Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Screentime in Japan

Screentime in Japan

Uploaded by

Euis Sri Nurhayati BasariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Screentime in Japan

Screentime in Japan

Uploaded by

Euis Sri Nurhayati BasariCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Pediatrics | Original Investigation

Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children

at 1-3 Years of Age in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study

Midori Yamamoto, PhD; Hidetoshi Mezawa, MD, PhD; Kenichi Sakurai, MD, PhD; Chisato Mori, MD, PhD; for the

Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE It is unclear whether increased television (TV) and DVD viewing in early

childhood from age 1 year decreases development or whether poor development increases

TV/DVD viewing.

OBJECTIVE To investigate the directional association between TV/DVD screen time and

performance on developmental screeners in children aged 1 to 3 years.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This longitudinal cohort study analyzed data from

57 980 children and mothers from a national birth cohort, the Japan Environment and

Children’s Study. Data were collected in collaboration with 15 regional centers across Japan.

The mothers were recruited between January 2011 and March 2014. Analyses using random

intercept, cross-lagged panel models were performed for children aged 1, 2, and 3 years. Of

100 303 live births, children with missing developmental screening test scores and screen

time data, those with congenital diseases or cerebral palsy, and those diagnosed with an

autism spectrum disorder were excluded. Statistical analyses were conducted from October

2022 to July 2023.

EXPOSURES TV and DVD screen time.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Child development at ages 1, 2, and 3 years was assessed via

the mother’s or guardian’s report using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, third edition.

RESULTS Of 57 980 included children, 29 418 (50.7%) were male, and the mean (SD)

maternal age at delivery was 31.5 (4.9) years. A negative association between screen time and

developmental scores was observed. Increased TV/DVD screen times at age 1 and 2 years

were associated with lower developmental scores at age 2 and 3 years, respectively (2 years:

β = −0.05; 95% CI, −0.06 to −0.04; 3 years: β = −0.08; 95% CI, −0.09 to −0.06). An obverse

association was observed from the Ages and Stages Questionnaires, third edition, score in the

communication domain at age 1 and 2 years to subsequent screen time (2 years: γ = −0.03;

95% CI, −0.04 to −0.02; 3 years: γ = −0.06; 95% CI, −0.07 to −0.04).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE In this study, increased TV/DVD screen time from age 1 year

negatively affected later development. To reduce the negative consequences of excessive

media use, researchers and health care professionals should encourage family media

management and recommend social support for parents who tend to rely on the media.

Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

article.

Group Information: A complete list

of the members of the Japan

Environment and Children’s Study

Group appears in Supplement 2.

Corresponding Author: Midori

Yamamoto, PhD, Department of

Sustainable Health Science, Center

for Preventive Medical Sciences,

Chiba University, 1-33 Yayoi-cho,

JAMA Pediatr. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3643 Chiba 263-8522, Japan (midoriy@

Published online September 18, 2023. faculty.chiba-u.jp).

(Reprinted) E1

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Research Original Investigation Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age

R

esearchers have reported a significant increase

in the number of children with neurodevelopmental Key Points

and mental health problems, including language,

Question Is increased television/DVD screen time in infants

l e a r n i ng , b e h a v i o r a l , a n d e m o t i o n a l d i s o r d e r s . 1 , 2 associated with poor performance on developmental screeners?

This increase indicates the need to better understand the

Findings In this cohort study of 57 980 children, increased

social, medical, and environmental factors underlying

television/DVD screen time in children aged 1 and 2 years was

developmental problems in early childhood.

associated with lower developmental scores at 2 and 3 years,

Screens, such as television (TV), are ubiquitous in respectively. Lower development scores were associated with

t h e h o m e s o f yo u ng c h i l d r e n . A l t h o u g h p e d i a t r i c increased screen time in children with maternal psychological

guidelines recommend that screen viewing be avoided for distress.

infants younger than 2 years and limited to 1 hour per

Meaning In this study, increased screen time in early childhood

day between the ages 2 and 5 years, 3-5 many children was negatively associated with poor performance on

fail to adhere to these recommendations.6 Excessive screen developmental screeners, suggesting the need to support parents

time in children younger than 3 years is assoc iated in creating family media plans.

with adverse effects on cognitive, language, motor skills,

and soc ial-behav ioral development. 7 - 1 1 Conversely,

c h i ld re n w it h p o o r s e l f - re g u l at i o n a re m o re l i ke l y

to experience more exposure to screens.12-16 However, there

is limited evidence for a causal relationship in early Methods

childhood regarding whether media exposure leads

to developmental delays or whether children w ith Study Design and Participants

developmental delays are more exposed to the media. After The participants included children from the Japan Environ-

accounting for individual traitlike differences, several stud- ment and Children’s Study (JECS). The study design of JECS

ies have used the random-intercepts, cross-lagged panel has been described previously.29 Briefly, 103 060 pregnan-

model (RI-CLPM) to clarify the bidirectional association cies were registered between January 2011 and March 2014 in

between screen time and development (from age 2 to 3 15 regional centers across Japan. We used the dataset jecs-ta-

years).17,18 20190930. We included 100 303 live births, excluding 1254 mis-

Using the RI-CLPM and Ages and Stages Questionnaires carriages, 382 stillbirths, and 2123 with missing birth data. Next,

(ASQ) as a developmental screener, Madigan et al17 showed children were excluded if they met any of the following crite-

that increased screen time at ages 2 and 3 years led to ria: missing developmental score data (n = 35 914) or missing

delayed achievement of developmental milestones at ages 3 TV/DVD screen time data (n = 794) at age 1, 2, or 3 years; had

and 5 years, respectively. The current study provides congenital diseases, cerebral palsy, or missing data (n = 5376);

more convincing evidence of the role of screen use on and diagnosed with ASD (eg, autism, pervasive developmen-

child development and justifies the RI-CLPM used to tal disorder, and Asperger syndrome) at age 3 years or miss-

analyze the bidirectional association. Although brain devel- ing data (n = 239). A total of 57 980 children were included in

opment during the first 3 years of life is critical, as it sets the analysis (eFigure in Supplement 1). Written informed con-

the foundation for future cognitive and emotional sent was obtained from all the participants. The JECS proto-

functioning,19,20 to our knowledge, no study has found a col was reviewed and approved by the Ministry of the Envi-

bidirectional relationship between screen time and develop- ronment’s Institutional Review Board on Epidemiological

ment in young children, including those younger than 2 Studies and the ethics committees of all participating institu-

years. We replicated and extended the study of Madigan tions. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of

et al17 with a larger sample size, at a slightly early age, and Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting

with differential cultural backgrounds. Maternal prenatal or guideline.30

postpartum stress and child’s sex may be associated with

c o g n it ive f u n c t i o n i ng a n d b e h av i o r a l p ro b l e m s i n Measures

children. 21-26 Detecting interactions is crucial for public Developmental Screener

health if maternal stress influences the fetal or children’s Children’s development was assessed by the scores on the Japa-

environment. nese version of the ASQ, third edition (ASQ-3), completed by

We aimed to examine the bidirectional association between the parents or guardians of children aged 1, 2, and 3 years. The

TV/DVD screen time and developmental milestones during early ASQ-3 is widely used for assessing development in commu-

childhood. Additionally, we examined the association in 5 spe- nication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and per-

cific domains and moderation or interaction effect by child’s sex sonal-social domains (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).31 Each do-

and maternal distress. Children with psychiatric disorders, such main comprises 6 questions, and their total scores range from

as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), have been reported to have 0 to 60 points per domain, with higher scores indicating bet-

extreme screen time.27,28 Therefore, we analyzed data from the ter development. The Japanese version of ASQ-3 was vali-

Japanese nationwide birth cohort study on 57 980 children aged dated with moderate to high sensitivity (75.3% to 100.0%) and

1, 2, and 3 years with primarily typical development, excluding specificity (66.7% to 100.0%).32 The mean ASQ-3 scores of 5

those diagnosed with ASD. domains or each domain were used as continuous variables.

E2 JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 (Reprinted) jamapediatrics.com

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age Original Investigation Research

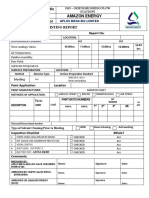

Figure. Random-Intercepts Cross-Lagged Panel Model for Associations Between Television (TV)/DVD

Screen Time and Developmental Outcomes (Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition [ASQ-3], Scores)

Screen time

(stable)

1a

1a 1a

TV/DVD screen αS = 0.15; TV/DVD screen αS = 0.14; TV/DVD screen

time at age 1 y 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.16 time at age 2 y 95% CI, 0.12 to 0.15 time at age 3 y

γ = –0.01; γ = –0.02;

95% CI, –0.03 to 0.01 95% CI, –0.04 to –0.01

σSA = –0.15;

95% CI, –0.18 to –0.12

β = –0.05; β = –0.08;

95% CI, –0.06 to –0.04 95% CI, –0.09 to –0.06

Standardized estimates with 95% CIs

ASQ–3 score αA = 0.09; ASQ–3 score αA = 0; ASQ–3 score

at age 1 y at age 2 y at age 3 y are presented. Solid lines in cross-lag

95% CI, 0.07 to 0.11 95% CI, –0.03 to 0.03

and autoregressive links represent

1a 1a the absolute value of the

1a standardized estimate, which is 0.03

ASQ–3 score or more. Dashed lines represent

(stable)

those less than 0.03.

a

The factor loadings constrained to 1.

Screen Time intercepts to the standard cross-lagged panel model. 34

At ages 1, 2, and 3 years, parents or guardians were asked to re- Owing to the nonnormal distribution of screen time and

port their children’s TV/DVD screen time on by asking, “How ASQ-3 scores, we used an asymptotic distribution-free esti-

many hours do you let your children watch TV or DVD in a typi- mation method.

cal day?” The responses were collected from among 5 catego- Cross-lag association of the screen time with ASQ-3 scores

ries: none, less than 1 hour, 1 hour or more but less than 2 hours, (β) and the association of ASQ-3 scores with screen time (γ) were

2 hours or more but less than 4 hours, and 4 hours or more. estimated in 3 types of RI-CLPM. First, to identify associa-

The categories were converted to corresponding numbers (0 tions between screen time and overall or domain-specific de-

hours, 0.5 hours, 1.5 hours, 3 hours, and 4.5 hours per day, velopment, we performed estimation using the basic

respectively). RI-CLPM (Figure) using mean ASQ-3 scores or scores of each

domain, respectively. Second, to explore the interaction ef-

Predictors fects on the association between screen time and child devel-

In the model to explore the contribution of time-invariant fac- opment, we performed a multiple-group RI-CLPM stratified by

tors on screen time and child development, possible predic- the child’s sex and maternal psychological distress. To evalu-

tors were selected a priori based on the literature,17,27 biologi- ate the interaction effect, we compared a model in which the

cal plausibility, and using a directed acyclic graph. z Scores for lagged regression coefficients were constrained to be equal be-

the following variables were included in the predictor model tween the 2 groups with an unconstrained model, with dif-

using the forced entry method: sex of the child, maternal age ferences in the fit indices between models. We considered the

at delivery, maternal education, annual household income, interaction effect to be insignificant when the difference in the

maternal psychological distress assessed by the Kessler comparative fit index (CFI) was less than 0.010, the change in

Psychological Distress Scale Japanese version33 at 1 year post the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less

partum, the presence of an elder sibling(s), attendance at a than 0.015, and the change in the standardized root mean

childcare facility, frequency of reading to the child, fre- square residual (SRMR) was less than 0.010.35 Third, to ex-

quency of taking the child out of the house (other than the plore the contribution of predictors for screen time and child

childcare facility), and child’s sleep time per day at age 1 year. development, we constructed a predictor-included RI-CLPM

Categorization is illustrated in eTable 2 in Supplement 1. by including between-level predictors affecting the random in-

Data were obtained from the questionnaire completed by the tercepts simultaneously, as presented by Mulder and

children’s parents or guardians as well as medical record Hamaker.36 In all models, benchmark values for interpreting

transcripts. the size of the RI-CLPM cross-lag effect were set at 0.03 (small

effect), 0.07 (medium effect), and 0.12 (large effect).37

Statistical Analysis To assess the robustness of the findings, we performed sen-

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the distribu- sitivity analyses using the basic RI-CLPM for children with com-

tion of participant characteristics. We examined the longitu- plete data at 3 years (n = 70 226). In these analyses, we esti-

dinal and directional associations between TV/DVD screen mated missing TV/DVD screen time data and ASQ-3 scores at

time and ASQ-3 scores using a RI-CLPM (Figure; eAppendix 1 and 2 years using full information maximum likelihood es-

in Supplement 1). This model is a structural equation-based timation and Bayesian estimation with the Markov chain Monte

approach to better approximate within-person (time- Carlo algorithm. The number of cohort participants included

variant) relationships by accounting for between-person and excluded from the analyses and a comparison of basic

(time-invariant, traitlike) stability by including random demographic characteristics are summarized in eTable 3 in

jamapediatrics.com (Reprinted) JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 E3

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Research Original Investigation Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age

Table 1. Directional Association Between Television/DVD Screen Time and Development (Ages and Stages Questionnaires,

Third Edition [ASQ-3] Scores) in Each Domain

Standardized estimate (95% CI)a

Association Communication Gross motor Fine motor Problem-solving Personal-social

Cross-lagged effects

Screen time at age 1 y −0.06 (−0.07 to −0.01 (−0.02 to −0.01 (−0.03 to −0.01 (−0.02 to −0.01 (−0.03 to

and ASQ-3 score at age 2 y, β −0.05) 0) 0) 0) 0)

ASQ-3 score at age 1 y −0.03 (−0.04 to 0.01 (0 to 0 (−0.01 to 0) −0.01 (−0.02 to 0 (−0.01 to

and screen time at age 2 y, γ −0.02) 0.02) 0) 0.01)

Screen time at age 2 y −0.02 (−0.04 to −0.03 (−0.05 to −0.07 (−0.08 to −0.01 (−0.03 to −0.12 (−0.14 to

and ASQ-3 score at age 3 y, β −0.01) −0.01) −0.06) 0) −0.11)

ASQ-3 score at age 2 y −0.06 (−0.07 to 0.02 (0.01 to −0.02 (−0.04 to 0.02 (0 to −0.01 (−0.02 to

and screen time at age 3 y, γ −0.04) 0.03) −0.01) 0.03) 0.01)

Fit indices

CFI 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00

RMSEA (90% CI) 0.01 (0.01 to 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03 (0.02 to 0.02 (0.01 to 0 (0 to

0.02) 0.03) 0.03) 0.02) 0.01)

SRMR 0 0.01 0.01 0 0

a

Abbreviations: CFI, comparative fit index; RI-CLPM, random-intercepts, Benchmark values for interpreting the size of the RI-CLPM cross-lag effect

cross-lagged panel model; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; were set at 0.03 (small effect), 0.07 (medium effect), and 0.12 (large effect).37

SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

Supplement 1. All statistical analyses were conducted using Association Between Screen Time

SPSS and SPSS Amos version 27 (IBM). and ASQ-3 Scores in Each Domain

Each model demonstrated a good fit (Table 1). We observed

small to medium linking from screen time at age 1 year to ASQ-3

scores at age 2 years in the communication domain (β = −0.06;

Results 95% CI, −0.07 to −0.05) and small to large linking from screen

Descriptive Statistics time at age 2 years to ASQ-3 scores at age 3 years in gross mo-

eTable 2 in Supplement 1 summarizes the characteristics of chil- tor, fine motor, and personal-social domains (β range, −0.03

dren and mothers. Of 57 980 included children, 29 418 (50.7%) [95% CI, −0.05 to −0.01] to −0.12 [95% CI, −0.14 to −0.11]). The

were male, and the mean (SD) maternal age at delivery was 31.5 small to medium obverse linking was observed from ASQ-3

(4.9) years. At ages 1, 2, and 3 years, 15 051 children (26.0%), scores in the communication domain to screen time (2 years:

16 430 children (28.3%), and 17 403 children (30.0%) viewed γ = −0.03; 95% CI, −0.04 to −0.02; 3 years: γ = −0.06; 95% CI,

TV/DVD for at least 2 hours per day, respectively. −0.07 to −0.04).

Directional Association Between Screen Time Moderation or Interaction Effects on the Cross-Lags Link

and ASQ-3 Scores Table 2 and Table 3 present the results of 2 multiple-group

The Figure and eTable 4 in Supplement 1 summarize the es- RI-CLPMs stratified by the child’s sex and maternal psycho-

timates in the basic RI-CLPM. Fit indices demonstrated good logical distress. Both models demonstrated a good fit. In the

model fit. Significant variances of random intercepts were ob- model stratified by the child’s sex, we observed no difference

served for both TV/DVD screen time (σS2 = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.44- in the cross-lag effect between boys and girls (Table 2). For the

0.48) and ASQ-3 scores (σA2 = 33.95; 95% CI, 32.31-35.59). This model stratified by maternal psychological distress, we ob-

finding indicated stable individual differences in both screen served no distinct difference between the groups as assessed

time and developmental scores; furthermore, it was reason- by a change in fit indices (change in CFI, 0; change in RMSEA,

able to set a random intercept in the model. Positive autore- 0; change in SRMR, 0). However, a small to medium cross-lag

gressive associations in the screen time (αS2 and αS3) implied association between ASQ scores at age 2 years and screen time

that children with more TV screen time were more likely to con- at age 3 years was observed only in children with maternal psy-

tinue this behavior on subsequent occasions. We observed chological distress (γ = −0.05; 95% CI, −0.07 to −0.02) (Table 3).

negative covariances between random intercepts of TV/DVD

screen time and ASQ-3 scores (σSA = −0.15; 95% CI, −0.18 to Predictors of Screen Time and ASQ-3 Scores

−0.12), suggesting that children with more screen time tended The RI-CLPM with 10 predictors demonstrated a close model

to have lower ASQ-3 scores at ages 1 to 3 years. fit, although poorer than the basic RI-CLPM (CFI, 0.94; RM-

Furthermore, we observed small to medium negative SEA, 0.04; 90% CI, 0.04-0.04; SRMR, 0.02) (data not shown).

cross-lags linking from screen time at age 1 year to ASQ-3 score Increased TV/DVD screen time was associated with not attend-

at age 2 years (β = −0.05; 95% CI, −0.06 to −0.04) and me- ing a childcare facility, no elder sibling(s), infrequent reading

dium linking from screen time at age 2 years to ASQ-3 score at to children, lower maternal education level, psychological dis-

age 3 years (β = −0.08; 95% CI, −0.09 to −0.06). tress, lower income, seldom going outdoors, less sleep time,

E4 JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 (Reprinted) jamapediatrics.com

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age Original Investigation Research

Table 2. Directional Association Between Television/DVD Screen Time Table 3. Directional Association Between Television/DVD Screen Time

and Development (Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition and Development (Ages and Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition

[ASQ-3] Scores) Stratified By Child’s Sex [ASQ-3] Scores) Stratified By Maternal Psychological Distress

Standardized estimate (95% CI)a Standardized estimate (95% CI)a

Association Boys Girls Mentally stable Mental distress

Association (<5)b (≥5)b

Cross-lagged effects

Cross-lagged effects

Screen time at age 1 y and −0.05 (−0.07 to −0.03 (−0.05 to Screen time at age 1 y and −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.06 (−0.09 to

ASQ-3 score at age 2 y, β −0.04) −0.02) ASQ-3 score at age 2 y, β −0.03) −0.04)

ASQ-3 score at age 1 y and −0.01 (−0.03 to 0 (−0.01 to ASQ-3 score at age 1 y and −0.01 (−0.03 to −0.02 (−0.04 to

screen time at age 2 y, γ 0.01) 0.01) screen time at age 2 y, γ 0.01) 0)

Screen time at age 2 y and −0.09 (−0.11 to −0.07 (−0.09 to Screen time at age 2 y and −0.08 (−0.09 to −0.09 (−0.12 to

ASQ-3 score at age 3 y, β −0.07) −0.05) ASQ-3 score at age 3 y, β −0.06) −0.06)

ASQ-3 score at age 2 y and −0.02 (−0.04 to −0.01 (−0.03 to ASQ-3 score at age 2 y and −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.05 (−0.07 to

screen time at age 3 y, γ 0.01) 0.02) screen time at age 3 y, γ −0.01) −0.02)

Fit indices Fit indices

CFI 1.00 CFI 1.00

RMSEA (90% CI) 0.01 (0.01 to RMSEA (90% CI) 0.01 (0 to

0.02) 0.01)

SRMR 0

SRMR 0

Abbreviations: CFI, comparative fit index; NA, not applicable; RI-CLPM,

Abbreviations: CFI, comparative fit index; RI-CLPM, random-intercepts,

random-intercepts, cross-lagged panel model; RMSEA, root mean square error

cross-lagged panel model; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation;

of approximation; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

a

a Benchmark values for interpreting the size of the RI-CLPM cross-lag effect

Benchmark values for interpreting the size of the RI-CLPM cross-lag effect

were set at 0.03 (small effect), 0.07 (medium effect), and 0.12 (large effect).37

were set at 0.03 (small effect), 0.07 (medium effect), and 0.12 (large effect).37

b

Maternal psychological distress was assessed by the Kessler Psychological

Distress Scale Japanese version33 at 1 year post partum.

and younger maternal age (Table 4). In contrast, higher devel-

opmental performance was associated with being female, fre-

quent reading to the child, attending a childcare facility, el- Compared with another Japanese cohort that began in

der sibling(s), younger maternal age, no psychological distress, 2001,38 TV screen time for young children in the JECS cohort born

frequently going outdoors, higher income, and more sleep time. between 2011 and 2014 appeared to decline. This finding was

Even after accounting for the effects of these predictors, the consistent with the decrease in TV and DVD screen times at age

association between random intercepts of screen time and 0 to 8 years from 2011 to 2017 and is likely related to increased

ASQ-3 remained negative (σSA = −0.11; 95% CI, −0.14 to −0.08) use of mobile devices.39 For TV/DVD screen time alone, only 25%

(data not shown). to 29% of the children at ages 2 and 3 years met the guideline

limiting screen time to no more than 1 hour each day.

Sensitivity Analyses Our study results support the findings of a Canadian co-

The basic RI-CLPM was performed using full information maxi- hort study using the RI-CLPM that demonstrated a direc-

mum likelihood and Bayesian estimation for children with com- tional association of greater screen time (TVs, DVDs, comput-

plete data only at age 3 years (n = 70 226). The results were simi- ers, and game consoles) at age 24 months with a lower ASQ-3

lar to the RI-CLPM results for children with complete data at score at age 36 months.17 In addition, we found that screen time

ages 1, 2, and 3 years (n = 57 980) (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). at age 1 year affects poorer communication skills at age 2 years.

The effects on cognitive function may be partially mediated

by reduced activity in the frontal and parietal brain regions.40

Conversely, screen time at age 2 years affected subsequent mo-

Discussion tor and personal-social skills. This may be attributed to miss-

Our study demonstrated that the negative cross-lag associa- ing opportunities to learn motor and interpersonal skills by sed-

tion from screen time to developmental scores remained con- entary looking at screens.

sistent throughout toddlerhood. Notably, we found a bidirec- Our study demonstrated an obverse association from lower

tional association between TV/DVD screen time and ASQ-3 scores only in the communication domain at age 1 year

developmental scores in the communication domain from age to more screen time at age 2 years and a similar association with

1 to 2 years. Additionally, we observed negative associations a stronger effect from age 2 years to 3 years. The factors that

between TV/DVD screen time at age 2 years and the develop- may contribute to increased screen time include low devel-

mental scores in gross motor, fine motor, and personal-social opment of communication skills, an environment that does not

domains at age 3 years. A negative association between the de- promote communication development, and a child’s prefer-

velopmental score at age 2 years and screen time at age 3 years ence for the environment. The association between lower

was observed in the communication domain. No significant ASQ-3 scores and subsequent increases in screen time was par-

interaction by child’s sex or maternal psychological distress was ticularly evident among mothers experiencing mental health

observed. In addition, developmental scores at age 2 years were challenges. These findings underscore the importance of so-

negatively linked to screen time at age 3 years in children with cial support for mothers who may rely on media to manage

maternal psychological distress. their child’s behavior.

jamapediatrics.com (Reprinted) JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 E5

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Research Original Investigation Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age

environment.49 Third, promoting social networks that allow

Table 4. Predictors of Television/DVD Screen Time

and Child Development Among 53 085 Children children to have high-quality interactions with their fami-

lies is important. Active social interaction in the neighbor-

Standardized estimate (95% CI)

hood may promote healthy behaviors, such as reducing

Development

Predictor Screen time (ASQ-3 score) screen time and increasing physical activity levels.50

Maternal age −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.11 (−0.12 to

−0.02) −0.10)

Maternal education −0.11 (−0.12 to 0.02 (0.01 to Strengths and Limitations

−0.10) 0.03) The strength of this study is that it provides insights into the

Household income (≥¥4 million −0.05 (−0.06 to 0.04 (0.03 to directional association between TV/DVD screen time and de-

[≥US $27 863] vs <¥4 million −0.04) 0.05)

[<US $27 863]) velopmental milestones in typically developing young chil-

Maternal psychological distress 0.05 (0.04 to −0.09 (−0.10 to dren. It was based on a large birth cohort dataset representa-

(yes vs no)a 0.06) −0.08)

tive of the Japanese population and provides reliable results.51

Elder sibling (yes vs no) −0.19 (−0.20 to 0.14 (0.13 to

−0.18) 0.15) However, it had some limitations. First, we assessed the de-

Attending childcare facility −0.28 (−0.29 to 0.16 (0.15 to velopmental milestones and screen time based on parental re-

(yes vs no) −0.27) 0.17) ports, which is suitable for collecting data from large popula-

Reading to child −0.13 (−0.14 to 0.18 (0.17 to tions; however, it may have led to reporting bias. Second, there

−0.11) 0.19)

is a single-informant bias, ie, most of the respondents to the

Going outdoors −0.04 (−0.05 to 0.07 (0.06 to

−0.03) 0.08) questionnaire were mothers because they were the primary

Sleep time −0.03 (−0.04 to 0.05 (0.04 to caregivers of their children. These biases may weaken the gen-

−0.02) 0.05)

eralizability of the findings. Third, advances in media tech-

Child’s sex (girls vs boys) 0 (−0.01 to 0.24 (0.23 to

0.02) 0.25) nology may have changed the situation of children’s screen

2

R for the random intercept 0.14 0.15 viewing because children are increasingly exposed to por-

table media screens other than TVs and DVDs from an early

Abbreviation: ASQ-3, Ages and Stages Questionnaires, third edition.

a age. According to a 2016 Japanese survey, smartphone, tab-

Maternal psychological distress was assessed by the Kessler Psychological

Distress Scale Japanese version33 at 1 year post partum. Participants were let, and portable gaming device use among children aged 1 to

considered to be distressed if their score was 5 or greater. 3 years ranged from 2% to 32%.52 In a 2017 US survey, chil-

dren aged 2 to 4 years spent 1 hour a day on both TV and mo-

Frequent reading to the child, attending childcare, and hav- bile devices.39 Information on mobile device usage from age

ing an elder sibling(s) were particularly associated with higher 1 year was not available for this study, which may underesti-

developmental scores and lesser screen time. A similar, albeit mate total screen time. Fourth, the media content available to

weaker, association was observed for taking children out- children is becoming increasingly diverse, and they may be ex-

doors. This finding supports the existing literature41-48 by sug- posed to content intended for adults. Further research is war-

gesting that parent-child verbal interaction, communication ranted on the effects of various screens and different types of

with others, and social play are effective in promoting devel- content on children’s development.

opment for young children, besides being associated with lesser

screen time.

This study highlights several practical recommenda-

tions. First, emphasis should be placed on having opportu-

Conclusions

nities for face-to-face interaction with family members and In this study, TV/DVD screen time was associated with lower

other children rather than relying on screens from an early subsequent developmental performance in young children.

age to enhance children’s development. Second, pediatri- Screen media is prevalent in children’s environments, thus ne-

cians and health care professionals should help each family cessitating tailored media plans for each family for the better

develop a feasible media plan by making recommendations development of their child. In addition, parents experiencing

and introducing social support tools because parental atti- emotional distress require support in reducing their chil-

tudes toward media use significantly effect the home media dren’s exposure to screens from an early age.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Center for Child Health and Development, Tokyo, All authors.

Accepted for Publication: July 24, 2023. Japan (Mezawa); Department of Nutrition and Drafting of the manuscript: Yamamoto, Mezawa.

Metabolic Medicine, Center for Preventive Medical Critical review of the manuscript for important

Published Online: September 18, 2023. Sciences, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan (Sakurai); intellectual content: All authors.

doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3643 Department of Bioenvironmental Medicine, Statistical analysis: Yamamoto, Mezawa.

Open Access: This is an open access article Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Administrative, technical, or material support:

distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License. Chiba, Japan (Mori). Mezawa, Sakurai.

© 2023 Yamamoto M et al. JAMA Pediatrics. Author Contributions: Dr Yamamoto had full Study supervision: Mezawa, Mori.

Author Affiliations: Department of Sustainable access to all of the data in the study and takes Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Health Science, Center for Preventive Medical responsibility for the integrity of the data and the Funding/Support: This study was funded by the

Sciences, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan accuracy of the data analysis. Japanese Ministry of the Environment.

(Yamamoto, Mori); Medical Support Center for Study concept and design: Yamamoto, Mezawa.

Japan Environment and Children’s Study, National Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data:

E6 JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 (Reprinted) jamapediatrics.com

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age Original Investigation Research

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funder had no meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(7):665-675. 25. Adani S, Cepanec M. Sex differences in early

role in the design and conduct of the study; doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0327 communication development: behavioral and

collection, management, analysis, and 11. Zhao J, Yu Z, Sun X, et al. Association between neurobiological indicators of more vulnerable

interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or screen time trajectory and early childhood communication system development in boys. Croat

approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit development in children in China. JAMA Pediatr. Med J. 2019;60(2):141-149. doi:10.3325/cmj.2019.

the manuscript for publication. 2022;176(8):768-775. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics. 60.141

Group Information: A complete list of the 2022.1630 26. Fenske SJ, Liu J, Chen H, et al. Sex differences

members of the Japan Environment and Children’s 12. McArthur BA, Hentges R, Christakis DA, in resting state functional connectivity across the

Study Group appears in Supplement 2. McDonald S, Tough S, Madigan S. Cumulative social first two years of life. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2023;60:

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions of this risk and child screen use: the role of child 101235. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2023.101235

article are solely the responsibility of the authors temperament. J Pediatr Psychol. 2022;47(2):171-179. 27. Kushima M, Kojima R, Shinohara R, et al; Japan

and do not represent the official views of the doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsab087 Environment and Children’s Study Group.

Japanese Ministry of the Environment. 13. Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Maternal Association between screen time exposure in

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 3. characteristics and perception of temperament children at 1 year of age and autism spectrum

associated with infant TV exposure. Pediatrics. disorder at 3 years of age: the Japan Environment

Additional Contributions: We express our and Children’s Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):

gratitude to all Japan Environment and Children’s 2013;131(2):e390-e397. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1224

384-391. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5778

Study participants, their families, and the 14. Sugawara M, Matsumoto S, Murohashi H, Sakai

cooperating health care professionals. A, Isshiki N. Trajectories of early television contact 28. Slobodin O, Heffler KF, Davidovitch M. Screen

in Japan: relationship with preschoolers’ media and autism spectrum disorder: a systematic

REFERENCES externalizing problems. J Child Media. 2015;9(4): literature review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(4):

453-471. doi:10.1080/17482798.2015.1089298 303-311. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000654

1. Slomski A. Chronic mental health issues in

children now loom larger than physical problems. 15. Radesky JS, Silverstein M, Zuckerman B, 29. Kawamoto T, Nitta H, Murata K, et al; Working

JAMA. 2012;308(3):223-225. doi:10.1001/jama.2012. Christakis DA. Infant self-regulation and early Group of the Epidemiological Research for

6951 childhood media exposure. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5): Children’s Environmental Health. Rationale and

e1172-e1178. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2367 study design of the Japan environment and

2. Houtrow AJ, Larson K, Olson LM, Newacheck children’s study (JECS). BMC Public Health. 2014;14:

PW, Halfon N. Changing trends of childhood 16. Radesky JS, Peacock-Chambers E, Zuckerman 25. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-25

disability, 2001-2011. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):530- B, Silverstein M. Use of mobile technology to calm

538. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0594 upset children: associations with social-emotional 30. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG,

development. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):397-399. et al; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the

3. Strasburger VC, Hogan MJ, Mulligan DA; Council Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

on Communications and Media. Children, doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4260

(STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med.

adolescents, and the media. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5): 17. Madigan S, Browne D, Racine N, Mori C, Tough 2007;4(10):e297. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040297

958-961. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2656 S. Association between screen time and children’s

performance on a developmental screening test. 31. Squires J, Twombly E, Bricker D, Potter L. ASQ-3

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. American User’s Guide. Brookes Publishing; 2009.

Academy of Pediatrics announces new JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):244-250. doi:10.1001/

recommendations for children’s media use. jamapediatrics.2018.5056 32. Mezawa H, Aoki S, Nakayama SF, et al.

Accessed July 18, 2023. https://dnr.vnr1.com/wp- 18. Neville RD, McArthur BA, Eirich R, Lakes KD, Psychometric profile of the ages and stages

content/uploads/2016/10/PR-Media-Use-FINAL- Madigan S. Bidirectional associations between questionnaires, Japanese translation. Pediatr Int.

101216.pdf screen time and children’s externalizing and 2019;61(11):1086-1095. doi:10.1111/ped.13990

5. World Health Organization. Guidelines on internalizing behaviors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 33. Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, et al. The

physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for 2021;62(12):1475-1484. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13425 performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and

children under 5 years of age. Accessed July 18, 19. Nelson CA, Bosquet M. Neurobiology of fetal K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J

2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/ and infant development: implications for infant Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(3):152-158. doi:10.

311664 mental health. In: Zeanah CH, ed. Handbook of 1002/mpr.257

6. McArthur BA, Volkova V, Tomopoulos S, Infant Mental Health. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; 2000: 34. Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, Grasman RPPP.

Madigan S. Global prevalence of meeting screen 37-59. A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol

time guidelines among children 5 years and 20. Johnson MH. Functional brain development in Methods. 2015;20(1):102-116. doi:10.1037/a0038889

younger: a systematic review and meta-analysis. humans. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(7):475-483. doi: 35. Chen FF. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes

JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):373-383. doi:10.1001/ 10.1038/35081509 to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ

jamapediatrics.2021.6386 21. Delagneau G, Twilhaar ES, Testa R, van Veen S, Modeling. 2007;14(3):464-504. doi:10.1080/

7. Aishworiya R, Magiati I, Phua D, et al. Are there Anderson P. Association between prenatal maternal 10705510701301834

bidirectional influences between screen time anxiety and/or stress and offspring’s cognitive 36. Mulder JD, Hamaker EL. Three extensions of

exposure and social behavioral traits in young functioning: a meta-analysis. Child Dev. 2023;94 the random intercept cross-lagged panel model.

children? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2022;43(6):362-369. (3):779-801. doi:10.1111/cdev.13885 Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 2021;28(4):638-648.

doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000001069 22. Madigan S, Oatley H, Racine N, et al. A doi:10.1080/10705511.2020.1784738

8. Alroqi H, Serratrice L, Cameron-Faulkner T. The meta-analysis of maternal prenatal depression and 37. Orth U, Meier LL, Bühler JL, et al. Effect size

association between screen media quantity, anxiety on child socioemotional development. J Am guidelines for cross-lagged effects. Psychol Methods.

content, and context and language development. Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(9):645- Published online June 23, 2022. doi:10.1037/

J Child Lang. 2022;27:1-29. doi:10.1017/ 657.e8. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.012 met0000499

S0305000922000265 23. Kingston D, McDonald S, Austin MP, Tough S. 38. Statistics and Information Department. Outline

9. Eirich R, McArthur BA, Anhorn C, McGuinness C, Association between prenatal and postnatal of the fourth longitudinal survey of newborns in the

Christakis DA, Madigan S. Association of screen psychological distress and toddler cognitive 21st century. Accessed July 18, 2023. https://www.

time with internalizing and externalizing behavior development: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015; mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/

problems in children 12 years or younger: 10(5):e0126929. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126929 newborns4th/index.html

a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 24. Weissman MM. Children of depressed 39. Common Sense. The Common Sense census:

Psychiatry. 2022;79(5):393-405. doi:10.1001/ parents—a public health opportunity. JAMA media use by kids age zero to eight. Accessed July

jamapsychiatry.2022.0155 Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):197-198. doi:10.1001/ 18, 2023. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/

10. Madigan S, McArthur BA, Anhorn C, Eirich R, jamapsychiatry.2015.2967 sites/default/files/research/report/csm_

Christakis DA. Associations between screen use and zerotoeight_fullreport_release_2.pdf

child language skills: a systematic review and

jamapediatrics.com (Reprinted) JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 E7

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

Research Original Investigation Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age

40. Law EC, Han MX, Lai Z, et al. Associations Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020011429. doi:10.1542/ 49. Lauricella AR, Wartella E, Rideout VJ. Young

between infant screen use, electroencephalog- peds.2020-011429 children’s screen time: the complex role of parent

raphy markers, and cognitive outcomes. JAMA 45. Moreno MA, Furtner F, Rivara FP. Advice for and child factors. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2015;36:11-17.

Pediatr. 2023;177(3):311-318. doi:10.1001/ patients: reading to children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2014.12.001

jamapediatrics.2022.5674 Med. 2012;166(11):1080. doi:10.1001/2013. 50. Baldwin J, Arundell L, Hnatiuk JA. Associations

41. Brown A; Council on Communications and jamapediatrics.412 between the neighbourhood social environment

Media. Media use by children younger than 2 years. 46. Radesky J, Christakis D; Council on and preschool children’s physical activity and

Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1040-1045. doi:10.1542/peds. Communications and Media. Media and young screen time. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1065.

2011-1753 minds. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162591. doi:10. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13493-2

42. Christakis DA, Gilkerson J, Richards JA, et al. 1542/peds.2016-2591 51. Michikawa T, Nitta H, Nakayama SF, et al; Japan

Audible television and decreased adult words, 47. Schmidt ME, Pempek TA, Kirkorian HL, Lund Environment and Children’s Study Group. The

infant vocalizations, and conversational turns: AF, Anderson DR. The effects of background Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS):

a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. television on the toy play behavior of very young a preliminary report on selected characteristics of

2009;163(6):554-558. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics. children. Child Dev. 2008;79(4):1137-1151. doi:10. approximately 10 000 pregnant women recruited

2009.61 1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01180.x during the first year of the study. J Epidemiol. 2015;

43. Zimmerman FJ, Gilkerson J, Richards JA, et al. 25(6):452-458. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20140186

48. Sugiyama M, Tsuchiya KJ, Okubo Y, et al.

Teaching by listening: the importance of adult-child Outdoor play as a mitigating factor in the 52. Cabinet Office. Heisei 28 Survey on Internet

conversations to language development. Pediatrics. association between screen time for young children usage environment among youth. Accessed July 18,

2009;124(1):342-349. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2267 and neurodevelopmental outcomes. JAMA Pediatr. 2023. https://www8.cao.go.jp/youth/youth-harm/

44. McArthur BA, Browne D, McDonald S, Tough S, 2023;177(3):303-310. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics. chousa/h28/net-jittai_child/pdf-index.html

Madigan S. Longitudinal associations between 2022.5356

screen use and reading in preschool-aged children.

E8 JAMA Pediatrics Published online September 18, 2023 (Reprinted) jamapediatrics.com

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/16/2023

You might also like

- Kirschen2000 - The Royal London Space Planning - Part 1Document8 pagesKirschen2000 - The Royal London Space Planning - Part 1drgeorgejose7818100% (2)

- Vinegar Business PlanDocument16 pagesVinegar Business Plantucahara100% (4)

- Second Year Post Basic B.SC NursingDocument11 pagesSecond Year Post Basic B.SC NursingKailash Nagar100% (1)

- INVESTIGATION OF THE EFFECT OF NeuROPLAY METHOD ON DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESSES OF CHILDREN WITH AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS AND PARENTAL INTERACTIONSDocument20 pagesINVESTIGATION OF THE EFFECT OF NeuROPLAY METHOD ON DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESSES OF CHILDREN WITH AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS AND PARENTAL INTERACTIONSGlobal Research and Development Services100% (1)

- Nugraha 2019 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1175 012203Document7 pagesNugraha 2019 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1175 012203Chinny GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Watching Television - PDF 1Document9 pagesWatching Television - PDF 1albert AungNo ratings yet

- Examining The Efficacy of Dance Movement and Music Mixed Treatment On Social Communication Impairment in Children With Autism - Based On Family Parent-Child SituationDocument10 pagesExamining The Efficacy of Dance Movement and Music Mixed Treatment On Social Communication Impairment in Children With Autism - Based On Family Parent-Child Situation賴莙儒No ratings yet

- Paper+21+ (2022 3 4) +The+Relationship+between+Family+Function+and+Emotional+Mental+ProblemsDocument6 pagesPaper+21+ (2022 3 4) +The+Relationship+between+Family+Function+and+Emotional+Mental+ProblemsWinonaNo ratings yet

- Online CasebookDocument7 pagesOnline Casebookapi-467593876No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0387760422001383 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0387760422001383 Main賴莙儒No ratings yet

- Template Submit Jurnal UIDocument9 pagesTemplate Submit Jurnal UIsarah fitriaNo ratings yet

- Screen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep DurationDocument10 pagesScreen Time and Problem Behaviors in Children: Exploring The Mediating Role of Sleep Durationdwi putri ratehNo ratings yet

- Screen Media Exposure in The First 2 Years of Life and Preschool Cognitive Development - A Longitudinal StudyDocument9 pagesScreen Media Exposure in The First 2 Years of Life and Preschool Cognitive Development - A Longitudinal StudyLucía PiñeiroNo ratings yet

- Screen Time ChildDocument11 pagesScreen Time ChildTere NavaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between The Duration of Playing Gadget and Mental Emotional State of Elementary School StudentsDocument4 pagesThe Relationship Between The Duration of Playing Gadget and Mental Emotional State of Elementary School StudentsNurul Fatehah Binti KamaruzaliNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument6 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-537096690No ratings yet

- Knowledge Towards Childhood Immunization Among Mothers & Reasons For Incomplete ImmunizationDocument5 pagesKnowledge Towards Childhood Immunization Among Mothers & Reasons For Incomplete ImmunizationAbdulphatah Mohamed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Mentoring Program To Eradicate Malnutrition On Changes in The Nutritional Status of Stunting ToddlersDocument8 pagesMentoring Program To Eradicate Malnutrition On Changes in The Nutritional Status of Stunting ToddlersNIKENNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document38 pagesChapter 1aprilstamaria0427No ratings yet

- The Dominant Factors of Stunting Incidence in Toddlers (0 - 59 Months) in East Lombok Regency A Riskesdas Data Analysis 2018Document11 pagesThe Dominant Factors of Stunting Incidence in Toddlers (0 - 59 Months) in East Lombok Regency A Riskesdas Data Analysis 2018International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Preschool Developmental Screening With Denver II Test in Semi-Urban AreasDocument4 pagesPreschool Developmental Screening With Denver II Test in Semi-Urban AreasNurul Mukhlisah IsmailNo ratings yet

- Stunting, BMJDocument10 pagesStunting, BMJGiga HasabiNo ratings yet

- Xu, Tully, Dadds, 2024Document10 pagesXu, Tully, Dadds, 2024MissDSKNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Physical Activity in Middle ChildhooDocument8 pagesPredictors of Physical Activity in Middle ChildhooHellen SantosNo ratings yet

- A Low-Cost Method For Understanding How Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Impacts Children's Health and WellbeingDocument15 pagesA Low-Cost Method For Understanding How Nature-Based Early Learning and Childcare Impacts Children's Health and WellbeingRevielyn RoseNo ratings yet

- Par Page 2 MilieuDocument4 pagesPar Page 2 Milieuapi-261120104No ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Effective Strategies For Reducing Screen Time Among Young ChildrenDocument17 pagesSystematic Review of Effective Strategies For Reducing Screen Time Among Young ChildrenAdrienn MatheNo ratings yet

- Budiana 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 180 012194Document5 pagesBudiana 2017 IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 180 012194Syifa Lidiani PutriNo ratings yet

- Carolina Marpaung - Maurits K. A. Van Selms - Frank LobbezooDocument8 pagesCarolina Marpaung - Maurits K. A. Van Selms - Frank LobbezooMarco Saavedra BurgosNo ratings yet

- Protective Effects of Parental Monitoring of Children's Media Use A Prospective StudyDocument6 pagesProtective Effects of Parental Monitoring of Children's Media Use A Prospective StudyJavier AlegriaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Screen Timing On ChildrenDocument7 pagesEffects of Screen Timing On ChildrenWarengahNo ratings yet

- Artigo 4Document15 pagesArtigo 4Ana Júlia alvesNo ratings yet

- Collage pr1Document5 pagesCollage pr1Maria Carmina Beroin VegaNo ratings yet

- OA UNBRAH 1260-4244-2-SM Rana Atikah, Sri Pandu UtamiDocument5 pagesOA UNBRAH 1260-4244-2-SM Rana Atikah, Sri Pandu UtamipanduutamidrgNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors Associated With Childhood Stunting in Indonesia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesRisk Factors Associated With Childhood Stunting in Indonesia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysisdhiyaa ulhaq amatullahNo ratings yet

- Extracts For EssayDocument4 pagesExtracts For EssayLayane S ELamineNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Pediatric Arienda Cahyani - 12100119041Document3 pagesJurnal Pediatric Arienda Cahyani - 12100119041Arienda AkiliNo ratings yet

- Triple P Dropout SurveyDocument14 pagesTriple P Dropout SurveytrisNo ratings yet

- Association of Screen Time Use and Language Development in Hispanic Toddlers A Cross Sectional and Longitudinal StudyDocument9 pagesAssociation of Screen Time Use and Language Development in Hispanic Toddlers A Cross Sectional and Longitudinal StudykeychainalbumNo ratings yet

- Asociacion Pantallas TEADocument8 pagesAsociacion Pantallas TEAsusanaelisabetNo ratings yet

- Emotional and Behavioural Issues of Students When Exposed To Long-Period Screen Time Due To Online ClassesDocument9 pagesEmotional and Behavioural Issues of Students When Exposed To Long-Period Screen Time Due To Online Classesemm morNo ratings yet

- Toxic Stress Health and Nutrition Among Brazilian Children in shelters2021BMC PediatricsOpen AccessDocument8 pagesToxic Stress Health and Nutrition Among Brazilian Children in shelters2021BMC PediatricsOpen AccessJuan David Bermúdez 21No ratings yet

- Kaperwn - Hasnidar@gmail.c Om: Hasnidar, Sukrang, Fauzan, Munir.,M.A/ Comprehensive Health Care Vol 7, No 3 December 2023Document9 pagesKaperwn - Hasnidar@gmail.c Om: Hasnidar, Sukrang, Fauzan, Munir.,M.A/ Comprehensive Health Care Vol 7, No 3 December 2023Kang EditNo ratings yet

- Bjophthalmol 2019 315636.full PDFDocument7 pagesBjophthalmol 2019 315636.full PDFothilia.obadaNo ratings yet

- PCST AsdDocument8 pagesPCST Asd409530315fjuNo ratings yet

- 48 Aktsa Original 12 3Document10 pages48 Aktsa Original 12 3alifia shafa s psiNo ratings yet

- Does Viewing Television Affect The Academic Performance of ChildrenDocument5 pagesDoes Viewing Television Affect The Academic Performance of ChildrenCastolo Bayucot JvjcNo ratings yet

- J Jfludis 2021 105843Document21 pagesJ Jfludis 2021 105843ANDREA MIRANDA MEZA GARNICANo ratings yet

- Breastfeeding and Risk of Febrile Seizures in Infants The - 2019 - Brain and deDocument9 pagesBreastfeeding and Risk of Febrile Seizures in Infants The - 2019 - Brain and deSunita ChayalNo ratings yet

- Child Friendly ApproachDocument6 pagesChild Friendly ApproachFikih Diah KusumasariNo ratings yet

- Oral Defense in ResearchDocument35 pagesOral Defense in ResearchNovelyn CapondagNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Screen Time On The Sleep Quality of Senior High School Students in Centro Escolar Las PiñasDocument58 pagesThe Effects of Screen Time On The Sleep Quality of Senior High School Students in Centro Escolar Las Piñasbis coNo ratings yet

- Computers in Human BehaviorDocument12 pagesComputers in Human BehaviorZhang PeilinNo ratings yet

- 2023 Qu EnfantstroublesdvptDocument10 pages2023 Qu EnfantstroublesdvptWil HelmNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Parent Engagement in DIR/Floortime For Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument9 pagesFactors Associated With Parent Engagement in DIR/Floortime For Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderSantiagoDavidSuárezNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1064461Document17 pagesNihms 1064461api-548614976No ratings yet

- Ejhs3203 0569Document10 pagesEjhs3203 0569ERNINo ratings yet

- Child NeurologyDocument5 pagesChild NeurologymhabranNo ratings yet

- Parental Time of Returning Home From Work and Child Mental Health Among First-Year Primary School Students in Japan: Result From A-CHILD StudyDocument10 pagesParental Time of Returning Home From Work and Child Mental Health Among First-Year Primary School Students in Japan: Result From A-CHILD StudySamanwita LalaNo ratings yet

- Screen Time - Implications For Early Childhood Cognitive Development - ScienceDirectDocument5 pagesScreen Time - Implications For Early Childhood Cognitive Development - ScienceDirectJoana MauricioNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude of Sikkim Primary School Teachers About Paediatric Hearing LossDocument6 pagesKnowledge, Attitude of Sikkim Primary School Teachers About Paediatric Hearing LossMaria P12No ratings yet

- Efek HP Terhadap Kualitas TidurDocument9 pagesEfek HP Terhadap Kualitas TidurKaroniNo ratings yet

- Parental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and PractitionersFrom EverandParental Monitoring of Adolescents: Current Perspectives for Researchers and PractitionersNo ratings yet

- Gercio vs. Sun Life Assurance Co of CanadaDocument4 pagesGercio vs. Sun Life Assurance Co of CanadaGlendalyn PalacpacNo ratings yet

- A Lover's Discourse Byblis in Metamorphoses 9Document28 pagesA Lover's Discourse Byblis in Metamorphoses 9ΔήμητραNo ratings yet

- C32400 PDFDocument76 pagesC32400 PDFjeffer rojasNo ratings yet

- Ultra Tech CementDocument14 pagesUltra Tech CementRaunak Doshi71% (14)

- LoboHernandezySaldamandoBenjumea2012 PDFDocument167 pagesLoboHernandezySaldamandoBenjumea2012 PDFLeandro RodríguezNo ratings yet

- 333 Obooko thr0019Document507 pages333 Obooko thr0019ripak_debnathNo ratings yet

- 08 Proceduri de UrgentaDocument9 pages08 Proceduri de UrgentaSorescu Radu VasileNo ratings yet

- HECAT Module AODDocument26 pagesHECAT Module AODririhenaNo ratings yet

- Honda PDFDocument20 pagesHonda PDFAyan DuttaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Shapes Fitting Together in Cells and OrganismsDocument4 pagesThe Importance of Shapes Fitting Together in Cells and Organisms17athermonNo ratings yet

- Ramadan PresentationDocument20 pagesRamadan Presentationsajid_cdNo ratings yet

- Ict - Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesIct - Lesson Planapi-249343709100% (2)

- Penguin - Magnetic Drive Pump M SeiresDocument4 pagesPenguin - Magnetic Drive Pump M SeiresMiguel Angel LòpezNo ratings yet

- KGianan-Stem12-Physics2 (Chapters 1-3)Document9 pagesKGianan-Stem12-Physics2 (Chapters 1-3)Kyle GiananNo ratings yet

- Vaping in High School StudentsDocument60 pagesVaping in High School StudentsRobby RanidoNo ratings yet

- Day 1 Exam 1Document3 pagesDay 1 Exam 1Cheng PasionNo ratings yet

- OM-UHT Plant PDFDocument138 pagesOM-UHT Plant PDFToni0% (1)

- Aplus Coating Report FormatDocument1 pageAplus Coating Report FormatNnamdi AmadiNo ratings yet

- 1.master Techniques in Surgery - Esophageal Surgery, 1E (2014)Document456 pages1.master Techniques in Surgery - Esophageal Surgery, 1E (2014)Raul Micu ChisNo ratings yet

- 01 5 CF BFDocument357 pages01 5 CF BFblaiNo ratings yet

- CL-1200i (1000P) &2600i&2800i - Service Manual - V1.0 - ENDocument803 pagesCL-1200i (1000P) &2600i&2800i - Service Manual - V1.0 - ENmanal al-hattaliNo ratings yet

- SurveyorLCPump HardwareDocument142 pagesSurveyorLCPump HardwareDinoNo ratings yet

- After Activity Report Oplan Paalala 201Document12 pagesAfter Activity Report Oplan Paalala 201Jaimee Marie PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Receta PastelDocument5 pagesReceta PastelJesus BeltranNo ratings yet

- EJMCM - Volume 7 - Issue 11 - Pages 9184-9190Document7 pagesEJMCM - Volume 7 - Issue 11 - Pages 9184-9190Akshay BeradNo ratings yet

- Bcetal - Psychedelic DrugsDocument6 pagesBcetal - Psychedelic DrugsMumuji BirbNo ratings yet

- 850 860 870 SpecDocument2 pages850 860 870 SpecJerNo ratings yet