Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Energy and Geopolitics in The South China Sea

Energy and Geopolitics in The South China Sea

Uploaded by

Isaac GoldCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Details of 127 Unauthorised Residential Layouts With in Bangalore DevelopmentDocument32 pagesDetails of 127 Unauthorised Residential Layouts With in Bangalore Developmentsanjay2_2260% (5)

- Executable Green Hydrogen: and A Strategic Growth PathDocument14 pagesExecutable Green Hydrogen: and A Strategic Growth PathIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Entering Uncharted Waters?: ASEAN and the South China SeaFrom EverandEntering Uncharted Waters?: ASEAN and the South China SeaNo ratings yet

- The 4th Scs Workshop Booket - FinalDocument85 pagesThe 4th Scs Workshop Booket - FinalVân Gỗ Anpro SànNo ratings yet

- Japan Forum 2023 Program Draft (08.02)Document33 pagesJapan Forum 2023 Program Draft (08.02)周雨臻No ratings yet

- Piracy, Maritime Terrorism and Securing The Malacca Straits (Graham Gerard Ong-Webb)Document304 pagesPiracy, Maritime Terrorism and Securing The Malacca Straits (Graham Gerard Ong-Webb)Bica CapãoNo ratings yet

- Naval Modernisation and Southeast Asias SecurityDocument32 pagesNaval Modernisation and Southeast Asias SecurityTiên Đào TrầnNo ratings yet

- Maritime Security in East and Southeast Asia - Political Challenges in Asian WatersDocument261 pagesMaritime Security in East and Southeast Asia - Political Challenges in Asian WatersravelobeNo ratings yet

- The South China Sea Dispute: Navigating Diplomatic and Strategic TensionsFrom EverandThe South China Sea Dispute: Navigating Diplomatic and Strategic TensionsNo ratings yet

- Marine Litter News Vol10 Issue 2Document34 pagesMarine Litter News Vol10 Issue 2Ning YenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document8 pagesChapter 1hyhyhyhyhy12345No ratings yet

- Energy Conservation in Asia PDFDocument410 pagesEnergy Conservation in Asia PDFMaria Zsuzsanna FortesNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics OceanographyDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics Oceanographyd0f1lowufam3100% (1)

- 12 Nov Roundtable ReportDocument1 page12 Nov Roundtable ReportsaleihasharifNo ratings yet

- 28 Ooi 4Document21 pages28 Ooi 4wedoke2633No ratings yet

- Chinese Acquisition of The Spratly Archipelago 2005 SEGÚNDocument17 pagesChinese Acquisition of The Spratly Archipelago 2005 SEGÚNLivia RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Textbook Environmental Resources Use and Challenges in Contemporary Southeast Asia Mario Ivan Lopez Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument47 pagesTextbook Environmental Resources Use and Challenges in Contemporary Southeast Asia Mario Ivan Lopez Ebook All Chapter PDFfrancisco.brown366100% (15)

- The Spatial Distribution and Morphological CharacteristicsDocument16 pagesThe Spatial Distribution and Morphological Characteristicsm992104wNo ratings yet

- Techniques in Play Fairway AnalysisDocument3 pagesTechniques in Play Fairway AnalysisblasuaNo ratings yet

- WP198Document43 pagesWP198Norberto O. YamuganNo ratings yet

- Science of The Total Environment: ReviewDocument18 pagesScience of The Total Environment: ReviewSandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Status of Research, Legal and Policy Efforts On Marine Plastics in Asean+3Document427 pagesStatus of Research, Legal and Policy Efforts On Marine Plastics in Asean+3nurul masyiah rani harusiNo ratings yet

- Asian Institute of Maritime StudiesDocument120 pagesAsian Institute of Maritime Studiesde coderNo ratings yet

- Polj 15Document4 pagesPolj 15AnaNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Investigating Oceanography 4Th Edition Keith A Sverdrup Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Investigating Oceanography 4Th Edition Keith A Sverdrup Online PDF All Chapteranthonyhearnen36898100% (6)

- UAI Jaklugri Dan Kam RRT 9 - China in Indo-Pacific RegionDocument23 pagesUAI Jaklugri Dan Kam RRT 9 - China in Indo-Pacific RegionZulfahmiNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Coral Reefs of Eastern Asia Under Anthropogenic Impacts 1St Edition Ichiro Takeuchi Hideyuki Yamashiro Eds Online PDF All ChapterDocument70 pagesFull Ebook of Coral Reefs of Eastern Asia Under Anthropogenic Impacts 1St Edition Ichiro Takeuchi Hideyuki Yamashiro Eds Online PDF All Chaptergskmedupi7100% (14)

- Maritime Law Research PaperDocument24 pagesMaritime Law Research PaperRoshan ShakNo ratings yet

- I 01020 2 Source Rocks in Space and Through TimeDocument5 pagesI 01020 2 Source Rocks in Space and Through Timedino_birds6113No ratings yet

- Marine Student Research Projects 2020Document18 pagesMarine Student Research Projects 2020prasanta khillaNo ratings yet

- Saleh-Etal AJES 2010Document6 pagesSaleh-Etal AJES 2010art_5No ratings yet

- The South China SeaDocument33 pagesThe South China SeaRizwanNo ratings yet

- Marine Annelida (Excluding Clitellates and Siboglinids) From The South China SeaDocument58 pagesMarine Annelida (Excluding Clitellates and Siboglinids) From The South China SeaOrmphipod WongkamhaengNo ratings yet

- Wyrtki, K. (1961)Document226 pagesWyrtki, K. (1961)osemetmil subdisNo ratings yet

- FSTE E-Newsletter, Issue 2, 2011Document12 pagesFSTE E-Newsletter, Issue 2, 2011military75No ratings yet

- Coastal Marine Biodiversity of VietnamDocument89 pagesCoastal Marine Biodiversity of Vietnamhoang ngoc KhacNo ratings yet

- Wolff Et Al. Challenges in TCZM 2023Document347 pagesWolff Et Al. Challenges in TCZM 2023Arturo Dominici-ArosemenaNo ratings yet

- RAG2003 RajangLateQuaternaryDocument21 pagesRAG2003 RajangLateQuaternaryHarald JungkimNo ratings yet

- China in Oceania: Reshaping the Pacific?From EverandChina in Oceania: Reshaping the Pacific?Terence Wesley-SmithNo ratings yet

- Expert Lecture - Dr. Shu-Qing Yang - InvitationDocument1 pageExpert Lecture - Dr. Shu-Qing Yang - InvitationAnonymous KyLhn6No ratings yet

- Li Et Al-2015-Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid EarthDocument23 pagesLi Et Al-2015-Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid EarthainiNo ratings yet

- 2023 NEREC Summer Fellows Program AnnouncementDocument6 pages2023 NEREC Summer Fellows Program AnnouncementMy KiwidoNo ratings yet

- PHYSICALOCEANOGRAPHY2014Document10 pagesPHYSICALOCEANOGRAPHY2014곽수진No ratings yet

- ASPI SChinaSeareport FinDocument53 pagesASPI SChinaSeareport Finabhijeetkbhatt7No ratings yet

- Atwood Colostate 0053N 11216 OptDocument121 pagesAtwood Colostate 0053N 11216 Optceleste mulenaNo ratings yet

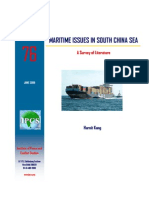

- SR76 Harneet FinalDocument10 pagesSR76 Harneet Finalsaiful_zNo ratings yet

- PDF Investigating Oceanography Raphael Kudela Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Investigating Oceanography Raphael Kudela Ebook Full Chaptermargaret.redd792100% (4)

- Maritime Confidence Building MeasuresDocument52 pagesMaritime Confidence Building MeasuresBinh ThaiNo ratings yet

- Marine Microbiology Conference-2nd CircularlDocument14 pagesMarine Microbiology Conference-2nd CircularlTueNo ratings yet

- Observed and Perceived Environmental Impacts of Marine Protected Areas in Two Southeast Asia SitesDocument20 pagesObserved and Perceived Environmental Impacts of Marine Protected Areas in Two Southeast Asia SitesRannie Ayaay Jr.No ratings yet

- RAG2003 RajangLateQuaternaryDocument21 pagesRAG2003 RajangLateQuaternaryLutherbongCheeBuiNo ratings yet

- Dr. Shu-Qing Yang - Profile2Document1 pageDr. Shu-Qing Yang - Profile2Anonymous KyLhn6No ratings yet

- Wibowo - 2022 - IOP - Conf. - Ser. - Earth - Environ. - Sci. - 1118 - 012069Document16 pagesWibowo - 2022 - IOP - Conf. - Ser. - Earth - Environ. - Sci. - 1118 - 012069Arief WibowoNo ratings yet

- JealDocument25 pagesJealNovella LerianNo ratings yet

- Huang Etal 2020 MARPET MacclesfieldBankDocument13 pagesHuang Etal 2020 MARPET MacclesfieldBankAjeng Sulis WidyastutiNo ratings yet

- Status of Coral Reefs South East AsiaDocument237 pagesStatus of Coral Reefs South East AsiaDina Peter ShawnNo ratings yet

- Marine and Maritime Studies ATAR Y12 Sample Course Outline WACE 2015 16Document5 pagesMarine and Maritime Studies ATAR Y12 Sample Course Outline WACE 2015 16partyNo ratings yet

- Data Keynote Speaker Aisce 2Document4 pagesData Keynote Speaker Aisce 2Budi AuliaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On OceanographyDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Oceanographyqzetcsuhf100% (1)

- Weeden 2020Document16 pagesWeeden 2020Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Juan o Savin No Quarter DeckDocument11 pagesJuan o Savin No Quarter DeckIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Lncomt: Dmdend Wablo Rdundo, Credk 0 Offs& of Stata and Lcr3L Itrcomr Hxa-G (Sed PawDocument7 pagesLncomt: Dmdend Wablo Rdundo, Credk 0 Offs& of Stata and Lcr3L Itrcomr Hxa-G (Sed PawIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Incoftic: 201,421 Twinltrdlcrcom (Raspa Rs Af&H F3'N V 17,140 Tu-Cx Phterd ( P@GC)Document2 pagesIncoftic: 201,421 Twinltrdlcrcom (Raspa Rs Af&H F3'N V 17,140 Tu-Cx Phterd ( P@GC)Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- 9565 FSAI VitaminsandMinerals Report FA3Document160 pages9565 FSAI VitaminsandMinerals Report FA3Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- B Clinton 1992Document15 pagesB Clinton 1992Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Legislative Assembly: That This Bill Be Now Agreed To in PrincipleDocument25 pagesLegislative Assembly: That This Bill Be Now Agreed To in PrincipleIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Factors and Hair Loss: Clinical Dermatology - Review ArticleDocument9 pagesNutritional Factors and Hair Loss: Clinical Dermatology - Review ArticleIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Ics 12600Document22 pagesIcs 12600Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Convertibles Primer: Convertible SecuritiesDocument6 pagesConvertibles Primer: Convertible SecuritiesIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Rho-Kinase Regulates Prostaglandin D - Stimulated Heat Shock Protein 27 Induction in OsteoblastsDocument5 pagesRho-Kinase Regulates Prostaglandin D - Stimulated Heat Shock Protein 27 Induction in OsteoblastsIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Fixed Income Strategist: Price Discovery ModeDocument30 pagesFixed Income Strategist: Price Discovery ModeIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Amsa1110 Master Less Than 80 Metres Near CoastalDocument26 pagesAmsa1110 Master Less Than 80 Metres Near CoastalIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- HTTP WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au House Committee JSCC Subs Sub 136.3Document101 pagesHTTP WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au House Committee JSCC Subs Sub 136.3Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- National Continuity Policy Implementation Plan: Homeland Security CouncilDocument102 pagesNational Continuity Policy Implementation Plan: Homeland Security CouncilIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Cfnai Technical Report PDFDocument3 pagesCfnai Technical Report PDFIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Amsa1109 Master Less Than 35m NC and Mate Less Than 80m NC 0Document18 pagesAmsa1109 Master Less Than 35m NC and Mate Less Than 80m NC 0Isaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Perbandingan Jumlah Eritrosit Pada Sampel Darah 3, 2 Dan 1 ML Dengan Antikoagulan K2EdtaDocument6 pagesPerbandingan Jumlah Eritrosit Pada Sampel Darah 3, 2 Dan 1 ML Dengan Antikoagulan K2EdtaNia AzNo ratings yet

- OHSAS 18001 Work Instruction and SOPsDocument5 pagesOHSAS 18001 Work Instruction and SOPsAlina Walace0% (1)

- Math 8 Q3 Module 5 With Answer KeyDocument13 pagesMath 8 Q3 Module 5 With Answer KeyJimcris villamorNo ratings yet

- Angew,. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, No. 9, 1306Document3 pagesAngew,. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, No. 9, 1306elderwanNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Intermediate Accounting 8th Edition Spiceland Solutions Manual PDFDocument12 pagesDwnload Full Intermediate Accounting 8th Edition Spiceland Solutions Manual PDFsorbite.bebloodu2hh0j100% (15)

- Environmental Protection and Awareness Project ProposalDocument14 pagesEnvironmental Protection and Awareness Project ProposalRUS SELLNo ratings yet

- Plasticity - Rubber PDFDocument3 pagesPlasticity - Rubber PDFsujudNo ratings yet

- The Building Blocks of Visual DesignDocument33 pagesThe Building Blocks of Visual DesignevandalismNo ratings yet

- Blue Distinction Specialty Care Program Implementation UpdateDocument2 pagesBlue Distinction Specialty Care Program Implementation Updaterushi810No ratings yet

- Defiant RPG - GM Guide (Electronic Version) XDocument9 pagesDefiant RPG - GM Guide (Electronic Version) XXosé Lois PérezNo ratings yet

- 1575517183688JlPSe5QaAila2orp PDFDocument15 pages1575517183688JlPSe5QaAila2orp PDFPr Satish BethaNo ratings yet

- Portarlington Parish NewsletterDocument2 pagesPortarlington Parish NewsletterJohn HayesNo ratings yet

- KVP Measurements On Mammography Machines With The Raysafe X2 SystemDocument7 pagesKVP Measurements On Mammography Machines With The Raysafe X2 SystemomarcuratoloNo ratings yet

- FMCG Organisation Chart: Board of DirectorsDocument1 pageFMCG Organisation Chart: Board of DirectorsKumar Panchal0% (1)

- PRIsDocument11 pagesPRIsbobby choudharyNo ratings yet

- BVM L230Document156 pagesBVM L230JFrink333No ratings yet

- The Role of IRCTC Train Booking AgentsDocument7 pagesThe Role of IRCTC Train Booking AgentsRahul officalNo ratings yet

- The Current WarDocument1 pageThe Current WarkanuvietNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Linear Regression Using Excel 2010-GOODDocument5 pagesChapter 6 Linear Regression Using Excel 2010-GOODS0% (1)

- Assignment For InterviewDocument34 pagesAssignment For InterviewBurugolla RaviNo ratings yet

- SHELL100 12pDocument2 pagesSHELL100 12pLuizABastosNo ratings yet

- Sacred Science Publishes Financial Text Introducing The Planetary Time Forecasting MethodDocument2 pagesSacred Science Publishes Financial Text Introducing The Planetary Time Forecasting Methodkalai2No ratings yet

- Anthropometrics ErgonomicsDocument78 pagesAnthropometrics ErgonomicsashokdinoNo ratings yet

- ResMed CPAP-2012Document23 pagesResMed CPAP-2012navnaNo ratings yet

- Anderson Distribution of The Correlation CoefficientDocument14 pagesAnderson Distribution of The Correlation Coefficientdauren_pcNo ratings yet

- Coordinte GeometryDocument72 pagesCoordinte GeometrySukhamrit PalNo ratings yet

- 80 3689 01 Threaded ConnectionsDocument12 pages80 3689 01 Threaded ConnectionsMiguel Alfonso Ruiz MendezNo ratings yet

- Community Forest 1Document20 pagesCommunity Forest 1Ananta ChaliseNo ratings yet

- Harga Daikin ACDocument9 pagesHarga Daikin ACIlham CaisarNo ratings yet

Energy and Geopolitics in The South China Sea

Energy and Geopolitics in The South China Sea

Uploaded by

Isaac GoldOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Energy and Geopolitics in The South China Sea

Energy and Geopolitics in The South China Sea

Uploaded by

Isaac GoldCopyright:

Available Formats

ENERGY AND GEOPOLITICS

IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) was established as an

autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study

of socio-political, security and economic trends and developments in Southeast

Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s

research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN

and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social

and Cultural Studies (RSCS).

ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued almost

2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about

Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other

academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research

and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world.

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 2 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

Report No. 8

ENERGY AND GEOPOLITICS

IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA

Implications for ASEAN and its Dialogue Partners

INSTITUTE OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES

Singapore

First published in Singapore in 2009 by

ISEAS Publishing

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace

Pasir Panjang

Singapore 119614

E-mail: publish@iseas.edu.sg

Website: bookshop.iseas.edu.sg

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission

of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

© 2009 Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

The responsibility for facts and opinions in this publication rests exclusively

with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the

views or the policy of the publisher or its supporters.

ISEAS Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Energy and geopolitics in the South China Sea : implications for ASEAN and its

dialogue partners.

(Report / ASEAN Studies Centre ; no. 8).

1. ASEAN.

2. Territorial waters—South China Sea.

3. South China Sea.

I. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ASEAN Studies Centre.

II. Series.

JZ5333.5 A9A85 no. 8 2009

ISBN 978-981-230-989-1 (soft cover)

ISBN 978-981-230-992-1 (E-book PDF)

Typeset by Superskill Graphics Pte Ltd

Printed in Singapore by Seng Lee Press Pte Ltd

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 4 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

CONTENTS

Preface vii

Lead Article

• Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea:

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 1

• Michael Richardson

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS),

Singapore

Commentaries

• Sam Bateman 41

Senior Fellow

S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS),

Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

• B.A. Hamzah 53

Senior Research Fellow

Institute of Ocean and Earth Sciences (IOES),

University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Articles

• Flashpoint: South China Sea 65

• K. Kesavapany

Director

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS),

Singapore

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 5 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

vi Contents

• Whither the South China Sea Disputes? 68

• Mark J. Valencia

Visiting Senior Fellow

Maritime Institute of Malaysia

• Clarifying the New Philippine Baselines Law 74

• Rodolfo C. Severino

Head, ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC)

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS),

Singapore

About the Contributors 77

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 6 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

PREFACE

The South China Sea is generally considered as one of the

flashpoints for conflict in East Asia. With its vast expanse, the

South China Sea’s many small land features and indeterminate

maritime regimes are the subject of conflicting claims among

China and Taiwan and four member-countries of the Association

of Southeast Asian Nations. These multiple claims vary in nature

and extent, making the situation most complex and extremely

difficult, if not impossible, to adjudicate.

Yet, this maritime body is vital not only to the claimant-

states, not only to the littoral lands, but globally as well. Through

the South China Sea pass ships carrying more than half of the

world’s trade. The presence in and passage through it of American

and other naval vessels enable the United States and other powers

to project their military weight in that part of the world. According

to the Energy Information Administration of the United States

Government, a 1993–94 estimate by the U.S. Geological Survey

placed the total of discovered oil reserves and undiscovered

oil resources in the offshore basin of the South China Sea at

28 billion barrels, while a Chinese estimate had it as high as

213 billion barrels. Another Chinese estimate calculated the natural

gas reserves in the South China Sea region at two quadrillion

cubic feet. These estimates are of considerable importance in

an era of high energy prices.

It was in the light of the importance, volatility and complexity

of the situation in the South China Sea that the ASEAN Studies

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 7 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

viii Preface

Centre of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) chose

that situation as the subject of its first online forum. The forum is

led off by an article by Michael Richardson, former Asia editor of

the International Herald Tribune and now Visiting Senior

Research Fellow at ISEAS. Valuably illustrated by maps, the

Richardson article focuses on the South China Sea’s potential as

a source of energy, the rise of China’s military power, and related

issues.

Sam Bateman, a Senior Fellow with the S. Rajaratnam School

of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University,

Singapore, where he serves on the Maritime Security Programme,

contributes a commentary on the Richardson paper. A former

Australian naval officer with a special interest in the political and

strategic aspects of the international law of the sea, Bateman has

co-edited with Ralf Emmers, Associate Professor at RSIS, Security

and International Politics in the South China Sea: Towards a

Cooperative Management Regime (Routledge 2009).

B.A. Hamzah, Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Ocean and

Earth Sciences (IOES) and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences,

University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, also contributes a commentary.

Previously with the Maritime Institute of Malaysia and the Institute

of Strategic and International Studies of Malaysia, Hamzah can be

reached at bahamzah@pd.jaring.my and 601-2366-9913.

An op-ed piece by K. Kesavapany, Director of ISEAS and a

former senior diplomat of Singapore, in the Straits Times of

Singapore, entitled “Flashpoint: South China Sea”, forms part of

the online forum. So does an article by Mark Valencia, a Visiting

Senior Fellow at the Maritime Institute of Malaysia and a Senior

Associate at the Nautilus Institute. Rodolfo C. Severino, Head of

the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS, contributes a clarification of

the new Philippine baselines law. Needless to say, all of them

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 8 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

Preface ix

express their personal views and not necessarily those of their

institutions.

The contributions to the online forum are printed in this

booklet, which is part of the Report Series of the ASEAN Studies

Centre.

Rodolfo C. Severino

Head, ASEAN Studies Centre

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies

Singapore

00 Energy_Geopolitics Prelims 9 9/28/09, 12:44 PM

ENERGY AND GEOPOLITICS IN

THE SOUTH CHINA SEA:

IMPLICATIONS FOR ASEAN AND ITS

DIALOGUE PARTNERS

Michael Richardson

Visiting Senior Research Fellow

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), Singapore

April 2009

The Setting

China says it wants close, cordial and cooperative relations with

its neighbours in Southeast Asia, the ten member states of ASEAN.1

Progress in this direction has gained impressive momentum since

the end of the Cold War and Chinese support for communist-led

insurgencies seeking to overthrow established governments in

the region.

However, China’s military power is growing steadily and it

claims ownership of a network of widely-scattered islands and

their surrounding waters and resources in the South China Sea,

one of the world’s largest semi-enclosed bodies of water. (See

Map 1.) These claims overlap in a substantial way with those of at

least three ASEAN countries, Vietnam, the Philippines and

Malaysia.

The three million square kilometre South China Sea is the

maritime heart of Southeast Asia. It is two-thirds the size of the

combined land territory of all the ASEAN states. Most Southeast

01 Energy_Geopolitics 1 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

2 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

MAP 1

Southeast Asia

Philippine

.SeJ

.....

-=·

--

lndi.ltl 0 c e :ut

Sc.alc- I:J2.000.000 olC S..ti

Source: U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook 2008 online.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 2 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 3

Asian countries have coastlines overlooking or close to the South

China Sea. Some would be wary about having to share a common

maritime boundary with such a big and increasingly powerful

nation as China, or even having it as a very close neighbour.

Meanwhile, oil and gas reserves under the seabed of the

South China Sea are being discovered and exploited further and

further from shore, as advances in drilling and production

technology enable coastal states and the energy companies

working for them to tap hydrocarbons in ever deeper waters.

(See Map 2.)

If China does not yet have the military capability to enforce

its claims in the South China Sea, it is expected to gain this

strength in the next few years. This puts a dark shadow of

uncertainty over the future of China’s relations not just with

ASEAN members, but also with their main dialogue partners,

including the United States, Japan, India, South Korea and

Australia. All of these countries have important links with China.

They also have significant strategic and commercial interests in

the South China Sea and in ASEAN.2

Maritime Disputes

Among Southeast Asian states, Beijing’s claims to the Spratly

Islands in the South China Sea are disputed by Vietnam, the

Philippines and Malaysia. (See Map 3.) Brunei in 1984 established

an exclusive fishing zone that encompasses Louisa Reef in the

southern Spratly Islands but has not publicly claimed the reef.

About forty-five of the islands are occupied by relatively small

numbers of military personnel from China, Vietnam, the

Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan.

The Spratlys form a widely-scattered archipelago of more

than 100 small islands, coral cays and reefs that lie to the east of

01 Energy_Geopolitics 3 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

4 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

MAP 2

Competing Claims in the South China Sea

._ -....-

...

Oil and Gas Resoutces

... ............

,...........,

M itl . . ~ ..... .,....,...,OoN.r...,

___ __

I/III/IV~ flillt.'l tll._ wt~~~

llt .......... lallllll._ t ............ ..._

......,......_dllillll ....

·----

-·-·---

·~..._

e..w.. .. ......,..., ................ .....

....

South ChiiUI Sea Malltlme Claims

- Lhl . . . . ll'lowl't M arr..IIIIPI

- - --~Cilia

Other South China Sea Claims

--

__ .......,. .......

~ l:ldiiM~ . . i!it

~--.,.'""""

0

-- ·~

South

China

Sea

Source: CIA Maps and Publications for the public.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 4 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 5

MAP 3

Competing Claims in the South China Sea

Countries Claiming

Ownership

• China

• VN!tnam

• Malaysia

• taiwan

Philippines

0 Gas/ Oil fields 500

Source: <www.southchinasea.org>.

busy international sealanes in the South China Sea. (See Maps 4

and 5.) The sealanes running through it connect the Straits of

Malacca and Singapore in Southeast Asia with China, Japan and

South Korea, the main oil-importing industrial economies in

Northeast Asia. These sealanes carry a large part of the world’s

maritime trade and are frequently used by leading navies, especially

the United States and increasingly by China. Located about two-

01 Energy_Geopolitics 5 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

6 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

MAP 4

South China Sea Islands

.._

·~·

INDONEStA

..__

=:....":"..:.:-... -

Source: Wikipedia commons.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 6 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 7

MAP 5

Spratly Islands

NOrlheMI CBy

Southwest <;ay~

South

China

Sea

Fi9ry cross •.

. Reef'

...

a d

•

~

Pigeon Reef Half

Moon

Aliso~ '

....

· spratly Reef

Shoal

JsJand

) •

.,.,

'

•• 0 50- 100 l':rn

• 0 !50 100ml

Source: CIA World Factbook 2008 online.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 7 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

8 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

thirds of the way between southern Vietnam and the southern

Philippines, the Spratly archipelago covers an area of nearly

410,000 square kilometres of the central South China Sea.3

Although the total land area of the Spratlys is less than five

square kilometres, control of this remote but potentially important

real estate might be used to establish naval patrol and surveillance

bases. It could also be used to bolster claims to fisheries and

offshore oil and gas resources in a vast area of the South China

Sea. China, Taiwan and Vietnam claim all of the Spratlys,

surrounding waters and any resources they may contain. The

Philippines and Malaysia assert sovereignty over smaller portions

of the Spratlys closest to their shores. (See Map 3.)

The South China Sea claims of China, Taiwan and Vietnam

are far wider than those of other claimants. Vietnam asserts

sovereignty over the Paracel Islands (see Map 4) as well as the

Spratlys. The Paracels were seized by China from South

Vietnamese forces in 1974 in the closing stages of the Vietnam

War, when Hanoi and Beijing were supposed to be allies. Chinese

forces have since reinforced their garrison on the Paracels and

extended an airport runway there, strengthening their grip on

what is seen in Beijing as a strategic outpost southeast of China’s

Hainan Island and roughly one-third of the way between Vietnam

and the Philippines. There are 130 islands and rock outcrops in

the Paracels group.4

Vietnam asserts that both the Spratlys and the Paracels are

part of its national territory and have historically belonged to

Vietnam. In the 1930s, France annexed the Spratlys and Paracels

on behalf of its then-colony Vietnam. Hanoi treats the Spratlys as

an offshore district of the province of Khanh Hoa. Vietnam’s

claims beyond the Spratlys and Paracels cover an extensive area

of the South China Sea, although they are not clearly defined.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 8 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 9

Both China and Vietnam protested in February 2009 after the

Philippines passed new legislation spelling out its claims to some

of the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal.

China’s U-shaped Claim

However, China’s claim appears to be far wider, encompassing

much of the South China Sea. The precise limits are not clear

from the broken U-shaped line drawn on official Chinese maps.

(See Map 4 for the approximate location of this line.) Still, this

claim, if acknowledged by ASEAN countries or enforced by Beijing,

would bring China into the maritime heart of Southeast Asia. It

would make China a next-door neighbour not just of Vietnam, but

also of the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia (through

its Natuna Island in the southern section of the South China Sea).

Moreover, this U-shaped line seems to coincide with the

extension into the South China Sea of the so-called “first island

chain” extending from the southern tip of Japan through Okinawa

and the ocean east of Taiwan to the Northern Philippines and

around the perimeter of the South China Sea. (See Map 6.) Chinese

military theorists say the first island chain forms a geographic

basis for China’s maritime defensive perimeter. It is the inner of

two such barriers, the second and outermost of which extends

southeast from Japan to and beyond the U.S. island territory of

Guam in the western Pacific Ocean.5

China’s Growing Military Power

Taiwan maintains a claim in the South China Sea similar to Beijing’s

U-shaped line. But neither Vietnam nor Taiwan has the military

might to enforce its claims and evict other claimants. Only China

has, or will have, that power if its military modernization

programme continues at, or close to, its pace of recent years.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 9 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

10 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

MAP 6

The First and Second Island Chains

Source: U.S. Department of Defence, Annual Report to Congress: Military

Power of the People’s Republic of China, 2007.

China’s annual military spending has grown four-fold or more

over the last decade, rising from 0.9 per cent of GDP to at least

1.5 per cent, or US$58 billion. By some assessments, China’s real

military spending may be several times the published figure when

off-budget items relating to defence are included. Even without

01 Energy_Geopolitics 10 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 11

allowing for this, China’s declared spending on military

modernization overtook India’s in 2002 and Japan’s in 2008. While

Chinese land forces are being upgraded, maritime and air forces

(and thus power projection) are modernizing faster. Meanwhile,

defence budgets in Southeast Asia, including those of the region’s

Spratly claimants, are small by comparison with those of China

and elsewhere in Asia.6

China’s navy has around 860 vessels. Some are old, small and

able to operate only in “brown water” close to the coast. But the

navy has “blue water” ambitions. It is extending its reach and

capability to protect China’s offshore interests, including those in

the South China Sea and beyond. Since 2000, China has built at

least 60 warships. According to the U.S. Defence Department,

China already has the largest force of principal combatants,

submarines and amphibious warfare ships in Asia. Its navy has

29 destroyers, 45 frigates, 26 tank landing ships, 28 medium landing

ships, 54 diesel attack submarines, five nuclear attack submarines

and 45 missile-armed coastal patrol craft. Of these 232 vessels,

168 are in China’s East and South Sea Fleets.7

In November 2008, a senior Chinese military spokesperson

indicated that the next major addition to the navy will be several

aircraft carriers built in China, although analysts doubt that the

first will be in service before 2015.8 China’s ability and readiness

to use naval power to protect trade and other interests far from its

shores were underscored by Beijing’s decision in December 2008

to send two of its most advanced warships and a supply vessel

from its naval base near Sanya, on Hainan Island, through the

South China Sea and the Straits of Malacca and Singapore into the

Indian Ocean to protect Chinese ships from pirate attack in

the Red Sea off lawless Somalia. The flotilla was ordered to guard

convoys and deter piracy for at least three months, before possible

replacement by another squadron of Chinese navy ships.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 11 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

12 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

China’s Milplex

China’s military-industrial complex, the biggest in Asia, is also

improving both the quantity and quality of production. China is

one of the few countries in the world to produce a full range of

military equipment, from small arms to surface ships, submarines,

and jet fighters as well as ballistic and cruise missiles and nuclear

weapons. Since 2000, China has been producing several new types

of weapons that are highly competitive in terms of quality and

capability, among them the Song-class diesel-electric submarines

and the Type-052C destroyer equipped with an indigenous Aegis-

type radar and air-defence system.

One consequence of this growing self-sufficiency in arms

acquisition could be the rise of a more technologically-advanced

China that would be increasingly prone to challenge the United

States for regional, even global, predominance. Another

consequence of a militarily self-confident China could be a more

assertive policy in a number of areas — in the Taiwan Strait, in the

South China Sea and in the “blue waters”, of the Pacific and

Indian oceans — that would upset regional security.9

Still, the U.S. intelligence community estimates that China

will take until the end of this decade or longer to produce a

modern force capable of defeating a moderate-size adversary, and

that it will not be able to project and sustain even small military

units far beyond China before 2015.10

If this assessment is correct, there is still time to enmesh

China more fully into a regional relations system based on

international law, non-use of force and negotiated settlement of

disputes. Indeed since 1998, China has settled at least eleven

territorial disputes with six of its neighbours, among them Russia,

Vietnam and Japan. The most recent was the completion of the

land border delimitation treaty with Vietnam in December 2008.11

01 Energy_Geopolitics 12 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 13

China’s policy since 1975 has been to “shelve” the conflicting

sovereignty claims to the land features and waters of the South

China Sea and, in the meantime, undertake cooperative activities

in the area.12 ASEAN formalized a similar approach to resolving

these maritime disputes peacefully when it issued a Declaration

on the South China Sea in 1992.13

However, many of the disputes in the South China Sea involve

more than two countries and sometimes as many as five

contestants. The plurilateral nature of the claims and the sensitive

national interests that are at stake make solutions complex and

difficult to reach. Moreover, China calls for joint development

only in the areas in which Beijing has overlapping claims with

Southeast Asian countries, and where they assert legal jurisdiction

and have established authority, such as in the Spratlys or zones on

the continental shelf southeast of Vietnam. China refuses to

countenance joint development in the Paracels, which are already

under Chinese control. Some Vietnamese scholars refer to this as

the “yours is ours, ours is mine” principle.

What do China’s Maritime Claims Portend?

China’s U-shaped claim in the South China Sea is the source of

considerable controversy, even among Chinese analysts. The “nine-

dotted line”, so called since it is composed of nine dashes, has

been on official Chinese maps dating back to 1947, when the

Kuomintang (KMT) ruled China. After the KMT was defeated in

1949 by communist forces and its remnants fled to Taiwan, the

new government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) adopted

the same U-shaped claim in the South China Sea and Chinese

maps published since 1953 have displayed the nine-dotted line.14

The dotted line encloses the main islands, atolls and rock

outcrops of the South China Sea: the Pratas Islands in the far

01 Energy_Geopolitics 13 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

14 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

north, the Macclesfield Bank roughly mid-way between Vietnam

and the northern Philippines, and also the Paracels and Spratlys.

(See Map 4.) At its full extent, the Chinese claim covers about

80 per cent of the South China Sea.

China asserts sovereignty over all the islands and their

adjacent waters, based on prior discovery, occupation and use

stretching back through centuries of history. But does the

contemporary Chinese claim mean that Beijing is asserting

sovereignty over all the waters within the dotted line? Does it

mean that Beijing regards them as internal waters or territorial

sea, and that the line is viewed as China’s maritime boundary in

the area, even though it is not defined by any coordinates?

The PRC’s 1998 law on its Exclusive Economic Zone and

Continental Shelf states that the legislation will not affect the

state’s “claim of historic rights”. This suggests that China may

maintain its claim to historic rights and waters within the dotted

line of the South China Sea. However, it may also indicate that

China no longer regards the waters within the line as historic

waters, because historic waters can only be treated as internal

waters or territorial seas. They cannot be included in exclusive

economic zones and continental shelves, as defined by the 1982

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS),

which China ratified in 1996.15

Hasjim Djalal, who has served as President of the International

Seabed Authority and as Indonesia’s Ambassador-at-Large for the

Law of the Sea and Maritime Affairs, says it is presumed that what

China claimed, at least originally, was limited to the islands, rocks,

and perhaps the reefs, but not the whole sea area enclosed by the

nine-dotted line, which has no coordinates. He argues that it is

inconceivable that in 1947, when general international law still

recognized only a three-mile territorial sea limit, that China would

01 Energy_Geopolitics 14 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 15

claim the entire South China Sea. He says that a careful reading of

recent Chinese law strengthens this assumption, despite the fact

that some Chinese writing seems to imply that Beijing also claims

the “adjacent sea” of the islands and rocks within the dotted line.

However, “adjacent sea” is not clearly defined and the concept

does not occur in UNCLOS, which China has ratified.

UNCLOS deals only with internal waters, archipelagic waters,

territorial seas, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones,

continental shelves and high seas. Moreover, UNCLOS stipulates

that the measurements of those waters or zones should start from

base points on land, or appropriate baselines connecting legitimate

points, and not by arbitrarily drawing them on the sea.16

Tug-of-war at Sea

Why does the Chinese Government not clarify the situation? If

Beijing abandoned its U-shaped dotted line claim to a vast area of

the South China Sea, its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) would

extend to a maximum 200 nautical miles from southern points of

Hainan Island. If China’s jurisdiction over the Paracels were

recognized, its EEZ would stretch further south. UNCLOS allows

pieces of land at sea to be defined as islands on two conditions.

First, if they are “a naturally formed area of land … which is

above water at high tide”. And second, if they are capable of

sustaining human habitation or economic life. Under international

law, only natural islands can generate a legitimate EEZ and

continental shelf claim. Of the Spratly Islands, perhaps only Itu

Aba (Taiping Dao) would meet the definition of being a natural

island. Itu Aba is occupied by Taiwan. It is the largest and one of

the most northerly islands in the Spratly archipelago. This would

significantly reduce the extent of China’s territorial and maritime

claims in the South China Sea.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 15 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

16 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

Retaining the U-shaped claim may also be intended by Beijing

to keep a negotiating card in hand and rival claimants in a state of

uncertainty. There have been several armed clashes and numerous

standoffs among contending claimants to the Spratlys in the past

couple of decades. The main encounters have embroiled China

and Vietnam. In 1988, they fought a brief naval battle near one of

the Spratly reefs. More than seventy Vietnamese sailors were

killed and several of their vessels sunk.

There have been repeated incidents since then, raising

nationalist sentiment on both sides. In December 2007, China

announced the elevation of Hainan Province’s Xisha (Paracel)

Islands department to a level officially named “Sansha City”, which

would have administrative jurisdiction over the Paracel and Spratly

Island groups and the submerged reefs of the Macclesfield Bank.

(See Map 4.) A PRC spokesperson said that China had “indisputable

sovereignty” and effective jurisdiction over the islands of the

South China Sea “and the adjacent waterways”.

In reaction to China’s declaration, hundreds of Vietnamese

protesters demonstrated outside the Chinese Embassy in Hanoi.17

A Vietnamese Foreign Ministry spokesman said that Hanoi objected

to China’s move to administer the three island groups, including

Vietnam’s Hoang Sa and Truong Sa archipelagos. “This action is a

violation of Vietnam’s sovereignty, (and is) not in line with the

common perception of high-ranking leaders of the two countries

or beneficial to the bilateral negotiation process of seeking

fundamental and long-term solutions to sea-related issues”, the

spokesman added.18

In the Spratlys, the armed garrisons that all the claimants,

except Brunei, have stationed on the tiny dots of land they say are

theirs are still in place. In some cases, they have been reinforced.

Vietnam reportedly occupies 21 of the Spratlys, the Philippines 8,

China 7, Malaysia 3 and Taiwan 1.19

01 Energy_Geopolitics 16 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 17

A code of conduct for the South China Sea, signed by Beijing

and ASEAN in 2002, is voluntary. The Declaration on the Conduct

of Parties in the South China Sea was signed by ASEAN member

states and China on 4 November 2002.20 Meanwhile, a joint seismic

survey of hydrocarbon resources, agreed by the national oil

companies of China, Vietnam and the Philippines in 2005, lapsed

in July 2008 and may not be renewed. Even when it was

operational, the tripartite seismic survey did not include other

Spratly Island claimants. Moreover, it covered only a small part of

the contested sea area.

Sino-Vietnamese Rapprochement?

In October 2008, China and Vietnam outlined new steps to resolve

their long-running territorial disputes in the South China Sea in an

effort to avert further conflict and put their relations on a steadier

footing for the future. Although both countries are ruled by

communist parties and share extensive land and sea borders, they

have had a tense relationship. But they now face political

challenges at home as their export-oriented economies and

investment slow under the impact of global financial turmoil and

deepening recession. They have evidently decided to give primacy

to strengthening bilateral party, trade and investment ties to offset

the wider economic downturn.

The latest measures to improve relations emerged during

the visit to China of Vietnam’s Prime Minister, Nguyen Tan Dung,

from 20–25 October 2008. It was his first official visit as prime

minister and came ahead of the Asia-Europe summit in Beijing.

Mr Dung held talks with his Chinese counterpart, Wen Jiabao,

and Chinese President Hu Jintao. A joint statement issued at the

end of the visit said the two sides believed that “to deepen the

bilateral all-round strategic cooperation partnership under

the current complicated international situation conforms to the

01 Energy_Geopolitics 17 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

18 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

fundamental interests of both countries, ruling parties and

peoples”.21

Under the plan, Chinese and Vietnamese companies will be

encouraged to form joint ventures and engage in large-scale

projects in infrastructure construction, chemicals, transport,

electricity supply and home building. The aim of these projects,

and the new road, rail and shipping connections, is to bond the

neighbouring provinces of southern China and northern Vietnam.

This would be part of a growing network of highways linking

China with Southeast Asia. In an attempt to boost bilateral trade

to a targeted US$25 billion by 2010 from US$16 billion in 2007,

there will be a joint crackdown on cross-border smuggling,

counterfeiting and swindling. The two sides also agreed to promote

investment in two international economic corridors. One links

their land border towns while the other involves China’s Guangxi,

Guangdong and Hainan Island provinces as well as Hong Kong

and Macau, and ten coastal areas of Vietnam.22

Whether this promised increase in two-way trade and

investment materializes remains to be seen. But the proposed

expansion of economic ties will also depend on progress in

managing and eventually settling festering territorial disputes

between China and Vietnam. Both sides reaffirmed that they would

complete demarcation of their 1,350-kilometre land border by the

end of 2008, a deadline that was set in 1999. As agreed, they

finished the work on time.

What was new in the joint statement was an agreement to

start joint surveys in disputed waters outside the mouth of

Beibu Bay (the Gulf of Tonkin) at an early date and a promise

jointly to exploit the demarcated zones for their fisheries and

oil and gas potential. 23 Vietnamese analysts say that the

disputed waters referred to are a small area that immediately

01 Energy_Geopolitics 18 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 19

connects to the mouth of the Gulf of Tonkin and that it is not

a reference to the wider South China Sea dispute. They add

that resolving disagreements in this area is perhaps among

the easiest of the territorial disputes that Vietnam faces in the

South China Sea.

South China Sea Stakes

The most contentious and difficult territorial issues in the

relationship between China and Vietnam are their conflicting

claims to the Paracel and Spratly Islands. In their 25 October joint

statement, China and Vietnam agreed to find a “basic and lasting”

solution to the South China Sea issue that would be mutually

acceptable. No detail was offered on how such a resolution might

be reached. But, significantly, they said it would be in accordance

with UNCLOS, the law of the sea treaty. Meanwhile, they would

observe the ASEAN-China code of conduct in the South China

Sea and refrain from any action that would complicate or escalate

disputes. They would also consult on finding a proper area and

way for joint petroleum exploration.

On the principle of starting with the easier steps, they agreed

to collaborate on oceanic research, environmental protection,

weather forecasting, and information exchanges between the two

armed forces.24 A strategic cooperation pact between state-run

China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and its

Vietnamese counterpart, PetroVietnam, is also reported to have

been signed during Dung’s visit to China.

Together, these accords would be important mutual-restraint

and confidence-building measures, provided their terms are strictly

and consistently observed by both sides — something that has

not been a feature of past agreements between China and Vietnam

on the South China Sea.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 19 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

20 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

Changed Circumstances

However, several things may be different this time, apart from the

desire to build bilateral economic ties to cushion both countries

from global trouble. Beijing may want to defuse widespread

concern in Asia over its growing military power and the fear that

military muscle will be used to enforce territorial and maritime

boundary claims that China has in dispute with many of its

neighbours, stretching from Japan through Southeast Asia to India.

In this context, the South China Sea is a sensitive touchstone.

In October 2008, not long before the Vietnamese prime

minister arrived in Beijing, China banned its fishing fleet, one of

the biggest in the world, from operating in waters contested with

neighbouring countries. Fishing disputes in recent years have not

only pitted China against Vietnam. They have also become an

irritant in relations with North and South Korea, Japan, the

Philippines and Indonesia. In the South China Sea, Chinese

fishermen have been detained by the Philippines, allegedly for

illegal fishing in waters claimed by Manila close to the Spratly

Islands. Similar incidents have been reported in Vietnam. China’s

cabinet, the State Council, issued a directive for the coast guard

and fishery authorities to stop Chinese fishing vessels from entering

“key sensitive maritime areas”.25

Another new factor is the recent steep fall in the price of oil

and natural gas. This has removed some of the incentive for

petroleum companies to explore in ever deeper waters, further

and further from shore in the South China Sea. Deepsea drilling

is very expensive. But when the oil price surged past US$100 a

barrel for the first time at the start of 2008 and peaked at just over

US$147 a barrel in July, the expense seemed fully warranted.

Around that time, China told the U.S.-based oil giant

ExxonMobil to cancel planned oil exploration ventures off the

01 Energy_Geopolitics 20 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 21

coast of Vietnam with PetroVietnam, implying that if it did not do

so it could be barred from operating in China. A Chinese Foreign

Ministry spokesman said China opposed any act “violating China’s

territorial sovereignty, sovereignty rights or administrative rights

in the South China Sea”.26

Following a similar warning from Beijing, BP halted plans in

2007 to carry out exploration work with PetroVietnam off southern

Vietnam, citing territorial tensions. This was also in an exploration

block approved by Vietnam, but contested by China, about

370 kilometres offshore, at the outer edge of Vietnam’s Exclusive

Economic Zone between Vietnam and the Spratly Islands.

With the oil price falling below US$40 a barrel by February

2009 as slowing global growth crimped demand, the race for

offshore hydrocarbon resources in the South China Sea had lost

some of its impetus. This has provided a political respite, allowing

China and Vietnam to pursue more conciliatory measures.

Energy Resources Cockpit

What could upset the fragile equilibrium in the South China Sea

and resurrect emotive issues of national sovereignty, prestige and

pride? The biggest risk is that economic recovery, rapid growth

and a resurgence of strong demand for energy in Asia will again

push China and its Southeast Asian neighbours into contention.

China’s oil and gas production has been failing to keep pace

with surging consumption and it is worried that existing reserves

will not last much longer. These concerns are shared by other

petroleum producers in the South China Sea, among them Vietnam,

Malaysia and Indonesia. They are currently net exporters of oil or

gas or both, but can see the time approaching when their energy

reserves will be insufficient to meet domestic demand. They want

to extend the life of their reserves by finding more oil and gas. As

01 Energy_Geopolitics 21 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

22 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

in China, this is an energy security imperative and an economic

growth imperative, because oil and gas are vital for transport and

industry. Meanwhile, the Philippines, a net importer of both oil

and gas, urgently needs to find more fossil fuel and regards its

offshore zones in the South China Sea as a key to greater self-

sufficiency in future.27

For the Chinese Government, energy policy has become an

arm of foreign policy. From being a net exporter of oil in 1993,

China today relies on foreign supplies for about half the oil it

uses. It is also becoming a major gas importer. For reasons of

energy security, China has placed a high priority on getting as

much of its future oil and gas as it can from within its land

territory, from offshore zones, or as close to home as possible,

including Russia and Central Asia. At present, around 75 per cent

of China’s oil imports come from politically volatile areas of the

Middle East and Africa.28 They have to be shipped to China through

distant sealanes, which the Chinese armed forces do not yet have

the means to protect. These maritime arteries of energy supply

could be cut in a crisis.

NOCs Versus IOCs

It is not only countries that are under pressure to increase their

oil and gas reserves at a time of perceived looming scarcity and

high prices. So are major energy companies, whether they are

state-controlled or majority owned by private sector interests. In

the past few decades, national oil companies (NOCs) have emerged

to challenge the dominance of international oil companies (IOCs).

The NOCs are partially or wholly state-owned firms, through

which governments control access to reserves of oil and gas and

retain profits from production.29

Today, these national champions in Asia, the Middle East,

Africa and Russia control much of the world’s oil and gas. Thirty

01 Energy_Geopolitics 22 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 23

years ago, the big international oil companies lorded over 75 per

cent of global reserves and 80 per cent of output. Now they

control about 6 per cent of oil reserves and 25 per cent of

production.30

Western energy giants, including ExxonMobil and BP, are

struggling to secure shares of new finds of oil and gas to boost

their reserves. ExxonMobil’s reserves-to-production ratio is just

over fourteen years and falling, while BP’s is twelve years and flat.

The IOCs need access to reserves they can “book” with the

Securities and Exchange Commission, the U.S. stock market

regulator. Only then can investors measure the health and

attractiveness of integrated energy companies that explore for,

produce, process and market oil, gas and related products.31

Meanwhile, leading international petroleum service firms are

helping national oil companies break their dependence on Western

energy majors by providing seismic survey, drilling, training and a

wide range of other skills and technology to both NOCs and

smaller listed firms, the so-called independents, as they move to

tap onshore and offshore resources.32

Deepwater Drilling

Advances in know-how and equipment are enabling NOCs, IOCs

and independents to explore and exploit what they find further

and further from land in ever deeper waters, although it remains

a very high-risk, high-cost business. Dozens of new drill ships and

rigs are being built to explore for oil and gas in the deepwaters of

places like the Gulf of Mexico, West Africa, Brazil, Australia, New

Zealand, India and the South China Sea.

In the next three years, ODS Petrodata, which tracks drilling

rigs and other industry equipment, expects 160 new offshore rigs

to enter service. Seventy-five of these rigs will be for ultra-

deepwater drilling. They can operate in waters up to 4,000 metres

01 Energy_Geopolitics 23 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

24 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

deep and have a total drilling depth of as much as 13,000 metres.

Assuming enough engineers and drill crews can be found to operate

them successfully and safely, their arrival may reduce sky-high

charter rates for ultra-deepwater rigs. At the height of the oil price

boom in the first half of 2008, owners of these rigs were able to

charge as much as US$600,000 per day.33

The global credit crisis and recession will crimp deepwater

drilling for a while. But as the world economy recovers, demand

for oil and gas will revive and, when it does so, the rush to explore

for and produce hydrocarbons from beneath the seabed in ever

deeper waters will resume.

Among hydrocarbon explorers, deepwater drilling is usually

considered to mean working in depths of 800 metres or more.

Ultra-deep drilling starts at around 2,500 metres. Oceans and seas

cover just over 70 per cent of the surface of the Earth, and nearly

half of the world’s marine waters are over 3,000 metres deep. This

is a new frontier for the discovery and exploitation of oil, gas,

minerals and other valuable resources. The drill ships and rigs

being built in South Korea, Singapore, China and other parts of

the world that are capable of tapping into oil and gas reserves at

such depths are helping to reshape the global petroleum business.

The amount of oil pumped from deepwater fields will nearly

double between 2005 and 2010 to about 11 million barrels a day,

or about one eighth of estimated daily consumption in 2008,

according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The

consulting firm, Cambridge Energy Research Associates, offers a

slightly different but still bullish forecast. It says that deepwater

wells produced about 2 million barrels of oil a day in 2000, but are

expected to yield over 10 million barrels a day by 2015. Another

consulting firm, Douglas-Westwood, says capital spending on

deepwater oil and gas will rise US$25 billion annually by 2012,

nearly double the figure for 2003.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 24 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 25

Enter CNOOC, Husky and Other Explorers

In December 2008, the Chinese Government approved a

programme by the state-owned China National Offshore Oil

Corporation (CNOOC) to spend 200 billion yuan (US$29.2 billion)

with partners to expand oil and gas exploration in the South

China Sea over the next ten to twenty years, starting in 2009. Of

course, the programme could be slowed or scaled back by the

recession and low oil and gas prices. CNOOC, the country’s third-

largest oil producer, said in November 2008 that it aimed to increase

hydrocarbon output in the South China Sea to 50 million tonnes

per year (1 million barrels per day), equivalent to the current

production of China’s biggest onshore oil field at Daqing.34 CNOOC

said it would focus on deepwater and ultra-deepwater oil-gas

exploration in water depths of between 1,500 and 3,000 metres.35

CNOOC says it already has 3.1 billion tonnes of oil equivalent in

proven reserves in its deepwater zone in the South China Sea.36

CNOOC announced in July 2008 that it was buying a

Norwegian oil exploration contractor, Awilco Offshore ASA, for

US$2.52 billion, so that it could reach depths of up to 1,500

metres. Awilco owns and operates deepwater drilling platforms

and equipment. At present, CNOOC itself is unable to drill in

depths of over 300 metres.37 CNOOC has also placed an order for

deepsea drilling rigs with a Norwegian supplier.

One of the independent oil companies that work with CNOOC,

Canada’s Husky Energy Inc., moved a new deepwater drilling rig

built in South Korea into the South China Sea in November 2008

on a three-year contract. It is delineating and evaluating a giant

gas field which Husky and CNOOC Ltd, the listed arm of the state-

owned parent company, announced they had found in June 2006

in the northern sector of the South China Sea.38

Husky, controlled by Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing, who

has close ties to China, said the Liwan field could contain up to

01 Energy_Geopolitics 25 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

26 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

6 trillion cubic feet of recoverable resources, adding around 7 per

cent to China’s total gas reserves. Significantly, it was China’s first

deepwater petroleum discovery. The exploration well was drilled

250 kilometres south of Hong Kong at a depth of 1,500 metres.

Husky announced in late February 2009 that it would soon

begin developing the Liwan field, 350 kilometres southeast of

Hong Kong, after the first of two appraisal wells confirmed a

major gas discovery. The flow rate from the 55-square kilometre

reservoir indicated that it could produce gas at a rate of over 150

million cubic metres per day. Under its production-sharing

agreement with Husky, CNOOC has the right to participate in

development of the field by taking a stake of up to 51 per cent.

Apart from Liwan, Husky has five other exploration blocks in the

South China Sea. The gas discovery in mid-2006 sparked a burst

of interest in the surrounding deepwater zone of the South China

Sea, with other independent energy companies including BG

Group, Devon Energy Group and Anadarko Petroleum Corp.,

preparing to drill in adjacent blocks.

South China Sea Bathymetry

The seabed area of the South China Sea consists of about one

million square kilometres of continental shelf that is less than 200

metres below the sea surface, and about two million square

kilometres of continental shelf deeper than 200 metres. The

shallower part of the seabed, known as the Sunda Shelf, is mainly

located in the western and southern zones of the South China Sea.

The deeper part, known as the South China Sea Basin, is in the

eastern and northeastern zones. In some areas, the water depth is

over 5,000 metres. This deeper basin is punctured by the outcrops

of the Spratly Islands. Much of this zone is now within reach of

deepwater and ultra-deepwater drilling vessels.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 26 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 27

Methane Hydrates

It is not just the search for conventional oil and gas that is driving

energy companies further and further offshore into deeper and

deeper waters. China announced in 2007 that it had for the first

time managed to tap into seabed sediment containing gas hydrates

in the northern part of the South China Sea. Zhang Hongtao,

Deputy Director-General of the China Geological Survey, a

government agency, said that by collecting the gas hydrate samples

in May 2007, China had become the fourth country after the

United States, Japan and India to achieve this technological

breakthrough.

Some scientists have said that the huge quantities of methane-

rich hydrates kept stable by low temperature and high pressure

on the seafloor or below the Arctic could become an important

fuel for the future. Methane is the main component of natural gas.

Every cubic metre of gas hydrate, which is a solid crystalline

structure in its natural state, releases as much as 160 cubic metres

of gas.

Zhang was quoted as saying that initial estimates indicated

that the potential volume of gas hydrates on the continental

shelf in the area of the South China Sea tapped by China was

equivalent to more than 100 million metric tonnes of oil

(2 million barrels of oil per day) — about one quarter of China’s

oil consumption of 7.8 million bpd in 2007. However, he added

that because it was difficult to produce a continuous gas flow

from hydrates, China might not be in position to develop the

resource for many more years.

However, China is clearly in a race with Japan, the United

States, South Korea, India and perhaps other countries to try to

master the technology needed to exploit a potentially important

offshore energy source for the future.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 27 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

28 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

Asia’s Rising Gas Demand

Meanwhile, China, the world’s second-largest energy consumer

after the United States, wants to increase its gas consumption to

reduce heavy reliance on coal, which causes serious air pollution.

Southeast Asian countries are also turning to cleaner-burning gas

in a big way to generate electricity, and for industrial and home

use. Natural gas use among Asian countries is forecast to rise by

about 4.5 per cent annually on average until 2025 — faster than

any other fuel — with almost half of the increase coming from

China. If this growth rate is maintained, Asian demand will exceed

21 trillion cubic feet, nearly triple current consumption, by 2025.

The South China Sea is considered to have greater gas than

oil potential. Most of the hydrocarbon fields explored in the South

China Sea areas of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines

and Vietnam, as well as China, contain gas, not oil. Estimates by

the U.S. Geological Survey indicate that between 60 per cent and

70 per cent of the region’s hydrocarbon resources is gas. Even so,

a significant proportion of the more than 6 million barrels of oil

per day produced by China and Southeast Asian countries comes

from the South China Sea region. A bigger proportion of the

region’s gas output of over 8 billion cubic feet per day comes from

the South China Sea basin, although no precise figures are

available. Chinese estimates of the overall oil and gas potential of

the South China Sea tend to be much higher than those of non-

Chinese analysts.39

The most bullish of the Chinese estimates suggest potential

oil resources as high as 213 billion barrels of oil, nearly fourteen

times China’s proven oil reserves of 15.5 billion barrels at the

end of 2007. For gas, the potential production level is put by the

most optimistic Chinese estimates at over 2,000 trillion cubic feet,

although only about half of this might be recoverable, even if

01 Energy_Geopolitics 28 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 29

fields on this scale were found. China’s proven gas reserves at the

end of 2007 were 67 trillion cubic feet.40

China’s Southward Thrust

China’s emergence as an increasingly big gas consumer and the

emphasis it puts on getting as much of its future oil and gas from

as close to home as possible, may help explain why China rates

the energy potential of the South China Sea so highly. Such

estimates buttress its sweeping claims to sovereignty in the

area. Of course, these estimates have yet to be tested. Much of

the area, particularly in deepwaters, is unexplored because it is

remote and contested.

However, China seems intent on expanding its offshore

energy search. Until a few years ago, the state-owned Chinese

energy giants were discouraged from competing and CNOOC

had a virtual monopoly on offshore work. This has changed and

now all of the Chinese oil and gas majors can bid for onshore

and offshore projects, both local and foreign. PetroChina — an

arm of China’s biggest oil producer, China National Petroleum

Corporation — announced in March 2006 that it would be turning

its attention to the southern sector of the South China Sea in the

next few years.

As Southeast Asian governments and the energy companies

working for them push deeper into the South China Sea in their

hunt for more gas and oil, they can only hope that China’s

southward push will lead to better cooperation, not confrontation.

China has handed out exploration contracts or production licences

over most of its deepwater oil and gas blocks in the South China

Sea south of Hong Kong. These are contested only by Taiwan.

However, future Chinese permits seem set to overlap with

those from its Southeast Asian neighbours.41 Unlike in the 1980s

01 Energy_Geopolitics 29 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

30 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

or 1990s, China may soon have the military power to enforce its

territorial claims against rivals in the region, should it decide to

do so. But at what cost to its international reputation, to stability

in the maritime heart of Southeast Asia and to its relations with

ASEAN?

China seems to be confronting ExxonMobil, the world’s

largest publicly traded oil company by market capitalization,

and BP, the third biggest oil firm by sales, with the choice of

pursuing their offshore plans in Vietnam or jeopardizing their

already substantial investments in China, potentially the world’s

biggest energy market. China, of course, would argue that it is

Vietnam which should exercise restraint. How will Vietnam react

if Chinese pressure again stops Western oil and gas majors from

going ahead with planned projects off the South China Sea coast

of southern Vietnam?

The United States and Japan

More important, how will the United States and its main Asian

ally, Japan, react when they see hard evidence of Beijing’s

southward extension of its offshore power projection into areas

of the South China Sea over which it claims sovereignty, a claim

that it has so far been unable to enforce? About a quarter of the

world’s trade and around 20 per cent of its daily oil consumption

are shipped through Southeast Asian straits and the South

China Sea.

Japan, which is entirely dependent on imported oil and gas,

gets over 80 per cent of its supplies via the South China Sea. South

Korea, another Northeast Asian ally of the United States and a

major energy importer, is also heavily reliant on shipments through

the South China Sea. Taiwan, too, depends on South China Sea

shipping routes for most of its energy imports.

01 Energy_Geopolitics 30 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

Implications for ASEAN and Its Dialogue Partners 31

The United States puts a high strategic priority on support

for its Asia-Pacific allies and also on maintaining freedom of

navigation around the world. America regularly sends warships,

including aircraft carriers, from its Pacific fleet through the South

China Sea, and the Malacca and Singapore Straits, to reinforce its

military presence in the Arabian Sea and Persian Gulf. This naval

“surge” capacity from the Pacific to the Indian Ocean is especially

important to Washington at times of crisis in the Gulf or Indian

Ocean region. If the world economy recovers and an era of

perceived petroleum scarcity and high prices returns, the United

States and Western nations will be under pressure to protect the

interests of their leading energy companies in any confrontation

with China in the South China Sea.

What Next from China

Beijing is likely to keep restating its sovereignty claims in the

South China Sea whenever it feels they are under challenge.

However, although China is building its own deepwater drilling

rigs, the first is not due to be delivered before 2010. Chinese

NOCs have limited experience in deepsea oil and gas exploration,

let alone production from such a challenging environment. They

will continue for quite a few more years to depend on the small

group of energy companies that have the necessary know-how

and equipment to work in deep waters in remote and stormy

locations. CNOOC says it can hire service companies to do the

work. But first China must persuade more energy firms that the

South China Sea is an attractive alternative to the world’s hottest

deepsea frontiers, among them the Gulf of Mexico and the

Atlantic Ocean off Brazil and West Africa, which account for

nearly 75 per cent of global deepwater expenditure by energy

companies.42 Energy firms are unlikely to go to the expense of

01 Energy_Geopolitics 31 9/28/09, 12:47 PM

32 Energy and Geopolitics in the South China Sea

working in deepwater areas of the South China Sea unless they

are assured of a peaceful environment.

Meanwhile, Beijing has held out an olive branch to its

neighbours by publicly declaring on many occasions its preference

for joint development of energy resources in contested offshore