Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bose RootsCommunalViolence 1982

Bose RootsCommunalViolence 1982

Uploaded by

abdulaliislam111Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bose RootsCommunalViolence 1982

Bose RootsCommunalViolence 1982

Uploaded by

abdulaliislam111Copyright:

Available Formats

The Roots of 'Communal' Violence in Rural Bengal.

A Study of the Kishoreganj Riots,

1930

Author(s): Sugata Bose

Source: Modern Asian Studies , 1982, Vol. 16, No. 3 (1982), pp. 463-491

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/312117

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/312117?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Modern Asian Studies

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Asian Studies, x6, 3 (1982), PP. 463-491. Printed in Great Britain.

The Roots of 'Communal' Violence

in Rural Bengal

A Study of the Kishoreganj Riots, 1930

SUGATA BOSE

University of Cambridge

I. Introduction

IN 1947 the fabric of Bengali rural society woven together by a c

language and a syncretist popular culture was torn asunder on li

religion. During the final two decades of colonial rule in In

Ganga-Brahmaputra-Jamuna deltaic tracts of east Bengal increas

became the scene of tension and violent conflict between a Muslim

peasantry and a predominantly Hindu landed gentry. The conflict

between rival 'lites in a plural society over government jobs and

positions of vantage in the legislative arena has been a subject of

scholarly studies in twentieth-century Bengal.' Successive 'legislative

attacks' of one status and interest group upon another have been

carefully identified and documented, and their significance assessed.2

The inner dynamics of the struggle in the countryside and the periodic

outbursts of 'communal' fury that rent rural Bengal during this period

have not come under the same systematic investigation. Yet, without

the agrarian dimension to the Hindu-Muslim problem in Bengal, the

politics of separatism would in all likelihood have proved ineffectual and

been washed away by the strong tide of a composite nationalism. In

1906-07, at the time of the Swadeshi movement, the riots atJamalpur in

Mymensingh and in Comilla had shown up what was to be the Achilles'

I am grateful to Dr C. A. Bayly, Mr Charu C. Chowdhuri and Professor Eric Stokes

for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Responsibility for views expressed

and errors if any rests with me.

Abbreviations: GB= Government of Bengal; WBSA= West Bengal State Archives

BSRR= Bangladesh Secretariat Record Room.

1 John H. Broomfield, Elite Conflict in a Plural Society: Twentieth Century Bengal (Berkeley,

1968); Shila Sen, Muslim Politics in Bengal (New Delhi, 1976).

2 Broomfield, Elite Conflict, pp. 284-95-

oo26-749X/82/o5o6-o2o8$o2.oo ? 1982 Cambridge University Press

463

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

464 SUGATA BOSE

heel of mass nationalism in Bengal.3 In

and elsewhere in east Bengal together

frightened a majority of the Hindu na

favour of a partition that forty ye

resolutely opposed.4

It is proposed here to probe the

twentieth-century Bengal by making

bances in Kishoreganj subdivision of

Apart from localized violence in rura

Hindu-Muslim rioting had been an

mainly upcountry people and not

however, or perhaps a little earlier, inc

part of Muslim peasants against Hindu

became almost a regular feature in

instances of incendiarism and looting o

be cited for this period, it is possible to

widespread disturbances-in Kishoreg

circle of Dacca district in 1941,5 and fin

Noakhali and Tippera on the eve of i

The Kishoreganj disturbances ought

serious claim on the historian's attenti

agrarian policy they surpassed the

nineteenth century.6 They also foresh

fateful decade of colonial rule which s

demand. At the same time, having

Pakistan cry was raised, they give us a

agrarian content of Hindu-Muslim riots

3 For a discussion of these riots, see Sumit Sar

Igo3-1908 (New Delhi, 1973), PP- 444-64; also,

Unrest in Bengal, 1875-I908' (unpublished C

4 Not only the communalist Hindu Mahasabh

leaders saw no hope of reconciliation betw

legislators voted overwhelmingly in favour of

Chandra Bose who together with the Muslim

Hashem tried till the last to secure a united B

5 In the riots in the rural areas of Dacca in 194

in a matter of five days. 2519 households (join

affected by looting or arson. See, Report of the Dac

Bengal (Alipur, 1942), p. 33-

6 For accounts of the Deccan riots, see I. J. C

(Oxford, I970), Ch. I; I.J. Catanach, 'Agrarian

India' in Indian Economic and Social History Rev

(March 1966); Ravinder Kumar, 'The Deccan Ri

(August 1965), pp. 613-35-

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 465

taken up for study in isolation, it might be rather more difficult to

separate the strands of class conflict and communal feeling for analysis

and to assess the precise roles and interaction of the two forces. It is

hoped that a study of the Kishoreganj disturbances would enable us to

form a clearer idea of the nature of the economic grievances and

agrarian class conflict that fed the communal fire.

II. The Setting: Agrarian Social Structure in Mymensingh

Mymensingh, the largest district in Bengal,7 was located almost in the

centre of the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Jamuna delta. Muslims accounted

for nearly three-quarters of its vast population at the turn of the century,

and their proportion in relation to the Hindus steadily increased.8 The

superior revenue-collecting rights over the bulk of the land in Mymen-

singh were held by a few big zamindars, a great majority of Brahman

and Kayastha Hindu families but also a handful of Muslims. There was

not much subinfeudation of rent-collecting rights and tenures rarely

went below the second degree. The Hindu bhadralok of the district

largely filled the ranks of the petty talukdars-some of whom were

landlords under the permanent settlement paying revenue to govern-

ment, and the rest tenure-holders acting as intermediaries in the

rent-collecting structure between superior zamindars and raiyats. There

were some who took service in the zamindari kachharis or were pleaders

and mukhtears in the mofussil towns, or schoolmasters, doctors and

clerks, but few of these men did not have ties with the land.9 The battle

over occupancy right and rent enhancement between these rentiers and

the raiyats had been fought and lost by the former in the later nineteenth

century.'0 The Bengal Tenancy Act of I885 modified the settlement of

1793 in important ways to give a large body of actual cultivators a

7 6300 sq. miles in area with a population in 1911 of 4,526,422, F. A. Sachse,

Mymensingh District Gazetteer, 1917 (hereafter referred to as M.D.G.)

8 Hindus Muslims

1901 1,o088,857 2,795,548

1911 ,161,585 3,324,146

1921 1,174,015 3,623,719

1931 1,174,328 3,927,552

Census of India, Bengal, Tables, 1901, 1911, 1921, 1931

9 M.D.G., pp. 61-2.

10 K. K. Sengupta, 'Agrarian Disturbances in Nineteenth Century

VIII, I (March I971), PP. 192-212. For the agitation in Mymensingh

203-4.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

466 SUGATA BOSE

measure of tenurial security and mode

District Gazetteer (1917) reported that

collected and that there were never any e

rent, especially by the smaller gentry, bec

and, if figures from Wards' and Attac

index, after 1907 there was scarcely a

reached 50 per cent of the total rental.'3

rental income and rising prices, the depen

source of income acquired enhanced signi

zamindars as well as the petty talukdars,

locally called 'lagni karbar', literally tr

but really nothing but usury pure and si

As in other districts in Mymensingh, th

between legal status and social reality.

that some noncultivating rent-receiver

registered as raiyats in the district se

majority of actual cultivators got the sta

against eviction and rent increase. Ind

would have occupancy right by custom.'4

holding was 2.67 acres.15 At the time o

the lands held by raiyats were sublet to u

held raiyati holdings as well.16 F. A. Sa

estimated that some 3 per cent of the to

produce-rents. Of this, a small fractio

raiyats or under-raiyats who paid a fixed

the rest by bargadars (sharecroppers) wh

year's crop. The bargadars, Sachse pointed

themselves.... The bargadar is usually

renting his homestead and one or two plot

landlord on a cash rent'." The landless

said to be 'limited'.'8 The Mymensingh

" The Tenancy Act was the government's respon

that swept east Bengal in the i87os and the early 18

of high landlordism in Bengal. According to the Ac

to a tenant who had cultivated any plot of land in

rent could be enhanced only once in 15 years on

more than 12.5 per cent of the existing rent.

12 M.D.G., p. 64.

13 Annual Reports on the Wards' and Attached Est

pp. 1 I3-15.

14 F. A. Sachse, Final Report on the Survey and Settlement Operations in the District of

Mymensingh, 19o8-1919 (hereafter referred to as M.S.R.), pp. 43-5.

15 Ibid., p. 25. 16 Ibid., p. 44. 17 Ibid., p. 45. 18 M.D.G., p. 86.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 467

labour from Bihar and the neighbouring districts of Faridpur, Jessore

and Tippera at harvest time. With the building up of demographic

pressure over time the ranks of a marginalized peasantry swelled and

landlessness increased.

The agrarian social structure of Bengal, it will be seen, differed

significantly from the area zamindar and village controlling dominant

peasant pattern of northern India or of the dry zone in the south.

Contrary to the existing view of a jotedar-bargadar dichotomy in

Bengal,19 big jotedars cultivating substantial lands through dependent

sharecroppers were to be found only in northern Bengal and in the

Sunderbans in the south where large credit advances from rich,

enterprising farmers had been required to clear the scrub and jungle

for cultivation during the nineteenth century. J. C. Jack in his classic

'Economic Life of a Bengal District' (1916) wrote of the east Bengal

district of Faridpur: '... the cultivators are a homogeneous class'.20

Sachse found that the land in Mymensingh was rather more unevenly

divided than in Jack's district, but nowhere except in a small pocket in

Dewanganj were there any substantial landholders who could be

regarded as village-controllers, not to speak of'defacto village landlords'.

The Settlement Report sets out the picture of stratification within

'agricultural families':21

TABLE I

Average cultivated Gross income

land per family per family

Families with net profit of Rs 800

or more: 30,000 or 4 per cent I2 acres Rs oo000

Families with net profit of Rs 240

or more: 270,000 or 36 per cent 5 acres Rs 415

Families with net profit nil

or subsistence ryots: 450,000 or 6o per cent 2 acres Rs 166

19 The jotedar thesis gets its most rigorous formulation in Rajat and Ratna Ray,

'Zamindars andJotedars: A Study of Rural Politics in Bengal', in Modern Asian Studies, 9,

I (February 1975), pp. 81-102. See also, Sunil Sen, Agrarian Struggle in Bengal (Calcutta,

1972), Ch. I, and Ratna Ray, Change in Bengali Agrarian Society (New Delhi, 1979),

Epilogue.

20 J. C. Jack, Economic Life of a Bengal District (London, 1916), p. 8I. The word 'jote'

simply means cultivation or tillage and the majority of the 'jotedars' of east Bengal may

best be described as peasant smallholders. 'Jotedars' in the sense of 'de facto village

landlords' were to be found in certain peripheral regions rather than in the old settled

tracts of Bengal.

21 By 'agricultural families' the Settlement Officer meant ryot families. The legal

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

468 SUGATA BOSE

Did such inequalities in the landholding

time congeal into separate classes over a

a number of reasons whether a distin

separate itself out in the first half o

anthropological work on rural east Beng

a process of unilinear class differentiati

directional mobility in peasant society w

households and the rise of relativel

remember that even during periods of

nineteenth century and the Second Wor

prices lagged behind the all commoditie

the chief cash crop of Bengal, never en

as did, for instance, cotton and wheat i

While there was little scope for serious c

to develop within peasant society, th

Bengal in general and of Mymensingh in

cultural identity which included relig

identical set of tenurial, credit and mar

external economic relations, we shall ar

category of 'ryots' would include not only peasa

had their lands cultivated by under-raiyats and

the figures give in the table are the result of a

settlement records and cess records. According

cess ryots paid cess on a rent of more than Rs 22

more than Io acres; but Sachse decided to includ

agricultural families and assumed that 30,000 f

The table therefore does not quite present a

peasantry. It is only used in the absence of bet

p. 25.

22 At a much later period, viz. the I96os, Bertocci discovered an inter-generational

circulation of economic and social status among households of different landowning

classes, cited Peter J. Bertocci, 'Structural Fragmentation and Peasant Classes in

Bangladesh', Journal of Social Studies, 5 (October 1979), p. 56. Abu Abdullah writing on

the agrarian structure in Bangladesh in the mid-1970os accepted Shanin's point about

'the barriers to polarization set up by the internal structure of peasant society' with a

caution that over emphasis on this aspect could lead one to underestimate 'emergent'

class conflicts and change processes in rural society, Abu Abdullah et al., 'Agrarian

Structure and the IRDP Preliminary considerations', in Bangladesh Development Studies,

IV, 2 (April 1976), p. 217. The question of individual mobility of peasant households in

the first half of the twentieth century is more difficult to fathom, but can at least be

partially probed by studying the pattern of land alienation from registration records in

conjunction with settlement records of selected villages.

23 See Prices Enquiry Committee Report (1914) and the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry

Committee Report (1929) (hereafter referred to as BPBECR), cited B. B. Chaudhuri, 'The

Process of Depeasantization in Bengal and Bihar 1885-1947', in Indian Historical Review,

2, I (1975), PP. 115-16.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNAL' VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 469

able degree of cohesiveness that the peasantry of east Bengal displayed in

political action.

The tenurial structure of Mymensingh has already been sketched; but

with the close of the era of high landlordism by the later nineteenth

century, rent as a means of surplus appropriation became less signifi-

cant. In the early twentieth century the Mymensingh raiyat's rent

proper was held to be 'the least important factor in his budget'.24 Bengal

agriculture was, however, drawn into the web of an export-oriented

colonial economy. Small peasant producers of east Bengal raised cash

crops for the world market on their minuscule holdings. The market and

the credit system which kept the peasant family alive and helped to

reproduce the small peasant economy were more important channels of

the drain on the Mymensingh peasant. Yet, the conventional belief

among British administrators was that the jute cultivator of east Bengal

thrived on a buoyant cash-crop economy. Sachse was surprised to find

that in spite of the inflated prices in the years preceding the First World

War and the 'influx of crores' into Mymensingh, 'the standard of living

has not gone up to an appreciable extent' while indebtedness had

increased. He put it down to 'the absolute improvidence of the people

and their fondness for litigation',25 though rather incidentally he

mentioned other more important factors as well. It is obvious that to find

an explanation of the continued poverty and indebtedness of the

Mymensingh peasantry we must delve deeper.

In east Bengal, where in the later nineteenth century rapid extension

of cultivation was taking place, the margin appears to have been

reached by the second decade of the twentieth century. The census of

1921 and folk literature of the time depict the crowding out of cultivators

from east Bengal to Assam.26 Sachse reports in 1919 that in Mymen-

singh cultivation had 'almost reached its full limits'.27 The land was

already supporting 1.3 persons to the acre. Subdivision not only of

holdings but of individual plots between three and five brothers was

proceeding at such a rapid pace that it was estimated if the settlement

24 M.D.G., p. 64. As B. B. Chaudhuri has pointed out, the volume of rent burden of

peasants in their impoverishment has often been exaggerated. The size of rural

indebtedness was estimated by the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee in

1930 to be Rs ioo crores, while the 'gross rental' was estimated by the Land Revenue

Commission in 1940 to be only Rs I 1.32 crores, Chaudhuri, 'Process of Depeasantiza-

tion', p. io8 fn.

25 M.S.R., pp. 28-29.

26 Census of India, 1921, Vol. V, Bengal, Pt I, pp. 132-3. See also a fascinating folk poem

by an immigrant to Nowgong, Assam from eastern Mymensingh, Md. Abdul Hamid,

Pater Kabita (Juriya, Assam, 1930).

27 M.S.R., p. 29.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

470 SUGATA BOSE

operations had come five years

mile would probably have been

In attempting to raise the va

holding, the Mymensingh peasan

often long-term fluctuations in

1907-12 boom injute prices, ther

was not until 1922 that prices p

brief boom reached its peak in 1

taper downwards and plummete

it reached an all-time low in 1

slump until as late as 1937-38.30

roused in the east Bengal coun

returned. Indeed, it is probabl

value forjute throughout the pos

1913.1 In 1907 the rustic poet

wonderful qualities ofjute, or na

Look he cried, the jute cultivato

instead of the traditional bamboo

of strong Joanshahi timber.3

cultivator became the burden

embraced the fickle jute and sen

Rangoon.33 The bane of over-

indebtedness, the profits of the

28 Ibid., p. 27.

29 For the movements in the price of r

30 Ibid.; and Chaudhuri, 'Process of

31 Capital, 15 August 1929, cited, BP

32 Balo bbai, nailyar shaman kirshi n

Nailya bepari, satkhanda bari,

Joanshaiya thuni diya banchhe cho

(Say brother, there is no crop like

From the memory of Mr Charu C. C

33 One poem describes a meeting of a

arrivistejute with paddy presiding:

Dhanya bale duiti katha shuno mor

Tomader katha shuni aphshos hoiach

Chharilo tomader hoilo durgati

Rangoon deshete jano amar bashati

Gariber lagia ami eshechhi sada

Kinia khailo dekho oishab gadha

Nalita dekho kata jatan karilo

Amay hela kore chhariat dilo

Tomra amake dekho karilet raja

Hoitechhe krishaker kato jeno shaja

Abdul Samed Mian, Krishak Boka (Ah

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF ' COMMUNAL' VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 471

high costs of jute cultivation were harped on-themes that are

beginning to be taken seriously by the economic historian of today.34

What the poetaster did not appreciate was that by the 1920s growing

jute was hardly a matter of choice.

Sincejute began to encroach upon a sizeable portion of the cultivated

acreage, Mymensingh made up its deficit in rice by imports from

Burma. Our area of special interest, Kishoreganj subdivision, was able

to market jute and some sugar-cane and fish, all the paddy and mustard

that was produced being consumed locally.35 Jute was an expensive

crop to cultivate, especially because of its much higher labour costs, and

consequently enlarged the credit needs of the peasantry. Over its prices

the cultivator had no control. The dispersed nature of peasant

production meant that the grower had little bargaining power vis-a-vis

the highly organized trading sector.36 A long chain of middlemen-

farias, beparis, aratdars-handled the trade in jute from the village to

the mills and the exporters,37 and a part, a fifth according to the

Director of Agriculture in 1929,38 of the cultivator's due was eaten away

as middlemen's commission. More important, however, was the

cultivator's lack of holding power which compelled him to sell

immediately after harvest when prices were at their lowest. Not only did

34 Beshi pata karo bhai re beshi takar ashe

Jemon asha temon dasha dena pater chashe

Taka taka majur diya niran kulan kam

Marwarira ghare boshe panch taka dey dam

Again

Eto pat dili keno tui chasha

Ebar pater chashe desh dubali, ore buddhinasha

Bujhli na tui burar beta, Abeder katha noyko jhuta

Khete hobe pater gora thik janish mor bhasha

Mone korechho nibo taka,

She asha tor jabe phanka,

Panchiser poya hobe tor, hrine porbi thasha

Nibi bote taka ghare,

Peter daye jabe phure

Hisheb kore dekhish khata, jato kharacher pasha.

Abed Ali Mian, Desh Shanti (Gantipara, Rangpur, 1925)-

35 SDO Kishoreganj to Collector Mymensingh in Report on Marketing of Agricultural

Produce in Bengal 1926, GB (Calcutta, 1928).

36 Amiya Kumar Bagchi, Private Investment in India IgoO~-939 (Cambridge, 1972), pp.

266, 268-9.

37 Royal Commission on Agriculture in India 1926-28 Appendix Vol. I4, p. 70; 'Note on

Marketing of Agricultural Produce' by J. M. Mitra, Registrar of Cooperative Societies

Bengal in Evidence RCA Vol. 4, pp. 137-8; BPBECR Vol. I, pp. 104-5; Bagchi, Private

Investment, pp. 264-5-

38 Evidence of R. S. Finlow and K. Mclean, Director and Asst. Director of

Agriculture Bengal in Evidence RCA Vol. 4, p. I3.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

472 SUGATA BOSE

he not have facilities of storage

peasant required cash at the t

interest payments to the money

Often he would have borrow

trader-moneylender. The Distr

'In case ofjute, cultivators are

growing a certain quantity o

prevailing market rate. The cult

"dadandars" and have to dis

dadandars.'40 In a context o

diminishing holdings the mech

market interacted with and reinforced the credit mechanism to hold

the peasant in their pincer grip and to perpetuate and immiserize at the

same time the small peasant economy of Bengal.

We may conclude our brief portrayal of the agrarian economy and

social structure of Mymensingh by setting out the salient features of the

relationship between the peasantry in debt and the moneylenders. F. D.

Ascoli, the Settlement Officer of Dacca, had on the basis of an economic

survey calculated in 1917 the accumulated debt in the localities in

Dacca adjoining Mymensingh at Rs 2I per head of the whole

population.41 Sachse doubted whether the situation was really as bad,

but acknowledged that 'interest is so high in this country that its

payment constitutes a severe drain on the resources of the agricultural

population, especially as only a small fraction of the total indebtedness

can be considered as capital employed productively'.42 The bulk of the

loans given by the mahajans were short-term ones at high monthly

interest rates. Mahajani-tejarati (moneylending) was usually combined

either with talukdari (rent-collecting rights over land) or with trade. A

great majority of the talukdar-mahajans of Mymensingh were high

caste Hindus while the small traders were mainly drawn from the

intermediate Nabashakh castes-Sahas, Telis, Baniks and others.

Sometimes the three roles could be combined in a single person. This is

not to say that actual control of land and moneylending went hand in

hand. Quite the contrary, the rural credit scene in east Bengal did not

display the type of congruence of large landholding and moneylending

which is so integral a part of the 'semi-feudalism' argument.43 A

9 Bagchi, Private Investment, p. 286.

40 Dt. Agrl. Offcr. Mymensingh to Collr. Mymensingh in Rep. on Marketing of Agrl.

Produce in Bengal 1926.

41 M.S.R., p. 27.

42 Ibid.

43 The classic exposition of the 'semi-feudalism' argument for Bengal is Amit Bhaduri,

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF ' COMMUNAL' VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 473

talukdar usually held rent-collecting rights over small tracts of land

though he often had his own bit of 'khas khamar', and could hardly be

said to exercise actual possessory dominion over the soil. His instrument

of control over the indebted peasant was essentially an economic one

through usury. Though considering age-old village status terms the

talukdar-mahajan would be led to vaunt his position as talukdar, in

economic terms his moneylending function had clearly assumed

crucial importance in the twentieth century and was the source of

what power he had. The unfreedom of the small peasant of east

Bengal weighed down by scarcity of land and usury bore no resem-

blance to that of the dependent sharecropper held down by debt

peonage and extra-economic coercion by the village landlord/rich

farmer-cum-creditor.

The highly unfavourable product market and credit relations in

which the east Bengal peasant was involved did have an impact on the

market in land, but it was not as drastic as upholders of a 'depeasantiza-

tion' thesis have believed.44 The mahajan was not particularly anxious

to sell up his debtors and claim their lands. As Sachse informs us, 'as long

as he [the debtor] can pay the interest he is in no hurry to pay off the

capital, and he has no fear of being sold up'.45 It was an exception rather

than the rule for the creditor to buy up an occupancy holding; when he

did so he resettled it with the previous owner at an increased rent and

occasionally insisted on a produce rent.46 The peasant would under

usual circumstances look upon the mahajan (literally, great man) as a

sort of benevolent father-figure who tided him over the times of need.

There were occasions, however, when the moral economy of the peasant

was outraged. In 1930 the Muslim peasantry of Kishoreganj threw

deference to these 'great men' of the countryside to the winds and

pillaged their homes with astonishing fury.

III. The Disturbances of 1930

The atmosphere in the districts of Bengal in mid-1930 was charged with

the tension of the civil disobedience campaign. In Mymensingh since

'A Study in Agricultural Backwardness under Semi-feudalism', in Economic Journal, 82

(1973), pp. 120-37; see also Rajat and Ratna Ray, 'The Dynamics of Continuity in

Rural Bengal under the British Imperium', in IESHR, X, 2 (I973), pp. II iff.

44The 'depeasantization' thesis is best expounded in Chaudhuri, 'Process of

Depeasantization'.

45 M.S.R., p. 27.

46 M.D.G., p. 69.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

474 SUGATA BOSE

April packets of contraband salt

read in public, schools and colleg

denied to government officers

arrest a more or less successful bo

district.48 Vigorous picketing w

to prevent the issue of country l

in Mymensingh, leading to a ser

Sobhan Sheikh was killed and ano

interior Congress volunteers con

taxes and urged chaukidars an

Local Anjuman associations org

dissuade the Muslim peasantry f

The year 1929 had been bad

severely hit by the depression in

countryside bore the prospect of

area to be harvested in a month's

sure to fall on account of short-

about Rs 5 As 8 could hardl

Administration Report for 1930-

follow:

Distress was worst in the jute growin

prosperity are densely populated, an

holdings of an acre in area or less. T

holdings cannot support them for a

jute which they grow on part of

wherewithal to supplement their foo

market and their jute remaining un

Early in July there were stirrin

47 Clayton Cmsr Dacca Dn to Hopkyn

File 435(1)/30 (WBSA).

48 Hopkyns CS to Burrows DM Mymen

(WBSA).

9 Dutt DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, 1

(WBSA).

5o Burrows DM Mym. to Clayton Cm

51 1/30 (WBSA).

"5 Dutt DM Mym. to Clayton Cmsr Da

DM Mym., 18 June 1930, GB Poll Con

52 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns

(WBSA). Tanika Sarkar is obviously in

failure almost amounting to a famine

First Phase of Civil Disobedience in Ben

(July 1977), PP. 93-4. There was a good

price equivalent of a famine situation.

53 Report on The Land Revenue Administr

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

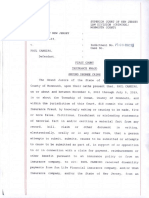

KISHOREGANJ RIOTS (T'o 0"

July 1930

Dhokuric

14t

Surati

?; "h.~ CGangatia

Chfr 0 ~14th

Silashi a

15 th

snthur A14th

15hTntl Char* NO!,a--=

Gafforgoon I i?-?,0 a KISHOREGANJ

a1514'h

, U0 s h 1,e lroibari/

Dhulih

S..a"0

,ro 'th~a -, Bipai

(.PS)Ch

13tlo414th

nkuic .th ,2 -'.. t;

ndtphs ih

Char

a ===::c-- jthAs~hU tI G% at ~

0 (mM)

I an

14 t h:

3th ItI

FC ,[S~ olic Ie ,"Nggf

* 3th itU )a

iL I * . 1. thS4"oKod

,'Chan

rr14th tposc

11 15 j ,osr

oinpuiSchcd

,r19)3th I Kt ml ng ic

ath Kamii" l ," ' ICIlnl rn,

ok n i ,, I'M ij at

n crandi

/ \\ / \ ...,, .. "',,

Olt+ischintapur* th,13th

?0 14th~

(to)Lksh ic umorpur (

Mirz r it 14t Baniagrom

1%12t,13& 12th '

Bahadia ;I

0I 13th It wa

%, Aingodi of=l1

S13th,14th It%

airIN 13th,14th itI

ItI

14 t 911M a pu 11

4?=:';Kticdi

(Thonnj)

*14

Matkholo r~ M - Mar

0 1 2 3 4 ~milts

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

476 SUGATA BOSE

Kishoreganj, Hossainpur and Pakun

meetings of raiyats were held. At one m

which local officers took note of, the N

Kachhari at Hossainpur was condemne

Mohurrum procession the previous mon

tenants, and resolutions were passed aga

moneylenders.54

It was on the afternoon of the I Ith th

began around midday at village Chand

the houses of one Surendra Nath,

newspaper as 'a millionaire of that q

moneylenders were attacked by mobs an

on and carried out similar attacks on

Narandi including that of Ananda Sar

them. On the 12th, Jangalia, Mirzapu

pur were attacked as well as Chandipa

lay sufficiently far apart (see map) to ind

gangs were operating and that the moti

were more or less general.56

It was at Jangalia that the most gr

Krishna Chandra Roy, talukdar, preside

moneylender on a large scale and hold

bargadars, had received news of the loo

afternoon and had engaged two buses

valuable possessions. The rioters arrived

could get away, destroyed the buses and

Krishna Roy put up a stout defence fro

upon the rioters with two guns. Two

wounded when the ammunition ran out

and the nine male members of the fa

were also wounded defending their husb

to her injuries. The other women num

harmed, but all the buildings were com

smashed that was not carried away. The

the village, all belonging to Hindu mone

looted and burnt, while the others were

54 Ibid.; Amrita Bazar Patrika (hereafter referre

55 AI P, I6July 1930.

56 Teleg. from Secy Mukhtears Bar Kishorega

Mym. to Clayton Cmsr Dac. Dn, 13 July i930; B

July 1930; GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA); A

"' Teleg. from Secy Mukhtears Bar Kish. to GB

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF CCOMMUNAL9 VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 477

The same day a mob of about 300 rioters armed with sharp weapons

was dispersed outside Baniagram in Katiadi thana by Surendra

Chaudhuri, a local talukdar, who opened fire."58 This action prevented

any further attack in those parts. But in Pakundia thana the trouble

spread farther on the i3th to villages Lakshmia, Baratia, Kodalia,

Jaitra, Bahadia, Egara Sindur, Aingadi as well as to Mirzapur and

Narandi again. The primary objective of the looters was to get hold of

bonds or other documents in the custody of the moneylenders and burn

them or tear them to pieces.59 In the market centres of Kaliachhapra

and Pulerghat the big shops of Ram Chandra Saha,Jagat Nananda and

Gnan Majumdar were pillaged.60 Refugees from the villages poured

into Kishoreganj town. There were panicky rumours of plans of an

attack on the town itself, which however did not materialize.61

On the I4th in Pakundia thana, Matkhola, Jamalpur, Nischintapur,

Aingadi and Egara Sindur were attacked. Matkhola was a big business

centre and counted among its inhabitants 50 mahajans. Many refugees

had also taken shelter in the Matkhola Kali temple. At noon on I 4July a

thousand-strong mob armed with lathis, swords, ramdaos, and halongas

attacked the bazaar attached to the Kalibari. A small police force had to

retreat in the face of the onslaught but reinforcements arrived just in

time and in the police firing four rioters were killed. The big tin sheds of

all but three of the mahajans of Matkhola were in this way saved from

destruction.62

Clayton Cmsr Dac. Dn, 13 July I930; Teleg. from DM Mym. to GB, 14 July 1930;

Report about the looting and rioting in Kish. Sdn by SDO Kish. dtd 12 July 1930;

Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I8July I930; GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA);

ABP, 15, 16 and 3oJuly 1930; Lakshmikanta Kirtaniya, Loter Gan (Songs Commemorat-

ing The Loot, Matkhola, Mymensingh 1930).

58 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, 28 July 1930; GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA); ABP, 3oJuly 1930.

59 Teleg. from ADM Mym. to GB, 13July 1930; Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS,

I8 July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA); ABP, 16 July 1930.

60 ABP, I6July 1930.

61 Ghatak ADM Mym. to Clayton Cmsr Dac. Dn, 13 July 1930; Rep. about the

looting and rioting in Kish. Sdn by SDO Kish. dtd 13 July I930; Teleg. from ADM

Mym. to GB, 14 July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

62 Rep. about the looting and rioting in Kish. Sdn by SDO Kish dtd 14 July 1930;

Inspr Kish. to ASP II Mym., I4July i93o; Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I8July

193o, GB Poll Con File 6I3/30 (WBSA); ABP, 30 July 193o; Lakshmikanta Kirtaniya,

Loter Gan.

The Matkhola Kali temple provides an interesting example of the syncretist tradition

in rural Bengal. Muslims would vow to sacrifice goats or sheep before the deity for the

fulfilment of their wishes and at the time of Durga or Kali Puja a number of goats or

sheep would be brought by Muslims to be sacrificed. The only difference between the

Hindu and Muslim offerings was that whereas the Hindus would take away the carcass

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

478 SUGATA BOSE

In Hossainpur thana, the first attac

Sahedal, Barsikura, Dhankuria, Dhulj

bances spread northwards on the 14th t

Char, Char Katihari, Madhakhola, Sur

There were also stray attacks in a few

such as Patabika, Kamaliapara, Binna

On 15 July the contagion spread acros

the Gaffargaon region. The looting b

Hindu moneylenders of village Sakch

through a number of villages. The rio

cally visited the houses of all the mone

demanded the surrender of all documen

ment had given Swaraj to them for the

led to nothing further than the burnin

produced an attack upon the house a

smashed open and anything in the

destroyed. A police party caught up wit

the act in the house of Ram Sarkar of S

checked the further spread of the riots

One interesting feature of the riots wa

under the impression that the gover

Similar notions, real or imagined, of su

against immediate oppressors have of co

peasant rebellion in other regions and

maulavies from Dacca and Bhowal

cultivators that the government suppor

interfere if they demanded back their b

moneylenders and extorted them forcib

leaving only the head for the Goddess, the Mus

they would not touch the meat of any animal

orthodox way by cutting open the windpipe. Th

with one stroke of the sabre and failure to do

Matkhola temple was not touched during the 19

it was looted and partly burnt. But it was demoli

troops during the Bangladesh war of 1971 and t

the Ganges at Benares.

I am indebted for this information to Mr Charu

had established the Matkhola Kali temple.

63 Teleg. from DM Mym. to GB, I6 July 1930

July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA); A

64 Teleg. from ADM Mym. to GB, i6 July I

Bengal, I6 July 1930; Rep. on the Police Firin

South; Rep. on Disturbances at Gaffargaon in

GB Poll Con File 6I3/30 (WBSA); ABP, 17 Jul

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 479

instances of such beliefs appear in the documents.65 When the Circle

Officer of Kishoreganj confronted the looters atJaitra in Pakundia elaka

on 12 July he was asked why he had come to interfere when the

authorities had done nothing of the kind in Dacca. On 15 July, Burrows,

the District Magistrate, had a conversation with Ali Sheikh, a resident of

Kuriman in Hossainpur thana, who on being asked why his village was

practically empty replied that the villagers had all gone south to

demand back their deeds from mahajans. He added that everybody said

that this was the government order promulgated about ten days

previously. Finally, a rioter wounded in police firing at Ashutia on 14

July cried out before he died 'Ami British governmenter proja, dohai

British government' and could not evidently understand why he had

been shot by government forces.66

With the District Magistrate having left on tour on the day of the

outbreak, local officers with the forces at their disposal were at a loss to

deal with the situation on the first couple of days of the disturbances.

The usual modus operandi was for a mob of anything between Ioo and

I oo1000 men to demand back from a moneylender all the documents in his

possession. Temporary immunity could be purchased, but if the

documents were not produced at the time fixed his house was looted and

in some cases burnt. The looting usually took place during daytime

evidently because it was considered cowardly according to the Shariat

to go out plundering at night. On the 12th and 13th police patrols had to

flee from belligerent mobs.67 Reinforcements were rushed from head-

quarters and on the 13th night a contingent of 50 Easter Frontier Rifles

arrived from Dacca. The District Magistrate reached the troubled area

on the following day and stern action was taken in the Pakundia and

Hossainpur thanas, the worst affected areas, with the police firing on

excited mobs at Gobindapur, Ashutia, Patuabhanga, Nischintapur,

Aingadi, Tengar and Matkhola causing a number of casualties. By the

65 Teleg. from DM Mym. to GB, 16July 1930; Rep. about the looting and rioting in

Kish. Sdn by SDO Kish. dtd. I4July 193o; Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, i8July

1930, GB Poll Con File 6I3/30 (WBSA).

66 In the I906-07 riots in Mymensingh also the rioters had believed that the

government had authorized the pillage of Hindu mahajans, cf. M.S.R., p. 30; very

similar notions appear to have been held by peasant rebels during the Deccan riots of

1875, cf. Catanach, 'Agrarian Disturbances', pp. 70-2, and in the grain riots in Madras

in 1918, cf. David Arnold, 'Looting, Grain Riots and Government Policy in South India

1918', in Past and Present, 84, (1979), p. 145; analogies can also be drawn in this respect

with peasant behaviour in rural riots in eighteenth-century France and Russia. See, for

instance, George Rude, The Crowd in History (New York, 1964), p. 28.

67 Ghatak ADM Mym. to Clayton Cmsr Dac. Dn, 13 July I930; Teleg. from ADM

Mym. to GB, 14 July 1930, GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

480 SUGATA BOSE

i6th the worst was definitely over,

alarms in Gaffargaon, Katiadi, Nikli

of firings on the I4th seemed to have b

the situation. A short spell of fair wea

government forces by motor transpo

having erupted near Pakundia on I I Ju

the following days, were quickly repre

Magistrate was able to write with sm

and the Eastern Frontier Rifles force have been as invaluable as usual.

Johnny Gurkha commands the greatest respect in mofassil Bengal as a

fighting man and the mere fact that he is present is a valuable asset to

district authorities in troubled times.'70

The balance-sheet of casualties showed:

Killed Wounded

I. Those attacked by rioters 11 I

(incl. I woman and

lo in one family)

2. Rioters 1 15

(2 by persons (8 by persons

attacked, rest in attacked, rest in

police firing) police firing)

3. Government servants 5

22 21

Personal viole

Krishna Ray

Namusudra B

was no molestation of women. The wrath of the rioters was directed

against property in general, and loan bonds in particular. By the end of

the month it was ascertained that 90 villages had been attacked.72 On

68 Teleg. from DM Mym. to GB, I4 July 1930; Teleg from DM Mym. to GB, i6July

1930; Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I8 July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

69 Clayton Cmsr Dac, Dn to Hopkyns CS, 31 July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

70 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I8 July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

71 Teleg. from DM Mym. to GB, i6July I930; Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS,

18 July 1930; GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA); ABP, 30 July 1930.

72 Mackenzie SP Mym. to Burrows DM Mym., 2 August I930, GB Poll Con File

613/30 (WBSA).

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 481

30 August with police investigations complete, 142 cases were instituted,

one case being brought for all looting cases occurring in the same village

on the same day and committed by the same gang. Charge sheets were

actually submitted in 129 cases against 631 people, only the 'principal

culprits' having been selected for being charge-sheeted.73

Not surprisingly, considerable controversy raged even at the time

over the responsibility for these extensive riots as well as their true

nature. Had the 'disobedience' fostered by the Congress recoiled on

them? How far were the disturbances an outcome of the design of the

colonial state to divide Hindu and Muslim? What mischievous roles did

the itinerant maulavies play? Had Kishoreganj witnessed a 'class war' or

a 'communal outbreak'?

'Too much violence and intimidation by Congress volunteers seems

have been allowed in Kishoreganj,' angrily wrote Clayton, Comm

sioner of Dacca Division, which in his view had 'done much to

undermine the respect for the authority of Government'.74 There seems

to be, however, little causal link between the disaffection spread by the

Congress party and the outbreak in Kishoreganj. There is considerable

evidence on the other hand that it was an innocently held belief that the

forces of law and order would under the circumstances support

lawlessness and disorder if directed against the Hindus that emboldened

the Muslim cultivators to revolt. Local officers acknowledged that the

mobs were encouraged by 'misleading rumours' spread by maulavies of

what had occurred in the Dacca district.75 Dacca along with Comilla

and Chittagong had been a major centre of civil disobedience in east

Bengal. In the last week of May 1930 a bitter communal riot broke out in

Dacca town and its outskirts. A large body of evidence furnished before

an official Dacca Riots Enquiry Committee suggests that professional

goondas, many of whom it was alleged by Hindu victims lived and

practised sword-play in the Nawab ofDacca's bagicha, attacked Hindus

and looted Hindu shops while the police under British officers turned a

blind eye.76 The police moreover took the opportunity of the communal

clashes to raid Hindu houses and generally spread terror among the

73 Special Report Case No. 93/30 Report III by Khaleque ASP Mym., 30 August

193o, GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

74 Clayton Cmsr Dac. Dn to Hopkyns CS, 31 July 1930, GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

75 Ibid.

76 GB Poll Con File 444/30 (WBSA). Apart from the testimony of the victims, there is

a mass of evidence furnished by eye-witnesses, e.g., the evidence of Miss R. B. Verulkar,

Principal, Eden High School and College for Girls, Dacca, and of Miss P. Haldar,

Headmistress in charge of Vernacular Training Schools.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

482 SUGATA BOSE

nationalist ranks." Disturbances also o

district outside the town and the enquir

villages, Matwail, Jinjira, Ati and Roh

had a grievance against their Hindu m

events in Dacca encouraged them to g

that messengers went out from Dacca on

villagers that the Nawab had ordered th

and that the 'paramount power' would

that on the 27th, 500 to 700 Muslims

villages surrounded Rohitpur hat and

prominent Sahas.79 After the inciden

accompanied by the Nawab of Dacca v

to the victims that the looting by the M

the civil disobedience campaign.s0 Th

from the Dacca side carried to the Mu

were not entirely lacking a basis in fact

Was government policy in Mymens

District Magistrate G. S. Dutt's colleague

the Divisional Commissioner, became

viewed as his weak-kneed and over

Congress movement, and in the first we

Burrows.8s Dutt had in a letter of 2 Jun

communal trouble between bands of vol

and local Muslims.82 On I July Bu

apprehensions on that score were 'entire

" The official enquiry committee report, me

acknowledged that raids were carried out on H

curious justification of the apparent partialit

opinion having recognized 'the insufficiency

Muhammadan mobs, who were far more numer

Hindu mobs', the police did their duty by taking

an end to the chance of any further provocation f

Committee Report 193o (hereafter referred to as

78 Ibid., p. I9. 79 Ibid., pp. 19, 25-

80 Ibid., p. 38. The report maintained, however, that local officials did nothing wrong

in striking an alliance with the Nawab of Dacca.

81 Craig DIG Dac. Range asked Lowman IGP whether there was any hope of Dutt

being replaced, GB Poll Con File 51i1/30; Clayton complained that the police would

have done a better job if Dutt had given proper support and considered that 'a better

selection might have been made for Mymensingh', Clayton Cmsr Dac. Dn to Hopkyns

CS, 25 May 193o, GB Poll Con File 435/30 (WBSA).

82 Dutt DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, 2 June 1930; Hopkyns CS to Burrows DM Mym.,

18 June I930, GB Poll Con File 5 I1 /30 (WBSA).

83 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I July 1930, GB Poll Con File 511/30

(WBSA).

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 483

upon his arrival in Mymensingh two false rumours were circulated. The

first was that he was against the Hindus generally and the second that he

had been sent by Government in Dutt's place to create communal

trouble. He addressed two meetings in the Pleaders' Bar Library and the

Mukhtears' Bar Library to contradict these rumours. Regarding the

enrolment of volunteers by Anjumans he had to say that they had as

much right to enrol volunteers as the Congress. He had been informed

by Anjuman leaders that they were quite willing to accept Hindus as

volunteers who were against the civil disobedience movement in the

same way as Congress were enrolling Muslims who were in favour of the

movement. The issue, he put it, was not between Muslims and Hindus

but those against and in favour of the civil disobedience movement.

Burrows clearly recognized that the civil disobedience movement could

be contained if the Muslim peasantry at large did not join in it. He set

out his policy to Calcutta thus: 'So far the Muhammadans have kept

themselves aloof mainly in their own interests and my policy will be to

maintain this attitude without giving any encouragement to communal

aggression.'84 He urged the Chief Secretary to bring some influence to

bear upon Maulavi Abdul Hakin, M.L.C., a leading Muslim supporter

of civil disobedience in Mymensingh, at the next session of the Council.

'For the rest,' he wrote, 'I propose to be quite firm with all the actions of

the Congress party and have already taken action accordingly in one or

two cases .... The jail is very full at the moment.'85 Both Hindus and

Muslims were left to draw their own conclusions. Widespread and

uncontrolled violence was, however, a dangerous thing for government

to encourage and, as we have seen, the Kishoreganj disturbances were

put down with a firm hand after they had broken out. Once order had

been restored the argument which clinched the issue against the

imposition of punitive police was that it was something the nationalists

'might utilise to persuade the Mahommedans from their present

opposition to the Civil Disobedience Movement'.86

The nationalist press asserted that the Kishoreganj riots had been

planned by masterminds who had their own axes to grind.87 The

urban-based Muslim politicians fighting with the Hindus for jobs and

council seats and their religious agents had indeed made a vested interest

of the poverty and misery of the Muslim peasantry which they used to

further their own ends. The Charu Mihir of Mymensingh complained

84 Ibid. 85 Ibid.

86 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I8 July I930, GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

87 ABP, i August 193o; Liberty, 25 July I930.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

484 SUGATA BOSE

that the maulavies went about telling t

in the jute market was due to the p

Congress. Yet, the foreign rulers as we

'natural leaders' of the Muslim commun

existing contradictions in Bengali rur

maulavies assuring the Muslim peasantr

lent neutrality was but a spark which s

east Bengal countryside alight. What

inherent in agrarian society that lay at

1930?

The Kishoreganj disturbances were, acccording to the District

Magistrate of Mymensingh, 'primarily economic with a necessary

communal tinge because more than 90 per cent of the tenants and

debtors in the affected area are Muhammadans, while the large

majority of the moneylenders are Hindus. Muhammadan moneylenders

have, however, been proportionately threatened and looted.'89 This

view was reiterated by the Governor of Bengal in reply to a deputation of

M.L.C.s who called on him.90 A substantial section of the Hindus

asserted, however, that the uprising was 'not in fact a class war'91 or

simply a debtor's revolt and claimed that only Hindus and no Muslims

had been attacked and that many persons without any connection to the

moneylending business were victims of the rioters.92 The District

Magistrate was able to supply names of nine Muslim moneylenders who

had lost their documents and said that he had received requests for help

from several more. He cited the actual figures from the first information

reports which showed that only a small proportion of the victims were

not connected with the moneylending business. According to these

figures, 995 Hindu houses and shops and 6 Muslim houses were looted

with documents, 33 Hindu shops were looted in which no demand for

documents was made and 21 Hindu and 3 Muslim houses lost

88 For instance, the government-appointed committee explained the origin of the

Dacca riots in this way: the Hindus to further the civil disobedience campaign had

attempted 'to divide the Muhammadans and thus weaken the influence of their natural

leaders'; when the several associations of the Muhammadans succeeded in coming

together again and felt themselves under one leader, the Nawab of Dacca, 'they were

naturally elated and anxious to take the first opportunity of showing the Congress party

that their intrigues had failed', DRECR 1930, p. 25-

89 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns CS, I8 July 1930, GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

90 ABP, 17 July 1930.

91 Statement by Nalini Ranjan Sarkar, ABP, I August 1930.

92 Ibid.; Statement by B. P. Hindu Sabha, Advance, 2 August 1930 and ABP 24 July

1930; Memorial to H. E. the Governor of Bengal from the Hindu population of Kish.,

GB Poll Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNAL' VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 485

documents under threat without any looting.93 While these statistics

speak eloquently of the nature of agrarian conflict in rural east Bengal,

the District Magistrate appears to have been a little anxious to discount

the role of communalism. Reports from some of his subordinate officers

indicate that looting, once it began, gathered its own momentum and

the rioters were not always discriminating in their purpose. The S.D.O.

Kishoreganj, for instance, wrote, 'All the Namasudra houses at Jaitra

had been looted and damaged.'94 In Bahadia the looters were said to

have 'entered about 70 Hindu houses including many huts of poor

people through which the looters marched committing some mis-

chief'.95 In the market centres of Pulerghat and Kaliachhapra the

Superintendent of Police found that 'loot was the object and since only

Hindu shops were looted, Muhammadan shops being exempted, a

certain amount of communal bias was evident'.96 There is little doubt,

however, that the principal target of the rioters was the moneylender

who in most cases in east Bengal was Hindu.

One prominent Hindu leader refused to believe that the riots were

fundamentally economic and argued that the actual pinch of scarcity

caused by low prices could not have been felt when the disturbances took

place as the bulk of the jute crop still stood on the fields. The destructive

acts of the rioters, he said, made it clear that they were not actuated by

the necessity of finding food.97 The fact that the looters often chose to

destroy paddy rather than steal it can hardly be said to indicate that

there was no genuine economic discontent behind the disturbances.98

The cultivators already hard hit by the low prices obtained forjute and

paddy in the previous year, knew that they would be called upon to

make payments on their bonds as soon as the aus paddy and jute crop

had been reaped. It was clearly their desire to avoid these exactions

which led them to seize and destroy loan bonds. The slump was striking

93 Burrows DM Mym. to Press Officer GB 5 August I930; GB Poll Con File 613/30

(WBSA).

94 Rep. about the looting and rioting in Kish. Sdn by SDO Kish. dtd 12July 1930, GB

Poll Con File 6I3/30 (WBSA).

" Special Report Case No. 93/30 Report III by Khaleque ASP Mym., 30 August

I93o, GB Pol Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

96 Notes on Kishoreganj Investigations by Mackenzie SP Mym., 24 Aug. 1930, GB

Pol Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

9' Statement by Nalini Ranjan Sarkar, ABP I August 1930.

98 During food riots in eighteenth-century England, it was not unusual for starving

people to scatter grain along roads and hedges or to dump it in the river. Their main

purpose was to punish proprietors for violating their notions of justice, cf. E. P.

Thompson, 'The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century', in

Past and Present, 50 (February 1971), PP. 14-i5.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

486 SUGATA BOSE

at the roots of the old paternalist mo

interest met with a refusal by the mah

'actual pinch' was in fact soon to come.

reporting sporadic cases of looting of p

the end of the year the Government

80 ooo to Mymensingh to relieve acute

Let us now have a look at the mahajan w

chief class enemy of the peasant in the

the ill-fated Krishna Chandra Roy ofJ

example of the nature of the financ

talukdar-mahajan. In 1917 at the time

record-of-rights of his locality, Krishna

Shyama Charan held 5.19 acres as a pe

rent in four different khatiyans, 10.05 a

raiyat of the village, and 1.21 acres in tw

rent) raiyat.102 Some of his lands held

raiyats and those that he held in his

cultivated by bargadars and farm lab

records of the district registration offi

1930 twenty-four mortgage deeds were

Roys' favour by Muslim and Namasu

mostly short-term loans for periods betw

at usurious rates of interest of up to

mortgaged in all cases was to remain in t

If he could not repay the principal with

the condition was that he would cont

defaulted in the payment of interest, th

sell up the land, and if that did not cove

interest, he would be empowered to rea

debtor's moveable and immoveable pr

99 The problem of loan refusals was to become m

reported from Noakhali in May 1931 that 'the u

give loans may give rise to riots like tho

threats.... the Mahommedans had boycotted H

that unless they gave loans freely neither their l

Cmser, Chittagong Dn to CS, 28 May 1931, G

100 Teleg. from DM Mym. to GB, 23 Sep. 193

September I930; Burrows DM Mym. to Secy Rev

Con File 613/30 (WBSA).

101 GB Poll Con File 35/31 (WBSA).

102 Record of Rights of Mouza Jangalia, D

Collectorate Record Room).

103 Deeds of Land Sales and Mortgage,

Registration Office).

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 487

distraint, and to all this, the deeds declared in grandiose legal Bengali,

neither the executant nor his descendants would have the right to make

any objection. The extent of the Roys' moneylending business in

Jangalia and its environs which did not involve registration and security

of land we can only imagine. However, in the 1920O the talukdar-mah-

jan did not go on a spree of buying up raiyati holdings. We find that

between 1918 and 1930 while Krishna Chandra and his brother spent

Rs I I I 17 in ten different purchases of shares in Shikmi taluks, they

dispossessed only five Muslim cultivators of whole or part of their raiyati

holdings.x'4 On 23/2/22 they bought 0.96 acres from Sk. Alimuddin et

al. for Rs 400; on 26/6/22 o.o8 acres from Sk. Himmat Akan for Rs 32; on

10/2/25 2.65 acres from Sk. Amjad et al. on a court decree; on 19/5/30

0.37 acres for Rs 200 from Sk. Yasin of Dagdaga who we find ten years

ago had borrowed Rs Ioo at 4 per cent monthly interest by mortgaging

nearly 3 acres of land; and finally, less than a month before the family

was exterminated, 0.45 acres from Sk. Himmat Baksh for Rs 385. The

reason cited for each of the above sales was indebtedness or simply

urgent need of cash. With the onset of the depression the mahajans were

to face increasing difficulty in recovering their money and were left with

little alternative other than foreclosing mortgages to get back at least a

part of their outlay. Unsecured loans were largely to be lost.

The anti-moneylender character of the Kishoreganj disturbances

need not be further emphasized. Yet, it is at the deeper and more subtle

level of human motives that the problem of class conflict versus

communalism has still to be resolved. In a good number of peasant

studies the role of immediate economic interest in actuating peasant

action has been stressed and religious and other ideology seen as

'legitimizing' more practical grievances.105 However, the satisfaction of

an irrational and perhaps subconscious passion can conceivably be a

stronger human motive than the satisfaction of a material interest. Is it

possible, if a sequential pattern can at all be discerned, that psychologi-

cal alienation precedes the comprehension of a rational material

grievance?. For a disaffected intelligentsia, as in the case of the early

Indian nationalists, it is arguable that disaffection caused by more

subjective affronts leads on to the building of an intellectually presen-

table case of economic exploitation. For a peasantry the same probably

does not hold true for the economic grievance in this case is often hunger.

104 Ibid.

105 The voting behaviour of the Punjab peasantry on the eve of partition has, for

instance, been recently explained in these terms, cf. I. A. Talbot, 'The I946 Punjab

Elections', Modern Asian Studies, 14, I (February 1980), p. 90 and passim.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

488 SUGATA BOSE

Nevertheless we must take account of

Zamindari referred to in a memorial

'dream of mastering it over the Hindus'1

rising in Kishoreganj. This 'dream' is

though possibly powerful motive as

helping to legitimize the Muslim pe

demands and protests.

Since the later nineteenth century an

the Muslims of Bengal became noti

expression in such acts as the adoptio

highhandedness of Hindu zamindars a

hitherto been meekly accepted beg

movement in Mymensingh had its origi

twentieth century in protests against th

a seat in the kachhari and the use of t

polite 'apni' in addressing Muslim elders

naibs.107 Nirad C. Chaudhuri writing

recalls the Hindu bhadralok's 'mixed c

Muslim peasant, whom we saw in the sa

Hindu tenants, or, in other words, as

explains how mental attitudes were form

Nothing was more natural for us to feel abo

Even before we could read we had been told that the Muslims had once ruled

and oppressed us, that they had spread their religion in India with the Koran in

one hand and the sword in the other, that the Muslim rulers had abducted our

women, destroyed our temples, polluted our sacred places. As we grew older we

read about the wars of the Rajputs, the Marathas and the Sikhs against the

Muslims ... .109

A Muslim boy growing up in early twentieth-century Mymensingh was

bred in a tradition the polar opposite to that of the Hindu. Abul Mansur

Ahmad, who became an important Proja leader of Mymensingh, fecalls

in his memoirs an inspiring Bengali ballad about going to Lahore to

'06 Satish Chandra Roy Chaudhuri MLC Manager of Atharabari Zamindari to

Hopkyns CS, 17 July I930, GB Poll Con File 6I3/30 (WBSA).

107 Abul Mansur Ahmad, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Panchas Bachhar (Dacca, 1968), pp. 5-6,

12-13.

108 Nirad C. Chaudhuri, An Autobiography of An Unknown Indian (London, I95i),

p. 230. The author described four distinct aspects in the Hindu bhadralok's attitude to

Muslims: retrospective hostility for their one-time domination, utter indifference on the

plane of thought to Muslims as an element in contemporary society, friendliness for the

Muslims of their own economic and social status and mixed concern and contempt for

the Muslim peasant.

109 Ibid.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNAL' VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 489

fight in ajehad against the Sikhs which used to be his favourite as a little

boy. 'Chachaji, where is Lahore? what are Sikhs?' he asked. 'Lahore is a

distant place in the west of Hindusthan. And Sikhs? They are wicked

enemies of Allah' replied Chachaji. 'As wicked as the Hindus?' was the

inquisitive little boy's next question. 110 These were of course attitudes to

historical and somewhat unreal labels 'Hindu' and 'Muslim' and did not

quite correspond to attitudes to Hindus and Muslims in flesh and blood

who were each other's neighbours. The Swadeshi movement has been

seen as a crucial turning-point which brought Hindu-Muslim

antagonism down from the historical to the contemporary plane. 111 It is

quite plausible as well that the notion of a temporary withdrawal of

the repressive role of the colonial state in regard to communal violence

leading to the Mymensingh and Comilla riots in 19o6-o7 marked for the

first time a brief release of the Muslims of east Bengal from their old fear

of the Hindus.112 Yet, if a 'dream' of getting even with the Hindus as a

community did percolate down to the Muslim peasantry of east Bengal,

it is our view that the limiting factor of the structure of the local political

and moral economy had so long ensured that it would remain an idle

dream.

IV. Conclusion

So long as the Muslim peasant of east Bengal remained invol

kind of symbiotic economic relationship with the Hindu talukd

mahajan, the possibility of a sustained conflict could be ruled o

historical significance of the Kishoreganj riots of 1930 lies in the

it dramatically announced the collapse of that relationsh

momentous impact that the slump was going to have on the sys

agrarian relations could hardly have been recognized at the tim

had on earlier occasions been strains on the system when in bad

peasants protested against what they regarded as unjust dem

their resources; but the crisis would soon be resolved and th

revert to its old way of functioning. The magnitude and the ex

nature of the economic crisis of the 1930s were unprecedented:

ties snapped. The guardians of the law were pleased to have been

110 Ahmad, Amar Dekha Rajnitir Panchas Bachhar, pp. I, 4-5-

111 Chaudhuri, Autobiography, p. 232.

112 The peasants of Dewanganj who were deeply in debt took advantage of

that the government had authorized the pillage of Hindus to loot bazaars an

Hindu mahajans, M.S.R., p. 30.

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

490 SUGATA BOSE

put down the 'dangerous disturb

few casualties;113 they had onl

climax was to be reached in I94

witness to this day.

In the years following 1930 Kish

combinations to put pressure o

cases of incendiarism by debtors

experience of Kishoreganj and the

non-payment of debts in east Be

and Mymensingh prompted the

tion in the form of the Bengal A

setting up of debt settlement b

ailing system of rural credit r

Kindersley, District Magistrate

Indebtedness Department of th

Enquiries seem to show that through

willing and also less able to lend mon

of the depression of 1930-31 than pr

of the Agricultural Debtors' Act has

willingness to lend.

He added that 'far from encou

before the depression, mahajans

who can give security which ca

ornaments or other similar mo

Bengal Moneylenders Act of 1940

the amount of the principal recov

the coffin. Agrarian Bengal emer

period of war and famine. The o

Ironically, the 1930S which b

Bengal peasant also witnessed a

power in the countryside in his f

of rural credit relations, the slum

mahajan the major source of hi

deference to the mahajan also va

of guarantor of the peasant's s

113 Burrows DM Mym. to Hopkyns

(WBSA).

114 Fortnightly Reports on the Polit

January 1932, first half of March 193

July 1935-

115 Kindersley DM Mym. to Jt. Secy CCRI Dept., 27 November 1937, GB Rev. B

May 1940 Progs 14-57 (BSRR).

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ROOTS OF 'COMMUNALI VIOLENCE IN RURAL BENGAL 491

production and reproduction of the small peasant economy of east

Bengal he had ceased to perform his function. The irrational strength of

Muslim identity ensured that the conflict in rural Bengal was channelled

into the movement for Pakistan and not into the broad stream of the

national struggle. To the vast mass of smallholding peasants living

under similar yet very splintered conditions of economic existence in east

Bengal, religion seemed to impart a sense of 'community'; at a crucial

juncture in Bengal's history it was claimed as well to provide the basis of

a form of 'national bond', however narrow, and became the rallying cry

of a 'political organization'. 116 The appeal of a small enlightened Hindu

intelligentsia and their nationalist Muslim comrades to the Muslim

peasantry in the name of progressive nationalism and socialism went

unheeded; it was to the call of Islamic unity that they responded to give

in their own minds a powerful ideological legitimation to their rejection

of the old economic, political and moral order.

Underlying all the religious fanaticism of the immediate pre-indepen-

dence years there remains a largely economically determined fact. From

1930 onwards the Hindu talukdars and traders of east Bengal were not

merely hated, but were increasingly seen to be utterly redundant. In

1947 they were forced to pack their bags and begin their trek towards the

newly demarcated Indian border.

116 The phrases in quotes are those of Marx in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis

Bonaparte, K. Marx and P. Engels, Selected Works, Vol. i (Moscow, i962), p. 334-

This content downloaded from

59.152.97.82 on Thu, 28 Mar 2024 15:03:12 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Conversion To Christianity Among The NagasDocument44 pagesConversion To Christianity Among The NagasRaiot Webzine100% (4)

- Communal Violence in Twentieth Century Colonial Bengal - An Analytical Framework by Suranjan DasDocument18 pagesCommunal Violence in Twentieth Century Colonial Bengal - An Analytical Framework by Suranjan DasSumon ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Writ of ProhibitionDocument5 pagesWrit of Prohibitionapi-231555366No ratings yet

- Prisoners of Zenda - Summary of Novel (Chapters)Document15 pagesPrisoners of Zenda - Summary of Novel (Chapters)Amirul Ashraff91% (46)

- Usa Leads 5 MillionDocument113 pagesUsa Leads 5 Millionraymond arabe100% (1)

- The Roots of Communal ViolenceDocument30 pagesThe Roots of Communal Violenceomniscient.0001No ratings yet

- Peasant and Tribal MovementsDocument17 pagesPeasant and Tribal MovementsNeha GautamNo ratings yet

- Archer JournalRoyalAsiatic 1984Document4 pagesArcher JournalRoyalAsiatic 1984Sadhish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Peasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990Document6 pagesPeasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990RajnishNo ratings yet

- Science Society and Agriculture in BengalDocument18 pagesScience Society and Agriculture in BengalritaNo ratings yet

- Bhadralok Communalism in Bengal 1932 194Document16 pagesBhadralok Communalism in Bengal 1932 194maham sanayaNo ratings yet

- Taj Ul-Islam Hashmi - Pakistan As A Peasant Utopia - The Communalization of Class Politics in East Bengal, 1920-1947-Routledge (2019) (Z-Lib - Io)Document328 pagesTaj Ul-Islam Hashmi - Pakistan As A Peasant Utopia - The Communalization of Class Politics in East Bengal, 1920-1947-Routledge (2019) (Z-Lib - Io)Jahid HossainNo ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 4Document22 pages08 - Chapter 4Rakesh SarkarNo ratings yet

- Dasgupta TituMeersRebellion 1983Document11 pagesDasgupta TituMeersRebellion 1983ohidul.hossainNo ratings yet