Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Granic 2014 - An Immigrant's Arrival To Copper Country, Michigan

Granic 2014 - An Immigrant's Arrival To Copper Country, Michigan

Uploaded by

LaszloCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- New World Coming: The 1920s and the Making of Modern AmericaFrom EverandNew World Coming: The 1920s and the Making of Modern AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Czech and Slovak Immigration to America: When, Where, Why and HowFrom EverandCzech and Slovak Immigration to America: When, Where, Why and HowNo ratings yet

- The Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold WarFrom EverandThe Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold WarNo ratings yet

- Scientology: Integrity and HonestyDocument41 pagesScientology: Integrity and HonestyOfficial Church of Scientology86% (7)

- Hyper-Grace - The Doctrine of The DevilDocument47 pagesHyper-Grace - The Doctrine of The DevilTiwaladeIfeoluwaOmotosho75% (4)

- Ties of Affection: Family Narratives in The History of Italian MigrationDocument18 pagesTies of Affection: Family Narratives in The History of Italian MigrationDaniela AnandaNo ratings yet

- The History of Italian American History - The Migration To Lancaster County and The Implications of The Intelligence Community by The Advanced Media Group, September 24, 2016©Document251 pagesThe History of Italian American History - The Migration To Lancaster County and The Implications of The Intelligence Community by The Advanced Media Group, September 24, 2016©Stan J. CaterboneNo ratings yet

- Immigrant Letters From IndianaDocument20 pagesImmigrant Letters From IndianaLaszloNo ratings yet

- Dixie & the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the UnionFrom EverandDixie & the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the UnionNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary Staten Island: From Colonial Calamities to Reluctant RebelsFrom EverandRevolutionary Staten Island: From Colonial Calamities to Reluctant RebelsNo ratings yet

- The Golden DoorDocument4 pagesThe Golden DoorloganzxNo ratings yet

- German Chicago: The Danube Swabians and the American Aid SocietiesFrom EverandGerman Chicago: The Danube Swabians and the American Aid SocietiesNo ratings yet

- Ivo Banac - Emperor Has Become A Komadij LITDocument23 pagesIvo Banac - Emperor Has Become A Komadij LITAndreas Bavngaard BakNo ratings yet

- Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New LondonFrom EverandHomegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New LondonNo ratings yet

- The Early Day of Rock Island and Davenport: The Narratives of J. W. Spencer and J. M. D. BurrowsFrom EverandThe Early Day of Rock Island and Davenport: The Narratives of J. W. Spencer and J. M. D. BurrowsNo ratings yet

- Debate Video SubtitleDocument13 pagesDebate Video SubtitleTham NguyenNo ratings yet

- PDF The Brink of Freedom Improvising Life in The Nineteenth Century Atlantic World David Kazanjian Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF The Brink of Freedom Improvising Life in The Nineteenth Century Atlantic World David Kazanjian Ebook Full Chaptersusan.phagan956100% (1)

- Long Branch in the Golden Age: Tales of Fascinating and Famous PeopleFrom EverandLong Branch in the Golden Age: Tales of Fascinating and Famous PeopleNo ratings yet

- NAS Boca Chica HistoryDocument16 pagesNAS Boca Chica HistoryCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Peoples of the Inland Sea: Native Americans and Newcomers in the Great Lakes Region, 1600–1870From EverandPeoples of the Inland Sea: Native Americans and Newcomers in the Great Lakes Region, 1600–1870No ratings yet

- The Palatine Wreck: The Legend of the New England Ghost ShipFrom EverandThe Palatine Wreck: The Legend of the New England Ghost ShipNo ratings yet

- Shadow Soldiers of the American Revolution: Loyalist Tales from New York to CanadaFrom EverandShadow Soldiers of the American Revolution: Loyalist Tales from New York to CanadaNo ratings yet

- Frank R Stockton - The Great War Syndicate: 'This proposition was an astounding one''From EverandFrank R Stockton - The Great War Syndicate: 'This proposition was an astounding one''No ratings yet

- Symphony For The City of The Dead Dmitri Shostakovich and The Siege of LeningradDocument464 pagesSymphony For The City of The Dead Dmitri Shostakovich and The Siege of LeningradJames GunnlaugssonNo ratings yet

- The Assaults On Stan J. Caterbone's Family Began On November 12, 1904 - According To The LNP New Era of The Same Date - YOU ARE FUCKED!Document233 pagesThe Assaults On Stan J. Caterbone's Family Began On November 12, 1904 - According To The LNP New Era of The Same Date - YOU ARE FUCKED!Stan J. CaterboneNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Early American LiteratureDocument8 pagesThesis On Early American Literaturenatashajohnsonmanchester100% (2)

- ColoniesDocument26 pagesColoniesrich_texter0% (1)

- The Beginnings of America (1607-1763)From EverandThe Beginnings of America (1607-1763)James Leslie WoodressNo ratings yet

- Great Cities of the United States - Historical, Descriptive, Commercial, IndustrialFrom EverandGreat Cities of the United States - Historical, Descriptive, Commercial, IndustrialNo ratings yet

- Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 Revised EditionFrom EverandStrangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 Revised EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Malice Toward None: Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, the Homestead Act, and the Massacre --and Heartening Survival--of the KochendorfersFrom EverandMalice Toward None: Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, the Homestead Act, and the Massacre --and Heartening Survival--of the KochendorfersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast, 1775–1783From EverandPrivateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast, 1775–1783No ratings yet

- Handbook of the United States of America, 1880: A Guide to EmigrationFrom EverandHandbook of the United States of America, 1880: A Guide to EmigrationNo ratings yet

- Wreck of the Faithful Steward on Delaware's False Cape, TheFrom EverandWreck of the Faithful Steward on Delaware's False Cape, TheNo ratings yet

- Along the Hudson and Mohawk: The 1790 Journey of Count Paolo AndreaniFrom EverandAlong the Hudson and Mohawk: The 1790 Journey of Count Paolo AndreaniCesare MarinoNo ratings yet

- Padhle 11th - Executive NotesDocument31 pagesPadhle 11th - Executive NotesTanistha khatriNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Literary Devices inDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Literary Devices inGeryll Mae SacabinNo ratings yet

- Smart Tab Android Users GuideDocument288 pagesSmart Tab Android Users Guidegautham2850% (2)

- Ey Philippines Tax Bulletin Mar 2015Document46 pagesEy Philippines Tax Bulletin Mar 2015Glen JavellanaNo ratings yet

- D92 PDFDocument8 pagesD92 PDFJuan Diego ArizabalNo ratings yet

- Apps LoggerDocument45 pagesApps LoggerMohammad ZaheerNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log 7Document4 pagesDaily Lesson Log 7SofiaNo ratings yet

- Depression in Young People and The ElderlyDocument28 pagesDepression in Young People and The ElderlyJennyMae Ladica QueruelaNo ratings yet

- 8816625Document44 pages8816625Tharangini GudlapuriNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam Answer KeyDocument5 pagesMidterm Exam Answer Keyjamaica faith ramonNo ratings yet

- Charlotte Lamb DesperationDocument163 pagesCharlotte Lamb DesperationHiermela Hagos68% (50)

- 1200 английских словDocument89 pages1200 английских словАнна ГореславскаяNo ratings yet

- Quiz 1 - Corporate Liquidation ReorganizationDocument4 pagesQuiz 1 - Corporate Liquidation ReorganizationJane GavinoNo ratings yet

- Choosing Brand Elements To Build Brand EquityDocument25 pagesChoosing Brand Elements To Build Brand Equityoureducation.in100% (2)

- Emma Wasserman. Paul Beyond The Judaism Hellenism DivideDocument26 pagesEmma Wasserman. Paul Beyond The Judaism Hellenism DividedioniseNo ratings yet

- When All They Had Was LoveDocument14 pagesWhen All They Had Was LoveRahul Pinnamaneni100% (1)

- Nursing Notes Outline: Note Taking TipsDocument2 pagesNursing Notes Outline: Note Taking TipsHAROLD ANGELESNo ratings yet

- Grammar-Inversion ExercisesDocument2 pagesGrammar-Inversion ExercisesGeorgiaNo ratings yet

- Sumative Test (4TH Quarter) Science 8Document4 pagesSumative Test (4TH Quarter) Science 8Jonel Rule100% (2)

- ASSIGMENT 2 ScribDocument14 pagesASSIGMENT 2 Scribruslanaziz100% (1)

- Apa Research Paper SectionsDocument4 pagesApa Research Paper Sectionsfvgj0kvd100% (1)

- Visual FieldsDocument15 pagesVisual FieldsSaraNo ratings yet

- Dictionary Michel FoucaultDocument10 pagesDictionary Michel Foucaultsorin2013No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Pavement Roughness Using An Andriod Based SmartphoneDocument9 pagesEvaluation of Pavement Roughness Using An Andriod Based SmartphoneAshish WaliaNo ratings yet

- How To Pass MRCP Part 1 (Complete Guidelines) - Passing MRCP Part 1Document1 pageHow To Pass MRCP Part 1 (Complete Guidelines) - Passing MRCP Part 1Kendra GreyNo ratings yet

- Detached RetinaDocument1 pageDetached RetinamountainlordNo ratings yet

- Ted LevittDocument2 pagesTed Levittnantha74No ratings yet

- Problem Set Scenario - Answer Analysis Exercise 5%Document8 pagesProblem Set Scenario - Answer Analysis Exercise 5%dea.shafa29No ratings yet

Granic 2014 - An Immigrant's Arrival To Copper Country, Michigan

Granic 2014 - An Immigrant's Arrival To Copper Country, Michigan

Uploaded by

LaszloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Granic 2014 - An Immigrant's Arrival To Copper Country, Michigan

Granic 2014 - An Immigrant's Arrival To Copper Country, Michigan

Uploaded by

LaszloCopyright:

Available Formats

An Immigrant's Arrival to Copper Country, Michigan: The 1912 Reminiscences of Petar

Stanković

Author(s): Translated and Edited by Stan Granic

Source: Michigan Historical Review , Vol. 40, No. 2 (Fall 2014), pp. 101-113

Published by: Central Michigan University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5342/michhistrevi.40.2.0101

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Central Michigan University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Michigan Historical Review

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country,

Michigan: The 1912 Reminiscences of Petar

Stanković

Translated and Edited by

Stan Granic

An estimated thirty-three million European immigrants chose the United States

as their destination between 1821 and 1924. Beginning in the mid-1880s, the

number of immigrants arriving from Southern and Eastern Europe began to overtake

those arriving from Northern and Western Europe. In 1912, sixteen-year-old Petar

Stanković, from Brinje, Lika region, Croatia, was one of them. Borrowing money for

the passage to the promised land, he began his new life in America by working in a

copper mine near Calumet, Michigan.

In the reminiscences that follow, Stanković describes his optimism for a better

future in America as he made his steamship passage across the Atlantic with his

fellow countrymen. This optimism would be somewhat dampened both by his

experiences in third class and by the treatment of immigrants at Ellis Island.

Although he did not have immediate family members waiting for him, news had

filtered back to his native village about the Croatian community in Copper Country

as this chain migration spread throughout the villages of the Old Country.

The success of the copper mining industry in Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula

during the late 1800s and early 1900s attracted unskilled Croatian, Finnish,

Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Slovenian, and other immigrant laborers looking for a

better life. Many of these, like Stanković, frequently took work in the mines as

trammers. Often regarded as little more than human beasts of burden, the trammers’

job was to muck out the blasted rock, place it into their tram cars, and then push

their loads to the shaft. By working as a trammer, Stanković quickly came to

understand that unskilled immigrants had the low-end jobs. But, as he had borrowed

the money for his overseas voyage, he had no choice other than to stay and stick it out.

Like most South Slavic peasant immigrants, he left behind the small family

plots in his village only to be thrown into a completely unfamiliar setting. Though

language barriers in the mines made the transition much more difficult, the presence of

other experienced Slavic miners helped him adjust to his new work and surroundings.

These immigrant miners, usually single, often lived in boarding houses operated by

their fellow countrymen and their spouses. Here, with other immigrant laborers of the

The Michigan Historical Review 40:2 (Fall 2014): 101-113

©2014 Central Michigan University. ISSN 0890-1686

All Rights Reserved

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

102 The Michigan Historical Review

same ethnic origin, they found a social support structure that helped them adapt to

their new and unfamiliar surroundings.

Stanković started writing his reports while he was still in Calumet and they

appeared in the lively Croatian press active in the United States at the time. In the

aftermath of the violent and bitter strike of 1913–1914, many miners left Copper

Country; Stanković was one of them. He departed Calumet for Tonopah, Nevada,

and found work as a gold miner before traveling on to San Francisco, Los Angeles,

and Arizona. He then settled in Chicago in 1917. Following his stay in Chicago,

and then Pittsburgh, he returned to Croatia in 1925 and worked as a journalist.

There he began laying plans to immigrate to Canada and launch a newspaper that

would serve Croatian migrant laborers, as many were increasingly choosing Canada

as their preferred destination after the United States tightened its immigration quota

in 1921 and again in 1924. In 1928 he led a group of Croatian and South Slavic

laborers to Canada under the immigration and colonization scheme of the Canadian

Pacific Railway. The following year he launched the weekly “Kanadski glas”

(“Canadian Voice”) in Winnipeg, Manitoba, renaming it “Hrvatski glas”

(“Croatian Voice”) in 1933.1

Departure for America

It was during the stormy period of the Balkan War [of 1912] and

accompanying assassinations that I succeeded in crossing the border of

the former Austro-Hungarian Empire unnoticed.2 I laughed with delight

1 These reminiscences first appeared in the 1927 Christmas issue of Narodni val

(Zagreb) and were reprinted under the title “Pod zemljom: do novog svijeta – rad u

rudnicima – prvi Božić u Ameriku” (“Underground: To the New World, Work in the

Mines, First Christmas in America”), in Kalendar Hrvatski glas: za prestupnu godinu 1952, ed.

Petar Stanković (Winnipeg: Hrvatski glas, 1951), 110-114. The introduction, notes in

squared brackets in the main body of the translation, and footnotes were provided by

the translator. Stanković contributed to several Croatian language newspapers in the

United States under his name or various pseudonyms including: New York’s Hrvatski

svijet (Croatian World) and Novi Hrvat (New Croat), Chicago’s Novi svijet (New World), and

Pittsburgh’s Zajedničar (The Fraternalist). In 1919 he sided with the progressive

educationalists gathered around Chicago’s Znanje (Knowledge) and in 1922 he became

assistant editor and manager of Pittsburgh’s Neutralna seljačka republika Hrvatska (The

Neutral Croatian Peasant Republic). In Pittsburgh he attended night school classes during

the early 1920s and, following his return to Croatia in 1925, he served on the editorial

board of Narodni val (National Wave) and was later appointed to the Association of

Croatian Emigration Organizations in Zagreb. For more on Stanković’s life and his

editing and publishing of Hrvatski glas see Steve Melnyk, “Paper Marks Anniversary,” The

Winnipeg Tribune, April 4, 1959, 10; John Badovinac, “A Croatian Weekly Newspaper

Celebrates an Anniversary,” Zajedničar (Pittsburgh), March 13, 1974, 2.

2 The first Balkan War of 1912 pitted an alliance comprising Bulgaria, Greece,

Serbia, and Montenegro against the Ottoman Empire. Members of the Balkan alliance

desired to expand their territories and liberate their kinsman from the declining Ottoman

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country 103

as I stepped onto free Swiss territory and turned toward Austria,

exclaiming to myself, “I’m finally rid of you, you monstrosity!”

An old French steamship filled its ungainly and ugly entrails with

several hundred of us new citizen candidates for America and the New

World.

The ocean was choppy. Waves the size of hills smashed up against

our feeble ship which despite its age held its own and repelled them

away. Probably from anger for not being able to injure the ship, the

broken waves would return again and again to attack our ship with ever

greater fury and new allies from all sides. At times it looked as though

they were not ocean waves, but a vast milky froth.

The old captain in charge of our steamship from the time of its

maiden voyage was known to stroll along the deck with a wide grin on

his face while the ship was being smashed by the largest of waves. He

was no doubt laughing within himself as the enraged waves attacked

hundreds of times at the veteran vessel to no avail, for the ship had

broken through countless waves over the years.

Those of us in third class slept in linen beds suspended from the

ceiling. And believe me we did not feel well in them at all. In a short

time we all felt as though our insides were in rebellion, our heads heavy

and our sight cloudy. We quickly ran up deck to inhale fresh air in an

effort to save ourselves from the catastrophe. But it came nonetheless.

. . . We must have appeared like sickly sheep to the beautiful blonde

girl from our coastal region who watched us from above, from second

class, as we fed the fish below with the expensive meals we ate and

which our unfortunate stomachs could no longer tolerate.

“Is she laughing at us,” I thought to myself as I looked up. “But no,

she couldn’t be so wicked.” I again cast a glance up to see if my

impression was correct. As we caught each other’s eyes, she smiled as

she chewed on something. Beside her stood an older man dressed in

American style common to the time. I later learned he was her uncle and

was returning to America, somewhere in Colorado where he owned a

tavern. She was accompanying him. This was a very pleasant experience

for her and she delighted in the thought of being able to see America.

Empire. On October 8, 1912, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire and its

allies soon joined the conflict. The major European powers compelled the sides to end

the conflict and the Treaty of London was signed in December 1912 with Turkey

providing territorial concessions to the Balkan allies.

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

104 The Michigan Historical Review

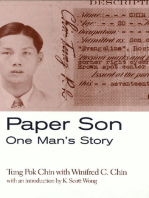

Immigrant miner Petar Stanković in Calumet, Michigan

(circa 1913)

Source: Personal collection of Helene Royes, daughter of Petar Stanković

When her uncle turned away, the blonde girl threw me a candy.

Despite all my clumsiness I somehow caught it. I nodded in thanks as

she continued to laugh. After that I was always on deck looking up to

second class. . . .

The closer we came to New York, the better we all began to feel.

There were all kinds of nationalities on our ship, but mostly Italians and

Croats. On the day we arrived in America, those who were sick had

already recuperated and everyone by this time had begun to make

preparations for disembarking. We were singing and cracking jokes, and

were overcome with joy.

Around four in the afternoon we caught a glimpse of New York. I

had the impression that we came to a place that was made by some

greater force and not by human hands. On this clear day, the massive

high-rise buildings left an impression on me that they touched the very

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country 105

sky. From a distance we caught glimpse of the Statue of Liberty with its

hand stretched overhead pointing up into the distance and drawing our

attention to the “quarantine” which Americans called Ellis Island. The

Statue of Liberty seemed powerful and proud.

When we reached the dock, the first and second class passengers

were the first to disembark. They did not even have to stop by Ellis

Island since those who had money to pay for more expensive tickets for

the passage were considered impeccable and “clean”―they were free to

immigrate to the country. That is when I learned what it meant to be in

third class. . . .

Finally America! That same evening I took the train towards the

Canadian border. Riding through Canadian territory, I arrived on my

third day to the town of Calumet in northern Michigan. Calumet and

surrounding areas were then known for their massive copper mines.3

Work in the Mines

In Calumet I found many acquaintances and neighbors [from back

home].4 They assisted me in finding lodgings and food at a boarding

house. Providing accommodations and meals, the boarding house was

operated by one of my fellow villagers. He worked in the mine and his

industrious wife undertook all the work around the cooking, cleaning

and even the laundry.

I was in a hurry to find work. This was not easy. Many people were

unemployed at the time and would gather every day in front of a

different mine. One morning I too went among this group of workers

who every morning made the rounds from mine to mine to try their

luck.

3 For the mining, economic, social, community, and landscape history of

Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula see Larry Lankton, Hallowed Ground: Copper Mining and

Community Building on Lake Superior, 1840s–1990s (Detroit: Wayne State University Press,

2010); Arthur W. Thurner, Strangers and Sojourners: A History of Michigan’s Keweenaw

Peninsula (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994); Larry Lankton, Cradle to Grave:

Life, Work, and Death at the Lake Superior Copper Mines (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1991).

4 When Stanković arrived the population of the Croatian community in Calumet

and surrounding region was estimated at 10,000. George J. Prpic, The Croatian Immigrants

in America (New York: Philosophical Library, 1971), 121. For more on the community in

the region see Keweenaw Ethnic Groups: The Croatians (Houghton, MI: MTU Archives and

Copper Country Historical Collections, J. Robert Van Pelt Library, Michigan

Technological University, 2004-07), www.ethnicity.lib.mtu.edu/groups_croatians.html;

Daniel Cetinich, South Slavs in Michigan (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University

Press, 2003).

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

106 The Michigan Historical Review

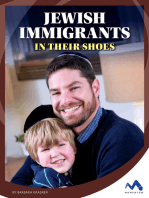

Painesdale, Michigan, miners pose for a photograph

(January 1912)

Source: Copper Range Company Photograph Collection, Michigan Technological University

Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections

The first day the manager of the mine did not notice me. He

probably did not look at the others either. He just waved his hand from

behind the window [of the office] and said that they did not need

workers that day. The same happened the second day.

On the third day I arrived a little earlier and only ten candidates for

work were in front of me, while maybe a hundred were behind me. As

soon as the manager opened the door to the office you could see right

away that this day he might hire someone. First he thoroughly cleaned

his glasses and then looked over all the candidates. Suddenly he pointed

his finger at a middle-aged Slovenian who was in front of me and

behind whom I was barely visible since he was so tall and strong. The

supervisor called this worker up and told him to report for work

tomorrow.

The manager again placed his glasses on and scanned across the

entire crowd. I looked directly into his eyes. When he noticed me he

immediately pointed at me. However, some others responded as they

thought that they were chosen.

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country 107

“Not you, but the youngster next to you!” he said.

I guess the manager wanted me. With a sense of fear and

apprehension I walked up to the supervisor.

“What’s your name?” he asked me.

I began to mumble something in Croatian. . . .

“Oh yes!” he interrupted me, “you’re a green foreigner.”

And then he began to explain to me through gestures that I could

come tomorrow to work. Since I could not understand him, he called

over a Polish clerk from the office who explained to me in Polish what

the supervisor wanted.

There was a certain look of scorn on the face of the supervisor. His

nose was red and his eyes were murky. He handed me a form which I

had to fill out.

“Tomorrow, tomorrow, boy!” he said to me at the end of the

conversation.

And this meant that tomorrow at the crack of dawn, at six o’clock, I

had to be at the entrance to the mine where together with the other

miners I would be lowered for the first time into the bowels of the

earth.

“You’re strong boy!” were the last words that the supervisor who

was of English or Welsh origin said to me.

Just before saying these words he clutched my right arm and

grinned from ear to ear as he was likely pleased with the muscles of a

sixteen-year-old youngster. And muscle is what he was looking for and

nothing more! I had that in abundance and we easily came to an

agreement. . . .

That day the supervisor hired only the two of us. Many were

envious of me for my good fortune that ensued so quickly. I too was

surprised that he picked me while passing over other experienced

miners. Later it became clear why he wanted me. He wanted me because

he saw in me an untapped reservoir of strength, of youthful strength,

that needed to be taken advantage of―to squeeze it out of me like a

lemon. That was the way it was for others as well.

The following day I arrived before the mine and when the time

came we sat in a cage and in a second we began the descent at a great

speed right into the earth. Our cage was held by a thick cable braided

from metal wire. A strange odor and a warm steam sprang from the

bottom of the mine up towards the top. In a few minutes we reached

our destination.

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

108 The Michigan Historical Review

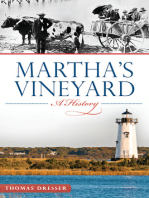

The house in Seeberville, near Painesdale, where deputies killed

two immigrant Croatian miners and wounded two others on August

14, 1913, during the Copper Country strike. A typical boarding house

of the era, it was run by Croatian immigrants Joseph and Antonia

Putrich, who lived there with their four children, a hired girl, and

ten male boarders.

Source: Hanchette & Lawton Case Files on the Copper Miners’ Strike, Michigan Technological

University Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections

I was partnered up with the same Slovenian fellow who was hired

with me the day before. I was pleased. At least with him I could chat

and ask for advice because a rookie miner needed lots of advice.

Off we went to the place where the ore was loaded up. It was a

heavy copper ore. We pushed the empty tram car ahead of us.

“Here we are,” said my partner as we arrived at the location where

thanks to blasting charges and other workers, a large pile of ore had

been pulverized into smaller and larger pieces.

The two of us had to load up twelve tram cars daily. While loading

up the second wagon I was already completely soaked in sweat from the

work and great heat that ruled in the depths of Mother Earth. I had

heavy shoes on my feet, some kind of a helmet with an attached

acetylene lamp on my head and only on my lower body did I change

into work pants, while I went without clothing on my upper torso. Usually

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country 109

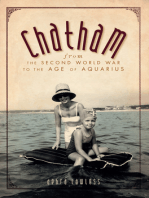

A shirtless trammer pushing his heavy load of copper ore at a

Calumet and Hecla mine (c. 1900–1913)

Source: Mining Engineering Photographic Collection, Michigan Technological University Archives

and Copper Country Historical Collections

I would throw away my shirt while loading the ore and only when I had

to push the tram car toward the surface where the minerals were

removed would I place it beneath my right shoulder to cushion it as I

pressed up against my corner of the wagon.

Every so often my Slovenian partner would remind me by saying:

“Come on boy, come on, push!” This was especially the case whenever

the tram car would come to a halt on an incline.

These were the awful days of my youth! It was a true hell. That first

day a stream of sweat poured from me and I drank more than ten litres

of water. I often even had to remove my shoes to empty the sweat. With

the greatest of effort I nevertheless succeeded in surviving the entire day

which was rarely the case for rookies. Usually rookie miners lasted only

a couple of hours and then asked to be taken above ground. By evening

I could barely stand on my feet and of the food that the boarding house

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

110 The Michigan Historical Review

lady had prepared for me, I was only able to eat an apple and drink

some tea.

When I returned home that evening, everyone marvelled at my

having been able to last the whole day. I ate very little and immediately

went to bed and fell asleep as if someone had hit me over the head. I did

not turn once during the entire night.

And that is how little by little I adapted to the extremely hard and

awfully dangerous work in the copper mines. I worked twelve hour days;

one week on day shift and one week on night shift.5

Had I had the money for a return ticket, I would not have remained

long in America. However, not only did I not have any money for a

return ticket, I owed money which I borrowed for the trip to America.

Therefore, there was nothing to do but to endure and go on. That is

right, I had to go on like a beast of burden. The days went by slowly.

Nevertheless after about half a year I began to settle in. The hard

mining life became easier for me. My Slovenian co-worker no longer

had to remind me to push harder against my side of the tram car. I

acquired calluses the size of shoe soles and my right shoulder, with

which I pushed up against the wagon, hardened incredibly. Already then

I could speak a few dozen English words and phrases, but in all honesty

these were mostly the type of words found in the mine workers’

unwritten dictionary. . . .

Even the supervisor would often speak to me and every morning he

would typically say: “Good morning boy!”

“Good morning Mr. Captain!” would be my response.

When fall arrived, I purchased winter clothing, the first coat in my

entire life and a hat whose flaps would cover my ears and reach down to

the neck. This was because that part of America experienced cold

winters.

My friends and fellow boarders shaved off by force my adolescent

moustache which had just begun to grow. I would wear these wide pants

5 A US Senate report in the aftermath of the Michigan copper strike described the

“exhausting, muscle straining, back-breaking work” of trammers as “really work for

beasts of burden.” Workers loaded up blasted-out ore into heavy tram cars and used

their brute strength to push the loaded cars over rough tracks to shafts to be hauled to

the surface. Two trammers working together often pushed loads weighing between two

to four tons (4,800 to 8,000 pounds) over a distance of 1,000 to 1,500 feet a dozen times

each shift. “The Tramming Trouble,” in US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor

Statistics (Walter B. Palmer, John B. Densmore, John A. Moffit, and Royal Meeker),

Michigan Copper District Strike, Senate Document No. 381, Sixty-Third Congress, Second

Session (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1914), 26-28.

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country 111

The Croatian community’s St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic

Church of Calumet (formerly Red Jacket), established in 1901

Source: MTU Photographic Collection, Michigan Technological University Archives and Copper

Country Historical Collections

and shoes whose tips curled up toward the sky. In short, the more that

time went by, the more I adapted to life in the New World.

First Christmas in America

I had already spent eight months in America when Christmas

arrived. Much snow had fallen and it was extremely cold. I worked the

entire day on Christmas Eve and only on Christmas Day did we get a

holiday. Our hard-working landlady spent the entire week preparing for

the most important day in the year. The house was full of everything:

food, wine, beer, and spirits.

“Merry Christmas,” we all greeted each other on the day of Christ’s

birth.

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

112 The Michigan Historical Review

The entire town celebrated this major holiday. This was a Christian

town even though un-Christian and greedy capital had the main word

and was the deciding factor. . . .

In front of our Croatian Catholic church more people gathered than

was normally the case.6 The priest was in a good mood. Prior to mass he

greeted people left and right. During mass he completed his official

duties with more spirit than normal and held a very moving sermon on

the Son of Nazareth who was born into the world in order to lead

people on the right path and to free them of sin. People were throwing

handfuls of coins and paper dollars into the alms-box to better fulfill

their duties and the priest was most pleased with this.

Back at the boarding house everything was cheerful. After lunch a

guest and countryman came by with his accordion and a little later a few

young ladies, and then a group of several other young ladies

accompanied by three tamburitzans arrived.7 All of us were

6 In 1892 Croatian immigrants living in Calumet established Lodge 8 (St. John

Society) of the Slovenian Croatian Society, a mutual benefit organization that by 1900

had 531 members. This was followed in 1895 with the establishment of Lodge 48 (St.

Jerome Society) of the National Croatian Society and by 1903 there were two other such

lodges. At the close of the 1800s, Rev. Josip Polić arrived from Senj, Croatia, and began

holding religious services for Croats in the local Slovenian church. By 1900 an estimated

1,200 to 1,500 Croats lived in Calumet and the following year they were in a position to

establish their own church named after St. John the Baptist. In 1906 the Croatian-

Slovenian Political Club was established to help organize the community during

municipal elections. By 1907 the mutual benefit National Croatian Society boasted the

following lodges in Copper Country: St. Jerome Lodge 48 in Calumet, Vinodol Lodge

153 in Calumet, St. Joseph Lodge 192 in Trimountain, Sts. Peter and Paul Lodge 233 in

Atlantic, Our Lady of Trsat Lodge 236 in Calumet, Our Lady of Bistrica Lodge 252 in

Victoria, Holy Trinity Lodge 262 in Hancock, and St. Florian Lodge 285 in Calumet. A

Calumet-based newspaper called Rodoljub (Patriot) was launched in 1902 and existed

under that name to 1905, when it was subsequently renamed the following: Hrvatski

radnik (Croatian Worker) from 1905–1912, Hrvatska sloboda (Croatian Liberty) from 1912–

1915, and Hrvatska (Croatia) from 1915–1928. Prpic, The Croatian Immigrants, 207-208;

Juraj Škrivanić, Povijest američkih Hrvata (History of the American Croats), ed. Ivan Čizmić

(manuscript 1909–1916; pub. Zagreb: Hrvatski svjetski kongres, 2011), 165, 192, 238,

287, 354; “Adresar odsjeka N.H.Z.” (“Directory of National Croatian Society Lodges”),

Zajedničar 26 (February 1907): 18-26; Luka Štefanac, “Hrvati u državi Michigan” (“Croats

in the State of Michigan”), in Hrvatski list and Danica Hrvatska koledar: za prostu godinu

1938, ed. Ivan Krešić (New York: Hrvatski Publishing Co., 1937), 151-153.

7 The tamburitza (tamburica in Croatian) is a stringed instrument of various sizes

that evolved from a solo instrument to one that is often played in small groups of three

to four players and also in much larger orchestras. Local chapters of Croatian

benevolent, social, workers, cultural, and religious organizations in the US often

established affiliated tamburitza orchestras that performed at various community events.

Some groups, such as the Elias Tamburitza Serenaders from Wisconsin, travelled and

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

An Immigrant’s Arrival to Copper Country 113

acquaintances and friends. There were about twenty of us that gathered,

both male and female. We were from different regions of our Croatian

homeland. The host was a native of Lika and several of us were his

neighbors from back home. The landlady was born in Severin na Kupi.

There were also several people from Zagorje, Slavonia, one from

Dalmatia and two from Bosnia. Later on a neighbor who was a

Slovenian and my school chum, a Serb from Lika, also joined us.

The host watched over the table and made sure the glasses were full.

The hostess treated us with various pastries and fruits. There was

everything in abundance.

The tamburitzans who were from Gorski Kotar began to play and

sing and in a few moments the entire house shook from song and dance.

When the tamburtizans would stop the accordion would take over.

“Play the drmež,8 Janko!” yelled the Slavonian, who was well warmed

up by the wine and whose feet began bouncing. He wanted to show off

his artistry and it seemed mostly in an effort to woo the young ladies

who only a few months earlier had arrived from Delnica, doubtlessly

seeking marriage.

We drank, sang and danced in our home late into the night.

I retired to bed earlier than the others, but sleep did not come to me

for a long time. The memory of the previous Christmas I celebrated in

the homeland and in the company of my family came before my eyes. I

remembered Christmas Eve. I remembered the beautiful songs that the

youth sang throughout all the villages and in front of the church both

on Christmas Eve and on Christmas Day. I even recalled the powerful

[celebratory] gunfire volleys into the sky. . . .

I was so absorbed by all these thoughts and in a moment I began to

feel as if I was held in a prison, far from a truly joyous Christmas like the

ones I previously celebrated in my impoverished Lika. A feeling of

loneliness, a fear and a strange pain crept into my heart and tears began

to flow from my eyes. . . .

It was very late by the time I finally fell asleep.

performed throughout the United States and Canada as part of the Chautauqua circuit

during the 1920s and 1930s, and later during World War II at USO events. Richard

March, The Tamburitza Tradition: From the Balkans to the American Midwest (Madison, WI:

University of Wisconsin Press, 2012).

8 The drmež (shaking dance) is a dance step common to the Slavonian region of

Croatia and is performed to the accompaniment of the tamburitza. It is one of the

primary dance steps taught to members of the many Croatian folk dance ensembles

active across the United States and Canada.

This content downloaded from

31.46.253.21 on Tue, 24 Mar 2020 01:26:10 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- New World Coming: The 1920s and the Making of Modern AmericaFrom EverandNew World Coming: The 1920s and the Making of Modern AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Czech and Slovak Immigration to America: When, Where, Why and HowFrom EverandCzech and Slovak Immigration to America: When, Where, Why and HowNo ratings yet

- The Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold WarFrom EverandThe Diplomacy of Migration: Transnational Lives and the Making of U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold WarNo ratings yet

- Scientology: Integrity and HonestyDocument41 pagesScientology: Integrity and HonestyOfficial Church of Scientology86% (7)

- Hyper-Grace - The Doctrine of The DevilDocument47 pagesHyper-Grace - The Doctrine of The DevilTiwaladeIfeoluwaOmotosho75% (4)

- Ties of Affection: Family Narratives in The History of Italian MigrationDocument18 pagesTies of Affection: Family Narratives in The History of Italian MigrationDaniela AnandaNo ratings yet

- The History of Italian American History - The Migration To Lancaster County and The Implications of The Intelligence Community by The Advanced Media Group, September 24, 2016©Document251 pagesThe History of Italian American History - The Migration To Lancaster County and The Implications of The Intelligence Community by The Advanced Media Group, September 24, 2016©Stan J. CaterboneNo ratings yet

- Immigrant Letters From IndianaDocument20 pagesImmigrant Letters From IndianaLaszloNo ratings yet

- Dixie & the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the UnionFrom EverandDixie & the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the UnionNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary Staten Island: From Colonial Calamities to Reluctant RebelsFrom EverandRevolutionary Staten Island: From Colonial Calamities to Reluctant RebelsNo ratings yet

- The Golden DoorDocument4 pagesThe Golden DoorloganzxNo ratings yet

- German Chicago: The Danube Swabians and the American Aid SocietiesFrom EverandGerman Chicago: The Danube Swabians and the American Aid SocietiesNo ratings yet

- Ivo Banac - Emperor Has Become A Komadij LITDocument23 pagesIvo Banac - Emperor Has Become A Komadij LITAndreas Bavngaard BakNo ratings yet

- Homegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New LondonFrom EverandHomegrown Terror: Benedict Arnold and the Burning of New LondonNo ratings yet

- The Early Day of Rock Island and Davenport: The Narratives of J. W. Spencer and J. M. D. BurrowsFrom EverandThe Early Day of Rock Island and Davenport: The Narratives of J. W. Spencer and J. M. D. BurrowsNo ratings yet

- Debate Video SubtitleDocument13 pagesDebate Video SubtitleTham NguyenNo ratings yet

- PDF The Brink of Freedom Improvising Life in The Nineteenth Century Atlantic World David Kazanjian Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF The Brink of Freedom Improvising Life in The Nineteenth Century Atlantic World David Kazanjian Ebook Full Chaptersusan.phagan956100% (1)

- Long Branch in the Golden Age: Tales of Fascinating and Famous PeopleFrom EverandLong Branch in the Golden Age: Tales of Fascinating and Famous PeopleNo ratings yet

- NAS Boca Chica HistoryDocument16 pagesNAS Boca Chica HistoryCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Peoples of the Inland Sea: Native Americans and Newcomers in the Great Lakes Region, 1600–1870From EverandPeoples of the Inland Sea: Native Americans and Newcomers in the Great Lakes Region, 1600–1870No ratings yet

- The Palatine Wreck: The Legend of the New England Ghost ShipFrom EverandThe Palatine Wreck: The Legend of the New England Ghost ShipNo ratings yet

- Shadow Soldiers of the American Revolution: Loyalist Tales from New York to CanadaFrom EverandShadow Soldiers of the American Revolution: Loyalist Tales from New York to CanadaNo ratings yet

- Frank R Stockton - The Great War Syndicate: 'This proposition was an astounding one''From EverandFrank R Stockton - The Great War Syndicate: 'This proposition was an astounding one''No ratings yet

- Symphony For The City of The Dead Dmitri Shostakovich and The Siege of LeningradDocument464 pagesSymphony For The City of The Dead Dmitri Shostakovich and The Siege of LeningradJames GunnlaugssonNo ratings yet

- The Assaults On Stan J. Caterbone's Family Began On November 12, 1904 - According To The LNP New Era of The Same Date - YOU ARE FUCKED!Document233 pagesThe Assaults On Stan J. Caterbone's Family Began On November 12, 1904 - According To The LNP New Era of The Same Date - YOU ARE FUCKED!Stan J. CaterboneNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Early American LiteratureDocument8 pagesThesis On Early American Literaturenatashajohnsonmanchester100% (2)

- ColoniesDocument26 pagesColoniesrich_texter0% (1)

- The Beginnings of America (1607-1763)From EverandThe Beginnings of America (1607-1763)James Leslie WoodressNo ratings yet

- Great Cities of the United States - Historical, Descriptive, Commercial, IndustrialFrom EverandGreat Cities of the United States - Historical, Descriptive, Commercial, IndustrialNo ratings yet

- Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 Revised EditionFrom EverandStrangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-2006 Revised EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Malice Toward None: Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, the Homestead Act, and the Massacre --and Heartening Survival--of the KochendorfersFrom EverandMalice Toward None: Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War, the Homestead Act, and the Massacre --and Heartening Survival--of the KochendorfersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast, 1775–1783From EverandPrivateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast, 1775–1783No ratings yet

- Handbook of the United States of America, 1880: A Guide to EmigrationFrom EverandHandbook of the United States of America, 1880: A Guide to EmigrationNo ratings yet

- Wreck of the Faithful Steward on Delaware's False Cape, TheFrom EverandWreck of the Faithful Steward on Delaware's False Cape, TheNo ratings yet

- Along the Hudson and Mohawk: The 1790 Journey of Count Paolo AndreaniFrom EverandAlong the Hudson and Mohawk: The 1790 Journey of Count Paolo AndreaniCesare MarinoNo ratings yet

- Padhle 11th - Executive NotesDocument31 pagesPadhle 11th - Executive NotesTanistha khatriNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Literary Devices inDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Literary Devices inGeryll Mae SacabinNo ratings yet

- Smart Tab Android Users GuideDocument288 pagesSmart Tab Android Users Guidegautham2850% (2)

- Ey Philippines Tax Bulletin Mar 2015Document46 pagesEy Philippines Tax Bulletin Mar 2015Glen JavellanaNo ratings yet

- D92 PDFDocument8 pagesD92 PDFJuan Diego ArizabalNo ratings yet

- Apps LoggerDocument45 pagesApps LoggerMohammad ZaheerNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log 7Document4 pagesDaily Lesson Log 7SofiaNo ratings yet

- Depression in Young People and The ElderlyDocument28 pagesDepression in Young People and The ElderlyJennyMae Ladica QueruelaNo ratings yet

- 8816625Document44 pages8816625Tharangini GudlapuriNo ratings yet

- Midterm Exam Answer KeyDocument5 pagesMidterm Exam Answer Keyjamaica faith ramonNo ratings yet

- Charlotte Lamb DesperationDocument163 pagesCharlotte Lamb DesperationHiermela Hagos68% (50)

- 1200 английских словDocument89 pages1200 английских словАнна ГореславскаяNo ratings yet

- Quiz 1 - Corporate Liquidation ReorganizationDocument4 pagesQuiz 1 - Corporate Liquidation ReorganizationJane GavinoNo ratings yet

- Choosing Brand Elements To Build Brand EquityDocument25 pagesChoosing Brand Elements To Build Brand Equityoureducation.in100% (2)

- Emma Wasserman. Paul Beyond The Judaism Hellenism DivideDocument26 pagesEmma Wasserman. Paul Beyond The Judaism Hellenism DividedioniseNo ratings yet

- When All They Had Was LoveDocument14 pagesWhen All They Had Was LoveRahul Pinnamaneni100% (1)

- Nursing Notes Outline: Note Taking TipsDocument2 pagesNursing Notes Outline: Note Taking TipsHAROLD ANGELESNo ratings yet

- Grammar-Inversion ExercisesDocument2 pagesGrammar-Inversion ExercisesGeorgiaNo ratings yet

- Sumative Test (4TH Quarter) Science 8Document4 pagesSumative Test (4TH Quarter) Science 8Jonel Rule100% (2)

- ASSIGMENT 2 ScribDocument14 pagesASSIGMENT 2 Scribruslanaziz100% (1)

- Apa Research Paper SectionsDocument4 pagesApa Research Paper Sectionsfvgj0kvd100% (1)

- Visual FieldsDocument15 pagesVisual FieldsSaraNo ratings yet

- Dictionary Michel FoucaultDocument10 pagesDictionary Michel Foucaultsorin2013No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Pavement Roughness Using An Andriod Based SmartphoneDocument9 pagesEvaluation of Pavement Roughness Using An Andriod Based SmartphoneAshish WaliaNo ratings yet

- How To Pass MRCP Part 1 (Complete Guidelines) - Passing MRCP Part 1Document1 pageHow To Pass MRCP Part 1 (Complete Guidelines) - Passing MRCP Part 1Kendra GreyNo ratings yet

- Detached RetinaDocument1 pageDetached RetinamountainlordNo ratings yet

- Ted LevittDocument2 pagesTed Levittnantha74No ratings yet

- Problem Set Scenario - Answer Analysis Exercise 5%Document8 pagesProblem Set Scenario - Answer Analysis Exercise 5%dea.shafa29No ratings yet