Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Geographic 1997

National Geographic 1997

Uploaded by

renaivaa880 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views234 pagesOriginal Title

National Geographic 1997 (11)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views234 pagesNational Geographic 1997

National Geographic 1997

Uploaded by

renaivaa88Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 234

=

EON, . =,

eee y ey SG See

NATIONAL

eee Ie

0

NATIONAL

GEOGRAPHIC

From the Editor

Narionat. Geocaapuie and insects

go way back together. fy 1915, for

azine

a locust plague in Jerusalem. Maybe

that's why scientist and photographer

Mark Moffett feels so-at home with us

instance, th orted on

“1 was a biologist from diaper

says Maflett, whose photographic essay

about fighting flies appears in this

issue. “The insects in my back

much more cony

ard were

ent ty study than,

whales ana chi

panzees

Moffett’s junior high science project

(right) was an insect collection that

would make an entomologist proud. By age 17 Moffett was

8 yard, work

inseet experts in Central and South America. He earned

his doctorate at Harvard University, thanks in part to

National Geographic Society grant to ream Asia studly

marauder ants. From the field in 1985 he sent a few rolls

of film to our headquarters for pr g. A sharp-eyed editor named Mary

Smith spotted his work—and a star was born.

M ubjects with an eye for big-game-type dram:

Marauder ants stage coordinated assaults an their p

mulch to grow fungus on whieh they feed; tarantulas with specially adapted fee

walk acrass rising Amazon floodwaters to find new homes

L believe NaTioNAL GrocnAPHtc ist

visual stories like these,” says Moffett. “Th

far fre

gas aN assistant to reptil

ing

fiett approaches his tiny

leafcutter ants create

only place that offers the seope for

pace to phiy stories

from start to finish, You see insects ducling, but you also see the battle-scarred sur

vivors. As a scientist, I'm just glad a resource like National Geounarrte exists.

Of course this magazine has flourished in large part because of the talentandt

resourcefulness of writers, researchers, and photographers like Mark Moffett

whether they found theit youthful inspiration on their stomachs sctutinizing ants

takes the

ma

ae

and plants or on their backs gazing up at the heavens,

AMER 199)

DR

Ce ed

behind her. S

s sprawling

e has

scoots dow

Roman Cathol

1 corridor toward the ceramics

sure

ry since she retir

There is Sister Matthia, 103, whose nimble

fingers have for the past several years knit a

pair of mittens every day for charity. When

arrived, she was on her 1,374th pair. And there

is Sister Liguori, 89, and Sister Clarissa, 87,

biological sisters who laugh and joke about

their antics in elementary school, which they

remember as though it all happened last year.

But not every sister has defied Father Time.

Ina quiet room at the convent | meet a group

of six nuns sitting in wheelchairs pulled up

ta a large round table, Most are younger

than their “supersisters," yer their backs are

bunched, their eyesare glazed, and some havea

trickle of spittle in the corners of their mouths.

Alaheimer’s discase, strokes, and osteoporosis

have robbed thent of their minds and their

freedom to mowe about.

Why? Or more precisely: Why them? What is

it about some people that makes them such

casy targets for the arrows of time, while others

remain so resilient for so long?

David Snowdon, the University of Ke

epidemiologist who directs the million

a-year Nun Study, is finding out, Hix

research —along with other scientists’ studies.

of worms, Mes, mice, and monkeys—is helping,

answer the fundamental qqu ns of how anid

why we decline as we age and whether there is

anything we can do abou

Snowdon, a gregarious researcher) who

grects most of the sisters hy mame when he vis

its, looks a little wut of place at this staid con.

vent, with his hovish face crumpled suit, and

Jong, unkempt bait. But the convent isa perfect

place to study aging; he says, because all the

nuns have such similar backgrounds. All have

spent their years eating simular food, getting

similar educations, and. working similar ca-

reers, while shunning cigarettes, alcohol, mar-

riage, and childbearing. With those lifestyle

variables all canceled out, it’s easier to figure

cout which biological factors make the diffe

‘ence between those who age quickly and those

who don't.

Already Showdon's stuily has led te the

unexpected discovery that some af the mem

ory loss and dementia that aiflict people

with Alzheimer’s disease may be due not 19

Alzheimer's itself butte tiny unnoticed strokes.

Since many strokes are preventable, the find-

ing has shaken the image of Alzheimet’s as un

unstoppable diseuse. Snowdon’s work suggests

Ge NEW ANSWERS TO OL QHESTIONS

that something 4s simple us king an aspi-

rin a day might prevent the symptoms of

Alzheimer’s in some people, nat by curing ft

but by preventing the strokes that do the bulk

of the damage.

“L never would have imagined spending my

career with a convent full-of aging nuns,” says

Snowdon, in mock seldleprecation. “Bul this

place is like a gold mine. We're just starting to

dig it, and we'te alteady getting the answers to

so many questions”

‘HE QUEST To UNDERSTAND the nature of

aging—and the corollary quest to aveid

growing old—dates back at least to bib

ical times, when the elderly King David was

advised to allow a young virgin to warm him.

Sages: scientists, and snake-oil salesmen

have offered countless other antidotes since

then. In the third century ‘Taoist philosophers

recommended ingesting cinnabar, the toxicare

‘of mereury,a prescription that may have ended

more lives than it prolonged. Medieval Latin

alchemists tried in vain to make gold digest.

ible, in the belief that its absorption into

the body would add years to lite. In the 17th

century & more affordable remedy for aging

won popularity—smelling fresh earth upon

awakening each day,

But niany gerontolagists of old sided with

Sir Francis Bacon, who believed that life span

wits determined by how quickly one used

up one’s personal store of “vital spirits.” Still

others focused on the possibility of getting

vital-spirit refills (rom fountains of youth, my

thologized in many cultures long before Ian

Ponce de Ledn deupped anchor aff the Florida

shore wo look for his imagined fountain.

‘Today many advocates of life extension are

pinning their hopes on molecular bielogists,

who with remarkable speed are teasing-apart

the hormonal, cellular. and genetic underpin

of old age, Their promising assault on

the biology of aging is stirring up some difft

cult ethical and econmic questions:

Arc longer lives necessarily better lives?

Who should decide how lang a person

should liv

How would future generations fare in a

world where the elderly—ne matter how,

beloved —refused to depart?

Ready or nol, a global experiment in life

extension: is under way. ‘Thanks largely to

Aging in animats may ulti

mans, Savannah River ¢

They don't become dodder

why do they die

River Silvery

gist Richard J

NIA g

st Who serves as

tar. Vision

e their abilit

hear higher J tone ter Low pitch

recon er and by

nderlying scaffolding of structural proteins

becomes t les waste

lly around

cd with cay

way and fat accumulates, espec

ities and prc

1. The heart gi

efficiently as it once did. And virtu

ws weak and can't p

other orga goes into-a gradual tailspir

cially the kidneys and lungs, which for some

‘on wear out especially qui

It may not be a coincidence,” Andres tells

us with a

Nature provid

$ pauyes for a moment, putting down

1c colored marking pens that he's been us

thing hopeful about

every part of the body dec

of aging and that

that proc

hallmarks

archer

identified that key by

ox

ton 21 olde

The researcher was Daniel

of Wisconsin in

Rudman knew that as people got older, thei

pituitar

glands p and smalle

a substance called human growth

J: Might the symptom:

For

1 to Bl

thie times a week

the substance

The result

¢ men's mut

mass increased by almost 9 percent, fat

Jecreased by more than 14 percent, and skir

thickness increased by 7 percent—change

th e equivalent to turning th

Ce

ee eed

Cee)

‘5 8 guide. Unrepairable damage

Se tune culud

Se ta LL

Rene a

ee oe ater)

ete

Gey

Lienenrernen ety

Seen dl

Cede

ikea

‘oxygen and a hydrogen atom) and

auntie caubarsseattonan

with an unpaired electron. Most free

pecmryirharruaneg i cedrergacee

eee ed

ee

Cae ee

cre noes

te say

Cede ee eed

Pe reried ta lcedumetotkouone’

Ct

osome. Tolomeres get shorter with

‘call division, Finally, some scientists

Oued

believe, they

longer divide, and it becomes vulnerable

Pod

Mh eo has

AGE?

De ae

SU a aC

Rl Cee es]

at Ra ecu

Do ed

intricate, interlocking, and

CRU mute ad

RL mesh me

Pee set meet

the complexities of our own

Dene

ee er eee ad

re aaa iar)

UCR LU al

Ruri ad

CMe cd

Cee enue a

ce a

BU Delete EU)

Cu ts

My enka Lal

some regions, Reaching Its maximum

of about three pounds at age 20, 1

ee te

mee ee

Ce ee

Sete ty

ee ed

Fe eee ee

Cy

all times,” says Fozard.

ee PUR

! Be eed

i declines with age, but the ree-

‘sons are not wall understood.

HOW DO WE

aN Gl Us

oe ae eeu

eae etd

Sen ote Rac

eee eee nied

Baltimore Longitudinal Study

Ce eae a

Bee eects

specialists track the health

of more than 1,100 vol-

Meee ET Cond

eeu eye

eR eee

eee gett

Feat ag

Rec tod

Daa

Rt ken od

‘entering the eye diminishes. Aiso, as

P Cee ed

the normal aging process is Pr nae acme sad

PC eee Ea Ce ee ne brio

Peace om [penne veer pour vee tet pee te

ee et eter peng lyereaperactey toad

the changes in the body that Cu eet al euh cate ete

Ce aL lice emia ai tiaaen aie ieee ial

rs

cad

ieee ecureuil

healthy heart compensates tor aging in

Se ate te ck

LhsthoaptuAael hand atl dipdinpahee

‘thicken, for instance, putting more muscle

into pushing the blood through stiffening

Ce gee te eed

‘as hard as it once could. Yet when the

body moves—even just to stand up—

ee eet et es

Sekai eather henetoes

{tricles stretch, allowing mare blood to

Ce eae

Losing elasticity, lungs cannot in-

ena

Dr tadonbekueubecea ue

tal

Ce Lees

Ce eae

eae

Ce oy

ee eo kota ct

Ce te aes

eet ee

CO

Lr Lakeledoe sce peel

ee ad

Ct dudeatal eal

Pedic eu eed

ak ateauchbde rhedeas

disease growrs, catching up with

that of men at about age 60. A

‘man's testestorone level falls

Se oa Lenidalnbea

eens

Fein”

Festetibehubeeeecicduciad

have an enlarged prostate gland,

eee

eee era]

replaced throughout life. At about

Cera ed

overtaking replacement, Meno-

pause intensifies the loss: bones Doce

Cutie

eo ore Ru

Wear and tear resutts in

Seeman Luluien bared

F } eapuncahic al ced

ira | ‘erodes, and bone grinds

eee od j pease

during every decade of increasingly sed- pewienabeti aeratssne er

Ce ee)

Pte aa ad

‘strong as that of a 30-year-old. Regular

eerie

the era of eternal youthfulness might be nigh.

But it wasn't long before the growth hor

Tone joined the ranks of other erstwhile foun-

tains of youth. Many of the men developed

side effects, including carpal tunnel syndrome

fan inflammation of the nerves), diabetes-like

symptoms, and the unexpected growth of

breasts. Morcover, a8 spon as the men stopped

taking the hormone—which casts $10,000

Ww $20,000 for a year's supply —its benefits

quickly disappeared. The muscles melted away.

‘The fat came hack. The old men were simply

old men again.

Since then, the anti-aging spotlight has

swung to other harmones that also naturally

decline with age, such as' DHEA (dehydrocpi

androsterone, the function of which remains

largely unknown) and melatonin (made by the

pineal ghind in the brain, where it seems to play

a role in setting the body's biological clock).

Both hormones haye attracted a lot of media

attention.

But while replacement doses of certain har-

inones miy eventually be shown to have spe-

cific benefits, as with estrogen replacement to.

protect against heart disease and asteaparo.

sis in some menopausal women, the scientific

consensus for now is that ny single hormone

holds the secret te youthfulness.

people may hold aging at hay fue a while. But

for every Sister Esther there are countless

others already disabled by the time they hit 60,

So fam heartened by my-visit to Caleb Finch

at the University of Southern California in

Los Angeles. Finch is a world-renowned biel-

gist who has gained a special perspective

on aging by studying the process in hundreds

‘of species, from African, elephants to bristle-

cone pines.

“There is no reason to believe that there’:

un intrinsic limit to how long we-can live,”

nich tells me in his office, where an hourglass

hints at his interest in binlogy's battle against

time. “Life span, he tells me, “is completely

malleable.”

That doesn’t mean that many people are

alreasly exceeding the 120-year life span gener

ally thought to be the upper limit of reasonable

expectation, In fact Finch wishes everyone

would forget all the apocryphal stories they've

heard about remote villages where, thanks to

| LEAVE HALTIMORE a little despondent. Some

8

good yogurt or other secrets to long life, the

indigenous people supposedly live to 150 or

more. Some of these villages had found it was

good business to lie about their residents’ ages,

Finch tells me, as it brought planeloads of

tourists with money to spend, nat fo mention a

parade of research:

The oldest person ever documented was

Jeartne Calment of Arles, France, a snft-spoke

but sassy senior who reportedly quit smoking

Cigarettes just five years before her death last

Atigust at 122.

‘That humans have the potential to live that

long—longer than any other mamunal and far

longer than the maximum known life spans of

most other species:—is partly.a tribute to our

being such an intensely social species. In most

speciey individuals don't live very long after

they've grown old and infertile. Once an

animal has lost its capacity to have offspring;

the prime directive of evolution, there is little

incentive for mature to favor its continued

survival.

Burt for social species like ours, there are ben-

efits to haying adults survive longer thary it

tukes to raise their young, Grandparents gener-

ally make fine baby-sitters, for example, freeing,

the parents to gather food and protect their

territory. Atl in some species only the oldest

few may remember where water or other re

sources can be found during extreme droughts

or other shortfalls that occur only a few times:

in acentury.

No matter how useful they may be, however,

old people do eventually became weaker and

more prone to medical problems ind ace’

dents. So if scientists hope to extend the

maximum human Tife span beyond Madame

Calment’s record, Finch says, they will proba-

bly have to find owt what causes that decline.

Biologists argue vigorously over what, exactly,

that fundamental mechanism of aging is.

One camp says: that aging is linked to

genetic programming. ‘The other says that

aging is mostly a matter af physical wear and

tear—especially from exposure to oxygen, a

Fekyll-and-Hyde element both necessary and

damugiiig to. most organisms

Either way, scientists have the potential to

slow the process down, but which hypothesis

should they focus an?

Life spans in olher spec

clues, Finch says, Fruit fli

s may hold some

live for 30 te 40

NATIONAL GROGIA HH

=, NOVEMIER 1907

ly ars, ( Longer, healthier lives could result

slow! metabolism. It may’ bie ne coincidence

that many other animals with slow metabolism

alse enjoy relatively long life spams, includ

injt various species of snakes, fish, and frogs

No one knows, however, whether individual

people with slightly slower metabolic rates live

significantly longer than their fast-burning

counterparts, And the rule is not perfect: Some

birds with very high metabolic rates, for exam

ple, Hive quite a long tir

Ongoing studies may determine whether

turtles’ longevity is due primarily to their

cells’ genetic programming, or to their cold

blooded chemistry—or to some entirely dif-

ferent evolutionary adaptation, But if turtle

studies are yoing tw lead to life ex

for people, Gibbons %

the situation.

Alter all, people are the only serious threat {0

the survival of these otherwise long-lived rep:

tiles. People capture them for pets, kill them for

their shells, and drain their wetlands to build

homes for the aged.

‘If turtles knaw what's good for them,” Gils

bons says, y won't pive away their secret.

$a certain irony in

Never THoweHT I'd be looking for a foun

tain of youth ina dish full of worms, but

that's what I'm doing in Boulder, Colorado.

The worms are nematodes only a millimeter

long—a tiny squiggle of a species called

Caenorhabditis elegans, Although they live in

soil and feed an putrefying

surprisingly beautiful when viewed through

a microscope, shimmering and. translucent

y wriggle across my field of view in a

shallow ish of putrients, Most: (mpressivi

the ones tam looking at are almost 40 days

old, of about twice the

ctetia, they are

normal nematode

life span.

Their longevity is due to single mutation

in one of their 13,000 genes—a gene aptly

1, Tom Johnson, the University

Colorado researcher whiose lab I am visitin

fecently

nes that, when mutated,

explains that age-I is one of severs

isolated nematode yg

care greatly: extend a worm's life span. The dis:

covery gave credence to the nation that aging

may be controlled hy a molecular program.

It hus been known far some time that genes

can influence life span. A good way 10 predict

how long a person will live 1s te find out how

long his parents lived, evidence that longevity

AGING—NEW ANSWERS To OLD QUENTID

Mutations good and bad could offer

information leading to cures for many

disoases of old age. Caterina Segala, 20,

and some other residents of Limone, Italy,

carry a gene that boosts the effects of

beneficial cholesterol, lowering the tisk

of haart disease. In San Diego 12-year old

Courtney Arciaga shows off her basketball

‘skills. A mysterious mutation at concep:

tion has given her symptoms of the very

old, such as.a wizened appearance,

is at lea

st partly inherited, Some genes affect

indirectly, by altering the adds

of getting adeadly disease, But lately scientists

have discovered a few genetic mutations that

life expectane

appear to affect aging specifically.

Last y searchers identified

4 mutation that causes Werner's syndrome,

4 disease that mimics certain aspects of the

human aging process, People with Werner's

grow wrinkled and gray while they ate still

in their 20s, develop eataracts a few years

later, get cancer and heart disease in th

3s and 405, and usually die before their

50th birthday,

Recent studies suggest that the Werner's

mutation shortens life by interfering with the

body's ability to repair the damage caused by

metabolism, while the age-I mutation length

ens life hy enhancing the ability to reduce.

for example,

resist, or repair the damage done. Could the se

cretof longevity lie in something as baste as the

ability to counteract the ill effects of metab:

olism? And if'so, is there a way te cool tharmet

abolic furnace without changing our genes?

Ick Wempaten of the University of

R Wisconsin-Madison isa trim, bearded,

blue-jeaned scientist and marathon

runner wha believes the answer to those ques:

tions is yes. Hik secret to long life? Eat less.

Expanding on studies done in the 1930s,

Weindruch and his colleagues have shown that

by reducing calorie intake 60 percent, lab-

oratory mice can be made to live as much as 30°

percent Jonger than normal, tt is the only

proven method of extending life span in mam-

mals so far, And although it has net yet been

studied systematically in people, Weindruc!

and others suspect it would have the same ef-

feet as it does in mice: longer life, stronger im-

inune systems, lower and delayed incidence af

diabetes, cancer, and other ailments of old age.

‘The dict is tricky, Weindruch tells me, since

it's hard to cut out that many calories and still

get all the nutrients you need. But it works-

possibly by deercasing the damage that comes

with metabolism.

Lately, Weindruch has been putting mice on

restricted diets in their middle age. “t have a

history of starting caloric restriction studies on

animals that are the sane age as I um,” the 47

year-old jokes as we head over to the building

where his mice are kept

Inssicte the low-profile brick complex, Wein:

druch shows me huge barrels of yellow powder,

the nutritional staple for his subjects. Enriched

with all the vitamins and minerals a mouse

needs, it is mixed with hot water and a gelling

agent to makea cheesecake-like substance with

only one-third the standard number af calories

fora lab mouse, Then he leads me inte a room

with stacks of wire cages filled with charcoal

colored mice.

“Look at these coats,” Weindruch says, ad

iniring the animals’ fur."“‘They look like young

mice, but they're nat. This guy is 32 months.

old,” already a few months. older than most

mice of this type ean be expected to live, "Ser

enty percent of bis group are still alive, com-

pared with 28 percent of the controls who have

been cating standard diets, And that's even

though he ate a normal diet until he wasa year

old-—middle-aged for a mouse.”

We walk into anather roam, where the con-

trol mice have béen kept. I's full of cages, but

nearly all are cmpty. “Here we're down to 21

animals from the original 75° Weindruch tells

me. “And you can see what kind of shape

they're in.’ Some are limping, others have bald

spots or tumors, (When I call Weindruch for

an update four months later, he tells me that all

the elderly controls have died, but 15 of the

geriatric mice on restricted dicts are still going

strong. After another four months, eight of

those were still alive—as old in “mouse years”

as person aver'a hundred.)

We leave the me lab and head to the

nearby Wisconsin Regional Primate Research

Center, where similar experiments ore under

way on & group of aging rhesus monkeys. The

experiments must run much longer than the

mouse studies because rhesus monkeys typi-

cally live for 30 years or more, but the results

after eight years of caloric restriction in these

middle-aged monkeys parallel those from the

rodent work.

There is a downside to caloric restriction,

however, which is obvious even to a casual

observer who visits during mealtime. The

monkeys go-ctazy when the food shows up,

grasping at their meager rations. 1 think about

what it would take to cut even 30 percent of the

éalories from my daily fare. | broach this prob-

Jem aver Junch with Weindruch. He puts dew

his fork and concedes that hunger may be the

biggest roadblock to human life extension by

calorie restriction.

“Even a guy like me, whe has studied this for

20 years, can’t pull it aff he confides with just

a-hint of shame. “I'm unable to subject myself

jo whar | subject my animals to.”

Weindruch recommends a diet low in fat (to

minimize the number of calories consumed)

and high in fruits and vegetables (in part be-

cause they are rich in free-radical-quenching

antioxidants). {look down at my calorie-laden

fe practically passes

before my eyes. But 1 am hungry, so | eat,

JAM NEISON, & physiologist at the

US. Department of Agriculture's

M Human Nutrition Research Center

on Aging in Boston, doesn't need to cat like

a bird, She's already found her fountain

‘of youth,

Tam talking to Nelson’ at the physiology

laboratory on the Tufts University campus.

Here she and colleagues Maria’ Biatarone and

William Evans have conducted a remarkable

series of experinients with frail eldetly people.

The room is filled with treadmills, exercise

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC,

COVEMIER 1997

Tacs

rr

ea]

COUNTRIES, 19:

Pena

Pui Ula

perrenrecnad

ie Pend

ELDER BOOM

Peete a

eee Ce]

mC ecm i

CRC

eae eet kar)

Pee ce

Pee ea nee an

Mee cerns)

CU ur)

eee eee ie

Pea ane)

Pe ce

eed

population is expected to

pts aire

A handstand is child's play for litelona

ith complica

ot you keep us in mind, Human be

\a

RY oc ie _

eg aoa. 4

pe me

aa > —* \

ey ae

Wilderness Rafting

L

Pees ea se ted

Cea Ui

ee is

Cree eet

ode ane ce

Pours

ee ea

Pa ee tee oa

te ae ns

CC er)

Re ih ee

hockey helmets, home-

Ss €

Siberian § le Fait

Photographs by DUGALD BREMNER

URL SNiGue Was in

serious trouble, The

thundering Oygaing

River had just seized

makeshift birch-log

caturaft and sent it cartwheel

ing over a ten-foot waterfall.

‘The overturned craft's twitt

pontoons—patched like sec

ondhand inner tubes and

lashed to a frame of freshly

cut timbers—bucked and

swirled in the cauldron below

the drop. The veteran expedi-

tion leader and his young

protégé, Andrei l2hitsky, were

trapped in the hole upside

down, held {ast to their pon

toons by thigh braces impro-

vised from lenigths of fire

hose. Precious seconds were

ticking by.

Suddenly Andrei popped

to the surface gasping for ait,

followed immediately by

Yurl's paddle—a bad sign,

Several days earlier at the put=

in, in eastern Uzbekistan near

the river's source high in the

Tam Shan range; the hard-

boiled leader's send-off had

been terse and unceremo

nious: “If you capsize, don't

lose hold of your paddle”

Along minute passed

before Yuri appeared, now far

downstream and obviously

dazed, ‘Too weak to cling to

rescue lines his team

heaved from shore, he was

swept along like a rag doll for

hundreds of yards betiore is-

aring around a bend, By

wherdied

ortier this year inva Katyakis

lent, worked! aga elory gnitde in the

Grand Canyon betore embarking

onacareer ax an adventure pho:

toprapher, Micatark MeRan, whe

lives im Ashland, Oregon, iy the

author of Gratniuental Drifter: Dis

ppishes fawn the Utterewast Parts

of the Fite. This i bs fr aticte

for NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

4

the time his teammates found

him, he was crawling up on

the tocks—pale, shiv.

ering, and retching

water. The others

rushed to help him, but

he was ina black mood

and waved them away.

They helped him struggle

out of his sodden clad.

hoppersand homemade

overalls anyway, and

stripped off his flimsy

green fishing waders, which

bulged with water: Sitting by

himself in his disintegrating

long johns, he putied ciga-

rele after cigarette until, 15

minutes later, he'd regained

his steely composure.

“This was traditional Siberi-

att wilderness rafting: short

on cash, lang an ingenuity

and determination, pitting

bouts of military surplus

sterial and foraged Ings

against the great white-water

rivers of Central Asia and

castern Russia. Yuri and

his five teammates were

members of the municipal

outdoor club in the Siberian

city of Rulstsovsk, and’ pas

sionate about their-sport—

as they would have to be,

given the state of their

equipment and their prefer-

ence fer extreme rivers.

With as much authority as

he coukd manage, Yuri sum-

moned the team, Tall and

sinewy, he ware owlish g

and a downturned mustache,

He announced that two

members of the group would

immediately run the falls in

the bublik, a bizarre-looking

craft with twe doughnut-

shaped pontoons linked by

15sfoot logs. Instead, the

team decided to hike upriver

to the previous night's cam

for lunch, and, after slurping

NATIONAL

down bowls of lentil soup, all

but Sergei Ushakov lay back

inthe sun for a smoke. The

usually exuberant electronics:

engineer of 43 rose to speak

his mind.

Being the oldest member

of this team," he began

iitavely, choosing his words

with care, “E have a right to

express my opinion, Consid

ering the events of this day, [

think everyone needs to take

this river more seriously.”

Until then Yuri’s judgment

had gone unquestioned. As

GROGRAMHIC, NOVEMBER 1997

Arrive By.train

roa Subtsorh

Burwenep with overloaded

backpacks, the team forges

across the bleak beauty of a —

glacial pass (above) high in

the Tian Shan range of Kyr

gysstan, The rafters carried

everything needed—food,

clothing, and the deflated

components of their ratts—

in loads of 100 pounds or

more. Just to reach this: {

Sh ymikiint

point, they endured

36 muscle-stiffening

hours on the train

fram Rubtsovsk, then

journeyed by van to

11,300 feet, where

they started the ten

mile hike across the

pass, At 11,800 feet, team

leader Yuri Snegir slumps

‘on the edge of exhaustion,

His breathing labored from

years of smoking, he orders

the group to make camp

UZBEKISTAN

istkent

Tho next day a safety line

helps the men ford a

utary. "With 100 pounds on

your back, you don't want

to fall,” said photographer

Dugald Bremner.

ranite pir

the Tran Shan range, rising

above the Oygaing River to

14,700 feet. With many rap-

ids rated Class VI in the Rus:

sian system, the Oygaing is

runnable only by tl

skilled rafters. Flo’

miles west from

ing 50

ters,

it joins ather rivers

to empty into the Aral Sea

the team avoided carry ide, met the team at the

ing trees for raft frame Zhai Kazakhstan, a

me

Sergel’s bushy red beard and while the rooster

Nicknamed Boroda, ¢ Kyrgyzstan a half how

17" Sergel was the ater, our driver, Misha, gearex

group's philosephe nwa for the climb into th

inp N0 feet

in Russia

{our enormous pac

Forget it” the men said.

We're not interested:

We can pay y

Ise

and trent wa

The sto n

with a vengeam ic

dd to.cache the tt

und return for it the r

n

rough ste

vn h great stren 1

always hear about Fi

Iy'S A SIBERIAN SUPERPUMP.”

says Sergei Ushakov (lelt)

of the “dry bag” the team

used to trap airto fi

bublik, At the river the two

inflatables—canvas-covered

bladders—are carefully

lashed to a birch frame (top

left). Once launched, the

bublik glides easily over

boulders (right). “It's ike an

ter," says

army tank for w

interpreter George Aukon

It goes everywhere

comes the action, then later

the thinking

Unable te se

ins

20 yards

hat had become a bliz

nuacked just

zard, We

below the pass. The Russians,

packed like puppies in their

leaky tents, passed a cold, wet

night but powered on all the

next day to the O

There we hunl

listening to sleet crackle on

cred dow

the tent canopies or huddling

ound the campfire in

steam

ca or smoking harsh

1 cigarettes.

moming

sun apr ling our

campsite to be a lovely spor

Wild roses with plump red

hips greweverywhere, and

the birch and sumite were

turning fall colors, The roa

ing turquoise river tumble

through a valley littered with

colossal boulders that had

hurtled down from the Tian

Shan’

I

of morning the Russians

emerged from their tents

for calisthenies, While Sergei

performed stretching exer

cises, Dima and the two

Andreis cranked out 35

e

boulders overhe

crumbling peaks

the bright, warm air

ups each and pressed

Land

behind their necks,

When Yuri and his fir

young disciples took off to

retrieve the cached gear

Andrei Izhitsky, nursing 3

sore knee, stayed behind with

D

stipervise construction of the

raft frames. He'd built his first

raft at age 13 {or his schoo!

Id, George, and me to

outdoor club. Under the

Soviet system most schools

had a club, and so did fac

tories and municipalities.

Late the following day—

40

Buckine like white-water

wranglers, two raftsmen

fight the current astride

the twin pontoons of a cata-

raft. Highly maneuverable,

it corners quickly around

tight turns, but deep holes

at the bottom of a drop

can spell danger. Nose-

diving into the river, it can

buckle and flip, leaving

paddfers flailing.

with the team reassemble

the frames built, pontoons

inflated, snd the last toast

raised to success—we turned

in, ready’ to f

JonwaRr!” George bark

relow

at the first rapid

the put-in, "Now beck!

BECK!!”" The flotilla

was at last under way, six days

after leaving Taraz. Following

Ge

rge's staccato orders, I

backpaddled furiously. Our

cataraft tumed nimbly

if boulders

through a pair

and skirted the

standing wave below. Mean

while, the bublik barged right

through on our tail, iis mon

strous pontoons looking Indi

crously outsized in the

shallow water. Still, the big

midstre

doughnuts allowed Dima

ov to slide

that we hi

Je through

vy swinging left

and Andrei fv

wer bouled to

tight passages

or right—or turning around

entirely, It made no difference

which end went

Now that

first

i seemed tc

s by the fire ome

old me he'd ran

toughest rivers in Siberia

but was proudest of his lead

ership awards, one of which

was for the 1991 Bashkaus

River Expedition. "We ran

NATIONAL

cone waterfall in «

that no

before,” he recalled, deserity

ing every inch

Did the rapid b.

came as

bly explained what [ took foi

retelling the story trigge

hiss

IGRARHIC, Nt

bublik

ne had completed

Fit in de

ca name?

Dhd-ada,

he stuttered. “It

is-called Vladimir's Heart,” He

fell silent. Then,

said

anding, he

There is work to be

and «trode away

Yuri’s speech impediment

surprise. IF proba-

stony silences, But why had

nmr? George filled

me in, The rapid was named

for Viadimir Cherepanoy,

Yuri’s paddling pariner on

2 1990 Bashkaus expedition.

The twa had

tempted the

1997

it somet ad

wrong. Their cataraft over

turned below the falls, Yur

had survived; his close friend

had drowned. Other nen

might have hung up theit

it the sport

After two.days on

we feed the first

fang of black ro

ten feet tall jutting up i

hannels. One

dover a low

er fur

neled into a right

bounded by a cliff. Immedi

ately below the obstruct

the river k

Yuri imp

sharp lef

ently rast the

with Andrei Izhitsky

without annow

Jeparture—and j

dup

The

bellowed at uis to huery up.

Our cataraft bucked like

run. 1

ther, r

overboard

forced left

Hoo, boy,’ George

ng around the by

HECKPEDL

id. [twas too

iemy help we

still deliberat

ul the satest line. Yur

ahead of us, out of sight and

of no help.

In dlesp

te

mation, Ere

toon, and the

we att Che reo

ays

inched

popped out of the chan

only to be smashed side

6a flat-faced boulder a

eft

1 the beat

apex of the ri

nA loose

ine, atid we swirled free

Baad

Ue

eet ke ed

Dee ne rd

CRE Le td

run, Yuri Snegir and Andrei

Co)

fate when their eataraft

flipped over, trapping them

Cea

Ce Me ed

Oe aa

Ce te

CAMARADERIE AND A

glow at river's edge. As the

team sottles in for the night,

Dima Skubach tunes his gui

d sings an old rafters”

song: “if some tragedy befalls

us... Lwill not think of any:

thing but my friend. My soul

my hand, and my heart | will

give to him.

that, Even Yuri agreed. T nto F

Photographer

gird

Dag

PURE

Cee ek

eee cy

Ce ener)

De

Cee eon

Cy

approved, the world-class

Leet ROU)

Dee tee td

Seat)

1 § Co ay

asty farewell ee t surels but Dd

y s Ca cd

Ce Ta ccs

Cee kd

shooting rapids. He never

Cc

Ceo

Bu

Leal he)

Dee nhs

eee ted

Quandary

By IAN DARRAGH.

Photographs by MAGGIE STEBER

FALS OF LAUGHTER filled the room.

Louis Wauthier, our caller, was slip

ping his own risqué variations into

the comtredanse we were performing,

at the folk evening in Chicoutimi, Quebee: As

in square dancing, in the contredanse, which

originated in [th-century France.you'resup-

posed fo unquestioningly obey the caller's

commands, But Wauthier, who was wearing

the brightly colored sash of the voyageurs—the

early French explorers of Quelec—was push

ing the limits. We had started by forming into

Jong, parallel lines. After swinging our partners

andl promenading up the midelle, we complet-

ed a series of intricate figures at-an increasingly

frantic pace, Now Wauthier was ordering usta

stand das d dos (hack-to-back), urging us to

move closer until we were touching. After an

initial gasp of surprise. everyone complicd,

and | found myself detriere to derriere with an

attractive grandmother in a flowing dress out

of the 18905, with plumed feathers in her hat.

Suddenly my partner gave me a sharp push

with her backside, sending me sprawling

across the floor. She had tinderstood the

caller's command in French a split second

before me and had obeyed all too enthusiast

cally. As:the fiddle and accordion players ted

uson with their fast-paced jig; | picked myself

up off the floor, mowed down the fine, and,

with some relicf, changed partners,

‘This was Chicoutimi's winter carnival, a

yearly celebration of Quebecois culture, and

although it was past ten o'clock, kids as young

as six and grandmothers in their seventies

were steppirig and swinging with unflagging

energy to dances such as Loiseau dans la cage

and Le p'tit train de Jonqinére, At the begin~

ning of the evening's festivities we had been

divided into three teams. Fach was given a

family fame common in the region —Trem

hlay, Bouchard, or Simard—connecting us

Jan DAWMAH, | native of Montreal. was editor of

‘Cariaidicr Cengripsliie magazine tein 2989 to 1995,

‘This is his first story far Narieneat: Grotaarane

Teaaa-born pholageapher Macusta Steen now lives

in New York City. Her average of the Chermkee

agspeured int the May 1995 isstic

at

to the first French settlers in 1838, Between,

dances we had Competed in Jog sawing and.

other contests, with much cheering and good-

natured rivalry. ASI looked around at the

laughing, sweaty faves, [ thought: This could

only happen in Quebec.

‘Largest of Canada’s ten provinces, Quebec

is the only predominantly French-speaking

political entity in North America aside from

the islands of St.-ficrre and Miquelon in the

mouth of the Gulf of St. Lawrence—tiny ves-

tiges of France's New World empire. In recent

years the province has been the focuy of the

nation’s worst unity crisis since its birth in

1867. [0 av referendum held in October 1995,

‘Quebecers voted by a mere one percentage

point to stay within Canada, but a majority

‘of French speakers—60 percent—yoted for

independence.

‘That the Canadian federation has survived

this long has te do with various compromises

made on behall of Quebec. The province

s own distinct legal system and has

been given special powers over immigration,

enabling it to attract French-speaking new-

comers. I thé past 20 years, however, these

compromises have worn thin, and constites

tional amendments to patch things up have

failed to win approval, Canada has came to

resemble a bickering family, with one member

periodically threatening to pack up and leave,

“We are on the edge of a precipice," Bernard

Morin, an engineer from Jonquiere tald me.

What he meant was that if Quebec leaves the

federation, the Atlantic provinees will have no

land link te the rest of Canada. Prosperous

British Columbia—with its thriving trade

with the Pacific Rim—tight also secede, and

the entire nation could become unglued.

To federalists the prospect of another Que.

hee referendum on independence isa sword

af Damocles hanging over the province—and

Canada—creating unbearable uncertainty

that has stifled investment, But suvercigntists:

see referendums as the ultimate instrument of

democracy. Lucien Bouchard, Quebec's pre

ict, has wowed to hold another referendum

shortly after the next provincial el

lection (in

Cy NOV EMIER

NATIONAL GEOGRA

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- İrem Yayıncılık Passagework YDS Ön Hazırlık Seviye 1, 2, 3Document760 pagesİrem Yayıncılık Passagework YDS Ön Hazırlık Seviye 1, 2, 3renaivaa88No ratings yet

- National Geographic 1998Document196 pagesNational Geographic 1998renaivaa88No ratings yet

- National Geographic 1998Document196 pagesNational Geographic 1998renaivaa88No ratings yet

- The Asian Economic Community Is ComingDocument4 pagesThe Asian Economic Community Is Comingrenaivaa88No ratings yet

- National Geographic 1998Document172 pagesNational Geographic 1998renaivaa88No ratings yet

- National Geographic 1997Document234 pagesNational Geographic 1997renaivaa88No ratings yet

- Production of Biofuels Set To RiseDocument14 pagesProduction of Biofuels Set To Riserenaivaa88No ratings yet

- Moscow Is The World's Costliest CityDocument16 pagesMoscow Is The World's Costliest Cityrenaivaa88No ratings yet

- Russian Buys World's Priciest HomeDocument14 pagesRussian Buys World's Priciest Homerenaivaa88No ratings yet

- Relative ClausesDocument14 pagesRelative Clausesrenaivaa88No ratings yet

- Japanese Women To Have More EqualityDocument11 pagesJapanese Women To Have More Equalityrenaivaa88No ratings yet

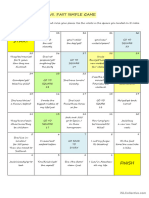

- Present Perfect vs. Past Simple GameDocument1 pagePresent Perfect vs. Past Simple Gamerenaivaa88No ratings yet

- The Verb To Be Ingilizce Be Olmak Fiili Kullanimi Ornek Cumleler 225Document31 pagesThe Verb To Be Ingilizce Be Olmak Fiili Kullanimi Ornek Cumleler 225renaivaa88No ratings yet