Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Are Retail Incentives Legal

Are Retail Incentives Legal

Uploaded by

Steve CouncilOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Are Retail Incentives Legal

Are Retail Incentives Legal

Uploaded by

Steve CouncilCopyright:

Available Formats

WHITE PAPER

South Carolina Policy Council

1323 Pendleton St., Columbia, SC 29201 803-779-5022 scpolicycouncil.com

Are Retail Incentives Legal? A Review of the Sembler and Bass Pro Shops Incentives Legislation

Are economic development incentives legal? If the states frequent reliance on such incentives to attract firms like Boeing is any indication, the answer would seem to be an obvious yes. But that does not mean all incentives are legal or constitutional. Rather, economic incentives must serve a public purpose. In effect, this means economic incentives cannot be used primarily for the benefit of a private party. This explains why lawmakers were so quick to point out the multiplier effect of the Boeing deal that is, the spinoff jobs and investment that could be generated by Boeings expansion in North Charleston. Boeing aside, such requirements raise important legal questions about other economic incentives currently under consideration by the General Assembly in particular, incentives for retail projects like a proposed megamall in Jasper County (S 1054) and a Bass Pro Shops in Greenville County (H 4200). How is Public Purpose Defined? While the S.C. Supreme Court has taken up general questions related to economic incentives, a February 2009 opinion by the S.C. Attorney Generals Office reviews the relevant case law as it pertains to retail incentives or what are referred to as extraordinary retail establishments. The letter outlines the following five points: Public funds may only be used for public purposes. As the attorney generals office notes, citing Anderson v. Baehr (1975): It is not sufficient that an undertaking bring about a remote or indirect public benefit to categorize it as a project within the sphere of public purpose. Public purpose does not exclude private benefit. The S.C. Supreme Court has confirmed that a public purpose must encompass the promotion of the public health, safety, morals, general welfare, security, prosperity, and contentment of a substantial number of state residents. Yet this does not exclude incentives that would also benefit a private party. A four-prong test should be used to determine public purpose. Although the courts have usually deferred to the legislature in defining public purpose (a troubling precedent given the lack of separation of powers between the legislative and judicial branches in South Carolina), the Court has also developed a fourprong test to determine whether a public purpose is being met.

WHITE PAPER: Are Retail Incentives Legal?

South Carolina Policy Council

These four requirements, as articulated in Caldwell v. McMillan (1953), are as follows: The Court should first determine the ultimate goal or benefit to the public intended by the project. Second, the Court should analyze whether public or private parties will be the primary beneficiaries. Third, the speculative nature of the project must be considered. Fourth, the Court must analyze and balance the probability that the public interest will be ultimately served and to what degree. A project with negligible public benefit is likely unconstitutional. Essentially, the Court has found that publicly funded private endeavors that have only a minimal public benefit are unconstitutional. The Courts ruling in Anderson v. Baehr is instructive. Anderson challenged a law permitting a municipality to acquire condemned land and lease it to a private real estate developer. The Act undertakes to permit the city to effectually promote business undertakings to compete in free enterprise with other businesses which do not have the advantage which the Act would give, concluded the Court. We think it a fair conclusion to say that benefit to the developer or entrepreneur would be substantial, and the benefit to the public would be negligible and speculative. Special legislation is unconstitutional. The S.C. Constitution (article III, 34) prohibits special legislation in many cases, including where a general law can be made applicable. Whether this provision requires a uniform tax code is debatable, but precedent requires the Court to consider both the form and the practical operation when determining if special legislation meets constitutional muster. Given widespread agreement that S 1054 and H 4200 (not to mention the Boeing deal) are being passed for specific recipients, it is worthwhile to ask if these measures, especially in their practical operation, are instances of special legislation. What is the Public Benefit of Retail Incentives? While the attorney generals office did not address the legality of a particular economic incentives package, it did express grave reservations regarding the constitutionality of existing state law (12-21-6590) regarding extraordinary retail establishments. In particular, the attorney generals office voiced the following three concerns: The law does not clarify what public purpose is actually served by using sales tax revenue to fund retail establishment site construction and other improvements not owned by the state or one of its subdivisions. The legislation promotes a business undertaking and thereby serves a primarily private interest.

WHITE PAPER: Are Retail Incentives Legal?

South Carolina Policy Council

The law goes so far as to allow sales tax to be used for the actual construction of a portion of the retail establishment. Given these concerns, it might well be asked whether the proposed Sembler and Bass Pro Shops incentives proposals would withstand constitutional review. Consider the following points in relation to the Courts four-prong test: No net new sales and job creation. As indicated above, incentives legislation must serve a public purpose. This explains why S 1054 contains the assertion that it will create jobs and that the public will be the primary beneficiary of the incentive notwithstanding the incidental benefits that may be derived by the private grantees. The same bill, however, includes a statement of estimated fiscal impact that comes to the opposite conclusion. This bill does not help to create productive capacity that sells product outside the state, reads the analysis approved by State Economist William Gillespie. Because the facility adds to an already well established retail sector, it is difficult to expect that the facility will create new sales, but rather will shift sales from existing retailers and not add to sales that would otherwise occur in the absence of the provision. This conclusion is seconded by a Policy Council white paper showing that numerous academic studies have found retail incentives do not increase long-term employment. Direct and substantial private benefits. If the megamall planned by Sembler is not expected to create new retail sales (and thus jobs), there is no reason to believe the much smaller, and even less unique, Bass Pro Shops destination will create jobs. What, then, is the public benefit of this legislation? Tourism? This benefit is incidental to the primary purpose of both sites, which is to bring financial gain to Sembler and Bass Pro Shops through retail sales and the leasing of space related to such sales. Another reason to question the constitutionality of these two proposals is the attorney generals objection that subsidizing site prep, the construction of real or personal property, and the creation of parking areas will likely be viewed by a court as primarily benefitting the retail establishment. Speculative nature of the project. While S 1054 claims the incentives package for Sembler has been designed to avoid speculative risk, representatives from Sembler suggest otherwise. According to Sembler president Jeff Fuqua, the mall proposed for Okatie Crossings is highly speculative, such that with the incentive, it is just acceptable. The risks for the public are magnified because S 1054 does not include clawback provisions should Sembler default on its promised job and investment targets; the bill also does not include a cap on the sales tax break that Sembler is to receive. As highlighted in a recent SCPC report on economic incentives transparency, such mechanisms are necessary to protect taxpayers from risky investments. No evidence of public benefit. Absent reforms, such as the newly introduced Economic Incentive Transparency Act, which would require independent analysis

WHITE PAPER: Are Retail Incentives Legal?

South Carolina Policy Council

of economic incentives deals, along with public hearings and ongoing monitoring, it is very difficult to determine whether the public interest is being served by economic incentives. As reported by The Nerve: [Incentives] negotiations on the front end and finalized agreements on the back end typically are done behind closed doors. And even if agreements are eventually released, taxpayers arent informed about the specific costs of certain incentives because they are considered private tax records. On the other hand, many economists agree that economic incentives in particular, retail incentives are ineffective. As found by Michael Hicks 2007 study on incentives for mega-retailers like Cabelas, From a public policy standpoint there is nothing to recommend regional polices to attract or dissuade the location of retail firms. Again, there is no reason to expect that either the Sembler deal or the Bass Pro Shops plan will produce different results. Legal Challenges in Other States Taxpayers in several states, most notably Arizona, have challenged the legality of economic incentives. In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in DaimlerChyrsler Corp. v. Cuno that taxpayers as such do not have standing to challenge state tax incentives or spending decisions in federal court. This ruling, however, does not prevent such challenges from moving forward in state court. Arizona. In January 2010, the Arizona Supreme Court unanimously ruled that economic incentives violate the gift clause of the state constitution unless such incentives can be shown to have a tangible and equitable public benefit. In effect, the Court ruled that indirect benefits such as job creation and tax revenue are insufficient evidence that the public good is being served. The case (Turken v. Gordon) arose from a 2007 incentive agreement in which the City of Phoenix gave a $97.4 million subsidy to a shopping center called CityNorth, a $1.8 billion high-end retail development in an affluent part of Phoenix. The subsidy was to be provided in the form of a sales tax rebate to the private real estate development firm, Klutznick Company. (Sounds a lot like the proposed Sembler deal currently under consideration by the General Assembly.) North Carolina. Like South Carolina, our neighbor to the north has doled out millions in tax incentives, with Dell topping the list in 2005 at $259.9 million. (Dell announced last year it was closing the Winston-Salem factory that prompted the multimillion incentives package.) The state also passed another high-tech incentives deal in 2006, giving Google $100 million in tax breaks to build a data center. In 2007, the North Carolina Institute for Constitutional Law sued (Munger v. State), arguing that the incentives legislation violated the public purpose and exclusive emoluments clauses of the North Carolina constitution. The public purpose clause states that the power of taxation shall be exercised in a just and equitable manner, for public purposes only while the emoluments clause states that no person or set of persons is entitled to exclusive or separate emoluments or privileges from the community but in consideration of public services. In

WHITE PAPER: Are Retail Incentives Legal?

South Carolina Policy Council

addition, article V, 2 of the N.C. Constitution requires uniform taxation for all classes of property. In February 2010, the state Court of Appeals rejected the suit, holding that the mere fact that plaintiffs pay North Carolina income and sales and use taxes does not give them standing. The 30-page opinion did not substantially address the merits of the case, focusing instead on questions of standing. Conclusion In a down economy, it is tempting to embrace every bill promising new jobs as a boon for the economy and thus the state as a whole. In order to stimulate real economic growth, however, these new jobs must, in fact, be new. Retail incentives have been shown to produce no net new job growth. Rather, such incentives are merely a taxpayer subsidized prize to the benefit of one private retailer over another. As such, a strong case can be made that retail incentives, such as that proposed in S 1054 and H 4200, are unconstitutional.

Nothing in the foregoing should be construed as an attempt to aid or hinder passage of any legislation.

South Carolina Policy Council

1323 Pendleton St., Columbia, SC 29201 803-779-5022 scpolicycouncil.com

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

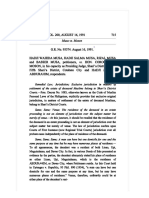

- Baylosis Vs Chavez, GR No 95136Document27 pagesBaylosis Vs Chavez, GR No 95136Add AllNo ratings yet

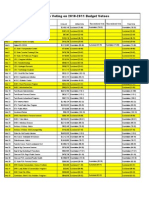

- Exec Summ Recorded Votes 082610Document1 pageExec Summ Recorded Votes 082610Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Exec Summ Shorten The Session 082610Document1 pageExec Summ Shorten The Session 082610Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10Document24 pagesChapter 10Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document14 pagesChapter 1Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Workforce Development Requires Educational Reform: by L. Brooke ConawayDocument14 pagesWorkforce Development Requires Educational Reform: by L. Brooke ConawaySteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document22 pagesChapter 8Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet: Which Counties Spend The Most of Your Tax Dollars?Document7 pagesFact Sheet: Which Counties Spend The Most of Your Tax Dollars?Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6Document19 pagesChapter 6Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Mployment Security Organization of Southern StatesDocument6 pagesMployment Security Organization of Southern StatesSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document28 pagesChapter 2Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document22 pagesChapter 3Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document20 pagesChapter 7Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document21 pagesChapter 5Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- 4478 Fact Sheet 061010Document4 pages4478 Fact Sheet 061010Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Best Worst 2011Document20 pagesBest Worst 2011Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Best/Worst of 2010: South Carolina Policy CouncilDocument47 pagesBest/Worst of 2010: South Carolina Policy CouncilSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- The $21 Billion State Budget: South Carolina's Three Spending CategoriesDocument25 pagesThe $21 Billion State Budget: South Carolina's Three Spending CategoriesSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

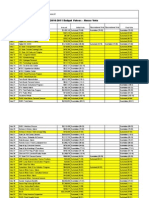

- Senate Budget Veto VotingDocument2 pagesSenate Budget Veto VotingSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- BudgetWatchObesityMandate 052710Document2 pagesBudgetWatchObesityMandate 052710Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Aiken Fact SheetDocument2 pagesAiken Fact SheetSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Budget Watch I95 052510Document3 pagesBudget Watch I95 052510Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- HealthcareDocument2 pagesHealthcareSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- House Budget Veto VotingDocument3 pagesHouse Budget Veto VotingSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Budget Veto HouseDocument4 pagesBudget Veto HouseSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- BudgetDocument2 pagesBudgetSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Sat Scores Report 091010Document5 pagesSat Scores Report 091010Steve CouncilNo ratings yet

- UpdateDocument1 pageUpdateSteve CouncilNo ratings yet

- Juan Padilla Lambert, A055 860 485 (BIA Aug. 23, 2016) PDFDocument14 pagesJuan Padilla Lambert, A055 860 485 (BIA Aug. 23, 2016) PDFImmigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Course Outline For Agrarian Reform Law and Social Legislation EuDocument5 pagesCourse Outline For Agrarian Reform Law and Social Legislation EuFraicess GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Correctional Institution For WomenDocument2 pagesCorrectional Institution For WomenNam KcalbNo ratings yet

- Vodafone PortugalDocument15 pagesVodafone PortugalMica DGNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 200274. April 20, 2016. Melecio Domingo, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Genaro MOLINA and ELENA B. MOLINA, Substituted by ESTER MOLINA, RespondentsDocument17 pagesG.R. No. 200274. April 20, 2016. Melecio Domingo, Petitioner, vs. Spouses Genaro MOLINA and ELENA B. MOLINA, Substituted by ESTER MOLINA, RespondentsLalaNo ratings yet

- Mattel V FranciscoDocument2 pagesMattel V FranciscoMichael Enad100% (1)

- Supreme Court: J. Solano Reyes, For Petitioner. Cleofe B. Villar-Verzola For RespondentsDocument4 pagesSupreme Court: J. Solano Reyes, For Petitioner. Cleofe B. Villar-Verzola For Respondentsgem_mataNo ratings yet

- Labor RelationsDocument299 pagesLabor Relationsmtabcao100% (1)

- City of Manila vs. Judge Laguio Gr. No. 118127Document29 pagesCity of Manila vs. Judge Laguio Gr. No. 118127Hanelizan Ert RoadNo ratings yet

- Order Dismissing Kurt Huy Pham's Lawsuit Against His Employer Chase Investment Services 02-20-2013Document10 pagesOrder Dismissing Kurt Huy Pham's Lawsuit Against His Employer Chase Investment Services 02-20-2013FrankBulNo ratings yet

- Perez v. HagonoyDocument2 pagesPerez v. HagonoyJessa F. Austria-CalderonNo ratings yet

- Cyber Crime Investigation in IndiaDocument13 pagesCyber Crime Investigation in IndiaAanika AeryNo ratings yet

- Federalism Class 10 Notes Social Science Civics Chapter 2Document4 pagesFederalism Class 10 Notes Social Science Civics Chapter 2ParthuNo ratings yet

- Whitey by Dick Lehr and Gerard O'Neill - ExcerptDocument15 pagesWhitey by Dick Lehr and Gerard O'Neill - ExcerptCrown Publishing GroupNo ratings yet

- Motion To Attend Wedding Ceremony of DaughterDocument2 pagesMotion To Attend Wedding Ceremony of DaughterMeybs D. DimaanoNo ratings yet

- Jamil V ComelecDocument46 pagesJamil V Comelecpiarodriguez88No ratings yet

- ESMILLA - Heirs of Ramiro V Spouses BacaronDocument3 pagesESMILLA - Heirs of Ramiro V Spouses BacaronJohnny A. Esmilla Jr.No ratings yet

- LAWSUIT: Hagedorn Family Filing Against Jennifer CarnahanDocument5 pagesLAWSUIT: Hagedorn Family Filing Against Jennifer CarnahanFluenceMediaNo ratings yet

- Law 124 Crimpro OcDocument25 pagesLaw 124 Crimpro OcAgent BlueNo ratings yet

- Avera v. Garcia and RodriguezDocument3 pagesAvera v. Garcia and RodriguezGlenz LagunaNo ratings yet

- GFGHFHDocument8 pagesGFGHFHAcuxii PamNo ratings yet

- LEgal Ethics Latest JurisDocument6 pagesLEgal Ethics Latest JurisdyosaNo ratings yet

- Musa v. MosonDocument8 pagesMusa v. MosonTon RiveraNo ratings yet

- Icls Training Materials Sec 2 What Is Intl Law2Document26 pagesIcls Training Materials Sec 2 What Is Intl Law2Dustin NitroNo ratings yet

- Assignement 3 - 20 Mobilia Products Inc v. DemecilioDocument1 pageAssignement 3 - 20 Mobilia Products Inc v. DemeciliopatrickNo ratings yet

- Memorial On Behalf of Respondent (Team Code - LLDC - 087)Document31 pagesMemorial On Behalf of Respondent (Team Code - LLDC - 087)AYUSH R MENON 1850408No ratings yet

- Denoso vs. CADocument3 pagesDenoso vs. CAMarie Nickie BolosNo ratings yet

- CRIMPRO 012 People Vs ValdezDocument5 pagesCRIMPRO 012 People Vs ValdezEm Asiddao-DeonaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Milwaukee Refrigerator Transit Co. 142 F. 247Document7 pagesUnited States v. Milwaukee Refrigerator Transit Co. 142 F. 247Jayvee RobiasNo ratings yet