Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effect of Age and Education On The Trail Making Test and Determination of Normative Data For Japanese Elderly People

Effect of Age and Education On The Trail Making Test and Determination of Normative Data For Japanese Elderly People

Uploaded by

Stefanie KarinaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effect of Age and Education On The Trail Making Test and Determination of Normative Data For Japanese Elderly People

Effect of Age and Education On The Trail Making Test and Determination of Normative Data For Japanese Elderly People

Uploaded by

Stefanie KarinaCopyright:

Available Formats

Blackwell Publishing AsiaMelbourne, AustraliaPCNPsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences1323-13162006 Folia Publishing Society2006604422428Original ArticleEffect of age and education on TMTR.

Hashimoto et al.

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences (2006), 60, 422–428 doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01526.x

Regular Article

Effect of age and education on the Trail Making Test and

determination of normative data for Japanese elderly

people: The Tajiri Project

RYUSAKU HASHIMOTO, phd,1,2 KENICHI MEGURO, md, phd,2,3 EUNJOO LEE, msc,1,2

MARI KASAI, phd,1 HIROSHI ISHII, md, phd1,4 AND SATOSHI YAMAGUCHI, md, phd2

Departments of 1Behavioral Neurology and Cognitive Neuroscience, and 3Geriatric Behavioral Neurology,

Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, 2Tajiri SKIP Center, Tajiri and 4Kawasaki-Kokoro

Hospital, Kawasaki, Japan

Abstract The Trail Making Test (TMT) is a common two-part neuropsychological test, in which visuospatial

ability (TMT-A) and executive function (TMT-B) are evaluated. Normative data for this test have

not been reported for Japanese subjects; therefore, the purpose of the present paper was to inves-

tigate the effect of age and education on the TMT in 155 healthy elderly adults with clinical demen-

tia rating 0 (healthy). The participants were classified into three groups based on age (70–74 years,

75–84 years and ≥85 years), and also into three groups based on educational level (6 years, 8 years

and ≥10 years). The time to complete TMT-A and TMT-B were measured, and the difference in

score between TMT-A and TMT-B (B–A) and the ratio of the score (B/A) were calculated as indi-

ces of executive function. The time for completion of both parts of the TMT increased markedly in

the ≥85-years group. For TMT-A, there was a significant difference between the 6-years and 8-years

groups, and between the 6-years and ≥10-years groups, and for TMT-B, there was a significant dif-

ference between the 6-years and ≥10-years groups, and between the 8-years and ≥10-years groups.

The difference and ratio scores increased in the ≥85-years group, but the educational level did not

significantly influence these scores. Our data suggest that cognitive functions evaluated by TMT-A

and TMT-B are not affected by aging until the subjects are ≥85 years old. For TMT-A, an educa-

tional effect becomes apparent when the population includes poorly educated subjects, but this

part of the test is not affected by educational level provided that the subjects have some education

(>6 years). The time to complete TMT-B is affected by educational level, consistent with previous

reports. However, when adjusted using the results for TMT-A [(B-A) or (B/A)], the educational

effect on executive function disappeared. Thus, the effect of educational level on executive func-

tion was unclear in normal elderly subjects.

Key words aging effect, educational effect, normal aging, Trail Making Test.

INTRODUCTION general mental disorder,1,2 although recent studies

have suggested that subjects with MCI have mild

The concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is of

impairment in executive function3,4 and visuospatial

importance in normal aging and dementia.1 Subjects

ability.5,6 Because mixing of MCI subjects with healthy

with MCI have some memory disorder, but no marked

elderly people may result in underestimation of the

ability of the healthy elderly, distinguishing healthy

elderly people from subjects with MCI is particularly

Correspondence address: Kenichi Meguro, MD, PhD, Department

important in determining normative data for cognitive

of Geriatric Behavioral Neurology, Tohoku University Graduate

School of Medicine, 2-1, Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8575,

tests.7

Japan. Email: k-meg@umin.ac.jp The Trail Making Test (TMT) is a frequently used

Received 7 June 2005; revised 17 January 2006; accepted 22 screening test for brain damage or dementia. The TMT

January 2006. consists of parts A and B (TMT-A and TMT-B). The

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

Effect of age and education on TMT 423

first, TMT-A, requires an individual to connect ran- Based on data from this project, we published the

domly located numbers in numerical order as rapidly results of a survey on the prevalence of dementia in

as possible, whereas TMT-B contains both numbers 1998.22 Five years later, we provided an analysis of 284

and letters, and the subject is required to connect the subjects who were rated as healthy or as having ques-

numbers and letters alternately (e.g. 1-A-2-B-3-C). The tionable dementia using the Clinical Dementia Rating

score on each part of the TMT is the amount of time (CDR) scale (CDR 0 and CDR 0.5, respectively).23,24

required to complete the task. The TMT-A score In the current study, neuropsychological tests were

reflects visual search ability and motor skills, whereas conducted on these 284 subjects and their CDR was re-

the TMT-B score additionally reflects the ability for assessed. A clinical team of medical doctors and public

cognitive alternation.8–10 Thus, the time for completion health nurses, independent of those performing the

of TMT-B is usually used as an index of executive neuropsychological assessment, determined the CDR

function. in the following manner: (i) before the participants

The influences of age and educational level on the were interviewed by doctors, public health nurses vis-

time to complete the TMT have been widely reported. ited the participants’ homes to evaluate their daily

Most studies have examined how age affects the time activities; (ii) observations by family members regard-

to complete TMT-A and TMT-B;11–18 these studies have ing the participants’ lives were obtained using a semi-

concluded that the time for TMT completion increases structured questionnaire; (iii) the participants were

with age. In contrast, conclusions regarding the influ- examined by doctors to assess episodic memory, orien-

ence of educational level on the TMT have been incon- tation and judgment; and (iv) with reference to the

sistent between studies; some studies have shown that information provided by family members, the doctors

educational level affects both parts of the TMT,11–14,16,19 and public health nurses held a joint meeting to deter-

with the time for completion of TMT-A and TMT-B mine the CDR for each participant.

being shorter for persons of higher educational level, Among the 284 participants, 160 subjects were rated

but four studies have found that education affects only as CDR 0 (healthy) and were included in the assess-

TMT-B.15,17,18,20 However, these latter studies included ment of the effects of age and educational level on the

participants with relatively high educational levels TMT test. The 160 subjects met the following criteria:

only, suggesting that the effects in a population with (i) they were assessed as normal from neurological and

a relatively low educational level were not fully psychiatric perspectives; (ii) they showed no signs of

investigated. active central nervous system or psychiatric conditions

Because motor speed is affected by the aging pro- that might adversely affect cognitive function; (iii) they

cess,21 there may be effects of age on TMT-A and B. were not taking psychoactive medication; and (iv) they

However, simply regarding the TMT-B score as the had no past history of disorders which might have

index of executive function may overestimate or affected cognition, such as head injury, alcohol or drug

underestimate the effects of aging and educational abuse, or stroke. Demographic data for the subjects are

level. Thus, to adjust for the influence of motor speed shown in Table 1. Ultimately, four of the 160 subjects

and visual search, we used the difference between were unable to perform the TMT due to physical prob-

TMT-A and TMT-B (B–A) and the ratio (B/A) as indi- lems, and therefore 156 subjects were included in the

ces of executive function in the present study. Using data analysis. Written informed consent was obtained

this procedure, we were able to use TMT-B to evaluate from all the participants and from their family mem-

executive function more accurately. Hence, the pur- bers, and the study was approved by the Ethics Com-

pose of the study was to examine the influence of age mittee of Tajiri.

and educational effect on the time for TMT completion

and to assess executive function in healthy elderly

Table 1. Study population

people, thereby obtaining normative TMT data for

Japanese subjects. Age group (years)

70–74 75–84 ≥85

METHODS

n 90 53 17

Participants % female 53 57 65

Age (years) 72.1 ± 1.4 77.7 ± 2.6 87.7 ± 2.2

Since 1988, we have been conducting a community- Years of education 8.9 ± 1.8 8.1 ± 1.7† 8.8 ± 1.9

based project on stroke, dementia, and bed-

confinement prevention in Tajiri, a typical agricultural †

Mean years of education of the 75–84-years group is

area in northern Japan (the so-called Tajiri Project). different from that of the 70–74-years group (P = 0.016).

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

424 R. Hashimoto et al.

Tasks Analysis 2: educational effect

Trail Making Test-A and TMT-B were administered by The 156 subjects were classified into three groups

clinical psychologists and a trained occupational ther- according to educational level: 6 years (n = 15), 8 years

apist who were blinded to the CDR score. The tests (n = 101), and ≥10 years (n = 40). Based on the old

were conducted according to the standard adminis- Japanese educational system, 6 years corresponds to

tration procedure described by Spreen and Strauss.25 elementary school, 8 years corresponds to junior high

During the tests, the examiner corrected each error school, and ≥10 years corresponds to high school or

immediately. The time to complete each part of the college. ancova in spss 11.5 J was performed to identify

TMT was recorded, and raw time scores were used as the educational effect on the TMT, with the age of

the dependent variables. In the Japanese version of the subjects used as a covariate.

TMT-B, the test is revised by changing letters from

the Roman alphabet (A B C . . .) into Kana letters

RESULTS

Kana is the Japanese phonogram. The

test–retest reliability for TMT-A and TMT-B was 0.737 One subject exceeded the time limit for completing

and 0.595, respectively,18 and the time limits for per- TMT-A, and a second subject exceeded the time limit

forming TMT-A and TMT-B were set at 180 s and 480 s, for TMT-B. Eleven subjects (approx. 7% of all sub-

respectively. jects) could not perform the TMT-B because they

could not follow the rules for the test. Three of these

subjects were in the 6-years education group (20% of

Analysis 1: aging effect

the 6-years group) and eight were in the 8-years edu-

The 156 healthy elderly subjects were classified into cation group (8% of the 8-years group).

three groups according to age: 70–74 years (n = 88), 75–

84 years (n = 51), and ≥85 years (n = 17), respectively.

Analysis 1: aging effect

Using spss 11.5 J for Windows (spss Japan Inc., Tokyo,

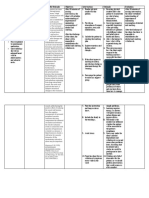

Japan), analysis of covariance (ancova) was performed The results of analysis 1 are given in Fig. 1. Both parts

to examine the effect of aging on the TMT, with the of the TMT were affected by normal aging (TMT-A,

educational level of the subjects used as a covariate. P = 0.002; TMT-B, P < 0.001). The time to complete

(a) (b) (c) (d)

110 375 300 5.5

* * * *

* * 5.0

100 * 325 250 *

4.5

275

Time (s)

90

Time (s)

Time (s)

200 4.0

80 225 150 3.5

3.0

70 175 100

2.5

60 125 50 2.0

70–74 75–84 85+ 70–74 75–84 85+ 70–74 75–84 85+ 70–74 75–84 85+

Age groups (years)

Figure 1. Means and standard errors for (a) Trail Making Test (TMT)-A, (b) TMT-B, (c) difference of the two scores and (d)

ratio of the two scores, *P < 0.05. (a) For TMT-A, ancova showed a significant effect of age (F = 6.687, P = 0.002), and the cova-

riate of years of education was significant (F = 10.757, P < 0.001). Post-hoc tests showed that the ≥85-years group was significantly

different from the 70–74-years (P < 0.001) and 75–84-years groups (P = 0.017). (b) For TMT-B, ancova also showed a significant

effect of age (F = 9.095, P < 0.001), and the covariate of years of education was significant (F = 7.155, P = 0.008). Post-hoc tests

showed that the ≥85-years group was significantly different from the 70–74-years (P < 0.001) and 75–84-years groups (P = 0.006).

(c) For the difference of the two scores, ancova showed a significant effect of age (F = 7.507, P < 0.001), and the covariate of years

of education was significant (F = 5.196, P < 0.024). Post-hoc tests showed that the ≥85-years group was significantly different from

the 70–74-years (P < 0.001) and 75–84-years groups (P = 0.003). (d) For the ratio of the two scores, ancova showed a significant

effect of age (F = 4.12, P = 0.018), but the covariate of years of education was not significant. Post-hoc tests showed that the ≥85-

years group was significantly different from the 70–74-years (P = 0.006) and 75–84-years groups (P = 0.01).

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

Effect of age and education on TMT 425

both parts of the test was especially long in the ≥85- for both TMT-A and TMT-B. Almost all healthy sub-

years group. The difference and ratio scores were also jects were able to perform TMT-A, while approxi-

affected by normal aging (difference score: P < 0.001, mately 7% could not complete TMT-B.

ratio score: P < 0.018) and were higher in the ≥85-years In TMT-A, a person is required to connect randomly

group. arranged numbers as fast as possible, and the main cog-

nitive functions required for this part of the test are

rapid visual searching and motor speed. In TMT-B, the

Analysis 2: educational effect

subject is required to connect numbers and letters in an

The results of analysis 2 are shown in Fig. 2. Both parts alternate manner, which requires simultaneous reten-

of the TMT were affected by educational level (TMT- tion of two sequences and flexible exchange between

A, P = 0.006; TMT-B, P = 0.027), and the time to com- these sequences. Therefore, the TMT-B score is

plete TMT-A was particularly long in the 6-years thought to reflect executive function, while the TMT-A

group. There was no difference in the completion time score reflects visuospatial function.

between the 8-years and ≥10-years groups. For TMT-B, Previous studies have indicated that the time for

there was no difference in completion time between completion of the TMT is affected by aging, and that

the 6-years and 8-years groups, but the time to com- the time for TMT-B completion is affected by educa-

plete TMT-B was shorter in the ≥10-years group. tional level.11–20 There is inconsistency in previous

Although the effect of educational level on the differ- reports regarding the effect of educational level on

ence score was not significant, P approached statistical TMT-A times.

significance (P = 0.056). The educational effect on the

ratio score was not significant (P = 0.309).

Aging effect on the TMT

Only limited normative TMT data are available for

DISUCUSSION

older elderly people.15,17 The sample size in our ≥85-

A summary of the mean values and standard devia- years group was relatively small (n = 17), but subjects

tions is given for each age and educational-level sub- with MCI were carefully excluded using the CDR

group for both parts of the TMT in Table 2. These are scale, and therefore we believe that our data are rep-

normative TMT data for Japanese healthy elderly sub- resentative of the functional ability of normal older

jects (CDR 0) in a population properly distinguished elderly people. We found that the times for completion

from subjects with questionable dementia (CDR 0.5). of the two parts of the TMT were affected by normal

Significant aging and educational effects were found aging, consistent with previous reports.11–18 The time for

(a) (b) (c) (d)

100 300 300 5.5

5.0

90 260 250

4.5

Time (s)

Time (s)

80 220

Time (s)

200 4.0

70 180 150 3.5

* 3.0

60 140 *

100

* * 2.5

50 100 50 2.0

6 8 10+ 6 8 10+ 6 8 10+ 6 8 10+

Educational levels

Figure 2. Means and standard errors for (a) Trail Making Test (TMT)-A, (b) TMT-B, (c) difference of the two scores and (d)

ratio of the two scores, *P < 0.05. (a) For TMT-A, ancova showed a significant effect of educational level (F = 5.259, P = 0.006),

and the covariate of age was significant (F = 18.187, P < 0.001). Post-hoc tests showed significant differences between the 6-years

and 8-years groups (P = 0.019) and between the 6-years and ≥10-years groups (P = 0.002). (b) For TMT-B, ancova also showed

a significant effect of education (F = 3.852, P = 0.024), and the covariate of age was significant (F = 18.699, P < 0.001). Post-hoc

tests showed a significant difference between the 6-years and ≥10-years groups (P = 0.017) and between the 8-years and ≥10-

years groups (P = 0.027). (c) For the difference of the two scores, ancova did not show a significant effect of education (F = 2.939,

P = 0.056), but the covariate of age was significant (F = 13.167, P < 0.001). (d) For the ratio of the two scores, ancova also did not

show a significant effect of education (F = 1.185, P = 0.308), but again the covariate of age was significant (F = 4.068, P = 0.046).

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

426 R. Hashimoto et al.

Table 2. Normative data for the TMT in Japanese subjects

TMT-A time (s) TMT-B time (s)

Age group Years of

(years) education Mean ± SD n Mean ± SD n

70–74 6 83.1 ± 39.3 7 259.8 ± 97.0 5

8 63.4 ± 23.1 53 190.6 ± 86.0 49

≥10 57.3 ± 16.2 28 154.4 ± 71.7 27

Total 63.0 ± 23.5 88 182.8 ± 85.2 81

75–84 6 84.9 ± 29.8 7 234.7 ± 81.2 6

8 73.9 ± 26.0 35 229.1 ± 94.9 35

≥10 61.0 ± 22.0 8 182.0 ± 43.8 8

Total 73.3 ± 26.3 50 222.1 ± 87.6 49

≥85 6 121.0 ± 0. 1 295.0 ± 0. 1

8 89.7 ± 41.5 12 289.7 ± 96.8 9

≥10 75.0 ± 33.8 4 276.3 ± 112.8 4

Total 88.1 ± 38.8 17 286.2 ± 93.5 14

Total 6 86.5 ± 33.7 15 250.2 ± 82.3 12

8 70.2 ± 27.9 100 214.7 ± 94.6 93

≥10 59.8 ± 19.6 40 172.6 ± 79.1 39

Total 69.1 ± 27.5 155 206.2 ± 92.0 144

TMT, Trail Making Test.

An 80-year-old woman who had an 8-years education level could not finish within the time limit for TMT-A, and a 71-year-

old man who had a ≥10-years education level could not finish within the time limit for TMT-B.

completion of the TMT was markedly increased in the data is that the threshold for influence on the TMT dif-

≥85-years group (Fig. 1), suggesting that motor skills, fers between educational levels. For TMT-A, the time

visual searching and executive function do not decline for completion may not be influenced by educational

very significantly in normal aging until the age of level, provided that the subjects have at least some

85 years. Confirmation of this conclusion will require education (>6 years). Therefore, for surveys targeted at

accumulation of more data, including data for younger relatively highly educated participants, the influence of

adults. educational level on TMT-A may not be detectable sta-

tistically. In contrast, a statistically significant differ-

ence in the time for completion of TMT-B was found

Educational effect on the TMT

between educational levels 8 years and ≥10 years. This

The mean time to complete TMT-A and TMT-B result is consistent with previous reports, especially

decreased with higher educational level, consistent those including highly educated subjects, and our data

with several previous reports.11–14,16,19 However, there is confirm that highly educated persons (>8 years) are

controversy concerning the effect of educational level likely to complete TMT-B in a shorter time than those

on the TMT, especially for TMT-A, because other with less education.

reports have concluded that TMT-A is not influenced

by education, while still finding an influence on TMT-

Executive function

B.15,17,18,20 It should be noted that the subjects in these

reports were highly educated; almost all had educa- The results of analysis 1 showed that the aging effect is

tional levels of ≥10 years. In contrast, the present pop- significant after adjusting for the influence of motor

ulation included subjects with education only up to the speed and visual search. Thus, the aging process clearly

elementary school level (6-years group). affects executive function. Stuss et al. found a relation-

The educational effects on TMT-A and TMT-B were ship between TMT-B impairment and frontal lobe

statistically significant for persons of low educational damage, by comparing patients with damage to the

level in the present subjects, but interestingly we did frontal and non-frontal regions with control subjects.26

not find a significant difference between the 8-years Recently, Tisserand et al. reported a longitudinal study

and ≥10-years groups for TMT-A. Moreover, the mean using voxel-based morphometry, which showed that

time to complete TMT-A was long, especially in the 6- the largest age-related decreases in gray matter in

years group. Thus, one possible interpretation of these healthy elderly people were found in the frontal lobe.27

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

Effect of age and education on TMT 427

Thus atrophy or dysfunction in the frontal lobe may be cognitive functioning in aging. J. Gerontol. B Psychol.

reflected by the TMT-B score, and hence may be an Sci. Soc. Sci. 1996; 51: 217–225.

index of executive function. In addition, our results 8. Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indi-

showed that the influence of aging is particularly cator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Skills 1958;

8: 271–276.

important in the ≥85 years age group.

9. Crowe SF. The differential contribution of mental track-

In the present study we were unable to show a clear

ing, cognitive flexibility, visual search, and motor speed

educational effect on executive function, using both to performance on parts A and B of the Trail Making

the difference and the of the TMT-A and -B scores. Test. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998; 54: 585–591.

One of the possible explanations for this result is that 10. Loewenstein DA, Ownby R, Schram L et al. An evalua-

educational level did not affect executive function, as tion of the NINCDS-ADRDA neuropsychological

measured by TMT-B, when the effects of motor speed criteria for the assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a

and visual searching ability were properly controlled. confirmatory factor analysis of single versus multi-

Thus, our data may suggest that reduced TMT-B com- factor models. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2001; 23:

pletion times for more educated subjects overestimate 274–284.

the effect of educational level. Another possibility is 11. Goul WR, Brown M. Effects of age and intelligence on

trail making test performance and validity. Percept. Mot.

that although executive function is influenced by edu-

Skills 1970; 30: 319–326.

cational level, the effect might not have been detect-

12. Kennedy KJ. Age effects on trail making test perfor-

able statistically because of the small sample size of the mance. Percept. Mot. Skills 1981; 52: 671–675.

low educational level group (n = 12). In addition, a rel- 13. Stanton BA, Jenkins CD, Savageau JA, Zyzanski SJ,

atively large number of subjects with low educational Aucoin R. Age and educational differences on the trail

level (approx. 20% of the 6-years group) were unable making test and Wechsler memory scales. Percept. Mot.

to complete TMT-B. However, differences in the indi- Skills 1984; 58: 311–318.

ces of executive function were not found between the 14. Stuss DT, Stethem LL, Poirier CA. Comparison of three

8-years and ≥10-years groups, and hence further work tests of attention and rapid information processing across

is needed to confirm the relationship between educa- six age groups. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1987; 1: 139–152.

tion and executive function as measured by TMT-B. 15. Ivnik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE et al. Neuropsychological

tests’ norms above age 55: COWAT, BNT, MAE Token,

WRAT-R Reading, AMNART, Stroop, TMT and JLO.

Clin. Neuropsychol. 1996; 10: 262–278.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 16. Giovagnoli AR, Del Pesce M, Mascheroni S, Simoncelli

We are grateful to all staff members of the Tajiri SKIP M, Laiacona M, Capitani E. Trail making test: normative

Center. values from 287 normal adult controls. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci.

1996; 17: 305–309.

17. Tombaugh TN. Trail making test A and B: normative

REFERENCES data stratified by age and education. Arch. Clin. Neurop-

sychol. 2004; 19: 203–214.

1. Flicker C, Ferris SH, Reisberg B. Mild cognitive impair- 18. Abe M, Suzuki K, Okada K et al. Normative data on tests

ment in the elderly: predictors of dementia. Neurology for frontal lobe functions: trail making test, verbal flu-

1991; 41: 1006–1009. ency, Wisconsin card sorting test (Keio version). No To

2. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC et al. Mild cognitive Shinkei 2004; 57: 567–574 (in Japanese).

impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. 19. Bornstein RA, Suga LJ. Educational level and neurop-

Neurol. 1999; 56: 303–308. sychological performance in healthy elderly subjects.

3. Chen P, Ratcliff G, Belle S et al. Cognitive tests that best Dev. Neuropsychol. 1988; 4: 17–22.

discriminate between presymptomatic AD and those 20. Ernst J. Neuropsychological problem-solving skills in the

who remain nondemented. Neurology 2000; 55: 1847– elderly. Psychol. Aging 1987; 2: 363–365.

1853. 21. Shimoyama I, Ninchoji T, Uemura K. The finger-tapping

4. Albert MS, Moss MB, Tanzi R et al. Preclinical predic- test: a quantitative analysis. Arch. Neurol. 1990; 47: 681–

tion of AD using neuropsychological tests. J. Int. Neu- 684.

ropsychol. Soc. 2001; 7: 631–639. 22. Meguro K, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S et al. Prevalence of

5. Kaskie B, Storandt M. Visuospatial deficit in dementia of dementia and dementing diseases in Japan: the Tajiri

the Alzheimer type. Arch. Neurol. 1995; 52: 422–425. Project. Arch. Neurol. 2002; 59: 1109–1114.

6. Sato M, Meguro K, Ishizaki J et al. Early detection of 23. Hughes C, Berg L, Danziger WL et al. A new clinical

patients with Alzheimer’s disease with the Benton Visual scale for the staging of dementia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1982;

Form Discrimination Test. Jpn. J. Neuropsychol. 2001; 17: 140: 566–572.

62–68 (in Japanese). 24. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): cur-

7. Sliwinski M, Lipton RB, Buschke H, Stewart W. The rent version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993; 43: 2412–

effect of preclinical dementia on estimates of normal 2414.

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

428 R. Hashimoto et al.

25. Spreen O, Strauss E. A Compendium of Neuropsycho- 27. Tisserand DJ, Van Boxtel MPJ, Pruessner JC et al. A

logical Tests: Administration, Norms and Commentary, voxel-based morphometric study to determine individual

2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, 1998. differences in gray matter density associated with age

26. Stuss DT, Bisschop SM, Alexander MP, Levine B, and cognitive change over time. Cereb. Cortex 2004; 14:

Izukawa D. The trail making test: a study in focal lesion 966–973.

patients. Psychol. Assess. 2001; 13: 230–239.

© 2006 The Authors

Journal compilation © 2006 Folia Publishing Society

You might also like

- Periop StandardsDocument334 pagesPeriop Standardsaran_gallur100% (3)

- Baremos Españoles TMTDocument15 pagesBaremos Españoles TMTMarta Olivera AymerichNo ratings yet

- TMT OralDocument7 pagesTMT OralVerónica Analía FrancoNo ratings yet

- ผลงานวิจัย Wp RbDocument7 pagesผลงานวิจัย Wp RbMuhammad Ilham MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal GerontikDocument9 pagesJurnal GerontikMuhammad KhalidNo ratings yet

- Rsultados Cognitivos en Niños Después de Tce. Rev Sistematica y MetaanalisisDocument7 pagesRsultados Cognitivos en Niños Después de Tce. Rev Sistematica y Metaanalisismaría del pinoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Functions of Children With Brain TumorDocument9 pagesCognitive Functions of Children With Brain TumorBambang WarsitoNo ratings yet

- Klotzbier, Etal 2017Document16 pagesKlotzbier, Etal 2017LAURA CRISTINA TORRES LÓPEZNo ratings yet

- NurobiologyDocument6 pagesNurobiologyDuglas Liam Quintanilla VelazcoNo ratings yet

- Attention and Working Memory Deficits in Mild Cognitive ImpairmentDocument9 pagesAttention and Working Memory Deficits in Mild Cognitive ImpairmentsoniaNo ratings yet

- Yang Et Al. 2022 Otago Exercise Programme - Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesYang Et Al. 2022 Otago Exercise Programme - Systematic ReviewClarissa LimNo ratings yet

- (MOCA) - Artículo China.Document6 pages(MOCA) - Artículo China.Shirley Gaviria GonzalezNo ratings yet

- tmpC0EE TMPDocument9 pagestmpC0EE TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Eli Oamjms2017 202vDocument5 pagesEli Oamjms2017 202vRifqi Hamdani PasaribuNo ratings yet

- Archives of Gerontology and GeriatricsDocument9 pagesArchives of Gerontology and GeriatricsHélio YoshidaNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Relationship Between Cognitive Performance and Function in Daily Life After Traumatic Brain InjuryDocument11 pagesUnderstanding The Relationship Between Cognitive Performance and Function in Daily Life After Traumatic Brain InjuryKatia DjerroudNo ratings yet

- Predicting Age From Brain EEG Signals-A Machine Learning ApproachDocument12 pagesPredicting Age From Brain EEG Signals-A Machine Learning ApproachdonsuniNo ratings yet

- Impact of Physical Frailty On Disability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument9 pagesImpact of Physical Frailty On Disability in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Prospective Cohort StudyRizky Dwi EffendyNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@gps 3787Document7 pages10 1002@gps 3787Gabriel VelozoNo ratings yet

- ArtikelDocument6 pagesArtikeljeinzen14No ratings yet

- Costa2014 Article StandardizationAndNormativeDatDocument8 pagesCosta2014 Article StandardizationAndNormativeDatDaniele La BellaNo ratings yet

- Watsu CPDocument6 pagesWatsu CP黃姵儒No ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity Tests of An Evaluation Tool Based On The Modified Barthel IndexDocument8 pagesReliability and Validity Tests of An Evaluation Tool Based On The Modified Barthel Indexlolocy LNo ratings yet

- Motor Learning and Movement Performance: Older Versus Younger AdultsDocument8 pagesMotor Learning and Movement Performance: Older Versus Younger AdultsJazmine CofrerosNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Training2Document3 pagesCognitive Training2gerson_janczuraNo ratings yet

- Skeletal Muscle Mass Index Cut-Offs by Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis To Determine Sarcopenia Based On Healthy Young or Old Populations. A Comparative StudyDocument8 pagesSkeletal Muscle Mass Index Cut-Offs by Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis To Determine Sarcopenia Based On Healthy Young or Old Populations. A Comparative StudyJohan Sebastian VilladaNo ratings yet

- Bhu 023Document11 pagesBhu 023Recehan CryptoNo ratings yet

- MSE Research 1Document11 pagesMSE Research 1kuro hanabusaNo ratings yet

- Healthy and Unhealthy Aging IAGMH INTAS Award ScTiwari, RK Tripathi Aditya KumarDocument30 pagesHealthy and Unhealthy Aging IAGMH INTAS Award ScTiwari, RK Tripathi Aditya KumarDr. Rakesh Kumar TripathiNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology: Merve Çebi, Gülsen Babacan, Öget Öktem Tanör & Hakan GürvitDocument10 pagesJournal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology: Merve Çebi, Gülsen Babacan, Öget Öktem Tanör & Hakan GürvitDR RISKA WAHYUNo ratings yet

- Hatta 2018Document8 pagesHatta 2018Quynh NguyenNo ratings yet

- 5 - Yadav Sunita. Correlation of Balance Tests Scores With Modified Physical Performance Test in Indian Community-Dwelling Older AdultsDocument19 pages5 - Yadav Sunita. Correlation of Balance Tests Scores With Modified Physical Performance Test in Indian Community-Dwelling Older AdultsDr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- 27891-Texto Del Artículo-88926-1-10-20220427Document12 pages27891-Texto Del Artículo-88926-1-10-202204274UNo ratings yet

- Motor Learning and Performance in Schizophrenia and Aging: Two Different Patterns of DeclineDocument21 pagesMotor Learning and Performance in Schizophrenia and Aging: Two Different Patterns of Decline4ymwg78wxcNo ratings yet

- Earlier Development of The Accumbens Relative To Orbitofrontal Cortex Might Underlie Risk-Taking Behavior in AdolescentsDocument8 pagesEarlier Development of The Accumbens Relative To Orbitofrontal Cortex Might Underlie Risk-Taking Behavior in AdolescentsDarwin 1No ratings yet

- 21272-Article Text-45787-1-10-20140829Document16 pages21272-Article Text-45787-1-10-20140829Zul FahmiNo ratings yet

- Gait & PostureDocument6 pagesGait & PostureEman Abd ELbadieNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy and Yoga For Children With AuDocument4 pagesOccupational Therapy and Yoga For Children With Auvidyakumar238No ratings yet

- Cognitive Interventions in Healthy Older Adults and People With Mild Cognitive Impairment - A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesCognitive Interventions in Healthy Older Adults and People With Mild Cognitive Impairment - A Systematic Reviewmadalena limaNo ratings yet

- Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics: A C D A BDocument10 pagesArchives of Gerontology and Geriatrics: A C D A BIsabelNo ratings yet

- Aerobic ExerciseDocument9 pagesAerobic Exercisebiahonda15No ratings yet

- Fnagi 14 911559Document17 pagesFnagi 14 911559Patrícia BodoniNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis: ReviewDocument13 pagesCognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis: ReviewSarah Miryam CoffanoNo ratings yet

- Zhang2020 Article ExecutiveFunctionInHigh-FunctiDocument17 pagesZhang2020 Article ExecutiveFunctionInHigh-FunctiEccoNo ratings yet

- BrainAge Brandon PDFDocument9 pagesBrainAge Brandon PDFdonsuniNo ratings yet

- Cognitiveplasticity in People at Risk For DementiaDocument8 pagesCognitiveplasticity in People at Risk For DementiaRegistro psiNo ratings yet

- Tibial Plateau Fractures in Older Adults Are Associated With A Clinically Significant Deterioration in Health-Related Quality of LifeDocument10 pagesTibial Plateau Fractures in Older Adults Are Associated With A Clinically Significant Deterioration in Health-Related Quality of LifeShiv KolheNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Kinesio Taping On Sitting Posture, Functional Independence and Gross Motor Function in Children With Cerebral PalsyDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Kinesio Taping On Sitting Posture, Functional Independence and Gross Motor Function in Children With Cerebral PalsyMina RizqinaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Reserve and Long-Term Change in Cognition in Aging and Preclinical Alzheimer's DiseaseDocument9 pagesCognitive Reserve and Long-Term Change in Cognition in Aging and Preclinical Alzheimer's Diseasechepin ChangNo ratings yet

- Perceived Age As Clinically Useful Biomarker of Ageing - Cohort StudyDocument8 pagesPerceived Age As Clinically Useful Biomarker of Ageing - Cohort Studytedsm55458No ratings yet

- Measurement of Development of Cognitive and Attention Functions in ChildrenDocument7 pagesMeasurement of Development of Cognitive and Attention Functions in ChildrenAnton HrivnákNo ratings yet

- Symptoms of Depression and Cognitive Impairment in Young Adults After Sroke or TiaDocument3 pagesSymptoms of Depression and Cognitive Impairment in Young Adults After Sroke or TiaKhaziatun NurNo ratings yet

- 2010 Article 186Document6 pages2010 Article 186Hervina22No ratings yet

- Mrazik, 2010 - TMT OralDocument8 pagesMrazik, 2010 - TMT OralMica Ballito de TroyaNo ratings yet

- Ebmental 2022 300439.fullDocument8 pagesEbmental 2022 300439.fullJorge Luis GonzalezNo ratings yet

- The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia. Normative Data For The Italian PopulationDocument9 pagesThe Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia. Normative Data For The Italian PopulationMAGALYNo ratings yet

- Fragi 02 636390Document11 pagesFragi 02 636390msNo ratings yet

- Rasmusson-1998-Effects of Age and Dementia OnDocument11 pagesRasmusson-1998-Effects of Age and Dementia OnerinfearnsmithNo ratings yet

- Moretti 2011Document9 pagesMoretti 2011yma ymiiNo ratings yet

- Estimulacion Cognitiva en Adultos MayoresDocument46 pagesEstimulacion Cognitiva en Adultos MayoresVinicioMagañaNo ratings yet

- PSP Rabbit Il MdaDocument4 pagesPSP Rabbit Il MdaStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Issues in The Older AdultDocument28 pagesCognitive Issues in The Older AdultStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- Changes in Executive Function After Acute Bouts of Passice Cycling in Parkinsons DiseaseDocument13 pagesChanges in Executive Function After Acute Bouts of Passice Cycling in Parkinsons DiseaseStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- TCD Screening For Pfo ClosureDocument5 pagesTCD Screening For Pfo ClosureStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- Combination of CTCD Ctte CtoeDocument7 pagesCombination of CTCD Ctte CtoeStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- Scoring System Identification of High-Risk Patent Foramen Ovale With CSDocument6 pagesScoring System Identification of High-Risk Patent Foramen Ovale With CSStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- Randomized Double Blind Placebo-Controlled Study On Effects of Raloxifene and HRT On Plasma NO ConcentrationsDocument8 pagesRandomized Double Blind Placebo-Controlled Study On Effects of Raloxifene and HRT On Plasma NO ConcentrationsStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- Build Your Own Pasta: Buy 4 Only ForDocument6 pagesBuild Your Own Pasta: Buy 4 Only ForStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- The Fundamentals of Critical Care Support Local ExDocument4 pagesThe Fundamentals of Critical Care Support Local ExStefanie KarinaNo ratings yet

- 5534 21456 1 PBDocument8 pages5534 21456 1 PBAkhawat Ahir ZamanNo ratings yet

- Intra-Abdominal Infections: Resident's Lecture Edward L. Goodman, MD May 1, 2006Document36 pagesIntra-Abdominal Infections: Resident's Lecture Edward L. Goodman, MD May 1, 2006srweaverNo ratings yet

- AzathioprineDocument3 pagesAzathioprinesky.blueNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Deficit Related To HypertensionDocument2 pagesKnowledge Deficit Related To HypertensionChenee Mabulay100% (1)

- Art DrugsDocument70 pagesArt DrugsDr Daulat Ram DhakedNo ratings yet

- Ipgme&r Opd ScheduleDocument8 pagesIpgme&r Opd Schedulean o nymousNo ratings yet

- Management TB MOH Singapore PDFDocument123 pagesManagement TB MOH Singapore PDFLindsley GruvyNo ratings yet

- Duttons Introductory Skills and Procedures For The Physical Therapist Assistant 1St Edition Mark Dutton Full ChapterDocument51 pagesDuttons Introductory Skills and Procedures For The Physical Therapist Assistant 1St Edition Mark Dutton Full Chaptersusie.blankenship630100% (6)

- Compreh Homeop Mat Med of Mind HChitkara PDFDocument6 pagesCompreh Homeop Mat Med of Mind HChitkara PDFcgarciNo ratings yet

- Intravenous Injection: Presented by Mrs. Silpa Jose T Assistant Professor STCON, KattanamDocument33 pagesIntravenous Injection: Presented by Mrs. Silpa Jose T Assistant Professor STCON, KattanamSilpa Jose TNo ratings yet

- Trauma Thoraks PDFDocument86 pagesTrauma Thoraks PDFMiftahurrahmiNo ratings yet

- HemiparesisDocument35 pagesHemiparesisIsabela IacobNo ratings yet

- Regional AnesthesiaDocument33 pagesRegional Anesthesiashaq545No ratings yet

- LongCase Retinoblastoma GebiDocument45 pagesLongCase Retinoblastoma GebiAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- RX - Citicoline, Kalium, Ketosteril, Methycobal, Myonal, Lipolin GelDocument6 pagesRX - Citicoline, Kalium, Ketosteril, Methycobal, Myonal, Lipolin GelntootNo ratings yet

- Skin Assessment ActivityDocument6 pagesSkin Assessment ActivityRenee Dwi Permata MessakaraengNo ratings yet

- (50 Studies Every Doctor Should Know (Series)) Ashaunta T. Anderson, Nina L. Shapiro, Stephen C. Aronoff, Jeremiah Davis, Michael Levy, Michael E. Hochman-50 Studies Every Pediatrician Should Know-OxfDocument361 pages(50 Studies Every Doctor Should Know (Series)) Ashaunta T. Anderson, Nina L. Shapiro, Stephen C. Aronoff, Jeremiah Davis, Michael Levy, Michael E. Hochman-50 Studies Every Pediatrician Should Know-OxfMarcos R Galvão BatistaNo ratings yet

- Andi Muh. Octavian Pratama Et Anwar Lewa-1Document9 pagesAndi Muh. Octavian Pratama Et Anwar Lewa-1octavian pratamaNo ratings yet

- ITI Study Club-May EventDocument2 pagesITI Study Club-May EventS. BenzaquenNo ratings yet

- Lecture - 6-7 - Chronic Apical Periodontitis. Clinical Signs, Diagnostic MethodsDocument40 pagesLecture - 6-7 - Chronic Apical Periodontitis. Clinical Signs, Diagnostic MethodsA.J. YounesNo ratings yet

- Nursing ResumeDocument1 pageNursing Resumeapi-383929607No ratings yet

- Arakaki 2017Document8 pagesArakaki 2017Gabriella Kezia LiongNo ratings yet

- Common Dermatology Multiple Choice Questions and Answers - 6Document3 pagesCommon Dermatology Multiple Choice Questions and Answers - 6Atul Kumar Mishra100% (1)

- SonotronDocument10 pagesSonotronSyafiq YusryNo ratings yet

- EHS Groin Hernia ClassificationDocument4 pagesEHS Groin Hernia ClassificationbogdanotiNo ratings yet

- Collagenase For Enzymatic Debridement A.2Document8 pagesCollagenase For Enzymatic Debridement A.2Agung GinanjarNo ratings yet

- Real Time Health Monitoring System Through Iot Using SensorsDocument6 pagesReal Time Health Monitoring System Through Iot Using Sensorsقابوس الليثيNo ratings yet

- Smallintestinalbacterial Overgrowth: Daniel Bushyhead,, Eamonn M. QuigleyDocument12 pagesSmallintestinalbacterial Overgrowth: Daniel Bushyhead,, Eamonn M. QuigleyHugo MoralesNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Operations and Procedures - CompleteDocument46 pagesObstetric Operations and Procedures - CompleteMax ZealNo ratings yet