Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Determines Military Expenditures?

What Determines Military Expenditures?

Uploaded by

Bilal GhaniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Determines Military Expenditures?

What Determines Military Expenditures?

Uploaded by

Bilal GhaniCopyright:

Available Formats

What Determines Military

Expenditures?

Empirical evidence on the economic and politicalfactors that influence national military spending

Daniel P. Hewitt

I i recent years, some countries have spent association with military spending. The second decision the leadership makes

as much as one fourth of GDP on the military, Among the political variables investigated, is on the level of overall government spend-

while others less than 1 percent. Wide varia- as expected, countries engaged in interna- ing. Clearly, the two decisions are interrelated

tions in military expenditures exist not only tional war or civil war are found to spend and should reinforce each other. A country

between different regions of the world and more on the military. Additionally, countries that spends more on the military is likely to

different economic groups but also within dif- characterized as multiparty democracies have a larger public sector. Likewise, a coun-

ferent categories of countries (see "Military spend less on the military than others—such try that devotes a larger share of its resources

Expenditures in the Developing World" by as countries characterized as monarchies (but to government is also likely to spend more on

the author in the September 1991 issue of without multiparty democracy), military gov- the military. The framework, which is specifi-

Finance & Development). Can this pattern of ernments, and socialist governments. Finally, cally set up to test this relationship, confirms

military expenditure be explained by the eco- land area and border length are found to have that the two reinforce each other.

nomic characteristics and political circum- a positive influence on the level of military The second equation, therefore, focuses on

stances of nations? Are differences in military expenditure. the determinants of central government ex-

policies due primarily to country specific cir- The analytical framework of the study is penditure as a proportion of GDP. The pur-

cumstances, or are they attributable to inher- able to explain 55 percent of the variation pose of this equation is to test for the indirect

ently unobservable political phenomena— and, therefore, a large proportion of the varia- influences on military expenditure transmit-

such as excessively complicated political in- tion can be accounted for by political and eco- ted through changes in central government

teractions between different countries? nomic characteristics of countries. Since a sig- expenditure. Since the results show a positive

A recent study of military expenditures in nificant proportion is still left unexplained, relationship between military and central

125 countries over a 17-year span provides country specific historical and political cir- government spending, factors that induce an

useful insights into the apparent determi- cumstances are also undoubtedly quite im- increase in overall government spending indi-

nants of world military expenditures (see portant influences. rectly induce an increase in military spend-

box). Contrary to popular belief, the study in- ing. (The results from the second equation

dicates that military spending is highly reac- Empirical results should not be interpreted, however, as offer-

tive to observable financial constraints. The The empirical framework envisions the ing a full explanation of the determinants of

ratio of military expenditure to GDP is found leadership of a nation making two types of central government expenditures.) In this

to rise with GDP in low- and middle-income decisions. First, the leadership decides how equation, the level of military expenditures is

countries and remain constant for high in- much to spend on the military, and thus, the viewed as an influence on the demand for

come countries. Heavily indebted countries first empirical equation focuses on the deter- overall government expenditures. The other

and small low-income economies are found to minants of military expenditures as a propor- financial variables are indicators of resource

spend less on the military than other nations. tion of GDP (see table). Among the explana- constraints on the economy and the govern-

The level of public and publicly guaranteed tory variables, the economic indicators ment. The political variables are viewed as

foreign financing is found to have a positive incorporated in the equation represent an in- proxies for the political preferences of the

dication of the financial constraints con- leadership, as in the first equation.

fronting governments. The political variables Economic variables. The results indi-

are indicators either of the political circum- cate that the ratio of military expenditures to

For details of this study, see "Military Expenditure: stances (such as a state of war) or the political GDP rises with GDP and per capita GDP (see

Econometric Testing of Economic and Political ideology of the leadership. The geographical table). The level of military spending rises

Influences" by the author, available as IMF variables reflect the cost of defending more quickly than GDP at low levels of GDP

Working Paper WP/91/53, countries. and flattens out to a constant ratio at higher

22 Finance & Development / December 1991

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

levels of GDP. Thus, low-income nations are more on the military than low-income nations. Finally, a government's ideological view of

characterized by relatively low levels of mili- The net flow of public and publicly guaran- the role of the state in an economy is a poten-

tary spending, middle-income nations spend a teed external financing, which indicates the tially important factor.

higher proportion of their GDP on the mili- level of foreign financing that the government Countries engaged in international war

tary, and military expenditures tend to level contracts, also has a positive effect on govern- spend the most and those engaged in civil war

out to a constant proportion of GDP for ment expenditures, as expected. However, it are second highest, as expected. Among the

higher-income nations. also has a positive association with military other variables, the ranking from highest to

As expected, military expenditures are pos- expenditures. Therefore, higher levels of gov- lowest expenditures on the military was

itively correlated with central government ex- ernment financing relative to GDP are found monarchy, military government, socialist gov-

penditures, that is, they rise and fall together. to induce higher military spending both indi- ernment, and others. By inference, multiparty

A 1 percent rise in central government expen- rectly, by inducing higher overall government democracies are found to spend the least on

ditures is found to cause a 0.75 percent rise in spending, and directly, by increasing the the military (see box).

military expenditures, which implies that mili- share of the budget allocated to the military, The political categories are slightly differ-

tary expenditures tend to increase at a on average. This result implies that external ent in the government expenditure equation.

slightly lower rate than the budget. This re- assistance to a nation will induce higher mili- The two war-related options were dropped be-

sult, therefore, establishes the proposition that tary spending. Further, in general, these re- cause theory suggests that the presence of

increases in central government expenditures sults indicate that national levels of military war should not have a direct effect on the

tend to increase military expenditures and expenditures do react to financial constraints overall level of government spending; instead,

factors that influence government spending and that governments take account of eco- war will increase military expenditures and

indirectly influence military spending. nomic conditions and consequences, as well thereby indirectly influence government ex-

Military expenditures are also found to in- as political circumstances, in forming the mili- penditures. The results indicate that socialist

crease government expenditures. tary budget. governments have the highest level of central

The availability of external funding is an Political and geographic variables. government spending relative to the GDP,

important element of the financing constraint While recognizing the likely importance of po- then in descending order are multiparty

on government. The variables associated with litical circumstances in formulation of mili- democracies, other forms of government,

the 15 most heavily indebted middle-income tary expenditure policy, their inclusion in em- monarchies, and military governments. Thus,

nations (including ten in Latin America), one pirical analysis presents a challenge, since relative to multiparty democracies, socialist

covering 1972-79 and the other covering only objective and observable features of a na- governments tended to have higher central

1980-88, illustrate this. Surprisingly, during tion can be used. Accordingly, each country government expenditures and to allocate a

the 1970s (prior to the world debt crisis), both has been assigned to mutually exclusive polit- higher proportion of government spending to

central government expenditures and military ical categories (which can also vary over the military. Military governments and

expenditures in the heavily indebted countries time). The list of categories was chosen for monarchies tended to have smaller public sec-

were below the world average. During the their observability as well as their potential tors, but tended to allocate a higher share of

1980s, the level of military expenditures in relevance. the budget to the military; the same is true of

these countries relative to GDP fell further, The benchmark category is a multiparty countries in the "other" category, but to a

while central government expenditures rose democracy, not recently engaged in either an lesser extent. However, the direct effect of the

somewhat relative to the world average. This international war or a civil war (including all form of government on military spending

can be interpreted as a reaction to the nations whose political process is dominated dominates the indirect effect in each case.

increased interest costs that these countries by a multiparty system, regardless of the po- Therefore, monarchies and military govern-

had to bear—the higher interest payments in- litical ideology of the leadership or the nomi- ments allocate a larger share of GDP to the

creased government expenditures and nal presence of a monarch). The other cate- military than socialist governments when

simultaneously depressed the share available gories are (1) countries at war or recently both the direct and indirect effects are

for military expenditures (see "Military engaged in an international conflict (regard- combined.

Expenditures in the Developing World" by less of their political leadership), (2) countries The geographic variables included in the

the author in the September 1991 issue of engaged in a major internal civil war (regard- estimation equation confirmed prior expecta-

Finance & Development). less of their political leadership), (3) countries tions. Land area and border lengths are found

Another financial proxy associated with ruled by monarchies, (4) countries ruled by to have a positive influence on military spend-

small low-income economies shows that while military governments, (5) countries ruled by ing, presumably because they increase the

their average central government expendi- socialist governments, and (6) others (which costs of defense. Additionally, as expected,

tures were equal to the world average, their consist of one-party states that do not fit into coastal borders have a less powerful effect

military expenditures were significantly be- any of the other categories or highly unstable than land borders, since coastal borders pro-

low the world average. Apparently the low democracies). vide natural protection in most cases, and are,

purchasing power of these nations and their These categories capture a number of fac- therefore, less costly to defend.

emphasis on economic and social develop- tors that are likely to affect the priority the Central government expenditure.

ment (as indicated by the high share of such leadership assigns to military expenditures, The analysis of central government expendi-

expenditures in central government budgets) while the number of options was kept to a tures in this study is not intended to provide a

led them to allocate a lower proportion of both minimum for the sake of simplicity. A state of comprehensive overview of the determinants

government resources and GDP to the mili- war obviously affects the demand for military of government spending. Instead, its purpose

tary. This result lends support to the notion expenditures. Additionally, the historical ba- is to indicate how military expenditure inter-

that military expenditures are a "superior sis for the government is likely to influence acts with central government expenditure (see

good" among developing nations, that is, mid- the leadership's view of military expenditures equation 2 in the table).

dle- and high-income nations spend relatively and the priority assigned to the military. As will be recalled, a 1 percent increase in

Finance & Development /December 1991 23

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

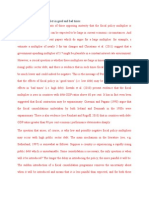

An explanation of the Mow important are individual factors in military

empirical framework and central government expenditures?

In order to indicate how the results in this study

Equation 1 Dependent variable: Ratio of military expenditure to GDP1

are derived, a brief discussion of some of the

technical details may be useful. The quality of Coefficient

empirical results always reflects the accuracy of Constant -7.9

the data. The military expenditure data used for Real GDP in US dollars1 0.23

2

Real GDP in US dollars squared -0.0075

this study are based primarily on estimates of

Population1 0.025

the Stockholm International Peace Research Ratio of central government expenditure to GDP1 0.76

Institute (SIPRI), which is widely believed to Net flow of public and publicly guaranteed external capital 1.02

represent the best available comprehensive Heavily indebted nations, 1972-79 -0.39

data source. The other major sources include Heavily indebted nations, 1980-88 -0.45

IMF published data, World Bank, United Small low-income economies -0.15

Nations, and US government publications. International war 1.50

Another important characteristic of an em- Civil war 1.08

pirical study is the framework in which it is Socialist government 0.32

Military government 0.69

cast Every empirical study, either explicitly or

Monarchy 1.15

implicitly, is based on a model. The particular Other forms of government 0.37

model or framework that is used, by necessity, Land areas (in square kilometers) 0.057

imposes a certain interpretation on the data and Land borders (in kilometers) 0.030

the results indicate whether or not the frame- Coastline (in kilometers) 0.012

work that the researcher used is plausible. R-squared 0.557 / Number of observations 2,025

However, the process rules out other points of

Equation 2 Dependent variable: Ratio of central government expenditure to GDP1

view or other plausible interpretations of ob-

served tendencies simply by ignoring them. Coefficient

The analysis of government behavior in this Constant 2.8

Development index1 0.47

study is based upon what economists call a Ratio of military expenditures to GDP1 0.183

"public choice" framework. In this setting, the Net flow of public and publicly guaranteed external capital 1.72

leadership is assumed to act as if it were an eco- Heavily indebted nations, 1972-79 -0.097

nomic entity, such as a business making a pro- Heavily indebted nations, 1980-88 -0.049

duction decision or a household deciding how to Small low-income economies 0.001

spend its available income. The leadership is Socialist government 0.101

treated as if it maximizes its own welfare sub- Military government -0.226

ject to its specific national economic, political, Monarchy -0.160

Other forms of government -0.043

and geographic circumstances.

The leadership is envisioned as making two R-squared 0.316 / Number of observations 2,025

fundamental decisions in formulating the mili- Source: Hewitt, 1991. See box on model. 'Significant at the 95 percent level of confidence. "Significant at the 99

percent level of confidence. 'The natural loa of the variable. 2Jhe sauare of the natural log of GDR

tary budget: It chooses the overall level of gov-

ernment spending and, simultaneously, decides

the proportion of the budget to allocate to the

military. Such a process is represented as an al- percentage change in the dependent variable asso- technical reasons, there is no coefficient associ-

location of national resources between private ciated with a percentage change in the explanatory ated with the benchmark category, multiparty

expenditures, military expenditures, and non- variable. For the other variables, the coefficients in- democracies. Instead, all the other coefficients

military government expenditures (consisting dicate the direct influence. are interpreted as indicating the effect of being

primarily of social and economic programs). In the first equation, the dependent variable is in that particular category in comparison to be-

Although there are numerous other decisions the natural log of the ratio of military expenditures ing in the benchmark category. Finally, to ad-

and subcategories of expenditures that are ex- to GDP. Among the explanatory factors, the follow- just for changes in the overall level of military

tremely important for the economy, this delin- ing have coefficients that represent elasticities (be- expenditure over time, variables for each year

eation is the focus of the study. This framework cause in each case the natural log of the variable were included in the analysis. The results, not

produces a two equation system. In the first, the was used in the empirical test): the natural log of reported in the table, indicate that a consider-

determinants of military expenditures as a pro- GDP (in US dollars, based upon 1980 purchasing able drop in the level of world military expendi-

portion of GDP are tested. The second equation power parity weights); the natural log of GDP ture occurred in the 1980s,

tests the determinants of central government squared; population; the ratio of central govern- In the second equation, the dependent vari-

expenditures as a proportion of GDP. ment expenditures to GDP; land area (in square able is the ratio of central government expendi-

The statistical technique is designed to iso- kilometers); land borders (in kilometers); and coast- tures to GDP. The explanatory variables are the

late the effects of each variable from the other line (in kilometers). natural log of the ratio to GDP of military ex-

variables. For instance, the effect of central gov- The other variables have ordinary coefficients in- penditures, and a development index based on

ernment spending on military expenditures is stead of elasticities. These are the ratio to GDP of per capita GDP and life expectancy (see the

isolated from the effects of population or GDP the net flow of public and publicly guaranteed ex- working paper for full details). The other vari-

variations. Therefore, the coefficients provide ternal financing (for net debtor developing nations ables are the same as in the first equation, ex-

much more information than might be derived only); 15 heavily indebted nations in 1972-79; 15 cept that the two war-related variables have

from a simple correlation analysis. heavily indebted nations in 1980-88; 31 small low- been dropped. In this case, the time variables

The coefficients associated with most of the income economies; and the political variables de- indicate a steady increase in central govern-

major variables are elasticities that indicate the scribed in the text With the political variables, for ment expenditures occurred over the period.

24 Finance & Development j December 1991

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

central government spending was found to view, which arrives at essentially the same

lead to a 0.75 percent increase in military Daniel P. Hewitt conclusion, is that military policy is primarily

spending on average. Thus, increases in gov- a US citizen, is an driven by external forces and, therefore, is

ernment spending are shared between mili- economist in the largely outside the control of a nation's politi-

tary and nonmilitary spending. The central Government Expenditure cal leadership.

government expenditure equation examines Analysis Division of the The empirical results of our study, while

the opposite perspective—how changes in IMF's Fiscal Affairs not necessarily refuting these theories, sup-

military expenditures affect the overall level Department. He holds a port an alternative explanation. Financial fac-

of central government expenditure. The result PhD from Columbia and tors emerge as an important determinant of

has taught at the

is that a 1 percent increase in military expen- military expenditures. Thus, affordability ap-

University of Connecticut.

ditures induces a 0.18 percent increase in cen- pears to be a major consideration for govern-

tral government spending. Since this is re- ment policymakers in the realm of military ex-

markably close to the average ratio of penditures, as in other areas. Further, the

military expenditures to GDP (0.17), it implies observed pattern suggests that governments

that autonomous increases in military expen- view the military as a luxury item instead of a

diture are exactly accommodated by increas- firms that central government spending rela- necessity. If military expenditures were a ne-

ing overall budgetary expenditures. tive to GDP tends to rise with the level of eco- cessity, low-income and small countries would

The strict interpretation of this result is nomic development. allocate a higher share of their GDP to the mil-

that other types of expenditures are virtually itary. Instead, the opposite pattern emerges.

unaffected by increases in military expendi-

Conclusion

Military expenditures of middle-income na-

tures, instead private spending is crowded The primary motivation behind the study tions are found to be higher both in absolute

out. This is, of course, an average result. It is described in this article was to determine if terms and in proportion to GDP, while high-

more likely that the effect of higher military any discernible pattern could be identified in income nations spend about the same relative

expenditures on other types of government the military expenditure policies across coun- to GDP. An implication of these findings is

expenditures varies from country to country. tries. The military expenditure data, which that financial assistance of any sort to low-in-

In some circumstances, where the budget con- were collected in connection with another come countries is likely to induce higher mili-

straint is not tight, increases in military study, offer a suitable basis for such a study tary expenditures, either directly or indirectly,

spending lead to higher spending on all since they are reasonably comprehensive, through an easing of budgetary constraints.

items—when the government increases mili- cover a long period, and represent the best The results also support the hypothesis

tary spending, it simultaneously spends more available estimates. that geographical features of a nation influ-

on social programs to appease competing Opinions differ on the proper level of mili- ence military policies, as do political factors

interest groups. In countries where the tary expenditure in any given country and on such as being in a state of war and the form of

government is financially constrained, it what motivates countries to pursue the widely government. One interpretation of these re-

accommodates higher military expenditures different military expenditure policies that are sults is that these variables are proxies for the

by decreasing other types of government observed. One prominent view is that no political situation and the ideology of the lead-

expenditures. worldwide pattern exists because military pol- ership. However, the reverse causality could

Another result in equation 2 is that the de- icy is an inherently country specific phe- exist. The geopolitical status of a country

velopment index, which is an indication of the nomenon. For instance, a country's preference could influence both the type of government

level of economic development of a country for military expenditure might primarily re- that takes power and the level of military

(see box), has a positive coefficient. This con- flect historical experience. A complementary expenditures.

International Monetary Fund announces

The IMF's Statistical Systems in Context of

Revision of the United Nations'

A System of National Accounts

This volume, sponsored by the IMFs Statistics Department To order, please write or call:

and edited by Vicente Galbis, contains a selection of papers International Monetary Fund

presented at meetings sponsored fay the IMF for the revision Publication Services Box FD-104

of the United Nations' System of National Accounts (SNA). 70019th Street, N.W.

Experts from the IMF, UN, OBCD, EC, and other statistical Washington, D.C. 20431 U.S.A.

institutions examine issues pertaining to external sector Telephone: (202) 623-7430

transactions, public sector accounts, and financial flows and Telefax: (202) 623-7201

balances. Cable Address: INTBRFUND

Available in English, ISBN 1-55775-159-5 (paper) 1991 American Express, MasterCard

US$35.00 and VISA credit cards accepted.

Finance & Development I December 1991 25

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

You might also like

- Supply Chain Strategy Analysis of The Benetton CaseDocument6 pagesSupply Chain Strategy Analysis of The Benetton CasebizaczkiNo ratings yet

- War and Peace CyclesDocument6 pagesWar and Peace CyclesOana Stancu-MihaiNo ratings yet

- Manual: SawdoctoringDocument228 pagesManual: SawdoctoringAndrei SlupicNo ratings yet

- Five-Year Plans of PakistanDocument5 pagesFive-Year Plans of PakistanAym Aay Tee75% (4)

- Okoro GE EssayDocument8 pagesOkoro GE EssaySonma OkoroNo ratings yet

- A006 Eps-Journal v1n1 Expenditure PDFDocument4 pagesA006 Eps-Journal v1n1 Expenditure PDFKimberly GrejaldoNo ratings yet

- Local and Aggregate Fiscal Policy MultipliersDocument2 pagesLocal and Aggregate Fiscal Policy MultipliersCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Paper Policies FinaleDocument11 pagesPaper Policies FinaleFabio TessariNo ratings yet

- Economic Effect On MilitaryDocument29 pagesEconomic Effect On MilitaryFahrian YovantraNo ratings yet

- Am Grateful For Advice From Olivier Blanchard, Stan Erigerman, PeterDocument50 pagesAm Grateful For Advice From Olivier Blanchard, Stan Erigerman, PeterManchitoNo ratings yet

- Paul Collier: The Political Economy of Natural ResourcesDocument28 pagesPaul Collier: The Political Economy of Natural ResourcesKaligula GNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Force Planning in A Time of Austerity: Decremental SpendingDocument11 pagesStrategy and Force Planning in A Time of Austerity: Decremental SpendingJose Juan Velazquez GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Economics of War and Peace: Opportunities in The Post-Cold War WorldDocument9 pagesThe Economics of War and Peace: Opportunities in The Post-Cold War WorldreetamNo ratings yet

- SafariDocument9 pagesSafariAhmad dummarNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Government Spending On Real Exchange Rates: Evidence From Military Spending Panel DataDocument44 pagesThe Effects of Government Spending On Real Exchange Rates: Evidence From Military Spending Panel DataBaber AminNo ratings yet

- 5 Articles KuladeepDocument4 pages5 Articles Kuladeepguvvalarohith1998No ratings yet

- The Connection Between Political Stability and Inflation: Insights From Four South Asian NationsDocument12 pagesThe Connection Between Political Stability and Inflation: Insights From Four South Asian NationsSatoshi NakamotoNo ratings yet

- ResourceCurse - Muestra InglésDocument8 pagesResourceCurse - Muestra IngléspensamientoespiralNo ratings yet

- The State-Level Nonlinear Effects of Government SPDocument9 pagesThe State-Level Nonlinear Effects of Government SPSean ShengNo ratings yet

- Collier - AID Policy and Peace Reducing The Risks of Civil ConflictDocument17 pagesCollier - AID Policy and Peace Reducing The Risks of Civil Conflictsyed9953No ratings yet

- Civil WarDocument30 pagesCivil WarKamran HaiderNo ratings yet

- Inflation and The Size of GovernmentDocument44 pagesInflation and The Size of GovernmentTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 194 6957 PDFDocument63 pages10 1 1 194 6957 PDFZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Global Finance and MacroeconomyDocument10 pagesGlobal Finance and MacroeconomyAdison BrilleNo ratings yet

- Trading War For PeaceDocument7 pagesTrading War For PeaceHp PraneshNo ratings yet

- Nber Working Paper SeriesDocument35 pagesNber Working Paper SeriesKyaw Htet AungNo ratings yet

- 1.11 Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand: Learning OutcomesDocument11 pages1.11 Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand: Learning OutcomesDeepak SinghNo ratings yet

- Military Spending and DevelopmentDocument20 pagesMilitary Spending and DevelopmentABDUL MOHSINNo ratings yet

- A Treatise on War Inflation: Present Policies and Future Tendencies in the United StatesFrom EverandA Treatise on War Inflation: Present Policies and Future Tendencies in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Government Size and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: A Political-Economy FrameworkDocument18 pagesGovernment Size and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: A Political-Economy FrameworkAmerico Sanchez Cerro MedinaNo ratings yet

- FWWDocument1 pageFWWDann BejenaruNo ratings yet

- Power and InterdependenceDocument9 pagesPower and Interdependence李侑潔No ratings yet

- Geoeconomics - Edward LutwakDocument10 pagesGeoeconomics - Edward LutwaksadiaNo ratings yet

- Ramey Shapiro GovtDocument50 pagesRamey Shapiro GovttrofffNo ratings yet

- The Growth of Government Spending and The Money Supply: Evidence and Implications Within and Across Industrial CountriesDocument31 pagesThe Growth of Government Spending and The Money Supply: Evidence and Implications Within and Across Industrial CountriesprudhvinathNo ratings yet

- QR 712Document14 pagesQR 712Lan EvaNo ratings yet

- FiscalPolicyVolatilityAndCapitalM PreviewDocument62 pagesFiscalPolicyVolatilityAndCapitalM PreviewCaíque MeloNo ratings yet

- Nace J SeniorProject2018Document31 pagesNace J SeniorProject2018Hân Du TrầnNo ratings yet

- Project ProposalDocument37 pagesProject ProposalOluwasegun KolawoleNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Group3Document11 pagesResearch Paper Group3Israfil BaxshizadaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Group3Document8 pagesResearch Paper Group3Israfil BaxshizadaNo ratings yet

- How Does Political Violence Affect Currency Substitution? Evidence From EgyptDocument29 pagesHow Does Political Violence Affect Currency Substitution? Evidence From EgyptMalik Moammar HafeezNo ratings yet

- Economic Coercion and Power Redistribution During Wartime: Quarter 2017Document22 pagesEconomic Coercion and Power Redistribution During Wartime: Quarter 2017GulzhaukharNo ratings yet

- Defense Paper 2007Document33 pagesDefense Paper 2007Rafael BonatoNo ratings yet

- Loanable Funds Market (F)Document4 pagesLoanable Funds Market (F)Rishav SNo ratings yet

- Multi 0 PageDocument60 pagesMulti 0 PageSyed Aal-e RazaNo ratings yet

- Taylor PN 2010 - 3Document7 pagesTaylor PN 2010 - 3marceloleitesampaioNo ratings yet

- Military Ontervention ReasonaDocument5 pagesMilitary Ontervention ReasonaMaria AsgharNo ratings yet

- Palgrave Macmillan Journals Journal of International Business StudiesDocument12 pagesPalgrave Macmillan Journals Journal of International Business Studieszola1976No ratings yet

- The Impact of Political Relations Between Countries On Economic RelationsDocument27 pagesThe Impact of Political Relations Between Countries On Economic RelationsshafiaNo ratings yet

- s1049 0078 - 2899 - 2980099 220160926 30676 4l83wm LibreDocument15 pagess1049 0078 - 2899 - 2980099 220160926 30676 4l83wm LibreAshutoshNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument2 pagesEconomicsqn5jrvqccmNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Inflation and Stock ReturnsDocument6 pagesLiterature Review On Inflation and Stock Returnsafdtvuzih100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0304405X1200181X MainDocument20 pages1 s2.0 S0304405X1200181X MainNabil FarhanNo ratings yet

- Mastanduno Economic StatecraftDocument19 pagesMastanduno Economic StatecraftRaminta LukšaitėNo ratings yet

- M TiwariFiscal Deficit and Inflation: An Empirical Analysis For IndiaDocument26 pagesM TiwariFiscal Deficit and Inflation: An Empirical Analysis For IndiaShweta Raman SharmaNo ratings yet

- Decentralization and The Post-War Political Economy Francis G. Castles Discussion Paper No. 399 March 1999Document28 pagesDecentralization and The Post-War Political Economy Francis G. Castles Discussion Paper No. 399 March 1999Franditya UtomoNo ratings yet

- Macro AssessmentDocument10 pagesMacro Assessmenttung ziNo ratings yet

- Assigment IndividualDocument14 pagesAssigment Individualhaftamu GebreHiwotNo ratings yet

- 2.0 The Fiscal Policy Multiplier in Good and Bad TimesDocument3 pages2.0 The Fiscal Policy Multiplier in Good and Bad TimesMichael OppongNo ratings yet

- Steven Lobell - The Challenge of HegemonyDocument17 pagesSteven Lobell - The Challenge of HegemonyJuanBorrellNo ratings yet

- EC339 AssignmentDocument8 pagesEC339 AssignmentdustinNo ratings yet

- Updated Client List J4690, 47,48 OnwardsDocument18 pagesUpdated Client List J4690, 47,48 Onwardshbgroups3018No ratings yet

- Situational Analysis of Women Workers in Sericulture: A Study of Current Trends and Prospects in West BengalDocument21 pagesSituational Analysis of Women Workers in Sericulture: A Study of Current Trends and Prospects in West BengalChandan RoyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Geo-TechnologyDocument45 pagesIntroduction To Geo-TechnologyEngr Muhammad WaseemNo ratings yet

- Article 14 PDFDocument15 pagesArticle 14 PDFFarhan ShahriarNo ratings yet

- Keybanc TMT Conference 2019Document19 pagesKeybanc TMT Conference 2019mdorneanuNo ratings yet

- Daily Sales LedgerDocument2 pagesDaily Sales LedgerImran AliNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoiceDHANDAPANINo ratings yet

- De Vroey Equilibrium and Disequilibrium in Economic Theory A Confrontation of The Classical, Marshallian and Walras-Hicksian ConceptionsDocument26 pagesDe Vroey Equilibrium and Disequilibrium in Economic Theory A Confrontation of The Classical, Marshallian and Walras-Hicksian ConceptionsEleutheros1No ratings yet

- The Economic Impact of E-CommerceDocument8 pagesThe Economic Impact of E-CommerceSumit SahaNo ratings yet

- Letter To U.S. Senator Bill Nelson, Complaint About U.S. Postal ServiceDocument48 pagesLetter To U.S. Senator Bill Nelson, Complaint About U.S. Postal ServiceNeil GillespieNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Asset and Liability ManagementDocument27 pagesLong-Term Asset and Liability ManagementImtiaz MasroorNo ratings yet

- 114 (1) (Return of Income Filed Voluntarily For Complete Year) - 2019Document4 pages114 (1) (Return of Income Filed Voluntarily For Complete Year) - 2019ms03009833120No ratings yet

- Electoral ListDocument53 pagesElectoral Listbatsy4evNo ratings yet

- Va 13Document40 pagesVa 13deepak SunalNo ratings yet

- Rental ReceiptDocument1 pageRental ReceiptGuru KrishNo ratings yet

- MIDC's Role in Economy of MaharashtraDocument13 pagesMIDC's Role in Economy of MaharashtraAbhishek SinghNo ratings yet

- Ra 8550 PDFDocument18 pagesRa 8550 PDFDawn Jessa100% (1)

- Eco Lec3 Fin MathDocument83 pagesEco Lec3 Fin MathMiguel Toriente0% (1)

- Inflation: Its Causes, Effects, and Social Costs: Questions For ReviewDocument5 pagesInflation: Its Causes, Effects, and Social Costs: Questions For ReviewAbdul wahabNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Economics 0455/22 February/March 2022Document30 pagesCambridge IGCSE™: Economics 0455/22 February/March 2022Angel XxNo ratings yet

- TA Rules Annex IDocument1 pageTA Rules Annex IGowsigan AdhimoolamNo ratings yet

- Short Profile of The CountryDocument7 pagesShort Profile of The CountryЕлизавета ЗайцеваNo ratings yet

- CEC201 CEScoresheetDocument6 pagesCEC201 CEScoresheetWilliams IbenemeNo ratings yet

- Data Matters - HSBC PDFDocument87 pagesData Matters - HSBC PDFStephane MysonaNo ratings yet

- Adani Enterprises LTD: Financial Analysis ReportDocument13 pagesAdani Enterprises LTD: Financial Analysis ReportSwati ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 5 - Monetary SystemDocument8 pagesTutorial 5 - Monetary SystemQuy Nguyen QuangNo ratings yet

- MADocument3 pagesMAsamiaNo ratings yet