Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Making Health Habitual - The Psychology of Habit-Formation' and General Practice

Making Health Habitual - The Psychology of Habit-Formation' and General Practice

Uploaded by

roseannalovejoyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 1st Grade Envision Math 2Document7 pages1st Grade Envision Math 2api-51171643550% (2)

- 2 Understanding Habit FormationDocument35 pages2 Understanding Habit FormationGousia SiddickNo ratings yet

- IB Prepared PsychologyDocument29 pagesIB Prepared PsychologyAlina Kubra100% (2)

- Health Education Behavior Models and Theories - PPTDocument55 pagesHealth Education Behavior Models and Theories - PPTJonah R. Merano93% (14)

- Milieu Therapy, Occupational TherapyDocument27 pagesMilieu Therapy, Occupational TherapyArya LekshmiNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion ModelDocument43 pagesHealth Promotion ModelJinsha Sibi86% (7)

- Florida Political Chronicle (Issue v.26 n.1 2018)Document104 pagesFlorida Political Chronicle (Issue v.26 n.1 2018)AlexNo ratings yet

- 664 FullDocument3 pages664 Fullmustafa kamalNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Model: Stephanie P. DayaganonDocument20 pagesTranstheoretical Model: Stephanie P. DayaganonSteph DayaganonNo ratings yet

- The Power of Habit: Transforming Your Life Through Small ChangesFrom EverandThe Power of Habit: Transforming Your Life Through Small ChangesNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Wellness: Bien-Être VétérinaireDocument2 pagesVeterinary Wellness: Bien-Être VétérinaireDaniel John ArboledaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Is An Integral Component of Nursing PracticeDocument4 pagesTeaching Is An Integral Component of Nursing PracticeMajorie ArimadoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Education and Counselling Behavioral Change: Trans Theoretical Model/StagesDocument3 pagesNutrition Education and Counselling Behavioral Change: Trans Theoretical Model/StagesMarielle Chua50% (2)

- Topic 7Document79 pagesTopic 7Muhd syazaniNo ratings yet

- NCM 105 FinalsDocument18 pagesNCM 105 Finalsyanna aNo ratings yet

- Habit Loop - Heuristics - Part 1Document30 pagesHabit Loop - Heuristics - Part 1Ali MohyNo ratings yet

- 4 Behavior ChangeDocument11 pages4 Behavior ChangePrincess Angie GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Report in NutritionDocument48 pagesGroup 4 Report in Nutritionfe espinosaNo ratings yet

- The Transtheoretical ModelDocument3 pagesThe Transtheoretical ModelReyhana Mohd YunusNo ratings yet

- Kanter - Behavioural ActivationDocument4 pagesKanter - Behavioural ActivationLorena MatosNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Behaviour Change: Evidence BriefingDocument6 pagesFacilitating Behaviour Change: Evidence BriefingBlack TsoiNo ratings yet

- Self CareDocument20 pagesSelf CareHamza IshtiaqNo ratings yet

- Teorias Modelos ComportamentoDocument40 pagesTeorias Modelos ComportamentomarciaNo ratings yet

- Shaping As A Behavior Modification TechniqueDocument10 pagesShaping As A Behavior Modification TechniquelarichmondNo ratings yet

- Nline Eight Management Ounseling Program For Ealthcare ProvidersDocument35 pagesNline Eight Management Ounseling Program For Ealthcare ProvidershermestriNo ratings yet

- Hope 1 Chapter 1 HandoutDocument3 pagesHope 1 Chapter 1 HandoutKim AereinNo ratings yet

- THE TRANSTHEORETICAl MODEL AND STAGES OF CHANGEDocument18 pagesTHE TRANSTHEORETICAl MODEL AND STAGES OF CHANGEDaniel Mesa100% (1)

- Thyroid Problem: Symptoms and Nursing Care PlanDocument7 pagesThyroid Problem: Symptoms and Nursing Care PlanAisa ShaneNo ratings yet

- Health EducationDocument33 pagesHealth EducationYousef KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Self Management PsychologyDocument14 pagesSelf Management PsychologymanukkNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Healthy BehavioursDocument5 pagesFactors Affecting Healthy BehavioursMeghna GaneshNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Activation: History, Evidence and Promise: Permissions ReprintsDocument4 pagesBehavioural Activation: History, Evidence and Promise: Permissions ReprintscaballeroNo ratings yet

- Theories Influence Counselors: OperantDocument6 pagesTheories Influence Counselors: OperantRUMA DANIEL HENDRYNo ratings yet

- The Health Belief ModelDocument13 pagesThe Health Belief Modelmiaedmonds554No ratings yet

- Behavioral Control of OvereatingDocument9 pagesBehavioral Control of OvereatingDario FriasNo ratings yet

- Lally & Gardner, 2013 - Promoting Habit Formation PDFDocument24 pagesLally & Gardner, 2013 - Promoting Habit Formation PDFLevitaSavitryNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (TTM) : Niken Nur Widyakusuma, M.SC., AptDocument20 pagesTranstheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (TTM) : Niken Nur Widyakusuma, M.SC., AptFarmasi Kelas A 2020No ratings yet

- Interventions To Promote Mobility - PDDDFDocument8 pagesInterventions To Promote Mobility - PDDDFFerdinand Sherwin MorataNo ratings yet

- B. Learning TheoriesDocument71 pagesB. Learning TheorieschristianarcigaixNo ratings yet

- Materi - Method and Approaches in HPDocument98 pagesMateri - Method and Approaches in HPdiniindahlestariNo ratings yet

- Theories of Behaviour ChangeDocument11 pagesTheories of Behaviour ChangeJusT TrendiNG StuffsNo ratings yet

- Manuscript - InterventionDocument3 pagesManuscript - InterventionbssalonzoNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Therapeutic MilieuDocument48 pagesPresentation On Therapeutic MilieuShailja SharmaNo ratings yet

- Penders Health Promotion ModelDocument2 pagesPenders Health Promotion ModelRIK HAROLD GATPANDANNo ratings yet

- NCP Impaired Physical MobilityDocument9 pagesNCP Impaired Physical MobilityChristian Apelo SerquillosNo ratings yet

- Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change - Background and Intervention DevelopmentDocument10 pagesIntegrated Theory of Health Behavior Change - Background and Intervention Developmentvero060112.vcNo ratings yet

- Nola J. PenderDocument5 pagesNola J. PenderSofia Marie GalendezNo ratings yet

- Motivation and Behavioral ChangeDocument14 pagesMotivation and Behavioral ChangejaninesalvacionNo ratings yet

- Module B - Lesson 5Document17 pagesModule B - Lesson 5Melanie CortezNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Theory Model - Prochaska - WikipediaDocument10 pagesTranstheoretical Theory Model - Prochaska - WikipediaAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- 12 Behavioristic Approach IUP Basic InterventionDocument18 pages12 Behavioristic Approach IUP Basic InterventionTSURAYA MUTIARALARASHATINo ratings yet

- M5 Gawain 2Document3 pagesM5 Gawain 2Precy Joy TrimidalNo ratings yet

- Food and Mood: Just-in-Time Support For Emotional EatingDocument6 pagesFood and Mood: Just-in-Time Support For Emotional EatingJho AlvaNo ratings yet

- TechniqueDocument2 pagesTechniqueSmitanjali ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Community Health NursingDocument18 pagesCommunity Health NursingCharmagne Joci EpantoNo ratings yet

- Behavioral and Psychosocial Interventions in Diabetes - A Conceptual ReviewDocument8 pagesBehavioral and Psychosocial Interventions in Diabetes - A Conceptual Reviewannezero123No ratings yet

- (R) Nelson JB (2017) - Mindful Eating - The Art of Presence While You EatDocument4 pages(R) Nelson JB (2017) - Mindful Eating - The Art of Presence While You EatAnonymous CuPAgQQNo ratings yet

- Counseling PDFDocument23 pagesCounseling PDFAhmed JabbarNo ratings yet

- UNIT - 5 - Behavioural TherapyDocument42 pagesUNIT - 5 - Behavioural Therapygargchiya97No ratings yet

- Nola PenderDocument9 pagesNola PenderAndrea YangNo ratings yet

- Social MKTG PPT 3Document17 pagesSocial MKTG PPT 3abdelamuzemil8No ratings yet

- Audit of Mining CompaniesDocument15 pagesAudit of Mining CompaniesACNo ratings yet

- 2021 PHC - Field Officers Manual - Final - 15.04.2021Document323 pages2021 PHC - Field Officers Manual - Final - 15.04.2021Enoch FavouredNo ratings yet

- Gs ManualDocument27 pagesGs ManualfauziNo ratings yet

- Matiltan HPP (Vol-II A) Specs NTDCDocument258 pagesMatiltan HPP (Vol-II A) Specs NTDCsami ul haqNo ratings yet

- C++ Programming With Visual Studio CodeDocument8 pagesC++ Programming With Visual Studio CodeADJANOHOUN jeanNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Management in ChinaDocument53 pagesLeadership and Management in ChinaDeriam ChirinosNo ratings yet

- Paper 29. Water Quality For AgricultureDocument243 pagesPaper 29. Water Quality For AgricultureDavid Casanueva CapocchiNo ratings yet

- SAS Blank Monitoring Report 7Document16 pagesSAS Blank Monitoring Report 7Rodjan Moscoso100% (1)

- Reviewer General Physics 1Document1 pageReviewer General Physics 1Asdf GhjNo ratings yet

- Gurdjieff - Learning & UnderstandingDocument13 pagesGurdjieff - Learning & UnderstandingPlanet Karatas100% (3)

- Ied CH-LPG & HCF MCQ RevDocument4 pagesIed CH-LPG & HCF MCQ Revragingcaverock696No ratings yet

- Hilgard ErnestDocument29 pagesHilgard ErnestPhuong Anh NguyenNo ratings yet

- MY23 Sportage PHEV ENGDocument5 pagesMY23 Sportage PHEV ENGSteve MastropoleNo ratings yet

- 4l60e Manual Shift ConversionDocument10 pages4l60e Manual Shift ConversionSalvador PinedaNo ratings yet

- Design Process - BhavyaaDocument47 pagesDesign Process - Bhavyaasahay designNo ratings yet

- Edu 105 H3Document3 pagesEdu 105 H3Michaella DometitaNo ratings yet

- Installation and User's Guide: IBM Tivoli Storage Manager For Windows Backup-Archive ClientsDocument800 pagesInstallation and User's Guide: IBM Tivoli Storage Manager For Windows Backup-Archive ClientsJavier GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Gde GC Consumables MasterDocument36 pagesGde GC Consumables MastersatishNo ratings yet

- e-STUDIO 4540C PDFDocument282 pagese-STUDIO 4540C PDFDariOlivaresNo ratings yet

- Cray Valley GuideDocument16 pagesCray Valley GuideAlejandro JassoNo ratings yet

- Stress ManagementDocument58 pagesStress ManagementDhAiRyA ArOrANo ratings yet

- Kundera - Music and MemoryDocument2 pagesKundera - Music and MemorypicsafingNo ratings yet

- Electrical Circuit 2 - Updated Dec 8Document24 pagesElectrical Circuit 2 - Updated Dec 8hadil hawillaNo ratings yet

- Serveraid M5014/M5015 Sas/Sata Controllers: User'S GuideDocument92 pagesServeraid M5014/M5015 Sas/Sata Controllers: User'S GuideAntonNo ratings yet

- Indian Writing in English (Novel) Colonial, Post Colonial & Diaspora - 21784541 - 2024 - 04!13!11 - 41Document53 pagesIndian Writing in English (Novel) Colonial, Post Colonial & Diaspora - 21784541 - 2024 - 04!13!11 - 41Rajni Ravi DevNo ratings yet

- AssertivenessDocument97 pagesAssertivenessHemantNo ratings yet

- Surveying and MeasurementDocument51 pagesSurveying and MeasurementJireh GraceNo ratings yet

Making Health Habitual - The Psychology of Habit-Formation' and General Practice

Making Health Habitual - The Psychology of Habit-Formation' and General Practice

Uploaded by

roseannalovejoyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Making Health Habitual - The Psychology of Habit-Formation' and General Practice

Making Health Habitual - The Psychology of Habit-Formation' and General Practice

Uploaded by

roseannalovejoyCopyright:

Available Formats

Debate & Analysis

Making health habitual:

the psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice

MAKING HEALTH HABITUAL cues that have been associated with their 10 simple diet and activity behaviours and

The Secretary of State recently proposed performance:5,6 for example, automatically encouraging context-dependent repetition,

that the NHS: washing hands (action) after using the toilet or a no-treatment waiting list control. After

(contextual cue), or putting on a seatbelt 8 weeks, the intervention group had lost

‘... take every opportunity to prevent poor (action) after getting into the car (contextual 2 kg compared with 0.4 kg in the control

health and promote healthy living by making cue). Decades of psychological research group. At 32 weeks, completers in the

the most of healthcare professionals’ consistently show that mere repetition of intervention group had lost an average of

contact with individual patients.’ 1 a simple action in a consistent context 3.8 kg.14 Qualitative interview data indicated

leads, through associative learning, to the that automaticity had developed: behaviours

Patients trust health professionals as action being activated upon subsequent became ‘second nature’, ‘worming their

a source of advice on ‘lifestyle’ (that is, exposure to those contextual cues (that is, way into your brain’ so that participants

behaviour) change, and brief opportunistic habitually).7–9 Once initiation of the action is ‘felt quite strange’ if they did not do

advice can be effective.2 However, many ‘transferred’ to external cues, dependence them.10 Actions that were initially difficult

health professionals shy away from giving on conscious attention or motivational to stick to became easier to maintain. A

advice on modifying behaviour because they processes is reduced.10 Therefore habits randomised controlled trial is underway to

find traditional behaviour change strategies are likely to persist even after conscious test the efficacy of this intervention where

time-consuming to explain and difficult for motivation or interest dissipates.11 Habits delivered in a primary care setting to a

the patient to implement.2 Furthermore, are also cognitively efficient, because larger sample, over a 24-month follow-up

even when patients successfully initiate the the automation of common actions frees period.16 Nonetheless, these early results

recommended changes, the gains are often mental resources for other tasks. indicate that habit-forming processes

transient3 because few of the traditional A growing literature demonstrates the transfer to the everyday environment, and

behaviour change strategies have built-in relevance of habit-formation principles suggest that habit-formation advice offers

mechanisms for maintenance. to health.12,13 Participants in one study an innovative technique for promoting long-

Brief advice is usually based on repeated a self-chosen health-promoting term behaviour change.13

advising patients on what to change and behaviour (for example, eat fruit, go for a

why (for example, reducing saturated fat walk) in response to a single, once-daily MAKING HEALTHY HABITS

intake to reduce the risk of heart attack). cue in their own environment (such as, after We suggest that professionals could

Psychologically, such advice is designed to breakfast). Daily ratings of the subjective consider providing habit-formation advice

engage conscious deliberative motivational automaticity of the behaviour (that is, habit as a way to promote long-term behaviour

processes, which Kahneman terms ‘slow’ strength) showed an asymptotic increase, change among patients. Habit-formation

or ‘System 2’ processes.4 However, the with an initial acceleration that slowed to a advice is ultimately simple — repeat an

effects are typically short-lived because plateau after an average of 66 days.9 Missing action consistently in the same context.12

motivation and attention wane. Brief advice the occasional opportunity to perform the The habit formation attempt begins at the

on how to change, engaging automatic behaviour did not seriously impair the habit ‘initiation phase’, during which the new

(‘System 1’) processes, may offer a valuable formation process: automaticity gains soon behaviour and the context in which it will be

alternative with potential for long-term resumed after one missed performance.9 done are selected. Automaticity develops

impact. Automaticity strength peaked more quickly in the subsequent ‘learning phase’, during

Opportunistic health behaviour advice for simple actions (for example, drinking which the behaviour is repeated in the

must be easy for health professionals to give water) than for more elaborate routines (for chosen context to strengthen the context-

and easy for patients to implement to fit into example, doing 50 sit-ups). behaviour association (here a simple

routine health care. We propose that simple Habit-formation advice, paired with ticksheet for self-monitoring performance

advice on how to make healthy actions into a ‘small changes’ approach, has been may help; Box 1). Habit-formation

habits — externally-triggered automatic tested as a behaviour change strategy.14,15 culminates in the ‘stability phase’, at which

responses to frequently encountered In one study, volunteers wanting to lose the habit has formed and its strength has

contexts — offers a useful option in the weight were randomised to a habit-based plateaued, so that it persists over time with

behaviour change toolkit. Advice for creating intervention, based on a brief leaflet listing minimal effort or deliberation.

habits is easy for clinicians to deliver and

easy for patients to implement: repeat a

chosen behaviour in the same context, until

it becomes automatic and effortless.

“Advice for creating habits is easy for clinicians to

HABIT FORMATION AND HEALTH deliver and easy for patients to implement: repeat

While often used as a synonym for frequent

or customary behaviour in everyday a chosen behaviour in the same context, until it

parlance, within psychology, ‘habits’ are becomes automatic and effortless.”

defined as actions that are triggered

automatically in response to contextual

664 British Journal of General Practice, December 2012

and settings to maintain interest (trying

different fruits with or between different

“... typical [behaviour change] advice ... emphasises meals). Variation may stave off boredom,

variation in behaviours and settings ... . Variation may but is effortful and depends on maintaining

stave off boredom, but is effortful and ... incompatible motivation, and is incompatible with

development of automaticity.6

with development of automaticity.” Patients should choose the target

behaviour themselves. Progress towards a

self-determined behavioural goal supports

patients’ sense of autonomy and sustains

Initiation requires the patient to be located within an existing daily routine (for interest,17 and there is evidence that a

sufficiently motivated to begin a habit- example, ‘when I go on my lunch break’) behaviour change selected on the basis of

formation attempt, but many patients would provides a convenient and stable starting its personal value, rather than to satisfy

like to eat healthier diets or take more point.10 external demands such as physicians’

exercise, for example, if doing so were Keeping going during the learning recommendations, is an easier habit

easy. Patients must choose an appropriate phase is crucial. The idea of repeating a target.18 Patients need to select a new

context in which to perform the action. The single specific action (for example, eating behaviour (for example, eat an apple) rather

‘context’ can be any cue, for example, an a banana) in a consistent context (with than give up an existing behaviour (do not

event (‘when I get to work’) or a time of cereal at breakfast) is very different from eat fried snacks) because it is not possible

day (‘after breakfast’), that is sufficiently typical advice given to people trying to to form a habit for not doing something. The

salient in daily life that it is encountered and take up new healthy behaviours, which automaticity of habit means that breaking

detected frequently and consistently. A cue often emphasises variation in behaviours existing habits requires different and

altogether more effortful strategies than

making new habits.12

Patients should be encouraged to aim for

small and manageable behaviour changes,

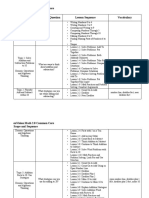

Box 1. A tool for patients because failure can be discouraging. A

Make a new healthy habit sedentary person, for example, would be

1. Decide on a goal that you would like to achieve for your health. more appropriately advised to walk one or

2. Choose a simple action that will get you towards your goal which you can do on a daily basis. two stops more before getting on the bus

3. Plan when and where you will do your chosen action. Be consistent: choose a time and place that you

than to walk the entire route — at least

encounter every day of the week.

4. Every time you encounter that time and place, do the action. for their first habit goal. Small changes

5. It will get easier with time, and within 10 weeks you should find you are doing it automatically without can benefit health: slight adjustments to

even having to think about it. dietary intake can aid long-term weight

6. Congratulations, you’ve made a healthy habit!

management,19 and small amounts of light

My goal (e.g. ‘to eat more fruit and vegetables’) _________________________________________________ physical activity are more beneficial than

none.20 Moreover, simpler actions become

My plan (e.g. ‘after I have lunch at home I will have a piece of fruit’) habitual more quickly.9 Additionally,

(When and where) ___________________________ I will ___________________________ behaviour change achievements, however

Some people find it helpful to keep a record while they are forming a new habit. This daily tick-sheet can be small, can increase self-efficacy, which

used until your new habit becomes automatic. You can rate how automatic it feels at the end of each week, can in turn stimulate pursuit of further

to watch it getting easier. changes.21 Forming one ‘small’ healthy

Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 6 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 habit may thereby increase self-confidence

for working towards other health-promoting

Monday

habits.

Tuesday

Unrealistic expectations of the duration

Wednesday of the habit formation process can lead

Thursday the patient to give up during the learning

Friday phase. Some patients may have heard that

Saturday

habits take 21 days to form. This myth

appears to have originated from anecdotal

Sunday

evidence of patients who had received

Done on plastic surgery treatment and typically

>5 days, adjusted psychologically to their new

yes or no

appearance within 21 days.22 More relevant

How research found that automaticity plateaued

automatic on average around 66 days after the first

does it feel?

daily performance,9 although there was

Rate from

considerable variation across participants

1 (not at all)

to10

and behaviours. Therefore, it may be helpful

(completely) to tell patients to expect habit formation

(based on daily repetition) to take around

British Journal of General Practice, December 2012 665

ADDRESS FOR CORRESPONDENCE REFERENCES

Benjamin Gardner 1. Lansley A. Response to NHS Future Forum’s 12. Lally P, Gardner B. Promoting habit

Health Behaviour Research Centre, Department of second report. London: Department of Health, formation. Health Psychol Rev . In press: DOI:

Epidemiology and Public Health, University College 2012. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/ 10.1080/17437199.2011.603640.

London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/ 13. Rothman AJ, Sheeran P, Wood W. Reflective

dh_132088.pdf (accessed 16 Oct 2012). and automatic processes in the initiation and

E-mail: b.gardnersood@ucl.ac.uk

2. Lawlor DA, Keen S, Neal RD. Can general maintenance of dietary change. Ann Behav Med

practitioners influence the nation’s health 2009; 38(Suppl1): S4–17.

through a population approach to provision of 14. Lally P, Chipperfield A, Wardle J. Healthy habits:

10 weeks. Our experience is that people lifestyle advice? Br J Gen Pract 2000; 50(455): Efficacy of simple advice on weight control based

are reassured to learn that doing the 455–459. on a habit-formation model. Int J Obes 2008;

behaviour gets progressively easier; so they 3. Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, 32(4): 700–707.

Stunkard AJ, et al. Long-term maintenance of 15. McGowan L, Cooke LJ, Croker H, et al. Habit-

only have to maintain their motivation until weight loss: current status. Health Psychol 2000; formation as a novel theoretical framework for

the habit forms. Working effortfully on a 19(Suppl1): 5–S16. dietary change in pre-schoolers. Psychol Health

new behaviour for 2–3 months may be an 4. Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and 2012; 27(Suppl1): 89.

attractive offer if it has a chance of making choice. Am Psychol 2003; 58(9): 697–720. 16. Beeken RJ, Croker H, Morris S, et al. Study

the behaviour become ‘second nature’. 5. Neal DT, Wood W, Labrecque JS, Lally P. How protocol for the 10 Top Tips (10TT) Trial:

do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual Randomised controlled trial of habit-based

CONCLUSION triggers of habits in daily life. J Exp Soc Psychol advice for weight control in general practice.

2012; 48: 492–498. BMC Public Health 2012; 12(1): 667.

Psychological theory and evidence

6. Wood W, Neal DT. A new look at habits and the 17. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The support of autonomy and

around habit-formation generates habit-goal interface. Psychol Rev 2007; 114(4): the control of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;

recommendations for simple and 843–863. 53(6): 1024–1037.

sustainable behaviour change advice. We 7. Bayley PJ, Frascino JC, Squire LR. Robust 18. Gardner B, Lally P. Does intrinsic motivation

acknowledge that health professionals do habit learning in the absence of awareness strengthen physical activity habit? Modeling

not always find it appropriate to offer lifestyle and independent of the medial temporal lobe. relationships between self-determination, past

Nature 2005; 436(7050): 550–553. behaviour, and habit strength. J Behav Med

counselling to patients: some patients can

[Epub ahead of print].

become annoyed when advised to change 8. Hull CL. Principles of behavior: an introduction

to behavior theory. New York, NY: Appleton- 19. Hill JO. Can a small-changes approach help

their behaviour, and this reaction can Century-Crofts, 1943. address the obesity epidemic? A report of the

threaten patients’ trust in and satisfaction Joint Task Force of the American Society for

9. Lally P, van Jaarsveld CHM, Potts HWW, Wardle

with the doctor–patient relationship.2 J. How are habits formed: modelling habit

Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and

However, in settings where professionals International Food Information Council. Am J

formation in the real world. Euro J Soc Psychol

Clin Nutr 2009; 89(2): 477–484.

feel able to offer behaviour advice, we 2010; 40: 998–1009.

20. Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health

suggest that they consider providing 10. Lally P, Wardle J, Gardner B. Experiences of

benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Can

guidance on habit-formation. Habit- habit formation: a qualitative study. Psychol

Health Med 2011; 16(4): 484–489. Med J 2006; 174(6): 801–809.

formation advice can be delivered briefly, it 21. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic

11. Gardner B, de Bruijn GJ, Lally P. A systematic

is simple for the patient to implement, and it perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52: 1–26.

review and meta-analysis of applications of the

has realistic potential for long-term impact. Self-Report Habit Index to nutrition and physical 22. Maltz M. Psycho-cybernetics. New York, NY:

It offers health professionals a useful tool activity behaviours. Ann Behav Med 2011; 42(2): Prentice Hall, 1960.

for incorporating evidence-based health 174–187.

promotion into encounters with patients. A

sample tool for health professionals to use

with patients to encourage habit formation

is provided in Box 1.

Benjamin Gardner,

Lecturer in Health Psychology, Health Behaviour

Research Centre, Department of Epidemiology and

Public Health, University College London, London.

Phillippa Lally,

ESRC Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Health

Behaviour Research Centre, Department of

Epidemiology and Public Health, University College

London, London.

Jane Wardle,

Professor of Clinical Psychology, Health Behaviour

Research Centre, Department of Epidemiology and

Public Health, University College London, London.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

DOI: 10.3399/bjgp12X659466

666 British Journal of General Practice, December 2012

You might also like

- 1st Grade Envision Math 2Document7 pages1st Grade Envision Math 2api-51171643550% (2)

- 2 Understanding Habit FormationDocument35 pages2 Understanding Habit FormationGousia SiddickNo ratings yet

- IB Prepared PsychologyDocument29 pagesIB Prepared PsychologyAlina Kubra100% (2)

- Health Education Behavior Models and Theories - PPTDocument55 pagesHealth Education Behavior Models and Theories - PPTJonah R. Merano93% (14)

- Milieu Therapy, Occupational TherapyDocument27 pagesMilieu Therapy, Occupational TherapyArya LekshmiNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion ModelDocument43 pagesHealth Promotion ModelJinsha Sibi86% (7)

- Florida Political Chronicle (Issue v.26 n.1 2018)Document104 pagesFlorida Political Chronicle (Issue v.26 n.1 2018)AlexNo ratings yet

- 664 FullDocument3 pages664 Fullmustafa kamalNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Model: Stephanie P. DayaganonDocument20 pagesTranstheoretical Model: Stephanie P. DayaganonSteph DayaganonNo ratings yet

- The Power of Habit: Transforming Your Life Through Small ChangesFrom EverandThe Power of Habit: Transforming Your Life Through Small ChangesNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Wellness: Bien-Être VétérinaireDocument2 pagesVeterinary Wellness: Bien-Être VétérinaireDaniel John ArboledaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Is An Integral Component of Nursing PracticeDocument4 pagesTeaching Is An Integral Component of Nursing PracticeMajorie ArimadoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Education and Counselling Behavioral Change: Trans Theoretical Model/StagesDocument3 pagesNutrition Education and Counselling Behavioral Change: Trans Theoretical Model/StagesMarielle Chua50% (2)

- Topic 7Document79 pagesTopic 7Muhd syazaniNo ratings yet

- NCM 105 FinalsDocument18 pagesNCM 105 Finalsyanna aNo ratings yet

- Habit Loop - Heuristics - Part 1Document30 pagesHabit Loop - Heuristics - Part 1Ali MohyNo ratings yet

- 4 Behavior ChangeDocument11 pages4 Behavior ChangePrincess Angie GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Report in NutritionDocument48 pagesGroup 4 Report in Nutritionfe espinosaNo ratings yet

- The Transtheoretical ModelDocument3 pagesThe Transtheoretical ModelReyhana Mohd YunusNo ratings yet

- Kanter - Behavioural ActivationDocument4 pagesKanter - Behavioural ActivationLorena MatosNo ratings yet

- Facilitating Behaviour Change: Evidence BriefingDocument6 pagesFacilitating Behaviour Change: Evidence BriefingBlack TsoiNo ratings yet

- Self CareDocument20 pagesSelf CareHamza IshtiaqNo ratings yet

- Teorias Modelos ComportamentoDocument40 pagesTeorias Modelos ComportamentomarciaNo ratings yet

- Shaping As A Behavior Modification TechniqueDocument10 pagesShaping As A Behavior Modification TechniquelarichmondNo ratings yet

- Nline Eight Management Ounseling Program For Ealthcare ProvidersDocument35 pagesNline Eight Management Ounseling Program For Ealthcare ProvidershermestriNo ratings yet

- Hope 1 Chapter 1 HandoutDocument3 pagesHope 1 Chapter 1 HandoutKim AereinNo ratings yet

- THE TRANSTHEORETICAl MODEL AND STAGES OF CHANGEDocument18 pagesTHE TRANSTHEORETICAl MODEL AND STAGES OF CHANGEDaniel Mesa100% (1)

- Thyroid Problem: Symptoms and Nursing Care PlanDocument7 pagesThyroid Problem: Symptoms and Nursing Care PlanAisa ShaneNo ratings yet

- Health EducationDocument33 pagesHealth EducationYousef KhalifaNo ratings yet

- Self Management PsychologyDocument14 pagesSelf Management PsychologymanukkNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Healthy BehavioursDocument5 pagesFactors Affecting Healthy BehavioursMeghna GaneshNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Activation: History, Evidence and Promise: Permissions ReprintsDocument4 pagesBehavioural Activation: History, Evidence and Promise: Permissions ReprintscaballeroNo ratings yet

- Theories Influence Counselors: OperantDocument6 pagesTheories Influence Counselors: OperantRUMA DANIEL HENDRYNo ratings yet

- The Health Belief ModelDocument13 pagesThe Health Belief Modelmiaedmonds554No ratings yet

- Behavioral Control of OvereatingDocument9 pagesBehavioral Control of OvereatingDario FriasNo ratings yet

- Lally & Gardner, 2013 - Promoting Habit Formation PDFDocument24 pagesLally & Gardner, 2013 - Promoting Habit Formation PDFLevitaSavitryNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (TTM) : Niken Nur Widyakusuma, M.SC., AptDocument20 pagesTranstheoretical Model of Health Behavior Change (TTM) : Niken Nur Widyakusuma, M.SC., AptFarmasi Kelas A 2020No ratings yet

- Interventions To Promote Mobility - PDDDFDocument8 pagesInterventions To Promote Mobility - PDDDFFerdinand Sherwin MorataNo ratings yet

- B. Learning TheoriesDocument71 pagesB. Learning TheorieschristianarcigaixNo ratings yet

- Materi - Method and Approaches in HPDocument98 pagesMateri - Method and Approaches in HPdiniindahlestariNo ratings yet

- Theories of Behaviour ChangeDocument11 pagesTheories of Behaviour ChangeJusT TrendiNG StuffsNo ratings yet

- Manuscript - InterventionDocument3 pagesManuscript - InterventionbssalonzoNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Therapeutic MilieuDocument48 pagesPresentation On Therapeutic MilieuShailja SharmaNo ratings yet

- Penders Health Promotion ModelDocument2 pagesPenders Health Promotion ModelRIK HAROLD GATPANDANNo ratings yet

- NCP Impaired Physical MobilityDocument9 pagesNCP Impaired Physical MobilityChristian Apelo SerquillosNo ratings yet

- Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change - Background and Intervention DevelopmentDocument10 pagesIntegrated Theory of Health Behavior Change - Background and Intervention Developmentvero060112.vcNo ratings yet

- Nola J. PenderDocument5 pagesNola J. PenderSofia Marie GalendezNo ratings yet

- Motivation and Behavioral ChangeDocument14 pagesMotivation and Behavioral ChangejaninesalvacionNo ratings yet

- Module B - Lesson 5Document17 pagesModule B - Lesson 5Melanie CortezNo ratings yet

- Transtheoretical Theory Model - Prochaska - WikipediaDocument10 pagesTranstheoretical Theory Model - Prochaska - WikipediaAlbert Muya MurayaNo ratings yet

- 12 Behavioristic Approach IUP Basic InterventionDocument18 pages12 Behavioristic Approach IUP Basic InterventionTSURAYA MUTIARALARASHATINo ratings yet

- M5 Gawain 2Document3 pagesM5 Gawain 2Precy Joy TrimidalNo ratings yet

- Food and Mood: Just-in-Time Support For Emotional EatingDocument6 pagesFood and Mood: Just-in-Time Support For Emotional EatingJho AlvaNo ratings yet

- TechniqueDocument2 pagesTechniqueSmitanjali ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- Community Health NursingDocument18 pagesCommunity Health NursingCharmagne Joci EpantoNo ratings yet

- Behavioral and Psychosocial Interventions in Diabetes - A Conceptual ReviewDocument8 pagesBehavioral and Psychosocial Interventions in Diabetes - A Conceptual Reviewannezero123No ratings yet

- (R) Nelson JB (2017) - Mindful Eating - The Art of Presence While You EatDocument4 pages(R) Nelson JB (2017) - Mindful Eating - The Art of Presence While You EatAnonymous CuPAgQQNo ratings yet

- Counseling PDFDocument23 pagesCounseling PDFAhmed JabbarNo ratings yet

- UNIT - 5 - Behavioural TherapyDocument42 pagesUNIT - 5 - Behavioural Therapygargchiya97No ratings yet

- Nola PenderDocument9 pagesNola PenderAndrea YangNo ratings yet

- Social MKTG PPT 3Document17 pagesSocial MKTG PPT 3abdelamuzemil8No ratings yet

- Audit of Mining CompaniesDocument15 pagesAudit of Mining CompaniesACNo ratings yet

- 2021 PHC - Field Officers Manual - Final - 15.04.2021Document323 pages2021 PHC - Field Officers Manual - Final - 15.04.2021Enoch FavouredNo ratings yet

- Gs ManualDocument27 pagesGs ManualfauziNo ratings yet

- Matiltan HPP (Vol-II A) Specs NTDCDocument258 pagesMatiltan HPP (Vol-II A) Specs NTDCsami ul haqNo ratings yet

- C++ Programming With Visual Studio CodeDocument8 pagesC++ Programming With Visual Studio CodeADJANOHOUN jeanNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Management in ChinaDocument53 pagesLeadership and Management in ChinaDeriam ChirinosNo ratings yet

- Paper 29. Water Quality For AgricultureDocument243 pagesPaper 29. Water Quality For AgricultureDavid Casanueva CapocchiNo ratings yet

- SAS Blank Monitoring Report 7Document16 pagesSAS Blank Monitoring Report 7Rodjan Moscoso100% (1)

- Reviewer General Physics 1Document1 pageReviewer General Physics 1Asdf GhjNo ratings yet

- Gurdjieff - Learning & UnderstandingDocument13 pagesGurdjieff - Learning & UnderstandingPlanet Karatas100% (3)

- Ied CH-LPG & HCF MCQ RevDocument4 pagesIed CH-LPG & HCF MCQ Revragingcaverock696No ratings yet

- Hilgard ErnestDocument29 pagesHilgard ErnestPhuong Anh NguyenNo ratings yet

- MY23 Sportage PHEV ENGDocument5 pagesMY23 Sportage PHEV ENGSteve MastropoleNo ratings yet

- 4l60e Manual Shift ConversionDocument10 pages4l60e Manual Shift ConversionSalvador PinedaNo ratings yet

- Design Process - BhavyaaDocument47 pagesDesign Process - Bhavyaasahay designNo ratings yet

- Edu 105 H3Document3 pagesEdu 105 H3Michaella DometitaNo ratings yet

- Installation and User's Guide: IBM Tivoli Storage Manager For Windows Backup-Archive ClientsDocument800 pagesInstallation and User's Guide: IBM Tivoli Storage Manager For Windows Backup-Archive ClientsJavier GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Gde GC Consumables MasterDocument36 pagesGde GC Consumables MastersatishNo ratings yet

- e-STUDIO 4540C PDFDocument282 pagese-STUDIO 4540C PDFDariOlivaresNo ratings yet

- Cray Valley GuideDocument16 pagesCray Valley GuideAlejandro JassoNo ratings yet

- Stress ManagementDocument58 pagesStress ManagementDhAiRyA ArOrANo ratings yet

- Kundera - Music and MemoryDocument2 pagesKundera - Music and MemorypicsafingNo ratings yet

- Electrical Circuit 2 - Updated Dec 8Document24 pagesElectrical Circuit 2 - Updated Dec 8hadil hawillaNo ratings yet

- Serveraid M5014/M5015 Sas/Sata Controllers: User'S GuideDocument92 pagesServeraid M5014/M5015 Sas/Sata Controllers: User'S GuideAntonNo ratings yet

- Indian Writing in English (Novel) Colonial, Post Colonial & Diaspora - 21784541 - 2024 - 04!13!11 - 41Document53 pagesIndian Writing in English (Novel) Colonial, Post Colonial & Diaspora - 21784541 - 2024 - 04!13!11 - 41Rajni Ravi DevNo ratings yet

- AssertivenessDocument97 pagesAssertivenessHemantNo ratings yet

- Surveying and MeasurementDocument51 pagesSurveying and MeasurementJireh GraceNo ratings yet