Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kristjansson PESGB 2007

Kristjansson PESGB 2007

Uploaded by

paulspeakingOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kristjansson PESGB 2007

Kristjansson PESGB 2007

Uploaded by

paulspeakingCopyright:

Available Formats

Self-Esteem, Self-Confidence and Individualised Education

Kristjan Kristjansson 1. Introduction When young children enter school for the first time, most of them do so with a healthy mixture of anticipation, excitement and enthusiasm. For many young people approaching secondary-school age, however, the excitement has ebbed and the enthusiasm has dwindled. For some students, adolescence becomes a time of educational underachievement and disengagement from school work; at worst it is a time of psycho-social alienation, culminating in risky delinquent behaviour. There is a wide array of possible contributing factors: biological (teenage hormones make mischief in many a young life), personal (many youngsters have already had their fair share of lifes vicissitudes), social (self-conceptions and social expectations differ markedly among cultures) and educational (levels of educational attainment and student satisfaction seem to depend considerably upon individual schools and even upon individual teachers). Given this variety, it beggars belief that anyone would have thought that the teenage malaise could be ascribed to a single cause. Yet in the 1980s and 1990s, the magic words lack of selfesteem became an all-purpose explanation not only for that alleged malaise but for myriad other evils as well. Conversely, boosting self-esteem became the first business of teachers and pedagogues. In the wake of harsh criticisms urged against the self-esteem movement in recent years, the pendulum has swung radically. Although some media pundits and populists continue to man the barricades of self-esteem witness Oprah Winfrey, whose shows still contain copious references to peoples destructive self-disesteem the movement has, to all intents and purposes, struck its flag in academic circles. How long that news will take to percolate through to practitioners and the general public is another story. In any case, I review the rise and demise of the self-esteem movement within the fields of psychology and education in broad outline in Section 2. As this Titanic of educational fads (Stout, 2000, p. 274) sinks, some searching questions beckon educators. First, we should ask if and how the self-esteem myth has infiltrated general educational approaches of late; and, if it has, to what extent such approaches can be decontaminated and resuscitated. In Section 3, I focus on the ideas behind individualised education from precisely that perspective. Second, we need to ask what should happen, after the implosion of self-esteem, to the powerful and pervasive intuition that students self-concept has significant bearing on their educational achievement and general wellbeing. The most unyielding response would be to dispose of this intuition altogether. However, in shunning one kind of vice, we must be careful not to run to the opposite extreme. To hold fast to the belief that students self-image what they believe themselves to be worthy and capable of is irrelevant to the school setting may be just as dogmatic and short-sighted as is the contention that it is the only thing that matters. In Section 4, I cast light on an aspect of students self-concept that must, I argue, be given due consideration in any viable paradigm of good education: namely selfconfidence, or what psychologists prefer to call perceived self-efficacy. All in all, this is an essay in retrieval. Both the rise and the fall of the self-esteem movement hit the educational world like an intellectual earthquake. Now it is time to take

stock: What has really been damaged? What must be rebuilt? And of no less importance: What has actually been left untouched? 2. The self-esteem fallacy Questions of self and identity have fascinated philosophers since antiquity. This interest rubbed off on the precursors of modern psychology, most notably William James. It was James (1890/1950) who constructed what has come to be known as the social science conception of (global) self-esteem, as ones level of satisfaction with the general ratio of ones achievements to aspirations. The first operationalised notion of an aspect of a persons self was born, and with it the more general occupation with what psychologists would henceforth refer to as self-concept. Interest in the self, as in other internal constructs, waned considerably in psychological circles during the heyday of behaviourism, from the 1920s to the 1950s. It was rekindled with redoubled forced in the 1960s, with the advent of humanistic psychology, which was, of course, all about finding, accepting and actualising ones true self. It was during this time spurred by humanistic psychologys view of education as self-therapy that the mantra of the paramount importance of self-esteem spread to the school arena and became the rallying cry of progressive educators. By the early 1980s, self-esteem had become a household term in educational circles, especially in Britain and the US; yet the general public had scarcely taken notice. A search of 300 UK newspapers in 1980 did not locate a single use of the term. That was all to change soon, however; and by the turn of the century, the popular media abounded in references to self-esteem (see Furedi, 2004, p. 3). As the fashion pundits would put it, the preoccupation with self-esteem was so much 1990s. Old hat perhaps for insiders, but as noted in the Introduction, the emperoris-naked disclosure has not yet fully filtered through to the public. Meanwhile, many educationists now preserve their own favourite snippet of the ferocious generalisations engaged in during the 1990s: the grandiose and extravagant claims made in the name of self-esteem that ultimately resulted in its ironic overkill. At the most general level, the main claim of the self-esteem movement was that a lack of global self-esteem a lack of satisfaction with ones general achievements-toaspirations ratio lies at the bottom of the cesspool of educational under-achievement, juvenile delinquency and almost any other personal and social ill (ranging from excessive masturbation to serial killings!) one can think of (see, e.g., Branden, 1969). No one seemed to be immune from this malaise: Girls fragile self-esteem starts to plummet once they approach adolescence and realise that they are valued only for their looks, not for their brains; boys self-image comes under attack at around the same time when they are expected to begin living up to the stereotyped image of the cool and rowdy male. Selfesteem needs to be injected into young people in the home and the school to vaccinate them against those ills and to carve out for them a safe path through school, work and life in general. The most notorious example of the smug and attitudinising although no doubt well meaning efforts of the self-esteem movement was the establishment of a state-funded Self-Esteem Task Force in California, which was meant to concentrate on ways of improving self-esteem as a unifying concept to reframe American problem solving (see, e.g. Stout, 2000, p. 13). Gradually, the self-esteem movement spawned its

own cottage industry, making millions, offering everything from self-help manuals to jewellery specifically designed to help people soak up self-esteem. The assumption of young peoples vulnerable self, constantly in danger of a dearth of reflexive esteem if they experience any frustration, hardship or difficulty, had obvious educational ramifications (see Damon, 1995; Stout, 2000). Tough school work could be stifling, especially if introduced too early; the same applied to the teachers criticisms, corrections and direct instructions. Any competition or grading was also looked upon with a beady eye. Everybody was supposed to feel good at school at all times, and self-affirming, sycophantic messages proliferated (I am great; you are great, no matter what), because students who feel good about themselves allegedly made better learners. A backlash was long overdue, and it eventually crowded in from various quarters through a battery of criticisms. Philosophical critics complained that global self-esteem was a banal and artificial construct which obscured our rich ordinary-language repertoire of self-evaluation concepts and dislodged any reasonable criteria for distinguishing between truthful and untruthful feelings about oneself (Smith, 2002; Cigman, 2004). Educational critics argued that the self-esteem movement had wreaked havoc with educational standards and dumbed down the curriculum. More specifically, self-esteem advocates were showed to have committed a number of missteps. (a) Transparently undeserved flattery is demotivating rather than motivating, condescending rather than uplifting. If students are rewarded for achievements that are fake and independent of effort, they quickly learn to enjoy self-esteem without making an effort (Damon, 1995). (b) It is not true that what you lose on true attainment, you make back on an enhanced self. A diminution of educational standards may boost short-term positive feelings but it damages students long-term self-image and wellbeing, as well as the interests of society at large (Damon, 1995). (c) By trading substance for image, we have replaced the timehonoured educational ideal of a truth-seeking self with a narcissistic and ultimately cynical chimera-seeking self (Stout, 2000). Moral critics added their weight to anti-selfesteem backlash: (a) Is the obsession with a subjective feel-good factor not symptomatic of a misguided morality that has abandoned self-respect in favour of hedonism (Kristjnsson, 2006)? (b) Does the idea of external under-nourishment of self-esteem as the root of personal failures not perpetuate the myth of all losers and malefactors as blameless victims (Lamb, 1996)? (c) Does the empty praise bestowed up students as a result of the feel-good philosophy not teach them hypocrisy rather than a true valuing of oneself and others (Stout, 2000)? The potency of those criticisms notwithstanding, it was not until the publication of a number of comprehensive meta-analyses of the actual findings of psychological research into self-esteem and its various alleged correlates that the self-esteem movement finally gave up its academic ghost (see especially Emler, 2001; Baumeister et al., 2003). Those results have been well documented in the academic and popular literature (even making headlines in magazines such as Newsweek), and there is no need to review them in detail here. Let it suffice to say that the expected correlations between high self-esteem and salient, positively valenced factors, such as above-average school achievement and pro-social behaviour, failed to materialise in the empirical research. Null findings abounded, in fact, and, if any consistent correlation existed, it seemed to be a link between high self-esteem and various types of risky and anti-social behaviour. As

difficult as it may have been to stomach for social scientists whose work had been hagridden for years by a self-esteem fallacy, the results did carry a positive message about psychologys ability to self-correct. Psychology could deconstruct its own constructs, should they fail to have grounding in real experiences; it was not required, as some critics had suggested, to adhere to its nasty tendency of producing sleight-of-hand stipulative concepts and self-fulfilling prophecies. In hindsight, we may wonder if what collapsed was simply a particular fallacious view in psychology and education, or if this view was perhaps emblematic of a whole ideological current in contemporary Western thought: a current which considers peoples selves to be essentially weak, disembedded and in need of reflexive discovery/retrieval a current which has replaced a progressive view of human beings as active social agents with a regressive inward gaze, and which has psychologised and therapeutised the bulk of modern life (cf. Furedi, 2004). We may, furthermore, ask whether this general current, of which the self-esteem movement was then a mere side-stream, constitutes a dangerous permutation of contemporary liberalism, as some critics seem to suggest (Stout, 2000; Furedi, 2004), or whether it is the natural outgrowth of liberalisms ultra-thin conception of the common human good and radical value-pluralism. If the latter were the case, we might need to do more than consign one particular fallacious view to the historical scrapheap; nothing less than a whole world view might be at stake. This is not the place even to begin an exploration of such large philosophical questions. Let me simply note, at the end of this historical survey, some practical implications for schooling. The self-esteem movement placed students inside a cocoon of low expectations and abundant but hollow rewards. After its demise, we can safely return to a more classical conception of students as thriving on wholesome ambition and not being in danger of becoming overburdened, overstressed or overwhelmed if we expect them to achieve. As Damon correctly notes, young people progress most when they are given demanding challenges and chances to prove themselves (1995, pp. 22, 84). Our expectations are best pitched at a level slightly above the one which the students have currently mastered. Meeting new challenges of that sort helps students to cultivate a positive, while at the same time justified, image of themselves as learners, and that can hardly be a bad thing. In fact, it might well be the case that although global self-esteem proved to be barren, domain-specific self-esteem of oneself as a learner is related to educational achievement. I leave that suggestion for future empirical research. Shedding ones belief in the industriously propagated legend of the value of global self-esteem hardly comes without cost. What has been objected to most strenuously in the case of global self-esteem as an educational ideal may well hit at other recent trends in education, powered by similar considerations. That much has been at least hinted at by some of the self-esteem critics. It is thus time to ask: After defusing the self-esteem fallacy, quo vadis? 3. Individualised education If global self-esteem is no longer to be touched with a barge-pole, what other educational ideals of late might be partners in crime? In this section, I concentrate on one possible culprit and a famous buzzword of our times: the concept of individualised education. Individualised education is, despite its recent wide appeal in educational circles, not without its critics. Of those who dispute the method, most of them cavil at its

impracticalities. It is unfeasible, they argue, to tailor education to the personal needs of 30 or more students working under one ceiling. Other detractors note the inherent contradictions in its philosophy of helping students master non-standardised, flexible aspirations at their own pace, in order to equip them for life in the real world of standardised tests, standardised working-sector demands and inflexible working hours! I sidestep those staple criticisms here the followers of individualised education, after all, also have staple responses to them to focus on a more specific objection that connects to my previous discussion. Smith (2006, p. 51) is concerned that the type of individualised education most touted in the UK personalised learning may have been infected by the self-esteem mantra. De Waal (2005) airs similar concerns about the differentiation version of individualised education that has been gaining ground in the US. She believes that differentiation devotees have psychologised education in order to serve the unsavoury agenda of political correctness, and that they primarily pursue what should be educations secondary goal: student self-esteem. If ideas of individualised education are mere ripples in the same wave that drove the self-esteem movement, perhaps individualised education must reasonably fall by the wayside as well. This is a matter worthy of exploration. Let me first note that individualised education is a somewhat distended term, used to denote an array of educational strategies, ranging all the way from the Open School to behaviourist systems of instruction based on individually tailored stimuli and responses. The term individualised education yielded no less than 1.220.000 results in Google in November 2006. A quick look at the content of some of those websites indicates almost as much substantive and methodological divergence as convergence. In this section, I concentrate on personalised learning and differentiation (or differentiated instruction), for two reasons: (a) They happen to be the versions directly referred to as possible victims of the self-esteem fallacy by the two critics mentioned above and (b) they are widely popular at the moment in different parts of the world. Differentiation is, for instance, sweeping all before it in my corner of the world: Scandinavia. Personalised learning already turns up 454.000 entries in Google (Nov. 2006) and differentiated instruction 606.000 (a staggering increase from the 41.100 websites found in a similar search conducted in September 2004). In the UK, personalised learning has the backing of the government, as the way forward in education. Smith (2006, p. 51) specifically mentions the UK-government-sponsored website on this method, and other internet material linked from that site, as promulgating views in line with the self-esteem orthodoxy (students do not flourish at school when learning-tasks are pitched dauntingly high, for instance). A scrutinising of this material may reveal if Smiths complaint is fair. There is a great deal of political rhetoric on those web pages, especially longwinded speeches by the erstwhile minister responsible for school standards, David Miliband. Yet precisely those speeches enlighten us considerably about the philosophy behind personalised learning. It is said to be an integral part of the governments educational policy of high standards in education being available to all. According to the minister, personalised learning means building the organisation of schools around the needs, interests and aptitudes of individuals pupils; is means shaping teaching around the way different youngsters learn; it means taking the care to nurture the unique talents of every pupil. Special emphasis is placed on the needs of the gifted learner, who no

longer ostracised as a smart-alec will thrive in a school celebrating individual success and challenging the culture of low aspirations. All in all, personalised education lays the foundation of an educational system moulded around the child, not of a child moulded around the system. Apart from the ministers lofty speeches, similar visions recur on page after page: In addition to the promise of having individual needs met, there is sharp focus on cultivating the autonomy of older students, by giving a voice to those at the secondary-school level, at least, and thereby motivating them to make decisions about their own education. So, youngsters at the age of 1419 are promised significant curriculum choice. This is supposed to be part of the governments intention to place citizens at the heart of public services and to provide them with a say in the design and improvements of the systems that serve them (Personalised Learning Website, 2006). As pellucid as some of those promises are, it is not as clear where the centre of theoretical gravity lies in the philosophy of personalised learning. There is one reference to the multiple intelligences of pupils la Gardner, but no other educational approach or thinker is mentioned. The web pages in question are also singularly short on practical advice for precisely what is to be done in the classroom; indeed, a teacher with no other resources would starve on them. There is talk of greater collaboration with families, companies and the community at large; of diverse teaching strategies that need to be employed; and of schools being given greater flexibility for the allocation of their teaching resources, but there is little in the form of direct didactics. For present purposes, that is not a salient issue, however. My aim in delving through these pages was to gauge the extent to which they may have been contaminated by the self-esteem fallacy. Pace Smith, I find no indication on this website or in the linked material to suggest that personalised learning has any special truck with the self-esteem movement. There is no mention of the word self-esteem or the danger of too daunting challenges. By contrast, there is a warning against allowing students to coast at their preferred pace of learning and there are exhortations about giving students the confidence and skills to succeed (Personalised Learning Website, 2006). It may well be that the British government has a soft spot for self-esteem I have noticed elsewhere that the governments advisory group on Education for Citizenship and the Teaching of Democracy in Schools considers selfesteem to be an important core skill (Furedi, 2004, p. 62) but any such preferences are happily absent from the material on personalised learning. Let us now shift our scrutiny to the (originally U.S.-based) educational approach of differentiated instruction. Its founder and current guru is Carol Ann Tomlinson, and I have studied two of her canonical works and two recent papers (Tomlinson, 1995; 1999; 2000; Tomlinson et al., 2003). One-size-for-all instruction will sag or pinch, she says (given student variances in readiness, interest and learning styles), exactly as single-size clothing would. In contrast, differentiating instruction means shaking up what goes on in the classroom so that students have multiple options for taking in information, making sense of ideas, and expressing what they learn (Tomlinson, 1995, pp. 23). Differentiation becomes a new way of thinking about teaching and learning: a philosophy (Tomlinson, 2000, p. 6). As an educational philosophy, differentiation is defined as an approach to teaching in which teachers proactively modify curricula, teaching methods, resources, learning activities, and student products to address the diverse needs of individual students and small groups of students to maximize the learning opportunities for each student in the classroom (Tomlinson et al., 2003, p. 121).

As with personalised learning, Tomlinsons differentiation is never clearly specified in a distinct theoretical background animating the project. The problem with differentiation is not so much a lack of reference to historical precedents, as was the case with personalised learning. The problem here is quite the opposite: We are offered a smorgasbord of quite diverse thinkers and ideals that have allegedly been synthesised into this new philosophy. There is learning-profile theory; recent brain research; Gardners multiple intelligences; Csikzentmihalyis flow; and last but not least, constructivism. However none of these theories is explicated in detail; nor are we told the exact use that has been made of them. We already know that constructivism can, for instance, mean a number of different things. It can refer to (a) a didactic thesis about teaching being most effective when it connects to students existing knowledge structures; (b) a psychological thesis about all learning necessarily taking place via students own knowledge construction rather than through information provided to them by others; (c) an epistemological thesis about all knowledge being constructed knowledge; and (d) a metaphysical thesis, about there being no objective, knower-independent truth abroad in the world. Those four theses tend to be loosely run together in much of the recent education literature. Yet they are far from being equivalent; one could, for example, subscribe whole-heartedly to (a) and perhaps tentatively to (b), while remaining agnostic on (c) and rejecting (d). Unfortunately, Tomlinson gives us few clues about the type of constructivism she espouses; her mention of building on the knowledge students bring to class may indicate that she merely draws on the least radical and least controversial thesis (a). Although Tomlinson is eager to characterise differentiation as a philosophy rather than as an instructional strategy, her work is teeming with practical didactic advice. The most general tip is to use diverse instructional strategies that fit different students (or the same students at different times and in different subjects). Another overarching point of emphasis is to train students critical thinking throughout their studies. More specifically, Tomlinson describes a variety of specific manoeuvres such as individual work folders, individual conferences with the teacher, small-group projects, writing-critique groups, tiered assignments and learning centres (see, e.g., Tomlinson, 1995, pp. 36 and Appendix). She is also concerned about underlining the significant degree to which teachers are, in fact, willing to respond to learner variance (Tomlinson et al., 2003). Is Tomlinsons primary goal, as De Waal has suggested (2005), to boost students self-esteem; and does that goal then carry the possibility of lowered standards and a curriculum pitched exactly at the students current levels of aptitude in order not to hurt their feelings? I have tried but altogether failed to find either this goal or its implications in Tomlinsons work. She recommends that teachers create tasks that are a chunk more difficult that one believes students can accomplish. Thus students are encouraged to work up, not down (Tomlinson, 1995, pp. 17, 45) advice that also applies to the most gifted students (Tomlinson, 2003 et al., p. 123). In sum, classrooms are supposed to be places of rigorous intellectual requirements, zones of proximal development, where simply reducing expectations in order to achieve plain sailing is proscribed (Tomlinson, 2003 et al., pp. 121, 123, 127). Moreover, educational content matters more than form or image: Tomlinson berates a teacher who taught students to write paragraphs in class simply to write paragraphs, without regard for meaning (Tomlinson, 1999, pp. 4041);

and she thinks there is no inherent contradiction between differentiation and standardsbased teaching (Tomlinson, 2000). If this were not unambiguous enough, Tomlinson emphatically forswears self-esteem as a goal of teaching, but recommends self-efficacy instead: Self-esteem is fostered by being told that you are important, valued, or successful. Self-efficacy, by contrast, comes from stretching yourself to achieve a goal that you first believed was beyond your reach (Tomlinson, 1995, p. 15). In summary, then, there is no freight heaped on students self-esteem in the official UK material on personalised learning, and the guru of differentiation goes out of her way to reject self-esteem as an educational goal. This does not mean that the selfesteem movement may not have had a pernicious influence on various strands in educational thought in the 1980s and 1990s influence that now needs to be wound down. It simply means that the dismissal of one-size-fits-all instruction, implicit in the concept of individualised education, emerges unscathed from any encounter it may have once had with the now-discarded self-esteem fallacy. 4. Self-confidence Given how ill-suited global self-esteem turned out to be as a predictor of positively valenced outcomes such as school achievement or any outcomes for that matter one may start to wonder if there is any significant correlation between a persons self-concept and life success. Has psychologys obsession with the ramifications of self-concept simply been a wild-goose chase? In my view, it strains credulity to think that peoples image of themselves has no bearing on how well they do in their life tasks. As noted earlier, a persons self-concept comprises many different aspects. Showing that one of them global self-esteem fails as a predictor of achievement is not tantamount to showing that none of the aspects matter. I have already suggested that domain-specific self-esteem may be a worthy candidate for exploration. Rather than pursuing that line of inquiry here, let me focus on another aspect: self-confidence. Folk psychology teaches us that, given the same level of ability, people who firmly believe in their ability to accomplish a given task are more likely to be able to accomplish it than those who doubt their ability. Folk psychology must be taken with a grain of salt; its educated guesses often turn out, on close inspection, to be half-truths or truths and a half. One of the callings of academic psychology is to subject such teachings to rigorous empirical investigation and either support or refute them. In this case, however, the folk-psychology hypothesis seems to be close to the truth. The recent psychology literature is replete with findings of a strong correlation between self-confidence and life success, including academic achievement (see, e.g. Bandura, 1997, Ch. 6; Valentine, 2001). We must be cautious not to smuggle in covertly through the side window considerations that have just been kicked out the main door: How can self-confidence be so vital to achievement if self-esteem matters so little? It requires only a minutes reflection, however, to realise that the contours and implications of self-confidence are radically different from those of self-esteem. Self-confidence is concerned with what one hopes to accomplish; self-esteem is concerned with what one believes oneself to have accomplished. Without prejudging the precise type of psychological entities that selfconfidence and self-esteem are, the former is clearly related to optimism and pessimism; the latter to pride and shame. Having a low opinion of the present ratio of ones

achievements to aspirations does not mean that one doubts ones ability to improve that ratio in due course; conversely, having high global self-esteem here and now does not mean that one judges oneself to be capable of maintaining ones present standing or improving it. Self-confidence is not a concept reared in the same abstract discursive tradition of self-worth or self-value as self-esteem is; at the same time it is less artificial, more earthbound. All teachers and sport coaches know what it means for their students and athletes to be brimming with or wanting in confidence; only those in the thralls of the self-esteem fallacy will care if these students and athletes have high self-esteem. It is no coincidence that the material on individualised education scanned here for possible allusions to self-esteem actually only contained references to student confidence and self-efficacy, respectively. Self-efficacy or, more precisely, perceived self-efficacy is the typical psychological jargon of the day for selfconfidence. (The claim that there is a correlation between self-efficacy and achievement would, of course, be a mere truism; the interesting claim is that there is a correlation between self-efficacy beliefs and achievement.) The social cognitivist, Albert Bandura (1997), is the father of perceived-self-efficacy research, which has already an extensive line of descent. I prefer to avoid unnecessary jargon and simply talk now about research on self-confidence a term which has a comfortable home in common parlance. But before saying more about self-confidence, it is salutary to understand why Bandura and his colleagues prefer the cumbersome neologism perceived self-efficacy. The first reason given is that self-confidence is commonly run together with self-esteem. That may well be true (see, e.g., Bandura, 1997, p. 12; Furedi, 2004, p. 159). However, it is usually more serviceable in conceptual analysis to try to clarify existing concepts rather than to create new ones. Although neologisms may be necessary to convey shades of meaning that simply do not exist in ordinary language (take the helpful, if controversial, construct of IQ), Ockhams razor should be applied whenever possible. The second reason is that the type of self-confidence Bandura is interested in and takes to be a significant correlate of achievement is domain-specific or item-specific self-confidence. The term self-confidence, in ordinary language, is, by contrast, commonly understood globally, just as self-esteem is commonly understood in psychological research (cf. Bandura, 1997, pp. 40, 50). Two things may be said in response: (a) Not all self-efficacy theorists follow Bandura in construing the term non-globally witness, for instance, Schwarzer and Jerusalems (1995) global self-efficacy scale, which is eerily reminiscent of typical self-esteem measures. (b) If what we are interested in is domain-specific selfconfidence, then we can simply say domain-specific self-confidence. It is no more cumbersome than perceived self-efficacy and has the additional advantage of respecting ordinary language. This is why I think it is wise to overrule Banduras self-imposed division between perceived self-efficacy and self-confidence and simply rely on the latter, hereafter to be understood exclusively as domain-specific self-confidence. Banduras book (1997) is a tome, and I cannot do justice to all its subtleties here. What I would like to point out is that it contains a wealth of information that should be of interest to educators. Bandura understands self-confidence as a belief in ones capabilities to organise and execute the courses of action required to produce a given attainment. The book weaves together theoretical and empirical considerations to show that a persons (P) self-confidence vis--vis a task (T) students self-confidence with respect to a given assignment, for instance substantially influences the course of action P chooses to

pursue, how much effort P puts forth, how long P perseveres in the face of obstacles and failures, the levels of stress P experiences in coping with T and, ultimately, the likelihood of Ps accomplishing T (Bandura, 1997, p. 3). Bandura argues that self-confidence is cultivated through enactive mastery experiences, vicarious experiences provided by role models, verbal persuasion and allied types of social influences and physiological and affective states (Bandura, 1997, Ch. 3). Of those sources, the first and most essential one (mastery experiences) turns out to resonate fully with the emphasis placed by various authors cited earlier in this paper on the need to help students work up: learn to accomplish tasks that are slightly above their present level of attainment through perseverant effort, even when this means that they have to face temporary displeasing realities about gaps in their current knowledge and competencies. Of special interest for educators is Banduras discussion of the growth of selfconfidence through the transitional experiences of adolescence the time when many students have lost their early eagerness to try their luck at every suggested school project, believing instead that they are useless at this and that and what teachers can do to guide them through this make-or-break period (1997, 177184). Furthermore, Bandura is keenly aware of the extent to which teachers are able to stimulate self-confidence in students only if they possess enough of it themselves (1997, pp. 240243). 5. Concluding remarks To recapitulate the principal points of my discussion, I rehearsed the rise and fall of the self-esteem movement in Section 2 and asked what would happen in education once its worm-can had been fully opened. Some critics of the self-esteem movement think that it may have infected the ideas behind the concept of individualised education that was gathering pace during the halcyon days of global self-esteem. My exploration of individualised education or at least the two popular versions of it canvassed in Section 3 personalised learning and differentiated instruction indicated that the thrust of this criticism could not be sustained. The emphasis placed on students self-concept in both versions can be more charitably interpreted as a call for cultivating a students selfconfidence than for cultivating a students self-esteem. In Section 4, I explored the nature and value of self-confidence and concluded that it is, indeed, an aspect of self-concept that needs to be considered and after sloughing off global self-esteem retrieved. Other aspects of self-concept, such as domain-specific self-esteem and (perhaps even more importantly) self-respect, may be equally crucial for educational achievement and also stand in need of retrieval. But those must remain topics for another day.

References Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co. Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I. & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 144. Branden, N. (1969). The psychology of self-esteem: a new concept of mans nature. Los Angeles: Nash Publishing. Cigman, R. (2004). Situated self-esteem. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 38(1), 91105. Damon, W. (1995). Greater expectations: overcoming the culture of indulgence in our homes and schools. New York: Free Press. De Waal, A. (2005) When kindness kills standards. Retrieved 10 October 2006 from http://www.civitas.org.uk/blog/2005/03/when_kindness_kills_standards.html. Emler, N. (2001). Self-esteem: the costs and causes of low self-worth. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Furedi, F. (2004). Therapy culture. Cultivating vulnerability in an uncertain age. London: Routledge. James, W. (1890/1950). The principles of psychology, vol. 1. New York: Henry Holt & Co. Kristjnsson, K. (2006). Emotional intelligence in the classroom: an Aristotelian critique. Educational Theory, 56(1), 3956. Lamb, S. (1996). The trouble with blame. Victims, perpetrators, and responsibility. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Personalised Learning website (2006). Retrieved 10 October 2006 from http://www.teachernet.gov.uk/management/newrelationship/personalisedlearning. Schwarzer, R. and Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright & M. Johnston (Eds.) Measures in health psychology. A users portfolio (pp. 3537). Windsor: NFERNelson. Smith, R. (2002). Self-esteem: the kindly apocalypse. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 36(1), 87100. Smith, R. (2006). On diffidence: the moral psychology of self-belief. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 40(1), 5162. Stout, M. (2000). The feel-good curriculum: the dumbing down of Americas kids in the name of selfesteem. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. Tomlinson C. A. (1995). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom. Responding to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Tomlinson, C. A. (2000). Reconcilable differences? Standards-based teaching and differentiation. Educational Leadership, 58(1), 611. Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A. & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: a review of literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2/3), 119145. Valentine, J. C. (2001). The relation between self-concept and achievement: a meta-analytic review. Doctoral dissertation. University of Missouri-Columbia.

10

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Demands of Society From The Teacher As A ProfessionalDocument54 pagesThe Demands of Society From The Teacher As A ProfessionalJessa Yaun100% (30)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- EdTPA-Task 1 PromptsDocument5 pagesEdTPA-Task 1 PromptsChelsea Keeney75% (4)

- Stalinism and Nazism History and Memory ComparedDocument347 pagesStalinism and Nazism History and Memory Comparedpaulspeaking0% (1)

- Norway's EconomyDocument12 pagesNorway's EconomypaulspeakingNo ratings yet

- Example of A Personal StatementDocument1 pageExample of A Personal StatementMohammed KaisNo ratings yet

- Literature Review 1Document5 pagesLiterature Review 1api-313854060No ratings yet

- Pemahaman SEC BDocument7 pagesPemahaman SEC BSugunes SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Franz KafkaDocument162 pagesFranz Kafkapaulspeaking100% (7)

- Thoughts On FaithDocument1 pageThoughts On FaithpaulspeakingNo ratings yet

- d4 Stalin Revision NotesDocument67 pagesd4 Stalin Revision NotespaulspeakingNo ratings yet

- The Fall of France - Act With Daring. - Osprey Publishing LTDDocument162 pagesThe Fall of France - Act With Daring. - Osprey Publishing LTDpaulspeaking100% (2)

- A Kocho-Williams Sovietdiplomats1920sDocument25 pagesA Kocho-Williams Sovietdiplomats1920spaulspeakingNo ratings yet

- Focus MagazineDocument4 pagesFocus MagazinepaulspeakingNo ratings yet

- Zero HourDocument3 pagesZero HourpaulspeakingNo ratings yet

- 1933 34 Consolidation ExcerciseDocument3 pages1933 34 Consolidation ExcercisepaulspeakingNo ratings yet

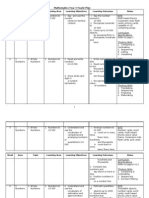

- Mathematics Year 3 Yearly Plan: Week Area Topic Learning Area Learning Objectives Learning Outcomes NotesDocument20 pagesMathematics Year 3 Yearly Plan: Week Area Topic Learning Area Learning Objectives Learning Outcomes NotesAnonymous qXklPgGnMVNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Game-Based Learning On Students'Document13 pagesThe Effect of Game-Based Learning On Students'Ismi IrniNo ratings yet

- SM 004s.2021 Contextualized Enrolment MechanismSY2021-2022v2Document8 pagesSM 004s.2021 Contextualized Enrolment MechanismSY2021-2022v2Abdul Jakeem CastanosNo ratings yet

- Semester 2, Electrical Engineering Paper (UOM)Document6 pagesSemester 2, Electrical Engineering Paper (UOM)RuchirangaNo ratings yet

- Liaison PackageDocument10 pagesLiaison PackageaimenmajidkhanNo ratings yet

- Student Development Theory Autobiography FinalDocument10 pagesStudent Development Theory Autobiography Finalapi-541684468No ratings yet

- Applied PsychologyDocument362 pagesApplied Psychologyprajjwal100% (1)

- Sosiologi MusikDocument17 pagesSosiologi MusikgumelarNo ratings yet

- Foundation Final ExamDocument11 pagesFoundation Final ExamLeo Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesSaiza BarrientosNo ratings yet

- Smart City Market Report 2Document19 pagesSmart City Market Report 2Pallavi ReddyNo ratings yet

- Betwixt and BetweenDocument9 pagesBetwixt and BetweenguegeNo ratings yet

- Performance Assessment in Classroom - GardenDocument18 pagesPerformance Assessment in Classroom - Gardenapi-113553268100% (1)

- Candidate Booklet: Aiesec Regional Recruitment 2011Document15 pagesCandidate Booklet: Aiesec Regional Recruitment 2011Chứng Hạo ChangNo ratings yet

- Student Observation Record: Electrical Machines-Ii LabDocument52 pagesStudent Observation Record: Electrical Machines-Ii LabAnushkaNo ratings yet

- Improving Pedagogical Skills in Advanced Mathematics For Grade 1 3 TeachersDocument10 pagesImproving Pedagogical Skills in Advanced Mathematics For Grade 1 3 TeachersJulius BaldivinoNo ratings yet

- What's Wrong With ConstructionismDocument16 pagesWhat's Wrong With Constructionismm_gugeanu1No ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Right of Children To Free andDocument8 pagesA Critical Analysis of The Right of Children To Free andrajendra kumarNo ratings yet

- Philosphy of Education 2Document2 pagesPhilosphy of Education 2api-456376421No ratings yet

- Francisco E. Barzaga Integrated High School's Incapability of Providing STEM StrandDocument6 pagesFrancisco E. Barzaga Integrated High School's Incapability of Providing STEM StrandCharmaine berNo ratings yet

- اسئلة نهاية السنه ثاني متوسط دور ثاني محمد الراويDocument2 pagesاسئلة نهاية السنه ثاني متوسط دور ثاني محمد الراويxxdkrarNo ratings yet

- GPA Per SubjectDocument15 pagesGPA Per SubjectSHEILA MAE PERTIMOSNo ratings yet

- Wikis in EducationDocument3 pagesWikis in Educationchazzman311No ratings yet

- I A and Border Guard Job Advert NovemberDocument2 pagesI A and Border Guard Job Advert Novembermwansa davidNo ratings yet