Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Importance of Competency Model Development

The Importance of Competency Model Development

Uploaded by

prasetyokolik-1Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Econ1 Syllabus Spring2016Document3 pagesEcon1 Syllabus Spring2016Josue Lopez0% (1)

- 4.10. The Data in Table 4.4 Are To Be Fit To An Eq...Document1 page4.10. The Data in Table 4.4 Are To Be Fit To An Eq...Ahmad AbdNo ratings yet

- WhitePaper - Universal Competency FrameworkDocument11 pagesWhitePaper - Universal Competency FrameworkTristia100% (1)

- Salvatierra Et Al. 2016 - Chilean Construction Industry - Workers Competencies To Sustain Lean ImplementationsDocument10 pagesSalvatierra Et Al. 2016 - Chilean Construction Industry - Workers Competencies To Sustain Lean ImplementationsAndrews Alexander Erazo RondinelNo ratings yet

- JETIRA006052Document7 pagesJETIRA006052Bhavleen KaurNo ratings yet

- 575 6154 1 PBDocument14 pages575 6154 1 PBHabtamu GedefawNo ratings yet

- 10 - 12 - HR PolyclinicDocument22 pages10 - 12 - HR PolyclinicPratiksha MaturkarNo ratings yet

- Performance Improve Qtrly - 2020 - Giacumo - Trends and Implications of Models Frameworks and Approaches Used byDocument40 pagesPerformance Improve Qtrly - 2020 - Giacumo - Trends and Implications of Models Frameworks and Approaches Used bywangshiyao290No ratings yet

- Comptency ModelsDocument24 pagesComptency ModelsEx SolNo ratings yet

- White Paper SHL Universal Competency Framework PDFDocument11 pagesWhite Paper SHL Universal Competency Framework PDFbedraabNo ratings yet

- Admsci 08 00018 v2 PDFDocument15 pagesAdmsci 08 00018 v2 PDFconteeNo ratings yet

- Developing Entrepreneurial Competencies in Higher Education A Structural Model ApproachDocument24 pagesDeveloping Entrepreneurial Competencies in Higher Education A Structural Model ApproachwiricardopNo ratings yet

- Softs SkillsDocument13 pagesSofts SkillsAs Su MaNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2101405Document15 pagesIJCRT2101405shrimisahaNo ratings yet

- Competency ModelsDocument11 pagesCompetency ModelsLovepreetSidhuNo ratings yet

- Research Report On EmployabilityDocument17 pagesResearch Report On EmployabilityFizza KhanNo ratings yet

- Competency Mgm. A Debate. 2009Document9 pagesCompetency Mgm. A Debate. 2009axon45No ratings yet

- A Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110Document44 pagesA Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110steven ngknNo ratings yet

- Competency Based Management: A Review of Systems and ApproachesDocument14 pagesCompetency Based Management: A Review of Systems and ApproachesAlexandru Ionuţ PohonţuNo ratings yet

- Talent Management As A Method of Development of The Human Capital of The CompanyDocument8 pagesTalent Management As A Method of Development of The Human Capital of The Company74081298No ratings yet

- Full Project Sumit Ninawe 2022Document53 pagesFull Project Sumit Ninawe 2022Sagar KhursangeNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Life Skills in India: Dr.K.Kalyan Chakravarthy, Dr.B.Shanta KumarDocument6 pagesEntrepreneurial Life Skills in India: Dr.K.Kalyan Chakravarthy, Dr.B.Shanta KumarGangadhara RaoNo ratings yet

- Artikel 1Document8 pagesArtikel 1MariskaNo ratings yet

- Admsci 08 00018 v2Document15 pagesAdmsci 08 00018 v2margarida cabralNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: 2.1 CompetencyDocument17 pagesLiterature Review: 2.1 CompetencyGokul krishnan100% (1)

- Evaluating The Effectiveness of The On The Job Chapter 1 2 FinalDocument10 pagesEvaluating The Effectiveness of The On The Job Chapter 1 2 FinalApollo Simon T. TancincoNo ratings yet

- PrepublicationversionDocument32 pagesPrepublicationversionAmine NourazizNo ratings yet

- School Management System Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesSchool Management System Literature Reviewafmziepjegcfee100% (1)

- The Relationship Between Competency and PerformancDocument13 pagesThe Relationship Between Competency and Performancniar196No ratings yet

- Competency Mapping Among The Middle Level Managers in Bharat Electronics LimitedDocument6 pagesCompetency Mapping Among The Middle Level Managers in Bharat Electronics LimitedarcherselevatorsNo ratings yet

- The Competency Modeling ApproachDocument4 pagesThe Competency Modeling ApproachsaospieNo ratings yet

- Igwe - 2020 - What Factors Determine The Development of Employability Skills in Nigerian Higher EducationDocument13 pagesIgwe - 2020 - What Factors Determine The Development of Employability Skills in Nigerian Higher EducationHa LuongNo ratings yet

- Zakarevicius ZuperkieneDocument11 pagesZakarevicius ZuperkieneBookVikNo ratings yet

- HRM II - FrameworksDocument13 pagesHRM II - FrameworksAbhishek BishtNo ratings yet

- Life Skills Have Been Defined by The World Health OrganizationDocument9 pagesLife Skills Have Been Defined by The World Health OrganizationAshwini AshNo ratings yet

- Competency Mapping of The EmployeesDocument7 pagesCompetency Mapping of The EmployeesJijo Abraham100% (1)

- Developing Competency ModelDocument16 pagesDeveloping Competency ModelpinkNo ratings yet

- Transversal Competencies For Employability in University Graduates A Systematic Review From The Employers' PerspectiveDocument37 pagesTransversal Competencies For Employability in University Graduates A Systematic Review From The Employers' PerspectiveNguyễn LêNo ratings yet

- CHRM CHP.1 EbookDocument29 pagesCHRM CHP.1 EbookKarishmaAhujaNo ratings yet

- Leadership ManagementDocument17 pagesLeadership ManagementLugo Marcus100% (2)

- Examining The Impact of Talent Management Practices On Different Sectors: A Review of LiteratureDocument12 pagesExamining The Impact of Talent Management Practices On Different Sectors: A Review of Literaturedevi 2021No ratings yet

- A Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110Document22 pagesA Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110taufiq ismailNo ratings yet

- Stepping Up The Ladder: Competence Development Through Workplace Learning Among Employees of Small Tourism EnterprisesDocument9 pagesStepping Up The Ladder: Competence Development Through Workplace Learning Among Employees of Small Tourism Enterprisesnadine.galinoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)Document9 pagesInternational Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)IJERDNo ratings yet

- Assigment 2-8616Document20 pagesAssigment 2-8616umair siddiqueNo ratings yet

- TemJournalNovember2017 726 731Document6 pagesTemJournalNovember2017 726 731amin fatahNo ratings yet

- Continuous Improvement of NestleDocument7 pagesContinuous Improvement of NestleSheer Lee SamNo ratings yet

- The 70 20 10 Methodology - Jos AretsDocument19 pagesThe 70 20 10 Methodology - Jos AretsCorporate L&DNo ratings yet

- Competence Vs Competency The DifferencespubDocument4 pagesCompetence Vs Competency The DifferencespubShivraj RulesNo ratings yet

- Soft Skills Are Equally ImportantDocument2 pagesSoft Skills Are Equally ImportantBuzz LinggNo ratings yet

- Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory A Framework For Accessing Person Job InterationDocument9 pagesKolb's Experiential Learning Theory A Framework For Accessing Person Job InterationAlaksamNo ratings yet

- Employability FrameworkDocument24 pagesEmployability FrameworkSeyra RoséNo ratings yet

- Training and Development Initiatives in Different OrganizationsDocument17 pagesTraining and Development Initiatives in Different OrganizationsSusmita Sahu (Hunny)No ratings yet

- CHED Memorandum OrderDocument6 pagesCHED Memorandum Ordernikita dimagibaNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Self Assessment Model (e-LSA) : March 2012Document10 pagesE-Learning Self Assessment Model (e-LSA) : March 2012Montasar NajariNo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument9 pagesCourse OutlineShahriar ShuvoNo ratings yet

- Identification of Managerial Competencies in K-Based OrganizationsDocument14 pagesIdentification of Managerial Competencies in K-Based OrganizationsAlexandru Ionuţ PohonţuNo ratings yet

- How To Apply Responsible Leadership Theory in PracticeDocument21 pagesHow To Apply Responsible Leadership Theory in PracticeSaniya FayazNo ratings yet

- Manajemen StratejikDocument6 pagesManajemen StratejikMarysa NovegasariNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Employee Training Guide- Training Today, Leading TomorrowFrom EverandThe Ultimate Employee Training Guide- Training Today, Leading TomorrowNo ratings yet

- Adult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersFrom EverandAdult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersNo ratings yet

- Best Practices and Strategies for Career and Technical Education and Training: A Reference Guide for New InstructorsFrom EverandBest Practices and Strategies for Career and Technical Education and Training: A Reference Guide for New InstructorsNo ratings yet

- Shaving RazorDocument4 pagesShaving Razorprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing The Development of Digital ComDocument10 pagesFactors Influencing The Development of Digital Comprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Latihan WLKDocument1 pageLatihan WLKprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Sheet-Metal Forming Processes: Haipan SalamDocument86 pagesSheet-Metal Forming Processes: Haipan Salamprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Notice 20210926161537Document1 pageNotice 20210926161537Ramji DwivediNo ratings yet

- La Verne Academy Inc.: Drio - Magtubo - Rendon - VeraDocument18 pagesLa Verne Academy Inc.: Drio - Magtubo - Rendon - VeraGior NavarroNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois at Chicago Actg / Ids 475 - Database Accounting Systems Course Syllabus Fall Semester 2018 InstructorDocument5 pagesUniversity of Illinois at Chicago Actg / Ids 475 - Database Accounting Systems Course Syllabus Fall Semester 2018 Instructordynamicdude1994No ratings yet

- Onesseias Professional Growth Plan 2020-2021 DestinyDocument3 pagesOnesseias Professional Growth Plan 2020-2021 Destinyapi-544038337No ratings yet

- Basic IELTS Writing - Dep 1Document178 pagesBasic IELTS Writing - Dep 1Luu NamNo ratings yet

- Virtual ResourcesDocument3 pagesVirtual Resourcesapi-534006415No ratings yet

- Project Director or Senior Project ManagerDocument5 pagesProject Director or Senior Project Managerapi-78785489No ratings yet

- 55 Great Debate Topics For Any ProjectDocument4 pages55 Great Debate Topics For Any ProjectIndah RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Applied Linguistics and Language EducationDocument1 pageApplied Linguistics and Language EducationJose miguel Sanchez gutierrezNo ratings yet

- 8279 - CV Fahmi Aditya Yulvandi New PDFDocument1 page8279 - CV Fahmi Aditya Yulvandi New PDFdolibsNo ratings yet

- "Building Main Idea" Grade Level/Subject: Standards Targeted: CCSS - ELA-Literacy - RI.6.2Document5 pages"Building Main Idea" Grade Level/Subject: Standards Targeted: CCSS - ELA-Literacy - RI.6.2api-290076952No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 SENGDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 SENGManzur AshrafNo ratings yet

- G Vinoth KumarDocument3 pagesG Vinoth KumarSarathKumarNo ratings yet

- CV 2018Document1 pageCV 2018Khangal SharkhuuNo ratings yet

- Issc Meet 2024Document2 pagesIssc Meet 2024Ace E. BadolesNo ratings yet

- Shawn Wilson 2019 Resume FinalDocument1 pageShawn Wilson 2019 Resume Finalapi-494858359No ratings yet

- Pedagogical Province HESSEDocument7 pagesPedagogical Province HESSEFrancis Gladstone-QuintupletNo ratings yet

- Bulewich lp1Document3 pagesBulewich lp1api-510320491No ratings yet

- CORE Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person Q1Week1Document14 pagesCORE Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person Q1Week1tan2masNo ratings yet

- Confras Mod1 N PDFDocument7 pagesConfras Mod1 N PDFdexter gentrolesNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Mathematics 0580/22Document7 pagesCambridge IGCSE™: Mathematics 0580/22Jahangir KhanNo ratings yet

- DLP IdsDocument7 pagesDLP IdsDnnlyn CstllNo ratings yet

- Dopamine Pathways PDFDocument3 pagesDopamine Pathways PDFMuhammad Zul Fahmi AkbarNo ratings yet

- Supervisory Skills: Educational SupervisionDocument30 pagesSupervisory Skills: Educational Supervisionanna100% (1)

- L.D. Davis, Handbook of Genetic Algorithms : Artificial IntelligenceDocument6 pagesL.D. Davis, Handbook of Genetic Algorithms : Artificial IntelligenceArdhito PrimatamaNo ratings yet

- NNDL Assignment AnsDocument15 pagesNNDL Assignment AnsCS50 BootcampNo ratings yet

- Proposal Letter For The Jsprom PDF FreeDocument3 pagesProposal Letter For The Jsprom PDF FreeChristian Ancen AlforoNo ratings yet

- GE - LWR, Module 3Document7 pagesGE - LWR, Module 3jesica quijanoNo ratings yet

The Importance of Competency Model Development

The Importance of Competency Model Development

Uploaded by

prasetyokolik-1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Importance of Competency Model Development

The Importance of Competency Model Development

Uploaded by

prasetyokolik-1Copyright:

Available Formats

The Importance of

Competency Model

Development

Aija Staškeviča*

Abstract

Personal competencies are significant predictors of employee outcome. Nowadays, due to the rapid

development of technologies and increased automation level, competency requirements have

changed. Therefore, experts develop and make regular updates in the general competencies

and in the specific competency models for each industry. In 2018, the European Commission

developed the Council Recommendation on Key Competencies for Lifelong Learning, which

defines the core competencies necessary to improve performance, to sustain current standards

of living and to adapt to market changes. Competency models are particularly significant in order

to produce innovations where the educational level and knowledge and the skills and attitude

of employees are essential.

The purpose of the research is to define the basic concepts of actual competency models

and to determine the advantages of their development. This research is a literature review for building

a literature background for the next stage of the investigation, which will be empirical research.

The outputs of this research are four hypotheses on the influence of the practical application

of competency models, including the use of competency models in the development

and implementation of training programmes as a positive impact on learners’ results and attitude.

Use of general competency models does not ensure the implementation of fully-fledged

competency-based training programmes in a specific area.

The literature review has identified that the major advantages of the development and use

of competency models are improved performance and evaluation system optimisation. It

is essential for each industry to identify its own competency requirements although there are still

specific industries in which competency models have not yet been fully developed. It is concluded

that most of the research evidence on competencies is, nevertheless, related to medium and large

sized companies and industrial plants. Different approaches are required to analyse and develop

competency models depending on the company size.

Keywords: competencies, competency model, employee development

JEL Classification: M12, J24

Introduction

According to the first principle of the European Pillar of Social Rights, “Everyone has

the right to quality and inclusive education, training and life-long learning in order

to maintain and acquire skills that enable them to participate fully in society and successfully

manage transitions in the labour market”. It also states that everyone has the right to timely

and tailor-made assistance in order to improve employment or self-employment prospects.

This includes the right to receive support for job searches, training and re-qualification

* University of Latvia, Faculty of Business, Management and Economics (aija.staskevica1@gmail.com).

62 Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622

(EC, 2018). The competency approach can support the implementation of these conditions

in life. This is why, in 2006, the European Parliament and the Council of the European

Union adopted the Recommendation on Key Competencies for Lifelong Learning. Since

its adoption, the recommendation has been the main reference for the development

of competency-based education, training and learning. However, due to the rapid change

in the external environment, the requirements for competencies also change rapidly.

The work is more computerised, automated and robotised. Technological development

has a significant impact on the required skills and knowledge. It affects both the business

environment and everyday life. Based on the above, in May 2018, the European

Commission developed the Council Recommendation on Key Competencies for Lifelong

Learning defining the core competencies that are necessary to improve performance,

to sustain current standards of living, to adapt to market changes and to support high

rates of employment (CEU, 2018). In general, people need a set of appropriate and most

relevant competencies to meet the changing demands of the labour market and the required

standards. The development of competency models facilitates the solution to this issue.

The purpose of this research is to define the basic concepts of actual competency

models and to determine the advantages of their development. This research is a literature

review for building a literature background for the next stage of the investigation, which

will be empirical research.

1. Theoretical Framework

The essence of competency will first be determined in order to understand the concept

of competency models, the basic principles and the importance of their development

as well as to define their advantages.

1.1 Concept of Competency

In 1973, McClelland (1973) published the study Testing for Competency rather than

for Intelligence in which personal competency (defined as motives and personality

traits) or individual characteristics were recognised as significant predictors of employee

performance and success. The researcher’s work was provocative because he claimed

personal competencies to be a more important factor in predicting occupational success than

traditional psychometrics, for instance, IQ and aptitude tests. McClelland (1973) is considered

to be the founder of the competency theory in personnel management. Key competencies

are often used to describe an organisation’s competitive advantages. Boyatzis (1982) defined

competency as the underlying characteristic of a person that resulted in an effective and/or

better work performance. In 1990, Prahalad and Hamel introduced the characteristics of key

competencies of an organisation for the first time (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990).

The word ‘competency’ comes from the Latin word ‘competentia’, which can be

translated as ‘is authorised to judge’, respectively, ‘a person who has the right to speak’.

Skorková (2016) summarised various interpretations of the competency concept as follows:

●● Competency as authority and responsibility. An employee has the right to take

certain actions. Therefore, it refers to what was given to a person from the outside.

●● Competency as a person’s ability to perform certain activities – quality, skills

and the ability to do something competently.

Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622 63

There are several definitions of competencies. Mooney (2007) concluded that

different competencies are skills, knowledge and abilities that are characteristic of being

visible to customers and are better than those of their competitors and difficult to imitate.

In a strategic implementation, these different competencies can lead to sustainable

competitive advantages. Competencies can be defined as the mobilisation of knowledge,

actions and emotions used to create value (Bendassolli et al., 2016). According to the United

Nations Industrial Development Organisation, competency includes a combination

of knowledge, skills and behaviour that are practised for self-improvement (UNIDO, 2002).

Likewise, Salleh et al. (2015) determined that competency is a set of skills, knowledge

and behaviour that characterises a person‘s better performance in each particular aspect.

Competencies exist due to personal values in life, attitude and internal motivation

for the quality performance of tasks and the creation of excellent work. Competencies

are not only knowledge and skills; they are related to the ability to perform complex

tasks in specific circumstances (in a special context). Competencies are a proven ability

to responsibly and autonomously use one’s knowledge, skills and abilities (personal, social

and/or methodological) in different situations, for instance: work, study, professional

and personal development (Chiru et al., 2012). This means that a competent person must

be able to understand the circumstances and adapt to them depending on the situation.

According to the EU Council’s terminology, competency is a compilation

of knowledge, skills and attitudes where:

●● Knowledge is the facts and figures, concepts, ideas and theories that have

already been identified and support understanding of a specific field or topic.

●● Skills are defined as the ability and capacity to carry out certain processes

and use existing knowledge to achieve results.

●● Attitude is described as the person’s mindset and intention to act or react

to an idea, persons or situation (CEU, 2018).

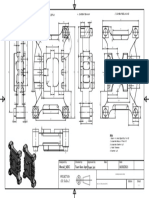

Another similar competency model has been developed, i.e. the Iceberg Competency

Model (see Figure 1), which includes the components as follows:

●● Skills

●● Knowledge

●● Attitude

●● Interpersonal skills

●● Motivation

●● Achievement (Salleh et al., 2015)

Figure 1 | Iceberg competency model

Clear competency Unclear competency

●● Skills ●● Attitude

●● Knowledge ●● Interpersonal skill

●● Motivation

●● Achievement

Source: (Salleh et al., 2015)

64 Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622

Consequently, there are several competency definitions that are similar to each other

although each organisation may have a different competency concept. To summarise,

it can be said that the core competency components include knowledge, skills and abilities

or attitudes.

1.2 Competency Model Concept

In the first development phase of the competency-based theory which lasted from the 1960s

to the 1990s, the study and evaluation of competencies were focused on the observation

of individual competencies. Competency was defined as a skill developed by self-

organisation and required to perform the person’s work. In the second phase, in the 1990s,

personnel management was focused on the creation of competency models and their

management in organisations. The third phase in personnel management, which continues

today, is the typical identification of the core competencies required to gain a competitive

advantage (Skorková, 2016).

The EU Council Recommendation for each person’s core competencies includes:

●● Literacy competency;

●● Multilingual competency;

●● Mathematical competency and competency in science, technology

and engineering;

●● Digital competency;

●● Personal, social and learning to learn competency;

●● Citizenship competency;

●● Entrepreneurial competency;

●● Cultural awareness and expression competency (CEU, 2018).

Everyone needs the key competencies referred to in the Council Recommendation

in order to improve performance, meet modern living standards, adapt to market changes

and be competitive in the labour market. Identification of competencies in society led

to the so-called competency model, which is characteristic of a particular position.

The group of key competencies forms a competency model. Therefore, the competency

model describes a combination of specific knowledge, skills and other personal

qualities required to effectively perform duties in an organisation. The model structure

should support the use of competencies across the selected human resource functions.

The competency model should give a clear definition of each competency, including

measurable or observable performance indicators or standards. These will be used

by the individuals who are the evaluators (Skorková, 2016).

There are two main competency model research directions. First, job-specific models

are focused on the development of specific skills in specific workplaces. Examples

of specific competencies include product knowledge, the administrative and technical

fields of private company managers, and the training and qualification building skills

for the training of specialists. Regardless of the specific competencies’ characteristic

for the jobs, there are some common core competencies such as entrepreneurial

competencies (for instance, strategic management, innovation and change), self-

expression and interpersonal competencies as well as leadership competencies (Shum,

Gatling and Shoemaker, 2018). Sisson and Adams (2013) have proved that general

Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622 65

competencies account for 86% of all competencies. This is why the second competency

research direction is focused on the development of general competency models. General

models pay more attention to business, personal and management competencies and place

less emphasis on technical skills.

2. Advantages of Competency Model Elaboration and Competency

Development

A knowledge-based economy, fact memorisation and procedural knowledge are important

but not sufficient factors for business success and progress. Such skills as problem-

solving, critical thinking, the ability to cooperate, creativity, and self-regulation are much

more relevant in today’s fast-paced society than ever. These are the tools that provide

the opportunity to work in real time, create new ideas, new theories, new products

and new knowledge (CEU, 2018). Human competencies affect their behaviour, ‘we

do what we can’ (Loots, Cnossen and Witteloostuijn, 2018). In addition, it has been proven

that persons believing that they are good at doing some kind of task and derive pleasure

from it, have a greater chance to persist in doing the task and improve their abilities even

more. The person’s perception that he or she is competent activates the said person’s

behaviour and ensures greater development in the particular field (Deci and Ryan, 2000).

The development of employee skills is essential for the continuous improvement

and adaptation of the workforce competencies.

Development of competency models has substantial advantages in different fields

(see Figure 2). The author compared the academic field with the private business and public

sectors because the goal of the academic field is to ensure competencies that will be useful

for two other sectors and the main advantages vary depending on sector aims. Competency

models are useful tools for teachers to identify and develop the knowledge, skills and abilities

required for future leaders (Sisson and Adams, 2013; Shum, Gatling and Shoemaker, 2018).

High-quality education, training and lifelong learning provide everyone with the opportunity

to develop core competencies. Therefore, a competency-based approach can be used in all

education, training and learning programmes regardless of the education level and age

(The Council of the European Union, 2018). According to the findings of Chih et al. (2003),

the analysis of content for competency in education and training is the essential factor

in order to increase training effectiveness. It also includes the development of standards

related to the identification of the competencies required.

Likewise, the development of competency models in companies allows identifying

the required skills that would contribute to the development of the organisation. Competency-

based management, in which competency models are the main tool in human resource

systems and practices, is currently topical. Competency-based selection is effective

in the rapidly changing business environment in which companies recognise the value

of interpersonal relationships, effective communication, teamwork, willingness to support

these changes, and the ability to learn quickly (Skorková, 2016). There is a considerable

range of studies proving the relation between different competencies and a company’s

performance and between different competencies and competitive advantages

(Fernandez et al., 2018). However, most of the evidence from these studies relates to medium

and large sized companies and industrial plants (Miller, Dröge and Vickery, 1997;

Fernandez et al., 2018). Small companies should constantly strive for a sustainable

competitive advantage over their competitors. Competency models can be used in many

66 Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622

human resources development areas, i.e. recruitment of officials, remuneration process,

training, job performance management and the elaboration of a development programme.

It is the main tool for employee assessment, career planning and talent management.

It should be mentioned that the final list of competencies included in the competency

model is sometimes a big surprise to the company who requested the model. It can reveal

the difference between what is officially expected by the company (declaring it in its

internal policy) and what is actually required from its employees (Skorková, 2016).

A person’s individual competency is something typical of a person that can be used

to predict the level of performance. It has been established that there is a correlation between

the employees’ competencies and their productivity (Buchel, 2002). Each individual’s

competency should be able to support the organisation’s strategy and any changes made

by management (Muizu and Yudomartono, 2016). A full assessment of the person is used

in the competency-based selection process. The main task is to determine the person’s

potential and how this person can contribute to the survival of the organisation,

quality of services, productivity, financial indicators and sustainable development

(Bharwani and Jauhari, 2013; Blayney, 2009). Competency-based human resources

management is regarded to be an effective means of people management in the private

and public sectors (Skorková, 2016). Another advantage of competency development

is that it is positively associated both with business performance and with the employees’

professional beliefs and job satisfaction (Blayney, 2009; Ko, 2012).

Figure 2 | Main advantages of competency model development

●● Development of skills and abilities of students

Academic field ●● Improvement of quality and effectiveness of teaching

●● Process optimisation of the development of standards

●● Contribution to the development of an organisation

●● Basis for the development of a human resources

management system

Private business sector

●● Improvement in company performance

●● Positive impact on the competitive advantage

of acompany

●● Basis for the development of a human resources

management system (including reasonable recruitment

Public sector

of officials, remuneration system development)

●● Reasonable employee assessment

Source: Author’s own processing based on the literature review

There is numerous research in which entrepreneurial and management competencies

were studied (Shum, Gatling and Shoemaker, 2018; Muizu and Yudomartono, 2016;

Bendassolli et al., 2016; Boyatzis, 1982; Blayney, 2009). Greater attention is paid

to management competencies since the quality of the management’s work has a strong

impact on the company’s success. These competencies include technical skills,

conceptual skills and human skills that support business development and management

(Muiz and Hilmiana, 2016). Man (2001) defined six dimensions of entrepreneurial

competency, including strategy, opportunity, relationships, conceptual, organisation

and commitment. The importance of entrepreneurial competency is confirmed by empirical

evidence. The major internal setback to entrepreneurship results from the emotional aspects

Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622 67

(fear of responsibility, fear of risks and stress, lack of self-confidence), relationship aspects

(lack of social networks), and the lack of significant leadership competency. Entrepreneurial

traits are persistence, the ability to overcome problems and limited risk-taking as well

as the ability to innovate and build social networks (Bendassolli et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, competencies must vary depending on the company’s industry, and not

all of the industries can boast of having a range of extensively researched competencies.

For instance, in the context of creative industries and given the peculiarities of this context,

studies on entrepreneurial competency and entrepreneurial personality are still limited

(Bendassolli et al., 2016). At the same time, creative and entrepreneurial competencies

are an essential precondition for the facilitation of competition and/or co-operation

(Loots, Cnossen and Witteloostuijn, 2018). Improved quality and competency result

in a significant improvement in productivity and the ability to produce competitive

creative products. This is important since investments in human capital are not small,

but results can often only be seen in the foreseeable future. And yet, literature provides

several combinations of competency model research that facilitate the attempt to find

the list of cognitive, emotional, moral and social competencies that would be better

aligned with creative industries and help understand the factors most directly related

to the successful performance of entrepreneurs in this work (Bendassolli et al., 2016).

In general, competency models are an effective tool for improving employee

performance both in the public and private sectors. They are particularly important

in the recruitment and training process; the development of competency models also

contributes to sound decision-making.

3. Results

The literature studied has undeniably demonstrated that the use of the competency-based

approach in academic and business sectors improves the results achieved. Therefore,

the author of the research proposes the following hypothesis, which will be tested

by an empirical study:

H1: The use of competency models in the development and implementation of training

programmes has a positive impact on learners’ outcomes and their attitude.

The literature review has shown that there are both general and specific competency

models. Their development helps find suitable job performers and also provides

the possibility to distinguish between a potentially average performer and a performer

whose performance will be higher than the average. However, regardless of the fact

that general competency models are important tools both for personnel selection

and development of training programmes, they cannot be fully applied in each field.

They need to be adapted depending on the activity type and company size. Based on this,

the following hypothesis is raised:

H2: The use of general competency models does not ensure the full implementation

of competency-based training programmes in the specific field.

According to the results, more and more attention is currently given to the knowledge

of students and college students, their abilities, skills and behaviour. This occurs during

68 Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622

the selection process and throughout the work and training process. One of the main goals

of competency models is to facilitate the employer’s experience in the evaluation process.

Two hypotheses are put forward in this regard:

H3: Today, in the evaluation process, more attention is given to employee attitudes

and skills rather than to their knowledge.

H4: In today’s academic environment, more attention is paid to student attitudes

and skills rather than to their knowledge.

Therefore, this research builds the literature background for the next stage

of the investigation, which will be an empirical study. In general, the research resulted

in four hypotheses on the importance of the practical use of competency models.

Conclusions

The research made it possible to draw the following conclusions:

1. Competency models are an effective tool for the development of employee

performance both in the public and private sectors. Their use is particularly

important in personnel selection, planning evaluation and training processes.

2. A wide range of research on the development of competency models is available

in literature but there are still specific industries in which the required competencies

are not extensively researched and competency models have not been fully developed.

3. General competency models form a larger part of the required competencies

in a particular industry but are not sufficient for the fully-fledged use of the competency

tool.

4. The competencies required depend on company size. Most of the competency

research evidence applies to medium and large sized companies and industrial

plants. Different approaches are required to analyse competency models and develop

standards depending on the company size.

5. At present, competency-based theories are focused on the generalisation

of competencies and the definition of key competencies in the market in general or

in a particular industry.

6. Researchers are currently more focused on the exploration of direct management

and entrepreneurial competencies and less focused on the competencies of low-level

performers or the self-employed.

7. The major advantages of the development and use of competency models

are improved performance, increased quality of training programme development,

evaluation system optimisation, reasonable personnel recruitment and a more

reliable prediction of their performance.

References

Bendassolli, P. F., Borges-Andrade, J. E., Gondim, S. M., & Makhamed, Y. M. (2016). Performance,

Self-Regulation, and Competencies of Entrepreneurs in Brazilian Creative Industries.

Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32, pp. 1-9.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-3772e32ne221

Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622 69

Bharwani, S., & Jauhari, V. (2013). An Exploratory Study of Competencies Required to Co-Create

Memorable Customer Experiences in the Hospitality Industry. International Journal

of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(6), pp. 823-843.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2012-0065

Blayney, C. (2009). Management Competencies: Are They Related to Hotel Performance?

International Journal of Management and Marketing Research, 2(1), pp. 59-71

Boyatzis, R. E. (1982). The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance. New York, NY:

John Wiley & Sons.

Buchel, F. (2002). The Effects of Overeducation on Productivity in Germany – The Firms’

Viewpoint. Economics of Education Review, 21(3), pp. 263-275.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00020-6

Chih, Y. C., Wen, C. L., Fang, E. C., & Yi, L. H. (2003). Construction of a Competency Analysis

Model for Vocational High Schools. World Transactions on Engineering and Technology

Education, 2(1), pp. 121-124

Chiru, C., Ciuchete, S. G., Lefter (Sztruten), G. G., & Paduretu (Sandor), E. (2012). A Cross Country

Study on University Graduates Key Competencies. An Employer’s Perspective. Procedia –

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, pp. 4258-4262.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.237

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs

and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), pp. 227-268.

https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

EC (European Commission) (2018). European Pillar of Social Rights. [online] ec.europa.eu.

Available at:

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/social-summit-european-pillar-

social-rights-booklet_en.pdf [Accessed 5 Jan. 2018].

https://doi.org/10.2792/95934

Fernandez, A. I., Lara, P.R, Ugalde, M. C., & Sisodia, G. S. (2018). Distinctive Competencies

and Competency-Based Management in Regulated Sectors: A Methodological Proposal

Applied to the Pharmaceutical Retail Sector in Spain. Journal of Retailing and Consumer

Services, 42, pp. 29-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.01.007

Ko, W. H. (2012). The Relationships Among Professional Competence: Job Satisfaction

and Career Development Confidence for Chefs in Taiwan. International Journal

of Hospitality Management, 31(3), pp. 1004-1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.12.004

Loots, E., Cnossen, B., & Witteloostuijn, A. (2018). Compete or Cooperate in the Creative

Industries? A Quasi-Experimental Study with Dutch Cultural and Creative Entrepreneurs.

International Journal of Arts Management, 20(2), pp. 20-31.

Man, T. W. Y. (2001). Entrepreneurial Competencies and the Performance of Small and Medium

Enterprises in the Hong Kong Services Sector [doctoral dissertation]. The Hong Kong

Polytechnic University.

McClelland, D. C. (1973). Testing for Competence Rather than for “Intelligence”. The American

Psychologist, 28(1), pp. 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034092

Miller, D., Dröge, C., & Vickery, S., (1997). The Impact of Performance on the Functional

Favouritism of CEOs in Two Contexts. Journal of Management, 23(2), pp. 147-168.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(97)90041-6

Mooney, A. (2007). Core Competence, Distinctive Competence, and Competitive Advantage:

What Is the Difference? Journal of Education for Business, 83(2), pp. 110-115.

https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.83.2.110-115

70 Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622

Muizu, W. O. Z., & Yudomartono, H. (2016). Competency Development of Culinary Creative

Industries. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 15(3), pp. 67-72

Prahalad, C. K., & Hamel, G. (1990). The Core Competence of the Corporation. Harvard Business

Review, 3, pp. 79-91.

Salleh, K. M., Khalid, N. H., Sulaiman, N. L., Mohamad, M. M., & Sern, L. C. (2015). Competency

of Adult Learners in Learning: Application of the Iceberg Competency Model. Procedia –

Social and Behavioral Sciences, 204, pp. 326-334.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.160

Shum, C., Gatling, A., & Shoemaker, S. (2018). A Model of Hospitality Leadership Competency

for Frontline and Director Level Managers: Which Competencies Matter More?

International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74, pp. 57-66.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.002

Sisson, L. G., & Adams, A. R. (2013). Essential Hospitality Management Competencies:

The Importance of Soft Skills. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 25(3), pp. 131-145.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10963758.2013.826975

Skorková, Z. (2016). Competency Models in the Public Sector. Procedia – Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 230, pp. 226-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.09.029

CEU (The Council of the European Union), (2018). Council Recommendation on Key Competences

for Lifelong Learning. [online] ec.europa.eu. Available at:

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.C_.2018.189.01.0001.

01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AC%3A2018%3A189%3ATOC [Accessed 13 Sep. 2018]

UNIDO (United Nations Industrial Development Organization), (2002). UNIDO Competencies:

Strengthening Organizational Core Values and Managerial Capabilities. Vienna: UNIDO.

Acta Oeconomica Pragensia, 2019, 27(2), 62–71, https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aop.622 71

You might also like

- Econ1 Syllabus Spring2016Document3 pagesEcon1 Syllabus Spring2016Josue Lopez0% (1)

- 4.10. The Data in Table 4.4 Are To Be Fit To An Eq...Document1 page4.10. The Data in Table 4.4 Are To Be Fit To An Eq...Ahmad AbdNo ratings yet

- WhitePaper - Universal Competency FrameworkDocument11 pagesWhitePaper - Universal Competency FrameworkTristia100% (1)

- Salvatierra Et Al. 2016 - Chilean Construction Industry - Workers Competencies To Sustain Lean ImplementationsDocument10 pagesSalvatierra Et Al. 2016 - Chilean Construction Industry - Workers Competencies To Sustain Lean ImplementationsAndrews Alexander Erazo RondinelNo ratings yet

- JETIRA006052Document7 pagesJETIRA006052Bhavleen KaurNo ratings yet

- 575 6154 1 PBDocument14 pages575 6154 1 PBHabtamu GedefawNo ratings yet

- 10 - 12 - HR PolyclinicDocument22 pages10 - 12 - HR PolyclinicPratiksha MaturkarNo ratings yet

- Performance Improve Qtrly - 2020 - Giacumo - Trends and Implications of Models Frameworks and Approaches Used byDocument40 pagesPerformance Improve Qtrly - 2020 - Giacumo - Trends and Implications of Models Frameworks and Approaches Used bywangshiyao290No ratings yet

- Comptency ModelsDocument24 pagesComptency ModelsEx SolNo ratings yet

- White Paper SHL Universal Competency Framework PDFDocument11 pagesWhite Paper SHL Universal Competency Framework PDFbedraabNo ratings yet

- Admsci 08 00018 v2 PDFDocument15 pagesAdmsci 08 00018 v2 PDFconteeNo ratings yet

- Developing Entrepreneurial Competencies in Higher Education A Structural Model ApproachDocument24 pagesDeveloping Entrepreneurial Competencies in Higher Education A Structural Model ApproachwiricardopNo ratings yet

- Softs SkillsDocument13 pagesSofts SkillsAs Su MaNo ratings yet

- IJCRT2101405Document15 pagesIJCRT2101405shrimisahaNo ratings yet

- Competency ModelsDocument11 pagesCompetency ModelsLovepreetSidhuNo ratings yet

- Research Report On EmployabilityDocument17 pagesResearch Report On EmployabilityFizza KhanNo ratings yet

- Competency Mgm. A Debate. 2009Document9 pagesCompetency Mgm. A Debate. 2009axon45No ratings yet

- A Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110Document44 pagesA Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110steven ngknNo ratings yet

- Competency Based Management: A Review of Systems and ApproachesDocument14 pagesCompetency Based Management: A Review of Systems and ApproachesAlexandru Ionuţ PohonţuNo ratings yet

- Talent Management As A Method of Development of The Human Capital of The CompanyDocument8 pagesTalent Management As A Method of Development of The Human Capital of The Company74081298No ratings yet

- Full Project Sumit Ninawe 2022Document53 pagesFull Project Sumit Ninawe 2022Sagar KhursangeNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Life Skills in India: Dr.K.Kalyan Chakravarthy, Dr.B.Shanta KumarDocument6 pagesEntrepreneurial Life Skills in India: Dr.K.Kalyan Chakravarthy, Dr.B.Shanta KumarGangadhara RaoNo ratings yet

- Artikel 1Document8 pagesArtikel 1MariskaNo ratings yet

- Admsci 08 00018 v2Document15 pagesAdmsci 08 00018 v2margarida cabralNo ratings yet

- Literature Review: 2.1 CompetencyDocument17 pagesLiterature Review: 2.1 CompetencyGokul krishnan100% (1)

- Evaluating The Effectiveness of The On The Job Chapter 1 2 FinalDocument10 pagesEvaluating The Effectiveness of The On The Job Chapter 1 2 FinalApollo Simon T. TancincoNo ratings yet

- PrepublicationversionDocument32 pagesPrepublicationversionAmine NourazizNo ratings yet

- School Management System Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesSchool Management System Literature Reviewafmziepjegcfee100% (1)

- The Relationship Between Competency and PerformancDocument13 pagesThe Relationship Between Competency and Performancniar196No ratings yet

- Competency Mapping Among The Middle Level Managers in Bharat Electronics LimitedDocument6 pagesCompetency Mapping Among The Middle Level Managers in Bharat Electronics LimitedarcherselevatorsNo ratings yet

- The Competency Modeling ApproachDocument4 pagesThe Competency Modeling ApproachsaospieNo ratings yet

- Igwe - 2020 - What Factors Determine The Development of Employability Skills in Nigerian Higher EducationDocument13 pagesIgwe - 2020 - What Factors Determine The Development of Employability Skills in Nigerian Higher EducationHa LuongNo ratings yet

- Zakarevicius ZuperkieneDocument11 pagesZakarevicius ZuperkieneBookVikNo ratings yet

- HRM II - FrameworksDocument13 pagesHRM II - FrameworksAbhishek BishtNo ratings yet

- Life Skills Have Been Defined by The World Health OrganizationDocument9 pagesLife Skills Have Been Defined by The World Health OrganizationAshwini AshNo ratings yet

- Competency Mapping of The EmployeesDocument7 pagesCompetency Mapping of The EmployeesJijo Abraham100% (1)

- Developing Competency ModelDocument16 pagesDeveloping Competency ModelpinkNo ratings yet

- Transversal Competencies For Employability in University Graduates A Systematic Review From The Employers' PerspectiveDocument37 pagesTransversal Competencies For Employability in University Graduates A Systematic Review From The Employers' PerspectiveNguyễn LêNo ratings yet

- CHRM CHP.1 EbookDocument29 pagesCHRM CHP.1 EbookKarishmaAhujaNo ratings yet

- Leadership ManagementDocument17 pagesLeadership ManagementLugo Marcus100% (2)

- Examining The Impact of Talent Management Practices On Different Sectors: A Review of LiteratureDocument12 pagesExamining The Impact of Talent Management Practices On Different Sectors: A Review of Literaturedevi 2021No ratings yet

- A Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110Document22 pagesA Gap Analysis of Business Students Skills in The 21St Century A Case Study 1528 2643 22 1 110taufiq ismailNo ratings yet

- Stepping Up The Ladder: Competence Development Through Workplace Learning Among Employees of Small Tourism EnterprisesDocument9 pagesStepping Up The Ladder: Competence Development Through Workplace Learning Among Employees of Small Tourism Enterprisesnadine.galinoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)Document9 pagesInternational Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)IJERDNo ratings yet

- Assigment 2-8616Document20 pagesAssigment 2-8616umair siddiqueNo ratings yet

- TemJournalNovember2017 726 731Document6 pagesTemJournalNovember2017 726 731amin fatahNo ratings yet

- Continuous Improvement of NestleDocument7 pagesContinuous Improvement of NestleSheer Lee SamNo ratings yet

- The 70 20 10 Methodology - Jos AretsDocument19 pagesThe 70 20 10 Methodology - Jos AretsCorporate L&DNo ratings yet

- Competence Vs Competency The DifferencespubDocument4 pagesCompetence Vs Competency The DifferencespubShivraj RulesNo ratings yet

- Soft Skills Are Equally ImportantDocument2 pagesSoft Skills Are Equally ImportantBuzz LinggNo ratings yet

- Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory A Framework For Accessing Person Job InterationDocument9 pagesKolb's Experiential Learning Theory A Framework For Accessing Person Job InterationAlaksamNo ratings yet

- Employability FrameworkDocument24 pagesEmployability FrameworkSeyra RoséNo ratings yet

- Training and Development Initiatives in Different OrganizationsDocument17 pagesTraining and Development Initiatives in Different OrganizationsSusmita Sahu (Hunny)No ratings yet

- CHED Memorandum OrderDocument6 pagesCHED Memorandum Ordernikita dimagibaNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Self Assessment Model (e-LSA) : March 2012Document10 pagesE-Learning Self Assessment Model (e-LSA) : March 2012Montasar NajariNo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument9 pagesCourse OutlineShahriar ShuvoNo ratings yet

- Identification of Managerial Competencies in K-Based OrganizationsDocument14 pagesIdentification of Managerial Competencies in K-Based OrganizationsAlexandru Ionuţ PohonţuNo ratings yet

- How To Apply Responsible Leadership Theory in PracticeDocument21 pagesHow To Apply Responsible Leadership Theory in PracticeSaniya FayazNo ratings yet

- Manajemen StratejikDocument6 pagesManajemen StratejikMarysa NovegasariNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Employee Training Guide- Training Today, Leading TomorrowFrom EverandThe Ultimate Employee Training Guide- Training Today, Leading TomorrowNo ratings yet

- Adult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersFrom EverandAdult & Continuing Professional Education Practices: Cpe Among Professional ProvidersNo ratings yet

- Best Practices and Strategies for Career and Technical Education and Training: A Reference Guide for New InstructorsFrom EverandBest Practices and Strategies for Career and Technical Education and Training: A Reference Guide for New InstructorsNo ratings yet

- Shaving RazorDocument4 pagesShaving Razorprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing The Development of Digital ComDocument10 pagesFactors Influencing The Development of Digital Comprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Latihan WLKDocument1 pageLatihan WLKprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Sheet-Metal Forming Processes: Haipan SalamDocument86 pagesSheet-Metal Forming Processes: Haipan Salamprasetyokolik-1No ratings yet

- Notice 20210926161537Document1 pageNotice 20210926161537Ramji DwivediNo ratings yet

- La Verne Academy Inc.: Drio - Magtubo - Rendon - VeraDocument18 pagesLa Verne Academy Inc.: Drio - Magtubo - Rendon - VeraGior NavarroNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois at Chicago Actg / Ids 475 - Database Accounting Systems Course Syllabus Fall Semester 2018 InstructorDocument5 pagesUniversity of Illinois at Chicago Actg / Ids 475 - Database Accounting Systems Course Syllabus Fall Semester 2018 Instructordynamicdude1994No ratings yet

- Onesseias Professional Growth Plan 2020-2021 DestinyDocument3 pagesOnesseias Professional Growth Plan 2020-2021 Destinyapi-544038337No ratings yet

- Basic IELTS Writing - Dep 1Document178 pagesBasic IELTS Writing - Dep 1Luu NamNo ratings yet

- Virtual ResourcesDocument3 pagesVirtual Resourcesapi-534006415No ratings yet

- Project Director or Senior Project ManagerDocument5 pagesProject Director or Senior Project Managerapi-78785489No ratings yet

- 55 Great Debate Topics For Any ProjectDocument4 pages55 Great Debate Topics For Any ProjectIndah RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Applied Linguistics and Language EducationDocument1 pageApplied Linguistics and Language EducationJose miguel Sanchez gutierrezNo ratings yet

- 8279 - CV Fahmi Aditya Yulvandi New PDFDocument1 page8279 - CV Fahmi Aditya Yulvandi New PDFdolibsNo ratings yet

- "Building Main Idea" Grade Level/Subject: Standards Targeted: CCSS - ELA-Literacy - RI.6.2Document5 pages"Building Main Idea" Grade Level/Subject: Standards Targeted: CCSS - ELA-Literacy - RI.6.2api-290076952No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 SENGDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 SENGManzur AshrafNo ratings yet

- G Vinoth KumarDocument3 pagesG Vinoth KumarSarathKumarNo ratings yet

- CV 2018Document1 pageCV 2018Khangal SharkhuuNo ratings yet

- Issc Meet 2024Document2 pagesIssc Meet 2024Ace E. BadolesNo ratings yet

- Shawn Wilson 2019 Resume FinalDocument1 pageShawn Wilson 2019 Resume Finalapi-494858359No ratings yet

- Pedagogical Province HESSEDocument7 pagesPedagogical Province HESSEFrancis Gladstone-QuintupletNo ratings yet

- Bulewich lp1Document3 pagesBulewich lp1api-510320491No ratings yet

- CORE Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person Q1Week1Document14 pagesCORE Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person Q1Week1tan2masNo ratings yet

- Confras Mod1 N PDFDocument7 pagesConfras Mod1 N PDFdexter gentrolesNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Mathematics 0580/22Document7 pagesCambridge IGCSE™: Mathematics 0580/22Jahangir KhanNo ratings yet

- DLP IdsDocument7 pagesDLP IdsDnnlyn CstllNo ratings yet

- Dopamine Pathways PDFDocument3 pagesDopamine Pathways PDFMuhammad Zul Fahmi AkbarNo ratings yet

- Supervisory Skills: Educational SupervisionDocument30 pagesSupervisory Skills: Educational Supervisionanna100% (1)

- L.D. Davis, Handbook of Genetic Algorithms : Artificial IntelligenceDocument6 pagesL.D. Davis, Handbook of Genetic Algorithms : Artificial IntelligenceArdhito PrimatamaNo ratings yet

- NNDL Assignment AnsDocument15 pagesNNDL Assignment AnsCS50 BootcampNo ratings yet

- Proposal Letter For The Jsprom PDF FreeDocument3 pagesProposal Letter For The Jsprom PDF FreeChristian Ancen AlforoNo ratings yet

- GE - LWR, Module 3Document7 pagesGE - LWR, Module 3jesica quijanoNo ratings yet