Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Norwegian Ombudsman

Norwegian Ombudsman

Uploaded by

Mitali KhatriCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Case Against Section 144Document25 pagesThe Case Against Section 144SQUASH13No ratings yet

- Suresh IAS Academy NotesDocument176 pagesSuresh IAS Academy NotesMohamed Harun93% (14)

- Parliamentary Ombudsman in DenmarkDocument16 pagesParliamentary Ombudsman in DenmarkHemantVermaNo ratings yet

- Origin and Evolution of The Ombudsman: ChapterDocument36 pagesOrigin and Evolution of The Ombudsman: ChapterionutNo ratings yet

- The Ombudsman Story: A Case Study in Public Oversight, Natural Justice and State TransformationDocument51 pagesThe Ombudsman Story: A Case Study in Public Oversight, Natural Justice and State TransformationPrasun Tiwari100% (1)

- Ombudsman An IntroductionDocument20 pagesOmbudsman An IntroductionIqra BilalNo ratings yet

- Michael Beloff, QC - MacDermott Lecture On Virtuous Voices of CounselDocument26 pagesMichael Beloff, QC - MacDermott Lecture On Virtuous Voices of CounselRajah BalajiNo ratings yet

- Indian OmbudsmanDocument16 pagesIndian Ombudsmantayyaba redaNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia Faculty of Law: Submitted To: Bhavna Sharma Submitted By: Zene QamarDocument18 pagesJamia Millia Islamia Faculty of Law: Submitted To: Bhavna Sharma Submitted By: Zene QamarZene Qamar100% (1)

- A Descriptive Study On OmbudsmanDocument4 pagesA Descriptive Study On OmbudsmanJasvinder SinghNo ratings yet

- OmbudsmanDocument8 pagesOmbudsmanSurendra CNo ratings yet

- "Corruption and Hypocrisy Ought Not To Be Inevitable Products of Democracy, As TheyDocument16 pages"Corruption and Hypocrisy Ought Not To Be Inevitable Products of Democracy, As TheyAnany UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- 113 113 1 PBDocument18 pages113 113 1 PBWeb BirdyNo ratings yet

- Martial Pasquier and Jean-Patrick Villeneuve, Access To Information in Switzerland FromDocument19 pagesMartial Pasquier and Jean-Patrick Villeneuve, Access To Information in Switzerland FromhoodieprincessreloadedNo ratings yet

- Senate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Beyond Corporate Raiding: A Discussion of Advanced Fraud Schemes in The Russian MarketDocument26 pagesSenate Hearing, 111TH Congress - Beyond Corporate Raiding: A Discussion of Advanced Fraud Schemes in The Russian MarketScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chapter-3 Ombudsman in Comparative and International PerspectiveDocument32 pagesChapter-3 Ombudsman in Comparative and International PerspectiveHemantVermaNo ratings yet

- LeviDocument15 pagesLeviKa MiNo ratings yet

- 16 Macquarie LJ3Document15 pages16 Macquarie LJ3John WuNo ratings yet

- The Definition of Terrorism: A Report by Lord Carlile of Berriew Q.C. Independent Reviewer of Terrorism LegislationDocument52 pagesThe Definition of Terrorism: A Report by Lord Carlile of Berriew Q.C. Independent Reviewer of Terrorism LegislationNeminFideNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.237.34 On Mon, 07 Nov 2022 13:10:06 UT6 12:34:56 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.237.34 On Mon, 07 Nov 2022 13:10:06 UT6 12:34:56 UTCRAhul sNo ratings yet

- Lord Steyn Boydell LectureDocument21 pagesLord Steyn Boydell LectureThe GuardianNo ratings yet

- sourcesDocument6 pagessourcestalysalina9xNo ratings yet

- Does The Proportionality Test Make Judges Too PoliticalDocument13 pagesDoes The Proportionality Test Make Judges Too PoliticalwayomiNo ratings yet

- Reynolds Privilege, Common Law: Defamation and MalaysiaDocument26 pagesReynolds Privilege, Common Law: Defamation and MalaysiaRoneil AbadNo ratings yet

- Reynolds Privilege, Common Law: Defamation and MalaysiaDocument26 pagesReynolds Privilege, Common Law: Defamation and MalaysiaRoneil AbadNo ratings yet

- Letter of The Lords - March 28, 2013Document4 pagesLetter of The Lords - March 28, 2013libdemlordsNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 65 First & Second Quarter - 02 - Salvador T. Carlota - The OmbudsmanDocument18 pagesPLJ Volume 65 First & Second Quarter - 02 - Salvador T. Carlota - The OmbudsmanPatrixia Sherly SantosNo ratings yet

- Review of Counter-Terrorism and Security PowersDocument20 pagesReview of Counter-Terrorism and Security PowersThe GuardianNo ratings yet

- sourcesDocument6 pagessourcestalysalina9xNo ratings yet

- Minaret Controversy SwitzerlandDocument19 pagesMinaret Controversy SwitzerlandMarcel StüssiNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Concept of Ombudsmen in Administrative LawDocument13 pagesEvolution of Concept of Ombudsmen in Administrative LawAbhishek GuptaNo ratings yet

- Gauntlett - Sept 2010 - Middle Temple AddressDocument14 pagesGauntlett - Sept 2010 - Middle Temple Addressbernard.gutman404No ratings yet

- Statutory Interpretation: The Meaning of Meaning: T H M K AC CMGDocument21 pagesStatutory Interpretation: The Meaning of Meaning: T H M K AC CMGSamiul AhmadNo ratings yet

- Order File ELE00040HDocument6 pagesOrder File ELE00040Hbushra gitayNo ratings yet

- OmbudsmanDocument21 pagesOmbudsmanAmudha MonyNo ratings yet

- OmbudsmanDocument16 pagesOmbudsmanTozim Chakma100% (1)

- Lse LLM Dissertation Deadline 2014Document6 pagesLse LLM Dissertation Deadline 2014BuyCheapPapersOnlineUK100% (1)

- 2022 1 X Y HannanDocument13 pages2022 1 X Y HannanMohammad ZubairNo ratings yet

- Role of Ombudsman Institution Over The AdministrationDocument10 pagesRole of Ombudsman Institution Over The AdministrationNaman DadhichNo ratings yet

- Immigration Law ThesisDocument8 pagesImmigration Law Thesispak0t0dynyj3100% (2)

- Mtille - 2012 - Swiss Information Privacy Law and The Transborder Flow of Personal DataDocument10 pagesMtille - 2012 - Swiss Information Privacy Law and The Transborder Flow of Personal Datajendral.hansaNo ratings yet

- 4 International Conference of PHD Students and Young ResearchersDocument11 pages4 International Conference of PHD Students and Young ResearcherspadminiNo ratings yet

- Ebook A Short Introduction To International Law Emmanuelle Tourme Jouannet Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesEbook A Short Introduction To International Law Emmanuelle Tourme Jouannet Online PDF All Chapterkristy.mccrory717100% (13)

- Danish OmbudsmanDocument27 pagesDanish OmbudsmanBinitaNo ratings yet

- SSRN 3387365Document20 pagesSSRN 3387365Prof. Diogo BurlamaquiNo ratings yet

- Press Conference With DG ASIODocument7 pagesPress Conference With DG ASIOPolitical AlertNo ratings yet

- LLM Thesis StructureDocument5 pagesLLM Thesis Structurebrittneysimmonssavannah100% (2)

- UNSWLJ 47 1 Hobbs Young and McIntyreDocument34 pagesUNSWLJ 47 1 Hobbs Young and McIntyreFreeman DelusionNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing Legal Aid in The Nordic Welfare StatesDocument345 pagesOutsourcing Legal Aid in The Nordic Welfare StatesAline Guesser CardosoNo ratings yet

- Hoffmann-Dr OpiniojurisprintedversionDocument23 pagesHoffmann-Dr OpiniojurisprintedversionPradeep GangwarNo ratings yet

- AAM Rationalising Tort LawDocument28 pagesAAM Rationalising Tort LawMicha KamaNo ratings yet

- The Academy of Political Science Political Science QuarterlyDocument36 pagesThe Academy of Political Science Political Science QuarterlyMarknae TuanNo ratings yet

- Judiciary and Good Governanee in Contemporary TanzaniaDocument80 pagesJudiciary and Good Governanee in Contemporary TanzaniaJonas S. MsigalaNo ratings yet

- PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW ProjectDocument5 pagesPUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW ProjectSanstubh SonkarNo ratings yet

- BdgF20valedictory20address20 3Document50 pagesBdgF20valedictory20address20 3kassahun argawNo ratings yet

- Rule of Law in A Free Society Conference Report 1959 EngDocument342 pagesRule of Law in A Free Society Conference Report 1959 EngGunjan ChandavatNo ratings yet

- Developing UK Law of Privacy - Ideas, Considerations & ConcernsDocument95 pagesDeveloping UK Law of Privacy - Ideas, Considerations & ConcernsjoanabudNo ratings yet

- Cultural Hosting 20121230 Customarylaw MohinzDocument21 pagesCultural Hosting 20121230 Customarylaw MohinzISAAC MUSEKA LUPUPANo ratings yet

- Display PDFDocument26 pagesDisplay PDFMansi 02No ratings yet

- Province of Camarines Sur VS Gonzales - G.R. No. 185740Document12 pagesProvince of Camarines Sur VS Gonzales - G.R. No. 185740Charmaine Valientes CayabanNo ratings yet

- The Management of Senior Civil Servants in KoreaDocument36 pagesThe Management of Senior Civil Servants in KoreajinphenNo ratings yet

- What Color Is Your Parachute 2013 by Dick Bolles - Chapter 11 ExcerptDocument24 pagesWhat Color Is Your Parachute 2013 by Dick Bolles - Chapter 11 ExcerptCrown Publishing Group25% (4)

- Statement of Relatives FormDocument1 pageStatement of Relatives FormMary Lenjelly Mandia OsinsaoNo ratings yet

- 42nd Amendment of Indian Constitution Indian PolityDocument2 pages42nd Amendment of Indian Constitution Indian Polityjaivik_ce7584No ratings yet

- The Icfai University TripuraDocument9 pagesThe Icfai University Tripuramrinmay debbarmaNo ratings yet

- Republic Act 8551 Part 1Document37 pagesRepublic Act 8551 Part 1hazel faith carreonNo ratings yet

- TCS & TPSDocument3 pagesTCS & TPSGeorge Khris DebbarmaNo ratings yet

- Annual Report 2011Document144 pagesAnnual Report 2011Manzoor Hussain0% (1)

- CISFDocument32 pagesCISFMohaideen SubaireNo ratings yet

- 2149 (Pol Science - 3)Document11 pages2149 (Pol Science - 3)sajal sanatanNo ratings yet

- LettersDocument126 pagesLettersnadeemtyagiNo ratings yet

- 2 Ltfi'rDocument6 pages2 Ltfi'ranon-401277No ratings yet

- Posts and Pay Scales in Tamil Nadu Governement As On 1st Sep 2003Document342 pagesPosts and Pay Scales in Tamil Nadu Governement As On 1st Sep 2003Dr.SagindarNo ratings yet

- H P Land LawDocument21 pagesH P Land LawGURMUKH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Maharlika Broadcasting Corp. vs. Tagle FFDocument5 pagesMaharlika Broadcasting Corp. vs. Tagle FFAriel AbisNo ratings yet

- FR 24 LctrElecncsComnEnggGNCTD EnglDocument1 pageFR 24 LctrElecncsComnEnggGNCTD EnglTonyStark IMNo ratings yet

- Juco V NLRCDocument2 pagesJuco V NLRCOliveros DMNo ratings yet

- Group1 SubmisionDocument2 pagesGroup1 SubmisionAnil BabuNo ratings yet

- Members of City Boards and Commissions City of BridgeportDocument18 pagesMembers of City Boards and Commissions City of BridgeportBridgeportCTNo ratings yet

- CUTOFFDocument29 pagesCUTOFFONLINE KHOBORNo ratings yet

- Salary Table 2021-Rus Incorporating The 1% General Schedule Increase and A Locality Payment of 15.95% For The Locality Pay Area of Rest of U.S. Total Increase: 1% Effective January 2021Document1 pageSalary Table 2021-Rus Incorporating The 1% General Schedule Increase and A Locality Payment of 15.95% For The Locality Pay Area of Rest of U.S. Total Increase: 1% Effective January 2021adeaNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra Civil Services RulesDocument122 pagesMaharashtra Civil Services Rulessandeep100% (1)

- DMRC Directory 2018 PDFDocument8 pagesDMRC Directory 2018 PDFAditya JainNo ratings yet

- Block 1Document42 pagesBlock 1Abhi Raj BiplawNo ratings yet

- Javier v. Sandiganbayan: G.R. Nos. 147026-27, September 11, 2009Document38 pagesJavier v. Sandiganbayan: G.R. Nos. 147026-27, September 11, 2009Artemis SpecterNo ratings yet

- MC No. 24 Dated August 24, 2017 - 2017 Omnibus Rules On Appointments and Other Human REsource ActDocument1 pageMC No. 24 Dated August 24, 2017 - 2017 Omnibus Rules On Appointments and Other Human REsource Actmelizze100% (2)

- Lecture 3Document40 pagesLecture 3Haider AliNo ratings yet

Norwegian Ombudsman

Norwegian Ombudsman

Uploaded by

Mitali KhatriCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Norwegian Ombudsman

Norwegian Ombudsman

Uploaded by

Mitali KhatriCopyright:

Available Formats

The Norwegian Ombudsman

Author(s): Walter Gellhorn

Source: Stanford Law Review , Jan., 1966, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Jan., 1966), pp. 293-321

Published by: Stanford Law Review

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1227270

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1227270?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Stanford Law Review

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Norwegian Ombudsman'

Walter Gellhornt

Norway's parliamentary ombudsman for civil administration-its Stortingets

Ombudsmann-came into being at the beginning of I963. The accomplishments

of so youthful an institution-as yet neither fully tested nor, indeed, finally

shaped-cannot be appraised confidently. The Norwegian method of handling

citizens' disagreements with public administrators may nevertheless be described,

and an attempt at preliminary evaluation may be useful while the pre-ombuds-

man past is still fresh in observers' minds.

I. THE GENESIS OF THE OMBUDSMAN SYSTEM IN NORWAY

Other Scandinavian countries long preceded Norway in appointing an offi-

cial to serve as an overseer of public administration-Sweden in I809, Finland

in I9I9, Denmark in I952. Even in Norway an ombudsman had since I952

watched against abusive treatment of military personnel.'

No special crisis drew attention to the desirability of matching the Military

Ombudsman with an ombudsman to safeguard the citizenry against civil ser-

vants. On the contrary, an Expert Commission on Administrative Procedure,

whose recommendation in I958 gave the ombudsman idea its greatest impetus,

proposed the new system simply as a safeguard against the possibility of excess,

not as a weapon against abuses believed to be widespread.2

* ? I965 by Walter Gellhorn. The substance of this paper will appear in a volume to be published

by Harvard University Press in I966.

t A.B. I927, L.H.D. I952, Amherst College; LL.B. I93I, Columbia University; LL.D. I963, Uni-

versity of Pennsylvania. Betts Professor of Law, Columbia University.

I. The Military Ombudsman handles an average of 350 complaints per year, all of them involving

disagreements between inferior and superior ranks; most of his "clients" are conscripts. He has power

only to criticize and suggest, rather than to command. An important part of his activity is serving as

the top point of the "representatives' committees," which function in every detachment of thirty-five

or more men to advise the commanding officer about matters of interest to the lower ranks. The Mili-

tary Ombudsman is supposed to carry further the matters not resolved to the satisfaction of the various

representatives' committees. He has no jurisdiction whatsoever over matters not directly involving re-

lationships within the armed forces. Thus, for example, he is not concerned with military procurement

contracts or controversies between the military and civilians. He is assisted by two staff attorneys and

by an advisory committee of six, to whom he may refer matters of "a fundamental character or of

public interest." He visits military installations from time to time to observe the conditions of service

(such as sanitation and recreational facilities) and to talk personally with service personnel.

For further discussion see A. Ruud, The Military Ombudsman and His Board, in THE OMBUDSMAN

I I I (D.C. Rowat ed. I 965).

2. The chairman of the Expert Commission was Terje Wold, President of the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Wold subsequently explained the Commission's recommendation of the ombudsman sys-

tem as follows: "It seems unavoidable at the stage of economic and technical development which, re-

gardless of politics, has been achieved in all modern societies, that ever larger and broader powers shall

be bestowed upon the administrative authorities." T. Wold, The Norwegian Parliament's Commissioner

for Civil Administration, 2 J. INT. COMM. JURISTS 2I, 24 (No. 2, I960). Then he indicated that he and

the Commission shared the opinion of Professor W. A. Robson that "the greater the powers given to

the executive, the greater the need to safeguard the citizens from their arbitrary or unfair exercise."

W. Robson, Administrative Law, in LAW AND OPINION IN ENGLAND IN THE 20TH CENTURY I93, I98

(Ginsberg ed. I959). For further discussion see A. Os, The Ombudsman for Civil AbFairs, in THE

OMBUDSMAN 95 (D. C. Rowat ed. I965).

293

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page 293

The Commission's simultaneous proposal of an exten

tion of administrative procedure aroused no immediat

gestion that Norway emulate the other Scandinavia

ombudsman for civilians attracted lively interest. Offi

profession and businessmen's associations strongly

these groups explicitly declared that an ombudsman w

ficance for them in any immediate sense; he would benefit the "litde man"

rather than the members of powerful bodies like theirs. The labor movement as

a whole was indifferent, though some of its leaders now profess to have been

proponents of the ombudsman plan. Organizations of civil servants (whose

counterparts in Denmark had bitterly opposed the appointment of an ombuds-

man only a few years previously) were quiescent and may even have lent some

support; one of their leaders recalled recently that "we had had connections

with our Danish friends and had found out from them how much the Ombuds-

man had done for civil servants, to their surprise-and so we were and still are

all for the institution." Governmental agencies seemed to be resigned rather than

actively hostile. Many of them expressed belief that already existing judicial and

parliamentary controls were adequate. A few rather resented the suggestion that

their work might be seriously flawed by arbitrariness or carelessness, against

which new protections might be needed. But no unit of the central government

voiced outright opposition.

Finally, in I960, the Cabinet itself put forward a bill to create a parliamentary

commissioner for civil administration, explaining that an ombudsman would

provide quick, cheap redress for persons who were aggrieved by administrative

actions and, at the same time, would perhaps protect public employes against

"quarrelsome persons." He might also "lessen the burden of work for the mem-

bers of the Storting, who now constantly get complaints from private persons

concerning the activities of some administrative authority." In laying the bill

before the Storting, the Government added: "With the standard our adminis-

tration has today, it is indeed not likely that the Ombudsman will find basis

for criticism in any considerable number of cases. Experience both in Sweden

and Denmark has shown that in only a relatively small number of the com-

plaints is basis found for further procedure. But the system may to some extent

contribute to a higher degree of vigilance in the public administration. And

through a longer period of time its effect may be to strengthen confidence in the

public administration and to create a feeling of security in the individual as to

his relations to the public administration."3

Nearly two years of discussion preceded introduction of a partially redrafted

Cabinet proposal in I962. During subsequent debate in the Storting,4 Minister

of Justice Jens Haugland, presenting the Cabinet's views, stressed that the om-

budsman was not to be a "super organ within the central administration," but

3. The quoted matter is a translation of pp. 3-4 of a paper prepared in I963 by Audvar Os of the

Royal Norwegian Ministry of Justice and published by that Ministry in mimeographed form as Doc.

No. 7I, The Ombudsman in Norway.

4. The Storting's debate is summarized under the topic heading "Grievance Commissioner To

Probe Complaints Against Government," in I9 News of Norway, June 2I, I962, p. 95.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 295

would simply "protect the interests of the indivi

that we know are bound to occur within a large

discussion for the then dominant Labor Party, Re

characterized the proposed ombudsman as "a sort

who feel they have been treated unfairly by gove

that he would need "infinite patience and a good

sound judgment and legal knowledge. Representa

for the minority Liberal Party, declared that Nor

conscientious, capable civil service, but that mista

all human institutions and that an ombudsman could

misinterpretation of statutes or lapses in official jud

budsman might greatly help "personnel in expos

"unsubstantiated complaints from habitual querul

It was following low-pitched discussion of this

Parliament unanimously approved adoption of the

argued an urgent need. The machinery of governme

refined rather than drastically remodeled.

In light of previous expectations, the popular resp

was surprisingly intense. The first Ombudsman took

During I963 he registered I,257 cases; during I964

to i,o6o. During his first year in office Norway's Om

smallest population of any of the Scandinavian co

plaints than any of the similar officials in Sweden

II. CHOOSING THE OMBUDSMAN

The Act of June 22, I962, creating the Stortinge

in Section I that the Parliament is to choose the Omb

election, to serve four years until the next election u

5. Representative Ramndal's words probably received especially

then held only twenty-odd seats in the I50-member Storting, he

fluence there. As chairman of the Storting's Justice Committee

many complaints against administrative acts and had become in the

the press and the public, an "unofficial ombudsman." Administrato

concerning the complaints he had received, for he sought sound re

tion. But Mr. Ramndal never pretended that he had either the pr

would enable him to perform the work of an ombudsman in add

among the first, if indeed he was not himself the first, to propos

6.

Pop. in Millions Cases Docketed I963

Norway . ... 3.7 I,257

Sweden ...... 7.6 I,224

Denmark .. .. 4.7 1,I30

Finland .... 4.6 1,029

In both Finland and Denmark the complai

budsmen in those two countries have jurisd

Norway, Sweden has a Military Ombudsman

Norwegian Military Ombudsman's, since he

contracting) in addition to military personnel

7. Law on Stortingets Ombudsmann, June

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page 293

of two-thirds of the Storting.8 Section i also sta

fications demanded for a judge of the Supreme Court"-which means, as a

bare minimum, that he must be thirty years old and have earned a first-class

law degree (laudabilis) from a Norwegian university. While the Storting may

lay down general rules concerning the Ombudsman's duties, he is otherwise to

discharge the responsibilities of his office, according to Section 2, "alone and

independently of the Storting." His salary and pension rights are not fixed in

the statute, but will presumably be adjusted as may be needed to induce accep-

tance by the person the Storting chooses; at the outset they have been placed

on a parity with the compensation and perquisites of a Supreme Court judge.

The first Norwegian Ombudsman is Andreas Schei, a member of the Su-

preme Court at the time of his election.9 A respected lawyer who had served

lengthily in various posts before becoming a judge, Mr. Schei was a nonpartisan

choice acceptable to the entire Storting.10 He began his work in an atmosphere

notably free from rancor-and, so far as a non-Norwegian can assess such mat-

ters, he has lost none of the support that was his in the beginning.

III. LIMITATIONS UPON THE OMBUDSMAN'S POWERS

The Ombudsman's province, the governing statute declares in Section 4,

"covers the Government administrative organs and civil servants and others

in the service of the Government." This does not, however, include authority

to deal with Cabinet decisions, the functions of courts, or the Auditor of Public

Accounts. His duty, "as the delegate of the Storting" and in accordance with

the rules it may lay down is, under Section 3, "to endeavor to ensure that the

public administration does not commit any injustice against any citizen." Debate

preceding the enactment made crystal clear the Storting's disinclination to aban-

don any of its own powers; the Ombudsman, the Storting's agent, was not

expected to act in matters to which his principal had already turned attention.

A. Matters Acted Upon by the Storting

The Storting on November 8, I962, promulgated rules for the Ombudsman's

guidance. Rule 5(3) bars the Ombudsman from dealing with any complaint if

8. This eventuality is regarded as so unlikely that, according to one veteran legislator, "if the time

ever came when two-thirds of the Storting would be ready to discharge an ombudsman, they would

probably simply abolish the office rather than bother to abolish the incumbent."

9. Section I3 provides that the Ombudsman "must not hold any public or private appointment or

office without the consent of the Storting." While the matter has not been stressed publicly, Judge Schei

has in fact been allowed to keep his seat on the Supreme Court, from which he took a three-year leave

of absence.

IO. A leader of the Storting has privately described the election process as follows: The name of a

prominent law professor was put forward, but it was clear that he did not want the post. The Chief

Justice had informally suggested Mr. Schei's availability and qualifications. Mr. Schei was not a poli-

tician; "a politician wouldn't have had a chance." He was not connected with the majority Labor Party,

but had not declared which party he did support. The Election Committee informally inquired of all

parties in the Storting whether anyone was opposed to Mr. Schei. Everybody seemed happy about him.

The Election Committee unanimously nominated him. He was then elected by secret ballot. He had

previously made clear his unwillingness to surrender the opportunity of returning to the Supreme

Court, and that was taken into account when the Election Committee recommended him. Some of those

who voted for him believed that he would find being the Ombudsman both more honorific and more

interesting than being a Supreme Court judge, but the Storting had to leave the choice to him in order

to get the man it wanted for this job.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 297

the subject to which it pertains "has already been considered by

Odelsting or the Standing Committee on Parliamentary Con

of explanation concerning Norwegian parliamentary organiz

this rule's meaning.

The Storting consists of I50 members. After each general

38 of its own members to sit in the Lagting, while the rem

the Odelsting. Legislative proposals affecting citizens' righ

originate in the Odelsting, where they are usually offered

Government-sponsored bills. They are considered separately

and the Lagting and must be adopted by both.1" The Storting s

however, for many purposes, such as making appropriations, e

passing on constitutional amendments, and ratifying treaties. I

rence of impeachment of a member of the Storting, the Supre

Cabinet, the Odelsting commences and prosecutes the proce

Lagting sits with the Supreme Court as the adjudicating bo

The Cabinet consists of the heads of the fourteen ministries

nally a council of advisers chosen by the King, they must be p

the majority of the Storting since they are answerable to it

interpellation at stated hours.14 Cabinet minutes and other

ment actions are referred to the Standing Committee on Parlia

(sometimes called the Protocol Committee), which may brin

any matter in which the Government has apparently exceeded

Rule 5 tells the Ombudsman to abstain from acting when

been "considered" by the Storting as a whole, by the Odel

the Standing Committee on Parliamentary Control. It fails,

how much parliamentary attention is needed in order to co

having been "considered" within the meaning of the rule. T

taken no chances. He has regarded a matter as having had p

sideration if it has passed through the legislative halls at a

swiftly and, one is tempted to say, no matter how unconsc

were of its presence.

I I. A measure upon which agreement is not reached between the two divis

a plenary session of the Storting and can then be passed if a two-thirds majority

12. Only eight impeachment proceedings have occurred in Norway, the most

I3. The ministries are Foreign Affairs, Church and Education, Justice and

Labor Affairs, Social Affairs, Industry and Handicraft, Fisheries, Agriculture

nance and Customs, Commerce and Shipping, Defense, Wages and Prices, and

Affairs. Various more or less independent boards and directorates are subject to

isters; among these are such important bodies as the Directorate of Price Cont

Waterways and Electricity Supply, and the National Tax Assessment Board. A num

activities are, however, carried on entirely outside the ministries, though in s

measure of ministerial influence. The Bank of Norway, which is the central a

controlling banking activities, is the prime example. Certain other credit agencie

Bank and the National Mortgage Bank-have independent managements, but th

by the Auditor of Public Accounts and they also seek appropriations of public

Some publicly owned and operated business operations, like the State Wine an

the State Grain Corporation, similarly function without ministerial superintende

to the Storting for their activities and sometimes in need of public financing.

14. See I. Wilberg, Some Aspects of the Principle of Ministerial Responsibility

DINAVIAN STUDIES IN LAW 243 (I964).

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page 293

Thus, for example, he has refused to deal with a complaint about which a

member of the Storting had addressed a question to a Minister during the

Question Hour.15 He has similarly rejected a complaint about a ministry's action

that necessitated expenditures for which the Storting subsequently appropriated

funds (though without actual notice of the issue raised by the complainant)."6

In the same vein he declined to inquire into a complaint that a ministry had

improperly rejected a bid for public property, after the Storting had consented

to the sale of that same property to another purchaser, though apparently without

accurate knowledge of the complainant's grievance.17

The Ombudsman himself recognizes that drawing the line is not easy; he

has been especially troubled by the question of whether an interpellation, without

more, constitutes legislative consideration of a problem. Some of his most enthu-

siastic supporters think he may have been too ready to abstain from looking at

cases laid before him. Moves are under way to clarify his jurisdiction in this

respect, apparently in the belief that the Storting's prerogatives will not be sub-

verted if the Ombudsman inquires into matters which could have had but in

fact did not have legislative attention.

A related problem arises in connection with the Section 4 command not

to deal with "decisions made by the Cabinet," which are in theory political

decisions subject to parliamentary reaction. In a number of cases complaint has

been made to the Ombudsman that slipshod work in a ministry caused the Cabi-

net to act unwittingly in a manner harmful to the complainant. In all such in-

stances the Ombudsman has said, in essence, that he cannot go behind the Cabi-

net decision and that anyone who wishes to attack it must direct his complaint

i5. Case No. I963-20: The complainant alleged that the Director of Roads had improperly denied

him an appointment as engineer because of his age. A member of the Storting had raised a question,

which had been answered during the Question Hour by the suitable minister. A supplemental question

had been asked by the original questioner, and that was the end of the Storting's consideration. The

complainant's name had not been mentioned in the Storting, but the Ombudsman thought it clear that

his was the case involved. In these circumstances the Ombudsman regarded the matter as having been

"considered" by the Storting within the meaning of Rule 5. Interpellations are a means of the Stor-

ting's controlling governmental activity, he said, and Rule 5 makes no distinctions among the ways in

which the Storting can deal with a case.

I6. Case No. I963-43: The complainant asserted that the Ministry of Fisheries had improperly

subsidized the sale of certain fish and had thereby caused him economic injury because he had to reduce

the price of his unsubsidized fish in order to meet the resulting competition. The Ombudsman noted

that the cost of the subsidy had been included in the Government's budgetary proposals which had sub-

sequently been submitted to and adopted by the Storting. The Ombudsman held that the subsidy system

must therefore be regarded as having been approved by the Storting and as having been removed from

his jurisdiction.

I7. Case No. I963-I0: The complainant alleged that the Ministry of Defense had carelessly dealt

with his application to purchase certain land, which had subsequently been sold to a municipality. The

Storting routinely gave its consent to the transaction, as is required when public lands are sold. Its ap-

proval constituted consideration of the matter to which the complaint pertained and therefore took the

case outside the Ombudsman's jurisdiction. Whether the Storting had had adequate information before

it and, if not, whether the Ministry's failure to state all the pertinent facts had been decisive of the

result, was not for the Ombudsman to say; this was for the Storting itself to judge.

A somewhat similar problem appears in Case No. I963-I6: An organization, B, complained that

the Ministry of Wages and Prices had dealt unsatisfactorily with B's request that increased costs be

taken into account in setting new price levels. Subsequently the Ministry had proposed, and the Stor-

ting had approved, an extension of an existing regulation that would otherwise have expired by the

passage of time. The Ombudsman rejected the complaint because the Storting had already adopted a

law that, by continuing the previous regulation in force, dealt with the subject matter. The question

raised by the complaint was really directed at the basis of the Storting's legislative action.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 299

to the Standing Committee on Parliamentary Control."8 He h

that should a complaint concern a procedural crudity, im

not because it had affected the decision finally made by t

regard the case as within his power.

B. The Functions of the Courts

Section 4 also instructs the Ombudsman not to concern himself with "the

functions of the Courts of Justice." Rule 3 has similarly directed him to ignore

the Labor Court (which passes on disputes arising under collective bargaining

agreements) and tribunals established to deal with landlord and tenant contro-

versies. The ouster of jurisdiction is complete; he is to take no interest in either

the courts' judicial functions or their administrative activities, such as issuance

of marriage licenses.

The Norwegian Ombudsman's lack of power concerning judges resembles

that of the Danish Ombudsman. By contrast, both the Swedish and Finnish

Ombudsmen have authority to consider complaints against the conduct of

judges and other law administrators without differentiation. Because the Nor-

wegian Ombudsman's jurisdiction is so completely and explicitly excluded, his

relationships with the courts have been entirely amicable.

The emergence of the Ombudsman as a watchman against abusive civil

administration has, however, drawn attention to the fact that judges in Norway

are not closely watched by anybody at all. Leading jurists are beginning to give

considerable thought to the question of whether conventional appellate processes

constitute fully adequate safeguards against unseemly judicial manners or in-

attentiveness.

This is not to suggest Norwegians lack confidence in their judges. On the

contrary, the prestige of the judiciary is extremely high, and the power judges

wield in public affairs is correspondingly great.

Vacant judgeships are announced for public competition. Appointees are

drawn chiefly from senior civil service posts, higher ranking public prosecutors,

and the practicing Bar; the average age at initial appointment is about forty-five

in the lower courts and forty-eight in the Supreme Court. Thus, unlike many

European countries, Norway does not have a "career judiciary" in which the

judges enter without experience and in which they advance to more responsible

work as years pass. The Norwegian judges have had considerable exposure to

the world's affairs before assuming office, as well as a good formal education in

their youth.19

Like their American counterparts they have achieved a sort of iudicial su-

I8. Case No. I963-36 is illustrative: A complained to the Ombudsman that a vacancy in a public

office, for which he would have applied if the vacancy had been properly advertised, had been im-

properly announced following Cabinet action based upon a ministry's misinformation. The complaint

was against the Ministry rather than against the Cabinet's decision as such; but the Ombudsman held

that the complaint pertained to the basis upon which the Cabinet had acted and must therefore be ad-

dressed to the Standing Committee on Parliamentary Control.

I9. Appointees to the Supreme Court and to the presidencies of courts of appeals must have earned

a first-class degree (laudabilis) in law. All other judicial appointees must have earned at least a second-

class degree (haud illaudabilis), but most of them have in fact graduated in law with a first-class degree.

ROYAL NORWEGIAN MINISTRY OF JUSTICE, ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE IN NORWAY II0 (I957).

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page293

premacy by setting aside legislative enactments considered

the Constitution, though neither the Constitution nor

has in terms conferred this power.20 Review of administr

also similar to that in the United States. The ordinary law

their own power to invalidate unauthorized actions, those

observance of prescribed procedures, or those based on an

law or in disregard of the evidence. "This applies," an

has written, "to decisions taken on every step of the adm

the smallest local board to the King in Council; any co

example, declare an act by the King to be invalid."'"

But as a practical matter nobody can do anything a

comports himself. If convicted of a serious crime or if phy

cial irresponsibility were to be proved in a civil proceedin

pose (as has almost never been attempted), a judge could

ment before reaching the mandatory retirement age of se

might warrant far less drastic action than removal from

manners, slowness in disposing of cases, and so on-do a

When addressed to the Minister of Justice, he can theore

with a view to issuing a warning; but as a matter of longs

plaints are in fact simply sent to the man complained aga

tion." When addressed to the Norwegian Bar Associat

times a year, complaints about rudeness or slowness have

affected judge, with a request for comment by him. In n

refused to answer. Nothing further has been done in t

Association believes that its manifestation of interest has

individual judges' future behavior.

C. Municipal Afairs

Section 4 of the governing statute directs the Ombudsman to concern himself

with "Government administrative organs," which means the organs of central

government, as distinct from local administration. Sharply distinguishing be-

tween what is central and what is local in modern Norway is, however, virtually

impossible.

The country is large-a thousand miles between northern and southern ex-

tremities, with a coastline variously measured at up to 12,000 miles-but thinly

inhabited except around Oslo and in the southeastern counties.2" The scattered

population makes difficult a purely local provision of services and benefits such

2o. Id. at io8.

2I. A. Os, Administrative Procedure in Norway, 25 INT'L REY. ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCES 67, 7

('959).

22. Theoretically, too, a judge might be prosecuted and fined in a higher court f

office. NORWEGIAN PENAL CODE ? 324 defines as an offense a public official's "inten

perform any service duty or . . . in spite of warning, performing his duty negli

WEGIAN PENAL CODE ? 325 also provides punishment for, among other things, be

proper behavior toward any person during performance of public service." Although

the enforcement of these provisions, a judge's behavior is no doubt weighed by the M

when the question of promoting the judge to a more responsible post arises.

23. The population density as a whole is thirty per square mile, about a twentie

figure, for example.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 30I

as doctors and clinics and, even, roadways. Hence many activi

elsewhere be considered suitable for municipal administration hav

ingredient of central planning, financing, and supervision.

Local government has nevertheless continued ebulliently in

In very recent years consolidations of previously separate mun

produced a manageable number of viable units; until I963 the reco

had included one with a population of only I32. Slightly more than

cities and rural districts now exist, each with power to impose tax

and property, to borrow money, and to maintain an administrativ

control of an elected municipal council. They are responsible f

among other things, care for handicapped and neglected childr

aged; health services; attention to problems of alcoholism; hou

primary education; building supervision; licensing and inspection o

taurants, and sellers of intoxicants; and the conventional local

sanitation and fire protection (but not including police, which has

nationalized). Some municipalities administer rent control pro

public utility systems, and provide extensive recreational facilities.

like a very large area into which the Ombudsman is not to int

impression, however, is inexact.

All local governments are grouped into eighteen counties, pl

Oslo and Bergen, each of which comprises a county in itself.

county is a governor (fylkesmann), appointed by the central g

having permanent tenure. The county governments, which are th

vised by the Ministry of Municipal and Labor Affairs, must appro

cipal decisions such as those involving loans, major purchases and s

erty, and building or land use control. The governor may veto

deemed by him to conflict with existing laws and regulations. Var

fare programs are superintended by central governmental agen

ties, with central guidance and help, may provide services which a

capability of the separate localities, such as construction of hospit

No doubt enough has been said to show the difficulty of identif

purely local administration. A student of Norwegian municipa

cluded that the scope of local governmental authority "from an A

point is very limited."24 Few major decisions, he asserts, are free fr

trol. "Levying taxes, borrowing money, budgeting and account

land use planning, public and cooperative housing, building insp

and rehabilitation programs, and education are some of the lo

he adds, "which are regulated by central government laws and

controls accompanying State loans and grants." When an adven

pality launches a voluntary program of its own without centra

"national legislation often appears to require and regulate the prog

out the country."25

24. S. M. WYMAN, MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT IN NORWAY AND THE NORWEGIAN

OF I954, at 24 (I963).

25. Ibid. Mr. Wyman remarks that local officials have conferred together about seeking to esc

from central control. "However, although the distaste for control is certain, Norwegian municipal of

cials have had as much trouble as their American counterparts agreeing upon which local activitie

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

302 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page 293

Despite the intertwinings of local and central authority, the Ombudsman

must disentangle the threads. The legislative history of the governing statute

shows that municipal administration, no matter how vague its contours, was

to be set apart, unlike Finland where the Ombudsman's jurisdiction embraces

every level of public administration.26

At the same time the statute did not entirely insulate local government from

the Ombudsman's attention. In any administrative matter involving deprivation

of personal liberty he was authorized to intervene whether the administrator

involved was municipally or nationally employed.27 And the statute also left

open the possibility that later rules might authorize the Ombudsman to inquire

into proceedings at the local level if they were to bear on a case already within

his grasp because of a complaint against a national administrative organ.28 Rule

2 as finally promulgated by the Storting has in fact authorized him to look into

any municipal agency's decision whenever "relevant to the consideration of a

case with which he is dealing."

Despite this further blurring of the line between local and central affairs, the

Ombudsman found that 98 of the complaints addressed to him in I963 and 71

of the I964 complaints fell outside his jurisdiction because they pertained to

purely municipal matters.29 Because of this, Storting members are already dis-

cussing empowering the Ombudsman to act on local complaints as freely as on

national matters.

Municipal spokesmen with whom this issue was discussed in I964 were op-

posed to expanding the Ombudsman's scope. They thought existing review

mechanisms entirely adequate. They were embittered, too, by the opinion in

some Oslo circles that local officials, even more than national, needed the Om-

budsman's superintendence. Still, their opposition to coming under the Ombuds-

man's scrutiny seemed not to be very fiery, though some of them wistfully men-

tioned the possibility of having a local ombudsman to deal with local affairs.

D. Discretionary Acts

The Ombudsman is meant to be a safeguard against abusive public adminis-

tration. Does this mean that he is to protest against exercises of power with which

he disagrees, or only against actions so grossly erroneous as to be illegal?

not need the financial support of the national government." This comment recalls President Eisen-

hower's effort to clip the wings of the federal government and to "return to the states" the powers and

functions that were rightfully theirs. A commission of state governors, asked to make recommendations

to the President, could find nothing that they agreed should be returned to the states (and, thus, to

their budgets).

26. The Cabinet in presenting its proposal in I960 had said, in part: "It seems right to proceed

with some care, and consequently natural to delimit the main province to the governmental adminis-

tration. Subsequently experience may show the necessity for a general extension of the Ombudsman's

province to the municipal administration." Os, op. cit. supra note 3, at 9.

27. Section 4 of the governing statute reads in part as follows: "The Ombudsman can deal with

any administrative matter, including municipal administrative matters, concerned with the deprivation

of personal liberty or connected with the deprivation of personal liberty."

28. Section 4 provides in part: "In the rules issued to the Ombudsman the Storting may deter-

mine . . . 3. that in connection with dealing with the individual case the Ombudsman may also take

up the hearing of the case by the municipal administrative organ which has dealt with the case at a

lower level."

29. Some of the matters rejected by the Ombudsman might have been judicially reviewable had

the complainants chosen to go to court. See WYMAN, op. cit. supra note 24, at 12.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 303

The Cabinet, when initially proposing adoption of the om

clearly sought to avoid creating a super-administrator who

sions he considered unsound. It proposed that the Ombudsman'

cize the substance of decisions shall be limited" to issues o

broader sense"; when an administrator has exercised discre

man, like the courts, should strike only at a decision regarded

arbitrary or motivated by unauthorized considerations, but sh

his point of view on the reasonableness and adequacy of the

Many disagreed. The Cabinet's proposal, they said, would

man and the judiciary exactly the same power to deal with

They wanted him to have far more.

The parliamentary committee in charge of the bill finally

what intermediate view. It accepted the Cabinet's position

man "should not be granted a general authority to express h

istrative discretion," but at the same time the committee said

to "review and give his opinion" concerning decisions "foun

reasonable or otherwise clearly in conflict with fair administr

The statute as enacted states the matter slightly differently

the Ombudsman is of the opinion that a decision is invalid or c

able, he may make a statement to this effect." The rules subseq

the Storting, however, recalled the words of the committee re

the enactment, for Rule 9 states in part, "If the Ombudsma

discretionary decision is manifestly unreasonable, or otherwise

with fair administrative practice, he may so declare."

This brief recapitulation sufficiently indicates that the O

blanket authority to reconsider all governmental actions with

dissatisfied. No man, not even an ombudsman, can be omnic

not facilely revise the physician's diagnosis, the bridge builder

the pharmacologist's determination that a drug compound

to health, while simultaneously "exercising plain common s

numerable matters about which honorable, rational, and inform

reached diverse conclusions. The most he can do is to ascertain

ment in each instance was of the kind authorized-in sum, whet

on the considerations contemplated by the empowering statute

understandably related to the pertinent information, whether

by whatever procedural niceties the situation may have dem

During the first year of his activity many of the Ombu

proved fruitless because they bore upon administrative determ

within the permissible range of reasonable judgment. At the ou

man had been unable to distinguish readily between an attack o

decision because "manifestly unreasonable or otherwise cont

ministrative practice" (with which he is supposed to deal)

hand, disgruntlement that a discretionary decision had not

30. The Cabinet's proposal is quoted in Os, op. cit. supra note 3, at I9.

3 1. Id. at 20.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

304 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page 293

plainant's fondest hopes (which have not been entrust

care). At the year's end, however, the Ombudsman saw th

distinctly. "As the lines of policy in the work have becom

has been unnecessary to ask the administrative autho

many complaints involving discretionary decisions as had

in the beginning. Normally there will be insufficient reas

administrative organ unless the complaint alleges pro

particular facts as its basis."32

Meanwhile, though at pains not to declare a judgment t

reasonable" simply because he thinks it may be imperfec

in fact been acting as a mediator between the citizenry a

in many cases that are probably outside his power.

Case Number I963-7I is illustrative. Farmer A had a

Transport to extend a bus service so that it would pass h

him to bring his milk to market. When the Ministry refu

Ombudsman. The Ministry, responding to the Ombudsma

him that the bus service in question already operated at

be covered by a public subsidy; the Ministry was unwillin

deficit. The decision was rather clearly within the Min

budsman nevertheless pursued the matter. He asked the b

added expense would be involved in driving to A's far

revenue would be gained by carrying A's milk. He proffe

data to the Ministry and suggested that the Ministry mig

sider. The Ministry did so. Extended service has now been

day, with the Ministry agreeing to increase the bus oper

sary, which seems unlikely if Farmer A's milk shipment

as he hopes.

Sometimes, too, his eye has caught a bit of evidence th

praisal. For example, in Case Number I963-58, a diabe

the Ministry of Social Affairs had denied his applicati

and public assistance benefits. The Ministry, when asked

Ombudsman a file containing medical analyses and oth

the rejection of D's request was well within the range of

The Ombudsman noticed amidst the papers, however,

necessarily incurred additional heavy expenses because

budsman put the matter before the Ministry once mo

circumstance had been fully considered. The Ministry to

file, made a grant to D to help him meet his expense

closed the case, saying that investigation of the complain

for action by him.

Because he has in actuality been able and willing to ind

matters involving administrative discretion with which

directly, the Ombudsman's good offices are likely to con

32. I963 OMBUDSMAN'S REP. 9.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 305

IV. WHAT THE OMBUDSMAN DOES Do

Much of the preceding discussion has focused on things the Ombudsman

is not expected to do. The important thing, of course, is what he does do.

As already remarked, he is a watcher of national administration-"Govern-

ment administrative organs and civil servants and others in the service of the

Government.""3 As to them he "can deal with cases either at the request of a

person or on his own initiative."34 The record shows that he has ranged very

widely among public agencies, though the Ministry of Social Affairs and the

Ministry of Justice and Police have, between them, accounted for more than

half of all the cases he dealt with on the merits in I963 and I964.

The cases shown in Table I were but a fraction of those docketed. The way

in which the Ombudsman treated matters brought to his notice is set forth in

Table II below, which reveals that approximately two-thirds were dismissed

without reaching the merits."5

Special note may be taken of the many cases dismissed because administra-

tive channels remained open. While the governing statute is silent as to the nec-

essity of exhausting administrative remedies, the Storting's later instructions de-

clare that the Ombudsman should insist upon a complainant's utilizing available

administrative relief unless "particular reasons" warrant taking up a complaint

at once.36

A second large group of dismissals is attributable to "insufficient foundation,"

33. Act of June 22, I962, ? 4. The statute contemplates the possibility of the Storting's later de-

termining "whether a particular institution or function shall be regarded as being Government admin-

istration or part of the service of the Government"-presumably with a view to removing from his ken

various government businesses (like the Aardal and Sundal Aluminum Works) and services (like the

Postal Savings Bank) whose accounts are already publicly audited and which make few decisions of a

formal or semiformal nature. Thus far, however, nothing has been taken out of the category so broadly

stated in the statute. Conversely, ? 3 of the Storting's regulations has removed possible doubt about

the Ombudsman's ability to deal with certain borderline matters by explicitly declaring them to be a

part of "Government administration."

34. Section 5. The statute further provides (Section 6) that a complaint to the Ombudsman "must

be signed and must be submitted within one year from the date on which the official act or circumstance

subject of the complaint took place or was discontinued"; and it must come from someone who "con-

siders himself to be unjustly treated by the public administration," so that a complaint cannot be made

about impersonal wrongs. These limitations upon complaints enable the Ombudsman to slough off

ancient, unmeritorious, and anonymous cases; but nothing prevents him from taking up "on his own

initiative" a matter brought to his notice by a defective complaint.

35. Many dismissed cases required substantial work in the Ombudsman's office before the ground

of dismissal became apparent. Correspondence and file analysis were often necessary, and in some in-

stances formal opinions had to be written, as in the matters that were ultimately rejected because they

had already received some measure of legislative attention. Unlike those reached on the merits, how-

ever, the dismissed cases stopped short of asking officials for their opinions and justifications of the

matters involved in complaints.

36. Rule 5 provides: "If the complaint concerns a decision which the complainant according to

administrative law or practice has a possibility to bring before a higher administrative organ for re-

consideration, the Ombudsman shall not deal with the complaint unless he finds particular reasons for

doing so without delay. The Ombudsman shall advise the complainant of the possibility of his having

the decision reconsidered by an administrative organ. If the complainant is barred from demanding

such reconsideration because he has exceeded the time limit allowed for doing so, the Ombudsman

shall decide whether, in view of the circumstances, he should nevertheless deal with the complaint."

Two conditions have led the Ombudsman to deal with the merits even when administrative review

remains available: "One is that the complaint is clearly without justification, so that nothing can be

gained by suggesting that the complainant first utilize his right to appeal . . . . The other is when

the urgency of the matter renders it unreasonable to require the complainant to return to the adminis-

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

306 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. I8: Page 293

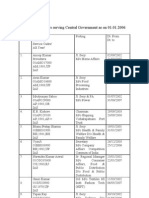

TABLE I. GOVERNMENT AGENCIES INVOLVED IN CASES DEALT WITH ON THE MERITS

I963 I964

Ministry of

Social Affairs ............................ IOI 90

Justice and Police ............. ............ 99 I27

Transport ............................... 37 33

Church and Education ......... ........... 3I 26

Finance and Customs .......... ........... 23 3I

Municipal and Labor Affairs ....... ........ 22 10

Agriculture .............................. 2I 2I

Wages and Prices ....................... . I3 3

Fisheries ................................ 9 4

Defense ................................. 7 3

Commerce and Shipping ........ .......... 5 3

Industry and Handicraft ........ ........... 5 4

Foreign Affairs ................. .......... 3 0

Family and Consumer Affairs .......o....... oo

Other Administrative Bodies ........ ......... 26 I3

Total .................................. 402 368

reflecting the Ombudsman's statutory power

sufficient grounds for dealing with a complain

to "dismiss a complaint which he finds obvious

authority is a desirable protection of ombudsm

ally unstable complainants.

The table below shows also that the Ombu

reason to proceed on his own motion-eightee

teen in I964.37 As yet no cases have been referr

legislature, a possibility envisaged by Rule 5:

receives from the Storting or Odelsting, he

Storting or Odelsting." Persons close to the

trative appellate channel. If the decision is unfavorable to th

that he still has a right of administrative appeal." I963 OMBU

A Ministry of Justice official added during a discussio

writes a prisoner that he must go through administrative

on, he may simultaneously say to us informally, 'what ab

we have a rather clear impression of the Ombudsman's react

acted on a case."

37. Self-initiated cases thus far have been no more spectacular in nature than in numbers. Ex-

amples: (i) An aspirant to a teaching post wrote a newspaper that the final date for applying for a

certain vacancy had been the very date on which the existence of the vacancy had first been officially

announced. The Ombudsman inquired. The Ministry of Education acknowledged having made a mis-

take that would be guarded against in the future. (2) A lawyer wrote a newspaper about a ministry's

slowness in responding to his communication. The Ombudsman inquired. Two days later the lawyer

received his answer. (3) A publicly employed physician wrote a newspaper that he planned to work}

only a limited number of hours in the future because income taxes ate up all his additional earnings.

The Ombudsman asked the physician's superiors to speak to him concerning the performance of his

duties. The physician was spoken to. He said that he had been misunderstood.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 307

that such referrals will never occur. They foresee that

a matter investigated at legislators' behest would becom

debate, and in the end damage the Ombudsman's non

TABLE II. DISPOSITION OF DOCKETED MATTERS

I963 I964

Complaints received .1257 io6o

Cases initiated by Ombudsman .i8 i6

Total docketed ................................... I275 1076

Dealt with on the merits .402 368

Added information asked of complainant .5 0

Dismissed . .868 708

a) Outside jurisdicton .393 293

Judicial activities .......................... I47 I0I

Considered by Storting .20 7

Cabinet decision. I3 5

Municipal matters .98 7I

Other (private affairs, etc.) .I5 I09

b) Filed tardily .97 52

c) Administrative remedies available .I28 I36

d) Insufficient foundation .9I 6i

e) Withdrawn by complainant .48 40

f) Anonymous or incomprehensible .20 3

g) Not real complaints (inquiries, etc.) .9I I23

The sources of complaints are diverse, but civil servants (including school-

teachers) have comprised one of the largest groups. They have brought to the

Ombudsman their unresolved grievances about appointments, promotions, salary

classifications, determination of pension rights, and other employment condi-

tions.38 The inmates of penal institutions have been another large category; they

accounted for 4.5 per cent of the complaints received in I963 and i6.i per cent

of those filed in I964, thus proving once again the value of word of mouth adver-

rising. Attorneys have signed about 3 per cent of the complaints, though they

38. A top-ranking officer of a civil servants' organization remarked recently: "Discretionary deci-

sions about promotions and non-promotions are going to be the most important things from our point

of view, even though the Ombudsman can perhaps only comment and not criticize. We have always

been able to take up grievances with a committee of the Storting, but what would happen there was

too predictable; political considerations would make it most unlikely that a Government action would

be criticized. Therefore very few of our people bothered to go to the Storting. Now they will give the

Ombudsman a try. Many of the cases submitted to him will not be manifestly unreasonable, and so he

will probably not interfere. But we have the feeling that ministries are already taking more care in

personnel matters than some of them did before the Ombudsman was around to ask them questions."

Political considerations occasionally intrude offensively into the career civil service, according to a

number of Norwegian observers. The non-political director of a scientific department reported, for

example, that inquiry has been made of him concerning the partisan affiliations of subordinates he has

recommended for promotion. The chief of a civil servants' union flatly expressed his union's belief that

appointments to key positions are too often influenced by party considerations that distort judgment

about the candidates' other qualifications.

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

308 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. i8: Page 293

are thought to have prepared many others that were filed d

Attorneys are also believed to have referred many querulen

thus relieving themselves of an unwelcome burden by tran

official grievance bureau.

Table III below categorizes complaints so far as has see

not show the character of the individual complainants outs

gories. Almost without exception, spokesmen for organi

speak rather patronizingly about the users of the Ombudsm

ing them as "little people" or as "the ordinary man in the

too poor or too ignorant to have a lawyer" or as "men who

tions that know where to go" or, simply, as "cranks." These characterizations

fit the facts in many and probably most instances, but examination of the Om-

budsman's records reveals well-established business firms and substantial citizens

among his clients, along with the small fry, the bewildered, and the chron-

ically combative. Among them, too, have been many claimants of disability bene-

fits and other forms of social insurance. Contrary to the practice in other Scan-

dinavian countries, in Norway these cases are not usually referable to a special

administrative tribunal; consequently they consume much more of the Nor-

wegian Ombudsman's time.

TABLE III. SOURCES OF COMPLAINTS

I963 I964

Complaints Per Cent Complaints Per Cent

Civil Servants. II3 9.0 Undetermined

Prisoners ..... .. 57 4.5 I7I i6.i

Attorneys .36 2.9 3I 3.0

Mental Hospitals. I5 I.2 17 i.6

Organizations. I4 I.I Undetermined

Undifferentiated .IO22 8i .3 84I 79.3

Total ............... I1257 IOO.O I o6o I 00.0

When acting on a complaint, the Ombudsman

Unlike the ombudsmen in Sweden, Finland, a

that a civil servant be prosecuted or subjected to

is the power of reason alone, unaided by the pow

Section io of the governing statute says simply:

to express his opinion in matters which come

Ombudsman is of the opinion that a decision is i

he may make a statement to this effect." Rule 9

may also, if circumstances justify, advise an adm

sation should be paid unless a new decision can r

39. He may, however, under ? IO "inform the public pros

steps he thinks should be taken. Whether steps are then taken

than the Ombudsman. He has not yet had occasion to give info

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

January I966] NORWEGIAN OMBUDSMAN 309

The Ombudsman's capacity to counsel rather than co

for Norway's needs and consonant with its traditions. The

vants, both local and national, is extraordinarily high. Tru

mental circles is generally believed to be a rarity, unlikel

budsman.40 And while Norway's penal code, like Swe

fines as a crime an official's acting inattentively, negl

rudely,4' Norway has not emulated the Swedish and Fin

cuting judges and other public employes for their mi

Ombudsman's inability to initiate criminal proceedings

A review of the action taken upon the complaints before

been able to exert a significant influence even though lac

ment. This can be demonstrated both statistically and ane

The statistics indicate that as of March i, I965, invest

pleted and the files closed in 7I5 cases dealt with on the m

I963. In 5IO cases nothing was found that led to a change

called for comment by the Ombudsman. In 95 cases, ho

tors changed their decisions while the complaint was unde

obviating the need for further action by the Ombudsman

followed the mild policy of informing administrators

have unearthed new facts or considerations, so that do

reexamined by those who made them in the first place

the Ombudsman voiced a criticism or made a request

either in terms of the specific action against which comp

in more general terms for the future.

In only 2 out of iio instances, so far as can be ascerta

man s advice not been fully accepted. In one of these

quested the Ministry of Education to grant compensati

portation expense involved in his serving at a place distan

several previously scattered schools (including the one

assigned) had been consolidated at a central location. T

Having investigated the teacher's complaint, the Ombu

the Ministry was statutorily obligated to compensate t

ommended that the Ministry compute the amount to

adhered to its view that no payment was due, leaving the

4o. Public confidence was somewhat shaken in I963 by disclosure of

involving a single official in the Ministry of Industry. The scandal came t

(August-September I963) that the Labor Party had been out of power

has led to speculation that if the doors of governmental closets were flun

tons might be found.

On the other hand, even completely unconfirmed gossip about police

not heard in I964. A high-ranking police officer did make a "confessio

a traffic policeman had investigated an accident involving the motorc

attache. Upon learning that the attache's diplomatic immunity preclude

policeman terminated the investigation. The American then gave the po

two cartons of cigarettes. This was the only instance of "police corruption

Oslo or elsewhere could recall.

4I. See note 22 supra.

42. For discussion of the Swedish and Finnish practices under simil

The Swedish Justiticombudsman, 75 YALE L.J. I (I965), and Finland

PA. L. REV. 327 (I966).

This content downloaded from

14.139.241.51 on Tue, 27 Feb 2024 13:32:22 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

310 STANFORD LAW REVIEW [Vol. I8: Page293

recover the damages the Ombudsman (but not the Minist

fered.43 In the second case a man previously held in a tr

holism was arrested on fresh charges soon after his rele

alcoholism is, under Norwegian law, first committed to a workhouse; subse-

quendy, if found to require more extended therapy, he may be transferred to a

different place of detention. In the present instance the rearrested person was

sent at once to the treatment center, for which he had acquired a lively distaste.

The Ombudsman agreed with the complainant that he had been lodged in the

wrong institution. The Ministry of Justice acknowledged not having observed

the letter of the law, but expressed no remorse for having popped the recidivist

into the treatment center at once instead of by way of the workhouse (which hap-

pened to be five hundred miles away). Thus far neither the Ombudsman nor

the Ministry has surrendered. The Ombudsman can, however, do nothing fur-

ther except report the matter to the Storting or urge the Ministry to seek an

amendment to the present statute pertaining to detention of alcoholics.

The minor setbacks just described are more than offset by administrators'

acceptance of the Ombudsman's counsel. Like the defeats, the triumphs are not

spectacular. None the less they suggest, in the aggregate, that the Ombudsman

has served a need that was real despite its not having been widely felt before he

began his work. This may perhaps best be illustrated by reviewing clusters of

cases with which he has dealt.

Social insurance cases. Controverted claims for pensions or disability benefits

flow through the Ministry of Social affairs at the rate of more than ten thousand

per year. While the Ministry's decision is accepted as final in most instances, a

few disputes remain unresolved. Judicial review has always been available to

dissatisfied claimants, but recourse to the courts has been rare. As shown by

Table I, however, recourse to the Ombudsman has been fairly frequent; a case

may be taken to him even though a judicial remedy is available but as yet un-

sought. He has infrequently found fault with the Ministry's conclusions, though

he has in a few cases stimulated reconsideration that has led the Ministry itself

to change some previously unacceptable decisions.44

The way he has handled the cases before him has earned the Ministry's hearty

respect. "We think he is only an amateur in the social insurance field," one high

official said somewhat loftily, "but he is a very intelligent amateur. He asks good

43. Apparently the teacher and his organization decided not to pursue the matter further.

If the Ministry had paid as advised by the Ombudsman, its having done so might (at least in

theory) have been held improper when its accounts were subsequently scrutinized by the Auditor of

Public Accounts. While the Auditor's criticism would then be, in form, a criticism of the Ministry, it

would in fact be a criticism of the Ombudsman. This is an anomaly in the Norwegian system, for,

while the Auditor of Public Accounts may in no instance be criticized by the Ombudsman, see section

III supra, the Ombudsman's judgment is thus subject to being reviewed by the Auditor. The possi-