Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1997 - Hill-PrivateInterLawAspectAA1996

1997 - Hill-PrivateInterLawAspectAA1996

Uploaded by

l.gt.souzaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1997 - Hill-PrivateInterLawAspectAA1996

1997 - Hill-PrivateInterLawAspectAA1996

Uploaded by

l.gt.souzaCopyright:

Available Formats

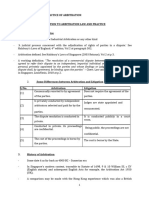

Some Private International Law Aspects of the Arbitration Act 1996

Author(s): Jonathan Hill

Source: The International and Comparative Law Quarterly , Apr., 1997, Vol. 46, No. 2

(Apr., 1997), pp. 274-308

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Institute of

International and Comparative Law

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/760718

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The International and Comparative Law Quarterly

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SOME PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW ASPECTS OF THE

ARBITRATION ACT 1996

JONATHAN HILL*

I. INTRODUCTION

A. The Background to the 1996 Act

As a method for resolving commercial disputes which ha

with two or more countries, arbitration has been given

boost this century by two developments at the internati

New York Convention of 1958-which was first implemen

and Wales by the Arbitration Act 1975-introduced a regim

a long way toward ensuring that arbitration agreements are

that arbitral awards are easily enforceable. The Conven

hugely successful in that it has been ratified by upward

including all the countries of Western Europe (with the exce

land) and nearly all countries which are significant comm

More indirect has been the influence of the Model Law on International

Commercial Arbitration, which was adopted by UNCITRAL in 1985.

Although the Model Law, which seeks to encourage States to modernise

their arbitration laws, has not been enacted by a very large number of

countries,' it has had a significant impact in that it has set an agenda for

reform-even for those countries which have decided not to enact it. The

Model Law has become "a yardstick by which to judge the quality of ...

existing arbitration legislation and to improve it".2

The Arbitration Act 1996 is the culmination of a long and arduous pro-

cess. As long ago as 1989 the Departmental Advisory Committee on Arbi-

tration (which was then under the chairmanship of Lord Mustill)

recommended that, although England should not adopt the UNCITRAL

Model Law,3 English law "should be set out in a logical order, and

expressed in language which is sufficiently clear and free from technical-

ities to be readily comprehensible to the layman" and "consideration

should be given to ensuring that any such new statute should, so far as

* Reader in Law, University of Bristol.

1. See Sanders, "Unity and Diversity in the Adoption of the Model Law" (1995) 11

Arb.Int. 1.

2. Steyn, "England's Response to the UNCITRAL Model Law of Arbitration" (1994) 10

Arb.Int. 1.

3. The Model Law has been enacted in Scotland: Law Reform (Miscellaneous Pro-

visions) (Scotland) Act 1990, s.66 and Sched.7.

274

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 275

possible, have the same structure and language as the Mod

enhance its accessibility to those who are familiar with th

Following the recommendations of the Committee, the t

ing a new Arbitration Act was commenced by a privat

tration practitioners, acting in consultation with the Depa

and Industry and the Chairman of the Departmental

mittee. The project was later adopted by the Departm

Industry and, after "a gestation period which has been ele

proportions",5 a Bill was introduced towards the end of 1

ment measure. The Arbitration Act 1996, which, inter

replaces Part I of the 1950 Act, the Acts of 1975 and 1

sumer Arbitration Agreements Act 1988, received the Roy

June 1996 and came into force on 31 January 1997.6

The 1996 Act is in four parts: the main body of the Act i

Part I (sections 1 to 84); Part II, which is entitled "Other p

ing to arbitration", sets out special rules which apply t

tration agreements, small claims arbitration in th

judge-arbitrators and statutory arbitrations (sections 8

deals with the recognition and enforcement of foreign aw

lar New York Convention awards (sections 99 to 104);

tains a few general provisions (sections 105 to 110).

The 1996 Act seeks to establish the general principles

tration law should be based and is intended to provide

statutory framework for each aspect of the arbitral proc

stressed, however, that many questions are left to be dec

and certain provisions have been drafted against the back

ing judicial decisions. It would be wrong, therefore, to see

lation as entirely self-sufficient. The structure of the

certain extent, based on the Model Law and, as far as p

Act adopts the style and, where appropriate, the text o

The 1996 Act is far removed from a codification of the p

the long title describes the new legislation as an Act

improve the law relating to arbitration".

The purpose of the discussion which follows is to foc

which the 1996 Act has affected private international law

requires consideration of three general areas. First, to

the 1996 Act affect the jurisdiction of the English cou

4. A Report on the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Com

(1989), p.34, para.108(7). For a discussion of the Committee's report

Report of the Mustill Committee: A Foreign View" (1990) 106 L.Q.R

5. Steyn, op. cit. supra n.2.

6. The date appointed by the Secretary of State under s.109 by SI 1

7. For reasons considered in infra Part I.B ss.85-87 (which deal with

agreements) have not been brought into force.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

276 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

does the 1996 Act deal with choice of law questions? Third, what impact

does the 1996 Act have on the recognition and enforcement of arbitral

awards? Before turning to consider these issues (in infra Parts II to IV)

something ought to be said about domestic and international arbitration.

B. Domestic and International Arbitration

An arbitration may be "domestic"-where all the relevant factors are

connected with one country only-or it may be "international" in the

sense that it involves a foreign element or a number of foreign elements.8

It is, of course, perfectly possible for the same legal regime to be applied in

both domestic and international cases. However, some legal systems

choose to distinguish the two categories, normally with a view to giving the

courts greater control over domestic arbitrations. In an international case

the parties to the dispute and the cause of action may have only a very

tenuous connection with the country in which the arbitration is conduc-

ted.9 By contrast, in a domestic case the arbitral tribunal is, in effect, a

substitute for the local courts and this may be thought to justify closer

judicial supervision of the arbitral process.

Under English law prior to the enactment of the 1996 Act domestic and

international cases were distinguished in three contexts. First, whereas the

courts had discretion whether or not to stay proceedings brought in

breach of the terms of a domestic arbitration agreement,"' in an inter-

national case, if the relevant conditions were satisfied, the grant of a stay

was mandatory." Second, the right to appeal to the courts on points of law

under the 1979 Act was more easily excluded in international cases than in

domestic cases.'2 Third, the Consumer Arbitration Agreements Act 1988

8. To describe an arbitration which involves a foreign element as "international" is

potentially misleading. It has been pointed out that, except in the case of an arbitration

between two States or other international legal persons conducted in accordance with public

international law, all arbitrations are national, in the sense they are subjected to national

legal systems: Mann, "Lex Facit Arbitrum", in Sanders (Ed.), International Arbitration:

Liber Amicorum for Martin Domke (1967), p.157, at p.159. Notwithstanding such obser-

vations, the epithet "international" is convenient and is routinely employed to distinguish

domestic cases from cases with a foreign element.

9. Some legal systems limit the court's general powers in cases where the parties to an

arbitration have little or no connection with the seat of arbitration. For example, following

the reforms of 1985, Art.1717.4 of the Belgian Judicial Code provides as follows: "The Bel-

gian court can take cognisance of an application to set aside only if at least one of the parties

to the dispute decided in the arbitral award is either a physical person having Belgian

nationality or residing in Belgium; or a legal person formed in Belgium or having a branch or

some seat of operation there."

10. Arbitration Act 1950, s.4.

11. Arbitration Act 1975, s.1.

12. S.3(6).

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 277

rendered certain consumer arbitration agreements

domestic cases"3 but not in international cases.14

The desirability of drawing a distinction between domestic and inter-

national cases is controversial. The Departmental Advisory Committee in

its Report on the Arbitration Bill, published in February 1996, suggested

that consideration should be given to the abolition of the distinction on the

ground that the rules which apply in international cases "fit much more

happily with the concept of party autonomy than our domestic rules,

which were framed at a time when attitudes to arbitration were very dif-

ferent and the courts were anxious to avoid what they described as usurp-

ation of their process".' The Departmental Advisory Committee also

drew attention to the fact that a distinction between domestic and other

arbitrations may produce odd results: "an arbitration agreement between

two English people is a domestic arbitration agreement, while an agree-

ment between an English person and someone of a different nationality is

not, even if that person has spent all his time in England".'6

Notwithstanding these arguments, the 1996 Act, as originally drafted,

sought to perpetuate the distinction between domestic and international

cases in relation to the staying of actions and to the right to appeal to the

court on points of law."7 However, before the Act came into force it

became clear that the distinction was, in practical terms, impossible to

maintain.

The problem was that the differential treatment of domestic and inter-

national agreements was seen to be inconsistent with EC law in that it

discriminated against nationals of other EC member States. This problem

had been noted by the Departmental Advisory Committee before the text

of the Bill was finalised'8 and was raised when the Bill was being debated in

the House of Lords."9 More significantly, after the enactment of the new

legislation-but before its commencement-the issue was considered by

the courts in the context of the Consumer Arbitration Agreements Act

1988.

In Phillip Alexander Securities and Futures Ltd v. Bamberger2() the plain-

tiff was an English company carrying on business as a futures and option

broker; the defendants, six of the plaintiff's former customers, were Ger-

13. S.1.

14. S.2(a).

15. P.66 (para.320).

16. Idem, p.67 (para.326).

17. Ss.85-87. The 1996 Act extends the application of the Unfair Terms in Consumer

Contracts Regulations 1994 to consumer arbitration agreements: ss.89-91. These provisions

apply equally to domestic and international agreements.

18. Report, supra, n.15 at p.67 (para.326).

19. See Lord Hacking's comments during the committee stage: H.L. Hansard, Vol.569,

CWH cols.23-24 (28 Feb. 1996).

20. The Times, 22 July 1996.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

278 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

man nationals resident in Germany. Each of the contracts between the

parties contained an arbitration clause. When disputes arose the defend-

ants chose not to refer them to arbitration, but started litigation in Ger-

many instead. As regards the five defendants who had already obtained a

judgment in Germany, the plaintiff sought a declaration that the German

judgments were not enforceable in England. As regards the sixth, the

plaintiff sought an injunction to restrain the defendant from pursuing the

German proceedings.

It was clear that had the defendants been UK nationals and resident in

England the arbitration agreements would have been rendered

unenforceable by section 1 of the 1988 Act. However, the plaintiff con-

tended that, because the arbitration agreements were not domestic, the

effect of section 2 was that they were valid and enforceable.

The defendants argued that section 2 of the 1988 Act was incompatible

with EC law as constituting a restriction on the freedom to provide ser-

vices contrary to Article 59 of the EC Treaty and/or unlawful discrimi-

nation contrary to Article 6 thereof.2' The Court of Appeal, after

considering the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice,22 accepted the

defendants' argument. Leggatt LJ expressed the court's conclusion in the

following terms:23

A rule which disadvantages recipients of services in another Member State

inevitably restricts the freedom of the service provider to provide services

on equal terms to everyone in the Community and is inimical to the objec-

tive of the Treaty ... of achieving an internal market characterised by the

abolition of obstacles to the free movement of services. As the Court has

made clear, whether the restriction is placed on the provider of the services

or the recipient, the effect is the same, and it is inconsistent with the purpose

of the Treaty. Nationals in Germany, Spain or Finland may be less inclined

to avail themselves of the services of [the plaintiff] because English law does

not afford them the same treatment as that which is available to English

nationals, and in our judgment this is clearly discriminatory and impermiss-

ible pursuant to articles 6 and 59 of the Treaty.

The arguments relating to the discriminatory effect of the 1988 Act

could also be applied to the provisions of the 1996 Act relating to domestic

arbitration agreements. A dual regime-which distinguishes domestic

arbitration agreements from international ones-fails to comply with EC

law because it treats nationals of other EC member States less favourably

than UK nationals. The implications of the decision in Phillip Alexander

Securities for the 1996 Act, as originally drafted, were potentially far-

21. Formerly Art.7 EEC.

22. Cases 262/82 and 26/83 Luisi and Carbone v. Ministero del Tesoro [1984] E.C.R. 377;

Case 186/87 Cowan v. Tresor Public [1989] E.C.R. 195; Case C-45/93 Commission v. Spain

[1994] E.C.R. 1-911; Case C-384/93 Alpine Investments BV [1995] E.C.R. 1-1141.

23. Lexis transcript.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 279

reaching: in order to avoid unlawful discrimination

other EC member States, the domestic rules would

arbitration agreements involving nationals of other E

well as in cases involving UK nationals.

Obviously, the idea that the domestic rules should b

UK nationals and nationals of other EC member S

unattractive from the policy point of view. It was

intended that, in a case involving an English arbitr

cluded between an English seller and an Italian bu

excluding the right to appeal to the court on points o

tive only if entered into after the commencem

proceedings.24

As regards the staying of proceedings brought i

tration agreement, the implications of Phillip Alex

even more serious. The application of the domestic ru

cases involving nationals of other EC member Sta

breach of the international obligations which t

assumed on ratifying the New York Convention. This

considering the situation where, in breach of an Engl

a German national starts legal proceedings in Eng

national. The reasoning of the Court of Appeal wo

clusion that, in order to comply with EC law, the cas

the same way as a domestic case involving two UK

say, the court should have a discretion whether or no

However, under the New York Convention the grant

tory in this type of situation.26

Therefore, to comply with the requirements of bot

laws discrimination on grounds of nationality) an

(which requires the imposition of a stay in internatio

practical solution was to remove the special provision

trations and to apply the international regime to all a

ing the decision in Phillip Alexander Securitie

Advisory Committee issued a consultation documen

vassing opinion on, inter alia, the repeal of the dome

for by section 88 of the 1996 Act).27 In the light o

consultation exercise it was recommended that the domestic rules should

not be brought into force. The Secretary of State accepted this recommen-

dation.28 Accordingly, the rules set out in Part I of the 1996 Act apply

24. S.87(1).

25. S.86(2).

26. Art.II.

27. A Consultation Document on Commencement of the Arbitration Act 1996 (1996)

28. See SI 1996/3146.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

280 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

regardless of whether the arbitration agreement is domestic or

international.

II. JURISDICTION QUESTIONS AND THE STAYING OF ACTIONS

IT is important in the present context to distinguish two different

which are often treated as involving questions of jurisdiction. T

question is whether the court has the power to hear and determ

substance of a dispute, notwithstanding the fact that the part

agreed to arbitration. This is a question which until recently was ad

by the provisions of the 1950 and 1975 Acts and which is now dealt w

the 1996 Act. The second question in cases involving arbitration con

the extent of the court's powers of supervision and support in rela

arbitrations which are conducted in England and abroad. This

question is considered in Part III.

A. The Staying of Actions: Introduction

If a court accepts jurisdiction over the substance of a dispute wh

parties have agreed to refer to arbitration the arbitral process is se

undermined. Where legal proceedings are commenced in breach

terms of an arbitration agreement the defendant may reasonably e

to be able to rely on the agreement and ask the court to decline jur

tion. English law traditionally drew a distinction between domestic

(which fell within the scope of the 1950 Act) and international case

ing within the scope of the 1975 Act). It has been seen that, althou

1996 Act, as originally drafted, sought to maintain this distinction

already been abandoned.29

The staying of actions brought in breach of the terms of an arbi

agreement is regulated by section 9 of the 1996 Act.3" This section

regulates both international and domestic cases, applies even if the

29. See supra Part I.B.

30. S.9 reads as follows:

"(1) A party to an arbitration agreement against whom legal proceedings are brought

(whether by way of claim or counterclaim) in respect of a matter which under the agreement

is to be referred to arbitration may (upon notice to the other parties to the proceedings)

apply to the court in which the proceedings have been brought to stay the proceedings so far

as they concern that matter.

(2) An application may be made notwithstanding that the matter is to be referred to arbi-

tration only after the exhaustion of other dispute resolution procedures.

(3) An application may not be made by a person before taking the appropriate procedural

step (if any) to acknowledge the legal proceedings against him or after he has taken any step

in those proceedings to answer the substantive claim.

(4) On an application under this section the court shall grant a stay unless satisfied that the

arbitration agreement is null and void, inoperative, or incapable of being performed.

(5) If the court refuses to stay the legal proceedings, any provision that an award is a con-

dition precedent to the bringing of legal proceedings in respect of any matter is of no effect in

relation to those proceedings."

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 281

outside England and Wales or if no seat has been de

mined.3" The 1996 Act effectively mirrors the pre-exis

obligation to grant a stay of proceedings under section

was not dependent on there being any connection be

the agreement, the situation or the parties.32

Although much of section 9 replicates section 1 of the

a more accessible form, there are various difference

noted.

B. A Confirmation

One of the issues which arose in Channel Tunnel Group Ltd v. Balfour

Beatty Construction Ltd33 was whether the court was required to grant a

stay under section 1 of the 1975 Act in a case where the parties were not in

a position to proceed immediately to arbitration. In the Channel Tunnel

case the plaintiffs started proceedings in England in the context of which

they sought an injunction to restrain the defendants from suspending

work on the tunnel's cooling system. The plaintiffs countered the defend-

ants' application for a stay on the ground that the contractual dispute-

resolution clause provided for a two-stage process-reference to a panel

of experts followed, if necessary, by arbitration-and that, when the pro-

ceedings were commenced, the first stage of that process had not yet been

commenced, let alone completed. Lord Mustill was troubled by the fact

that Article 11(3) of the New York Convention, on which section 1 was

based, provides that, assuming that the relevant conditions are satisfied,

the parties shall be "referred to arbitration". The perceived problem was

that, because the first stage of the process had not yet taken place, the

dispute could not be "referred to arbitration". Lord Mustill thought that if

the English legislation had followed the Convention "it would have been

hard to resist the conclusion that the duty to stay does not apply to a situ-

ation where the reference to the arbitrators is to take place, if at all, only

after the matter has been referred to someone else".34 This was one of the

reasons why Lord Mustill preferred to base the grant of a stay on the

court's inherent jurisdiction rather than on section 1.

The supposed problem which Lord Mustill identified in the Channel

Tunnel case is expressly addressed by section 9(2) of the 1996 Act, which

provides that an application for a stay "may be made notwithstanding that

the matter is to be referred to arbitration only after the exhaustion of

other dispute resolution procedures". This subsection can do no harm. It

is doubtful, however, whether it was strictly necessary. It has been con-

31. S.2(2)(a).

32. Channel Tunnel Group Ltd v. Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd [1992] Q.B. 656 (CA).

33. [1993] A.C. 334.

34. Idem, p.354.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

282 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

vincingly argued that the difficulty which worried Lord Mustill is illusory

since "the wording of article 11(3) of the New York Convention ... does

not mean that the court has to transfer the case to the arbitrator. It simply

means that, once the action is stayed by the court, the parties have no

other remedy than going to arbitration, should they wish to pursue their

dispute."35

C. A Significant Change

The significant reform which has been introduced by the 1996 Act is that a

stay can no longer be refused on the basis that the court is satisfied that

"there is not in fact any dispute between the parties".36 The 1975 Act's

requirement that there should be a dispute between the parties has no

counterpart in the New York Convention, having been derived from ear-

lier English legislation.37 The question as to whether there was a dispute

between the parties arose most frequently in the situation where the plain-

tiff, in an attempt to wriggle out of an arbitration agreement, applied for

summary judgment under RSC Order 14 and resisted the defendant's

application for a stay on the basis that, since the defendant had no defence

to the claim, there was not in fact a dispute between the parties for the

purposes of section 1 of the 1975 Act.

The traditional analysis was that, if the plaintiff could show that there

was no defence to the claim, there was no dispute between the parties and

a stay would be refused; if, however, the circumstances were such that the

defendant was entitled to be given leave to defend, the court was bound to

refer the matter to arbitration under section 1.38 There were a number of

problems with this approach. First, the tendency was for the court to be

drawn into a consideration of matters which the parties had agreed to

refer to arbitration. Second, the traditional approach depended on the

word "dispute" in section 1 being interpreted differently from the same

word when used in a standard arbitration clause (in which the parties

agree, for example, "Any dispute arising out of or in connection with this

contract shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration... "). If the

word "dispute" were given the same interpretation in both contexts the

result would be an absurdity: the arbitrator would be deprived of jurisdic-

tion in a situation where the respondent had no seriously arguable defence

35. Reymond (1993) 109 L.Q.R. 337,339 (referring to Van den Berg, The New York Con-

vention of 1958 (1981), p.129).

36. Arbitration Act 1975, s.1(1).

37. The relevant words were inserted into the Arbitration Clauses (Protocol) Act 1924 by

s.8 of the Arbitration (Foreign Awards) Act 1930. The phrase was repeated in s.4(2) of the

Arbitration Act 1950 when the legislation was consolidated and, although s.4(2) of the 1950

Act was repealed by the 1975 Act, the same phrase was included in the text of s.1.

38. See Kerr LJ in SL Sethia Liners Ltd v. State Trading Corporation of India Ltd [1985] 1

W.L.R. 1398, 1401.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 283

to the claimant's claim. These problems were exposed by

ter v. Nelson39 and, following this decision, the trad

repeatedly questioned, although the authorities were

There was no doubt, however, as to which way the wind

The amendment effected by the 1996 Act was long ov

the addition in section 1 of the 1975 Act of a further con

of a stay over and above those required by the New Yor

hardly consistent with the international obligations wh

when the United Kingdom ratified the Convention.42 W

to refer their disputes to arbitration it is essentially fo

rather than the court-to decide whether or not th

defence to a claim. Although RSC Order 14 has been use

claimants to avoid the delays which are inherent in the

which may be exploited by a recalcitrant responden

makes an order for summary judgment, even thoug

within the scope of an arbitration agreement between t

arily subverts the principle of party autonomy by takin

the hands of the agreed tribunal. As Lord Mustill ha

different context):44

The parties choose arbitration for better or for worse. The

features, of which there are many. When things take a t

there are limits beyond which they cannot be allowed,

their arbitration agreement, to run to the courts for hel

There is, of course, nothing in the 1996 Act to pre

arbitration agreement from making an application for

under RSC Order 14. However, if the proceedings are br

of a matter which under the agreement is to be referre

(that is to say, if there is a dispute which falls within th

diction) the defendant is entitled to a stay and the fact

does not have a plausible defence is not a relevant co

D. Formal Requirements

Section 5(1) of the 1996 Act states that the provisions o

where the arbitration agreement is "in writing". Thr

39. [1990] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 265.

40. The John C. Helmsing [1990] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 290.

41. See, in particular, the speech of Lord Mustill in Channel Tunn

42. Reymond, op. cit. supra n.35, at p.340.

43. For a discussion of the ways in which a respondent may slow d

Harris, "Abuse of the Arbitration Process-Delaying Tactics an

J.Int.Arb. (2) 87.

44. SA Coppie Lavalin NV v. Ken-Ren Chemicals & Fertilizers Lt

652.

45. S.9(1).

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

noted about the way in which the legislation deals with the requirement of

"writing". First, the definition has been extended in order to take account

of modern technological advances. Whereas the 1975 Act referred to an

exchange of letters or telegrams,46 section 5(6) makes it clear that refer-

ences in the 1996 Act to "anything being written or in writing include its

being recorded by any means". This provision is obviously intended to

cover agreements which are recorded by telex, fax or electronic mail.

Read literally section 5(6) could be regarded as including a tape-recorded

oral agreement. During the Second Reading in the House of Lords, Lord

Noel-Buxton posed the following question: "Would a tape recording ...

recorded by one party with the acquiescence of, but without the formal

authority of the other or others, during which it was orally agreed to

include an arbitration clause in common form, be a sufficient agreement in

writing?"47 Since the new legislation is, to a significant extent, based on

Article 7(2) of the Model Law, which refers to "other means of telecom-

munication which provide a record of the agreement", it is preferable to

interpret section 5(6) as covering agreements which are recorded as text,

but not those which are recorded as speech.48

Second, subsection (5) follows Article 7(2) of the Model Law by

providing:

An exchange of written submissions in arbitral or legal proceedings in which

the existence of an agreement otherwise than in writing is alleged by one

party against the other and not denied by the other party in his response

constitutes as between the parties an agreement in writing to the effect

alleged.

Third, the 1996 Act endorses the decision of the Court of Appeal in

Zambia Steel & Building Supplies Ltd v. James Clark & Eaton Ltd.49 The

defendant, an English company, provided the plaintiff, a Zambian com-

pany, with a written price quotation for goods "made on our terms of busi-

ness". The defendant's standard terms-which were set out on the back of

the price quotation-included a clause which provided for arbitration in

England. The plaintiff ordered goods from the defendant and orally

assented to the defendant's terms. The plaintiff claimed that the goods

were damaged on delivery and started proceedings in England; the

defendant applied for a stay on the basis of the 1975 Act. The Court of

Appeal decided that an oral acceptance of a written proposal to arbitrate

qualified as an agreement in writing for the purposes of the 1975 Act. If the

same facts were to arise under the 1996 Act the same result would be

46. S.7(1).

47. H.L. Hansard, Vol.568, col.780 (18 Feb. 1996).

48. This view is supported by the DAC's Report on the Arbitration Bill (1996), p.14

(para.33).

49. [1986] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 225.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 285

reached. An agreement is in writing "if the agreemen

(whether or not it is signed by the parties)".5 Furthe

"Where parties agree otherwise than in writing b

which are in writing, they make an agreement in writ

also satisfies the 1996 Act's formal requirements if th

by exchange of communications in writing, or if

denced in writing.52

Whether the decision in Zambia Steel is consistent with the New York

Convention has been the subject of disagreement. One view is that the

purpose of Article II(2) of the Convention-which expressly refers only

to arbitration agreements which are concluded by an exchange of letters

or telegrams or which are signed by both parties-was to deny effect to an

arbitration agreement which is proposed in writing and accepted orally or

tacitly.53 According to this view, Article II(2) lays down both a minimum

and a maximum requirement with the consequence that "a court may not

require more, but also may not accept less" than is provided by the Con-

vention.54 The strict view of Article II(2) suggests that the courts should

not give effect to an arbitration clause which is contained in standard

terms and conditions communicated by one party to the other but not

signed by both. The broader view is that the New York Convention simply

stipulates certain forms of arbitration agreement which must be enforced

by the courts of the contracting States; it does not seek to prevent the

courts of a contracting State from giving effect to an arbitration agree-

ment which does not fall within one of the classes of agreement expressly

referred to in Article II(2). According to the Departmental Advisory

Committee the broader approach adopted by English law "is consonant"

with Article II(2) of the English text of the New York Convention: "The

non-exhaustive definition in the English text ('shall include') may differ in

this respect from the French and Spanish texts, but the English text is

equally authentic ... and also accords with the Russian authentic text."55

As regards the relationship between the 1996 Act and the Model Law, it is

clear that section 5 of the 1996 Act adopts a more indulgent attitude to

formal questions than the equivalent provisions of the Model Law.56

Because English law takes a more flexible approach to formalities than

the laws of some other countries, circumstances will arise in which,

50. S.5(2)(a).

51. S.5(3).

52. S.5(2)(b), (c) and (4).

53. Van den Berg, op. cit. supra n.35, at p.196.

54. Idem, p.179. See also Mann (1987) 3 Arb.lInt. 171.

55. Report on the Arbitration Bill (1996), p.14 (para.34).

56. Art.7(2) of the Model Law extends neither to an oral agreement evidenced in writing

nor to a written clause orally or tacitly accepted by the parties.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

286 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

although the English court will stay proceedings (on the basis of section 9

of the 1996 Act), the courts of other countries-which take a stricter view

of Article 11(2) of the New York Convention and/or follow the Model

Law-will not. This presents certain dangers and potential problems.

Consider, for example, the following situation. X (an English company)

and Y (an Italian company) orally conclude a contract for the sale of goods

on X's standard terms and conditions (which include a clause selecting

English law as the applicable law and a clause providing that any dispute

arising out of the contract should be referred to arbitration in England). X

subsequently sends a printed document setting out the terms to Y, who

does not reply. A dispute arises, each party alleging that the other is in

breach of contract.

If Y starts proceedings in England, the court will grant a stay on the

basis that the conditions set out in the 1996 Act are satisfied; according to

English law the arbitration clause forms part of the contract between the

parties and the clause is "in writing" for the purposes of section 5 of the

1996 Act. If, however, Y starts proceedings in Italy, the Italian courts will

almost certainly refuse to grant a stay; X will not be able to rely on the

arbitration clause because-according to the strict view-it does not satis-

fy the formal requirements of Article 11(2) of the New York Convention.

If the Italian court assumes jurisdiction over the substance of the dispute57

and gives judgment on the merits in Y's favour, X is placed in an unenvi-

able position. If X seeks to proceed with arbitration in England-in

accordance with the clause set out in X's terms and conditions-Y may

raise the Italian judgment as a defence to X's claim. The question then

arises as to whether the Italian judgment is entitled to recognition in

England. This question in turn depends on whether the Italian judgment

concerns "arbitration" for the purposes of Article 1(4) of the Brussels

Convention. If the Italian judgment declaring the arbitration clause to be

ineffective and deciding in Y's favour on the merits is regarded as falling

within the scope of the Brussels Convention58 it is entitled to automatic

recognition in England 59 and it is irrelevant that the judgment was given in

defiance of an arbitration agreement which is valid and binding according

to its proper law. If, however, the judgment concerns "arbitration" it falls

outside the Brussels Convention's scope and X is entitled to rely on sec-

tion 32 of the Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments Act 1982 to resist recog-

nition of the Italian judgment in England. Although the European Court

of Justice considered the meaning of "arbitration" in the Marc Rich case,60

57. If the place of performance of X's obligation was Italy, the Italian court would, subject

to the arbitration clause, be entitled to assume jurisdiction under Art.5(1) of the Brussels

Convention.

58. This was the approach adopted in The Heidberg [1994] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 287.

59. Art.26.

60. Case C-190/89 Marc Rich & Co. AG v. Societa Italiana Impianti, The Atlantic Emperor

[1991] E.C.R. 1-3855.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 287

commentators are divided on the implications of this

ognition ofjudgments which are given in disregard of

ment.6' The position is unlikely to be clarified definiti

has been considered by the Court of Justice.62 The p

that legal harmony within Western Europe is not hel

with regard to the implementation of Article II of th

tion, not all Brussels and Lugano contracting Sta

approach.

III. CHOICE OF LAW

IN the field of choice of law, international commercial arbit

described as a "forensic minefield"." The legislation wh

repealed by the 1996 Act had very little to say about choice

tions, leaving such matters to be determined by the common

law that different aspects of an arbitration may be subjecte

laws. In particular, the law governing an arbitration clause (

of the agreement) must be distinguished not only from the

the arbitration procedure (the curial law or lex arbitri) but a

law applicable to the merits of the dispute between the p

sae). Where, for example, the parties agree to refer a disput

in Scotland, the parties cannot rely on English legislation to

English court on a point of law-even if English law is t

because whether a party can appeal on a point of law is a pro

tion to be determined by the curial law.65

A. The Curial Law and Its Scope

Most of the provisions in Part I regulate either the internal

the arbitration or the court's powers of supervision and sup

not be appropriate in the present context to list them all. M

made, however, of the following groups of statutory provis

with central elements of the arbitral process: sections 15 to

tribunal); sections 33 to 45 (the arbitral proceedings and the

court in relation to the arbitral proceedings) and sections 66

of the court in relation to the award).

How should the sphere of operation of these provisions be

The legislation which the 1996 Act has replaced was silent as

61. Compare e.g. Briggs (1991) 11 Y.B.E.L. 527, 529 and Cheshire and

International Law (12th edn, 1992), p.436.

62. For further discussion see Hill, The Law Relating to International

putes (1994) pp.63-66 (para.3.3.3.4.5) and 553-554 (para.20.6.1).

63. As defined by Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments Act 1982, s.1(3).

64. Redfern and Hunter, Law and Practice of International Commercial

edn, 1991), p.72.

65. James Miller & Partners Ltd v. Whitworth Street Estates (Mancheste

583.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

of application. Under the old law, when, in a case involving foreign

elements, the court was faced with the question whether particular rules

were applicable, the scope of each statutory provision was considered sep-

arately. The view was taken that "just because two rules of law are enacted

in the same statute, it does not follow that the same connecting factor

applies in each case"." For example, some sections of the 1950 Act were

thought to be applicable in cases where the arbitration agreement was

governed by English law67 and others where England was the seat of arbi-

tration.68 Fortunately, the uncertainties of the old law have been swept

away by a comprehensive set of rules in the 1996 Act which identify the

circumstances in which the various provisions of Part I are applicable.

Broadly speaking, there are two possible bases on which the law of a

particular country might be thought appropriate to govern the procedural

aspects of an arbitration: first, the parties might expressly choose the law

of country X as the curial law (the "autonomy criterion"); second, the

arbitration might have a close connection with country X by virtue of its

seat being located there (the "territorial connection").

At common law the parties were-in theory, at any rate-allowed to

select both the seat of arbitration and the curial law.69 It was even held that

the parties could effectively choose to split the curial law and to subject

different aspects of the procedure to different laws; the parties might, for

example, agree that internal procedural matters (such as the conduct of

the arbitration itself) were to be governed by the law of one country and

that external procedural questions (such as the powers of the court to

supervise the award) should be governed by the law of another.71 If the

parties chose country X as the seat of arbitration, but failed expressly to

choose the curial law, the law of country X governed; if the parties chose

the law of country X as the curial law, but failed to specify the seat, the seat

of arbitration was in country X.7' Through the application of these prin-

ciples, the curial law would normally be the law of the seat of arbitration.

What was the position, however, if the parties chose country X as the seat

of arbitration but the law of country Y as the curial law?72 The courts were

never required to answer this question and to decide whether primacy

66. Staughton U in Irish Shipping Ltd v. Commercial Union Insurance Co. Ltd [1991] 2

Q.B. 206, 220.

67. S.27 as interpreted in International Tank & Pipe SAK v. Kuwait Aviation Fuelling Co.

KSC [1975] Q.B. 224.

68. S.12 as interpreted in Channel Tunnel, supra n.33.

69. Naviera Amazonica Peruana SA v. Compania Internacional de Seguros del Peru

[1988] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 116.

70. Union of India v. McDonnell Douglas Inc. [1993] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 48.

71. Naviera Amazonica, supra n.69.

72. Why anyone should choose to do this is not clear; it would be much simpler to choose

country Y as the seat but to conduct the hearings in country X: Redfern and Hunter, op. cit.

supra n.64, at pp.93-94.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 289

should be given to the chosen law or the law of the s

only discussions in the cases are obiter.73

Rather than seeking to construct a series of rules f

party autonomy, the 1996 Act follows Article 1(2)

adopting as its starting point a "territorial criterion"

vides: "The provisions of this Part apply where the sea

in England and Wales... " The adoption of a territor

mean, of course, that the parties have no control ove

the parties are free to designate the seat of arbitra

seen, the parties may by agreement exclude those pro

Act which are not mandatory. But the adoption of a

does mean that if parties agree to arbitration in Engl

Part I are prima facie applicable by virtue of the simp

arbitration is in England.

The version originally favoured by the Departme

mittee left the scope of the various provisions of Part

reference to the rules of the conflict of laws. This w

considerable uncertainty since the draft legislation at

specify what were the relevant conflict of laws rules

various statutory provisions for the purposes of such

sion of section 2(1) has the advantage of simplicity

therefore, preferable to the previous version-

changed only at the eleventh hour.76

Of course, the general principle in section 2(1) p

point of departure, not the whole story. It would be v

the law to adopt a simplistic view that all the provisi

necessarily apply if the seat of arbitration is in Engla

them should apply if the seat is elsewhere. There a

consider. As arbitration is a consensual process the pa

eral, be able to decide for themselves how their dispu

There is nothing in principle objectionable in allo

exclude the law of the seat-whether by an ad hoc

adoption of institutional arbitration rules or by ch

other country. Nevertheless, the principle of party a

ordinate to the public interest of the country in

73. See, in particular, Kerr U in Naviera Amazonica, supra n.6

74. See Holzmann and Neuhaus, A Guide to the UNCITRA L M

Commercial Arbitration: Legislative History and Commentary (1

75. S.3(a).

76. Even after the Second Reading in the House of Lords the

Committee had not yet come round to the general principle that all

England should be subject to the provisions of Part I: Report on t

pp.11-12 (paras.23-25) and 74 (para.357).

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

arbitration is located. Since the law of the seat has a legitimate interest in

ensuring that the arbitral process meets certain basic standards of justice

and fairness, the parties to an arbitration cannot be entitled to exclude

procedural rules which are mandatory according to the law of the seat.

Finally, as the courts of one country may make a positive contribution to

proceedings being conducted in other countries, it is legitimate for the

court to exercise certain types of power to support foreign arbitral

proceedings.

The general principle set out in section 2(1) is modified by a number of

other rules. First, subsections (2) to (5) provide that some sections con-

tained in Part I apply even if the seat of arbitration is outside England and

Wales. Second, the provisions of Part I are divided into two groups:

mandatory and non-mandatory provisions. As regards the mandatory

provisions, if the seat of arbitration is in England they cannot be excluded

by the parties' agreement.77 The non-mandatory provisions, however,

may be departed from by the parties. Most of the non-mandatory pro-

visions take one of two forms: either they state that "the parties are free to

agree" a particular issue (and that, failing such agreement, the statutory

rules apply) or they provide that a particular rule shall apply "unless

otherwise agreed by the parties".78

To illustrate how these rules operate four different situations will be

considered:

(1) the seat of arbitration is in England and the parties have not

chosen the law of another country as the curial law;

(2) the seat of arbitration is in England but the parties have chosen

the law of another country as the curial law;

(3) the seat of arbitration is not in England and the parties have not

chosen English law as the curial law;

(4) the seat of arbitration is not in England but the parties have cho-

sen English law as the curial law.

There is no doubt that situations (1) and (3) are much more common than

situations (2) and (4).

1. Seat in England; English curial law

In the standard case where the parties agree to arbitration in England

and the parties either choose English law as the curial law or make no

choice, the position under the 1996 Act is straightforward enough; section

77. S.4(1) and Sched.1. The following mandatory provisions are listed in Sched.1: ss.9-13,

24, 26(1), 28-29, 31-33, 37(2), 40, 43, 56, 60, 66-68 and 70-75.

78. The following provisions in Part I either apply "unless the parties otherwise agree" (or

"unless otherwise agreed by the parties" or "subject to the right of the parties to agree") or

state that "the parties are free to agree" a particular matter: ss.7-8, 14-18, 20-23, 25, 26(2),

27, 30, 34-36, 37(1), 38-39, 41-42, 44-45, 47-55, 57-58, 61-65, 69, 76-79.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 291

2(1) provides that the provisions of Part I are appl

case whether or not the situation involves a foreign e

sense, largely irrelevant in terms of the conduct of t

powers of the court.

However, it is relevant to note that many of the pow

court by the 1996 Act are discretionary. There is no p

Act which specifically seeks to direct how the court's

exercised. The only guidance given by the 1996 Ac

general principles set out in section 1, which stipu

that the provisions of Part I must be construed in

principle that "the parties should be free to agree how

resolved, subject only to such safeguards as are ne

interest".

In a case where parties, none of whom is connected with England,

choose England as the seat of arbitration, guidance as to how the court

should exercise its discretion may be found in the observations of Lord

Mustill in SA Coppee Lavalin NV v. Ken-Ren Chemicals & Fertilizers

Ltd.79 This case concerned an application for an order for security for costs

under section 12(1)(a) of the 1950 Act8" in the context of an ICC arbi-

tration between foreign companies. Lord Mustill placed particular

emphasis on two points.8" First, regard should be paid to the degree of

connection that the parties or the arbitration have with England and its

legal system. The court should generally be less willing to intervene in

cases where the parties have little connection with England. Second, the

court should "recognise and give effect to any agreement between the

parties, express or tacit, as to the way in which the arbitration should be

conducted".82 This second point is an important one. Under the 1996 Act

the non-mandatory provisions may be excluded by the parties' agree-

ment. So, for example, the parties, having decided to refer their dispute to

arbitration in England, can agree that the court's power to grant interim

injunctions (under section 44 of the 1996 Act) should be excluded. For the

purposes of Part I of the 1996 Act "agreement" means an agreement in

writing (or evidenced in writing) in accordance with the formal require-

ments laid down in section 5. Therefore, only an express, written agree-

ment can exclude the powers conferred by the 1996 Act. However, the

79. [1994] 2 W.L.R. 631. This case has been extensively discussed: Andrews [1994] C.L.J.

470; Beechey [1994] A.D.R.L.J. 242; Branson (1994) 10 Arb.Int. 313; Davenport (1994) 10

Arb.Int. 303; Hill [1995] L.M.C.L.Q. 19; Reymond (1994) 110 L.Q.R. 501.

80. Under the 1996 Act the court no longer has the power to make orders for security for

costs (s.44); the tribunal may, however, order a claimant to provide security for the costs of

the arbitration (s.38(3)).

81. Although Lord Mustill was in the minority in deciding that the court should not make

an order for security for costs, there was unanimous support for the approach which was

advocated.

82. Lord Mustill at [1994] 2 W.L.R. 631, 641.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

implication of Lord Mustill's speech in the Coppee Lavalin case is that,

even where the parties have not excluded the court's powers by written

agreement, the court should, as a matter of discretion, only exercise its

powers if to do so would not be inconsistent with the type of dispute-resol-

ution process to which the parties impliedly committed themselves.

2. Seat in England; choice of foreign curial law

The second situation which needs to be considered is where England is

the seat of arbitration but the parties have chosen the law of another coun-

try as the curial law. Some of the problems posed by this type of case were

considered under the common law in Union of India v. McDonnell Dou-

glas Inc."3 The contract between the parties included an arbitration clause

which provided: "The seat of the arbitration proceedings shall be London

... The arbitration shall be conducted in accordance with the procedure

provided in the Indian Arbitration Act 1940." Saville J interpreted the

parties' agreement as an implied choice of English law as regards external

procedural questions (notably the rules governing interim measures, the

rules empowering the exercise by the court of supportive measures and

the rules providing for the exercise by the court of its supervisory jurisdic-

tion) and a choice of Indian law only as regards the internal conduct of the

arbitration (and only to the extent that such law was not inconsistent with

the implied choice of English law as the curial law). As a result of this

interpretation Saville J avoided the more thorny difficulties which would

have been posed if the parties' agreement had been interpreted as provid-

ing for external procedural questions to be governed by the law of a for-

eign country.

Under the 1996 Act, where England is the seat of arbitration but the

parties have chosen a foreign curial law there are three aspects to be con-

sidered. First, section 2(1) provides that, as a general rule, the provisions

of Part I apply. Second, as already noted, the 1996 Act provides that vari-

ous mandatory provisions have effect notwithstanding any agreement to

the contrary.X4 A choice of a foreign curial law cannot have the effect of

excluding the mandatory provisions. Not surprisingly, the mandatory pro-

visions referred to in Schedule 1 include those aspects of Part I which con-

cern the court's supervisory jurisdiction. However, to the extent that the

court's powers of supervision are discretionary the parties' choice of a

foreign curial law is a factor which should be considered; the court may

choose not to exercise its powers, notwithstanding the fact that the seat of

arbitration is in England.85

83. [1993] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 46.

84. S.4(1) and Sched.1.

85. Saville J in Union of India, supra n.70, at p.51.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 293

Third, the parties are given a free hand with regard

tory provisions, in particular those which relate to t

the arbitration. The 1996 Act states that, as regards a

within the scope of the non-mandatory provisions, t

law is equivalent to an agreement making provision a

Where, for example, parties agree to arbitration in E

with German procedural law, all the non-mandato

1996 Act are displaced by the relevant provisions o

3. Seat abroad; foreign curial law

Where the seat of arbitration is in another country

not choose English law as the curial law, the provision

prima facie irrelevant; section 2(1) states that the pro

if the seat of arbitration is in England. Does this m

court can play no role in relation to a foreign arbitra

In Channel Tunnel Group Ltd v. Balfour Beatty Con

House of Lords held that the powers conferred by

1950 Act were exercisable only in relation to an Engli

Mustill thought that there was "no reason why Pa

had the least concern to regulate the conduct of an ar

abroad pursuant to a foreign arbitral law"." It was he

court had the power under section 37(1) of the Supre

grant the injunction sought by the plaintiffs, but tha

discretion, it should not do so.

The 1996 Act approaches the court's powers to in

arbitration differently. First, section 2(2) provides

apply even if the seat of arbitration is outside Eng

been designated or determined. Under this provision

to the staying of actions are of universal application;

the provisions relating to the court's power to order t

award in the same manner as a judgment."

Second, section 2(3) provides that the powers con

(securing the attendance of witnesses) and section 44

cisable in support of arbitral proceedings) apply even

tration is outside England or no seat has been desig

The power conferred by section 43 applies where the

are being conducted in England. The court could, f

order under section 43 in a situation where the partie

86. S.4(5).

87. [1993] A.C. 334.

88. Idem, p.359.

89. Ss.9-11.

90. S.66. Nothing in s.66 affects the recognition or enforcement of an award under oth

statutory provisions, in particular under Part III of the Act: s.66(4).

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

as the seat, but it has been decided to hold the hearings in England. The

power is limited, however, to cases where the witness is in the United

Kingdom. Section 44 allows the court to exercise, with regard to an arbi-

tration, various powers which it enjoys in the context of litigation. The

matters in relation to which the powers can be exercised include the taking

of evidence of witnesses, the preservation of evidence and property, the

sale of goods and the grant of interim injunctions or the appointment of a

receiver."9

The idea which underlies section 2(3) is the distinction between powers

of supervision and powers of support. The process of arbitration is subject

to certain limitations, in particular the fact that the arbitrator is not

invested with many of the coercive powers which are enjoyed by the

courts. While it would be wholly inappropriate to confer on the English

court the power to supervise a foreign arbitration being conducted in

accordance with a foreign law, there is nothing, in principle, improper

about the courts of one country assisting an arbitration being conducted in

another. The practical value of assistance rendered by the courts of one

country to the resolution of a dispute in another country has already been

recognised in the context of international litigation; Article 24 of the Brus-

sels and Lugano Conventions92 enables the courts of one contracting State

to grant provisional measures in support of legal proceedings which are

being conducted in another contracting State.93 It was desirable that the

1996 Act should enable the English court to exercise similar powers in

support of foreign arbitral proceedings.

Of course, the possibility that the English court may make procedural

orders in relation to a foreign arbitration involves certain risks. There is a

danger that the English court and the courts of the country in which the

seat is located might come into conflict by issuing inconsistent orders in

relation to the same matters. It is, therefore, important that the English

court should exercise caution when invited to come to the assistance of a

foreign arbitration. Indeed, the 1996 Act encourages such caution by pro-

viding that the court may refuse to exercise any power if the fact that the

seat of arbitration is outside England and Wales makes it inappropriate to

exercise that power.94 The court should also be guided by Lord Mustill's

observation in the Channel Tunnel case that where the seat of arbitration

is located in a foreign country the court of that country is "the natural

91. S.44(2).

92. These provisions are implemented in England by Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments

Act 1982, s.25.

93. Where the substantive proceedings are being conducted in a non-contracting State the

powers of the court are more limited: Mercedes-Benz AG v. Leiduck [1996] 1 A.C. 284. The

current state of the law is a cause of increasing exasperation among commentators. See, in

particular, Collins (1996) 112 L.Q.R. 8.

94. S.2(3).

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 295

court for the source of interim relief".95 If, in a cas

tration being conducted abroad, an application for int

in England it is for the plaintiff to show why the Eng

the relevant foreign forum, should grant relief. If, f

lar form of relief is not available under the law of th

which the English court has to weigh in the balanc

however, that the absence of a remedy in the fore

itself, justify the intervention of the English court.

In addition, section 2(4) states that the court may ex

ferred by any provision in Part I not mentioned in s

the purpose of supporting the arbitral process where

has been designated or determined and the conne

makes it appropriate to do so.

Finally, it should be noted that section 1(c) prov

governed by Part I "the court should not intervene e

[Part I]". It follows that the courts should not follow

by the House of Lords in the Channel Tunnel case-wh

although relief could not be given under the Arbitrat

did have the power to grant an injunction under th

ferred by section 37(1) of the Supreme Court Act 198

the 1996 Act should be all-embracing; if the cour

chooses not to exercise-the powers conferred by

should be the end of the matter.

4. Seat abroad; choice of English curial law

The last situation is where the parties choose English law as the curial

law but the seat is in another country. At common law the proper

approach to this type of case was not free from doubt. Although there are

dicta in some of the cases that the courts had no powers of supervision over

foreign arbitrations,96 in James Miller & Partners Ltd v. Whitworth Street

Estates (Manchester) Ltd97 the House of Lords seemed to proceed on the

assumption that, in a case where Scotland was the seat of arbitration, the

parties might have expressly agreed to the supervisory jurisdiction of the

English court.

Once again, the position under the 1996 Act could not be clearer. The

role of the English court in relation to foreign arbitrations is determined

by section 2, which does not allow for the application of the provisions of

Part I on the basis of an express choice of English law as the curial law.

Although, as has been seen, subsections (2) to (4) provide that some sec-

tions are applicable in cases where the seat is abroad or where the seat has

95. [1993] A.C. 334, 368.

96. Naviera Amazonica, supra n.69; Channel Tunnel, supra n.32.

97. [1970] A.C. 583.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

not been designated or determined, according to the general rule in sec-

tion 2(1) the powers conferred by Part I cannot be exercised unless the

seat of arbitration is in England. With regard to a foreign arbitration there

can, for example, be no question of the English court being able to exer-

cise its power to replace an arbitrator (under section 24) or to set aside an

award for serious irregularity (under section 68). Even if the parties have

expressly chosen English law as the curial law, these are matters which are

to be dealt with by the appropriate foreign courts.

By adopting, as its starting point, a territorial criterion rather than an

autonomy criterion, on the face of it the 1996 Act renders an express

choice of English law as the curial law irrelevant. It should be recalled,

however, that the powers which may be exercised under sections 43 and 44

are discretionary and that section 2(3) requires the court to consider the

appropriateness or inappropriateness of exercising its powers in cases

where England is not the seat of arbitration. One of the factors which the

court is entitled to take into account is the express wishes of the parties. It

is not unreasonable to suppose that the court may be more willing to exer-

cise the powers conferred by section 44 if the parties have chosen English

law as the curial law.

B. The Law Governing the Arbitration Agreement

The determination of the law governing an arbitration agreement is a mat-

ter which continues to be governed by the common law.98 The cases estab-

lish that the proper law of an arbitration agreement is the law chosen by

the parties or, in the absence of choice, the law of the country with which

the agreement is most closely connected (which will normally be the law of

the seat)." It has already been noted that, as a general rule, whether the

provisions of Part I of the 1996 Act are applicable turns on the seat of

arbitration; whether English law is the proper law of the arbitration agree-

ment is not relevant.

However, section 2(5) provides that certain provisions apply where the

law applicable to the arbitration agreement is the law of England and

Wales even if the seat of arbitration is elsewhere. The provisions referred

to by section 2(5) are sections 7 and 8. Section 7 endorses the decision of

the Court of Appeal in Harbour Assurance Co. (UK) Ltd v. Kansa Gen-

eral International Insurance Co. Ltd"" by providing for the separability of

the arbitration agreement; section 8 provides that the arbitration agree-

ment is not discharged by the death of either of the parties.

98. See Dicey and Morris, The Conflict of Laws (12th edn, 1993), pp.576-579; Hill, op. cit.

supra n.62, at pp.473-475 (para.17.1); Thomas, "Proper Law of Arbitration Agreements"

[1984] L.M.C.L.Q. 304.

99. Hamlyn & Co. v. Talisker Distillery [1894] A.C. 202; Deutsche Schachtbau, infra n.121.

100. [1993] Q.B. 701.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 297

It should be noted that none of the provisions of th

with time limits"" apply on the basis that English law

the arbitration agreement. These provisions norma

seat of arbitration is in England. So, for example,

vides that the court may extend a contractual time lim

ment of arbitration-would not apply in a case

arbitration is in France even if English law is the pro

tration agreement. However, section 2(4) provides tha

tration has not been determined, the court may exer

conferred by Part I if satisfied that, by reason o

England, it is appropriate to do so. Accordingly,

national Tank & Pipe SAK v. Kuwait Aviation Fue

which, prior to the designation of the seat of arbitrat

an extension of time under section 27 of the 1950 Ac

section 12 of the 1996 Act, on the basis that the part

mit their disputes to ICC arbitration was governed

be decided in the same way under the 1996 Act.

As regards the limitation of actions, section 13 p

tation Acts apply to arbitral proceedings as they a

ings." Quite complex conflict of laws questions can

have connections with more than one country. Su

out of a contract which contains an English arbitratio

which stipulates that Ruritanian law is the law applic

of the contract. Are limitation questions governed by

itanian law? The identification of the applicable limit

the following steps: first, section 2(1) provides tha

arbitration is in England, section 13 applies-in

mandatory rule;"" second, section 13 requires the a

evant English legislation;'" third, according to the

Periods Act 1984 limitation questions are governed

to the merits of the dispute;"15 fourth, section 2(1) p

the seat of arbitration is in England, the law governi

dispute is to be determined by section 46 of the 1996

46(1) provides that, if the parties have chosen the app

tral tribunal shall decide the dispute according to

therefore, that the Ruritanian limitation period appl

101. Ss.12, 13, 50, 79 and 80.

102. [1975] Q.B. 224.

103. S.4(1) and Sched.1.

104. The relevant legislation includes the Foreign Limitation P

105. S.1. For further discussion see Dicey and Morris, op. cit.

Hill, op. cit. supra n.62, at pp.449-453 (para.5.1).

106. See infra Part III.C.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 International and Comparative Law Quarterly [VOL. 46

Finally, a word should be said about the jurisdiction of the arbitrator. It

is established at common law that the proper law of the arbitration agree-

ment governs questions relating to the arbitrator's jurisdiction.~"" Section

30(1), which provides that "the arbitral tribunal may rule on its own sub-

stantive jurisdiction", is, however, an aspect of the curial law. The tribu-

nal's power to rule on its own jurisdiction is a procedural question, even

though the extent of its jurisdiction is a substantive matter. It is clear that

section 30(1) applies in a case where England is the seat of arbitration,

even if the law of another country is the proper law of the arbitration

agreement.

C. The Law Governing the Merits of the Dispute

As regards the determination of the law to govern the merits of the dispute

between the parties, the position under the common law prior to the

enactment of the 1996 Act was somewhat uncertain. It was generally

accepted that the curial law determined which choice of law rules should

guide the arbitral tribunal: if English law was the curial law, the relevant

English choice of law rules were applicable; if French law was the curial

law, the relevant French choice of law rules were applicable.'"1 What was

less clear, however, was the precise content of the choice of law principles

to be applied in English arbitrations. Whereas statutory provisions laying

down specific choice of law rules to be applied by arbitral tribunals are an

established feature of the laws of other countries,"' there was no such

provision in English law prior to the 1996 Act. The reform effected by

section 46-which sets out the principles which are to guide the arbitral

tribunal in determining the law applicable to the merits of the dispute-

brings English law into line, not only with the laws of those countries

which have implemented the Model Law but also with the laws of many

other countries in Europe and in other parts of the world.

At common law the orthodox position was that, if England was the seat

of arbitration, the tribunal was bound by the same choice of law rules as

the English court.'"' This position came under attack, however, from cases

in which the courts seemed to accept that, if authorised by the parties to do

107. Nova (Jersey) Knit Ltd v. Kammgarn Spinnerei [1977] 1 W.L.R. 713.

108. Norske Atlas Insurance Co. Ltd v. London General Insurance Co. Ltd (1927) 28 LI.L.

Rep. 104; Union Nationale des Cooperatives Agricoles de Cdreales v. Robert Catterall & Co.

Ltd [1959] 2 Q.B. 44. See also Mann, op. cit. supra n.8, at p.167; Thomas, "Commercial Arbi-

tration-Justice According to Law" (1983) 2 C.J.Q. 166; Jaffey, "Arbitration of Commercial

Contracts: the Law to be Applied by the Arbitrators", in Perrott and Pogany (Eds), Current

Problems in International Trade Law (1987), pp.129-151.

109. See e.g. Art.1496 of the French New Code of Civil Procedure and Art.1054(2) of the

Dutch Code of Civil Procedure.

110. Czarnikow v. Roth, Schmidt & Co. [1922] 2 K.B. 478 is normally cited as authority for

the orthodox position.

This content downloaded from

189.62.45.195 on Tue, 12 Sep 2023 15:40:11 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

APRIL 1997] Arbitration Act 1996 299