Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Article Byzantine Intelligence

Article Byzantine Intelligence

Uploaded by

rajcic66Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Article Byzantine Intelligence

Article Byzantine Intelligence

Uploaded by

rajcic66Copyright:

Available Formats

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

Intelligence Analysis in 10th Century Byzantium

Andrew Skitt Gilmour

US Intelligence Community analysis as beginning de novo in the

analysts address the capabilities and modern era. This contrasts with the

intentions of foreign actors, a basic broad recognition—in government

national security function of the mod- and in the scholarly community—that

ern nation state. Intelligence analysts the collection of intelligence against

Ancient empires need- attempt to manage uncertainty and rivals and enemies dates to ancient

ed information on their complexity for policymakers, who times and cultures.

must make decisions to advance their

enemies and rivals and nations’ security interests. State- Scholarship on the ancient prac-

worked to acquire it sponsored intelligence analysis in the tice of intelligence collection has

modern era is designed to produce largely not included investigations of

through networks of the beginnings of the analytic part of

a range of finished products includ-

spies and to commu- ing foundational reference works, the intelligence mission. For exam-

nicate it rapidly back immediate tactical and threat infor- ple, in his discussion of Egyptian,

mation, and longer-term strategic Hittite, and subsequent Assyrian,

to palaces—including Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman intel-

assessments.

with fire signaling. The ligence activities, Francis Dvornik

assessment . . . is pre- Such analysis relies principally focused on intelligence collection—

on individuals schooled in analytic especially tactical military informa-

sumed to have taken reasoning who are able to communi- tion—not analysis. Ancient empires

place among individu- cate their analytic judgments derived needed information on their enemies

als but without an insti- from collected, often secret, infor- and rivals and worked to acquire it

mation. Analysts must also discern through networks of spies and to

tutional basis and with- the truthfulness and accuracy of such communicate it rapidly back to pal-

out being written. information amid attempts at decep- aces—including with fire signaling.1

tion by foreign actors. The assessment and interpretation

of the collected information in the

The history of all-source national context of a state’s security objectives

intelligence analysis in the United are presumed to have taken place

States usually begins with World War among individuals but without an

II and the surprise Japanese attack on institutional basis and without being

Pearl Harbor, which demonstrated the written.

strategic consequences of failing to

systematically collect, centralize, and The modern scholarly emphasis

assess intelligence information. The on ancient intelligence as a collec-

establishment in 1947 of the Central tion mission is consistent with how

Intelligence Agency and the subse- ancient historians understood intelli-

quent institutionalization of a national gence. The sixth century Byzantine

intelligence analysis mission have historian Procopius of Caesarea, for

cast the history of such intelligence example, writing about Byzantium’s

The views, opinions, and findings of the author expressed in this article should not be construed as asserting or implying US

government endorsement of its factual statements and interpretations or representing the official positions of any component of

the United States government. © Andrew Skitt Gilmour, 2022.

Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022) 53

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

Scholarly reception of De Administrando Imperio has

overlooked elements of the text’s content and purpose, Addressing Romanus II in the

which suggest the beginnings of state-sponsored all- introduction, Constantine VII makes

source intelligence analysis in Byzantium. explicit that the work’s purpose is to

instruct.

strategic rival Persia, makes clear De Administrando Imperio3 (On the Διδάχθητι, ἃ χρή σε πρὸ πάντων

that intelligence from ancient times Management of the Empire4), which εἰδέναι, καὶ νουνεχῶς τῶν τῆς

was focused on the collection of Constantine VII addressed to his son βασιλείας οἰάκων ἀντιλαβοῦ.7

information: and heir Romanus II.

Be instructed with respect to

Τὰ δὲ τῶν κατασκόπων τοιαῦτά I believe that scholarly reception things which are necessary for

ἐστιν. ἄνδρες πολλοὶ ἐν δημοσίῳ of De Administrando Imperio— you to know before all things,

τὸ ἀνέκαθεν ἐσιτίζοντο, οἳ δὴ though extensive and diverse—has and receive in turn the helms of

ἐς τοὺς πολεμίους ἰόντες ἔν overlooked elements of the text’s rule wisely.

τε τοῖς Περσῶν βασιλείοις content and purpose, which suggest

γινόμενοι ἢ ἐμπορίας ὀνόματι the beginnings of state-sponsored This practical approach to knowl-

ἢ τρόπῳ ἑτέρῳ, ἔς τε τὸ all-source intelligence analysis in edge for the sake of statecraft de-

ἀκριβὲς διερευνώμενοι ἕκαστα, Byzantium. This development in the fines the work at the outset as more

ἐπανήκοντες ἐς Ῥωμαίων wider history of intelligence is espe- than another link in the chain of

τὴν γῆν πάντα τοῖς ἄρχουσιν cially plausible because the middle Byzantine and classical historiog-

ἐπαγγέλλειν ἠδύναντο τὰ τῶν of the 10th century in Byzantium raphy. Αs Warren Treadgold notes,

πολεμίων ἀπόρρητα.2 saw the convergence of state security De Administrando Imperio “cannot

needs, cultural trends, state capacity, really be called” a history, though it

And the matter of spies is as and the rise to power of a bookish contains “much information of histor-

such. Many men from the be- emperor to enable this first shift to ical interest.”8 Confirming the text’s

ginning of time were sustained written intelligence analysis in De outlier status, Constantine VII omits

in state service, men who went Adminstrando Imperio. from his introduction stylistic tropes

to the enemy and were in the about preserving the deeds of men

palaces of the Persians, either that classicizing Byzantine historians

with the pretense of commerce Scholarly Reception of De such as Agathias (c. 530–594) and

or in another way, who after Administrando Imperio Leo the Deacon (949–991) used to

investigating each thing precise- echo Thucydides and Herodotus.

ly and upon returning to Roman De Adminstrando Imperio, was

territory were able to announce composed in Constantinople be- The bulk of the work is more

to those ruling all the secrets of tween 948 and 952.5 It comprises an primer and background information

the enemy. introduction, 53 chapters, and nearly than policy proscription. Chapters

40,000 words. What Constantine VII 14–42 are almost certainly drawn

Four centuries later, around 950, wrote, dictated, had written by others, from an earlier geographic and ethno-

written sources attest to the advent of or included from earlier material has graphic work of Constantine VII, the

intelligence activities that are more fueled scholarly debate over the text’s Περὶ ἐθνῶν (Concerning Peoples).9

than the collection of information. authorship.6 In its initial chapters, the Romilly Jenkins notes that these sec-

Amid a broadly ascendant Middle text mostly provides instructions on tions of De Administrando Imperio

Byzantine state, the Byzantine the conduct of the empire’s foreign “told the traditional, sometimes leg-

Emperor Constantine VII took the policy—with an emphasis on manag- endary stories of how the territories

first halting steps toward develop- ing relations with a nomadic Turkic surrounding the empire came . . . to

ing all-source, secret intelligence people of the Steppe, the Pechenegs be occupied by their present inhabi-

analysis in the service of a state’s (οἱ Πατζινακῖται), who are strate- tants.”10 Anthony Kaldellis has argued

security interests and objectives. gically situated along Byzantium’s that this narrative style is typical of

His groundbreaking, though flawed, northern border on the Black Sea. Byzantine texts written “between the

effort comes down to us in a manual seventh and the twelfth centuries,”

54 Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022)

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

The middle Byzantine state’s bureaucratic structures not

which document the movements of only centralized information to support Constantine VII’s

different peoples from their “original” encyclopedic writings, but also provided the foundation

homelands.11 for dissemination of an analytic written product.

These chapters provide detailed

geographical and historical informa- Administrando Imperio have also The clandestine sources used in

tion on the peoples, lands, and states led to the reception of the work as De Administrando Imperio collected

that mattered to the national security a founding document of diplomatic from individuals tied directly or indi-

interests of the Middle Byzantine history. Dvornik, for example, argued rectly to the Byzantine state situates

state, including the Arab lands, the that the diplomatic and policy focus the text again firmly in the area of

religion of Islam, as well the Balkans, of the work meant it is “the first at- intelligence activity. For example,

Italy, Caucasus, the Rus, and the tempt at the writing of diplomatic his- Dvornik argues that background

Turkic peoples of the Steppe. The tory, thus inaugurating a new genre of information on the Pechenegs in

tour d’horizon Constantine provides historical literature.”14 The secrecy of chapter 37 “could only come from

would be familiar in scope to the an- this diplomacy, however, also places Pecheneg sources” debriefed by

nual global threat survey US intelli- the text in the wider realm of intelli- Byzantine sources.17 Confidential

gence officials provide to members of gence activity, because such sensi- diplomatic contacts with Constantine

Congress. The ability of Constantine tive policy concerns could not have VII’s court were also important

VII to draw upon state archives of an existed apart from collected intelli- sources of information. For exam-

earlier work also anticipates, in early gence information. Paul Stephenson ple, information on the Magyars

medieval form, the centralization and observes that De Administrando in chapters 38–40, according to

retrieval of information that would Imperio “was a work of the greatest Dvornik, “must have been gathered

be essential to modern intelligence secrecy, intended only for the eyes at the imperial court from Hungarian

analysis. of the emperors Constantine VII and sources” amid frequent exchanges of

Romanus II, and their closest advi- embassies.18

The role of intelligence collec- sors.”15 Similarly Jenkins argues that

tion has also been prominent in the text’s secrecy is confirmed “by Information in chapter 9 on how

scholarly reception of the work. For its manuscript history and by circum- the Rus were able to navigate the

example, Dvornik argues that De stances that later writers betray no riparian dangers of the Dneiper as

Administrando Imperio “illustrates knowledge of it.”16 Diplomatic action well as attacks by Pechenegs to make

more than anything else the impor- and intelligence collection appear their way south to the Black Sea for

tance the Byzantines attached to the intertwined in the work. trade with Constantinople is probably

collection of intelligence on foreign derived from Byzantine contacts with

peoples and how they utilized it in the

administration of state affairs.”12 The

broad geographic and ethnographic

scope of the work also prompted

Arnold Toynbee to observe: “The

vast alien world outside the East

Roman Empire’s frontiers excited

Constantine’s curiosity, and, the more

remote the country, the greater his

zest.”13 Such intense intellectual cu-

riosity almost certainly fueled—and

was driven by—extensive intelli-

gence collection by Constantine VII.

A scene from the 12th century manuscript The Chronicle of John Skylitzes. The history was

The diplomatic directives written in the 11th century, but the image is from a 12th century illuminated manuscript.

The picture shows a Pecheneg band ambushing a ruler from Kiev who had purportedly

Constantine VII provides in De

signed a treaty with Rome. Image: Madrid Skylitzes, Folio 173ra.

Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022) 55

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

The clandestine sources used in De Administrando Im-

perio collected from individuals tied directly or indirectly intelligence analysis, Constantine VII

to the Byzantine state situates the text again firmly in the had “the tide of information … coor-

area of intelligence activity. dinated and written down.”26

The information-driven, bookish

Russian envoys sent to negotiate a De Administrando Imperio as character of Constantine VII was

peace treaty with Constantine VII.19 Proto Intelligence Analysis similar to that of modern-day intelli-

Intelligence analysis requires not gence analysts. Analysts always want

The scholarly reception of De

only the collection of information more information and have, for the

Administrando Imperio, despite these

relevant to national security, but also most part, assumed contrasting identi-

acknowledgements of the intelligence

its centralization within the state. ties with the operationally minded

activity underpinning the work, has

At the time of the writing of De collectors of information. Constantine

emphasized much more its value as

Administrando Imperio in the middle VII’s “belief in the practical value of

a source of historical information,

of the tenth century, Byzantium learning and education” 27 also antici-

even if not a formal work of history.

under Constantine VII was at the pated what, in the vernacular of mod-

Robert Browning, for example, sees

peak of a literary and cultural trend ern-day intelligence analysis, is called

the text as “a major source for the

of organizing information in all fields “policy relevance.” Knowledge, and

history of central and eastern Europe

into encyclopedic works, according especially intelligence information,

and southwestern Asia in the high

to Paul Lemerle.23 In addition to De must matter to the state’s interests

middle ages,”20 and D. M. Lang ar-

Administrando Imperio, Constantine to merit analysis. This was true in

gues that “the book’s historical value

VII produced manuals of value to De Aministrando Imperio and is an

derives to a large extent from the fact

intelligence analysis on court cere- essential characteristic of today’s

that it includes exhaustive informa-

monies (De Cerimoniis)—including national-level intelligence analysis.

tion on many little-known . . . nations

by which the Byzantine Empire was the reception of foreign officials and The Middle Byzantine state’s

ringed about.”21 leaders—and historical geography bureaucratic structures not only

(De Thematibus).24 The ability to centralized information to support

A text that stands apart from the maintain what modern intelligence Constantine VII’s encyclopedic writ-

main categories of Byzantine his- analysis would consider a repository ings, but also provided the founda-

toriography and which has defied a of all-source information pertaining tion for dissemination of an analytic

single interpretation, however, offers to the national security interests of written product. Philip Davies notes

the possibility that De Administrando the Middle Byzantine state suggests that the Byzantines “maintained

Imperio can also be understood as that the court of Constantine VII bureaucratically organized security

the beginning of a new genre of met a key precondition for an early structures . . . that ensured a constant

intelligence analysis in the West. As attempt at intelligence analysis in De flow of information about the external

Anthony Kaldellis observes, schol- Administrando Imperio. and internal enemies of the state.”28

arship on De Administrando Imperio

Constantine VII was central to this Luttwak adds, “However ill-informed

has “focused narrowly on specific

effort at centralization. He collected they may have been by modern stan-

passages or even single words,” with-

books, organized their information, dards, the Byzantines still knew much

out considering “the overall structure,

and composed new works to fill in more than most other contemporary

purpose, and meaning of the work.”22

gaps in knowledge. According to rulers.”29

To see Constantine VII’s work as an

inaugural attempt at state-sponsored Jenkins, “Documents from the files These security structures did

all-source intelligence analysis can from every branch of the adminis- not include a formal intelligence

address this deficit. tration, from the foreign ministry, department or ministry and there is

the treasury, the offices of ceremo- no evidence that the palace dissemi-

nial [functions] were scrutinized nated analytic product to other parts

and abstracted.”25 In much the same of the imperial administration.30

manner of producing raw intelligence Nonetheless, the limited distribution

reports as the foundation for modern

56 Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022)

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

A modern depiction of Byzantium’s strategic environment, showing

frequency of conflicts between Byzantium and the expanding Muslim

world between the seventh and 11th centuries in lands and sea along the

coast of the central and eastern Mediterranean Sea. Map by Cplakidas

from Wiki Commons: Byzantine-Arab naval struggle.png

of De Administrando Imperio to Administrando Imperio as an early state still faced threats from peoples

Constantine VII’s heir and a small attempt at state-sponsored all-source of the Steppe to the north, Bulgars

inner sanctum of court officials is an intelligence analysis. Additionally, to the west, and Arabs to the south

early demonstration of the dissemina- the complexity of the security chal- and east, including from Arab naval

tion of a finished analytic product—a lenges facing Constantinople in the forces. As Toynbee has observed,

key element of modern-day nation- mid-10th century joined with these Constantine VII

al-level intelligence analysis. The conditions to make such an early

empire’s existing security structures attempt at intelligence analysis by was aware that the Roman

made this finished product and its Constantine VII inevitable. Empire had been transformed in

dissemination possible. a fundamental way. He recog-

The strategic environment con- nized that it had ceased to be a

The centralization of informa- fronting Constantine VII was analyti- world-state and had become one

tion, the presence of an analytically cally complex and often constraining local state among a number of

minded emperor, and a bureaucratic of Byzantine power. Well into a others.31

organization that could be used to recovery from Arab conquests and

disseminate a finished analytic prod- the internal strife of the Byzantine In this environment, intelligence anal-

uct allow for the consideration of De Dark Age, the Middle Byzantine ysis could efficiently support policies

Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022) 57

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

This circumstantial case that De Admininstrando Imperio

represents a prototype of what would become state-spon- practical advantages to Byzantine

sored, all-source intelligence analysis in the modern era security. Constantine VII urges his

is buttressed by the analytic language in the text itself. son to know that:

Τὰ δέ ἐστιν περὶ διαφορᾶς

that secured Byzantine interests and us, they are able to march out πάλιν ἑτέρων ἐθνῶν,

leverage Byzantine power to maxi- against Cherson and ravage and γενεαλογίας τε αὐτῶν καὶ

mum effects. plunder Cherson itself and the ἐθῶν καὶ βίου διαγωγῆς καὶ

so-called districts. θέσεως καὶ κράσεως τῆς

This circumstantial case that De παρ’ αὐτῶν κατοικουμένης

Admininstrando Imperio represents In chapter 4, he also provides an

γῆς καὶ περιηγήσεως αὐτῆς

a Byzantine prototype of what would analytic explanation of the mili-

καὶ σταδιασμοῦ, καθὼς ἑξῆς

become state-sponsored all-source tary implications for Byzantium of

πλατύτερον διηρμήνευται.35

intelligence analysis in the modern maintaining good relations with the

era is buttressed by the analytic Pechenegs. The matters are again about dif-

language in the text itself. Amid the ferences of each of the peoples,

policy proscriptions, practical advice Ὅτι τοῦ βασιλέως Ῥωμαίων

of their origins, habits, and way

on dealing with foreign peoples, and μετὰ τῶν Πατζινακιτῶν

of life and of the setting and

dense historical information that εἰρηνεύοντος, οὔτε <οἱ>

climate of the territory inhabited

make up most of De Administrando Ῥῶς πολέμου νόμῳ κατὰ τῆς

by them and about a geographic

Imperio, Constantine VII demon- Ῥωμαίων ἐπικρατείας, οὔτε οἱ

description and measurement of

strates analytic reasoning in service Τοῦρκοι δύνανται ἐπελθεῖν. . .33

it, as how next is explained more

of Byzantine security interests. In When it is the case that the Em- extensively.

a faint foreshadowing of far better peror of the Romans is at peace

organized and reasoned modern prod- Constantine VII also shows

with the Pechenegs, neither the

ucts of all-source intelligence analy- analytic skill in identifying facts for

Rus nor the Turks are able to at-

sis, Constantine VII manages to make the reader that matter for assess-

tack by practice of war against

analytic judgments and to demon- ing the resource base and power

the realm of the Romans. . .

strate he is thinking analytically about of peoples in the regions near the

Byzantine security. This complex analytic judgment Crimean Peninsula in the vicinity of

is similar to Constantine’s simple Byzantium’s borders on the Black

In his first chapter, for example, analytic judgment in chapter 2 on the Sea. For example, in chapter 53 he

Constantine VII explains at the outset strategic intent of the Rus: assesses the Byzantine protectorate

his underlying reason for his detailed and trading center of Cherson.

treatment of the Pechenegs: their Ὅτι καὶ οἱ Ῥῶς διὰ σπουδῆς

location is strategically significant. ἔχουσιν εἰρήνην ἔχειν μετὰ τῶν Ὅτι ἐὰν οὐ ταξιδεύσωσιν οἱ

Πατζινακιτῶν.34 Χερσωνῖται εἰς Ῥωμανίαν,

Ὅτι γειτνιάζει τὸ τοιοῦτον ἔθνος καὶ πιπράσκωσι τὰ βυρσάρια

τῶν Πατζινακιτῶν τῷ μέρει τῆς And the Russians are zealous to καὶ τὰ κηρία, ἅπερ ἀπὸ τῶν

Χερσῶνος, καὶ εἰ μὴ φιλίως have peace with the Pechenegs. Πατζινακιτῶν πραγματεύονται,

ἔχουσι πρὸς ἡμᾶς, δύνανται κατὰ οὐ δύνανται ζῆσαι. Ὅτι

τῆς Χερσῶνος ἐξέρχεσθαι καὶ Constantine VII also explains how ἐὰν μὴ ἀπὸ Ἀμινσοῦ καὶ

κουρσεύειν καὶ ληΐζεσθαι αὐτήν history and geography are part of his ἀπὸ Παφλαγονίας καὶ τῶν

τε τὴν Χερσῶνα καὶ τὰ λεγόμενα analytic method. For example, at the Βουκελλαρίων καὶ ἀπὸ τῶν

κλίματα.32 beginning of eight chapters provid- πλαγίων τῶν ρμενιάκων

ing background information and a περάσωσι γεννήματα, οὐ

Because this nation of the history of Arab lands, peoples, and δύνανται ζῆσαι οἱ Χερσωνῖται.36

Pechenegs is neighboring to the religion of Islam, he articulates an

the district of Cherson, and if analytic view that an understanding If ever the Chersonites do not

they are not friendly toward of history and geography provides travel to Romania and sell the

58 Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022)

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

As much as modern historians in the West look to Thu-

skins and wax candles, which cydides and Herodotus to provide the conceptual frame-

they take in hand from the works, it is possible now for intelligence analysts and

Pechenegs, they are not able scholars to look to a medieval Byzantine emperor.

to live. And if ever products do

not pass over from Aminsos and

centralized information base, it is Νῦν οὖν ἄκουσόν μου, υἱέ, καὶ

Paphlagonia and from the Bou-

secret, and it reveals analytic rea- τήνδε μεμαθηκὼς τὴν διδαχὴν

kellarioi, and from both sides of

soning and judgment. As such, it is ἔσῃ σοφὸς παρὰ φρονίμοις,

the Armenians, the Chersonites

groundbreaking. καὶ φρόνιμος παρὰ σοφοῖς

are not able to live.

λογισθήσῃ38·

As much as modern historians

Also in chapter 53, he includes an

in the West look to Thucydides and Now hear me, son, and having

extensive survey of petroleum depos-

Herodotus to provide the conceptual learned the following teaching

its in the Caucasus and Armenia. For

frameworks for writing history, it is you will be wise among the

example:

possible now for intelligence analysts prudent (thοse having practical

Ἰστέον, ὅτι ἔξω τοῦ and scholars to look to a medieval wisdom), and reckoned prudent

κάστρου Ταμάταρχα πολλαὶ Byzantine emperor who undertook among the wise.

πηγαὶ ὑπάρχουσιν ἄφθαν the first, albeit limited, attempt at

national, all-source intelligence In this passage Constantine has sum-

ἀναδιδοῦσαι.37

analysis. moned a famous passage from book

There exist outside the strong- VI of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics.

hold of Tamatarcha many In doing so, we can reconsider

whether the establishment in 1947 Ἡ δὲ φρόνησις περὶ τὰ

springs yielding oil.

of an all-source intelligence anal- ἀνθρώπινα καὶ περὶ ὧν ἔστι

ysis capability in the United States βουλεύσασθαι39·

Reconsidering the Origins of is a unique moment of genesis or a

Practical wisdom concerns itself

Modern Intelligence Analysis? recapitulation of a rubric innovated

with human affairs and is about

a thousand years earlier. The circu-

Intelligence analysis that uses things that are deliberated.

lation since the 17th century of De

secrets, reasoning, and writing to Administrando Imperio in the West As a result, modern intelligence

address a state’s national security as the European state system was analysis should be considered not

policy priorities is an essential part of emerging also spurs questions about only as an evolving craft of infor-

national power. By modern stan- if and how this text was received mation management and analytic

dards, De Administrando falls short as the craft of intelligence analysis reasoning but also as the expression

of the full sensemaking of modern, began to emerge in Europe. of a practical—not purely theoreti-

all-source intelligence analysis.

cal—knowledge first articulated by

Nonetheless, this 10th century text Perhaps the most fundamental

Aristotle. Like much of the Greek

is precedent setting for the future consequence of linking modern in-

corpus whose transmission we owe to

development of intelligence analysis telligence analysis to this text would

Byzantium, we can also thank a 10th

by demonstrating for the first time be to gain deeper understanding of

century Byzantine emperor not only

the beginnings of its key constituent the roots of such policy-relevant

for his intelligence analysis innova-

parts. De Administrando Imperio writing in the works of Aristotle.

tions but also for reminding us that

is written to support a state’s na- Constantine VII in his introduction

intelligence analysts do their work in

tional security, it is written using a admonishes his son:

the shadow of Aristotle.

v v v

The author: Andrew Skitt Gilmour is a former CIA analyst of the Middle East. On retirement, he entered into classical

studies and is finding material of relevance to modern day intelligence. He is now a senior resident scholar at Catholic

University’s Center for the Study of Statesmanship. He is the author of A Middle East Primed for New Thinking:

Insights and Policy Options from the Ancient World. It is available on cia.gov.

Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022) 59

A Foreshadowing of Modern Intelligence Analysis

Endnotes

1. See chapters 1 and 2 in Francis Dvornik, Origins of Intelligence Services: The Ancient Near East, Persia, Greece, Rome, Byzantium, the

Arab Muslim Empires, the Mongol Empire, China, Muscovy (Rutgers University Press, 1974).

2. G. Wirth (post J. Haury), Procopii Caesariensis opera omnia, vol. 3, Leipzig: Teubner, 1963: 1, 4-186. Retrieved from: http://stepha-

nus.tlg.uci.edu.proxycu.wrlc.org/Iris/Cite?4029:002:257592 The English translations of this and other Greek texts cited are provided by

the author of this article.

3. Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperio, Romilly James Heald Jenkins (trans.) and Gyula Moravcsik (ed.) (Dumbar-

ton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, 1967).

4. The Latin title of the work was supplied in 1611 by John Meursius, who published the first Western edition of the Greek text.

5. Ibid., 11

6. Predrag Komatina, “Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperio and the Byzantine Historiography of the Mid-10th Centu-

ry,” Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta 2019, no. 56 (2019): 40.

7. G. Μοravcsik, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperio, 2nd edition (Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae 1.

Dumbarton Oaks, 1967] 44–286.

8. Warren Treadgold, The Middle Byzantine Historians (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 156.

9. Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio, 12.

10. Ibid.

11. Anthony Kaldellis, Ethnography after Antiquity: Foreign Lands and Peoples in Byzantine Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press,

2013), 93.

12. Dvornik, Origins of Intelligence Services, 176.

13. Arnold Toynbee, Constantine Porphyrogenitus and His World (Oxford University Press, 1973), 579.

14. Dvornik, Origins of Intelligence Services, 183.

15. Paul Stephenson, Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 33.

16. Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio, 14.

17. Dvornik, Origins of Intelligence Services, 177.

18. Ibid., 178.

19. Komatina, “Constantine Porphyrogenitus”: 44.

20. Robert Browning, Review: Constantine Porphyrogenitus De Administrando Imperio, Commentary by R. J. H. Jenkins, E. Dvornik, B.

Lewis, Gy. Moravcsik, D. Obolensky and S. Runciman in The English Historical Review 79, no. 310 (Jan. 1964): 146.

21. D.M. Lang, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 25, no. 1/3 (1962): 613.

22. Kaldellis, Ethnography after Antiquity, 89.

23. Ann Moffatt, The Journal of Hellenic Studies 93 (1973): 271–73.

24. Alice-Mary Talbot, “Byzantine Studies at the Beginning of the Twenty-first Century.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology

105, no. 1 (2006): 30.

25. Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio , 10.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Philip H.J. Davies and Kristian C. Gustafson, eds. Intelligence Elsewhere: Spies and Espionage Outside the Anglosphere (Georgetown

University Press, 2013), 79.

29. Edward Luttwak, The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), 6.

30. Davies and Gustafson, Intelligence Elsewhere, 77.

31. Toynbee, Constantine Porphyrogenitus and His World, 347.

32. Constantine VII, De Administrando Imperio, 48.

33. Ibid., 50.

34. Ibid., 48,50.

35. Ibid., 76.

36. Ibid., 286.

37. Ibid., 284.

38. Ibid., 44.

39. Ingram Bywater, Aristotelis ethica Nicomachea, (Clarendon Press, 1894 (repr. 1962): 1–224 (1094a1-1181b23). Retrieved from: http://

stephanus.tlg.uci.edu.proxycu.wrlc.org/Iris/Cite?0086:010:221730 13 Oct 2020.

v v v

60 Studies in Intelligence Vol. 66, No. 1 (Extracts, March 2022)

You might also like

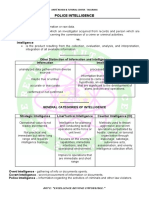

- Police Intelligence ReviewerDocument12 pagesPolice Intelligence ReviewerBimboy Cueno100% (8)

- John Prados - Presidents' Secret Wars - CIA & Pentagon Covert Operations Since World War II-William Morrow & Co. (1986) PDFDocument480 pagesJohn Prados - Presidents' Secret Wars - CIA & Pentagon Covert Operations Since World War II-William Morrow & Co. (1986) PDFmackandall sinisNo ratings yet

- Philip H. J. Davies, Kristian C. Gustafson Intelligence Elsewhere Spies and Espionage Outside The AnglosphereDocument320 pagesPhilip H. J. Davies, Kristian C. Gustafson Intelligence Elsewhere Spies and Espionage Outside The AnglospherehandroNo ratings yet

- Unit 05: Data Preparation & AnalysisDocument26 pagesUnit 05: Data Preparation & AnalysisTanya Malviya100% (1)

- Historical Setting of IntelligenceDocument35 pagesHistorical Setting of IntelligenceHarrison sajor100% (3)

- Article Monograph On Human Intelligence Operations in Pre-1979 IranDocument34 pagesArticle Monograph On Human Intelligence Operations in Pre-1979 IranChasHenryNewsNo ratings yet

- Studies Vol 49 No 3 - Book PDFDocument109 pagesStudies Vol 49 No 3 - Book PDFRossana CairaNo ratings yet

- Studies 60 1 March 2016 WEBDocument104 pagesStudies 60 1 March 2016 WEBLyzander MohanNo ratings yet

- Cdi Ass Ni MaxDocument9 pagesCdi Ass Ni MaxJulius Evia PajoteaNo ratings yet

- Cdi Ass Ni MaxDocument9 pagesCdi Ass Ni MaxJulius Evia PajoteaNo ratings yet

- Cdi Ass Ni MaxDocument5 pagesCdi Ass Ni MaxJulius Evia PajoteaNo ratings yet

- From Roman Speculatores to the NSA: Evolution of Espionage and Its Impact on Statecraft and Civil LibertiesFrom EverandFrom Roman Speculatores to the NSA: Evolution of Espionage and Its Impact on Statecraft and Civil LibertiesNo ratings yet

- Intel RevDocument3 pagesIntel RevLianne DarauayNo ratings yet

- Cdin 1Document7 pagesCdin 1Bea SalazarNo ratings yet

- Uttam Sah Gond - History - The Indic Roots of EspionageDocument8 pagesUttam Sah Gond - History - The Indic Roots of EspionageUTTAM SAH GONDNo ratings yet

- CDI 101 Hand-Outs FinalsDocument23 pagesCDI 101 Hand-Outs FinalsEugene YuNo ratings yet

- Lea Intelligence Review NotesDocument9 pagesLea Intelligence Review NotesAnne MacarioNo ratings yet

- Lea Police Intelligence FinalDocument9 pagesLea Police Intelligence FinalLloyd Rafael EstabilloNo ratings yet

- Police Intelligence BAGODocument14 pagesPolice Intelligence BAGOJudy Ann AciertoNo ratings yet

- HISTORICAL LESSONS LEARNED FOR TODAYS INTELLIGENCE PRACTICES - Paula-Diana Mantea - Teodoru Stefan - IKS 2018Document6 pagesHISTORICAL LESSONS LEARNED FOR TODAYS INTELLIGENCE PRACTICES - Paula-Diana Mantea - Teodoru Stefan - IKS 2018paula_hyNo ratings yet

- Secret WorldDocument2 pagesSecret WorldRaushan KumarNo ratings yet

- OSINT OverviewDocument4 pagesOSINT OverviewPaul MüllerNo ratings yet

- Police IntelligenceDocument16 pagesPolice IntelligenceroxanneNo ratings yet

- Police Intelligence GANDER FCDocument84 pagesPolice Intelligence GANDER FCAngel King RelativesNo ratings yet

- Police Intel CeltechDocument116 pagesPolice Intel CeltechMark Allen PulidoNo ratings yet

- Ulo D Police IntelligenceDocument150 pagesUlo D Police IntelligenceHANZ BALISTOYNo ratings yet

- Week 10Document25 pagesWeek 10Eduardo FriasNo ratings yet

- IntelDocument9 pagesIntelJulia Rose Fabia febreoNo ratings yet

- Complete Reviewer For IntelligenceDocument30 pagesComplete Reviewer For IntelligenceJuan TowTowNo ratings yet

- Schauer Storger Evo of Osint Winterspring2013Document4 pagesSchauer Storger Evo of Osint Winterspring2013jerrzykowalczykowianeczkownaNo ratings yet

- Police Intelligence: Dynamic Edge Learning SolutionsDocument82 pagesPolice Intelligence: Dynamic Edge Learning Solutionsdynamic_edge80% (5)

- Clarin, Jean Rai-Anne S. - Cdi - 1Document8 pagesClarin, Jean Rai-Anne S. - Cdi - 1Camille ClarinNo ratings yet

- Introduction To IntelligenceDocument7 pagesIntroduction To IntelligenceJudilyn RavilasNo ratings yet

- CDI IntelligenceDocument19 pagesCDI IntelligenceJaneth TagacaNo ratings yet

- IntelligenceDocument51 pagesIntelligenceMelanie HadiNo ratings yet

- Review in Intel 2009Document25 pagesReview in Intel 2009Bernard AyudaNo ratings yet

- Memorandom FOR PNPDocument199 pagesMemorandom FOR PNPjudy an maquisoNo ratings yet

- Review Police IntelligenceDocument116 pagesReview Police IntelligenceKristine Joy100% (1)

- Cdi101 IntelDocument110 pagesCdi101 IntelNatores Palangga JoyNo ratings yet

- The Anthropology of Police As Public AnthropologyDocument14 pagesThe Anthropology of Police As Public AnthropologycallicopellaNo ratings yet

- (Lea) Police IntelligenceDocument30 pages(Lea) Police IntelligenceShania MadridondoNo ratings yet

- Cdin 1 ReviewerDocument165 pagesCdin 1 ReviewerNicko SalinasNo ratings yet

- Viggi Dissertation 1Document56 pagesViggi Dissertation 1vysyas samayalNo ratings yet

- Portfolio CDIDocument17 pagesPortfolio CDIZuharra Jane EstradaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Humint - The Role of Foreign Agents in U.S. SecurityDocument46 pagesEvaluating Humint - The Role of Foreign Agents in U.S. SecurityRobin Bureau100% (3)

- Mercado Sailing The Sea of OSINT in The Information AgeDocument12 pagesMercado Sailing The Sea of OSINT in The Information AgeHugo RitaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2.revised RanchesDocument17 pagesChapter 2.revised RanchesAlex Abonales DumandanNo ratings yet

- The Egyptian Intelligence Service (A History of The Mukhabarat, 1910-2009) - (2010, Routledge) (10.4324 - 9780203854549) - Libgen - LiDocument284 pagesThe Egyptian Intelligence Service (A History of The Mukhabarat, 1910-2009) - (2010, Routledge) (10.4324 - 9780203854549) - Libgen - LiMehmet ŞencanNo ratings yet

- Notes LEA 3.2Document30 pagesNotes LEA 3.2JabbarNo ratings yet

- FINAL - Intelligence and Diplomacy PDFDocument13 pagesFINAL - Intelligence and Diplomacy PDFITjohn UKNo ratings yet

- Intelligence As A Tool of StrategyDocument16 pagesIntelligence As A Tool of Strategyjoanirricardo100% (1)

- Introduction To Police IntelligenceDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Police IntelligenceJohnedzel OsorioNo ratings yet

- RP 136Document16 pagesRP 136Victor LoxenNo ratings yet

- Cia Unclassified Documents (Related To 9/11)Document80 pagesCia Unclassified Documents (Related To 9/11)Chance EvansNo ratings yet

- Week of January 8Document5 pagesWeek of January 8Brayan MarshallNo ratings yet

- Law Enforcement Intelligence Classifications, Products, and DisseminationDocument14 pagesLaw Enforcement Intelligence Classifications, Products, and Disseminationjohnny mel icarusNo ratings yet

- Purposes, Roadmap, Thesis : I. BackgroundDocument17 pagesPurposes, Roadmap, Thesis : I. BackgroundWeramac100% (1)

- Code Warriors NSAs Codebreakers and The Secret inDocument3 pagesCode Warriors NSAs Codebreakers and The Secret inSALTINBANK CYBERSECNo ratings yet

- Review Notes On Law Enforcement Administration Sjit Criminology Cl-Mabikas 2014Document30 pagesReview Notes On Law Enforcement Administration Sjit Criminology Cl-Mabikas 2014hamlet DanucoNo ratings yet

- Definition of Strategic Human Resource ManagementDocument9 pagesDefinition of Strategic Human Resource ManagementAnkush RanaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft 365 - Mfa (13655)Document11 pagesMicrosoft 365 - Mfa (13655)Nioro FuriscalNo ratings yet

- The Communicative Language Teaching ApproachDocument5 pagesThe Communicative Language Teaching ApproachparsarouhNo ratings yet

- IEC Standard Symbols Packing and InstructionDocument11 pagesIEC Standard Symbols Packing and InstructionPumps RnDNo ratings yet

- Bec Matching CT 19 22fDocument4 pagesBec Matching CT 19 22fAshfaque AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ipil Heights Elementary SchoolDocument12 pagesIpil Heights Elementary SchoolAilljim Remolleno ComilleNo ratings yet

- Device Comment 12/6/2021 Data Name: COMMENTDocument17 pagesDevice Comment 12/6/2021 Data Name: COMMENTRio WicakNo ratings yet

- 2 3 Fer English in Ep GrammarDocument50 pages2 3 Fer English in Ep GrammarAikaterineGreaceNo ratings yet

- AC119 Cashflow StatementDocument82 pagesAC119 Cashflow StatementTINASHENo ratings yet

- Swatch Case AnalysisDocument3 pagesSwatch Case Analysisgunjanbihani100% (1)

- Ankle Sprain: Understanding Ankle Sprains The First 48 HoursDocument2 pagesAnkle Sprain: Understanding Ankle Sprains The First 48 HoursDhafin RizkyNo ratings yet

- Ravi MatthaiDocument7 pagesRavi MatthaiGaurav GargNo ratings yet

- OM1 Chapter 2: Competitiveness, Strategy, and ProductivityDocument1 pageOM1 Chapter 2: Competitiveness, Strategy, and ProductivityRoseanne Binayao LontianNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-195882503No ratings yet

- 1998 Book NumericalAnalysisDocument340 pages1998 Book NumericalAnalysisElham Anaraki100% (2)

- Atb164 Re4r01a, R4a-El Nissan ...... Planetary FailureDocument4 pagesAtb164 Re4r01a, R4a-El Nissan ...... Planetary FailureAleNo ratings yet

- CSE Annual Report 2021 v2Document136 pagesCSE Annual Report 2021 v2Jasmin AkterNo ratings yet

- An Impedance-Matching Technique For Increasing The Bandwidth of Microstrip AntennasDocument10 pagesAn Impedance-Matching Technique For Increasing The Bandwidth of Microstrip Antennasverdun6No ratings yet

- The Age of Digital Economy in IndiaDocument2 pagesThe Age of Digital Economy in IndiaPalak KhatriNo ratings yet

- Clinical ListingDocument21 pagesClinical ListingBassem AhmedNo ratings yet

- CPG Management of Chronic Hepatitis C in Adults-2Document64 pagesCPG Management of Chronic Hepatitis C in Adults-2shien910No ratings yet

- The Daily Tar Heel For April 10, 2012Document8 pagesThe Daily Tar Heel For April 10, 2012The Daily Tar HeelNo ratings yet

- 1 - Introduction of EOR MethodsDocument13 pages1 - Introduction of EOR MethodsReza AlfianoNo ratings yet

- Chandra X-Ray Observatory - WikipediaDocument3 pagesChandra X-Ray Observatory - WikipediabztNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology PH.D Entrance Test Paper 2017 Ganpat UniversityDocument11 pagesResearch Methodology PH.D Entrance Test Paper 2017 Ganpat UniversityMohammad GhadialiNo ratings yet

- Sewer Details CVI02720Document19 pagesSewer Details CVI02720Munir Baig100% (1)

- Spatial Analysis of Traffic AccidentDocument10 pagesSpatial Analysis of Traffic Accidentyoseph dejeneNo ratings yet

- Fixed Asset RegisterDocument3 pagesFixed Asset Registerzuldvsb0% (1)

- R8.4 Industrial Example of Nonadiabatic Reactor Operation: Oxidation of Sulfur DioxideDocument12 pagesR8.4 Industrial Example of Nonadiabatic Reactor Operation: Oxidation of Sulfur DioxideThanh HoàngNo ratings yet