a strong predictor of gains in scor

standardized achievement tests, especially for the lower achieving studen

Many of the low-status students would also be classified as low-achie

students. Thus, their access to interaction is critically important to

achievement. In this data set, where status problems have been gre

weakened, regressions at the classroom level show that status is not

dictor of learning gains (Leechor, 1988, p. 118).

Limitations of This Research

Despite the considerable number of students and observations involv

the collection of data, the small sample of classrooms is an obvious diffic

in the present analysis at the level of the classroom. Regressions carried

on a sample of 11 raise issues of reliability of the results. However, we w

able to correctly estimate effects on separate samples of low- and high-s

students using a different dependent variable, but the same indepen

variable. These analyses provide some assurance that the results at the cla

room level are not the product of some strange fluke of the data. Accord

to one reviewer of this article, the authors have "approximated the hiera

cal linear modeling approach in their statistical work, but it lacks elegan

Until HLM techniques are adapted for smaller size samples, this "approxim

tion" appears to be the best available solution.

Ideally, it would have been desirable to estimate the independent eff

of each of the status treatments separately. Given that rates for the two s

treatments were closely associated, we cannot really estimate the str

of one treatment in comparison to the other.

Testing the effects of status treatments by examining the participat

rates of all low-status students is a peculiarly sociological strategy. An ex

116

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

mental approach would call for knowing which students were treated and

for following the participation of these particular students before and after

treatment. However, the status treatments are not aimed exclusively at low-

status individuals; they treat expectations of all students for the competence

of the low-status students. Because one or two treatments are sufficient to

change these expectations, it is unlikely that one would observe that treat-

ment in a set of observations. Thus, we assume that the effect of a higher

rate of treatment will be observable in a sample of low-status students in

classrooms where expectations have been treated. A more experimental

approach has distinct advantages, especially when the factors affecting stu-

dent participation become more complex, as in the middle school.

Theoretical Implications

Elimination of status differences in interaction in heterogeneous classrooms

is of special interest because several features of the situation ordinarily lead

to the phenomenon of status generalization. Given the curriculum used, the

status characteristic of perceived excellence in math and science was highly

relevant to the collective tasks. The more relevant a status characteristic is,

the more power it has to affect the prestige and power order of the small

group. Because it is not possible to eliminate the competence expectations

based on differences in academic and peer status, the fact that status was

unrelated to interaction in most of these classrooms suggests that the treat-

ment may well have broken the bonds of relevance between the academic

status characteristic and the activities of the curriculum.

In the only previously published study in which teachers attempted

to raise student expectations for competence, teachers simply reinforced

contributions made by low-status students (Entwisle & Webster, 1974). The

child's actual ability was virtually irrelevant to the capacity to supply words

in a story skeleton. Regardless of the child's response, children in the experi-

mental group were systematically reinforced and praised for every contribu-

tion. Quite apart from the obvious undesirability of unconditional

reinforcement of students, the treatment used in this study represents a

theoretical as well as a more educationally desirable advance over this early

experimental version. In the first place, this treatment manipulates expecta-

tions of others as well as those of the low-status student. In the second place,

making competence relevant to the task makes the low-status student a

valued resource for the group.

Assigning the role of facilitator to a low-status student, because it involves

directing the behavior of others, has considerable theoretical interest as a

method of modifying expectations for competence. These behaviors act as

task cues in the interaction of the group (Berger, Wagner, & Zelditch, Jr.,

1985, p. 54). Task cues provide information that is relevant to the task

characteristic possessed by the actors in the situation. Among the most

important task cues that have been studied are speech rates, fluency, tone,

and eye gaze. Members will take these cues as indicators of competence or

a high state on a specific status characteristic. If the group members conclude

117

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cohen and Lotan

that the low-status student is in the high state on a specific status characterist

that is relevant to the success of the group, then we would expect tha

expectations for his or her competence would be higher than if the facilitato

role were not played.

Practical Implications

Administrators and teachers in schools in which tracking and ability groupin

have been eliminated are deeply concerned with feasible instruction fo

heterogeneous classes. These educators have already discovered that the

have exchanged severe problems of status differences between tracks an

ability groups for equally severe problems of status differences within class-

rooms. Many perceptive teachers have also found that cooperative learnin

techniques so widely recommended for this setting do not solve these status

problems. The finding concerning the impact of a wide range in reading

skills attests to the status problems facing teachers who use heterogeneou

cooperative groups.

In the context of a multiple ability curriculum, it is possible to produce

equal-status behavior in heterogeneous classrooms as well as significant

gains in achievement. Expectations for competence can be treated in suc

a way as to raise the participation of low-status students without depressing

the participation of high-status students. Moreover, it is possible to produce

equal-status behavior in classrooms where the presence of newcomers wh

lack English proficiency can create severely depressed expectations for com-

petence on the part of low-status students. Strategies of treating status that

are derived from expectation states theory are practical and workable in

modifying the stratification processes that take place within heterogeneous

classrooms.

Note

'The estimate of the relationship between status and interaction is probably inflated

due to the selection of extreme values from the distribution of costatus scores. However,

for the purposes of testing the hypothesis, it is the relative strength of the coefficients that

is at issue and not their absolute values. In order to interpret the index as a descriptive

statistic, it is necessary to take into account that the small sample size in each classroom

makes it difficult for the correlation to reach levels of statistical significance. Given our

detailed knowledge of these classrooms as observers and staff developers, we tend to

view correlations of .40 and above as grounds for concern-that is, there are probably

untreated status problems.

References

Berger, J. B., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1966). Status characteristics and expecta-

tion states. In J. Berger & M. Zelditch, Jr. (Eds.), Sociological theories in progres

(Vol. 1, pp. 29-46). Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

Berger, J. B., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1972). Status characteristics and soci

interaction. American Sociological Review, 37, 241-255.

Berger, J. B., & Fisek, M. H. (1970). Consistent and inconsistent status characteristi

and the determination of power and prestige orders. Sociometry, 33, 287-30

118

This content downloaded from

130.102.13.62 on Sat, 06 Apr 2024 10:04:01 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Interaction in the Classroom

Berger, J. B., Rosenholtz, S. J., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1980). Status organizing processes.

Annual Review of Sociology, 6, 479-508.

Berger, J. B., Wagner, D. G., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1985). Introduction: Expectation states

theory: Review and assessment. In J. Berger & M. Zelditch, Jr. (Eds.), Status,

rewards, and influence (pp. 1-72). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development. (1989). Turning points: Preparing

American youth for the 21st century. Waldorf, MD: Author.

Cohen, E. G. (1982). Expectation states and interracial interaction in school settings.

Annual Review of Sociology, 8, 109-235.

Cohen, E. G. (1984). Talking and working together: Status, interaction and learning.

In P. Peterson, L. C. Wilkinson, & M. Hallinan (Eds.), Instructional groups in the

classroom: Organization and processes (pp. 171-187). Orlando, FL: Academic.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Status treatments for the classroom [Video]. New York: Teachers

College Press.

Cohen, E. G., Lockheed, M., & Lohman, M. (1976). The Center for Interracial Coopera-

tion: A field experiment. Sociology of Education, 49, 47-58.

Cohen, E. G., Lotan, R., & Catanzarite, L. (1988). Can expectations for competence

be treated in the classroomr In M. Webster, Jr., & M. Foschi (Eds.), Status general-

ization: New theory and research (pp. 28-54). Stanford: Stanford University

Press.

Cohen, E. G., Lotan, R., & Leechor, C. (1989). Can classrooms learn? Sociology of

Education, 62, 75-94.

Dembo, M., & McAuliffe, T. (1987). Effects of perceived ability and grade status on

social interaction and influence in cooperative groups. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 79, 415-423.

Eder, D. (1981). Ability grouping as a self-fulfilling prophecy: A micro-analysis of

teacher-student interaction. Sociology of Education, 54, 151-162.

Entwisle, D., & Webster, M., Jr. (1974). Raising children's expectations for their own

performance: A classroom application. In J. Berger, T. L. Conner, & M. H. Fisek

(Eds.), Expectation states theory: A theoretical research program (pp. 211-243).

Cambridge, MA: Winthrop.

Finn, J. D., & Cox, D. (1992). Participation and withdrawal among fourth-grade pupils.

American Educational Research Journal, 29, 141-162.

Gamoran, A. (1987). The stratification of high school learning opportunities. Sociology