Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children

Uploaded by

iman el haddouchiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children

Uploaded by

iman el haddouchiCopyright:

Available Formats

568156

research-article2015

PSSXXX10.1177/0956797614568156Olson et al.Gender Cognition in Transgender Children

Psychological Science OnlineFirst, published on March 5, 2015 as doi:10.1177/0956797614568156

Research Article

Psychological Science

1–8

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children © The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0956797614568156

pss.sagepub.com

Kristina R. Olson1, Aidan C. Key2, and Nicholas R. Eaton3

1

Department of Psychology, University of Washington; 2Gender Diversity, Seattle, WA; and 3Department

of Psychology, Stony Brook University

Abstract

A visible and growing cohort of transgender children in North America live according to their expressed gender

rather than their natal sex, yet scientific research has largely ignored this population. In the current study, we adopted

methodological advances from social-cognition research to investigate whether 5- to 12-year-old prepubescent

transgender children (N = 32), who were presenting themselves according to their gender identity in everyday life,

showed patterns of gender cognition more consistent with their expressed gender or their natal sex, or instead

appeared to be confused about their gender identity. Using implicit and explicit measures, we found that transgender

children showed a clear pattern: They viewed themselves in terms of their expressed gender and showed preferences

for their expressed gender, with response patterns mirroring those of two cisgender (nontransgender) control groups.

These results provide evidence that, early in development, transgender youth are statistically indistinguishable from

cisgender children of the same gender identity.

Keywords

transgender children, implicit cognition, gender development, social cognition

Received 7/21/14; Revision accepted 12/20/14

Transgender children are receiving increasing attention saying they are the “opposite”2 gender, much as they

in the national media and, as a result, are the focus of might say on any given day that they are a dinosaur or

considerable public debate. For instance, a court recently princess (Walsh, 2014).

ruled that 6-year-old Coy Mathis had the right to use the What scientific evidence exists one way or another on

girl’s restroom in her Colorado school, although she had the topic of transgender identities in childhood? The

been assigned male identity at birth1 (Payne, 2013). The majority of evidence that children are (or are not) trans-

story of Ryland Whittington, a transgender child who was gender comes from what the children themselves report.

assigned female identity at birth but who socially transi- Decades of research with gender-nonconforming chil-

tioned to living as a boy early in childhood, became a dren, including those who experience gender dysphoria

viral sensation on YouTube (The Whittington Family, (historically gender identity disorder), have suggested that

2014). After months of heated debate, the Minnesota these children are much more likely than other children

State High School League voted to allow transgender to say that they are the “opposite” gender from their natal

children to play on the sports teams of other children sex (e.g., Zucker et al., 1999). However, these data are

who share their gender identity (rather than their natal open to precisely the concerns raised above—any chil-

sex; Raddatz, 2014). Responses to these and other cases dren who are confused, delayed in understanding gender,

involving transgender children have varied, but a promi- or just engaging in imaginative play could say that they

nent theme has been skepticism. This skepticism takes are the opposite gender, much as children might claim to

many forms: concerns that these children are “confused”

and that they therefore need therapy (McHugh, 2014),

Corresponding Author:

that these children are “delay[ed]” in their understanding Kristina R. Olson, University of Washington, Department of

of gender in part because of the behavior of their parents Psychology, P. O. Box 351525, Guthrie Hall, Seattle, WA 98195

(Zucker et al., 1999), or that these children are merely E-mail: krolson@uw.edu

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

2 Olson et al.

be a cartoon character or superhero. For this reason, self- We reasoned that if children are confused by the par-

report measures, while useful in some ways, can be prob- ticular questions posed to them (i.e., as a result of gen-

lematic in evaluating these types of concerns. eral confusion or a gender “delay”; Zucker et al., 1999), if

The current study aimed to inform the discussion of they are merely self-reporting the “wrong” gender iden-

gender cognition in transgender children by supplement- tity (Walsh, 2014) much as one might report being

ing self-reports with a methodology less open to these Superman on Halloween, or even if they are just opposi-

types of response-bias concerns: implicit measures, such tionally reacting to the question of their gender identity—

as the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, in all cases by stating they are a different gender from

& Schwartz, 1998). Implicit measures are harder to control their natal sex—these children should show one of two

and are less susceptible to modification than explicit self- patterns of confusion. First, they could be truly confused,

report measures (which can be changed on command; as indicated by random responding and no systematic

e.g., Gregg, Seibt, & Banaji, 2006; McDaniel, Beier, Perkins, response across measures and participants. Alternatively,

Goggin, & Frankel, 2009), have been widely used with they could implicitly identify as their natal sex (because

child participants (e.g., Rutland, Cameron, Milne, & they actually understand gender and are merely self-

McGeorge, 2005), correlate with behavior (Greenwald, reporting this “incorrect” gender).

Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, 2009), and can be used to In contrast, if these children are not confused, delayed,

assess multiple aspects of cognition, including, for the or pretending, and in fact their expressed gender repre-

present purposes, both identity and preferences (e.g., sents their true identity, we would expect them to respond

Greenwald et al., 2002). Thus, in the current study, we similarly to gender-matched control participants not only

assessed a group of transgender children’s responses on on self-report measures, but also on implicit ones. Thus,

implicit measures of gender cognition in addition to while the IAT should not be seen as a lie detector test,

explicit self-reports. nor as the final say in determining a child’s gender, it can

Our primary sample comprised children who present fill in some of the gaps left by the extant literature

themselves in terms of and appear to other people to be because it is not open to the same types of criticism as

their gender identity (not their natal sex) in all aspects of explicit self-report measures. Used in tandem, implicit

their lives. Aside from helping to address the central and explicit measures can be highly informative about

research questions, this population of expressly transgen- the gender cognition of transgender children, and the

der children was important to study for two other rea- current study is the first to take such an approach. We

sons. First, this group is increasingly prominent and likely focused specifically on 5- to 12-year-olds, whom previ-

growing in size in North America as more transgender ous literature suggests are old enough to complete

children are raised in supportive environments (Spack implicit measures (Dunham, Baron, & Banaji, 2007) yet

et al., 2012); however, studies using this group are entirely because of their prepubescence are subject to more sci-

absent from the psychological literature. Second, these entific debate than older transgender individuals about

children can be thought of as a more “pure” expression the persistence of their transgender identities (Byne et al.,

of the transgender experience than transgender children 2012).

who do not present themselves according to their gender

identity. The conflict the children in our sample experi-

ence is tension between their natal sex and their gender Method

identity—the core of the lived transgender experience.

Such a sample is more informative than one comprising

Participants

transgender children who do not outwardly live in terms Thirty-two prepubertal transgender children (12 natal

of their gender identity, because these children’s females/transgender boys, 20 natal males/transgender

responses would reflect a conflict between their inner girls; mean age = 9 years, 1 month, SD = 25 months,

view of themselves and other people’s views or society’s range = 5–12 years; 23 White, 2 Asian, 1 White/Asian

expectations of them, in addition to the central tension biracial, 1 Black/White biracial, 3 White/Hispanic bira-

between their gender identity and natal sex. As such, our cial, 1 Black, 1 Pacific Islander) were recruited through

sample allowed us to reduce potential confounding fac- online and in-person support groups for families with

tors (e.g., incongruence between self-perception and gender-nonconforming children as well as through con-

perception by other people) and arrive at clearer conclu- ferences for gender-nonconforming children and by

sions about childhood transgender identities in their full word of mouth. To be included in the current study, chil-

expression. We compared these children with two con- dren had to be 5 to 12 years old and live in all contexts

trol groups: cisgender (nontransgender) children matched as the gender expression “opposite” of their natal sex.

by gender identity and our transgender participants’ own These requirements resulted in the exclusion of 4 addi-

cisgender siblings. tional gender-nonconforming participants.

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children 3

Cisgender siblings of transgender participants were gender-preference IAT, the categories were “male,”

recruited when available and in the study’s age range. “female,” “good,” and “bad.” One response key in the

This resulted in the inclusion of 18 siblings (12 males, 6 IAT was used to classify stimuli from two categories (one

females; 13 White, 1 Hispanic, 1 Black, 1 Black/White target item, such as “male,” and one valence item, such

biracial, 2 White/Hispanic biracial) who were on average as “good”), and the other response key was used to clas-

approximately 3 months older than their transgender sib- sify stimuli from the remaining target and valence catego-

lings (mean age = 9 years, 4 months, SD = 26 months, ries (e.g., “female” and “bad”).

range = 5–12 years). Stimuli for the categories “male” and “female” were

Thirty-two control participants (20 female, 12 male; pictures of four male and four female children. An addi-

mean age = 9 years, 1 month, SD = 25 months, range = tional two photographs (one male, one female) were

5–12 years; 27 White, 1 Asian, 1 Black/White multiracial, used as category labels. Pictures were used so that read-

2 Asian/White biracial, 1 White/Native American/Alaska ing was not necessary. Stimuli for the attributes of “good”

Native multiracial) matched to the transgender partici- and “bad” were taken from Newheiser and Olson (2012).

pants were recruited through the first author’s research The “good” stimuli consisted of a present, puppies, an ice

lab from a database of families interested in participating cream cone, and flowers; the “bad” stimuli were a snake,

in developmental psychology research studies. They a spider, a car accident, and a fire. The labels for these

were required to have no significant history of gender attributes were represented by a smiley face (good) and

nonconformity. Each control participant was matched to a frowny face (bad). Scoring followed the Newheiser and

a transgender participant by age (within 4 months of age Olson (2012) algorithm, which is based on the general

at time of test) and was selected as the “opposite” natal IAT scoring algorithm (Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji,

sex of the transgender participants (to match for 2003) with a modification for the shorter length of the

expressed gender in daily life). Matched control partici- current test. This scoring involves the computation of an

pants also did not differ from transgender participants in effect size, D, in which a score of 0 indicated that partici-

performance on the fourth edition of the Peabody Picture pants were just as quick to associate “male” with “good”

Vocabulary Test (PPVT-IV; Dunn & Dunn, 2007; a proxy and “female” with “bad” as they were to associate “male”

for verbal IQ), t(27) = 1.13, p = .268, d = 0.21, or in terms with “bad” and “female” with “good.” Positive scores

of parental income, t(31) = 1.05, p = .304, d = 0.19. meant that control participants were faster to associate

We initially set a criterion of running participants until their natal sex with “good” and the “other” sex with “bad,”

at least 15 transgender children (who were living in terms while negative scores meant the opposite. Transgender

of their expressed identity in all aspects of their life) were participants were coded both ways in the analyses—once

recruited. At the location where the 15th participant was with positive scores indicating an association between

recruited, additional children were interested in partici- their expressed gender and “good,” and once with posi-

pating, so we ran all available children at that site, which tive scores indicating an association between their natal

resulted in an N of 19. The manuscript was reviewed for sex and “good” (the conversion involved merely multi-

publication in Psychological Science at that time. During plying one coding scheme by −1 to get the other).

the review process, 13 additional transgender children

(and their siblings and control participants) were run Gender-identity IAT. Participants’ implicit gender iden-

and, after consultation with the associate editor who tity was assessed with a second IAT that was similar to

reviewed the article, we decided to add them to the cur- the gender-preference version, except that the categories

rent report. No substantive changes resulted from the “me” and “not me” replaced “good” and “bad.” The stim-

addition of these participants, but all estimates became uli for the “me” category were “I,” “mine,” “me,” and

more precise. “myself,” whereas the stimuli for the “not me” category

were “they,” “them,” “theirs,” and “other.” Scoring was sim-

ilar, with 0 meaning participants were just as quick to

Measures associate “me” with “male” and “not me” with “female” as

Gender-preference IAT. We assessed participants’ they were to associate “me” with “female” and “not me”

implicit gender preferences with a half-length IAT (mod- with “male.” Positive scores meant control participants

eled after those used by Newheiser & Olson, 2012). This were faster to associate their sex with “me” and the other

length was feasible for use with all but the youngest chil- sex with “not me,” while scores for transgender partici-

dren in this study and was short enough to allow partici- pants were coded both ways (according to expressed

pants to complete the other measures without losing gender and according to natal sex) for comparison. This

their attention. In the IAT, participants must classify stim- task required some very basic reading skills and there-

uli from four categories using two response keys. For the fore was not used with the very youngest children.

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

4 Olson et al.

Explicit gender peer preferences. To assess explicit gender-identity IAT (all 5- to 6-year-olds). Two transgen-

gender peer preferences, we asked participants, in each der participants, 3 control participants, and 5 siblings did

of eight trials, which of two people they would prefer to not complete the PPVT-IV because they were too young

be friends with. On six of these eight trials (the only ones and did not have the attention span to complete all mea-

analyzed), the pair involved one boy and one girl, sures (the PPVT-IV was the longest measure), the family

matched for approximate age and attractiveness. The needed to leave the testing session early (the PPVT-IV

other two trials were fillers—one with a pair of boys and was typically administered last), or the PPVT-IV materials

one with a pair of girls. The appearance of each target were not available at the time of testing. Two transgender

child on the left versus the right of the screen was coun- participants chose not to complete the explicit peer or

terbalanced; half of the critical trials for all participants objects measures at all, 1 transgender participant and 1

had a boy on the left, and half had a boy on the right. For sibling did not complete all peer-preference items, and 1

control participants, responses were coded in terms of control participant and 1 sibling did not complete all

the number of times out of six that children selected the object-preference items. One transgender participant’s

peer who matched their own sex, and 3 was subtracted parents requested that the participant not be asked the

from this total so that 0 indicated no preference for males explicit gender-identity question. These participants were

or females. Positive scores indicated a preference for dropped on those particular measures but were included

one’s own sex, and negative scores indicated a prefer- for all other measures, hence the sample-size differences

ence for the other sex. For transgender participants, across analyses. Two siblings were dropped completely

responses were coded once in terms of the number of because they completed no IAT and PPVT-IV measures

times they selected the same-gender peers and then and, in one case, did not complete one of the explicit

reverse-scored for a same-sex score. measures—which made their participation of no added

value. All other participants completed all measures.

Explicit object preferences. Participants’ explicit prefer- Some participants completed additional measures for

ences for objects were measured across six trials on which the purposes of a pilot study. Although such measures

they were shown pairs of photographs of children and would typically be done with another group of partici-

told that each one had a preferred toy or food. The names pants, access to this sample is very limited, so all partici-

of these items were in fact novel words (e.g., “This is pants were run in the primary measures, and other

Amanda and she likes to play flerp. This is Andrew and he measures were sometimes run as pilot measures on the

likes to play babber.”). Our interest here was whether chil- same participants. From the beginning of the study, how-

dren would use the gender of the person endorsing the ever, the measures reported here were identified as those

item to inform their own preferences (this task was based of central interest and therefore were given highest prior-

on one devised by Shutts, Banaji, & Spelke, 2010). Chil- ity when we had limits on children’s time (e.g., when we

dren were subsequently asked, for example, whether they needed to include multiple families within the span of a

would prefer flerp like Amanda or babber like Andrew. 2-hr support-group meeting). Pilot measures were added

Scoring was the same as for gender peer preferences. and subtracted as time allowed and as it became clear

that they could or could not be understood by partici-

Explicit gender identity. We measured participants’ pants. Some of these items will be adapted for use in

gender identity by telling them that people have outsides follow-up studies, including longitudinal studies of these

(their physical body) and insides (their feelings, thoughts, participants, once wording issues are resolved.

and mind). They were told that some people feel like they

are boys on the outside, and some feel like they are girls

Results

on the outside, and that those people might feel the same

way or different on the inside. They were told some peo- The crucial question was whether transgender children

ple feel, for example, like a boy on the outside and inside, would show (a) a confused pattern of results, as indi-

and that others feel like a boy on the outside but a girl on cated by inconsistency across measures or null effects on

the inside. Further, they were told that some people feel measures; (b) a pattern indicating that they actually knew

like both or neither, or that their feelings change over time. their identity but were merely pretending on explicit

Children were asked whether, on the inside, they felt like measures, as indicated by natal-sex-responding on

a boy, a girl, neither, or both; whether their gender identity implicit measures and expressed-gender-responding on

changed over time; or whether they did not know. explicit measures; or (c) a pattern that mirrored the

responses of other children sharing their gender identity

Missing data and other measures. One sibling, 1 on all measures. When the transgender children’s

control participant, and 2 transgender participants were responses were considered in light of their natal sex,

too young to read and therefore did not complete the their responses differed significantly from those of the

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children 5

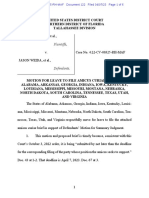

a 0.6

b 0.6

0.4 0.4

Gender-Preference IAT

Gender-Identity IAT

0.2 0.2

0.0 0.0

–0.2 –0.2

–0.4 –0.4

–0.6 –0.6

Controls Siblings Transgender Transgender Controls Siblings Transgender Transgender

by Gender by Sex by Gender by Sex

c 3

d 3

2 2

Explicit Object Preferences

Explicit Peer Preferences

1 1

0 0

–1 –1

–2 –2

–3 –3

Controls Siblings Transgender Transgender Controls Siblings Transgender Transgender

by Gender by Sex by Gender by Sex

Fig. 1. Results of the (a) gender-identity Implicit Association Test (IAT), (b) gender-preference IAT, (c) assessment of explicit peer preferences,

and (d) assessment of explicit object preferences. For each measure, mean scores are shown separately for transgender participants (coded both

for their expressed gender and for their natal sex), control participants, and transgender participants’ siblings. Means above zero indicate prefer-

ences for the same sex or gender, and means below zero indicate preferences for the opposite sex or gender. See the text for further details on

scoring. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean.

two control groups on all measures (ps < .002; see Fig. 1). show a significant preference for their own gender (as

In contrast, when transgender children’s responses were evidenced by a statistically significant positive value) or a

evaluated in terms of their expressed gender, their preference for the other gender (as evidenced by a statis-

response patterns did not differ significantly from those tically significant negative value). Comparisons between

of the two control groups on any measure (ps > .20). groups were conducted using a paired-samples t test,

along with a measure of effect size, Cohen’s d. Trans-

gender children showed a significant implicit preference

Gender-preference IAT for their expressed gender (D = 0.47), t(31) = 7.81, p <

Gender-preference IAT D scores at the group level were .001; control participants showed a significant implicit

compared with 0 using a one-sample t test, which can preference for their natal sex (D = 0.35), t(31) = 3.45, p =

determine whether members of the group on average .002; and the smaller sibling group showed a marginally

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

6 Olson et al.

significant preference for their natal sex (D = 0.31), t(17) = gender peer preference. Transgender children preferred

2.08, p = .053. When considered in light of their expressed objects endorsed by children of their expressed gender

gender, transgender participants did not significantly differ (M = 1.60), t(29) = 7.54, p < .001, d = 1.38. Similarly, con-

from control participants, t(31) = 1.14, p = .262, d = 0.20, trol participants (M = 1.48), t(30) = 7.79, p < .001, d =

or their siblings, t(17) = 1.162, p = .261, d = 0.27. When 1.39, and siblings (M = 1.59), t(16) = 4.77, p < .001, d =

considered in terms of their natal sex, transgender partici- 1.16, preferred objects endorsed by members of their

pants differed from both control participants, t(31) = 6.14, natal sex. When considered according to their expressed

p < .001, d = 1.08, and their siblings, t(17) = 3.96, p = .001, gender, transgender children did not differ significantly

d = 0.92. from control participants, t(28) = 0.317, p = .754, d = 0.06,

or their siblings, t(814) = 0.000, p = 1.00, d = 0.0. When

considered according to their natal sex, transgender chil-

Gender-identity IAT dren differed significantly from both control participants,

The statistical procedure used for the gender-identity IAT t(28) = 11.50, p < .001, d = 2.13, and their siblings, t(14) =

was identical to that used for the gender-preference IAT. 5.45, p < .001, d = 1.41.

All three groups of participants showed significant

implicit gender-identity effects: Transgender children

Explicit gender identity

implicitly identified with their expressed gender (D =

0.30), t(29) = 3.89, p = .001; control participants implicitly In all groups, the majority of participants—81% of control

identified with their natal sex (D = 0.40), t(30) = 4.97, p < participants (n = 26 of 32), 87% of transgender partici-

.001; and siblings identified with their natal sex (D = pants (n = 27 of 31), and 94% of siblings (n = 17 of 18)—

0.26), t(16) = 3.10, p = .007. When considered in terms of indicated that their explicit internal gender identity

their expressed gender, transgender children did not dif- corresponded to their sex (for control participants) or

fer from gender-matched control participants on the gen- expressed their gender (for transgender participants). A

der-identity IAT, t(29) = 1.24, p = .227, d = 0.22, nor did minority of children chose “neither,” “both,” “it changes

they differ from their siblings, t(16) = 0.07, p = .948, d = over time,” or “I don’t know” in response to questions

0.02. When considered in terms of their natal sex, trans- about their internal gender identity. Six control children

gender children differed from both control participants, said either “both” (n = 3) or “I don’t know” (n = 3), and

t(29) = 6.75, p < .001, d = 1.23, and siblings, t(16) = 4.30, 1 sibling said “I don’t know.” In addition, 4 transgender

p = .001, d = 1.06. children said “both” (n = 1), gave a response that corre-

sponded to their natal sex (n = 2), or responded “I don’t

know” (n = 1). Responses that aligned with participants’

Explicit gender peer preferences gender were given a score of 1; any other answer was

To examine explicit gender peer preference, we com- given a 0. Differences between groups were then ana-

pared the means of each participant group with chance lyzed using a McNemar test, which indicated that trans-

(0) via a one-sample t test, whereas differences between gender children’s perceptions did not differ significantly

groups were compared via paired-samples t tests. from those of control participants, p = .727, or siblings,

Transgender participants showed a significant tendency p = .625. If participants were recoded such that 1 indi-

to favor peers of their expressed gender (M = 1.59), cated their natal sex and 0 was any other response, trans-

t(28) = 7.06, p < .001, d = 1.31, as did control participants gender children’s preferences then differed significantly

(M = 1.69), t(31) = 7.60, p < .001, d = 1.34, and siblings from those of both control participants, p < .001, and

(M = 1.41), t(16) = 3.68, p = .002, d = 0.89. When consid- siblings, p < .001.

ered according to their expressed gender, transgender

children did not differ from control participants on their

Discussion

peer preferences, t(28) = 0.20, p = .842, d = 0.04, nor did

they differ from their siblings, t(14) = 0.39, p = .700, d = On both more-controllable self-report measures and less-

0.11. In contrast, when considered according to their natal controllable implicit measures, our group of transgender

sex, transgender children differed from both control par- children showed a clear indication that they thought of

ticipants, t(28) = 10.94, p < .001, d = 2.04, and siblings, themselves in terms of their expressed gender. Their

t(14) = 4.84, p < .001, d = 1.25. responses were indistinguishable from those of the two

cisgender control groups, when matched by gender iden-

tity. They showed a clear preference for peers and objects

Explicit object preferences endorsed by peers who shared their expressed gender,

The statistical procedure used to assess explicit prefer- an explicit and implicit identity that aligned with their

ences for objects was identical to that used for explicit expressed gender, and a strong implicit preference for

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

Gender Cognition in Transgender Children 7

their expressed gender. While future studies are always Conclusion

needed, our results support the notion that transgender

children are not confused, delayed, showing gender- In summary, our findings refute the assumption that trans-

atypical responding, pretending, or oppositional—they gender children are simply confused by the questions at

instead show responses entirely typical and expected for hand, delayed, pretending, or being oppositional. Instead,

children with their gender identity. transgender children show responses that look largely

indistinguishable from those of cisgender children, who

match transgender children’s gender expression on both

Limitations and future directions more- and less-controllable measures. Further, and

The participants in this study are transgender children addressing the broader concern about transgender indi-

who are allowed to live everyday life congruent with viduals’ mere existence raised at the outset of this article,

their gender identity. The primary identity-relevant ten- the data reported here should serve as evidence that

sion they are experiencing is likely between their natal transgender children do indeed exist and that their iden-

sex and their gender expression rather than the combina- tity is a deeply held one.

tion of this tension and the tension between how they

see themselves and how other people see them or soci- Author Contributions

ety sees them on a daily basis. It is unclear whether these All three authors designed the measures and wrote the manu-

findings would then generalize to transgender children script. K. R. Olson led data collection and analysis.

who do not receive support from their families, those

who do not live according to their identified gender in all Acknowledgments

aspects of their daily life, or those who identify them- We thank Yarrow Dunham, Mahzarin Banaji, and David Rand

selves as neither female nor male, or as both, in everyday for feedback on the manuscript, as well as Sarah Colombo, Alia

life (e.g., rejecting male or female pronouns for them- Martin, Arianne Eason, Rachel Horton, Annie Fast, Talee Ziv,

selves and choosing gender-neutral names; Ehrensaft, Melanie Fox, Erin Kelly, Catherine Holland, Sara Haga, Debbie

2011). All of the participants tested here identified and Bitran, and Madeleine DeMeules for assistance with data

lived life as one gender at the time of assessment, choos- collection.

ing names consistent with that gender and preferring

those pronouns as well. Future studies along the spec- Declaration of Conflicting Interests

trum of childhood transgender experiences will be The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with

needed to clarify how generalizable these findings are to respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

children who have different degrees of identified gender

expression or to those with different life experiences. Notes

A second remaining question is how these results in 1. We avoid using common colloquial phrases such as “born as

childhood might relate to persistence of transgender iden- a boy” because they suggest that transgender identities are not

tity later in life (e.g., Drummond, Bradley, Peterson-Badali, innate (an unresolved scientific question) and are thus offensive

& Zucker, 2008; Green, 1987; Wallien & Cohen-Kettenis, to some individuals.

2008). If these measures—for example, the degree of 2. We use the term “opposite” for clarity but acknowledge that

one’s implicit gender identity in childhood—are shown to gender is not binary.

be predictive of transgender experience in adolescence

and adulthood, they may be useful to parents and clini- References

cians, in combination with clinician evaluations, in decid- Byne, W., Bradley, S. J., Coleman, E., Eyler, A. E., Green, R.,

ing about early hormonal and medical interventions that Menvielle, E. J., . . . Tompkins, D. A. (2012). Report of the

can help transgender youths develop bodies that match American Psychiatric Association Task Force on treatment

their expressed gender. Given that other research has of gender identity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior,

shown the utility of the IAT in predicting clinically rele- 41, 759–796.

vant outcomes (Nock & Banaji, 2007; Nock et al., 2010; Drummond, K. D., Bradley, S. J., Peterson-Badali, M., & Zucker,

K. J. (2008). A follow-up study of girls with gender identity

Teachman, Smith-Janik, & Saporito, 2007), the possibility

disorder. Developmental Psychology, 44, 34–45.

that early gender cognition, and in particular, implicit

Dunham, Y., Baron, A. S., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Children and

measures of gender cognition, could be useful in predict- social groups: A developmental analysis of implicit consis-

ing later-life identity (and perhaps informing medical tency in Hispanic Americans. Self and Identity, 6, 238–255.

decisions related to identity) remains a provocative pos- Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody Picture Vocabulary

sibility, though one that would need substantially more Test, fourth edition: Form A. Bloomington, MN: NCS

testing before the IAT could be used in this way. Pearson.

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

8 Olson et al.

Ehrensaft, D. (2011). Gender born, gender made: Raising Implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological

healthy gender-nonconforming children. New York, NY: Science, 21, 511–517.

The Experiment. Payne, E. (2013, June 24). Transgender first-grader wins the

Green, R. (1987). The “sissy boy syndrome” and the development right to use girls’ restroom. CNN. Retrieved from http://

of homosexuality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. www.cnn.com/2013/06/24/us/colorado-transgender-girl-

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., Rudman, L. A., Farnham, S. D., school/

Nosek, B. A., & Mellott, D. S. (2002). A unified theory of Raddatz, K. (2014, December 4). MSHSL votes to approve pol-

implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-con- icy for transgender athletes. CBS Minnesota. Retrieved from

cept. Psychological Review, 1, 3–25. http://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2014/12/04/transgender-

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). athlete-policy-heads-to-vote/

Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Rutland, A., Cameron, L., Milne, A., & McGeorge, P. (2005).

Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Social norms and self-presentation: Children’s implicit

Psychology, 74, 1464–1480. and explicit intergroup attitudes. Child Development, 76,

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). 451–466.

Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. Shutts, K., Banaji, M. R., & Spelke, E. S. (2010). Social catego-

An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and ries guide young children’s preferences for novel objects.

Social Psychology, 85, 197–216. Developmental Science, 13, 599–610.

Greenwald, A. G., Poehlman, T. A., Uhlmann, E. L., & Banaji, Spack, N. P., Edwards-Leeper, L., Feldman, H. A., Leibowitz, S.,

M. R. (2009). Understanding and using the Implicit Mandel, F., Diamond, D. A., & Vance, S. R. (2012). Children

Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. and adolescents with gender identity disorder referred to a

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 17–41. pediatric medical center. Pediatrics, 129, 418–425.

Gregg, A. P., Seibt, B., & Banaji, M. R. (2006). Easier done than Teachman, B. A., Smith-Janik, S. B., & Saporito, J. (2007).

undone: Asymmetry in the malleability of implicit prefer- Information processing biases and panic disorder:

ences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 1–20. Relationships among cognitive and symptom measures.

McDaniel, M. J., Beier, M. E., Perkins, A. W., Goggin, S., & Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 1791–1811.

Frankel, B. (2009). An assessment of the fakeability of self- Wallien, M. S. C., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2008). Psychosexual

report and implicit personality measures. Personality and outcomes of gender-dysphoric children. Journal of the

Individual Differences, 43, 682–685. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47,

McHugh, P. (2014, June 12). Transgender surgery isn’t the 1413–1423.

solution. Wall Street Journal Op-Ed. Retrieved from http:// Walsh, M. (2014, June 3). This poor child is confused, not

online.wsj.com/articles/paul-mchugh-transgender-surgery- ‘transgendered’ [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://

isnt-the-solution-1402615120 themattwalshblog.com/2014/06/03/this-poor-child-is-

Newheiser, A., & Olson, K. R. (2012). White and Black chil- confused-not-transgendered/

dren’s implicit intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental The Whittington Family. (2014, May 27). The Whittington fam-

Social Psychology, 48, 264–270. ily: Ryland’s story [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www

Nock, M. K., & Banaji, M. R. (2007). Prediction of suicide ide- .youtube.com/watch?v=yAHCqnux2fk

ation and attempts among adolescents using a brief per- Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., Kuksis, M., Pecore, K., Birkenfeld-

formance-based test. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Adams, A., Doering, R. W., . . . Wild, J. (1999). Gender

Psychology, 75, 707–715. constancy judgments in children with gender identity dis-

Nock, M. K., Park, J. M., Finn, C. T., Deliberto, T. L., Dour, order: Evidence for a developmental lag. Archives of Sexual

H. J., & Banaji, M. R. (2010). Measuring the suicidal mind: Behavior, 28, 475–502.

Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com by Kristina Olson on March 6, 2015

You might also like

- Transmaxxing 4Document57 pagesTransmaxxing 4vintologi50% (4)

- The Transgender Child: A Handbook for Families and ProfessionalsFrom EverandThe Transgender Child: A Handbook for Families and ProfessionalsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Source Library PDFDocument71 pagesSource Library PDFMaria LimaNo ratings yet

- Transgender Youth and The Freedom To Be Ourselves: Messaging GuideDocument13 pagesTransgender Youth and The Freedom To Be Ourselves: Messaging GuideMary Margaret Olohan0% (1)

- 2021 North Dakota LGBTQ+ School Climate ReportDocument44 pages2021 North Dakota LGBTQ+ School Climate ReportinforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Transgender BrainDocument8 pagesTransgender Brainclau_alcaideNo ratings yet

- Romancing the Sperm: Shifting Biopolitics and the Making of Modern FamiliesFrom EverandRomancing the Sperm: Shifting Biopolitics and the Making of Modern FamiliesNo ratings yet

- SOAP Note and Literature Review 1Document8 pagesSOAP Note and Literature Review 1api-457706578No ratings yet

- SOAP Note and Literature Review 1Document8 pagesSOAP Note and Literature Review 1api-457706578No ratings yet

- PSICOLOGÍA - Durwood (2016) - Mental Health and Self-Worth in Socially-Transitioned Transgender YouthDocument28 pagesPSICOLOGÍA - Durwood (2016) - Mental Health and Self-Worth in Socially-Transitioned Transgender YouthMiizhy CakeNo ratings yet

- AFSproof2EmbodyingGenderSex MK Proof3Document61 pagesAFSproof2EmbodyingGenderSex MK Proof3eya haouariNo ratings yet

- Mental Health of Transgender ChildrenDocument10 pagesMental Health of Transgender ChildrenMarian Mario SpagnuoloNo ratings yet

- Sahar Sadjadi Pediatric Transition CADocument27 pagesSahar Sadjadi Pediatric Transition CAAnonymous X2hRgdNo ratings yet

- Final Exam - Essay 3Document7 pagesFinal Exam - Essay 3api-588234268No ratings yet

- From Gender Identity Disorder To Gender Identity CreativityDocument21 pagesFrom Gender Identity Disorder To Gender Identity CreativityGender SpectrumNo ratings yet

- I Knew That I Wasn T Cis I Knew That But I Didn T Know Exactly Gender Identity Development Expression and Affirmation in Youth Who Access GenderDocument15 pagesI Knew That I Wasn T Cis I Knew That But I Didn T Know Exactly Gender Identity Development Expression and Affirmation in Youth Who Access GenderwehattrichNo ratings yet

- Gender Independent Kids: A Paradigm Shift in Approaches To Gender Non-Conforming ChildrenDocument10 pagesGender Independent Kids: A Paradigm Shift in Approaches To Gender Non-Conforming ChildrenIrisha AnandNo ratings yet

- Myth: Children Are Too Young To Know Their Gender.: Some Common Myths About GenderDocument3 pagesMyth: Children Are Too Young To Know Their Gender.: Some Common Myths About GenderJastin GalariaNo ratings yet

- Gender Development in Transgender Preschool ChildrenDocument19 pagesGender Development in Transgender Preschool ChildrenPía Rodríguez GarridoNo ratings yet

- Rahilly Genderbinarymeets 2015Document25 pagesRahilly Genderbinarymeets 2015Cliff CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Sexual Identity and Gender IdentityDocument5 pagesSexual Identity and Gender IdentityDiego JoaquínNo ratings yet

- Are Children SexualDocument18 pagesAre Children SexualBelén CabreraNo ratings yet

- INFANCIA - Temple (2018) A Critical Commentary On Follow-Up Studies and Desistance Theories About Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming ChildrenDocument14 pagesINFANCIA - Temple (2018) A Critical Commentary On Follow-Up Studies and Desistance Theories About Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming ChildrenMiizhy CakeNo ratings yet

- Perspectives On Gender DevelopmentDocument9 pagesPerspectives On Gender DevelopmentJianaNo ratings yet

- Revisión Del Género Polderman Et Al PDFDocument14 pagesRevisión Del Género Polderman Et Al PDFDaniel Molina TorresNo ratings yet

- Interest PaperDocument8 pagesInterest Paperapi-328741177No ratings yet

- Recommendations For Using Transgender-Inclusive Language in Sex Education CurriculaDocument15 pagesRecommendations For Using Transgender-Inclusive Language in Sex Education CurriculaCarlo Jesús Orellano QuijanoNo ratings yet

- Transgender Facing Social Issues in Kohat Community: Submitted To: Dr. Mamoon KhattakDocument29 pagesTransgender Facing Social Issues in Kohat Community: Submitted To: Dr. Mamoon KhattakHassan Bilal KhanNo ratings yet

- Homosexuality Nature or Nurture Research PaperDocument8 pagesHomosexuality Nature or Nurture Research Paperqwmojqund100% (1)

- Child Abuse in IndiaDocument5 pagesChild Abuse in IndiaAsha YadavNo ratings yet

- Gender Affirmative Care ModelDocument6 pagesGender Affirmative Care ModelGender Spectrum0% (1)

- BARRON, C and CAPOUS-DESYLLAS, M - Transgressing The Gendered Norms in Childhood - Transgender Children and Families PDFDocument33 pagesBARRON, C and CAPOUS-DESYLLAS, M - Transgressing The Gendered Norms in Childhood - Transgender Children and Families PDFArthurLeonardoDaCostaNo ratings yet

- Gender Stereotypes and RolesDocument29 pagesGender Stereotypes and Rolesakhilav.mphilNo ratings yet

- INFANCIA - Turban (2017) Transgender Youth - The Building Evidence Base For Early Social TransitionDocument2 pagesINFANCIA - Turban (2017) Transgender Youth - The Building Evidence Base For Early Social TransitionMiizhy CakeNo ratings yet

- Gender Essentialism in Transgender and Cisgender CDocument12 pagesGender Essentialism in Transgender and Cisgender CLaura Núñez MoraledaNo ratings yet

- The Question of Nature VsDocument3 pagesThe Question of Nature VssimonroigNo ratings yet

- Gender and Sexuality in Autism, Explained: Spectrum - Autism Research NewsDocument4 pagesGender and Sexuality in Autism, Explained: Spectrum - Autism Research NewsFranco Paolo Maray-GhigliottoNo ratings yet

- Child Psychology Research PaperDocument7 pagesChild Psychology Research PaperJamal DeNo ratings yet

- Parent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults Perceived To Show Signs of A Rapid Onset of Gender DysphoriaDocument44 pagesParent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults Perceived To Show Signs of A Rapid Onset of Gender DysphoriaSUMIT BORHADENo ratings yet

- Martin ChildrensSearchGender 2004Document5 pagesMartin ChildrensSearchGender 2004Cliff CoutinhoNo ratings yet

- Conformity To Peer Pressure in Preschool Children: Daniel B. M. Haun Michael TomaselloDocument9 pagesConformity To Peer Pressure in Preschool Children: Daniel B. M. Haun Michael TomaselloCintia Ferris LanteroNo ratings yet

- It Was Probably One of The Best Moments of Being Trans, Honestly!' - Exploring The Positive School Experiences of Transgender Children and Young People.Document17 pagesIt Was Probably One of The Best Moments of Being Trans, Honestly!' - Exploring The Positive School Experiences of Transgender Children and Young People.nunuNo ratings yet

- SHO - The Benefits of Birds & Bees Talk With ParentsDocument3 pagesSHO - The Benefits of Birds & Bees Talk With ParentsShierlen OctaviaNo ratings yet

- Field Methods in Psychology: Exploring The Experiences of Generation X To Corporal Punishment: A Phenomenological StudyDocument4 pagesField Methods in Psychology: Exploring The Experiences of Generation X To Corporal Punishment: A Phenomenological StudyMarcus Andrei Melgar PaulinoNo ratings yet

- Example of Reaction PaperDocument1 pageExample of Reaction PaperEdi SongNo ratings yet

- Intersex and Gender Assignment - The Third WayDocument5 pagesIntersex and Gender Assignment - The Third Wayoreuridika100% (1)

- E Riley Thesis November2012 PDFDocument222 pagesE Riley Thesis November2012 PDFMary Rose GaNo ratings yet

- HSE Intervention Paper (Prejudice)Document13 pagesHSE Intervention Paper (Prejudice)Ahmed ArihaNo ratings yet

- Gender Identity DevelopmentDocument3 pagesGender Identity DevelopmentLucía LópezNo ratings yet

- Descriptions of Childhood Trauma Effects of The Trauma and How PDFDocument168 pagesDescriptions of Childhood Trauma Effects of The Trauma and How PDFColten Kollenborn0% (1)

- The Mating Psychology of Incels (By William Costello)Document55 pagesThe Mating Psychology of Incels (By William Costello)mahdi abdollahiNo ratings yet

- Homosexuality in Childhood and PrejudiceDocument8 pagesHomosexuality in Childhood and PrejudiceAnggalimea AngwenNo ratings yet

- Seeing Psychology in Personal Experience: Intro To Psychology Term PaperDocument8 pagesSeeing Psychology in Personal Experience: Intro To Psychology Term PaperChristina CannilaNo ratings yet

- Gender Schema Theory and Its ImplicationDocument20 pagesGender Schema Theory and Its ImplicationShyna SinghNo ratings yet

- Martin OlsonDocument18 pagesMartin OlsonZikk ZikNo ratings yet

- Coming Out As Gay A Phenomenological Study About Adolescents Disclosing Their Homosexuality To Their ParentsDocument15 pagesComing Out As Gay A Phenomenological Study About Adolescents Disclosing Their Homosexuality To Their ParentsS ONo ratings yet

- Supporting & Caring For: TransgenderDocument24 pagesSupporting & Caring For: TransgenderTitiksha JoshiNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 13.234.121.200 On Sat, 21 Aug 2021 14:49:40 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 13.234.121.200 On Sat, 21 Aug 2021 14:49:40 UTCSagnik BagNo ratings yet

- Topic Proposal: "I'm Not Racist, My Neighbor Is Black!": A Look at Implicit Bias Introduction/OverviewDocument3 pagesTopic Proposal: "I'm Not Racist, My Neighbor Is Black!": A Look at Implicit Bias Introduction/OverviewbrendanNo ratings yet

- Reginio Shella # 2Document15 pagesReginio Shella # 2Kriss GalanNo ratings yet

- Sibling, Family, and Social Influences On Children's Theory of Mind Understanding: New Evidence From Diverse Intracultural SamplesDocument16 pagesSibling, Family, and Social Influences On Children's Theory of Mind Understanding: New Evidence From Diverse Intracultural SamplesAnonymous 75M6uB3OwNo ratings yet

- Haun - Tomasello - 2011 - Conformity To Peer Pressure in Preschool Children - Child - Dev PDFDocument9 pagesHaun - Tomasello - 2011 - Conformity To Peer Pressure in Preschool Children - Child - Dev PDFIoana Voina100% (1)

- The End of A Stereotype - Only Children Are Not More Narcissistic Than People With SiblingsDocument9 pagesThe End of A Stereotype - Only Children Are Not More Narcissistic Than People With SiblingsYashasviniNo ratings yet

- Federal Judge Ruling in Transgender Sports LawsuitDocument23 pagesFederal Judge Ruling in Transgender Sports LawsuitWCHS DigitalNo ratings yet

- SVP 2006 Annual ReportDocument18 pagesSVP 2006 Annual ReportRobert LedermanNo ratings yet

- Education Law Center Open Letter Hempfield PolicyDocument5 pagesEducation Law Center Open Letter Hempfield PolicyAshley StalneckerNo ratings yet

- Transgender Student Model PoliciesDocument27 pagesTransgender Student Model PoliciesSara Grace ToddNo ratings yet

- March/April 2022 PNNDocument20 pagesMarch/April 2022 PNNSisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, St. LouisNo ratings yet

- Massachusetts Commission On Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer & Questioning Youth Annual Recommendations FY 2024Document295 pagesMassachusetts Commission On Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer & Questioning Youth Annual Recommendations FY 2024ThePoliticalHatNo ratings yet

- Related Review LiteratureDocument4 pagesRelated Review LiteratureRigel YunzalNo ratings yet

- INFANCIA - Turban (2017) Transgender Youth - The Building Evidence Base For Early Social TransitionDocument2 pagesINFANCIA - Turban (2017) Transgender Youth - The Building Evidence Base For Early Social TransitionMiizhy CakeNo ratings yet

- Temporary Injunction OrderDocument7 pagesTemporary Injunction OrderRob LauciusNo ratings yet

- Effects of Having Homophobic ParentsDocument6 pagesEffects of Having Homophobic ParentsKian Joshua FresnidoNo ratings yet

- Dekker V Weida Amicus Brief by 17 AGsDocument35 pagesDekker V Weida Amicus Brief by 17 AGsSarah WeaverNo ratings yet

- NHRC Research (Final)Document14 pagesNHRC Research (Final)its.deepanshu.dabasNo ratings yet

- Educational Inequality in India: A Review Paper For Transgender PopulationDocument7 pagesEducational Inequality in India: A Review Paper For Transgender PopulationEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Queer and TransgenderDocument13 pagesQueer and TransgenderJanin GallanaNo ratings yet

- Ten Years of Gender Recognition in The United Kingdom Still A Model For ReformDocument8 pagesTen Years of Gender Recognition in The United Kingdom Still A Model For ReformPradeep GangwarNo ratings yet

- Gender at SexDocument10 pagesGender at SexJastin GalariaNo ratings yet

- Version 1 On JCPS Policy Regarding SB 150Document19 pagesVersion 1 On JCPS Policy Regarding SB 150Krista JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Final Exam - Essay 3Document7 pagesFinal Exam - Essay 3api-588234268No ratings yet

- 4th Circuit Gavin GrimmDocument95 pages4th Circuit Gavin GrimmLaw&Crime100% (1)

- Erich FrommDocument35 pagesErich FrommBVS CollegesNo ratings yet

- BAGLY V Azar Amended Complaint PDFDocument107 pagesBAGLY V Azar Amended Complaint PDFRicca PrasadNo ratings yet

- Review of LiteratureDocument32 pagesReview of Literaturekanika sengarNo ratings yet

- Reactions of STEM 12 Alpha of VMA Global College About LGBT CommunityDocument31 pagesReactions of STEM 12 Alpha of VMA Global College About LGBT CommunityKimochi SenpaiiNo ratings yet

- THE SITUATION OF LGBTQ CHILDREN IN THE PHILIPPINES A Report by The Commission On Human Rights December 2019Document39 pagesTHE SITUATION OF LGBTQ CHILDREN IN THE PHILIPPINES A Report by The Commission On Human Rights December 2019Mohajirin PangolimaNo ratings yet

- LGBTQ Fact Sheet - Student Achievement and Educational AttainmentDocument3 pagesLGBTQ Fact Sheet - Student Achievement and Educational Attainmentapi-333274178No ratings yet