Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Compracion TX Parkland en Adultos

Compracion TX Parkland en Adultos

Uploaded by

morena19932308Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Compracion TX Parkland en Adultos

Compracion TX Parkland en Adultos

Uploaded by

morena19932308Copyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Original article

Comparison of three techniques using the Parkland

Formula to aid fluid resuscitation in adult burns

Abrie Theron,1 Owen Bodger,2 David Williams3

1

Department of Anaesthetics, ABSTRACT (or nomographs) are one such form of graphical

Cardiff & Vale University Local We performed a randomised study to compare the representation, in which the user typically aligns a

Health Board, Cardiff, UK

2

School of Medicine, Swansea

accuracy and speed of three different techniques ( pen straight edge (‘isopleth’) between two graduated

University, Swansea, UK and paper, electronic calculator and a novel graphic scales at points corresponding to the values of the

3

Department of Anaesthetics, device: ‘nomogram’) for calculation of resuscitation fluid input variables, and reads the value of the output

Welsh Centre for Burns, ABM requirements for adults in the first 24 h of burn injury, variable where the isopleth intersects a third scale.8

University Local Health Board, based on the Parkland Formula. We also assessed Prior to the introduction of electronic calculators

Swansea, UK

acceptability of each technique using visual analogue and computers, nomograms were widely used to

Correspondence to scores and qualitative analysis of free text responses. 28 rapidly solve specific mathematical equations in

Dr Abrie Theron, Department participants performed 252 calculations using a series of engineering and in medicine, and are still routinely

of Anaesthetics, Cardiff & Vale computer generated simulated patient data. For used in safety-critical industries, such as aviation,

University Local Health Board,

Cardiff CF14 4XW, UK; nomogram, electronic calculator, pen and paper: to cross-check results calculated by electronic

drabrietheron@yahoo.co.uk Magnitude of error [low (≥25%), medium (≥50%), high means.9 10 In the field of burns management, nomo-

(≥75%)]: [6.0%, 1.2%, 0%], [17.9%, 14.3%, 8.3%], grams have been designed to calculate burn surface

Received 26 March 2013 [25%, 16.7%, 9.5%]; p<0.002. Calculation time: [sec: area and estimate carbon monoxide exposure.11 12

Revised 28 May 2013

Accepted 1 June 2013

mean (SD)]: 94(34), 73(31), 214(103); p<0.001. The Williams has designed a compound parallel scale

Published Online First mean (SD) of the difficulty scores for each method were alignment nomogram (figure 1) based on the

22 June 2013 23(17), 17(14) and 70(21) out of 100. Of the 28 Parkland Formula for the calculation of fluid

participants 15 preferred the calculator, 12 preferred the requirement in adults during the first 24 h postburn

nomogram and 1 scored the calculator and nomogram injury.13 Standard algebraic methods were used for

equally (table 3). The nomogram was significantly more construction, aided by a spreadsheet (Excel,

accurate at all levels, almost as fast as an electronic Microsoft, Redmond, Washington), and graphics

calculator, and deemed easy to use. It is low cost and software (Rhinoceros3D, McNeel North America,

robust, and provides a rapid means of detecting and Seattle, Washington; Illustrator, Adobe Systems, San

preventing the large errors that we have shown can Jose, California).14 The method of use is shown in

occur when an electronic device is used as the only figure 2.

method of calculation. We therefore suggest that the

Parkland Formula nomogram is a suitable method for METHOD

calculation of resuscitation fluid requirements in adult The study was a randomised volunteer study to

burns. Fluid requirement should, however, be reviewed compare accuracy and response time for calculation

frequently, and adjusted to ensure adequate organ of resuscitation fluids from the Parkland Formula

perfusion. using calculator, pen and paper and nomogram

methods. The null hypothesis was that ‘there is no

difference in accuracy or speed of calculation when

BACKGROUND comparing the three methods’. The study was anon-

Inadequate fluid resuscitation of acute burns may ymised and non-clinical, therefore, no formal ethics

result in hypovolaemic shock and inadequate perfu- or research committee approval was required.

sion of vital organs resulting in single to multiorgan Appropriate letters of exemption were obtained

failure and Systemic Inflammatory Response from our Trust’s research coordinator and ethics

Syndrome (SIRS).1 Excessive fluid resuscitation committee.

may result in fluid overload causing myocardial Power analysis was informed by a review of a

infarction, abdominal compartment syndrome and comparable study;15 and a pilot study in which 11

burn depth conversion with increased requirement participants performed 99 calculations using all

for escharotomies, fasciotomies and grafts.2 three techniques. Moderate errors (≥50%)

The original Parkland Formula is the most occurred in 12.1% and 0.0% of calculations with

widely used formula worldwide to guide early fluid the calculator and nomogram, respectively. For a

resuscitation in burns.3 It is a good starting point; superiority test with 90% power and 5% error rate,

however, fluid administration should ultimately be this suggested a sample size of 76 calculations for

titrated to clinical signs of adequate organ perfu- each of the three techniques.

sion, as inferred from urine output of 0.5–1.0 mL/ If each participant performed too few calcula-

kg/h and mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) of tions, the data would not be representative; but too

around 70 mm Hg.1 2 4–7 many calculations could result in declining per-

To cite: Theron A, Most mathematical relationships, including burns formance due to fatigue. We therefore decided an

Bodger O, Williams D. fluid resuscitation formulae, can be expressed in acceptable compromise would be a total of nine

Emerg Med J 2014;31: algebraic or graphic form; and the two forms can be calculations per participant—that is, three using

730–735. interconverted using analytic geometry. Nomograms each of the 3 methods.

730 Theron A, et al. Emerg Med J 2014;31:730–735. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202652

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Original article

Figure 1 The improved Parkland Formula nomogram for adult burns (after:13).

The 28 participants (12 of whom were consultants) included than speed of calculation. During the study, participants were

22 anaesthetists, 5 plastic surgeons and one band 6 nurse. Only allowed to refer to printed copies of the Parkland Formula, its

three participants had no prior experience of using the Parkland method of use and instructions for the use of the nomogram.

Formula. Following full explanation and informed consent, par- Bespoke software was developed for this study using Python,

ticipants signed a consent form and completed an anonymised an open-source, cross-platform, object-oriented, programming

demographic data collection form which recorded their age, language, particularly suited to scientific applications.16 The

gender, job title and prior experience in using the Parkland software created a total of nine scenarios for each participant

Formula. with three scenarios for each of the three calculation techniques.

All subjects then received instruction on how to use the The software randomly assigned the sequence that dictated the

Parkland Formula, how to calculate the Volume To Be Infused calculation technique to be used for each scenario. For each

(VTBI) per period (mL) and the appropriate rate of administra- simulated scenario, the software randomly generated a new set

tion of resuscitation fluids per period (mL/h), using each of the of integer values within appropriate ranges for BWt (40–

three methods. It was emphasised that the time of the first (8 h) 150 kg), Total Burn Surface Area (TBSA) (10–100%) and Delay

period of resuscitation commenced from the time of the burn (1–8 h), and calculated the correct answers for the fluid infusion

injury, not from the time of arrival at the receiving hospital, and rates (mL/h) in each resuscitation period.

participants were shown how to adjust the calculations in each The software instructed the participant on which technique

case to compensate for this. to use for each scenario. Time was allowed for the participant

Many participants were not familiar with the use of the iso- to prepare the appropriate equipment and printed materials to

pleth, and logarithmic scales used on the nomogram and the perform the calculation. When the participant pressed the ‘start’

method of reading and interpolating values was explained. key, they were presented with the set of values from which to

Participants had unlimited opportunity to practice each method calculate the correct fluid infusion rates in each period. At the

and did not proceed until they felt confident to perform the cal- same time a software-based timer automatically started. When

culations with all three methods. the participant had entered all the fluid infusion rates, the timer

Participants were instructed to perform the calculations as automatically stopped and the participant’s responses and

quickly as possible to a level of ‘clinically acceptable’ accuracy; response time were stored. Participants were allowed to rest

however, it was emphasised that accuracy was more important between scenarios if necessary without incurring a time penalty.

Theron A, et al. Emerg Med J 2014;31:730–735. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202652 731

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Original article

Figure 2 Example of how to use the Parkland Formula nomogram for adult burns.

When each scenario was completed, the software compiled all significance. We therefore defined three thresholds of error—25,

data (including calculation technique used, values of all ran- 50 and 75%—representing categories of low, medium and high

domly generated parameters, correct answers, participant’s clinical significance as a proportion of the correct solution. The

responses, and response times) and saved it to a spreadsheet for accuracy of each method was calculated across all three thresh-

subsequent analysis. olds using a non-parametric test (χ2 test of association).

Participants then completed a post-test questionnaire. This The data for response times was skewed; however, a log trans-

consisted of a series of continuous visual analogue scales (VAS, form of this data was accepted by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov

graphic rating scales); where they were instructed to mark a goodness-of-fit test (p=0.433) and, therefore, a parametric test

cross at the appropriate point on a line which ranged from ‘very analysis of variance (ANOVA) was appropriate. Demographic data

easy’ to ‘very difficult’ to describe their experience of ease of were mainly categorical and were therefore analysed using either

use for each of the three techniques. There was also an optional ANOVA or a two-way χ2 test. The VAS scores comprised too small

section for free text entry of written comments. a sample (only 28 unique cases) to allow reliable assessment of dis-

Information from the pre-test and post-test questionnaires tribution, and so non-parametric methods were used for analysis.

was transcribed onto a spreadsheet for subsequent analysis. Data

from the VAS were converted to continuous numerical data by

measuring the distance (mm) from the left hand side of the line

to the position of the cross marked by the participant, expressed

Table 1 Common sources of potential error associated with the

as a proportion of the total length of the line.

Parkland Formula

Variable Potential error (±) (%)

ANALYSIS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, V.13 (SPSS, Estimation of body weight 10

Chicago, Illinois) was used to aid analysis of data. Estimation of TBSA 20,7

The Parkland Formula requires several measurements as Variation in Volume To Be Infused (VTBI) depending 14 (ie, 3.5±0.5 mL/

input, each of which must be estimated. The expected errors for on which version of Parkland Formula is used: h=0.5/3.5=14%)

each of these variables are not trivial (table 1). Combining these VTBI=4 mL/BWt(kg)/%TBSA or

VTBI=3 mL/BWt(kg)/%TBSA

using the sum of squared fractional errors gives an expected

Estimation of the time elapsed between the time of 10

error of around 28% in the final answer.17 Given that this is the

burn injury and the start of fluid resuscitation

size of error that is likely to occur irrespective of the quality of

TBSA, total burn surface area.

the calculation, then it must represent the lower end of clinical

732 Theron A, et al. Emerg Med J 2014;31:730–735. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202652

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Original article

association demonstrated significant differences between the

Table 2 Likelihood ratio test results

accuracy of the three methods for all thresholds, with p values

Comparison 25% error 50% error 75% error of 0.003, 0.002 and 0.018 for 25, 50 and 75% errors (table 2).

The calculator performed no better than pen and paper for any

Calculator vs nomogram 0.017* 0.001** 0.007**

of the thresholds, and the nomogram was superior to both these

Calculator vs pen & paper 0.259 0.670 0.787

techniques.

Nomogram vs pen & paper 0.001** <0.001*** 0.004**

The response time for each of the three methods of calcula-

Overall 0.003** 0.002** 0.018*

tion was significantly different from the other two ( posthoc

*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, ***=p<0.001. ANOVA: p<0.001). The calculator was the fastest method, fol-

lowed by the nomogram, and then pen and paper, with mean

times (SD) of 73 (31), 94 (34) and 214 (103) seconds, respect-

The free text comments from the post-test questionnaire were ively. There was considerable overlap between the response

analysed using an iterative constant comparison (‘grounded’) times for the nomogram and calculator, although only two indi-

approach to allow identification and classification of emerging vidual subjects were able to use the nomogram faster than the

themes.18 Specific comments which illustrated a particular point calculator (figure 3).

of view, or that were representative of common themes, were All three methods showed evidence of improvement of

quoted verbatim in anonymised form. response time with repetition—that is, a learning effect. This

was strongest for the nomogram, reflecting its novelty

RESULTS (p<0.001, p<0.001 and p=0.001 for calculator, nomogram

Only around 84% of all calculations were free from error; and pen and paper, respectively). Between the first and third

defined as at least 25% of proportion of the correct answer. attempts, the mean additional time required to use the nomo-

Errors occurred during calculation of both the rate for the first gram compared with the calculator fell from 27 s (or 29%) to

and the second period for all methods, however, the number of 14 s (23%) (figure 4).

errors was not large enough to demonstrate any significant rela- The VAS scores showed that some participants had a strong

tionship between the method used (calculator, nomogram, pen preference for the nomogram, while others strongly preferred

and paper) and the stage of calculation (rate for first and second the calculator. The calculator was generally considered easier to

period) during which the errors occurred. use, but the difference was not statistically significant under a

The best performing technique at each level was the nomo- Wilcoxon-signed rank test. No participant reported finding

gram, making errors of low significance (≥25%), medium sig- these two methods very difficult. The mean (SD) of the diffi-

nificance (≥50%), and high significance (≥75%), respectively, culty scores for each method were 17% (14), 23% (17) and

6.0, 1.2 and 0% of the time, compared with 17.9, 14.3 and 70% (21) for calculator, nomogram and pen and paper techni-

8.3% for the calculator, and 25, 16.7 and 9.5% for the pen and ques, respectively (table 3). Of the 28 participants, 15 preferred

paper technique. A comparison of the frequency of occurrence the calculator, 12 preferred the nomogram and 1 scored calcula-

of errors with the three different methods using the χ2 test of tor and nomogram equally. Univariate statistical analysis showed

Figure 3 Histogram of response times for calculator, nomogram and pen and paper techniques.

Theron A, et al. Emerg Med J 2014;31:730–735. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202652 733

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Original article

individuals and ambient lighting conditions. A further advantage

of the monochrome chart is that it may be readily photocopied.

Concerns included that the nomogram was ‘not particularly

intuitive’ (1), and that scale markings could be obscured by an

opaque isopleth (1). A transparent straight edge was used, but

the problem persisted due to refraction; therefore, a transparent

polycarbonate isopleth with a central hairline graticule was con-

structed which we will use in future studies.

DISCUSSION

The software developed for this study worked efficiently with

no problems. The randomisation prevented bias due to learning

effects or fatigue. The use of automated timing eliminated any

potential observer error. Both participants and investigators

were blinded to the correct results of the calculations and

response time to prevent bias. The nomogram was designed

using the original Parkland Formula which is based on a VTBI

of 4 mL/BWt(kg)/TBSA (%); however, it would be an easy

matter to redraft this as necessary to incorporate a new or

Figure 4 Plots of mean response time against attempt for each of amended formula.

the three methods of calculation.

Various systems have been designed to aid calculation of

resuscitation fluid requirements based on the Parkland Formula

no significant correlation between any of the demographic vari- including: dedicated electronic devices,19 computer software,20

ables studied and any of the outcome measures (accuracy, speed, tables21 and mechanical calculators.22 Compared with these,

user preference). nomograms are low cost, durable (if printed on plastic slates or

Twenty-five of the 28 participants submitted free text responses, waterproof paper), maintenance-free and have no moving parts.

with each response containing 1–3 discrete items. Qualitative ana- Nomograms may be printed on paper with a copy of the Lund

lysis identified three main themes (in italics), with representative and Browder chart on the reverse,23 and filed in patient notes to

comments and number of responses in parentheses. provide a permanent record of the calculation.

Acceptability: Many respondents (10) remarked that the In contrast with the nomogram, many of the above systems

nomogram was easy to use. Some (2) felt that it was easier to are unable to correct the calculation for the time of burn and

use than a calculator, particularly ‘in a resuscitation situation’. for preadmission fluids, and give the result as a total volume of

Three participants noted that the nomogram soon became fluid per resuscitation period (mL) rather than a rate of infusion

quicker and easier to use after a little practice. No participants (mL/h). They are, therefore, of limited use in practice.

expressed any difficulties interpreting and interpolating the loga- Nomograms are easy to read and provide continuous values

rithmic scales. across the entire range: tables may be difficult to read and the

Suggestions for improvement included omission of the scale discrete values can introduce rounding errors. The use of loga-

showing infusion rate in giving set drops per minute as it could rithmic scales ensures that the accuracy of the nomogram is

potentially be confused with the infusion rate in mL/h (2), greater at the more clinically significant lower range.

improving legibility by using a larger format (4), different scale Electronic calculators and computers may not be readily avail-

graduations (3) and colour coding (1). We incorporated a ‘drops able and require a reliable electrical power supply. By nature of

per minute’ scale for infusion rate because we anticipate use of its design, the nomogram is an approximate method of calcula-

the nomogram where volumetric infusion devices may not be tion compared with electronic devices, however, the nomogram

readily available. Omitting this scale may aid clarity. Larger incorporates the Parkland Formula into its design and constrains

formats offer marginal gains in accuracy at the expense of port- both the input variables and output to a clinically relevant range

ability. In practice, the degree of accuracy from the A4 format of values, and is therefore incapable of producing the

was found to be adequate for clinical purposes. Colour coding unbounded errors that arise due to misapplication of the

is attractive; however, colour perception varies between formula or unrecognised keystroke errors on data entry which

have been shown to occur in 4% of key presses.24

The importance of cross-checking dosage calculations of

drugs and fluids by two individuals using two different methods

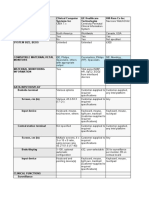

Table 3 Summary of results has been recently emphasised.25 Safety-critical calculations in

the aviation and diving industries are routinely verified using

Magnitude of error Difficulty both electronic and graphic techniques.10 If an electronic device

Calculation scores

Low % Medium % High % time (mean (mean is used as the primary method of calculation for resuscitation

Method (≥25%) (≥50%) (≥75%) (SD)) (SD)) (%) fluids in acute burn injuries, the nomogram can be used to

rapidly cross-check the calculation and prevent patients coming

Nomogram 6.0 1.2 0 94 (34) 23 (17) to harm due to the effects of overtransfusion or undertransfu-

Calculator 17.9 14.3 8.3 73 (31) 17 (14) sion. The nomogram gives a clear visual expression of the rela-

Pen & 25 16.7 9.5 214 (103) 70 (21) tionships between the variables. It is simple to confirm correct

Paper

entry of data by performing the calculation in reverse graphic-

p=0.003 p=0.002 p=0.018 p<0.001

ally. This would be difficult to do algebraically or using the

systems described above.

734 Theron A, et al. Emerg Med J 2014;31:730–735. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202652

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Original article

CONCLUSIONS 4 Mitra B, Fitzgerald M, Cameron P, et al. Fluid resuscitation in major burns. ANZ J

The nomogram method for calculation of adult fluid resuscita- Surg 2006;76:35–8.

5 Fodor L, Fodor A, Ramon Y, et al. Controversies in fluid resuscitation for burn

tion requirements by the Parkland Formula was more accurate management: literature review and our experience. Injury 2006;37:374–9.

and faster than pen and paper calculations. By comparison with 6 Berger M, Bernath M-A, Chiolero R. Resuscitation, anaesthesia and analgesia of the

an electronic calculator, the nomogram resulted in fewer and burned patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2001;14:431–5.

less extreme errors, was only slightly slower, and did not 7 Collis N, Smith G, Fenton O. Accuracy of burn size estimation and subsequent fluid

resuscitation prior to arrival at the Yorkshire Regional Burns Unit. A three year

present the disadvantages associated with electronic devices as

retrospective study. Burns 1999;25:345–51.

described above. The majority of participants found the nomo- 8 d’Ocagne M. Traite de Nomographie. 1st ed. Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1899.

gram intuitive, easy to use and accuracy and speed further 9 Boothby W, Sandiford R. Nomographic charts for the calculation of the metabolic

improved with practice. rate by the Gasometer method. Boston Med and Surg J 1921;185:337–54.

We therefore propose that with appropriate instruction, the 10 Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Aviation Research & Analysis Report AR-2009–

052: Take-off Performance Calculation and Entry Errors: A Global Perspective In:

nomogram is a suitable means of calculating initial resuscitation Australian Government, editor: ATSB, 2009.

fluid requirements in adult burns. Ultimately, fluid resuscitation 11 Clark C, Campbell D, Reid W. Blood carboxyhaemoglobin levels in fire survivors.

should be titrated to the patient’s clinical response, aiming for Lancet 1981;i:1332.

adequate organ and tissue perfusion, as inferred from urine 12 Malic C, Karoo R, Austin O, et al. Resuscitation burns card—a useful tool for burn

injury assessment. Burns 2007;33:195–9.

output and other physiological parameters (eg, MABP). As a

13 Williams D. Nomograms to aid fluid resuscitation in acute burns. Burns

primary means of calculation the nomogram would be particu- 2011;37:543–5.

larly useful for clinicians with limited experience of burns (eg, in 14 Hoelscher R, Arnold J, Pierce S. Alignment charts. Graphic aids in engineering

a district general hospital and emergency department) or for computation. 1st ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1952:62–117.

those working in difficult environments, or developing countries. 15 Lindford A, Lim P, Klass B, et al. Resuscitation tables: a useful tool in calculating

pre-burns unit fluid requirements. Emerg Med J 2009;26:245–9.

If an electronic device is used as the primary means of calcula- 16 Langtangen H, ed. A primer on scientific programming with Python. London:

tion, the nomogram offers a rapid means of checking for errors. Springer, 2009.

17 Taylor J. An introduction to error analysis: the study of uncertainties in physical

Contributors DW developed the nomograms, graticule and software. AT collected measurements. Herndon, VA: University Science, 1982.

the data. OB performed the power calculations and statistical analysis and 18 Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for

presentation of data. All three authors designed the study and contributed to the developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008.

writing and review of this article. 19 Dingley J, Williams D. A hand-held electronic device to calculate fluid requirements

Competing interests None. for burns. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010;27:192–3.

20 Milner S, Smith C. Palm-top computer application for fluid resuscitation in burns.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2001;108:1838–9.

21 de Mello W, Greenwood N. The burns fluid grid. A pre-hospital guide to fluid

resuscitation in burns. J R Army Med Corps 2009;155:27–9.

22 Jenkinson L. Fluid replacement in burns: a burns calculator. Ann R Coll Surg Eng

REFERENCES 1982;64:336–8.

1 Holm C. Resuscitation in shock associated with burns. Tradition or evidence-based 23 Lund C, Browder N. The estimation of areas of burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet

medicine? (review). Resuscitation 2000;44:157–64. 1944;79:352–8.

2 Sjöberg F. The ‘Parkland protocol’ for early fluid resuscitation of burns: too little, 24 Number entry interfaces and their effects on errors and number perception. IFIP

too much or…even…too late…? Acta Anesthesiol Scand 2008;52:752–6. Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Interact 2011, 2011.

3 Baxter C, Shires T. Physiological response to crystalloid resuscitation of severe burns. 25 Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Fluorouacil incident root cause analysis.

Annals of the N Y Acad Sci 1968;150:874–94. Canada: ISMP, 2007.

Theron A, et al. Emerg Med J 2014;31:730–735. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202652 735

Downloaded from emj.bmj.com on September 14, 2014 - Published by group.bmj.com

Comparison of three techniques using the

Parkland Formula to aid fluid resuscitation

in adult burns

Abrie Theron, Owen Bodger and David Williams

Emerg Med J 2014 31: 730-735 originally published online June 22,

2013

doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202652

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://emj.bmj.com/content/31/9/730.full.html

These include:

References This article cites 16 articles, 2 of which can be accessed free at:

http://emj.bmj.com/content/31/9/730.full.html#ref-list-1

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in

service the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Topic Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections

Collections

Resuscitation (548 articles)

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- William Blakes Illustrations For Dantes Divine ComedyDocument298 pagesWilliam Blakes Illustrations For Dantes Divine Comedyraul100% (3)

- Comparison of Three Techniques For Calculation of The Parkland Formula To Aid Fluid Resuscitation in Paediatric BurnsDocument9 pagesComparison of Three Techniques For Calculation of The Parkland Formula To Aid Fluid Resuscitation in Paediatric Burnseset5No ratings yet

- 0142Document10 pages0142Sara ScarletNo ratings yet

- Using A Deep Learning Algorithm and Integrated Gradients Explanation To Assist Grading For Diabetic RetinopathyDocument13 pagesUsing A Deep Learning Algorithm and Integrated Gradients Explanation To Assist Grading For Diabetic RetinopathyMitcheel Lanas SozaNo ratings yet

- Mortality Risk Score Prediction in An Elderly Population Using Machine LearningDocument10 pagesMortality Risk Score Prediction in An Elderly Population Using Machine LearningRie TsuboiNo ratings yet

- Predicting Coronary Heart Disease Using An Improved LightGBM Model Performance Analysis and ComparisonDocument15 pagesPredicting Coronary Heart Disease Using An Improved LightGBM Model Performance Analysis and ComparisonDiamondNo ratings yet

- Metabric Dataset Surv Analysis Gradient BoostingDocument9 pagesMetabric Dataset Surv Analysis Gradient BoostingKeren Evangeline. INo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Computer Methods and Programs in BiomedicineDocument30 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Computer Methods and Programs in BiomedicineJuan Esteban VanegasNo ratings yet

- Automated Chest Screening Based On A Hybrid Model of Transfer Learning and Convolutional Sparse Denoising AutoencoderDocument19 pagesAutomated Chest Screening Based On A Hybrid Model of Transfer Learning and Convolutional Sparse Denoising AutoencoderAlejandro De Jesus Romo RosalesNo ratings yet

- 1548 6066 1 PBDocument10 pages1548 6066 1 PBOun VikrethNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Three Methods of CausalityDocument5 pagesComparison of Three Methods of Causalitywinda kiranaNo ratings yet

- Singapore Research 2008Document11 pagesSingapore Research 2008Jean AntoineNo ratings yet

- 551Document7 pages551dilkulNo ratings yet

- Type and Accuracy of Sphygmomanometers in Primary Care:: ResearchDocument6 pagesType and Accuracy of Sphygmomanometers in Primary Care:: ResearchKhaulla KarimaNo ratings yet

- Dicentric Telescoring As A Tool To Increase The Biological Dosimetry Response Capability During Emergency SituationDocument11 pagesDicentric Telescoring As A Tool To Increase The Biological Dosimetry Response Capability During Emergency SituationchamomilaNo ratings yet

- Topics 11 and 21 HL Measurement and Data ProcessingDocument23 pagesTopics 11 and 21 HL Measurement and Data ProcessingDuddlie YuNo ratings yet

- Antlion Re-Sampling Based Deep Neural Network Model For Classification of Imbalanced Multimodal Stroke DatasetDocument25 pagesAntlion Re-Sampling Based Deep Neural Network Model For Classification of Imbalanced Multimodal Stroke DatasetShahab KarimNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Prediction of Heart Disease Using A Combination of Machine Learning and Deep LearningDocument11 pagesResearch Article: Prediction of Heart Disease Using A Combination of Machine Learning and Deep LearningTesta MestaNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Heart Disease Prediction Based On The Embedded Feature Selection Method and Deep Neural NetworkDocument9 pagesResearch Article: Heart Disease Prediction Based On The Embedded Feature Selection Method and Deep Neural NetworkHADIS FEIZINo ratings yet

- SirishKaushik2020 Chapter PneumoniaDetectionUsingConvoluDocument14 pagesSirishKaushik2020 Chapter PneumoniaDetectionUsingConvoluMatiqul IslamNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Automated Quantification of Pneumothorax in CTDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Automated Quantification of Pneumothorax in CTAnnisa HidayatiNo ratings yet

- Primary Mass Casualty Incident Triage: Evidence For The Benefit of Yearly Brief Re-Training From A Simulation StudyDocument9 pagesPrimary Mass Casualty Incident Triage: Evidence For The Benefit of Yearly Brief Re-Training From A Simulation StudyAngelina PondeteNo ratings yet

- Choi 2018Document13 pagesChoi 2018Agossou Alex AgbahideNo ratings yet

- Dose Calculations For Asymmetric Fields Defined byDocument8 pagesDose Calculations For Asymmetric Fields Defined byshailanourinNo ratings yet

- Cough Event Classification by Pretrained Deep Neural NetworkDocument10 pagesCough Event Classification by Pretrained Deep Neural Networkafrica threeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument6 pagesJurnal InternasionalBerlianaNo ratings yet

- SirishKaushik2020 Chapter PneumoniaDetectionUsingConvoluDocument14 pagesSirishKaushik2020 Chapter PneumoniaDetectionUsingConvoluychennupalliNo ratings yet

- Experimental and Monte Carlo Evaluation of Eclipse Treatment Planning System For Lung Dose CalculationsDocument12 pagesExperimental and Monte Carlo Evaluation of Eclipse Treatment Planning System For Lung Dose CalculationsSenaxion AriaNo ratings yet

- Machine LearnDocument33 pagesMachine LearnEmine YILDIRIMNo ratings yet

- FullDocument14 pagesFullpannabaroi123No ratings yet

- Accuracy of Hemodialysis Modeling: M Z, J A. P, and J G - CDocument12 pagesAccuracy of Hemodialysis Modeling: M Z, J A. P, and J G - CHenry Medina CruzNo ratings yet

- 3413ijcsa05 PDFDocument13 pages3413ijcsa05 PDFVanathi AndiranNo ratings yet

- 1st Paper On Weather PredictionDocument4 pages1st Paper On Weather PredictionE SAI KRISHNANo ratings yet

- Nash Ef 2000Document5 pagesNash Ef 2000HUMBLE EXTENDEDNo ratings yet

- 152 Fullmed EmtDocument3 pages152 Fullmed EmtJamison ParfittNo ratings yet

- Neural Networks: Arlex Oscar Marín García, Markus Franziskus Müller, Kaspar Schindler, Christian RummelDocument11 pagesNeural Networks: Arlex Oscar Marín García, Markus Franziskus Müller, Kaspar Schindler, Christian RummelAki SunshinNo ratings yet

- Detecting Pneumonia Using Convolutions and Dynamic Capsule Routing For Chest X-Ray ImagesDocument30 pagesDetecting Pneumonia Using Convolutions and Dynamic Capsule Routing For Chest X-Ray ImagesShoumik MuhtasimNo ratings yet

- Shungo Imai Bs Takehiro Yamada PHD Kumiko Kasashi PHD Masaki Kobayashi PHD Ken Iseki PHDDocument7 pagesShungo Imai Bs Takehiro Yamada PHD Kumiko Kasashi PHD Masaki Kobayashi PHD Ken Iseki PHDMutiara SeptianiNo ratings yet

- Failure Mode and Effect Analysis For Three Dimensional Radiotherapy at Ain Shams University HospitalDocument13 pagesFailure Mode and Effect Analysis For Three Dimensional Radiotherapy at Ain Shams University HospitalIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Marlow 2019Document3 pagesMarlow 2019Daniel Meyer CoraciniNo ratings yet

- Lung Cancer Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Neural Network On A Conducted Survey Dataset Lung Cancer DetectionDocument4 pagesLung Cancer Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Neural Network On A Conducted Survey Dataset Lung Cancer DetectionInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- ResultadosDocument20 pagesResultadosRicardo PáscoaNo ratings yet

- Heart Disease rp5Document15 pagesHeart Disease rp5EkanshNo ratings yet

- Resmini 2017Document15 pagesResmini 2017Juan Esteban VanegasNo ratings yet

- Springer Nature LaTeX TemplateDocument15 pagesSpringer Nature LaTeX TemplateShanu NizarNo ratings yet

- Rectal Temperature-Based Death Time Estimation in Infants: Legal MedicineDocument8 pagesRectal Temperature-Based Death Time Estimation in Infants: Legal Medicinearia rizky utamiNo ratings yet

- Machine and Deep Learning For Tuberculosis Detection On Chest XDocument22 pagesMachine and Deep Learning For Tuberculosis Detection On Chest XsoloriolluisNo ratings yet

- 2019 - Detmer - Comparison of Statistical Learning Approaches For Cerebral Aneurysm Rupture AssessmentDocument10 pages2019 - Detmer - Comparison of Statistical Learning Approaches For Cerebral Aneurysm Rupture AssessmentjamonjamonjamonNo ratings yet

- Research On JournalingDocument6 pagesResearch On Journalinggraphic designerNo ratings yet

- Yeung 2021Document16 pagesYeung 2021Steffanio SebastianNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Semi-Quantitative Scoring of Gram STDocument5 pagesEvaluation of Semi-Quantitative Scoring of Gram STNurul Kamilah SadliNo ratings yet

- CNN Architecture Optimization Using Bio Inspired Algor - 2022 - Computers in BioDocument13 pagesCNN Architecture Optimization Using Bio Inspired Algor - 2022 - Computers in BioFarhan MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Imaging Reduces Failure Rates of Percutaneous Central Venous Catheterization in ChildrenDocument8 pagesUltrasound Imaging Reduces Failure Rates of Percutaneous Central Venous Catheterization in Childrenangelama1783riosNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Breast Tumor Simulation and Parameters Estimation Using Evolutionary AlgorithmsDocument7 pagesResearch Article: Breast Tumor Simulation and Parameters Estimation Using Evolutionary Algorithms29 - Heaven JosiahNo ratings yet

- Ferro 2009Document7 pagesFerro 2009Carlos RiquelmeNo ratings yet

- 2020 IC JNTUK Lalitha 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1074 012022Document11 pages2020 IC JNTUK Lalitha 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1074 012022R.V.S.LALITHANo ratings yet

- Bioconf Iscku2024 00047Document9 pagesBioconf Iscku2024 00047binepog743No ratings yet

- 2014 Drls in Mamao SydneyDocument13 pages2014 Drls in Mamao Sydneyp110054No ratings yet

- Tjcme 2011 AlDocument7 pagesTjcme 2011 Alprojects allNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Quantitative Measurements of 177lu Using SPECT/CTDocument1 pageComparison of Quantitative Measurements of 177lu Using SPECT/CTNational Physical LaboratoryNo ratings yet

- Applied Machine Learning and Multi-criteria Decision-making in HealthcareFrom EverandApplied Machine Learning and Multi-criteria Decision-making in HealthcareNo ratings yet

- MPI GTU Study Material E-Notes Introduction-To-Microprocessor 13052022114954AMDocument4 pagesMPI GTU Study Material E-Notes Introduction-To-Microprocessor 13052022114954AMKartik RamchandaniNo ratings yet

- (VigChr Supp 115) Lenka Karfíková - Grace and The Will According To Augustine 2012 PDFDocument443 pages(VigChr Supp 115) Lenka Karfíková - Grace and The Will According To Augustine 2012 PDFNovi Testamenti FiliusNo ratings yet

- Partitioning MethodsDocument3 pagesPartitioning MethodsDiyar T Alzuhairi100% (1)

- 2024 Second-Year WIL Placement LetterDocument3 pages2024 Second-Year WIL Placement LetterleticiaxolileNo ratings yet

- SEN-30201: MAX31865 RTD-to-Digital Breakout Board, Multiple Cal OptionsDocument8 pagesSEN-30201: MAX31865 RTD-to-Digital Breakout Board, Multiple Cal OptionsAchref NajjarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4-DISTRESS SIGNALSDocument22 pagesChapter 4-DISTRESS SIGNALSmendes100% (1)

- When Key Employees ClashDocument4 pagesWhen Key Employees ClashRowell DizonNo ratings yet

- 130724Document20 pages130724Caracal MohNo ratings yet

- NDDB's Golden Jubilee Coffee Table BookDocument2 pagesNDDB's Golden Jubilee Coffee Table Booksiva kumarNo ratings yet

- Buddha and His ContemporariesDocument7 pagesBuddha and His ContemporariesAlok VermaNo ratings yet

- Steps: To Personal EvangelismDocument20 pagesSteps: To Personal EvangelismDwayne Bob LerionNo ratings yet

- Experimentalstudies On The Effects of Reduction in Gear Tooth Stiffness Lubricant Film Thicknessina Spur Geared SystemDocument13 pagesExperimentalstudies On The Effects of Reduction in Gear Tooth Stiffness Lubricant Film Thicknessina Spur Geared SystemBurak TuncerNo ratings yet

- Deep Cement Mixing - Tan - etal-2002-SingaporeMarineClaysDocument12 pagesDeep Cement Mixing - Tan - etal-2002-SingaporeMarineClaysmmm_1978No ratings yet

- Information Management Systems, ObstetricalDocument12 pagesInformation Management Systems, ObstetricalLee ThoongNo ratings yet

- Method Statement For Marble Flooring and Marble Wall CladdingDocument10 pagesMethod Statement For Marble Flooring and Marble Wall Claddingumit100% (1)

- Standards For Mobile Health-Related AppsDocument9 pagesStandards For Mobile Health-Related Appsharsono harsonoNo ratings yet

- Checklist - Turning Client To Lateral or Prone PositionDocument3 pagesChecklist - Turning Client To Lateral or Prone PositionNorhaina AminNo ratings yet

- MIP Model For Split Delivery VRP With Fleet & Driver SchedulingDocument5 pagesMIP Model For Split Delivery VRP With Fleet & Driver SchedulingMinh Châu Nguyễn TrầnNo ratings yet

- Community Action (Community Engagement)Document3 pagesCommunity Action (Community Engagement)Rellie CastroNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2095263519300275 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S2095263519300275 MainsafiradhaNo ratings yet

- Apostolic ConstitutionsDocument2 pagesApostolic ConstitutionsMarcel100% (1)

- Midterm PathfitDocument5 pagesMidterm PathfitEDETH SUBONGNo ratings yet

- Angel CVDocument2 pagesAngel CValexandraNo ratings yet

- Fuels and CombustionDocument28 pagesFuels and CombustionDrupad PatelNo ratings yet

- Science Subject For Middle School - 7th Grade - DNA in Biology by SlidesgoDocument55 pagesScience Subject For Middle School - 7th Grade - DNA in Biology by SlidesgoJenniferNo ratings yet

- Ex. No: 6.a Linear Search AimDocument6 pagesEx. No: 6.a Linear Search AimSARANYA.R MIT-AP/CSENo ratings yet

- Chassis Family: MX1 MX2 MX3 MX4 MX5 MX6 MX7 MX8 MX10 MX12 Mx5ZDocument7 pagesChassis Family: MX1 MX2 MX3 MX4 MX5 MX6 MX7 MX8 MX10 MX12 Mx5ZchepimancaNo ratings yet

- GL QlikView Dashboard DocumentationDocument29 pagesGL QlikView Dashboard DocumentationJilani Shaik100% (1)

- Dogmatism, Religion, and Psychological Type.Document16 pagesDogmatism, Religion, and Psychological Type.ciprilisticusNo ratings yet