Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adobe Scan 22-Mar-2024

Adobe Scan 22-Mar-2024

Uploaded by

Snipe X0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views49 pagesWEAGV Sd SFV

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWEAGV Sd SFV

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views49 pagesAdobe Scan 22-Mar-2024

Adobe Scan 22-Mar-2024

Uploaded by

Snipe XWEAGV Sd SFV

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 49

1

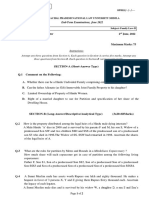

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS

[Were it left to me to decide whether we should

have a government without newspapers, or

newspapers without a government, I should

not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.'

This chapter examines the constitutional provisions which form the basis

for the rights of the media in India. It is broadly divided into two sec-

tions: the first section outlines the constitutional provisions on the free-

dom of speech and expression and the constitutional status of the media

in India. This section also examines what the freedom of speech and

expression means in the context of the media and outlines its many fac-

ets. The second section analyses the constitutionally permissible restric-

tions on the freedom of speech and expression.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS ON THE

FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND EXPRESSION

The freedom of speech and expression has been described as the mother

of all liberties. In Ramlila Maidan Incident, re,? the Supreme Court held:

The freedom of speech and expressio

dition of liberty. It occupies a preferr

of liberties, giving succour and protect

It has been truly said that it is the mother

Freedom of speech plays a crucial role in the fori

pinion on social, political and economic matter

described as a ‘basic human right’, ‘a natural right’ ad the li

With the development of law in India the right to fryedorf of

is regarded as the first con-

position in the hierarchy

to all other lil

mas Jefferson in a letter to Edward Carrington, 16-1-1787.

2 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

speech and expression has

aken withi

receive inform

‘ation as well as the right

The Preamble to the Constitutior

zens of India, liberty of thought, expression and bel;

of the Constitution from which i

tees to every citizen of India, the «

Article 19(1)(a) is a fundamental right guar,

India.’ Article 19(r)(a) reads:

19. (1) All citizens shall have the right—

(a) to freedom of speech and expression;

n its ambit the 5;

of press,

The exceptions to the right guaran

tained in Article y

teed under Article 19(1)(

9(2) which reads:

(a)

Constitutional Status of the media :

The media derives its rights from the right to freedom of spee

© the citizen, Thus, the media has

0 less than any individual to write, publis

Case that arose in Pre-independent India,

late or broadcast.

-Ina

Council held:

The freedom of the journalist is an Ordinary part of the freedom

of the subject and to whatever lengths the subject in general ma

$62 20 alsojmay (the journalisetacat deel the statute law, his

Privilege is no other and no higher... No privilege attaches

his position.*

3. Ramlila Maidan Incident, re, (2012) 5 SCC 1, 31, para, 1,

4- Constitution of India, Preamble,

5. Fundamental rights

those basic rights th:

ais

n of India (Part [IT of the Constit

‘at arerecognised and

Buaranteed as the natural rights

in the status of a citizen of a free co

under the Constitutios

(2004) 1 SCC 712, 738-39, para. 3

Channing Arnold v. King Emperor,

CONSTITUT

ONAL FOUNDATIONS 3

1]

nework for analysing media rights remains much the same

rhe frame ‘ , : 7

The tea ependence India, In M.S.M. Sharma v, Sri Krishna Sinha?

in pos

plight), the Supreme Court observed:

(searchlight),

| non-citizen running a newspaper is not entitled to the funda-

aental right to freedom of speech and expression and, therefore

vanot claim, as his fundamental right, the benefit of the liberty

of the Press. Further, being only a right flowing from the freedom

of speech and expression, the liberty of the Press in India stands,

on no higher footing than the freedom of speech and expression

of a citizen and that no privilege attaches to the Press as such,

inct from the freedom of the citizen. In short,

that is to say, as dis

as regards citizens running a newspaper, the position under our

Constitution is the same as it w4s when the Judicial Committee

decided the case of 41 Ind App 149: (AIR 1914 PC 116) and as

regards non-citizens the position may even be worse.’

In other words, the media enjoys no special immunity or elevated status

compared to the citizen and is subject to the general laws of the land,

including those relating to taxation.” However, in post-independent

India both the citizen and citizen-owned media enjoy a constitutional

guarantee that was hitherto absent.

Comparisons with the US Constitution

Article r9(1)(a) finds its roots in the rst Amendmentto the US Constitution.

The 1st Amendment read

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of

religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging

the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the peo-

ple peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a

redress of grievances,”

Unlike the rst Amendment to the US Constitution, the Indian Constitution

does not make a specific or separate provision for the freedom of the

Press. Further, while the restrictions on the right to freedom of speech

and expression are expressly spelt out in Article r9(2), this is not so under

the 1st Amendment,!! The US Supreme Court has read into the rights of

the press certain implicit restrictions which are, in principle, no different

7. AIR igs

8. Ibid, (A\

9. On tax

10, USC

9 SC 395: 1959 Supp (1) SCR 806.

IR) 402, para, 13.

ation and the media, see, Chap. 15 titled “Taxation”.

Te ln Qaetitution, 1st Amendment, Art, 1,

held sho Of India v. Naveen Jindal, (2004) 2 SCC 510: AIR 2004 SC 1559, it was

ld that while the rst ‘Amendment in the US Constitution gives an absolute right of

™ of expression to the citizen, in India, there is only a qualified right regulated

Festrictions in Art. 19(a). See, (SCC) 547-48, para. 7.

freedoy

y the

4 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

from Article 19(2).!” However, generally,

standpoint, the freedom of the press in Am

the corresponding Indian guarantee.

from a jud)

erica is far

cial d

Nore top

The question of whether or not fo insert in th

Separate right for the press, as distinct from that

Was extensively debated by the members of the Constitueng 4

The Constituent Assembly came to the conclusion thar such q

Was not necessary. Dr B.R, Ambedkar, Chairman of the G

Assembly’s Drafting Committee argued;

Indian

Conse,

of the ording

The press is merely another

citizen. The press has no spec

or which are not to be exerci:

capacity. The editor of a

and therefore when they

way of Stating an individual or.

lal rights which are NOt tO be piven

sed by the citizen in his individ

Press or the manager

choose to write i

press at all!

Although no special Provision w,

Press, the courts have time and

Press are implicit in th

under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution,

of the Supreme Court of India have sf

freedom of the press and have echoed

Amendment.

Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras's (

the earliest cases to be decided by the Sup

lenge against an order issued by the G

Section 9(1-A),

12. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting,

Bengal, (1995) 2 SCC 161: AIR 1995 SC 1256,

'3- Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol. VIl, 780, 2 ae

14: Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi, AIR 1950 SC rag: (1950) 5x Cal

Newspaper (P) Ltd. v. Union of India, AIR 1958 SC 578: 359

(P) Ltd. v. Union of India, AIR 1962 SC 305: (1962) 3 . "a aad

© Co. v. Union of India, (1972) 2 SCC 788: AIR 1973 SC 1 *

Union of India, (1978) x SCC 248: AIR 1978 SC 597. .

15. AIR 1950 SC 124: 1950 SCR 594.

Gout. of India v. C

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 5

y and public order, fell outside the scope of the reasonable restric-

« permitted under Article 19(2) and was held to be unconstitutional.

i, Bri Bhushan vy. State of Delhi'® (Brij Bhushan), the Supreme Court

shed a pre-censorship order passed against the publishers of the

The order was sed by the authorities under Section 7(#)(c)

of the East Punjab Safety Act, 1949. The court held that Section 7(#)(c)

which authorised such a restriction on the ground that it was “necessary

for the purpose of preventing or combating any activity prejudicial to the

public safety or the maintenance of public order” did not fall within the

purview of Article 19(2).

The strongest affirmation of the spirit of the 1st Amendment is echoed

in Express Newspapers (P) Ltd. v. Union of India.” This case arose

out of a challenge to the Working Journalists and other Newspaper

Employees (Conditions of Service) and Miscellaneous Provisions Act,

195s, on the ground that its provisions violated Article r9(x)(a). In the

facts of the case, the court held that the impact of the legislation on the

freedom of speech was much too remote and no judicial interference was

warranted. However, the court did recognise an important principle:

satet

qua

Organiser.

Laws which single out the press for laying upon it excessive and

prohibitive burdens which would restrict the circulation, impose

a penalty on its right to choose the instrument for its exercise or to

seek an alternative media, prevent newspapers from being started

and ultimately drive the press to seek Government aid in order to

survive, would therefore be struck down as unconstitutional.'*

The freedom of the press is part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

In [.R. Coelho vy. State of T.N.,!° a Bench of nine judges of the Supreme

Court examined the question of whether on and from the date on which

the decision in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala*® (Kesavananda

Bharati) was delivered (in which the Supreme Court enunciated the basic

structure doctrine), it was permissible for Parliament to immunise legis-

lations from being struck down for violation of fundamental rights by

inserting them into the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution. In this con-

text, the court reiterated that although the freedom of the press was not

separately and specifically guaranteed under the Constitution, it had to

be read as part of Article 19(1)(a). The freedom of the press formed part of

the basic structure of the Constitution. It was held that if Article 19(1)(a)

Was sought to be amended so as to abrogate the freedom of the press, and

the amendment fell outside judicial scrutiny by placing the law curtailing

" Ne 1950 SC 129: (1950) 5x Cri LJ 1525.

Th TA 1998 SC 578: 1959 SCR 12,

- Ibid, (AIR) 617, para. 150.

ee (2007) 2 SCC 1: AIR 2007 SC 861.

©. (1973) 4 SCC 225: AIR 1973 SC 1461.

6 PACETS OF MEDIA LAW

these rights in the Ninth Schedule, such an abridgement

the freedom of the press and, thus, be destructive of the by.

In Ramlila Maidan Incident, re,? which arose

midnight attack by the police on peaceful prot

the Supreme Court drew a comparison bet

Would,

ASIC sty

out of an un,

sters ata publig

tween the Ist Amend

its counterpart under the Indian Constitution. The court held 4

h

under the US Constitution where the Ist Amendment confers anal

right inasmuch as the Congress can make no law abridging the fr

of speech, press or assembly, “it has long been established thar

freedoms themselves are dependent upon the power of the constitu,

Government to survive. If it is to survive, it must have Power to p

itself against unlawful conduct and under some circumstances

incitements to commit unlawful acts. Freedom of speech, thus, do

comprehend the right to speak on any subject at any time.” Free g

may be restricted under the “clear and present danger” test. The

cited Schenck v. United States:

[T]he character of evi

which it is done.

Act depends upon the circumstances in

The most stringent protection of free speech

would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater, a

causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injun

tion against uttering words that have all the effect of force...

The question in every case is whether the words used are used i

such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear:

and present danger that they will bring about the substantive

evils that Congress has a right to prevent.2

In a later judgment, the Media Guidelines case,?° a Constitution

of the Supreme Court, considering whether to impose guid

reportage of court cases, felt it necessary to emphasise the diffe

between the rst Amendment under the US Constitution and the free

of speech under the Indian Constitution:

The First Amendment does not tolerate any form of restrail

In US, unlike India and Canada which also have writt

Constitutions, freedom of the press is expressly protected as

absolute right. The US Constitution does not have provisi

similar to Section 1 of the Charter Rights under the Canad

- LR. Coelho vy, State of T.N., (2007) 2 SCC 1, 100, para. 106: AIR 2007 SC

. (2012) 5 SCC 1,

. Ibid, 30, para. 5.

. 63 L Ed 470: 249 US 47 (1919).

. Ramlila Maidan Incident, re, (2012) 5 SCC 1, 5, para. 6, See also, Sal

Estate Corpn. Ltd. y. SEBI, (2012) 10 SCC 603: AIR 2012 SC 3829.

. Sahara India Real Estate Corpn. Ltd. v, SEBI, (2012) 10 SCC 60

3829.

CONS

ITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 7

recess, report and comment upon ongoing trials is prima facie

unlawful. Prior restraints are completely banned, If an irrespon-

sible piece of journalism results in prejudice to the proceedings,

the legal system does not provide for sanctions against the parties

responsible for the wrongdoings. Thus, restrictive contempt of

court laws are generally considered incompatible with the consti-

tutional guarantee of free speech.”

Facets of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a)

‘The freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) is a concept

with diverse facets, both with regard to the content of the speech and

expression and in the means through which communication takes place.

It is also a dynamic concept that has evolved with time and advances in

technology.

Briefly, Article 19(1)(a) covers the right to express oneself by word

of mouth, writing, printing, picture or in any other manner. It includes

the freedom of communication and the right to propagate or publish

one’s views. The communication of ideas may be through any medium,

newspaper, magazine or movie, including the electronic and audio-visual

media.”*

Right to circulate

The right to free speech and expression includes the right not only to

publish but also to circulate information and opinion. Without the right

to circulate, the right to free speech and expression would have little

meaning. The freedom of circulation has been held to be as essential as

the freedom of publication.2?

In Sakal Papers (P) Ltd. v. Union of India (Sakal Papers), the

Supreme Court held that the State could not make laws which directly

affect the circulation of a newspaper for that would amount to a viola-

tion of the freedom of speech. The right under Article 19(1)(a) extends

not only to the matter which the citizen is entitled to circulate but also to

the volume of circulation."! Sakal Papers arose out of a challenge to the

newsprint policy of the government which restricted the number of pages

4 Newspaper was entitled to print.

27. Ibid, (SCC) 713, para. 17.

28.8. Rangarajan v, P, Jagjivan Ram, (1989) 2 SCC 574.

29 Romesh Thappar v, State of Madras, AIR 1950 SC 124: 1950 SCR s943 Virendra v.

State of Punjab, AIR 1957 SC 896: 1958 SCR 308; Sakal Papers (P) Ltd. v. Union of

India, AIR 1962 SC 305: (1962) 3 SCR 842.

39: AIR 1962 SC 305; (1962) 3 SCR 842

3: Ibid, (AIR) 313, paras. 33-34.

8 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

Likewise, in Bennett Coleman & Co,

Coleman), the Supreme Court held that n

to determine their pages and their circula

challenge to the constitutional validity of t

Act, 1956 which empowered the govern:

of space for advertisement matter, The c

advertisements would fall foul of Articl

direct impact on the circulation of news,

testriction leading to a loss of advertising revenue would affect

tion and thereby, impinge on the freedom of speech.34

In Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) (P) Ltd. y, Union of |

(Indian Express Newspapers), a challenge to the im,

toms duty on import of newsprint was allowed and

struck down. The Supreme Court held that the expression “freed

the press”, though not expressly used in Article 19,

Was comprehend

within Article 19(1)(a) and meant freedom from interference from auth

ity which would have the effect of interference with the content

circulation of newspapers.°*

In LIC v. Manubhai D, Shah*? (,

v. Union of Indign jy

ewsPapers should bel

tion. This case arog

he Newspaper (Price g

ment to regulate the a

ourt held that the curtaj

le 19(1)(a), si

Papers.»> The court held

POSition of

the impug;

Manubhai D. Shah), the Sup

Hon and any attempt to stifle or suffocate or gag this right would

sound a death-knell to dem,

ocracy and would help usher in autoc:

racy or dictatorship.

The court held that am

Propagation of ideas m

mischief of Article 19(2),

The right to circulate encompasses the right to determine th

of circulation.2

32. (1972) 2 SCC 98g, 4

33 Ibid, (SCC) 824, Par:

IR 1973 SC 106,

a. 82,

34- Ibid, (SCC) gy

AIR 1962 $C 305.

on 305: (1962) 3 St

- Of Indiay, Cri eng

Agnes aea a ‘AV. Cricket Assn, of B

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 9

|

Right © dissent a

srance by Government of a dissident press is the measure of the

aa of the nation”."” Freedom of speech and expression covers the

a riticise the government, which is the pre-requisite of a healthy

a The draft Constitution proposed that laws penalising sedi-

Be would be an exception to free speech, The word “sedition”, defined

‘i draft Article 13(2) as “exciting, or attempting to excite in others certain

had feelings towards the government and not in exciting or attempting,

to excite mutiny or rebellion, or any sort of actual disturbance, great or

small”, was deleted from Article 13(2) of the draft Constitution [eventu-

ally passed as Article 19(2)]. In Romesh Thappar," the Supreme Court

noted that the deletion made it clear that the authors of the Constitution

intended that of the government was not to be regarded as a ground for

restricting the freedom of speech or expression,

Ina leading American case, Terminiello v. Chicago, which has been

frequently cited by Indian courts, the rationale behind the freedom of

speech was explained:

[A] function of free speech under our system of government is to

invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it

induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with con-

ditions as they are, or even stirs the people to anger. Speech is

often provocative and challenging, It may strike at prejudices

and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it

presses for acceptance of an idea... There is no room under our

Constitution for a more restrictive view for the alternative would

lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts or

dominant political or community groups.”

Kedar Nath Singh v, State of Bibar“ (Kedar Nath Singh) arose out of a

constitutional challenge to Sections 124-A and 505, Penal Code, 1860

(IPC), which penalise attempts to excite disaffection towards the govern-

ment by words or in writing and publications which may disturb public

tranquillity. The Supreme Court dismissed the challenge but clarified that

Criticism of public measures or comment on government action, however

strongly worded, would be within reasonable limits and would be con-

sistent with the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression.

40. Douglas J in Terminiello v. Chicago, 93 L Ed 1131: 337 US 1 (1949).

41. AIR 1950 SC 124: 1950 SCR 594.

42-93 LEd ri3x: 337 US 1 (1949). A‘

3. Terminiello y, Chicago, 93 L Ed 1131, 1134: 337 US x (1949); quoted with approval

by Jeevan Reddy J in Printers (Mysore) Ltd, v. CTO, (1994) 2 SCC 434, 441-42

Para. 13; also referred to in Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of

India v. Cricket Assn. of Bengal, (1995) 2 SCC 161: AIR 1995 SC 1236.

44- AIR 1962 SC 955: (1962) 2 Cri L] 103.

10 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

In Directorate General of Doordarshan

(Anand Patwardhan), the Supreme Court hel

prevent open discussion, no matter how hatefu

In Anand Chintamani Dighe v. State of M,

of the Bombay High Court, while quashing an order of fo,

Section 95(1), Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (CrPC) j

Nathuram Godse Boltoy”, a play critical of Mahatm.

the right to criticise:

Vv. Anand a

Id that the 5,

1 to its Policies

aharashtya,s7 a

Tfeitur,

Tolerance of diversity of view points and

freedom to express of those whose thinkin,

the mainstream are

the acceptance of rf

ig, Mz

cardinal values which li

sage. Popular Perceptions,

ues which the constitution

what was always intended

however strong cannot override yal-

embodies as guarantees of freedom in

to be free society,*®

Criticism of a government me

cannot be regarded as miscon

Punjab,” it was held that

, ultra vires or against th

cussion on the subject. The court

¢ Hamlyn Lecture on “Freedo

der the Law, who said:

Everyone in the land should be free to think hi

have his own opinions and to give voice to tl

Private, so long as he does not speak ill of hi

interest, and could invite a dis

Sir Alfred Denning LJ from th

and Conscience”, Freedom Un

is own thoughts

hem in public 0

neighbour and ff

i

45. (2006) 8 SCC 433: AIR 2006 SC 3346. : .

46. Ibid, (SCC) 448, Para. 42.

47. (2002) 2 Mah L} 14.

48. Ibid, 32-33, para, 19,

49. (2002) 3 SCC 667: AIR 2002 SC 1124,

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 11

icize the Government or any party or group of people,

also to crit g

‘ he does not incite anyone to violence.

so long as

shboo v. Kanniammal,”' the Supreme Court upheld the right of

dual to hold unpopular or unconventional views. The case arose

f criminal complaints that were filed against film-star Khushboo for

a _ on pre-marital sex in urban India. She was quoted in a news mag-

es have noticed increased pre-marital sex and live-in-relationships

Bich she felt, warranted societal acceptance. She was reported to have

ie id that girls ought to take necessary precautions to prevent unwanted

pregnancies and the transmission of venereal diseases. The publication of

these remarks is said to have outraged people in Tamil Nadu. Soon sev-

eral criminal complaints were filed against Khushboo by individuals and

organisations under Sections 292, 499, 500, 504, 505(r)(b) and (c), 505(2)

and 509 IPC read with Sections 3 and 4, Indecent Representation of

Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986. Khushboo failed to get the complaints

quashed in the Madras High Court. The Supreme Court came to her

rescue and held that the complaints were not only mala fide but failed

to make out allegations which could amount to defamation, obscenity

and the like. The court upheld the freedom of speech under Article r9(r)

(a) and expressed the need for tolerance even for unpopular views. The

court held that notions of social morality are inherently subjective and

that criminal law could not be used as a means to interfere with the

domain of personal autonomy.

In F.A. Picture International y. Central Board of Film Certification

(F.A. Picture International), the Bombay High Court observed in the

context of film censorship, that dissent is the quintessence of democracy:

ins. Khu

iheindivi

Artists, writers, playrights and film makers are the eyes and the

ears of a free society. They are the veritable lungs of a free soci-

ety because the power of their medium imparts a breath of fresh

air into the drudgery of daily existence. Their right to communi-

cate ideas in a medium of their choosing is as fundamental as the

right of any other citizen to speak. Our constitutional democracy

guarantees the right of free speech and that right is not condi-

tional upon the expression of views which may be palatable to

mainstream thought. Dissent is the quintessence of democracy.

Hence, those who express views which are critical of prevailing

social reality have a valued position in the constitutional order.

History tells us that dissent in all walks of life contributes to the

evolution of society. Those who question unquestioned assump-

tions contribute to the alteration of social norms. Democracy is

founded upon respect for their courage. Any attempt by the State

50. Ibid, (SCC) 673, para. 11.

51. (2010) 5 SCC 600: AIR 2010 SC 3196.

52. AIR 2005 Bom 145.

12 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

Jamp down on the free expression of opinion must hence

to cle

FA

frowned upon.

, Technology v. Central p

srishti School of Art, Design and oe

Reed (Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology) 4

relating to film censorship, the Delhi High Court held:

One may agree or disagree with the filmmaker’s position but th

issue is whether she has a right to express her point of view irre

spective of its ‘acceptability’ to the viewer or for that matter to the

CEBC or the FCAT. To recall the lines from the famous dissent of

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in United States v. Schwimmer,

L Ed 889: 279 US 644 (1929) (at 655): “.. if there is any principle

of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment

than any other it is the principle of free thought—not free thoup

for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we

hate.’ The constitutional framework of the freedom of speech and

expression as enshrined in Article r9(1)(a) of the Constitution

provides democratic space to a citizen to put forth a view which

may be unacceptable to others but does not on that score al

become vulnerable to excision by way of censorship.*°

In the same judgment, the court quoted these lines from an Americ:

ment, “Surely the State has no right to cleanse public debate to th

where it is grammatically palatable to the most squeamish among

Right to portray social evils

The freedom of expression envisages not merely the depiction of

good but extends to the portrayal of social vices. How else wot

ist be able to convey to his audience the ills that plague society and

an attempt to redress the malaise? In Anand Patwardhan,”” Door

had refused to telecast an award-winning film based on the

munal violence on the ground, inter alia, that the film depicted

and communal hatred which could cause social unrest. The

Court upheld the right of the film-maker to have his film t

Doordarshan and observed: 5

In the present matter, the documentary film Father, Sona

War depicts social vices that are eating into the very foundatio

our Constitution. Communal riots, caste and class issues ani

lence against women are issues that require every citizen

tion for a feasible solution. Only the citizens especially the y

of our nation who are correctly informed can arrive a

rect solution. This documentary film in our conside

53. Ibid, 148, para. 7,

54. (2011) 178 DLT 337: (2011) 46 PTC 221,

55. Ibid, (PTC) 231, para. 17,

56. Harlan J in Cohen v, California,

57- (2006) 8 SCC 433: AIR 2006 SC

,

29 L Ed 2d 284: 403 US 15 (1

3346.

| CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 13

I

showcases a real picture of crime and violence against women

and members of various religious groups perpetrated by politi-

cally motivated leaders for political, social and personal gains.

This film so far as our opinion goes does not violate any con-

stitutional provision nor will create any law and order problems

as Doordarshan fears. This movie falls well within the limits pre-

scribed by our Constitution and does not appeal to the prurient

interests in an average person, applying contemporary commu-

nity standards while taking the work as a whole, the work is not

patently offensive and does not proceed to deprave and corrupt

any average Indian citizen's mind,

In Mahesh Bhatt v. Union of India,* the Delhi High Court struck down

rules under the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of

Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production,

Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003 which sought to impose a blanket

ban on the depiction of smoking in films. The court upheld the right of

the film-maker and the artist to use his medium to project life in all its

hues, its foibles included. Following the test in K.A. Abbas v. Union of

India® (K.A. Abbas), the court held that the depiction of social evils

as severe as rape, prostitution and the like, cannot be censored. Rather

what has to be seen is how the theme is handled by the film-maker.

In Bobby Art International v. Om Pal Singh Hoon," the petitioner

sought the censor of scenes of frontal nudity showing Phoolan Devi (a

rape victim who later became one of India’s most dreaded dacoits), being

paraded naked before the village folk after days of being gang raped.

Rejecting the challenge, the Supreme Court held:

The rape scene also helps to explain why Phoolan Devi became

what she did. Rape is crude and its crudity is what the rapist’s

bouncing bare posterior is meant to illustrate, Rape and sex are

not being glorified in the film. Quite the contrary, it shows what

a terrible, and terrifying, effect rape and lust can have upon the

victim. It focuses on the trauma and emotional turmoil of the

victim to evoke sympathy for her and disgust for the rapist.

In F.A. Picture International,® another case of film censorship, the

Bombay High Court held:

Films which deal with controversial issues necessarily have to

portray what is controversial, A film which is set in the backdrop

of communal violence cannot be expected to eschew a portrayal

of violence. The producer of a film on the second World War

cannot be true to his conscience if the horrors of war are not

58. Ibid, (SCC) 446-47, paras. 34-35.

59. (2009) 156 DLT 725.

60. (1970) 2 SCC 780: AIR 1971 SC 481.

61. (1996) 4 SCC 1: AIR 1996 SC 1846.

62. Ibid, (SCC) 15-16, paras. 27-28.

63. AIR 2005 Bom 145.

beh a pier as much for moving deel

2 cote is of te period a8 much a5 in the abi gh

vito find humor in the lives of those on the verge of eget

So ec The diccior ler ee

so, Sate humo aed he ees ee

retell Sock of cise whneea i a

In K.A. Abbas the Supreme Court held that the portrayal of

vice could not by itself attract the censor’s scissors, “Therefo

the elements of rape, leprosy, sexual

re

morality which should at

Right to portray histori

I events

In F.A. Picture International,” the Bombay High Court held:

depictions of artistic themes. Artists, film makers and playrighe

are affirmatively entitled to allude to incidents which have take

place and to present a version of those

to them represents a balanced

that the violence which took plac:

censor’s scissors but how the theme is handled by the producer™

tis

incidents which according

Portrayal of social reality. To say.

n the State of Gujarat i alive

and a ‘scar on national sensitivity’ can furnish absolutly

no ground for preventing the exhibition of the film. No democ-

racy can countenance a lid of suppression on events in society

The violence which took place in the

State of Gujarat has been

the subject matter of extensive debate in the press and the media

and itis impermissible to conjectui

that a film dealing with

issue would aggravate the situation. On the contrary, stability in

society can only be promoted by introspection into social re

however grim it may be. Ours, we believe, isa mature democracy

‘The view of the censor does no credit to the maturity of a demo

cratic society by making an assumption that people would be le

to disharmony by a free and open display of a cinematoge

64. Ibid, 149, para. 12

65. K.A: Abbas v. Union of India, (1970) 2 SCC 780: AIR 1971 SC 4

66, Ibid, (SCC) Ho2, para. so; se also, Srshti School of Are, Design ad Te

Central Board of Film Certification, (201 DLT (2011) 46 PTC;

17. AIR 2005 Bom 14s. 7a £

ity

1

a historical event and

im-maker has the right to present

a oe ofthat event may revive tensions or open up old

a insorship. In Srishti School of Art, Design

wer Technology,” the Delhi High Court struck down excisions of the

film, Had Anhad, cartic

‘The excisions to the film,

merely becaus

wounds is not a ground for cer

incror i ict co eel life personalities. The consti:

hich eat ider Article 19(1)(a) that a film al ee

a ot ea onthe premise shat he must depict somethOg

is noncone eaaeea \¢ choice is entirely his. Those w!

nuh 16 2627 persone of demoxtacy andthe power ofthe

appraisal tiga of expression lies in its ability 10 contribute

.d out by the Central Board of Film Certification.

sj the ensuing communal riots, were sought to be justified on

MEMGind hae the events were histor) and best forgotten, lest they

fe. The court upheld the right of the film-maker to por-

tray a historical event, even if it distorts the State’s version of reality:

168 Ibid, 150, pa

69. (2088) 178 Dl

Gervion.w_obliicrate the” seenea a tea] /S [ef ee nea Te

sah lea Tal asa i de

the German Army smoagingsbpets ony boa HR

between the Ger eee eed ened

"rman soldier arresting a child and the Iseaeli sol-

‘let acresting an Arab youngster breaks my heart. Nonetheless,

a <<

397: (2081) 46 PTC a4,

a

1

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 15

which recounts the demolition of the Babri

fate

16 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

we live in a democratic state, in which this hy

heart of democraey! ’ leartbr pITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 17

Later in Bakr v. Film Censorship Bo,

249, this aspect was revisited. The a cog

censored —‘Jenin, Jenin’—presented the Palen

tts battle A i Jenin refugee camp in stn

ae efensive Wall’, The film maker at the oe. :

that he had made no attempt to present the Israsiy et or ia de possible, the

Israel sf seconds.

‘id in a matter o}

tensor Board banned the film since it Hi po

sel Sopra any P ott an Indian citizen's igRE IO freedom of speech

S ny Wds beyond the geoerap! I limits of India, was con-

‘offensive to public’s feelings’. The Isr:

the Board. Justice Pees pak a Coded ie eS,

messages of the film Jenin, Jenin, court obsery ‘Court in Maneka Gandhi v. inion of India.”

message of Oe Un en cart eo Section 10(3)¢h Passport Act) 1967

film could not be banned because Ree and “to be impounded “in the interests of the gen-

wo feat does nor feach the’ hehe Rae the inju ghe challenge was that the provision infringed

old required to Thad the petitioner from exercising her right

broad, The court considered whether

sritory, and whether sucha right

freedom of speech .... the offense is no

fense is not radic E

pt of posing coe threat th Bere

might justify restricting freedom of e: ina

iy? Commenting on this decider legal schclaeE ie 11 ave been woke in the Breen CO The court held

Ber points ou thatthe Court should pethaps es Bowe freedom of speech and expresio Wvas not confined to national

offense to feelings caused by such films bur vail ea E poundaries and a citizen had the right to exercise that right abroad. The

the censor Board's decision ‘because of the Gaiam oun perved thatthe authors ofthe Const HOT hhad deliberately cho-

Peer te inte che custodian of uta an cour ro ase words confining the ight By ‘efraining from the use of the

In Central Board of Film Certfic se ory of India” athe end of Arie 1918 Acaround

that the Se in Cortfcaion et a word in Consration was brought into fore the constitutional

thane igoronmtion oa Eto Seal film based Ao ihe Universal Declaration of Human Rights Was underway

to censor the film. The Madras High debate AT article 15 ofthe Universal Declaration reads

the ban on the film whic

the film which was based on the assassination of| very one has a right co freedom of opinion and expresses this

fight includes freedom to hold opinions without interference

a poet recewe and impart information and ideas through

and ia ad regardless of frontiers) aiemptassuPtll

It was argued on behalf of the government that the right under

‘Arvicle 19(xa) could not be extended beyond Indian terror), since the

al ai ft protect the enforcement of the fundamental ight ee

Speech in a foreign country. The court rejected that argume™ and reco8

rent in technology and com

mused that on account of the vast improvem

‘while in India, could transmit information t0 2

contexts—from advertiseme:

mation adver enabling the citizen to get fe country and in the process exercise her right ro free ‘expression

” fe-saving drugs,” to the right of lover abrond, which if restricted by the State, would amount f0 a0 infringe

Ge catleite 1 right of sports lo I, stricted by the State,

1” and the right of voters to know the ee 0 ment of Article 19(1)(a). Similarly, the court “observed that the right t0 g0

abroad had already been recognised by the Supreme ‘Court as being part

ndidates.7

ibid OG eae ee aed

(2007) 1 CTC i Tndian Express Newspapers (Bombay) (P) Lt. «Union of India (985) 1 SCC 64,

Indien Expres Newt on of ee Se

See, Chapig tiled “1

9 titled “The Right to

ee oe 149; Reliance Petrochemicals Lt press Newspapers Bomb (2) Lide

aly Teed v Union of Indi 1997) 4

Tvon of indi, (2003) 4 SCC 3995

cons!

‘onal boundaries

in transcends national boundaries. The revolution

te electronic media has broken down tradi-

he transmission of information t0

jon beyond nati

pet publi’. One aspect

a Cele s9(t)a) since it Pree

ree speech and expression ¢

tial x9(z(a) was confined £9 Indian te

words

to receive information.

‘of judgments w

judgments which have discussed the right to informatie qyunications, 2: nea

Tata Press Led

Ad. v. MTNL, (1

995) 5 SCC 139, [ay88) 4 SCC sya: AIR 1989 SC 1995

.aj Narain, (1975) 4 SCC 428: Al

Minty of inomaton

ena 99912 SCC aa

Union of India y. ia :

111. See erly

" 1s oF MEDIA LAW

1s 18ce

onal liberty under Article 21,7 a cea

ght to persona > thus, ITUTIONAL FOUNDAT!

ofthe a nad not been confined (0 the ter ome

ote ona passage from an article titled, The Gog ‘ournalist. Consequently, there

cot py Leonard B Boudin 5 2 ie a quoted with to carry on her Pe i

to Travel rt in $.S. Sadashiva Rao v, Yn ech of ent of Article t

fo rraka High Cou - Unig fringe

Karnataka sage reads: Aas ni ,

teract from eat asses interviews

to conduc “

Pres abject to the willing consent ofthe person being

Hep cases have arisen where the right ofthe press

mbet

amr under trials has been examined:

nal objection co limitations upon the

ight

fece withthe individual’s freedom of expeed

f express

the inte Pre

ey ch a freedom in the view of one scholarly 7

We us Juris

wee need not go that far; itis enough that the Free 1 king to inter-

isthe rit of Americans f0 exercise tanya pie na Dust. Union of it Pe court held that the

f their government. There are ree condemned prisoners Billa ans 5

Mer the Bill of Rights. A Government etapa je the core elute or unrestricted right ro information and

limi E he part of citizens to supply that informa:

hat set does not

tient freedom of expression in up fess 2 ee

fen vite te Constatio sh ucha te ae fea conducted provided the convict gives his con-

gers sated oa tee ged he ight interview would also be subject

1 Orie al forthe Superintendence and Management of

‘he cur ako examined whether the right to go abroad, SE) Oh a er deh ENE

be part ofthe fondant ais, which allows eons with relations, legal advisors, ete. as the Jail

heldthat although going abroad ray be necessary in a gneg ge in commmepsiders reasonable. The court held ehat where there

exercise ofthe right to free speech, that could not elevate itty Fae ie avons to do so, the interview can be refused, although

ofan nega part ofthe fundamental right to fre speeia re wei unt tobe recorded in writin, The Supreme Court took a

tae z ie Tar view in Sheela Barsev. State of Maharashtra.®

Mae x. Chardata Joshi.” the Supreme Court reiterated the

seauoted scope ofthis right. The Additional Sessions Judge had granted

sre magacine, India Today, blanket permission to interview Babloo

ight of the

The

nited right, su!

the interference 0}

Every activity that may be necessary for exercise of fre

speech and expression or that may facilitate such exere

make it meaningful and effective cannot be elevated to

tus of a fundamental right as if it were part of : Srivastava who was lodged in Tihar Jail. The court held that the under-

Ser fe aa ae ce : rt of the fundan rial could be interviewed or photographed only if he expressed his will-

oe incre irc aay Jngness. The interview had to be regulated by the provisions contained in

other and the object of making certain rights aa ial fhe Jail Manuals and could be published in a manner that did not impair

mental rights with different permissible restrictions Bie administration Of stg

frustrated."

Reporting court proceedings

SaInU aoe ee n Although, in principle, the press enjoys no higher status than that of the

ee a a passport would violate dl ordinary citizen, in practice, it does. Ordinary citizens are not allowed

Pression. Thus, in a case where a person free access in the way the press does, as for instance, they do not enjoy

overseas for the purpos

eed the purpose of expressing herself in whatever ¥ the privilege of sitting in the Press Bench as journalists do.** The press

The test laid down by the court was whether the direct and

fa; ee music, dance etc., the impounding of joys privileges on account of the citizen’ right to be informed on mat-

peers effect on her right to free expression rs of public importance.

an rent of her rights under Article 19(1)(a), ed Donaldson in Attorney General v. Guardian Newspapers Ltd.

le ca tore the c¢ . (No. 2)" I:

ieee ‘ourt, there was nothing on record t fo. 2)" observed:

was seeking to g

as secking to go abroad for the purpose of exe 81. (1982) SCC 1: AIR 1982 SC.

ria ele 98) «SCC 3s,

77 Sutwant Singh Sawhney v. Passport Off; 3: (1995) 4 SCC 65: AIR 1999 SC 1

7 LesaidB Boudin, The Contturocs ie Te a, See, Cp. 1 led" Rerorting [ol epee age

P96) Mis Los ‘ional Right to Travel, (1956) Co L: 85. (1990) 1 AC 109: (1988) 3 WLR 776: (1988) 3 AIL ER 545 (HL), 600

laneka Gandhi v. Union of Ind and N. (Minors) (Wardship: Publication of Information), re, 1990

tia, (1978) 1 SCC 248: AIR 1978 SC §

egeeh

20 FX

cers OF MEDIA LAW

quse of any special wisdom,

cs Toy or journalst haa a

ves of the general public. They act

the lc. Ther nt to know and thie

+ ress than that of the gene

ral public for whom they are cl

Ss,

Iris not be

ITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 1

const

by propriet

eal Estate Corpm: Ltd. ¥ SEBIy" a Constitution

Ret art ee tas a presumption

Mand the media's Tight £0 SPOR cases im exCEP-

amtjets had the poste £0 “POS reportage

Re interest of justice. Orders of postponement

‘and proportionality:

para India

either more

that of the gene

4 fundamental right to a

tte

blish a faithful report of he eee

This right is available in respect Bema

ore

Jud

} duration i

ject 10 necessity

The journalist has

and the right to pul

and heard in court

judicial ribunals

The right to report judicial proceedings stem:

from the

1e ny

crpapareneyfastice must not only be done, it must be

Gpemesis a safeguard against judicial error and my seer

haw in Scott v. Scott’” quoted Bentham, “Pas

» “Public

ceedings

Reportiny

rhe right 10 £ePOrt proceedings of Patlia

hehe publics right ro Pe informe:

w sentatives on matte

legislative PF

ment and the State ‘Assemblies

.d about the debates and delib-

ers of public importance.”

Lord St

soul of justice. It is the keenest spur to exertion

mn, and: s of its el

so pxmprobiy Te keeps the judge himself while ti sco ei ns at Oa ‘here is no liability in respect

tying under Ute publication of 2 Substantially true report of Parliamentary pro-

Heafose of the State Assemblies $0 Jong, as the publication is

Publicity of proceedings Serves another important purpos

.

tained in Parliamentary

knowledge and appreciation of the working of the | ceedings ©"

e

untainted by ar provision is com

sublication) Act, 1977.”

‘malice. A simi

(Protection of

public

administration of justice. There is also a th

so a therapeutic vah

in seeing criminal trials reach their log alue to Proceedings

ir logical conclusion.’* “The right to report legislative proceedings has often been curtailed in

Trae privilege available to both Parliament and the State

ts conferred by the

the name of legis!

Assemblies. Legistative privile

se otion on Parliament and the Sits Legislatures to ensure freedom

St speech for the legislators © ‘enable them to discuss and debate matters

eee fear of inviting liability of any sore!

ublicised. It is not only neces

publicised. It is not only necessary to protect such persons of importance W

i erme Court in Te) Kitan Jain y. Ni San Reddy" observed:

government that

Publicity of proceedings is not an absolute rule. The o

ee oie say when there 2i¢ higher) eee ge refers to special

. Fo

the names of rape victims or riot victims must be protected. §

ed.

humiliation b

saa Fe embarassment, but also necessary to ensure t

et e best available evidence-which she may not “4 tris of the essence of parliamentary SYSTEM

pete a te Pale gee Sin We represenatives should be fee to Ps themselves

ui ‘putes Mrithout fear of legal consequences: “What they say is only subject

srvedes of Parliament, the good sense of

to the discipline of the

the members and the control of pt

tec have no say in the matter and should ea

Commonly cecognised privileges includes

The privilege of the freedom of

proceedings.

1 publication of legislative proceedings

2. The right to control

+ The right ofeach House to be the sole udge ofthe lawfulness of ts

‘own proceedings.

44. The right of the

Parliament.

roceedings by the speaker. The

privacy, partic

particularly to protect children from unwarranted publ

ly have none.

ests of justice”, The o

Givil Procedure ee ny inherent: powet oii

Pe eae PC) to order a trial ie

tn mt canal penn a ot oe

cours saisfid beyond doubt that the y

the ease wee tobe tried in open ea of justice would bed

1

House to punish members for their cond in

7 WR Ge) AN

Saroj Iyer v. Maharas| a ie

1913 AC 417: (19111 wi

205 CA)

ical Council of Indian Medicine, AIR 20028

hridbar Mijkor Siena Ree. (HL)

for. Slate of Mak ce 3 sored, with, apEaTaME

rashtra, AIR 1967 SC 1 Samarias IR 2012 SC “

gu (orn) 10 SCC 6oy: AIR 2012 SC 3295 he uate Asem

rand the State .

I Ld. v5

4 mie, 198.

ion of India 4) 4 SCC 666: Al

8. Rerter Singh Aeon SCC 226: A I 1985 SC 61. Also see, Vineet NG

AIT pera Sat of Pia AIR 1998 SC a8, a 3 See, Chap. 12 ced “Pevileges of Pani a

1 (1994) 3 SCC 569, 95, Ss. 3 and 4, Parliamentary eps Tae roxecion of Pubheaion AS 977

3a. Constitution of India Arts: 105,194 ae

SC 1578 .

90. bid, 8-5, pa

95, (1970) 2 SCC 278: AIR 1979

aa FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

_ protection of witnesses petitioners and they

before the House or any committee then ei eS Mee

The right to exclude strangers from the se constitu

The right to decline permission for taki Ouse,

Jay of proceedings in Parliament. n8 of evid

‘ ve prover F yr is anact

onare ris misuse’

co

cere the live telecast of

ole concept of leg:

sence

An extension of legislative privilege is the

h Powe

sah for breach ofthe privilege or for contempt pe

Parliament has been described as the

he

Howe

peech)

ress Ltd.), the Supreme Court inter-

fh and expression under

Heo advertise of the Fight of com-

dvertisements were excluded from

‘Hamdard Dawakhana v.

Court held that

could not avail of the rights

On occasions, the use of t 7

Seer icag ae oe has brought the legisat e

In the Searchlight case,? % mie ‘a challenge to the provisions

ight case,” a notice for breach of privilege S d \Objectionable Advertisements) Act,

fe h cl femedication. The court held

against the editor of Searchli

chlight, a well known E :

ing an expunged portion of the proceedings English daily for 4

3c proceedings of the Bihar State A 1954 pou an advertise em of speech, it ceased 10 fall

4 that alin concet offre SPEED, a retook the form of a commer:

rade or commerce. The court

The editor’s petition in the S

to freedom of speech he Supreme Co aaa

pas been violated, was dismissed WaT adverisement seeking 1 promote

ee unt toa breach of privilege. Legislative p Freedom of speech

aaa consiuiona laws and in the event of Pipanised freedom loving sOcety

Ta eee ave to yield to Articles 105 and 1 a tion about that common Best Ifany limitations placed which

ear rivileges and Immunities of St oe ton gen he society being deprived “of such right then no doubt it

aerator eer fate Legislatur ves fall within the guaranteed freedom under Article 19(1)(@)-

e privilege and contempt wot all i does is that it deprives a tad, from commending his

legislature, a

, arose out of a Presid

sidential Reference under ArHeisam fll within that ter

‘ommercial 5

(Tata PF

freedom of spec!

vertise (C

any act or omission which obstructs or

Pacament inthe performance ofits funciona: Stbee Right 10 94

orimpedes any Member or officer of such Hear whichiok

aoe, or which has tendency dire yeaa

dduce such results may be treated as a contet + indirectly,

is no precedent of the offence.! ™mpt even though

goes to the heart of the natural right of an

to ‘impart and acquire informa-

wares, it would not

soning to deprive commercial advertising from protection

the Constitution. Th

ut we UP. Legislat

can gis two dees of he ive Assent Iris curious rea

se of one Keshav Singh, against a High Court for order under Article 19(1)(a). Traders and businessmen, who ‘advertise for com-

si 1om action had been tak wvereial gain, are no different from neWsPaPets, ‘and other media that are

a as commercial, profit-making enterprises, This is precisely why the

Ibject to the general

committing con

tempt of the H.

louse by ac

y addressing a disrespectful i ' a

run 26 joys special status or munity and is $i

to the Speaker, Wh

. While a

CaeTTe ees emoeseceane coe

3c judges had ‘not en residential Reference and bi

Court stressed that le mmitted contempt of the House, the Sup mia 0} 0 ag those eating azine ean

2 those advertising for commercial gain were entitled to enjoy the right

ere eurere islative privilege mus

dir te, be subject to the fund

unded a nore’o feu ff free speech under Article 19(2)l) appears flawed.

exercise of prvi

rivilege and th

he power to punish for contempt.

Prasar Bharat

el2o0s Ell, 252-2005 issued BY

¥ Eskine May Pome 4, Gazette Notifation No. x61) Cal

AIR tary P

sereaiitn SC soporte (att Ed, 198 8, See, PV, Narasimha Rao v. State {CBIISPE), (1998) 4 SCC 626: 'AIR 1998 SC 2120

rae AUR) 05 ara. 7 Supp (1) SCR fo, 989) (1) 1. ‘and a detailed discussion in Chap. “riled Privileges of Parliament 2 the State

Bess SC7 Assemblies. mae

5b, a 745 (1965) x ie

(AIR) 7 pars a a on)s SE agp: AIR 1995 SC 2438: ma

xo. See, Chap. 10 titled “Advertsn8™ -

To AIR 1966 SC 5542 1960 CHL) 735: &7

6b (AIR) 9

cae

12. Ibid, (AIR) 564, Pat 18

Pai ie

ay FAC

prs OF MEDIA LAW

Jewspapers,! a case concern)

ian Express Newspap a

In se duty on newsprint thereby affecting

ae scquntly advertising revenues

tion of Hamdard Dawakhan,

imposition of i

cof newspapers

restricted the applica

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 25

the pete

0. v. Union 0

; lorsed in Bennett Coleman &

he court recognised the position that eres

q Pe i adver-

‘ hibited drugs, et sea India," WME tor affecting circulation and any restraint on

In phe right to advertise prohibited drugs, to

cd

sition was ent

In Hamdard Dawakhana case the court was

n essential factor 7 damental right of

iy (areatment. That was the mainte gaa were a oul have the eect of infanging she fn ai

cation and self-treatment, That wa ain issue in | risements ‘cation and circulation uw .

ao det et a ae propagation, Pub eat ard Dawakhana case was decided, there has

veo beyond the needs of the case and tend to affe

m rc feel SR pc tion in the economy and advertising has come

publish all ial advertisement... we fel that thy eae huge transfor

ublish all com ; i

ein the Hamdard Dawakh b ware vominent role not only in shaping public choices but

Sere t Sea eae toca © 100 broad & Bic eet economic activity. Tt the eee

We are ofthe view that all commercial advertisement "OM as product have loded she market gneaing fetes come

be denied the protection of Article 19(1)(a) of the Conga tt! caprrsing gives one product an edge over a a es

ol a ‘which effectively sustains the media. Newspapers earn

is adverusing wiv“ vertsements than from readership subscription. In

ean

merely because they are issued by businessmen, |S

The issue of commercial speech was also dealt with by the Supr

in akal Papers." The case arose out ofa constitutional challen Ivertisng is considered to be the cornerstone of our economic

validity of the Newspaper (Price and Page) Act, 1956 which cee aeeereeiby prices for consumers are dependent on mass pro-

the government to regulate the prices of newspapers in relarigea Yatton, mass production is dependent upon volume sales, and

pages and size and to regulate allocation of space for adverse ertine sales are dependent upon advertising, Apart from the

ter The court eld that the curtailment of advertisements wo Hine of he fee on i oe ae eee

chewed Te SEC eeiah i oe ood thas ang eae et

SR newspaper industry obtains 60 per cent/8o per cent ofits revenue

from advertising. Advertising pays a large portion ofthe costs of

‘supplying the public with newspaper. For a democratic press the

sirultion, Ifthe area for advertisements is carta om of advertising subsidy is crucial. Without advertising, the resources

the newspaper will be forced up. If that herve he Price Of available for expenditure on the ‘news’ would decline, which may

wil inveaby oo des arc hat happens, the circulate lead to an erosion of quality and quansiy. The cos of the news”

conscience feuralnen oe ec remot, but di tothe pli would incteas, techy restricting its emoctare!

ement availability.2®

Asin ection ofthe Act in so fa at permits the aloes

space to advertisements also directly affects freedom g

If, on the other han Ba

ite eee ir pete space for advertisements i reduced

boctomatancanioe oes nd wlth

the Act in regul aie

In Hindustan Times v. State of U.P. the Supreme Court reiterated the

importance of advertising and its impact on the circulation of a paper.

The case arose out of a challenge to an order issued by the U.P. State

the Actin regulating the space for adver Government directing a cut of 5 per cent from bills payable to newspa-

Rete unfai’ competion. es thus pers with a circulation of about 25,000 copies for publication of gov-

real eee When emment advertisements. The government claimed that the order was t0

domotapechante aid a pension and social security scheme for full-time journalists. The

G court held that advertisements in newspapers play an important role in

generating revenue and have a direct nexus with circulation. Advertising

revenues enable newspapers to meet the cost of newsprint and other

financial liabilities. Advertising also enables the reader to purchase a

a direct interfe c

lect imterference withthe right offi

‘Pression guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a).7)

8.4985 SCC 64x a

TAME se SCs tye gee SCS

15. Indian Expre 8s Newspap a

701-02, pars,5 (Bombay) (P)

Pe ) (P) Led.

dn) 38 963 SCR ys

Union of India, (985) x8 38, (1972) 2 SCC 788: AIR 1975 SC 106,

19. (1995) 5 SCC 139: AIR 1995 SC 2458.

20. Ibid, (SCC) para. 20.

21, (2003) # SOC pr AIR 2003 SC 350

26 FACETS OF MEDIA LAW

1» affordable price.”? The owner of a

- tITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 27

newspaper at

fiable to undertake the burden of the impugned tay Gane

Ha 8 being unconstitutional The bargaining poy fy ‘

fers of release of advert er of y ‘h and expression entitle«

newspapers in marters off tisements w, v— fundamental right of spec

ae yniton on newspapers Would be violative te Theses fy a a tcc ene ie i bres

also of Section 23, Contract Act insist that his Vi Topsided or distorted one. The court hel

5, Contract Act amt ‘ ie ated yy" which survived on

Constitution as

In NOVVA ADSv. Deptt. Of Municipal Admn ang

was contended that hoardings are protected as comm Wate te

Tse igit(a) and that dissemination of informatige.t po

iL social or commercial, could not be restricted on ta wa mapa, Butte ease ee

: iS ic institution was under an

caused an obstruction to traffic, a ground not covered unde that a public ded fr publication

a citizen forws F

Section 326-A, Chennai City Municipal Corporation A

“paring eOmean “any stem or board at any ata A

private used or intended to be used for exhibiting advertiser, ‘Compelled speee

Aamandared licences for hoardings in both pea eae cae ed speech, often known as “must carry” prowsiominia Si

Aile the Stare has a rightto repulaté hea date Compelled spec euld amount to an infringement of the right to free

Tie, ee eal pul Or 4 speech amounts to a violation of the

vest in the State as a trustee for the public, hoardings in pia rreech, Whether o not compel n lation of

iso require regulation so as to ensure that they are net hata a pecch depends on the nature of the “must carty Provisiot:

Zardon

public in any manner whether by posing a dangea "provision furthers informed decision-making, which is

fe, distracting traffic or containing/obscere OP eam free fk the essence of free Speech and expeesion, it will not amount toa violation

fi tracing rae of conta ost aa the ere Ch. There ae several such instances: The statutory obligation

ofepeech which includes the right to advert) alia seer ood product must carry on its package alist of ingredients used

7 4 seas preparation; and the obligation that cigarette cartons must catty

io Pry warning that cigarette smoking is harmful ro health. Such

2 afboy discloses are meant to further the baste purpose of impart.

cogent information which enables a user to make a well informed

Te jon and do not infringe the tight to free speech.

1. non of India v. Motion Picture Assn, there was a challenge by

article by the trustee of a consumer distributors and exhibitors of motion pictures to the compulsory sereen-

Sela a pees sobs organisation, ing of educational, scientific or documentary films, or films carrying

sce ak prcte doped by a mhews or curtent events along with other films.®* The short films pro-

recent ler takes, 5 ee aa ddoced by the Films Division of the Government of India were required to

is artl calenging te conchsion ofthe trustee and publ be screened along with the usual films exhibited in cinema halls and the

ind same newpaper. The trustee published his reoinde whi exhibitors were requited to enter into agreements with the Films Division

feared inh sme newspaper: Means the author ofthe for supply of such films and pay for such supply a rental of one per cent of

tad hs Pee published in the Yogokshema the in-house maga the net collections. The court held that the test was to examine whether

the LIC When the tase tried to have his rejoinder publihed the purpose of the compulsory speech in question was to promote fee:

Same journal his request vas turned down on the ground thatthe ddom of speech orto curtail it. SN. Manohar J observed:

ies san seus publication. Adopting the “fairness docti We have to examine whether the purpose of compulsory speech

jarat High Court allowed the trustee's writ petition. The $4 inthe impugned provisions isto promote the fundamental free

rt upheld che High Court judgment and held that the LIC dom of speech and expression and dissemination of ideas, oF

an obligation to

ation to publish the rejoinder since it had published the &

22. Ibid, (SCC) 601-0.

23 Ibid SCO) orcor Gon baae

(2008) 8 SCC 43: AIR 2008 SC neq,

: 2: AIR 2008 SC 2.

sige) SEC esr aR on ek

at trumentalit

a “monoj yolistic state inst

im, could omoct in an agbitrary manner on the ‘ground that it

ds co clusive privilege to publish or refuse to publish in an

fied that there was no absolute

obligation to publish any mat-

rule

ter that

freedom of 5

Ifa “must carry”

Right of rebuttal

as freedom of speech and expression entails the right 0

he right of rebuttal, This was held by the Supreme Court ne

D. Shah.* The case arose out of the publication in a newspaper

26. Ibid, (SCC) 655, para. 12

2p. ligg9) 6 SCC x50 AIR 1999 SC 2534; also, M.C. Mehta Union of India 992)

ree Se aK tops Se 96, wherein a publi terest igation on environments

Folloicns the Supreme Court directed that al cinema halls mus sbow shor ls 10

spread environmental awareness.

28, See, $s, 12(4) and 16, Cinematograph Act, 1952:

30, 39, respectively.

Law

48 FACETS OF MEDIA

sean tis freedom. The social con

restr jgnored. When a substanti

rate or does not have

NeXt of

ally

cay 1

itis important that all availaig

eon oy il

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 29

ant pops \d include the electronic and the broadcast

wou!

mations ication. This WOU

o ieas or informatio yy audio visual communi commun .

ofcommunis aon Perertainment but also for educa jnetio® ) Ltd. v. Lokvidayan Sanghatana,

ion, i

The

wrlised not just

16 ayssey Communications (

mation, propaes

exhibit films on the

coe held that the right of a citizen to &

the Supreme Corr tn is part of che fundamental right guaran-

won of scientific ideas and the like,

an reach this large body of uneduc,

ay by which ie ent channel which is waniad state channel, Do “The court held that this right was similar to

5 sh the enertaineent channel which ig wag rader Article 19(t)(a). The court

iil + Mae abe. To earmark a smal pore ceed unde Are ro publish his views through any other media such

medium for the purpose of the right of

joardings and so on. In this.

i enertanmen sh nines, advertisements, hoar

of lor dcurenar Rms Fforshowinea Sree pe eu on Doodasanof tal

+ oked at inthis context of promoting dissent Brg recon on the ground that it encouraged superstition and

fed Hon

0 that Hind faith amongst viewers. The petition was dismissed as the petitioner

jon of

ton ty be an informed debate and decision making on pu dln ow exience of prejudice ro te public

thee ea, the impugned provisions are designed to Fura t Sen er aleecec ised era eam

ioe ech and expresion and not co curtail it, None of a he nt Cee eae

statutory provisions require the exhibitor to show a propaga Doordarstd Beyond Genocide on the ground that the film had lost its

Bil orn coefing Views which Ne bea dis cand that i criticised the action of the State Government. The

teeerne Court held that the film-maker had a fundamental right under

ser gala) to exhibit the film and the onus lay on the party refusing

Ai fytion to show that the film did nor conform to the requirements of

Rew, Te was held that Doordarshan, a State-controlled agency that

ui dependent on public funds, was not entitled to refuse telecast except

wre the grounds under Article 192). Likewise, in Anand Patwardhan,¥

the Supreme Court held that Doordarshan could not deny a film-maker

the right to telecast his award-winning documentary film based on com

mnunal violence and atrocitics on women.

; In Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India v.

g scenes, is also a form of comp Cricket Assn. of Bengal,’ the Supreme Court held that broadcasting

is a means of communication and a medium of speech and expression

within the framework of Article 19(x)(a). This case involved the rights of

a cricket association to grant telecast rights to an agency of its choice. It

was held that the right to entertain and to be entertained, in this case,

through the broadcasting media are an integeal part of the freedom

under Article 19(1)(a},

The court said

“The contention of the exhibitors, that the exaction by the governal

one per cent of their net collections for these documentaries, exh

which was costing the exhibitors vital business time, did not fing

with the court, The court found that the Films Division was j

huge expenses on the production and distribution of these films

cout India and was able to recover only part of the expenditure

impugned levy. There was nothing excessive or unreasonable a

charge.

The requirement to runa scroll displaying. a statutory warning

smoking in films that show smol

speech.

Right to broadcast

The concept “speech and expression” has evolved with the prj

of technology and encompasses all available means of expressiog

39. Union of in

SCu,

30 Ibid (SCC) 168-71, paras

The Ministry of Health and Fanaly

oer Tabacco Products (

¥. Motion Picture Assn ) 6 SCC 150, 165, para, 17:

If the right to freedom of speech and expression includes the right

to disseminate information to as wide a section of the population

“ is which enables $0: od

Wllare notified the ules OR ais possible the access which enables the ight to be so exercise

is also an integral part of the ie

(ia Mois Pobiin of dreisemene 8 Reglon gE Ee Taal

rei old th Sunol & Distribution) [2nd Amendment cules) 20H és

Invtbacs e TYME bse prods or their use to mandate 42: See, Chap. 14 tiled “Broadcasting

famine aan ani tobaeco heath ga ening and mide of the film 53, (ight) 3 SCC qto: AIR i988 SC 1642

ralth warning as a scroll at the h 3 tte Seco pall soo6 S334

ov fils nd pogmmes request Se iy asec aR ype Se

toy ea Ail grammes require a tong 36, (1995) 2 SCC 161: AIR 1995 SC 1256,

i benconjanal aa tus and such displays i 47 Ibid, (SCC) 227, para 78.

«lls, health spots or messages and)

ling the period of display

tion for display of tos

2680 pr

jo raceTs OF MEDIA L AW

to hold tha since the broadcasting meq,

The court went 08 1 ited common property Tesource,

on the use of so limited, This was a restriction in additi

the tee er Article 192) and was justified on the Broun

set oat under AV aves. Ths limitation did noteyeagh 3

ited spectro be informed, educated and entertained ig Para

whos rictonate of Film Festivals v. Gaurav Ashwin Jain,»

cout held hac the right of film-maker to make and exhibi— film

of his fundamental sight of feedom of speech and expres

Article a(t) of the Constitution and that films are a

express and communicate ideas, thoughts, messages, informe

ings and emotions, whether intended for public exhibition (eq

or non-commercial) or purely for private use. However, mata

ing to whether the government should encourage the produetigg

with aesthetic and technical excellence or social relevance, wheth

encouragement shouldbe inthe form of awards, periodcaly pa

and whether in conferring such awards, the field of competion

| be restricted only to films certified by the Censor Board are mutt

goxernment policy which cannot be the subject-matter of diel

The cour held thatthe government’ policy of restricting ene

the purposes of conferring awards to non-feature films was jutifey

the government could not be expected to evaluate or confer an a

respect ofa film which may never be seen by the public in ite

form. The argument that such a policy was unreasonable and a

was rejected by the court on the ground that the government oy

be precluded from laying down separate policies for national flay

NFAs} and for film festivals. While film festivals provide al plag

for film-makers from all over the world

explore the

to interact and exchange

Possibility of co-production, and market films, the ob

NEA is to encourage the production of films of aesthetic and te

excellence and social relevance which would contribute to the

standing and appreciation of different cultur

integration, In the circumstances,

film festivals could not automaticall

unequal and dissimilar,

applied and that could n

under Article 14

the exemptions granted in resp

ly be applied to NFAs. The two

the same standards and norms could nd

Right to silence

The very converse of spet

freedom of speech under Article 19(1

38. Ibid

39: (2007) SCC 737: AIR 2007 SC 1640.

es and promote nati

jot be a sustainable grievance of discrimina

CONSTITUTIONAL FOUNDATIONS 31

q hhool children belong:

ne eee

ing © the sect of Jeno ae the school assembly. It was contended

ational anthem Wt that ther religious beliefs precluded them from

on behalf ofthe chide Ut they were prepared to stand by respectfully

singing the aac ren sang it. Such a right was held as flowing not

pile other schoo! Os to practise religion under Article 2s(t) alone

from the fundamen ie speech and expression under Article 191).

bua to a aes rea! the Supreme Courtheld that Article r9(1)(a)

In Noise Pollution (oe igudspeakers, radios, horns, auromobiles,

did 201 Prone es, aeroplanes and the like. While everyone has the

industries, fat en repression, others have the right to listen or decline

righ 0 speech ane Gr Nobody can be compelled to listen, nor can

listen ae ee a ind ge raianl ceed ea

any one claim ei ears and minds of thes, Undectining Hieeihat

voice te Picle 21, as including the right toa pollution free and peace:

fat environment, the court held:

Kerala,” the Suprem

¢ increases his volume of speech and that too with the

ihavance of arial devices 50s (0 compulsorily expose

wling persons to heat a noise raised to unpleasant or obnox-

ious levels, then the person speaking is violating the right of oth-

ers to a peaceful, comfortable and pollution-free life guaranteed

by Article 21, Article r9()la) cannot be pressed into service for

defeating the fundamental right guaranteed by Article 21.

The court placed reliance on a passage from the judgment of the Kerala

High Court, P.A. Jacob v. Supt. of Police:®

1 right to speech implies, the right to silence. It implies free-

ia \isen and nor lle fee ea ga

prehended freedom to be free from what one desires to be free

from.... A person can decline to read a publication, or switch off

a radio or a television set. But, he cannot prevent the sound from

a loudspeaker reaching him. He could be forced to hear what

hhe wishes not to hear. That will be an invasion of his right to be

let alone, to hear what he wants to hear, or not to hear, what he

does not wish to heat. One may put his mind or hearing to his

own ose bu nt that of another, No one ea eb ES

fon the mind or ear of another and commit auricular or

seresion The use of tinea aaa Incidental tothe

‘exercise of the right. But, its use is not a matter of right, Or part

of the right.

40. (1986) 5 SCC 61s: AIR 1987 SC 748. .

41. Noise Pollution (5), re, (2005) 5 SCC 733: AIR 2005 SC 3156

42. bid, (SCC) 746, para. 11.

43. AIR 1995 Ker 1.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)