Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Javma-Javma 229 10 1602

Javma-Javma 229 10 1602

Uploaded by

ltcgmoreiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Javma-Javma 229 10 1602

Javma-Javma 229 10 1602

Uploaded by

ltcgmoreiraCopyright:

Available Formats

10/26/2006 2:07 PM Page 1602

Signalment factors, comorbidity, and trends

SMALL ANIMALS

in behavior diagnoses in cats:

736 cases (1991–2001)

Michelle Bamberger, MS, DVM, and Katherine A. Houpt, VMD, PhD, DACVB

ABBREVIATIONS

Objective—To describe trends in behavior diagnoses ABC Animal Behavior Clinic at Cornell University

from 1991 to 2001; assess the relationship between CUHA Cornell University Hospital for Animals

diagnoses and age, sex, reproductive status, and

breed; and evaluate associations between diagnoses however, in several studies,11-13 aggression is listed first.

within the same cat (comorbidity). Although the age, sex, and breed distributions of behav-

Design—Retrospective case series. ioral problems in cats have been described in several stud-

Animals—736 cats. ies,1,3-6,8,10,13,14 none report or analyze associations between

Procedures—Medical records were reviewed for diagnoses within the same cat or methodically evaluate

species, breed, sex, reproductive status, consultation trends from year to year.

year, birth date, and diagnoses. The primary objective of the study reported here

Results—The caseload decreased over the course of was to describe and analyze trends in feline behavior

the study. Aggression toward people increased, and diagnoses made at the ABC from 1991 to 2001 inclu-

spraying decreased. Cases involving Siamese cats sive. Secondary objectives included assessing the rela-

decreased over time. Siamese cats were evaluated tionship between behavior diagnoses and signalment

more often than expected in general and specifically factors (eg, age, sex, reproductive status, and breed),

for aggression and ingestive behavior problems, assessing the distribution of these factors over time,

whereas Persian cats were evaluated more often than and evaluating comorbidity within the caseload.

expected for elimination outside of the litter box.

Domestic shorthair cats were evaluated less often

than expected in general and specifically for aggres- Criteria for Selection of Cases

sion, ingestive behavior problems, and house soiling. Criteria for the selection of cases have been

Male cats were overrepresented. Cats with ingestive described.15 Medical records for 751 cats evaluated at the

behavior problems were evaluated at a median age of ABC from January 1, 1991, through December 31, 2001,

1.5 years, compared with cats with other problems were evaluated for this study. Records of 15 cats were

(median age, 5.5 years). Certain diagnoses were clus- excluded from the ABC population because of incom-

tered, with a mean of 1.2 diagnoses/cat. plete data; therefore, 736 cats were included in the study.

Conclusions and Clinical Relevance—Results sug-

gested that in cats, behavior problems changed over the Procedures

course of the study, age and breed distributions varied Breed, sex, reproductive status, consultation year,

among diagnoses, and certain diagnoses were likely

to occur together. (J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006;229: birth date, and behavior diagnoses were gathered. A

1602–1606) maximum of 3 diagnoses were recorded for each cat;

these diagnoses were the first 3 listed in the record.

Cats (n = 23,701) evaluated at the CUHA over the

N umbers and types of behavioral problems may

change over time; it is therefore important that gen-

eral practitioners understand current trends as well as

same period served as the reference population for

distributions of affected cats by age, sex, and breed. Such

knowledge on the part of practitioners may greatly

reduce consultation time and aid in making the correct

diagnosis.

In studies1-4 based on cat owners’ opinions, house soil-

ing or nonbehavioral concerns3,4 have been reported as the

2

main problem. Results of most feline case studies5-10 also

indicate that house soiling is the most common problem;

From the Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary

Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853. Dr. Bamberger’s pre-

sent address is Vet Behavior Consults, 1225 Hinging Post Rd, Ithaca,

NY 14850.

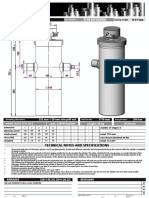

The authors thank Dr. Robert Strawderman for advice on statistical Figure 1—Plot of the number of cats evaluated for behavioral prob-

analysis, Dr. Robert Oswald for advice on data entry and analysis, lems at the ABC from 1991 to 2001. The y-axis is scaled as the

and Emma Williford and Doreen Turk for technical assistance. square root of the number of cats. The line is the linear regression

Address correspondence to Dr. Bamberger. of the data (slope = –0.355; SE = 0.08; r2 = 0.68; P = 0.002).

1602 Scientific Reports: Retrospective Study JAVMA, Vol 229, No. 10, November 15, 2006

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/08/23 12:20 AM UTC

10/26/2006 2:07 PM Page 1603

breed, sex, reproductive status, and age comparisons. with the CUHA population. In general, more males had

SMALL ANIMALS

Breed, sex, reproductive status, and age data from the diagnoses in the categories of aggression, ingestive behav-

CUHA population were gathered independently. Over ior problems, and house soiling. For most diagnoses,

the entire study, a breed was assigned to all cats, and more neutered cats were evaluated in the ABC popula-

sex and reproductive status were specified for > 98% of tion, except for the diagnoses of ingestive behavior prob-

the cats. The owners were able to specify the age in lems, defecation outside of the litter box, and urination

62% of the cats. Further procedures for this study have and defecation outside of the litter box, for which no dif-

been described.15 Ninety-six diagnoses taken from orig- ference was detected between the populations. No trends

inal records were assigned to general categories. over time in sex were detected in either population.

Statistical analysis—Statistical methods used in Table 1—Distribution (No. of affected cats [%]) of diagnoses

this study have been described.15 All analyses were per- among 736 cats evaluated for behavioral problems at the ABC

formed with standard software.a All tests were 2-tailed, from 1991 to 2001.

and values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. Diagnosis No. of cats (%)

Aggression 268 (36.4)

Results People-directed aggression 100 (13.6)

The number of cats evaluated at the ABC decreased Owner-directed aggression 95 (12.9)

(slope = –0.355; SE = 0.08; r2 = 0.68; P = 0.002) between Dominance-related aggression 48 (6.5)

Animal-directed aggression 190 (25.8)

1991 and 2001 (Figure 1). In the CUHA population, the Intercat aggression 185 (25.1)

number of cats increased over the same period (slope = Anxieties 15 (2.0)

0.99; SE = 0.06; r2 = 0.96; P < 0.001). Locomotor behavior 0

Ingestive behavior 32 (4.3)

Self-directed aggression 6 (0.8)

Distribution of diagnoses—The number and per- Grooming behavior 9 (1.2)

centages of affected cats for all major category diagnoses Fears 2 (0.3)

and all diagnoses with an absolute number of 32 or more House soiling 418 (56.8)

Marking 128 (17.4)

affected cats over the entire study period were deter- Spraying 128 (17.4)

mined (Table 1). The category of house soiling account- Elimination 317 (43.1)

ed for the largest percentage of affected cats evaluated Urination 170 (23.1)

Urination and defecation 101 (13.7)

during the study period, followed by aggression, inges- Defecation 46 (6.3)

tive behavior problems, unruly behavior, anxieties, mis- Miscellaneous 13 (1.8)

cellaneous, excessive vocalization, excessive grooming, Phobias 0

self-directed aggression, sexual behavior, and fears. Sexual behavior 5 (0.7)

Unruly behavior 29 (3.9)

Vocalization behavior 10 (1.4)

Trends in diagnoses—Trends were detected for 2

diagnoses (Table 2). In the subcategory of people- Percentages do not add to 100% because each cat may have had

up to 3 diagnoses. Major category diagnoses and all other diagnoses

directed aggression, an upward trend was observed, with $ 32 cases/y over the study period are listed.

whereas for spraying, a downward trend was observed.

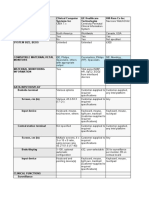

Relationship between diagnoses and age— Table 2—Results of logistic regression analysis of the frequency

Comparisons within the ABC population were made of various behavior diagnoses in cats from 1991 to 2001.

(Figure 2), and only diagnoses with an age difference

Diagnosis Slope SE P value

(between populations of affected cats with the diagno-

sis and those without) of > 2 years were considered to Aggression directed at people 0.100 0.036 0.006

Spraying –0.103 0.035 0.003

be clinically important, as described.15 Overall, median

age at evaluation was 4.5 years, mean age was 5.6 Slope = Slope of the regression line.

years, and the interquartile range was 2.5 to 7.5 years. P value indicates comparison with a slope of 0.

Only the diagnosis of ingestive behavior problems was

significantly (P < 0.001) different and clinically impor-

tant regarding comparison between affected cats with

the diagnosis (median age, 1.5 years; interquartile

range, 1.5 to 3.5 years) and those without the diagno-

sis (median age, 5.5 years; interquartile range, 2.5 to

7.5 years). For all diagnoses, an upward trend for

median age over time was observed (slope = 0.26; SE =

0.094; r2 = 0.46; P = 0.022); corresponding data from

CUHA revealed no trend (Figure 3).

Relationship between diagnoses and sex—Sex dif-

ferences among cats with various diagnoses were deter-

mined (Table 3). Overall, neutered males (ABC, 95%;

CUHA, 81%) and neutered females (ABC, 93%; CUHA,

80%) were evaluated much more often than sexually

intact cats. Overall, more male cats and more neutered Figure 2—Histograms of the percentage of cats evaluated at the

cats were evaluated in the ABC population, compared ABC and CUHA as a function of age.

JAVMA, Vol 229, No. 10, November 15, 2006 Scientific Reports: Retrospective Study 1603

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/08/23 12:20 AM UTC

10/26/2006 2:07 PM Page 1604

Relationship between diagnoses and breed—For

SMALL ANIMALS

breeds that had ≥ 30 cats with any diagnosis and for

breeds with the 3 highest percentages of cats with each

category of diagnosis, the percentages of affected cats,

compared with all affected cats, were determined for

the ABC population; corresponding percentages for

these breeds were also determined for the CUHA pop-

ulation (Table 4). Across all diagnoses, Siamese cats

comprised a significantly higher percentage of the

total number of cats in the ABC population, compared

with the CUHA population; American Domestic

Shorthair cats comprised a lower percentage of the

total number of cats. The diagnosis of ingestive behav-

Figure 3—Box-and-whisker plots of age (years) versus year of

ior problems was given to a low number of cats over

diagnosis for all cats evaluated at the ABC. The line is the linear the study (n = 32) and, thus, low numbers of cats in

regression of the data (slope = 0.26; r2 = 0.46; SE = 0.09; P = most breeds (1 to 2); because of this, only 2 breeds

0.022). were reported for this diagnosis. A downward trend

was detected over time in numbers of Siamese cats

Table 3—Distribution of sexes for cats with various behavior (slope = –0.191; SE = 0.061; P = 0.002); a similar trend

diagnoses, 1991–2001. was also seen in the CUHA population (slope =

–0.073; SE = 0.011; P < 0.001). When regressions

Diagnosis Male (%) Female (%)

between the ABC and CUHA populations were com-

All diagnoses 57.6* 42.4 pared, a significant (P < 0.001) difference was detect-

Aggression 57.1* 42.9

People-directed aggression 58.0† 42.0 ed in Siamese cats—the number of Siamese cats in the

Dominance-related aggression 68.8* 31.3 ABC population decreased at a greater rate than in the

Animal-directed aggression 57.4* 42.6 CUHA population.

Ingestive behavior 65.6* 34.4

House soiling 56.2* 43.8

Spraying 75.0* 25.0 Comorbidity—Of all cats, 79.6% had 1 diagnosis,

Defecation 65.2† 34.8 15.4% had 2 diagnoses, and 5% had 3 or more diag-

*Significantly (P # 0.05) greater than values in the opposite sex

noses made at the time of evaluation. The mean num-

in the ABC population and values for the same sex in the corre- ber of diagnoses per cat was 1.2, and certain diagnoses

sponding reference CUHA population. †Significantly (P # 0.05) occurred in clusters. Significant associations between 2

greater than values in the opposite sex in the ABC population only. diagnoses that occurred together were determined

For the CUHA population, percentages of male and female cats

were 50.3% and 49.7%, respectively. (Table 5). Most associations occurred between diag-

noses in the house soiling category.

Table 4—Distribution (%) of breeds in a reference (CUHA) population and among cats with various

behavior diagnoses evaluated at the ABC from 1991 to 2001.

Breed CUHA All diagnoses Aggression Ingestive behavior House soiling

ADS 80.6 66.8* 71.3* 43.8* 65.6*

Domestic longhair 8.0 8.3 7.8 9.1

Persian 1.4 5.0†

Siamese 3.6 6.0† 6.0† 31.3†

For the CUHA population, values indicate percentage distribution of cats for each breed.

*Significantly (P # 0.05) less than that of the CUHA population. †Significantly (P # 0.05) greater than that of

the corresponding CUHA population.

All diagnoses = Breeds with 30 or more cases; for all other diagnoses, values are given for the top 3

breeds with regard to the number of cats with each diagnosis, except when numbers were equal or case

numbers were low. ADS = American Domestic Shorthair.

Table 5—Associations between pairs of diagnoses in 736 cats evaluated at the ABC form 1991 to 2001.

D1 D2 No. D1 D2 P value

Spraying Urination 17 128 (13.3) 170 (10.0) 0.004

Spraying Urination and defecation 15 128 (11.7) 101 (14.9) 0.033

Play aggression Dominance-related 6 24 (25.0) 48 (12.5) , 0.001

directed at aggression

owners

Play aggression Attention-seeking 7 24 (29.2) 25 (28.0) , 0.001

directed at behavior

owners

Intercat aggression Urination 5 185 (2.7) 170 (2.9) , 0.001

No. = Number of cats with both diagnoses. D1 = Number of cats with diagnosis 1 (percentage of cats that

also had diagnosis 2 in parentheses). D2 = Number of cats with diagnosis 2 (percentage of cats that also had

diagnosis 1 in parentheses). The last column gives the value of P as determined by the Pearson χ2 test.

1604 Scientific Reports: Retrospective Study JAVMA, Vol 229, No. 10, November 15, 2006

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/08/23 12:20 AM UTC

10/26/2006 2:07 PM Page 1605

Discussion The median age at evaluation for all behavioral

SMALL ANIMALS

House soiling was diagnosed in more than half of problems combined was 4.5 years, and the mean age

all cats, and < 75% of these occurrences were caused by was 5.6 years. Mertens and Dodman5 found the largest

elimination outside of the litter box. More than half of age category of cats with behavioral problems to be 4

the elimination cases were associated with urination to 5 years, whereas a study1 based on an owner survey

(53.6%), followed by urination and defecation found the mean age at evaluation to be 5 years. In our

(31.8%), and then defecation (14.5%). Others have study, ingestive behavior problems was the only diag-

found that elimination outside of the litter box was the nosis with both a clinically important and significant

most common behavioral problem in cats.5,7,16-18 In the age difference between cats with that diagnosis (medi-

study reported here, aggression accounted for 36.4% of an age, 1.5 years) and cats with any behavioral diagno-

all cats evaluated and was primarily caused by fighting sis (median age, 5.5 years). Bradshaw and Neville33

between cats. Ninety-five percent of aggression against reported that pica often occurred between 6 and 18

people was directed at owners, and more than half of months of age, occurring most frequently in the 2

these cases involved status-related issues, although months following adoption.

others have found either play aggression19 or redirected An upward trend was detected in the median ages

aggression20 to be the main causes of aggression of cats over the study period. Because a similar trend

towards people. Because both house soiling and was not detected in the CUHA population, this

aggression can be associated with difficulties in treat- increase cannot be attributed to cats living longer lives.

ment and management, they are important to recog- However, one could speculate that this trend may be a

nize and understand. result of owner awareness and willingness to treat con-

An upward trend in people-directed aggression was ditions such as cognitive dysfunction, coupled with

detected. In addition to aggression related to status, veterinarians’ increasing ability to treat behavioral con-

aggression also occurred during play and when situa- ditions previously considered to be caused by old age

tions caused the cat to redirect its aggression at the and unmanageable. To our knowledge, no other study

owner. To make an accurate diagnosis, veterinarians has examined changes in age over this period of time

should quiz owners on specific contexts of the aggres- or considered these factors.

sion.21,22 The upward trend in people-directed aggression Males were evaluated more frequently than expect-

may be attributable to an increasing tendency to keep ed overall (57.6%) in the study reported here, and

cats inside the home (and thus interacting more with numbers of neutered cats always exceeded those of

people) and may be a result of efforts by welfare and sexually intact cats, reflecting the current common

wildlife groups.23 A downward trend was detected in practice of neutering pets routinely. For most diag-

spraying, which was similar to findings of the noses, neutered cats were also evaluated more often

Association of Pet Behaviour Counsellors14 in their than expected, compared with the CUHA population.

review of cases from 1995 to 2000. The downward trend Others have also reported evaluating more males and

in spraying may be indicative of general practitioners’ more neutered cats in general for behavioral prob-

willingness to treat rather than to refer such cats and to lems.5,6 We found males to be overrepresented in the

the efficacy of serotonergic agents such as clomipramine house soiling category (all house soiling diagnoses

and fluoxetine24-27 as well as pheromones28,29,b in manag- combined) as well as in the diagnoses of spraying and

ing this problem. defecation outside of the box. Others have found an

Siamese cats were evaluated more frequently than equal sex distribution for defecation outside of the

expected overall for aggression as well as for ingestive box9 but also found that males were evaluated more

behavior problems (pica was the largest individual diag- frequently than expected for spraying.9,17 Males and

nosis in this category with 40% of cases). Results of neutered cats were overrepresented in the category of

other studies also indicate that Siamese cats are overrep- aggression; this has been reported in 1 other case-

resented for aggression30 and pica.31-33 Under the house review study.30 In the study reported here, males were

soiling category, Persian cats were the only breed to be also overrepresented for ingestive behavior problems;

overrepresented overall for several elimination problems Bradshaw and Neville33 reported similar findings in

(urination or defecation outside of the box). Himalayan their study on pica.

cats and mixed-breed cats were evaluated more fre- Because of the difficulty that may be involved in

quently only for the individual diagnosis of urination making correct diagnoses, especially involving house

and defecation outside of the litter box. No breed was soiling,34 it would greatly benefit veterinarians to be

overrepresented regarding spraying. Results of other aware of which diagnoses may occur together. In our

studies17 have also implicated Persian cats as being over- study, the largest number of significant associations

represented for elimination outside of the litter box. occurred between spraying and urination outside of

Siamese cats were the only breed for which signif- the box or between spraying and urination and defeca-

icant changes were detected in numbers of cases dur- tion outside of the box. Owners with cats eliminating

ing the study in both the ABC and CUHA populations. outside of the box should be questioned carefully dur-

It is interesting that the change was a downward one, ing history-taking to rule out concomitant spraying.

with changes significantly greater in the ABC popula- Social issues among cats may also lead to house soil-

tion, and is interesting to speculate, as suggested for ing.35,36 In the present study, intercat aggression and uri-

selection of dog breeds,15 whether the high percentage nation outside of the litter box occurred together more

of behavioral problems in this breed may be affecting often than chance would predict. Because aggression

prospective owners’ selection of this breed as a pet. between cats may be passive and difficult for the owner

JAVMA, Vol 229, No. 10, November 15, 2006 Scientific Reports: Retrospective Study 1605

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/08/23 12:20 AM UTC

10/26/2006 2:07 PM Page 1606

to detect, careful questioning during the consultation 14. Voith VL. Clinical animal behavior: profile of 100 animal

SMALL ANIMALS

is necessary and may help to define these issues and behavior cases. Mod Vet Pract 1981;62:483–484.

15. Bamberger M, Houpt KA. Signalment factors, comorbidity,

link them if both are indeed present. Also, play aggres- and trends in behavior diagnoses in dogs: 1,644 cases (1991–2001).

sion was associated with attention-seeking behavior as J Am Vet Med Assoc 2006;229:1591–1601.

well as status-related (dominance-related) aggression. 16. Halip JW, Vaillancourt JP, Luescher UA. A descriptive study

Knowing that these behaviors can occur together will of 189 cats engaging in inappropriate elimination behaviors. Feline

help veterinarians to educate owners and tailor a treat- Pract 1998;28:18–22.

ment plan to address all issues. It is important to keep 17. Beaver BV. Housesoiling by cats: a retrospective study of

120 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1989;25:631–637.

in mind that the data reported here represent only cats 18. Borchelt PL, Voith VL. Elimination behavior problems in

referred to veterinary behaviorists and that breed dis- cats. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1986;8:197–207.

tributions reported in this study do not necessarily 19. Borchelt PL, Voith VL. Aggressive behavior in cats.

reflect breed prevalence of behavioral problems. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1987;9:49–56.

20. Chapman BL, Voith VL. Cat aggression redirected to people:

a. Statistix 7, version 7, Analytical Software, Tallahassee, Fla. 14 cases (1981–1987). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1990;196:947–950.

b. White JC, Mills DS. Efficacy of synthetic facial pheromone (F3) 21. Frank D, Dehasse J. Differential diagnosis and management

analogue (Feliway) for the treatment of chronic non-sexual of human-directed aggression in cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim

urine spraying by the domestic cat (abstr), in Proceedings. 1st Pract 2003;33:269–286.

Conf Vet Behav Med 1997;262. 22. Heath S. Feline aggression. In: Horwitz D, Mills D, Heath S,

eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline behavioural medicine.

Gloucester, England: BSAVA, 2002;216–228.

References 23. Gray LB. Keeping your cats indoors. Available at:

1. Heidenberger E. Housing conditions and behavioural prob- www.scvas.org/keepcats.html. Accessed Jun 1, 1997.

lems of indoor cats as assessed by their owners. Appl Anim Behav Sci 24. Dehasse J. Feline urine spraying. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1997;

1997;52:345–364. 52:365–371.

2. American Animal Hospital Association. AAHA pet owner 25. Eckstein RA, Hart BL. Pharmacologic approaches to urine

survey results. Trends Magazine 1993;9:32–33. marking in cats. In: Dodman NH, Shuster L, eds. Psychopharmacology

3. American Pet Products Manufacturers Association. of animal behavior disorders. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Science Inc,

1999–2000 APPMA national pet owners survey. Greenwich, Conn: 1998;267.

American Pet Products Manufacturers Association Inc, 1999;26, 94. 26. Pryor PA, Hart BL, Cliff KD, et al. Effects of a selective sero-

4. American Pet Products Manufacturers Association. tonin reuptake inhibitor on urine spraying behavior in cats. J Am Vet

2003–2004 APPMA national pet owners survey. Greenwich, Conn: Med Assoc 2001;219:1557–1561.

American Pet Products Manufacturers Association Inc, 2003;54, 104. 27. Hart BL. Control of urine marking by use of long-term treat-

5. Mertens PA, Dodman NH. The diagnosis of behavioral ment with fluoxetine or clomipramine in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc

problems in dogs, cats, horses and birds—characteristics of 323 2005;226:378–382.

cases (July 1994–June 1995). Part 2: cats, horses and birds. 28. Pageat P. Functions and use of the facial pheromones in the

Kleintierpraxis 1996;41:259–270. treatment of urine marking in the cat. Interest of a structural analog,

6. Appleby D, Magnus E, Bailey Q, et al. Data from the APBC annu- in Proceedings. 21st Cong World Small Anim Vet Assoc 1996;197–198.

al review of cases, 1994–2003. Available at: www.apbc.org.uk/data.htm. 29. Frank D, Erb HN, Houpt KA. Urine spraying in cats: pres-

Accessed May 1, 2005. ence of concurrent disease and effects of a pheromone treatment.

7. Borchelt PL, Voith VL. Elimination behavior problems in Appl Anim Behav Sci 1999;61:263–272.

cats. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1981;3:730–737. 30. Beaver BV. Feline behavioral problems other than house-

8. Blackshaw JK. Abnormal behaviour in cats. Aust Vet J 1988; soiling. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1989;25:465–469.

65:395–396. 31. Houpt KA. Domestic animal behavior for veterinarians and

9. Denenberg S, Landsberg GM, Horwitz D, et al. A compari- animal scientists. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, 2005;333.

son of cases referred to behaviorists in three different countries, in 32. Houpt KA, Zicker S. Dietary effects on canine and feline

Proceedings. In: Current issues and research in veterinary behavioral behavior. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2003;33:405–416.

medicine: papers presented at 5th International Veterinary Behavorial 33. Bradshaw JWS, Neville PF. Factors affecting pica in the

Meeting. West LaFayette, Ind: Purdue University Press, 2005;56–62. domestic cat. Appl Anim Behav Sci 1997;52:373–379.

10. Fatjo J, Amat M, Ruiz de La Torre JL, et al. Small animal 34. Bergman L, Hart BL, Bain M, et al. Evaluation of urine

behavior problems in small animal practice in Spain, in Proceedings. marking by cats as a model for understanding veterinary diagnostic

Annu Symp Anim Behav Res 2002;55–56. and treatment approaches and client attitudes. J Am Vet Med Assoc

11. Hart BL, Hart LA. Canine and feline behavioral therapy. 2002;221:1282–1286.

Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1985;131, 137, 141. 35. Overall KL. Diagnosing and treating undesirable feline

12. Olm DD, Houpt KA. Feline house-soiling problems. Appl elimination behaviour. Feline Pract 1993;21(2):11–15.

Anim Behav Sci 1988;20:335–345. 36. Ogata N, Takeuchi Y. Clinical trial of a feline pheromone

13. Voith VL. Clinical animal behavior. Calif Vet 1979;33:21–25. analogue for feline urine marking. J Vet Med Sci 2001;63:157–161.

1606 Scientific Reports: Retrospective Study JAVMA, Vol 229, No. 10, November 15, 2006

Unauthenticated | Downloaded 11/08/23 12:20 AM UTC

You might also like

- An Introduction To Scholarship Building AcademicDocument3 pagesAn Introduction To Scholarship Building AcademicNina Rosalee21% (29)

- Birth and Death Rate Estimates of Cats and Dogs inDocument14 pagesBirth and Death Rate Estimates of Cats and Dogs inHidayatul IfkarNo ratings yet

- Demographics and Comorbidity of Behavior Probl - 2019 - Journal of Veterinary BeDocument10 pagesDemographics and Comorbidity of Behavior Probl - 2019 - Journal of Veterinary BeAnonymous TDI8qdYNo ratings yet

- 3 Tests of AggressionDocument10 pages3 Tests of AggressionLuanna FrançaNo ratings yet

- Javma-Javma 243 2 236Document8 pagesJavma-Javma 243 2 236Astrid HiyoNo ratings yet

- Fvets 07 00472Document6 pagesFvets 07 00472vetwolf7543No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Dogs and Cats With Tumors of The Ear Canal: 145 Cases (1978-1992)Document7 pagesEvaluation of Dogs and Cats With Tumors of The Ear Canal: 145 Cases (1978-1992)Flaviu TabaranNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Dogs and Cats With Tumors of The Ear Canal: 145 Cases (1978-1992)Document7 pagesEvaluation of Dogs and Cats With Tumors of The Ear Canal: 145 Cases (1978-1992)Flaviu TabaranNo ratings yet

- 2010 The Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating Scale CCDRDocument6 pages2010 The Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating Scale CCDRKaren SánchezNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Risk and Age of Onset of Cancer and Behavioral Disorders in GonadectomizedDocument11 pagesEvaluation of The Risk and Age of Onset of Cancer and Behavioral Disorders in Gonadectomized'Márjore LorenaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Coat Color and Aggressive Behaviors in The Domestic CatDocument16 pagesThe Relationship Between Coat Color and Aggressive Behaviors in The Domestic CatRomina DatuNo ratings yet

- Vizsla Javma StudyDocument11 pagesVizsla Javma Studyapi-257186144No ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography 1Document6 pagesAnnotated Bibliography 1api-743809775No ratings yet

- 1 - Prevalence of Infectious Diseases in Feral CatsDocument10 pages1 - Prevalence of Infectious Diseases in Feral CatsRenny BarriosNo ratings yet

- Fvets 08 666727Document15 pagesFvets 08 666727lexislyNo ratings yet

- Brucella PDFDocument2 pagesBrucella PDFdeboraNo ratings yet

- Javma 217 11 1661Document5 pagesJavma 217 11 1661alice_in_wonderland2690No ratings yet

- Anxiety and Impulsivity Factors Associated With P - 2016 - Applied Animal BehavDocument8 pagesAnxiety and Impulsivity Factors Associated With P - 2016 - Applied Animal BehavOscar BenzNo ratings yet

- Urinary Incontinence in Male Dogs Under Primary Veterinary Care in England: Prevalence and Risk FactorsDocument10 pagesUrinary Incontinence in Male Dogs Under Primary Veterinary Care in England: Prevalence and Risk FactorsVennaOktaviaAnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography Final DraftDocument8 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Final Draftapi-743809775No ratings yet

- Assisting Decision-Making On Age of Neutering For 35 Breeds of Dogs: Associated Joint Disorders, Cancers, and Urinary IncontinenceDocument14 pagesAssisting Decision-Making On Age of Neutering For 35 Breeds of Dogs: Associated Joint Disorders, Cancers, and Urinary IncontinenceTaires RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Breed Differences in Canine AggressionDocument20 pagesBreed Differences in Canine AggressionJD46No ratings yet

- 2008 - Duffy - Breed Differences Canine AggressionDocument20 pages2008 - Duffy - Breed Differences Canine AggressionArmand GarciaNo ratings yet

- Forensic Animal HoardingDocument11 pagesForensic Animal HoardingBunbury eNo ratings yet

- Lifetime Prevalence of Owner-Reported Medical Conditions in The 25 Most Common Dog Breeds in The Dog Aging Project PackDocument13 pagesLifetime Prevalence of Owner-Reported Medical Conditions in The 25 Most Common Dog Breeds in The Dog Aging Project PackDesislava DenkovaNo ratings yet

- Aat Dementia PDFDocument3 pagesAat Dementia PDFMinodora MilenaNo ratings yet

- Animal-Assisted Therapy For Dementia: A Review of The LiteratureDocument3 pagesAnimal-Assisted Therapy For Dementia: A Review of The LiteratureMinodora MilenaNo ratings yet

- Autistic Traits in The General Population: A Twin StudyDocument7 pagesAutistic Traits in The General Population: A Twin StudyVi KekaNo ratings yet

- Behavioral Assessment of Child-Directed Canine AggDocument5 pagesBehavioral Assessment of Child-Directed Canine AggTanya Vane WayNo ratings yet

- Pruebas Genéticas en Gatos DomésticosDocument17 pagesPruebas Genéticas en Gatos DomésticosJesuit AguileraNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Genetics-Limits Article 7Document11 pagesBehavioural Genetics-Limits Article 7ekifriNo ratings yet

- Immaculate Heart of Mary Academy: Congregation of The Augustinian Recollect SisterDocument2 pagesImmaculate Heart of Mary Academy: Congregation of The Augustinian Recollect Sisterjohnrollin oconNo ratings yet

- Cancer Tiroideo en PerrosDocument6 pagesCancer Tiroideo en PerrosRoxana Celi ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors, Prognostic Indicators, and Outcome of Pyothorax in CatsDocument6 pagesRisk Factors, Prognostic Indicators, and Outcome of Pyothorax in CatscaiomagsribNo ratings yet

- Feline Compulsive DisorderDocument8 pagesFeline Compulsive DisorderOat MealNo ratings yet

- TMP D453Document14 pagesTMP D453FrontiersNo ratings yet

- 2010 The Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating Scale CCDRDocument6 pages2010 The Canine Cognitive Dysfunction Rating Scale CCDRIngrid AtaydeNo ratings yet

- Survey of Predation by Domestic CatsDocument4 pagesSurvey of Predation by Domestic CatsALEXNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0376635722000237 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0376635722000237 MainArthur PiresNo ratings yet

- I J V S: Nternational Ournal of Eterinary CienceDocument6 pagesI J V S: Nternational Ournal of Eterinary CienceDanuartaNo ratings yet

- Diverio Et Al. 2008Document13 pagesDiverio Et Al. 2008Luis Antonio Buitron RamirezNo ratings yet

- Histopathological Results of Mouth Lesions inDocument11 pagesHistopathological Results of Mouth Lesions inDaniela Angel CortesNo ratings yet

- Correlation of Neuter Status and Expression of Heritable DisordersDocument12 pagesCorrelation of Neuter Status and Expression of Heritable DisordersSoraia LopesNo ratings yet

- 2005 de Palma Et Al - Evaluating The Temperament in Shelter Dogs (Ethogram)Document22 pages2005 de Palma Et Al - Evaluating The Temperament in Shelter Dogs (Ethogram)EnciaflorNo ratings yet

- Comportamento de GatosDocument5 pagesComportamento de GatosRafaella SchmitzNo ratings yet

- Ajvr-Ajvr 1998 59 05 630Document13 pagesAjvr-Ajvr 1998 59 05 630gui.fawksNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Romanian Pet Caretakers Towards Sterilization of Their Animals: Gender Conflict Over Male, But Not Female, Companion AnimalsDocument7 pagesAttitudes of Romanian Pet Caretakers Towards Sterilization of Their Animals: Gender Conflict Over Male, But Not Female, Companion Animalsadirom47No ratings yet

- Key Determinants of Dog and Cat Welfare: Behaviour, Breeding and Household LifestyleDocument9 pagesKey Determinants of Dog and Cat Welfare: Behaviour, Breeding and Household LifestyleALVARO ESNEIDER AVILA GUZMANNo ratings yet

- Preventive Veterinary MedicineDocument6 pagesPreventive Veterinary MedicineDimas AdipNo ratings yet

- Fontanarrosa2006Document13 pagesFontanarrosa2006KuyinNo ratings yet

- Common Risk Factors For Urinary House Soiling (Periuria) in Cats and Its Differentiation: The Sensitivity and Specificity of Common Diagnostic SignsDocument12 pagesCommon Risk Factors For Urinary House Soiling (Periuria) in Cats and Its Differentiation: The Sensitivity and Specificity of Common Diagnostic Signsvaguecouch1351No ratings yet

- Ramos 2019Document3 pagesRamos 2019Valentina Sosa PachecoNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Autism in A United States Population: The Brick Township, New Jersey, InvestigationDocument9 pagesPrevalence of Autism in A United States Population: The Brick Township, New Jersey, InvestigationSuci Triana PutriNo ratings yet

- SCH Roer 1998Document10 pagesSCH Roer 1998Harshit AmbeshNo ratings yet

- The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) - Adolescent VersionDocument8 pagesThe Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) - Adolescent VersionMaria Clara RonquiNo ratings yet

- Canaries in The Coal Mine ArticleDocument7 pagesCanaries in The Coal Mine ArticlevibhutiNo ratings yet

- J 1939-1676 2010 0541 XDocument10 pagesJ 1939-1676 2010 0541 XTom NagelsNo ratings yet

- J Yhbeh 2015 06 002Document9 pagesJ Yhbeh 2015 06 002Shaimaa NasrNo ratings yet

- Bullying in Schools: Self Reported Anxiety, Depression, and Self Esteem in Secondary School ChildrenDocument2 pagesBullying in Schools: Self Reported Anxiety, Depression, and Self Esteem in Secondary School ChildrenDaryl BuenNo ratings yet

- Dog - and Owner-Related Risk Factors For Consideration of Euthanasia or Rehoming.Document11 pagesDog - and Owner-Related Risk Factors For Consideration of Euthanasia or Rehoming.Jana VerslyppeNo ratings yet

- Zimbra To Office 365 Migration GuideDocument6 pagesZimbra To Office 365 Migration GuideEDSON ARIEL AJÚ GARCÍANo ratings yet

- Crystal Ball Installation GuideDocument40 pagesCrystal Ball Installation Guidebogdann_damianNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Eligibility FinalDocument9 pagesCertificate of Eligibility Finalgena sanchez BernardinoNo ratings yet

- Chassis Family: MX1 MX2 MX3 MX4 MX5 MX6 MX7 MX8 MX10 MX12 Mx5ZDocument7 pagesChassis Family: MX1 MX2 MX3 MX4 MX5 MX6 MX7 MX8 MX10 MX12 Mx5ZchepimancaNo ratings yet

- Marketing Communications in The Digital AgeDocument49 pagesMarketing Communications in The Digital Age2m shoppingNo ratings yet

- For Teachers of English: Vol. 29 No. 1 - January/June 2022 ISSN 0120-5927Document243 pagesFor Teachers of English: Vol. 29 No. 1 - January/June 2022 ISSN 0120-5927Luisa CalderónNo ratings yet

- Impact of Efl Teachers Teaching Style On Students Academic Performance and Satisfaction: An Evidence From Public Sector Universities of KarachiDocument27 pagesImpact of Efl Teachers Teaching Style On Students Academic Performance and Satisfaction: An Evidence From Public Sector Universities of KarachiJIECEL FLORESNo ratings yet

- Cilindro Penta Hydraulic PowerDocument1 pageCilindro Penta Hydraulic PowerUniversity FilesNo ratings yet

- Life Science Bulletin, Vol. 7 (2) 2010 217-222Document6 pagesLife Science Bulletin, Vol. 7 (2) 2010 217-222Narasimha MurthyNo ratings yet

- Bab 5 Unit - Gear (Nota Politeknik)Document13 pagesBab 5 Unit - Gear (Nota Politeknik)Syfull musicNo ratings yet

- Information Management Systems, ObstetricalDocument12 pagesInformation Management Systems, ObstetricalLee ThoongNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Methods Applied For Extraction and Processing of Oil Palm Products in Selected States of Southern NigeriaDocument12 pagesEvaluation of Methods Applied For Extraction and Processing of Oil Palm Products in Selected States of Southern NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- SOP - Ready Mix Annual Facility AuditDocument2 pagesSOP - Ready Mix Annual Facility AuditTri widiyah VitantiNo ratings yet

- Grammar ManualDocument130 pagesGrammar ManualJahnaviNo ratings yet

- I VTECDocument20 pagesI VTECraju100% (2)

- SWE2007 - Fundamentals of Operating SystemsDocument6 pagesSWE2007 - Fundamentals of Operating SystemsmaneeshmogallpuNo ratings yet

- 130724Document20 pages130724Caracal MohNo ratings yet

- Steel Structures With Prestressed Linear and Membrane ElementsDocument6 pagesSteel Structures With Prestressed Linear and Membrane Elementsmanju bhargavNo ratings yet

- LogDocument12 pagesLogNida MunirahNo ratings yet

- Customizing Oracle Applications 11i Using Custom - PLL Varun TekriwalDocument15 pagesCustomizing Oracle Applications 11i Using Custom - PLL Varun Tekriwalgoud24No ratings yet

- Notes - Introduction To I/O PsychologyDocument30 pagesNotes - Introduction To I/O PsychologyMARIA SABINA BIANCA LIM UY100% (2)

- ICT-Pedagogy Integration in MathematicsDocument11 pagesICT-Pedagogy Integration in MathematicsKaren Faye LagundayNo ratings yet

- Power ResourcesDocument14 pagesPower ResourcesDawoodNo ratings yet

- Patrol GR: GI MA EM LC EC FE CL MT Automatic Transmission AT TF PD FA RA BR ST RS BT HA EL IDXDocument2 pagesPatrol GR: GI MA EM LC EC FE CL MT Automatic Transmission AT TF PD FA RA BR ST RS BT HA EL IDXAttila SomorjaiNo ratings yet

- Grand Case Presentation (MI, COPD and BPH)Document80 pagesGrand Case Presentation (MI, COPD and BPH)Sarah Lim100% (2)

- Counterfeit and Fraudulent Items - Mitigating The Increasing Risk - Rev1 of 1019163Document128 pagesCounterfeit and Fraudulent Items - Mitigating The Increasing Risk - Rev1 of 1019163diNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Information & Communications Technology Introduction ToDocument37 pagesIntroduction To Information & Communications Technology Introduction ToKathleen BorjaNo ratings yet

- Virtual Lab-Water QualityDocument7 pagesVirtual Lab-Water Qualityapi-268159571No ratings yet

- Excel Basics RoadmapDocument3 pagesExcel Basics RoadmapLalatenduNo ratings yet