Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DocScanner 29 May 2024 12-08 Am

DocScanner 29 May 2024 12-08 Am

Uploaded by

Sazia Begum0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views34 pagesOriginal Title

DocScanner 29 May 2024 12-08 am

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views34 pagesDocScanner 29 May 2024 12-08 Am

DocScanner 29 May 2024 12-08 Am

Uploaded by

Sazia BegumCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 34

mes.

Lae

Moot Disorders ad Suicide

CHAPTER 7

the following case.

‘A Successful “Total Failure”

Margaret, a prominent businesswoman inher ate-oties,

noted for her energy and productivity, was unexpectedly

deserted by her husband fora younger woman. Following

her inital shock and rage, she began to have uncontrol

lable weeping spells and doubts about her business acu-

men. Decision making became an ordeal. Her spirits

rapidly sank, and she began to spend more and more

| time in bed, reusing to deal with anyone. Her alcohol

© consumption increased to the point where she was sel:

dom entirely sober. Within period of weeks, she had suf-

{fered serious financial losses owing to her inability, or

| refusal, to keep her affairs in order. She felt she was a

| total filur,” even when reminded of her considerable

“personal and professional achievements; indeed, her

-selfcricism gradually spread to all aspects of her life

andher persona history. Finally, alarmed members ofher

ily essentially forced her to accept an appointment

witha clinical psychologist.

‘Was something “wrong” with Margaret, ot was she merely

‘experiencing normal human emotions because of her hus-

band’s deserting her? The psychologist concluded that she

‘was suffering from a serious mood disorder and initiated

treatment. The diagnosis, based on the severity of the

symptoms and the degree of impairment, was. major

‘depressive disorder, Secondarily, she had also developed a

serious drinking problem—a condition that frequently co-

‘occurs with major depressive disorder.

exam, not getting into o,,

palling 2 o

seo ine NE yp th 9 ang

it depress rate school, ane 28 depressed Mood in man |

1 of us 8 :

ert enoice of colle that severe alterations in my

i a involv isturbances

ner are all ext igorders IV ch cases the disturbane of moog a]

people. However ‘ time, In UCT PT Gaptive, and often lead tose,

and for much Ln 5 cleat mace. In facts it as been ex

‘ istent e ;

intense and persistent ak peerage eal ond

gus problems in rlatlONST | ranked aMMOnE orld except Africa, and it vag

mated that 2000 OEP in all ats OF eg States, FMRI abOvE hag

terms of years lost R health condition in the roe Preease-burden” of depres

the numberone such Healt) <1" vera the rreatment 2 nding

direct costs ture deaths) —totalleg

fase and stroke (Ustll

: is, the total ee

‘ciety—that i, the and P

esha mised oe disap yr eo percent ofthe reported cos

: lone, :

$83.1 billion in ee Smonkplace (Greenbers, Kessler et al» 2003). Consider

resulting from problet

erse in nature, asisillustrated by

e gnized in the DSM-IV-TR

semanytypesof depression recognized int

thor we wll discus Nevertheless, int all mood disorders

ive disorders), extremes of emotion

v merly called affective disorders), extrem

ie ition or deep depression—dominate

cor affect soaring el

of Uisieal picture, other symptoms are also present, but

the abnormal mapd is the defining feature.

Wuat ARE Moop

DISORDERS?

“The two key moods involved in mood disorders are mania,

often characterized by intense and unrealistic feelings of

excitement and euphoria, and depression, which usually

involves feelings of extraordinary sadness and dejection.

Some people experience both of these kinds of moods at

‘one time or another, but other people experience only the

depression. These mood states are often conceived to beat

opposite ends of mood continuum, with normal mood

in the middle. although this concept is accurate t0 ¢

eres, sometimes patient may have symptoms pf manit

sed orion during the same time period (In thes

le cases, the person experiences rapidly altet~

‘aUingmoodssuchassadness, cuporia, and eabiy al

ren gime ead floes

the el ist discuss the unipolar disorders, in which

wwe wil diane ences only depressive episodes, and thet

xpress Cat bipolar disorders, in which the pero®

tinction is saaine ic and depressive episodes. This dis

tnpolerarereminent in DSM-1V-TR, and although the

holy co POL forms of mood disorder may not be

arate and distinct, there are notable difference

‘Mood disorders are div

cors,and treatm

~ yoms caus

flerentiate amor

rents. As

. “n Weill see,

iat costomiry te ng the mood ‘ior,

Perms OY Severin A tans

j ies the rau dete of impairment evi.

Fhose areas and DY duration —whether thea,

4 esa clonic, of intermittent (with periods ot

BE oral functioning between the episodes of

| ei

080 ted, diagnosing unipolar or bipolar disorder

Jefe diagnosing what kind of mood episode the

ints with. The most common form of mood {

se Fiat people present with is a major depressi

le pressive

ge Pe dealed in the DSM-IV-TR table, Criteris for

Fypressive Episode, to receive this diagnosis, the

sfineest in pleasurable activities) for most of every

od for most days for at least 2 weeks. In addition, he

must show at least three or four other symptoms

ijt of five) that range from cognitive symptoms

(issteings of worthlessness or guilt and thoughts of

Gate to behavioral symptoms (such as fatigue or phy

‘agiation), to physical symptoms (such as changes in

setteand sleep patterns).

‘The other primary kind of mood episode is a manic

aiode, in which the person shows markedly elevated;

phair expansive mood, often interrupted by occa-

ged outbursts of intense irritability or even violence—

pialarly when others refuse to go along with the

‘atic person’s wishes and schemes. These extreme

sods ust persist for at least a week for this diagnosis to

txmale In addition, three or more additional symptoms

tzatoccurin the same time period, ranging from behav-

ial symptoms (such as a notable increase in goal-

Sxcted activity, often involving loosening of personal

‘odcaltural inhibitions as in multiple sexual, political, or

tgous activities), to mental symptoms where self-

xen becomes grossly inflated and mental activity may

sredup (uch as a “fight of ideas” or “racing thoughts”),

“»physical symptoms (such as a decreased need for sleep,

‘ythomotor agitation). (See the DSM-IV-TR table, Ci

‘ti fora Manic Episode on p. 228.)

Research suggests that mild mood disturbances are on

‘ame continuum as the more severe disorders. That is,

dferences seem to be chiefly of degree, not of kind, a

ion supported in several large studies examining

yt 8Kendler & Gardner, 1998; Ruscio & Ruscio,

However, there is also considerable heterogeneity in

sit it which the mood disorders manifest them-

yattthere are multiple different subtypes of both

i and bipolar disorders, and somewhat different

Nelyeand treatments are important for different

.

sg important to remember that suicide is a di

Sey) feguent outcome (and always a potential out,

Sue Bhificant depressions, both unipolar and

fact, as discussed in the latter part of this chap-

MS

ptf be markedly depressed (or show a marked fof

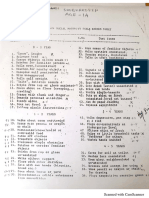

Criteria for Major Depressive Episode

A. Five (or more) ofthe fllowing symptoms have been

present dung the same 2-veek period and represent @

Change from previous functioning: atleast one of the

Symptoms is either 1) depressed mood or 2) loss of

les interest or pleasure.

WS SEiessed most of the day, nearly every day. as

Cis eo indented by ether subjective reports or observation

P29 made by thers,

(2) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or

almost al, activities most ofthe day, nearly every day.

(3) Significant weight loss (when not dieting) or weight

sain.

(@) Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

(5) Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day.

(@ Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

(7) Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or

guilt nearly every day.

shed ability to think or concentrate, oF

iveness, nearly every day.

(9) Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide, or recurrent

suicidal ideation without a plan, ora suicide attempt

or plan.

B. The symptoms do not meet criteria for a Mixed Episode,

C. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or

impairment.

ter, depressive episodes are clearly the most common of the

predisposing causes leading to suicide.

The Prevalence of Mood Disorders

Major mood disorders occur with alarming frequency—at

least 15 to 20 times more frequently than schizophrenia,

for example, and at almost the same rate as all the anxiety

disorders taken together. Of the two types of serious mood

disorders, unipolar major depression is much more com-

mon, and its occurrence has apparently increased in recent

decades (Kaelber, Moul, & Farmer, 1995; Kessler, Berglund,

et al, 2003). The most recent epidemiological results from

the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication study found

lifetime prevalence rates of unipolar major depression at

nearly 17 percent (12-month prevalence rates were nearly

7 percent) (Kessler, Chiu, et al, 2005), Moreover, rates for

unipolar depression are always much higher for women

than for men (tisually about 2:1), similar to the sex differ.

ences for most anxiety disorders (see Chapter 6). The issue

of sex differences in unipolar depression will be discussed

ppropriate

Dysthymic Disorder

The point at which mood disturbance becomes a diagnos”

able mood disorder is a matter of clinical judgment and

usually concerns the degree of impairment in functioning

that the individual experiences. Dysthymic disorder is

considered to be of mild to moderate intensity, but its pri-

mary hallmark is its chronicity. To qualify for a diagnosis

of dysthymic disorder (or dysthymia), a person must have

a persistently depressed mood most of the day, for more

days than not, for at least 2 years (1 year for children and

adolescents). In addition, individuals with dysthymic dis-

order must have at least two of six additional symptoms

when depressed (see the DSM-IV-TR table, Criteria for

Dysthymic Disorder). Periods of normal mood may occur

briefly, but they usually last for only a few days to a few

weeks (and for a maximum of 2 months). These intermit-

tently normal moods are one of the most important char-

acteristics distinguishing dysthymic disorder from major

depressive disorder.

Dysthymia is also quite common, with a lifetime

prevalence estimated between 2.5 and 6 percent (Kessler

et al., 2005),

erglunds ne The aver

5 years, but it can persist gee

1, 1997) Chronic stress hash,

y of symptoms overa 7.5,

yx Klein, & Davila, 2004), Rd

n

cover from dysthymia wig

apse within an average of a,

h

half may Fel :

eat Swartz, Rose, & Leader, 2000), San

+ the teenage YeATS AME OVET 50 perce

before age 21-

g case is typi

1 of this disorder,

a as,yearold junior executive. ...complained of being

gepressed” about everyting: her job, her husband, and

her prospects forthe future...-Her complaints were of

vorsistent feelings of depressed mood, inferiority, and

pessimism, which she claims to have had since she was

fe or 27 years old. Although she did reasonably well in

‘college, she constantly ruminated about those students

‘who were “genuinely intelligent.” She dated during col-

lege and graduate school but claimed that she would

never go after a guy she thought was “special,” always

feeling inferior and intimidated...

Just after graduation, she had married the man she

‘was going out with at the time. She thought of him as rea-

sonably desirable, though not “special,” and married him

primarily because she felt she “needed a husband” for

‘companionship. Shortly after their marriage, the couple

started to bicker, She was very critical of his clothes, his

job, and his parents; and he, in turn, found her rejecting,

controlling, and moody. She began to feel that she had

made a mistake in marrying him.

Mes) she has also been having difficulties at

work She i assigned the most menial tasks atthe firm

Pecans Been sient importance

spore: She sis that she frequently does #

is required, an aA iat is given her, never does more en

ae tndmever demonstrates any assertiveness

her protesonne, 2 that she will never go very sary

nection oy acusese des not have the right "em

- otmoney cee tes does her husband, yet she dreams

band inohes eee Powe Her soil with her his

aoe Seater coupes, The man in te

ihe women yg ie of her husband. She i. sul

ath he peo oe interesting and urimpres

better offthan cae tne Seem 10 lke her are prob

Under the bur Ei ,

marriage, ee of her dissatisfaction with Nef

uninterested) ey on Ner Social life, feeling tired 2

fe" she now enters treatment for "

thi ti tie

me. (Spitzer eta, 2002, pp. sie)

1

i

;

|

| Sous of death or suc,

Major Depressive Disorder

The disgnostic criteria for major depressive disorder

esquire that the person exhibit more symptoms than are

ssquired for dysthymia and that the symptoms be more

sistent (not interwoven with periods of normal

rood). To receive a diagnosis of major depressive disoe-

éezaperson must be in a major depressive episode (initial

or single, or recurrent). An affected person must experi-

ace either markedly depressed moods or marked loss of

intrest in pleasurable activities most of every day, nearly

every day, for at least 2 consecutive weeks. In addition to

‘Saving one or both of these symptoms, the person must.

caperience at least three or four additional symptoms

daring the same period (for a total of at least five symp-

toms), as detailed in the DSM-IV-TR table, Criteria for

Major Depressive Episode. These symptoms include cog-

aitive symptoms (such as feelings of worthlessness or

gilt, and thoughts of suicide), behavioral symptoms

(uch as fatigue, or physical agitation), and physical

symptoms (such as changes in appetite and sleep pat-

terns).

Itshould be noted that few if any depressions—includ-

ingmilder ones—occur in the absence of significant ans

ty (¢g,, Akiskal, 1997; Merikangus et al., 2003; Mineka

al, 1998). Indeed, there is a high degree of overlap

seen measures of depressive and anxious symptoms in

‘eseports and in clinician ratings. At the diagnostic le

thee are very high levels of comorbidity between moo

‘8d anxiety disorders. As discussed later in this chapter

(ee Developments in Thinking 7.2 on p. 250), the issues

Ssttounding the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety,

‘hich have received a great deal of attention in recent years,

“every complex.

The following account illustrates a

f major depressive disorder.

moderately severe

Connie

Connie, a 33-year-old homemaker and mother of a 4-year-

old son, Robert, is referred ...to a psychiatric outpatient

rogram because ... she has been depressed and unable

to concentrate ever since she separated from her hus-

band 3 months previously. Connie left her husband, Don-

ald, after a 5-year marriage. Violent arguments between

them, during which Connie was beaten by her husband,

hhad occurred for the last 4 years oftheir marriage, begin:

when she became pregnant with Robert. There were

daily arguments during which Donald hit her hard enough

to leave bruises on her face and arms.

Before her marriage... she was close to her parents

{and} had many friends whom she also saw regularly...

Inhigh school she had been a popular cheerleader and a

‘good student, ... She had no personal history of depres-

sion and there was no family history of ... mental illness.

During the first year of marriage, Donald became

increasingly irritable and critical of Connie. He began to

request that Connie stop calling and seeing her friends

after work, and refused to allow them or his in-laws to visit

their apartment... Despite her misgivings about Donald's

behavior toward her, Connie decided to become preg-

nant. During the seventh month of the pregnancy...

Donald began complaining [and] began hitting her with

his fists. She left him and went to live with her parents for

a week. He expressed remorse....and...Connie returned

to her apartment. No further violence occurred until after

Robert's birth. At that time, Donald began using cocaine

every weekend and often became violent when he was

high.

In the 3 months since she left Donald, Connie has

become increasingly depressed. Her appetite has been

poor and she has lost 10 pounds. She cries alot and often

Wakes up at 5:00 Am. and is unable to get back to

(continued)

CHAP TEN 7 Mor tvanders and Suiile

Connie pale and thin... the speaks slowly,

i Her depressed mood and lack of enerBy. She.

‘/6 thal her only pleasure 1 In belng wth er son She

‘able to Lake care of him phystcally, but feels gully because

her preoccupation with hier own bad feelings prevents Her

{fom belng able to play with him, She now has no contacts

‘other than ith ho parents anderson he fols woth

les dnd blames hereel for her marital problems say

that if she had been a better wile, maybe Donald would

have been able (0 give up the cocalne,. (adapted fromm

Spl et al 300 9p, 414-43)

Note that Connie’ case nicely illustrates that perso

With major depresive disnrder shows not only mod

tymptoms of sade hut alo a variety of symptoms that

tre mote severe than in milder forms of depression, Cone

tle shows vars cognitive dlstonthons, including feeling

‘worthless and yuity. She complains ofa ack of energy anid

inability 1 play with her child, Her biological eymptoms

ippetite and

twill friends ko occurs commonly with

depression, i part becaue the person is unmotivated to

eck contact, Connie's cave aleo nicely ilusrates the mull

pplecompler Interacting factors that may be involved in the

tology of depression, Althouglt Connie did not have «

personal or a family history of depression, the experiences

from 5 years ofa very difficult mariage with a violent and

abusive husband were suliclent to finally precipitate her

major depression,

DEPRESSION THROUGHOUT THE LIFECYCLE Altho

he onset of unipolar mood disorder mut often oc

during, late adolewence up to middle wut

reactions may begin at any tine fron eatlycikdhoend to

Cold age, Depression was once thought not to vceur jn

dhildhood, hut more recent revearch hae found snajor

depressions in presdolewent children, and iti etinated

‘that about 2.0 4 percent of chuol-age children mect the

criteria for sone form of unipolar diorder, with perhaps

fanother 2 percent exhibiting chaonic mild depression (see

Garber 6 Horawits, 2002), ven infants may experience »

form of depression (commun knnwn as unaclitie depres

‘on or despait) if they ate separated for a prolonged

period from thelr attachient figure (usually thelr mother,

Havaloy, 1973, 19805 Speer eta, 1),

“rhe incidence of depression vies sharply during a

Jewence-# period of great tunnel for many people,

Sneed, ane review estimated that approximately 15 020

percent of adolescents experience nisior depresive dlsor-

der at some point ducting their wdotesrnt years (Lewine

“sohin 6 Vaan, 2002), nnd the wveraye ayy onset for

ws been decreas

solescenn depresion has Dee surg

pare Mea thevineon eta 1993 Speier ea, Pa

‘ perind that gx differences jy hk

fs during this tlie p

rye (Wankin& Abram, 4

depression first emerne mn, ay

qed ce, 20: Nolen Hore Gig

jn esearch 71 on p. 244) the

jor depressive divorder in adgte

eimat at eat hough youn. aduliond when yu

duals sow small but siicant psychoses jpe

rare in many donna, including helt Occupation

their interpersonal relationships, and ther general gyi."

Uf life (eqhe Vewinsohn, Hobe, et aly 2003), Seg!

Chapter 1)

ve occurrence of major Aepresion cantina,

Interlife,Ahough the I-year prevalence of major dep,

inlay ven ple we se

uner adults (Kessler etal 2003), major depression

pyar als are stil considered majong

Hic heath problenm today (Beekman, Deeg, etal, 2

Moree, esearch suggests hat rates of depression ag,

plyically ill residents of nursing homes or residential ae

facltes are substantially higher than among older adel,

living at home (see Powers et al 2002). Unfortu,

depression in ater life can be difficult wo diagnose becase

many of the symptoms averlap with those of veveral ma

ical nese anu dementia (Alexopoulos eta, 200) att

is very important to try and diagnose it elibly breve

depression in later life has many adverse consequences

8 person's health, including doubling the vsk of dah io

people who have had a heart attack or stoke (Suk

et a, 2002) (wee Chapter 10),

(ee Developmen

ter effects of 3

SPECIFIERS FOR Majon DEPRESSION Some ink

uals who meet the basic criteria for diagnosis of major

depreion an have adiional patterns of symptoms

features that are important to note when making dig”

sisbecause they have implications for understanding =

ahout the course of the disorder and/or its most effect

treatment, They: different patterns of symptoms off

tures are called specifiers in DSM-1V-TR. One such spe

fier is major depressiveepivode with melancholic featur

Thi designation sapped wen, in dition to meld

the criteria for major depression a patient either bas

interest or pleasure in almost all activities ar does not 4

10 usually pleasurable stimuli or desired events. In #4

tion, the patient must experience at least three of the

Sing early moringamaenings (2) depression

srs in the maming, (3) marked payhomotr =

tomato, spicata appetite a 2

(5) inapproprinte on excesive gui, and (6) 6

ited ‘ is qualitatively different from the sadnes

tlenced during a nonmelancholic depression. This

subtype of depression nasa wih a higher

Joading than other forms of depression (Kendler, 7"

}

atc ymptoms, characterized by loss of contac

ay and dslsions (Ge bei) or hllcintions

sits? erEELION) ay sometimes accompany

Srptoms of major depression. In such cares eh,

srg the diagnosis that is noted is neve

settee episode with psychotic features 0,

drresiions oF hallucinations present ar

ent-—that is they seem in some sense “appro

ne aris depression because the conten ier

oe, sch a8 themes of personal inadequacy cu

fred punishment, death, and disease. For example,

$etutisional idea that one’s internal organs have totally

forted—an idea sometimes held. by severly

ed people—ties in with the mood ofa despondiont

Feelings of worthlessness and guilt areakeo carne

apart of the clinical picture (Ohayon &e Shatrberg

Sha). Psychtically depressed individuals are likely

tne a pooret long-term prognosis than nonpsychotie

Spresives (Coryell, 1997), and any recurrent episodes

salikelyto be characterized by psychotic syreptome

ing et al, 2004). Treatment generally involves an

(psychotic medication as well as an antidepressant In

Ferre cass, psychotic depression occurs in the context

Mpospartum depression (Miller, 2002), where mothers

{uy Hl their babies because of the hallucinations or

{sions they have

‘Athird important specifier is used when the individ-

aul shows “atypical fentures” Major depressive episode

with aypical features includes a pattern of symptoms

Guacerized by mood reactvitys that is, the person's

‘ood brightens in response to potential positive evens. In

tition, the person must shove two or more of the follow

ificant weight gain or increase

(sleeping too much),

{leaden paralysis (heavy feelings in arms or legs), and

(#)along-standing pattern of being acutcly sensitive to

re major

edinarily,

fe mood-

int

fie

noe

weight, excessive gt

symptoms: wei

Characteristic Symptoms

‘Three of the following: Early morning awakening, depression worse in the

‘morning, marked psychomotor agitation or retardation, loss of appetite or

qualitatively different depressed mood.

Delusions or hallucinations (usually mood-congruent); feelings of guilt and

‘worthlessness common.

“Mood reactvity—brightens to positive events; 190 ofthe four following

1 gain or increase in appetite, hypersomnia, leaden paralysis,

being acutely sensitive t

Atleast two or more episodes in past2years that have ocurred at the sme ime

(usually fall or winter), and full remission at the same time (usually spring)

other nonseasonal episodes in same 2-year period. ie

Unipolar Mood Dieanders

nber of

imerpersonal rejection. & disproportionate number if

individuals who have atypical features are fernabes,

have an earlier-than-average age of onset and who are

more likely to show suicidal thoughts (Matra, Revicki

Davidson, & Stewart, 2003). This is also an important

specifier because there are indications that individuals

th atypical features may preferentially respond to a dif-

ferent class of antidepressants—the monoamine oxidave

inhibitors—than do most other depressed individuals, See

‘Table 7.1 fora summary of the major specifiers.

Although not recognized as an official specifier itis

not uncommon that major depression may coexist with

dysthymia in some people, a condition given the designa-

tion double depression (Holand & Keller, 2002; Keller,

Hirschfeld, & Hanks, 1997). People with double depression

are moderately depressed on a chronic basis (meeting,

symptom criteria for dysthymia) but undergo increaved

problems from time to time, during which they also mest

ria for a major depressive episode. Among, clinical

‘samples of people with dysthymia, the experience of dou-

ble depression appears to be common, although it may be

much less common in people with dysthymic disorder

who never seek treatment (Axiskal, 1997). For example,

one clinical sample of nearly 100 individuals with early

onset dysthymia (onset before age 21) were followed for

5 years, during which time 77 percent experienced at least

tone major depressive episode (see also Keller et al, 1997;

Klein et al, 2000). Although nearly all individuals with

double depression appear to recover from their major

depressive episodes (at least for a while), recurrence is

‘common (Boland & Keller, 2002; Klein etal. 2000).

DEPRESSION AS A RECURRENT DISORDER When a

diagnosis of major depressive disorder is made, itis usually

also specified whether this is a first and therefore single

terpersonal rejection.

~ a

CHAPTER 7 Mond Disonlersand Suicide

(initial) episode or a recurrent episode (preceded

by one or more previous episodes). This reflects the

fact that depressive episodes are usualy tive-lim=

iteds according to DSM-IV-TR, the average dura

tion of an untreated episode is about 6 months. In

2 large untreated sample of depressed women, cer

tain predictors pointed to a longer time to spon!

Reous remission of symptoms: having financial

iffculties, severe stressful life events, and high

‘genetic risk (Kendler, Walters, & Kessler, 1997). In

some cases major depression does not remit for

‘over 2 years, in which case chronic ‘major depres-

sive disorder is diagnosed,

Although most depressive episodes remit

(which is not said to occur until symptoms have

Femitted for at east 2 months), depressive episodes

‘usually recur at some future point. In recent years,

Fecurrence has been distinguished from relapse,

‘where the latter term refers to the return ‘of symp-

toms within a fairly short period of time and prob-

ably reflects the fact that the underlying episode of

depression has not yet run its course (Boland &

toe iil rte lites or thos n he

see empha mre eto eR scsonl eft day

rich dpesson ccs rina nthe llard winter months ndten

remit in the spring or sumer months.

Keller, 2002; Frank eta, 1991), Relapse may com-

monly occur, for example, when pharmacotherapy

is terminated prematurely after symptoms have remitted

but before the underlying episode is really over (Hollon

tal, 2002a, 2002b; 2008).

The proportion of patients who will exhibit a recur-

rence of major depression is very high (about 80 percent,

according to Judd, 1997), although the time period before

a recurrence occurs is highly variable. In one very large

national study of over 400 patients across 5 sites followed

for more than a decade, 25 to 40 percent had a recurrence

within 2 years, 60 percent within 5 years, 75 percent within

10 years, and 87 percent within 15 years (Boland & Keller,

2002; Keller & Boland, 1998). There is also evidence that

the probability of recurrence increases with the number of

prior episodes.

The traditional view was that between episodes, per-

son suffering from a recurrent major mood disorder is

‘essentially normal. However, as more research data on the

course of depression became available (e.g, Coryell &

Winokur, 1992; Judd et al, 1998), it became clear this is

frequently not the case. For example, in a large 5-site study

with over 400 patients, Judd et al, (1998) found that even

patients experiencing their first episode at the time the

study began showed no symptoms at all during only 54

percent of weeks during a 12-year follow-up period, rela-

tive to only 37 percent showing no symptoms among those

experiencing a second or later episode at the start of the

study. Moreover, people with some residual symptoms,

and/or with significant psychosocial impairment, follow-

jing an episode are even more likely to have recurrences

than’ those whose symptoms remit completely (Judd,

Paulus, Zeller, eta, 1999; Solomon et al, 2004).

SEASONAL AFFECTIVE DISORDER Some people who

experience recurrent depressive episodes show a seasonal

pattern commonly known as seasonal affective disorder,

‘To meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for recurrent major depres

sion with a seasonal pattern, the person must have hat

least two episodes of depression in the past 2 years occut+

ring at the same time of the year (most common; fallor

winter) and full remission must also have occured atthe

same time of the year (most commonly, the sprin

addition, the person cannot have had other, nons

depressive episodes in the same 2-year period, and most

of the person's lifetime depressive episodes must have

been of the seasonal variety. Prevalence rates suggest that

winter seasonal affective disorder is more common in

people living at higher latitudes (northern climates) and

in younger people.

> What are the major features that differentiate

dysthymic disorder and major depressive

disorder?

_| > What are three common specifiers of major

depressive disorder?

> Distinguish between “recurrence” and

“relapse,”

causal FAcTORs IN

‘x]POLAR Moop

pisORDERS

_paderag the development of unipolar mood disor

persion bee feed onthe pole roles of bo.

So sod sociocultural factors. Although

Sie cen Bas eal Been Tied separate at

koe gee sock! be to undentand how thes fer

factors are interrelated, in onder to

3 ppopnchosocal model,

soiogical Causal Factors

pus beg bees known that a variety of diseases and drugs

EBE= mood keading somtimes to depresion and

Boo daton or even bypomania Indeed, this idea

‘Shes w Hippocrates. who hypothesized that depres.

BB ssaassed by an cxcess of “black hile" in the system

spose As we will discuss, in the past half-century

szempting to establish a biological bass for

Sree cecrdess have considered a wide range of factors.

¢

GexETKC INFLUENCES Farsi studies have shown that

Sipsuence of mood disorders is approximately three

Sather emong blood relatives of persons with clini-

Sspesed unipolar depression than in the popula-

z= = ie (eg. Sullivan, Neale, & Kendler, 2000;

"ele Scineider, & McGuifin, 2002). More importantly,

tere: i mudies, which can provide much more con-

— netic influences on 2 disorder, also,

=e. “contribution to unipolar \

‘twin: Sollivan et al (2000) did a quantitative review —

Ftestin studies (the tral numberof tins sud

‘= sazorer 21,000) and found that monozygotic co-twins

¢apei with unipolar major depression ase about tice,

Bdywadevelop majordepressionas ( 7.) —W2-/.

seEzpticco-twins Averagingacross | 7

‘eral of these studies, this review

‘sags that about 31 to 42 percent

“fe variance in lability to major

‘ration was due to genetic influ-

‘adoption method

Canal Factors in Unipolar Mot Disorders

tion studies on mood disorders published thus far, the

most adequate one (Wender etal, 1986) found that wnipe~

lar depression nccttied about seven-timesmore offen in

EBs iwesof-the severely depressed adoptees

than in the biological relatives of control adoptees (Wal-

lace et a 2002; Wender etal, 1986).

Taken together, the results from family, twin, and

adoption studies make a steongcase for amoderategenctis

sal patterns of-unipolar major,

ution as

for bipolar disorder (Farmer Eley. Met

lace etal, 2002), However, the evidence for a genetic con=

tribution is much less consistent for milder but chronic

forms of unipolar depression such as dysthymia, with

some studies finding no evidence of genetic contributions

(Roth & Mountjoy, 1997; Wallace et al, 2002), Finally

attempts tg identify specifi genes that may be responsible

for these genetic luences have not yt been success

although there are some promising leads (Plomin et aly

2001; Wallace et al, 2002).

gene involved in the trans

toni, which is one ofthe key neurotransmitters involved

in depression, There are two different kinds of versions or

alleles involwed—the short allele (5) and the tong allele (Dy

and people have two short alleles (5s), two long alleles (12),

oF onc of each (sl). Prior work with animals had suggested

that having ssalleles might predispose to depression rela~

tive to having alleles, but human work on this iste had

provided mixed results. In 2003, Caspi, Sugden, Mofit,

and colleagues published a landmark study in which they

tested for the possibilty ofa gene-environn

involving this erotonin-transporter gene (see Chapter 3).

‘They used 847 people in New Zealand who had been fol-

lowed fom birth until 26 years of age, at which time the

researchers assessed diagnoses of major depression in the

past year, and the occurrence of stressful life events in the

previous 5 years. Their results were very

Hiking: fadviduals who possesed the

ssalleles Were twice as likely to develop

lepression following four ér more stress-

ful life events in the past 5 years as those

Who possessed the Ilalleles and had four

interaction

‘=e The estimate was even higher for

‘bac serere, recurrent depressions.

‘Scubly however, the same review con-

ued that even more variance in the

‘SSiey to major depression is due to

‘

interact with other disturbed hormonal and nexroptrs

logical patterns and biological ripthms (2. Gaiow

Nemeroff, 2003).An interesting new focus of some o>

Fewearch is on understanding how interactocs <=

these different neurobiological stems ax EOE

resilience in the face of major stress (a very comico

Gipitant for depreuion}, which in num may bee Fo

why only a suet of people undersoing mice

depression (Southwick et al 2005).

MAUTIES OF HORMONAL REGULAT:

hormonal causes or correlates of some for

rater i ss a

10044 aly 2002). The tnajority of attention has bec,

jon the ypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) aie

‘p particular on the hormone which is

2% gel bythe outermost portion ofthe adrenal glands

aig regulated through 9 complex feedback loop (ace

we! in Chapter 3 68 Howland & Thase, 1990). As

Fie yedin Chapters 3,5,and 6 the human stress response

Sociated with clevated activity of the HDA axis, which

ly controlled by horepinephrine and serotonin. The

n of stress or threat can lead to norepinephrine

re :

ity inthe hypothalamus, causing the release of conte

Sossamon CRE fo thel poe

Srvbich in turn triggers release of adrenocorticatrophie

pomane (ACTH) from the pituitary. The ACTH then typ=

JAllrtravels through the blood to the adrenal cortex of the.»

‘areal gands where etal is released. Blood plasiita

els of cortisol are known to be elevated in som to 40 ~

Fit of severely depressed hospitalized patients (Thase

al, 2002). Sustained elevations in cortisol can result

from increased CRH activation (for example, during sus-

no8!

i

isp

‘Causal Factors in Unipolar Mood Disorders

tained stress or threat), increased secretion of ACTH, oF

the failure of feedback mechanisms. See Figure 7.2.

‘One line of evidence that implicates the failure of

feedback mechanisms in some depressed patients comes

from robust findings that in about 45 percent of seriously

depressed patients, a potent suppressor of plasma cortisol

in normal individuals, dexamethasone, either fails entirely

to suppress cortisol or fails to sustain its suppression

(Thase et al., 2002). This means that the HPA axis is not

‘operating properly in these “dexamethasone nonsuppres-

sors” It was initially thought that DST nonsuppressor

Patients constituted a distinct subgroup of people with

severe or melancholic depression (Holsboer, 1992). How-

ever, subsequent research showed that several other groups

of psychiatric patients, such as those with panic disorder,

also exhibit high rates of nonsuppression. This suggests

that nonsuppression may merely be a nonspecific indica-

tor of generalized mental distress.

Recent findings have revealed that depressed patients

with elevated cortisol also tend to show memory impair-

‘ments and problems with abstract thinking and complex

problem solving (Belanoff et al., 2001). Some of these

cognitive problems may be related to other findings

showing that prolonged elevations in cortisol such as seen

in moderate to severe depression result in cell death in the

Patient with Major Depression

Other

regulatory

factors

Normal Subject

Other

regulatory

FIGURE 7.2

Response to Stress in a Normal

Subject and a Patient with Major

Depressive Disorder

In normal subjects and in patients with

‘major depression, periods of stress are

‘typically associated with increased

levels of both cortisol and carticotropin-

releasing factor. Corticotropin-releasing

{actor stimulates the production of

corticotropin, which in turn stimulates

the production of cortisol. Cortsal

Inhibits the release of corticotropin from

the pituitary and the release of -

Whatis the role of stressful life events in

inipolar depression, and what kinds of

datheses have been proposed to interact

vith them?

> Descibe the following theories of depression:

Beck's cognitive theory, the helplessness and

ss theories, and interpersonal

\BIPOLAR DISORDERS

‘plr disorders are distinguished from unipolar disorders

‘nthe presence of manic or hypomanic symptoms. A pet-

‘a who experiences a manic episode has a markedly cle~

‘ed, cuphoric,and expansive mood, often interrupted by

fis outbursts of intense irritability oF even ve>

particularly when others refuse to go along with

bipolar Disorders

person's wishes and schemes. These extreme

‘moods must persis for at least a week for this diagnosis 10

bbe made, In addition, three or more additional symptoms

must occur inthe same time period. There must ako be

significant impairment of occupational ancl social func

sind. hospitalization is often necessary during

manic episodes.

In milder forms, st

10 a diagnosis of hypon

experiences abnormally elev

‘mood for at least 4 days. In addi

at least three other symptoms simi

mania but to a lesser degree (cf inflated self-esteem,

decreased need for sleep lights of ideas, pressured speech,

etc.) Although the symptoms listed are the same for manic

and hypomanic episodes, there is much less impairment in

social and occupational functioning in hypomania, and

hospitalization is not required.

1 kinds of symptoms can lead

nic episode, in which a person

rated, expansive, of irritable

n,the person must have

lar to those involved in

Cyclothymic Disorder

It has tong been recognized that some people ae subject

to cyclic mood changes les severe than the mood

SSvngs see in bipolar disorder These are the symptoms

Of the disorder known as eyeothymic disorder. In

DSM-iv-TR, eyclothymia is defined asa less serious ver~

Sion of major bipolar disorder, minus certain extreme

Symptom and payehotie features, such as delusions, and

aimee the marked ‘impairment caused. by fallblown

tmanie or major depresive episodes.

Inthe depressed phase of eyclothymic disordes a per-

sons mood iusjsted an he o sh experiencesa dstinet

loss of interest or pleasure in customary activities and pas-

times n aio the person may show other symptoms

Aah as Tow energy, feelings of inadequacy, socal with-

tawal and » pessimistic, brooding atitude. Essential

the symptoms are similar to those in someone with dys-

thymfa except without the duration criterion

Symptoms of the hypomanic phase of cyclothymia

arecatentally the opposite of the symptoms of d)sthymia.

Inthis phase ofthe disorder, the person may become espe

Gilly creative and productive because of increased phy

Gal and mental energy. There may be significant pes

treween episodes in which the person vith eyelothyi

functions ina elatively adaptive manner. For a diagnosis

(feyelothymia, there mast beat least a 2-year span during

sihigh there are numerous periods with hypomanic and

depressed symptoms (1 year for adolescents and. ch

deen) and the symptoms must cause clinlly significant

istres or Impairment in functioning (although not as

Severe ain bipolar disorder). (Sethe DSM-IV-TR table,

Giteria for Cyelothymic Divorder) Because individuals

with epelothymia ate a increased tisk of later developing

full-biown bipolar disorder (eg Akiskal & Pinto, 1999),

DSM-IV-TR recommend that they be treated

“The following case illustrates cylothymia.

1253

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- epqDocument9 pagesepqSazia BegumNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan Apr 30, 2023Document19 pagesAdobe Scan Apr 30, 2023Sazia BegumNo ratings yet

- PersonalityDocument5 pagesPersonalitySazia BegumNo ratings yet

- DAT VR ReportDocument2 pagesDAT VR ReportSazia BegumNo ratings yet

- SocialMediaandYoungPeopleEmotion JMIW2019Document16 pagesSocialMediaandYoungPeopleEmotion JMIW2019Sazia BegumNo ratings yet

- Professional Make-Up CourseDocument9 pagesProfessional Make-Up CourseSazia BegumNo ratings yet

- New Doc 2023-03-28 12.10.05Document2 pagesNew Doc 2023-03-28 12.10.05Sazia BegumNo ratings yet

- DocScanner 18-May-2023 4-37 PMDocument5 pagesDocScanner 18-May-2023 4-37 PMSazia BegumNo ratings yet

- Scientific Information System: Network of Scientific Journals From Latin America, The Caribbean, Spain and PortugalDocument9 pagesScientific Information System: Network of Scientific Journals From Latin America, The Caribbean, Spain and PortugalSazia BegumNo ratings yet

- Family Pathology ScaleDocument4 pagesFamily Pathology ScaleSazia BegumNo ratings yet

- Assignment-1 Sazia BegumDocument4 pagesAssignment-1 Sazia BegumSazia BegumNo ratings yet