Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Technology-Based Psychosocial Interventions For People With BPD

Technology-Based Psychosocial Interventions For People With BPD

Uploaded by

Anjan Kumar DhakalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Technology-Based Psychosocial Interventions For People With BPD

Technology-Based Psychosocial Interventions For People With BPD

Uploaded by

Anjan Kumar DhakalCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 Received: May 12, 2020

Accepted: September 2, 2020

DOI: 10.1159/000511349 Published online: November 9, 2020

Technology-Based Psychosocial Interventions

for People with Borderline Personality Disorder:

A Scoping Review of the Literature

Álvaro Frías a, b Laia Solves a, b Sara Navarro a, b Carol Palma a, b

Núria Farriols a, b Ferrán Aliaga a, b Mònica Hernández b Meritxell Antón b

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

Aloma Riera b

a Facultat de Psicologia, Ciències de l’Educació i de l’Esport Blanquerna, University of Ramon-Llull, Barcelona, Spain;

b Adult

Outpatient Mental Health Center, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Hospital of Mataró, Mataró, Spain

Keywords studies (7/15) were referred to as dialectical behavior thera-

Borderline personality disorder · Software · Clinical research · py-based software; most studies (13/15) were focused on the

Technology-based interventions · Psychosocial treatments initial stage of the clinical research cycle (feasibility/accep-

tance/usability testing), reporting good results at this point;

more than one-third of the studies (6/15) tested mobile

Abstract apps; there is emerging evidence for Internet-based inter-

Evidence-based psychosocial interventions for borderline ventions and real-time fMRI biofeedback but only little evi-

personality disorder (BPD) still face multiple challenges re- dence for mHealth interventions, virtual and augmented re-

garding treatment accessibility, adherence, duration, and ality, and computer-based interventions; there was no com-

economic costs. Over the last decade, technology has ad- putational technology-based clinical research; and there

dressed these concerns from different disciplines. The cur- was no satisfaction/preference, security/safety, or efficiency

rent scoping review aimed to delineate novel and ongoing testing for any software. Taken together, the results suggest

clinical research on technology-based psychosocial inter- that there is a growing but still incipient amount of technol-

ventions for patients with BPD. Online databases (PubMed, ogy-based psychosocial interventions for BPD supported by

Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and some kind of clinical evidence. The limitations and directions

Google Scholar) were searched up to June 2020. Technolo- for future research are discussed. © 2020 S. Karger AG, Basel

gy-based psychosocial treatments included innovative com-

munication (eHealth) and computational (e.g., artificial intel-

ligence), computing (e.g., computer-based), or medical (e.g.,

functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI]) software. Introduction

Clinical research encompassed any testing stage (e.g., feasi-

bility, efficacy). Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. The Rationale

main findings were the following: almost two-thirds of the Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is character-

studies (9/15) tested software explicitly conceived as adjunc- ized by pervasive affective, interpersonal, identity, cogni-

tive interventions to conventional therapy; nearly half of the tive, and behavioral instability as well as high rates of sui-

karger@karger.com © 2020 S. Karger AG, Basel Álvaro Frías

www.karger.com/psp Adult Outpatient Mental Health Center

Consorci Sanitari del Maresme

Cirera Road 320, ES–08304 Mataró (Spain)

afrias @ csdm.cat

cidal and self-harm behaviors [1]. Its prevalence in the these patients, either as an adjunctive or as an alternative

general population is estimated to range from 1.2 to 2% innovative therapy, can make therapy more accessible,

[2]. Those affected are often severely impaired in their complete, flexible, comfortable, accurate, and ultimately

social and professional functioning [3]. BPD also consti- cost-effective. Similar to the aforementioned mental dis-

tutes a high economic burden on society [4]. orders, current clinical research on technology-based

Several psychosocial treatments for BPD have been de- psychosocial treatments for BPD is also providing grow-

veloped and positively tested, including dialectical behav- ing but initial clinical evidence [8]. At present, the num-

ior therapy (DBT), schema therapy, mentalization-based ber of ongoing projects warrants a review to establish an

therapy, and transference-focused psychotherapy [5, 6]. overall vision of this issue.

These treatments notably take a long time to administer,

requiring several years for completion. Some of these pa- Objectives

tients discontinue therapy in the beginning or abruptly There were no prior scoping reviews aimed at address-

[7]. Meanwhile, implementation and dissemination are ing technology-based psychosocial interventions for peo-

slow, and most patients with BPD do not receive these ple with BPD. Hence, the present paper sought to fill this

treatments. Within this context, technology-based psy- gap in the literature by performing an up-to-date review

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

chosocial interventions may be an adequate way to over- of those ongoing studies in BPD that tested any type of

come treatment barriers and limitations for people with technology (as described in the above section) through

BPD [8]. any stage of the clinical research cycle (from feasibility/

In general, current developments of healthcare tech- usability/acceptance to efficiency testing).

nology for mental health comprise a wide range of disci-

plines, including, but not limited to: (1) information and

Methods

communication technology or eHealth: Internet-based

treatments (website-based, virtual therapeutic communi- Information Sources

ties); mHealth (mobile app-based, wearable biosensor de- A literature search was carried out through the PubMed,

vices); telehealth (videoconferencing, email messages); Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and

(2) computing technology: computer-based; serious Google Scholar databases from inception to June 2020. The terms

employed included indexing terms (e.g., MeSH) and free texts:

games; virtual reality; eye-tracking; (3) computational (borderline personality) AND (ehealth OR mhealth OR mobile

technology: artificial intelligence; machine learning; deep app OR computer-based OR Internet-based OR technology OR

learning; and (4) medical technology: functional magnet- artificial intelligence OR biofeedback OR machine learning OR

ic resonance imaging (fMRI) [9–12]. The integration of virtual reality OR telehealth OR serious games OR wearable device

these types of technology into the current psychosocial OR eye-tracking OR digital OR big data OR fMRI).

treatments for mental disorders has increased rapidly Eligibility Criteria

over the last 10 years, with ongoing clinical research Studies were selected if they included the following three char-

mostly from initial stages of testing (feasibility/accep- acteristics: (1) participants: subjects with a main diagnosis of BPD

tance/usability studies) rather than from later stages (ef- confirmed by semi-structured clinical interviews; (2) interven-

ficacy/effectiveness studies). Except for the sound evi- tions: technology-based psychosocial treatments consisting of in-

novative communication (eHealth) and computational (e.g., arti-

dence on Internet-based interventions for depression and ficial intelligence), computing (e.g., computer-based), or medical

anxiety disorders [13], such clinical research is providing (e.g., fMRI) software; and (3) outcomes: findings from any stage of

promising but still not well-established clinical evidence the clinical research cycle (e.g., feasibility, efficacy, safety, satisfac-

for transdiagnostic psychiatric symptoms (e.g., suicidal tion, efficiency). Also, studies were to appear in a peer-reviewed

ideation) and common mental disorders (e.g., schizo- journal and to be accessible in the English language.

phrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, substance use Study Selection

disorders, anxiety disorders, major depression, posttrau- Detailed data of the study selection process are shown in Figure

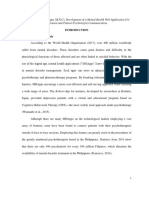

matic stress disorder, autism spectrum disorders, atten- 1. Thirty-six papers were initially collected, but at the end of the

tion deficit hyperactivity disorder) [14–16]. process 21 papers had been removed. Thus, 15 papers were in-

As mentioned above, technology-based psychosocial cluded in the current scoping review.

interventions may also be an optimized way to solve po- Data Items

tential problems associated with conventional face-to- Data from each of the selected papers was separately recruited,

face treatments in people with BPD [8]. The integration classified, and described according to:

of technology into the evidence-based treatments for

Technology-Based Psychosocial Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 255

Interventions for BPD DOI: 10.1159/000511349

Color version available online

Identification

Records identified through database Additional records identified through

searching other sources

(n = 39) (n = 0)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 36)

Screening

Records excluded (12):

Records screened 12 papers only related to diagnosis

(n = 36) and classification in borderline

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

personality disorder

Full-text articles excluded (9):

Eligibility

Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility 1 paper edited in German language

(n = 24) 1 paper only focused on content

validity

1 paper did not have patients’/users’

opinions

3 papers were theoretical

descriptions of the software

Studies included in 3 papers were related to somatic

Included

systematic review treatments

(n = 15)

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study selection.

(1) Type of technology-based psychosocial intervention: (a) In- research. For these reasons, a meta-analysis was not considered as

formation and communication technology: Internet-based (web- the best choice. Also, a systematic review was ruled out because this

site-based, virtual therapeutic communities); mHealth (mobile was a novel field of research. Accordingly, a scoping review was

app-based, wearable biosensor devices); telehealth (videoconfer- considered as the more appropriate approach.

encing, email messages). (b) Computer technology: virtual/aug- A mixed approach to synthesize and categorize the findings

mented reality; serious games; eye-tracking; computer-based. (In- was created based on the following classification methods: (1)

ternet-based and computer-based were separately classified be- technology readiness level [17]; (2) software testing research [18];

cause the former does not necessarily need to be installed on the and (3) evidence-based medicine [19]. This mixed approach was

computer. In addition, computer-based technologies were nor run considered better than one of them alone because it comprised dif-

via the Internet.) (c) Computational technology: artificial intelli- ferent aspects to take into account when analyzing each type of

gence; machine learning; deep learning. (d) Medical technology: clinical research from technology-, software-, and medicine-based

fMRI. standpoints altogether.

(2) Type of clinical research: (a) Feasibility/acceptance/usabil- The proposed mixed approach was called the research develop-

ity testing. (b) Efficacy/effectiveness testing. (c) Satisfaction/pref- mental level (RDL). Papers were scored according to the metrics

erence testing. (d) Security/safety testing. (e) Efficiency testing for each stage of the clinical research cycle listed in Table 1. The

(cost-effectiveness). total score may range between 0 and 20. Depending on the total

score, the RDL of each paper was classified as follows: 0–3 (imma-

Additional Analyses ture), 4–8 (emerging), 9–12 (promising), 13–16 (adequate), and

The included studies were thought to be too different in type of 17–20 (validated).

technology-based psychosocial intervention and type of clinical

256 Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 Frías/Solves/Navarro/Palma/Farriols/

DOI: 10.1159/000511349 Aliaga/Hernández/Antón/Riera

Table 1. Metrics for each stage of the clinical research cycle

Type of clinical research Points

Feasibility/usability/acceptance testing

Feasibility testing 1

Usability and/or acceptance testing 1

If based on single-case study 0

pilot study 0.5

multiple user groups 1

Efficacy/effectiveness testing

Randomized controlled trial 4

if multicenter 1

if active control treatment 1

Open trial 3

Satisfaction/preference testing valid for efficacy/effectiveness study 2

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

Safety/security testing valid for efficacy/effectiveness study 3

Efficiency testing cost-effectiveness analysis 5

Additional metric software testing in full or beta version 1

Data Collection and Classification Process [25]. All of them should be used as unguided self-man-

Studies were selected by the first two authors of the current pa-

per independently. At the end of the selection process, both re- agement interventions. Three were DBT-based, to be de-

searchers had gathered the same 15 papers. Regarding the pro- livered as an adjunctive tool to conventional DBT therapy

posed RDL classification, one of the papers was scored differently (EMOTEO, DBT Coach, mDiary app); another was based

by the researchers, but this was clarified after reviewing the study on biofeedback using a smartwatch (wearable biosensor

together. device) and was aimed at ameliorating emotional dysreg-

ulation (Sense-IT); and the last one included content

from cognitive-behavioral therapy for crisis intervention

Results (B·RIGHT). All of them obtained data supporting their

acceptance and/or usability. In addition, two of them also

Detailed data of the results can be seen in Table 2. It proved their feasibility (DBT Coach and EMOTEO), and

includes 15 studies with accurate information based on three also included a web server (overview screen) for

the following variables: (1) type of technology (e.g., mo- therapists and/or patients (B·RIGHT, Sense-IT, mDiary

bile apps, web-based); (2) project name and authors; (3) app). (2) Wearable biosensor devices. Except for the study

type of treatment and target symptom (e.g., biofeedback, referred to above by Derks et al. [21], no software with

cognitive remediation); (4) distinctive features (e.g., un- clinical research was found.

guided self-management, beta version); (5) feasibility, us- Internet-Based Interventions. (1) Website-based inter-

ability, and acceptance testing (if performed); (6) efficacy ventions. There were two types of software (both beta ver-

and effectiveness testing (if performed); (7) total score sions) with some kind of clinical evidence (RDL: emerg-

(quantitative measure based on the proposed RDL); and ing). One of them, PRIOVI, was a guided self-manage-

(8) RDL (qualitative data based on the proposed RDL). ment intervention based on schema therapy and to be

used as an adjunctive intervention. PRIOVI reported data

Psychosocial Interventions Based on Information and proving its feasibility and acceptance [26, 27]. The other

Communication Technology software tested the effectiveness of a DBT psychoeduca-

mHealth-based Interventions. (1) Mobile app-based tion program as an unguided self-management interven-

interventions. There were five types of software (three tion. A randomized controlled trial showed that the web-

beta versions and two full versions) with little clinical ev- based intervention conferred additional and sustained

idence (RDL: immature): B·RIGHT [20], Sense-IT [21], improvements in BPD symptoms at 1-year follow-

EMOTEO [22], DBT Coach [23, 24], and mDiary app up when compared with a wait-list control group [28].

Technology-Based Psychosocial Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 257

Interventions for BPD DOI: 10.1159/000511349

Table 2. Clinical research in technology-based psycho interventions for BPD

Type of Project name and Type of treatment and target Distinctive features Feasibility, usability, and Efficacy and effectiveness Total RDL6

technology reference symptom acceptance testing testing score6

Mobile apps B·RIGHT (Frías et al. crisis intervention for emotional beta version (1 point); cognitive- pilot study with 25 patients none 2.5 immature

[20], 2020, Spain) crises behavioral-based intervention; includes a (0.5 points); U: good1 (1 point)

chatbot in the mobile app and a web

server (overview screen) for therapists;

unguided self-management intervention

Sense-IT (Derks et al. biofeedback (heart rate) for beta version (1 point); biofeedback-based multiple user groups (patients, none 3 immature

[21], 2019, The emotional dysregulation intervention; includes wearable device therapists, expert users;

Netherlands) (smartwatch) and a web server (overview 1 point); U: good for all types

screen) for patient/therapist; unguided of user groups1, 2 (1 point)

self-management intervention

mDiary app (Helweg- adjunctive (self-monitoring and beta version (1 point); DBT-based multiple user groups (patients, none 3 immature

Joergensen et al. [25], psychoeducation) to usual DBT intervention; includes a web server therapists) (1 point); U:

2019, Denmark) for emotional dysregulation and (overview screen) for patient/therapist and acceptable1 (higher scores by

self-harm GPS; unguided self-management patients than by therapists,

intervention and GPS considered invasive

by patients) (1 point)

DBT Coach (Rizvi et al. adjunctive to usual DBT for *prototype, **full version (in stores) *multiple user groups none *3; immature

[23], 2011, United improving mindfulness skills (1 point); DBT-based intervention; (patients, therapists; 1 point); **3.5

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

States*; Rizvi et al. [24], training for comorbid SUD* unguided self-management intervention **pilot study with 16 patients

2016, United States**) and NSSI** (0.5 points); F: *decreased

urge to use substances after

10–15 days (1 point);

**decreased urge to self-harm

and NSSI after 6 months

(1 point); U/A: *usable and

helpful for patients and

therapists3 (1 point); **usable

and helpful, but not enjoyable3

(1 point)

EMOTEO (Prada et al. adjunctive to usual DBT for full version (in stores; 1 point); DBT-based pilot study with 16 patients none 3.5 immature

[22], 2017, Switzerland) regulating aversive tension intervention; unguided self-management (women) (0.5 points); F:

intervention decreased aversion tension

after 6 months (1 point); U/A:

usable and helpful3 (1 point)

Web-based not reported (Zanarini DBT-psychoeducation for BPD beta version (1 point); DBT-based none RCT on effectiveness 5 emerging

et al. [28], 2018, United symptoms intervention; program is laid out like a (4 points); sample:

States) book; unguided self-management symptomatic volunteers

intervention (women) recruited

through ads by one

research center; arms:

web-based (n = 40) vs.

waitlist (n = 40);

procedure: 3‑month

treatment + 1‑year

follow-up; outcome:

additional and

maintained decline in

overall BPD symptoms4;

ES: medium (OR = 0.05);

attrition: <5%

PRIOVI (Fassbinder et adjunctive to usual and beta version (1 point); ST-based *single-case study; **multiple none *2; *immature;

al. [26], 2015, Germany*; individual ST for BPD intervention; includes a clinician-facing user groups (patients, **4 **emerging

Jacob et al. [27], 2018, symptoms interface; guided self-management therapists) (1 point); F:

The Netherlands**) intervention *improved BPD symptoms,

functioning, and schema

modes after 6 months

(1 point); **improved BPD

symptoms after 12 months

(1 point); A: **helpful for all

types of user groups2 (1 point)

Virtual not reported (Falconer adjunctive to usual group MBT beta version (1 point); MBT-based pilot study with 15 patients none 3.5 immature

reality et al. [29], 2017, United for improving mentalization intervention; includes virtual desktop and (0.5 points); F: mentalization

Kingdom) avatar software; delivered in a clinic and measures remained

guided by a therapist unchanged after 4 sessions

(1 point); A: helpful2 (1 point)

not reported (Nararro- adjunctive to usual DBT for beta version (1 point); DBT-based single-case study; F: higher none 2 immature

Haro et al. [30], 2016, improving mindfulness skills intervention; includes goggles and mindfulness scores after

Spain) training headphones; delivered in a clinic and 4 sessions (1 point)

guided by a therapist

258 Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 Frías/Solves/Navarro/Palma/Farriols/

DOI: 10.1159/000511349 Aliaga/Hernández/Antón/Riera

Table 2 (continued)

Type of Project name and Type of treatment and target Distinctive features Feasibility, usability, and Efficacy and effectiveness Total RDL6

technology reference symptom acceptance testing testing score6

Computer- CACR (Vita et al. [31], computer-based cognitive beta version (1 point); cognitive pilot study with 15 (TAU + none 2.5 immature

assisted 2018, Italy) remediation therapy for remediation-based intervention; delivered CACR) vs. 15 (TAU) patients

neurocognitive impairments in a clinic and guided by a therapist (0.5 points); F: CARC

and psychosocial dysfunction improved working memory

and functioning, but not BPD

symptoms after 4 months

(1 point)

CBST (Wolf et al. [32], computer-based therapy beta version (1 point); DBT-based pilot study with 13 (skills none 2.5 immature

2011, Germany) adjunctive to conventional intervention; includes a CD-ROM; training group + CBST) vs. 11

group DBT for facilitating the self-help program (skills training group) patients

learning process in skills (0.5 points); F: CBST

training improved skills acquisition

after 6 months (1 point)

fMRI not reported (Paret et al. real-time fMRI neurofeedback full version (1 point); biofeedback-based *pilot study with 8 patients *open trial on efficacy *2.5; *immature;

[33], 2016, Germany*; training (amygdala intervention; includes thermometer bar (0.5 points); F: fMRI (3 points); sample: 26 **4 **emerging

Zaehringer et al. [34], hemodynamic activity) for for amygdala activation; delivered in a neurofeedback training patients (women)

2019, Germany**) emotional dysregulation clinic and guided by a therapist improved dissociation and recruited by one research

lack of emotional awareness center; arm: fMRI

after 4 sessions (1 point) neurofeedback training;

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

procedure: 4‑session

treatment + 1.5‑month

follow-up; outcome:

maintained decline in

overall BPD symptoms

and emotional

dysregulation4, 5; ES:

medium (eta2: 0.14–0.18);

attrition: 2 people

A, acceptance; BPD, borderline personality disorder; CACR, computer-assisted cognitive remediation; CBST, computer-based skills training; CD-ROM, compact disc with read-only memory; DBT, dialectical

behavior therapy; ES, effect size; F, feasibility; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; GPS, Global Positioning System; MBT, mentalization-based therapy; NSSI, nonsuicidal self-injury; OR, odds ratio; RCT,

randomized controlled trial; RDL, research developmental level; ST, schema therapy; SUD, substance use disorder; TAU, treatment as usual; U, usability. 1 Subjective Usability Scale. 2 Qualitative interviews. 3 Satis-

faction and Usability Survey. 4 Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder. 5 Emotion Regulation Scale. 6 RDL (scores): immature (0–3), emerging (4–8), promising (9–12), adequate (13–16), and vali-

dated (17–20).

(2) Virtual therapeutic communities. No software with (RDL: immature): cognitive-based cognitive remediation

clinical research was found. therapy proved its feasibility as an adjunctive therapy to

Telehealth. (1) Videoconferencing. No software with treatment as usual (TAU) [31], and a DBT-based therapy

clinical research was found. (2) Email messages. No soft- showed its feasibility as an adjunctive intervention to

ware with clinical research was found. conventional DBT-based treatment [32].

Psychosocial Interventions Based on Computing Psychosocial Interventions Based on Computational

Technology Technology

Virtual and Augmented Reality. There were two types Artificial Intelligence Algorithms. No software with

of virtual reality software (beta version) with little clinical clinical research was found.

evidence (RDL: immature). One was an adjunctive men- Machine Learning and Big Data. No software with

talization-based therapy whose data proved its accep- clinical research was found.

tance, but feasibility was not completely confirmed (out- Deep Learning and Neural Networks. No software with

come measures remained unchanged after the four ses- clinical research was found.

sions [29]); the other was an adjunctive DBT-based

therapy that showed preliminary feasibility in a single- Psychosocial Interventions Based on Medical

case study [30]. Technology

Serious Games. No software with clinical research was Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. There was

found. one type of software (full version) with some kind of clin-

Eye-Tracking. No software with clinical research was ical evidence (RDL: emerging). Initially, real-time fMRI

found. neurofeedback training for amygdala hemodynamic ac-

Computer-Based Interventions. There were two types tivity was found to be feasible [33]. Then, the same re-

of software (beta version) with little clinical evidence search group performed an open trial showing sustained

Technology-Based Psychosocial Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 259

Interventions for BPD DOI: 10.1159/000511349

improvements in BPD symptoms at 1.5-month follow-up vention with an inactive control group (waitlist). In ad-

after using the same fMRI neurofeedback training [34]. dition, these studies on effectiveness and efficacy should

Other Medical Technology. No other medical software include data from satisfaction/preference and safety/se-

with clinical research was found. curity testing. Particularly, mobile app-based psychoso-

cial treatments for BPD need further empirical evidence

beyond the current studies [37]. Studies on efficiency

Discussion testing were obviously lacking and should be implement-

ed because healthcare institutions with BPD patients as

Summary of Evidence part of their clinical services may prioritize cost-effective

This scoping review aimed to delineate an up-to-date software. This scoping review also supports the prioriti-

description of the ongoing technology-based psychoso- zation of Internet-based interventions, not only due to

cial treatments for BPD with some kind of clinical re- the current empirical evidence, but also because they are

search: (1) almost two-thirds of the studies (9/15) tested more scalable and useful than other promising technolo-

software explicitly conceived as adjunctive interventions gies (e.g., fMRI feedback) from a public health perspec-

to conventional therapy; (2) nearly half of the studies tive.

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

(7/15) were referred to as DBT-based software; (3) most Proposed New Approaches to Technology-Based Psy-

studies (13/15) were focused on the initial stage of the chosocial Treatments in BPD. Regardless of the findings

clinical research cycle (feasibility/acceptance/usability of the current scoping review and considering prior re-

testing), reporting good results at this point; (4) more search using technology for other mental health problems

than one-third of the studies (6/15) tested mobile apps; than BPD, several symptom-specific treatments for BPD

(5) clinical evidence was stronger for studies on web- are proposed. First, virtual reality may be used in order to

based interventions than in studies on other technology; induce positive emotions in BPD patients when depressed

(6) there was no computational technology-based clinical or when dealing with comorbid disorders such as post-

research; and (7) there was no satisfaction/preference, se- traumatic stress disorder or agoraphobia [11]. Second,

curity/safety, or efficiency testing for any software. telehealth may be suitable for BPD patients who are living

in remote places or during confinement [38]; virtual ther-

Limitations apeutic communities may be pertinent for treatment-na-

Studies on feasibility, acceptance, and usability had ïve patients or those socially isolated as a way to offer psy-

several limitations. (1) Four studies only employed a us- choeducation and emotional support, as long as these In-

er-centered approach instead of multiple user groups for ternet forums are moderated by a trained clinician and

usability and acceptance testing [20, 22, 24, 29]. Specifi- participants have already been diagnosed with BPD rath-

cally, provider (therapist) opinions should be always tak- er than self-diagnosed [39]. To these ends, there is a need

en into consideration because they are responsible of im- for integrative technology and scalability. For instance,

plementing the new technology in the healthcare setting some technology used for assessment may also be incor-

[25]. (2) None of the studies assessed baseline cognitive porated for intervention in BPD (e.g., eye-tracking, fMRI)

intelligence as a potential moderator variable associated [40, 41]. Likewise, adaptations of proved technology in

with the referred outcomes [35]. (3) Generalization of other mental disorders (e.g., mDiary for bipolar disorder)

findings was limited because most samples predominant- may be considered. Similarly, transdiagnostic software

ly consisted of women and two studies were based on sin- (e.g., for self-harm) may be valuable for treating patients

gle-case studies [26, 30]. with BPD [25, 42]. Ultimately, convergences between dif-

ferent but complementary technology should be priori-

Recommendations for Future Research tized (e.g., wearable devices plus mobile apps; virtual real-

Future Research on Existing Technologies. Studies on ity plus Internet-based) [21]. Specifically, the addition of

effectiveness and efficacy are still pending in all software serious games into mobile app-based and Internet-based

with prior data from feasibility, acceptance, and/or us- interventions is warranted in order to promote real-world

ability testing [36]. For those adjunctive interventions, utilization (user engagement) of the former software, tak-

these types of studies should include a combination ther- ing into account that these patients are prone to boredom

apy (TAU + technology-based treatment) and compare susceptibility [13]. An alternative approach may be the

it with TAU alone. For those alternative interventions, gamification of this software by including gamified chat-

studies should first compare the technology-based inter- bots, which somehow partly replace therapeutic alliance

260 Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 Frías/Solves/Navarro/Palma/Farriols/

DOI: 10.1159/000511349 Aliaga/Hernández/Antón/Riera

as a core element for patients with special needs of inter- forts should be made to complete the clinical research

personal dependency [43]. cycle for this technology on the basis of both user (pa-

Proposed Contraindications to Technology-Based Psy- tient) and provider (therapist) recommendations. Ulti-

chosocial Interventions in BPD. Due to the lack of safety mately, these types of interventions should be symptom-

and security testing, the following potential contraindica- specific and solve real-world problems with an adequate

tions should be considered in people with BPD treated and personalized risk-benefit balance.

with technology-based psychosocial interventions. These

contradictions do not emerge from the included studies,

but are developed from other research on Internet inter- Conflict of Interest Statement

ventions on other mental disorders. (1) Mobile apps and

Á. Frías received grants from the CaixaImpulse program (LCF/

web-based treatments should be delivered cautiously

TR/CI18/50030016), the Fundació Blanquerna-University of Ra-

with those at risk or already having comorbid behavioral mon-Llull, and the Col·legi Oficial de Psicologia de Catalunya for

addictions such as nomophobia, Internet addiction, and/ the technical development of the mobile-app B·RIGHT. For the

or gaming disorder [44–46]. (2) Virtual therapeutic com- remaining authors non conflicts of interest are declared.

munities should be avoided or monitored in those with

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

higher baseline hostility levels, who in turn are at greater

risk of online peer rejection and also cyberbullying [47, Funding Sources

48]. (3) Virtual reality should be implemented cautiously

Á. Frías received funds (SLT008/18/00175) for editing and

for those with higher baseline dissociation levels due to proofreading the manuscript from the Pla Estratègic de Recerca i

the immersion and absorption effects of this technology Innovació en Salut (PERIS 2019-2021) of the Department of

[49]. (4) Wearable biofeedback devices should be special- Health, Generalitat de Catalunya. For the remaining authors no

ly monitored in those with higher baseline neuroticism funding is declared.

levels and trait anxiety because of the risk of paradoxical

reactions (anxiety) and compulsive behaviors (reassur-

ance). (5) The use of screen view monitors for therapists Author Contributions

(connected to mHealth devices) should always be dis-

Á. Frías wrote the paper with L. Solves. S. Navarro, A. Riera, M.

cussed with patients in general and those with greater Hernández, and M. Antón drafted the manuscript. All authors

paranoid ideation specifically, who may feel that such contributed to the reviewing of the final version of the manuscript.

treatments are invasive. In particular, this subgroup has

special “psychoeducation” needs regarding confidential-

ity and data protection/security [50]. In order to prevent

References 1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnos-

these potential adverse effects, artificial intelligence- tic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disor-

based assessment software may delineate high-risk sub- ders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psy-

groups on the basis of the aforementioned baseline clini- chiatric Association; 2013.

2 ten Have M, Verheul R, Kaasenbrood A, van

cal variables (behavioral addictions, dissociation, hostil- Dorsselaer S, Tuithof M, Kleinjan M, et al.

ity, paranoid ideation, trait anxiety). Ultimately, this may Prevalence rates of borderline personality dis-

lead to personalized technology-based psychosocial treat- order symptoms: A study based on the Neth-

erlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence

ments in BPD [41]. Study-2. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):249.

3 Soloff PH, Chiappetta L. Time, age, and pre-

dictors of psychosocial outcome in borderline

personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2020 Apr;

Conclusions 34(2):145–60.

4 Wagner T, Fydrich T, Stiglmayr C, Marschall

P, Salize HJ, Renneberg B, et al. Societal cost-

This scoping review has shown that there are a grow- of-illness in patients with borderline person-

ing and ongoing, but still incipient number of technolo- ality disorder one year before, during and af-

gy-based psychosocial interventions for BPD supported ter dialectical behavior therapy in routine

outpatient care. Behav Res Ther. 2014;61:12–

by some kind of clinical research and evidence. Particu- 22.

larly, there is emerging evidence for Internet-based inter- 5 Levy KN, McMain S, Bateman A, Clouthier T.

ventions and real-time fMRI biofeedback, but only little Treatment of borderline personality disorder.

Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41(4):711–28.

evidence for mHealth interventions, virtual and aug-

mented reality, and computer-based interventions. Ef-

Technology-Based Psychosocial Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 261

Interventions for BPD DOI: 10.1159/000511349

6 Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, 20 Frías Á, Palma C, Salvador A, Aluco E, Na- 31 Vita A, Deste G, Barlati S, Poli R, Cacciani P,

Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies varro S, Farriols N, et al. B·RIGHT: usability De Peri L, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of

for people with borderline personality disor- and satisfaction with a mobile app for self- cognitive remediation in the treatment of bor-

der. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; managing emotional crises in patients with derline personality disorder. Neuropsychol

8:CD005652. borderline personality disorder. Australas Rehabil. 2018;28(3):416–28.

7 Arntz A, Stupar-Rutenfrans S, Bloo J, van Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/ 32 Wolf M, Ebner-Priemer U, Schramm E,

Dyck R, Spinhoven P. Prediction of treatment 1039856220924321 [Epub ahead of print]. Domsalla M, Hautzinger M, Bohus M. Maxi-

discontinuation and recovery from border- 21 Derks YP, Klaassen R, Westerhof GJ, Bohl- mizing skills acquisition in dialectical behav-

line personality disorder: results from an RCT meijer ET, Noordzij L. Development of an ioral therapy with a CD-ROM-based self-help

comparing schema therapy and transference ambulatory biofeedback app to enhance emo- program: results from a pilot study. Psycho-

focused psychotherapy. Behav Res Ther. tional awareness in patients with borderline pathology. 2011;44(2):133–5.

2015;74:60–71. personality disorder: Multicycle usability 33 Paret C, Kluetsch R, Zaehringer J, Ruf M,

8 Temes CM, Zanarini MC. Recent develop- testing study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019; Demirakca T, Bohus M, et al. Alterations of

ments in psychosocial interventions for bor- 7:e13479. amygdala-prefrontal connectivity with real-

derline personality disorder. F1000Res. 2019 22 Prada P, Zamberg I, Bouillault G, Jimenez N, time fMRI neurofeedback in BPD patients.

Apr;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-561. Zimmermann J, Hasler R, et al. EMOTEO: A Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016; 11(6): 952–

9 Bakker D, Kazantzis N, Rickwood D, Rickard smartphone application for monitoring and 60.

N. Mental health smartphone apps: review reducing aversive tension in borderline per- 34 Zaehringer J, Ende G, Santangelo P, Klein

and evidence-based recommendations for fu- sonality disorder patients: A pilot study. Per- dienst N, Ruf M, Bertsch K, et al. Improved

ture developments. JMIR Ment Health. 2016; spect Psychiatr Care. 2017;53(4):289–98. emotion regulation after neurofeedback: A

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

3(1):e7. 23 Rizvi SL, Dimeff LA, Skutch J, Carroll D, Line- single-arm trial in patients with borderline

10 Ben-Zeev D. Technology-based interventions han MM. A pilot study of the DBT coach: an personality disorder. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;

for psychiatric illnesses: improving care, one interactive mobile phone application for indi- 24:102032.

patient at a time. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. viduals with borderline personality disorder 35 Dubad M, Winsper C, Meyer C, Livanou M,

2014;23(4):317–21. and substance use disorder. Behav Ther. 2011; Marwaha S. Systematic review of the psycho-

11 Freeman D, Reeve S, Robinson A, Ehlers A, 42(4):589–600. metric properties, usability and clinical im-

Clark D, Spanlang B, et al. Virtual reality in 24 Rizvi SL, Hughes CD, Thomas MC. The DBT pacts of mobile mood-monitoring applica-

the assessment, understanding, and treat- Coach mobile application as an adjunct to tions in young people. Psychol Med. 2018;

ment of mental health disorders. Psychol treatment for suicidal and self-injuring indi- 48(2):208–28.

Med. 2017;47(14):2393–400. viduals with borderline personality disorder: 36 Klein JP, Hauer A, Berger T, Fassbinder E,

12 Graham S, Depp C, Lee EE, Nebeker C, Tu X, A preliminary evaluation and challenges to Schweiger U, Jacob G. Protocol for the RE-

Kim HC, et al. Artificial intelligence for men- client utilization. Psychol Serv. 2016; 13(4): VISIT-BPD Trial: A randomized controlled

tal health and mental illnesses: an overview. 380–8. trial testing the effectiveness of an Internet-

Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(11):116. 25 Helweg-Joergensen S, Schmidt T, Lichten- based self-management intervention in the

13 Cuijpers P, Noma N, Karyotaki E, Cipriani A, stein MB, Pedersen SS. Using a mobile diary treatment of borderline personality disorder

Furukawa TA. Effectiveness and acceptability app in the treatment of borderline personality (BPD). Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:439.

of cognitive behavior therapy delivery for- disorder: mixed methods feasibility study. 37 Ilagan GS, Iliakis EA, Wilks CR, Vahia IV,

mats in adults with depression: A network JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(3):e12852. Choi-Kain LW. Smartphone applications tar-

meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019; 76(7): 26 Fassbinder E, Hauer A, Schaich A, Schweiger geting borderline personality disorder symp-

700–7. U, Jacob GA, Arntz A. Integration of e-health toms: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

14 Lau HM, Smit JH, Fleming TM, Riper H. Seri- tools into face-to-face psychotherapy for bor- Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul.

ous games for mental health: are they acces- derline personality disorder: A chance to 2020 Jun;7(1):12.

sible, feasible, and effective? A Systematic re- close the gap between demand and supply? J 38 Munz D, Jansen A, Böhmig C. Remote treat-

view and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. Clin Psychol. 2015;71(8):764–77. ment from a psychotherapeutic point of view.

2017;7:209. 27 Jacob GA, Hauer A, Köhne S, Assmann N, Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2019;87:165–71.

15 Lawes-Wickwar S, McBain H, Mulligan K. Schaich A, Schweiger U, et al. A schema ther- 39 Habermeyer E, Habermeyer V, Jähn K,

Application and effectiveness of telehealth to apy-based eHealth program for patients with Domes G, Nagel E, Herpertz SC. An Internet

support severe mental illness management: borderline personality disorder (priovi): nat- based discussion board for persons with bor-

systematic review. JMIR Ment Health. 2018; uralistic single-arm observational study. derline personality disorders moderated

5(4):e62. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(4):e10983. health care professionals. Psychiatr Prax.

16 Mehrotra S, Tripathi R. Recent developments 28 Zanarini MC, Conkey LC, Temes CM, 2009;36:23–9. German.

in the use of smartphone interventions for Fitzmaurice GM. Randomized controlled tri- 40 Bertsch K, Krauch M, Stopfer K, Haeussler K,

mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018; al of web-based psychoeducation for women Herpertz SC, Gamer M. Interpersonal threat

31(5):379–88. with borderline personality disorder. J Clin sensitivity in borderline personality disorder:

17 Lezama-Nicolás R, Rodríguez-Salvador M, Psychiatry. May–Jun 2018;79(3):16m11153. an eye-tracking study. J Pers Disord. 2017;

Río-Belver R, Bildosola I. A bibliometric 29 Falconer CJ, Cutting P, Bethan Davies E, Hol- 31(5):647–70.

method for assessing technological maturity: lis C, Stallard P, Moran P. Adjunctive avatar 41 Schmitgen MM, Niedtfeld I, Schmitt R,

the case of additive manufacturing. Sciento- therapy for mentalization-based treatment of Mancke F, Winter D, Schmahl C, et al. Indi-

metrics. 2018;117(3):1425–52. borderline personality disorder: A mixed- vidualized treatment response prediction of

18 Chauhan R, Singh I. Latest research and de- methods feasibility study. Evid Based Ment dialectical behavior therapy for borderline

velopment on software testing techniques and Health. 2017;20(4):123–7. personality disorder using multimodal mag-

tools. Int J Curr Eng Technol. 2014; 4: 2368– 30 Nararro-Haro MV, Hoffman HG, Garcia-Pa- netic resonance imaging. Brain Behav. 2019;

72. lacios A, Sampaio M, Alhalabi W, Hall K, et 9(9):e01384.

19 Guyatt G, Cairns J, Churchill D, et al. Evi- al. The use of virtual reality to facilitate mind-

dence-based medicine. A new approach to fulness skills training in dialectical behavioral

teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. therapy for borderline personality disorder: a

1992;268(17):2420–5. case study. Front Psychol. 2016 Nov;7:1573.

262 Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 Frías/Solves/Navarro/Palma/Farriols/

DOI: 10.1159/000511349 Aliaga/Hernández/Antón/Riera

42 Wilks CR, Lungu A, Ang SY, Matsumiya B, 45 Lu WH, Lee KH, Ko CH, Hsiao RC, Hu HF, 48 Richmond JR, Edmonds KA, Rose JP, Gratz

Yin Q, Linehan MM. A randomized con- Yen CF. Relationship between borderline per- KL. Examining the impact of online rejection

trolled trial of an Internet delivered dialectical sonality symptoms and Internet addiction: among emerging adults with borderline per-

behavior therapy skills training for suicidal the mediating effects of mental health prob- sonality pathology: development of a novel

and heavy episodic drinkers. J Affect Disord. lems. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):434–41. online group chat social rejection paradigm.

2018;232:219–28. 46 Marmet S, Studer J, Wicki M, Bertholet N, Pers Disord. 2020;11(5):301–11.

43 Bedics JD, Atkins DC, Harned MS, Linehan Khazaal Y, Gmel G. Unique versus shared as- 49 Aardema F, O’Connor K, Côté S, Taillon A.

MM. The therapeutic alliance as a predictor of sociations between self-reported behavioral Virtual reality induces dissociation and low-

outcome in dialectical behavior therapy ver- addictions and substance use disorders and ers sense of presence in objective reality. Cy-

sus nonbehavioral psychotherapy by experts mental health problems: A commonality berpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(4):429–

for borderline personality disorder. Psycho- analysis in a large sample of young Swiss men. 35.

therapy (Chic). 2015;52(1):67–77. J Behav Addict. 2019;8(4):664–77. 50 Orme W, Bowersox L, Vanwoerden S, Fonagy

44 Chen TH, Hsiao RC, Liu TL, Yen CF. Predict- 47 Lazarus SA, Cheavens JS. An examination of P, Sharp C. The relation between epistemic

ing effects of borderline personality symp- social network quality and composition in trust and borderline pathology in an adoles-

toms and self-concept and identity distur- women with and without borderline person- cent inpatient sample. Borderline Personal

bances on internet addiction, depression, and ality disorder. Pers Disord. 2017;8(4):340–8. Disord Emot Dysregul. 2019;6(1):13.

suicidality in college students: A prospective

study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019; 35(8):508–

14.

Downloaded from http://karger.com/psp/article-pdf/53/5-6/254/3493765/000511349.pdf by guest on 23 May 2024

Technology-Based Psychosocial Psychopathology 2020;53:254–263 263

Interventions for BPD DOI: 10.1159/000511349

You might also like

- International Human Resource ManagementDocument44 pagesInternational Human Resource ManagementUmera Anjum85% (26)

- Bhatia Sample ReportDocument1 pageBhatia Sample ReportNazema_Sagi100% (2)

- Interpersonel Need of Management Student-Acilitor in The Choice of ElectivesDocument180 pagesInterpersonel Need of Management Student-Acilitor in The Choice of ElectivesnerdjumboNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Preferences For Online Psychological Interventions - 2023 - PsychiatDocument10 pagesEvaluating Preferences For Online Psychological Interventions - 2023 - Psychiattito syahjihadNo ratings yet

- Developing A Smartphone App Based On The Unified Protocol For T 2022 InterneDocument8 pagesDeveloping A Smartphone App Based On The Unified Protocol For T 2022 InterneIda HamidahNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0005789419300966 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0005789419300966 Main1klinikpsixologiyaNo ratings yet

- Digital Technologies For Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive ReviewDocument22 pagesDigital Technologies For Schizophrenia Management: A Descriptive ReviewAngela EnacheNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: Internet InterventionsDocument34 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: Internet InterventionscarolinaNo ratings yet

- Technology and Mental Health The Role of A IDocument4 pagesTechnology and Mental Health The Role of A IMichaelaNo ratings yet

- E-Mental Health: Contributions, Challenges, and Research Opportunities From A Computer Science PerspectiveDocument10 pagesE-Mental Health: Contributions, Challenges, and Research Opportunities From A Computer Science Perspectiveabdessalam.ouaazkiNo ratings yet

- A Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Smartphone App For Adolescent Depression and Anxiety: Co-Design of ClearlymeDocument33 pagesA Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Smartphone App For Adolescent Depression and Anxiety: Co-Design of Clearlymestevenkanyanjua1No ratings yet

- The Growing Field of Digital Psychiatry: Current Evidence and The Future of Apps, Social Media, Chatbots, and Virtual RealityDocument18 pagesThe Growing Field of Digital Psychiatry: Current Evidence and The Future of Apps, Social Media, Chatbots, and Virtual RealitydojabrNo ratings yet

- Content Writing - Digital Interventions in Medial FieldDocument9 pagesContent Writing - Digital Interventions in Medial FieldAzeemNo ratings yet

- Hafta OkumasıDocument8 pagesHafta OkumasıAlan TNo ratings yet

- The Digital Transformation of Mental Health Care and Psychotherapy - A Market and Research Maturity AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Digital Transformation of Mental Health Care and Psychotherapy - A Market and Research Maturity AnalysispqdwsnkhtzNo ratings yet

- The Current State and Validity of Digital Assessment Tools For Psychiatry: Systematic ReviewDocument24 pagesThe Current State and Validity of Digital Assessment Tools For Psychiatry: Systematic ReviewHassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Conversational Artificial Intelligence in Psychotherapy A New Therapeutic Tool or AgentDocument11 pagesConversational Artificial Intelligence in Psychotherapy A New Therapeutic Tool or AgentEmilija IlicNo ratings yet

- Ciuca Et Al 2017 Case Study Positive and Negative Outcomes iCBTDocument44 pagesCiuca Et Al 2017 Case Study Positive and Negative Outcomes iCBTVodafone VodafoneNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence-Informed Mobile Mental HeaDocument20 pagesArtificial Intelligence-Informed Mobile Mental HeaJosé Luis PsicoterapeutaNo ratings yet

- Advancing Mental Health Diagnostics GPT-Based Method For Depression DetectionDocument7 pagesAdvancing Mental Health Diagnostics GPT-Based Method For Depression DetectionconverttoaudioNo ratings yet

- Indian Journal of Behavioral Research (2022, Vol-3, No 3 & 4) - 110-120Document12 pagesIndian Journal of Behavioral Research (2022, Vol-3, No 3 & 4) - 110-120sumitravanzara1407No ratings yet

- Mental Wellness Portal PsychCafeDocument11 pagesMental Wellness Portal PsychCafeIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Background of The Study: Mental Disorder Management and Patient-Psychologist CommunicationDocument3 pagesBackground of The Study: Mental Disorder Management and Patient-Psychologist CommunicationMaryNicoleDatlanginNo ratings yet

- Understanding Engagement Strategies in Digital Interventions For Mental Health Promotion - Scoping Review - PMCDocument27 pagesUnderstanding Engagement Strategies in Digital Interventions For Mental Health Promotion - Scoping Review - PMCAlthea WhiteNo ratings yet

- s12913 022 08968 2Document19 pagess12913 022 08968 2ARGEMIRO JOSE AMAYA BUELVASNo ratings yet

- Behavior Ther - 2022 53Document14 pagesBehavior Ther - 2022 53Nani BluNo ratings yet

- Metaanalisis Castro Et Al. 2019Document37 pagesMetaanalisis Castro Et Al. 2019LauraNo ratings yet

- Digital Footprints Facilitating Large Scale Psychiatric Research Naturalistic 2017Document6 pagesDigital Footprints Facilitating Large Scale Psychiatric Research Naturalistic 2017Lucas De Francisco CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Digital Health in Supporting Cancer Patients-1-8Document8 pagesThe Role of Digital Health in Supporting Cancer Patients-1-8EduardoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Digital Health in Supporting Cancer PatientsDocument19 pagesThe Role of Digital Health in Supporting Cancer PatientsEduardoNo ratings yet

- Jba 9 433Document13 pagesJba 9 433tito syahjihadNo ratings yet

- Pánico y agorafobiaDocument14 pagesPánico y agorafobiaEmilio Garcia DiazNo ratings yet

- Kazdin, 2015Document8 pagesKazdin, 2015Elizabeth Roxan Lizaso GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Final DraftDocument32 pagesFinal DraftShibanta SarenNo ratings yet

- Aproximación transdiagnósticaDocument10 pagesAproximación transdiagnósticaivanegeaventuraNo ratings yet

- Mobile Apps For Bipolar DisorderDocument14 pagesMobile Apps For Bipolar DisorderPsydocNo ratings yet

- Mobile Monitoring of Mood (MoMo-Mood) Pilot - A Longitudinal, Multi-Sensor Digital Phenotyping Study of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder and Healthy ControlsDocument10 pagesMobile Monitoring of Mood (MoMo-Mood) Pilot - A Longitudinal, Multi-Sensor Digital Phenotyping Study of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder and Healthy ControlsCheryl OngNo ratings yet

- Creating A Digital Health Smartphone App and Digital Phenotyping Platform For Mental Health and Diverse Healthcare NeedsDocument13 pagesCreating A Digital Health Smartphone App and Digital Phenotyping Platform For Mental Health and Diverse Healthcare NeedsMichaelaNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesLiterature ReviewnotmuappleNo ratings yet

- medicina-60-00445Document15 pagesmedicina-60-00445Rounak DubeyNo ratings yet

- World Psychiatry - 2021 - Torous - The Growing Field of Digital Psychiatry Current Evidence and The Future of Apps SocialDocument18 pagesWorld Psychiatry - 2021 - Torous - The Growing Field of Digital Psychiatry Current Evidence and The Future of Apps Socialakbar nur azizNo ratings yet

- FC Xsltgalley 6186 120841 40 PBDocument16 pagesFC Xsltgalley 6186 120841 40 PBVinitha DsouzaNo ratings yet

- Version of Record:: ManuscriptDocument20 pagesVersion of Record:: ManuscriptElizabeth Roxan Lizaso GonzálezNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Digital Media On Adolescent Mental HealthDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Digital Media On Adolescent Mental Healthkyhn.beycaNo ratings yet

- Validityof Chatbot Usefor Mental Health AssessmentDocument17 pagesValidityof Chatbot Usefor Mental Health AssessmentCeci ReyesNo ratings yet

- Digital Psychiatry: Ethical Risks and Opportunities For Public Health and Well-BeingDocument30 pagesDigital Psychiatry: Ethical Risks and Opportunities For Public Health and Well-Beingpeter silieNo ratings yet

- 1745 6215 14 437Document7 pages1745 6215 14 437Gustavo Adolfo Pimentel ParraNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Machine Learning Techniques in The Study of Bipolar DisorderDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Machine Learning Techniques in The Study of Bipolar DisorderDiego Librenza GarciaNo ratings yet

- Medication Reminder and Healthcare - An Android ApplicationDocument8 pagesMedication Reminder and Healthcare - An Android ApplicationMichaelaNo ratings yet

- A. Pozza, A. Coluccia, G. Gualtieri, F. FerrettiDocument7 pagesA. Pozza, A. Coluccia, G. Gualtieri, F. FerrettiGabyMaría DelValle Cordero Gómez ⃝⃤No ratings yet

- Mindfulness-Based Mobile Applications: Literature Review and Analysis of Current FeaturesDocument19 pagesMindfulness-Based Mobile Applications: Literature Review and Analysis of Current FeaturesFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Technology Based Inter Substance and Comorbid Examination Emerging Literature Sugarman 2017Document12 pagesTechnology Based Inter Substance and Comorbid Examination Emerging Literature Sugarman 2017Itzcoatl Torres AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Health 3Document15 pagesHealth 3tanNo ratings yet

- Technology For Activity Participation in Older People With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: Expert Perspectives and A Scoping ReviewDocument23 pagesTechnology For Activity Participation in Older People With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: Expert Perspectives and A Scoping ReviewDilraj Singh BalNo ratings yet

- APA (2020) Guidance On Psychological Tele-Assessment During The COVID-19 CrisisDocument7 pagesAPA (2020) Guidance On Psychological Tele-Assessment During The COVID-19 CrisisDavidNo ratings yet

- Adhd in Ehealth - A Systematic Literature Review: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesAdhd in Ehealth - A Systematic Literature Review: Sciencedirectmohd ikramNo ratings yet

- Mental Disorder Detection Via Machine LearningDocument5 pagesMental Disorder Detection Via Machine LearningIqra SaherNo ratings yet

- Conversational Artificial Intelligence in Psychotherapy A New Therapeutic Tool or AgentDocument11 pagesConversational Artificial Intelligence in Psychotherapy A New Therapeutic Tool or AgentM.A.A. CarascoNo ratings yet

- Validity of Teleneuropsychology For Older Adults in Response To COVID 19 A Systematic and Critical Review PDFDocument43 pagesValidity of Teleneuropsychology For Older Adults in Response To COVID 19 A Systematic and Critical Review PDFDaniel Londoño GuzmánNo ratings yet

- 173 FullDocument4 pages173 Fullannayun111No ratings yet

- Health Mobile AppsDocument7 pagesHealth Mobile Apps.No ratings yet

- ShagunSharma_A023167023144Document14 pagesShagunSharma_A023167023144Nikunj Shah3540No ratings yet

- Human Motor Control 2nd Edition Rosenbaum Test BankDocument5 pagesHuman Motor Control 2nd Edition Rosenbaum Test BankKyleFitzgeraldyckas100% (14)

- CSSI Assignment, Group 1 EPGP 2022-23Document16 pagesCSSI Assignment, Group 1 EPGP 2022-23Nishant BiswalNo ratings yet

- Traits and Skills Theories As The Nexus Between Leadership and Expertise Reality or FallacyDocument9 pagesTraits and Skills Theories As The Nexus Between Leadership and Expertise Reality or FallacyHandsome RobNo ratings yet

- Human Aspects PDFDocument4 pagesHuman Aspects PDFMonaNo ratings yet

- Module 3Document31 pagesModule 3Kristel GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four Notes ExampleDocument3 pagesChapter Four Notes Exampleapi-269124497No ratings yet

- Community Mental HealthDocument20 pagesCommunity Mental HealthLulano MbasuNo ratings yet

- Student WPQ QuestionnaireDocument15 pagesStudent WPQ Questionnaireluis filipeNo ratings yet

- Psychological Case Study: MichelangeloDocument11 pagesPsychological Case Study: MichelangeloKeanu BenavidezNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Physical Fitness and Wellness PDFDocument41 pagesConcepts of Physical Fitness and Wellness PDF9zx27kwfgwNo ratings yet

- Neuroticism Is One of TheDocument3 pagesNeuroticism Is One of TheCristian Ionita100% (1)

- OB MCQsDocument1 pageOB MCQsAshish VyasNo ratings yet

- QUALITATIVE RESEARCH - The Effects of Bullying On The Academic Performance of SHS HUMSS Students in SVCIDocument70 pagesQUALITATIVE RESEARCH - The Effects of Bullying On The Academic Performance of SHS HUMSS Students in SVCIJean Klitzku T. RecamaraNo ratings yet

- Ie 5211 New Product Management Homework #2 "Gemba Study For Lip Sticks"Document4 pagesIe 5211 New Product Management Homework #2 "Gemba Study For Lip Sticks"rmprasad878013No ratings yet

- (The Basics Series) Ian Donald - Environmental and Architectural Psychology - The Basics-Routledge (2022)Document265 pages(The Basics Series) Ian Donald - Environmental and Architectural Psychology - The Basics-Routledge (2022)Antonio MontesNo ratings yet

- Attachment Security and Perceived Parental Psychological Control As Parameters of Social Value Orientation Among Early AdolescentsDocument7 pagesAttachment Security and Perceived Parental Psychological Control As Parameters of Social Value Orientation Among Early AdolescentsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Strategic Thinking Part1Document15 pagesStrategic Thinking Part1ektasharma123No ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Human Growth and DevelopmentDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics Human Growth and DevelopmentntjjkmrhfNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Student Learning Motivation On Learning SatisfactionDocument26 pagesThe Effect of Student Learning Motivation On Learning SatisfactionNastya ZhukovaNo ratings yet

- Week 6 DQ 1Document2 pagesWeek 6 DQ 1Lindsay WatsonNo ratings yet

- Reflections On SupervisionDocument19 pagesReflections On Supervisiondrguillermomedina100% (1)

- Video ScriptDocument2 pagesVideo Scriptapi-489557181No ratings yet

- Stress Lessons Educators Guide en (1) 0Document52 pagesStress Lessons Educators Guide en (1) 0Safaa K. AbuTairNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Johari WindowDocument10 pagesIntroduction To The Johari Windowjack0009No ratings yet

- College of Nursing Nursing Care Plan: Initials of Client: M.M. Age: 30Document2 pagesCollege of Nursing Nursing Care Plan: Initials of Client: M.M. Age: 30teuuuuNo ratings yet

- Core Beliefs of A Renegade HypnotistDocument4 pagesCore Beliefs of A Renegade HypnotistGerardo Maureira IbacacheNo ratings yet

- EmpathyDocument2 pagesEmpathySambhav ThakurNo ratings yet