Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Text For The Audio

Text For The Audio

Uploaded by

nocasines4Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Shipbroking and Chartering Practice (2018, Informa Law From Routledge)Document771 pagesShipbroking and Chartering Practice (2018, Informa Law From Routledge)Mohamed Akil100% (8)

- Sample AirAsia TicketDocument2 pagesSample AirAsia TicketJessNo ratings yet

- MOSELEY, M. The Incas and Their Ancestors - The Archaeology of PeruDocument289 pagesMOSELEY, M. The Incas and Their Ancestors - The Archaeology of PeruBernarda Marconetto90% (10)

- Especificaciones Sssangyong Rexton 2.7 Xdi CRDocument2 pagesEspecificaciones Sssangyong Rexton 2.7 Xdi CRAmadeus De La Cruz0% (1)

- Arms Rules 1924 PDFDocument88 pagesArms Rules 1924 PDFshoaib87% (23)

- Mohenjo - Daro and The Indus Valley Civilization1922-1927 Vol IDocument423 pagesMohenjo - Daro and The Indus Valley Civilization1922-1927 Vol Iaravindaero123100% (4)

- About The Silk RoadDocument5 pagesAbout The Silk RoadAmna jabbarNo ratings yet

- SocStud107 AisanHistory Module Week10Document6 pagesSocStud107 AisanHistory Module Week10James Russel MelgarNo ratings yet

- About The Silk Roads - Silk Roads ProgrammeDocument4 pagesAbout The Silk Roads - Silk Roads ProgrammeRebecca Lalrindiki JouteNo ratings yet

- History of Silk TradeDocument7 pagesHistory of Silk TradePARI PATELNo ratings yet

- Trade and Commerce: A Brief History and IntroductionDocument67 pagesTrade and Commerce: A Brief History and IntroductionNaveen Jacob JohnNo ratings yet

- GE4Document3 pagesGE4Reynalyn GalvezNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On The Silk RoadDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On The Silk Roadtrsrpyznd100% (1)

- Trade and Commerce in Ancient China : The Grand Canal and The Silk Road - Ancient China Books for Kids | Children's Ancient HistoryFrom EverandTrade and Commerce in Ancient China : The Grand Canal and The Silk Road - Ancient China Books for Kids | Children's Ancient HistoryNo ratings yet

- Chinas Silk RoadDocument10 pagesChinas Silk RoadmauludiNo ratings yet

- Tushar Presentation On SilkDocument16 pagesTushar Presentation On Silkchauhanbrothers3423No ratings yet

- Trade RoutesDocument1 pageTrade RoutesAlec SiegalNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - Into The Past The Silk Road (Exercises) - Đã G PDocument49 pagesWeek 2 - Into The Past The Silk Road (Exercises) - Đã G PAnh ChauNo ratings yet

- The Silk Roads: A History of the Great Trading Routes Between East and WestFrom EverandThe Silk Roads: A History of the Great Trading Routes Between East and WestRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Silk RoadDocument4 pagesSilk RoadDensis AgbalogNo ratings yet

- Silk Road: Joshua J. MarkDocument11 pagesSilk Road: Joshua J. Marktaha shakirNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument20 pagesSilk RoadT Sampath KumaranNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument1 pageSilk RoadPierre Freneau MX3DNo ratings yet

- Ersdgvbsertg 5Document1 pageErsdgvbsertg 5Pisti TóthNo ratings yet

- Africa InvestigationDocument4 pagesAfrica InvestigationBrian Roberts100% (1)

- Silk Route Business Evolution and It's ImpactDocument24 pagesSilk Route Business Evolution and It's ImpactPawar Viraj 99-2019No ratings yet

- Silk Road and Its HistoryDocument11 pagesSilk Road and Its HistoryAakanksha KalraNo ratings yet

- Day 4 WordsDocument2 pagesDay 4 WordsburkhanovbakhriddinNo ratings yet

- East Meets West - The Silk RoadDocument3 pagesEast Meets West - The Silk RoadOlivia ModadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Tourism Through AgesDocument16 pagesChapter 2 Tourism Through AgesThe Book WorldNo ratings yet

- Foltz - The Silk Road and Its TravelersDocument22 pagesFoltz - The Silk Road and Its TravelersknatadiriaNo ratings yet

- What Is Silk RoadDocument3 pagesWhat Is Silk Roadtamilarasi.shanmugamNo ratings yet

- Silk Road: Joshua J. MarkDocument27 pagesSilk Road: Joshua J. MarkBenjaminFigueroaNo ratings yet

- 7the Untouchables and The PaxBritannicaDocument62 pages7the Untouchables and The PaxBritannicaAlexNo ratings yet

- El Qpaq Ñan: Highway of The SunDocument371 pagesEl Qpaq Ñan: Highway of The SunElvira FernandezNo ratings yet

- The Untouchables and The Pax Britannica Dr. B.R.ambedkarDocument61 pagesThe Untouchables and The Pax Britannica Dr. B.R.ambedkarVeeramani ManiNo ratings yet

- Ideas That Shaped Our Modern World: Connecting With The GodsDocument9 pagesIdeas That Shaped Our Modern World: Connecting With The Godstalented guyNo ratings yet

- 3 Silk Route200303111103034747Document8 pages3 Silk Route200303111103034747d3257482No ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument5 pagesSilk Roadkrsta “Savatije” maglicNo ratings yet

- Making of A Global WorldDocument3 pagesMaking of A Global WorldsimoneNo ratings yet

- SilkroadpaperDocument1 pageSilkroadpaperapi-275479424No ratings yet

- Ebook Landmarks 4th Fiero CH 9Document20 pagesEbook Landmarks 4th Fiero CH 9Quyền AnhNo ratings yet

- PDF Document 6Document4 pagesPDF Document 6JudaNo ratings yet

- Silk Road - World History EncyclopediaDocument9 pagesSilk Road - World History Encyclopedianaomigarrido28No ratings yet

- Note - Factors Motivating Europeans To Explore and Settle in The Caribbean Up To The End of The 17th CenturyDocument7 pagesNote - Factors Motivating Europeans To Explore and Settle in The Caribbean Up To The End of The 17th CenturyraelamNo ratings yet

- The Silk Road: Explore the World's Most Famous Trade Route with 20 ProjectsFrom EverandThe Silk Road: Explore the World's Most Famous Trade Route with 20 ProjectsNo ratings yet

- W Cline ReseñaDocument3 pagesW Cline ReseñaSol HeffesseNo ratings yet

- The Making of A Global World NotesDocument3 pagesThe Making of A Global World NotesSaanvi JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Waugh PDFDocument14 pagesWaugh PDFAdrian GeoNo ratings yet

- Moseley2001 Incas AncestorsDocument289 pagesMoseley2001 Incas AncestorsAlexander Chahuasoncco Papel100% (1)

- East Meets WestDocument2 pagesEast Meets WestMissKuoNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument5 pagesSilk Roadapi-309265066No ratings yet

- Silk Road Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesSilk Road Thesis Statementtunwpmzcf100% (2)

- Wembley Calendar 2020Document28 pagesWembley Calendar 2020Redewaan WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - Silk RoadDocument8 pagesGroup 1 - Silk RoadCherubNo ratings yet

- Group 1Document46 pagesGroup 1Lombroso's followerNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument64 pagesSilk RoadudayNo ratings yet

- Arikamedu - An Ancient Port DR Uday DokrasDocument61 pagesArikamedu - An Ancient Port DR Uday DokrasudayNo ratings yet

- Filmes PopcornDocument1 pageFilmes Popcornnocasines4No ratings yet

- Cópia de Book Club FlyerDocument1 pageCópia de Book Club Flyernocasines4No ratings yet

- DetroitDocument13 pagesDetroitnocasines4No ratings yet

- Greenland - Model Presentationv2Document6 pagesGreenland - Model Presentationv2nocasines4No ratings yet

- The Inca - PPTv2Document15 pagesThe Inca - PPTv2nocasines4No ratings yet

- City Girl Vs Country Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan FordDocument312 pagesCity Girl Vs Country Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan Fordnocasines4No ratings yet

- Broken Girl Vs Fix-It Boy Forever Love Bo - Jordan FordDocument358 pagesBroken Girl Vs Fix-It Boy Forever Love Bo - Jordan Fordnocasines4No ratings yet

- Lost Girl Vs Wounded Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan FordDocument280 pagesLost Girl Vs Wounded Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan Fordnocasines4No ratings yet

- Circular 2021-41 (2021-12-01)Document6 pagesCircular 2021-41 (2021-12-01)AndreasNo ratings yet

- Fermentare PDFDocument90 pagesFermentare PDFIstudor AdrianaNo ratings yet

- CLDocument37 pagesCLSpirou Rox50% (2)

- Procedures and Arrangements ManualDocument5 pagesProcedures and Arrangements ManualNishadYadavNo ratings yet

- Military Review, February 1956Document116 pagesMilitary Review, February 1956Jerry BuzzNo ratings yet

- Prueba - Frenos de ServicioDocument2 pagesPrueba - Frenos de ServicioUlises BarreraNo ratings yet

- Autocross Technical Inspection ProceduresDocument5 pagesAutocross Technical Inspection ProceduresRajat NanchahalNo ratings yet

- Project Management (Heathrow Terminal)Document6 pagesProject Management (Heathrow Terminal)Lekh RajNo ratings yet

- Angol Társalgási GyakorlatokDocument24 pagesAngol Társalgási GyakorlatokBeatrix KovácsNo ratings yet

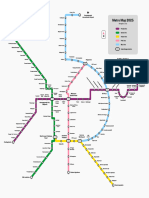

- Metro Map 2025 - Bengaluru CityDocument1 pageMetro Map 2025 - Bengaluru CityDeepak BhatNo ratings yet

- Emirates Airlines StrategyDocument9 pagesEmirates Airlines StrategyAloha Pn100% (1)

- 21 870 Campbelltown To Liverpool Via Glenfield 20230925 20231007 1Document6 pages21 870 Campbelltown To Liverpool Via Glenfield 20230925 20231007 1Neng RegsNo ratings yet

- Transmicion 4E27EDocument367 pagesTransmicion 4E27ELuis Castro100% (3)

- IXB BLR: TICKET - ConfirmedDocument2 pagesIXB BLR: TICKET - ConfirmedTenzing PhintsoNo ratings yet

- Book 3Document3 pagesBook 3sumit4407No ratings yet

- Transit Oriented Development in India: Mukund Kumar Sinha, Ministry of Urban Development Government of IndiaDocument37 pagesTransit Oriented Development in India: Mukund Kumar Sinha, Ministry of Urban Development Government of IndiaBadr KaziNo ratings yet

- 66 Polymer Modified Asphalt BinderDocument7 pages66 Polymer Modified Asphalt BinderLeni Widiarti LenwidNo ratings yet

- Efaz Et Al 2022 Combined Load Test and Nde Novel Method To Diagnose and Load Rate Prestressed Concrete Girder BridgesDocument16 pagesEfaz Et Al 2022 Combined Load Test and Nde Novel Method To Diagnose and Load Rate Prestressed Concrete Girder BridgesTONY VILCHEZ YARIHUAMANNo ratings yet

- Electronic Ticket Record: Passenger Name(s)Document1 pageElectronic Ticket Record: Passenger Name(s)Chenaulde BoukouNo ratings yet

- Wired Up RoadsDocument14 pagesWired Up RoadsvamshivarunNo ratings yet

- Normal Procedures 737-NgDocument101 pagesNormal Procedures 737-NgAllan Mucken100% (1)

- Zonal Regulations: Chapter-14Document44 pagesZonal Regulations: Chapter-14RB joshiNo ratings yet

- French Pioneers in The West Indies, 1624-1664. Crouse, Nellis Maynard, 1884Document307 pagesFrench Pioneers in The West Indies, 1624-1664. Crouse, Nellis Maynard, 1884Dionisio Mesye100% (1)

- Pont Dalle en Béton Armé (Solid Slab Bridge) I. Hypothèse StructureDocument5 pagesPont Dalle en Béton Armé (Solid Slab Bridge) I. Hypothèse Structureken koemhongNo ratings yet

- Effect of Weight On Stall SpeedDocument2 pagesEffect of Weight On Stall Speedpp2076No ratings yet

- Rano RecruitmentDocument7 pagesRano RecruitmentAdetunji TaiwoNo ratings yet

Text For The Audio

Text For The Audio

Uploaded by

nocasines4Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Text For The Audio

Text For The Audio

Uploaded by

nocasines4Copyright:

Available Formats

Text for the Audio

The Silk Road was not, as the name suggests, a single road at all. It consisted of an extensive network of trade routes

that criss-crossed China, parts of the Middle East and Europe, for almost 3,000 years from the first millennium BC

until about 1500 AD. The starting point was in China, and the main land routes extended over a huge area of what is

now modern-day China, Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. And

when goods arrived at the coast they were transported by sea to the major trading ports of Europe, northern Africa

and Asia.

Since the transport capacity was limited, luxury goods were the only commodities that could be traded. As the name

suggests, silk was the main commodity that was traded on the Silk Road. Silk was highly prized and in great demand

in the west, and the silk-making process was a secret that was closely guarded for centuries under punishment of

death. Silk was ideal for overland travel as it was light, easy to carry and took up little space. It was manufactured in

China, and was intricately decorated and embroidered, and when it arrived in Europe it was made into luxury goods

such as book coverings, wall hangings and clothes.

Silk was by no means the only commodity exchanged by traders, however. Perfumes, precious stones and metals,

and foodstuffs were exchanged in both directions. There was also a lucrative trade in spices from east to west; in fact

one European town is on record as selling as many as 288 different kinds. In the west, people had to keep meat for a

long time until it turned rancid, and spices were very useful for disguising the flavour. Some of the most valuable

ones – ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon and saffron – were actually worth more than their weight in gold. Pepper was also

extremely valuable, and caravans that carried it were heavily armed.

In addition to silk and spices, Europeans were eager to import teas and porcelain from China as well as Persian

carpets. The Chinese, for their part, particularly appreciated coloured glass from the Mediterranean, and also

imported such commodities as fine tableware, wool and linen, horses and saddles. Many of these goods were

bartered for others along the way, and objects often changed hands several times. And it was not only goods that

were exchanged on the routes, but also many important scientific and technological innovations; the magnetic

compass, the printing press, paper-making and gunpowder all originated in the East, not to mention important

intellectual developments such as algebra and astronomy. And in return, the West taught the East about

construction techniques, shipbuilding and wine-making.

Life for traders along the Silk Road was often hard. As well as having to trek over some of the world’s most

inhospitable terrain, they also faced the ever-present threat of bandits, not to mention wars, plagues and natural

disasters. Between towns and oases, they would often sleep in yurts or under the stars, or else would stop for rest

and refreshment at one of the several bustling oasis towns that sprang up along the routes. Here they would stay at

caravanserais, places which offered free board and lodging, as well as stables for their camels or donkeys. The

caravanserai became a rich melting pot of ideas, used as they were not only by traders and merchants, but also by

pilgrims, missionaries, soldiers, nomads and urban dwellers from all over the region.

By the end of the 14th century, as other trading routes were established, the importance of the Silk Road had greatly

diminished. But it is no exaggeration to say that it had played a major part in establishing the foundations of the

modern world. It had allowed the exchange not only of commodities, but also of music, arts, science, customs, ideas,

religions and philosophies. In fact, there was so much cultural interchange over so many centuries that it is now

often difficult to identify the origins of numerous traditions that our respective cultures take for granted. So we can

say that, in its heyday the Silk Road was an early example of the political, economic and cultural integration that we

know today as globalisation. And today, the Silk Road is again being used – not only by traders, but also for that most

contemporary of international commodities – tourism.

You might also like

- Shipbroking and Chartering Practice (2018, Informa Law From Routledge)Document771 pagesShipbroking and Chartering Practice (2018, Informa Law From Routledge)Mohamed Akil100% (8)

- Sample AirAsia TicketDocument2 pagesSample AirAsia TicketJessNo ratings yet

- MOSELEY, M. The Incas and Their Ancestors - The Archaeology of PeruDocument289 pagesMOSELEY, M. The Incas and Their Ancestors - The Archaeology of PeruBernarda Marconetto90% (10)

- Especificaciones Sssangyong Rexton 2.7 Xdi CRDocument2 pagesEspecificaciones Sssangyong Rexton 2.7 Xdi CRAmadeus De La Cruz0% (1)

- Arms Rules 1924 PDFDocument88 pagesArms Rules 1924 PDFshoaib87% (23)

- Mohenjo - Daro and The Indus Valley Civilization1922-1927 Vol IDocument423 pagesMohenjo - Daro and The Indus Valley Civilization1922-1927 Vol Iaravindaero123100% (4)

- About The Silk RoadDocument5 pagesAbout The Silk RoadAmna jabbarNo ratings yet

- SocStud107 AisanHistory Module Week10Document6 pagesSocStud107 AisanHistory Module Week10James Russel MelgarNo ratings yet

- About The Silk Roads - Silk Roads ProgrammeDocument4 pagesAbout The Silk Roads - Silk Roads ProgrammeRebecca Lalrindiki JouteNo ratings yet

- History of Silk TradeDocument7 pagesHistory of Silk TradePARI PATELNo ratings yet

- Trade and Commerce: A Brief History and IntroductionDocument67 pagesTrade and Commerce: A Brief History and IntroductionNaveen Jacob JohnNo ratings yet

- GE4Document3 pagesGE4Reynalyn GalvezNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On The Silk RoadDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On The Silk Roadtrsrpyznd100% (1)

- Trade and Commerce in Ancient China : The Grand Canal and The Silk Road - Ancient China Books for Kids | Children's Ancient HistoryFrom EverandTrade and Commerce in Ancient China : The Grand Canal and The Silk Road - Ancient China Books for Kids | Children's Ancient HistoryNo ratings yet

- Chinas Silk RoadDocument10 pagesChinas Silk RoadmauludiNo ratings yet

- Tushar Presentation On SilkDocument16 pagesTushar Presentation On Silkchauhanbrothers3423No ratings yet

- Trade RoutesDocument1 pageTrade RoutesAlec SiegalNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - Into The Past The Silk Road (Exercises) - Đã G PDocument49 pagesWeek 2 - Into The Past The Silk Road (Exercises) - Đã G PAnh ChauNo ratings yet

- The Silk Roads: A History of the Great Trading Routes Between East and WestFrom EverandThe Silk Roads: A History of the Great Trading Routes Between East and WestRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Silk RoadDocument4 pagesSilk RoadDensis AgbalogNo ratings yet

- Silk Road: Joshua J. MarkDocument11 pagesSilk Road: Joshua J. Marktaha shakirNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument20 pagesSilk RoadT Sampath KumaranNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument1 pageSilk RoadPierre Freneau MX3DNo ratings yet

- Ersdgvbsertg 5Document1 pageErsdgvbsertg 5Pisti TóthNo ratings yet

- Africa InvestigationDocument4 pagesAfrica InvestigationBrian Roberts100% (1)

- Silk Route Business Evolution and It's ImpactDocument24 pagesSilk Route Business Evolution and It's ImpactPawar Viraj 99-2019No ratings yet

- Silk Road and Its HistoryDocument11 pagesSilk Road and Its HistoryAakanksha KalraNo ratings yet

- Day 4 WordsDocument2 pagesDay 4 WordsburkhanovbakhriddinNo ratings yet

- East Meets West - The Silk RoadDocument3 pagesEast Meets West - The Silk RoadOlivia ModadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Tourism Through AgesDocument16 pagesChapter 2 Tourism Through AgesThe Book WorldNo ratings yet

- Foltz - The Silk Road and Its TravelersDocument22 pagesFoltz - The Silk Road and Its TravelersknatadiriaNo ratings yet

- What Is Silk RoadDocument3 pagesWhat Is Silk Roadtamilarasi.shanmugamNo ratings yet

- Silk Road: Joshua J. MarkDocument27 pagesSilk Road: Joshua J. MarkBenjaminFigueroaNo ratings yet

- 7the Untouchables and The PaxBritannicaDocument62 pages7the Untouchables and The PaxBritannicaAlexNo ratings yet

- El Qpaq Ñan: Highway of The SunDocument371 pagesEl Qpaq Ñan: Highway of The SunElvira FernandezNo ratings yet

- The Untouchables and The Pax Britannica Dr. B.R.ambedkarDocument61 pagesThe Untouchables and The Pax Britannica Dr. B.R.ambedkarVeeramani ManiNo ratings yet

- Ideas That Shaped Our Modern World: Connecting With The GodsDocument9 pagesIdeas That Shaped Our Modern World: Connecting With The Godstalented guyNo ratings yet

- 3 Silk Route200303111103034747Document8 pages3 Silk Route200303111103034747d3257482No ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument5 pagesSilk Roadkrsta “Savatije” maglicNo ratings yet

- Making of A Global WorldDocument3 pagesMaking of A Global WorldsimoneNo ratings yet

- SilkroadpaperDocument1 pageSilkroadpaperapi-275479424No ratings yet

- Ebook Landmarks 4th Fiero CH 9Document20 pagesEbook Landmarks 4th Fiero CH 9Quyền AnhNo ratings yet

- PDF Document 6Document4 pagesPDF Document 6JudaNo ratings yet

- Silk Road - World History EncyclopediaDocument9 pagesSilk Road - World History Encyclopedianaomigarrido28No ratings yet

- Note - Factors Motivating Europeans To Explore and Settle in The Caribbean Up To The End of The 17th CenturyDocument7 pagesNote - Factors Motivating Europeans To Explore and Settle in The Caribbean Up To The End of The 17th CenturyraelamNo ratings yet

- The Silk Road: Explore the World's Most Famous Trade Route with 20 ProjectsFrom EverandThe Silk Road: Explore the World's Most Famous Trade Route with 20 ProjectsNo ratings yet

- W Cline ReseñaDocument3 pagesW Cline ReseñaSol HeffesseNo ratings yet

- The Making of A Global World NotesDocument3 pagesThe Making of A Global World NotesSaanvi JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Waugh PDFDocument14 pagesWaugh PDFAdrian GeoNo ratings yet

- Moseley2001 Incas AncestorsDocument289 pagesMoseley2001 Incas AncestorsAlexander Chahuasoncco Papel100% (1)

- East Meets WestDocument2 pagesEast Meets WestMissKuoNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument5 pagesSilk Roadapi-309265066No ratings yet

- Silk Road Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesSilk Road Thesis Statementtunwpmzcf100% (2)

- Wembley Calendar 2020Document28 pagesWembley Calendar 2020Redewaan WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - Silk RoadDocument8 pagesGroup 1 - Silk RoadCherubNo ratings yet

- Group 1Document46 pagesGroup 1Lombroso's followerNo ratings yet

- Silk RoadDocument64 pagesSilk RoadudayNo ratings yet

- Arikamedu - An Ancient Port DR Uday DokrasDocument61 pagesArikamedu - An Ancient Port DR Uday DokrasudayNo ratings yet

- Filmes PopcornDocument1 pageFilmes Popcornnocasines4No ratings yet

- Cópia de Book Club FlyerDocument1 pageCópia de Book Club Flyernocasines4No ratings yet

- DetroitDocument13 pagesDetroitnocasines4No ratings yet

- Greenland - Model Presentationv2Document6 pagesGreenland - Model Presentationv2nocasines4No ratings yet

- The Inca - PPTv2Document15 pagesThe Inca - PPTv2nocasines4No ratings yet

- City Girl Vs Country Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan FordDocument312 pagesCity Girl Vs Country Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan Fordnocasines4No ratings yet

- Broken Girl Vs Fix-It Boy Forever Love Bo - Jordan FordDocument358 pagesBroken Girl Vs Fix-It Boy Forever Love Bo - Jordan Fordnocasines4No ratings yet

- Lost Girl Vs Wounded Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan FordDocument280 pagesLost Girl Vs Wounded Boy Forever Love Boo - Jordan Fordnocasines4No ratings yet

- Circular 2021-41 (2021-12-01)Document6 pagesCircular 2021-41 (2021-12-01)AndreasNo ratings yet

- Fermentare PDFDocument90 pagesFermentare PDFIstudor AdrianaNo ratings yet

- CLDocument37 pagesCLSpirou Rox50% (2)

- Procedures and Arrangements ManualDocument5 pagesProcedures and Arrangements ManualNishadYadavNo ratings yet

- Military Review, February 1956Document116 pagesMilitary Review, February 1956Jerry BuzzNo ratings yet

- Prueba - Frenos de ServicioDocument2 pagesPrueba - Frenos de ServicioUlises BarreraNo ratings yet

- Autocross Technical Inspection ProceduresDocument5 pagesAutocross Technical Inspection ProceduresRajat NanchahalNo ratings yet

- Project Management (Heathrow Terminal)Document6 pagesProject Management (Heathrow Terminal)Lekh RajNo ratings yet

- Angol Társalgási GyakorlatokDocument24 pagesAngol Társalgási GyakorlatokBeatrix KovácsNo ratings yet

- Metro Map 2025 - Bengaluru CityDocument1 pageMetro Map 2025 - Bengaluru CityDeepak BhatNo ratings yet

- Emirates Airlines StrategyDocument9 pagesEmirates Airlines StrategyAloha Pn100% (1)

- 21 870 Campbelltown To Liverpool Via Glenfield 20230925 20231007 1Document6 pages21 870 Campbelltown To Liverpool Via Glenfield 20230925 20231007 1Neng RegsNo ratings yet

- Transmicion 4E27EDocument367 pagesTransmicion 4E27ELuis Castro100% (3)

- IXB BLR: TICKET - ConfirmedDocument2 pagesIXB BLR: TICKET - ConfirmedTenzing PhintsoNo ratings yet

- Book 3Document3 pagesBook 3sumit4407No ratings yet

- Transit Oriented Development in India: Mukund Kumar Sinha, Ministry of Urban Development Government of IndiaDocument37 pagesTransit Oriented Development in India: Mukund Kumar Sinha, Ministry of Urban Development Government of IndiaBadr KaziNo ratings yet

- 66 Polymer Modified Asphalt BinderDocument7 pages66 Polymer Modified Asphalt BinderLeni Widiarti LenwidNo ratings yet

- Efaz Et Al 2022 Combined Load Test and Nde Novel Method To Diagnose and Load Rate Prestressed Concrete Girder BridgesDocument16 pagesEfaz Et Al 2022 Combined Load Test and Nde Novel Method To Diagnose and Load Rate Prestressed Concrete Girder BridgesTONY VILCHEZ YARIHUAMANNo ratings yet

- Electronic Ticket Record: Passenger Name(s)Document1 pageElectronic Ticket Record: Passenger Name(s)Chenaulde BoukouNo ratings yet

- Wired Up RoadsDocument14 pagesWired Up RoadsvamshivarunNo ratings yet

- Normal Procedures 737-NgDocument101 pagesNormal Procedures 737-NgAllan Mucken100% (1)

- Zonal Regulations: Chapter-14Document44 pagesZonal Regulations: Chapter-14RB joshiNo ratings yet

- French Pioneers in The West Indies, 1624-1664. Crouse, Nellis Maynard, 1884Document307 pagesFrench Pioneers in The West Indies, 1624-1664. Crouse, Nellis Maynard, 1884Dionisio Mesye100% (1)

- Pont Dalle en Béton Armé (Solid Slab Bridge) I. Hypothèse StructureDocument5 pagesPont Dalle en Béton Armé (Solid Slab Bridge) I. Hypothèse Structureken koemhongNo ratings yet

- Effect of Weight On Stall SpeedDocument2 pagesEffect of Weight On Stall Speedpp2076No ratings yet

- Rano RecruitmentDocument7 pagesRano RecruitmentAdetunji TaiwoNo ratings yet