Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Societe D'etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Societe D'etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Uploaded by

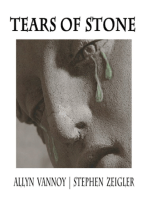

fobol47983Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Societe D'etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Societe D'etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Uploaded by

fobol47983Copyright:

Available Formats

Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Mark Antony and the Raid on Palmyra : Reflections on Appian, "Bella Civilia" V, 9

Author(s): Olivier Hekster and Ted Kaizer

Source: Latomus, T. 63, Fasc. 1 (JANVIER-MARS 2004), pp. 70-80

Published by: Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41540402 .

Accessed: 14/06/2014 15:39

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Societe d’Etudes Latines de Bruxelles is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Latomus.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Mark Antony and the Raid on Palmyra :

Reflections on Appian, Bella Civilia V, 9 (*)

'AjzojzXevoáoriçôè zfjgКХеоштдадèç та oixeïa,ó 'Avtcdvloç ёже(шеtovç

íjuiéaçnákpLvga jzófav,ov

' (iaxgàv ovaav aitòEvcpgárov, ôiangáoai, fitxgà

¡lèvèmxaXwv xai TlagOvaícov

amole;,ori Pcofiaícov ovTeçècpógioi èç éxaré-

govç èmôe^íojçei%ov(epmogoiyàg ovieç ř xo/iíÇovoi ptèvèx Tlegowvта

'Ivôixà fj 'Agäßta,дсапвеутасó èv Tfj Pœfiaicov ), egycoó èmvoœvtovç

ijtjïéaçjzegiovoiáoai.naXfivgr]vã)vôè Jtgo^aOóvTcov xai rà âvayxaíaèç то

Jtégav TovnoTajiov/isTeveyxávTcov те xai èjzi TfjçoxOtíç, et tiç èm%eigoír'

oxevaoafxévœv a

tóÇoiç,ngòç JieyvxaoLv oi

è^aigéTouç, ÍTCJtéeç ttjvJtókiv

xevrjv Teç

xaTakaßov шёотдеграу, orne èç gaç èkQóvTeç orne ti XafióvTeç.

Translation : «WhenCleopatra hadsailedhomewards, Antony senthishorsemen to

thepolisPalmyra, notfarfrom theEuphrates, toplunder, accusing them ofsome-

thing thatthey- beingonthefrontier

insignificant, between theRomansandthe

Parthians - showedtactto bothsides(beingmerchants, theycarryIndianand

Arabian goodsfrom thePersiansandtheydisposeofthemintheterritory ofthe

Romans), butinfacthehadinhismindtoenrich hishorsemen. As thePalmyrenes

learned aboutthisbeforehand andcarried theiressentialstotheother sideofthe

riverandtotheriverbank, preparingthemselves with bows - withwhich theyare

by nature -

excellent incase anyonewould attackthem, the horsemen, seizingthe

cityempty, turnedaround,nothaving metanyone, nothaving takenanything» (').

The passageis well-known. As one ofthefewliterary sourceson pre-Roman

Palmyra, scholars on

working Palmyra have used it extensively.Similarly,

historians

focussingon MarkAntony'sEasternmilitary policyin thetriumviral

periodhave drawnfar-reaching conclusionsfromthe episode. But textsare

rarelyunambiguous, and thispassage is no exception.The aim of thepresent

(*) Manythanks toLukePitcher forhiscomments ona draftofthispaper,

andforpro-

vidingus withuseful

references.

(1) TextfollowingLCL. In 1996a newannotated Penguin translation

byJohn Carter

hasappeared , theCivilWars

(Appian , London)anda newedition ofthebooksonthecivil

warsbyKai Brodersen is in preparation forOxfordClassicalTexts. no

Unfortunately,

majorgeneralinterpretationofAppianexistsyet.ValuableareB. Goldman, Einheit-

lichkeit

undEigenständigkeitderHistoria RomanadesAppian - New-

, Hildesheim York,

1988andthearticlesbyК. Brodersen andI. Hahn- G. Németh,ANRWU34.Ì,1993.Of

importancewillalsobe L. Pitcher,TheHistorio graphical

Techniques ofAppian, forth-

coming. On 'CivilWars': E. Gabba,Appianoe la storiadelleguerre civili

, Florence,

1956; D. Magnino,Le "Guerre Civili" diAppianoinANRW 11.34.1,1993,p. 523-554.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MARK ANDTHERAIDONPALMYRA

ANTONY 71

contribution

is twofold.Firstly, thatneitherof the

we set out to demonstrate

above-mentioned of

applications the is

passage unproblematic : thepassage is

sometimesincompatible withexternalsources, sometimes sole supportfora

claim,and in generalnotas strongevidenceas assumed.Secondly,it will be

arguedthatlookingat thepassagein bothitsliterary

and historical contextnot

onlyhighlightssomeoftheseveryproblems, butmayalso explainthem.

Thepassage and modernhistoriography : Palmyra.- The mainconclusions

thatscholarshave drawnfromthispassage aboutthe pre-Romanhistoryof

Palmyraare thattheplace was richenoughin 41 ВС to attract theattentionof

potential and

pillagers, that must

Palmyra therefore have been a relatively

pros-

perous'caravan'cityby thisearlydate(2). In addition,thepassagehas someti-

mes been connectedwithan alleged 'nomadic'natureof the inhabitants of

Palmyra in themid-first ВС

century (3). Our further

evidence,however, does not

(2) I. Richmond, Palmyra undertheaegisofRomeinJRS53, 1963,p. 44 : 'itsmer-

cantilewealth,alreadyfamous'; H. Bengtson,MarcusAntonius : Triumvir und

Herrscher des Orients , Munich,1977,p. 164: 'die reicheHandelsstadt Palmyra' ;

H. J.W.Drijvers, Hatra,Palmyra undEdessa.Die Städtedersyrisch-mesopotamischen

Wüsteinpolitischer, kulturgeschichtlicher undreligionsgeschichtlicher Beleuchtung in

AM?WII8, 1977,p. 838: 'daßPalmyra damalsschondenRufeinerreichen Stadtgehabt

hať ; J.Matthews, TheTaxLawofPalmyra : Evidence forEconomic Historyina Cityof

theRomanEast in JRS74, 1984,p. 161: 'its alreadyfabulous mercantilewealth';

E. Will,Plinel'ancienetPalmyre : unproblème d'histoireou d'histoire ? in

littéraire

Syria 62, 1985, p. 268 : 'une république demarchands' ; Id.,Les Palmyréniens. La Venise

dessables,Paris,1992,p. 35 : 'assezrichepourêtrepillée'; E. Frézouls,Palmyre etles

conditions politiques dudéveloppement de sonactivité commerciale inAAAS42, 1996,

p. 149: 'Palmyre avaitdéjàà la findel'époquehellénistique d'uncentre

le profil actifet

capabled'accumuler des richesses' ; L. Dirven,ThePalmyrenes ofDura-Europos. A

Study ofReligious Interaction inRomanSyria , Leiden,1999,p. 19: 'already wealthy in

thosedays'; E. Savino,Cittàdifrontiera nell'Impero romano. Formedellaromanizza-

zioneda Augusto ai Severi , Bari,1999,p. 52 : 'una certafamadi cittàprospera' ;

G. Degeorge,Palmyre, métropole caravanière , Paris,2001, p. 68 : 'suffisamment

prospère' ; M. Sartre,D'Alexandre à Zénobie. HistoireduLevant antique,ivesiècleav.

J.-С. - uiesiècleар. J.-С.,Paris,2001,p. 843: 'déjàrichelorsduraidde MarcAntoine

en41 av.J.-C.',andcf.ibid.,p.464andp.496.ButseeH. Seyrig, Palmyra andtheEast

inJRS40, 1950,p. 1 : 'notyetoverburdened withluxuries' andB. Isaac,TheLimits of

Empire, Oxford,19922,p. 141-2: 'thecity'swealthwill haveconsisted of bullion,

coinage, andlivestock' .

(3) G. K.Young, Rome'sEastern Trade. International Commerce andImperial Policy,

31 ВС -AD 305,London- NewYork,2001,p. 136: 'Intheseearlyyearsitappears that

theinhabitants oftheoasiswerestillsemi-nomadic, as Appianstates thattheywereable

toremove all theirmaterial wealthacrosstheEuphrates whenAntony attackedthemin

42 (sic)ВС'. Cf.Will,LesPalmyréniens [п.2],p. 36 : 'quelquechoseencore comme un

campement de Bédouins'; Isaac,Limits ofEmpire[п. 2', p. 142: 'thePalmyrene res-

ponsetotheRomanattack wasstillthatofnomads facinga forceofsuperior strength';

Savino,Cittàdifrontiera [п.2],p. 52 : 'ancoraprossimi allostatonomade'. Butseenow

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

72 O. HEKSTER

& T. KAIZER

allow us to speak withmuchcertainty aboutthepre-Romanperiod.Polybius

(V,79,8) mentions a commander over 'the Arabs and neighbouring tribes'

("Agaßeg ôè xaì tiveç rwv tovtolçtcqooxcoqcov) inAntiochus Ill's armyatthe

battleofRaphia,whohas a typically Palmyrene name,Zabdibelus,butthisdoes

notnecessarilysuggestthatPalmyraas a place was of greatimportance in the

pre-Romanperiod(4). JosephusarguesthatSolomonbuiltPalmyra'withvery

strongwalls', butin doingso he follows2 Chronicles8,4, wheretheoriginal

'Tamarin thedesert'(as used in 1 Kings9, 18) is interpreted as 'Tadmorin the

desert'. The statement byJosephus shouldtherefore notbe takenatfacevalue(5).

His near-contemporary Pliny,whoappearsto givea geographical description of

Palmyraanditssurroundings in themid-first century AD ( HN V,88),providesa

notionalperception of whatan oasis oughtto be like,ratherthanfactualinfor-

mationbasedon first-hand knowledge, andin anycase does nottellus anything

aboutthelateRepublic(6).

We are notsuggesting thattherewas notsome sortof permanent settlement

in 41 ВС, regardless of whether Appian's word choice (jzófaç) is adequate.The

earliest dated inscriptionfrom Palmyra,writtenin the local Aramaic

(Palmyrenean) dialect,recordstheerection ofa statuein44 ВС bythepriesthood

of Bel, which was to become one of the most prominentinstitutions in

Palmyrene society until thecity'scapture in AD 272 (7).It is also well known that

thetempleof Bel as it is stillstandingnowadayswas precededby an earlier

structure,or earlierstructures, andrecentbutstillunpublished soundingsin the

temenosby Syrianarchaeologists may have revealed the first archaeological

U. Scharrer, Nomaden undSeßhafte inTadmor im2. Jahrtausend v.Chr.inM. Schuol,

U. Hartmann and A. Luther(eds.),Grenzüberschreitungen. Formendes Kontakts

zwischenOrient undOkzident imAltertum 2002,p. 309: 'DerBericht

, Stuttgart, Appians

kanndemnach nicht

alsBegründung füreinenomadische Lebensweise inderOasegegen

Mittedes 1. Jahrhunderts v. Chr.herangezogen werden'.Notethesimilarities with

Diodorus'descriptionoftheNabataeans, whowhenJToXefiiœv òvvafiiçâôgà approa-

ches,(pevyovOLv eíç rrjvедщоу, whichservesthemas a fortress (ramrjxQÚ/ievoi

oxvgcbiian) (DiodorusSiculusXIX,94).

(4) On thenameof 'Zabdibelus' at Palmyra, see J.K. Stark,PersonalNamesin

Palmyrene , Oxford,

Inscriptions 1971,p. 85.

(5) Josephus,Ant.VIII,6, 1 (153-4).Cf.F. Millar,TheRoman NearEast.31 ВС-AD

337, Cambridge [MA]- London, 1993,p. 320.

(6) Will inSyria62,1985[n.2],p. 263-9.

(7) The inscriptionis D. R. Hillers and E. Cussini,Palmyrene AramaicTexts ,

Baltimore- London,1996(henceforth : PAT),no 1524(wrongly datedtoAD 44). See

nowalsoКн.al-As'adandM. Gawlikowski, TheInscriptionsintheMuseum ofPalmyra,

Palmyra- Warsaw, 1997,p. 25-26,no29,andКн.(al-) As'adandJ.-B. Yon,Inscriptions

de Palmyre,Beirut- Damascus- Amman, 2001,p. 32,no.2. On thePalmyrene priest-

hoodofBel,see nowT. Kaizer,TheReligious LifeofPalmyra, 2002,p. 229-

Stuttgart,

234.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MARK ANDTHERAIDONPALMYRA

ANTONY 73

remainsof theso-calledHellenistictempleof Bel (8). Furthermore,thepresent

archaeologicalprojectsouthofthewadi seems to confirmthat

this

largeandnow

empty area had been thecentreof early-Roman ('pre-Colonnade')andpossibly

HellenisticPalmyra(9).Butthisis as muchas archaeological materialcan indi-

cateat present.Smallfindsfromthethirdand secondmillennium ВС areinsuf-

ficientto provea culturalcontinuum fromthe BronzeAge onwards(10).The

remaining walls areby themselves difficult

to date,and anyconclusionsdrawn

fromthemare highlydebatable(n). Externalevidence,therefore, does not

contradicttheinformation providedby Appian,butit certainlydoes notprove

himrighteither.

There are even more seriousproblemswithinthe passage itself.If the

Palmyrenes wereso rich,thanhow could theyhave carriedeverything away?

Accordingto thestory, Antony'shorsemenfoundthecityempty(xevoç). But

Appianonlytalksabout 'essentials'(rà âvayxaîa) beingcarriedaway.How

emptyis a cityafteressentialsare carriedaway? Were essentialsonly the

(8) Onthetemple ofBel,seeKaizer,Religious Life[n.7],p. 67-79.TheSyrian soun-

dingsarereferred tobyE. Will,Les sallesde banquet de Palmy reetd'autreslieuxin

Topoi7, 1997,p. 873-87.See nowalsoM. al-Maqdissi, Notesurlessondagesréalisés

parRobert duMesnilduBuissondansla courdusanctuaire de Bêl à Palmyre inSyria

77,2000,p. 137-158, a recentre-examinationoftheexcavations madeinthetemenos in

the1960s.

(9) A. Schmidt-Colinet /Кн.al-As'ad,ZurUrbanistik deshellenistischenPalmyra.

Ein Vorbericht (withcontributions of H. Becker,Ch. Römerand M. Stephani)in

Damaszener Mitteilungen 12,2000,p. 61-93.The gravesbehindthetempleof Baal-

Shamin havebeendatedtothe2nd centuryВС andseemtohavebeeninusethroughout

thefirstcentury ВС. Cf. R. Fellmann, Le sanctuairede Baal-Shamîn à Palmyre5. Die

Grabanlage , Neuchâtel, 1970.

(10) On somerecent finds,seeD. Bieliñska,SmallFindsfrom Pre-classical

Palmyra

inStudiaPalmyreñskie 10,1997,p. 19-22.Cf.Scharrer, inSchuol,Grenzüberschreitun-

gen[n.3],ontablets from Mariandelsewhere.

(11) Somescholars haveargued wallsofPalmyra

thattheoriginal ought tohavepost-

dated41 ВС precisely becauseofthepassageinAppian. Theyassumethattheattempt by

Antony's horsemen toplunder theplaceimpliesthelackofa proper enclosure.See e.g.

Richmond inJRS53,1963[n.2],p.48 : 'considering whatrelativelymodest defences will

stopa cavalry force,thismustsurelybe acceptedas true',andD. vanBerchem, Le

premier rempart de Palmyre inCRAI, 1970,p. 234,referringtoAppian'sstory as provi-

dinga terminus postquemandtoPalmyra in41 thereforeas 'unevilleouverte'. Most

recentlythesameconnection is madebyDegeorge, Palmyre [n.2],p. 298n.94.Thisis

methodologically Cf.Matthews

incorrect. inJRS74,1984[n.2],p. 160; Millar,Roman

NearEast [n. 5], p. 321. For variousopinionson thedevelopment of thewallsof

Palmyra : M. Gawlikowski, Le temple palmyrénien, Warsaw, 1973,p. 12-20; id,Les

défenses de Palmyre in Syria51, 1974,p. 231-242; D. P. Crouch,TheRamparts of

Palmyrain StudiaPalmyreñskie 6, 1975, p. 6-44 (withbriefremarks made by

Gawlikowski, ibid.,p.45-46).

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

74 & T. KAIZER

O. HEKSTER

valuables? How muchcan one, logistically, carryin flightanyhow? Events

become even more confusingwhen we read where the Palmyreneswent.

Accordingto Appian,theywent'to theotherside of theriverand to theriver-

bank'.This impliesthattheEuphrateswas reasonably nearby, whereasin reali-

tyit is some 200 km away.Introducing Palmyraas not far from theriver(ov

fiaxgàvovoav áno EvcpQÓrov), theauthor'stopographicalknowledge doesnot

seemto be entirely accurate(12).It shouldalso be notedthatAppiandoes not

writethatPalmyrawas a caravancityin Antony'stime.He explicitly uses the

presenttense: efjjcogoi... ovreç xofiíÇovoi...(13).As we will suggestbelow,

thismaywellbe significant.

Thepassage and modernhistoriography : Antonyand theEast - Usingthepas-

to

sage analysepre-Roman has

Palmyra provedhighlyproblematic. Coulditstill

haveramifications forAntony'sEasternpolicyin thepost-Philippi period? That

of

policyis, course, of substantialimportance forourunderstanding ofthestrug-

gle for power between Octavian and Antony, and of the eventual East-West

dichotomy thatso characterised theevents and found reflections in so manyof

oursources.Antony'sraidon Palmyra has indeedbeen perceived in thiscontext,

althoughleadingto divergent conclusions.Some authorshave arguedstrongly

thatby mounting an attackon Palmyra, Antonywas trying to establishcontrol

over the surrounding area as a whole,possiblyto preparethe groundfora

Parthian campaign(14).ButAppian'spassagehas also beeninvokedto 'prove'the

oppositepointofview.The raidon Palmyrathenservesas an attempt byAntony

to establisha 'buffer-zone'to limittheeffectsof an almostinevitableParthian

(12) Notedby Millar, RomanNearEast [n.5], p. 321. Contrast J.Vanderleest,

Appian's References tohisOwnTimeinAHB3, 1989,p. 132: 'Itis clearfrom Appian's

Preface thathehada strong senseofgeography Butseefurther geographical blun-

dersas notedbyP.Janni, La mappae ilperiplo: cartografia anticae spazioodologico ,

Rome,1984,p. 114: 'ignorantissimo de geografia';A. M. Gowing, The Triumvirat

NarrativesofAppianandCassiusDio, AnnArbor, 1992,appendix 4 ; J.S. Richardson,

Appian: WarsoftheRomans inIberia, Warminster,2000,p. 5-6.

(13) Already Isaac,Limits ofEmpire [n.2],p. 141; Millar,Roman NearEast[n.5],

p. 321.

(14) A. Baldini, Romae Palmira : notestorico-epigraphiche

inEpigraphica 36,1974,

p. 109-133,esp.p. 111-113.Baldini's argumentthatthePalmyrenes probably retreated

to

Dura-Europos (p. 112) seemshighly doubtful.

Moresensemakeshiscombination of

Appian, ВС V,9 withCicero, AdEarn.XV,1,2,which mentions a possibleattack onTyba

(Taybek).Baldinisuggests thatthisindicatesanattempt byAntony tobring theentirearea

underhiscontrol. Similarly,C. Pelling,TheTriumval Periodin САНIO2,1996,p. 12

argues: 'During41 Antony hadprobably beenpreparing foran offensive waragainst

Parthia- bytheendoftheseasonhehadindeedtaken theborder townofPalmyra'. Cf.

К.-H.Ziegler,Die Beziehungen zwischen RomunddemPartherreich. EinBeitrag zur

GeschichtedesVölkerrechts , Wiesbaden, 1964,p. 32-36.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MARK ANDTHERAIDONPALMYRA

ANTONY 75

offensive one couldevensee Antony'sactionagainstPalmyra

(15).Alternatively,

in thecontextof his normalmilitary activities

as governor (I6).If a passagecan

be usedin defenceofseveraloppositeviewpoints, itdoes notproveanyofthem.

In short,one needsto be cautiouswhendrawinganyconclusionsfromthispas-

sage.

Literaryand historicalcontextof thepassage. - Fromthe sack of Palmyra,

Appiancontinueshis narrative by recountingfurther detailson theoutbreakof

theParthian War(ВС 5,10),beforehe returns to Octavianin Italy(ВС 5,12ff.).

This seemsto strengthen thecase forthosewho wantto emphasisetheimpor-

tanceof theraidon Palmyrain Antony'sEasternpolicy(17).Yet,cannotliterary

considerations, morethanAntony'sperceivedgoals,haveinfluenced Appianin

hiswriting ? In whatfollows,we aimto showthattakingintoaccountbothlite-

rarytopoiandAppian'sbias can further clarifythepassage.Let us, withthisin

mind, first look at what instantlyprecedesthe sack of Palmyrain Appian's

account:

«So straight

awaytheattentionthatAntony haduntilnowdevoted

toevery matter

wascompletely andwhatever

blunted, commanded

Cleopatra wasdone,without

consideration

ofwhatwasright intheeyesofmanorgod.OnAntony's ordersher

sisterArsinoé,whohad takenrefugeas a suppliant at thetempleof Artemis

Leukophryene inMiletus,

wasputtodeath, andheordered tosurrender

theTyrians

Serapiontoher,whoas hercommander inCyprus hadsupportedCassiusbutwas

nowa suppliant thepeopleofAradustohandoveranother

inTyre.He instructed

some

suppliant, man whom they wereharbouringandmaking outtobe Ptolemy,

afterthedisappearance

ofCleopatra'sbrotherPtolemyinthenavalbattleagainst

(15) H. Bengtson, MarcusAntonius : TriumvirundHerrscher derOrients , Munich,

1977,p.158: 'Die Maßnahmen imOrient... sind... demMotivderFurcht voreiner

möglichen parthischeIntervention entsprochen'. Cf.H. Buchheim, Die Orientpolitikdes

Triumvirs M.Antonius , Heidelberg,1960,p. 28.

(16) L. Craven, Antony's OrientalPolicyuntiltheDefeatoftheParthian Expedition,

Columbia, 1920,p. 27-28,establishing a conjecturalrouteof thetouras : 'Ephesus,

Smyrna,Sardis,Magnesia,Pergamom, Adramyttium, Cyzicus,Nicaea, Ancyra,

Pessinum, Synnada, Icanium,Cybistra, Tyana,Tarsus,Antioch, Laodicea,Apamea,

Epiphania, fromwhicha cavalry expedition was sentto Palmyra, Damascus, through

Iturea, acrossPalestine to thecoastandthenceto Egypt'.Pellingin САНIO2,1996

[п. 14],p. 11 withп. 32 seesmostofAntony's touras 'beginning toreorganizetheadmi-

nistration after

thedisruption ofthewar', though heplacesthemeasures againstPalmyra

in a different context [supran. 14].Examplesof governor's dutiesthatMarkAntony

undertook alongtheway: Plutarch, Ant.XXIII,26,58 ; Appian, ВС V,7 ; StraboXIV,

5, 14.See ontheroleofgovernors, esp.J.Richardson, Roman ProvincialAdministration.

227 ВС toAD 117, Bristol, 19842,p. 27-46; A. Lintott,Imperium Romanům. Politics

andAdministration , London- NewYork,1993,p. 43-69.

(17) F. Chamoux, MarcAntoine : dernierprincede l'Orient grec, Paris,1986,p. 247-

8 ; С. В. R. Pelling,Putarch, LifeofAntony, Cambridge etal., 1998,p. 193(on28.1).

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

76 & T. KAIZER

O. HEKSTER

CaesarontheNile.He alsoorderedthepriestofArtemisatEphesus,

whomthey

callMegabyzus,tobebrought him,becausehehadoncewelcomed

before Arsinoé

himwhentheEphesians

as queen,butreleased pleadedwithCleopatra

herself.

So

swiftlywasAntony andthispassionwasthebeginning

transformed, andtheendof

evilsthatafterwards him(omco¡lèvó 'Avtcúvioç

befell êvrjXkaxio

mxécoç,xaí то

av

jtáOoç тф Tomo noi

âgxv TéXoç rcõvелеltoi

xaxœv eyévew)»(18).

Appian,itappears,recounts thesackofPalmyraas thebeginning 'oftheevils

thatafterwards befell'Antony.In otherwords,thefruitless attackon Palmyra,

whichresultedin nothingand antagonised theParthians,can be seen as one of

thoseexamplesofchangesin fortune thatancienthistoriographywas so fondof.

A similareventtakesplace in Plutarch, LifeofCrassus17. In 54 ВС, at theout-

setof whatwouldturnoutto be sucha disastrous Easterncampaign,Crassusis

said to have excessivelycelebratedhis victoryovertheinsignificant townof

Zenodotia.This,Plutarchwrites,'was veryill thought of,andit lookedas ifhe

despaireda noblerachievement, thathe made so muchof thislittlesuccess'.

Quitea changefromthe'good fortune' and 'excellentgeneralship'thatCrassus

had showedin his campaignagainstSpartacus(19).Needlesslyattacking a city

becomesevenmorea metaphor of a reversaloffortune whenitis counterbalan-

ced by an effectivesiege on an important cityby one's greatestopponent.The

easy, irrelevantand ultimatelyunsuccessful sack of Palmyratookplace just a

year before Octavian'sdifficult

but important fightat Perugiain ВС 41. In his

extensivedescription of thatbattle,Appianis noticeably morepositivetowards

Octavianthanotherancientauthors(20).

But it is, morethananything else, Cleopatra'sinfluenceoverAntonythat

dominatesthis part of the Bella Civilia. Not thatAppian is alone in this.

References totheevilforeignqueen,whocorrupted thegoodRomanAntony, are

(18) Appian, BCW,9. Translation from Carter,CivilWarsГп.11,withH. White, LCL.

(19) Plutarch,Crass.XI. Appian'sdistaste forAntony's motivated

insufficiently

aggression againstPalmyra is alsotypicaloftheauthor'sdisapprovalforwarswithout

somesortof legitimacy. Cf.Appian'sversion of thetreatmentof Crassus'campaign

against theParthians atВС II, 18 andhisdisapproval ofLucullus'behaviour in Spain

СIber. 51).

(20) Appian, ВС V,33-49.Cf.Suetonius, Aug.14-15; Dio 48, 14.ButnoteVelleius

Paterculus II, 74,4. Itmaybe relevant thatbynotintervening inthesiegeofPerugia,

Antony effectivelylefthisbrother LuciusatOctavian's

mercy.NotealsothatAppian con-

spicuously underplays theactivities

ofthethirdtriumvirinthesameperiod: hedoesnot

e.g.mention Lepidus'triumph ofthelastdayof43 ВС : VelleiusPaterculusII, 67,3-4,

whorefers to mocking chantsby Lepidus'soldiers. Cf. R. D. Weigel,Lepidus.The

Tarnished Triumvir, London- NewYork,1992,p. 75.Alsop. 80-81onLepidus'activi-

tiesin41 ВС.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MARK ANDTHERAIDONPALMYRA

ANTONY 77

galorein Romanliterature (21).Plutarchis primeexampleofthis(22).Of course,

he hadhisownreasonsto depictCleopatra(andAntony)quitenegatively. In the

LifeofAntony, whichis oftenparticularly theorigins

moralistic, of thebattleof

Actiumare describedthroughplacingemphasison the dichotomybetween

OctaviaandCleopatra: thegood Romanmatronversusthewickedwitchofthe

East (23).Perhapsthiswas underinfluence oftheLifeofDemetrios: 'The neces-

sityof makingAntonius'eroticismcorrespond to thatof Demetriosmayhave

encouragedPlutarchto acceptand embellishtheAugustanpropagandawhich

madeAntoniusthetipsyparamour oftheEgyptianqueen' (24).On thewholethe

LifeofAntony(like thatof Demetrios)appearsto be a negativeexemplum , as

Plutarch himself(Comp.Demetr. Ant.3,1) implies: 'Bothwereinsolentin pros-

perity,and abandonedthemselves to luxuryand enjoyment'. A wickedwitchof

theEast wouldfitthestructure well (25).Othersfollowedsuit(26).As theimpor-

tanceof thequeen was well advertised, thisis notin theleast surprising

(27).

Appian's Cleopatra therefore need not strike us as exceptional,and neither

shouldhis statement thatAntony'sinfatuation withthequeenheraldsthebegin-

ningof theend. This changein Antony'sbehaviouris also emphasisedby his

impioustreatment ofthesupplicants in thepassagequotedabove: anything that

Cleopatra ordainedwas done, notwithstanding Roman mores. Onlysupplication

to,andacceptanceby,thequeenherselfdecidedthecourseof actiontaken.

(21) Horace,OdesI, 37 ; Epodes9 ; Propertius III, 11; VelleiusPaterculus II, 85,

3-6; Josephus,Ant.lud.XV,97-8; FlorusII, 21,2-3; С. B. R. Pelling,Anything Truth

can do we can do better : theCleopatra Legendin S. WalkerandP. Higgs(eds.),

Cleopatra ofEgypt. FromHistory toMyth , London, 2001,p. 290-301.

(22) Plutarch, Ant.XXVII,1-2; LIII,6-10; Comp.Dem.Ant.III, 1-3.

(23) С. В. R. Pelling,Plutarch's Adaptation ofhisSource-Material inB. Scardigli

(ed.),EssaysonPlutarch's Lives,Oxford, 1995,p. 125-154. According toPelling(p. 148

n.61) thisdichotomy 'seemstobe Plutarch's ownelaboration'.

's Life'Markos Antonios ' :A andCultural in

(24) F.E. Brenk, Plutarch Literary Study

ANRW II.33.6,1992,p.4347-4469. NotealsoAppian, ВС V,76 : 'beingbynature exces-

sivelyfondofwomen'.

(25) С. B. R. Pelling,Plutarch's Method ofWork in theRomanLivesin Scardigli

Essays[n.23],p. 298: 'Private excessesandyetbrilliant : thecontrast

ability is pro-

grammatic, andexcellently prepares theemergence ofCleopatra, Antonius' tekevíalov

xaxóv(25.1)'.Cf.P.Wallmann, TriumviriReiPublicaeConstituendae. Untersuchungen

zurpolitischen Propaganda imzweiten Triumvirat (43-30B.C.),Frankfurt et.al., 1989.

Ongeneral Romanattitudes towards powerful women, plustopoi: N. Purcell,Liviaand

theWomanhood ofRomeinProc.Camb.Philol.Soc. 212,n.s.32,1986,p. 78-105.

(26) E.g.Dio XLIX,34, 1 ; 41, 1 ; L, 5, 1 ; 24,3 ; 24,7 ; 25, 1-4; 27, 1-5.OnDio's

version ofOctavian's pre-

Actium speech, andtheemphasis onthedanger from theEast:

M. Reinhold, FromRepublic toPrincipáte. AnHistorical Commentary onCassiusDio's

Roman History. Book49-52(36-29B.C.),Atlanta, 1988,p. 84.

(27) Wallmann, Triumviri [n.25], p. 252. Famously, Cleopatra is described as the

'QueenofKings'(Cleopatra Reginae Regum) ona coin-type ofMarkAntony ; Crawford,

RRC,I, no.543.1.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

78 & T. KAIZER

O. HEKSTER

Indeed,theveryfirstlines of book fiveare illustrative fortheweightthat

on

Appianplaces Antony'scorruption by his love forCleopatra:

«AfterthedeathofCassiusandBrutus Octavian returned

toItaly,butAntony

pro-

ceededtoAsia,wherehe metCleopatra, queenofEgypt, andsuccumbed toher

charms atfirst Thispassionbrought

sight. ruinuponthemanduponallEgypt(èg

ökrjv

AïyviïTOv) besides(ВС 5,1,1)».

FortheAlexandrian Appian,thefateofEgyptwas oftheutmostimportance.

Andit turnedon thechangein Antony'sbehaviourthatfollowedhis affair with

Cleopatra(28).The raidon Palmyrais putforward whenAppianillustratesthat

specificchange.Moreover,theseemingly irrelevantattacknotonlyhas prece-

dentsin earlierhistoriography,butit mayalso findan echo in therelevantsack

ofPerugiabyhis opponent - Rome'sfirstemperor.

Contemporary contextofthepassage. - WhywasAppianinterested inPalmyra

in thefirstplace ? Whydid he pay attention to theattackbyAntony'sbowmen

whenotherclassicalauthorsdid not? As notedabove,Appianseemssomewhat

topographically challengedin his description of thedistancebetweenPalmyra

andtheEuphrates(29).Thiscouldprovea tellingslip.Bothriverandcityareal-

readymentioned intheProemoftheHistoriaRomana(30).Moreimportantly even,

at Proem1,4AppianstatesthattheEuphrates formsan Easternboundary to the

Empire.Naturally, scholarshaverecognised thisas a terminusantequemforhis

work(31).But thisstatement has widerimplications thanpurelychronological

ones.The explicitemphasison theEuphrates as a bordercouldhaveideological

connotations (32).Hadrian,on his accession,abandonedTrajan'srecently acqui-

redterritoriesbeyondtheEuphrates (33).Thiscontroversialretreat

maywellhave

(28) Ofcourse, Appian's Antony is notunambiguously a 'goodRoman'evenbefore

Cleopatra(e.g.ВС III,98),andnotentirely evilafterwards

either(e.g.ВС V,66 ; V,136).

(29) See supra, n. 12.

(30) Appian, Proem2.

(31) Appian, after all,wroteabouttheEuphrates as a borderinapparent ignorance of

LuciusVerus'Parthian campaigns of 165(on whichsee A. R. Birley,Hadrianto the

AntoninesinСАН112,2000,p. 160-165). See especially

Gabba,Appiano [п. 1],p. ix,-xi,

Vanderleest inAHB3, 1989[п. 12],p. 132,andK. Brodersen, AppianundseinWerk in

ANRW11.34. 1, 1993,p. 353,whoarguefora datearound AD 160.LukePitcher, howe-

ver,kindlypoints outtous thatthere seemstobe noa priorireasontoexcludea dateas

earlyas thelate140s.Essentially thesamepointis madebyG. S. Bucher,TheOrigins

' ,

Program, andComposition ofAppian'sRomanHistory in ТАРА130,2000,p. 411-58;

415-429.

(32) Thisis,indeed, reaffirmedwhenAppiandescribes thedivisionoftheempire by

thetriumvirs(ВС V,65).

(33) On Trajan'sconquests, see Millar, RomanNear East [n.5], p. 90-111;

J. Bennett,TrajanOptimus Princeps, London- NewYork,20012,p. 183-204.On

Hadrian'sprovincialpolicy, seenowC. Ando,Imperial Ideology andProvincial Loyalty

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MARK ANDTHERAIDONPALMYRA

ANTONY 79

madean impacton theyoungAlexandrian, whohadjustarrivedin Rome(34).Is

thisthereasonwhytheEuphrates so

figures prominently in thedescriptionofan

otherwise unknown event? Theriver, inAppian'sperception, was thelimitofthe

civilisedworld.It is unlikelythattheinhabitants of Palmyrawouldflee over

200 kilometres, withall theirpossessions(orin anycase theiressentials), tohide

behinda river,but thepointwas thattheyretreated beyondtheboundaryof

Romanpower.ForAppian,to crosstheEuphrates was to leavetheempire.

Outsidethatempire,so Appianwrites,thePalmyrenes were'preparing them-

selveswithbows in case anyonewouldattackthem'.The historian emphasises

that4heyare by natureexcellent'withthatweapon(Jtgòçâ neqvxaoiv ê^ai-

gérœç). But Antony'smen nevercame. Accordingto the story,they'turned

around'fromPalmyra,'nothavingmetanyone,nothavingtakenanything'. So

this

why emphasis on bowmen then ? It may be worthpointing out thatonlyindi-

vidualPalmyrenes had servedas archersin the imperialforcesfromat least

Trajan'sreign onwards, andthattherewereno regularPalmyrene auxiliaryunits

in theRomanarmyuntillongafterAppianwrotehis work,probablynotbefore

theearlythirdcentury AD (35).It was,ofcourse,theParthians whowerereputed

bowmenin Romantimes(36).TakingintoaccountthatAppiannotonlydescribes

Palmyraas beingsituatedoutsidetheEmpireproper(despitePompey'screation

oftheprovindaSyriain 64 ВС), butalso linkstheattackbyAntony'stroopsto

an indignant reactionfromthepartof theParthians, it is notin theleastsurpri-

sing thathe the with

portrays Palmyrenes primarily Parthian skills.

this

Notwithstanding original 'near-Parthian' reputation Palmyra,by the

of

timeof Appian the cityhad become verymuchpartof the Roman world.

Auxiliary unitswerecertainly basedattheoasis inthedirectaftermath ofLucius

Verus'Parthianwar, and possibly before (37).The city,long adheringto the

organisation of thestandard 'Greek city',had evenbeen visitedby theRoman

in the RomanEmpire , Berkeley- Los Angeles- London,2000, p. 330-335;

M. T. Boatwright, HadrianandtheCitiesoftheRomanEmpire N.J.,2000.

, Princeton,

(34) Forthedating ofAppian'sarrivalin Rome,see Gowing, Narratives

Triumvirat

[n.12],p. 16.

(35) A number record

ofdiplomata thegrantofcitizenshiptosuchsoldiers intheearly

yearsofHadrian : CIL XVI,68 ; M. M. Roxan,RomanMilitary Diplomas1954-1977 ,

London, 1978,17,27-28: Palmyrenis See alsoIsaac,Limits

Sagittariis. ofEmpire [n.2],

p. 144.Thereis noevidenceforPalmyrene archersatDuraintheParthian period, as has

beensuggested. See nowDirven, Palmyrenes [n.2],p. 34,withreferences.Bowmen are

atDurainAD 168-171: Dirven,

attested Palmyrenes [n.2],p. 233-235.

(36) See e.g.O. Kurz,TheCambridge HistoryofIran3 (1),Cambridge, 1983,p. 561,

on thedreaded mobilityoftheParthian mounted archers,andespecially theso-called

'Parthian

shot'.

(37) For further see J.-P.Rey-Coquais,

references, Syrieromaine, de Pompéeà

DioclétieninJRS68, 1978,p. 68,andMillar,Roman NearEast[п.5],p. 108.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

80 O. HEKSTER

& T. KAIZER

emperorhimself(38).ForPalmyra,thisadventusmusthavebeena majorevent,

whichfoundreflection in theadditionof 'Hadriane'to itsname(39).Whetherthe

imperial visit was also advertisedin Rome is of courseanothermatter.But

Hadrian'sreignis preciselytheperiodin whichtheprovincesand theirinhabi-

tantsweremorethanbeforeacknowledged as an inherentpartoftheEmpire(40).

It maynotbe entirely accidentalthatthelistofthoseinscriptions fromPalmyra,

whichreferto thecity'slong-distance trade,showsa noticeableconcentrationin

thefirsthalfofthesecondcentury (41).

Recently,Appianhas been describedas an Antoninehistorian(42).He, as

everyauthor,saw theworldin thecontextof his own time.This wentbeyond

simplepoliticaladherenceto therulingdynasty.

Perceptions areinfluencedbya

varietyof incentives.

Indeed, the'critic's

taskmust be first

and foremostto seek

reasons'forthechoiceof composition anddetailsinAppian'swriting (43).With

theobservations madein thepresentcontribution, we hopeto haveshownhow

contemporary opinionsand eventshelped to shape Appian's descriptionof

Antony's raidon Palmyrain 41 ВС. Theythuscontinueto influence ourpercep-

tionsof an important

episodeofRomanhistory.

WadhamCollege- MertonCollege, Oxford

, OlivierHekster

and CorpusChristiCollege, Oxford. andTed Kaizer.

(38) See PAT0305(AD 131),whichrecords theerectionofa statue fora Palmyrene

whohadprovided oil forcitizens

andaccommodation forthearmy'during thevisitof

(ourlord)thedivine Hadrian'. Thedouble-structured ofa bouléanda dèmos

organisation

is firstattested

atPalmyra inAD 74,seeJ.Cantineau, TadmoreainSyria14,1933,p.

174,no2b,although theassembly onitsownappears already

preciselyfiftyyearsearlier,

seePAT1352.Thefamous taxlawfrom AD 137givesa wholeseriesofoffices of

typical

a 'Greekcity',seePAT0259.

(39) Thetaxlaw{PAT0259)givesthenewnameinPalmyrenean only(hdryn' tdmr),

but an inscription fromsix yearsearlierrefersto its honoureeas [fAôjçiavòv

IlaktiVQrjvóv,see PAT1374(AD 131). See nowalso Boatwright, Hadrian[n.33],

p. 104-5.

(40) Theprocesshasbeenhighlighted recentlybyAndo,Imperial Ideology [n.33],

p. 330-5,andBoatwright, Hadrian[n.33],esp.p. 204-9.

(41) See M. Gawlikowski, Palmyraas a Trading CentreinIraq 56, 1994,p. 27-33,

withthelistonp. 32-33.Cf.F. Millar,CaravanCities: theRoman NearEastandLong-

distance TradebyLandinM. Austin, J.HarriesandC. Smith (eds.),ModusOperandi :

Essaysin Honourof Geoffrey Rickman, London,1998 (Bulletin of theInstituteof

ClassicalStudies, Suppl.71),p. 119-137.Mostrecently Young,Rome'sEasternTrade

[n.3],p. 136-186.

(42) Gowing, Triumviral Narratives

[n.12],p. 273-287.

(43) Gowing, Triumviral Narratives

[n.12],p. 277.

This content downloaded from 62.122.77.28 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 15:39:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Art and Archaeology of Ancient Rome Vol 2: Art and Archaeology of Ancient RomeFrom EverandArt and Archaeology of Ancient Rome Vol 2: Art and Archaeology of Ancient RomeNo ratings yet

- Cleopatra (1963)Document5 pagesCleopatra (1963)stelaptNo ratings yet

- John Wilson - Caesarea Philippi - Banias, The Lost City of PanDocument266 pagesJohn Wilson - Caesarea Philippi - Banias, The Lost City of PanMateus CruzNo ratings yet

- Lord of The Four Quarters The Mythology of Kingship (PDFDrive)Document319 pagesLord of The Four Quarters The Mythology of Kingship (PDFDrive)18daniel100% (2)

- Alexandria in RomeDocument15 pagesAlexandria in Romeshakhti4100% (1)

- The Coming of the Greeks: Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and the Near EastFrom EverandThe Coming of the Greeks: Indo-European Conquests in the Aegean and the Near EastRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (16)

- A Vindication of The Ancient History of IrelandDocument31 pagesA Vindication of The Ancient History of IrelandDr. QuantumNo ratings yet

- Roller, Duane W. - The Building Program of Herod The GreatDocument177 pagesRoller, Duane W. - The Building Program of Herod The GreatEditorial100% (1)

- Piracy in The Graeco-Roman WorldDocument18 pagesPiracy in The Graeco-Roman WorldsilenttalkerNo ratings yet

- The Roman EconomyDocument3 pagesThe Roman EconomyFacundoNo ratings yet

- Black HunmterDocument17 pagesBlack HunmterCarlos MNo ratings yet

- Ancient Robbers. Reflections Behind The FactsDocument21 pagesAncient Robbers. Reflections Behind The FactspacoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 189.120.72.61 On Wed, 08 Sep 2021 19:29:09 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 189.120.72.61 On Wed, 08 Sep 2021 19:29:09 UTCbrngrs5No ratings yet

- Piracy in The Greco-Roman World PDFDocument18 pagesPiracy in The Greco-Roman World PDFshshsh12346565No ratings yet

- ExportDocument6 pagesExportalisadavidsonmailNo ratings yet

- Strix en El CristianismoDocument16 pagesStrix en El Cristianismolorena1019No ratings yet

- On The Imitation of AntiquityDocument25 pagesOn The Imitation of AntiquityAgustín AvilaNo ratings yet

- Larchersnotesonh 02 LarcDocument480 pagesLarchersnotesonh 02 LarcILLYRIAN DARDANIANNo ratings yet

- Latin Siege Warfare in The Twelfth Century - by R. Rogers (1994)Document5 pagesLatin Siege Warfare in The Twelfth Century - by R. Rogers (1994)giannesNo ratings yet

- Raqs SeepageDocument177 pagesRaqs SeepageAkansha RastogiNo ratings yet

- On The Trail of Kume The Transcendent (M Bulletin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Vol. 79) (1981)Document25 pagesOn The Trail of Kume The Transcendent (M Bulletin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Vol. 79) (1981)Carlos Mercado LunaNo ratings yet

- Toby WilkinsonDocument11 pagesToby WilkinsonAngelo_Colonna100% (1)

- Aristophanes EcclesiazusaeDocument288 pagesAristophanes EcclesiazusaeEmily FaireyNo ratings yet

- Wonder of The World! Fairburn's Account of The MermaidDocument30 pagesWonder of The World! Fairburn's Account of The Mermaidİsrael CuéllarNo ratings yet

- DCS 3dc428fb 20b0 4c0e A5b5 Ab4aa50f9e46 Clash With NotesDocument10 pagesDCS 3dc428fb 20b0 4c0e A5b5 Ab4aa50f9e46 Clash With Notessvh5m7gn8fNo ratings yet

- ZAVAGNO EdgeTwoEmpires 2011Document36 pagesZAVAGNO EdgeTwoEmpires 2011batuhan batakNo ratings yet

- Goldberg, The Fall and Rise of Roman Tragedy PDFDocument23 pagesGoldberg, The Fall and Rise of Roman Tragedy PDFn pNo ratings yet

- Char On MannDocument4 pagesChar On ManndanalindaNo ratings yet

- Piracy and The Venetian State The Dilemma of Maritime Defense in The Fourteenth CenturDocument26 pagesPiracy and The Venetian State The Dilemma of Maritime Defense in The Fourteenth CenturasdgsdfgNo ratings yet

- Tap-Tap, Fula-Fula, Kia-Kia: The Haitian Bus in Atlantic PerspectiveDocument13 pagesTap-Tap, Fula-Fula, Kia-Kia: The Haitian Bus in Atlantic Perspectivejysouza11No ratings yet

- Mark Twain - Was The World Made For Man PDFDocument4 pagesMark Twain - Was The World Made For Man PDFCarlos A Sanches IINo ratings yet

- Larcher's Notes On Herodotus (1844)Document469 pagesLarcher's Notes On Herodotus (1844)Babilonia CruzNo ratings yet

- The Tale of Gyges and The King of LydiaDocument53 pagesThe Tale of Gyges and The King of LydiadeepanNo ratings yet

- University of Texas PressDocument26 pagesUniversity of Texas Presspalak motsaraNo ratings yet

- Penn State University Press: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument26 pagesPenn State University Press: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPjoaocadenhoNo ratings yet

- M. Gawlikowski - Palmyra As A Trading CentreDocument8 pagesM. Gawlikowski - Palmyra As A Trading CentreddNo ratings yet

- Quint Mickle, Barlow, Melville Camoes (Seminar 2)Document40 pagesQuint Mickle, Barlow, Melville Camoes (Seminar 2)Ines MarquesNo ratings yet

- Society For The Promotion of Roman StudiesDocument2 pagesSociety For The Promotion of Roman StudiesΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Yzantium Ast and EST: Project 67: China and The Mediterranean WorldDocument290 pagesYzantium Ast and EST: Project 67: China and The Mediterranean WorldAndoni CushaNo ratings yet

- Comaroffs Ethnography and The Historical Imagination (1992)Document33 pagesComaroffs Ethnography and The Historical Imagination (1992)Francois G. RichardNo ratings yet

- Cleto IntroductionDocument42 pagesCleto IntroductionDaniela JohannesNo ratings yet

- Ma, J. (2008) - The Return of The Black Hunter. The Cambridge Classical Journal, 54 (54), 188-208.Document21 pagesMa, J. (2008) - The Return of The Black Hunter. The Cambridge Classical Journal, 54 (54), 188-208.JordynNo ratings yet

- S. A. Sterz, The Emperor Hadrian and Intelectuals, ANRW 2.34.1 (1993)Document17 pagesS. A. Sterz, The Emperor Hadrian and Intelectuals, ANRW 2.34.1 (1993)Julija ŽeleznikNo ratings yet

- Richard Stoneman - Greek Mythology PDFDocument196 pagesRichard Stoneman - Greek Mythology PDFEnikő Molnár100% (4)

- The History of the Peloponnesian War (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)From EverandThe History of the Peloponnesian War (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)No ratings yet

- Daed A 00380Document11 pagesDaed A 00380David PodłęckiNo ratings yet

- Roman Sarcophagi-AnnotatedDocument84 pagesRoman Sarcophagi-AnnotatedLucía BueyNo ratings yet

- 10 2307@267080Document3 pages10 2307@267080Felipe MontanaresNo ratings yet

- Cervantes y Lo Real Maravilloso PDFDocument38 pagesCervantes y Lo Real Maravilloso PDFA MaderNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 169.0.116.39 On Sun, 26 Mar 2023 11:00:08 UTCDocument17 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 169.0.116.39 On Sun, 26 Mar 2023 11:00:08 UTCOuhleNo ratings yet

- 155855-Texto Do Artigo-362499-1-10-20190809Document30 pages155855-Texto Do Artigo-362499-1-10-20190809LuizaNo ratings yet

- CH 4Document13 pagesCH 4Anth5334No ratings yet

- HarperDocument11 pagesHarperYsaline wiwiNo ratings yet

- Propertius and Antony J.griffin 1977Document11 pagesPropertius and Antony J.griffin 1977ekinoyken7834No ratings yet

- Афинское городское кладбище PDFDocument42 pagesАфинское городское кладбище PDFГаланин РустамNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument5 pagesThe University of Chicago PressValquíria VelascoNo ratings yet

- Society For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressDocument33 pagesSociety For Comparative Studies in Society and History: Cambridge University PressGastón Alejandro OliveraNo ratings yet

- Beforecolumbus 4 EngDocument16 pagesBeforecolumbus 4 EngReeana SaughNo ratings yet

- Representations of TropicsDocument16 pagesRepresentations of TropicsARK234No ratings yet

- WABForumSupplements CaesarDocument20 pagesWABForumSupplements Caesarskallaborn100% (4)

- ShawDocument12 pagesShawMihaela DrimbareanuNo ratings yet

- Ptolemaic Kingdom: PtolemaïkDocument26 pagesPtolemaic Kingdom: Ptolemaïkapollodoro87No ratings yet

- Egyptology Articles Herbs ArticlesDocument5 pagesEgyptology Articles Herbs ArticleskarthikNo ratings yet

- Pseudo Aurelius VictorDocument1 pagePseudo Aurelius VictorEllen ZakharianNo ratings yet

- Ptolemaic EgyptDocument12 pagesPtolemaic Egyptapi-334420312No ratings yet

- Antony and CleopatraDocument17 pagesAntony and CleopatraJonathan MalabananNo ratings yet

- Characters-Antony and CleopatraDocument3 pagesCharacters-Antony and Cleopatraapi-3750482No ratings yet

- CKHG G3 U2 AncientRome SR PDFDocument114 pagesCKHG G3 U2 AncientRome SR PDFJamie Chan Jiemin100% (2)

- 1853 - The Boot and Shoe Makers AssistantDocument238 pages1853 - The Boot and Shoe Makers AssistantEdNo ratings yet

- MagdaleneDocument27 pagesMagdaleneTom Slattery100% (2)

- Pub - Ancient Egypt Ancient Civilizations PDFDocument89 pagesPub - Ancient Egypt Ancient Civilizations PDFjanosuke100% (1)

- What Is A Pharaoh?: Horus, Son of Re, The Sun God. When A Pharaoh Died He WasDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Pharaoh?: Horus, Son of Re, The Sun God. When A Pharaoh Died He WaslemmielemsNo ratings yet

- Summary Act IIIDocument19 pagesSummary Act IIImae sherisse caayNo ratings yet

- Politics of Egyptology and The History of KemetDocument15 pagesPolitics of Egyptology and The History of Kemetdropsey100% (3)

- Greco-Roman Period in Egypt: Marina FakherDocument75 pagesGreco-Roman Period in Egypt: Marina FakherMarina F. NaguibNo ratings yet

- Antony and CleopatraDocument3 pagesAntony and CleopatraDivya DhawanNo ratings yet

- Cleopatra at Four PagesDocument4 pagesCleopatra at Four Pagesanon-7879100% (1)

- Antonio Si CleopatraDocument6 pagesAntonio Si CleopatraPuntel PetronelaNo ratings yet

- LKS Unit 10-12Document30 pagesLKS Unit 10-12Triana RahayuNo ratings yet

- Master Cleopatra InputDocument3 pagesMaster Cleopatra Inputapi-194648770No ratings yet

- Folklore and Related SciencesDocument99 pagesFolklore and Related Scienceschak.m.beyenaNo ratings yet

- 9004175016Document249 pages9004175016Ante Vukic100% (3)

- Classic Bulletin 85 DocumentDocument241 pagesClassic Bulletin 85 DocumentumityilmazNo ratings yet

- Materi Kuliah TPA 2 (Mesir)Document104 pagesMateri Kuliah TPA 2 (Mesir)Ghani Sayid HamzahNo ratings yet

- B2 LIFE UNIT 10 Queen of Egypt Video ScriptDocument2 pagesB2 LIFE UNIT 10 Queen of Egypt Video ScriptKazuWeedNo ratings yet