Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Angst LoudmouthFeministsUnchaste 2009

Angst LoudmouthFeministsUnchaste 2009

Uploaded by

Alba SanchezCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Sheraton: Employment Contract/Service AgreementDocument1 pageSheraton: Employment Contract/Service AgreementSURYA100% (2)

- Women’s War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil WarFrom EverandWomen’s War: Fighting and Surviving the American Civil WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- New Zealand Corporate GovernmentDocument12 pagesNew Zealand Corporate GovernmentWakeUpKiwi100% (1)

- Issei, Nisei, War Bride: Three Generations of Japanese American Women in Domestic ServiceFrom EverandIssei, Nisei, War Bride: Three Generations of Japanese American Women in Domestic ServiceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Financial Analysis of Adani EnterprisesDocument11 pagesFinancial Analysis of Adani EnterprisesChinmay Prusty50% (2)

- A Woman's War, Too: Women at Work During World War IIFrom EverandA Woman's War, Too: Women at Work During World War IIRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Park Statue Politics1 E IRDocument145 pagesPark Statue Politics1 E IRlbburgessNo ratings yet

- Comfort WomenDocument7 pagesComfort WomenAradhya JainNo ratings yet

- Ikorean "Comfort Women": The Intersection of Colonial Power, Gender, and ClassDocument21 pagesIkorean "Comfort Women": The Intersection of Colonial Power, Gender, and ClassLee McKinnisNo ratings yet

- R&R at The Intersection of US and Japanese Dual Empire - Okinawan Women andDocument10 pagesR&R at The Intersection of US and Japanese Dual Empire - Okinawan Women andAlba SanchezNo ratings yet

- Comfort Women NOT Sex Slaves: Rectifying the Myriad of Perspectives Second EditionFrom EverandComfort Women NOT Sex Slaves: Rectifying the Myriad of Perspectives Second EditionNo ratings yet

- Comfort WomenDocument19 pagesComfort WomenJohn ToledoNo ratings yet

- HERCWAv 1Document25 pagesHERCWAv 1Fatima Princess MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Women and War in Japan, 1937 - 1945Document23 pagesWomen and War in Japan, 1937 - 1945vietanh.contactandworkNo ratings yet

- Wwii “Korean Women Not Sex-Enslaved”: A Myth-Bust!From EverandWwii “Korean Women Not Sex-Enslaved”: A Myth-Bust!Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Why 'Comfort Women' Deal Doesn't Shut Book On Japan's Wartime Sex SlaveryDocument5 pagesWhy 'Comfort Women' Deal Doesn't Shut Book On Japan's Wartime Sex SlaverydfsNo ratings yet

- The Unfold Story of War Brides: Manar Taha ElshaibDocument35 pagesThe Unfold Story of War Brides: Manar Taha ElshaibTanishq Kamboj100% (2)

- Feminine Subcultures in Japan: Transgressions and ObsessionsDocument19 pagesFeminine Subcultures in Japan: Transgressions and ObsessionsNirupama ChandrasekharNo ratings yet

- Haunted by Defeat: Imperial Sexualities, Prostitution, and The Emergence of Postwar JapanDocument28 pagesHaunted by Defeat: Imperial Sexualities, Prostitution, and The Emergence of Postwar Japankunstart. JJ.No ratings yet

- Alegal: Biopolitics and the Unintelligibility of Okinawan LifeFrom EverandAlegal: Biopolitics and the Unintelligibility of Okinawan LifeNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Movement To Correct HistoryDocument9 pagesThe Japanese Movement To Correct Historyrodriguesfortes6711No ratings yet

- Geisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star: A Woman, Sex, and Morality in Modern JapanFrom EverandGeisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star: A Woman, Sex, and Morality in Modern JapanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Sex in Japan - It - S A Straight Man - S WorldDocument38 pagesSex in Japan - It - S A Straight Man - S WorldAkash PatilNo ratings yet

- Nwa DCDocument14 pagesNwa DCTobechukwu IbenyeNo ratings yet

- Soldaderas and Feminists in Revolutionary MexicoDocument72 pagesSoldaderas and Feminists in Revolutionary MexicoMarcela100% (1)

- The First MeToo Activists Contemporary CDocument12 pagesThe First MeToo Activists Contemporary CBruna CasariniNo ratings yet

- The Weaker Sex in War: Gender and Nationalism in Civil War VirginiaFrom EverandThe Weaker Sex in War: Gender and Nationalism in Civil War VirginiaNo ratings yet

- Kramm - SV Masc AgencyDocument25 pagesKramm - SV Masc Agency奥村 シエル ミカエリスNo ratings yet

- Race for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War IIFrom EverandRace for Empire: Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War IIRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Comfort Women Not “Sex Slaves”: Rectifying the Myriad of PerspectivesFrom EverandComfort Women Not “Sex Slaves”: Rectifying the Myriad of PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- The Comfort Women: A History of Japenese Forced Prostitution During the Second World WarFrom EverandThe Comfort Women: A History of Japenese Forced Prostitution During the Second World WarNo ratings yet

- Pedagogy of Democracy: Feminism and the Cold War in the U.S. Occupation of JapanFrom EverandPedagogy of Democracy: Feminism and the Cold War in the U.S. Occupation of JapanNo ratings yet

- Feminism in Japan PDFDocument29 pagesFeminism in Japan PDFzeba abbas100% (1)

- Comfort Women 1Document17 pagesComfort Women 1matiasbenitez1992No ratings yet

- Chin - Comfort Women RBADocument14 pagesChin - Comfort Women RBAtj ayumbaNo ratings yet

- Japnse Ww2 CMFT Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesJapnse Ww2 CMFT Reaction PaperKane Francis VeranoNo ratings yet

- Comfort Women - The Unrelenting Oppression During and After WWIIDocument70 pagesComfort Women - The Unrelenting Oppression During and After WWIIPaloma Uahiba ArnoldsNo ratings yet

- Japanese Women: Lineage and LegaciesDocument89 pagesJapanese Women: Lineage and LegaciesThe Wilson CenterNo ratings yet

- Maehara 2001 Neogtiating Multiple Ethnic Identities The Case of Okinawan Women in The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesMaehara 2001 Neogtiating Multiple Ethnic Identities The Case of Okinawan Women in The PhilippinesJaja BarrigaNo ratings yet

- A Feminist Perspective in Ngugi Wa Thiong's Novel "Petal of Blood"Document5 pagesA Feminist Perspective in Ngugi Wa Thiong's Novel "Petal of Blood"IJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of ConscienceFrom EverandBeyond the Betrayal: The Memoir of a World War II Japanese American Draft Resister of ConscienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Japanese Concentration Camps and Their Effect On Mental HealthDocument7 pagesJapanese Concentration Camps and Their Effect On Mental HealthJanet Varela GaristaNo ratings yet

- After the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My LaiFrom EverandAfter the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My LaiRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Comfort Women and Rape As A Weapon of WarDocument34 pagesComfort Women and Rape As A Weapon of WarPotomacFoundationNo ratings yet

- Inquiring of Park Yu-Ha, The Counsel of The Empire: 1. BackgroundDocument7 pagesInquiring of Park Yu-Ha, The Counsel of The Empire: 1. Backgroundroberto86No ratings yet

- 126-131 Sadiya Nair SDocument6 pages126-131 Sadiya Nair SEhsanNo ratings yet

- Through the Valley of the Shadow: Australian Women in War-Torn ChinaFrom EverandThrough the Valley of the Shadow: Australian Women in War-Torn ChinaNo ratings yet

- Shame and Silencing of Amejo in Okinawa - Examining Gendered and MDocument33 pagesShame and Silencing of Amejo in Okinawa - Examining Gendered and MAlba SanchezNo ratings yet

- Making Home from War: Stories of Japanese American Exile and ResettlementFrom EverandMaking Home from War: Stories of Japanese American Exile and ResettlementNo ratings yet

- Naomi, A Symbol of Women's LiberationDocument7 pagesNaomi, A Symbol of Women's LiberationLorenzo Wa NancyNo ratings yet

- Modern Girls on the Go: Gender, Mobility, and Labor in JapanFrom EverandModern Girls on the Go: Gender, Mobility, and Labor in JapanNo ratings yet

- NGO Edson Karl Diaz Comfort WomenDocument2 pagesNGO Edson Karl Diaz Comfort WomenEDSON KARL NGONo ratings yet

- Power, Subversion, and Containment: A New Historicist Interpretation of The VirginianDocument6 pagesPower, Subversion, and Containment: A New Historicist Interpretation of The Virginianignooyrant sinnerNo ratings yet

- Broken Silence Redressing The Mass Rape and Sexual Enslavement of Asian Women by The Japanese Government in An Appropriate ForumDocument33 pagesBroken Silence Redressing The Mass Rape and Sexual Enslavement of Asian Women by The Japanese Government in An Appropriate ForumSzilágyi OrsolyaNo ratings yet

- Solidarity - Women and ViolenceDocument44 pagesSolidarity - Women and ViolenceSolidarityUSNo ratings yet

- You're Attempt To Prioritize Extinction Over Structural Criticisms Reifies Antiblackness by Using Military Terror To Destroy Meaningful ResistanceDocument3 pagesYou're Attempt To Prioritize Extinction Over Structural Criticisms Reifies Antiblackness by Using Military Terror To Destroy Meaningful ResistanceNelson OkunlolaNo ratings yet

- History of FeminismDocument26 pagesHistory of FeminismMerna Kusuma100% (1)

- The Truth of The "Comfort Women" Intelligence WarfareDocument23 pagesThe Truth of The "Comfort Women" Intelligence WarfaresupernewnewNo ratings yet

- ComparisonDocument5 pagesComparisonRaeesa RiazNo ratings yet

- How To Use The Proportional Vacation Pay (PVP) Forms: in 3 Copies ON OR BEFORE MAY - , 2016Document20 pagesHow To Use The Proportional Vacation Pay (PVP) Forms: in 3 Copies ON OR BEFORE MAY - , 2016Rupelma Salazar Patnugot0% (1)

- JP Morgan Chase & CoDocument11 pagesJP Morgan Chase & CoDinesh PendyalaNo ratings yet

- IV.4 The Lawyer and The Client (C14-C18)Document202 pagesIV.4 The Lawyer and The Client (C14-C18)MikhoYabutNo ratings yet

- EN - CVE DetailsDocument4 pagesEN - CVE DetailsGiorgi RcheulishviliNo ratings yet

- H100Manual PDFDocument33 pagesH100Manual PDFKang Ray MonthNo ratings yet

- FBI (FOUO) Identification of Websites Used To Pay Protestors and Communication Platforms To Plan Acts of Violence PDFDocument5 pagesFBI (FOUO) Identification of Websites Used To Pay Protestors and Communication Platforms To Plan Acts of Violence PDFWilliam LeducNo ratings yet

- National Bankruptcy Services The LedgerDocument28 pagesNational Bankruptcy Services The LedgerOxigyneNo ratings yet

- American ExpreesDocument11 pagesAmerican ExpreesShikha Varshney0% (1)

- Texas Certified Lienholders ListDocument62 pagesTexas Certified Lienholders ListJose CeceñaNo ratings yet

- Week5 Law 122 Updated DBDocument57 pagesWeek5 Law 122 Updated DBsyrolin123No ratings yet

- Cheque Bounce CaseDocument2 pagesCheque Bounce CasepreethiNo ratings yet

- Please Bring This Receipt For Report Collection: Bill of Supply/Cash ReceiptDocument2 pagesPlease Bring This Receipt For Report Collection: Bill of Supply/Cash ReceiptBang ManNo ratings yet

- Factsheet-Entrepreneur Transformation Ka GurukulDocument4 pagesFactsheet-Entrepreneur Transformation Ka GurukulJay Kumar BhattNo ratings yet

- Sweepstakes RulesDocument4 pagesSweepstakes RulesRocketLawyerNo ratings yet

- Swagatam Letter of Quess CompanyDocument6 pagesSwagatam Letter of Quess Companydubey.princesriNo ratings yet

- SUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED VOLUME 626 Case 10Document29 pagesSUPREME COURT REPORTS ANNOTATED VOLUME 626 Case 10Marie Bernadette BartolomeNo ratings yet

- The Responsive Community JournalDocument144 pagesThe Responsive Community JournalMarceloNo ratings yet

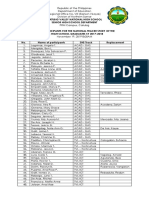

- Catubig Valley National High School Senior High School DepartmentDocument1 pageCatubig Valley National High School Senior High School DepartmentDerickNo ratings yet

- Storming Juno Assignment PDFDocument2 pagesStorming Juno Assignment PDFbisbiusaNo ratings yet

- Agreement SampleDocument4 pagesAgreement SampleG.D SinghNo ratings yet

- Grave Oral Defamation CasesDocument25 pagesGrave Oral Defamation Casesaj salazarNo ratings yet

- Wide Flange Beam Specifications Chart - South El Monte, CADocument3 pagesWide Flange Beam Specifications Chart - South El Monte, CAToniNo ratings yet

- ZXHN F600 PON ONT User ManualDocument9 pagesZXHN F600 PON ONT User ManualHimanshu SahaNo ratings yet

- Withdrawal of SuitDocument3 pagesWithdrawal of Suitshabnam BarshaNo ratings yet

- Prohibition On Movement of Vessels in Waters Surrounding: (A) Jurong Island (B) Pulau Busing & Pulau Bukom (C) Pulau Sebarok & Shell SBM and (D) Sembawang Wharves and Approaches TheretoDocument8 pagesProhibition On Movement of Vessels in Waters Surrounding: (A) Jurong Island (B) Pulau Busing & Pulau Bukom (C) Pulau Sebarok & Shell SBM and (D) Sembawang Wharves and Approaches TheretohutuguoNo ratings yet

- Edited JudicialAffidavit GissyGaudielDocument4 pagesEdited JudicialAffidavit GissyGaudielGissy GaudielNo ratings yet

- Mr. Quek Ghee Han: TAX INVOICE (Finalised)Document3 pagesMr. Quek Ghee Han: TAX INVOICE (Finalised)quekgheehanNo ratings yet

Angst LoudmouthFeministsUnchaste 2009

Angst LoudmouthFeministsUnchaste 2009

Uploaded by

Alba SanchezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Angst LoudmouthFeministsUnchaste 2009

Angst LoudmouthFeministsUnchaste 2009

Uploaded by

Alba SanchezCopyright:

Available Formats

Loudmouth Feminists and Unchaste Prostitutes: "Bad Girls" Misbehaving in Postwar

Okinawa

Author(s): Linda Isako Angst

Source: U.S.-Japan Women's Journal , 2009, No. 36 (2009), pp. 117-141

Published by: University of Hawai'i Press on behalf of International Institute of Gender

and Media

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42771995

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

and University of Hawai'i Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to U.S.-Japan Women's Journal

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Loudmouth Feminists and Unchaste Prostitutes:

"Bad Girls" Misbehaving in Postwar Okinawa

Linda Isako Angst

Daughters, Chaste and Otherwise

The problem of U.S. bases in Okinawa and the abusive behavior of their occupants

toward the local population, in particular its women, is also found in other parts of East

Asia that have long been occupied by the U.S. military, most notably South Korea. The

rape of a 14-year-old schoolgirl in Okinawa in February 2008, and her decision to drop

charges in the face of widespread publicity and the unlikelihood of satisfactory redress,

is an example of the tragedy that can strike women and girls in areas occupied by foreign

military troops.1 In this article I draw on current feminist theory on U.S. militarization

in East Asia to focus on two groups of women- prostitutes and feminist activists- who

together comprise the so-called bad girls of Okinawa. As will be seen, both groups owe

their existence to the military bases that have covered 20 percent of this small island

prefecture since the end of World War II.

Originally the independent Kingdom of the Ryukyus, Okinawa was annexed in

1879 by the Japanese state. The smallest and newest of Japan's prefectures, it was

reincorporated into Japan in 1972, after reversion from U.S. military jurisdiction. Though

it represents less than 1 percent of the land area of Japan, it houses 75 percent of the U.S.

Linda Isako Angst is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Lewis and Clark College, Portland,

Oregon. Her areas of interest encompass Okinawan women's narratives, war memory, military

occupation and everyday forms of violence; Japanese peace museums; and longevity and wellness

tourism in Okinawa. She is the author of "The Sacrifice of a Schoolgirl: The 1995 Rape Case,

Discourses of Power, and Women's Lives in Okinawa," Critical Asian Studies 33, no. 2 (June

2001) and In a Dark Time: Memory, Community, and Gendered Nationalism in Postwar Okinawa

(forthcoming from Harvard University Press).

© 2009 by Jösai International Center for the Promotion of Art and Science, Jõsai University

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

118 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

troops that the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty (AMPO) mandates. Okinawa has remained

a primary launching pad for deployments to the various conflicts in which the U.S. has

been engaged since 1945, including the Korean, Vietnam, and Persian Gulf wars and the

current conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is in this context that I discuss the categories

of Okinawan feminists and prostitutes.

I identify these women as occupying what may be thought of as opposite ends of

a perceived socio-economic-moral continuum. In this scenario, feminists represent what

can be interpreted as women's agency par excellence, through their "in-your-face" tactics

of proactive social reform (especially in terms of public support for a rape crisis center

and protections for sex workers) and political protest (against the presence of U.S. bases

and, in 1 995, in support of an earlier schoolgirl who was gang raped by U.S. servicemen).

Prostitutes, in contrast, are symbols of social degradation, although they, too, can be

understood to occupy a position of agency, inasmuch as their profession can be (though

not always is) a source of independent livelihood. Ultimately, however, the selling and

buying of their bodies positions these women as objects and renders them vulnerable to

being victimized. The degree of freedom they have in choosing this particular livelihood

is exactly countered by the fact that they can do so only at the expense of their personal

integrity. Yet rather than being viewed sympathetically, as victims of a set of socio-political-

economic circumstances in which they were forced to sell their bodies to support their

families in impoverished early postwar Okinawa, prostitutes are stigmatized as occupying

the lowest rung on the social ladder.

How do we situate the narratives of women who have made the ultimate sacrifice

for family within the larger story of Okinawan identity politics? What is that story,

and how can we understand the role of feminist activists in the postwar economy in

light of this?

Despite the fact that their sacrifices are very real, prostitutes in Okinawa are

excluded from the island's emblematic category of the sacrificed daughter- the story

that most poignantly, persuasively, and prominently symbolizes Okinawa. This is the

story of Himeyuri ("Princess Lily"), the name given collectively to prewar Okinawa's

educated daughters who were students at the First Prefectural Women's Higher School.

They were called on to serve the Japanese state as wartime nurses during the bloody and

prolonged Battle of Okinawa (April-June 1945), where they died in large numbers.2 As

the representatives par excellence of the sacrificed daughter of the nationalist state, the

Himeyuri are revered symbols of Okinawan wartime sacrifice.

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 119

In stark contrast, the sacrifices made by women selling their bodies to support their

families in the postwar period are regarded as shameful. Who could be more deserving of

inclusion in the roster of sacrificed daughters than girls who had to become prostitutes to

help feed their parents and siblings during the hard years of the U.S. occupation of Okinawa

( 1 945-72)? Yet they remain socially stigmatized for work they were forced to undertake.

While the Himeyuri are romanticized as having made the tragic ultimate sacrifice of their

young lives, there is no similar redemptive narrative for girls and women of the peasant

classes who sacrificed their respectability for the sake of the family and, ultimately, for

the sake of the Okinawan people. It is because of the work these women undertook in

the camp-town economies around U.S. bases- in Okinawa and elsewhere- that their

families were eventually able to pull themselves out of poverty and begin to reclaim

decent lives.

How do we assess the image of chaste Okinawan women, who ostensibly require

the protection of the masculinist state, alongside the image of prostitutes, who are not only

denied such protection but are often seen as defying state authority by their very existence?

How do we situate feminists as yet another category of "bad girl," in comparison both to

the Himeyuri and to prostitutes?

Camp-Town Ladies

There are parallels in Okinawa to the popular narrative line about the Korean and Chinese

military sex slaves of Imperial Japan, euphemistically called "comfort women" (jugun

ianfu), who did not speak for decades about their wartime experiences because, we are

told, of the stigma. For the vast majority, it was coerced labor, not work they knowingly

entered into. Elaine H. Kim and Chungmoo Choi3 remind us, however, of the political-

economic conditions that also contributed to the women's long silence: in the post-Korean

War era of nation-building, it would have been impolitic for the South Korean military

government to jeopardize its relationship either with Japan, its former colonizer which

had enslaved these women and with which it needed to "normalize" relations, or with the

U.S., its neo-colonial occupier, which was there to help ensure democratic nation-building

and prevent incursions from communist North Korea and China.

Moreover, from the 1960s on, Japan engaged in what some Japan experts, such as

Patrick Smith and Yoshida Kensei,4 refer to as the selling-out of politics and citizen rights

in exchange for economic prosperity. The ongoing influence of the monarchy in the form

of the Showa Emperor, who was still in place as a primary Japanese cultural icon, also

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

120 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

cannot be underestimated. Protected by the U.S. from prosecution as a war criminal at the

end of World War II, Hirohito's presence encouraged the burgeoning of a strong political

conservatism, in particular what is called nihonjinron - the thesis of cultural nationalism,

the essentialist argument about Japanese uniqueness. One consequence of this extension

of imperial cultural power was that until Hirohito's death in 1989, speaking out about the

comfort women's history was virtually impossible. The harsh realities of U.S. camp-town

prostitutes were also likely to get scant attention.

In the work of Hyun Sook Kim on Korea, we learn that, "whether forcibly drafted

under colonial rule or driven by financial need in the neo-colonial period dependent

economy, and despite shifting discursive constructions of the nation, these women are

variously constructed as outcastes or as a trope of suffering nation."5 The comparison with

Okinawan prostitutes working in camp towns around Kadena Air Base, Camp Hansen,

Camp Butler, and other U.S. Marine, Army, Air Force, and Navy bases in Okinawa is

unavoidable, from the Korean War era through the Vietnam era and beyond. Moreover,

after Okinawa's reversion to Japanese sovereignty in 1972 and the end of the Vietnam

War in 1975, the Japanese government targeted Okinawa for development as a tourist

resort. The World Ocean Exposition of 1975 was the first official showcase of the island

as a prime tourist site. With the rise of a tourist industry in Okinawa in the early 1970s,

prostitution may not have declined, but the demographics shifted: in the post-reversion

economy, women began to come in, largely from Southeast Asia and the Philippines, to

service U.S. personnel and Japanese male tourists. Many Okinawan women in the bar

and brothel trade were able to buy their way out of the profession in these boom years.6

But not all women were so lucky, and aging Okinawan women veterans of Vietnam-era

prostitution can still be found working in the poorest urban areas.7

How have outspoken feminist activists and hard-working prostitutes in camp towns

around U.S. military bases been positioned- and how do they position themselves- within

a struggling tourist economy in which Okinawans both criticize the presence of the bases

and creatively seek to absorb them as a kind of dazzling/grotesque spectacle of an eclectic,

post-reversion Okinawan ambience?

Feminism vs. Nationalism

This article attempts to "address the entwined and conflicting projects of feminism and

nationalism," as Kim and Choi seek to do in their 1998 edited volume on Korea , Dangerous

Women, and to do so by contending "with the massive sex industry around U.S. military

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 121

camp towns scattered all over" not Korea in this case but Okinawa, where large numbers of

Okinawan women once served U.S. military personnel.8 The U.S. military base is the site

where the two quite different groups of in-your-face Okinawan women come together, so to

speak, although in reality they do not interact easily, if at all. For prostitutes, the economies

around U.S. bases are places of work and livelihood, usually a necessary evil. For Okinawan

feminists, engaged in a transnational campaign to make the world safer and more egalitarian

for women- and especially for sex workers on the margins of military bases- the project

is to rid the island of bases, as sites that epitomize the rapacity of U.S. imperialism for more

than sixty years, as manifested in direct assaults on the bodies of Okinawan women and girls.

Thus prostitutes and other women who are trapped in the marginalized sexual economy of

the military bases- and, increasingly, of the island's tourism- are the often unwitting and/or

unwilling objects of feminist campaigns.

These two unlikely groups are also linked by the fact that they are both undesirable

kinds of women within an anti-colonial nationalist discourse, a discourse that unifies

by "homogeniz[ing] the nation and normaliz[ing] women and women's chastity so that

they properly belong to the patriarchal order."9 In the patriarchal ideology of nationalist

discourse, male citizens are supposed to protect women and children from U.S. soldiers

and, perhaps lately, Japanese tourists:

Patriarchal ideology confers neither anti-colonial revolutionary agency nor autono-

mous subjectivity to women. Instead, the boundaries are drawn and the terms set by

a male elite, so that women, though always indispensable participants in a political

struggle, are relegated to the status of voiceless auxiliaries.10

It was the pressure by Okinawan feminists returning from the Fourth World Conference

on Women in Beijing in September 1995 that both brought to public attention the rape of

the schoolgirl by three U.S. servicemen and sought to protect the girl's privacy by asking

for the media's restraint in seeking to uncover her identity. Women had been involved

since before the reversion era in protests against U.S. military bases, but they had played

largely supporting roles, adding necessary bodies to protests that, for example, entailed

ringing Kadena Air Base in a human chain- a feat that required thousands of participants

because the perimeter is several miles long. Yet despite the facts that a rape crisis center

was established and some other conditions were met in response to the demands of the

outspoken women activists in 1995, little more was done once attention waned after the

initial frenzied media spotlight on Okinawa's plight.

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

122 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

Will male Okinawan leaders accommodate women's agendas if and when goals are

achieved for Okinawan society as a whole in the struggle for greater political autonomy

that includes the removal of military bases?

Okinawans have a pre-colonial history (until annexation in 1879) of accommodating

women in positions of religious power. In traditional Okinawan culture, a female virgin

served as religious advisor and political consort to her ruler brother. Village shamans are

women and continue to hold local respect." Yet Okinawans today, though still mindful of

women's leadership roles in religious practices and proud of their island's egalitarian tradition

of shared rule, are no less restrictive of women in contemporary politics than are mainland

Japanese. Thus traditional Okinawan culture has not been able to counter the specific forms

of patriarchy, influenced by the neo-Confucian values of its Japanese colonizers, under which

Okinawan women have had to live and work. Moreover, although Okinawan women were

raised under and influenced by American democratic educational philosophies and practices

during the occupation, as I argue elsewhere,12 they have also been subject to the racial and

gender biases of a masculinist postwar American military culture (like women in Korea under

the U.S. occupation). This is not to say that all U.S. servicemen have behaved badly, or that

all Okinawan women have experienced abuse. But it is nevertheless important to recognize

the systemic nature of patriarchy as an ideology that informs a general attitude.

As Choi and Kim rightly point out, "Feminism and nationalism are the antinomic

offspring of modernity." They go on to discuss feminism and nationalism in South Korea

in the following way:

Feminism as a project of modernity stands at odds with nationalism, which imagines

a fraternal community. On the one hand, nationalism, while emphasizing liberal

democratic notions of individual differences, has in fact reconstituted the class

hierarchy of the ancien regime. On the other hand, it is these very liberal democratic

notions that have been used to segregate gender and race in the interests of a unifying

ideology of the nation-state. . . .

Feminism in the colonies, having inherited this double legacy of discrimina-

tory gender and race politics, has either been subsumed under or subordinated to the

greater cause of national liberation, which usually imagines the liberation of men.

Women who brave these conflicting forces are at once endangered by and dangerous

to the integrity of the masculinist discourse of nationalism.13

This perception of nonconforming women can also be seen in mainland Japanese politics

and in Okinawa. In mainland Japan, for example, Tanaka Makiko, the woman who was

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 123

minister of foreign affairs under the first Koizumi government, was chastised for being

too outspoken, even though any politician must be assertive in order to be effective in

the Japanese Diet. And Doi Takako, the longtime head of the Japan Socialist Party, was

repeatedly subjected to public scrutiny and vile verbal hazing from her male colleagues

for, among many other things, resisting the dominant ideology that says women must be

married to be respectable. (Men, too, have been targeted for being single, although Prime

Minister Koizumi was perceived as a roguishly eligible bachelor as a divorced man. This

would be unimaginable for a woman.)

In Okinawa, some of the "dangerous women" are activists who, emboldened

by being elected into the ranks of policy makers, no longer feel compelled to take

their cues from male leaders. Rather, they assert their right to make statements in the

international media about the condition of women's lives in postwar Okinawa, as

longtime Naha City council woman Takazato Suzuyo did during the 1995 rape case

(discussed in more detail below).

Here it is important to remember the proliferation of bars and brothels both around

U.S. bases and in the new business areas catering to tourists. This is the underside of

Okinawa's post-reversion economy, in which some things simply never change for poor

women. Women who worked the bar scene during the Vietnam War era are now too old to

serve as hostesses in clubs. Some now own their establishments, but most work the trade

as they can, such as on "flute alley," where on the two paydays of the month, in cities

like Koza and Kin, long lines of men can be seen waiting in the settling dusk outside of

what appear earlier in the day to be colorful garage doors. At these times women can turn

quick tricks (providing only oral sex service) in dark "rooms"- really only antechambers

or entrance areas (genkan)- in fairly rapid succession.

In contrast, younger women who enter, or find themselves in, the business of

prostitution are increasingly (though not exclusively) from outside Okinawa, pointing to

the transnational political economy of prostitution that now operates there. Clearly, these

women from outside Okinawa are vulnerable to the "dangers of a masculinist nationalism,"

in that they are victims of the Japanese mafia ( yakuza ) gangs that run the prostitution rings

that thrive in underground economies; they are also the potential victims of violence by

patrons, either U.S. military or Japanese tourist.

These women, as well as the older Okinawan women veterans of the business,

present the problem of image to a masculinist discourse of nationalism in which the

women (worthy) to be protected are (only) the women by which Okinawa would like

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

124 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

to be remembered and known: namely, the aforementioned Himeyuri student nurses,

patriotic daughters who were sacrificed by the Japanese imperialist state when they were

forced to tend Japanese soldiers on the front lines of a battle the soldiers had no chance

of winning. The 1995 rape of the schoolgirl by three American servicemen resuscitated

the image of the sacrificed daughter.

By employing the language of patriarchy in bringing attention to the 1995 rape

case- which on the surface suggested their alignment with the male leaders of the anti-

base movement in Okinawa- feminists appeared to defer their own agendas, for the

time being, in order to support the larger cause of national (Okinawan) unity. Hence the

image of chaste daughters deserving of protection was revived and deployed to criticize

the Japanese state for placing Okinawan girls and women in harm's way by hosting the

servicemen responsible for that particularly vicious crime- and for the many more

perpetrated against local women since 1945.

The image of chaste women who require the protection of a masculinist state,

however, is counteracted by the image of the prostitute, who by her very existence defies

that authority. She is a representation of women who, because of their position outside

the traditional family structure, embody a dangerous and threatening nonreproductive

sexuality -despite the fact that prostitutes do have children. The children of prostitutes are

rendered invisible, precisely because they cannot be sanctioned by the state when conceived

outside of marriage. In another sense, the existence of prostitutes represents the failure

of the state (father figure) to take care of its children. We might also argue that living a

life of prostitution implies a rejection of the state and all its attendant mores and social

rules- and thus a rejection at the symbolic level of the care of the national father.

Okinawa's prefectural leaders, who have promoted a tourist- and high-tech-friendly

economy as an alternative to the island's ongoing subsidization by Tokyo,14 envision

being in the midst of and riding the waves of new global flows. Yet prostitution itself

was one of the businesses that thrived as Okinawa embarked on its new economic route

in the early 1970s.15 Moreover, as the island prefecture continues to promote itself as a

hub of the global flow of culture and goods, this flow includes the trafficking of women's

bodies: prostitution may be one of the unspoken lures to doing business in Okinawa.

Although the tourist economy has created greater prosperity for Okinawans, the flip side

is that tourism has also drawn thousands of unskilled women from poor nearby countries

to enter the sex trade there.

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 125

Ethnographie Evidence: Women Working the Postwar Economy

When I arrived in Okinawa to carry out fieldwork about women's wartime experiences,

the example that locals always proffered when they heard about the subject of my study

was the Himeyuri. These primary symbols of Okinawan wartime victimization and

national virtue, the slain daughters of Okinawa, necessarily cannot speak. Furthermore,

their surviving classmates have made it their sacred duty to protect and nurture the

memory of their fallen comrades. I argue elsewhere that the surviving Himeyuri

are therefore curiously silent about contemporary politics.16 The museum built in

honor of the girls who were killed on the battlefield while nursing Japanese soldiers

is meant to remind viewers of the menace of war to the vast numbers of the innocent.

This generalized sentiment avoids the specificity required in critiques of the nationalist

state, whether wartime Japan or the U.S. The focus is squarely on the lost lives of

innocent civilians- female children, really.

By contrast, women who speak out critically about their experiences as citizens

(feminist activists) and/or who, through their sex work, clearly do not embody innocence

(prostitutes) have no comfortable or legitimate place in the patriarchal discourses of

nationalism. It is in this sense that both feminists and prostitutes in Okinawa occupy an

ambivalent position. Prostitutes are not only a problematic symbol of the failure of the

family (important in a nationalist agenda that sees the father as protector) but dangerous

precisely because they can exist outside the structure of the family. As a result, it is socially

acceptable to malign them as "bad" without engaging in the specificity of discourse that

is needed to understand them and their condition in human terms.

As independent thinkers, feminists, too, threaten the fabric of social institutions

that traditionally seek to rein in individual, and especially female, voices; conventionally, in

Okinawa, the family is represented by the father's name, if not voice. A fitting cultural

emblem of male/female relations on the island is the pair of shisa lions, usually ceramic

or clay, that adorns the entry to most domiciles: the he-lion bares his teeth in fierce

protectiveness of hearth and home, while the she-lion supports him in closed-mouth

silence, lion cub at her feet. Yet as outspoken critics of the 1995 rape, women activists

not only deplored the U.S. military presence in Okinawa but implicitly criticized the

failure of Okinawan males to effectively protect the family. Since men are supposed to be

the spokespersons for Okinawan political change, perhaps this is one reason women

protestors are not invited to the negotiating table. Outspoken women are a persistent

problem within a discourse of national unity. In the case of Okinawa, women must contend

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

126 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

not only with the legacy of Japanese patriarchy but with existing patriarchal institutions

within Okinawan society and those imposed by the masculinist hierarchical structure of

the U.S. military as well.

Although women are represented in Okinawan myth and lore as the holders of

the purse strings,17 this was a qualified position of power. In fact, wives were expected

to do the work of the family both within the walls of the home and beyond. Many of the

women with whom I spoke complained bitterly about having to do all the work while

men "drank and took it easy."18 Once again, these are generalizations that apply in some

but not all cases. There were certainly many women with whom I spoke whose husbands

also worked hard to make ends meet. During the occupation period, even children had

to help out. Noborikawa Nobuko, an informant from Misato Village, even today grows

a huge vegetable garden and raises chickens on her urban property. Her daughter Fusae

recounted how during the 1960s and 1970s her mother would send her out to sell eggs

in the nearby foreigner neighborhoods ( gaijin juutaku ) in the northern part of the city of

Koza (now Okinawa City).19 Due to the racially segregated nature of U.S. military

culture in the Vietnam era, the foreigner neighborhoods nearest Noborikawa's home were

populated by African American servicemen, many of whom lived on the local economy

with their Okinawa wives or lovers. The urban sprawl that surrounded Kadena Air Base

in north Koza was marked by the bar and entertainment district known as "The Bush," as

well as by a low-income covered shopping street, the Silver Mall, that was frequented by

African American troops. The higher-end shopping mall at the Goya intersection, outside

of Kadena Air Base's Gate II, was for solidly middle-class Okinawan consumers and

mostly Caucasian U.S. civilians and servicemen. Both of Koza's malls were run largely

by women, some of whom were the wives of men who also held jobs on the base. Many,

however, were single Okinawan women trying to support their biracial children by

owning or working as clerks in these mall stores.

"Okinawan Women"

As a result of having U.S. soldiers, sailors, and marines in their backyard for so long,

mainland Japanese have long stigmatized Okinawan women in general, and not just

women who married American servicemen. In this scenario it is assumed that, because

of Okinawa's relative economic poverty during the long occupation, island women

must have had no recourse but to fraternize with American GIs. This is, simultaneously,

a sympathetic view of Okinawan women who made personal sacrifices in order to

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 127

feed their families. This contradictory image does not distinguish between socio-

economic classes or home regions of the women, nor does it distinguish personality

and individual preference.

Since the mid-1980s, with the appeal of American servicemen to young, relatively

financially secure mainland Japanese women, the phenomena of the Amejo (literally,

"American [-loving] woman") and kokujo (literally, "Black[-loving] woman") have come

to dominate images of Okinawa. Resort Okinawa has become stereotyped as a play land

for these women. I refer to the case of the June 2001 rape in the Mihama New Town, in

which a young mainland Japanese woman working in the bars was raped by an African

American serviceman in the parking lot outside the bar where they had just met. The

woman was labeled in some media reports as an Amejo.20 Although Okinawans may

differentiate between their own daughters and young Japanese women visiting from the

mainland, U.S. servicemen interested in using the women for sexual pleasure make no

such distinction. As part of the mentality of military occupation, all (Asian) women are

fair game, prey to the rapacious desires of foreign soldiers. In this scenario, it matters

little whether women are Okinawan, mainland Japanese, or Filipina.

In any case, women who become involved with U.S. servicemen become suspect

as "bad" women, as the media coverage of the 2001 rape revealed. They are viewed

as promiscuous and licentious because they do not choose the conventional route of

marrying local men or of "behaving" themselves by returning home at a respectable hour

and avoiding the bars frequented by soldiers. Also disturbing to traditionalists is the fact

that such women opt out of their perceived responsibility to marry before the age of 30 and

produce 1 .3 to 2 children. The model of gender relations that made Japan economically

successful is no longer salient in an age when women are better educated, able to earn

their own livings, and therefore likely to expect and desire more from life than choosing

the conventional route of being housewives.21 Although Japanese women continue

to be pressured to play domestic roles in support of wage-earning sarariiman (literally,

"salaried man") husbands, the rewards are dubious and many women choose to opt out,

sometimes by trying out new lives in places like Okinawa.

Okinawa as Dangerous Feminized Space

Okinawan women are glossed through the images of Okinawa as comprising a dangerous

feminized space. Okinawa's lack of political autonomy - through its colonial domina-

tion by Japan and postwar occupation by the U.S. military- and its peaceful past as a

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

128 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

country that did not bear arms further situate it as josei bunka (feminized space/culture).

Okinawa is also stereotyped as physically beautiful, culturally "exotic," and as a warm,

welcoming, "laid back island culture" that is financially dependent, politically turbulent,

and potentially (and titillatingly) dangerous because of the presence of foreign military

bases. Provocative, alluring, and sensual, Okinawa is a tourist destination that offers an

undercurrent of mystery and danger.

While there may be similarities between the symbolic positions of feminist

activists and prostitutes in Okinawa, socio-economic class places them in fundamentally

different roles. Most women who have had to resort to prostitution for a living have not

had access to other kinds of work, often due to a lack of the family support that is crucial

to the survival of women in a society that puts the family before the individual. Many

women from rural parts of Okinawa did not complete even a basic education, let alone

have access to higher education, particularly during the occupation era (1945-72).22 In

contrast, feminist leaders in Okinawa are educated, many of them having gone to college

and graduate school.

The women who ended up in prostitution did so out of economic necessity, lacking

education and/or other means to avoid such stigmatizing and often dangerous work.

Those women with whom I spoke who ran brothels or hostess clubs also did so out of

economic need; it was not a profession about which any of them spoke with pride. One

woman I interviewed never admitted to me that she had been the proprietor of a brothel

(I learned this later from the city official who put me in touch with her); instead, she

told me she had a restaurant on Business Center Street, the bustling center of a service

economy outside Kadena Air Base catering to the various appetites of U.S. servicemen.

Her earnings allowed her to send four daughters to junior college to become skilled

workers, a nurse and a teacher among them, thereby ensuring their escape from the

unseemly life their mother had endured- and it was clear that a particular interpretation

of family history was already being imagined and disseminated along more socially

acceptable lines.23 However, another woman told me that she preferred the excitement

and financial benefits of working in the clubs during the Vietnam years over being a

nurse's assistant in a dingy hospital- boring work that paid little, she said.24

This brings me back to the question of women's agency. Feminist activists, visible

in the support of Okinawan anti-base and anti-war politics from before the time of

reversion (1972), have signaled Okinawan women's strength and agency. In addition,

ever since 1945 various groups of women activists who do not consider themselves

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 129

feminists -including housewives' association leaders, educators, and churchwomen- have

been in the forefront of efforts to improve living conditions for poor families and to

protect their own neighborhoods from the spillover of bar and brothel activities. The

difference between women civic leaders in the early years of the occupation and the

feminists who now hold both elected and other official positions at all levels of government

is that the earlier women leaders filled the more traditional role of being the keepers of

civic virtue. They often campaigned against prostitution before it was made illegal in

Okinawa.25 Today's feminists, in contrast, may argue against the institution of prosti-

tution, but they also understand the socio-economic conditions that push women into

such undesirable work. Consequently, they make efforts to reach out and help women

change their own lives, attempting to mitigate the effects of long-standing discrimination

against women in the sex trade. To this end, they provide counseling, shelters, and,

more recently, a rape crisis center to all women.

It was at the insistence of vocal feminists after the 1995 rape of the schoolgirl that

the crime was publicized to the world media. As mentioned earlier, Naha City Council-

woman Takazato Suzuyo became a recognized spokesperson for women on Okinawa,

appearing on CNN and other broadcasts to represent the outrage that Okinawans felt.

Other local officials- such as Miyagi Harumi of the Naha City Women's Section; Itokazu

Keiko of the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly, and now of the National Assembly; other

women in charge of the Women's Sections of city and town offices throughout Okinawa;

and church and civic leaders- held massive demonstrations of protest against the bases.

Feminist leaders played a critical role in helping to stage the huge Ginowan City protest

of October 1995, when 85,000 people gathered to demand a change in the U.S.-Japan

Security Alliance (AMPO). There is no question that feminists have long been outspoken

critics of social conditions in base-occupied Okinawa.26

Victims or Agents?

Is it wrong for us to assume that because economically deprived women often had no

choice but to go into prostitution, they were or are simply victims of the social, economic,

and political conditions of occupation-era and post-reversion Okinawa? As already

mentioned, one of my informants insisted that she had chosen the life of a bar hostess (the

euphemism she used for her work as a prostitute) over life as a nurse's assistant, which

she felt would have been too confining. To be sure, her choices were severely limited in

late 1950s and 1960s Koza, the large central Okinawan city outside of Kadena Air Base

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

130 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

that prospered until the 1980s on a base-dependent economy. As such, the question of

agency or victimization is muddled when we consider the enormous structural influence

of U.S. military bases as the main source of employment for Okinawans before 1972.

Ultimately, however, we could argue that the exchange value of sex for survival was the

basic, unspoken capital that circulated in the occupation-era economy, keeping families

from starvation. And just as Kim and Choi note that the discourse of "the violation of

national virgins"- the so-called comfort women- "mobilizes the Korean sense of shame,

which in turn serves to unify the nation,"27 so the discourse of the Okinawan daughter,

sister, or mother forced into prostitution mobilizes the Okinawan sense of shame and

anger, thus unifying Okinawans against their foreign occupiers.

The reality of their lives, however, is that prostitutes are neither accorded true

agency nor accepted for the work they are forced into doing, except perhaps within the

embrace of feminist activists' transnational agendas. Since it appears that the "choice"

to work in the sex trade is a function of having few if any other options, at least some

degree of victimization is involved. But there is no real place for these women within the

discourse of Okinawan identity politics, which otherwise prides itself on being all-inclu-

sive. Prostitution is, simultaneously, a dangerous threat to the mainstay of the modern

Japanese nation, the family.

Recent comments by a female Japanese cabinet member and by the commander

of U.S. forces in the Pacific both reveal the prevailing lack of respect for Okinawan

women- not to mention the speakers' lack of understanding of what it is like to live in

the shadow of U.S. military bases. The two comments also reveal the usual low regard for

women who associate with U.S. servicemen, even as they continue to affirm the political

necessity of having foreign troops stationed on the island. Ultimately, such comments are

signs of the predominance of a worldview in which the privileging of patriarchal values

is the normative order: in this case, women of so-called questionable morals are held to

a standard not applied to the men involved. These women are, in effect, accorded little

respect as human beings. Thus Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs Tanaka Makiko

actually commented after the June 2001 rape of the Japanese woman in Mihama that

the victim was likely at fault because she was drunk at 2 a.m. at an Okinawan bar where

women go to meet American servicemen.28 No mention was made of the morals of the

American serviceman who raped the woman.29 Ironically, Minister Tanaka herself was

soon a victim of the very patriarchal system that had engendered her criticism of the raped

woman, when she was fired by Koizumi for what he and other (conservative) male LDP

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 131

leaders deemed to be excessively outspoken and out-of-control behavior. Yet Tanaka's

direct, no-nonsense style might have been acceptable had she been a man.

Sadly, Tanaka's comments about the 2001 rape victim reveal her own acceptance

of a masculinist worldview in which women are held to a higher and different set of moral

values than men are. This was certainly reflected in the comments of the commander of

American forces in the Pacific, Admiral Richard C. Macke, after the 1995 schoolgirl's

rape by three servicemen under his command. He stated publicly that for the price of a

rental car, they "could have had a girl [meaning prostitute]."30

Both comments unmask widely held contempt for prostitutes, and for what is

deemed prostitute-like behavior in Okinawan women. But I also wonder if they are

in fact thinly veiled allusions to, or revelations about, a more general attitude toward

Okinawan women as a whole by Japanese mainlanders and U.S. military overlords in

Okinawa. (As already mentioned, the fact that the 2001 rape victim was Japanese rather than

Okinawan became irrelevant once she was at a bar frequented by U.S. servicemen, and the

Okinawan schoolgirl's tender age in 1995 did nothing to protect her from being treated as

fair game.) This raises other questions about the continued marginalization of Okinawa

and Okinawan political practices by both of these First World powers, often expressed by

positioning Okinawa (the sexual imagery of control and submission is intentional here) as

a feminized and/or emasculated entity- namely, as being the site of the aforementioned

josei bunka (women's culture). Mere lip service is paid to the demands of Okinawans to

(1) redress wrongs inflicted on their communities, and (2) remove the U.S. bases, which

is now even less likely to happen than before, given U.S. political concerns over China's

growing military power and the threat of North Korea in the immediate vicinity, as well

as the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The continued presence of more than 50,000 U.S. military personnel and their

dependents in the island prefecture- with everything from payment of Okinawan

base-worker salaries to land and housing rents and the construction of recreation

centers taken over or heavily subsidized by the Japanese government- indicates the

true condition of disregard for Okinawa's position. These are all signs that Okinawa

continues to be the pawn of both the U.S. and Japan, confirming even today the

unfortunately still-cogent insight, expressed in 1958 by Berkeley historian George

Kerr, that this is the sad fate of a minor kingdom strategically located between major

powers.31 Recently declassified documents from the reversion era contain 1969

and 1970 statements by U.S. State Department policy makers and military decision

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

132 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

makers that clearly indicate their intention to do whatever was minimally necessary to

placate Okinawans' demands for a return to Japanese sovereignty, yet in a way that would

make the U.S. look as though it supported granting Okinawans a degree of political self-

determination.

As Kim and Choi remind us, the troping of political relations between nations in

sexualized terms is not new. Benedict Anderson's now classic study of nations as imagined

communities is significant for its anthropological orientation, suggesting that nationalism

ought to be thought of "as if it belonged more with 'kinship' or 'religion,' rather than

with [ideologies such as] 'liberalism' or 'fascism.'"32 In Nationalisms and Sexualities,

Andrew Parker and his colleagues note that "nearly every aspect of Anderson's account

of the nation raises issues of gender and sexuality," then go on to say that

Though undeveloped in his analysis, Anderson's comparison enables the crucial

recognition that- like gender- nationality is a relational term whose identity derives

from its inherence in a system of differences. In the same way that 'man' and 'woman'

define themselves reciprocally (though never symmetrically), national identity is

determined not on the basis of its own intrinsic properties but as a function of what

it (presumably) is not. Implying "some element of alterity for its definition," a nation

is ineluctably "shaped by what it opposes." But the very fact that such identities

depend constitutively on difference means that nations are forever haunted by their

various definitional others.33

In the postwar geopolitical scenario, in which Okinawa has been situated within a

masculinist political narrative, the U.S. is troped in the role of alpha male to a complicit,

docile younger brother, Japan, in need of U.S. military protection. Okinawa as pawn is

left completely emasculated, a feminized non-threat.

Sympathizers with the Okinawans' plight often cite their history as the non-arms-

bearing people of a pacifist independent kingdom before colonization ( 1 609), annexation

by the Japanese (1872), and prefectural status beginning in 1879. Indeed, as a result of

banning the use of private arms in the fifteenth century, the argument goes, Okinawans

could not defend themselves against the overlords of Satsuma in the early seventeenth

century, when the loss of Okinawa's true political autonomy began.34 This is a reading of

Okinawan history from within the paradigm of imperialism, in which Okinawa can only be

viewed as a weak and vulnerable entity unable to maintain its political independence.

Yet from the perspective of some Okinawans, this paradigm is incorrect. Critics

such as economist Koji Taira would argue that reading Okinawa's political location in

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 133

terms of an emasculation of identity is simply the imposition of a Western imperialist

paradigm in which the Machiavellian "Might makes right" philosophy prevails. And the

logic is unfortunately extended to trope the might of a nation in terms of sexual prowess

and power. As Parker and his colleagues point out,

Whenever the power of the nation is invoked - whether it be in the media, in scholarly

texts, or in everyday conversation- we are more likely than not to find it couched

as a love of the country, an eroticized nationalism.35

They go on to say that there is no privileged narrative of the nation.36 But Okinawans who

take issue with the conventional Western paradigm, in which Okinawa is symbolized as the

emasculated "other" to the powerful First World entities of the U.S. and Japan, question

the authority of this model. Hence we must pay attention to the particular and complex

instances of divergence from and resistance to "powerfully homogenizing versions of the

nation that constrain, oppress, . . . eviscerate," and emasculate.37

The Feminist Conundrum, Okinawa Style

Within the conflict over Okinawa's political autonomy, some prominent NGOs in the anti-

base movement have been composed of feminists and other women activists, contributing,

as Vincent Pollard has argued, to global civil society alternatives to traditional political

structures.38 While they have generally supported the policies of former Governor

Masahide Ota (1990-98), however, activist women- particularly feminists- have found

themselves in a conundrum. Although they support the idea of an economically more

independent Okinawa, they also question what the position of women will be within an

emerging economy that is increasingly centered on tourism.

As during the days of the U.S. occupation, a tourist-dependent Okinawa would

retain a service economy. In fact, resource-poor Okinawa's trade deficit is already more

than made up for by tourism, which is considered an export industry. Tourism generates

440 billion yen a year, more than 14 times the amount it did in 1972, and accounts for 1 7

percent of all of Okinawa's outside income (or 1 1 percent of GDP). Ninety-seven percent

of Okinawa's 4.127 million visitors in 1998 came from mainland Japan.39 These figures

have changed only slightly in the last decade, according to a JETRO (Japan External Trade

Organization) website.40 Yet unemployment in Okinawa is twice the national average,

and as young people leave the peripheries of the prefecture to come to the central cities

of Okinawa, jobs remain scarce, especially for the young.

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

134 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

Where does this leave women? Feminists argue that this often leaves women on

the bottom of the service work pile. Yet we must be wary of making generalizations

about the lives of Okinawan women. All across the socio-economic spectrum, situations

for women vary according to household economic need, existing resources (labor and

financial), social beliefs and ideologies about work and gender, and individual personalities

and relationships between men and women. Many wives work outside the home, but

often to supplement the main income brought in by the husband/father/eldest son; or

women engage in civic duties that may or may not be remunerated. In any case, women

are still perceived to be the primary caretakers of the home, responsible for the care

and education of children.41

Feminists and other women activists have generally come from the educated elite

households. Longtime social activists who do not identify with the feminist movement

include Uezu Toshi, an educator from a prestigious aristocratic family from Kume Island

and longtime leader of the Okinawa Women's Association, and Asato Toshie, a retired

kindergarten teacher who served for twenty years in the Kitanakagusuku Village Assembly.

Uezu and Asato, young mothers during the Second World War, were part of the educated

elite who had careers as teachers and civic leaders after the war. Other women generally

occupied the more traditional roles of serving home and community as mothers and

housewives. Today's generation of feminist leaders may or may not be homemakers and

mothers, and they occupy prominent elected or appointed posts in various sections of the

prefectural government. However, despite the fact that feminists have been a critical part

of the anti-base protest movement in Okinawa, their agendas to put in place (or remove)

structures for the safety and welfare of women are generally accorded secondary status,

after the more pressing matter of establishing larger Okinawan political goals of base

removals and a stronger economy.

Okinawans embrace their identity as a peace-loving people, in conscious opposition

to what they see as a once militarily aggressive and now economically aggressive Japan.

Some Okinawans thus accept the depiction of their culture as a feminized one (josei

bunka ), precisely because they favor positing themselves against a Yamato (mainland

Japanese) masculinist-warrior culture. In arguing for a political paradigm that is not

confined by traditional nation-state forms, Okinawan leaders look to the global city as

a transnational entity that can take advantage of the increasing permeability of national

borders in terms of economics, technological developments, and social fluidity. Ironically,

feminists- who want to work through existing differences to help create a new, more

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 135

tolerant and egalitarian order on a global scale- seem still to be marginalized in these

discourses of a radically new political order. As R. Radhakrishnan asks,

Why is it, then, that the advent of the politics of nationalism signals the subordination

if not the demise of women's politics? Why does the politics of the "one" typically

overwhelm the politics of the "other"? Why could the two not be coordinated within

an equal and dialogic relationship of mutual accountability? What factors constitute

the normative criteria by which a question or issue is deemed "political"? Why is

it that nationalism achieves the ideological effect of an inclusive and putatively

macropolitical discourse, whereas the women's question- unable to achieve its

own autonomous macropolitical identity- remains ghettoized within its specific

and regional space?42

Attention to and criticism of overarching transhistorical or supranational claims have been

applied to feminism. But in fact Okinawan women, like feminists elsewhere, are rethinking

community in historically specific, local terms while also linking up with women in

Asia as well as in Europe. Women seemed to fare better under Ota's governorship than

under that of Inamine, the LDP candidate who followed him; and it remains to be seen

how women will fare today, under the leadership of Nakaima Hirokazu. As a former vice

governor under Ota and outspoken proponent of the removal of U.S. bases, Nakaima is

likely to prove more like Ota than Inamine. But Okinawa may nevertheless continue

to experience the effects of traditional patriarchal hierarchies that mark social order

and practice- and that explain, at least in part, why women today still have difficulty

accessing official positions. There were also complaints by women activists during

Ota's tenure that despite women's apparent access to power and instruments of change,

in fact they still experienced many obstacles and restrictions. For example, although the

prefectural government publicly lauded the creation of the REICO rape crisis center, its

financial contribution to getting it started was surprisingly meager.

Also, although women were appointed as part of two delegations to Washington,

D.C., after the 1995 rape of the schoolgirl, they found that they were not taken seriously

and felt a less-than-genuine concern for women's issues by male members of the Ota

delegation- whose primary aim was, after all, to get U.S. lawmakers to hear them out

about base removals. Parker and his colleagues recognize this problem in their comment

that "one of the gains of academic feminism has been its hard-won recognition that gender

relations cannot be 'understood in stable and abiding terms' either within or between the

borders of nations, and that while patriarchy may be universal, its specific structures and

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

136 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

embodied effects are certainly not."43 They also look at the relationship between nationalism

and women's political movements:

Historically, female solidarity emerged in the West after the first waves of nation-

alist fervor receded; working for such issues as suffrage, welfare and reproductive

rights, women's movements challenged the inequalities concealed in the vision of

a "common" nationhood. In anti-colonial struggles, on the other, feminist programs

have been sacrificed to the cause of national liberation and, in the aftermath of

independence, women have been relegated to their formerly "domestic" roles.44

In fact, women in Okinawa may enjoy more autonomy and involvement in elected and official

positions than those in mainland Japan- in part because of Okinawa's pre-colonial tradition

of women religious leaders, as well as its longer exposure to U.S. educational philosophies

during twenty-seven years of occupation (1945-72). But it is also due to the postwar history

of women's reform movements and the anti-base (read anti-colonial) struggles to which

women were necessary for success. We could also argue that the presence of unwanted U.S.

bases for over sixty years has been the defining issue that encouraged women to be more

vocal and men to be more inclusive of women in protest movements.

Still, the problem is, precisely, women's vocality. As Carol Delaney and others have

argued, the nation has long been troped as woman, with the body politic often depicted

as female and the national soil represented by the body of the mother that requires the

protection of male members of the nation. Furthermore, "this trope of the nation-as- woman . . .

depends for its representational efficacy on a particular image of woman as chaste, dutiful,

daughterly or maternal."45 It is for this reason, as I argued above, that certain Okinawan

women are not allowed into the roster of sacrificed daughters- namely, because they fail

the chastity/motherliness test. Curiously, both Okinawan prostitutes and feminists fall

into this disallowed category. As Delaney quotes Anne McClintock,

"No nationalism in the world has ever granted women and men the same privileged

access to the resources of the nation-state." Their claims to nationhood frequently

dependent upon marriage to the male citizen, women have been "subsumed only

symbolically into the national body politic," representing in this process "the limits

of national difference between men."46

The "deep, horizontal comradeship" of which Ben Anderson speaks, and which marks

national community, is ultimately a fraternity, as he tells us- a community of men.

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Linda Isako Angst 137

I argue, then, that the trope of the nation as a woman only works when women

remain silent, symbolizing the nation but never representing it. Loudmouth feminists and

unchaste prostitutes are excluded from this patriarchal ordering. The ideal female models

for symbolizing the nation are valorized for their reproductive capacity, their potential

for motherhood. Feminists, often equated with a masculinized femininity, are troped as

lesbians, or at best as some hybrid image of a power woman- both mother figure and

latent lesbian. It is in this way that the heterosexual family became the norm that played

a central role in the nation's public imaginings about itself, so that motherhood could

be viewed as national service. Other kinds of (nonreproductive) female sexuality were

not considered legitimate by the standards of the state. Prostitutes' reproductivity, when

they gave birth, was a tainted form of productivity for the nation, and their children were

therefore "illegitimate."

In Okinawa, ironically, women who went into prostitution during the occupation

years were often the primary breadwinners for the family, although they continued to

be stigmatized socially. Yet even as they continue, today, to be labeled "bad girls," they

act, as Laura Miller has stated, strategically and autonomously.47 Gayatri Spivak warns

us against thinking that the story of the prostitute is "an evolutionary lament that their

problems are not yet accessible to our solutions and they must simply come through

into nationalism in order then to debate" their sexual status/preference.48 Among the

prostitutes in Okinawa with whom I spoke, there is an acceptance of living in a kind of

parallel universe, where they realize their exclusion from the moral realm of Okinawan

national identity despite the inclusive rhetoric of the anti-base movement- which unifies

all Okinawans against the threat of a foreign military occupation force, and to which all

other issues are subsumed.

However, even if the goal of base closures is achieved, prostitutes and feminists

alike may find that their hoped-for transformation in social values does not occur, and

hence that they are still excluded from a traditional nationalist narrative. Neither group

has been invited to be a full participant in the nationalist project (because their actions

preclude acceptability into established norms of behavior and belief), and both groups

embody an intrinsic threat to and rejection of that modernist (and patriarchal) project.

Thus they must continue to act outside of acceptable modes of being/action. As such,

feminists and prostitutes continue to occupy a dangerously liminal zone that ultimately

relegates them to the category of Okinawa's "bad girls."

This content downloaded from

79.155.105.15 on Wed, 15 Nov 2023 18:38:40 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

138 U.S.-Japan Women's Journal No. 36, 2009

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Kazumi Heshiki, who kindly agreed to translate the title into Japanese.

Notes